Abstract

Background

Gain-of-function mutations in CACNA1C encoding Cav1.2 cause syndromic or non-syndromic type-8 long QT syndrome (LQTS) (sLQT8 or nsLQT8). The cytoplasmic domain (D)Ⅰ-Ⅱ linker in Cav1.2 plays a pivotal role in calcium channel inactivation, and mutations in this site have been associated with sLQT8 (such as Timothy syndrome) but not nsLQT8.

Objective

Since we identified a novel CACNA1C mutation, located in the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker, associated with nsLQTS, we sought to reveal its biophysical defects.

Methods

Target panel sequencing was employed in 24 genotype-negative nsLQTS probands (after Sanger sequencing) and three family members. Wild-type (WT) or R511Q Cav1.2 was transiently expressed in tsA201 cells, then whole-cell Ca2+ or Ba2+ currents (ICa or IBa) were recorded using whole-cell patch-clamp techniques.

Results

We identified two CACNA1C mutations, a previously reported R858H mutation and a novel R511Q mutation located in the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker. Four members of one nsLQTS family harbored the CACNA1C R511Q mutation. The current density and steady-state activation were comparable to those of WT-ICa. However, persistent currents in R511Q-ICa were significantly larger than those of WT-ICa (WT at +20 mV: 3.3±0.3%, R511Q: 10.8±0.8%, P<0.01). The steady-state inactivation of R511Q-ICa was weak in comparison to that of WT-ICa at higher prepulse potentials, resulting in increased window currents in R511Q-ICa. Slow component of inactivation of R511Q-ICa was significantly delayed compared to that of WT-ICa (WT-tau at +20 mV: 81.3±3.3 ms, R511Q-tau: 125.1±5.0 ms, P<0.01). Inactivation of R511Q-IBa was still slower than that of WT-IBa, indicating that voltage-dependent inactivation (VDI) of R511Q-ICa was predominantly delayed.

Conclusions

Delayed VDI, increased persistent currents, and increased window currents of R511Q-ICa cause nsLQT8. Our data provide novel insights into the structure-function relationships of Cav1.2 and the pathophysiological roles of the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker in phenotypic manifestations.

Introduction

Congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS) is an inherited disorder characterized by a prolongation of QT interval and an increased risk of syncope and sudden cardiac death due to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, torsade de pointes, or ventricular fibrillation [1]. Seventeen genes have been reported to be causal for type-1 to type-17 LQTS (LQT1-17) thus far. However, not all genes appear to be definitely causal for LQTS [2]. Mutations in the first three identified genes—KCNQ1 for LQT1, KCNH2 for LQT2 and SCN5A for LQT3—account for approximately 90% of genetically affected LQTS patients, while those in other causal genes have rarely been identified [1].

CACNA1C, which encodes Cav1.2 composing the pore-forming α-subunit of cardiac L-type voltage-gated calcium channel (ICa), is thought to be definitely causal for LQTS classified as LQT8 [2–4]. Focusing on cardiac disorders, loss-of-function CACNA1C mutations have been associated with Brugada syndrome, early repolarization syndrome and short QT syndrome [3, 5, 6]. In contrast, gain-of-function CACNA1C mutations have been associated with syndromic LQT8 (sLQT8), namely, presenting with the LQTS phenotype plus other cardiac and/or extra-cardiac phenotypes: Timothy syndrome (TS), an extremely rare disease presenting with QT prolongation along with other cardiac and extra-cardiac phenotypes such as congenital heart defects, autism, developmental abnormalities, neurological dysfunction and syndactyly, atypical TS, and cardiac-only TS (COTS) presenting with QT prolongation along with other cardiac phenotypes such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and congenital heart defects but not extra-cardiac phenotypes [7–18]. In addition, gain-of-function CACNA1C mutations have also been associated with non-syndromic LQT8 (nsLQT8) presenting with pure LQTS phenotype without other cardiac or extra-cardiac phenotypes [19, 20]. Notably, CACNA1C mutations associated with nsLQT8 (pure LQT8 phenotype) have been proven to be more prevalent than previously expected [19, 20]. Although gain-of-function CACNA1C mutations can be associated with either sLQT8 (TS, aTS and COTS) or nsLQT8, the precise mechanisms that determine the different phenotypes remain unknown.

We previously analyzed major LQTS-related genes, including KCNQ1, KCNH2, SCN5A, KCNE1 and KCNE2, using Sanger sequencing in patients with nsLQTS in our cohort. However, there remained 24 genotype-negative patients. Therefore, we sought to identify pathogenic variants in these patients using target panel sequencing of 72 genes, including LQTS-related genes [21]. As a result, we identified two CACNA1C mutations, including a novel R511Q mutation, but did not detect any other pathogenic variants in LQTS-related genes.

The CACNA1C R511Q mutation is located in domain (D)Ⅰ-Ⅱ linker. The segment 6 (S6) in DⅠ (DⅠS6) and the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker play a pivotal role in ICa inactivation, and CACNA1C mutations in the DⅠS6 and DⅠ-Ⅱ linker have been associated with sLQT8 (TS, aTS and COTS) but not nsLQT8 [7, 8, 17, 18, 22, 23]. Therefore, we sought to clarify the biophysical defects of the CACNA1C R511Q mutation that causes nsLQT8.

