Abstract

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF)/FGF receptor (FGFR) signaling pathway plays important roles in the development and growth of the skeleton. Apert syndrome caused by gain‐of‐function mutations of FGFR2 results in aberrant phenotypes of the skull, midface, and limbs. Although short limbs are representative features in patients with Apert syndrome, the causative mechanism for this limb defect has not been elucidated. Here we quantitatively confirmed decreases in the bone length, bone mineral density, and bone thickness in the Apert syndrome model of gene knock‐in Fgfr2 S252W/+ (EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ ) mice. Interestingly, despite these bone defects, histological analysis showed that the endochondral ossification process in the mutant mice was similar to that in wild‐type mice. Tartrate‐resistant acid phosphatase staining revealed that trabecular bone loss in mutant mice was associated with excessive osteoclast activity despite accelerated osteogenic differentiation. We investigated the osteoblast–osteoclast interaction and found that the increase in osteoclast activity was due to an increase in the Rankl level of osteoblasts in mutant mice and not enhanced osteoclastogenesis driven by the activation of FGFR2 signaling in bone marrow‐derived macrophages. Consistently, Col1a1‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice, which had osteoblast‐specific expression of Fgfr2 S252W, showed significant bone loss with a reduction of the bone length and excessive activity of osteoclasts was observed in the mutant mice. Taken together, the present study demonstrates that the imbalance in osteoblast and osteoclast coupling by abnormally increased Rankl expression in Fgfr2 S252W/+ mutant osteoblasts is a major causative mechanism for bone loss and short long bones in Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice.

Keywords: Apert syndrome, FGFR2, long bone, osteoblast–osteoclast interaction, Rankl

The present study shows that activating mutation Fgfr2 S252W decreases the long bone length and bone mineral density by elevating osteoclast activity stimulated by Rankl expression in osteoblasts.

1. INTRODUCTION

Apert syndrome is a rare genetic disorder that affects about 1 in 65,000–88,000 newborns (Czeizel et al., 1993) and its main symptoms are craniosynostosis (CS) caused by premature fusion of at least one cranial suture (Johnson & Wilkie, 2011). Apert syndrome also results in distinct facial features, such as midface hypoplasia and a cleft palate, and some patients have an underdeveloped jaw that can lead to dental problems (Naski & Ornitz, 1998; Wilkie, 1997; Yu et al., 2003). Most Apert syndrome cases are caused by a Ser252Trp (S252W) or Pro253Arg (P253R) missense mutation in the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene (Anderson et al., 1998; Yu et al., 2003). These mutations lead to the loss of specificities of the ligand–receptor interactions and consequently hyperactivation of downstream signaling (Anderson et al., 1998; Ibrahimi et al., 2004). Constitutively active FGFR2 signaling accelerates the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts in craniofacial sutures, which leads to premature fusion of sutures (Anderson et al., 1998; Ibrahimi et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2003). As its pathophysiological molecular mechanism, we have found that FGF/FGFR signaling stimulates transcription and transcriptional activation of RUNX2 via extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK)–mitogen‐activated protein kinase and protein kinase C pathways (Kim H. J. et al., 2003; Park et al., 2010). We also revealed that Pin1 is the downstream molecular target of FGFR2 in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice that mimic human Apert syndrome, which suggests a potential therapeutic target for CS and midface hypoplasia of Apert syndrome (Kim B. et al., 2020; Kim, Kim, et al., 2020; Kim, Shin, et al., 2020; Shin et al., 2018). However, the effect of these mutations on long bone growth has not been systematically studied and the mechanism is unclear.

FGFR genes are differentially expressed in the processes of osteogenesis and chondrogenesis. FGFR1 and FGFR2 are mainly expressed in mesenchymal progenitors and differentiating osteoblasts, respectively, in the perichondrium, bone collar, and trabecular bone (Britto et al., 2001; Coutu et al., 2011; Jacob et al., 2006; Molteni et al., 1999; Ohbayashi et al., 2002). FGFR3 is expressed more intensely in chondroprogenitor cells (Robinson et al., 1999), and FGFR1 and FGFR3 are expressed in mouse and human articular chondrocytes (Weng et al., 2012; Yan et al., 2011), which indicates that FGFR1 and FGFR3 play major roles in endochondral ossification. Alternative messenger RNA (mRNA) splicing of the third immunoglobulin‐like domain in FGFR genes results in different isoforms, namely IIIb and IIIc (Rice et al., 2003). These isoforms are not only differentially distributed during bone development, but also possess different ligand‐binding specificities (Ornitz & Itoh, 2001; Yu et al., 2003). However, immature cultured osteoblasts in vitro express relatively higher levels of Fgfr1, whereas mature osteoblasts express relatively higher levels of Fgfr2 (Rice et al., 2003). Such differential expression of Fgfr s may reflect distinct responses to exogenous FGFs such as FGF2 (Cowan et al., 2003). The FGF/FGFR signaling pathway disrupted by mutations in FGFR2 make the FGFR2 mutations in Apert syndrome change their ligand‐binding specificity. Specifically, the FGFR2 IIIc isoform binds more readily to FGF7 and FGF10, which are preferential ligands of FGFR2 IIIb, whereas the FGFR2 IIIb isoform is abnormally susceptible to binding with FGF2, FGF6, and FGF9, which commonly bind to either FGFR2 IIIc or FGFR1 IIIc in mesenchyme (Ornitz et al., 1996; Rice et al., 2003).

In addition to craniofacial deformities, short limbs appear to be a common feature of patients with Apert syndrome (Cohen & Kreiborg, 1993). Correspondingly, Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice exhibit shortened body and limb lengths, as well as a reduced bone mass compared with wild‐type (WT) mice (Chen et al., 2014; Morita et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2005). However, the effect of these mutations on long bone growth has not been systematically studied and its mechanisms are poorly understood.

In the present study, we found that Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice had a dramatic reduction in long bone length, bone mineral density (BMD), and bone thickness caused by an increase of osteoclast activity in trabecular bone without alteration of chondrocyte differentiation in epiphyseal growth plates. Our study also revealed that upregulation of Rankl in osteoblasts was a main factor of the increased osteoclast activation in Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice and suggested that modulation of this process was a promising strategy for reducing skeletal abnormalities of the limbs in Apert syndrome patients.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animal experiments

A mouse that carried a p‐loxP‐neo cassette, which blocks expression of the mutant Fgfr2 allele (Fgfr2 neoS252W/+ , genetic background is ~88% FVB, 6% Black Swiss, and 6% 129SEVE), was crossed with a ubiquitous Cre transgene mouse (EIIA‐Cre. B6.FVB‐TgN [EIIa‐cre] C3739Lm, 003724; Jackson Laboratory) and mature osteoblast‐specific Cre‐expressing mouse (Col1a1[2.3 kb]‐cre mouse, B6D2F1), which removed p‐loxP‐neo to allow specific expression of the mutant allele. Fgfr2 neoS252W/+ knock‐in mice and Col1a1‐cre transgenic mice were kindly provided by Dr. Chu‐Xia Deng (U.S. National Institutes of Health) and Dr. Je‐Young Choi (Kyungpook National University), respectively. Both male and female pups were examined in this study. The numbers of mice for each assessment are described in each figure legend. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen‐free conditions in an individual ventilating system. All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Special Committee on Animal Welfare, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

2.2. Micro‐computed tomography (CT) analysis

Mice were killed at postnatal Day 21 (P21) by CO2 inhalation and the hind limb was dissected and fixed with 4% of paraformaldehyde. Micro‐CT analysis was performed as described previously (Kim B. S. et al., 2021). Tibial bone analysis was performed using a CT Analyser (Bruker) and TriBON™ software (RATOC System Engineering Co.).

2.3. Histological analysis

For hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry (IHC) of tissue sections, P21 mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. Paraffinization of a dissected tibia was conducted (TP1020, Leica) after decalcification with 10% EDTA (pH 7.4). Detailed procedures were performed as described previously (Kim B. S. et al., 2021). IHC using antibodies against collagen Type X (COL10; 234,196, Millipore‐Sigma), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA; sc‐56, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), SOX9 (sc‐20095, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), MMP9 (sc6840, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), MMP13 (ab39012, Abcam), and nuclear factor‐κB (NF‐κB; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was conducted after antigen retrieval. All stained tissue images were acquired with a DP72 digital microimaging camera (Olympus) under a BX51 microscope (Olympus).

