Abstract

BACKGROUND

The Varroa mite (Varroa destructor) is an ectoparasite that can affect the health of honey bees (Apis mellifera) and contributes to the loss of colony productivity. The limited availability of Varroacides with different modes of action in Canada has resulted in the development of chemical resistance in mite populations. Therefore, an urgent need to evaluate new potential miticides that are safe for bees and exhibit high efficacy against Varroa exists. In this study, the acute contact toxicity of 26 active ingredients (19 chemical classes), already available on the market, was evaluated on V. destructor and A. mellifera under laboratory conditions using an apiarium bioassay. In this assay, groups of Varroa‐infested worker bees were exposed to different dilutions of candidate compounds. In semi‐field trials, Varroa‐infested honey bees were randomly treated with four vetted candidate compounds from the apiarium assay in mini‐colonies.

RESULTS

Among tested compounds, fenazaquin (quinazoline class) and fenpyroximate (pyrazole class) had higher mite mortality and lower bee mortality over a 24 h exposure period in apiariums. These two compounds, plus spirotetramat and spirodiclofen, were selected for semi‐field evaluation based on the findings of the apiarium bioassay trials and previous laboratory studies. Consistent with the apiarium bioassay, semi‐field results showed fenazaquin and fenpyroximate had high efficacy (>80%), reducing Varroa abundance by 80% and 68%, respectively.

CONCLUSION

These findings suggest that fenazaquin would be an effective Varroacide, along with fenpyroximate, which was previously registered for in‐hive use as Hivastan. Both compounds have the potential to provide beekeepers with an alternative option for managing Varroa mites in honey bee colonies. © 2022 The Authors. Pest Management Science published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of Society of Chemical Industry.

Keywords: honey bee, Varroa mite, apiarium, fenazaquin, fenpyroximate

Results indicated among 26 tested active ingredients (AIs), fenazaquin and fenpyroximate with high field efficacy (>80%) have the potential to provide beekeeping industry with an alternative option for managing Varroa mites in honey bee colonies.

1. INTRODUCTION

Globally, many species of bees and other insects play an important role in plant pollination. This pollination service is vital to the maintenance of wild plant communities of the world 1 , 2 and agricultural crop productivity. 3 , 4 It is estimated that the value of insect pollination to global agriculture is $845 billion per year. 5 Despite the wide diversity of plant pollinators, the honey bee, Apis mellifera L., is the world's most important managed pollinator of agricultural crops and natural habitats. 6 , 7 Approximately one‐third of food consumed each day relies on pollination, mainly by honey bees. 8 Klein et al. 9 stated that the honey bee's contribution to world food production is indispensable.

Similar to other managed agricultural species, particularly those kept in higher densities than would be seen in the wild, honey bees face a number of challenges for pest and disease management. 10 , 11 , 12 Some maladies left untreated or without management intervention can cause colony mortality. Colony mortality has been associated with Varroa mite, Varroa destructor Anderson and Trueman, 13 , 14 Nosema spp., 15 viruses, 16 , 17 , 18 poor nutrition, 19 and pesticides. 20 , 21 Of the diseases and pests, Varroa have proven to be one of the most common causes of overwinter colony loss in Canada. 22 , 23 Varroa mites feed on mature and immature honey bees, and failure to control high infestations can compromise individual bee health and overall colony viability. Parasitization from Varroa can suppress the normal functionality of many individual honey bee systems, including immune response, 24 protein synthesis, 25 lipid storage, 26 , 27 and pesticide detoxification. 28 At the colony level, Varroa can impede honey bee homeostasis 29 and thermoregulation. 30 Varroa mites are also responsible for vectoring viruses 31 and reducing drone survivorship. 32 Varroa's life history complicates our ability to treat colonies with high infestation, as mites are most vulnerable once they are phoretic. The exponential growth of mite populations becomes apparent in northern climates once honey bee brood production slows down in autumn and mites are forced into the bee cluster. If autumn mite infestation is above 3% (recommended economic threshold for autumn in Canadian Prairies), 33 it will prevent optimum colony performance and can increase colony winter mortality by 40% or more. 22 , 34

Varroa pose a serious challenge to the beekeeping industry and the success of a beekeepers' operation. A variety of management tools is available for Varroa control, including cultural, genetic, and chemical control options. Large‐scale Canadian beekeepers use a variety of chemical miticides to manage Varroa populations, including hard and soft chemicals. Each tool comes with its own challenges and drawbacks, and no one option is a panacea for Varroa control. Due to wide range of efficacy of these tools and demands for certain miticides to apply in bee colonies, beekeepers have become more dependent on the use of highly effective synthetic miticides. This practice of reliance on a single product for a prolonged period has increased rates of resistance and cross‐resistance in Varroa mite populations. Resistance has already been documented in North America, 22 , 35 , 36 South America, 37 and Europe 38 for amitraz, tau‐fluvalinate, and coumaphos, leaving few options for Varroa control moving forward.

With all the challenges associated with the available registered miticides, emerging resistant Varroa populations, and effects on honey bee health, 39 an urgent need exists to find Varroa‐selective miticides with different modes of action (MOAs) as alternative in‐hive treatments. Without new miticides, Varroa treatment failure will contribute to a reduced supply of pollination services and increased colony mortality, jeopardizing beekeepers' livelihoods and the livelihoods of those who depend on pollination services for crop production. To expedite the search for a new Varroacide, it is advantageous to evaluate compounds already used in other agriculture and domestic animal industries. In the case of amitraz, for example, it was originally formulated for use on mammals for the removal of mites and ticks. 40 , 41 , 42 After testing this compound on honey bees and Varroa mites, it was found to be an effective Varroacide and it is now used as the active ingredient (AI) of the in‐hive treatment Apivar. Indeed, there are other miticides with differing MOAs that have already been developed to control mites and ticks in North America that could be screened for use on Varroa. For instance, a variety of miticides have been developed for controlling plant feeding mites (e.g. Tetranychus spp. and Pananychus spp.) under greenhouse and field conditions. These miticides include neurotoxins (organophosphates, pyrethroids, organochlorines, and avermectins), 43 inhibitors of chitin synthesis (oxazolines, thiazolidinones, and tetrazines), 44 , 45 and lipid biosynthesis inhibitors (tetronic acids). 46 Other compounds target the mitochondrial electron transport system (pyrazoles) 47 or affect the mitochondria complex III (quinolines and benzoylacetonitriles). 48 , 49 Many of these chemicals could be added to a Varroa suppression trial as part of a preliminary study for evaluating their efficacy. 50 New candidate miticides included in a screening program for use on Varroa should have the following characteristics: reside in a different chemical class that has commercial products currently available, be fatal to mites and innocuous to bees, leave minimal or no residues in honey or wax, and have no negative effects on colony fitness. These products should not have any cross‐resistance with currently known resistance in the mite population. They must also be safe to the applicators.

Recently, Bahreini et al. 50 screened the 16 active ingredients using the glass vial contact‐based bioassay for mite mortality and bee safety. To move to the next phase of developing new miticides to be used in honey bees, this study was designed to first screen the previously screened 16 compounds 50 and additionally 10 more compounds using the apiarium bioassay 51 where a small cluster bees and mites together, similar to a colony environment. In addition to determining miticide efficacy in this novel laboratory environment, the goal was to see if this method would show comparable results in the field. If successful, the apiarium could be integrated into initial screening trials of new miticides, complementing conventional contact bioassays as a predictor of field efficacy. Second, vetted compounds from the apiarium test and the glass vial test 50 were subjected to a field test using mini‐colonies furnished with Varroa‐infested bees.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

European honey bee (A. mellifera) colonies at the Crop Diversification Center North (CDCN), Edmonton, Alberta, Canada (53.54 °N, 113.49 °W) were used to provide Varroa mites and honey bees in the summer and autumn of 2017–2019. Management practices were implemented to reduce variabilities among V. destructor and A. mellifera populations. 52 The experimental double brood‐chambered colonies were headed by Kona queens (Hawaii, USA) and housed in Langstroth boxes. They were fed sugar syrup and treated, if needed, with Apivar (500 mg of amitraz/strip; Veto Pharma, Palaiseau, France), or oxalic acid and Fumagilin‐B (both from Medivet Pharmaceutical Ltd, High River, AB, Canada) according to manufacturers’ recommendations, and were overwintered outdoors. 53 To determine the Varroa mite infestation level (%) in each experimental colony, the initial mean abundance was evaluated using the alcohol wash method (70% ethanol). 50 Evaluation of mite resistance to Apivar was performed on the colonies before mite collection using an adapted version of the Pettis method. 54 This was done to ensure the mites used in the experiment were susceptible to amitraz, the AI for the Varroacide Apivar, which was used as the positive control. In the resistance test, 24‐h mite mortality was assessed after a group of worker bees were exposed to a piece of Apivar strip. 50 In all laboratory assessments, the temperature (°C) and relative humidity (RH, %) in incubators were monitored using HOBO (Onset Computer Corporation, MA, USA) data loggers.

2.1. Laboratory assessments

2.1.1. Chemical preparation

All AIs were obtained from Sigma‐Aldrich (ON, Canada), except cyflumetofen (Cedarlane, NC, USA) (Table S1). Acetone (784 g mL−1 density; Sigma‐Aldrich) was used as a solvent for all AIs, except for clofentezine where acetonitrile (786 g mL−1 density; Sigma‐Aldrich) was used. On the day of the experiment, fresh stock dilutions were prepared for each AI (10 000 mg L−1 = 1%) in 15‐mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes (VWR, ON, Canada) using acetone or acetonitrile, and agitated on a vortex mixer (VWR) for 2–3 min until homogeneous. A fume hood was used for the preparation of all chemicals and for the duration of the experiment. Operators wore full‐face respirators (6900; 3M, USA) with filters (60 923; 3M) and additional personal protective equipment.

