Abstract

COVID-19 outbreaks at nursing homes during the recent pandemic have received ample media coverage and may have lasting negative impacts on individuals’ perception of nursing homes. We argue that this could have sizable and persistent implications for savings and long-term care policies. Our theoretical model predicts that higher nursing home aversion should induce higher savings and stronger support for policies subsidizing home care. Based on a survey of Canadians aged 50 to 69, we document that higher nursing home aversion is widespread: 72% of respondents are less inclined to enter a nursing home because of the pandemic. Consistent with our model, we find that these respondents are more likely to have higher intended savings for old age because of the pandemic. We also find that they are more likely to strongly support home care subsidies.

Keywords: Pandemic risk, Nursing home, Long-term care, Savings, Public policy

1. Introduction

In many countries including Canada and its provinces of Québec and Ontario, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has shed light on the precarious sanitary conditions of the elderly population and, in particular, of those residing in nursing homes. There has been extensive media coverage of the dramatic consequences of COVID in nursing homes, where infection rates and mortality have been particularly high. As we detail in Section 2, during the first wave (March to August 2020), more than 80% of the Canadian deaths due to COVID were reported in nursing and seniors’ homes (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2020). More generally, the pandemic has brought attention to the often poor management of nursing homes (even before the pandemic), their lack of staff and the negative consequences of a pandemic on the living conditions of the dependent elderly in these facilities.

As a consequence, the pandemic has increased awareness amongst many individuals regarding their long-term care (hereafter LTC) risk, and it may have permanently affected their preferences regarding LTC solutions in the future.1 The pandemic has thus led policy makers and individuals to think about alternative solutions to nursing home care. One solution is to receive LTC at home. The main concern for the home care option is its (out-of-pocket) costs. Home care is much more expensive than public nursing home care, in particular if dependents do not have family members that can provide informal care (see Section 2 where we compare the costs of nursing homes versus home care).

The pandemic has pushed society to reconsider the attractiveness of home care versus nursing home care. Because individuals anticipate today the financial resources they will need tomorrow in case they become dependent, they may wish to adapt their saving plans as well. In the same way, policy makers will need to develop LTC policies better suited to individuals’ preferences. Those public solutions are multifaceted: build new nursing homes, foster the training of LTC workers, but also make the home care option more affordable through, for instance, subsidies and tax exemptions.2

Developing adequate LTC policies regarding the type of care provision and financing solutions is crucial. Indeed, in every developed country, the population is aging, implying that the fraction of people with important care needs is growing. According to OECD (2011), the fraction of people aged 80 and above is expected to grow from of the total OECD population in 2010 to in 2050. Canada is not exempt from this trend. For instance, Clavet et al. (2021) estimate that the number of individuals needing help with activities of daily living (hereafter ADLs) in Québec is likely to almost double, from 315,000 in 2020 to more than 600,000 in 2050. If households plan to use a costlier option of LTC post-pandemic, they will need more savings to pay for it. But this form of self-insurance is costly and it may call for increased policy intervention.

The objective of this paper is to provide empirical evidence on the potential impact of the COVID pandemic on LTC preferences, and on how shifts in expected LTC choices impact saving behavior and LTC policy preferences. The paper also develops a theoretical model explaining the mechanisms behind the changes caused by the pandemic.

The COVID pandemic can have two long-term implications for care preferences. First, people may believe that other pandemics will occur in the future, and that a nursing home does not provide much protection against health risks during a pandemic. Second, individuals may view nursing home care more negatively even in the absence of a pandemic, as they were confronted with extensive (often negative) information about the quality of nursing home care. Our paper evaluates how preferences for home care or nursing home care may have been permanently affected by the pandemic. In particular, we study both theoretically and empirically how a stronger preference for home care post-pandemic may have changed savings decisions and the support for a public policy promoting home care.

We propose a model where individuals differ in their preference for home care, or, equivalently, in their degree of aversion to nursing home care. Based on empirical observations, we assume that home care is more expensive than nursing home care. We first develop the model in the absence of any pandemic risk that could affect nursing home aversion. Our model predicts that those who plan to use home care, a more costly option than nursing home care, will choose to save more. We then introduce a pandemic risk which worsens individuals’ view of nursing home care. As highlighted previously, this results from either a higher (perceived) probability of catching a pandemic-related disease in a nursing home, or from a higher degree of nursing home aversion following increased media coverage of nursing home quality in general. In our framework, the two turn out to be isomorphic. We show that following a pandemic, a higher proportion of households prefers the home care option and that, in order to finance this choice, they choose to save more. Further, we show that support for a tax-financed policy subsidizing home care is likely to increase post-pandemic. We also show that the increase in support exists across the board and is not limited to those who were already in favor pre-pandemic.

We test these theoretical predictions from our model using data from a survey on LTC-related preferences of the elderly. In the fall of 2020, we partnered with Asking Canadians, a Canadian online panel survey organization, to field a survey to 3004 Ontarian and Québec respondents. The survey targeted respondents between 50 and 69 years old, with the intention of learning about people’s predicted LTC choices in a post-pandemic era, instead of choices during the pandemic. The survey elicited how LTC preferences, saving behaviour and preferences for public policies were affected by the COVID pandemic.

The empirical evidence is in line with the predictions of the theoretical model. We find a widespread increase in nursing home aversion post-pandemic: 72% of the sample report to be less inclined to enter a nursing home because of the pandemic. Also, about 70% of the sample report that their view on the exposure to health risks in nursing homes worsened during the pandemic. At the same time, many respondents are aware that the home care option is costlier, and hence that they would have to save more to finance that option. Consistent with our theoretical model, about a quarter of the sample report that they indeed plan to save more for old age because of COVID, and the vast majority of them say they plan to save more to avoid entering a nursing home. Specifically, we find that increased nursing home aversion is associated with a higher probability of increasing future savings of 8.5 to 14.0 percentage points. This is sizable and corresponds to 31.6% to 52.0% of the unconditional (weighted) mean probability of 26.9%. We further confirm that this positive association between increased planned savings and increased nursing home aversion is robust to controlling for many potential confounding factors. Overall, our results suggest that the pandemic may have a significant lasting effect on individuals’ intended savings for old age because of increased nursing home aversion and thus an increased willingness to utilize costlier home care.

Lastly, we document a strong support for a policy that would subsidize home care, with 70% of our sample either “very much agreeing” or “agreeing” with it. This suggests that such a policy could have broad electoral support. Furthermore, consistent with the predictions of our model, we find strong evidence that the increased support for such a policy post-pandemic is mostly driven by increased nursing home aversion. Quantitatively, we find that increased nursing home aversion is associated with a higher probability to “very much agree” with such a policy of 7.3 to 11.8 percentage points. This corresponds to 36.1% to 58.4% of the unconditional (weighted) mean probability which is 20.2%.

Our paper is related to several strands of the literature, the first of which being the growing literature on the design of appropriate LTC insurance (LTCI) policies. So far, this literature has mostly concentrated on the reasons behind the “LTCI puzzle” (namely, the lack of private LTCI worldwide) and on how governments could incentivize LTCI purchase.3 There is also an expanding literature on the value of (partial) public insurance (De Nardi et al. (2016); Braun et al. (2017); Achou (forthcoming), to name a few). Most of these studies do not consider individuals’ choices between nursing home care and home care (one exception is (Koreshkova and Lee, 2020), who study these choices using a structural model). We contribute to this literature by first proposing a theoretical model on how a pandemic can affect the relative preferences for home care and nursing home care, and second, by showing whether our theoretical predictions are supported by empirical evidence. Our results shed light on how to redesign public LTC policies post-pandemic. Our paper also relates to the literature on old-age savings as a form of self-insurance for late-in-life risks (e.g. Palumbo (1999); Kopczuk and Lupton (2007); De Nardi et al. (2010); Ameriks et al. (2011); Kopecky and Koreshkova (2014); Lockwood (2018); Ameriks et al. (2020)). We contribute to this literature by showing that nursing home aversion due to the pandemic can increase individuals’ willingness to save for old age.

