HISTORY OF RACISM IN MEDICINE

What happens when a healthcare system that was developed by a nation founded on the labor of enslaved individuals intersects with a disease that disproportionately affects communities of color? Shortened life expectancy, 1 worsened quality of life, 2 and differential access to what should be an untenable right—health. A brief lesson in history will demonstrate how these poor outcomes are traced to structural racism thereby cultivating mistrust and poor outcomes for individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD). Structural racism refers to when a system (e.g., health care) assigns value and power based on race, thereby enabling discriminatory practices and policies that perpetuate inequity. 3 Following the Civil War and the emancipation of enslaved Black individuals, hospitals and physicians refused to provide medical treatment to Black patients until Congress intervened. 4 Centuries of prejudicial law led to permissible understaffing, mandated segregation, and limiting access to quality treatment. 4 While some institutions maintained separate floors for Black patients, in cities such as Philadelphia, entirely separate institutions were built to treat minority populations, 4 highlighting both theoretical and literal structural racism. The academic medical system would further contribute to the disproportionate representation of White physicians through discriminatory admission policies limiting access to the profession to Black individuals which persists today, as evidenced by the declining number of Black medical school matriculants. 5 Further, inhumane and unethical medical practices such as experimental gynecological procedures without sedation on Black women, 6 use of cellular material from patients for research without consent or approbate, 7 and overt withholding of curative therapies, as occurred in the Tuskegee Study with a cohort of Black males infected with syphilis despite the invention of penicillin, 8 have all greatly led to medical mistrust within the Black community. Ultimately these events have contributed to significant health disparities among marginalized populations, especially Black Americans, and the erosion of trust.

SCD, RACISM, AND HEALTH DISPARITIES

SCD is the most commonly detected genetic condition on newborn screenings in the United States, yet it is also one of the most neglected with regards to medical advancements and interventions. This can be directly tied to the significant underfunding of SCD research. Compared to other genetically inherited diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF) which affects one‐third as many people as SCD, funding from the National Institutes of Health and private foundations were 3.5 times and 440 times higher for CF than SCD, respectively. 9 It is hard to believe that these discrepancies are coincidental when reminded that CF affects predominantly White individuals, whereas SCD affects predominantly underrepresented minorities. The real‐life consequences of this disproportionate allocation of funds are represented in the availability of medications to treat these conditions. While the Food and Drug Administration has approved 15 medications for CF, there are a mere 4 for SCD. 10 Additionally, the implications around access to care are demonstrated in the limited number of comprehensive specialty care centers for SCD (30 recognized centers for 100,000 people), which is in significant contrast to the increased centralization and funding of centers for other genetic conditions such as CF (280 accredited centers for 30,000 people) and hemophilia (140 centers for 30,000 people). 9 While the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's guidelines for SCD include efficacious prevention strategies such as penicillin prophylaxis and transcranial doppler screening, without SCD centers, execution and uptake is lacking. 11

Though funding and pharmaceutical options certainly contribute to disparate outcomes, the longstanding history of unequal treatment experienced by individuals with SCD may help to further explain mistrust system as being a symptom of the larger problem. Moreover, healthcare provider bias contributes to inequitable care that patients with SCD experience. As mentioned earlier, the number of Black physicians in America is not representative of the growing minority population. This underrepresentation has direct implications when considering that patient‐provider race concordance has been linked to better patient adherence, clinical outcomes, and continuity of care. 12 In a sample of patients with SCD and their families who received care from majority White providers, most felt that race affected the quality of healthcare that patients with SCD receive, whereas a minority of staff shared those beliefs. 13 This discrepancy highlights the importance of examining the differences in perspective between patients and the medical team when those caring for the patient differ by race as provider attitudes and biases may contribute to health disparities through unequal care delivery.