Materials and methods

Subjects and genetic analyses

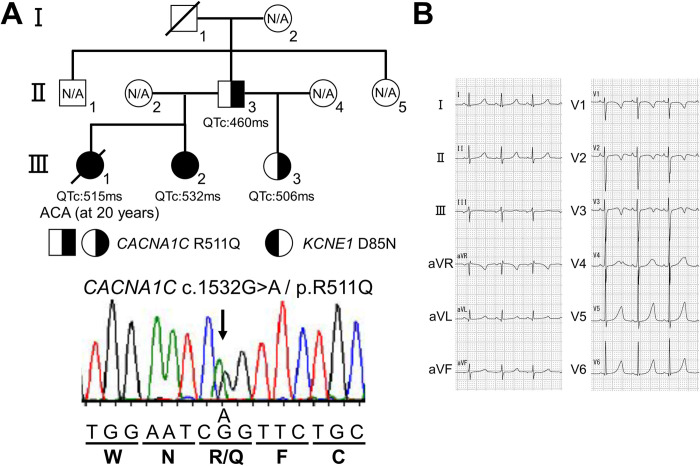

This study was approved by Gunma University Ethical Review Board for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (approval number: 2017–15). The subjects of this study were 24 genotype-negative nsLQTS probands remaining after screening major LQTS-related genes (KCNQ1, KCNH2, SCN5A, KCNE1 and KCNE2) using Sanger sequencing and three family members (Ⅱ-3, Ⅲ-2 and Ⅲ-3) of one proband (Ⅲ-1) (Fig 1A). Written informed consent for the genetic and functional analyses was obtained from the subjects. Clinical features of Ⅲ-1, Ⅲ-2 and Ⅱ-3 and genetic information of major LQTS-related genes (KCNQ1, KCNH2, SCN5A, KCNE1 and KCNE2), obtained by Sanger sequencing, of Ⅲ-1 and Ⅲ-2 have already been reported [24].

Fig 1. Identification of a CACNA1C R511Q mutation in a family with non-syndromic long QT syndrome.

A: Pedigree of patients harboring the CACNA1C R511Q mutation (upper panel). Half black filled symbols indicate heterozygous carrier of CACNA1C R511Q alone, and full black filled symbols indicate heterozygous carrier of both CACNA1C R511Q and KCNE1 D85N. ACA: aborted cardiac arrest, N/A: not genetically assessed. The electropherogram of a part of CACNA1C exon 12 of a patient (Ⅲ-3) is shown (lower panel). B: 12-lead ECG of the patient Ⅲ-3 in (A), recorded at 7 years old.

A target panel sequencing of 72 genes, including LQTS-related genes, was employed in the subjects, as previously described [21]. Briefly, genomic DNA extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes were subjected to custom panel sequencing using HaloPlex HS Custom (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) or xGen Predesigned Gene Capture Pools (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting library was subjected to the paired-end sequencing of 150 bp reads on MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). A bioinformatics analysis for HaloPlex HS Custom data was performed as previously described [21]. Reads obtained from xGen Predesigned Gene Capture Pools were subsequently aligned against hg19 using BWA and variant calling was performed using GATK in the BWA Enrichment v2.1.2 application on the BaseSpace Sequence Hub (Illumina) with default settings. The mean region coverage depth of 27 samples was 243 (150–426), and the percentage with target coverage of at least 20X was 98.8 (97.8–100). Among them, the mean region coverage depth was 327.9 (a CACNA1C R858H carrier), 196.4 (II-3), 204.8 (III-1), 290.1 (III-2) and 274 (III-3) (Fig 1A), and the percentage with target coverage of at least 20X was ≧99.9 in these cases. The identified variants, c.2573G>A/p.R858H in exon 19 and c.1532G>A/p.R511Q in exon 12 of CACNA1C (NM_000719.7), were validated by Sanger sequencing.

Mutagenesis and heterologous expression

The human wild-type (WT) CACNA1C cDNA tagged by (EYFP)Nα1C,77 in pcDNA vector and cDNAs of CACNB2b and CACNA2D1, both cloned in pcDNA3.1 vector, were kindly provided by Dr. Charles Antzelevitch (Masonic Medical Research Laboratory). Site-directed mutagenesis (CACNA1C R511Q) was performed using the QuikChangeⅡ Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. WT CACNA1C cDNA (2 μg) or R511Q CACNA1C cDNA (2 μg) in combination with CACNB2b cDNA (0.5 μg) and CACNA2D1 cDNA (0.5 μg) was transiently transfected into tsA201 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 36–48 hours before current recordings. Cells exhibiting green fluorescence were chosen for the current recordings.

Electrophysiology

Membrane calcium or barium currents (ICa or IBa) were recorded using whole-cell patch-clamp techniques at room temperature (23–25°C). Since electrophysiological studies of most gain-of-function CACNA1C mutations in the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker have been conducted under the condition of high extracellular calcium concentration, we also used a bath solution with a high calcium concentration. The bath solution contained (in mmol/L) 130 N-methyl-d-glucamine, 5 KCl, 15 CaCl2 (for ICa) or BaCl2 (for IBa), 1 MgCl2 and 10 HEPES (pH 7.35 with HCl), and the pipette solution contained (in mmol/L) 120 CsCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 MgATP, 5 CaCl2, 10 EGTA and 10 HEPES (pH 7.25 with CsOH). The electrode resistance ranged from 1.5 to 2.0 MΩ. Data acquisition was carried out using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and pCLAMP10.3 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Currents were acquired at 20–50 kHz, and low pass-filtered at 5 kHz using an analog-to-digital interface (Digidata 1440A acquisition system, Molecular Devices). Current densities at each test potential were obtained by dividing the calcium currents by cell capacitance. The steady-state activation and steady-state inactivation curves were fitted with Boltzmann functions of the following forms: y = 1-1/{1+exp[(Vm-V1/2)/K]} or y = 1/{1+exp[(Vm-V1/2)/K]}, respectively, where y is the relative current, Vm is the membrane potential, V1/2 is the voltage at which half of the channels are available to open, and K is the slope factor. The time course of inactivation was fitted with a single or double exponential function of the following form: I(t)/Imax = A0+A1[1-exp(-t/τ)] or I(t)/Imax = A0+Af[1-exp(-t/τf)]+As[1-exp(-t/τs)], where A and τ refer to the amplitudes and time constants, respectively, and f and s refer to the fast and slow components, respectively. I refers to the current, and t refers to the time. The time course of recovery from inactivation was fitted with a single exponential function of the following form: I(t)/Imax = A0+A1exp(-t/τ), as described previously [25, 26]. To avoid potential endogenous current contamination, recordings from the cells exhibiting peak inward current amplitudes of <0.3 nA were excluded from the analyses of the inactivation rate, steady-state inactivation and time courses of inactivation and recovery from inactivation.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error, and statistical comparisons were tested using the unpaired Student’s t-test with p<0.05 considered to be statistically significant. In some figures, the standard error bars are smaller than the data symbols.