Finally, our paper contributes to the recent and prolific literature on the effect of a pandemic, and specifically of the COVID-19 pandemic, on different economic outcomes. This literature studies both micro (for instance, the costs and benefits of specific confinement measures) and macro outcomes (for instance, the effects of the pandemic on trade, labour markets and the economic activity in general).4 Directly related to our paper, Hurwitz et al. (2021) seek to understand the potential long-run implications of the pandemic on savings for retirement. Yet, although the pandemic has hit primarily the (dependent) elderly and especially those in nursing homes, we are unaware of any specific analysis of the changes in preferences for home care and nursing home care, and of their impacts on savings and political support for home care post-pandemic. One exception is the survey conducted by the National Institute on Ageing (2021) that asks questions similar to ours regarding the preferences of Canadians toward nursing home care and state intervention, as well as about their beliefs about health risk exposure and how they have changed due to pandemic. They find that 96% of the survey respondents, aged 65 years and older, report that, as they get older, they will do everything they can to avoid moving into a nursing home. Furthermore, 86% considered that LTC should be part of an integrated health system. In contrast to that paper, our study provides a theoretical model that allows us to form well-defined predictions on the impact of the pandemic on intended savings as well as on the support for a specific LTC policy (home care subsidy). Our empirical analysis demonstrates that nursing home aversion post-pandemic is indeed the main driving force behind the increase in intended savings and supports for such a policy.

Our paper is structured as follows. In the following section, we present the institutional background regarding the provision of LTC in Canada and how COVID affected this sector. In Section 3, we develop a theoretical model to form predictions of individual care choices, savings, and preference for government intervention, both in the absence of a pandemic risk and then allowing for it. In Section 4, we describe our data sample. In Section 5, we provide empirical results obtained from our survey data regarding nursing home aversion, changes in intended savings, and support for a public policy promoting home care following the COVID-19 pandemic. The last section concludes.

2. The institutional background

In this paper, we study individuals’ choices for home care versus nursing home care in case of dependency. In our survey we asked a panel of 3004 respondents from Ontario and Québec about their preferences for these two care options, taking into account the different features of home care and nursing home care. In this section, we provide an overview of the characteristics of each care option in Québec and in Ontario.

We start by explaining the differences in prices paid by the elderly. If a dependent elderly enters a nursing home (private or public), the latter provides services such as personal services (e.g. toileting and dressing), meal preparation, and nursing/medical services. In addition, it also provides basic (hygienic) goods and services so that, apart from the price paid for the nursing home, the elderly has to bear very few extra expenses.

The rates for a place in a nursing home vary across provinces. In Ontario, the maximum rates for an accommodation in a public nursing home are legally set by the Ministry of Long-Term Care. In 2019, they ranged from 1891 CAD for a basic accommodation to 2280 CAD for a semi-private room and 2701 CAD for a private one. These costs can be partly covered by a subsidy whose maximum is 1891 CAD per month and which is conditional on an individual’s financial situation. In particular, to be eligible for this subsidy, the elderly needs to be already receiving all provincial and federal benefits, such as the Old Age Security (OAS), the Ontario Disability support program and the Guaranteed Income Security (GIS). The subsidy will depend on the elderly’s net income.5 In Québec, the setup is similar to that in Ontario. The prices of public nursing home care (also called Centre d’Hébergement et de Soins de Longue Durée, or CHSLD) depend on the type of accommodation, and range from 1223 CAD for a basic accommodation to 1642 CAD for a semi-private room and 1966 CAD for a private room. These costs can be partially covered by a subsidy, whose value depends on the individual’s financial situation. For the poorest, the subsidy covers the full cost of a public nursing home with a basic accommodation, so they are exempt from any out-of-pocket cost in using this type of nursing home.6

One crucial issue with public nursing homes both in Ontario and in Québec is the significant delay between the time an individual is declared as needing help with ADLs and the time he/she enters a public nursing home. Data on waiting times are relatively scarce. In Québec, the mean waiting time was around 10 months in 2017, with a lot of variation across regions (Commission à la Santé et au Bien-être, 2017). In Ontario, the median waiting time was evaluated to be around 108 days in 2013–2014 (Wait Time Alliance, 2015). As mentioned in a report of the Commission de la Santé et des Services Sociaux (2016) for Québec, these waiting times can have the undesirable consequence of pushing the elderly to enter a nursing home far away from their family and relatives.

For these reasons, the elderly dependent may instead choose to enter a private nursing home (not under agreement), for which there are usually no waiting times.7 In Québec, the cost for a place in such a nursing home range from 5000 CAD to 8000 CAD a month (Girard, 2020).

Another alternative for the elderly facing issues with ADLs is to stay at home and to resort to home care. At-home services can take various forms such as meal preparation, personal services (e.g. toileting and dressing) and nursing services. Depending on the type of service required, the price of one hour of skilled nursing care varies between 15 CAD and 85 CAD in Québec, and between 23 CAD and 70 CAD in Ontario.8 Even if these services give rights to tax credits, home care can quickly become disproportionately expensive compared to a nursing home.9 Take for example the situation of a dependent elderly who requires (only) 4 hours of care 7 days a week. The monthly cost of home care would amount to around 4300 CAD if the cost of one hour of care is (only) 35 CAD. This does not even take into account that, in addition to the costs of home care services, an elderly staying at home will have to bear extra expenses for food, hygienic products, laundry services and other expenses that are included in the rate of a nursing home. The individual will also have to bear additional expenses related to lodging such as house maintenance, mortgage payments, rent or electricity bills, which, by definition, are included in the nursing home rate. Importantly, while some policy programs help finance home care costs, they turn out to often cover only a small share of these costs. For instance, Tousignant et al. (2007) estimate that only 8% of home care needs are covered by the public system in Québec. As a result, individuals relying on home care face huge out-of-pocket costs compared to those choosing the nursing home option. Therefore, they need to rely even more on dissaving, selling their home or using a reverse mortgage to finance LTC expenses.10 These ways of paying for home care are particularly important since in Canada, like in many other OECD countries, private LTC insurance is almost nonexistent (see OECD (2011) and Boyer et al. (2020)).

Nonetheless, the pandemic may have made the home care option more attractive as nursing homes experienced a large number of outbreaks and deaths both in Québec and Ontario, especially during the first wave. At the end of this first wave (May 2020) more than 90% of the COVID deaths in Québec had occurred among individuals aged 70 and more, and around 70% of those deaths had occurred in nursing homes.11 Similarly, in Ontario, more than 70% of the COVID deaths by the end of May 2020 had occurred in nursing homes.12

Many press releases reported that in these nursing homes, some of the caretakers left their jobs because they themselves had COVID, because of bad and unsafe working conditions, or because of work overload.13 As a consequence, residents faced an increased health risk as they were left in bad living conditions (not bathed, not fed enough, and not medicated). For instance, in its report, the Protecteur du Citoyen (the ombudsman for Québec) mentions that 46% of the residents and 60% of their relatives reported that the quality of care decreased or was insufficient during the first wave, in particular for basic and hygienic care.14 At some nursing homes, appropriate health and satefy measures required for COVID patients have not been taken, which led to many COVID deaths.15

In our paper, we do not consider the choice between public and private nursing homes for two reasons. First, prior to the pandemic, several professionals from the LTC sector that we consulted told us that there is no clear evidence that private nursing homes offer a better quality of care than public ones. Instead, as mentioned above, the main difference they highlighted was related to waiting times and location choice. Second, both in Québec and Ontario, the pandemic strongly affected both private and public nursing homes, and poor quality of care was not specific to public nursing homes.16 As a consequence, we do not expect the pandemic to increase the attractiveness of private nursing homes relative to public ones, which is indeed confirmed by responses to our survey (see Section 5). Instead, given that both public and private nursing homes experienced a large number of COVID outbreaks in the first wave, and that the press reported instances of substandard quality in both types of institutions, we focus on the choice between home and nursing home care.

3. The model

We model a two-period setting. In the first period, all agents have the same endowment, and choose how much to save for the second period, in which saving is their only source of income. All agents face two risks at the beginning of the second period: (i) dependency and (ii) catching a disease associated with a possible future pandemic, which can be seen as being similar to COVID in 2020. Agents are homogeneous in both the probability of dependency and of catching the disease. The only decision to be taken in the second period is for dependent agents to choose whether they prefer home care (HC hereafter in this section) or moving to a nursing home (NH hereafter in this section), which we call the care type decision.17

For pedagogical reasons, we first develop the model in the absence of a pandemic risk in Section 3.1. This allows us to isolate the determinants of the choice between HC and NH in the absence of a pandemic risk. We then introduce pandemic risk in the model in Section 3.2 in order to analyze its effect on both the savings and the care type decision of the elderly. Finally, in Section 3.3, we introduce a social insurance program that subsidizes HC. We study how individuals’ perception of the risk from the disease depends on the care type (possibly reflecting the relatively higher pandemic risk in NH shown in Section 2), and how this affects the care type preferences, savings decisions as well as individuals’ preference for public insurance covering HC.

