Abstract

Pediococcus damnosus can coflocculate with Saccharomyces cerevisiae and cause beer acidification that may or may not be desired. Similar coflocculations occur with other yeasts except for Schizosaccharomyces pombe which has galactose-rich cell walls. We compared coflocculation rates of S. pombe wild-type species TP4-1D, having a mannose-to-galactose ratio (Man:Gal) of 5 to 6 in the cell wall, with its glycosylation mutants gms1-1 (Man:Gal = 5:1) and gms1Δ (Man:Gal = 1:0). These mutants coflocculated at a much higher level (30 to 45%) than that of the wild type (5%). Coflocculation of the mutants was inhibited by exogenous mannose but not by galactose. The S. cerevisiae mnn2 mutant, with a mannan content similar to that of gms1Δ, also showed high coflocculation (35%) and was sensitive to mannose inhibition. Coflocculation of P. damnosus and gms1Δ (or mnn2) also could be inhibited by gms1Δ mannan (with unbranched α-1,6-linked mannose residues), concanavalin A (mannose and glucose specific), or NPA lectin (specific for α-1,6-linked mannosyl units). Protease treatment of the bacterial cells completely abolished coflocculation. From these results we conclude that mannose residues on the cell surface of S. pombe serve as receptors for a P. damnosus lectin but that these receptors are shielded by galactose residues in wild-type strains. Such interactions are important in the production of Belgian acid types of beers in which mixed cultures are used to improve flavor.

Yeast flocculation is the spontaneous aggregation of cells to form clumps that can be easily separated from the medium (19) and plays an important role in the brewing industry. In most cases, cell wall glycoproteins are involved and induce flocculation by binding to lectin-type sugar receptors on neighboring cells (6, 7, 13, 17, 22, 23, 24, 27). Such flocculation can be inhibited by monomeric or oligomeric sugars or by calcium-chelating agents. In nonsexual flocculation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe, galactose residues in the cell wall glycoproteins are bound by lectin-type sugar receptors of the flocculent yeast cell wall (27). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, mannose chains present on the yeast cell surface react with neighboring cells via N-terminal domains of the proteins encoded by dominant flocculation genes (9, 14).

Mannose-specific yeast cell aggregation can also be induced by piliated enterobacteria such as Escherichia, Klebsiella, Salmonella, and Enterobacter (4, 5, 15, 18) and by isolated mannose-specific pili (or fimbriae) of Escherichia coli or Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (10, 18). We have observed mannose-specific coaggregation of S. cerevisiae and Pediococcus damnosus, a gram-positive bacterium (12, 16). The coflocculation of yeast and bacteria may increase bacterial contamination in yeast-based fermentation processes or benefit the production of Belgian acid ales, which rely on the persistent association of P. damnosus with S. cerevisiae for acidification (29).

P. damnosus also coflocculates Candida utilis, Dekkera bruxellensis, Hanseniaspora guilliermondii, Kloeckera apiculata, and S. pombe (16). However, S. pombe coflocculates much less frequently (5%) than the other yeasts (25 to 50%) (16). Our objective in this study was to investigate whether the reduced coflocculation is attributable to the high number of galactose residues in the S. pombe cell wall glycoproteins. Therefore, three S. pombe strains which are isogenic but differ only by their cell surface galactose residues were studied. For comparison, an S. cerevisiae mnn2 mutant with an unbranched α-1,6-polymannose chain similar to S. pombe galactose-deficient mannan was also examined. This work is the first to elucidate the physiological role of galactose residues in yeast cell walls in the interactions with bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast and bacterial strains and growth media.