2.4. Tartrate‐resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining

To measure TRAP activity, tibial tissue sections and differentiated osteoclasts were stained using a TRAP‐staining kit (PMC‐AK04F, Cosmo Bio) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. The number of TRAP‐positive multinucleated cells per sample was counted using ImageJ software (National institutes of Health).

2.5. Primary cell isolation

Mouse primary osteoblasts (POBs) were isolated from calvarial bone in P21 mice. Dissected frontal and parietal bones were incubated with trypsin/EDTA (SH30042.01, HyClone Laboratories, Inc.) and Type II collagenase (LS004176, Worthington Biochemical Corp.) for 15 and 30 min, respectively. Detached fibroblastic cells and debris were washed out and the calvarial bones were incubated with Type II collagenase for an additional 1 h. Collected cells were filtered and seeded on the plate for further experiments or storage. For macrophages from the spleen and bone marrow, splenocytes were isolated from P0 mice and bone marrow cells were isolated from P21 mice. The spleen was crushed and dissociated using a 1 ml syringe. Bone marrow was flushed out suing a 1 ml syringe and bone marrow cells were dissociated. Spleen and bone marrow cells were treated with red blood cell lysis buffer Hybri‐Max™ (R7757, Sigma‐Aldrich) and plated on a petri dish overnight. Cells in the supernatant were collected and treated with 20 ng/ml macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (M‐CSF; 315‐02, PeproTech, Inc.) for 5 days. The cells were then used for further experiments or storage.

2.6. Cell culture

For osteoclast differentiation, bone marrow‐derived macrophages (BMMs) isolated from the spleen and bone marrow were seeded and cultured as described previously (Yoon H. et al., 2021). To induce osteoblast differentiation, confluent calvarial POBs were cultured in α‐minimum essential medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid, and 10 mM of β‐glycerophosphate. For coculture of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, primary calvarial osteoblasts were seeded and BMMs were added as described previously (Yoon H. et al., 2021). The medium was changed every 2 days.

2.7. Extraction of total RNA, reverse‐transcriptase PCR (RT‐PCR), and quantitative real‐time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using an RNeasy Mini Kit (#74104, Qiagen) and reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using a PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (RR036A, TaKaRa Bio) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. TB‐Green® Premix Ex Taq™ (RR420A, TaKaRa Bio) was used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) in an Applied Biosystems™ 7500 RT‐PCR system. Results were normalized to Gapdh expression. The primer sets used for qPCR are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer list used in this study

| For real‐time PCR | |

|---|---|

| Name | Oligonucleotide sequence |

| Gapdh(F) | 5′‐CAT GTT CCA GTA TGA CTC CAC TC‐3′ |

| Gapdh(R) | 5′‐GGC CTC ACC CCA TTT GAT GT‐3′ |

| Rankl(F) | 5′‐CAG CAT CGC TCT GTT CCT GTA‐3′ |

| Rankl(R) | 5′‐CTG CGT TTT CAT GGA GTC TCA‐3′ |

| Opg(F) | 5′‐ACC CAG AAA CTG GTC ATC AGC‐3′ |

| Opg(R) | 5′‐CTG CAA TAC ACA CAC TCA TCA CT‐3′ |

| Csf1(F) | 5′‐GAC CCT CGA GTC AAC AGA GC‐3′ |

| Csf1(R) | 5′‐TGT CAG TCT CTG CCT GGA TG‐3′ |

| Fgfr1(F) | 5′‐GCA GAG CAT CAA CTG GCT G‐3′ |

| Fgfr1(R) | 5′‐GGT CAC GCA AGC GTA GAG G‐3′ |

| Fgfr2(F) | 5′‐AAT CTC CCA ACC AGA AGC GTA‐3′ |

| Fgfr2(R) | 5′‐CTC CCC AAT AAG CAC TGT CCT‐3′ |

| Nfactc1(F) | 5′‐GGTGCCTTTTGCGAGCAGTATC‐3′ |

| Nfactc1(R) | 5′‐CGTATGGACCAGAATGTGACGG‐3′ |

| Ctsk(F) | 5′‐AGC AGA ACG GAG GCA TTG TGA‐3′ |

| Ctsk (R) | 5′‐ATC GCA GTC TGG GCA CTT GTG A‐3′ |

| Trap (F) | 5′‐CTG ACA AAG CCT TCA TGT CCA A‐3′ |

| Trap (R) | 5′‐GCG CCG GAG TCT GTT CAC TA‐3′ |

| Mmp9(F) | 5′‐CTG GAC AGC CAG ACA CTA AAG‐3′ |

| Mmp9(R) | 5′‐CTC GCG GCA AGT CTT CAG AG‐3′ |

2.8. DNA transfection

Fgfr2 WT and Fgfr2 S252W mutant expression vectors were generously provided by Professor Keiji Moriyama (Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan). Construction of the plasmid vectors has been described in a previous report (Tanimoto et al., 2004). These plasmid DNAs were transfected into MC3T3‐E1 cells using X‐tremeGENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent (XTG9‐RO, Roche) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol.

2.9. Statistics

All quantitative data are presented as means ± SD. Each experiment was performed at least three times. Results from representative individual experiments are shown in figures. Statistical analysis was performed by either one‐way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's test or the Student's t‐test using Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software). Here, p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice have a decrease in bone mass of the proximal tibia

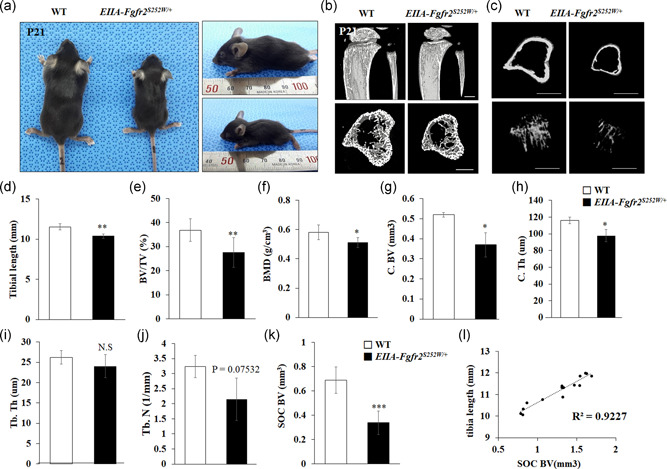

Compared with WT littermates, EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mutant mice exhibited a significant reduction in body length with a dome‐shaped skull and shortened skull length at P21, which are representative symptoms of Apert syndrome (Figure 1a). In addition, to determine whether limb shortening shown in Apert syndrome patients had occurred in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice, three‐dimensionally reconstructed images of proximal tibias were generated and analyzed by micro‐CT (Figure 1b,c). The total bone volume (BV) of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice was significantly reduced compared with that of WT mice (Figure 1b). In addition, significant decreases in the cortical BV (C. BV) and cortical bone thickness (C. Th) were found in EIIA‐Fgfr S252W/+ mice compared with WT mice (Figure 1c). Bone morphometric analyses supported the decreases in bone formation parameters, namely tibial length, BV/tissue volume (TV), and BMD, in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice compared with WT mice (Figure 1d–f). In line with these parameters, C. BV, C. Th, trabecular bone thickness, and trabecular bone number were clearly decreased in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice compared with WT mice (Figure 1g–j). These data demonstrated that the Fgfr2 S252W mutation impaired long bone growth. Interestingly, BV of the secondary ossification center (SOC) was significantly reduced in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice compared with WT mice (Figure 1k). Figure 1l shows a high correlation between the tibial length and SOC BV with 0.92 for the coefficient of determination of the regression equation (R 2), which indicated that tibial length is significantly correlated with SOC BV.

Figure 1.

EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice have decreases in long bone sizes and bone mineral density. (a) Physiognomy of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ and littermate wild‐type (WT) mouse at postnatal Day 21 (P21). The mutant mouse had a smaller body size and short head in the superior view (left) and lateral view (right). (b) Micro‐computed tomography (CT) images of the tibial growth plate at P21 in the arterial view of a coronal section and cross‐sectional views are shown for each genotype (n ≥ 5, scale bar: 1 mm). (c) Representative micro‐CT images of cortical (top) and trabecular (bottom) bones in the proximal tibia (n ≥ 5, scale bar: 2 mm). (d–l) Histomorphometric analyses of three‐dimensional (3D) micro‐CT data. (d) Tibial length; (e) BV/TV, bone volume/tissue volume; (f) BMD, bone mineral density; (g) C. BV, cortical bone volume; (h) C. Th, cortical bone thickness; (i) Tb. Th, trabecular thickness; (j) Tb. N, trabecular number. (k) SOC BV, secondary ossification center bone volume. (l) Regression equation that described relationship between the degree of deviation of SOC BV and the tibia length in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice. The R 2 value is the coefficient of determination of the regression equation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. NS, not significant

3.2. Fgfr2 S252W mutation does not affect chondrocyte differentiation in the growth plate but reduces trabecular bone

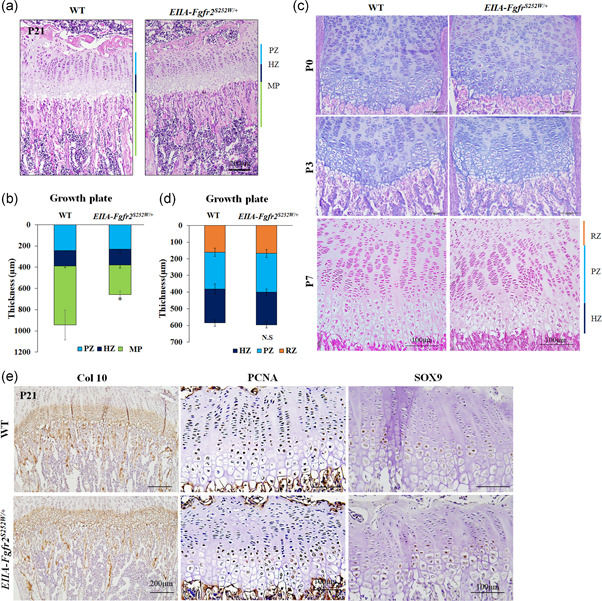

To determine whether the reduction of tibial bone growth caused by the Fgfr2 S252W mutation was related to the growth plate length, we examined the structure of tibia growth plates by histological analysis at P21. Unexpectedly, H&E staining showed a normal columnar organization of the growth plate and morphometric measurements of the lengths of proliferative and hypertrophic zones showed no significant differences between WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (Figure 2a,b). Similarly, at the earlier stages of newborns (P0), P3, and P7, H&E staining showed no apparent differences in chondrocyte differentiation of proximal tibial growth plate between WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (Figure 2c,d). However, the trabecular bone area was significantly reduced in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice compared with WT mice (Figure 2a,b). For confirmation, we performed IHC of COL10, PCNA, and SOX9, which are the specific markers for hypertrophic and proliferative chondrocytes, and the master transcription factor for chondrogenesis, respectively (Tang et al., 2020; Ushijima et al., 2014). Consistent with H&E staining, there was no difference in the expression levels of COL10, PCNA, or SOX9 in the growth plate of tibia between both genotypes (Figure 2e–g). Collectively, these data demonstrated that the decrease in the long bone length of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice was due to a decrease in trabecular bone and not the chondrocyte differentiation process in the growth plate.

Figure 2.

EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice show normal cartilage development and growth plate structures in long bones. (a) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)‐stained proximal tibiae at postnatal Day 21 (P21) from wild‐type (WT) and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (n = 4, scale bar: 200 μm). (b) Graph of morphometric measurements of the PZ, HZ, and MP. A normal structure of the epiphyseal growth plate was observed in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice. (c) Representative images of H&E‐stained proximal tibiae in newborn(P0), P3, and P7 WT (top) and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ (bottom) mice (scale bar: 100 μm). (d–f) Representative images of immunohistochemistry (IHC) at P21 revealed no apparent differences in expression of type 10 collagen (COL10) (d), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (e), and SOX9 (f) between WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (n = 4). HZ, hypertrophic zone; MP, metaphysis; PZ, proliferating zone

3.3. EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice have an increased osteoclast formation

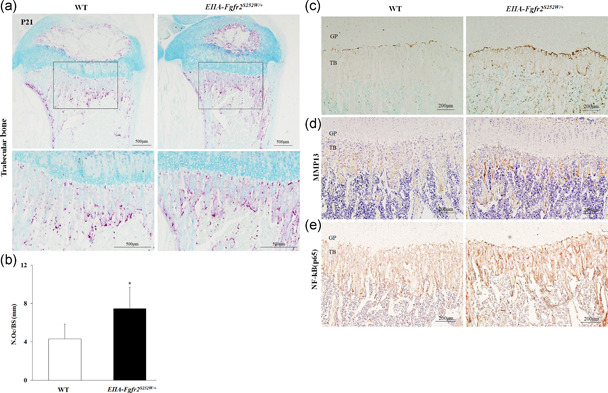

The balance between bone formation and resorption during bone remodeling is crucial to sustain the bone mass and systemic mineral homeostasis (Charles & Aliprantis, 2014). Considering that chondrocyte differentiation in the tibia growth plate was normal and trabecular bone was significantly reduced in mutant mice, we hypothesized that abnormal osteoclastogenesis was induced in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice. To test our hypothesis, we performed TRAP staining on the proximal tibia growth plate. The number of TRAP‐positive osteoclasts in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice was significantly increased compared with that in WT mice (Figure 3a). Most TRAP‐positive cells were mainly observed on cortical and trabecular bone surfaces that faced the bone marrow (Figure 3a). Quantitative analysis showed that the number of osteoclasts was significantly increased in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice compared with WT mice (Figure 3b). Consistently, IHC showed that the expression levels of MMP9, MMP13, and NF‐κB, which are osteoclast‐related factors, were also increased in the tibia growth plate (Figure 3c–e). These results strongly suggested that the Fgfr2 S252W mutation stimulated osteoclastogenesis, which reduced the trabecular bone mass and tibial length.

Figure 3.

Osteoclastogenesis is enhanced in the trabecular bone of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice. (a) Representative images of tartrate‐resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)‐stained trabecular bone and secondary ossification center (SOC) of proximal tibiae in postnatal Day 21 (P21) wild‐type (WT) and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice. TRAP‐positive purple spots indicate multinucleated osteoclasts (n = 3, scale bar: 500 μm). (b) Quantification of TRAP‐positive cells in the trabecular bones of WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice. Graph shows the number of osteoclasts per bone surface (N. Oc./BS). (c–e) Representative images of MMP9 (c), MMP13 (d), and nuclear factor‐κB (NF‐κB) (p65). (e) IHC of tibia trabecular bones in WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (n = 3, scale bar: 200 μm)

3.4. Fgfr2 S252W mutation affects the ability of osteoblasts to support osteoblast‐mediated osteoclast activation, but not osteoclastogenesis itself

