Abstract

Objective

To identify the attitudes and perspectives of speech pathologists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists on using telehealth videoconferencing for service delivery to children with developmental delays.

Design

Systematic Literature Review.

Method

An electronic search of databases Scopus, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PEDro, Speechbite, OTseeker and ScienceDirect was undertaken in October 2020. Articles were compared with eligibility criteria by 2 authors. All articles were appraised for quality and level of evidence.

Findings

Fourteen studies were deemed to be eligible. Results were synthesised using a narrative analysis. The themes identified were technology, self‐efficacy, replacement of face‐to‐face services, time management, relationships, access and family‐centred care. Each of these themes was seen as both a potential barrier and a facilitator when trying to provide services via telehealth.

Conclusions

The results in this review cannot be generalised due to small sampling size, low response rates, lack of maximum variation sampling and under‐representation of occupational therapists and physiotherapists. Study design was either mixed‐methods survey or interview or only survey or interview. Risk of bias in studies was high. Further research is required including comparison studies and cost‐benefit analysis.

Keywords: attitudes, occupational therapy, perspectives, physiotherapy, speech pathology, telepractice and children

What is already known on this subject:

Evidence supports the use of telehealth for allied health service delivery to children with disabilities; however, service gaps are still present in Australia

Perspectives of patients are often reported; however, allied health professional perspectives are lacking

Perspectives of clinicians are important to predict adoption of telehealth services

What this study adds:

Speech pathologists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists perceive both barriers and facilitators to use of telehealth for service delivery to children

Occupational therapists and physiotherapists are under‐represented in the evidence

The quality of evidence is insufficient to generalise to the population of interest

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Developmental delay

Developmental delay occurs when children do not meet developmental milestones at the same rate as their age‐matched peers. 1 This could be for any reason, including a syndrome, dystrophy and birth trauma, or could be idiopathic. Allied health services in this group aim to facilitate social participation and inclusion. 2 They work to improve required skills to facilitate a healthy progression into adulthood and facilitate engagement within the community by use of interactive sessions requiring visual assessment, interaction in the environment, speech and cognitive skills. 3 , 4 These early‐intervention services improve children's health trajectory. 5 However, children in rural and remote areas have reduced participation in these services compared with children in major cities and consequently have poorer health outcomes. 6

1.2. Telehealth, a potential solution to rural service gaps

Allied health services in rural and remote locations are lacking compared with major cities; the number of allied health professionals per capita is significantly dropping with increased remoteness. 7 The consequence of this scenario is poorer health outcomes in rural and remote areas and increased travel for both allied health professionals and patients. 8 , 9 Some patients even go so far as to move permanently to a major city when requiring ongoing specialist services. 7 Compounding the problem of reduced access to allied health is the issue of those few professionals available being unable to provide specialist services due to the lack of infrastructure, lack of specialist knowledge, funding priorities and staffing. 7 , 10

Telehealth is a potential solution to service gaps and inaccessibility to allied health care. 11 Telehealth is the provision of health services over a geographical distance using telecommunications technology. 12 Telehealth is an umbrella under which various technologies sit including emails, phone calls and videoconferencing and can be used for direct client services, training and administration. 13 Videoconferencing is the most appropriate way to deliver real‐time remote services to children with developmental delay due to the play‐based nature of therapy and high visual and verbal communication needs in this group. 14 Therefore, only telehealth videoconferencing is being considered in this review. Future references to telehealth indicate telehealth videoconferencing unless otherwise specified.

Growing evidence including systematic reviews supports telehealth to address service gaps in rural Australia. 15 , 16 , 17 These reviews found that telehealth could provide reduced costs, reduced inconvenience, improved access and improved clinical outcomes to rural Australians. However, there are still barriers to widespread adoption of telehealth including lack of infrastructure, training and motivation and lack of research with high‐quality methodologies. 11

1.3. Predicting adoption of telehealth

Telehealth, just as it does for adult health services, offers a solution to this inequity in children's health. 11 The efficacy of telehealth as a delivery model for allied health services for children with disabilities was shown to be effective in a systematic review of randomised controlled studies. 18 The children included in studies in this systematic review meet the definition of developmental delay. 1 Occupational therapy and physiotherapy were poorly represented in the review. 18 Wales et al 19 found evidence supporting speech pathology delivered via telehealth in their systematic review but found that the evidence was generally of poor quality. Further studies are required to determine whether the use of telehealth is an effective way for speech pathologists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists to assess and treat children.

While the first step is to consider the efficacy of telehealth as a delivery method, efficacy becomes redundant if stakeholders are not willing to use it. The technology acceptance model (TAM) proposed by Davis 20 discusses that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are predictors of whether a person will accept a technology. Adoption of telehealth services is dependent on clinician satisfaction, perception of usefulness and ease of use. 20 Therefore, clinician perspectives are important, but they are rarely studied. Research on perspectives of telehealth primarily focuses on patient and family satisfaction; also an important predictor of success of telehealth. 21

It is insufficient that patients alone are accepting of telehealth; clinician perspectives should also be investigated. Informal conference discussions have shown that access to appropriate technology, organisational support and training were clinicians' most perceived needs when considering adopting telehealth. 22 Further rigorous research is required to consolidate these preliminary findings.

1.4. COVID‐19

Until 2020, accessing rural populations was the focus of telehealth research in Australia. The COVID‐19 pandemic prompted significant changes to our model of health care delivery. The Australian Government Department of Health 23 introduced Medicare payments for telehealth services in 2020. Distance from health care services bears very little weight on this change. Instead, telehealth is being used to reduce exposure to infection for front‐line workers. 23 Camden and Silva 22 reported that pre–COVID‐19 only 4% of allied health professionals from 76 countries used telehealth in their work with children, whereas after the onset of COVID‐19, 70% use telehealth. The influx of therapists using telehealth presents a unique opportunity to identify problems and solutions that can improve telehealth services to create better equity across allied health services in rural Australia post–COVID‐19.

1.5. Knowledge gap

Numerous gaps are evident in the current research of telehealth in children with developmental delays and disabilities. There is a lack of randomised controlled studies and systematic reviews to support the efficacy of telehealth to deliver allied health services for this population. There is also a lack of understanding of what barriers and facilitators allied health professionals face when using telehealth to deliver services to children with developmental delays. This systematic review attempts to address the latter.

