February 14, 2022

“Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Willing is not enough; we must do.”—Goethe

Introduction

People and the communities they are a part of—defined as “groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity . . . or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people”—are deeply impacted by the systems that drive and influence their health; however, they are often not included in the process to create or restructure programs and policies designed to benefit them (CDC, 2011). When health and health care policies and programs designed to improve outcomes are not driven by community interests, concerns, assets, and needs, these efforts remain disconnected from the people they intend to serve. This disconnect ultimately limits the influence and effectiveness of interventions, policies, and programs.

Over the last several years, health and health care entities, including advocacy organizations, philanthropic and funding agencies, care systems and hospitals, and academic and research organizations, among others, are recognizing the need to engage the communities they serve. Yet, many entities only conduct superficial engagement— the community is denied access to the decision-making process, and interactions tend toward tokenism and marginalization, or the community is simply informed of plans or consulted to provide limited perspectives on select activities (Carman and Workman, 2017; Facilitating Power, 2020). True, meaningful community engagement requires working collaboratively with and through those who share similar situations, concerns, or challenges. Their engagement serves as “a powerful vehicle for bringing about environmental and behavioral changes that will improve the health of the community and its members. [It] often involves partnerships and coalitions that help mobilize resources and influence systems, change relationships among partners, and serve as catalysts for changing policies, programs, and practices” (CDC, 2011). Shifting toward meaningful community engagement often requires decision makers to defer to communities and move to power sharing and equitable transformation—necessary elements to ensure sustainable change that improves health and well-being (Facilitating Power, 2020). It is important to note that meaningful community engagement requires working closely with communities to understand their preferences on how, when, and to what level and degree they want to be engaged in efforts. Some communities may prefer to only provide input or be consulted at certain times, while others may prefer shared power and decision-making authority.

Tools and resources are available to provide practical guidance on and support for community engagement (CDC, 2011). Yet, the intention to engage does not always translate to or ensure effective engagement (Carman and Workman, 2017; Facilitating Power, 2020). In other words, the fundamental question is not whether entities think they are engaging communities but whether communities feel engaged. Bridging this gap requires the ability to define meaningful community engagement and assess its impact—especially related to specific health and health care programs, policies, and outcomes.

With these realities in mind, the National Academy of Medicine’s Leadership Consortium: Collaboration for a Value & Science-Driven Health System, with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and guidance from an Organizing Committee, is advancing a project to identify concepts and metrics that can best assess the extent, process, and impact of community engagement. The Organizing Committee comprises experts in community engagement—community leaders, researchers, and policy advisors—who are diverse in many ways, including geographic location, race and ethnicity, nationality, disability, sexual orientation, and gender identity (see Box 1). This effort aims to provide community-engaged, effective, and evidence-based tools to those who want to measure engagement to ensure that it is meaningful and impactful, emphasizing equity as a critical input and outcome. As work began on the project, the Organizing Committee realized the need for a conceptual model illustrating the dynamic relationship between community engagement and improved health and health care outcomes. This commentary will describe how the Organizing Committee arrived at the conceptual model, the critical content that the model contains and expresses, and how the model can be used to assess meaningful community engagement.

BOX 1. Organizing Committee for Meaningful Community Engagement.

Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, University of California, Davis (co-chair)

Syed M. Ahmed, Medical College of Wisconsin

Ayodola Anise, National Academy of Medicine

Atum Azzahir, Cultural Wellness Center*

Kellan E. Baker, Whitman-Walker Institute

Anna Cupito, National Academy of Medicine (until July 2021)

Milton Eder, University of Minnesota

Tekisha Dwan Everette, Health Equity Solutions

Kim Erwin, IIT Institute of Design

Maret Felzien, Northeastern Junior College*

Elmer Freeman, Center for Community Health Education Research and Service

David Gibbs, Community Initiatives

Ella Greene-Moton, University of Michigan School of Public Health

Sinsi Hernández-Cancio, National Partnership for Women & Families (co-chair)

Ann Hwang, Harvard Medical School (co-chair)

Felica Jones, Healthy African American Families II*

Grant Jones, Center for African American Health*

Marita Jones, Healthy Native Communities Partnership*

Dmitry Khodyakov, RAND Corporation and Pardee RAND Graduate School

J. Lloyd Michener, Duke School of Medicine

Bobby Milstein, ReThink Health

Debra S. Oto-Kent, Health Education Council*

Michael Orban, Orban Foundation for Veterans*

Burt Pusch, Commonwealth Care Alliance*

Mona Shah, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Monique Shaw, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Julie Tarrant, National Academy of Medicine