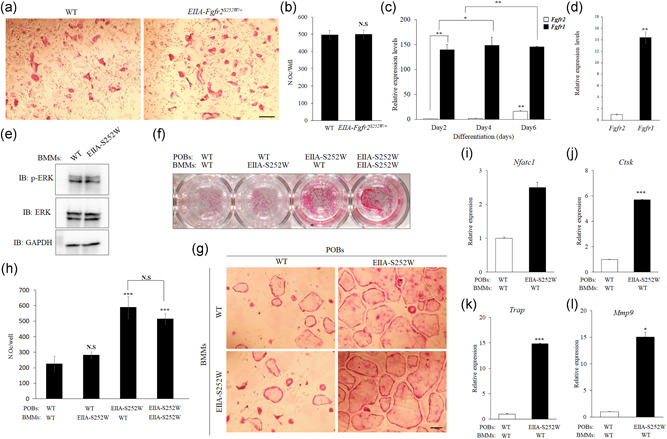

As EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice showed an increase of osteoclast formation in long bones, we investigated the possibility of aberrant differentiation of BMMs into osteoclasts. Unexpectedly, TRAP staining showed that the osteoclastogenic capacity of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ ‐derived BMMs was not significantly different from that of WT‐derived BMMs upon treatment with CSF1 and receptor activator of NF‐κB ligand (RANKL) (Figure 4a). Quantitative analysis showed that the number of osteoclasts was similar in both WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (Figure 4b). As Fgfr2 shows very high expression levels in osteoblasts (Han et al., 2015; Sugimoto et al., 2016; Yoon K. A. et al., 2017) but is not expressed in BMMs, we hypothesized that a mutation in Fgfr2 would not affect BMM differentiation itself. Therefore, we investigated the expression profile of Fgfr family genes in macrophages. Very similarly to the previously reported expression profile (Chikazu et al., 2001; Jacob et al., 2006), our results showed that expression of Fgfr1 was very high during the differentiation of macrophages isolated from the spleen (Figure 4c) and bone marrow of WT mice into osteoclasts (Figure 4d), whereas that of Fgfr2 was barely detectable at the indicated differentiation time points (Figure 4c,d). These data suggested that BMMs of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice did not directly influence osteoclast formation in the mutant mice. In addition, in contrast to previous papers showing profound abnormalities and high levels of ERK phosphorylation in osteoblasts of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (Shukla et al., 2007), we found that the level of ERK phosphorylation, a major downstream molecule of FGFR2 signaling, was not changed in differentiated osteoclasts of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice compared with WT (Figure 4e). To identify the cellular mechanism of the aberrant osteoclast activation in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252/+ mice, coculture experiments were performed using BMMs and POBs from WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice, respectively. The coculture experiments clearly indicated that the acceleration of osteoclast activity was dependent on Fgfr2 S252W/+ expression in POBs and not that in BMMs (Figure 4f,g). Quantitative analysis showed that the number of TRAP‐positive multinucleated osteoclasts in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice was significantly higher than that in WT mice (Figure 4h). The expression levels of osteoclast marker genes Nfatc1, Ctsk, Trap, and Mmp9 were significantly increased in WT‐BMMs, which were cocultured with EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ POBs (Figure 4i–l). This significant increasing pattern of these osteoclast differentiation markers was unaffected by the BMM genotype (data not shown). Collectively, these results indicated that the Fgfr2 S252W mutation in osteoblasts increased osteoblast‐mediated osteoclast activity in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice by a secondary coupling effect of activated osteoblasts.

Figure 4.

Abnormally enhanced osteoclast formation and activity in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice are attributed to abnormal osteoblast differentiation. (a) Osteoclast identification by tartrate‐resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining. Bone marrow‐derived macrophages (BMMs) isolated from wild‐type (WT) and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice were differentiated into osteoclasts in the presence of CSF1 (20 ng/ml) and receptor activator of nuclear factor‐κB ligand (RANKL) (80 ng/ml) for 5 days (scale bar: 100 μm). (b) Number of TRAP‐positive osteoclasts with more than three nuclei (n = 5 in each group). (c, d) Messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 measured by quantitative real‐time PCR (qPCR) analysis of WT BMMs isolated from the spleen (c) and bone marrow (d). BMMs from the spleen were cultured in osteoclast differentiation medium for each indicated day and BMMs from bone marrow were cultured for 6 days. Relative mRNA expression was normalized to Gapdh expression. (e) ERK phosphorylation of WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2S252W/+ mice BMMs from bone marrow. BMMs were differentiated into osteoclasts in osteoclast differentiation medium for 5 days. (f, g) TRAP staining of BMMs from WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice cocultured with primary calvaria osteoblasts (OBs) from WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice, respectively, for 7 days with vitamin D3 (10 nM) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (1 µM) in osteogenic medium for osteoclast differentiation (scale bar: 100 μm). (h) Number of TRAP‐positive osteoclasts. (i–l) Primary calvarial OBs of WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ were cocultured with WT BMMs and mRNA levels of osteoclast marker genes were determined by reverse‐transcription (RT) quantitative PCR (qPCR). Data are expressed as the mean ± SE. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. NS, not significant

3.5. Enhanced RANKL expression in osteoblasts of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice contributes to the increases in RANKL‐mediated osteoclast activation and bone loss

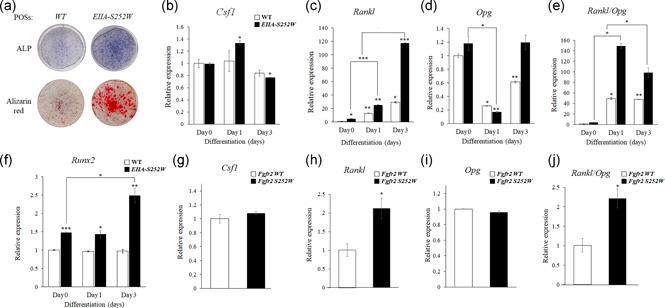

Previous reports show that the FGF signaling pathway is important for osteoblast differentiation, and that the Fgfr2 S252W mutation induces hyperactivation of the FGF signaling pathway and excessive differentiation of osteoblasts (Kim H. J. et al., 2003; Shin et al., 2018; Yoon W. J. et al., 2014). Concordantly, EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ POBs had enhanced production of mineralized matrix compared with WT POBs as shown by alizarin red staining (Figure 5a). M‐CSF, RANKL, and osteoprotegerin (OPG), which is expressed in osteoblasts, are essential signaling molecules for osteoclastogenesis (Al‐Bari & Al Mamun, 2020; Yoon H. et al., 2021). To examine the molecular mechanism by which the Fgfr2 S252W mutation in osteoblasts promoted osteoclast formation in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice, we measured the expression levels of these important osteoblast‐mediated osteoclast activation genes in POBs at various differentiation days. The level of Rankl (Figure 5c) was significantly increased in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ POBs compared with WT POBs. In particular, on differentiation Day 3, the expression level of Rankl was increased by almost fourfold (Figure 5c). However, the expression level of Csf1 (Figure 5b) in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ POBs was similar to that in WT POBs and the expression level of Opg (Figure 5d) was increased by about twofold in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ POBs on differentiation Day 3. Owing to the high expression of Rankl, the Rankl/Opg ratio was significantly increased in POBs of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice compared with WT mice (Figure 5e). As RUNX2 drives Rankl expression at the transcription level in osteoblasts (Enomoto et al., 2003; Mori et al., 2006), we examined the Runx2 expression level and found that Runx2 expression was also significantly increased in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ POBs (Figure 5f). Consistently, forced overexpression of Fgfr2 S252W in MC3T3‐E1 cells also increased the Rankl/Opg ratio by upregulation of Rankl expression compared with Fgfr2 WT cells (Figure 5g–j). Collectively, the Fgfr2 S252W mutation stimulated Runx2 expression in POBs, which in turn induced Rankl expression and secretion from POBs, thereby enhancing osteoblast‐mediated osteoclast activation in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice.

Figure 5.