While allied health encompasses many health professionals, in this review the term refers only to physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech pathologists. 2 The reason for including these and excluding others is the similarity of these professions in the patient group, interventions, practice and collaboration. 3 , 4 , 5 It was felt that they would be sufficiently similar to enable comparisons at the analysis stage. 3 , 4 , 5

1.5.1. Objective

To identify the attitudes and perspectives of allied health professionals (speech pathologists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists) towards using telehealth for service delivery to children with developmental delays.

2. METHOD

2.1. Design

This is a systematic literature review completed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. 24 The review protocol is registered with PROSPERO: CRD42020210996.The authors are not aware of any conflicts of interest.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) studies in English; (b) studies published from any year up until 2021; (c) studies including videoconferencing to deliver services to clients; (d) empirical, quantitative, qualitative, mixed‐methods and original studies; (e) studies that included perspectives of allied health professionals who were of physiotherapy, occupational therapy or speech pathology disciplines; and (f) studies where the group receiving services were children with developmental delay.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) studies not in English; (b) literature reviews; (c) pilot studies; (d) sought perspectives on telehealth that were not videoconferencing, for example online exercise programs and Web‐based games; and (e) studies where interventions were provided only to adults.

2.3. Search strategy

An electronic search of databases Scopus, MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, PEDro, OTseeker, Speechbite and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) was conducted on 11 October 2020 and updated on 8 June 2021. The JCU library staff were consulted to identify key words and develop search strategies for each database. Searches varied due to the constraints of each database.

-

Medline and Scopus were searched using the following terms

("speech patholog*" OR "speech‐language" AND "speech therap*" OR "speech and language" OR "physiotherap*" OR "physical therap*" OR "occupational therap*") AND (perspective* OR attitude*) AND (telehealth OR telepractice OR teletherapy OR telerehab* OR telemedicine) AND (child* OR paediatric OR pediatric)

-

ScienceDirect was searched using the following terms

(perspective OR attitude) AND (telehealth OR telepractice OR teletherapy OR telerehabilitation OR telemedicine) AND ("allied health") AND child

CINAHL was automatically searched for synonyms of the key words used for the ScienceDirect search. MESH headings and subject headings were checked

PEDro was searched by selecting paediatrics as the subdiscipline and using the terms telepractice and telehealth in the abstract/title search bar. All search terms were matched with AND

Speechbite was searched by entering ‘telehealth’ and ‘telemedicine’ as keywords and selecting children in the age option

OTseeker was searched by searching using the terms ‘telehealth’ OR ‘telemedicine’ AND ‘child*’

All databases were limited to English‐only articles as none of the authors have a second language. To minimise the risk of missing relevant articles, a search was conducted of web pages and searching citations of included articles. Systematic and literature reviews from database searches that appeared relevant were hand‐searched for articles meeting eligibility criteria.

2.4. Study selection

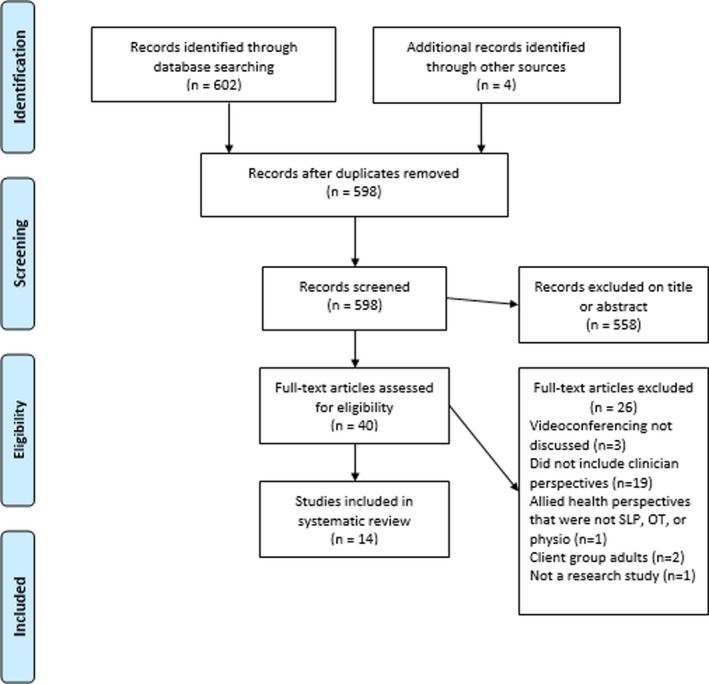

Articles were exported into Endnote and duplicates removed. The title and abstracts of the remaining articles were screened by Author 1 and Author 2 to find relevant full‐text articles for further screening. Full‐text articles were assessed against the eligibility criteria by Authors 1 and 2 independently and disagreements resolved by discussion with the eligibility criteria for reference. Study selection is outlined in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flowchart

2.5. Methodological quality

Assessment of article quality was undertaken using the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (CCAT). 25 This tool was chosen as it has been shown to be reliable for all research designs. The CCAT consists of eight categories that can be scored from 0 to 5, with a total score of 40 being the best possible score. The categories are the preamble, introduction, design, sampling, data collection, ethical matters, results and discussion. The CCAT has an intra‐class correlation coefficient of 0.83 for consistency and 0.74 for total agreement. 25 It has significant weak‐to‐moderate positive correlations (Kendall's τ 0.33‐0.55) when compared to other critical appraisal tools. 26 Author 1 and Author 2 independently appraised the articles, and any differences between results were discussed to reach a consensus. The CCAT was also used to identify any bias in the articles so that this was considered in reviewing the findings (Table 3). Studies were compared with the evidence hierarchy presented by Ackley et al. 27 This hierarchy was chosen as it provides a level for survey and qualitative designs.

TABLE 3.

Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool scores

| Study author and year | Preliminaries | Introduction | Design | Sampling | Data collection | Ethical matters | Results | Discussion | Total score and % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

McAllister, Dunkley and Wilson 39 2008 |

2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

22/40 55% |

|

Dunkley, Pattie, Wilson and McAllister 41 2010 |

3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

30/40 70% |

|

Hill and Miller 13 2012 |

5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

33/40 83% |

|

Tucker 40 2012 |

4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

30/40 75% |

|

Tucker 42 2012 |

4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

34/40 85% |

|

Hines, Ramsden, Martinovich and Fairweather 37 2015 |

4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

26/40 65% |

|

Edirippulige et al 9 2016 |

4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

26/40 65% |

|

Ashburner, Vickerstaff, Beetge and Copley 35 2016 |

4 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

29/40 73% |

|

Iacono et al 31 2016 |

3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

24/40 60% |

|

Akamoglu, Meadan, Pearson and Cummings 34 2018 |

4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

31/40 78% |

|

Campbell, Theodoros, Russell, Gillespie and Hartley 36 2019 |

5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

33/40 83% |

|

Johnsson, Kerslake and Crook 38 2019 |

3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

21/40 53% |

|

Rortvedt and Jacobs 33 2019 |

5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

31/40 78% |

|

Raatz, Ward and Marshall 32 2020 |

4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

36/40 90% |

2.6. Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted by Author 1. The data extracted from each study were organised into a table with categories for author, date of publication, location of study, study design, participants (including the number of participants and professions), patient groups, objectives and findings. This table was developed into the study characteristic table (Table 2). Data were sought and extracted on quantitative and qualitative items including perspectives of barriers and facilitators such as cost, time and feasibility.

TABLE 2.

Study characteristics

| Author and year | Study design and setting | Sample and demographics | Patient population | Objectives of the study | Data analysis | Results | Bias considered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

McAllister, Dunkley and Wilson 39 2008 |

Qualitative; semi‐structured interviews Rural New South Wales, Australia |

4 speech pathologists, 24‐45 y old, all female, clinical experience <3 to >15 y | Mixed adult and paediatric caseload |

|

Thematic content analysis |

Barriers: No direct interpersonal contact (lack of physical touch), lack of infrastructure, lack of training and support, lack of confidence, lack of time to implement telehealth Facilitators: Time saving for client and clinician, cost saving, improves access |

No |

|

Dunkley, Pattie, Wilson and McAllister 41 2010 |

Quantitative; cross‐sectional survey Rural New South Wales, Australia |

43 residents, 25‐54 y old, 41 female, 2 male 49 speech pathologists, 20‐54 (mode 25‐29) y old, 47 female, 2 male, clinical experience 0.5‐20 y |

Mixed adult and paediatric caseload |

|

Descriptive statistics Comparison of survey results |

Barriers: Should not replace face‐to‐face, need for training and support, lack of physical touch, personal finances Most SLPs reported they were not confident with videoconferencing |

No |

|

Hill and Miller 13 2012 |

Mixed‐methods; cross‐sectional survey with some qualitative questions Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Northern Territory and Western Australia, Australia |

57 speech pathologists, <45 y old, 98% female, clinical experience 0.5‐30 y (average 10.9) | Mixed adult and paediatric caseload |

|

Descriptive statistics Thematic analysis |

Barriers: technology failures, lack of IT support, lack of telehealth infrastructure, inadequate training Facilitators: Access, time efficiency for client and clinician, reduced costs, caseload management, client‐focused Descriptions: 50% had used videoconferencing |

No |

|

Tucker 40 2012 |

Qualitative; semi‐structured interviews USA—school‐based |

5 speech pathologists, clinical experience 11‐36 y, experience with telehealth 9 mo‐3 y Age and sex not reported |

School‐aged children |

|

Thematic analysis |

Barriers: Technology barriers, inadequate training for SLPs and e‐helpers, time to implement program, lack of physical touch, inappropriate for students with profound disabilities Facilitators: facilitates student learning, collaboration, access to speech pathologists, benefits families |

Yes (selection) |

|

Tucker 42 2012 |

Quantitative; cross‐sectional survey USA—school‐based |

170 speech pathologists, clinical experience 1‐25+ y Age and sex not reported |

School‐aged children |

|

Descriptive statistics | 6% had used telepractice, 86% had training before providing telepractice service, 70% thought training required, 14% agreed that rapport could be established via telepractice, and 30% interested in providing telepractice in schools | Yes (selection) |

|

Hines, Ramsden, Martinovich and Fairweather 37 2015 |

Qualitative; semi‐structured interviews Sydney, Australia—school‐based |

15 speech pathologists, 24‐54 y old, 9 participants with <5 y clinical experience, experience with telehealth in the last year Sex not reported |

School‐aged children |

|

Thematic analysis | Positive attitudes towards therapeutic relationships with children, collaboration with teachers and parents, adequacy of technology and access to support and learning | No |

|

Edirippulige et al 9 2016 |

Mixed‐methods; qualitative semi‐structured interviews and quantitative analysis of locations by geomapping. Queensland, Australia |

329 patients with cerebral palsy, 203 male, 126 female, mean age 9 y 13 clinicians including 4 occupational therapists, 2 physiotherapists and 2 speech pathologists. 92% had experience with telehealth Age, sex and years of clinical experience not reported |

Children with cerebral palsy |

|

Descriptive statistics—qualitative responses and frequency reported |

Geomapping: average 836km to Brisbane appointments and average 173km to outreach appointments Barriers: disrupts clinician‐client rapport, technology barriers, should not replace face‐to‐face as stand along treatment, impractical for certain assessments, privacy Facilitators: Pre/post‐op planning over distance, adjunctive treatment, maintaining relationships over distance, support and training, privacy |

No |

|

Ashburner, Vickerstaff, Beetge and Copley 35 2016 |

Qualitative; semi‐structured interviews Queensland, Australia |

4 mothers, 2 special education teachers, 2 classroom teachers, 2 occupational therapists, 2 speech pathologists. Clinical experience 6 wk to 20 y, all had experience with telehealth Age and sex not reported |

Children with autism spectrum disorder, aged 3‐7 y |

|

Thematic analysis |

Barriers: Technical difficulties, should not replace face‐to‐face Facilitators: Reduces cost of time and travel for client and clinician, upskills parents and providers, flexible, access for families, stakeholder collaboration |