3.1. The model with no pandemic risk

Agents all have the same endowment in the first period. In the first period, they choose how much to save, denoted by , and in the second period, whether to use HC () or NH care () if they become dependent. To simplify (and without loss of generality for our results), we assume away any discounting between the two periods, as well as any real return on saving. Agents all face the same probability of becoming dependent at the beginning of the second period.

At the beginning of the first period, agents’ expected utility is given by

| (1) |

where denotes the first-period utility function, the second-period utility function in case of good health, and with the utility function of dependent agents as a function of their care type choice. All utility functions are increasing and (weakly) concave in consumption . The function also satisfies the Inada condition that .

We assume that the type of care affects an individual’s preferences in two directions. First, each type of care is associated with an out-of-pocket cost for the dependent agent, denoted by . Note that any existing public LTCI (such as subsidies or tax credits) covering a part of LTC expenses is already embedded here, since we consider out-of-pocket expenses. As documented in Section 2, with a limited public subsidy for home care, Canadians with any level of income and wealth face a significantly higher out-of-pocket cost for HC than for NH. To capture this fact, we assume that the out-of-pocket cost of HC is higher than the out-of-pocket cost of NH, that is .18 We also assume that .19

Second, agents differ in their intrinsic preference for HC versus NH care. We model this by using an additive term to the utility obtained with HC, so that the utility functions are such that

where the function is increasing and concave in its argument. Agents are aware of their type, defined by their value of . The econometrician does not observe each individual’s , but knows that is distributed according to distribution function and cumulative distribution .

Together, these assumptions imply the following ranking of marginal utilities:20

Agents have to choose (in the first period) and (at the beginning of the second period) to maximize their expected utility. We solve this problem in two steps. First, agents decide how much to save conditional on each care type. Second, they compare their utility levels in HC and NH, and choose the highest among the two options.

Their preferred level of maximizes the expected utility under each care option :

Defining first-period consumption as , the first-order condition (hereafter, FOC) with respect to is:

| (2) |

which depends on the type of care chosen, . Under the Inada condition (), we always have .

It is straightforward to see that a higher increases the marginal benefit from saving, so that when .

Let us now find how agents make their choice between NH and HC. They will choose HC over NH if:

where is defined by (2).

Denote Note first that since (even if agents can adapt their saving level, it is easy to see that utility decreases with ). Moreover, since increases with , we denote by the type of the agent indifferent between HC and NH. It satisfies or, equivalently,

Hence, all agents with (resp., ) prefer NH to HC (resp., HC to NH). We then obtain that:21

Hence, an increase in (resp., ) makes smaller (resp., larger) so that fewer (resp., more) individuals choose to enter a nursing home.

Observe also that:

because additional income increases the utility with HC more than that with NH (since implies a smaller first-period consumption level in HC). An exogenous increase in income then weakly increases the number of agents choosing HC over NH, everything else constant.22

The results of this section are summarized below:

Proposition 1

In the absence of a pandemic risk, individuals save more if they want to use HC rather than NH in case they become dependent.

An increase in the cost of nursing home care,, (resp., home care,) increases (resp., decreases) the number of individuals resorting to home care.

3.2. Introducing a pandemic risk

We now introduce a pandemic risk, and see how it impacts individual choices. This pandemic can be seen as being similar to the COVID-19 pandemic in its disproportionate impact on individuals in NH, as was observed in Canada (see Section 2).

In our model, this pandemic risk is associated with a utility cost for the person who catches the disease. This assumption seems more intuitive than a monetary cost, since Canada (as most advanced countries) has a social health insurance system that covers most if not all pandemic-related health expenditures. Therefore, the out-of-pocket cost of the pandemic disease is usually low. Agents rather fear the risk of complications and of dying, which is better represented as a (non-insurable) utility cost.

Agents all face the same probability of catching the disease whether they are healthy or in HC.23 We open up the possibility that this probability is larger in NH, and equal to with . Note that what we care about is the individuals’ perceived probability of risk exposure in a NH, as this is what will drive their preference for care type (and for saving). As explained in Section 2, the press has largely disseminated the idea that NH were not a safe environment, at least during the first COVID wave, and that the elderly in these facilities were particularly at risk of infection. In fact, evidence showed that infection rates in NH were much higher than in the rest of the population. For that reason, we assume that agents perceive the risk of catching the disease as being higher in NH than at home, and we set . We assume that the probabilities and are independent from each other.

Agents’ ex ante expected utility is then given by:

where and . The FOC with respect to with care type is

| (3) |

This is the same FOC as without a pandemic risk, and we thus have that since . This means that, for a given choice of care, neither nor has an impact on saving levels.

Agents choose HC over NH if:

where is defined by (3). We then obtain that the threshold type, , is given by so that

| (4) |

and with all agents (resp., ) preferring NH to HC (resp., the opposite). Note that an increase in the pandemic risk, through either higher or , is isomorphic to an increase in .

Like in the previous section, we find that an increase in (resp., in ) decreases (resp., increases) . An increase in endowment weakly increases the number of individuals choosing HC. In addition,

Thus, increasing either the health cost of the disease or the relative exposure to a pandemic in NH compared to HC () makes NH less desirable so that decreases. Note that decreases with as well, since the impact of a higher is larger in NH than in HC.

Proposition 2

When there exists a pandemic risk, an increase in (i) the baseline probability of catching the disease,, (ii) the perceived additional risk exposure to the pandemic in NH,, and (iii) the utility cost associated with the disease,, all decrease the number of agents willing to use the NH option, and increase the savings of those who switch from NH to HC fromto.

Before going further let us note an interesting feature of our model, resulting from the isomorphism between a positive shock to and an increase in the expected cost of the disease associated with NH, . There are two different ways in which the current pandemic might impact the choice of care in the future. First, for a given distribution of , a higher perceived risk of catching the disease during a potential future pandemic pushes individuals to switch from NH to HC. Second, as people are exposed more to (negative) information about NH during the current pandemic, it may permanently impact their preference for NH even if they do not fear another pandemic in the future. In that sense, NH aversion (or the increased preference for HC) can be modeled either by an increase in the perceived expected cost of the disease (through higher , or ), or by a shock on the preference parameter for HC, . All have the same implications for savings and also for support for a policy subsidizing HC (see below).

3.3. Introducing a public subsidy for HC

Let us assume now that the government considers introducing a policy which would provide a benefit to dependent agents choosing HC. It is financed by a lump-sum tax on all individuals in the first period. We assume throughout that so that the transfer partially compensates the extra cost of HC.

The reason why we consider a public policy directly targeted toward HC is that the public system currently only covers a very small share of home care needs. As a result, to cover their care needs, individuals would face a much higher out-of-pocket cost for HC (even after tax credits) than for NH (see Section 2). The recent COVID pandemic has amplified the need for finding solutions that would make HC more affordable.

In case HC is chosen, the individual maximizes the following expected utility function,

Using backward induction, we solve for the optimal saving level first, and then study individuals’ preference over the public policy.

For the sake of simplicity, we make the following assumption:

Assumption 1

The level of savings satisfies:24

| (5) |

For those who plan on using HC, under Assumption 1, the amount of saving is not affected by the tax but decreases with the subsidy . We then denote it by

For agents choosing NH, the problem is now to maximize:

| (6) |

Under Assumption 1, the level of savings satisfies

| (7) |

which is affected neither by nor by .

Agents choose HC over NH if:

where is defined by (5) and (7). We then obtain that the threshold for the indifference between HC and NH is given by so that

| (8) |

where the second line is obtained by making use of Assumption 1. We see that this utility differential does not depend on , which has to be paid irrespective of the chosen type of care. Equality (8) then defines the threshold as a function of the policy instruments, and with all agents with (resp., ) preferring NH to HC (resp., HC to NH), given . We then have, using the envelope theorem for ,

| (9) |

Intuitively, when increases, more people wish to use HC as its net cost is decreased, and decreases. The intensity of that relationship depends on the probability of becoming dependent ().

