Abstract

Ordered mesoporous CuNiCo oxides were prepared via nanocasting with varied Cu/Ni ratio to establish its impact on the electrochemical performance of the catalysts. Physicochemical properties were determined along with the electrocatalytic activities toward oxygen evolution/reduction reactions (OER/ORR). Combining Cu, Ni, and Co allowed creating active and stable bifunctional electrocatalysts. CuNiCo oxide (Cu/Ni≈1 : 4) exhibited the highest current density of 411 mA cm−2 at 1.7 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) and required the lowest overpotential of 312 mV to reach 10 mA cm−2 in 1 m KOH after 200 cyclic voltammograms. OER measurements were also conducted in the purified 1 m KOH, where CuNiCo oxide (Cu/Ni≈1 : 4) also outperformed NiCo oxide and showed excellent chemical and catalytic stability. For ORR, Cu/Ni incorporation provided higher current density, better kinetics, and facilitated the 4e− pathway of the oxygen reduction reaction. The tests in Li−O2 cells highlighted that CuNiCo oxide can effectively promote ORR and OER at a lower overpotential.

Keywords: electrocatalysts, mesoporous materials, non-noble metals, oxygen evolution reaction, oxygen reduction reaction

Mix and match: Combining Cu, Ni, and Co into mesoporous mixed oxide nanocasts leads to active and stable bifunctional electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution and reduction reactions (OER and ORR). Small amount of Cu plays a substantial role in improving the catalyst conductivity and facilitating Fe−Ni interactions, which is beneficial for water oxidation. In Li−O2 cells, both charge and discharge reactions occur at lower overpotentials compared to cells with carbon cathodes, and LiOH is a main discharge product.

Introduction

The constantly increasing energy demands and greater use of fossil fuels, leading to rising CO2 emissions followed by global warming, have led to significant attention to renewable energy technologies, such as metal‐air batteries and electrochemical water splitting. [1] Nevertheless, their global‐scale application is impeded by the sluggish electrochemical reactions, including oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER). Although Ru‐ and Pt‐based catalysts are active towards OER and ORR, respectively, their high cost, scarcity, and poor stability limit their wider implementation. [2] Therefore, the use of noble‐metal‐free materials is increasing in relevance. [3] In particular, state‐of‐the‐art non‐noble metal electrocatalysts for OER/ORR are Co‐ and/or Ni‐based oxides. Spinel cobalt oxide (Co2+Co3+ 2O4), with edge‐sharing CoO6 octahedra (Co3+ centered) interconnected by corner‐sharing CoO4 tetrahedra (Co2+ centered), can accommodate vacancies and lattice defects that potentially act as active sites to promote electrochemical reactions. [4] Experimental works coupled with density functional theory (DFT) calculations have shown that Co3O4,[ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ] Cu‐doped Co oxides,[ 11 , 12 , 13 ] and bimetallic NiCo2O4[ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ] are highly active and stable catalysts towards OER and/or ORR in alkaline media, emphasizing their potential use in the electrolyzers and fuel cells. Additionally, some published studies demonstrate that these materials can be active in other electrolytes, and show their potential application in the aprotic Li−O2 batteries.[ 21 , 22 , 23 ] Recent research by Markovic and co‐workers showed that combining Cu and Ni hydr(oxy)oxides creates a better host for the adsorption of Fe impurities from the alkaline electrolyte during the OER and increases the activity of the catalyst. [24] Moreover, the interaction of Cu and Ni species decreases the dissolution rate of Cu in KOH solution resulting in higher chemical and catalytic stability. We can assume that the addition of Cu/Ni in Co‐based oxide structure would ensure a more sustainable material development as well as improved electrical conductivity of the material to increase the electron supply to reaction sites. However, even though such Cu/Ni synergistic effect[ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ] has attracted great interest in catalysis and doping of Co3O4 is known to increase the activity of the catalysts, the electrocatalytic properties of trimetallic CuNiCo oxides have not been thoroughly established. Only a limited number of studies include the examination of the electrocatalytic performance of CuNiCo oxides and the role of the Cu/Ni ratio in the systems.[ 12 , 29 , 33 , 34 ] Furthermore, hardly any work on ordered mesoporous mixed CuNiCo oxides can be found. In comparison to bulk materials, 3D‐ordered mesoporous oxides with high specific surface area (SSA) have demonstrated better catalytic activity towards OER and ORR.[ 4 , 10 , 20 ] The ordered mesoporous materials can be implemented as a toolbox to study structure–activity correlations of well‐defined catalysts for water electrolysis. Hence, in this work, we couple the benefits of 3D ordered mesoporous nanocast structures with the simultaneous substitution of Cu/Ni in the Co‐based oxides with spinel structure to produce improved electrocatalysts for OER/ORR. Moreover, to establish the crucial role of Cu in the electrochemical performance of the oxides in alkaline media, a detailed study of the physicochemical and electrocatalytic properties using various techniques was carried out. Additional electrochemical tests in aprotic Li−O2 cells were performed and cycled electrodes subjected to post‐mortem analysis to confirm the potential use in post‐lithium‐ion batteries. The outcome of the study clearly indicated the advantage of trimetallic system towards the development of more effective bifunctional ORR and OER electrocatalysts in alkaline media and aprotic Li−O2 cells.

Results and Discussion

Physicochemical properties

The nanocasting synthesis approach[ 31 , 35 , 36 , 37 ] was applied to synthesize 3D‐ordered mesoporous oxides by using ordered mesoporous silica as the hard template. Here, we used a KIT‐6 silica powder aged at 100 °C with Brunauer‐Emmett‐Teller (BET) surface area of 798 m2 g−1, total pore volume of 1.3 cm3 g−1, and pore size of 8.8 nm (Table S1 and Figure S1a,b in the Supporting Information). As seen from Figure S1c, the KIT‐6 silica powder exhibits the expected cubic Ia3d pore symmetry with the characteristic reflections in the low‐angle X‐ray diffraction (XRD) pattern. Specific surface area (SSA) and pore volume influence the electrocatalytic performance of the replicated oxides.[ 8 , 10 ] To exclude these factors and establish the role of copper (at different Cu/Ni ratios), all the obtained catalysts need to exhibit comparable porosity. Figure S2 shows N2 physisorption isotherms and pore size distribution (PSD) of the obtained metal oxides. Table S1 presents the data on SSA, pore size, and total pore volume. The porosity properties established from the physisorption analysis are in agreement with previously published reports.[ 8 , 10 ] The materials exhibit type IVa isotherms (Figure S2a), typical for such mesoporous replicas, with hysteresis loops that might be described as hybrid loops of types H1 and H3. [38] The evaluation of the physisorption data has indicated no blockage of the pores with a size below 4 nm for all the samples. Non‐local density functional theory (NLDFT) pore size analysis demonstrates a relatively narrow PSD where most of the pores are around 5 nm in diameter for each sample (Figure S2b). However, the combination of three metals in the oxide leads to a wider PSD as compared to the bimetallic and single metal oxides. This can be explained by the formation of multiple phases during the calcination process due to the presence of various metal nitrate precursors. Depending on the metal salt and its decomposition temperature, the precursors might migrate and convert faster or slower and mix (non)uniformly within the pores of the template. Consequently, inhomogeneous crystal growth might distort the porous structure or replicate the template only partially resulting in the decrease of mesoporous order.

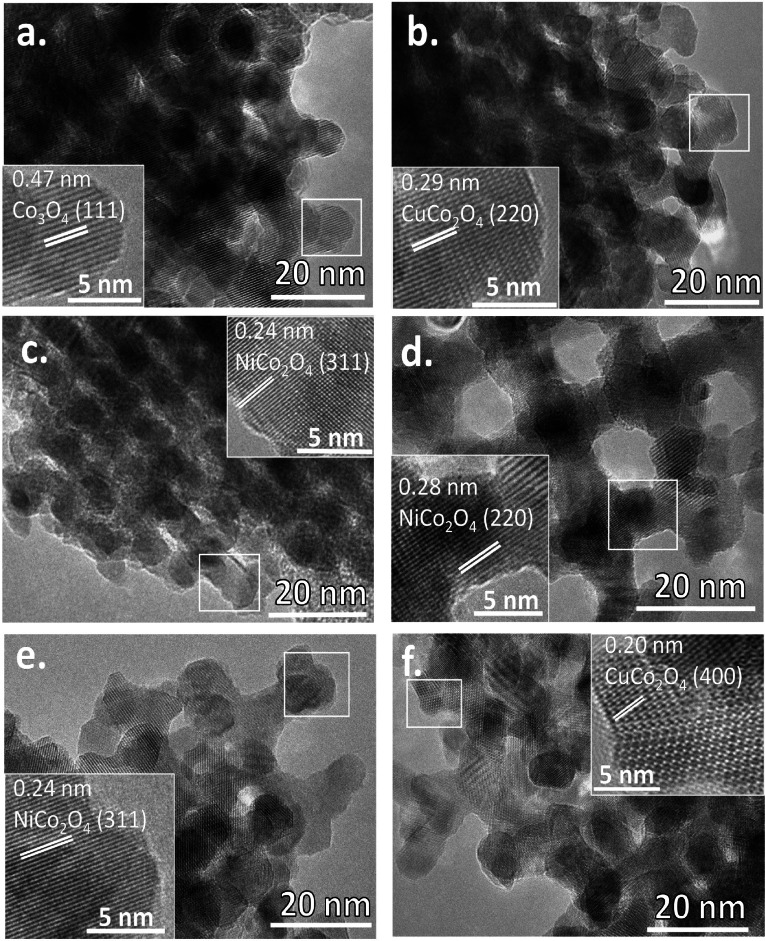

To get additional knowledge about the mesoporous structure of the replicated mixed metal oxides, low‐angle powder XRD analysis was performed. As seen from Figure S3, all the obtained oxides demonstrate the clear presence of a main basal reflection, which could be assigned to the 211 reflection of the body‐centered cubic Ia3d space group reflecting the original 3D mesostructure of the KIT‐6 template. [39] The second reflection, the 220 peak, is not so well‐resolved for Ni‐rich oxides, such as NiCo, CuNiCo‐2‐8, and CuNiCo‐5‐5, due to smaller ordered mesoporous domains. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (Figure 1 and Figure S4) confirm that all the mesoporous oxides possess excellent mesoscopic order. Typically, high‐quality nanocast replicas from KIT‐6 silica are almost spherically shaped particles of different sizes, which is seen in the case of Co3O4, CuCo, and CuNiCo‐8‐2. Although Ni‐rich samples do not demonstrate large spherical particles but smaller particle domains, the nanocast materials are still well ordered, which correlates with the results of low‐angle XRD and N2 physisorption. In addition, high‐resolution HRTEM images (Figure 1, inset) show that the materials’ walls are highly crystalline without the presence of an amorphous layer of silica template residue covering the surface.