Yeast and bacterial strains (Table 1) were grown at 28°C on a reciprocal shaker (150 strokes min−1) in standard YPD media (21) for yeasts for 24 h or in MRS (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) medium for P. damnosus for 72 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min. All cells were washed with 100 mM EDTA (pH 8) for 15 min with vigorous shaking, rinsed three times with distilled water, and finally resuspended in distilled water to obtain 110 to 150 mg ml−1 (wet weight, approximately 1010 cells ml−1).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| S. pombe TP4-1D | Parental strain (h+ leu1 his2 ura4 ade6-M216), Man:Gal = 5:6 | 25, 26, 27 |

| S. pombe gms1-1 | Galactosylation mutant of TP4-1D, Man:Gal = 5:1 | 26 |

| S. pombe gms1Δ | Galactosylation deletion mutant of TP4-1D, Man:Gal = 1:0 | 25, 27 |

| S. cerevisiae Euroscarf Y00000 | Parental strain BY4741 (MATa; his3Δ1; leu2Δ0; met15Δ0; ura3Δ0), Man:Gal = 1:0 | 3 |

| S. cerevisiae Euroscarf Y03125 | mnn2 mutant of BY4741 (MATa; his3Δ1; leu2Δ0; met15Δ0; ura3Δ0::kanMX4), Man:Gal = 1:0 | 21 |

| P. damnosus 12A7 | From laboratory collection, originally isolated from Belgian lambic beer | 12, 16 |

Coflocculation assay.

The coflocculation of yeast and bacteria was determined as described previously (12, 16). Briefly, the bacterial and yeast cell suspensions (100 μl each, approximately 1010 cells ml−1) were added to 3.8 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) in 12-ml tubes. This yielded a total final cell concentration of approximately 5 × 108 cells ml−1, which was determined previously to give maximum coflocculation (data not shown). The tubes were then shaken at 150 strokes min−1 on a reciprocal shaker at 28°C for 4 h, at which point the coflocculation reached a steady state. As controls, 100 μl of each strain was added to 3.9 ml of the buffer. After shaking, the suspensions were allowed to settle for 10 min. The upper 3.5 ml of the solution was removed and brought with water to a volume of 4 ml in a second tube; this suspension was designated A. The precipitate was taken up with 3.5 ml of water, and this suspension was designated B. From the control samples, 3.5 ml was also removed, and the remaining 0.5 ml was also diluted with water to 4 ml (suspensions were designated C for bacteria and D for yeast). All tubes were vortexed to homogenize the suspensions, whose cell optical densities (ODA, ODB, ODC, and ODD) were measured spectrophotometrically using an Ultrospec IIE (LKB Products, Bromma, Sweden) instrument set at 600 nm. The coflocculation-inducing activity is the percentage of the settled cells to the total mixed cells expressed as follows: (ODB−ODC−ODD)/(ODA + ODB) × 100%. All assays were done in triplicate and averages ± standard deviations were reported. Coflocculent cells were examined microscopically.

pH and cations.

The effect of pH was evaluated by resuspending the EDTA-treated cells in distilled water and adjusting pH with 2 N HCl or 2 N NaOH. Cation effects were evaluated by adding Li+, Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Co2+, Cu2+, or Hg2+ in the form of chloride salts at a concentration of 50 mM to the cell suspensions at pH 6.

EDTA and EGTA.

The effects of EDTA and EGTA were studied with cell suspensions either in water or in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 6.

Sugars, N-linked gms1Δ mannan, concanavalin A, and Narcissus pseudonarcissus lectin.

Different sugars were added to the cell suspensions in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6) at a concentration of 100 or 500 mM. N-linked mannan was isolated from the S. pombe gms1Δ (1) and subsequently added to the cell mixture in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6) to a final concentration of 25 mg ml−1. Jack Bean concanavalin A (ConA; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was added to final concentrations ranging from 50 to 2,500 mg l−1 (to investigate dose-response inhibition), and N. pseudonarcissus lectin (NPA) (prepared from N. pseudonarcissus by affinity chromatography on immobilized mannoses [8]) specific for α-1,6 linkages (28) was added to a final concentration of 400 mg l−1.

Enzymatic treatment of yeast and bacterial cells.

