Abstract

Background

Hospital at home (HaH) provides hospital‐level care at home as a substitute for traditional hospital care. Interest in HaH is increasing markedly. While multiple studies of HaH have demonstrated that HaH provides safe, high‐quality, cost‐effective care, there remain many unanswered research questions. The objective of this study is to develop a research agenda to guide future HaH‐related research.

Methods

Survey of attendees of first World HaH Congress 2019 for input on research for the future HaH development. Selection and ranking of important topic areas for future HaH‐related research. Development of research domains and research questions and issues using grounded theory approach, supplemented by focused literature reviews.

Results

240 conference attendees responded to the survey (response rate, 55.3%). The majority were from Europe (64%) and North America (11%) and were HaH program leaders (29%), HaH physicians (27%), and researchers (13%). Nine research domains for future HaH research were identified: 1) definition of the HaH model of care; 2) the HaH clinical model; 3) measurement and outcomes of HaH; 4) patient and caregiver experience with HaH; 5) education and training of HaH clinicians; 6) technology and telehealth for HaH; 7) regulatory and payment issues in HaH; 8) implementation and scaling of HaH; and 9) ethical issues in HaH. Key research issues and questions were identified for each domain.

Conclusions

While highly evidence‐based, unanswered research questions regarding HaH remain, focusing research efforts on the domains identified in this study will serve to improve HaH for all key HaH stakeholders.

Keywords: home‐based care, Hospital at home, research agenda

Key points

A Hospital at home (HaH) research agenda was developed

Key research domains include: HaH definition; measurement and outcomes; patient and caregiver experience; education and training; technology; regulation and payment; and scaling of HaH

Why does this paper matter?

This agenda will guide optimal HaH research and funding priorities.

INTRODUCTION

Hospital at home (HaH) provides hospital‐level care in the home as a substitute for traditional hospital care. 1 Before the coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, interest in HaH had been increasing as health systems expanded their value‐based care initiatives. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 With the COVID‐19 pandemic, interest in HaH increased substantially around the world as health systems sought alternatives to facility‐based acute care. In the United States, HaH adoption increased markedly in response to a public health emergency‐related payment mechanism and regulatory framework offered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that provided a hospital diagnosis–related group (DRG) payment for HaH care. 6 , 7

HaH has been the subject of multiple research studies, including many randomized‐controlled trials and systematic reviews. These studies have reported on a specific range of outcomes and research questions including medical outcomes, patient and caregiver experience, quality and safety, quality of life, utilization, and cost. Overall, these studies have demonstrated that providing acute hospital‐level care at home is feasible and effective; patients opt into HaH care at high rates; high‐quality care is provided with lower rates of iatrogenic complications (including mortality, in some studies), patient and caregiver experience is better, and costs are lower in comparison with traditional acute hospital care. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 As interest in HaH grows, additional questions worthy of study are emerging. In April 2019, the first World Hospital at Home Congress was convened. The aim of this study was to leverage input from Congress attendees to develop a research agenda to guide HaH‐related research into the future.

METHODS

Survey development

The investigators developed a 6‐question survey (see Data S1) to inform the development of a research agenda for HaH. The survey was pilot‐tested by 4 HaH clinicians and refined based on their feedback. Respondents reported the continent where they worked, their main role(s) in HaH, and the number of patients treated annually in their HaH, if applicable. The survey then asked respondents to select all items that needed to be addressed in future research related to HaH from a list of 22 potential research topic areas developed iteratively by the investigators and a free‐text option to add additional research topics or specific research questions to the list. From this same list, respondents were asked to select the 5 most important areas for HaH research, again with free text option. The final question asked respondents to provide any additional thoughts regarding research issues for HaH in free text.

Survey deployment

A link to the online anonymous Qualtrics survey was sent via email to all advance registrants 1 week prior to the first World Hospital at Home Congress convened in Madrid, Spain in April 2019. A reminder email was sent on the first day of the Congress. At various Congress sessions, attendees were encouraged to complete the survey. No remuneration was provided. Informed consent was obtained of respondents in the opening screen of the survey.

Analysis

Survey data

Survey responses were compiled in the Qualtrics system. We describe the characteristics of our respondents and their selection and prioritization of research agenda items with simple percentages. Investigators (DML, BL) reviewed all free‐text suggestions (N = 66) for additional HaH research topics. As appropriate, suggestions were assigned to the previously developed 22 potential HaH research topic areas; one additional topic area was added based on free text input.