Nina Wallerstein, University of New Mexico

John M. Westfall, American Academy of Family Physicians

Asia Williams, National Academy of Medicine

Richard Zaldivar, The Wall Las Memorias Project

Provided perspectives on the conceptual model through in-depth interviews

Background on the Development of the Conceptual Model

The Organizing Committee identified the need for a new conceptual model that could be used by a range of stakeholders, including federal, state, and local agencies; tribal communities; advocacy and community-based groups; funders, philanthropists and financiers; academic institutions; care systems, health centers, and hospitals; and payers, plans, and industry. The Organizing Committee additionally highlighted important considerations for the conceptual model design and development process.

The Need for a New Conceptual Model

An analysis of the peer-reviewed literature and organizational websites for frameworks and conceptual models of engagement identified over 20 examples. Several models explicitly focused on partnership processes and levels of engagement. Other models connected engagement to factors influencing health, interventions, policy making, community-based participatory research (CBPR), and patient-centered comparative effectiveness research. Only a few models associated engagement to outcomes, indicators, or metrics. One model, drawing from CBPR evaluation, connected partnership characteristics, partnership function, partnership synergy, community/policy-level outcomes, and personal-level outcomes (Khodyakov et al., 2011). However, this model did not identify the role of diversity, inclusion, and health equity as core components of partnership characteristics and functioning, did not include health equity as a key outcome or goal of partnerships, and was developed to support research partnerships.

Another model, grounded in academic and community partnerships and CBPR, framed the interplay between contexts, partnership processes, intervention research, and intermediate (e.g., policy environment, sustained partnership, shared power relations in research) and long-term (e.g., community transformation, social justice, health/health equity) outcomes (Wallerstein et al., 2020). While this model includes health equity as an outcome, the inputs and some outcomes are focused on academic-community research partnerships. None of the identified models examined opportunities to assess community engagement and the influence and impact it could have in health and health care policies and programs broadly, incorporating diversity, inclusion, and health equity into the framework. The Organizing Committee felt strongly that an additional model was needed to reinforce existing conceptual models—one that provides a paradigm for the factors needed to assess the quality and impact of meaningful community engagement across various sectors and partnerships and one that simultaneously emphasizes health equity and health system transformation.

The Process and Methodology for Designing the Conceptual Model

To guide the design and refinement of the new conceptual model for assessing meaningful community engagement, the Organizing Committee focused on eight foundational standards. An effective conceptual model will:

Define what should be measured in meaningful community engagement, not what is currently measured. On the premise that society “measures what matters most,” and “what is measured gets done,” the Organizing Committee wanted the conceptual model to focus on the outcomes needed to guide the measures and metrics of meaningful community engagement, not being limited by what already exists in the literature. The development of the conceptual model and areas for assessing meaningful community engagement leveraged the wealth of knowledge, expertise, and experience of the Organizing Committee and were not constrained by whether the metrics were available. This conceptual model represents the Organizing Committee’s aspirational ideal of what matters, what should be measured, and what should be done to support meaningful community engagement.

Be sufficiently flexible to measure engagement in any community. Community goes beyond geography and represents a group of individuals who share common and unifying traits or interests. Community “can refer to a group that self-identifies by age, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation . . . faith, life experience, disability, illness, or health condition; it can refer to a common interest or cause, a sense of identification or shared emotional connection, shared values or norms, mutual influence, common interest, or commitment to meeting a shared need” (WHO, n.d.). The Organizing Committee recognizes the importance of considering intersectionality in defining community, as individuals often belong to multiple and intersecting identities. As such, examples of community could include faith-based organizational networks partnering to improve health across a state, neighbors in a local area seeking environmental changes to improve health and well-being, or a multi-stakeholder network with community-based organizations, primary care providers, and hospitals addressing opioid addiction. The conceptual model should be flexible for use in assessing the impact and influence of engagement in any community.

Define health holistically. The conceptual model should focus on physical and mental health and well-being (Roy, 2018). Often, references to health are only aligned with physical health. The conceptual model should consider that health is not just about being free of disease or infirmity, but that individuals and communities have the right to thrive—to reach “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health” (WHO, n.d.).