Results

Identification of two CACNA1C mutations

We performed target panel sequencing in 24 genotype-negative nsLQTS probands after Sanger sequencing. As a result, we identified two CACNA1C mutations, an R858H mutation, which has already been reported, and a novel R511Q mutation, but did not detect any other pathogenic variants in LQTS-related genes [19]. Since the CACNA1C R858H mutation has already been functionally characterized by Fukuyama et al., we report the clinical characteristics of carriers of the novel CACNA1C R511Q mutation and its biophysical defects [19].

Case presentations harboring the CACNA1C R511Q mutation

The index patient (Ⅲ-3) (Fig 1A), a 17-year-old female at the time of the genetic test, had been asymptomatic with QT prolongation that had first been identified at 7 years of age. She was a younger paternal half-sister of the deceased case (Ⅲ-1) (Fig 1A) we had previously reported [24]. Her ECG showed sinus rhythm with QT prolongation (HR: 98 bpm, QTc: 506 ms) (Fig 1B). An echocardiogram revealed no structural heart disease. Neither she nor any other family members had any cardiac or extra-cardiac abnormalities, except for QT prolongation. We first examined whether or not the index patient (Ⅲ-3) (Fig 1A) carried the KCNE1 D85N variant, as with the proband (Ⅲ-1) (Fig 1A), using Sanger sequencing. However, we did not detect it, suggesting that other genetic factor(s) might be associated with this nsLQTS family.

In addition to the proband (Ⅲ-1) (Fig 1A), we therefore conducted target panel sequencing in the proband’s two sisters (Ⅲ-2 and Ⅲ-3) and father (Ⅱ-3) (Fig 1A) whose QT interval was slightly prolonged (HR: 60 bpm, QTc: 460 ms). As a result, we identified the CACNA1C R511Q variant in all four patients, and the finding was validated by Sanger sequencing (Fig 1A). The variant was present in neither gnomAD (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) nor 8.3KJPN (https://jmorp.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp/202109/variants), and PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) and SIFT (https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/) indicated that the variant was probably damaging and deleterious, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Data from prediction software, database, ClinVar and our target panel sequencing of CACNA1C R511Q and KCNE1 D85N variants.

| Prediction software | SNP database | ClinVar | Target panel sequencing Depth: Variant frequency |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAChange.refGene | SIFT _pred |

Polyphen2 _HDIV _pred |

gnomAD _exome _EAS |

8.3KJPN | Variation ID |

CLNDN | CLNSIG | II-3 | III-1 | III-2 | III-3 |

|

CACNA1C: NM_000719: exon12: c.G1532A: p.R511Q |

Del | D | - | - | 190641 | Long_QT_syndrome| not_provided |

Uncertain_ significance |

223: 0.486 | 247: 0.498 | 342: 0.456 | 275: 0.433 |

|

KCNE1: NM_000219: exon4: c.G253A: p.D85N |

Del | PD | 0.0055 | 0.0113 | 13479 | Cardiomyopathy| Long_QT_syndrome| Jervell_and_Lange-Nielsen_syndrome| Romano-Ward_syndrome| Long_QT_syndrome_5| Long_QT_syndrome_5,_ acquired,_susceptibility_to| Long_QT_syndrome_2/5| not_specified| Cardiovascular_phenotype| not_provided |

Conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity, other, risk factor Benign(6);Likely benign(4);Uncertain significance(3) |

- | 121: 0.554 | 110: 0.482 | - |

D: damaging, Del: deleterious, PD: probably damaging.

ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/190641/) indicated that the variant was uncertain significance (Table 1). On the other hand, the KCNE1 D85N variant was found in Ⅲ-1 and Ⅲ-2, as reported previously, but not in Ⅲ-3 and Ⅱ-3 (Table 1) (Fig 1A), suggesting that the CACNA1C R511Q variant might play a more important role in the generation of phenotypes than the KCNE1 D85N variant [24].

Biophysical defects of the CACNA1C R511Q mutation

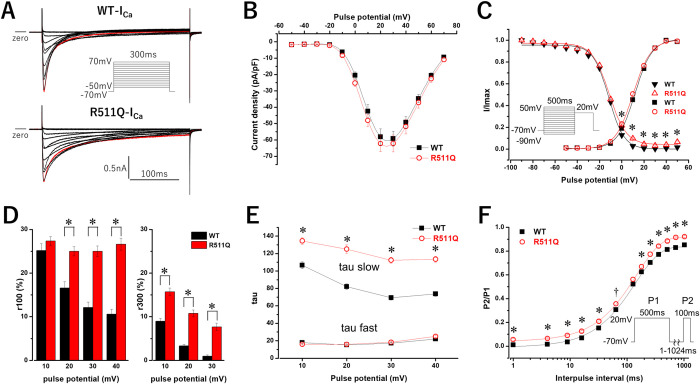

To examine the pathogenicity of the CACNA1C R511Q variant, we conducted a functional analysis by measuring whole-cell membrane currents using Ca2+ as a charge carrier (ICa). As shown in Fig 2A, WT CACNA1C exhibited ICa (WT-ICa), and R511Q CACNA1C exhibited ICa (R511Q-ICa) resembling WT-ICa. The peak current density, measured at +20 mV from a holding potential of -70 mV, and steady-state activation of R511Q-ICa were comparable to those of WT-ICa (Table 2) (Fig 2B and 2C).

Fig 2. Expressed calcium currents (ICa) of CACNA1C wild-type (WT-ICa) and R511Q (R511Q-ICa).

A: Representative current tracings of WT-ICa (upper panel) and R511Q-ICa (lower panel) obtained by the pulse protocol shown in the inset A. Red lines indicate the currents when the depolarizing potential was +20 mV. B: The current-voltage relationship of WT-ICa (filled squares, n = 20) and R511Q-ICa (open red circle n = 18). Peak currents obtained by the pulse protocol were normalized to cell capacitances. C: The voltage dependence of activation of WT-ICa (filled squares, n = 20) and R511Q-ICa (open red circles, n = 18), and the voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation, obtained by the pulse protocol shown in the inset, of WT-ICa (filled reverse triangles, n = 12) and R511Q-ICa (open red triangles, n = 14). Plots were fitted with a Boltzmann function. Fitted data are shown in Table 2. *P<0.01 vs. WT-ICa. D: The normalized amplitudes of persistent currents, assessed at 100-ms (r100) (left) and 300-ms (r300) (right) of various depolarizing potentials, of WT-ICa (n = 20) and R511Q-ICa (n = 18). Note that r300s at +40 mV were deleted because some r300s of WT-ICa at +40 mV were not precisely evaluated due to endogenous currents and/or leak currents. E: Fast and slow time constants (tau) of the voltage dependence of inactivation rate of WT-ICa (filled squares, n = 13) and R511Q-ICa (open red circles, n = 14). Inactivating currents obtained by the pulse protocol shown in the inset A were fitted by a double exponential function. *P<0.01 vs. WT-ICa. F: The time course of recovery from inactivation of WT-ICa (filled squares, n = 7) and R511Q-ICa (open red circles, n = 9). Plots were fitted with a single exponential function. †P<0.05 vs. WT-ICa, *P<0.01 vs. WT-ICa.