Finally note that, as before, any increase in the expected extra cost of the pandemic in NH, i.e. in , decreases , and thus increases the number of people who would prefer to avoid NH.

3.4. Individual preferences for the public policy

In this section, we assume that agents are proposed an exogenous policy subsidizing HC, and analyze (i) who favors the introduction of this policy, and (ii) how this preference is affected by (changes in) the perceived pandemic risk.

3.4.1. Political support for the HC policy

It is obvious that an agent who prefers (, ) to (0,0) chooses HC rather than NH with (, ) (otherwise, in NH he/she would pay a tax and receive no transfer, and would be better off without the policy).

Let us assume for the moment that, in the absence of the policy (, ), the best option of an agent with would be to choose NH. This means that, for this agent, , where the latter is defined as in Eq. (8) with .

Such an agent would then be in favor of the introduction of the policy (, ) if

so that the agent is indifferent between the two if satisfies

| (10) |

where and are defined by Equations (5) and (7) respectively. All individuals with prefer NH with , while all with prefer HC with (, . This threshold decreases in the extra cost of the pandemic in NH, i.e. in .

Note the difference between and . The threshold determines who prefers HC to NH in the presence of a policy defined by (, ). It is the choice made in the last stage of the game, when (, ) has already been imposed. The threshold rather determines who is in favor of the policy (, ), in case this individual prefers NH to HC without subsidy. This explains why is a function of while is not.

It remains to be checked that This condition is equivalent to

| (11) |

which is true if is small enough or is large enough.25 The condition is intuitive. An agent with a value of low enough to prefer NH over HC in the absence of a social program (i.e. with below ) requires the program to be generous enough (small tax and/or large transfer) to favor this policy (and move to HC to benefit from it).

To summarize the analysis so far, the support for an exogenous (, ) among those with is given by if condition (11) is satisfied, and zero otherwise.

Assuming that the condition is satisfied, the derivative of the political support for (, ) with respect to the utility cost of the disease, (among those who prefer NH in the absence of policy) is given by:

so that it is not clear whether an increase in increases or decreases the support for the policy among those who initially preferred the NH option. Note that the first term on the right-hand side, , is the marginal density of those who switch from NH to HC when facing a higher pandemic risk, even in the absence of the subsidy. The second term, , is the marginal density of those who are in favor of the policy but who would have still chosen NH in the absence of the subsidy. So, assuming for instance a uniform distribution, this expression becomes null so that the support for (, ) among the agents who prefer NH in the absence of a subsidy is independent of (equivalently, also independent of or ).

Note that if condition (11) is not satisfied, it means that the program is not generous enough to attract the favor of those who prefer NH in the absence of the program.

We now turn to those individuals with Such agents would be in favor of the introduction of the policy (, ) if:

| (12) |

which corresponds exactly to condition (11).

If this condition is satisfied, then all agents with are in favor of (, ). Once more, the policy has to be generous enough to attract some support. But in this case, the specific value of the individual preference for HC, , plays no role (provided of course that ) since those agents compare two situations (with and without the program) in which they prefer HC to NH anyway.

If condition (12) (or equivalently, condition (11)) is satisfied, then the support for (, ) among those agents who initially preferred HC, is given by and its derivative with respect to is given by:

More agents then prefer HC with a public policy as (or or ) increases.

If condition (12) is not satisfied, then the policy has no support, neither among those with nor among those with .

We then have two possible cases, depending on whether the condition in Eq. (11) is satisfied or not. In the following proposition, we sum up the above findings and show how the support within the entire population changes when the expected cost of the pandemic increases.

Proposition 3

(i) Ifis small enough compared tothat the condition in Eq. (11) is satisfied, then the fraction of agents in favor of (,) is given by:

and increases with C (as well as withand) since:

(ii) Ifis large enough compared tothat the condition in Eq. (11) is not satisfied, then no one is in favor of (,).

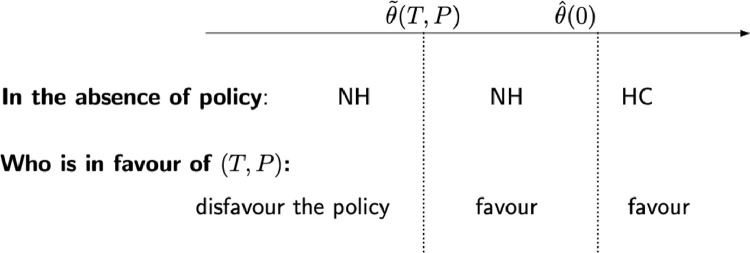

Fig. 1 below illustrates the partition of society between those who prefer NH over HC in the absence of the policy as well as the partition of society between those who favor the policy and those who do not.

Fig. 1.

Partition of the population when the condition in Equation (11) is satisfied.

Proposition 3 informs us about how the support for (, ) (i.e., the set of people in favor of the policy) varies with the risk of a pandemic. We show that and decrease with , translating into a larger set of agents favoring the policy .

In this first step of the analysis, we stepped aside from the intensity of the preferences for the policy and focused on how a pandemic risk would affect who will support the policy. In the next subsection, we study the intensity of individuals’ preference for the policy.

3.4.2. Preference intensity

We now analyze how for a given care preference, a pandemic risk affects the intensity of preferences for policy subsidizing home care.

We define the intensity of the preference for policy of an agent with type , denoted by , as the difference between the utility levels attained with and without the policy. In each case (i.e., with and without the policy), the agent chooses her optimal care type. We know from above that agents with choose NH while the others choose HC under the proposed transfer . We also know that decreases with , so that . We then face three types of agents: (i) those with choose NH whether the policy is enacted or not, (ii) those with choose HC with or without the policy, and (iii) those with prefer NH in the absence of the transfer, but switch to HC when the policy is enacted.

Agents with remain in NH with and without the policy, so that their utility differential is given by:

These agents dislike the program (since ) because they pay a tax to cover the cost of the program without enjoying its benefit.26

Agents with remain in HC with and without the policy, so that their utility differential is given by:

| (13) |

whose sign is positive under condition (11).

Finally, the care choice of agents with depends on the policy. For these agents, the utility differential is given by:

and is negative if and positive otherwise. Both groups will choose NH in the absence of the policy and HC under the policy. But the utility gain from switching to HC is linearly increasing in , leaving only those with high enough , i.e. , in favor of the policy.

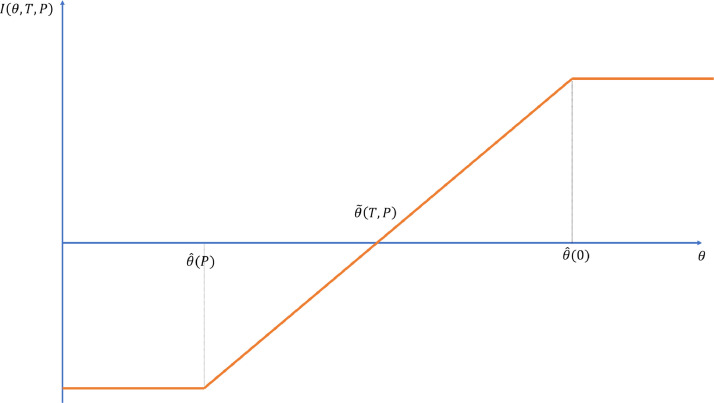

Figure 2 depicts the intensity of the preference for the public policy, , as a function of the agent’s type .

Fig. 2.

Long-term care preferences, and support for home care subsidy.

We now study how this intensity is affected by an increase in NH aversion. This higher NH aversion can take the form of either an increase in , or , or equivalently of an increase in . It will prove easier to discuss the second possibility. We then assume that the pandemic risk results in an increase in the value of of each agent by the same amount .

Agents with initial remain in NH with and without the policy, even after the pandemic shock. The intensity of their preference against the policy is unaffected by the pandemic, i.e. . In terms of Fig. 2, they remain on the flat part of the curve on the left despite the increase in NH aversion . Likewise, agents with initial remain in HC with and without the policy, before and after the pandemic shock. The intensity of their preferences in favor of the policy is then also unaffected by the shock, and defined as in Equation (13). They remain on the flat portion of the curve on the right in Fig. 2.