2.1.2. Apiarium bioassay

To determine the simultaneous effect of miticides on honey bees and Varroa, a group of adult worker bees (140.89 ± 6.37) from colonies with high mite infestations were transferred to a custom 800 mL apiarium. 51 A plastic strip (2.54 × 11.43 cm; Recycled Binding Cover, Staples, Canada) coated with one of the experimental AIs was fixed to the top of the apiarium with two sugar cubes on either side for bee food. In total, 19 chemical classes (26 associated AIs) with different MOAs, plus formamidine (amitraz), were tested and evaluated (Table S1). The efficacy of AIs for controlling Varroa mites and the potential lethal effect on worker bees was compared with a positive control (amitraz) and a negative control (no treatment). Three subsequent doses from each AI (n = 27, including amitraz) (0.05 mg/apiarium, 0.5 mg/apiarium or 5 mg/apiarium) were evaluated. All treatment groups including controls had three replicates. After incubating for 24 h (25 ± 1 °C and 60 ± 5% RH, dark), live and dead mites and bees were counted. Suspected dead mites were collected from the bottom of cages using a fine‐tipped paint brush and probed under a magnifying glass to detect subtle limb movement. Mites that were completely motionless and lacked appendage movement when gently probed were considered dead. Bees were determined to be dead if they were laying on the bottom of the cage and completely motionless (i.e. lack of body or extremity movement) when the cage was slightly agitated. After dead bees were counted, cages were placed in a freezer at −20 °C for 2–3 h to kill the remaining live bees. The total number of bees in the sample was counted and they were transferred to a 500‐mL plastic container filled with 70% ethanol. The alcohol wash method was used to determine the remaining live Varroa left on live bees after 24 h. 50 All experimental components in contact with chemicals (bees, mites, all parts of cages, contaminated alcohol) were disposed of appropriately.

2.2. Semi‐field assessments

2.2.1. Chemical preparation

Based on previous laboratory results by Bahreini et al. 50 and the findings of the apiarium in this study, four compounds were selected for semi‐field evaluations. Formulated products (FPs) were used instead of the associated AIs (with the exception of fenazaquin), as more chemical was required to scale up to field testing and there is a higher procurement cost associated with the AIs. The tested FPs and AIs belong to the following chemical families: tetronic acids (spirodiclofen and spirotetramat), pyrazoles (fenpyroximate), and quinazolines (fenazaquin) (Table S1). All the commercial FPs were obtained from Terralink (BC, Canada): Kontos (spirotetramat, 22.4%), Fujimite (fenpyroximate, 5%), and Envidor (spirodiclofen, 24%). The AI fenazaquin was used instead of its associated FP because it was not registered with Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) and is not available in Canada. On the day of in‐hive application, fresh stock dilutions for each FP (10 000 mg L−1 = 1%) and AI (10 000 mg L−1 = 1%) were prepared in 50‐mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes (VWR). The centrifuge tubes were agitated on a vortex mixer for a period of 2–3 min. All chemical preparations took place in a fume hood where operators wore full personal protective equipment.

2.2.2. Mini‐colony assay

Single brood chamber colonies (n = 14) were constructed with three separate compartments (12 × 26 × 48 cm). Each compartment was considered a single mini‐colony with one brood frame, three frames of bees (for a total of three frames/compartment), and a newly mated queen. The origin of the frames and bees in each compartment corresponded to one highly Varroa‐infested colony at CDCN (i.e. mother colony). No frames between mother colonies were mixed for this experiment. All mini‐colonies (n = 42) were randomly assigned to treatments with three replicates. Miticide treatments were applied in three dosage levels: 500 mg AI/mini‐colony, 1000 mg AI/mini‐colony and 1500 mg AI/mini‐colony. FP concentrations were calculated based on their labelled AI guarantee. Three mini‐colonies were left untreated (negative control) and three mini‐colonies were exposed to one strip of Apivar (500 mg amitraz/strip) as the positive control. Substrate strips (2.5 × 20 cm) were inoculated with dilutions of FPs or AIs representing designated dosages. Water and acetone were solvents for the FPs and the AIs, respectively. Prepared strips were air dried at room temperature (2–3 h) in a fume hood in the dark and applied to mini‐colonies the same day. The experiment duration was 42 days, including a 28‐day period for miticide exposure (treatments applied at 7‐day intervals) and a 14‐day post‐treatment period. However, positive control mini‐colonies had one treatment that lasted the duration of the experiment (i.e. one strip of Apivar for 42 days). To determine in‐hive mite mortality, modified sticky traps (35.56 × 40.64 cm; Contech Inc., BC, Canada) were placed under the mini‐colony and changed on the first, second, third, fifth, and seventh days after treatment (five total traps per week). Dead mites were double counted and the daily mite mortality rate (mites/total mites/day) and daily mite drop (mites/day) were calculated.

The mean abundance of Varroa was determined using the alcohol wash method for each mini‐colony before and after treatments. The pre‐ and post‐treatment bee populations were evaluated using visual assessment. The percentage of frames covered with bees was multiplied by 2430 worker bees. 55 To determine the total number of Varroa mites remaining in the mini‐colonies after treatment (28 days), excluding positive controls (Apivar), oxalic acid was used as a finishing treatment. Oxalic acid was applied using the Pro Vap 110 (OxoVap LLC, SC, USA) with modified application: 1 g per mini‐colony, two treatments, 7‐day interval between treatments. Sticky traps were also used to determine the mite drop during oxalic acid treatment. Dead mites were double counted and the remaining post‐treatment mites in the bee cluster were calculated.

2.3. Statistical analyses

The variables for mite and bee mortality rates (%) were analyzed using a mixed model ANOVA (PROC MIXED) in which compounds were treated as main plots, dilutions or doses as subplots, mini‐colonies and apiariums as experimental units, and replicates as random effects. 56 Since the total numbers of Varroa mites were not equal in all replicates (laboratory or field assessments), a weighted statement was applied in analyses. In the laboratory assessment (apiarium), mite and bee mortalities (%) were calculated based on the portion of dead mites or bees to total mites or bees in apiariums, respectively. Treatments (AIs) in the apiarium assay were grouped based on average cumulative mite and bee mortality rates using a clustering method (PROC FASTCLUS). The effects of semi‐field treatments on mite population were analyzed by ANOVA using a repeated measure analysis of variance using an autoregressive heterogeneous covariance structure with treatments as main effects, mini‐colonies as subjects, and sampling periods as a repeated measure. 56 Daily mite mortality rate (mites/total mites/day) was assessed based on dead mites collected from sticky traps placed under the mini‐colony, length (day) of each sampling period, and initial total mites in the bee cluster using the equation 57 :

where a denotes the percentage of mite lost and b represents the length (day) of the sampling period. Total mites in mini‐colonies was evaluated by adding all mites that dropped during the experiment to those collected during the finishing treatment. Length of sampling was the number of days that the sticky traps were in mini‐colonies. However, cumulative mite drop (mites/day) in the semi‐field assay was estimated as the sum of dead mites that were collected on the sticky traps over the length of the experiment divided by the total length of treatment (days). The arithmetic mean abundance of Varroa mites (%) 58 , 59 in colonies was estimated using the alcohol wash technique to remove the mites from the bees and calculate the number of Varroa mites per 100 bees. For the change in mean abundance of mites, a before‐after control impact design was used with mini‐colonies as replicates, and the interaction between the main effects and the period was used as criteria to determine significant treatment effects. 60 Percentage change in the adult bee population was calculated based on differences between the bee score before and after treatments using before‐after control impact analysis. The Shapiro–Wilk test (PROC UNIVARIATE) was applied to test the normality of the data. The proportion for mortality rates that did not fit a normal distribution was arcsine transformed prior to analyses. 61 All data are presented as untransformed values. Where significant interactions were observed, they were partitioned using the SLICE option in an LSMEANS statement and differences among treatment means were compared using Bonferroni correction. 55 The efficacy of tested compounds in the semi‐field trials was assessed based on mean abundance of mites in pre‐treatment and post‐treatment compared to negative controls using the equation 62 :

where T b and T a indicate the mean abundance of mites at before and after treatment, respectively, in tested compounds, and C b and C a indicate the mean abundance of mites for negative control at the same of time of treatment.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Laboratory assessments