Figure 1.

HRTEM micrographs of nanocast (a) Co3O4, (b) CuCo, (c) NiCo, (d) CuNiCo‐2‐8, CuNiCo‐5‐5 (e), and (f) CuNiCo‐8‐2. Inset shows the lattice fringe measurement of each sample.

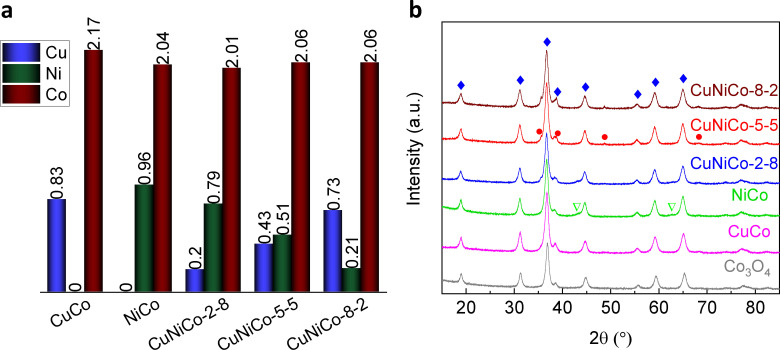

The synthesis of ordered mesoporous quaternary mixed metal oxides with desired elemental and phase composition is a challenge. To establish the role of Cu and Ni in the electrocatalytic behavior of the mixed metal oxides, it is important to determine the exact elemental composition. For this purpose, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP‐MS) analysis was applied for all the materials except pure cobalt oxide. Figure 2a demonstrates the experimental stoichiometric proportions of the oxides. The Ni/Co ratios agree with the nominal ones. However, the amount of Cu is slightly lower than expected for Cu‐rich oxides (CuCo, CuNiCo‐5‐5, and CuNiCo‐8‐2), presumably due to the dissolution of CuO during the silica‐removal in 2 m NaOH solution. [40] The ICP‐MS data showed that after the 2 m NaOH treatment of the metal oxide/SiO2 nanocast composite, the Cu/Si ratio in the removed supernatant was around 1 : 17. Additionally, bulk energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectroscopy (EDX) was conducted to analyze the elemental composition. Table S2 displays the data and calculated Cu/Ni/Co ratios, which are mostly equivalent to the ratios obtained by ICP‐MS. Furthermore, elemental distribution in the quaternary oxides was probed using EDX elemental mapping. According to these results, the distribution of the elements remains uniform regardless of the oxide composition (Figures S5–S9).

Figure 2.

(a) Atomic ratio of the metals obtained by ICP‐MS and (b) wide‐angle powder XRD patterns of the nanocast metal oxides. Blue diamonds represent the spinel (Cu, Ni)xCo3‐xO4 phase (ICSD‐24211 for NiCo2O4, ICSD‐150807 for CuCo2O4, and ICSD‐24210 for Co3O4), red circles represent CuO (ICSD‐43179), and green inverted triangles represent NiO (ICSD‐92132).

Figure 2b and S10 illustrate powder XRD patterns of the nanocast metal oxides and the refinement of the structures, respectively. A model of the spinel structure of (Cu,Ni) x Co3‐x O4 obtained from the refinement is presented in Figure S11. As shown, all the mixed metal oxides contain at least two phases, where the spinel phase is the main one and the single metal oxide phases (NiO and CuO) are present in small amounts. Although these impurities were not discussed in the previously published works on CuNiCo oxides,[ 41 , 42 , 43 ] the XRD patterns shown here are similar to the ones reported in those studies, with the same additional weaker diffraction peaks that we assigned to NiO or CuO.

X‐ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was then carried out to elucidate the electronic structure and oxidation state in near‐surface region (Figure S12). The obtained Ni 2p spectra seem to be a combination of Ni(OH)2 and NiO spectra and consist of two regions assigned to Ni 2p3/2 (≈855 eV with a shake‐up peak at ≈861 eV) and Ni 2p1/2 (≈872 eV with a shake‐up peak at ≈880 eV). On the other hand, the splitting of the peak at around 855 eV was assigned by several authors to the presence of Ni3+ cations on the surface of the material, which can be associated to a high amount of defect sites upon the substitution of Co by other cations in the spinel structure.[ 44 , 45 ] From the Co 2p spectra, both Co2+ and Co3+ cations were found on the surface of the materials. [46] These results correlate with the ones obtained in the previously published studies.[ 16 , 47 ] Cu 2p spectra reveal the co‐existence of CuO and Cu2O, where Cu2+ and Cu1+ are present. However, it is nearly impossible to make any reliable conclusion here due to the strong photoreduction of CuO to Cu2O in XPS. [48] The intensity of the abovementioned Ni 2p and Cu 2p spectra decreases with lower amount of the elements in the material, as expected. O 1s spectra of all the samples look similar, and consist of several peaks, which are assigned to M−O bonds (O1), OH groups (O2), and adsorbed H2O (O3).

OER performance

OER performance of the materials was tested according to the protocols previously published.[ 16 , 49 ] Initially, OER activity was investigated by measuring linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) before and after 200 cyclic voltammetry (CV) cycles in an Ar‐saturated non‐purified 1 m KOH electrolyte solution. Figure 3a,b and Figure S13 display the LSV curves of all nanocast electrocatalysts before and after the 200 CV cycles in 1 m KOH. In the initial LSV scan, Cu‐rich oxides outperform the other catalysts: CuCo oxide demonstrates the lowest overpotential of 347 mV at 10 mA cm−2 and CuNiCo‐8‐2 has the highest current density of 221 mA cm−2 at 1.7 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE). Cycling the catalysts over 200 CVs decreases the activity of these Cu‐rich oxides (Figure S13b, f). On the other hand, the activity of the Ni‐rich catalysts (NiCo, CuNiCo‐2‐8, CuNiCo‐5‐5) increased remarkably after 200 CV due to the iron uptake from non‐purified KOH solution by the nickel hydr(oxy)oxides formed on the surface of the catalysts during OER and the ensuing formation of highly active Ni−(Fe)−OOH species on the catalyst surface.[ 24 , 50 , 51 ] There is a clear trend in the change of the LSV curves after 200 CVs: the reaction starts at lower potentials for Ni‐rich oxides, whereas high amounts of Cu seem to delay the reaction. However, small amounts of Cu in CuNiCo‐2‐8 and CuNiCo‐5‐5 result in the highest current density of 412 and 390 mA cm−2 at 1.7 V vs. RHE and low overpotential of 312 and 334 mV at 10 mA cm−2, respectively (Figure S14, Table S3). The high activity might originate from the altered electronic structure of the spinel oxide lattice due to the Ni and Cu incorporation, resulting in synergistic effect and formation of highly active intermediates.[ 52 , 53 ] Ni and Cu have higher Fe adsorption energies than Co, as was indicated by Markovic and co‐workers, [24] and lower M−O binding energies, as calculated by Bothra and Pati. [54] The later work also underlines that in the case of Ni‐substituted cobalt oxide, Ni sites are considered as the active sites, while in the case of Cu‐substituted material, the adsorption of OH* occurs on the Co‐4 f active sites (four‐fold coordinated Co ions), and not on Cu. In our case, a combination of substituents might provide various types of active sites. Moreover, the activity of the partially substituted Co oxide for OER strongly depends on the concentration of the substituent. This agrees with our observation that despite the lower amount of Ni in CuNiCo‐2‐8 and −5‐5, these catalysts outperform NiCo oxide, suggesting a positive effect of the incorporation of small amount of Cu on the Ni−Fe interactions.

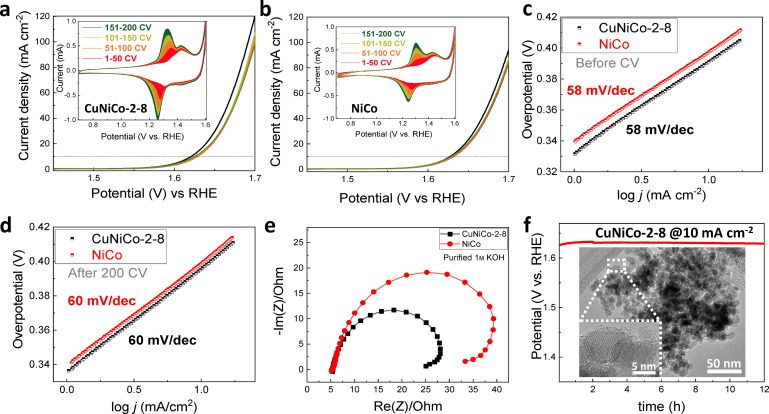

Figure 3.

