Abstract

Biotechnological production is a powerful tool to design materials with customized properties. The aim of this work was to apply designed spider silk proteins to produce Janus fibers with two different functional sides. First, functionalization was established through a cysteine‐modified silk protein, ntagCyseADF4(κ16). After fiber spinning, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were coupled via thiol‐ene click chemistry. Significantly reduced electrical resistivity indicated sufficient loading density of AuNPs on such fiber surfaces. Then, Janus fibers were electrospun in a side‐by‐side arrangement, with “non‐functional” eADF4(C16) on the one and “functional” ntagCyseADF4(κ16) on the other side. Post‐treatment was established to render silk fibers insoluble in water. Subsequent AuNP binding was highly selective on the ntagCyseADF4(κ16) side demonstrating the potential of such silk‐based systems to realize complex bifunctional structures with spatial resolutions in the nano scale.

Keywords: Biphasic Fibers, Conductive Fibers, Janus Fibers, Silk Functionalization, Spider Silk

Janus fibers were created by applying two different recombinant spider silk constructs that were electrospun in a side‐by‐side arrangement. Subsequent gold coupling via thiol‐ene click chemistry allowed for highly selective deposition of a conductive gold layer only on the cysteine‐modified silk protein side. The study demonstrates the high potential of tailored silk design to generate multi‐functional nanomaterials for various applications.

Low‐cost production, easy processing, and a broad range of adjustable properties such as mechanical, thermal, optical, electrical, and biological features render polymers an all‐rounder in material science. In various fields like construction, energy, water treatment, electronics and medicine, polymers are attractive alternatives to e.g. metal‐ or ceramic‐based materials. [1] Nevertheless, to sufficiently address future innovations, the intrinsically inert nature of most commercial polymers must be overcome by introducing advanced functionality e.g. via surface modifications. [2] Such surface modifications of conventional synthetic polymers can be achieved by physical‐, wet‐chemical‐, UV‐, plasma‐ and corona discharge‐treatment. [3] Although these methods have been demonstrated to be useful in applications like textiles, energy and water harvesting, superhydrophobic surfaces, packaging, tissue engineering and biomedical devices, they often come along with harsh treatment conditions of the respective polymeric materials, which can result in enhanced aging, deterioration and loss of desired properties. [3] Strikingly, thiol‐ene click chemistry has been shown to provide very good performance for polymer coatings and surface modifications. Excellent spatial and temporal control as well as mild processing conditions have rendered this chemical route a sustainable strategy. [4] Particularly, metal‐free thiol‐maleimide chemistry displays a mild functionalization method applicable in the biomedical field. [5] Recently, engineering of recombinant spider silk resulted in a cysteine containing tag, ntagCys, at the amino‐terminal end of the protein's amino acid sequence. It could be shown that the thiol groups are surface exposed upon processing, opening the door to make use of thiol‐maleimide click reactions on the surface of the respective materials. [6]

Generally, spider silk materials display a combination of several favorable features such as chemical and mechanical stability, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and microbial resistance. [7] Applying biotechnological production routes, it is now possible to not only produce such materials in sufficient amount and high purity, but also to engineer spider silk for developing a huge variety of different silk‐based proteins with customized functionality. [8] Recent studies have shown the applicability of copper‐catalyzed click chemistry with recombinant spider silk proteins based on silk of the nursery‐web of Euprosthenops australis. Therein, azide side chains were introduced into the silk opening the door for simply conjugating various functional molecules to e.g. enhance cell adhesion properties or render silk proteins antibiotic. [9] Moreover, comparable click chemistry strategies were also conducted to modify regenerated silk fibroin derived from B. mori. [10]

Our silk toolbox is based on engineered Araneus diadematus fibroin (eADF). Recent studies in the field of regenerative medicine have successfully demonstrated tunable cell adhesion by modifying recombinant spider silk eADF4 with the cell binding peptide RGD. [11] Furthermore, mechanical properties could significantly be enhanced by adding nonrepetitive terminal domains to the amino acid sequence to induce dimerization of the respective proteins. [12] Intrinsic microbe repellency of negatively charged eADF4(C16) could be switched off, simply by changing the sequence of the repetitive core domain resulting in neutral charge and thus change in the crystalline structure that is presumably responsible for microbe repellency. [13] Moreover, being able to exactly tune the surface net charge of silk particles, the formation of a biomolecular corona upon contact with body fluids can be controlled, which has significant impact on e.g. blood clogging. [14] Taken together, eADF4‐based silk materials display a growing family of tailored proteins addressing various functions.