Allow the community to see itself in or identify with the language, definitions, and context. The conceptual model should make sense to the community, be usable by the community, and be written in language familiar to the community. The model and the language used in it should allow communities to see themselves in it and emphasize the positive aspects of the community. At the same time, the Organizing Committee recognized that all communities are not monoliths. The conceptual model should be adaptable to the needs of the communities using it—each community and its partners should be able to review the terms and measurement areas presented in the model and collaboratively decide on how to define, apply, modify, or implement them to support their needs.

Embed equity throughout the model. Equity must be the central focus for every decision related to conducting meaningful community engagement and thinking about person-centered health and health care (Simon et al., 2020). Equitable and continued engagement with those traditionally left out of conversations and decision making about the health and health care systems, programs, interventions, and policies that affect them opens a pathway to true health system-wide transformation. The conceptual model should reflect that transformation is not possible without systematically embedding equity into its core components, not just its outcomes.

Emphasize outcomes of meaningful community engagement. The Organizing Committee underscored the importance of the processes, strategies, and approaches used in engagement. Each community is different and wants to be engaged in various and multiple ways. The Organizing Committee recognized that there are myriad toolkits, reports, articles, and examples on how to engage communities. Certainly, more work is needed to understand the influence of and measure these processes to achieve desired outcomes. However, the conceptual model is being developed to support outcome-based accountability. If stakeholders cannot achieve meaningful community engagement based on the selected agreed-upon outcomes, modifying or changing their engagement process should be considered. The main purpose of this conceptual model is to reflect the dynamic relationship between engagement and outcomes, not present or address processes for engagement.

Present a range of outcome options for various stakeholders. As many are committed to assessing the impact of community engagement on health and health care policies and programs, the conceptual model should be relevant to and usable by the range of aforementioned stakeholders. This conceptual model should explain the connection between community engagement and outcomes, and the Committee insisted that a range of options be provided for assessing community engagement to reflect local priorities and interests rather than assume that all communities want or need the same outcomes. In other words, different communities will want to focus on different outcomes. Additionally, the model should support various stakeholders (e.g., federal, state, and local agencies; tribal communities; advocacy and community-based groups; funders, philanthropy, and financiers; academic researchers and institutions; and payers, plans, and industry) looking to evaluate the impact and influence of engagement with the community in health and health care policies and programs.

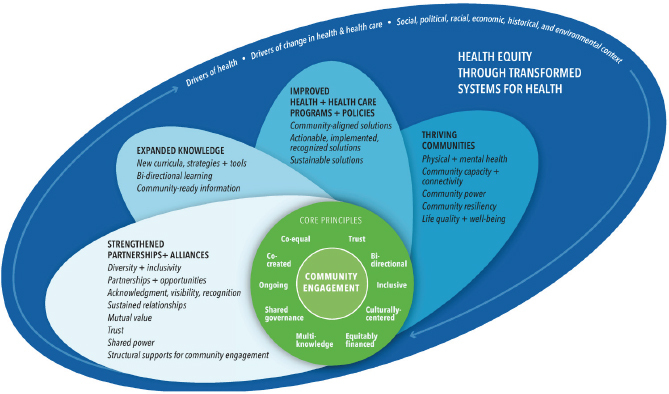

Communicate the dynamic and transformative nature of engagement. The Organizing Committee believed that the conceptual model should place community and community engagement at the center and that all impact and influence should accelerate toward meaningful outcomes that ultimately ensure health equity through transformed systems for health. The image and shape used to depict the relationship between community engagement and outcomes should be dynamic, reflecting the movement toward equity and system transformation when communities are actively and meaningfully engaged.

A three-stage methodological process that leverages these foundational and guiding standards was used to design the conceptual model. In stage one, a subset of 14 Organizing Committee members, including community leaders, researchers, and policy advisors, identified the key overarching components and outcomes to include in the model over the course of several discussions. In stage two, extensive in-depth interviews were conducted with a select group of Organizing Committee members, representing 11 community leaders not involved in stage one, which generated a dozen iterations of the model. The community leaders detailed specific terms, phrases, language, and additional components needed to ensure that the conceptual model was authentic to community perspectives, easy to understand, aligned with other efforts on community engagement, complementary to existing models, and recognizable by those who would benefit the most by using the model. The community leaders also discussed and modified the relationships between the key components and appropriate alignment among outcomes. During this stage, community leaders reviewed outcomes identified in a preliminary literature search to see if elements were missing from the model. Only one additional outcome was added at this time. In stage three, the entire Organizing Committee was reengaged to review, refine, and agree on the resulting conceptual model presented in this commentary.