Domain development

To identify and refine key ideas and themes from the data, investigators employed a grounded theory approach 17 to develop research domains. Investigators, first independently, then as a group, iteratively categorized the potential HaH research topic areas into broader research domains using the data from the survey respondents. Nine research domains captured all the potential HaH research topic areas. For each domain, a focused narrative literature review was conducted to understand the current state of knowledge/research related to that domain. 18 , 19 A Pubmed search from 1976 forward until January 2021 was conducted using the search strategy: “hospital at home” [TI] or “home hospital”[TI]. Key words associated with each of the domains were then added to this basic search term to conduct domain‐specific searches. Abstracts and relevant articles were reviewed by the investigators. Each domain was assigned to an investigator who developed a draft set of research priorities and questions related to the domain, which were reviewed by all the investigators in two rounds of review for inclusion in final recommendations based on importance to advance the field of HaH.

Approval

This research was approved by the institutional review board of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Funding source

This work was supported by The John A. Hartford Foundation. Otherwise, the funder had no role in the study.

RESULTS

The link to the online survey was emailed to 434 attendees of the Congress. Two‐hundred forty completed the survey for a response rate of 55.3%.

Respondent characteristics

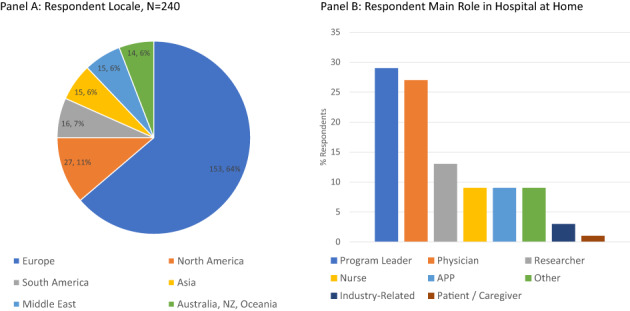

Characteristics of survey respondents are depicted in Figure 1. They came from around the world with a majority 153 (64%) from Europe and 27 (11%) North America. The most common roles were HaH program leaders (29%), HaH physicians (27%), and researchers (13%). The majority of programs treated more than 300 patients per year.

FIGURE 1.

Survey respondent characteristics

Most important specific research topic areas

The 5 specific topic areas deemed most important for HaH research were: use of technology and telemonitoring in HaH care (n = 98; 23% of respondents), selecting patients for HaH care (n = 93; 21%), defining the HaH model of care (n = 93; 21%), developing new applications for HaH care (n = 74; 17%), and medication management and safety in HaH care (n = 62; 14%).

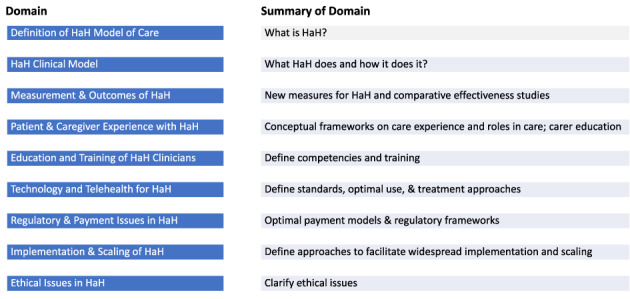

Defining research domains

After review of survey data, investigators categorized the potential research topic areas into 9 broad domains: 1) definition of the HaH model of care; 2) the HaH clinical model; 3) measurement and outcomes of HaH; 4) patient and caregiver experience with HaH; 5) education and training of HaH clinicians; 6) technology and telehealth for HaH; 7) regulatory and payment issues in HaH; 8) implementation and scaling of HaH; and 9) ethical issues in HaH.

For each domain, we provide a brief summary of the current state of knowledge/research in that domain and then a brief description of key areas for researchers to focus on in future work. See Table 1 and Figure 2.

TABLE 1.

Research agenda domains and key research areas or questions for hospital at home

| Domain | Key research areas or questions |

|---|---|

| Definition of the HaH model of care |

|

| The HaH clinical model |

|

| Measurement and outcomes of HaH |

|

| Patient and caregiver experience with HaH |

|

| Education and training of HaH clinicians |

|

| Technology and telehealth for HaH |

|

| Regulatory and payment issues in HaH |

|

|

Implementation and scaling of HaH |

|

|

Ethical issues in HaH |

|

FIGURE 2.