Imbalanced Rankl/Opg expression due to enhanced Rankl expression in osteoblasts increases osteoclast formation in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice. (a) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and alizarin red staining were performed in wild‐type (WT) and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ primary calvaria osteoblasts (OBs) treated with osteogenic medium for 5 days and 2 weeks. (b–d) Relative mRNA expression of osteoclast differentiation factors in WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ primary calvaria OBs treated with or without (0 day) osteogenic medium for each indicated day as determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR). (e) Relative Rankl/Opg ratio. (f) mRNA level of Runx2 in WT and EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ primary calvaria OBs cultured in osteogenic medium. Cells were collected and analyzed by reverse‐transcription (RT)‐qPCR after treatment for 1 or 3 days with or without osteogenic medium. (g–i) Expression levels of osteoclast differentiation‐regulating genes in MC3T3‐E1 cells as measured by RT‐qPCR after transfection of Fgfr2 WT or S252W plasmids. (j) Graph of the relative Rankl/Opg ratio

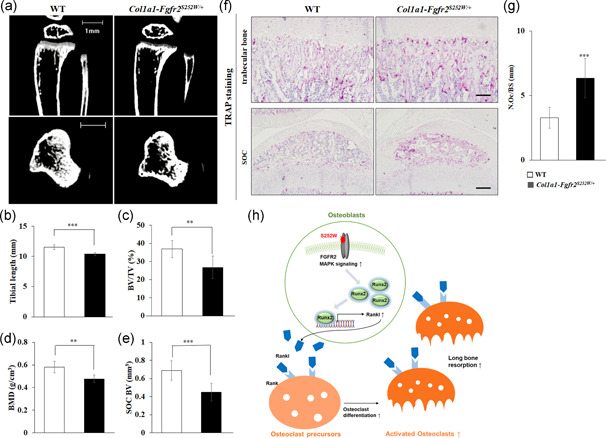

3.6. Col1a1‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice also have a decrease in bone mass and excessive activity of osteoclasts

To confirm whether the Fgfr2 S252W mutation in osteoblasts caused abnormal long bone growth through an increase in osteoblast‐mediated osteoclast activation in the in vivo model, Fgfr2 S252W/+ conditional knock‐in mice were crossed with mice that expressed Col1a1‐cre in mature osteoblasts (referred to as “Col1a1‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ ”) (Baek et al., 2009; Kim B. S. et al., 2021). Similar to the results of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice shown in Figure 1, micro‐CT images of the proximal tibia of Col1a1‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice at P21 showed a significant reduction in the BV compared with WT mice (Figure 6a). Bone morphometric analysis revealed that Col1a1‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice had significant decreases in the tibial length, BV/TV, and BMD similarly to EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (Figure 6b–d). Col1a1‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice also exhibited a reduction in the SOC BV similarly to EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (Figure 6e). Notably, we found a significant increase of TRAP‐positive osteoclasts in the trabecular bone and SOC of Col1a1‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (Figure 6f). Quantitative analysis showed that the number of osteoclasts was significantly increased in Col1a1‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice compared with WT mice (Figure 6g). Taken together, these results demonstrated that the mature osteoblast‐specific Fgfr2 S252W mutation decreased the bone mass in the proximal tibia through excessively enhanced osteoblast‐mediated osteoclast activation.

Figure 6.

Increased osteoblast‐mediated osteoclast activation and reduced bone formation in tibia trabecular bones of Col1a1‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice. (a) Representative micro‐computed tomography (CT) images of the tibial growth plate at postnatal Day 21 (P21) in midsagittal and coronal views are shown for each genotype. (n ≥ 8, scale bar: 1 mm). (b–e) Histomorphometric analyses of three‐dimensional (3D) micro‐CT data. (f) Tartrate‐resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)‐positive osteoclasts as determined by TRAP staining of trabecular bone and secondary ossification center (SOC) of proximal tibiae in P21 wild‐type (WT) and Col1a1‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (n = 3, scale bars: top, 200 μm; bottom, 100 μm). (g) Graph of the number of osteoclasts per bone surface. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (h) Mechanisms of reduced long bone growth in Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice

4. DISCUSSION

RANKL, OPG, and M‐CSF produced in osteoblasts are important regulators of osteoclast differentiation, bone resorption, and bone remodeling (Charles & Aliprantis, 2014; Tanaka et al., 2005; Yoon H. et al., 2021). Interestingly, the present study showed that the expression level of Rankl was significantly increased, while Opg and M‐csf mRNA levels were not significantly changed in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ POBs compared with WT POBs (Figure 5c), which indicated that Rankl was responsible for the osteoblast–osteoclast interaction as an osteoblast‐derived coupling factor in these mutant mice. FGF2 stimulates Rankl expression in osteoblasts to regulate osteoclast differentiation (Chikazu et al., 2001; Kawaguchi et al., 2000) and activation of FGF/FGFR signaling strongly stimulates Runx2 expression in osteoblasts, which promotes osteoblast differentiation (Kim H. J. et al., 2003; Shin et al., 2018). The present study also showed that the mRNA level of Runx2 was significantly enhanced in Fgfr2 S252W/+ POBs (Figure 5f). Putative RUNX2‐binding sites are located in the Rankl gene promoter region (Kitazawa et al., 1999; Mori et al., 2006) and Runx2‐deficient mice completely lack osteoclasts because of diminished RANKL expression (Enomoto et al., 2003). Taken together, although we did not find this hierarchical regulation of FGFR2‐Runx2‐Rankl directly in this study, our results indicated that the FGFR2 S252W mutation markedly increased Rankl expression via excessive Runx2 expression in osteoblasts of these mutant mice, which induced abnormally increased Rankl‐ mediated osteoclast activation (Figure 6h). On the basis of our present study, RANKL‐targeted therapies may be proposed to treat Apert syndrome disorders relevant to osteoclast‐mediated bone loss. Denosumab, which is a fully human monoclonal antibody directed against RANKL and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with a high fracture risk (Dore, 2011; Schwarz & Ritchlin, 2007; Scott & Muir, 2011), may be of great therapeutic value for the treatment of Apert syndrome patients with long bone growth disorders. Therefore, further studies of Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice are needed to verify the potential of RANKL‐targeted therapies to alleviate the symptoms of Apert syndrome.

Bone homeostasis is maintained by the balance between the two main processes of bone remodeling: bone resorption by osteoclasts and bone formation by osteoblasts (Charles & Aliprantis, 2014; Mohamed, 2008; Tanaka et al., 2005). Remodeling is a coordinated process that occurs continuously and repeatedly with bone resorption by osteoclasts for 2–4 weeks and bone formation by osteoblasts for 4 months (Tanaka et al., 2005). As the rate of bone resorption by osteoclasts is faster than that of bone formation, bone mass is generally lost when both processes are activated together (Tanaka et al., 2005). FGFs and FGFRs act as essential regulators in a spatiotemporal‐dependent manner at all stages of skeletal development (Ornitz & Marie, 2015). In particular, a previous report has shown that activation of FGFR2 promotes osteoblast differentiation (Ornitz & Marie, 2015). FGF18 is an essential autocrine‐positive regulator of osteogenic differentiation mediated by FGFR2 activation (Hamidouche et al., 2010; Jeon et al., 2012). Genetic studies in mice have demonstrated that Fgfr2‐lacking mice display defective osteogenesis (Yu et al., 2003). In addition, constitutive activation of Fgfr2 signaling caused by the S252W mutation promotes expression of bone marker genes in human osteoblasts (Lemonnier et al., 2001; Lomri et al., 1998; Tanimoto et al., 2004). Our data also showed that osteoblast differentiation was significantly enhanced in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ POBs compared with WT POBs as shown by alkaline phosphatase and alizarin red S staining (Figure 5a). However, although Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice showed accelerated osteogenic differentiation of POBs, their long bones were much shorter than those of WT mice (Figure 1). This discrepancy appeared to be caused by impairment of the cooperation of complex regulatory crosstalk between osteoclasts and osteoblasts during bone remodeling in these mutant mice. The excessive Rankl expression mediated through RUNX2 activation by constitutively active FGFR2 signaling in osteoblasts also accelerated osteoblast‐mediated osteoclast activation in long bones of EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (Figures 3, 4, 5). In these mutant mice, both bone formation and resorption were activated and the balance shifted towards bone resorption, which reduced the bone mass and shortened the bone length.