Review of the Conceptual Model

The conceptual model titled Achieving Health Equity and Systems Transformation through Meaningful Community Engagement, and also known as the Assessing Community Engagement (ACE) Conceptual Model, centers community engagement and core engagement principles (see Figure 1). Four “petals” or “propellers” emanate from the center and radiate from left to right, reflecting major meaningful domains and indicators of impact that are possible with community engagement. Impact in these domains leads to the fundamental goal of health equity and systems transformation and is contextualized by the drivers of health; drivers of change; and social, political, racial, economic, historical, and environmental context. While the ACE Conceptual Model can be viewed as linear and sequential, end users also have the flexibility to focus on specific indicators depending on needs and interests. Below is a description of the details and definitions of all the key components of the conceptual model.

FIGURE 1. A Dynamic Relationship: Achieving Health Equity and Systems Transformation through Meaningful Community Engagement.

Community Engagement

Community engagement is the linchpin or central focus of the conceptual model. Engagement of the community, as defined above, represents both the start and the hub of movement toward outcomes. It is only with community engagement that it is possible to achieve and accelerate progress toward the goal of health equity through transformed systems for health.

Core Principles

The core principles identify attributes that should be present in the process of community engagement. Those involved must ensure that community engagement is grounded in trust, designed for bidirectional influence and information flow between the community and partners, inclusive, and premised on culturally centered approaches. The core principles also include equitable financing, multi-knowledge, shared governance, and ongoing relationships that continue beyond the project time frame and are authentic and enduring. Engagement should be co-created, and participants should be considered coequal. Principle-informed community engagement creates a readiness that can propel teams into productive motion and accelerate engagement outcomes and the ultimate goal of health equity and systems transformation.

Domains and Indicators of Meaningful Engagement

With community engagement and the core principles, it is possible to understand if meaningful engagement is taking place by assessing some or all of the outcomes based on the needs and interests of the community. Therefore, the Organizing Committee developed a taxonomy to classify, describe, and standardize outcomes to assess community engagement (Aguilar-Gaxiola, 2014). The taxonomy used in the ACE Conceptual Model considers domains, indicators, and metrics.

The conceptual model posits four broad categories or domains of measurable outcomes:

Strengthened partnerships and alliances

Expanded knowledge

Improved health and health care programs and policies

Thriving communities

Under each domain are potential and relevant indicators. The conceptual model presents 19 mutually exclusive indicators divided across the four domains. As indicators are not yet quantifiable, each indicator is, in turn, associated with specific metrics. These metrics are the questions that are both supported by results and that can be used to assess if the engagement taking place is meaningful. The Organizing Committee identified metrics associated with meaningful community engagement through a literature review and aligned them with the indicators presented on the conceptual model. Given the space limitations in the conceptual model, only domains and indicators are listed; the metrics identified in the literature and associated with the indicators will be made available later.

Ultimately, with community engagement and its core principles embedded into all collaborations and partnerships, movement and progress should occur in multiple domains and indicators present in the model. Below are explanations on how the Organizing Committee characterized the domains and indicators in the conceptual model.

Strengthened Partnerships and Alliances

The first assessment domain identified by the Organizing Committee relates to strengthened partnerships and alliances, which the Committee defines as how participants emerge from engagement with new or improved relational benefits that are carried forward. This domain also reflects the qualities of leadership that allow alliances and partnerships to be strengthened, and it has the following eight indicators:

Diversity and inclusivity

Partnerships and opportunities

Acknowledgment, visibility, and recognition

Sustained relationships

Mutual value

Trust

Shared power

Structural supports for community engagement

Diversity and inclusivity ask for constant consideration of the representation, inclusion, and lived experiences of those engaged in the efforts. Representation should be intentionally diverse, comprising multicultural, multiethnic, and multigenerational perspectives, particularly those not traditionally invited or involved in improving health and health care policies and programs. Perspectives should reflect the composition of the community, be based on the culture of the community, and reflect multidisciplinary expertise from the community. Diversity and inclusivity should also be reflected in the intentional integration of the interests and, importantly, in knowledge, resources, and other valuable entities from all community members during conversations and deliberations.