Hospital at home (HaH) research agenda domains and summary of domain‐specific research focus

Definition of the HaH model of care

It is critical to clearly define a health service delivery model. That is, “what is it?” The generally accepted definition of HaH is the delivery of acute hospital‐level care to patients at home. 1 , 18 , 19 It is an acute clinical service that takes all key services traditionally found in hospitals and delivers them to selected acutely ill people at home. It is episodic; comprehensively responsible for the episode; provides continuous care 24 h, 7 days; and includes medical, nursing, paramedical, therapy, laboratory, radiology, and pharmacy care. HaH is not: personal home care services, skilled home health care, home hospice, outpatient care, outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT), chronic care, day center or nursing home care, home‐based primary care, basic community nursing care, comprehensive geriatric assessment at home, or self‐administered care. However, controversy remains as to what fits into this general definition. 20 Areas for additional research include the development of an international consensus statement on the definition of HaH and the growing variety of clinical delivery models that claim HaH status and to define a standard nomenclature for HaH that is appropriate for patients, caregivers, clinicians, and regulators. The field will need to consider how the definition of HaH evolves as more care delivery services move to the community and patients' homes.

The HaH clinical model

Given a definition of what HaH is, does the deployed service fulfill the definition? This domain focuses on what the HaH model does and how it accomplishes it. While there are common elements among HaH models that fulfill its basic definition, there is variation in the HaH clinical model within and across countries. The range of conditions treated, level of acuity treated, and types of clinicians used to provide care across programs varies and may be influenced by the culture of the health system at national and local levels in how it defines clinical thresholds for hospitalization and how that influences payment and relevant regulatory issues, the types of clinical assets, supply chain, and logistic support available to programs. Must a HaH admission originate in the hospital emergency department or inpatient service to qualify for HaH? The field needs to develop, test, and define high‐quality and safe approaches to medication management and administration in the home, 21 clinical monitoring, clinical care pathways, staffing requirements, and care team composition and approaches to providing HaH care in rural areas. 22 More research is needed to define whether HaH should exist as a clinical unit of an acute care hospital, whether it can safely exist as a freestanding service not tied to a specific hospital, and on the development of emerging HaH models.

Measurement and outcomes of HaH

Multiple randomized controlled and observational trials of HaH have been conducted; nearly all have been of new or nascent programs, not mature ones. There are two meaningful controls for HaH interventions: traditional hospital inpatient care and alternative HaH service models. Research comparing HaH with standard inpatient care is common; research comparing different HaH service models is absent. In studies that compare HaH to standard inpatient care, outcomes have included those generally described for hospital inpatient care and those related to the specific condition under study, such as mortality, length of stay, 30‐day hospital readmission, patient and caregiver experience, quality of care, and cost. Certain important HaH‐specific outcomes, such as unplanned return to hospital or “escalations” do not have an equivalent in the traditional hospital. 23 As HaH evolves, comparative effectiveness studies of different HaH models and the associations between different program inputs for HaH models focused on similar patient populations, for example, in‐person physician versus remote virtual physician care, and outcomes should be conducted. Other opportunities include defining the appropriate level of HaH program maturity suitable for study and best study designs for HaH evaluation. Validated measures unique to HaH should be clearly defined and tested. This may include novel quality indicators such as care escalations, days at home, 24 and others.

Patient and caregiver experience with HaH

Patient and caregiver experience has been conceptualized as the patients' and caregivers' experiences with care and as feedback about those experiences. 25 , 26 HaH studies frequently operationalize care experience as satisfaction with care. Many HaH studies have used or adapted traditional acute hospital experience tools, for example, HCAHPS, 27 Picker Experience Score, or Press‐Ganey hospital survey. 28 Care experience in HaH has also examined caregiver strain or burden associated with HaH care provision. Overall, the studies show better patient and caregiver experience and similar or less caregiver stress or strain in HaH. 8 , 9 , 13 , 15 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 Fewer studies have examined why patients accept or decline HaH care. 33 , 34 A HaH‐specific care experience conceptual framework should be developed, which could inform development of a HaH‐specific care experience measurement tool. The characteristics of patients and caregivers associated with HaH care experience and whether and how experience varies with the specific type HaH services provided should be clarified. We need to better understand how to balance the needs of patients and caregivers in HaH care, including clarifying the role of family and caregivers and whether they should be enlisted as functional HaH staff or not, and if so, determine which tasks are appropriate and how can they be trained and supported to perform those duties.