Suspensions of 109 yeast or bacterial cells ml−1 in 25 mM EDTA–10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) were incubated with 0.5-mg ml−1 proteinase K or 1-mg ml−1 trypsin (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Pennzberg, Germany) at 35°C for 90 min with shaking. Enzyme-treated cells were washed with water and used in coflocculation assays. Yeast cells were also treated with 1-mg ml−1 zymolyase-100T (Seikagaku Kogyo Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in 1 M sorbitol–25 mM EDTA–10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) to promote the formation of spheroplasts (14). Spheroplasts were collected by centrifugation at 940 × g for 10 min and washed three times with 1 M sorbitol. In the coflocculation experiments, spheroplasts were suspended in 1 M sorbitol–50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6). As a control, cells were incubated under the same conditions without enzymes.

RESULTS

Coflocculation of P. damnosus with yeast.

Wild-type cells of S. pombe TP4-1D induce only 5% coflocculation, compared to 45% coflocculation obtained for gms1Δ and 30% for gms1-1 (Table 2). These strains are isogenic and differ only by their cell surface galactose residues (25, 26), so coflocculation appears to be related to the level of galactosylation of mannogalactose proteins in the cell wall. Compared to the wild type, S. cerevisiae mnn2, with unbranched side chain polymannose, also gave a high coflocculation with P. damnosus (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effects of sugars and ConA on percentage of coflocculation between P. damnosus 12A7 and different yeast strains in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 6

| Coflocculation solution (concn) | % Coflocculation (mean ± SD)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S. pombe

|

S. cerevisiae

|

||||

| TP4-1D (Man:Gal = 5:6) | gms1-1 (Man:Gal = 5:1) | gms1Δ (Man:Gal = 1:0) | BY4741 (Man:Gal = 1:0) | mnn2 (Man:Gal = 1:0) | |

| PBa | 5.3 ± 1.6 | 30 ± 1.3 | 45 ± 3.8 | 50 ± 4.3 | 37 ± 3.1 |

| PB+Man (100 mM) | NCb | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 10 ± 2.2 | NTc | NC |

| PB+Man (500 mM) | NC | NC | NC | NT | NC |

| PB+Gal (100 mM) | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 30 ± 3.4 | 45 ± 0.7 | NT | 37 ± 2.0 |

| PB+gms1Δ mannan (25 mg ml−1) | NT | NT | NC | NT | NC |

| PB+Con A (800 mg l−1) | 1.7 ± 1.3 | NT | 24 ± 3.3 | 7.4 ± 1.5 | 5.2 ± 2.6 |

| PB+NPA (400 mg l−1) | NT | NT | NC | NT | NC |

PB, 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6).

NC, no coflocculation; this includes all values of ≤0 but ≥−5.

NT, not tested.

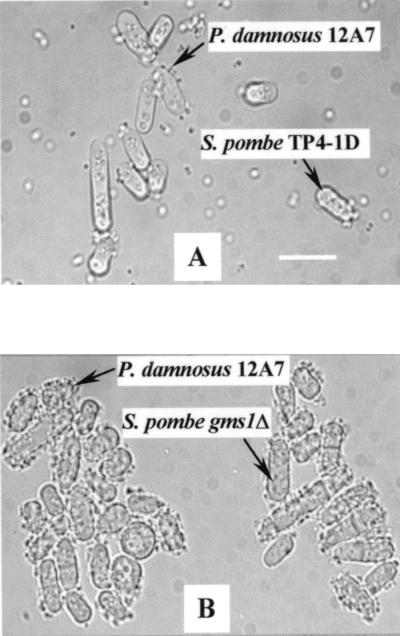

Microscopic observation of the coflocculation of P. damnosus and yeast.

With the wild type very few cells of the bacterium bound to the yeast, whereas the surface of mutant gms1Δ cells was fully surrounded by the bacteria, resulting in a flocculating network of cells (Fig. 1). Under the conditions of the experiment, almost all P. damnosus cells were bound by the mutant S. pombe gms1Δ cells, while most of the P. damnosus cells remained free when mixed with the wild-type S. pombe. S. pombe mutant gms1-1 and S. cerevisiae mnn2 gave results comparable to those of S. pombe gms1Δ. In general, flocs with diameters of ≥100 μm were formed.

FIG. 1.