All other agents see the intensity of their preference for the policy increase following the pandemic shock. In terms of Fig. 2, the increase in moves them to a higher portion of the curve. We can identify three subgroups among those types: (i) agents with prefer NH without the policy and HC with the policy, before and after the shock, (ii) agents with prefer NH without the policy but move to HC with the policy only once the shock occurs, (iii) agents with prefer HC even without the policy after the shock.

We will refer back to this theoretical analysis when analyzing survey responses concerning a tax-financed subsidy for home care, in Section 5.3.2.

4. Data

The empirical analysis in Section 5 uses data from a survey we conducted between December 18th and December 31st 2020 in partnership with Asking Canadians, an online panel survey organization. The survey was fielded to residents of the Canadian provinces of Québec and Ontario aged 50–69 years. The survey screens out those respondents who have at least one ADL limitation at the time of the survey because the focus of the study is on the impact of the pandemic on the future plans for LTC instead of the current usage. We constructed survey weights by age, gender, and education using the 2016 Canadian Census to correct for under- and oversampling of certain subgroups, and make it representative of the Ontarian and Québec population. For questions for which we expected a significant proportion of missing information, such as income, we use unfolding brackets. We then use multiple imputation to assign missing values with information from the bracketing, conditional on basic socio-demographic covariates (age, gender and education).

Respondents could choose to answer the survey questionnaire in English or French. Upon completion of the survey, respondents received a loyalty reward from their choice of retailer (respondents could choose from a list of major retailers such as Walmart, Petro-Canada, and Hudson’s Bay). In total, 3004 respondents completed the survey.

The questionnaire consists of six main parts: questions about (i) demographics (including age, gender, education, marital status, number of children, health condition), (ii) financial situation (employed or retired, income level, savings amounts and composition, mortgage and property value), (iii) risk perceptions (regarding mortality and needing help with activities of daily living) and (iv) preferences (regarding risk aversion, preference for care from children and, preferences for leaving bequests), (v) a set of strategic survey questions (not used for this paper) and (vi) a set of COVID-related questions. The entire questionnaire except for part (v) can be found in the Appendix A (see supplementary material for the Appendix).

Table 1 summarizes the main socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of our weighted sample. We compare characteristics of our sample with those of respondents aged 50 to 69 in the 2016 Census and the January 2021 Labour Force Survey. Consistent with the construction of our weights, our survey delivers statistics for age, education and gender similar to those in the Census. In terms of marital status, our sample delivers figures broadly in line with those in the Census although it was not used in the construction of the survey weights. In particular, about two-thirds of our respondents have a spouse or partner. A little more than half of our sample is employed and about a third is retired. These figures align well with figures from the Labour Force Survey for the same age range although the work status categories do not map perfectly (see table notes). About two-thirds of our respondents have at least one child, and a vast majority of them have at least one child living less than 20 km away. Mean individual income is about 64,000 CAD. By comparison, according to Statistic Canada, mean income in Ontario in 2019 was 69,000 CAD for those aged 45 to 54, and 57,000 CAD for those aged 55 to 65. For Québec, the figures are 65,400 CAD and 48,600 CAD.27 Finally, given that our respondents are relatively old and have had time to accumulate wealth, average household (net) wealth (or net worth) in our sample is quite large at about 765,000 CAD.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Our survey | Census / LFS | |

|---|---|---|

| Québec province (%) | 39.0 | 38.8 |

| Age (%) | ||

| 50–54 | 28.5 | 28.5 |

| 55–59 | 27.6 | 27.6 |

| 60–64 | 23.4 | 23.4 |

| 65–69 | 20.5 | 20.5 |

| Female (%) | 51.4 | 51.4 |

| Marital status (%) | ||

| Married | 51.8 | 59.0 |

| Common-law | 13.6 | 12.0 |

| Widowed, separated, divorced | 18.2 | 18.3 |

| Never married | 16.4 | 10.7 |

| Education (%) | ||

| High school or less | 43.2 | 43.2 |

| College | 35.3 | 35.3 |

| University | 21.5 | 21.5 |

| Has a child (%) | 66.8 | - |

| Has a child 20km (%) | 51.0 | - |

| Work status (%) | ||

| Employed | 55.0 | 54.4 |

| Retired | 35.3 | 41.1 |

| Not working / Looking for work | 9.6 | 5.2 |

| Individual income (average, CAD) | 64,028 | - |

| Household wealth (average, CAD) | 765,205 | - |

Notes: The table compares the weighted statistics from our survey to statistics for similar variables in the 2016 Census and in the January 2021 Labour Force Survey (the latter is only used for work status). There is not a perfect mapping between our work status categories and those in the LFS. In the LFS, we classify those “employed at work” or “employed, absent from work” as “employed,” those “absent from work / unemployed” as “not working / looking for work” and the rest (those “not in the labour force”) as “retired.”

5. Empirical results

Recall that in Section 3, we examine the theoretical implications of nursing home aversion post-pandemic on late-in-life precautionary savings and on the support for a policy subsidizing home care. As shown in Proposition 2, nursing home aversion increases due to a pandemic if the perceived relative exposure to a pandemic in a nursing home compared to home care () increases, if the overall perceived risk of a pandemic ( and ) increases (given ), or if individuals update negatively their preferences for nursing home care versus home care (equivalent to an upward shift in the distribution of ) following new (negative) information about nursing homes (e.g. about the general quality of the care provided). Also as shown in Proposition 2, a higher nursing home aversion should increase the likelihood to save more (as the cost of home care is higher). In addition, as the model predicts that those who plan to use home care would favor a policy which subsidizes it, we expect the additional support for such a policy post-pandemic to stem mainly from those whose nursing home aversion increases, and who would now prefer to use HC.28

In this section, we provide survey-based empirical evidence for these theoretical predictions. Recall that our sample is aged between 50 and 69 years, so that the questions are not about their immediate use of LTC during the current pandemic but about what they expect to do post-pandemic, as they age.29

5.1. General patterns

Table 2 summarizes the responses to the key questions related to these predictions (see Appendix A for the questionnaire). First, nursing home aversion post-pandemic is widespread among older Canadians (Panel A). More than 70% of the respondents reported being less inclined to enter a nursing home than before the pandemic. This is not surprising given the media coverage of the COVID-19 outbreaks in nursing homes. To help understand reasons for this increased nursing home aversion, we further ask how respondents’ perceived exposure to health risks in nursing homes had been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (Panel B). Again not surprisingly, the current pandemic made many respondents believe that being in a nursing home will make them more vulnerable to health risks, with almost no difference between private and public nursing homes in that regard. Relating these findings to our theoretical model (see Proposition 2), this is equivalent to considering an increase in the parameter , if we believe that the health risk respondents had in mind was a higher exposure to a pandemic. However, it could also be interpreted as a general upward shift in the distribution if we believe that these responses reflect more a permanent loss of confidence in nursing homes being able to offer some protection against general health risks such as those arising from a pandemic.

Table 2.

Intended nursing home use, savings, and preferences for home care subsidies post-pandemic.

| A. Intended nursing home use | ||||||

| More inclined to enter a nursing home | 2.1% | |||||

| No change | 26.1% | |||||

| Less inclined to enter a nursing home | 71.7% | |||||

| N | 2,516 | |||||

| B. View on the exposure to health risks at nursing homes | ||||||

| 1) Public nursing homes | 2) Private nursing homes | |||||

| Improved | 12.9% | Improved | 11.7% | |||

| No change | 18.3% | No change | 17.8% | |||

| Worsened | 68.9% | Worsened | 70.5% | |||

| N | 2795 | N | 2,803 | |||

| C. Saving for older ages | ||||||

| 1) Changes in willingness to save | 2) Save more to avoid a nursing home?* | |||||

| Save more | 26.9% | Yes | 82.7% | |||

| No change | 69.1% | No | 17.3% | |||

| Save less | 4.1% | |||||

| N | 2,755 | N | 649 | |||

| D. View on home care subsidy | ||||||

| 1) Opinion on the policy | 2) Changes in the opinion | |||||

| Very much agree | 20.2% | More in favor | 37.9% | |||

| Agree | 48.2% | No change | 49.6% | |||

| Disagree | 20.1% | Less in favor | 12.5% | |||

| Very much disagree | 11.5% | |||||

| N | 2504 | N | 2294 | |||

Note: The number of respondents who completed the survey is 3,004. The tabulation for each question in this table does not include those who chose “Don’t know” or “Prefer not to say” as well as those who skipped the question. All the tabulations use the sampling weights. *This is a follow-up question for those who reported the willingness to save more.