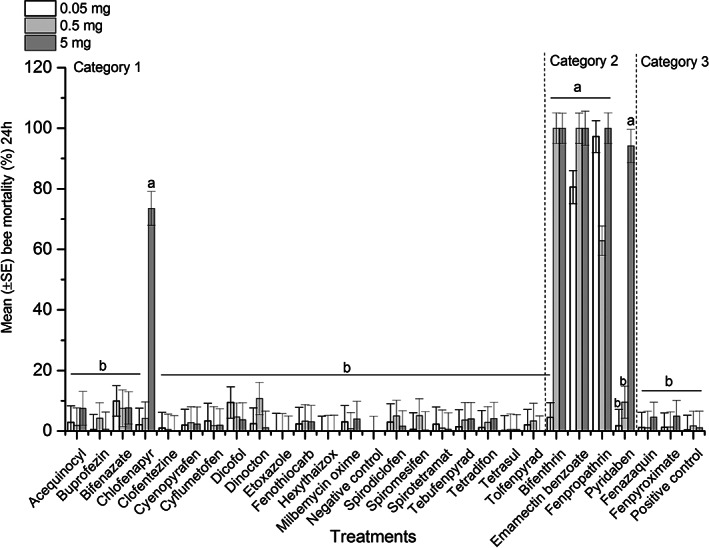

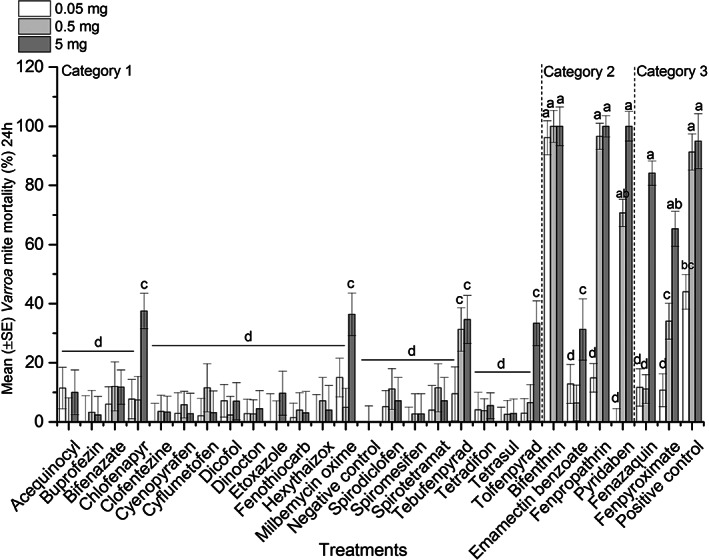

Mite and bee mortality was assessed in the apiarium, where Varroa‐infested worker bees were exposed to plastic strips covered with subsequent dilutions of AIs (n = 26) plus the positive control, amitraz. Cumulative bee (F = 21.63; df = 27, 218; P < 0.0001) and mite (F = 13.78; df = 27, 218; P < 0.0001) mortality differed significantly among treatments. Results showed a higher 24‐h bee mortality for higher dilutions of chlorfenapyr, emamectin benzoate, fenpropathrin, bifenthrin, and pyridaben compared to others (F = 34.7; df = 81, 164; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, greater Varroa mite mortality at 24 h post‐treatment was observed for higher dilutions of bifenthrin, fenpropathrin, pyridaben, fenpyroximate, fenazaquin, and amitraz compared to the rest of the AIs (weighted statement total mite: F = 13.82; df = 81, 164; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Mean (±SE) bee mortality (%) during 24 h exposure to different AIs in apiariums. A group of Varroa‐infested worker bees was exposed to a piece of plastic strip covered with dilutions of AIs (0.05 mg/apiarium, 0.5 mg/apiarium or 5 mg/apiarium) in apiarium cages under laboratory conditions during 24 h. Additional sets of apiariums were treated with different dilutions of amitraz (positive control) or left untreated (negative control). Each bar represents average bee mortality for replicates of each dilution (n = 3) or control treatments (n = 3). Vertical lines on each bar indicate ± standard error (SE). Means with the same letter among dilutions were not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Mean (±SE) Varroa mite mortality (%) during 24 h exposure to different AIs in apiariums. A group of Varroa‐infested worker bees were exposed to a piece of plastic strip covered with dilutions of AIs (0.05 mg/apiarium, 0.5 mg/apiarium or 5 mg/apiarium) in apiarium cages under laboratory conditions during 24 h. Additional sets of apiariums were treated with different dilutions of amitraz (positive control) or left untreated (negative control). Each bar represents average mite mortality for replicates of each dilution (n = 3) or control treatments (n = 3). Vertical lines on each bar indicate ± standard error (SE). Means with the same letter among dilutions were not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Partitioning the interaction of the AI treatment × dilutions within each product indicated significant differences in 24‐h mite mortality between different dilutions of amitraz (slice option: F = 3.87; df = 2, 164; P = 0.0228), fenpyroximate (slice option: F = 8.66; df = 2, 164; P < 0.0001), fenazaquin (slice option: F = 26.33; df = 2, 164; P < 0.0001), tolfenpyrad (slice option: F = 5.63; df = 2, 164; P = 0.0043), pyridaben (slice option: F = 62.21; df = 2, 164; P < 0.0001), or fenpropathrin (slice option: F = 28.86; df = 2, 164; P < 0.0001). This showed that different dilutions of these AIs presented different mite mortality rates. Meanwhile, the cumulative rate of bee mortality was not significantly different among dilutions for amitraz, fenpyroximate or fenazaquin (P > 0.05).

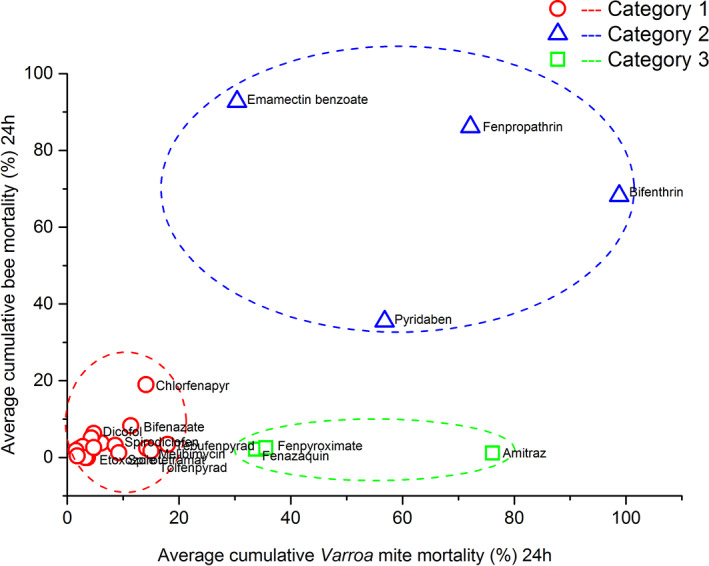

The cluster analysis divided the results of treatments into three clusters and the largest maximum distance between variables was found for the cluster 3 (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Therefore, based on the cumulative average mite and bee mortality (%) for each treatment (AI), the results of the apiarium bioassay were grouped into three categories: category 1 (n = 21) includes chemicals that had low mite efficacy (≤29%) and low bee mortality (≤20%), category 2 (n = 4) chemicals had high mite mortality (≥30%) and unacceptable honey bee mortality (≥21%), and category 3 (n = 3) chemicals had high mite mortality (≥30%) and low bee mortality (≤20%) (Figs 1, 2, 3 and Table S1). Using the results of the apiarium bioassay and our previous research for screening miticides with different MOAs, 50 we selected four compounds (fenazaquin, fenpyroximate, spirodiclofen, and spirotetramat) to test on honey bee colonies under semi‐field conditions.

Table 1.

The results of clustering on apiarium observations

| Cluster | No. of treatments | No. of replicates | Frequency | RMS of SD | Maximum distance | Nearest cluster | Distance between cluster centroids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | 189 | 11 | 10.05 | 27.67 | 3 | 81.84 |

| 2 | 4 | 36 | 16 | 3.27 | 11.59 | 1 | 81.84 |

| 3 | 3 | 27 | 225 | 18.96 | 85.11 | 1 | 96.39 |

The treatments (n = 28) based on the cumulative average mite and bee mortality in the apiarium assays were grouped into three clusters. RMS of SD is the root mean squared of standard deviation. The maximum distance is the maximum distance from cluster centroid to observation in each cluster.

Figure 3.

The scatter plot of Varroa mite and bee mortality in apiarium assay. Average cumulative Varroa mite mortality (%) was plotted against average cumulative bee mortality (%) in the apiarium assay. The symbols of red circle, blue triangle, and green square show distribution of treatments within each cluster. Each symbol represents one treatment (n = 9). Dashed lines show the area for each cluster.