OER screening of nanocast metal oxides. LSV curves (a) before and (b) after 200 CVs. Tafel slopes (c) before and (d) after 200 CVs. (e) Nyquist plots (closer look in the inset) after 200 CVs. (f) Capacitive current difference at 1.05 V (vs. RHE) against scan rates after 200 CVs.

Cyclic voltammograms were then analyzed to investigate the alteration on the catalyst's surface upon applied potential bias. Three redox coupled peaks obtained from CV measurements (Figure S15) in the pre‐catalytic region might be assigned to the redox processes of Co2+⇄Co3+ (A1‐C1), Co3+⇄Co4+ (A2‐C2), and Ni2+⇄Ni3+ (A3–C3), and further formation of Co4+ and Ni3+−(O)OH active species.[ 3 , 55 ] The position and intensity of the Co and Ni redox peaks are strongly influenced by the surface reactivity of the material, which is affected by the strong electronic interactions between the different metals.[ 44 , 53 , 56 ] Figure S16 demonstrates the trends in the position of the A2 and A3 oxidation peaks depending on the amounts of Ni and/or Cu after 200 CV cycles. In the case of Co3+→Co4+, the addition of Cu or Ni slightly shifts the position of the peak to lower potential. The biggest shift is observed for trimetallic Cu−Ni−Co oxides, where lower amounts of Cu or higher amounts of Ni result in lower potential. No obvious difference in the intensity of the peak for Cu‐rich oxides is registered, suggesting similar level of oxidation of Co3+ species and the formation of Co‐based intermediates. However, it is difficult to make a conclusion about the change in the magnitude or the position this peak with number of CV cycles for Ni‐rich materials due to the overlap of Ni and Co oxidation peaks. Change in both the position and the intensity of the Ni oxidation peak occurs for all the Ni‐containing oxides (Figure S16). There is an evident increase in the intensity of the A3–C3 redox peaks correlating with the amount of Ni in CuNiCo oxides over the number of CV cycle. It indicates that the oxidation of Ni2+→ Ni3+ is more pronounced and the Ni3+−(O)OH active species layer becomes more dominant over the increase of CV cycles. [1] The most active material CuNiCo‐2‐8 exhibits the most intense Ni oxidation peak, which occurs at the highest potential (1.36 V vs. RHE). Higher magnitude of the peak indicates a higher number of Ni2+ is being oxidized into Ni3+ on the surface, which emphasizes the difference between NiCo and CuNiCo‐2‐8. Although NiCo has higher amount of Ni, it seems that Cu−Ni interactions in CuNiCo‐2‐8 oxide provide more electrochemically active surface Ni species as compared to NiCo oxide. [16] Moreover, it was shown by several groups that the position of the Ni redox peak is affected by the Fe uptake from the electrolyte.[ 1 , 57 ] It seems that the shift of the Ni redox peak to more anodic potential in the pre‐catalytic region points out to a more active OER catalyst. Some research groups hypothesize that this anodic shift reflects the weaker OH binding in the Ni3+−(O)OH intermediates, which results in less stable Ni−OOH intermediates, and promoted migration of active species.[ 44 , 56 ] This assumption supports the volcano trend in the overpotential (Figure S14) as a function of the Cu amount observed in present work. However, such trend might also be attributed to the change of the resistance and formation of more active intermediate species on the surface of the metal oxides, which is caused by Fe−Cu/Ni interactions.[ 12 , 58 ]

The Tafel plots extracted from the LSV curves before and after 200 CVs are shown in Figure 3c,d and the values are stated in Table S3. The initial Tafel slope values are within the range of 50–56 mV dec−1 for all the catalysts, except CuCo (71 mV dec−1) implying slower kinetics of the reaction catalyzed by this oxide. After 200 CVs, Co3O4 maintained its Tafel slope value, indicating no change in OER mechanism upon stabilization. In contrary, the Tafel slope values decrease to 55 mV dec−1 for Cu‐rich materials and 37–40 mV dec−1 for Ni‐rich materials, confirming the improved kinetics of OER on the surface of these oxides upon adsorption of Fe cations from the electrolyte. [59] It is important to highlight that trimetallic CuNiCo‐2‐8 and CuNiCo‐5‐5 have the lowest Tafel slopes, although the amount of Ni in these oxides is lower compared to bimetallic NiCo oxide. This explains the highest current densities observed for these two mixed oxides (Table S3), confirming that Cu−Ni interactions in the cobalt oxide spinel lattice provide a better host for the Fe‐adsorption and activation of the catalyst. Moreover, such behavior matches the trend observed from the CV.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was applied to explore the charge transfer behavior and further asses the kinetics of the reaction. The Nyquist plots of the materials after 200 CVs are presented in Figure 3e. Materials with 3D mesoporous structure cannot form an ideal capacitance in the double‐layer at the electrolyte/electrode interface due to their high porosity and, consequently, the roughness of the catalyst layer on the surface of the electrode. Therefore, constant phase element (CPE) is used in this experiment to model the equivalent circuits of the metal oxides, considering that it already includes the non‐ideality factor, which describes the abovementioned features of the catalyst. The equivalent circuit models are presented in Figure S17a,b and described in detail in the Supporting Information. NiCo and CuNiCo‐2‐8 exhibit two semicircles, which indicates complex processes, and were fitted with the model presented in Figure S17a. However, Co, CuCo, CuNiCo‐5‐5, and CuNiCo‐8‐2 oxides demonstrate a single arc in the impedance response and were fitted with the simple Randel's circuit (Figure S17b). Fitted values are presented in Table S4. The electrolyte resistance (R Ω ) is quite consistent for all samples (in the range of 4.5–5.5 Ω), which is typical for 1 m KOH electrolyte.[ 16 , 47 , 60 ] Ni‐containing samples have lower charge‐transfer resistance (R ct) compared to the Cu‐rich samples or pure Co3O4, that is, CuNiCo‐2‐8 shows the lowest value of 2.1 Ω, and Co3O4 and CuNiCo‐8‐2 have the highest values (i. e., 34.8 and 16.6 Ω, respectively). Rs is related to the rate of the production of the intermediate species during the reaction and indicates the ease with which these species can be formed. [61] Both NiCo and CuNiCo‐2‐8 oxides have very low Rs resistance values of 0.9 and 0.5 Ω, respectively. A clear correlation between the charge‐transfer resistance and the overpotential at 10 mA cm−2 after cycling the catalysts for 200 CVs (Figure S18) emphasizes the role of Cu in the trimetallic system. Overall, the small amount of Cu lowers the resistance of the NiCo oxide and facilitates the Fe‐uptake from the electrolyte, which further improves the conductivity of the system. [57]

Electrochemical double‐layer capacitance (C dl) and corresponding electrochemical surface area (ECSA) were obtained from the CV measurements (Figure S19) in the non‐Faradaic region at the different scan rates (details in the Experimental Section). Figure 3f shows the linear behavior of the capacitive current difference at 1.05 V vs. the scan rate. Higher amounts of Cu (Cu/Ni≥1:1) in Co‐based oxides seem to lead to an increase of the ECSA. CuNiCo‐5‐5 and CuNiCo‐8‐2 have the highest ECSA of 28 and 25 cm2, respectively. This might be explained by enhanced interactions between metals, which results in a large number of active sites and more stable active species formed on the surface of the catalysts. Moreover, the presence of CuO and NiO impurities in the catalysts might affect the results, and thus further research based on in‐situ techniques is required to conclude on the role of each metal in the materials. Interestingly, CuNiCo‐2‐8 with a low Cu/Ni ratio has similar ECSA as NiCo and CuCo oxides (Figure S20), which agrees with the assumption about the weaker OH binding. Evaluation of the intrinsic activities of the catalysts includes normalizing the collected current by ECSA and BET in the case of the porous materials. Figure S21 presents the current densities extracted from these calculations. CuNiCo‐2‐8 (Cu/Ni=1 : 4) remains the most active material agreeing with the research of Park et al., [33] where the samples with the Cu/Ni ratio of 1 : 3 showed the best electrochemical performance, and Chung et al., [24] where it was shown that combining Ni and Cu (Cu/Ni=1 : 3) creates a better host for the Fe‐adsorption, resulting in increased catalytic activity. CuNiCo‐5‐5 and CuNiCo‐8‐2 do not demonstrate such high normalized activity, implying that the active sites present on the surface of the catalysts are less active even though these samples exhibit the highest ECSA. Normalizing by the BET surface area shows that the density of the active sites per geometric surface area is higher for the Ni‐rich samples, such as CuNiCo‐2‐8, CuNiCo‐5‐5, and NiCo.

Summarizing the results obtained in non‐purified KOH, we assume that by introducing low amount of Cu into the NiCo oxide (Cu/Ni≤1 : 1) the electronic interactions between metals were altered, which facilitates the formation of the active intermediate species on the surface of the catalyst by providing a better host for Fe‐adsorption. Moreover, Cu−Ni/Co interactions decrease the charge‐transfer resistance and increase the activity of the catalyst. CuNiCo‐5‐5 oxide combines the highest ECSA, low charge‐transfer resistance, low Tafel slope and low overpotential with high current density. However, the addition of high amounts of Cu (Cu/Ni>1 : 1) increases the ECSA presumably by accumulating produced active intermediates on the surface of the catalyst and hinders the activation of the catalyst due to the higher charge‐transfer resistance.

