To the Editor — Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) has undergone major technological advances in recent years, enabling the conception of various organism-level cell atlas projects. With increasing numbers of datasets being deposited in public archives, there is a need to ensure the reproducibility of such datasets. To this end, we describe the minSCe (Minimum Information about a Single-Cell Experiment) guidelines for a minimum set of metadata needed for robust comparative analyses of scRNA-seq.

scRNA-seq experiments have many advantages over so-called bulk RNA-sequencing and microarray experiments, as they allow researchers to study gene expression at an individual-cell rather than at tissue level1. As the scRNA-seq technologies are maturing, these experiments are becoming increasingly high-throughput and widespread. Data from an estimated 3,000 scRNA-seq studies have been submitted to NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)2, EMBL-EBI’s ArrayExpress3 and the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA)4 in recent years. Large collaborative efforts are taking off, such as the Human Cell Atlas (HCA)5, which aims to uncover the gene expression profiles of all human cell types; the Fly Cell Atlas (http://flycellatlas.org/), which has similar aims for Drosophila, or the Human Biomolecular Atlas Program (HuBMAP)6, as well as organ-specific projects, such as the BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Consortium7.

Meta-analyses combining data from independent scRNA-seq studies have been performed, revealing that although overall conclusions from independent studies confirm each other, there are notable differences8,9. To ensure that the results of individual scRNA-seq studies can be reproduced, to allow for reuse of data generated in such experiments, and, more generally, to enable researchers to build on previous discoveries, it is important that necessary minimal information about scRNA-seq experiments is collected and preserved together with the respective data. The community agreement and publication of the Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment (MIAME)10 guidelines almost two decades ago was a major milestone in the way functional genomics data have been reported and archived. For the last two decades, the functional genomics data archives at EBI and NCBI have been accepting microarray and bulk RNA-seq datasets; for the latter, the minimal metadata standards have now been well established in the MINSEQE (Minimum INformation about a SEQuencing Experiment) guidelines, but the emergence of protocols that can assay transcriptomics at single-cell resolution brings new requirements.

There is a clear need to establish minimum standards for reporting data and metadata for the various scRNA-seq assays. ArrayExpress and the HCA have published online guidelines for technical information required for scRNA-seq data submissions; however, these are not yet widely adopted community standards. Such standards would serve as the guiding principles and would ensure the reusability of the submitted datasets, guide the adaptation of existing archival resources and enable reproducibility of analysis by the wider scientific community. Here, we propose minSCe as a minimum set of single-cell metadata categories and a checklist of information that can be used to describe a single-cell assay in sufficient detail to enable analysis of the transcriptomic data. These guidelines are derived from work on building and adapting community resources to archive and add value to datasets, such as the Expression Atlas11, the HCA-Data Coordination Platform and the CIRM Stem Cell Hub.