PAIN BIAS

Pain is considered one of the hallmark complications of SCD, caused by a complex process initiated by the transformation of deoxygenated red blood cells into a rigid, sickle shape. Vaso‐occlusive pain episodes can be unpredictable, but unlike an X‐ray that can detect a broken bone, there is no clinically available objective measure of pain. Rather, the development of rating systems such as the Faces scale, 14 allow for a number to be assigned to an experience. The proceeding actions taken by medical providers depend on whether they believe the patient's report. When presenting to the healthcare system, patients with SCD are faced with the question of, will they believe my pain? This is where the system fails, and the roots of mistrust are unearthed. In a study assessing provider's beliefs about patients with SCD, common themes related to being “drug seeking” in that their symptoms were perceived as exaggerated or for the purpose of secondary gain, highlighted the ways in which bias stigmatizes those seeking help. 15 When a provider enters the interaction with a preconceived notion about the patient's motives, we perpetuate a system of mistrust. This starts at a young age and impacts disease‐related outcomes. In a sample of adolescents with SCD, pain stigma was associated with greater pain interference and worse quality of life. 16

A PATIENT'S JOURNEY

SCD is a debilitating illness that not only affects one's physical health, but one's mental and emotional health, as well. Due to the stigma of the disease, individuals afflicted with this disorder have historically expressed concern with feeling misunderstood, unheard, and uncared for by their healthcare providers 17 ; the ones who are charged to provide holistic, ethical, and unbiased care. A patient's journey in navigating SCD is made difficult when unhealthy assumptions, whether unconscious or explicitly biased by healthcare providers, are treated as objective, thus leading to harmful practices among this patient population.

As a healthcare team member and a person living with SCD, partaking in dual roles has allowed for the understanding that intentional empathy is lacking for this patient population. The effects of SCD are multi‐faceted. It affects one's home life, school, work, relationships, etc. Patient‐centered care is the practice of caring for patients and their families in a way that is meaningful and valuable to the individual. When patient‐centered care is at the forefront, intentional empathy in the form of being fully present, has the potential to fuel connection. It helps to create a space where patients and healthcare providers can be vulnerable with each other. When we choose to be intentional about practicing empathy, we break the unequitable power dynamic. We are helping to facilitate a space where trust can be developed. Providing care to someone living with SCD requires looking at the whole person, actively listening, engaging in perspective taking, and having the willingness to advocate on behalf of a patient when needed.

HOW PROVIDERS CAN REGAIN TRUST

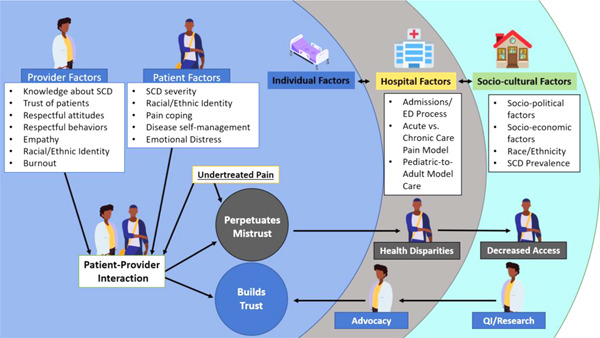

So how do we dismantle the effects centuries of racism in medicine have had on trust? We must critically evaluate both the systems and the individuals that fuel discriminatory practices. Building upon Elander and colleagues' model 18 of factors that influence concern‐raising behaviors in SCD care, we demonstrate the individual, hospital, and socio‐cultural factors that impact the patient‐provider interaction and are susceptible to perpetuate mistrust or strengthen trust in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Adapted model of contributory factors that affect patient‐provider trust.

On a system level, we must ensure the care being provided is evidence‐based and equitable. For example, standardized pain algorithms (e.g., when to escalate pain management) and personalized pain plans (e.g., preferred analgesics and dosing) can reduce emergency department wait times and prevent delayed administration of analgesia for patients with SCD. 19 It also requires healthcare leaders to invest in educating its learners and providers about SCD, particularly those who may interact with patients in an acute care setting.

At an individual level, we must each explore one's implicit biases and how past experiences may influence future interactions. Verbal and written language in medicine can heavily influence patient‐provider interactions and decision making. Stigmatizing language (e.g., “drug seeking,” “sickler,” “snowed,” and “frequent flyer”) has the power to perpetuate bias and negatively shape the impressions of all medical team members including naïve learners. As providers we are tasked with both eliminating these words from our vocabulary and have a responsibility to teach others about the harmful effects when these words are used. Critically evaluating the language being used to describe patients while rounding or in the medical record is necessary to avoid introducing other team members to biases. 20