3.2. Semi‐field assessments

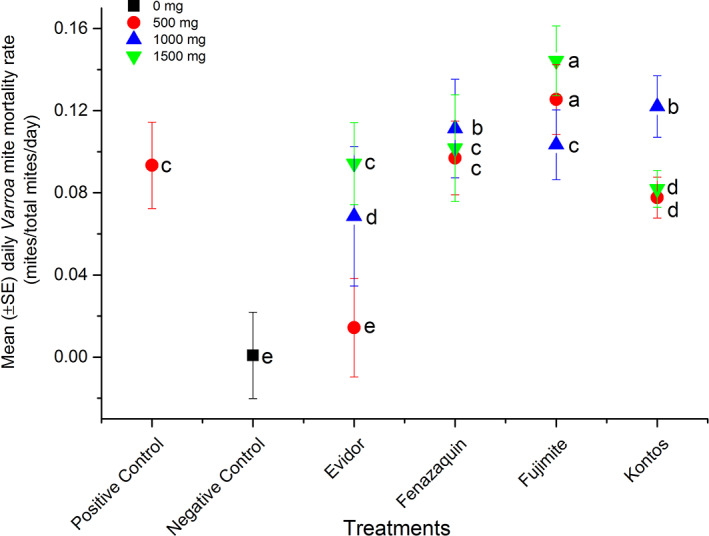

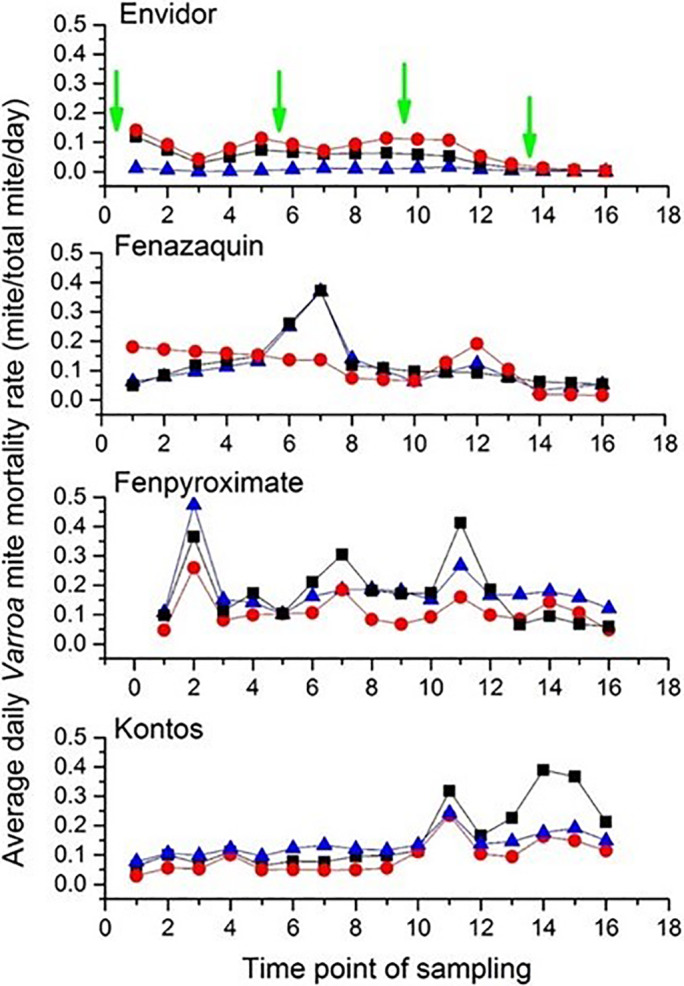

The results indicated a significant difference in cumulative daily mite mortality rate among treatments (weighted statement total mite: F = 139.07; df = 5, 36; P < 0.0001) (Table 2). Overall, repeated measure analyses indicated that the highest and most consistent daily mite mortality rate occurred for dilutions of Fujimite (500 and 1500 mg/mini colony), fenazaquin (1000 mg/mini colony), and Kontos (1000 mg/mini colony) compared to Apivar (weighted statement total mite: F = 58.43; df = 13, 28; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). Analysis of variance on the treatment × dose interaction was significant for formulated products (FPs) Envidor and Fujimite (weighted statement total mite: F = 58.43; df = 13, 28; P < 0.0001), meaning the effect of each treatment on daily mite mortality rate depended on the dose of Envidor (slice option: F = 3.50; df = 2, 28; P = 0.0441) or Fujimite (slice option: F = 5.38; df = 2, 28; P = 0.0105). Daily mite mortality rate during the trial increased after each treatment (Fig. 5). The greatest rate of daily mite mortality was observed for 500 mg Fujimite/mini‐colony.

Table 2.

Mean (±SE) cumulative daily mite mortality, daily mite drop, mean abundance, and efficacy of tested compounds in mini‐colonies

| Treatment (AI) | Daily mite mortality rate (mites/total mites/day) | Daily mite drop (mites/day) | Changes in mean abundance (%) | Efficacy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apivar (amitraz) | (9.3 ± 2.3)*10–2 ab | 10 ± 14.9cd | ‐96a | 98a |

| Negative control | (0.08 ± 2.2)*10–2 c | 4.3 ± 14.2d | 67c | ‐ |

| Envidor (spirodiclofen) | (5.9 ± 1.5)*10–2 b | 6.2 ± 9.8cd | ‐20b | 20b |

| Fenazaquin | (10.3 ± 1.3)*10–2 ab | 30 ± 8.2b | ‐80a | 88a |

| Fujimite (fenpyroximate) | (12.4 ± 1.1)*10–2 a | 54.6 ± 6.6a | ‐68ab | 80ab |

| Kontos (spirotetramat) | (9.4 ± 1)*10–2 ab | 20.5 ± 6.6c | ‐30b | 53b |

Cumulative daily mite mortality rate (mites/total mites/day), cumulative daily mite drop (mites/day), changes in mean abundance (%) of Varroa mites, and efficacy (%) in treated mini‐colonies with FPs [Envidor (spirodiclofen), Kontos (spirotetramat), Fujimite (fenpyroximate)] or AI (fenazaquin). Additional sets of three mini‐colonies were treated with Apivar (positive control) or left untreated (negative control). Means with the same letter in each column among treatments were not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Daily Varroa mite mortality rate in experimental mini‐colonies. Mean (±SE) daily mite mortality rate (mites/total mites/day) in mini‐colonies were treated with different doses (500 mg/mini‐colony, 1000 mg/mini‐colony or 1500 mg/mini‐colony) of FPs [Envidor (spirodiclofen), Kontos (spirotetramat), Fujimite (fenpyroximate)] or AI (fenazaquin). Additional sets of three mini‐colonies were treated with Apivar (500 mg amitraz per strip, positive control) or left untreated (negative control). Each symbol represents average daily mite mortality for replicates of each dilution (n = 3) or control treatments (n = 3). Vertical lines on each symbol indicate ± standard error (SE). Means with the same letter among dilutions were not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Variability in the rates of daily mite mortality in treated bees. Mean daily mite mortality rate (mites/total mites/day) in mini‐colonies treated with different doses: 500 mg/mini‐colony (solid triangle), 1000 mg/mini‐colony (solid square) or 1500 mg/mini‐colony (solid circle) of the FPs [Envidor (spirodiclofen), Kontos (spirotetramat), Fujimite (Fenpyroximate)] or AI (fenazaquin). Green arrows represent the time points of treatment application. Each symbol (solid square, circle or triangle) indicates the average daily mite mortality rate for all replicates in each dose (n = 3). Each time point of sampling represents the n th day of sampling (i.e. first, second, third, and so on).

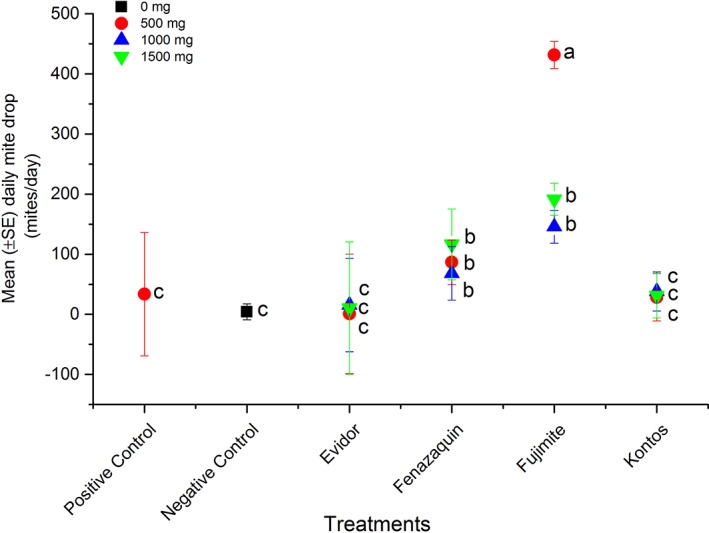

The cumulative average mite drop per day significantly differed among treatments (weighted statement total mite: F = 65.16; df = 5, 36; P < 0.0001) (Table 2). The mite drop was highest when colonies were exposed to all dilutions of Fujimite or fenazaquin (weighted statement total mite: F = 28.96; df = 13, 28; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 6). Although there was a significant interaction in dose × treatment (weighted statement total mite: F = 28.96; df = 13, 28; P < 0.0001), the cumulative daily mite drop was not dose‐dependent for all tested compounds.

Figure 6.

Daily Varroa mite drop in treated bees. Mean (±SE) daily mite drop (mites/day) in colonies that were exposed to different doses (500 mg/mini‐colony, 1000 mg/mini‐colony or 1500 mg/mini‐colony) of FPs [Envidor (spirodiclofen), Kontos (spirotetramat), and Fujimite (fenpyroximate)] or the AI (fenazaquin). Additional sets of three colonies were treated with Apivar (500 mg amitraz per strip, positive control) or left untreated (negative control). Each symbol represents average mite drop for replicates of each dilution (n = 3) or control treatments (n = 3). Vertical lines on each symbol indicate ± standard error (SE). Means with the same letter among dilutions were not significantly different (P > 0.05).

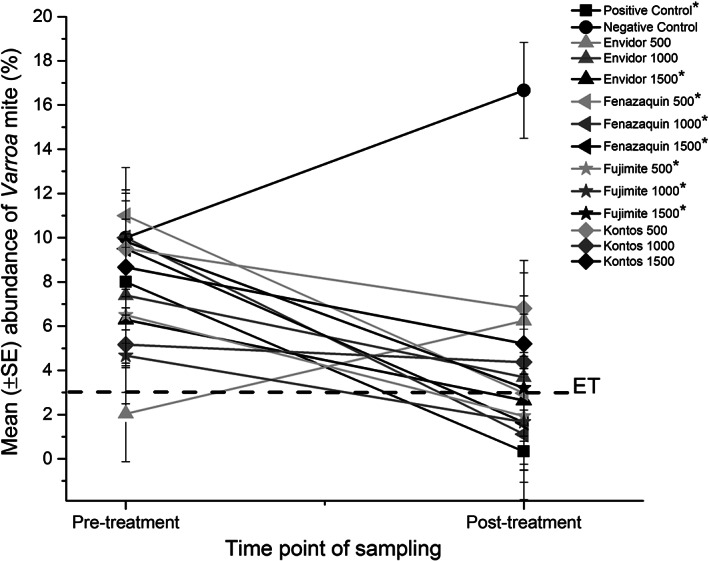

The cumulative mean abundance of mites was significantly different between pre‐ and post‐treatments for treatments (F = 9.79; df = 5, 29; P < 0.0001) (Table 2) and for dilutions (F = 4.34; df = 12, 22; P = 0.0014). Among treatments, 1500 mg/mini colony of Envidor and all dilutions of Fujimite and fenazaquin along with Apivar reduced the mite abundance below the recommended autumn economic threshold (3%) 33 (Fig. 7). Overall, cumulative mean mite abundance in some treatments significantly decreased by 96% (Apivar), 80% (fenazaquin) or 68% (Fujimite), compared to an increasing rate in the negative control (67%). For Kontos and Envidor, mean mite abundance slightly decreased by 30% and 20%, respectively. Among tested candidate compounds, the highest decrease (90%) in mean abundance was observed for fenazaquin at 1000 mg/mini‐colony (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Changes in mean abundance for Varroa mites in mini‐colonies. Mean (±SE) abundance of Varroa mites (%) in pre‐ and post‐treatment. Varroa‐infested bee colonies were exposed to different doses (500 mg/mini‐colony, 1000 mg/mini‐colony or 1500 mg/mini‐colony) of FPs [Envidor (spirodiclofen), Kontos (spirotetramat), Fujimite (fenpyroximate)] or the AI (fenazaquin). Additional sets of three colonies were treated with Apivar (500 mg amitraz per strip, positive control) or left untreated (negative control). Vertical lines on each point indicate ± standard error (SE). Each point represents the average Varroa mite abundance for each dilution (n = 3) or control treatments (n = 3) at each point of sampling (pre‐ or post‐treatment). The dashed line labelled ET represents the recommended autumn economic threshold (3%) for Varroa treatment. Asterisks indicate a significant reduction in mean abundance of Varroa mites (≤3%) for each dilution (P < 0.05).