To confirm the role of Cu in the electrochemical performance of CuNiCo oxides, we compare the performances of NiCo and CuNiCo‐2‐8 in Fe‐free electrolyte. The additional activation of the Ni‐rich materials due to the Fe‐adsorption is excluded in this case. Figure 4a,b demonstrates the LSV curves before and after 200 CVs and CV (inset) in the purified electrolyte. As seen, the addition of Cu into NiCo system enhances the current density, even though it is not as pronounced as in the non‐purified electrolyte. Although the Tafel slopes (Figure 4c,d) are identical for both catalysts before and after 200 CVs, CuNiCo‐2‐8 demonstrates a higher current density and lower overpotential (Table S5). The redox peaks in the CV obtained in this case are identical to the ones in the non‐purified electrolyte (Figure S15), except for their higher intensities, highlighting a higher Ni2+ conversion to Ni3+−(O)OH and Co3+ to Co4+−(O)OH active species, respectively. Similar to the results in non‐purified KOH, the presence of Cu in NiCo oxide shifts the position of the Ni oxidation peak to higher potential. Poorer performance of the oxides in the purified electrolyte might be explained by the absence of the highly conductive Ni(Fe)−(O)OH active intermediate species that are typically formed in the non‐purified KOH. [1] This assumption is further confirmed by the EIS data. Figure 4e represents the Nyquist plot of the catalysts measured in purified 1 m KOH. The experimental Nyquist plot was then fitted to the circuit model as shown by Figure S22. The CuNiCo‐2‐8 has a lower charge‐transfer resistance (21.1 Ω) in Fe‐free 1 m KOH compared to NiCo oxide (31.1 Ω), underlining the intrinsic role of trimetallic system to enhance the OER activity, also in absence of any Fe cations (Table S6). Figure S23 presents the double‐layer capacitance plots and ECSA of the nanocast mixed metal oxides measured in the purified 1 m KOH solution. The samples measured in the purified electrolyte exhibit higher ECSA values (20.5 cm2 for CuNiCo‐2‐8 and 18.8 cm2 for NiCo oxide) than the ones in non‐purified KOH. The improved performance of CuNiCo‐2‐8 compared to bimetallic NiCo oxide proves the important role of Cu in the NiCo oxide system: small amount of Cu provides higher number of more active sites, improves conductivity and charge transfer, which all together improves the electrocatalytic performance of the materials toward the OER.

Figure 4.

OER LSV and CV (inset) curves of (a) CuNiCo‐2‐8 and (b) NiCo oxides (black line: initial LSV, the color of the LSV lines corresponds to the color of CV). Tafel slopes (c) before and (d) after 200 CVs, (e) Nyquist plot, (f) chronopotentiometry of CuNiCo‐2‐8@carbon paper at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 over 12 h, and (f, inset) TEM image of CuNiCo‐2‐8 after the stability test in purified 1 m KOH.

A long‐term stability test of CuNiCo‐2‐8 was performed on carbon fiber paper in the purified 1 m KOH solution. Figure 4f displays the chronopotentiometry result and a TEM image of the material after the test. CuNiCo‐2‐8 demonstrates good electrocatalytic stability for over 12 h. As shown in the Figure 4f, the 3D ordered mesoporous structure of the oxide remains, which indicates excellent stability of the catalyst structure. However, an amorphous phase on the surface region can be observed on the HRTEM image of the sample after the chronopotentiometry test for over 12 h (inset in Figure 4f, Figure S24). According to the work of Bergmann et al. [62] such surface amorphization is reversible and typical for Co‐based spinels due to the evolution of Co(O)OH phase at the applied potential bias. Figure S25a–c presents the elemental mapping and the results of the spot EDX analysis of the blank carbon paper, and CuNiCo‐2‐8 loaded on carbon paper before and after the chronopotentiometry test, respectively. The Cu/Ni/Co ratio before the analysis is slightly altered due to the presence of Cu in the substrate. After the test, the overall metal ratio does not change drastically, although the amount of Cu slightly decreases due to the dissolution of CuO in alkaline environment. However, this did not influence the performance of the electrocatalyst. According to Chung et al., [24] Ni−Cu interactions might slow down the dissolution of Cu in KOH. Since CuNiCo‐2‐8 consists of two phases including the spinel (Cu,Ni)xCo3‐xO4 and CuO, and there is minor amount of Cu present in the carbon cloth, we assume that the loss of copper is observed mostly due to the dissolution of CuO from the catalyst and the substrate. The electrolyte was analyzed after the long‐term stability test by ICP‐OES, and the concentration of Cu in the electrolyte solution was found to be around 15 μg kg−1 (Table S7), which is calculated to be comparable to the Cu amount in CuO phase in the initial material. [40]

ORR performance

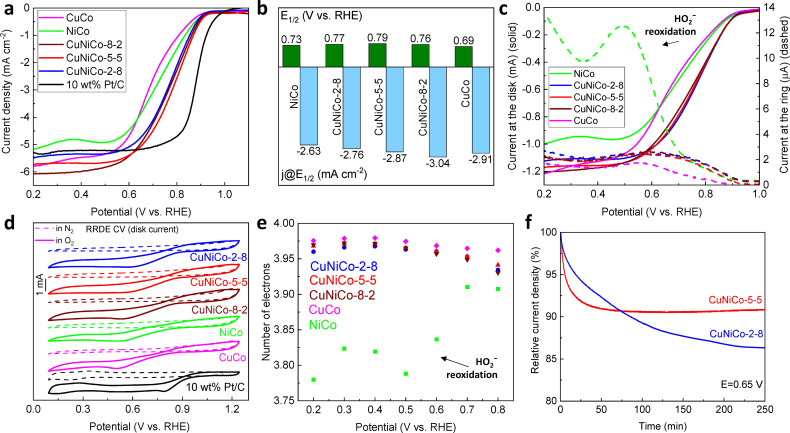

In addition to OER performance, it is of interest to determine whether the combination of Cu and Ni in Co‐based oxide lattice could also affect the reduction of oxygen in an alkaline environment. To evaluate the electrocatalytic activity toward ORR, the catalysts were loaded on GC RDE and subjected to LSV and CV measurements in N2 and O2‐saturated 0.1 m KOH solutions. For the sake of comparison, a similarly modified GC electrode with the commercial catalyst (10 wt % Pt/C) was prepared. As shown in Figure 5a, CuCo oxide shows issues in the mixed kinetic‐diffusion controlled region resulting in lower half‐wave potential (E 1/2) of 0.69 V vs. RHE (Figure 5b). Although it has a higher diffusion‐limiting current density than NiCo oxide, both materials demonstrate a slight wave instead of a plateau. Combining Cu and Ni in Co‐oxide lattice improves the performance of the material, which leads to the positive shift in E 1/2, suggesting that there are more accessible active sites for ORR that facilitate the reaction. [63] Moreover, the plateau of the CuNiCo samples is flatter with a narrower mixed kinetic‐diffusion controlled region, which also implies better reaction kinetics. The Tafel plots derived from the LSV curves are presented in Figure S26a. Generally, there is no significant difference between the Tafel slopes of the reference 10 wt % Pt/C and the nanocast mixed metal oxides. The CuCo sample has the highest value of 111 mV dec−1 indicating slow kinetics of the reaction. CuNiCo‐2‐8 demonstrates the lowest Tafel slope of 92 mV dec−1. Since some of the samples showed a slight inconsistency in the diffusion‐limited current densities, we performed the LSV measurements using rotating ring‐disk electrode (RRDE) as WE to study the electrooxidation of the side reaction's product, HO2 −, on the Pt ring of the electrode. The higher the current at the ring of RRDE, the more HO2 − was produced during the side reaction along with the main 4e− reaction path and, consequently, re‐oxidized on the Pt ring. Predictably, NiCo oxide produces the highest amount of HO2 − while catalyzing the ORR (Figure 5c) among all the tested samples. The addition of Cu limits this side reaction substantially, resulting in reduced ring current for all Cu‐containing samples. CuCo oxide shows the lowest ring current and low HO2 − formation (less than 2 %) (Figure S26 b). CuNiCo oxides also show an extremely low amount of peroxide production (2–3 %) at different potentials. On the other hand, Cu‐free NiCo has a non‐uniform behavior, where the fraction of the HO2 − anions varies from 5 to 12 %.

Figure 5.

(a) ORR LSV curves in O2‐saturated 0.1 m KOH; (b) half‐wave potentials and the respected current densities; (c) LSV curves collected from the disk (solid lines) and the ring (dashed lines) of RRDE; (d) ORR CVs collected in N2 and O2‐saturated 0.1 m KOH; (e) the number of electrons transferred extracted from RRDE measurements; and (f) chronoamperometry of CuNiCo oxides collected at 0.65 V.

Figure 5d presents the CV collected in N2 and O2‐saturated 0.1 m KOH solutions. In the N2‐saturated solution, all samples show no cathodic redox peaks. Well‐defined cathodic peaks are observed only in the presence of O2, revealing catalytic activity of the oxides toward ORR. There is also a positive shift in the peaks and onset potentials in the case of the CuNiCo samples. To further clarify the ORR mechanism, the number of electrons transferred (n) during the reduction of a single O2 molecule was estimated. Two methods were employed for this purpose: the Koutecky‐Levich theory [64] and the RRDE‐based approach [4] (see the Experimental Section). The method based on the Koutecky‐Levich equation requires collecting LSV curves at various rotating speeds (e. g., from 400 to 2500 rpm, Figure S27), where the diffusion‐limited current density should increase with raising the rotating speed of RDE. After presenting the obtained data as 1/j vs. ω −1/2, which is known as Koutecky‐Levich plots (Figure S28), and a series of calculations, the number of electrons transferred can be estimated. From the linearity of the Koutecky‐Levich plots, we can conclude first‐order reaction kinetics to the concentration of O2. The number of electrons in the case of NiCo is lower than for the rest of the samples probably because of mixed 4e− and 2e− reaction pathways. Compared to NiCo, there is a clear increase in the number of electrons transferred for CuNiCo oxides, and the value of n is estimated to be around 4, indicating a 4e− reaction pathway. However, this approach is not the most precise for (nano)porous catalysts since the roughness of the electrode's surface is too high due to the porosity of the catalyst, leading to higher error in the estimated number. Therefore, n was also calculated using a method based on the RRDE measurements. As seen in Figure 5e, for all the mixed metal oxides, except NiCo oxide, the estimated number of electrons is in the range of 3.93–3.97 suggesting that these oxides catalyze ORR through the 4e− path in both diffusion‐ and mixed kinetic‐diffusion‐controlled regions. The reduced value of n for NiCo correlates with the estimation based on the Koutecky‐Levich theory and Figure 5c, which shows the electrooxidation of HO2 − species produced during the reaction along with the main reaction, O2 electroreduction to OH−. This unwanted side reaction decreases the overall number of electrons transferred because this pathway includes the production of HO2 − at the disk, which is a 2e− reaction path.