Partnerships and opportunities ensure that those engaged are fully benefiting from participation through deepened and mutually supported relationships. This indicator assesses whether participants have benefited from bidirectional mentorship or other forms of professional investment; gained access to new financial or nonfinancial opportunities; received certificates, earned degrees, or otherwise benefited from skills development; or shared and connected to an expanded network of partners, influencers, and leaders.

Acknowledgment, visibility, and recognition reflect how community participants are seen and recognized as contributors, experts, and leaders and can benefit from their participation. This indicator encompasses public acknowledgment of participant contributions and recognizes the legitimacy of the partnership.

Sustained relationships require that the community, institutions, and relevant disciplines maintain continuous and ongoing conversations that are not time-limited or transactional. The community should be engaged at the beginning of an effort and normalized as an essential stakeholder. Involvement and engagement of the community should have depth and longevity.

Mutual value ensures that communities engaged are equitably benefiting from the partnership. This indicator requires balanced engagement between the community and others involved in the partnership, as marked by reciprocity that considers how the community will benefit from, not just contribute to, the effort. The value exchange can be financial or nonfinancial but must be defined by, not prescribed for, the community. Mutual value is grounded in the need for understanding and respect for the community and all partners. It requires valuing the knowledge and expertise of all individuals, agreeing to a shared set of definitions and language, and committing to bidirectional learning.

Trust is a core component of engagement. It requires showing up authentically, being honest, following through on commitments, and committing to transparency in order to build a long-lasting and robust relationship. Genuine partnerships grounded in trust require change on the part of all partners. Trust also requires that entities engaging communities commit themselves to being trustworthy. Mistrust among communities of representatives of health care and other systems is often an adaptive response to historical and contemporary injustice perpetrated by these systems. A foundational component of building trust with communities is demonstrating that community trust is warranted and will not be abused or exploited.

Shared power is fundamental to strong and resilient partnerships with the community. Shared power reflects that community participants are involved in leadership activities such as codesigning and developing the partnership’s shared vision, goals, and responsibilities. It emphasizes that community members have influence and can see themselves and their ideas reflected in the work. Shared power includes true equitable partnership and governance structures that ensure community partners occupy leadership positions and wield demonstrable power equivalent to other partners. Shared power relies on collaborative and shared problem solving and decision making, joint facilitation of activities, and shared access to resources, such as information and stakeholders.

Structural supports for community engagement provide the infrastructure needed to facilitate continuous community engagement. This indicator asks about operational elements for engagement such as established and mutually agreed-upon financial compensation for community partners, requirements for equitable governing board composition, protocols to ensure integration of community partners into grant writing and management, and equitable arrangements for data sharing and ownership agreements, among others. These structural supports ensure the longevity of community engagement and the partnership’s sustainability over time.

Expanded Knowledge

The second domain, expanded knowledge, refers to the creation of new insights, stories, resources, and evidence, as well as the formalization of respect for existing legacies and culturally embedded ways of knowing that are unrecognized outside of their communities of origin. When co-created with community, expanded knowledge creates new common ground and new thinking, and can catalyze novel and more equitable approaches to the transformation of health and health care. The three indicators under expanded knowledge include new curricula, strategies, and tools; bidirectional learning; and community-ready information.

New curricula, strategies, and tools are formal products of community engagement that encapsulate new knowledge and evidence in ways that allow it to be disseminated, accessed, replicated, and scaled. This indicator looks for the development of new curricula, strategies, and tools that enable other partnerships to learn from, build on, and advance new practices in their community engagement.

Bidirectional learning is when the community and partners can collaboratively generate new knowledge, stories, and evidence that reframe how community is described and appreciated. This indicator looks for representations of community that are asset- and resiliency-based, improved cultural knowledge and practices among partners, and broader cultural proficiency and respect for community differences across the partnership. Bidirectional learning equally values all forms of knowledge and wisdom, including stories and lived experience.

Community-ready information is an indicator referring to the creation of actionable findings and recommendations that are returned to the community in ways they understand, value, and can use.