Yes (response) |

|

Iacono et al 31 2016 |

Mixed‐methods; cross‐sectional quantitative survey and qualitative interviews Australia |

Survey; 15 mothers, 19 practitioners including 5 speech pathologists, 4 occupational therapists Interviews; 8 practitioners (type not described) Age, sex and years of clinical experience not reported |

Children with autism spectrum disorder |

|

Descriptive statistics and thematic analysis |

Barriers: technology issues, poor confidence, inappropriate for children with autism, interferes with rapport Facilitators: improves travel time, children seen in familiar environment Descriptive: 57.9% of practitioners had used videoconferencing, 33.3% agreeable to using it for intervention, 73% believed time saving for family |

No |

|

Akamoglu, Meadan, Pearson and Cummings 34 2018 |

Qualitative; semi‐structured interviews and questionnaire USA |

15 speech pathologists, all female, 30‐55 y old, experience with telepractice 1‐5 y Clinical experience not reported |

Children in school and home settings |

|

Thematic analysis |

Barriers: reliance on ‘e‐helpers’ such as parents and staff, selecting appropriate children for telehealth, lack of physical touch Facilitators: building rapport with families in remote areas |

No |

|

Campbell, Theodoros, Russell, Gillespie and Hartley 36 2019 |

Qualitative; semi‐structured interviews Queensland, Australia |

39 stakeholders including 3 occupational therapists and 3 speech pathologists, 4 male, 35 female, 18‐74 y old, most 30‐44 (n = 21) Clinical experience not reported. Age and sex not split into stakeholder groups. |

Children receiving BUSHkids (remote health scheme) |

|

Thematic analysis |

Barriers: technology programs, poor relationships and lack of physical touch, self‐efficacy, inferior relationships, clinical information missed, children would not be able to participate, privacy Facilitators: access, benefits families, technology barriers can be solved, telehealth supported by partnerships |

Yes (generalisability) |

|

Johnsson, Kerslake and Crook 38 2019 |

Qualitative; semi‐structured interviews New South Wales, Australia |

21 stakeholders including 11 parents, 6 local support team members and 4 teletherapists (1 occupational therapist, 1 speech pathologist, 1 psychologist, 1 special educator) Teletherapists had 2 y of clinical experience, no telehealth experience Sex and age not reported |

16 children with ASD from 2 to 12 y old |

|

Thematic analysis |

Barriers: limits goals that require physical interaction (lack of physical touch), local staff changes, additional in‐person services would help with rapport Facilitators: training builds confidence, adequate technology, collaboration, access to specialist services, similar to in‐person sessions, fills the gap in regional services |

No |

|

Rortvedt and Jacobs 33 2019 |

Mixed‐methods; quantitative cross‐sectional survey with some qualitative questions USA |

27 stakeholders including 11 occupational therapists (others education staff) Experience 5‐30+ y, most 15‐30 (n = 11) |

School‐aged children |

|

Descriptive statistics and thematic analysis |

Barriers: logistics, lack of physical touch, privacy concerns, Facilitators: logistics (less travel), collaboration, better access to OTs, better access for homebound students Descriptive: 28% likely to adopt telehealth, 14% unlikely, remaining preferred not to answer. 42% were interested in telehealth education, 42% were not and the remaining did not know |

No |

|

Raatz, Ward and Marshall 32 2020 |

Mixed‐methods; quantitative cross‐sectional survey with some qualitative questions Australia, all states and territories excluding Northern Territory |

84 speech pathologists, <30 to >50 y old, most 30‐50 (n = 47), 26 clinician level, 54 senior clinician level, 4 management level Sex not reported |

Children requiring feeding services |

|

Descriptive statistics and thematic analysis |

Barriers: technology failure, safety and efficacy of feeding service, lack of training and experience, family perceptions Facilitators: reduced travel times and costs, benefits families (by reducing family burden of attending appointments), naturalistic environment, potential to increase services, access to clinical support Descriptive: 41% interested in using telehealth for feeding support, 20% had used telehealth for feeding support, and 4% felt no feeding services could be provided via telehealth |

Yes (selection) |

2.7. Data synthesis

Narrative synthesis was chosen as the most appropriate way to analyse the diverse study designs and manage inconsistencies across outcomes measured. 28 The narrative approach seeks to use storytelling to gather evidence of why a change should be made and to provide a trustworthy synthesis. 29 Popay et al 29 outlined 4 steps for a narrative synthesis. The first step, developing a theory of the intervention, was not appropriate as the studies primarily explored perceptions rather than an intervention. The second step, developing a preliminary synthesis of the findings, was followed during data extraction. The third step, exploring relationships in the data, was followed using a thematic analysis. To allow the story to emerge from the quantitative and qualitative data, the included articles were read and reread by Author 1 and Author 2. Organisation into themes was thought to be the best way to bring together the findings from each study. 29 Quantitative data were transformed to qualitative to allow for coding and generation of themes. Author 1 leads the assignment of codes before meeting with Author 2 to discuss possible interpretations of the codes before agreeing upon them. And finally, the fourth step, assessing the robustness of the synthesis, was followed by undertaking a thorough critical appraisal as previously discussed.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study screening and selection

The initial electronic search yielded 608 studies (Table 1). Following the removal of duplicates, 598 articles remained. They were then screened by title and abstract with 558 being excluded due to irrelevance, and the remaining 40 articles were accessed in full text. Reasons for exclusion were not including videoconferencing, not discussing clinician perspectives, participants did not include speech pathologists, occupational therapists or physiotherapists or did not relate to children with developmental delays.

TABLE 1.

Search results

| Database | Search fields | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | Title, abstract and keywords | 411 |

| CINAHL | Subject headings | 1 |

| MEDLINE | Title, abstract and keywords | 12 |

| PEDro | Title, abstract, subdiscipline | 8 |

| Speechbite | Title, abstract, keywords | 14 |

| OTseeker | Title, abstract, keywords | 0 |

| ScienceDirect | Title, abstract and keywords | 156 |

| Grey searching | Reference lists and citations | 4 |

Fourteen of these articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. The PRISMA 30 flowchart used for study selection is shown below (Figure 1).