To assess the stability of the catalysts, an accelerated durability test (ADT) was employed, as suggested previously.[ 65 , 66 ] Figure S29 represents the LSV curves collected before and after the ADT. The current densities of the CuNiCo samples do not decrease drastically after 1000 cycles showing excellent stability. NiCo demonstrated poor stability with a decrease in the current density of around 10 %. Since CuNiCo‐2‐8 and CuNiCo‐5‐5 outperformed the other oxides in catalyzing the OER, the long‐term stability of these materials was tested by performing chronoamperometry at an applied potential of 0.65 V vs. RHE for over 15000 s. CuNiCo‐2‐8 shows a continuous decrease in current reaching a plateau at around 86 % of remained current density within 230 min (Figure 5f). The relative current of CuNiCo‐5‐5 reaches the plateau with more than 90 % remained current density within the first 60 min of the test, which is comparable to the results published within the last few years. [67] We assume that high amount of Ni in CuNiCo‐2‐8 is not beneficial for the stability of the catalyst for the ORR, while the Cu/Ni ratio of around 1 : 1 helps to stabilize the catalyst. The combination of the high current density and significantly decreased side‐reaction, mainly 4e− path of the reaction and excellent stability make CuNiCo oxides better catalysts for the reduction of oxygen in alkaline conditions. Although nanocast CuNiCo oxides do not reach the level of performance of Pt/C in catalyzing ORR, there is a clear improvement compared to the bimetallic CuCo and NiCo oxides. This makes them nonetheless interesting bifunctional catalysts. Moreover, their performance compares well to the results presented in the literature (Tables S8, S9).

The results obtained here imply that incorporation of Cu and Ni into the Co‐based spinel oxide improves electrocatalytic properties of the material by altering the electronic interactions between metals. We assume that the increased activity might be originated from the Co3O4‐based spinel structure containing Co2+/Co3+ and Ni2+/Ni3+ redox couples combined with the Ni/Cu sites, which makes the surface of the catalyst a better host for Fe‐adsorption. Furthermore, the altered electronic structure (variable M−O strength) and the presence of different active sites upon the Cu and Ni substitution might be the reasons for the improved electrocatalytic activity of the materials. Excellent stability of CuNiCo oxides during OER and ORR in alkaline media is assigned to the 3D mesoporous structure and the interactions between the metal cations in the mixed oxide phase, which prevents the dissolution of Cu in an aggressive alkaline environment.

OER and ORR performances in aprotic Li−O2 cells

Rechargeable aprotic Li−O2 battery is a promising potential technology for next‐generation energy storage systems, but its practical application still faces many challenges. The voltage hysteresis during cycling is large, giving rise to low energy efficiencies and high overpotentials, in turn causing significant electrode and electrolyte decomposition. Thus, it is necessary to develop high‐performance catalysts for the cathode to address the challenges raised by the overpotential and to boost the performance of Li−O2 batteries. [68] Among the ordered mesoporous CuNiCo oxides prepared in this work, we selected the CuNiCo‐5‐5 (Cu/Ni≈0.9 : 1) for the tests in aprotic Li−O2 cells as this material shows an excellent activity and stability in KOH solution for both oxygen evolution and reduction reactions.

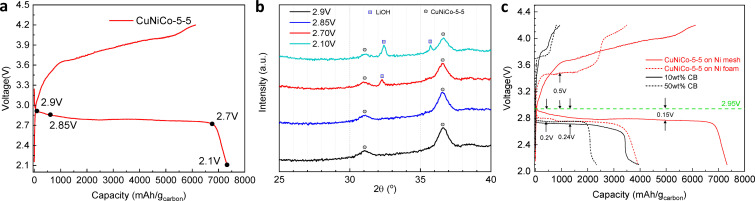

The performance of non‐aqueous Li−O2 batteries is directly determined by the reversible formation mechanism of the discharge products, being either Li2O2 [69] or LiOH. [70] LiOH is generally formed in the discharged cathodes when exposed to air, humidified O2 and water‐containing electrolytes. [71] We tested the material at full discharge in order to fully investigate the discharge products in presence of the catalyst. Figure 6a,b shows the results of the ex‐situ XRD test performed in different voltage steps for the first discharge cycle. LiOH is the only crystalline discharge product observed at the end of the plateau and at the end of discharge at 2.7 and 2.1 V vs. Li/Li+, respectively. The formation of LiOH is explained mainly by the presence of water in the cell, originated from the adsorbed H2O on the surface of the CuNiCo‐5‐5 (as evidenced by XPS measurements for the O3 peak, see Figure S12) that increased the water content in the electrolyte to 447.2 ppm, as well as the presence of a combination of Ni(OH)2 and NiO on the surface that promotes formation of LiOH over Li2O2. The intensity of the peaks for LiOH is increasing towards the end of discharge suggesting that LiOH is efficiently filling up the pore volume available in the electrode mixture containing 3D‐ordered mesoporous oxide and carbon, leading to much larger capacities in the cell. Two distinct morphologies of the Li2O2 as discharge product are reported in literature: a crystalline phase with toroid‐shaped particles and an amorphous film‐like morphology, which cannot be detected by XRD. The amorphous Li2O2 shows a charge plateau at 3.5–3.6 V vs. Li/Li+, and the crystalline Li2O2 has a voltage plateau at 4 V vs. Li/Li+. [69] The absence of clear plateaus in these voltage ranges confirms the formation of LiOH as the main discharge product along with amorphous Li2O2. Indeed, LiOH is oxidized to release O2 gas at a voltage up to 3.9 V (semi‐plateau in voltage profile).

Figure 6.

Characterization of the CuNiCo‐5‐5@Ni mesh electrode at different states during a full discharge to 2.1 V vs. Li/Li+ at 15 μA. (a) Electrochemical profile of a full discharge. Filled circles indicated the states at which the characterizations were performed. (b) Corresponding XRD pattern of the CuNiCo‐5‐5 electrode at different states of discharge. (c) Electrochemical performance of the Li‐O2 batteries and characterization of the CuNiCo‐5‐5 electrode after discharge. Discharge–charge voltage profiles of Li−O2 cells with Super C 45 carbon electrodes (10 and 50 %) and Super C 45 carbon+CuNiCo‐5‐5 electrode with 1 m LiNO3 in DMSO as the electrolyte. The batteries were tested between 2.1 and 4.2 V at 15 μA.

As shown in Figure 6c, a lower overpotential was observed for CuNiCo‐5‐5 material loaded on both Ni‐mesh and Ni‐foam up to 1000 mAh gcarbon −1 in ORR with a S‐shaped profile as compared to carbon. This is due to the presence of the catalyst and the higher porosity of the electrodes. The lower overpotential value for CuNiCo‐5‐5@Ni‐mesh electrode remains stable until reaching the full discharge. The charge voltage profile during OER for CuNiCo‐5‐5@Ni‐mesh increases with a rather steep slope as the charge proceeds to above 3.6 V vs. Li/Li+ (mainly oxidation of LiOH) and then gradually increases to reach 4.2 V vs. Li/Li+ (the semi‐plateau might be attributed to the oxidation of Li2O2). The voltage profile of CuNiCo‐5‐5@Ni‐foam electrode illustrates a clear plateau at 3.45 V vs. Li/Li+ for an effective oxidation of LiOH. This behavior is different from the cells containing only carbon (different content in the electrode) mainly due to the influence of CuNiCo‐5‐5 acting as catalyst by providing the 3D‐ordered mesoporous structure to facilitate the Li‐ion and oxygen transport and provide reaction sites for decomposition of LiOH and Li2O2 during charge. Indeed, O2 evolution is detected along with LiOH decomposition up to 3.45 V vs. Li/Li+ and at higher voltages. Products from parasitic reactions can be detected at high voltages as the plateaus are not flat.

Li−O2 batteries generally display poor cyclic performance at full discharge/charge condition because the high discharge/charge depth may result in undesired electrolyte decomposition or side reactions. Despite that, we observed promising properties of the mesoporous CuNiCo oxides as catalyst that can effectively promote the ORR at a lower overpotential and, depending on the electrode structure (CuNiCo‐5‐5@Ni‐foam), can decrease the charge overpotential in OER. This lower overpotential is a key step in the development of reversible Li−O2, particularly in LiOH‐based Li−O2 due to increased stability of LiOH over other discharge products.