Improved Health and Health Care Programs and Policies

The third domain of the conceptual model is improved health and health care programs and policies. This is the stated goal of many partnerships; however, creating programs and policies that communities want and will use—a prerequisite to effectiveness in real-world settings—requires alignment between those who design programs, services, and policies and those who are expected to use them. Community engagement is essential to creating a productive context for developing solutions that are “fit to purpose,” as well as embraced and championed by those they are designed to serve. The three indicators within this category include community-aligned solutions; actionable, implemented, recognized solutions; and sustainable solutions.

Community-aligned solutions come from and speak to the priorities of the community. This indicator looks for community-defined problems, shared decision making, and cooperatively defined metrics. It also ensures that care models, communication, and solutions are tailored to the community setting and needs.

Actionable, implemented, and recognized solutions are important indicators of success. Results should be visible within and across communities. This indicator looks for solutions that are recognized and endorsed by community members and leverage the assets in the community and the partnerships that produced them; are referenced publicly or within academic literature; and show measurable adoption, growth, and reach.

Sustainable solutions reference new interventions, programs, and policies that can extend past their initial period of support. This indicator looks for residual infrastructure and other resources that remain in the community to support sustainability and further adjust or refine solutions in the future, if needed.

Thriving Communities

As motion accelerates through strengthened partnerships and alliances, expanded knowledge, and improved health and health care policies and programs, assessing the impact of community engagement moves to the fourth domain: thriving communities. The Organizing Committee identified five indicators that suggest engagement has led to thriving communities:

Physical and mental health

Community capacity and connectivity

Community power

Community resiliency

Life quality and well-being

Physical and mental health refer to a “whole-person” definition of health reflected in a community’s physical and mental health status. Physical and mental health include a shared awareness and view of health and health-related activities, self-efficacy in managing health and chronic conditions, shared decision making in health care treatments and priorities, increased confidence and capacity to make decisions that improve an individual’s own health, and increased resiliency.

Community capacity and connectivity speak to growth in skills and capacity of the community, both as individual members and as a whole, to act on its own behalf. This indicator highlights the connectivity between community members and available resources, how engaged and activated community members are, and the investments available to develop new community leaders (e.g., financial, educational, career).

Community power manifests in a sustained paradigm shift that ensures processes and procedures are favored, initiated, and guided by the community. Community power arises with an increased rate of new efforts in the community and new efforts that are defined, initiated, and owned by the community. Community power is also indicated by cultural change—including changes in community dynamics, such as expectations that they will be meaningfully invited to and want to participate in problem solving and priority setting and will experience true equity (e.g., social equity, racial equity, health equity, equity across the drivers of health).

Community resiliency refers to the overall strength of a community and its internal capacity to self-manage. This indicator reflects the ability of the community to recognize and mount a locally relevant response to new adversities and to engage and advance culturally effective strategies to strengthen the community over time. The inherent culture and strengths of the community should be both visible and valued. Importantly, resiliency must not be invoked as a backstop for initiatives that perpetuate trends of a lack of external investments, protections, and support for the community. In other words, resilience is valuable for the internal benefits and strengths that it generates among community members; it is not, however, a replacement for adequate and tangible external investments in the resources that communities need to thrive.

Life quality and well-being refer to improvements in the drivers of health (e.g., education, economic and racial justice, built environment). Life quality and well-being highlight the ability to heal, hold hope for the future, and experience greater joy, harmony, and social equity.

Health Equity through Transformed Systems for Health

When community engagement takes place with core principles guiding its processes and activities, it propels strengthened partnerships and alliances, expanded knowledge, improved health and health care programs and policies, and healthier communities. Improvements in these domains and their associated indicators create motion and catalytic action that moves us toward health equity and well-being through transformed systems.

Drivers of Health; Drivers of Change; and Social, Political, Racial, Economic, Historical, and Environmental Context

The domains and indicators that align with meaningful community engagement and lead to health equity through transformed systems for health are influenced by several contextual factors. Drivers of health, many of which align with the social determinants of health, expand far beyond “traditional” factors like health status and health care into food, transportation, housing, community attributes, affordable child care, and economic and racial justice, among many others. Drivers of health extend to the factors that ultimately influence and impact well-being (Lumpkin et al., 2021; NASEM, 2017; NCIOM, 2020). Drivers of change are the key levers that influence stakeholder action, including data-driven, evidence-based practice and policy solutions; grassroots organizing; regulations; and financial incentives, to name a few. The relevant social, political, racial, economic, historical, and environmental context also underpins all community engagement efforts. It is critical to understand that the dynamic relationship between meaningful community engagement and health and health care policies and programs exists within these structural systems. The Organizing Committee believes that with meaningful community engagement, it is possible to motivate health equity through transformed systems for health and significantly transform and positively alter these contextual factors. A feedback loop is created and reflected through the arrows that move from community engagement, the core principles, and the domains of meaningful engagement through to these contextual factors.