Trust is built on respect and requires humility. Effective, culturally relevant communication can aid in improving trust. Patients often experience psychosocial pressures that are compounded by their physiologic pain. Being able to effectively communicate with a patient, creating an opportunity for the provider to connect and express empathy, can allow space to elucidate potential confounders of a patient's pain experience. This can help the provider gain more insight into the needs and/or fears of the patient and potentially mitigate these concerns, significantly improving the patient's experience of the care being delivered, and thereby improving trust as well. These are the actions that personalize the care experience and rebuild trust. It is important for providers to acknowledge the impact that decades of systemic injustices have had on the patient‐provider relationship. By truly listening to the patient's lived experience, one's internal biases, and the language that is shared around you, we can collectively reduce disparities and improve care for patients with SCD.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

LaMotte JE, Hills GD, Henry K, Jacob SA. Understanding the roots of mistrust in medicine: Learning from the example of sickle cell disease. J Hosp Med. 2022;17:495‐498. 10.1002/jhm.12800

REFERENCES

- 1. Lubeck D, Agodoa I, Bhakta N, et al. Estimated life expectancy and income of patients with sickle cell disease compared with those without sickle cell disease. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(11):1915374. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kato GJ, Piel FB, Reid CD, et al. Sickle cell disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18010. 10.1038/nrdp.2018.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities. Du Bois Review. 2011;8(1):115‐132. 10.1017/s1742058x11000130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matthew DB. Just Medicine: A Cure for Racial Inequality in American Health Care. New York University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morris DB, Gruppuso PA, McGee HA, Murillo AL, Grover A, Adashi EY. Diversity of the National Medical Student Body—four decades of inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(17):1661‐1668. 10.1056/nejmsr2028487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wall LL. The medical ethics of Dr J Marion Sims: a fresh look at the historical record. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:346‐350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moore MR. Opposed to the being of henrietta: bioslavery, pop culture and the third life of Hela Cells. Med Humanit. 2016;43(1):55‐61. 10.1136/medhum-2016-011072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. About the USPHS Syphilis Study . Tuskegee University. Accessed January 10 2022. https://www.tuskegee.edu/about-us/centers-of-excellence/bioethics-center/about-the-usphs-syphilis-study

- 9. Kanter J, Meier ER, Hankins JS, Paulukonis ST, Snyder AB. Improving outcomes for patients with sickle cell disease in the United States. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(10):428. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.3467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farooq F, Mogayzel PJ, Lanzkron S, Haywood C, Strouse JJ. Comparison of US federal and foundation funding of research for sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis and factors associated with research productivity. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(3):201737. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raphael JL, Rattler TL, Kowalkowski MA, Brousseau DC, Mueller BU, Giordano TP. Association of care in a medical home and health care utilization among children with sickle cell disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 2013;105:157‐165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hall JA, Horgan TG, Stein TS, Roter DL. Liking in the physician–patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(1):69‐77. 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00071-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nelson SC, Hackman HW. Race matters: perceptions of race and racism in a sickle cell center. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;60(3):451‐454. 10.1002/pbc.24361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baker CM, Wong D. Q.U.E.S.T.: a process of pain assessment in children. Orthop Nurs. 1987;6(1):11‐21. 10.1097/00006416-198701000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haywood C, Tanabe P, Naik R, Beach MC, Lanzkron S. The impact of race and disease on sickle cell patient wait times in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(4):651‐656. 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martin SR, Cohen LL, Mougianis I, Griffin A, Sil S, Dampier C. Stigma and pain in adolescents hospitalized for sickle cell vasoocclusive pain episodes. Clin J Pain. 2018;34(5):438‐444. 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coleman B, Ellis‐Caird H, McGowan J, Benjamin MJ. How sickle cell disease patients experience, understand and explain their pain: an interpretative phenomenological analysis study. Br J Health Psychol. 2015;21(1):190‐203. 10.1111/bjhp.12157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elander J, Beach MC, Haywood C. Respect, trust, and the management of sickle cell disease pain in hospital: comparative analysis of concern‐raising behaviors, preliminary model, and agenda for international collaborative research to inform practice. Ethn Health. 2011;16(4‐5):405‐421. 10.1080/13557858.2011.555520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kavanagh PL, Sprinz PG, Wolfgang TL, et al. Improving the management of vaso‐occlusive episodes in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):1016‐1025. 10.1542/peds.2014-3470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Power‐Hays A, McGann PT. When actions speak louder than words—racism and sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(20):1902‐1903. 10.1056/nejmp2022125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]