FGFR3 is expressed prominently in proliferating and prehypertrophic chondrocytes in the growth plate, and STAT1, ERK1/2, and p38 intracellular signaling through FGFR3 activates downstream genes, such as p107, p21, and Sox9, which regulate chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation into hypertrophic chondrocytes (Ornitz & Marie, 2015). Achondroplasia is the most common form of skeletal dwarfism in humans and ≥97% of cases result from an autosomal dominant missense mutation in FGFR3 (Segev et al., 2000; Su et al., 2010). In achondroplasia, the hypertrophic zone is reduced by shortened chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation (Naski & Colvin, Coffin, et al., 1998; Ornitz & Marie, 2002). However, EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice had decreases in long bone lengths and BMD without apparent defects in chondrocyte proliferation or differentiation (Figure 2). FGFR2 is expressed very weakly in resting, proliferating, and erosive zones of the growth plate (Rice et al., 2003). Mice with a conditionally inactivated Fgfr2 gene in limb bud mesenchyme (Fgfr2 cko ) have reduced postnatal growth, but no effects on chondrocyte proliferation or the length of the proliferating chondrocyte zone (Yu et al., 2003). These results indicate that FGFR2 and FGFR3 have cell type‐specific expression patterns and functions in the bone. Consistent with our current osteoclast findings (Figure 3), a previous in vivo study has suggested that greater osteoclast activity in the metaphysis results in smaller bone formation and, consequently, a shorter trabecular bone (Quinn et al., 2008). In addition, the reduced stature and limbs of Fgfr2 cko mice are attributed to decreased osteogenesis and increased osteoclast activity at the metaphysis (Yu et al., 2003). A previous report has also shown an increase in TRAP‐positive osteoclasts in the mandibular bone of Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice compared with WT mice (Zhou et al., 2013). Thus, on the basis of these results, in this study, we reported that constitutive activation of FGFR2 in EIIA‐Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice reduce the length of limbs through accelerated osteoblast differentiation‐coupled enhancement of osteoclast activation in the metaphysis without altering chondrocyte differentiation in the epiphyseal growth plate.

In our previous study, we have shown the increased hypertrophy of nasal septal chondrocytes in the above mentioned Apert syndrome model mice (Kim B. S. et al., 2021). Although a small part of septal cartilage adjacent to ethmoid or nasal bones undergoes endochondral ossification, the main body of the nasal septum continues to remain as a cartilage throughout a lifespan (Wealthall & Herring, 2006). The hypertrophic change of chondrocytes that we observed was in the main body of the nasal septum and did not progress to endochondral ossification. The discrepancies of chondrocyte hypertrophy in the nasal septum and the long bone epiphysis probably occurred due to their different developmental origin (Gilbert, 2000) or a different developmental fate of tissue that caused the chondrocytes to respond differently from the activated FGFR2 signaling. Nevertheless, as the endochondral ossification process is critical for longitudinal bone growth (Segev et al., 2000), and as the abnormal proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes in the growth plate in the Apert syndrome model mice were reported in previous studies (Chen et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2005), the possibility of abnormal endochondral ossification cannot be ruled out completely.

During this process, a primary ossification center (POC) is formed within the diaphysis and an SOC within the epiphysis (Xie & Chagin, 2021). The process that regulates POC formation has been well investigated, whereas the signaling pathways as well as the systemic and local factors that regulate establishment of the SOC and the role of SOC in longitudinal bone growth are unclear. In the present study, we observed that a reduced SOC BV was highly correlated with a shortened tibia length in Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice (Figure 1k,l). Anatomically, the SOC separates the articular cartilage from the growth plate cartilage, which provides several advantages in connection with formation of the epiphysis, including flexibility for the growth plate cartilage to take a shape that allows proper arrangement of trabeculae (Xie & Chagin, 2021). Therefore, although not revealed in this study, our results on the high correlation between the SOC and length of long bones provide insights to explain another mechanism for limb‐shortening symptoms in Fgfr2 S252W/+ mice and patients with Apert syndrome.

In conclusion, the present study shows that activating mutation Fgfr2 S252W decreases the long bone length and BMD by elevating osteoclast activity stimulated by Rankl expression in osteoblasts (Figure 6h). Furthermore, genetic and functional studies revealed how activated FGFR2 signaling in osteoblasts affects postnatal bone homeostasis in long bones. For new therapeutic approaches that target these regulatory processes, further studies are needed to gain an integrated understanding of the bone formation and bone resorption status in Apert syndrome of other bone tissues such as calvaria, midface, and vertebral bones.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Hye‐Rim Shin contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. Bong‐Soo Kim contributed to conception, design, data analysis, and interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. Hyun‐Jung Kim contributed to design, data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Woo‐Jin Kim and Heein Yoon contributed to conception and data interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. Je‐Yong Choi contributed to critical revision of the manuscript and kindly provided Col1a1‐Cre transgenic mice. Hyun‐Mo Ryoo contributed to conception, design, data analysis, and interpretation, and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF). Hyun‐Mo Ryoo (2020R1A4A1019423 and 2020R1A2B5B02002658) and Woo‐Jin Kim (NRF‐2019R1C1C1003669) were funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT. Hye‐Rim Shin (NRF‐2018R1A6A3A01012572) was funded by the Ministry of Education. We thank Mitchell Arico from Edanz (https://www.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Shin, H.‐R. , Kim, B.‐S. , Kim, H.‐J. , Yoon, H. , Kim, W.‐J. , Choi, J.‐Y. , & Ryoo, H.‐M. (2022). Excessive osteoclast activation by osteoblast paracrine factor RANKL is a major cause of the abnormal long bone phenotype in Apert syndrome model mice. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 237, 2155–2168. 10.1002/jcp.30682

REFERENCES

- Al‐Bari, A. A. , & Al Mamun, A. (2020). Current advances in regulation of bone homeostasis. FASEB Bioadvances, 2(11), 668–679. 10.1096/fba.2020-00058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J. , Burns, H. D. , Enriquez‐Harris, P. , Wilkie, A. O. , & Heath, J. K. (1998). Apert syndrome mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 exhibit increased affinity for FGF ligand. Human Molecular Genetics, 7(9), 1475–1483. 10.1093/hmg/7.9.1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek, W. Y. , Lee, M. A. , Jung, J. W. , Kim, S. Y. , Akiyama, H. , de Crombrugghe, B. , & Kim, J. E. (2009). Positive regulation of adult bone formation by osteoblast‐specific transcription factor osterix. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 24(6), 1055–1065. 10.1359/jbmr.081248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto, J. A. , Evans, R. D. , Hayward, R. D. , & Jones, B. M. (2001). From genotype to phenotype: the differential expression of FGF, FGFR, and TGFbeta genes characterizes human cranioskeletal development and reflects clinical presentation in FGFR syndromes. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 108(7), 2026–2039. Discussion 2040‐2026 10.1097/00006534-200112000-00030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles, J. F. , & Aliprantis, A. O. (2014). Osteoclasts: More than 'bone eaters'. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 20(8), 449–459. 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P. , Zhang, L. , Weng, T. , Zhang, S. , Sun, S. , Chang, M. , Li, Y. , Zhang, B. , & Zhang, L. (2014). A Ser252Trp mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) mimicking human Apert syndrome reveals an essential role for FGF signaling in the regulation of endochondral bone formation. PLoS ONE, 9(1), e87311. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikazu, D. , Katagiri, M. , Ogasawara, T. , Ogata, N. , Shimoaka, T. , Takato, T. , Nakamura, K. , & Kawaguchi, H. (2001). Regulation of osteoclast differentiation by fibroblast growth factor 2: Stimulation of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand/osteoclast differentiation factor expression in osteoblasts and inhibition of macrophage colony‐stimulating factor function in osteoclast precursors. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 16(11), 2074–2081. 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.11.2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M. M., Jr. , Kreiborg, S. (1993). Skeletal abnormalities in the Apert syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 47(5), 624–632. 10.1002/ajmg.1320470509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutu, D. L. , Francois, M. , & Galipeau, J. (2011). Inhibition of cellular senescence by developmentally regulated FGF receptors in mesenchymal stem cells. Blood, 117(25), 6801–6812. 10.1182/blood-2010-12-321539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, C. M. , Quarto, N. , Warren, S. M. , Salim, A. , & Longaker, M. T. (2003). Age‐related changes in the biomolecular mechanisms of calvarial osteoblast biology affect fibroblast growth factor‐2 signaling and osteogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(34), 32005–32013. 10.1074/jbc.M304698200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeizel, A. E. , Elek, C. , & Susanszky, E. (1993). Birth prevalence study of the Apert syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 45(3), 392–393. 10.1002/ajmg.1320450322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore, R. K. (2011). The RANKL pathway and denosumab. Rheumatic Diseases Clinics of North America, 37(3), 433–452. vi–vii 10.1016/j.rdc.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto, H. , Shiojiri, S. , Hoshi, K. , Furuichi, T. , Fukuyama, R. , Yoshida, C. A. , Kanatani, N. , Nakamura, R. , Mizuno, A. , Zanma, A. , Yano, K. , Yasuda, H. , Higashio, K. , Takada, K. , & Komori, T. (2003). Induction of osteoclast differentiation by Runx2 through receptor activator of nuclear factor‐kappa B ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin regulation and partial rescue of osteoclastogenesis in Runx2−/− mice by RANKL transgene. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(26), 23971–23977. 10.1074/jbc.M302457200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, S. F. (2000). Developmental biology. Osteogenesis: The development of bones (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10056 [Google Scholar]