Conclusion

The United States health and health care system reflects origins and a history that did not center communities as true partners in designing, implementing, evaluating, and redesigning the system. The Organizing Committee believes that community engagement is not a supplement to enacting better health and health care policies but rather its foundation. The increased focus on community engagement in the health and health care system over the years represents an opportunity for change to ensure meaningful and sustainable impact. The Organizing Committee believes now is the time to catalyze and accelerate the paradigm shift toward engagement to ensure system transformation and equity. Sustained and widespread changes toward improved health and well-being cannot occur until systems change, and that cannot happen without the engagement of those closest to the challenges and the solutions. The processes to engage the community are essential, and assessing and evaluating the engagement is just as essential to understanding whether and how true impact occurs. Without this critical step, it is impossible to truly understand where to focus efforts to transform the health system. Health and health care stakeholders must measure what matters—community engagement—and ensure that it is meaningful.

The ACE Conceptual Model is only one major element of the work needed to ensure that stakeholders can assess the engagement with community. As part of this effort, the Organizing Committee will also be:

Developing impact stories told through videos and other creative modes to demonstrate how different partnerships have assessed their engagement, the influence that engagement has had on their communities, and the alignment of their outcomes with the domains and indicators in the conceptual model. These impact stories will highlight what is possible and how transformation can take place at a community, hospital, health system, and state level.

Conducting a literature review search using PubMed and other databases, as well as inclusion and exclusion criteria, to identify specific metrics or individual survey questions, tools, or questionnaires (referred to as instruments) that were developed, implemented, or evaluated with community engagement.

Synthesizing assessment instrument summaries that identify instruments that align with the domains and indicators in the conceptual model. These summaries, based on findings from a literature review, will include information on how engagement was used to develop or implement the instrument, populations, and communities involved in using the instrument, psychometric properties (i.e., validity, reliability, and feasibility), the instrument’s questions, and alignment with the domains and indicators in the conceptual model.

Developing a framework to support end users who want to measure community engagement using the conceptual model and instruments identified.

The ACE Conceptual Model presented in this commentary is drawn from the active engagement and embedding of perspectives from community leaders, academics, researchers, and policy makers. While testing the conceptual model is needed to understand the most effective context and circumstances for its use, this model presents an additional resource for end users to support the assessment of meaningful community engagement. Further, the model reflects what the Organizing Committee believes are necessary elements of meaningful engagement that should be measured and evaluated early and often. This model is evolving and not stagnant, much like the movement depicted in the shape of the model. It represents a guiding framework to catalyze meaningful community engagement and radically propel the U.S. toward health equity through systems transformation.

Acknowledgments

The Organizing Committee would like to thank Tomoko Ichikawa, Clinical Professor of Design, IIT Institute of Design, Illinois Institute of Technology, for her information design support on the conceptual model.

Merri Sheffield, BECAUSE, Inc, Chuck Conner, West Virginia Prevention Research Center Community Partnership Board (until March 2021), and Al Richmond, Campus Community Partnership for Health (until March 2021), are part of the Organizing Committee, and they provided perspectives on the conceptual model through in-depth interviews. The authors would like to thank them for their input during this process.

The authors would like to thank Becky Payne, Rippel Foundation; Lauren Fayish, Laura Forsythe, Esther Nolton, Kristin Carman, Vivian Towe, Kate Boyd, Christine Broderick, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; and Thomas Concannon, Sameer Siddiqi, and Alice Kim, the RAND Corporation; for their thoughtful contributions to this paper.

The development of this paper was supported by a grant from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. For more information, visit www.rwjf.org.

Funding Statement

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily of the authors’ organizations, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). The paper is intended to help inform and stimulate discussion. It is not a report of the NAM or the National Academies.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosures: Dr. Michener discloses serving as Principal Investigator for the Practical Playbook™ and as consultant for HHS, OAHS, NIH, CDC, HRSA, UC Davis, and Rockefeller University.