Table 2. Parameters of steady-state activation and steady-state inactivation for WT-ICa and R511Q-ICa.

| Steady-state activation | Steady-state inactivation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current density (pA/pF) at +20mV | V1/2 (mV) | K (mV) | V1/2 (mV) | K (mV) | |

| WT | 58±5.0 (n = 20) | 12.0±0.7 | 7.6±0.1 | -11.7±0.6 (n = 12) | 7.0±0.2 |

| R511Q | 62±4.9 (n = 18) | 10.4±0.7 | 8.0±0.2 | -11.1±0.4 (n = 14) | 7.9±0.3* |

V1/2: voltage at which half of the channels are available to open, K: slope factor

*P<0.01 vs. WT.

However, residual currents at 100-ms (r100) of depolarization potentials (+20 mV, +30 mV and +40 mV) in R511Q-ICa were significantly larger than those in WT-ICa (Table 3) (Fig 2D). Notably, although r100s of WT-ICa decreased with higher depolarization potentials, those of R511Q-ICa were maintained. On the other hand, residual persistent currents at 300-ms (r300) of depolarizing potentials (+10 mV, +20 mV and +30 mV) in R511Q-ICa were significantly larger than those in WT-ICa (Table 3) (Fig 2D). Although r300s of WT-ICa markedly decreased with higher depolarization potentials, those of R511Q-ICa showed a mild decrease. Thus, the difference in residual currents between WT-ICa and R511Q-ICa became larger with higher depolarization potentials.

Table 3. Parameters of persistent currents and inactivation for WT-ICa and R511Q-ICa.

| pulse potential (mV) | persistent currents | inactivation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r100 (%) | r300 (%) | A fast | tau fast (ms) | A slow | tau slow (ms) | ||

| +10 | WT | 25.2±1.6 | 9.0±0.6 | 0.49±0.01 | 17.9±0.9 | 0.51±0.01 | 105.4±3.8 |

| R511Q | 27.4±1.0 | 15.7±0.9* | 0.55±0.02* | 15.9±0.5 | 0.45±0.02* | 134.4±3.8* | |

| +20 | WT | 16.6±1.5 | 3.3±0.3 | 0.52±0.01 | 15.3±0.6 | 0.48±0.01 | 81.3±3.3 |

| R511Q | 25.0±1.1* | 10.8±0.8* | 0.49±0.02 | 15.8±0.6 | 0.51±0.02 | 125.1±5.0* | |

| +30 | WT | 12.1±1.3 | 0.9±0.3 | 0.55±0.02 | 17.2±0.8 | 0.45±0.02 | 67.9±2.6 |

| R511Q | 25.0±1.3* | 7.7±0.8* | 0.43±0.01* | 18.3±0.7 | 0.57±0.01* | 112.3±3.4* | |

| +40 | WT | 10.6±1.1 | - | 0.59±0.02 | 22.0±0.9 | 0.41±0.02 | 72.3±2.9 |

| R511Q | 26.6±1.4* | - | 0.39±0.02* | 25.0±1.2 | 0.61±0.02* | 113.4±3.4* | |

r100 and r300 indicate residual persistent currents (%) at 100-ms and 300-ms of depolarizing potential, respectively. Note that r300s at +40 mV were deleted because some r300s of WT-ICa at +40 mV were not precisely evaluated due to endogenous currents and/or leak currents. A fast and A slow indicate the amplitudes of fast and slow components of inactivation, respectively.

*P<0.01 vs. WT at each test potential.

ICa displays two forms of inactivation: voltage-dependent inactivation (VDI) and calcium-dependent inactivation (CDI) [3, 27, 28]. CDI and VDI are thought to correspond to the fast and slow component of inactivation, respectively. Inactivating currents of WT-ICa and R511Q-ICa during 300-ms depolarizing potentials from +10 mV to +40 mV could be fitted by a double exponential function. The time constants of fast components of R511Q-ICa were comparable to those of WT-ICa at each test potential, although the amplitudes of fast components of R511Q-ICa became smaller than those of WT-ICa as the depolarizing potentials became higher (Table 3) (Fig 2E). In contrast, the time constants of slow components of R511Q-ICa were significantly larger than those of WT-ICa at each test potential, and the amplitudes of slow component of R511Q-ICa became larger than those of WT-ICa as the depolarizing potentials became higher (Table 3) (Fig 2E). These findings suggest that, in R511Q-ICa, the CDI decreased and VDI increased with slower inactivation, especially at higher depolarization potentials.

The steady-state inactivation was assessed using a pulse protocol shown in the inset in Fig 2C. The voltage at which half of the channels are available to open (V1/2) of R511Q-ICa was comparable to that of WT-ICa (Table 2) (Fig 2C). However, the slope factor (K) of R511Q-ICa was significantly larger than that of WT-ICa (Table 2) (Fig 2C), and the I/Imax of R511Q-ICa was significantly larger than that of WT-ICa when prepulse potentials were between 0 mV and +50 mV (Fig 2C), possibly due to larger persistent currents during prepulse potentials in R511Q-ICa, which resulted in increased window currents in R511Q-ICa in comparison to those in WT-ICa (Fig 2C).