Consistent with our theoretical prediction from Proposition 2, intended savings for older ages increase and the nursing home aversion seem to be a key driver of these higher intended savings (Panel C). Slightly more than a quarter of the sample (27%) reported being willing to save more for old age because of the pandemic (69% reported no change, while only 4% reported being less willing to save due to the pandemic). Among those who indicated a higher willingness to save, the vast majority (83%) said it is to avoid entering a nursing home.

The attitude towards a policy that subsidizes home care (see Panel D) is also consistent with the theoretical prediction (see Proposition 3). The exact question asked is: “Suppose the government were to propose a policy to increase the access to home care for people needing help with activities of daily living (ADLs) in order to reduce their likelihood of going to a nursing home, but would increase taxes to finance this policy. What do you think would be your opinion about such a policy?” The question thus makes it explicit that such a policy would not be costless and would likely result in higher taxes. Nonetheless, a majority of respondents indicated they would support this policy (20% very much agreed while another 48% agreed). Many (38%) also reported that the pandemic made them more favorable to such a policy (only 13% reported being less in favor due to the pandemic).

The unconditional distributions of survey responses are therefore in line with the predictions from Section 3. Older Canadians become less inclined to use nursing homes, which, in turn, increases their intended savings and also makes them more favorable towards a policy subsidizing home care. In the remainder of this section, we present evidence suggesting that the increase in the willingness to save as well as in the support for home care subsidies stem from individuals’ nursing home aversion. We also investigate which socioeconomic characteristics predict nursing home aversion, changes in precautionary savings, and support for home care subsidies.

Table 3 examines the sample characteristics of the respondents who declared to be less inclined to enter a nursing home due to the pandemic relative to the other respondents. Compared to those whose nursing home aversion did not increase, those who express a higher nursing home aversion (i.e. those who are less inclined to enter a nursing home) post-pandemic are more likely to be Québécois (as opposed to Ontarians), older, females, to live in common-law unions, to hold a university degree and to be retired. On the other hand, we do not find a meaningful difference between those with or without children (nor with or without children living close by), nor by average income or net worth. Overall, these results show that increased nursing home aversion is not confined to a specific socioeconomic group.

Table 3.

Who are less inclined to enter a nursing home post-pandemic?.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not less inclined | Less inclined | Difference | |

| (2) - (1) | |||

| Québec province (%) | 33.6 | 39.7 | +6.1*** |

| Age (%) | |||

| 50–54 | 31.9 | 26.3 | –5.5*** |

| 55–59 | 28.6 | 25.9 | –2.7 |

| 60–64 | 22.0 | 24.3 | +2.2 |

| 65–69 | 17.5 | 23.5 | +6.0*** |

| Female (%) | 47.6 | 51.7 | +4.1* |

| Marital status (%) | |||

| Married | 52.8 | 51.6 | -1.2 |

| Common-law | 11.9 | 15.3 | +3.3** |

| Widowed, separated, divorced | 20.8 | 17.8 | –3.0* |

| Never married | 14.5 | 15.3 | +0.9 |

| Education (%) | |||

| High school or less | 44.5 | 38.4 | –6.1*** |

| College | 29.8 | 30.5 | +0.7 |

| University | 25.7 | 31.1 | +5.4*** |

| Has a child (%) | 69.1 | 68.6 | –0.5 |

| Has a child 20km (%) | 53.1 | 51.7 | –1.4 |

| Work status (%) | |||

| Employed | 61.8 | 51.8 | –10.0*** |

| Retired | 29.7 | 39.6 | +9.9*** |

| Not working / Looking for work | 8.5 | 8.6 | +0.1 |

| Individual income (average, CAD) | 67,767 | 65,313 | -2,454 |

| Household wealth (average, CAD) | 772,824 | 873,181 | 100,357 |

Note: All the tabulations use the sampling weights. *, **, ***: significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level respectively.

5.2. Nursing home aversion and savings

The results in Table 2(C) already established that the increase in the willingness to save more is mainly driven by nursing home aversion. We confirm the link between the two by estimating a linear probability model where the dependent variable is the dummy variable of planning to save more due to the pandemic, and the key explanatory variable is the dummy variable of being less inclined to enter a nursing home post-pandemic.

As being less inclined to go to a nursing home because of the pandemic is correlated with demographic or socioeconomic variables such as age or education (see Table 3), we control for a large set of potential confounding variables. In particular, we control for wealth, income, risk aversion, gender, age, province, education, marital status, having children, having child living close by, the number of diagnosed health problems and work status (see Appendix B for further details).30

Table 4 shows the estimation results. Results of regressions without controls suggest that being less inclined to enter a nursing home increases the chance of intending to save more by 8.5 percentage points, which is about one-third of the unconditional average reported in Table 2C. When we add controls (Column (2)), the point estimate is even larger, at 10.5 percentage points. Both estimates are statistically significant at the 1% level. The estimated patterns are similar when the sample weights are not used (Columns (3) and (4)). If anything, the point estimates are larger. These results confirm that nursing home aversion is one of the main drivers of the increase in intended savings post-pandemic and that this is not sensitive to controlling for a large set of demographic and socioeconomic variables.31

Table 4.

Nursing home aversion and saving for older ages.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less inclined to enter a nursing home | 0.085*** | 0.105*** | 0.112*** | 0.140*** |

| (.028) | (.028) | (.019) | (.020) | |

| 2374 | 2261 | 2374 | 2261 | |

| adj. | 0.007 | 0.048 | 0.012 | 0.065 |

| Controls | N | Y | N | Y |

| Use sampling weights | Y | Y | N | N |

Note: This table presents OLS regression results where the dependent variable is whether respondent plans to save more due to the pandemic. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. See the text for the control variables included. *, **, ***: significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level respectively.

Regarding covariates, we find that being in Ontario, having a child that lives nearby, and being in the workforce predict a higher likelihood to be willing to save more for older ages because of the pandemic (see Table B.1 in the Appendix for details).

5.3. Nursing home aversion and home care subsidy

5.3.1. Support for home care subsidy

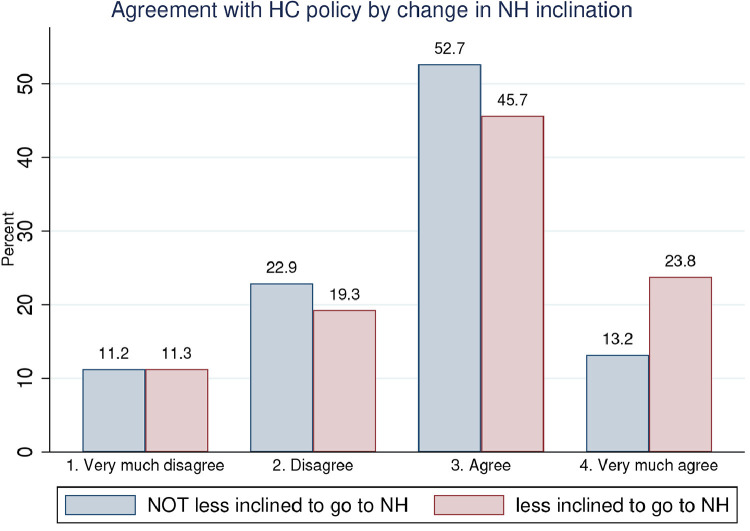

Next, we examine the relationship between the support for a policy that subsidizes home care and increased nursing home aversion. To do so, we plot in Fig. 3 the percentage of those who “very much disagree,” “disagree,” “agree,” and “very much agree” with the policy, separately for those whose nursing home aversion has increased and the rest. Among those who report to be less inclined to go to a nursing home, 23.8% report they very much agree with the policy, against 13.2% of those who declared to be more or equally inclined to go to a nursing home. Hence, this figure suggests that increased nursing home aversion increases the support for home care subsidy by increasing the probability to “very much agree” with the policy at the expense of the probabilities to “disagree” or simply “agree” with the policy. The most important shift seems to be from the “agree” response to the “very much agree” one.

Fig. 3.

Agreement with home care subsidy by change in inclination to go to a nursing home. Notes: This figure uses sampling weights.