Contributor Information

Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, University of California, Davis.

Syed M. Ahmed, Medical College of Wisconsin

Ayodola Anise, National Academy of Medicine.

Atum Azzahir, Cultural Wellness Center.

Kellan E. Baker, Whitman-Walker Institute

Anna Cupito, National Academy of Medicine.

Milton Eder, University of Minnesota.

Tekisha Dwan Everette, Health Equity Solutions.

Kim Erwin, IIT Institute of Design.

Maret Felzien, Northeastern Junior College.

Elmer Freeman, Center for Community Health Education Research and Service.

David Gibbs, Community Initiatives.

Ella Greene-Moton, University of Michigan School of Public Health.

Sinsi Hernández-Cancio, National Partnership for Women & Families.

Ann Hwang, Harvard Medical School.

Felica Jones, Healthy African American Families II.

Grant Jones, Center for African American Health.

Marita Jones, Healthy Native Communities Partnership.

Dmitry Khodyakov, RAND Corporation and Pardee RAND Graduate School.

J. Lloyd Michener, Duke School of Medicine.

Bobby Milstein, ReThink Health.

Debra S. Oto-Kent, Health Education Council

Michael Orban, Foundation for Veterans.

Burt Pusch, Commonwealth Care Alliance.

Mona Shah, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Monique Shaw, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Julie Tarrant, National Academy of Medicine.

Nina Wallerstein, University of New Mexico.

John M. Westfall, American Academy of Family Physicians

Asia Williams, National Academy of Medicine.

Richard Zaldivar, The Wall Las Memorias Project.

References

- 1.Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Ahmed S, Franco Z, Kissack A, Gabriel D, Hurd T, Ziegahn L, Bates NJ, Calhoun K, Carter-Edwards L, Corbie-Smith G, Eder MM, Ferrans C, Hacker K, Rumala BB, Strelnick AH, Wallerstein N. Towards a Unified Taxonomy of Health Indicators: Academic Health Centers and Communities Working Together to Improve Population Health. Academic medicine. Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2014;89(4):564–572. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carman KL, Workman TA. Engaging Patients and Consumers in Research Evidence: Applying the Conceptual Model of Patient and Family Engagement. Patient Education and Counseling. 2017;100:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Principles of Community Engagement. 2011. [October 15, 2021]. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Facilitating Power. The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership. 2020. [October 15, 2021]. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/facilitatingpow-er/pages/53/attachments/original/1596746165/CE2O_SPECTRUM_2020.pdf?1596746165 . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones F, Ohito E, Jones A, Lizaola E, Mango J. An Exploration of the Effect of Community Engagement in Research on Perceived Outcomes of Partnered Mental Health Services Projects. Society and Mental Health. 2011;1(3):185–199. doi: 10.1177/2156869311431613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lumpkin JR, Perla R, Onie R, Selig-son R. Health Affairs. 2021. [October 15, 2021]. What We Need To Be Healthy—And How To Talk About It. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210429.335599/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.North Carolina Institute of Medicine (NCIOM) Healthy North Carolina 2030: A Path Toward Health. Morrisville, NC: North Carolina Institute of Medicine; 2020. [October 15, 2021]. https://nciom.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/01/HNC-REPORT-FINAL-Spread2.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy B, Riley C, Sears L, Rula EY. Collective Well-Being to Improve Population Health Outcomes: An Actionable Conceptual Model and Review of the Literature. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2018;32(8):1800–1813. doi: 10.1177/0890117118791993. https://doi. org/10.1177/0890117118791993 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon M, Baur C, Guastello S, Ramiah K, Tufte J, Wisdom K, Johnston-Fleece M, Cupito A, Anise A. NAM Perspectives. National Academy of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2020. Patient and family engaged care: An essential element of health equity. Discussion Paper. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallerstein N, Oetzel JG, Sanchez-Young-man S, Boursaw B, Dickson E, Kastelic S, Koegel P, Lucero JE, Magarati M, Ortiz K, Parker M, Peña J, Richmond A, Duran B. Engage for Equity: A Long-Term Study of Community-Based Participatory Research and Community-Engaged Research Practices and Outcomes. Health Education & Behavior. 2020;47(3):380–390. doi: 10.1177/1090198119897075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution. [October 15, 2021]. n.d. https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution . [Google Scholar]