The recovery from inactivation was assessed using a double pulse protocol shown in the inset in Fig 2F, and plots were fitted by a single exponential function (Fig 2F). Although the P2/P1 of R511Q-ICa was significantly larger than that of WT-ICa from the beginning of an interpulse duration of several ms, possibly due to larger persistent currents in R511Q-ICa during P1 pulses, the time constant of R511Q-ICa was comparable to that of WT-ICa (WT-tau: 135±3.7 ms, n = 7, R511Q-tau: 145±7.6 ms, n = 9, P = NS). This indicated that the time course of recovery from inactivation of R511Q-ICa was not markedly different from that of WT-ICa.

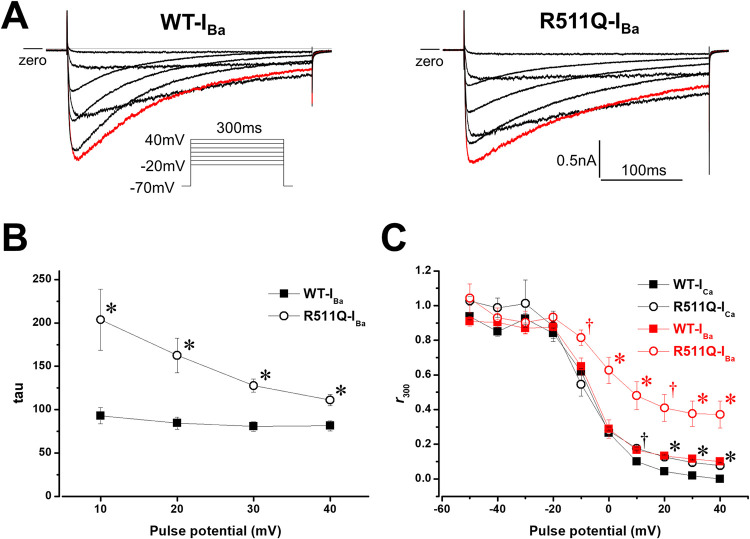

The VDI can be studied with Ba2+ as the charge carrier, which excludes the CDI process [28]. Therefore, the Ca2+ in the bath solution was replaced with Ba2+, and then Ba2+ currents through calcium channels (IBa) were recorded. As shown in Fig 3A, WT-IBa and R511Q-IBa exhibited delayed inactivation compared to WT-ICa and R511Q-ICa, respectively. Inactivating currents of WT-IBa and R511Q-IBa during depolarizing potentials from +10 mV to +40 mV could be fitted by a single exponential function. The time constants of R511Q-IBa were still larger than those of WT-IBa at each test potential (Fig 3B), suggesting that the VDI rather than the CDI of R511Q might be impaired. The VDI was presented as the fraction of current remaining after a 300-ms depolarization normalized to peak (r300) across various voltages, and the extent of CDI was calculated as f300 = (r300Ba-r300Ca)/r300Ba [18]. The VDI of R511Q-IBa and R511Q-ICa was significantly delayed compared to that of WT-IBa and WT-ICa, respectively (Fig 3C). However, the f300 for WT at +20 mV (WT-f300) and f300 for R511Q at +20 mV (R511Q-f300) were 0.67±0.05 (n = 5) and 0.67±0.05 (n = 4), respectively (p = NS). Taken together, these results indicated that the VDI of R511Q was predominantly impaired compared to the CDI.

Fig 3. Barium currents (IBa) of CACNA1C WT (WT-IBa) and R511Q (R511Q-IBa).

A: Representative current tracings of WT-IBa (left panel) and R511Q-IBa (right panel), obtained by the pulse protocol shown in the inset. Red lines indicate the currents when the depolarizing potential was +10 mV. B: Time constants (tau) of the voltage dependence of inactivation rate of WT-IBa (filled squares, n = 5) and R511Q-IBa (open circles, n = 4). Inactivating currents obtained by the pulse protocol shown in the inset A were fitted by a single exponential function. *P<0.01 vs. WT-IBa. C: Remaining currents after 300-ms depolarization normalized to peak currents (r300) of WT-ICa (filled squares, n = 5), R511Q-ICa (open circle, n = 4), WT-IBa (filled red squares, n = 5) and R511Q-IBa (open red circles, n = 4) at various potentials are shown. †P<0.05 vs. WT-ICa, *P<0.01 vs. WT-ICa, †(red)P<0.05 vs. WT-IBa, *(red)P<0.01 vs. WT-IBa.

Discussion

Identification of two CACNA1C mutations associated with nsLQT8

We identified two CACNA1C mutations, using target panel sequencing, in 24 genotype-negative nsLQTS patients after screening of major LQTS-related genes using Sanger sequencing. This appears to be consistent with the notion that nsLQT8 is more prevalent than previously expected [19, 20, 29, 30]. Therefore, the CACNA1C should be involved in genes for screening LQTS patients.

CACNA1C mutations that have been associated with QT prolongation

Cav1.2 is encoded by CACNA1C and composed of four homologous but non-identical domains (DⅠ-DⅣ) and intracellular N- and C-termini. Each domain contains six transmembrane spanning segments (S1-S6) consisting of a voltage-sensing domain (VSD) and pore-forming domain, intracellular and extracellular loops [28]. A gain-of-function of ICa by CACNA1C mutations throughout the Cav1.2 structure has been associated with sLQTS (TS, aTS and COTS) or nsLQT8.

A CACNA1C G406R mutation in exon 8A (G406R-8A), located in the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker, was firstly identified in type-1 TS (TS1) [7]. Next, CACNA1C G402S and G406R mutations in exon 8 (G402S-8 and G406R-8, respectively), located in the DⅠS6 or DⅠ-Ⅱ linker, were also identified in type-2 TS (TS2) [8]. Later, other CACNA1C mutations associated with aTS, COTS and nsLQT8 were identified [9–20, 29].

Gain-of-function of CACNA1C mutations associated with QT prolongation can be caused by multiple mechanisms, including delayed inactivation, increased persistent currents, increased window currents, increased current density, a combination thereof and increased permeability of non-selective monovalent cations [14]. However, the mechanisms that cause other cardiac and extra-cardiac phenotypes remain unknown.

Novel CACNA1C R511Q mutation and its biophysical defects

We identified the CACNA1C R511Q mutation, located in the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker, in four patients in one LQTS family. All patients harboring the mutation exhibited QT prolongation but no other cardiac or extra-cardiac phenotypes.