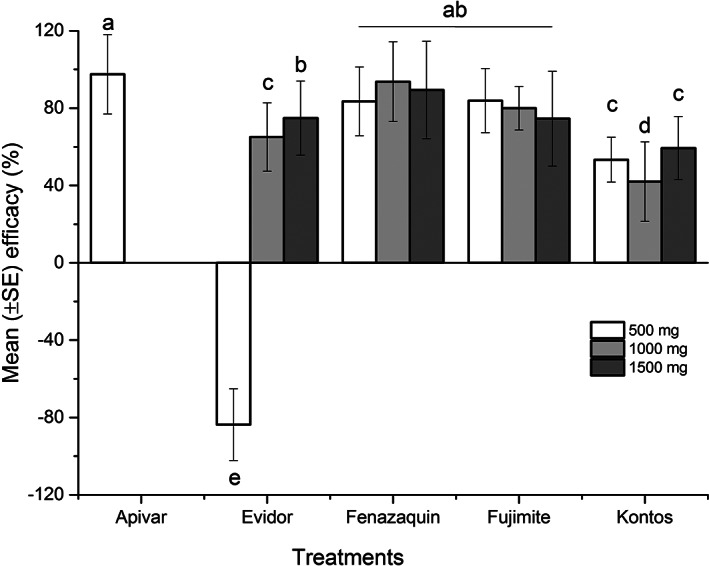

The efficacy of the tested compounds was defined as a reduction in mean abundance of Varroa population (%) in treatments compared to the negative control over the experiment. The efficacy was significantly different among treatments (F = 5; df = 4, 32; P = 0.003) (Table 2) and within different dilutions (F = 3.52; df = 12, 24; P = 0.0042) in mini‐colonies. Analysis of variance presented a significantly high efficacy for Apivar, all dilutions of fenazaquin and Fujimite, and 1500 mg Envidor/mini‐colony in comparison to others (Fig. 8). Partitioning the treatment × dose interaction indicated significant differences between the efficacy of doses only for Kontos (slice option: F= 2; df = 2, 24; p = 0.0158) and Envidor (slice option: F = 6.02; df = 2, 24; P = 0.0076). This indicates the other tested compounds presented similar efficacy within different doses (P > 0.05).

Figure 8.

Efficacy of tested miticides. Mean (±SE) efficacy (%) of Apivar or different dilutions (500 mg/mini‐colony, 1000 mg/mini‐colony or 1500 mg/mini‐colony) of Envidor (spirodiclofen), Kontos (spirotetramat), Fujimite (fenpyroximate), or fenazaquin. Each bar indicates average efficacy for replicates of each dilution (n = 3) or Apivar (n = 3). Vertical lines on each bar indicate ± standard error (SE). Means with the same letter among dilutions were not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Bee populations significantly dropped over the duration of the experiment (F = 4.4; df = 5, 36; P = 0.0031). A significantly higher bee decline was observed in the negative control (74 ± 8%). However, the lowest decline rate was observed for Fujimite 500 mg/mini‐colony (19 ± 7%) and fenazaquin 1000 mg/mini‐colony (16 ± 8%), both significantly lower than the positive (48 ± 5%) and negative (74 ± 4%) controls (F = 3.07; df = 13, 28; P = 0.0062).

4. DISCUSSION

Considering the high cost of colony loss and risk of developing resistance to registered Varroacides already on the market, new products with a different MOA need to be assessed and developed for treatment of Varroa. This study took a different approach to screening new miticides by utilizing a newly designed laboratory bioassay method (apiarium) for testing mites and bees together, attempting to replicate a colony‐like environment before field‐testing. In this experiment, 26 AIs from 19 chemical classes were screened in the laboratory using plastic strips, similar to Varroacides such as Apistan, Apivar and Bayvarol. Overall, the results of the apiarium and semi‐field trials confirmed fenazaquin as a potential Varroacide, followed by fenpyroximate. Both products had high efficacy (>80%), reduced the mite population below the recommended autumn economic threshold (3%), and met the initial criteria for further testing. The preliminary results from this study are foundational for the development and registration of a new Varroacide; however, we do not recommend the off‐label application of any miticide or AI used in this study before extensive testing is completed and safety in hive products are determined based on the final application method.

A number of investigations have exposed Varroa to miticides in glass vials, 35 , 63 , 64 but few have tested bees and mites together. 65 The apiarium provided an opportunity to test bees and mites simultaneously, while evaluating the application method that would be used in field trials if chemicals had acceptable results. Three categories were created based on the apiarium results to help in vetting compounds for field‐testing. Compounds in category 1 showed low mite mortality and low bee mortality, and were excluded from field trials, with the exception of spirotetramat and spirodiclofen, which demonstrated high mite mortality in the Bahreini et al. 50 contact‐bioassay trials. One compound in this category, spiromesifen, had been previously reported to have high efficacy (approximately 80%) when mites were exposed to the FP (Forbid, Bayer, Canada) in contact‐bioassays using glass vials. 63 These results were not replicated when tested in contact bioassays 50 or in the apiarium bioassay with the AI. To see higher efficacy, this compound may require more time (>24 h, chronic effects), higher doses, or changes to the application method. Some dilutions of miticides tested in category 2 (e.g. bifenthrin, fenpropathrin, and pyridaben) showed high mite mortality after 24 h, similar to amitraz (positive control), but higher dilutions of the AIs killed an unacceptable amount of bees. Although harmful to bees at the tested dilutions, they should not be excluded from future testing. Opportunities exist to examine different doses and application methods in a longer duration to evaluate chronic effects. Our study showed bifenthrin caused high mortality in bee clusters similar to Ellis et al., 66 but lower dilutions killed >90% mites in the apiarium test. Future studies may seek to find an effective dose of bifenthrin for mites that is tolerable for honey bees. Precautions should be taken as this compound is in the same class as tau‐fluvalinate and flumethrin (pyrethroids), and there is a high risk of cross‐resistance. 67 , 68 Additional compounds in category 2, fenpropathrin and pyridaben, lack information on the effects on V. destructor or A. mellifera. Despite having high mite mortality in the apiarium bioassay, fenpropathrin and pyridaben also killed an unacceptable amount of worker bees. More sensitive testing could identify a dilution that is safe for bees and effective for controlling mites. Category 3 compounds (fenazaquin and fenpyroximate) showed high mite mortality and low bee mortality in the apiarium, and were selected for testing under semi‐field conditions.

Our experiment was the first investigation to evaluate spirotetramat and spirodiclofen (category 1 compounds) on the effects on V. destructor and A. mellifera under semi‐field conditions. These compounds were selected for field evaluation as they performed well in the Bahreini et al. 50 contact bioassay experiments (glass vial test), but demonstrated low efficacy on mites in the apiarium bioassay. The purpose of including these two chemicals in field trials was to observe and evaluate whether the contact‐bioassay or the apiarium would be a better predictor of field‐level efficacy on Varroa. Spirotetramat and spirodiclofen are tetronic acids with inhibitory effects on lipid biosynthesis. 46 There are a number of tetronic acid miticides currently registered in Canada 69 and widely used against a broad range of pest insects and phytophagous mites. 70 Miticides in this chemical family provide various options for potential Varroa control, but many studies indicate the presence of tetronic acid resistance in Panonychus ulmi (Koch), Panonychus citri (McGregor), and T. urticae Koch. 71 , 72 T. urticae, for instance, has the ability to resist new miticides within a few treatments due to innate detoxifying mechanisms. 73 It has not been confirmed if these mechanisms are present in Varroa mite populations, therefore close monitoring is essential if tetronic acids are chosen for future evaluation. Spirotetramat has been recognized as a relatively safe AI for Apis cerana indica Fab. compared to other pesticides, 74 but A. mellifera mortality has been reported from colonies exposed to spirotetramat from crop and tree applications. 70 In previous laboratory tests, 50 both spirotetramat and spirodiclofen had positive, dose‐dependent bee mortality in the Mason jar bioassay. In contrast, the results of the apiarium and field studies showed both compounds had low bee mortality. This may be due to different exposure methods. Although our semi‐field study showed commercial FPs of spirotetramat (all dilutions of Kontos) and spirodiclofen (lower dilution of Envidor) had low efficacy for reducing mean mite abundance, testing different doses of the AI or different application methods could yield higher efficacy for reducing Varroa populations.