Education and training of HaH clinicians

In providing hospital‐level care at home, HaH sits at a nexus that requires unique approaches to the education and training of all clinicians who provide HaH care. The current generation of HaH clinicians has been largely self‐taught, borrowing from the fields of hospital and home care medicine and content largely from internal and family medicine and its subspecialties. Most HaH physicians have come from the ranks of internal medicine, family medicine, and geriatric medicine, with growing interest among hospitalists, 35 oncologists, 36 and surgeons. 37 Approaches to education and training of clinicians will need to be developed, including delineated competencies for those clinicians. It is not known which phenotypes of physicians, advance practice providers, and nurses are best suited to provide HaH care. Another opportunity is to develop approaches to train mid‐career clinicians to provide HaH care. Additional areas to clarify include determining appropriate training modalities and curricula for HaH clinicians, how subspecialist physicians can be enlisted to provide HaH care, and the best approaches to train the next generation of HaH clinicians. Should HaH medicine and associated professional disciplines develop into their own subspecialties? 38

Technology and telehealth for HaH

Most studies of HaH were conducted in an era when telehealth, portable technology, point of care testing, and remote patient monitoring were nonexistent or in their infancy. HaH programs are beginning to incorporate technology to advance their capabilities and improve the safety and quality of care provided, expand the acuity and range of conditions they care for, and better leverage their workforce. 39 , 40 More research is needed to define standards for use of technology in HaH, gain a better understanding of the barriers to effective technology use, optimal remote monitoring and treatment approaches, and define the appropriate balance between high‐touch and high‐technology care. Studies should be conducted to understand how to maintain cybersecurity and optimally integrate technology into HaH clinical workflows and how to best match technology to the needs of patients. It is important to develop artificial intelligence approaches that leverage data obtained through remote patient monitoring and electronic health records and produce actionable clinical data to support and enhance safe, high‐quality HaH care and enable caring for higher acuity patients in the home. 41 Comparative effectiveness studies of HaH‐appropriate technologies should be conducted.

Regulatory and payment issues in HaH

Currently, different regulatory frameworks and payment models for HaH exist in different countries or remain undefined. In some countries, HaH is defined, paid for, and regulated as hospital care, but not in all. There has been a dearth of research on HaH regulatory and payment issues. While these issues are necessarily linked to the underlying health care system at the country level, there are significant opportunities for research in this area. Future directions include determining how to best structure HaH payment and regulate and accredit HaH clinical units to ensure high‐quality care is delivered. Research to determine the most appropriate regulatory framework for HaH to maximize the effectiveness of the model while ensuring safety and high‐quality care delivery should be conduction. Further, how should HaH be accredited and in the context of safety, should there be entry requirements to reduce the risk of of the provision of substandard HaH care?

Implementation and scaling of HaH

With the exception of France, Spain, and Australia, 42 HaH has not been implemented at a regional or national scale. Many aspects of implementation and scaling of HaH have not been addressed in research. 43 , 44 , 45 Broad topics for inquiry include determining major barriers and facilitators to scaling HaH and how those can be overcome, the development of decision rubrics to aid health systems in their decision to implement HaH, the optimal organizational structures to promote scaling, and how to create optimal logistics and supply chains to support more rapid adoption of HaH by health systems. Another opportunity is to conduct cross‐national studies to help payers and regulators understand how their strategies regarding HaH affect its implementation.

Ethical issues in HaH

The scaling of HaH, despite its potential benefits, may be associated with a number of moral, social, and ethical issues. Moving the site of acute care into the home poses unique ethical challenges and there is a dearth of literature in this area. 46 There is a need to broadly identify a code of ethics for HaH care delivery and determine whether to employ a principles or a values‐based approach to developing such a code. In addition, investigators in this area may focus on clarifying how ethical constructs such as autonomy and patient consent may evolve in the context of HaH care, as well as the the ethics for clinicians in being a “professional guest” in a patient's home, and whether patients need a different bill of rights when under HaH care.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to describe a research agenda for HaH. With input from a broad range of international stakeholders, we report specific topic areas deemed most important by stakeholders for HaH research and developed a set of research domains and questions for the field to address in future work. The highest prioritized specific research topics by stakeholders were focused on clinical aspects of HaH care delivery, including the use of technology, defining the HaH model, and selecting patients for HaH care.