A functional study using a heterologous expression system revealed that the CACNA1C R511Q displayed a delay of the slow component of ICa inactivation, increased persistent currents, and increased window currents, without a change of the current density.

The inactivation of ICa occurs via two mechanisms: the VDI, which is linked to the change of transmembrane potential, and the CDI, which is mediated by calcium ions that carry the current [3, 27, 28]. The molecular determinants of the VDI include the cytoplasmic ends of the S6 segments, DⅠ-Ⅱ linker, and C-terminus of Cav1.2 [22]. In particular, the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker has been suggested to be a particle that occludes the channel pore during inactivation [22, 23]. In contrast, the molecular determinants of the CDI include C-terminus [22, 28, 31, 32].

When Ba2+ is used as a charge carrier (IBa), the fast component of inactivation is lost and the slow component of inactivation is markedly decelerated [28]. In our experiments, inactivating Ba2+ currents in both WT-IBa and R511Q-IBa could be fitted by a single exponential function rather than a double exponential function, possibly due to a loss of the fast component of ICa inactivation. Time constants of inactivating currents in R511Q-IBa were still larger than those in WT-IBa, indicating that the VDI of R511Q-ICa was predominantly decelerated compared to that of WT-ICa. Furthermore, the extent of calculated CDI was not different between WT and R511Q, which also indicated that the VDI of R511Q-ICa was predominantly decelerated.

CACNA1C mutations in the DⅠS6 or DⅠ-Ⅱ linker

Focusing on mutations in the DⅠS6 and DⅠ-Ⅱ linker, those for TS1 and TS2 (G406R-8A, G402S-8 and G406R-8) displayed a marked delay of ICa inactivation, marked increases of persistent currents and window currents (Table 4) [7, 8]. A G419R mutation for aTS displayed an increased current density with accelerated inactivation (Table 4) [17]. Mutations, R518H and R518C for COTS, displayed a delay of ICa inactivation, increased persistent currents and increased window currents (but those were weaker than TS mutations: G406R-8A, G402S-8 and G406R-8) with a reduced current density (Table 4) [18]. In our study, the R511Q mutation displayed a delay of ICa inactivation, increased persistent currents, which is very likely the main actor of QT prolongation, and increased window currents (but those were weaker than TS mutations: G406R-8A, G402S-8 and G406R-8) without a change of current density. These biophysical defects of the R511Q mutation were more modest than seen in other mutations for TS, aTS or COTS (Table 4), which may be the reason why the R511Q mutation is associated with nsLQT8 but not with other cardiac and extra-cardiac phenotypes. Otherwise, TS mutations have been reported to impair not only the VDI but also the CDI, suggesting that an impairment of the CDI may be associated with the manifestation of other cardiac or extra-cardiac phenotypes [7, 33–35]. These findings provide a novel insight into the pathophysiological roles of the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker in phenotypic manifestations.

Table 4. Comparison of electrophysiological parameters of gain-of-function CACNA1C mutations in DⅠ-Ⅱ linker that have been reported.

| Phenotype | TS1 | TS2 | aTS | COTS | nsLQTS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | G406R-8A | G402S-8 | G406R-8 | G419R | R518C | R518H | R511Q |

| Expressed cells | CHO cells | Xenopus oocytes | Xenopus oocytes | HEK293T cells | HEK293 cells | HEK293 cells | tsA201 cells |

| Current density | no change | no change | no change | increased (4-fold) | decreased (55.6%) | decreased (63.2%) | no change |

| Inactivation rate | delayed (marked) | delayed (marked) | delayed (marked) | accelerated (slight) | delayed | delayed | delayed |

| Persistent currents | increased (marked) | increased (marked) | increased (marked) | no change | increased (~7.0-fold) | increased (~6.6-fold) | increased |

| SSA | no change | no change | negatively shifted | negatively shifted (~10 mV) | no change | positively shifted (~4.5 mV) | no change |

| SSI | positively shifted (marked) | positively shifted (marked) | positively shifted (marked) | no change | positively shifted (~6.8 mV) | positively shifted (~7.0 mV) | not shifted |

| Window currents | increased (marked) | increased (marked) | increased (marked) | increased | increased | increased | increased (slight) |

| References | [7] | [8] | [8] | [17] | [18] | [18] | this study |

TS1, type-1 Timothy syndrome; TS2, type-2 Timothy syndrome; aTS, atypical Timothy syndrome; COTS, cardiac only Timothy syndrome; nsLQT8, non-syndromic long QT syndrome, SSA, steady-state activation: SSI, steady-state inactivation.

Korkosh et al. recently built structural models of Cav1.2 and proposed mechanisms underlying the VDI: The cytoplasmic N-terminal part of VSDII (DIIS0) in the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker is bound with the α1-interaction domain (AID). Following voltage-dependent channel activation, the cytoplasmic face of DIIS0 would perturb and shift DIIS0-bound AID toward the pore axis. The AID-linked DIS6 would bend at the flexible G402 and G406, facilitating the activation-gate closure and thus the VDI [36]. The R511 position in DIIS0 may form a salt bridge with acidic residues in positions immediately C-terminal to the AID. Therefore, the R511Q mutation would destroy the salt bridges and weaken the DIIS0-AID contact, retarding the AID displacement thus delaying the VDI. Regarding the interaction of AID and β-subunit, four basic residues (R514, R515, R518 and K522) in DIIS0 are thought to provide large contributions to the interaction energy between AID and β-subunit, while R511 is not [36]. Further studies are required to reveal whether or not R511Q affects the DIIS0-AID-β-subunit interaction.

TS patient- and COTS patient-derived human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) have been established [37, 38]. An analysis of patient (with the CACNA1C R511Q mutation)-derived hiPSC-CMs and mutant allele-specific knockout using a clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-CRISPR associated protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9) system may reveal the pathophysiological roles of the CACNA1C R511Q in QT prolongation and arrhythmogenesis.

Other genetic variants in this nsLQTS family

All four patients presenting with QT prolongation in the family carried the CACNA1C R511Q mutation, but not all carried the KCNE1 D85N variant which was reported to be a disease-causing or a drug-induced LQTS variant [24, 39, 40]. This suggested that the CACNA1C R511Q mutation might be a main contributor to QT prolongation in this family, and the KCNE1 D85N variant may have contributed less to QT prolongation in comparison to the CACNA1C R511Q mutation. Although the father (Ⅱ-3) (Fig 1A) harbors the CACNA1C R511Q mutation, his QTc interval was only slightly prolonged. This may be due to the fact that the QTc interval in males is shorter than that in females. The contribution of these variants to QT prolongation and cardiac events in this family needs to be further investigated.