Of the two most promising miticides from the apiarium experiment, Fujimite (fenpyroximate) showed the second highest reduction in mean abundance of Varroa in semi‐field trials (80% efficacy). Fenpyroximate is from the pyrazoles chemical class and was commercialized in 1991 by Nihon Noyaku. 75 , 76 It inhibits mitochondrial electron transport at the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH)‐coenzyme Q reductase site of Complex I 77 with low to moderate effects on beneficial insects and predatory mites. 78 , 79 Fenpyroximate was previously introduced in 2007 as a commercial Varroacide (Hivastan, Wellmark, USA) in the USA to control V. destructor, 80 but was not registered in Canada. Hivastan was formulated in a patty containing 0.3% fenpyroximate and distributed for a few years before it was removed from the market in 2010. Although information on the efficacy of Hivastan on mites and its adverse effects on bees are lacking, Johnson et al. 80 reported adult honey bee population mortality in colonies soon after application. Since Hivastan was removed from the market, Fujimite (AI fenpyroximate) was tested for the first time on V. destructor and A. mellifera in semi‐field trials. Some investigations have reported toxicity of fenpyroximate on A. mellifera. 81 , 82 Our laboratory results showed slightly higher, but not significant, difference in bee mortality comparing fenpyroximate and amitraz. In contrast, Johnson et al. 83 found higher toxicity for amitraz than fenpyroximate. The difference in toxicity could have resulted from the application method or the dose applied, as Johnson et al. 83 directly exposed bees to the AI and held them in wax‐coated paper cups (177 mL). Another study reported that fenpyroximate had a higher toxicity to worker bees than queens; however, queen health was still impacted at very low doses over a 6‐week period. 81 In our semi‐field experiment, we did not see a negative acute effect of fenpyroximate on queens, which is likely attributed to the short experiment duration. Unlike previous laboratory studies, 83 our semi‐field results also show that the small bee cluster in the mini‐colonies can tolerate up to 1500 mg over a 4‐week period, while showing high efficacy for Varroa control. Although fenpyroximate is not currently used in bee colonies, it has been used for other species. Fujimite is currently used as a tool against spider mites (Tetranychus spp.), but resistance to fenpyroximate has been reported in some target species, 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 including the two‐spotted spider mite (T. urticae). There are no available documents on Varroa populations being resistant to fenpyroximate, but two‐spotted spider mites resist fenpyroximate via detoxification P450 and ester activities. 87 Honey bees are exposed to numerous agricultural pesticides, including the mitochondrial inhibitor compounds (e.g. pyrazoles chemical class) in agricultural environments. The presence of pesticides in bee‐collected foods or agrochemical residues in wax may contribute to developing Varroa resistance to pesticides. Despite the potential for resistance development in Varroa, proper integrated pest management (IPM) practices, such as rotation of available treatments, can delay resistant genes from becoming prevalent. 88 , 89 We propose that fenpyroximate should be reassessed and potentially reformulated for use against Varroa for in‐hive use. Further studies to find an effective formulation, dose, and application method are required. Once found, a longer study would be necessary to test the chronic influences of this Varroacide on full‐size colonies to investigate any sublethal effects on queen physiology and colony fitness.

Fenazaquin had the highest efficacy to control Varroa in the semi‐field study. It is in the quinazolines chemical class and was introduced by Dow AgroSciences in 1998. 90 Since the FP of fenazaquin (Magister, Gowan, AZ, USA) was not available in Canada, we used the AI in semi‐field trials. The quinazoline class includes chemical compounds representing a wide variety of biological activities against animal and human parasites and pathogens. 91 Quinazoline commercialized FPs have reported minimal impacts on many beneficial insects and mites. 92 Fenazaquin inhibits the mitochondrial electron transport chain and has been used against different stages of spider mites. 93 At present, there have been no reports of Varroa resistance to fenazaquin; however, it is important to note that P. ulmi 94 and T. urticae 95 were documented as fenazaquin resistant. To our knowledge, this study is the first investigation testing the efficacy of fenazaquin on V. destructor and the effects on A. mellifera. Additionally, no documented studies have evaluated the potential risks of fenazaquin on honey bee physiology, behavior or fitness. The results of this study showed that fenazaquin decreased the mean abundance of Varroa by 88% with no observed negative effects on the bee population. Further research is required to evaluate fenazaquin along with its associated FPs in full‐size Varroa‐infested honey bee colonies, as commercial miticides contain adjuvants and synergistic compounds that can enhance their efficiency. 96 We strongly suggest that fenazaquin be considered as a potential new Varroacide and recommend more stringent studies to complete our investigations before commercialization. There is potential for Varroa to develop resistance to fenazaquin, similar to fenpyroximate, nevertheless, the resistance mechanism is not known and should be determined. As always, proper IPM integration of any chemical pesticides should be followed to suppress resistant pest populations. Also similar to our suggestions for fenpyroximate, a fully formulated application method and longer experiment duration (chronic and sublethal effects) would be required before attempting to register any products for in‐hive use against Varroa.

One of the objectives of this study was to determine whether the apiarium could capture the miticide‐Varroa‐honey bee interaction, similar to what would be observed under semi‐field conditions, when compared to the contact vial bioassay. Despite being a preliminary study, our results show that there is a relationship between miticide efficacy in the apiarium in the laboratory and semi‐field trials. Fenazaquin and fenpyroximate, for instance, performed well in the contact bioassays 50 and in the apiarium, and showed the highest efficacy at the colony level in semi‐field trials. Meanwhile, spirodiclofen and spirotetramat performed well in contact bioassays, poorly in the apiarium, and showed minimal effectiveness in the semi‐field trials. More investigations are needed, but results are encouraging that the apiarium can be a useful tool for screening chemicals before scaling up to field assessments. As with any bioassay method, there are factors that limit the apiarium's efficacy. Previous research suggests that Varroa parasitization shortens bee longevity and reduces the honey bees' ability to process pesticides due to their compromised immune system. 28 This could explain some of the variation in bee mortality between dilution replicates because each apiarium's mite infestation level was not equalized. Apiariums with higher mite abundance may experience increased bee mortality rates, not necessarily due to the compound introduced, but due to a compromised immune system caused by Varroa parasitization. The semi‐field trials also had some limiting factors that should be addressed. The delivery method may have restricted the amount of chemical released over the experiment. Other factors that must be considered in Varroacide screening field trials are the local environment and genetics of tested Varroa mites and honey bees. Field tests of chemicals differ from laboratory trials due to a larger environment, uncontrolled ambient environmental elements (e.g. temperature, humidity, and CO2), and social interactions among individual bees. This can influence the interaction between miticide‐Varroa‐honey bees and needs to be considered for field trials. Furthermore, Varroa populations with previous exposure to compounds in a similar chemical class could have pre‐existing resistant genetics (cross‐resistance) and influence results. Additionally, resistant bee stocks with grooming genotypes could reduce the Varroa phoretic population through defensive behavior, 97 , 98 , 99 which can be mistaken for miticide efficacy.

5. CONCLUSION

Current treatments available to beekeepers for Varroa control are limited and there is growing evidence that resistance is developing in the few registered miticides for use by beekeepers. 22 , 35 , 36 Inability to control Varroa populations not only threatens colony health, it can lead to substantial economic losses for beekeepers and crop pollinations. Therefore, finding new Varroacides is paramount for the health of the beekeeping industry. The purpose of this research was to expand on our previous study 50 and conduct further evaluation of identified compounds under laboratory and field conditions. Based on our current results we have identified fenazaquin (quinazoline class) and fenpyroximate (pyrazoles class) as potential compounds that could be developed for in‐hive use against V. destructor. According to the pesticide registration system in Canada, pesticides are considered as ‘effective’, if their efficacy is above 80%. 69 These compounds with >80% efficacy and safe to honey bees are good candidates for future registration in Canada. Although our research presents advancement towards commercial product development, further rigorous testing of dosage, method of application, and safety to hive products and applicators needs to be completed to meet all requirements for legally registered use in honey bee colonies. Moreover, it has yet to be determined how these chemicals influence all A. mellifera or V. destructor developmental stages, and if there are sublethal or chronic long‐term colony affects. Furthermore, these compounds need to comply with industry regulations for low residues in bee‐related products (e.g. honey, wax, propolis, and pollen) and be safe for the applicator. Overall, fenazaquin and fenpyroximate both have the potential to add significant economic value to apiculture and agriculture if they align with all industry and federal regulations for pesticides. Additionally, both compounds could provide effective Varroa control and alternative options for managing Varroa resistance to be included in current IPM practices, and enable sustainable, productive, and healthy honey bee stocks for the future.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: RB, MN; formal analysis: RB; funding acquisition: MD, DF; investigation: RB, CD, OD, SM, MN; methodology: RB, MN; writing – original draft preparation: RB, CD, OD; writing – review & editing: RB, CD, OD, SM, MN, DF.