The research domains cover a broad array of issues and highlight multiple potential research foci. If adequately addressed by researchers in the coming years, the field of HaH could advance substantially. In a future state, the HaH model will be better defined in a manner to facilitate research and the development of appropriate payment and regulatory frameworks. HaH will have established outcomes and quality indicators to guide the field, assess quality, and engage in comparative effectiveness research. The roles of caregivers will be better defined, assessed, and managed. HaH will be staffed by clinicians whose professional education and training provided them with the knowledge, skills, and mindsets to provide high‐quality acute care at home leveraging technology into clinical workflow to care for high‐acuity patients. This advancing body of research will support the broad implementation of HaH. However, we note that there are potential barriers to moving forward with the proposed research agenda. Aside from potential lack of interest among funders, the incentives to perform rigorous research may diminish if HaH scales rapidly in response to new payment mechanisms.

This study has important limitations. The literature reviews performed to inform the development of the research agenda were not systematic ones. We therefore may have omitted salient studies. The grounded theory approach used to identify research domains may have been limited by the unconscious application of prior extensive knowledge of the investigators to the analysis process. Further, we did not use a formal process to prioritize the research areas or questions. The survey that supported the development of the research agenda domains was conducted in 2019 and did not describe the number of years of experience in HaH or the race/ethnicity of respondents. This work predated the COVID‐19 pandemic and the widespread recognition of the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion issues in health care. Because these items were not included in the survey, we did not include them in the formal results; however, clarifying and addressing issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion in HaH research are paramount to bring the model to scale. Multiple research questions in this sphere remain unanswered. For instance, does HaH care privilege one group over another? Do different groups experience different outcomes under HaH care? If so, how can this be ameliorated? How can HaH programs adapt to ensure that socially and economically disadvantaged patients have access to and benefit from HaH care? The COVID‐19 pandemic has been an important factor in the increased interest in HaH as health systems have used HaH as a tactic to create inpatient capacity. 6 , 47 , 48 COVID‐19 was a major focus of the recent 2021 HaH World Congress 49 and will be a continued focus for HaH research. There has been little or no research and commentary on issues of related to diversity, equity, and inclusion associated with HaH care provision and multiple research questions in this sphere are unanswered. Finally, we surveyed persons at a single Congress, which may limit the representativeness and generalizability of our findings.

The study also has several strengths. The development of this research agenda was data‐driven, based on input from a broad range of HaH stakeholders drawn from around the world, and was not based solely on expert opinion. The focused narrative literature reviews conducted for each research domain provide a high‐level view of the current state of the field.

There is an urgent need to ensure that HaH continues to develop in a manner that benefits all relevant HaH stakeholders. By focusing research in these identified domains, investigators and entities that sponsor research can make important advances in HaH development and assure that widespread implementation and scaling of HaH is guided by data and science.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Leff serves as a clinical advisor to Medically Home, Dispatch Health, and the Chartis Group. He serves as a volunteer member of the Humana Multidisciplinary Advisory Board. In the early 2000s, Dr. Leff developed FoF technical assistance tools that were licensed by Johns Hopkins to several entities and, as a result of these license agreements, both the University and its inventors received royalty income. Dr. Leff's arrangements and relationships have been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflicts of interest policy. Drs. Leff and Montalto serve as consultants to the Kenes Group as members of the planning committee of the World Hospital at Home Congress. Drs. DeCherrie, Leff, and Levine lead the HoH Users group, which focuses on HoH technical assistance and is supported by grants from the John A. Hartford Foundation. Dr. Levine has a principal investigator‐initiated study and co‐development agreement with Biofourmis and a principal investigator‐initiated study with IBM, separate from the present work. Dr. DeCherrie was a full‐time employee of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai at the time the research was conducted and the manuscript was submitted to JAGS. The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai has an ownership interest in a joint venture with Contessa Health, a venture that manages acute care services provided to patients in their homes through prospective bundled payment arrangements. Dr. DeCherrie had no personal financial interest in the joint venture. At the time the manuscript revision was submitted, Dr. DeCherrie was a full‐time employee of Medically Home.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors contributed to the Concept and design, Acquisition of subjects and/or data, Analysis and interpretation of data and Preparation of manuscript.