To confirm this, we present in Table 5 the estimation results from multinomial logit models where the dependent variable is a dummy variable of the support for the policy in four categories (“very much agree,” “agree,” “disagree,” and “very much disagree”), while the key explanatory variable is being less inclined to enter a nursing home post-pandemic. We use the same set of control variables as in Table 4. Each column shows the average marginal effects of nursing home aversion in each model. Without any controls (Column (1)), we find, in line with Fig. 3, that increased nursing home aversion raises the chances of very much agreeing with subsidizing home care. Indeed, among those respondents who declared to be less inclined to enter a nursing home, their chances to very much agree with the policy is about 12 percentage points higher. This increase in the likelihood to very much agree with the policy is more than half the share of those who very much agree with such a policy (Table 2D). The effect is statistically significant at the 1% level. The estimated marginal effects are similar if we include controls (Column (2)). They are also robust to not using sampling weights, though the estimated magnitudes are slightly smaller in that case. In line with what we observe in Fig. 3, the table confirms that increased nursing home aversion increases the probability to very much agree with the policy, primarily at the expense of the probability to simply agree with the policy.

Table 5.

Support for home care subsidy and nursing home aversion.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very much agree | 0.118*** | 0.100*** | 0.094*** | 0.073*** |

| (.026) | (.027) | (.022) | (.023) | |

| Agree | –.077** | –.079*** | –.066*** | –.067*** |

| (.031) | (.032) | (.024) | (.025) | |

| Disagree | -.039 | –.033 | –.022 | –.009 |

| (.025) | (.026) | (.018) | (.019) | |

| Very much disagree | –.002 | 0.012 | –.006 | 0.003 |

| (.012) | (.019) | (.015) | (.015) | |

| 2229 | 2134 | 2229 | 2134 | |

| Controls | N | Y | N | Y |

| Use sampling weights | Y | Y | N | N |

Note: This table presents the average marginal effects of being less inclined to enter a nursing home on being in each category of support for a policy that subsidizes home care, estimated from multinomial logit regressions. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. See the text for the control variables included.

*, **, ***: significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level respectively.

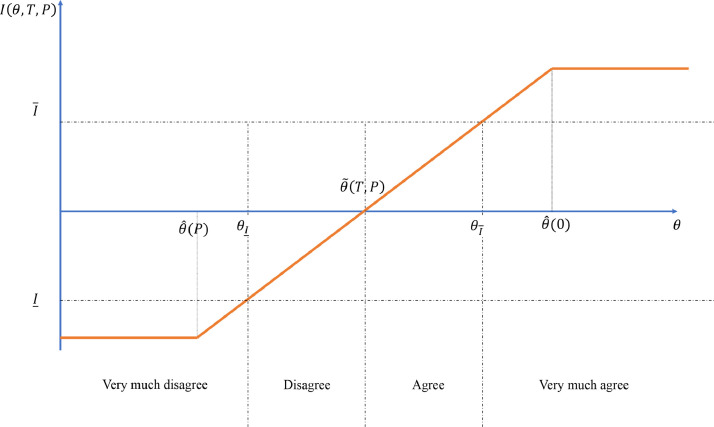

To map these empirical results to our theoretical model and to make sense of the observed patterns, we first reproduce in Fig. 4 the relationship between LTC preferences and the support for home care subsidy from Fig. 2 in Section 3.4.2. Recall that the vertical axis of this figure displays the (net) valuation of the subsidy (with corresponding taxes ) as a function of the relative preference for home care (). This valuation, denoted , is the difference between the utility with the subsidy and without the subsidy , measured for the chosen type care in each case. Those with choose to go to a nursing home (conditional on needing care) even with the subsidy, and hence, they exhibit the lowest support for this policy. On the other hand, those with would choose home care even without the subsidy, and so they value the subsidy the most. Those with will use home care only if the subsidy is implemented. Their support for the policy increases with , where the cut-off for being in favour of the policy is .

Fig. 4.

Long-term care preferences and mapping to the categories of the support for HC subsidy.

We map the level of support for the subsidy in Fig. 4 to the four categories of policy support in Table 5 in the following way. The cutoff between “agree” and “disagree” with the policy corresponds to , with a negative (resp., positive) net benefit from the policy below (resp., above). The thresholds used to separate “very much disagree” from “disagree” () and “very much agree” from “agree” () are somewhat arbitrary, and we assume that the former is above the minimum level of support (i.e. the level of support arising from those with ) while the latter is below the maximum level of support (i.e. that from those with ), as depicted in Fig. 4. The corresponding thresholds in terms of preferences are denoted and .32

We model the nursing home aversion caused by the pandemic in the following way. The distribution of before the pandemic is denoted by . During the pandemic, a random subset of the population learns negative information about nursing homes and hence, their relative preference for home care increases by . These agents form the ‘less-inclined’ group from Fig. 3. As a result, the preference distribution of the less-inclined group is a parallel rightward shift of that of the complementary group (i.e. the ‘not less inclined’ group in Fig. 3).

Under this assumption, the distribution of the policy support within the group with no change in LTC preferences (i.e. the blue bars in Fig. 3) reveals the underlying distribution pre-pandemic. A majority (52.7%) belong to the “agree” category (i.e., those with ). They would have used home care only with the subsidy and would have obtained positive net utility from such a subsidy. About one-fifth (22.9%) would have used home care with the subsidy though they would have preferred not having such a policy. For a small fraction of the population, the subsidy would have had no effect on their choice, putting them in either of the two extreme categories of policy support.

Regarding the impact of nursing home aversion on policy support, the model predicts that the less inclined group should have a stronger support for the policy compared to the complementary group. In particular, the chance that those who belong to the less-inclined group would “very much agree” with the policy should increase (by ), while the chance that they would “very much disagree” with the policy should decrease (by ). As a result, for the middle two categories, the expected change in the proportions of people belonging to these categories is ambiguous as there is an outflow to the category on the right as well as an inflow from the category on the left. A large and positive marginal effect of nursing home aversion on the chance of “very much agreeing” with the policy in Table 5 indeed supports the prediction from the model. We do not find statistically significant evidence that nursing home aversion reduces the chance of “very much disagreeing” with the policy, but only a very small fraction of the population belongs to this category of the policy support to begin with (Fig. 3). Lastly, a significant and negative marginal effect on the “agree” category suggests that the outflow from this category to the “strongly agree” category is much larger than the inflow from the “disagree” to the “agree” category (i.e. ). This is consistent with the fact that there were much fewer people “disagreeing” with the policy compared to those who “agreed” with the policy pre-pandemic (Fig. 3). So overall, the empirical results on the impact of nursing home aversion on the policy support are consistent with the key prediction from the model.

Note that the above interpretation relies on the assumption that the less-inclined group is drawn randomly from the pre-pandemic distribution of , which also implies no correlation between the chance of having a shift in the preference () and the pre-pandemic preference (). Since our regressions control for many demographic and socio-economic variables, the identified effects are free from potential correlation between the pre-pandemic preference and the impact of the pandemic that can be explained by those controls. In the next subsection, we look at the self-declared change in support for the policy because of the pandemic which de facto tackles concerns about unobserved heterogeneity.

Marginal effects of the controls entering Columns (2) and (4) of Table 5 are reported in Tables B.2 and B.3 in the Appendix. We find that those in the top three wealth quartiles are more in favor of the policy than those in the bottom wealth quartile, but that being in the top income quartile reduces the support for the policy (compared to those in the bottom income quartile). We also find that Québécois, those with at least a high school diploma, those who are currently working, those with more health problems, and those divorced or separated tend to be more in favor of such a policy.

5.3.2. Change in support for home care subsidy

We saw that increased nursing home aversion is associated with more support for a policy subsidizing home care. However, the previous estimates might not reflect any causal effect of increased nursing home aversion on the support for such a policy, as increased nursing home aversion and pre-pandemic support for the policy might be positively associated.