Supporting information

Table S1. List of AIs and their associated formulated products. A group of miticidal compounds were evaluated in this study from different chemical classes with different modes of action. The treatments, based on the rates of mite and bee mortality in the apiarium assay, were grouped into three categories: 1 (low mortality of mite and bee), 2 (high mortality of mite and bee), and 3 (high mortality of mite and low mortality of bee).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Parisa Fatehmanesh, Maksat Igdyrov, Sara Baron, Mellissa Howard, Glyn Stephens, Michelle Fraser, Alexandra Panasiuk, Rosanna Punko, Sian Ramsden, Emily Olson, Karlee Shaw, Paul Schmermund, Jared Amos, Sarah Waterhouse, Eric Jalbert, Angus Abels, Lynae Ovinge, Jeff Kearns, Cameron Stevenson, Jo‐Ann Berry, and Cindy Samborsky for their technical and supportive assistance. We also appreciate Dr. Shelley Hoover for her support. This research was sponsored by acknowledged funders: the Alberta Crop Industry Development Fund (ACIDF), Growing Forward 2 (a federal‐provincial‐territorial initiative), and Alberta Beekeepers Commission (ABC). The funders had no role in experimental design, data collection and analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or publishing.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available on request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Naeem M, Huang J, Zhang S, Luo S, Liu Y, Zhang H et al., Diagnostic indicators of wild pollinators for biodiversity monitoring in long‐term conservation. Sci Total Environ 708:135–231 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Loreau M, Naeem S, Inchausti P, Bengtsson J, Grime JP, Hector A et al., Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: current knowledge and future challenges. Science 294:804–808 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Costanza R, D'Arge R, DeGroot R, Farber S, Grasso M, Hannon B et al., The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387:253–260 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kearns CA, Inouye DW and Waser NM, Endangered mutualisms: the conservation of plant–pollinator interactions. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 29:83–112 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gallai N, Salles JM, Settele J and Vaissiere BE, Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecol Econ 68:810–821 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Calderone N, Insect pollinated crops, insect pollinators, and US agriculture: trend analysis of aggregate data for the period 1992–2009. PLoS ONE 7:e37235 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hung KJ, Kingston JM, Albrecht M, Holway DA and Kohn JR, The worldwide importance of honey bees as pollinators in natural habitats. Proc Roy Soc B 285:20172140 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holden C, Report warns of looming pollination crisis in North America. Science 314:397 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Klein AM, Vaissiere BE, Cane JH, Steffan‐Dewenter I, Cunnigham SA, Kremen C et al., Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc Roy Soc 274:303–313 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Watanabe ME, Pollination worries rise as honey‐bees decline. Science 265:1170–1170 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fries I and Camazine S, Implications of horizontal and vertical pathogen transmission for honey bee epidemiology. Apidologie 32:199–214 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Forfert N, Natsopoulou ME, Frey E, Rosenkranz P, Paxton RJ and Moritz RF, Parasites and pathogens of the honeybee (Apis mellifera) and their influence on inter‐colonial transmission. PLoS ONE 10:e0140337 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. LeConte Y, Ellis M and Ritter W, Varroa mites and honey bee health: can Varroa explain part of the colony losses? Apidologie 41:353–363 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 14. VanEngelsdorp D, Caron D, Hayes J, Underwood R, Henson M, Rennich K et al., A national survey of managed honey bee 2010‐11 winter colony losses in the USA: results from the bee informed partnership. J Apicul Res 51:115–124 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Higes M, Martin‐Hernandez R, Botias C, Bailon EG, Gonzalez‐Porto AV, Barrios L et al., How natural infection by Nosema ceranae causes honeybee colony collapse. Environ Microbiol 10:2659–2669 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cox‐Foster S, Conlan EC, Holmes G, Palacios JD, Evans NA, Moran PL et al., A metagenomic survey of microbes in honey bee colony collapse disorder. Science 318:283–287 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carreck N and Neumann P, Honey bee colony losses. J Apicul Res 49:1–6 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dainat B and Neumann P, Clinical signs of deformed wing virus infection are predictive markers for honey bee colony losses. J Invertebr Pathol 112:278–280 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Di Pasquale G, Salignon M, Le Conte Y, Belzunces LP, Decourtye A, Kretzschmar A et al., Influence of pollen nutrition on honey bee health: do pollen quality and diversity matter? PLoS ONE 8:e72016 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mullin CA, Frazier M, Frazier JL, Ashcraft S, Simonds R, Vanengelsdorp D et al., High levels of miticides and agrochemicals in north American apiaries: implications for honey bee health. PLoS ONE 5:e9754 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu JY, Anelli CM and Sheppard WS, Sub‐lethal effects of pesticides residues in brood comb on worker honey bee (Apis mellifera) development and longevity. PLoS ONE 6:e14720 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Currie RW, Pernal SF and Guzman‐Novoa E, Honey bee colony losses in Canada. J Apicul Res 49:104–106 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guzman‐Novoa E, Eccles L, Calvete Y, Mcgowan J, Kelly PG and Correa‐Benitz A, Varroa destructor is the main culprit for the death and reduced populations of overwintered honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies in Ontario, Canada. Apidologie 41:443–450 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gregory PG, Evans JD, Rinderer T and DeGuzman L, Conditional immune‐gene suppression of honeybees parasitized by Varroa mites. J Insect Sci 5:7–5 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aronstein KA, Saldivar E, Vega R, Westmiller S and Douglas AE, How Varroa parasitism affects the immunological and nutritional status of the honey bee, Apis Mellifera. Insects 3:601–615 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Amdam GV, Hartfelder K, Norberg K, Hagen A and Omholt SW, Altered physiology in worker honey bees (hymenoptera: Apidae) infested with the mite Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae): a factor in colony loss during overwintering? J Econ Entomol 97:741–747 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ramsey S, Ochoa R, Bauchan G, Gulbronson C, Mowery JD, Cohen A et al., Varroa destructor feeds primarily on honey bee fat body tissue and not hemolymph. PNAS 116:1792–1801 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morfin N, Goodwin PH and Guzman‐Novoa E, Interaction of field realistic doses of clothianidin and Varroa destructor parasitism on adult honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) health and neural gene expression, and antagonistic effects on differentially expressed genes. PLoS ONE 15:e0229030 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bahreini R and Currie RW, Influence of honey bee genotype and wintering method on wintering performance of Varroa destructor (Parasitiformes: Varroidae)‐infected honey bee (hymenoptera: Apidae) colonies in a northern climate. J Econ Entomol 108:1495–1505 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schafer MO, Ritter W, Pettis JS and Neumann P, Concurrent parasitism alters thermoregulation in honey bee (hymenoptera: Apidae) winter clusters. Ann Entomol Soc Am 104:476–482 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 31. Posada‐Florez F, Childers AK, Heerman MC, Egekwu NI, Cook SC, Chen Y et al., Deformed wing virus type a, a major honey bee pathogen, is vectored by the mite Varroa destructor in a non‐propagative manner. Sci Rep 9:12445 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Collins AM and Pettis JS, Correlation of queen size and spermathecal contents and effects of miticide exposure during development. Apidologie 44:351–356 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 33. Currie R, Economic Threshold for Varroa on the Canadian Prairies. CAPA, Canada; 2008. Available: https://capabees.com/shared/2013/02/varroathreshold.pdf [17 September 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brodschneider R, Gray A, van der Zee R, Adjlane N, Brusbardis V, Charriere JD et al., Preliminary analysis of loss rates of honey bee colonies during winter 2015/16 from the COLOSS survey. J Apicul Res 55:375–378 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 35. Elzen P, Eischen FA, Baxter JR, Elzen GW and Wilson WT, Detection of resistance in US Varroa jacobsoni oud. (Mesostigmata: Varroidae) to the acaricide fluvalinate. Apidologie 30:12–17 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rinkevich F, Detection of amitraz resistance and reduced treatment efficacy in the Varroa mite, Varroa destructor, within commercial beekeeping operations. PLoS ONE 15:e0227264 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maggi M, Ruffinengo S, Damiani N, Sardella N and Eguaras E, First detection of Varroa destructor resistance to coumaphos in Argentina. Exp Appl Acarol 47:317–320 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Milani N, The resistance of Varroa jacobsoni oud. To pyrethroids: a laboratory assay. Apidologie 26:415–429 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Walsh EM, Sweet S, Knap A, Ing N and Rangel J, Queen honey bee (Apis mellifera) pheromone and reproductive behavior are affected by pesticide exposure during development. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 74:33 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hollingworth RM, Chemistry, biological activity, and uses of formamidine pesticides. Environ Health Perspect 14:57–69 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pugliese N, Circella E, Cocciolo G, Giangaspero A, Tomic D, Kika T et al., Efficacy of λ‐cyhalothrin, amitraz, and phoxim against the poultry red mite Dermanyssus gallinae De Geer, 1778 (Mesostigmata: Dermanyssidae): an eight‐year survey. Avian Pathol 48:S35–S43 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jonsson NN, Klafke G, Corley SW, Tidwell J, Berry CM and Koh‐Tan HC, Molecular biology of amitraz resistance in cattle ticks of the genus Rhipicephalus . Frontiers in Bioscience 23:796–810 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dermauw W, Ilias A, Riga M, Tsagkarakou A, Grbic M, Tirry L et al., The cys‐loop ligand‐gated ion channel gene family of Tetranychus urticae: implications for acaricide toxicology and a novel mutation associated with abamectin resistance. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 42:455–465 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nauen R and Smagghe G, Mode of action of etoxazole. Pest Manag Sci 62:379–382 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Van Leeuwen T, Demaeght P, Osborne EJ, Dermauw W, Gohlke S, Nauen R et al., Population bulk segregant mapping uncovers resistance mutations and the mode of action of a chitin synthesis inhibitor in arthropods. PNSA 109:4407–4412 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bretschneider T, Benet‐Buchholz J, Fischer R and Nauen R, Spirodiclofen and spiromesifen—novel acaricidal and insecticidal tetronic acid derivatives with a new mode of action. Chim Int J Chem 57:697–701 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hollingworth RM, Ahammadsahib KI, Gadelhak G and McLaughlin JL, New inhibitors of complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain with activity as pesticides. Biochem Soc Trans 22:230–233 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kinoshita S, Koura Y, Kariya H, Ohsaki N and Watanabe T, AKD‐2023: a novel miticide. Biological activity and mode of action. Pestic Sci 55:659–660 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 49. van Nieuwenhuyse P, Demaeght P, Dermauw W, Khalighi M, Stevens CV, Vanholme B et al., On the mode of action of bifenazate: new evidence for a mitochondrial target site. Pestic Biochem Physiol 104:88–95 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bahreini R, Nasr M, Docherty C, de Herdt O, Muirhead S and Feindel D, Evaluation of potential miticide toxicity to Varroa destructor and honey bees, Apis mellifera, under laboratory conditions. Sci Rep 10:21529 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bahreini R, Nasr M, Docherty C, Feindel D, Muirhead S and de Herdt O, New bioassay cage methodology for in vitro studies on Varroa destructor and Apis mellifera . PLoS ONE 16:e0250594 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Eccles L, Kempers M, Gonzalez B, Thurston RM, Borges D, Canadian best management practices for honey bee health. Available: http://www.honeycouncil.ca/images2/pdfs/BMP_manual_‐_Les_Eccles_Pub_22920_‐_FINAL_‐_low‐res_web_‐_English.pdf [17 September 2021].