SPONSOR'S ROLE

The funder had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, and preparation of article.

Supporting information

Data S1. Survey to identify research agenda for hospital at home.

Leff B, DeCherrie LV, Montalto M, Levine DM. A research agenda for hospital at home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(4):1060‐1069. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17715

Funding informationDrs. Leff, DeCherrie, and Levine were supported by a grant from The John A. Hartford Foundation.

An abstract based on this article was presented at the American Academy of Home Care Medicine annual meeting and at the Hospital at Home Users Group annual meeting, both in October 2021.

REFERENCES

- 1. Leff B, Montalto M. Home hospital‐toward a tighter definition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(12):2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jaklevic MC. Pandemic boosts an old idea‐bringing acute care to the patient. JAMA. 2021;325(17):1706‐1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hostetter M, Klein S. Transforming care – has the time finally come for hospital at home. The Commonwealth Fund. 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/jul/has-time-finally-come-hospital-home on July, 2021.

- 4. Nundy S, Patel KK. Hospital‐at‐home to support COVID‐19 surge—time to bring down the walls? JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(5):e200504. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mayo Clinic and Kaiser Permanente Invest $100 Million in ‘Hospital Care at Home’ Venture. Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2021/05/13/mayo-and-kaiser-invest-100-million-in-hospital-care-at-home-venture/?sh=6bbe575e6063 on July 14, 2021.

- 6. Clarke DV, Newsam J, Olson DP, Adams D, Wolfe AJ, Fleischer LA. Acute Hospital Care at Home: the CMS waiver experience. NEJM Catalyst https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.21.0338. Last accessed December 11, 2021.

- 7. Levine DM, DeCherrie LV, Siu AL, Leff B. Early uptake of the acute Hospital Care at Home Waiver. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1772‐1774. doi: 10.7326/M21-2516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caplan GA, Sulaiman NS, Mangin DA, Aimonino Ricauda N, Wilson AD, Barclay L. A meta‐analysis of "hospital in the home". Med J Aust. 2012;197(9):512‐519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shepperd S, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9(9):CD007491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qaddoura A, Yazdan‐Ashoori P, Kabali C, et al. Efficacy of Hospital at Home in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0129282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jeppesen E, Brurberg KG, Vist GE, et al. Hospital at home for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD003573. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003573.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levine DM, Pian J, Mahendrakumar K, Patel A, Saenz A, Schnipper JL. Hospital‐level Care at Home for acutely ill adults: a qualitative evaluation of a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:1965‐1973. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06416-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital‐level Care at Home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):77‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leong MQ, Lim CW, Lai YF. Comparison of hospital‐at‐home models: a systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e043285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gonçalves‐Bradley DC, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Early discharge hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Hospital at home: feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital‐level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(11):798‐808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chapman AL, Hadfield M, Chapman CJ. Qualitative research in healthcare: an introduction to grounded theory using thematic analysis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2015;45(3):201‐205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Montalto M, Leff BA. Hospital in the home: a lot's in a name. Med J Aust. 2012;197(9):479‐480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leff B. Defining and disseminating the hospital‐at‐home model. CMAJ. 2009;180(2):156‐157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levine DM, Montalto M, Leff B. Is comprehensive geriatric assessment admission avoidance Hospital at Home an alternative to hospital admission for older persons? Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(11):1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mann E, Zepeda O, Soones T, et al. Adverse drug events and medication problems in "Hospital at Home" patients. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2018;37(3):177‐186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levine DM, Desai MP, Ross J, Como N, Anne Gill E. Rural perceptions of acute care at home: a qualitative analysis. J Rural Health. 2021. Mar;37(2):353‐361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chou SH, McWilliams A, Murphy S, et al. Factors associated with risk for care escalation among patients with COVID‐19 receiving home‐based hospital care. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1188‐1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burke LG, Orav EJ, Zheng J, et al. Healthy days at home: a novel population‐based outcome measure. Healthc (Amst). 2020;8(1):100378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ahmed F, Burt J, Roland M. Measuring patient experience: concepts and methods. Patient. 2014;7(3):235‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beattie M, Murphy DJ, Atherton I, Lauder W. Instruments to measure patient experience of healthcare quality in hospitals: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2015;23(4):97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. HCAHPS : Patients' Perspectives of Care Survey. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalHCAHPS on May 25, 2021.