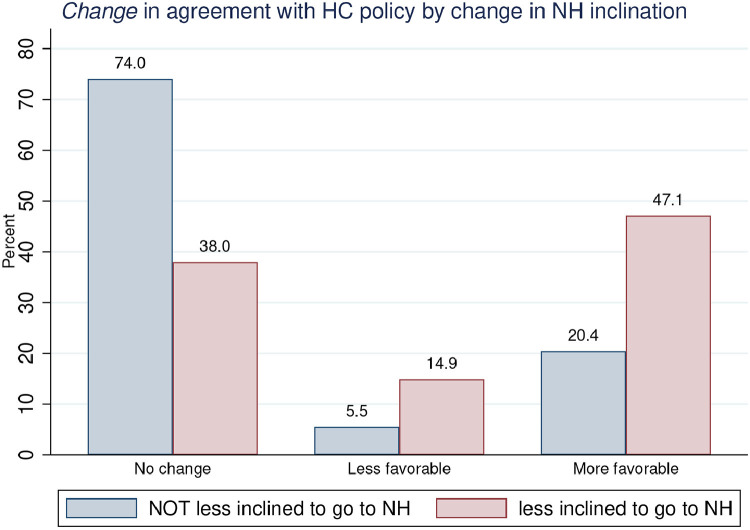

However, our survey also asked respondents how their support for such a policy changed because of the pandemic, and we confirm that increased nursing home aversion is also associated with increased support for a home care subsidy after the COVID pandemic, which provides support for our interpretation in Section 5.3.1. To show this, Fig. 5 first plots the change in the agreement with the policy separately for those less inclined to go to a nursing home because of the pandemic and for the rest. This figure suggests that increased nursing home aversion is associated with a much higher probability to be more in favor of the policy after the pandemic.

Fig. 5.

Change in agreement with home care subsidy by change in inclination to go to a nursing home. Notes: This figure uses sampling weights.

In Table 6, we further report the results from a multinominal logit estimation where the setup is identical to that in Table 5 except that the dependent variable is a dummy of the categories on the change in the support (“less in favor,” “more in favor,” and “no change”) for home care subsidy due to the pandemic. In line with Fig. 5, being less inclined to use a nursing home increases the chance of being more in favor of the policy by about 25 percentage points, which is robust to including controls and not using sampling weights. This is a large change, given that it represents about two-thirds of the fraction of those who became more in favor of such a policy (i.e. 38%, see Table 2D).

Table 6.

Change in the support for home care subsidy and nursing home aversion.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No change | -.344*** | -.337*** | -.345*** | -.354*** |

| (.026) | (.027) | (.021) | (.022) | |

| Less in favor | 0.095*** | 0.099*** | 0.081*** | 0.094*** |

| (.028) | (.027) | (.020) | (.021) | |

| More in favor | 0.249*** | 0.237*** | 0.264*** | 0.260*** |

| (.032) | (.032) | (.025) | (.026) | |

| 2081 | 2002 | 2081 | 2002 | |

| Controls | N | Y | N | Y |

| Use sampling weights | Y | Y | N | N |

Note: This table presents the average marginal effects of being less inclined to enter a nursing home on being in each category of change in the support for a policy that subsidizes home care, estimated from multinomial logit regressions. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. See the text for the control variables included. *, **, ***: significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level respectively.

Our model, summarized in Fig. 4, predicts that the less-inclined group, whose relative preference for home care increased by , should be more in favor of a home care subsidy (unless they already had a highest level of support, i.e. ). On the other hand, the not-less-inclined group, whose preference (equivalently, the degree of nursing home aversion) was not affected by the pandemic, should exhibit no change in the support for the policy. Hence, the result that nursing home aversion increases the chance of being more in favor of the policy and decreases the chance of having no change in the support is in line with the predictions from the model.33

Marginal effects of the control variables entering Columns (2) and (4) of Table 6 are reported in Tables B.4 and B.5 in the Appendix. We find that compared to those in the bottom wealth quartile, those in the top three wealth quartiles have a higher probability to declare themselves more in favor of the policy because of the pandemic, but that being in the top income quartile reduces this probability compared to being in the bottom income quartile. Being from Québec increases the probability to declare no change in support for the policy, mainly at the expense of being less in favor of the policy. Educational attainment higher than or equal to completing high school is associated with a higher probability to be more in favor of the policy. Finally, being widowed or divorced (compared to being married) and currently not working reduce the probability to be less in favor of the policy.

To sum up the findings in this section so far, survey evidence reveals that the information older individuals obtained about nursing homes during the pandemic has affected their expected choice of LTC, making them less inclined to enter a nursing home. The individuals that become more averse to entering a nursing home plan to save more in order to cover the higher cost needed to have proper LTC at home. At the same time, those individuals also express strong support for a policy that subsidizes home care, which could partially substitute for costly precautionary savings. Our theoretical framework provides a coherent explanation to all these observations about LTC-related choices post-pandemic.

5.4. Nursing home aversion and private LTCI demand

In our theoretical model and the above empirical analysis, we abstracted from the impact of nursing home aversion on private LTCI demand. As mentioned in Section 2, LTCI has so far been a rather marginal instrument for Canadians to protect themselves against LTC risk. There are various reasons for the small LTCI market, including Canadians being unfamiliar with private LTCI products (Boyer et al., 2020) and lack of suppliers. These as well as other factors highlighted in the rich literature on the LTCI demand puzzle suggest that increasing savings might be more attractive than purchasing LTCI.

Nonetheless, higher nursing home aversion and hence larger financial needs when needing LTC might increase the LTCI demand in Canada. To evaluate whether this is the case, the survey comprised two questions related to LTCI. First, it asked respondents if they ever thought about purchasing LTCI. To those who answer “yes” it further asked if the pandemic changed their interest in such a product. It did not ask this question to those who never thought about purchasing LTCI as they might have very limited or no knowledge about LTCI products which would make the second question irrelevant to them.

Among those who ever thought about purchasing LTCI (which represent a small share of respondents, in line with the observed low demand for LTCI), we find evidence that those who are less inclined to enter a nursing home because of the pandemic are more likely to say that their interest in purchasing LTCI has increased because of the pandemic. Evidence for the impact of nursing home aversion on LTCI demand is thus consistent with the evidence we found for savings and home care subsidies, as well as with the underlying mechanisms we highlighted in our model. Appendix C provides additional details.34

6. Conclusion

The current COVID-19 pandemic will change many aspects of our life post-pandemic. Its impact on LTC can be particularly large and persistent, due to COVID outbreaks at nursing homes during the first wave of the pandemic, and to extensive media coverage of these outbreaks. As a consequence, many people will choose to avoid entering a nursing home and instead receive LTC at home, notwithstanding the higher cost of the latter. Our model of LTC choice shows that such nursing home aversion will increase households’ desired savings for old ages. The model also shows that since such self-insurance is costly, many households would support a policy that will make home care more affordable. The evidence from our survey supports all the predictions from our model. Those who express nursing home aversion post-pandemic are more likely to engage in additional precautionary savings. They also tend to support a policy that subsidizes home care. The qualitative nature of the survey questions used in this paper does not allow us to pin down the optimal design of the subsidy nor quantify the strength of the support for a specific form of subsidy. Nonetheless, the responses are indicative of strong demand for affordable alternatives to nursing home care for the elderly population and therefore, for policies that will provide such alternatives.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

This paper draws on research supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Grant 435-2020-0787) and by Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Société et Culture (Grant 2019-SE2-252890). De Donder acknowledges funding from ANR under grant ANR-17-EURE-0010 (Investissements d’Avenir program) and from the Chair “Marché des risques et création de valeurs, fondation du risque/Scor”. We are grateful to David Boisclair and Julien Navaux for help with the survey, and to Peter van Bergeijk and Raun van Ooijen for helpful discussions of the paper. The usual disclaimer applies. Declarations of interest: none.

LTC is defined as “help with activities of daily living such as washing and dressing, or help with household activities such as cleaning and cooking” (OECD, 2011). LTC often comes with additional support such as medical assistance. Individuals in need of LTC are called dependent.

Those debates are not limited to the Canadian context that we study. For instance, increasing government spending on home health care to avoid reliance on nursing homes is currently debated in the US as well (see Leonhardt and Philbrick (2021)).

About the LTCI puzzle, see the surveys by Brown and Finkelstein (2009); OECD (2011) and Pestieau and Ponthiere (2011).

For instance, Gollier (2020) studies the costs and benefits of different strategies to lift lockdowns, while Salanié and Treich (2020) compare public and private incentives for protection against pandemic risk. Antràs et al. (2020); Bonadio et al. (2021); Bricongne et al. (2021) study the impact of COVID on trade and globalisation, while Kahn et al. (2020); Cajner et al. (2020), and Kurmann et al. (2021) analyze its impact on labour markets and on firms.

See Ontario (2022b).