- 53. Gruszka J, Currie RW, Dixon D, Tuckey K and van Westendorp P, Beekeeping in western Canada. Alberta Agriculture. Edmonton, AB, Canada: Food and Rural Development, (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pettis JS, Shimanuki H and Feldlaufer MF, An assay to detect fluvalinate resistance in Varroa mites. Am Bee J 138:538–541 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 55. Burgett M and Burikam I, Number of adult honey bees (hymenoptera: Apidae) occupying a comb: a standard for estimating colony populations. J Econ Entomol 78:1154–1156 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 56. SAS Institute Inc , SAS/STATVR 9.3 User's Guide. SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC: (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 57. Martin SJ, A population model for the ectoparasitic mite Varroa jacobsoni in honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies. Ecol Model 109:267–281 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bush AO, Lafferty KD, Lotz JM and Shostak AW, Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis Shostak AW revisited. J Parasitol 83:575–583 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rozsa L, Reiczigel J and Majoros G, Quantifying parasites in samples of hosts. J Parasitol 86:228–232 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stewart‐Oaten A, Murdoch WW and Parker KR, Environmental impact assessment: “Pseudoreplication” in time? Ecology 67:929–940 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 61. Snedecor GW and Cochran WG, Statistical Methods. The Iowa State University Press, Iowa, IA: (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 62. Henderson CF and Tilton EW, Acaricides tested against the brown wheat mite. J Econ Entomol 48:157–161 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vandervalk L, New options for integrated pets management of Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) in colonies of Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) under Canadian prairie conditions. M.Sc. Thesis. University of Alberta, 121 pp (2013).

- 64. Kanga LHB, Adamczyk J, Marshall K and Cox R, Monitoring for resistance to organophosphorus and pyrethroid insecticides in Varroa mite population. J Econ Entomol 103:1797–1802 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gregorc A, Alburaki M, Sampson B, Knight PR and Adamczyk J, Toxicity of selected acaricides to honey bees (Apis mellifera) and Varroa (Varroa destructor Anderson and Trueman) and their use in controlling Varroa within honey bee colonies. Insects 9:55 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ellis MD, Siegfried BD and Spawn B, The effect of Apistan® on honey bee (Apis mellifera L): responses to methyl parathion, carbaryl and bifenthrin exposure. Apidologie 28:123–127 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 67. Milani N, The resistance of Varroa jacobsoni oud. To acaricides. Apidologie 30:229–234 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bak B, Wilde J and Siuda M, Characteristics of north‐eastern population of Varroa destructor resistant to synthetic pyrethroids. Med Weter 68:603–606 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA). Ottawa, ON, Canada; 2003. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health‐canada/services/consumer‐product‐safety/reports‐publications/pesticides‐pest‐management/policies‐guidelines/regulatory‐directive/2004/efficacy‐guidelines‐plant‐protection‐products‐dir2003‐04.html [17 September 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Maus CH, Ecotoxicological profile of the insecticide spirotetramat. Bayer Crop Sci J 61:159–180 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hu JF, Wang CF, Wang J, You Y and Chen F, Monitoring of resistance to spirodiclofen and five other acaricides in Panonychus citri collected from Chinese citrus orchards. Pest Manag Sci 66:1025–1030 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kramer T and Nauen R, Monitoring of spirodiclofen susceptibility in field populations of European red mites, Panonychus ulmi (Koch) (Acari: Tetranychidae), and the cross‐resistance pattern of a laboratory‐selected strain. Pest Manag Sci 67:1285–1293 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rauch N and Nauen R, Spirodiclofen resistance risk assessment in Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae): a biochemical approach. Pest Biochem Physiol 74:91–101 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vinothkumar B, Kumaran N, Boomathi N, Saravanan PA and Kuttalam S, Toxicity of spirotetramat 150 OD to honey bees. Madras Agric J 97:86–87 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kimura M, Konno T, Kajiwara O, Synergistic acaricidal compositions containing pyrazole oxime and esterase. Japanese Patent JP 02 300 103 (1990).

- 76. Konno T, Kuriyama K, Hamaguchi H, Fenpyroximate (NNI‐850) a new acaricide. Proc BCPC‐Pests Dis 71–78 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 77. Motoba K, Suzuki T and Uchida M, Effect of a new acaricide, Fenpyroximate, on energy metabolism and mitocondrial morphology in adult female Tetranychus urticae (two‐spotted spider mite). Pest Biochem Physiol 43:37–44 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dekeyser MA, Acaricide mode of action. Pest Manag Sci 61:103–110 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Saber M, Acute and population level toxicity of imidacloprid and fenpyroximate on an important egg parasitoid, Trichogramma cacoeciae (hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae). Ecotoxicology 20:1476–1484 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Johnson RM, Ellis MD, Mullin CA and Frazier M, Pesticides and honey bee toxicity – USA. Apidologie 41:312–331 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 81. Dahlgren L, Johnson RM, Siegfried BD and Ellis MD, Comparative toxicity of acaricides to honey bee (hymenoptera: Apidae) workers and queens. J Econ Entomol 105:1895–1902 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Li‐Byarlay H, Rittschof CC, Massey GH, Pittendrigh BR and Robinson GE, Socially responsive effects of brain oxidative metabolism on aggression. PNAS 111:12533–12537 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Johnson RM, Dahlgren L, Siegfried BD and Ellis MD, Acaricide, fungicide and drug interactions in honey bees (Apis mellifera). PLoS ONE 8:e54092 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Goka K, Mode of inheritance of resistance to three new acaricides in the Kanzawa spider mite, Tetranychus kanzawai Kishida (Acari: Tetranychidae). Exp Appl Acarol 22:699–708 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sato ME, Miyata T, Da Silva M, Raga A and De Souza Filho MF, Selections for fenpyroximate resistance and susceptibility, and inheritance, cross‐resistance and stability of fenpyroximate resistance in Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). Appl Entomol Zoo 39:293–302 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wu M, Adesanya AW, Morales MA, Walsh DB, Lavine LC, Lavine MD et al., Multiple acaricide resistance and underlying mechanisms in Tetranychus urticae on hops. J Pest Sci 92:543–555 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kim YJ, Lee SH, Lee SW and Ahn YJ, Fenpyroximate resistance in Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae): cross‐resistance and biochemical resistance mechanisms. Pest Manag Sci 60:1001–1006 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Alissandrakis A, Ilias E and Tsagkarakou A, Pyrethroid target site resistance in Greek populations of the honey bee parasite Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae). J Apicul Res 56:625–630 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 89. Olmstead S, Menzies C, McCallum R, Glasgow K and Cutler C, Apivar® and Bayvarol® suppress Varroa mites in honey bee colonies in Canadian maritime provinces. J Acadia Entomol Soc 15:46–49 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 90. Longhurst C, Bacci l, Buendia J, Hatton CJ, Petitprez J, Tsakonas T, et al, Fenazaquin, novel acaricide for the management of spider mites in a variety of crops. In: Proc Brighton Crop Prot Conf Pests Dis, BCPC, Farnham, Surrey, UK, 51–58 (1992).

- 91. Rajput R and Mishra A, A review on biological activity of quinazolinones. Int J Pharm Sci 4:66–70 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 92. Dutton R, Leonard P and Brow KC, Fenazaquin – a new, selective acaricide for use in fruit crops. Med Fac Landbouw Univ Gent 58:485–490 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 93. Sangeetha S and Ramaraju K, Relative toxicity of fenazaquin against two‐spotted spider mite on okra. Int J Veg Sci 19:282–293 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 94. Auger P, Bonafos R, Guichou S and Kreiter S, Resistance to fenazaquin and tebufenpyrad in Panonychus ulmi Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) populations from south of France apple orchards. Crop Prot 22:1039–1044 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 95. Vassiliou VA and Kitsis P, Acaricide resistance in Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) populations from Cyprus. J Econ Entomol 106:1848–1854 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Roggenbuck FC and Penner D, Mode of action of organosilicone adjuvants. Int Symp Growth Develop Fruit Crops. Acta Horticul 527:57–60 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 97. Currie RW and Tahmasbi GH, The ability of high‐ and low‐grooming lines of honey bees to remove the parasitic mite Varroa destructor is affected by environmental conditions. J Can Zool 86:1059–1067 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 98. Andino GK and Hunt GJ, A scientific note on a new assay to measure honeybee mite‐grooming behavior. Apidologie 42:481–484 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 99. Bahreini R and Currie RW, The effect of queen pheromone status on Varroa mite removal from honey bee colonies with different grooming ability. Exp Appl Acarol 66:383–397 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. List of AIs and their associated formulated products. A group of miticidal compounds were evaluated in this study from different chemical classes with different modes of action. The treatments, based on the rates of mite and bee mortality in the apiarium assay, were grouped into three categories: 1 (low mortality of mite and bee), 2 (high mortality of mite and bee), and 3 (high mortality of mite and low mortality of bee).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.