Micrographs of coflocculation of P. damnosus 12A7 with S. pombe TP4-1D (A) and its mutant gms1Δ (B). Bar, 10 μm. With TP4-1D, very few bacterial cells bind to the yeast while the surfaces of mutant gms1Δ cells are completely surrounded by the bacteria, resulting in a flocculating network of cells.

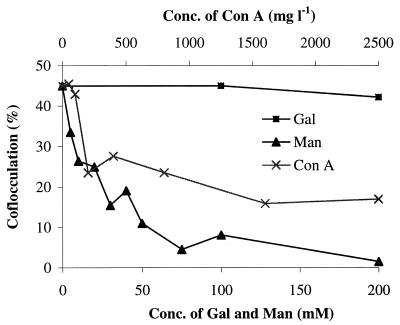

Effects of sugars, gms1Δ mannan, ConA, and NPA lectin on coflocculation of P. damnosus with yeasts.

In the presence of 100 mM mannose, coflocculation did not occur with the S. pombe wild type and was greatly reduced for its mutants gms1-1 and gms1Δ. When the mannose concentration was increased to 500 mM, no coflocculation occurred with the mutants either. Addition of galactose eliminated the coflocculation with the S. pombe wild type but had no effects on the coflocculation with the mutants. The mannose inhibition of the coflocculation with S. pombe gms1Δ mutant is sugar concentration dependent (Fig. 2). Other sugars such as fructose, glucose, inositol, lactose, melibiose, and raffinose had no inhibitory effects at the concentration of 100 mM (data not shown). Mannose, but not galactose, completely inhibits the coflocculation of P. damnosus and S. cerevisiae mnn2 (Table 2). These results suggest that coflocculation involves a mannose-specific lectin-like binding between the bacteria and both the S. cerevisiae and the S. pombe mutants. N-linked gms1Δ mannan completely inhibited the coflocculation of P. damnosus with S. pombe gms1Δ and with S. cerevisiae mnn2, confirming the lectin-like interaction between P. damnosus and the yeast cell surface mannan.

FIG. 2.

Effects of mannose, galactose, and ConA on coflocculation of P. damnosus 12A7 and S. pombe gms1Δ in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6). Each point represents the mean of three measurements, and the standard deviation is less than 10%.

Since ConA is a glucospecific and mannospecific lectin (21), ConA also should interfere with coflocculation. The coflocculation of S. pombe gms1Δ and P. damnosus was partially inhibited by ConA, and the inhibition was dose dependent (Fig. 2; Table 2). When ConA was added to a suspension of gms1Δ and P. damnosus cells, the flocs formed were smaller (diameter, ≤50 μm). Addition of ConA to the preformed large flocs (diameter, ≤125 μm) of gms1Δ and P. damnosus resulted in their disassociation into smaller flocs. We interpret these results to mean that ConA acts as a lectin competing with the bacterial lectin. Similar observations were made between S. cerevisiae mnn2 or its wild-type strain BY4741 and P. damnosus. The low coflocculation of the S. pombe wild type with P. damnosus was also reduced by ConA (Table 2). Coflocculation of P. damnosus with S. pombe gms1Δ and S. cerevisiae mnn2 was completely inhibited by NPA (Table 2), suggesting a binding specificity for α-1,6 linkage between the bacterium and the yeasts.

Effects of pretreatment of yeast and bacterial cells with enzymes on coflocculation of P. damnosus with yeasts.

Preincubation of P. damnosus cells with proteinase K or trypsin prevented coflocculation (Table 3). The treatment of yeast cells with one or the other of these two enzymes reduced the coflocculation from 45 to 38 or 35%, respectively, possibly due to their effects on the protein part of the glycoprotein or to a reduction of cell wall-bound mannoproteins (14). Digestion of the yeast cell wall with zymolyase completely abolished the coflocculation. We conclude that the lectin is a protein located on the outer surface of P. damnosus and that the lectin receptor is located in the yeast cell wall.

TABLE 3.