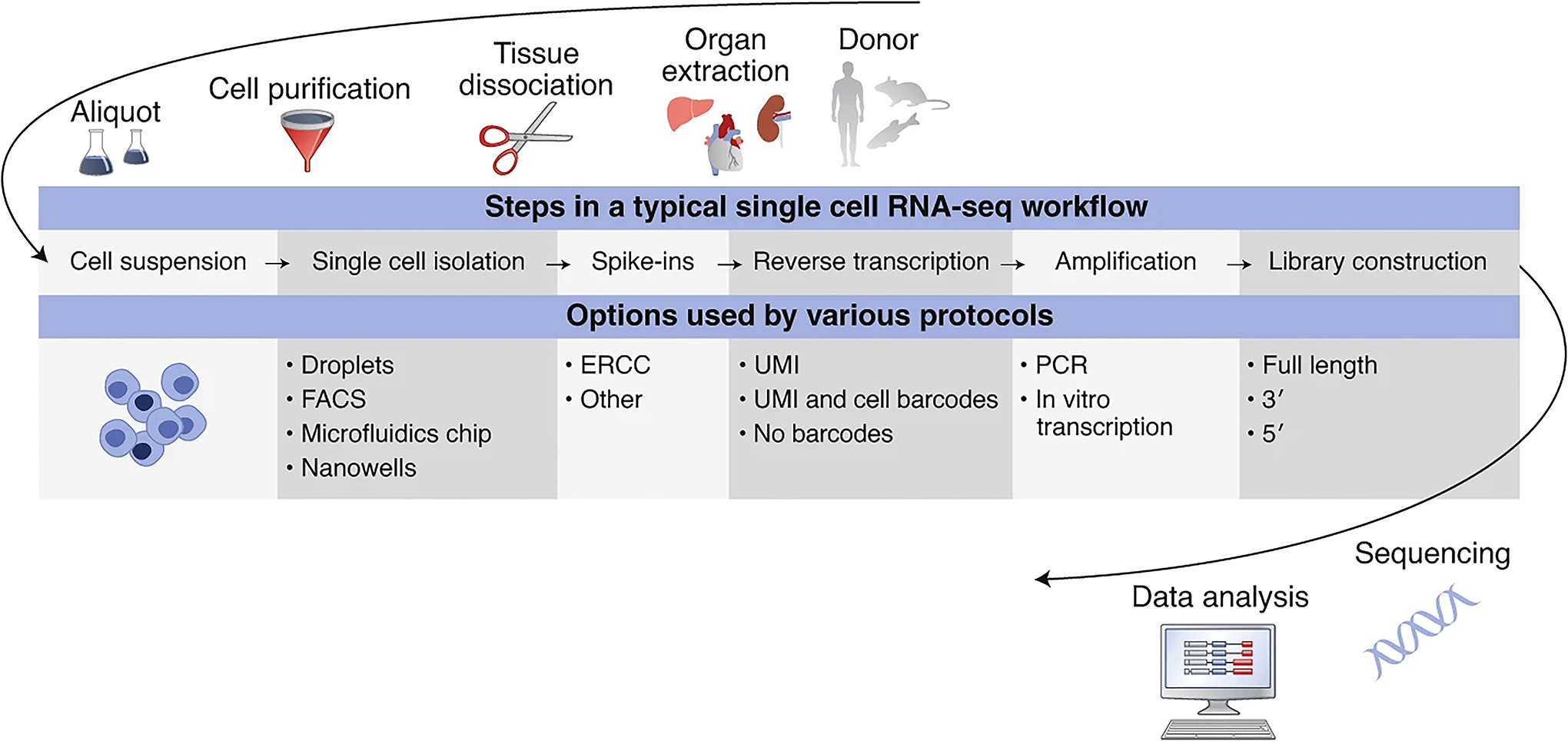

Typical designs of single-cell transcriptomic experiments include the following steps: (a) single cell isolation, (b) addition of spike-in RNAs, (c) reverse transcription, (d) amplification, (e) library construction, and (f) sequencing. Depending on the exact protocol followed, different types of metadata need to be recorded. Figure 1 shows an overview of the main steps that define the experimental workflows for scRNA-seq, with the variety of options used by different protocols12. For example, the Smart-seq2 protocol13, which is frequently used for single-cell transcriptomics, involves cell isolation using fluorescence-activated cell sorting into microwell plates to separate the single cells. Barcodes are typically not used during reverse transcription; amplification is done by PCR and libraries covering the full length of the sequences are constructed. Alternatively, microdroplet-based protocols such as the commonly used single-cell controller from 10x Genomics use droplets to encapsulate individual cells and barcode individual molecules during reverse transcription. This method uses a 3′ or 5′ tag system during library preparation.

Fig. 1 |. Typical design steps of single-cell transcriptomics experiments with examples for each step.

ERCC, External RNA Controls Consortium; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; UMI, unique molecular identifier.