- Hamidouche, Z. , Fromigue, O. , Nuber, U. , Vaudin, P. , Pages, J. C. , Ebert, R. , Jakob, F. , Miraoui, H. , & Marie, P. J. (2010). Autocrine fibroblast growth factor 18 mediates dexamethasone‐induced osteogenic differentiation of murine mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 224(2), 509–515. 10.1002/jcp.22152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, X. , Xiao, Z. , & Quarles, L. D. (2015). Membrane and integrative nuclear fibroblastic growth factor receptor (FGFR) regulation of FGF‐23. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 290(16), 10447–10459. 10.1074/jbc.M114.609230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahimi, O. A. , Zhang, F. , Eliseenkova, A. V. , Itoh, N. , Linhardt, R. J. , & Mohammadi, M. (2004). Biochemical analysis of pathogenic ligand‐dependent FGFR2 mutations suggests distinct pathophysiological mechanisms for craniofacial and limb abnormalities. Human Molecular Genetics, 13(19), 2313–2324. 10.1093/hmg/ddh235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, A. L. , Smith, C. , Partanen, J. , & Ornitz, D. M. (2006). Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 signaling in the osteo‐chondrogenic cell lineage regulates sequential steps of osteoblast maturation. Developmental Biology, 296(2), 315–328. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, E. , Yun, Y. R. , Kang, W. , Lee, S. , Koh, Y. H. , Kim, H. W. , Suh, C. K. , & Jang, J. H. (2012). Investigating the role of FGF18 in the cultivation and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS ONE, 7(8), e43982. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. , & Wilkie, A. O. (2011). Craniosynostosis. European Journal of Human Genetics, 19(4), 369–376. 10.1038/ejhg.2010.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi, H. , Chikazu, D. , Nakamura, K. , Kumegawa, M. , & Hakeda, Y. (2000). Direct and indirect actions of fibroblast growth factor 2 on osteoclastic bone resorption in cultures. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 15(3), 466–473. 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.3.466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B. , Shin, H. , Kim, W. , Kim, H. , Cho, Y. , Yoon, H. , Baek, J. , Woo, K. , Lee, Y. , & Ryoo, H. (2020). PIN1 attenuation improves midface hypoplasia in a mouse model of Apert syndrome. Journal of Dental Research, 99(2), 223–232. 10.1177/0022034519893656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B. S. , Shin, H. R. , Kim, H. J. , Yoon, H. , Cho, Y. D. , Choi, K. Y. , Choi, J. Y. , Kim, W. J. , & Ryoo, H. M. (2021). Septal chondrocyte hypertrophy contributes to midface deformity in a mouse model of Apert syndrome. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 7979. 10.1038/s41598-021-87260-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. J. , Kim, J. H. , Bae, S. C. , Choi, J. Y. , Kim, H. J. , & Ryoo, H. M. (2003). The protein kinase C pathway plays a central role in the fibroblast growth factor‐stimulated expression and transactivation activity of Runx2. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(1), 319–326. 10.1074/jbc.M203750200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. J. , Kim, W. J. , & Ryoo, H. M. (2020). Post‐translational regulations of transcriptional activity of RUNX2. Molecules and Cells, 43(2), 160–167. 10.14348/molcells.2019.0247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W. J. , Shin, H. L. , Kim, B. S. , Kim, H. J. , & Ryoo, H. M. (2020). RUNX2‐modifying enzymes: therapeutic targets for bone diseases. Experimental and Molecular Medicine, 52(8), 1178–1184. 10.1038/s12276-020-0471-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa, R. , Kitazawa, S. , & Maeda, S. (1999). Promoter structure of mouse RANKL/TRANCE/OPGL/ODF gene. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta/General Subjects, 1445(1), 134–141. 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00032-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier, J. , Hay, E. , Delannoy, P. , Lomri, A. , Modrowski, D. , Caverzasio, J. , & Marie, P. J. (2001). Role of N‐cadherin and protein kinase C in osteoblast gene activation induced by the S252W fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 mutation in Apert craniosynostosis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 16(5), 832–845. 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.5.832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomri, A. , Lemonnier, J. , Hott, M. , de Parseval, N. , Lajeunie, E. , Munnich, A. , Renier, D. , & Marie, P. J. (1998). Increased calvaria cell differentiation and bone matrix formation induced by fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 mutations in Apert syndrome. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 101(6), 1310–1317. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9502772 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A. M. (2008). An overview of bone cells and their regulating factors of differentiation. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS, 15(1), 4–12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22589609 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molteni, A. , Modrowski, D. , Hott, M. , & Marie, P. J. (1999). Differential expression of fibroblast growth factor receptor‐1, ‐2, and ‐3 and syndecan‐1, ‐2, and ‐4 in neonatal rat mandibular condyle and calvaria during osteogenic differentiation in vitro. Bone, 24(4), 337–347. 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00191-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, K. , Kitazawa, R. , Kondo, T. , Maeda, S. , Yamaguchi, A. , & Kitazawa, S. (2006). Modulation of mouse RANKL gene expression by Runx2 and PKA pathway. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 98(6), 1629–1644. 10.1002/jcb.20891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita, J. , Nakamura, M. , Kobayashi, Y. , Deng, C. X. , Funato, N. , & Moriyama, K. (2014). Soluble form of FGFR2 with S252W partially prevents craniosynostosis of the apert mouse model. Developmental Dynamics, 243(4), 560–567. 10.1002/dvdy.24099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naski, M. C. , Colvin, J. S. , Coffin, J. D. , & Ornitz, D. M. (1998). Repression of hedgehog signaling and BMP4 expression in growth plate cartilage by fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Development, 125(24), 4977–4988. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9811582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naski, M. C. , & Ornitz, D. M. (1998). FGF signaling in skeletal development. Frontiers in Bioscience, 3, d781–d794. 10.2741/a321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohbayashi, N. , Shibayama, M. , Kurotaki, Y. , Imanishi, M. , Fujimori, T. , Itoh, N. , & Takada, S. (2002). FGF18 is required for normal cell proliferation and differentiation during osteogenesis and chondrogenesis. Genes and Development, 16(7), 870–879. 10.1101/gad.965702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz, D. M. , & Itoh, N. (2001). Fibroblast growth factors. Genome Biology, 2(3), reviews3005.1. 10.1186/gb-2001-2-3-reviews3005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz, D. M. , & Marie, P. J. (2002). FGF signaling pathways in endochondral and intramembranous bone development and human genetic disease. Genes and Development, 16(12), 1446–1465. 10.1101/gad.990702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz, D. M. , & Marie, P. J. (2015). Fibroblast growth factor signaling in skeletal development and disease. Genes and Development, 29(14), 1463–1486. 10.1101/gad.266551.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz, D. M. , Xu, J. , Colvin, J. S. , McEwen, D. G. , MacArthur, C. A. , Coulier, F. , Gao, G. , & Goldfarb, M. (1996). Receptor specificity of the fibroblast growth factor family. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 271(25), 15292–15297. 10.1074/jbc.271.25.15292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, O. J. , Kim, H. J. , Woo, K. M. , Baek, J. H. , & Ryoo, H. M. (2010). FGF2‐activated ERK mitogen‐activated protein kinase enhances Runx2 acetylation and stabilization. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 285(6), 3568–3574. 