Conclusions

Target panel sequencing in 24 genotype-negative nsLQTS patients after Sanger screening identified two CACNA1C mutations: An R858H mutation in one proband and a novel R511Q mutation in one family. This supported the notion that nsLQT8 is more prevalent than previously expected. Despite the fact that CACNA1C mutations in the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker have been associated with sLQTS (TS, aTS and COTS), the R511Q mutation in this site is associated with nsLQT8. The biophysical defects of the R511Q mutation were a delay of slow component of ICa inactivation through predominant impairment of the VDI, increased persistent currents, and increased window currents, without a change of the current density. The degree of functional impairment associated with the R511Q was more modest in comparison to that seen with TS, aTS and COTS mutations. These findings provide novel insights into the structure-function relationships of Cav1.2 and the pathophysiological roles of the DⅠ-Ⅱ linker in phenotypic manifestations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Charles Antzelevitch (Masonic Medical Research Laboratory) for kindly providing us with the human wild-type (WT) CACNA1C cDNA tagged by (EYFP)Nα1C,77 in pcDNA vector and cDNAs of CACNB2b and CACNA2D1, both cloned in pcDNA3.1 vector. We also thank Ms. Miki Matsui, Ms. Saori Fujimoto, Mr. Yohei Morishita, Dr. Yuichi Uosaki, Ms. Yoko Yokoyama, Ms. Hiroko Matsuda, Dr. Pinjie Bao and Ms. Saori Umezawa for their helpful technical assistances.