3.2. Study characteristics

Five studies used a mixed‐methods design. 9 , 13 , 31 , 32 , 33 Hill and Miller, 13 Raatz et al 32 and Rortvedt and Jacobs 33 used a cross‐sectional survey design with some open‐ended questions for thematic analysis. Iacono et al 31 used both cross‐sectional survey and semi‐structured interviews using descriptive statistics and thematic analysis, respectively, and Edirippulige et al 9 used a qualitative interview and described locations using geomapping. The geomapping component has not been analysed in this systematic review.

Seven studies used a qualitative design employing semi‐structured interviews. 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 Two studies used cross‐sectional survey design. 39 , 41 All studies were level VI on the evidence hierarchy. 27 Table 2 summarises study characteristics.

3.3. Risk of bias

Bias was assessed using the CCAT and is presented in Table 3. 25 There is a high risk that bias in data collection instruments was present in 12 of 14 studies as only Tucker 40 , 42 pilot tested their survey and interviews prior to data collection. Akamoglu, Meadan, Pearson and Cummings 34 acknowledged lack of validity and reliability of their survey as a limitation of their study. Bias in sampling was acknowledged by 3 studies. 32 , 35 , 36 Campbell et al 36 reported that they had no Indigenous respondents and that this did not reflect the population. While the above 3 studies considered sampling bias a risk, it appears that while it went unacknowledged, it was also a risk in the other studies as none of the included studies had a random sample. Raatz et al 32 reported risk of selection bias as they considered it possible that their sample might have an interest in telehealth and therefore chose to respond to the survey. Akamoglu et al 34 and Tucker 40 , 42 required their participants to be experienced in telehealth; consequently, clinicians who deliberately avoided telehealth were not included. This might lead to a bias in under‐reporting of barriers to the use of telehealth. Ashburner et al 35 discussed that since the telehealth program was at no cost to the families, respondents might have been swayed to respond positively. Reporting bias was a risk in at least 4 studies that reported receiving funding from telehealth‐motivated organisations. 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 Studies that acknowledged bias generally scored higher using the CCAT than those that did not (Table 3).

3.4. Participant characteristics

Speech pathologists made up most participants (n = 412). Occupational therapists were less well represented than speech pathologists (n = 25), and physiotherapists had the smallest representation (n = 2). The studies by Dunkley et al, 41 and McCallister et al 39 shared a participant pool. Age ranges and sexes of participants were not consistently reported. Studies that did report sex found that participants were more than 90 per cent female. 34 , 36 Familiarity with telehealth was reported for some but not all studies. Reported familiarity ranged from 25 per cent by McCallister et al 39 to 100 per cent by Akamoglu, Meadan, Pearson and Cummings. 34 Clinical experience was not consistently reported.

3.5. Patient demographics

Three studies reported a mix of paediatric and adult caseload. 13 , 39 , 41 Five studies reported that children were mainly seen in a school setting. 33 , 34 , 37 , 40 , 42 Three studies report that children had autism spectrum disorder (ASD). 31 , 35 , 38 One study described the client group as children with cerebral palsy. 9 The patient group for Raatz et al 32 all had feeding difficulties. Finally, Campbell et al 36 sought perceptions from therapists involved in a remote health scheme with services for both Indigenous and non‐Indigenous children. All studies included some children requiring non‐acute services for developmental delays.

3.6. Synthesis of themes

Themes identified related either to allied health professionals or to families receiving the service. Allied health professional themes included technology, self‐efficacy, face‐to‐face services, time management and relationships. Themes identified for families included access and family‐centred care. Each of these themes was seen as both a potential barrier and a facilitator when trying to provide services via telehealth.

3.6.1. Allied health professionals

Technology

Technology failure or lack of technology infrastructure was identified in 7 studies as a barrier to the provision of services via telehealth, 13 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 while one study 38 identified appropriate access to support and technology as a facilitator to providing services via telehealth.

Technology failure was specified as Internet dropout by Iacono et al, 31 a lack of telehealth infrastructure by McAllister et al 39 and time‐lag, computer crashing and screen freezing by Tucker. 40 Dunkley et al 41 reported that clinicians held the belief that families did not have the computer literacy or access to use telehealth. However, this belief was shown to be unsupported by family's perceptions. 41 One resident commented ‘like everyone else, we've got a fax and a computer and the internet [satellite connection] and all that’. 41 ,p339 Three studies reported that technology did not negatively impact the use of telehealth as clinicians found that issues could be worked through, 36 that technology was not an issue 38 and in one case that technology facilitated telehealth. 37

Self‐efficacy

Participants in 6 studies identified lack of self‐efficacy related to poor confidence or inadequate training as a barrier to service delivery via telehealth. 13 , 31 , 36 , 39 , 40 , 41 Adequate training, facilitating improved self‐efficacy, was identified by 3 studies, resulting in easier use of telehealth as a service delivery method. 9 , 13 , 38 Self‐efficacy and training are closely linked; training improves self‐efficacy in whichever skill is trained. 43 Raatz et al 32 reported that only 27% of its participants had received training in telehealth. Three studies included in the review identify support and training as facilitators to the use of telehealth. 9 , 13 , 38 Johnsson et al 38 reported that training built clinician confidence. Hill and Miller 13 reported that 79% of respondents recommended further professional development and 66% recommended demonstrations by clinicians to enable skills in telehealth to be developed.

Replacement for face‐to‐face services

The inadequacy of telehealth to replace face‐to‐face therapy was reported as a barrier in 10 studies. 9 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 40 , 41 Two reasons reported for this were the inappropriateness for certain client groups 31 , 32 , 34 , 40 and the lack of physical touch available in a telehealth appointment. 33 , 34 , 36 , 38 , 40 Three studies simply referred to unsuitability of telehealth as a replacement to face‐to‐face therapy. 9 , 35 , 41

While this theme was predominantly reported as a barrier, 9 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 40 , 41 there were some positive perceptions. Two studies reported participant views that telehealth was similar to or even better than face‐to‐face services in some situations. 9 , 38 Edirippulige et al 9 reported views that telehealth was facilitative of pre‐ and post‐operation planning for children with cerebral palsy and that telehealth was an effective adjunct to face‐to‐face services.