Coflocculation between S. pombe gms1Δ and P. damnosus 12A7 with and without enzyme treatment

| Treatment

|

% Coflocculation (mean ± SD) | Coflocculation solution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. damnosus | S. pombe gms1Δ | ||

| None | None | 45 ± 3.8 | PBa |

| None | None | 42 ± 1.6 | PB + SBb |

| Proteinase K | None | NCc | PB |

| Trypsin | None | NC | PB |

| None | Proteinase K | 38 ± 1.5 | PB |

| None | Trypsin | 35 ± 0.1 | PB |

| None | Zymolyase | NC | PB + SB |

PB, 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6).

SB, 1 M sorbitol.

NC, no coflocculation; this includes all values of ≤0 but ≥−5.

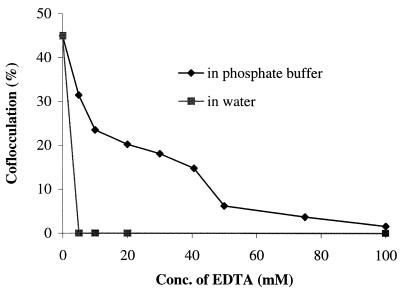

Effects of cations, pH, EDTA, and EGTA on coflocculation.

Compared to cells in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6), a lower but appreciable level of coflocculation (30%) occurred between EDTA-washed P. damnosus and S. pombe gms1Δ cells in distilled water at pH 6. Coflocculation of S. pombe gms1Δ and P. damnosus in water was enhanced in the presence of Li+ (44% ± 2.1%), Na+ (45% ± 3.0%), Ca2+ (45% ± 1.9%), Mn2+ (38% ± 3.5%), Co2+ (37% ± 1.9%), K+ (51% ± 2.6%), and Mg2+ (51% ± 1.5%) and reduced in the presence of Cu2+ (10% ± 2.1%) and Hg2+ (3.8% ± 1.6%). No coflocculation occurred in water containing 5 mM EDTA (Fig. 3). When 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6) which contains Na+ was substituted for water, then the EDTA concentration had to be increased to 100 mM (Fig. 3) before coflocculation no longer occurred. The same results were obtained using EGTA (data not shown). The coflocculation of P. damnosus and gms1Δ occurred over a broad pH range (from pH 4 to 9), as did that of P. damnosus and S. cerevisiae.

FIG. 3.

EDTA inhibition of the coflocculation of P. damnosus 12A7 and S. pombe gms1Δ in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6) and distilled water (pH 6). Each point represents the mean of three measurements, and the standard deviation is less than 10%.

DISCUSSION

In the aggregation of S. cerevisiae induced by P. damnosus, bacterial lectins bind with the mannose residues on the yeast cell surface (12), with similar results observed with C. utilis, D. bruxellensis, H. guilliermondii, K. apiculata, and S. pombe (16). The lowest coaggregation occurred with S. pombe, a yeast characterized by a high proportion of galactose residues bound by α-1,2 linkages to a α-1,6 polymannose main chain in its mannoproteins in the cell wall (2). These α-linked galactose residues bind to a galactose-specific lectin for nonsexual flocculation (27). Galactose-dependent aggregation is of interest for the interactions of yeasts with higher eukaryotes because galactose residues are very common in the glycoproteins of most higher eukaryotes (25).

The limited aggregation between the S. pombe wild type and P. damnosus was eliminated by both mannose and galactose. This result could imply that P. damnosus has two types of lectins: one specific for mannose and another specific for galactose but with low specificity. P. damnosus lectins are highly reactive with mannose residues (12). We hypothesize that the low reactivity of wild-type S. pombe with the bacterium is due to shielding of the mannose residues by galactose side branches. This hypothesis is supported by the data from the galactose-deficient mutants, gms1-1 and gms1Δ. No nonsexual aggregation of these mutants occurs (27), but they still coflocculate with P. damnosus. Thus, the galactose side branches are not needed for coaggregation with P. damnosus. This mannose-dependent coaggregation was inhibited by mannose, by a mannan obtained from the galactose-deficient mutant, and by ConA, leading us to hypothesize that for S. pombe a mannose-specific, lectin-like binding also occurs between the bacteria and the yeast. As with S. cerevisiae (12), coaggregation was abolished when the bacterial cells were treated with proteases or if the yeast cell walls were removed by zymolyase, suggesting that the bacterial lectin is binding to the mannose residues on the yeast cell surface.