10.1074/jbc.M109.055053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, J. M. , Sims, N. A. , Saleh, H. , Mirosa, D. , Thompson, K. , Bouralexis, S. , Walker, E. C. , Martin, T. J. , & Gillespie, M. T. (2008). IL‐23 inhibits osteoclastogenesis indirectly through lymphocytes and is required for the maintenance of bone mass in mice. Journal of Immunology, 181(8), 5720–5729. 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, D. P. , Rice, R. , & Thesleff, I. (2003). Fgfr mRNA isoforms in craniofacial bone development. Bone, 33(1), 14–27. 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00163-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D. , Hasharoni, A. , Cohen, N. , Yayon, A. , Moskowitz, R. M. , & Nevo, Z. (1999). Fibroblast growth factor receptor‐3 as a marker for precartilaginous stem cells. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 367(Suppl), S163–S175. 10.1097/00003086-199910001-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, E. M. , & Ritchlin, C. T. (2007). Clinical development of anti‐RANKL therapy. Arthritis Research and Therapy, 9(Suppl 1), S7. 10.1186/ar2171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, L. J. , & Muir, V. J. (2011). Denosumab in the prevention of skeletal‐related events in patients with bone metastases from solid tumors: profile report. BioDrugs, 25(6), 397–400. 10.2165/11207650-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev, O. , Chumakov, I. , Nevo, Z. , Givol, D. , Madar‐Shapiro, L. , Sheinin, Y. , Weinreb, M. , & Yayon, A. (2000). Restrained chondrocyte proliferation and maturation with abnormal growth plate vascularization and ossification in human FGFR‐3(G380R) transgenic mice. Human Molecular Genetics, 9(2), 249–258. 10.1093/hmg/9.2.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H. R. , Bae, H. S. , Kim, B. S. , Yoon, H. I. , Cho, Y. D. , Kim, W. J. , Choi, K. Y. , Lee, Y. S. , Woo, K. M. , Baek, J. H. , & Ryoo, H. M. (2018). PIN1 is a new therapeutic target of craniosynostosis. Human Molecular Genetics, 27(22), 3827–3839. 10.1093/hmg/ddy252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, V. , Coumoul, X. , Wang, R. H. , Kim, H. S. , & Deng, C. X. (2007). RNA interference and inhibition of MEK‐ERK signaling prevent abnormal skeletal phenotypes in a mouse model of craniosynostosis. Nature Genetics, 39(9), 1145–1150. 10.1038/ng2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, N. , Sun, Q. , Li, C. , Lu, X. , Qi, H. , Chen, S. , Yang, J. , Du, X. , Zhao, L. , He, Q. , Jin, M. , Shen, Y. , Chen, D. , & Chen, L. (2010). Gain‐of‐function mutation in FGFR3 in mice leads to decreased bone mass by affecting both osteoblastogenesis and osteoclastogenesis. Human Molecular Genetics, 19(7), 1199–1210. 10.1093/hmg/ddp590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto, K. , Miyata, Y. , Nakayama, T. , Saito, S. , Suzuki, R. , Hayakawa, F. , Nishiwaki, S. , Mizuno, H. , Takeshita, K. , Kato, H. , Ueda, R. , Takami, A. , & Naoe, T. (2016). Fibroblast Growth Factor‐2 facilitates the growth and chemo‐resistance of leukemia cells in the bone marrow by modulating osteoblast functions. Scientific Reports, 6, 30779. 10.1038/srep30779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y. , Nakayamada, S. , & Okada, Y. (2005). Osteoblasts and osteoclasts in bone remodeling and inflammation. Current Drug Targets Inflammation and Allergy, 4(3), 325–328. 10.2174/1568010054022015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J. , Xie, J. , Chen, W. , Tang, C. , Wu, J. , Wang, Y. , Zhou, X. D. , Zhou, H. D. , & Li, Y. P. (2020). Runt‐related transcription factor 1 is required for murine osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 295(33), 11669–11681. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto, Y. , Yokozeki, M. , Hiura, K. , Matsumoto, K. , Nakanishi, H. , Matsumoto, T. , Marie, P. J. , & Moriyama, K. (2004). A soluble form of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) with S252W mutation acts as an efficient inhibitor for the enhanced osteoblastic differentiation caused by FGFR2 activation in Apert syndrome. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 279(44), 45926–45934. 10.1074/jbc.M404824200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushijima, T. , Okazaki, K. , Tsushima, H. , & Iwamoto, Y. (2014). CCAAT/enhancer‐binding protein beta regulates the repression of type II collagen expression during the differentiation from proliferative to hypertrophic chondrocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(5), 2852–2863. 10.1074/jbc.M113.492843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. , Xiao, R. , Yang, F. , Karim, B. O. , Iacovelli, A. J. , Cai, J. , Lerner, C. P. , Richtsmeier, J. T. , Leszl, J. M. , Hill, C. A. , Yu, K. , Ornitz, D. M. , Elisseeff, J. , Huso, D. L. , & Jabs, E. W. (2005). Abnormalities in cartilage and bone development in the Apert syndrome FGFR2(+/S252W) mouse. Development, 132(15), 3537–3548. 10.1242/dev.01914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wealthall, R. J. , & Herring, S. W. (2006). Endochondral ossification of the mouse nasal septum. The Anatomical Record. Part A, Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology, 288(11), 1163–1172. 10.1002/ar.a.20385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng, T. , Yi, L. , Huang, J. , Luo, F. , Wen, X. , Du, X. , Chen, Q. , Deng, C. , Chen, D. , & Chen, L. (2012). Genetic inhibition of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 in knee cartilage attenuates the degeneration of articular cartilage in adult mice. Arthtitis and Rheumatism, 64(12), 3982–3992. 10.1002/art.34645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie, A. O. (1997). Craniosynostosis: Genes and mechanisms. Human Molecular Genetics, 6(10), 1647–1656. 10.1093/hmg/6.10.1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M. , & Chagin, A. S. (2021). The epiphyseal secondary ossification center: Evolution, development and function. Bone, 142, 115701. 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D. , Chen, D. , Cool, S. M. , van Wijnen, A. J. , Mikecz, K. , Murphy, G. , & Im, H. J. (2011). Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is principally responsible for fibroblast growth factor 2‐induced catabolic activities in human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Research and Therapy, 13(4), R130. 10.1186/ar3441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Yoon, H. , Kim, H. J. , Shin, H. R. , Kim, B. S. , Kim, W. J. , Cho, Y. D. , & Ryoo, H. M. (2021). Nicotinamide improves delayed tooth eruption in Runx2(+/−) mice. Journal of Dental Research, 100(4), 423–431. 10.1177/0022034520970471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, K. A. , Son, Y. , Choi, Y. J. , Kim, J. H. , & Cho, J. Y. (2017). Fibroblast growth factor 2 supports osteoblastic niche cells during hematopoietic homeostasis recovery after bone marrow suppression. Cell Communication and Signaling, 15(1), 25. 10.1186/s12964-017-0181-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, W. J. , Cho, Y. D. , Kim, W. J. , Bae, H. S. , Islam, R. , Woo, K. M. , Baek, J. H. , Bae, S. C. , & Ryoo, H. M. (2014). Prolyl isomerase Pin1‐mediated conformational change and subnuclear focal accumulation of Runx2 are crucial for fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2)‐induced osteoblast differentiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(13), 8828–8838. 10.1074/jbc.M113.516237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K. , Xu, J. , Liu, Z. , Sosic, D. , Shao, J. , Olson, E. N. , Towler, D. A. , & Ornitz, D. M. (2003). Conditional inactivation of FGF receptor 2 reveals an essential role for FGF signaling in the regulation of osteoblast function and bone growth. Development, 130(13), 3063–3074. 10.1242/dev.00491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. , Pu, D. , Liu, R. , Li, X. , Wen, X. , Zhang, L. , Chen, L. , Deng, M. , & Liu, L. (2013). The Fgfr2(S252W/+) mutation in mice retards mandible formation and reduces bone mass as in human Apert syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A, 161A(5), 983–992. 10.1002/ajmg.a.35824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]