The 4 studies that found clinicians perceived that some client groups could not be provided services via telehealth specified those client groups as children with profound disabilities, 40 those with ASD and other communication disorders 31 , 34 and children with feeding difficulties. 32 Concerns were that children with profound disabilities would not physically be able to use the videoconferencing technology 40 and that children with communication difficulties could not engage through the screen. 31 , 34 Raatz et al 32 also reported concerns around efficacy and safety of telehealth for children with feeding difficulties.

Time management

Participants in 4 studies reported beliefs that telehealth negatively impacted time management as they did not have time to implement a telehealth service, 9 , 33 , 34 , 39 while 4 studies reported beliefs that telehealth positively impacted time management by reducing clinician travel time. 13 , 32 , 35 , 39

Organising and scheduling telehealth was thought to be a burden on already heavy workloads due to the preparation of materials and technology. 9 Clinicians also believed that without sufficient support by their organisation, time and costs would fall to the individual clinician. 39 Two further studies reported perceptions that school‐based appointments would have to be set up and supervised by a support person within the school and that this introduced logistical difficulties dependent on the priority the school placed on therapy. 33 , 34

Relationships

Participants in 4 studies reported that telehealth negatively impacted their therapeutic relationship with the child, 9 , 31 , 33 , 36 while relationships and collaboration with parents and educators were reported to be improved in 7 studies. 9 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38

Allied health professionals perceived that they had an improved collaboration with teachers 37 and improved relationships and upskilling of parents 34 , 35 with parents when using telehealth. Another study reported perceptions that telehealth was more successful when it was supported by local providers and other stakeholders such as parents and teachers. 34 , 36

Minor themes

Other allied health professional themes were logistics, 33 local staff changes 38 and safety and efficacy of a feeding service 32 acting as barriers to using telehealth for service delivery.

3.6.2. Families

Access

Reduced access for families was reported by one study, with allied health professionals believing families did not have sufficient technology or finances to access a telehealth service; however, this was not supported by family perceptions. 41 Improved access for families was identified by allied health professionals in 7 studies, reporting reduced travel and time 13 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 and reducing gaps in regional services 35 , 38 as reasons.

Family‐centred care

Three studies reported beliefs by allied health professionals that family‐centred care would be negatively impacted by telehealth. 32 , 33 , 36 Participants believed children would not participate in telehealth appointments 36 and that family privacy would be compromised. 32 , 33 While 2 studies reported participant beliefs that telehealth would improve privacy for families, 9 , 36 7 studies reported belief of improvements to family‐centred care. 13 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40

Telehealth was generally seen to be more convenient and less disruptive to child and family schedules than attending a physical appointment. Reasons included facilitating academic learning as the appointment was easier to fit around the school day, 40 improved carer engagement 32 , 36 and was flexible for families. 35 It was also reported that children and parents were more relaxed in their own familiar environment. 31 , 32 , 35 Families felt they were supported to implement therapy strategies at home when therapy took place in the home context. 35 Importantly, it was perceived that families for whom attending physical appointments was inconvenient due to complexity of disability, responsibilities for other children or parent work could still access interventions. 32 , 35

Reporting bias was limited by using a review protocol and the PRISMA guidelines. 24 There is low certainty in the results as there is bias within each study, low quality of studies and high variation in populations and themes reported across each included study. This should be considered when reading recommendations and the conclusion.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Key findings

The objective of this review was to identify the attitudes of allied health professionals (speech pathologists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists) towards using telehealth for service delivery to children with developmental delays. The identified attitudes and perspectives can be summarised into 7 main themes. Clinician themes are technology, self‐efficacy, replacement of face‐face services, time management and relationships. Family themes are access and family‐centred care. These themes give an insight into the potential of telehealth to manage service gaps in rural areas past the necessities of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

4.2. Limitations

Limitations of this systematic review method were restricting to peer‐reviewed databases and English‐language articles. Grey searching was used to control this. There is a risk that not all relevant search terms were used; however, this risk was controlled by using a librarian to assist with the search strategy. Limitations identified in the included studies include 2 studies sharing data sets. 39 , 41 Population characteristics were not consistently reported throughout the studies; however, speech pathologists were included more frequently than occupational therapists and physiotherapists so findings cannot be generalised across disciplines. Patient group characteristics were inconsistently described; thus, conclusions on which patient populations are suitable for telehealth are unable to be drawn. Study design was a further limitation with only one study using a comparison group, 38 and this study was appraised to be of poor quality. 25 No study was greater than VI on the evidence hierarchy. 27

4.3. Implications for clinical practice

Potential solutions to be applied to clinical practice arise in the themes of technology, self‐efficacy, time management and access. In the theme of technology, studies reporting positive perceptions of technology were published in 2019. 36 , 38 The studies reporting technology as a barrier varied from 2008 to 2020 in year of publication. 13 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 While certainly no conclusions can be drawn from this, it is encouraging that recent studies have some positive perceptions of telehealth and report beliefs that technological issues can we worked through. 38 A potential solution in clinical practice is prioritising personal technological equipment upgrades (eg laptop with suitable processing) and readily available technology support to reduce technological difficulties. 11

Self‐efficacy associated with lack of training was frequently reported throughout the review. 13 , 31 , 36 , 39 , 40 , 41 Lack of self‐efficacy could be rectified by providing training and support prior to and during the implementation of telehealth programs. 43 Indeed, the participants in the review recognised this need themselves. 9 , 13 , 38 Allied health professionals in rural areas have been shown to be time poor 10 ; therefore, the initial time investment in telehealth training to reduce time cost in future should be impressed upon clinicians.