Abbreviations

- AID

α1-interaction domain

- aTS

atypical Timothy syndrome

- CDI

calcium-dependent inactivation

- COTS

cardiac only Timothy syndrome

- DⅠ-Ⅱ

domain Ⅰ-Ⅱ

- IBa

barium currents

- ICa

calcium currents

- LQTS

long QT syndrome

- nsLQT8

non-syndromic type-8 long QT syndrome

- sLQT8

syndromic type-8 long QT syndrome

- TS

Timothy syndrome

- VDI

voltage-dependent inactivation

- WT

wild-type

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant Number: 20K08487 to T.N.) and by MEXT Program for supporting the introduction of the new sharing system (Grant Number: JPMXS0420600120). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Nakajima T, Tamura S, Kurabayashi M, Kaneko Y. Towards Mutation-Specific Precision Medicine in Atypical Clinical Phenotypes of Inherited Arrhythmia Syndromes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22:3930. doi: 10.3390/ijms22083930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler A, Novelli V, Amin AS, Abiusi E, Care M, Nannenberg EA, et al. An International, Multicentered, Evidence-Based Reappraisal of Genes Reported to Cause Congenital Long QT Syndrome. Circulation. 2020; 141:418–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Q, Chen J, Qin Y, Wang J, Zhou L. Mutations in voltage-gated L-type calcium channel: implications in cardiac arrhythmia. Channels (Austin). 2018; 12:201–18. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2018.1499368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcantoni A, Calorio C, Hidisoglu E, Chiantia G, Carbone E. Cav1.2 channelopathies causing autism: new hallmarks on Timothy syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2020; 472:775–89. doi: 10.1007/s00424-020-02430-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antzelevitch C, Pollevick GD, Cordeiro JM, Casis O, Sanguinetti MC, Aizawa Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the cardiac calcium channel underlie a new clinical entity characterized by ST-segment elevation, short QT intervals, and sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2007; 115:442–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burashnikov E, Pfeiffer R, Barajas-Martinez H, Delpon E, Hu D, Desai M, et al. Mutations in the cardiac L-type calcium channel associated with inherited J-wave syndromes and sudden cardiac death. Heart rhythm: the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2010; 7:1872–82. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM, Decher N, Kumar P, Bloise R, et al. Ca(V)1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell. 2004; 119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Decher N, Kumar P, Sachse FB, Beggs AH, et al. Severe arrhythmia disorder caused by cardiac L-type calcium channel mutations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005; 102:8089–96; discussion 6–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502506102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillis J, Burashnikov E, Antzelevitch C, Blaser S, Gross G, Turner L, et al. Long QT, syndactyly, joint contractures, stroke and novel CACNA1C mutation: expanding the spectrum of Timothy syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2012; 158A:182–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennessey JA, Boczek NJ, Jiang YH, Miller JD, Patrick W, Pfeiffer R, et al. A CACNA1C variant associated with reduced voltage-dependent inactivation, increased CaV1.2 channel window current, and arrhythmogenesis. PloS one. 2014; 9:e106982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boczek NJ, Miller EM, Ye D, Nesterenko VV, Tester DJ, Antzelevitch C, et al. Novel Timothy syndrome mutation leading to increase in CACNA1C window current. Heart rhythm: the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2015; 12:211–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.09.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozawa J, Ohno S, Saito H, Saitoh A, Matsuura H, Horie M. A novel CACNA1C mutation identified in a patient with Timothy syndrome without syndactyly exerts both marked loss- and gain-of-function effects. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2018; 4:273–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dufendach KA, Timothy K, Ackerman MJ, Blevins B, Pflaumer A, Etheridge S, et al. Clinical Outcomes and Modes of Death in Timothy Syndrome: A Multicenter International Study of a Rare Disorder. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018; 4:459–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2017.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye D, Tester DJ, Zhou W, Papagiannis J, Ackerman MJ. A pore-localizing CACNA1C-E1115K missense mutation, identified in a patient with idiopathic QT prolongation, bradycardia, and autism spectrum disorder, converts the L-type calcium channel into a hybrid nonselective monovalent cation channel. Heart rhythm: the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2019; 16:270–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colson C, Mittre H, Busson A, Leenhardt A, Denjoy I, Fressard V, et al. Unusual clinical description of adult with Timothy syndrome, carrier of a new heterozygote mutation of CACNA1C. Eur J Med Genet. 2019; 62:103648. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Po C, Zordan R, Vecchi M, Cerutti A, Sartori S, Trevisson E, et al. Photosensitive epilepsy and long QT: expanding Timothy syndrome phenotype. Clin Neurophysiol. 2019; 130:2134–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelu Bisabu K, Zhao J, Mokrane AE, Segura E, Marsolais M, Grondin S, et al. Novel Gain-of-Function Variant in CACNA1C Associated With Timothy Syndrome, Multiple Accessory Pathways, and Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020; 13:e003123. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.120.003123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boczek NJ, Ye D, Jin F, Tester DJ, Huseby A, Bos JM, et al. Identification and Functional Characterization of a Novel CACNA1C-Mediated Cardiac Disorder Characterized by Prolonged QT Intervals With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Congenital Heart Defects, and Sudden Cardiac Death. Circulation Arrhythmia and electrophysiology. 2015; 8:1122–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.002745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuyama M, Wang Q, Kato K, Ohno S, Ding WG, Toyoda F, et al. Long QT syndrome type 8: novel CACNA1C mutations causing QT prolongation and variant phenotypes. Europace: European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology: journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2014; 16:1828–37. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wemhoner K, Friedrich C, Stallmeyer B, Coffey AJ, Grace A, Zumhagen S, et al. Gain-of-function mutations in the calcium channel CACNA1C (Cav1.2) cause non-syndromic long-QT but not Timothy syndrome. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2015; 80:186–95. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakajima T, Dharmawan T, Kawabata-Iwakawa R, Tamura S, Hasegawa H, Kobari T, et al. Biophysical defects of an SCN5A V1667I mutation associated with epinephrine-induced marked QT prolongation. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2020. doi: 10.1111/jce.14575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Kahl S, Wegener JW. L-type CaV1.2 calcium channels: from in vitro findings to in vivo function. Physiological reviews. 2014; 94:303–26. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zamponi GW, Striessnig J, Koschak A, Dolphin AC. The Physiology, Pathology, and Pharmacology of Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels and Their Future Therapeutic Potential. Pharmacol Rev. 2015; 67:821–70. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.009654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima T, Kaneko Y, Manita M, Iso T, Kurabayashi M. Aborted cardiac arrest in a patient carrying KCNE1 D85N variant during the postpartum period. Internal Medicine. 2010; 49:1875–8. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakajima T, Kaneko Y, Saito A, Ota M, Iijima T, Kurabayashi M. Enhanced fast-inactivated state stability of cardiac sodium channels by a novel voltage sensor SCN5A mutation, R1632C, as a cause of atypical Brugada syndrome. Heart rhythm: the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2015; 12:2296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dharmawan T, Nakajima T, Iizuka T, Tamura S, Matsui H, Kaneko Y, et al. Enhanced closed-state inactivation of mutant cardiac sodium channels (SCN5A N1541D and R1632C) through different mechanisms. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2019; 130:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferreira G, Yi J, Rios E, Shirokov R. Ion-dependent inactivation of barium current through L-type calcium channels. The Journal of general physiology. 1997; 109:449–61. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.4.449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson ME. Ca2+-dependent regulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels: is a unifying mechanism at hand? Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2001; 33:639–50. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boczek NJ, Best JM, Tester DJ, Giudicessi JR, Middha S, Evans JM, et al. Exome sequencing and systems biology converge to identify novel mutations in the L-type calcium channel, CACNA1C, linked to autosomal dominant long QT syndrome. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2013; 6:279–89. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landstrom AP, Boczek NJ, Ye D, Miyake CY, De la Uz CM, Allen HD, et al. Novel long QT syndrome-associated missense mutation, L762F, in CACNA1C-encoded L-type calcium channel imparts a slower inactivation tau and increased sustained and window current. International journal of cardiology. 2016; 220:290–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterson BZ, DeMaria CD, Adelman JP, Yue DT. Calmodulin is the Ca2+ sensor for Ca2+ -dependent inactivation of L-type calcium channels. Neuron. 1999; 22:549–58. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80709-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuhlke RD, Pitt GS, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW, Reuter H. Calmodulin supports both inactivation and facilitation of L-type calcium channels. Nature. 1999; 399:159–62. doi: 10.1038/20200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrett CF, Tsien RW. The Timothy syndrome mutation differentially affects voltage- and calcium-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2 L-type calcium channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008; 105:2157–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710501105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dick IE, Joshi-Mukherjee R, Yang W, Yue DT. Arrhythmogenesis in Timothy Syndrome is associated with defects in Ca(2+)-dependent inactivation. Nature communications. 2016; 7:10370. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calorio C, Gavello D, Guarina L, Salio C, Sassoe-Pognetto M, Riganti C, et al. Impaired chromaffin cell excitability and exocytosis in autistic Timothy syndrome TS2-neo mouse rescued by L-type calcium channel blockers. The Journal of physiology. 2019; 597:1705–33. doi: 10.1113/JP277487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korkosh VS, Kiselev AM, Mikhaylov EN, Kostareva AA, Zhorov BS. Atomic Mechanisms of Timothy Syndrome-Associated Mutations in Calcium Channel Cav1.2. Front Physiol. 2019; 10:335. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yazawa M, Hsueh B, Jia X, Pasca AM, Bernstein JA, Hallmayer J, et al. Using induced pluripotent stem cells to investigate cardiac phenotypes in Timothy syndrome. Nature. 2011; 471:230–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Estes SI, Ye D, Zhou W, Dotzler SM, Tester DJ, Bos JM, et al. Characterization of the CACNA1C-R518C Missense Mutation in the Pathobiology of Long-QT Syndrome Using Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Cardiomyocytes Shows Action Potential Prolongation and L-Type Calcium Channel Perturbation. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2019; 12:e002534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.119.002534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishio Y, Makiyama T, Itoh H, Sakaguchi T, Ohno S, Gong YZ, et al. D85N, a KCNE1 polymorphism, is a disease-causing gene variant in long QT syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009; 54:812–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nof E, Barajas-Martinez H, Eldar M, Urrutia J, Caceres G, Rosenfeld G, et al. LQT5 masquerading as LQT2: a dominant negative effect of KCNE1-D85N rare polymorphism on KCNH2 current. Europace: European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology: journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2011; 13:1478–83. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.