- 28. Cryer L, Shannon SB, Van Amsterdam M, et al. Costs for 'hospital at home' patients were 19 percent lower, with equal or better outcomes compared to similar inpatients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012. Jun;31(6):1237‐1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Utens CM, van Schayck OC, Goossens LM, et al. Informal caregiver strain, preference and satisfaction in hospital‐at‐home and usual hospital care for COPD exacerbations: results of a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014. Aug;51(8):1093‐1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gunnell D, Coast J, Richards SH, Peters TJ, Pounsford JC, Darlow MA. How great a burden does early discharge to hospital‐at‐home impose on carers? Randomized Controlled Trial Age Ageing. 2000;29(2):137‐142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Comparison of stress experienced by family members of patients treated in hospital at home with that of those receiving traditional acute hospital care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008. Jan;56(1):117‐123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leff B, Burton L, Mader S, et al. Satisfaction with hospital at home care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006. Sep;54(9):1355‐1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Levine DM, Paz M, Burke K, Schnipper JL. Predictors and reasons why patients decline to participate in home hospital: a mixed methods analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;37:327‐331. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06833-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saenger P, Federman AD, DeCherrie LV, et al. Choosing inpatient vs home treatment: why patients accept or decline hospital at home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. Jul;68(7):1579‐1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Danielsson P, Leff B. Hospital at home and emergence of the home hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(6):382‐384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Handley NR, Bekelman JE. The oncology hospital at home. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(6):448‐452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Safavi KC, Ricciardi R, Heng M, et al. A different kind of perioperative surgical home: hospital at home after surgery. Ann Surg. 2020. Feb;271(2):227‐229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sociedad Espanola de hospitalizatcion a domcilio. https://www.sehad.org/galicia-crea-la-categoria-profesional-de-medico-de-hospitalizacion-a-domicilio/ on July 14, 2021

- 39. Tibaldi V, Aimonino Ricauda N, Rocco M, Bertone P, Fanton G, Isaia G. L'innovazione tecnologica e l'ospedalizzazione a domicilio [Technological advances and hospital‐at‐home care]. Recenti Prog Med. 2013;104(5):181‐188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Summerfelt WT, Sulo S, Robinson A, Chess D, Catanzano K. Scalable hospital at home with virtual physician visits: pilot study. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(10):675‐684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bates DW, Levine D, Syrowatka A, et al. The potential of artificial intelligence to improve patient safety: a scoping review. Npj digit Med. 2021;4:54. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00423-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Montalto M. The 500‐bed hospital that isn't there: the Victorian Department of Health review of the hospital in the home program. Med J Aust. 2010;193(10):598‐601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Siu AL, Zimbroff RM, Federman AD, et al. The effect of adapting Hospital at Home to facilitate implementation and sustainment on program drift or voltage drop. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brody AA, Arbaje AI, DeCherrie LV, et al. Starting up a hospital at home program: facilitators and barriers to implementation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019. Mar;67(3):588‐595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. DeCherrie LV, Wajnberg A, Soones T, et al. Hospital at home‐plus: a platform of facility‐based care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019. Mar;67(3):596‐602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Arras JD, ed. Bringing the hospital home. Ethical and social implications of high‐tech home care. Johns Hopkins University Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Heller DJ, Ornstein KA, DeCherrie LV, et al. Adapting a hospital‐at‐home care model to respond to New York City's COVID‐19 crisis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. Sep;68(9):1915‐1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Levine DM, Mitchell H, Rosario N, et al. Acute Care at Home during the COVID‐19 pandemic surge in Boston. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3644‐3646. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07052-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. World Hospital at Home Congress 2021. Program at a Glance. https://whahckenescom/wp-content/uploads/sites/121/2021/04/WHAHC-21-Program-at-a-Glancepdf on July 14, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Survey to identify research agenda for hospital at home.