The theme of time management brought forward some surprising perceptions; given the significant time cost of travel for rural health appointments, 9 negative perceptions towards time management were unexpected. There were concerns around logistics of setting up a telehealth appointment and time wasted on managing technological difficulties. 33 , 34 Potential solutions are adequate training and technology, along with contingency plans for when unavoidable technological failures occur. In addition, improved relationships with stakeholder groups might help with time spent organising appointments around opposing schedules. 37 The onus should be placed on the organisation implementing telehealth to ensure policies and procedures are in place to support efficient use of telehealth. 11

While access has been considered a ‘family’ theme in this review, it also has some potential to increase buy‐in from allied health professionals. Reduced costs due to telehealth have been reported in other areas of health provision (in this case, oncology 44 ) due to avoidance of clinician travel costs. This research is yet to be emulated in the children's physiotherapy field. Organisational cost savings could redirect funding to allied health staffing in rural areas, thereby improving access to allied health services for families and reduced staffing pressures for organisations. 11 Should telehealth be shown to be cost‐effective, telehealth has the potential to improve access across rural settings. 11

4.4. Implications for future research

When considering telehealth as a replacement to face‐to‐face services, there was a lack of specificity in reporting around the population telehealth was used with. Edirippulige et al 9 did specify that speech pathologists felt telehealth should not replace face‐to‐face therapy for children with cerebral palsy, while occupational therapists believed it was similar to face‐to‐face therapy. Physiotherapists in this study believed telehealth was useful for pre‐ and post‐operation planning for children with cerebral palsy. 9 It is possible that therapies historically requiring less physical touch, for example post‐surgical follow‐up, 9 would be seen as more acceptable via telehealth than a high‐risk therapy like a swallowing assessment. 32 However, as reasons were not clearly identified it is only possible to speculate. In future, detailed data pertaining to the intervention and patient group might provide clarity.

When considering relationships, clinicians were unsure how to build relationships with children over the screen. 9 , 31 , 33 , 36 Further studies should explore building rapport with children via telehealth. In addition, training programs should include this to increase clinician confidence with building rapport via telehealth.

Access was largely seen as a positive with perceptions that there was reduced burden of travel and travel‐related costs for families. 13 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 Travel for health care by both providers and families is a major financial and environmental issue in rural Australia. 44 One study in rural Queensland reported mean travel times for each family for a child's outreach visit were 5 hours and 46 minutes for each visit to and from a central hub. 9 Perceptions of reduced travel might also increase buy‐in from allied health professionals. Reduced costs associated with reduced clinician travel have been reported in other areas of health provision (in this case, oncology 45 ). This research is yet to be emulated in the children's physiotherapy field. Organisational cost savings could redirect funding to allied health staffing in rural areas, thereby improving access to allied health services for families and reduced staffing pressures for organisations. 11 Should telehealth be shown to be cost‐effective, telehealth has the potential to improve access across rural settings as organisations see financial benefit in servicing those areas. 11

5. CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review investigated the perspectives of allied health professionals on using telehealth to deliver interventions to children with developmental delays. Synthesis of this literature identified that there are both facilitators and barriers to adoption of telehealth for allied health service delivery in children with developmental delay. Facilitators included improved access to services, family‐centred care and collaboration with stakeholders. Barriers identified were the belief that telehealth cannot replace face‐to‐face therapy, technology failure, lack of self‐efficacy, lack of time to implement telehealth service and interference with therapeutic relationships.

Evidence quality was limited by study design with only studies with low‐quality evidence identified and high risk of bias present within studies. The low‐quality evidence means that the results should be treated with caution. The generalisability of findings is limited due to sampling methods, small sample sizes and low response rates. Occupational therapists and physiotherapists were under‐represented in the populations included in this review.

This review highlights that many barriers are perceived, but solutions and workarounds to these barriers can also be identified. These findings need to be corroborated by higher quality studies. Further studies should consider the cost versus benefits of allied health telehealth services for children with developmental delays and represent the views of occupational therapists and physiotherapists.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CG: conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review & editing. AJ: conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; supervision; writing – review & editing. HL: methodology; writing – review & editing.

DISCLOSURE

No funding sources directly related to the paper. Claire Grant receives higher degree by research funding through the James Cook University.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Claire Grant works as a physiotherapist with children with developmental delay for a private company. She undertook the systematic review as part of a masters by research at the James Cook University. Anne Jones and Helen Land are both employees of the James Cook University. Open access publishing facilitated by James Cook University, as part of the Wiley ‐ James Cook University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Grant C, Jones A, Land H. What are the perspectives of speech pathologists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists on using telehealth videoconferencing for service delivery to children with developmental delays? A systematic review of the literature. Aust J Rural Health. 2022;30:321‐336. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12843

REFERENCES

- 1. Choo YY, Agarwal P, How CH, et al. Developmental delay: identification and management at primary care level. Singapore Med J. 2019;60(3):119‐123. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2019025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Australian Government Department of Health . About allied health [Internet]. Canberra (AU): Australian Government Department of Health; 2021 [updated 2021 Oct 13]. https://www.health.gov.au/health‐topics/allied‐health/about Accessed January 26, 2022.