Conclusion

We have synthesized well‐ordered high‐surface‐area mesoporous Cu/Ni/Co oxides. The samples are a mixture of the spinel structure and minor NiO and/or CuO phases. The obtained CuNiCo oxides exhibit enhanced oxygen evolution (OER) and oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) activities compared to the pure cobalt oxide and bimetallic NiCo and CuCo equivalents. Based on the detailed OER study, we conclude that the presence of small amount of Cu plays a substantial role in improving the conductivity of the catalyst and facilitating Fe−Ni interactions, which is beneficial for water oxidation. CuNiCo‐2‐8 (Cu/Ni=1 : 4) shows the best performance as the electrocatalyst in both non‐purified and purified 1 m KOH solution and demonstrates an excellent stability in purified KOH solution. The activity of the CuNiCo catalysts toward ORR also increases compared to bimetallic CuCo and NiCo oxides. The addition of Cu increases the activity of the catalyst and limits the side reactions during ORR favoring the 4e− reaction pathway, while Ni improves the reaction kinetics resulting in the higher half‐wave potential. The enhanced bifunctional activity of the CuNiCo oxides can originate from strong electronic interactions between the metals, which results in a synergistic effect that is most prominent in the case of the Cu/Ni ratio of ≤1 : 1, as seen from the volcano trends observed in this work. Moreover, CuNiCo‐5‐5 demonstrated promising preliminary results in catalyzing ORR and OER in aprotic Li−O2 cells. Both charge and discharge reactions occurred at lower overpotentials compared to the cells with carbon cathodes. LiOH was identified as the main discharge product using CuNiCo‐5‐5 as catalyst for the reaction, which is of a great interest due to the higher stability of LiOH over Li2O2. These results make CuNiCo oxides attractive for their use in water electrolysis and metal–air batteries. However, further research on the electrocatalytic behavior of CuNiCo‐based oxides in aprotic Li−O2 cells including experiments with limited capacities, formation/decomposition of the discharge product, and impedance studies are necessary.

Experimental Section

Materials

Pluronic P123, EO20PO70EO20 (Sigma‐Aldrich, Germany), HCl, 37 % (Sigma–Aldrich, Germany), n‐butanol, 99 % (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) (Sigma–Aldrich, China), ethanol, 96 % (Brenntag, Austria), Co(NO3)2 ⋅ 6H2O, Cu(NO3)2 ⋅ 3H2O, Ni(NO3)2 ⋅ 6H2O (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany), n‐hexane (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany), NaOH pellets, 85 % (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany), Nafion, 5 % solution (Sigma‐Aldrich, Germany), KOH pellets, 85 % (VWR Chemicals, Germany), 2‐propanol (Sigma–Aldrich, Germany), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, ≥99.9%, Sigma‐Aldrich, Austria), lithium nitrate (LiNO3, 99,99% trace metal basis, Sigma Aldrich, Austria), 1‐methyl‐2‐pyrrolidone (NMP, binder solvent, Sigma Aldrich, Austria), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF, Sigma Aldrich, Austria), Carbon black (CB) Super C45 (Imarys, Belgium). All chemicals were used as purchased.

Synthesis of ordered mesoporous silica

The 3D cubic ordered mesoporous KIT‐6 was synthesized according to Kleitz et al. [39] The copolymer poly(ethylene oxide)‐block‐poly(propylene oxide)‐block poly(ethylene oxide) (Pluronic P123, EO20PO70EO20) was used as the structure‐directing agent. In a typical synthesis, Pluronic P123 (5.13 g) was first dissolved in a solution of concentrated HCl (9.92 g) and distilled water (185.33 g). This mixture was stirred at 35 °C until the complete dissolution of the polymer. Then, butanol (5.13 g) was added at once under stirring as a co‐structure‐directing agent, and the mixture was stirred overnight at 35 °C. TEOS (11.03 g) was added to the solution in one shot, followed by stirring at 35 °C for 24 h. Afterward, the mixture was heated at 100 °C for 48 h in a convection oven (Binder, Germany). The resulting white solid product was filtered hot without washing, dried for 2 h at 100 °C, and then overnight at 140 °C. Subsequently, the powder was extracted in a solution of ethanol (200 mL) in which 2 drops of concentrated HCl (37 %) were added. Finally, the silica material was calcined in air at 550 °C (heating ramp ≈1.5° min−1) for 3 h.

Synthesis of ordered mixed metal oxides

3D‐ordered mesoporous oxides were synthesized using the one‐step impregnation nanocasting method (Scheme S1). [36] Metal nitrates [Co(NO3)2 ⋅ 6H2O, Cu(NO3)2 ⋅ 3H2O, and Ni(NO3)2 ⋅ 6H2O] were used as metal precursors as purchased. Typically, the nitrate salts (2.5 g) in stoichiometric proportion were pre‐mixed together with KIT‐6 silica powder (1 g) and ground in an agate mortar in the presence of n‐hexane (10 mL) until a homogeneous mixture was formed. The resulting mixture was subsequently dispersed in n‐hexane (30 mL) and stirred overnight under reflux at 80 °C. After cooling, the solid products were collected by filtration, dried in air at 70 °C, and then calcined at 500 °C for 5 h with the heating ramp of 1 °C min−1. Then, the silica template was selectively removed by treating the powders two times with NaOH (2 m, 24 h at 80 °C). Finally, the samples were washed twice with distilled water and once with ethanol and dried at 70 °C on air overnight. The amount of Cu and Ni nitrates was varied aiming to substitute Co2+ in CoCo2O4 spinel by Cu(x)+Ni(1‐x) [i. e., Cu(0.2)+Ni(0.8), Cu(0.5)+Ni(0.5), and Cu(0.8)+Ni(0.2)]. To simplify, the samples are named as CuNiCo‐2‐8 for Cu0.2Ni0.8Co2O4, CuNiCo‐5‐5 for Cu0.5Ni0.5Co2O4, and CuNiCo‐8‐2 for Cu0.8Ni0.2Co2O4. Reference Co3O4, NixCo3‐xO4 (NiCo), and CuxCo3‐x O4 (CuCo) materials were also synthesized using the same procedure to compare the electrocatalytic properties.

Material characterization

The porosity and textural properties of the samples were analyzed using N2 physisorption isotherms measured at −196 °C on an Anton Paar Quantatech Inc. iQ2 instrument (Boynton Beach, FL, USA). The samples were outgassed under vacuum at 150 °C for 12 h before measurement. The specific surface area (SSA) was calculated using the BET equation applied to data points measured in the relative pressure range 0.05≤P/P 0≤0.3. Pore size distributions were calculated from both desorption and adsorption branches of the isotherms by applying the NLDFT kernels of equilibrium and metastable adsorption, respectively, considering an amorphous SiO2 (oxide) surface and a cylindrical pore model. Total pore volume (for the pores smaller than 40 nm) was determined using the Gurvich rule. [38] The calculations were carried out using the ASiQwin 5.2 software provided by Anton Paar Quantatech Inc. The wide‐angle powder X‐ray diffractograms were recorded on a PANalytical EMPYREAN diffractometer equipped with the PIXcel3D detector (Malvern PANalytical, United Kingdom) in reflection geometry (Bragg–BrentanoHD). Low‐angle diffraction data were collected in a transmission geometry (Focusing Mirror) using Cu Kα1+2 radiation operated at a voltage of 45 kV, a tube current of 40 mA, and with a fixed divergence slit of 0.05 mm. Measurements were performed in continuous mode with a scan speed of 0.013° s−1. The refinement of the structures was carried out using PANalytical HighScore Plus software. Further details of the crystal structure investigation may be obtained from the Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe, 76344 Eggenstein‐Leopoldshafen (Germany), on quoting the depository number ICSD‐24211 (NiCo2O4), ICSD‐150807 (CuCo2O4), ICSD‐43179 (CuO), ICSD‐24210 (Co3O4), ICSD‐92132 (NiO). HRTEM images were taken with an Hitachi HF‐2000 transmission electron microscope equipped with a cold‐field‐emission gun, at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. Bulk EDX was conducted using a Hitachi S‐3500N. The microscope is equipped with a Si(Li) Pentafet Plus‐Detector from Oxford Instruments. The elemental mapping was performed using an EDX detector (Oxford Instruments) as additional equipment for a Zeiss Supra 55 VP SEM (Faculty Center for Nano Structure Research, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria). XPS measurements were carried out with a SPECS GmbH spectrometer with a hemispherical analyzer (PHOIBOS 150 1D‐DLD). The monochromatized Al Kα X‐ray source (E=1486.6 eV) was operated at 100 W. An analyzer pass energy of 20 eV was applied for the narrow scans. The medium area mode was used as lens mode. The base pressure during the experiment in the analysis chamber was 5×10−10 mbar. The binding energy scale was corrected for surface charging by use of the C 1s peak of contaminant carbon as a reference at 284.5 eV. For ICP‐MS measurements, an Agilent 7800 ICP‐MS (Agilent Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) was being employed, which was equipped with an Agilent SPS 4 autosampler (Agilent Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) and a MicroMist nebulizer at a sample uptake rate of approximately 0.2 mL min−1. The Agilent MassHunter software package (Workstation Software, Version C.01.04, 2018) was used for data evaluation.

Electrochemical testing

OER measurements: Electrochemical OER was performed in a typical three‐electrode configuration using SP‐150 Biologic potentiostat, a rotating disc electrode (RDE, model AFMSRCE, PINE Research Instrumentation), a hydrogen reference electrode (RHE, HydroFlex, Gaskatel), and Pt wire as a counter electrode (CE). Purified and non‐purified 1 m KOH solutions purged with argon were used as the electrolyte. The temperature of the cell was kept at 25 °C by using a water circulation system. Modified glassy carbon (GC) electrodes (PINE, 5 mm diameter, 0.196 cm2 area) were used as working electrodes. Before use, the GC electrodes were polished with Al2O3 suspension (1 and 0.05 μm, Allied High Tech Products, Inc.), followed by sonication in ultra‐pure water (18.2 MΩ ⋅ cm) for 5 min. Then, 4.8 mg of the catalyst were dispersed in a solution containing 0.75 mL of 18.2 MΩ ⋅ cm H2O, 0.25 mL of 2‐propanol, and 50 μL of Nafion (≈5 % in a mixture of water and lower aliphatic alcohols). The suspension was sonicated for 30 min to form a homogeneous ink. 5.25 μL of the catalyst ink was dropped onto the GC electrode and dried under light irradiation. The catalyst loading on the GC electrode was calculated to be 0.12 mg cm−2 in all cases. For long‐term measurement and post‐mortem analysis, the CuNiCo@carbon paper electrode was fabricated by drop‐casting the catalyst ink on the surface of carbon paper (Toray carbon paper, TGP‐H‐060) and was dried in room temperature. The loading was calculated as 0.5 mg cm−2 geometric area.