Nonsexual flocculation of S. pombe requires outer-chain galactose side branches (27), but P. damnosus adhesins react with the main α-1,6-linked polymannose chain. Outer-chain side branches also are required for nonsexual flocculation of S. cerevisiae. In this yeast, however, the side branches are mannose residues (21). The S. cerevisiae mnn2 mutant has only unbranched main-chain polymannose and can still be efficiently flocculated by P. damnosus (Table 2). Thus, the mechanisms of nonsexual flocculation in both S. cerevisiae and S. pombe are different from the P. damnosus-dependent reaction, i.e., side branches with either mannose or galactose are required for nonsexual flocculation but mannose is required for aggregation of the yeasts by P. damnosus. The inhibition of the coflocculation by NPA also suggests a specific interaction with α-1,6 linked mannose residues.

Yeast flocculation commonly requires a cation and can be blocked by EDTA (14, 20, 27). Although Ca2+ is most frequently involved, other cations such as Mn2+, Cu2+, Li+, or Mg2+ (14, 27) also play a role. Contrary to the nonsexual self-flocculation of S. pombe (27), the coflocculation of S. pombe gms1Δ and P. damnosus was inhibited by Cu2+, and EDTA-treated yeast and bacterial cells could still coflocculate even in the absence of any cation. These results can be explained by the presence of residual calcium ions in cell wall layers that do not react with EDTA. When the cells are mixed in water these ions may leak to the cell surface or to the solution and activate the lectin-type reactions, as observed by Stratford (20). This mechanism could explain why EDTA inhibits the coflocculation when it is added during the coflocculation assays. In phosphate buffer which introduces sodium ions, the EDTA concentration needed to inhibit the coflocculation must be increased. We attribute this result to the promoting effect of sodium ions on the leakage of calcium ions (11, 20).

In conclusion, our results indicate that there are significant differences between the nonsexual self-flocculation of S. cerevisiae or S. pombe and the flocculation induced by P. damnosus. For self-flocculation, side branches of the main polymannose chain are required, but for flocculation induced by P. damnosus, only available mannose residues are needed. In brewing processes, acidification by lactic acid bacteria such as P. damnosus can persist due to their binding to S. cerevisiae brewing strains. Although this binding can be favorable in the production of some Belgian special beers, in classical brewing processes the association between yeast and bacteria increases the risks for contamination and unwanted acidification. The associations rely on the interaction of bacterial lectins with mannose residues in the yeast cell wall. The shielding of mannose residues by galactose side branches now found for S. pombe could explain why this yeast does not associate with P. damnosus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Takegawa for providing S. pombe strains and W. J. Peumans for providing NPA lectin.