- 3. McCoy SW, Palisano R, Avery L, et al. Physical, occupational, and speech therapy for children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;62(1):140‐146. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mazer B, Feldman D, Majnemer A, et al. Rehabilitation services for children: therapists' perceptions. Dev Neurorehabil. 2006;9(4):340‐350. doi: 10.1080/13638490600668087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Raspa M, Bailey DB, Olmsted MG, et al. Measuring family outcomes in early intervention: findings from a large‐scale assessment. Except Child. 2010;76(4):496‐510. doi: 10.1177/001440291007600407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arefadib N, Moore T. Reporting the Health and Development Of Children in Rural and Remote Australia. Centre for Community Child Health, Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne and the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute; 2017. https://www.royalfarwest.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2017/12/Murdoch‐Report.pdf Accessed November 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Rural & Remote Health. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2019. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural‐remote‐australians/rural‐remote‐health Accessed November 11, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 8. St Clair M, Murtagh DP, Kelly J, et al. Telehealth a game changer: closing the gap in remote Aboriginal communities. Med J Aust. 2019;210(6 Suppl):S36‐S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edirippulige S, Reyno J, Armfield NR, et al. Availability, spatial accessibility, utilisation and the role of telehealth for multi‐disciplinary paediatric cerebral palsy services in Queensland. J Telemed Telecare. 2016;22(7):391‐396. doi: 10.1177/1357633X15610720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adams R, Jones A, Lefmann S, Sheppard L. Decision making about rural physiotherapy service provision varies with sector, size and rurality. Service level decision‐making in rural physiotherapy: development of conceptual models. Physiother Res Int. 2015;21:116‐126. doi: 10.1002/pri.1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bradford NK, Caffery LJ, Smith AC. Telehealth services in rural and remote Australia: a systematic review of models of care and factors influencing success and sustainability. Rural Remote Health. 2016;16(4):245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sood S, Mbarika V, Jugoo S, et al. What is telemedicine? A collection of 104 peer‐reviewed perspectives and theoretical underpinnings. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13(5):573‐590. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hill AJ, Miller LE. A survey of the clinical use of telehealth in speech‐language pathology across Australia. J Clin Pract Speech‐Lang Pathol. 2012;14(3):110‐117. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ekberg S, Danby S, Theobald M, et al. Using physical objects with young children in ‘face‐to‐face’ and telehealth speech and language therapy. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(14):1664‐1675. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1448464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moffatt JJ, Eley DS. The reported benefits of telehealth for rural Australians. Aust Health Rev. 2010;34(3):276‐281. doi: 10.1071/ah09794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wakerman J, Humphreys JS. Sustainable primary health care services in rural and remote areas: innovation and evidence. Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19(3):118‐124. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2010.01180.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wootton R. Twenty years of telemedicine in chronic disease management – an evidence synthesis. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(4):211‐220. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.120219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Camden C, Pratte G, Fallon F, et al. Diversity of practices in telerehabilitation for children with disabilities and effective intervention characteristics: results from a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(24):3424‐3436. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1595750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wales D, Skinner L, Hayman M. The efficacy of telehealth‐delivered speech and language intervention for primary school‐age children: a systematic review. Int J Telerehabil. 2017;9(1):55‐70. doi: 10.5195/ijt.2017.6219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989;13(3):319‐340. doi: 10.2307/249008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kissi J, Dai B, Dogbe CSK, et al. Predictive factors of physicians’ satisfaction with telemedicine services acceptance. Health Inform J. 2020;26(3):1866‐1880. doi: 10.1177/1460458219892162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Camden C, Silva M. Pediatric telehealth: opportunities created by the COVID‐19 and suggestions to sustain its use to support families of children with disabilities. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2021;41(1):1‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Australian Government Department of Health . Fact Sheet: Coronavirus National Health Plan; 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/04/covid‐19‐national‐health‐plan‐primary‐care‐package‐mbs‐telehealth‐services‐and‐increased‐practice‐incentive‐payments‐covid‐19‐national‐health‐plan‐primary‐care‐package‐mbs‐telehealth‐services‐and‐increased‐practice‐incenti_2.pdf Accessed November 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [published Online First: 2021/03/31] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crowe M, Sheppard L. A general critical appraisal tool: an evaluation of construct validity. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(12):1505‐1516. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crowe M, Sheppard L, Campbell A. Reliability analysis for a proposed critical appraisal tool demonstrated value for diverse research designs. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(4):375‐383. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ackley BJ. Evidence‐based Nursing Care Guidelines: Medical‐surgical Interventions. Mosby Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy‐making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):6‐20. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308576 [published Online First: 2005/08/02] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. 2006 Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. ESRC Methods Programme; 2006. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster‐university/content‐assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1‐April2006.pdf Accessed November 6, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339(jul21 1):b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Iacono T, Dissanayake C, Trembath D, et al. Family and practitioner perspectives on telehealth for services to young children with autism. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;231:63‐73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raatz MK, Ward EC, Marshall J. Telepractice for the delivery of pediatric feeding services: a survey of practice investigating clinician perceptions and current service models in Australia. Dysphagia. 2020;35(2):378‐388. doi: 10.1007/s00455-019-10042-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rortvedt D, Jacobs K. Perspectives on the use of a telehealth service‐delivery model as a component of school‐based occupational therapy practice: designing a user‐experience. Work. 2019;62(1):125‐131. doi: 10.3233/WOR-182847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Akamoglu Y, Meadan H, Pearson JN, et al. Getting connected: speech and language pathologists’ perceptions of building rapport via telepractice. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2018;30(4):569‐585. doi: 10.1007/s10882-018-9603-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ashburner J, Vickerstaff S, Beetge J, et al. Remote versus face‐to‐face delivery of early intervention programs for children with autism spectrum disorders: perceptions of rural families and service providers. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;23:1‐14. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2015.11.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Campbell J, Theodoros D, Russell T, et al. Client, provider and community referrer perceptions of telehealth for the delivery of rural paediatric allied health services. Aust J Rural Health. 2019;27(5):419‐426. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hines M, Lincoln M, Ramsden R, et al. Speech pathologists’ perspectives on transitioning to telepractice: what factors promote acceptance? J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(8):469‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johnsson G, Kerslake R, Crook S. Delivering allied health services to regional and remote participants on the autism spectrum via video‐conferencing technology: lessons learned. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19(3):5358. doi: 10.22605/RRH5358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McAllister L, Dunkley C, Wilson L. Attitudes of speech pathologists towards ICTs for service delivery ACQuiring Knowledge Speech Lang Hear. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech‐Language Pathology (JCPSLP). 2008;10(3):84‐88. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tucker JK. Perspectives of speech‐language pathologists on the use of telepractice in schools: the qualitative view. Int J Telerehabil. 2012;4(2):47‐60. doi: 10.5195/ijt.2012.6102 [published Online First: 2012/10/01] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dunkley C, Pattie L, Wilson L, McAllister L. A comparison of rural speech‐language pathologists' and residents' access to and attitudes towards the use of technology for speech‐language pathology service delivery. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2010;12(4):333‐343. doi: 10.3109/17549500903456607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tucker JK. Perspectives of speech‐language pathologists on the use of telepractice in schools: quantitative survey results. Int J Telerehabil. 2012;4(2):61‐72. doi: 10.5195/ijt.2012.6100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ammentorp J, Sabroe S, Kofoed P‐E, et al. The effect of training in communication skills on medical doctors’ and nurses’ self‐efficacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(3):270‐277. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cheek C, Skinner T, Skinner I. Measuring the environmental cost of health‐related travel from rural and remote Australia. Med J Aust. 2014;200:260‐262. doi: 10.5694/mja13.00185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thaker DA, Monypenny R, Olver I, et al. Cost savings from a telemedicine model of care in northern Queensland, Australia. Med J Aust. 2013;199(6):414‐417. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]