In all measurements, the iR (voltage drop) drop was automatically compensated at 85 % using the EC‐Lab v11.33 software. All LSV curves were collected by sweeping the potential from 0.7 to 1.7 V vs. RHE with a rate of 10 mV s−1. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements were carried out in the potential range between 0.7 and 1.6 V vs. RHE with a scan rate of 50 mV s−1. The activation of catalysts was achieved by conducting continuous CV scanning. Then, 200 CVs were applied to each sample, and LSV curves were collected before and after the CVs. The reproducibility of the electrochemical data was checked on multiple electrodes. The GC electrodes were kept rotating at a speed of 2000 rpm when LSV and CV curves were being measured. EIS was carried out in the same configuration by applying an anodic polarization potential of 1.6 V vs. RHE on the working electrode. The spectra were collected from 100 kHz to 100 mHz with an amplitude of 5 mV. The ECSA was determined by measuring the non‐Faradaic capacitive current associated with double‐layer charging from the scan‐rate dependence of CVs as suggested by Jaramillo and co‐workers. [49] CV scans with different scan rates, ranging from 20 to 180 mV s−1, were carried out in a narrow potential window from 1 to 1.1 V vs. RHE. By plotting the capacitive current (Δj=j anode–j cathode) against the scan rate and fitting it with a linear fit, the C dl can be estimated as half of the slope. The ECSA of each sample was calculated from its C dl according to this equation: ECSA=C dl/C s, where C s is the specific capacitance. In this work, 0.04 mF cm−2 was chosen as the reference value of the catalysts for OER in 1 m KOH solution. Stability tests of CuNiCoO‐2‐8 were performed in both non‐ and purified 1 m KOH. In the case of the non‐purified electrolyte, glassy carbon electrode was used as WE, while for the purified electrolyte CuNiCo‐loaded carbon paper was used as WE. Both measurements were carried out using chronopotentiometry where the potential was recorded at a constant current density of 10 mA cm−2.

KOH electrolyte purification: Fe impurity with 5–10 ppm concentration was contained in commercial KOH pellets and 0.5 ppm of Fe was estimated in unpurified 1 m KOH electrolyte solution. Hence, the 1 m KOH electrolyte was purified following the purification protocol by Boettcher et al. [50] The polypropylene centrifuge tubes and bottles were acid‐cleaned with a sulfuric acid solution before usage. High‐purity Ni(OH)2 precipitate as purification agent was prepared by dissolving 2 g of Ni(NO3)2 ⋅ 6H2O (Aldrich, high purity 99.999 % trace metals basis) in 4 mL of ultrapure water (Mili‐Q, 18.2 MΩ ⋅ cm resistance at 25 °C) and then mixed it with 20 mL of 1 m KOH solution. The mixture was vigorously shaken and centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 30 min. The green precipitate was separated from its supernatant by decantation. The precipitate was then redispersed and decanted three times with 20 mL of fresh 1 m KOH. To purify the KOH electrolyte, the prepared high‐purity Ni(OH)2 precipitate was dispersed in 40 mL 1 m KOH for 30 min and aged for 3 h. The mixture was then centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 30 min and decanted. After three rounds of centrifugation and decantation, the purified 1 m KOH supernatant was ready to be used for OER measurement.

ORR measurements: A standard three‐electrode cell with N2 or O2‐saturated 0.1 m KOH solution was used for the ORR measurements on PGSTAT302 N Autolab electrochemical workstation (Metrohm). A 5 mm diameter GC RDE or Pt/GC RRDE (Metrohm) was used as a working electrode, Ag/AgCl (Metrohm, 3 M KCl) and Pt plate (Metrohm, 1 cm2) were used as a reference and counter electrodes, respectively. Ag/AgCl RE was calibrated to the RHE. 5 mg of the sample was mixed with 5 mg of carbon black (CB) and dispersed in 0.7 mL of 18.2 MΩ ⋅ cm H2O, 0.25 mL of 2‐propanol, and 50 μL of Nafion (≈5 % in a mixture of water and lower aliphatic alcohols). The suspension was sonicated for at least 45 min to form a homogeneous ink. 10 μL of the catalyst ink was dropped onto the GC electrode and dried under light irradiation. The catalyst loading on the GC electrode was calculated to be 0.25 mg cm−2 in all cases including Pt/C (10 wt % Pt on carbon black). The net ORR curves were obtained by subtracting the background from the ones recorded in the O2‐saturated solution. The background was recorded at the same potentials and scanning rate using an N2‐saturated solution. WEs were cycled 20 times at the scan rate of 100 mV s−1 before the data were recorded. After that, the samples were scanned cathodically with the scan rate of 10 mV s−1 at the rotating speed of 1600 rpm. LSV at different rotating speeds (from 400 to 2500 rpm) were collected to calculate the number of electrons transferred (n) during ORR using the Koutecky–Levich equation [Eqs. (1) and 2]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where J is the measured current density, J K and J L are the kinetic‐ and diffusion‐limiting current densities, ω is the angular velocity, n is the transferred electron number, F is the Faraday constant (96 485 C mol−1), C 0 is the bulk concentration of O2 (1.2×10−6 mol cm−3), D 0 is the diffusion coefficient of O2 in 0.1 m KOH (1.9×10−5 cm2 s−1), and ν is the kinematic viscosity of the electrolyte (0.01 cm2 s−1).

RRDE measurements at 1600 rpm were carried out to determine the selectivity to the four‐electron pathway. The electrode was cycled 20 times at 100 mV s−1 before collecting the data, and then scanned at a rate of 10 mV s−1, and the ring electrode potential was set to 1.3 V vs. RHE. The hydrogen peroxide anion production yield (% HO2 −) and the electron transfer number (n) were calculated by the following Equations (3) and 4:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where i d and i r are the disk and ring currents, respectively, N is the ring current collection efficiency, which is determined to be 24.9 %. Accelerated durability test (ADT), which includes cycling the catalyst for 1000 cycles at 50 mV s−1 at potentials from 1 to 0.6 V vs. RHE at 1600 rpm was applied to assess the stability of the oxides. For further long‐term stability tests, CuNiCo‐2‐8 and CuNiCo‐5‐5 oxides were subjected to chronoamperometric measurements at 0.65 V vs. RHE at the rotation speed of 1600 rpm in O2‐saturated electrolyte.

Li−O2 cell testing: A slurry containing the electrode components was coated on Ni mesh to ensure the mechanical stability of the gas diffusion electrode (GDE) for the subsequent cell production using a doctor blade with the wet coating thickness of 90 μm and speed of 10 mm s−1. The slurry was prepared by mixing 70 wt % of the CuNiCo‐5‐5, 15 wt % of carbon Super C45 stirred and 15 wt % of a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF, 6 wt %) in N‐methylpyrrolidone (NMP) solution. The Super C45 carbon electrodes only contained PVDF and carbon (10 and 50 wt % of carbon). The coated electrodes were dried in air before drying in vacuum oven at 80 °C for 2 h. For further processing into electrochemical cells, 10 mm diameter discs from the GDE were cut and dried under high vacuum at 120 °C for 12 h and then transferred into an argon filled glovebox. Another type of the electrode, CuNiCo‐5‐5 loaded on Ni foam, was prepared by drop‐casting the ink, which was prepared for the ORR study (see the section above).

The electrolyte preparation was carried out in an argon filled glovebox with <0.1 ppm O2 and <0.1 ppm H2O. The electrolyte was 1 m LiNO3 in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Both LiNO3 and DMSO were dried before the preparation and then kept in the glovebox, however DMSO is highly hygroscopic and contains 0.047 % of water. All cells were measured against lithium (working and reference electrode). A typical cell consists of a lithium disc (10 mm Ø), two Whatman glass fiber GF/C Separators (12 mm Ø) soaked in 100 μL electrolyte and the GDE (10 mm Ø) with the respective active material. Modified Swagelok cells with an oxygen gas reservoir are used for the usual electrochemical analyses of Li−O2 batteries. The assembly of the cells takes place in argon filled glovebox to prevent reactions of water or direct contact of oxygen with metallic lithium to prevent and minimize side reactions prior to electrochemical testing. Before each measurement, the gas reservoir was evacuated three times and filled again with oxygen. Electrochemical cycling was performed between 2.1–4.2 V vs. Li/Li+ with a 15 μA constant current setup using a Maccor potentiostat at room temperature. For the ex‐situ XRD tests, the cells were stopped at different points of discharge (set by the voltage of the cell) and opened in an argon filled glovebox. The electrodes were then placed on a zero‐background silicon substrate in an airtight sample holder before the measurements (2θ angle between 25 and 40°). XRD measurements were carried out on a PANalytical X'pert Pro diffractometer with X'Celerator detector in reflection geometry. Cu Kα1+2 radiation operated at 45 kV and 40 mA, and a programmable divergence slit limiting the irradiated length to 10 mm were employed for data collection in continuous mode with a step size of 0.033° (2θ) and a data time step of 450 per s. A series of 12 diffractograms were taken over 3 h for each sample to check the stability of the discharge products in the sample holder, as well as the diffractogram for the main peak of Ni after each measurement to monitor any shifts in peak position.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

T.P. and F.K. thank Martin Schaier and Sophie Neumayer from the Institute of Analytical Chemistry (University of Vienna, Austria) for performing the ICP‐MS analysis. Sebastian Leiting (MPI für Kohlenforschung) is acknowledged for XPS measurements. The authors (T.P., F.K.) acknowledge the funding support of the University of Vienna, Austria. E.B. and H.T. acknowledge the Max Planck Society and the funding from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) Projektnummer 388390466‐TRR 247 within the Collaborative Research Centre/Transregio 247 “Heterogeneous Oxidation Catalysis in the Liquid Phase”. N.E., J.K., and M.J. acknowledge the financial support of the Austrian Federal Ministry for Climate Action, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology.