X. Peng and J. Sun were supported by fellowships from KULeuven.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballou C E. Isolation, characterization, and properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mnn mutants with nonconditional protein glycosylation defects. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:440–470. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85038-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballou C E, Ballou L, Ball G. Schizosaccharomyces pombe glycosylation mutant with altered cell surface properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9327–9331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brachmann C B, Davies A, Cost G J, Caputo E, Li J, Hieter P, Boeke J D. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast. 1998;14:115–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980130)14:2<115::AID-YEA204>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Firon N, Ofek I, Sharon N. Interaction of mannose-containing oligosaccharides with the fimbrial lectin of Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982;105:1426–1432. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)90947-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Firon N, Ofek I, Sharon N. Carbohydrate-binding sites of the mannose-specific fimbrial lectins of enterobacteria. Infect Immun. 1984;43:1088–1090. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.1088-1090.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussain T, Salhi O, Lematre J, Charpentier C, Bonaly R. Comparative studies of flocculation and deflocculation of Saccharomyces uvarum and Kluyveromyces bulgaricus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1986;23:269–273. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson B F, Walker T, Miyata M, Miyata H, Calleja G B. Sexual coflocculation and asexual self-flocculation of heterothallic fission-yeast cells (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) Can J Microbiol. 1987;33:684–688. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaku H, Van Damme E J, Peumans W J, Goldstein I J. Carbohydrate-binding specificity of the daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus) and amaryllis (Hippeastrum hybr.) bulb lectins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;279:298–304. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90495-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi O, Hayashi N, Kuroki R, Sone H. Region of Flo1 proteins responsible for sugar recognition. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6503–6510. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6503-6510.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korhonen T K. Yeast cell aggregation by purified enterobacterial pili. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1979;6:421–425. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuriyama H, Umeda I, Kobayashi H. Role of cations in the flocculation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and discrimination of the corresponding proteins. Can J Microbiol. 1991;37:397–403. doi: 10.1139/m91-064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lievens K, Devogel D, Iserentant D, Verachtert H. Evidence for a factor produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae which causes flocculation of Pediococcus damnosus 12A7 cells. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 1994;2:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez X C, Pearson B M, Stratford M. Unusual flocculation characteristics of the yeast Candida famata (Debaryomyces hansenii) Lett Appl Microbiol. 1993;16:44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miki B L A, Poon N H, James A P, Seligy V L. Possible mechanism for flocculation interactions governed by gene FLO1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:878–889. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.2.878-889.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ofek I, Beachey E H. Mannose binding and epithelial cell adherence of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1978;22:247–254. doi: 10.1128/iai.22.1.247-254.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng X, Sun J, Iserentant D, Michiels C, Verachtert H. Flocculation and coflocculation of bacteria by yeasts. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;55:777–781. doi: 10.1007/s002530000564. http://link.springer-ny.com/link/service/journals/00253/contents/00/00564/ . (First published 26 April 2001; http://link.springer-ny.com/link/service/journals/00253/contents/00/00564/. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saito K, Sato S I, Shimoi H, Iefuji H, Tadenuma M. Flocculation mechanism of Hansenula anomala J224. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:1425–1432. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharon N, Firon N. Oligomannoside units of cell surface glycoproteins as receptors for bacteria. Pure Appl Chem. 1983;55:671–675. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart G G. Yeast flocculation: practical implications and experimental findings. Brew Dig. 1975;50:42–62. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stratford M. Yeast flocculation: calcium specificity. Yeast. 1989;5:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stratford M. Yeast flocculation: receptor definition by mnn mutants and concanavalin A. Yeast. 1992;8:635–645. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stratford M, Pearson B M. Lectin-mediated flocculation of the yeast Saccharomycodes ludwigii NCYC 734. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1992;14:214–216. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzzi G, Romano P, Westall F, Vannini L. The flocculation of wine yeasts: biochemical and morphological characteristics in Kloeckera apiculata. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;69:273–277. doi: 10.1007/BF00399616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzzi G, Romano P, Benevelli M. The flocculation of wine yeasts: biochemical and morphological characteristics in Zygosaccharomyces. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1992;61:317–322. doi: 10.1007/BF00713939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabuchi M, Tanaka N, Iwahara S, Takegawa K. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe gms1+ gene encodes an UDP-Galactose transporter homologue required for protein galactosylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;232:121–125. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takegawa K, Tanaka N, Tabuchi M, Iwahara S. Isolation and characterization of a glycosylation mutant from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1996;60:1156–1159. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka N, Awai A, Bhuiyan M S A, Fujita K, Fukui H, Takegawa K. Cell surface galactosylation is essential for nonsexual flocculation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1356–1359. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1356-1359.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Damme E J M, Peumans W J, Pusztai A, Bardocz S, editors. Handbook of plant lectins: properties and biomedical applications. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verachtert H, Shanta Kumara M C, Dawoud E. Yeasts in mixed cultures with emphasis on lambic beer brewing. In: Verachtert H, De Mot R, editors. Yeast: biotechnology and biocatalysis. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1990. pp. 429–478. [Google Scholar]