Taking the five main components of the MIAME and MINSEQE experiment model10, we can describe a single-cell sequencing experiment with a few additions and changes (Fig. 2). Each component is equivalent to a main experimental step. We capture information describing each component and link it to the relevant protocols. Definitions of the individual components and a list of the single-cell-specific attributes that are introduced can be found in the Supplementary Information. For each field we recommend using terms from a suitable ontology (like NCBI taxonomy14 for species) or controlled vocabulary to prevent ambiguity. We refer to the Supplementary Information for examples of different implementations of the scRNA-seq metadata guidelines.

Fig. 2 |. Overview of the main components of a minSCe study.

The new components specific to single-cell experiments are highlighted in yellow (see Supplementary Table 1 for descriptions of the components), with example attributes (see Supplementary Table 2 for the full list of attributes). Asterisks represent placeholders for experiment-specific attributes.

A single-cell attribute of particular importance is the “inferred cell type,” which is used to describe a cell’s classification based on a distinct gene expression signature1. It is different from other experimental attributes as it is not known before the data analysis and is built on the results. Therefore, keeping record of reproducible data analysis steps is key to making the classification process transparent.

When depositing scRNA-seq data to a public archive, particular attention should be given to what is defined as a “sample” and how cell-specific metadata are recorded at the sample and the single-cell level, especially for methods that do not distinguish individual cells during the workflow. This may involve addition of extra metadata files with postanalysis information disaggregated by cell.

The adoption of MIAME guidelines by the scientific community, including the major scientific journals and public archives of functional genomics data15, was an important step towards enabling a widespread reuse of these data and established an important precedent for developing similar standards for other technology and data types16. We strongly believe that now is the time to discuss and adopt similar guidelines for scRNA-seq experiments, so that data generated in the growing number of these experiments are suitable for reuse and meta-analysis. The ArrayExpress database has already implemented a scRNA-seq data submission system that follows these guidelines. With this announcement we would like to ask journals and other public resources accepting scRNA-seq data also to follow the guidelines, while remaining flexible as the technology is developing and community feedback is being received. As single-cell transcriptomics are increasingly combined with imaging of tissue sections or quantification of surface proteins17, future work will involve alignment of these standards with newly emerging techniques requiring new types of metadata. We also expect minSCe to be expanded to single-cell genomic and epigenomic techniques (for example, single-cell ATAC-seq), which are not covered here, to incorporate a broader selection of single-cell assays. This will support the reuse and interoperability of various types of single-cell data and facilitate the development of atlases18,19.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory; the Wellcome Trust Biomedical Resources grant Single Cell Gene Expression Atlas (108437/Z/15/Z); the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (GC1R-06673-B); the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation (2018-182730); and the NIH Common Fund, through the Office of Strategic Coordination/Office of the NIH Director (OT2OD026677).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-00744-z.

References

- 1.Trapnell C Genome Res. 25, 1491–1498 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett T et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D991–D995 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Athar A et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 47D1, D711–D715 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison PW et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 47D1, D84–D88 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regev A et al. Preprint at arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.05192 (2018).

- 6.HuBMAP Consortium. Nature 574, 187–192 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ecker JR et al. Neuron 96, 542–557 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barkas N et al. Nat. Methods 16, 695–698 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hie B, Bryson B & Berger B Nat. Biotechnol 37, 685–691 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brazma A et al. Nat. Genet 29, 365–371 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papatheodorou I et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 48D1, D77–D83 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziegenhain C et al. Mol. Cell 65, 631–643.e634 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picelli S et al. Nat. Methods 10, 1096–1098 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Federhen S Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D136–D143 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anonymous. Nature 419, 323 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rung J & Brazma A Nat. Rev. Genet 14, 89–99 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoeckius M et al. Nat. Methods 14, 865–868 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davie K et al. Cell 174, 982–998.e920 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lein E, Borm LE & Linnarsson S Science 358, 64–69 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.