T. Priamushko, E. Budiyanto, N. Eshraghi, C. Weidenthaler, J. Kahr, M. Jahn, H. Tüysüz, F. Kleitz, ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202102404.

Contributor Information

Tatiana Priamushko, Email: tatiana.priamushko@univie.ac.at.

Prof. Dr. Freddy Kleitz, Email: freddy.kleitz@univie.ac.at.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Abbott D. F., Fabbri E., Borlaf M., Bozza F., Schäublin R., Nachtegaal M., Graule T., Schmidt T. J., J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 24534. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yan D., Li Y., Huo J., Chen R., Dai L., Wang S., Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1606459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Song F., Bai L., Moysiadou A., Lee S., Hu C., Liardet L., Hu X., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 7748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhao Q., Yan Z., Chen C., Chen J., Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tüysüz H., Hwang Y. J., Khan S. B., Asiri A. M., Yang P., Nano Res. 2013, 6, 47. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grewe T., Deng X., Tüysüz H., Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 3162. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deng X., Rin R., Tseng J., Weidenthaler C., Apfel U.-P., Tüysüz H., ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 4238. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deng X., Schmidt W. N., Tüysüz H., Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 6127. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moon G., Yu M., Chan C. K., Tüysüz H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3491–3495; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 3529–3533. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sa Y. J., Kwon K., Cheon J. Y., Kleitz F., Joo S. H., J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 9992. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alizadeh-Gheshlaghi E., Shaabani B., Khodayari A., Azizian-Kalandaragh Y., Rahimi R., Powder Technol. 2012, 217, 330. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mugheri A. Q., Tahira A., Aftab U., Bhatti A. L., Memon N. N., Memon J. U. R., Abro M. I., Shah A. A., Willander M., Hullio A. A., Ibupoto Z. H., RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 42387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zang N., Wu Z., Wang J., Jin W., J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 1799. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Broicher C., Zeng F., Artz J., Hartmann H., Besmehn A., Palkovits S., Palkovits R., ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 412. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li N., Bediako D. K., Hadt R. G., Hayes D., Kempa T. J., Von Cube F., Bell D. C., Chen L. X., Nocera D. G., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deng X., Öztürk S., Weidenthaler C., Tüysüz H., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 21225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gao X., Zhang H., Li Q., Yu X., Hong Z., Zhang X., Liang C., Lin Z., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu C., Fu S., Du D., Lin Y., Chem. A Eur. J. 2016, 22, 4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li S., Wang Y., Peng S., Zhang L., Al-Enizi A. M., Zhang H., Sun X., Zheng G., Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1501661. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Negahdar L., Zeng F., Palkovits S., Broicher C., Palkovits R., ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 5588. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li Y., Zou L., Li J., Guo K., Dong X., Li X., Xue X., Zhang H., Yang H., Electrochim. Acta 2014, 129, 14. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li P., Sun W., Yu Q., Yang P., Qiao J., Wang Z., Rooney D., Sun K., Solid State Ionics 2016, 289, 17. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang P. X., Shao L., Zhang N. Q., Sun K. N., J. Power Sources 2016, 325, 506. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chung D. Y., Lopes P. P., Farinazzo Bergamo Dias Martins P., He H., Kawaguchi T., Zapol P., You H., Tripkovic D., Strmcnik D., Zhu Y., Seifert S., Lee S., Stamenkovic V. R., Markovic N. M., Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 222. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bai Y., Fang L., Xu H., Gu X., Zhang H., Wang Y., Small 2017, 13, 1603718.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lefrançois Perreault L., Colò F., Meligrana G., Kim K., Fiorilli S., Bella F., Nair J. R., Vitale-Brovarone C., Florek J., Kleitz F., Gerbaldi C., Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1802438. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang K., Xia M., Xiao T., Lei T., Yan W., Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 186, 61. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li C., Zhang B., Li Y., Hao S., Cao X., Yang G., Wu J., Huang Y., Appl. Catal. B 2019, 244, 56. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Samanta S., Bhunia K., Pradhan D., Satpati B., Srivastava R., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fu H., Chen Y., Ren C., Jiang H., Tian G., Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1802052.. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yen H., Seo Y., Kaliaguine S., Kleitz F., ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 5505. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun Q., Dong Y., Wang Z., Yin S., Zhao C., Small 2018, 14, 1704137.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Park H., Park B. H., Choi J., Kim S., Kim T., Youn Y. S., Son N., Kim J. H., Kang M., Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1727.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tavares A. C., Cartaxo M. A. M., Da Silva Pereira M. I., Costa F. M., J. Electroanal. Chem. 1999, 464, 187. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yen H., Seo Y., Kaliaguine S., Kleitz F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yen H., Seo Y., Guillet-Nicolas R., Kaliaguine S., Kleitz F., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 10473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nair M. M., Yen H., Kleitz F., Comptes Rendus Chim. 2014, 17, 641. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thommes M., Kaneko K., Neimark A. V., Olivier J. P., Rodriguez-Reinoso F., Rouquerol J., Sing K. S. W., Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kleitz F., Choi S. H., Ryoo R., Chem. Commun. 2003, 2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Navarro M., May P. M., Hefter G., Königsberger E., Hydrometallurgy 2014, 147–148, 68. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mirzaei H., Nasiri A. A., Mohamadee R., Yaghoobi H., Khatami M., Azizi O., Zaimy M. A., Azizi H., Microchem. J. 2018, 142, 343. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lu D., Liao J., Zhong S., Leng Y., Ji S., Wang H., Wang R., Li H., Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 5541. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lu D., Liao J., Leng Y., Zhong S., He J., Wang H., Wang R., Li H., Catal. Commun. 2018, 114, 89. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bucci A., Garcíagarcía-Tecedor M., Corby S., Rao R. R., Martin-Diaconescu V., Oropeza F. E., De La V. I. A., Pẽ P., O'shea P., Durrant J. R., Giménez S., Giménez G., Lloret-Fillol J., J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 12700. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li N., Ai L., Jiang J., Liu S., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 564, 418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Biesinger M. C., Payne B. P., Grosvenor A. P., Lau L. W. M., Gerson A. R., Smart R. S. C., Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 2717. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yu M., Moon G., Bill E., Tüysüz H., ACS Appl. Energ. Mater. 2019, 2, 1199. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Skinner W. M., Prestidge C. A., Smart R. S. C., Surf. Interface Anal. 1996, 24, 620. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mccrory C. C. L., Jung S., Peters J. C., Jaramillo T. F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Trotochaud L., Young S. L., Ranney J. K., Boettcher S. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 6744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yu M., Budiyanto E., Tüysüz H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang B., Wang L., Cao Z., Kozlov S. M., García de Arquer F. P., Dinh C. T., Li J., Wang Z., Zheng X., Zhang L., Wen Y., Voznyy O., Comin R., De Luna P., Regier T., Bi W., Alp E. E., Pao C. W., Zheng L., Hu Y., Ji Y., Li Y., Zhang Y., Cavallo L., Peng H., Sargent E. H., Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 985. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang T., Nellist M. R., Enman L. J., Xiang J., Boettcher S. W., ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bothra P., Pati S. K., ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 858. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Alex C., Sarma S. C., Peter S. C., John N. S., ACS Appl. Energ. Mater. 2020, 3, 5439. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yan J., Kong L., Ji Y., White J., Li Y., Zhang J., An P., Liu S., Lee S.-T., Ma T., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Burke M. S., Kast M. G., Trotochaud L., Smith A. M., Boettcher S. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stevens M. B., Enman L. J., Batchellor A. S., Cosby M. R., Vise A. E., Trang C. D. M., Boettcher S. W., Chem. Mater. 2016, 29, 120. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dionigi F., Strasser P., Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1600621. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Budiyanto E., Yu M., Chen M., Debeer S., Rüdiger O., Tüysüz H., ACS Appl. Energ. Mater. 2020, 3, 8583. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Doyle R. L., Lyons M. E. G., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 5224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bergmann A., Martinez-Moreno E., Teschner D., Chernev P., Gliech M., De Araújo J. F., Reier T., Dau H., Strasser P., Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pendashteh A., Palma J., Anderson M., Marcilla R., Appl. Catal. B 2017, 201, 241. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Koutecky J., Levich B., Zh. Fiz. Khim. 1958, 32, 1565. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sa Y. J., Seo D. J., Woo J., Lim J. T., Cheon J. Y., Yang S. Y., Lee J. M., Kang D., Shin T. J., Shin H. S., Jeong H. Y., Kim C. S., Kim M. G., Kim T. Y., Joo S. H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Han Y., Wang Y. G., Chen W., Xu R., Zheng L., Zhang J., Luo J., Shen R. A., Zhu Y., Cheong W. C., Chen C., Peng Q., Wang D., Li Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 17269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Osgood H., Devaguptapu S. V., Xu H., Cho J., Wu G., Nano Today 2016, 11, 601. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lu J., Dey S., Temprano I., Jin Y., Xu C., Shao Y., Grey C. P., ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 3681. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Li Z., Ganapathy S., Xu Y., Heringa J. R., Zhu Q., Chen W., Wagemaker M., Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Liu T., Leskes M., Yu W., Moore A. J., Zhou L., Bayley P. M., Kim G., Grey C. P., Science 2015, 350, 530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Guo Z., Dong X., Yuan S., Wang Y., Xia Y., J. Power Sources 2014, 264, 1-7. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.