Another important point that comes into play when targeting certain functional features of materials is morphology. Nanostructures with high surface areas are often required to maximize desired interactions of the functional material with its surrounding medium. Furthermore, designing multi‐component materials to synergistically make use of different physicochemical properties can be highly attractive or even required. One strategy to realize such composite approaches in a very defined spatial arrangement is the production of Janus structures. [15] Janus materials display a unique class of functional materials applying anisotropic side‐by‐side arrangement of at least two dissimilar components leading to a myriad of different chemical and physical properties.[ 15 , 16 ] The high potential of these materials has resulted in the production of many differing types of Janus particles such as spherical, cylindrical and fibrous, disc‐shaped, dumbbell‐shaped particles or capsules. [17] These materials have found applications as biosensors, [18] drug delivery vehicles, [19] in textiles [20] and wound dressings, [21] membranes, [22] electronic paper [23] or for catalysis and separations. [24] A subset of such hybrid materials, Janus fibers, has attracted increasing attention in recent years to be used in meshes and membranes that provide attractive functionality for a broad spectrum of applications such as moisture transport, [22b] or reshaping of active textiles, [25] water treatment via solar desalination [22a] and biomedical applications such as wound dressings [26] or drug delivery. [27] Moreover, Janus fibers can be produced (typically via electrospinning) with specific motifs, e.g. for selective binding of catalytic substances such as nanoparticles, e.g. for water splitting applications.[ 24a , 24b , 24c , 24d ]

The goal of this study was to make use of biotechnologically produced spider silk proteins with tailored functionality to selectively bind gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) in a fiber‐based side‐by‐side arrangement with high spatial resolution in the nanoscale as shown by the gain of electrical conductivity. Therefore, ntagCyseADF4(κ16) was first wet spun to evaluate the sufficiency of thiol chemical binding of surface‐modified (maleimide) AuNPs. Linking AuNPs via thiol‐maleimide Michael addition displays the advantage of facile reaction conditions as well as copper‐free chemistry, which can be essential to avoid unfavorable copper‐based catalysis via Fenton reactions in the potential application of such fibers in biological systems. [28] The efficiency of applying cysteine for coupling reactions with recombinant spider silk was already demonstrated for ntagCyseADF4(C16). Coupling with fluorescein‐maleimide resulted in fluorescein‐conjugated spider silk proteins with 70–90 % coupling efficiency. [29] In this study, electrical conductivity measurements were applied to indicate high proximity of nanoparticles on the fiber surface. To achieve high surface‐to‐volume ratios increasing the surface functionality in relation to material use, electrospinning was performed with a side‐by‐side needle arrangement that allows to produce Janus fibers. These two component fibers were produced combining ntagCyseADF4(κ16) on the one side and eADF4(C16) on the other side. Strikingly, these protein variants are basically identical except for a difference in one amino acid residue in its 16 times repeated core motif (glutamic acid vs lysine) which alters the net charge of the protein from polyanionic to polycationic, and except for an additional amino terminal cysteine tag which allows to specifically bind maleimide‐functionalized AuNPs.

Functionalization of Spider Silk Fibers for Electrical Conductivity: First, we tested if thiol‐bearing ntagCyseADF4(κ16) allowed for sufficient coupling of AuNPs, which was considered to be highly dependent on exposure of the cysteine tag on the material's surface. Therefore, ntagCyseADF4(κ16) dissolved in hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) was wet spun into a mixture of acetone and ethanol (8 : 2) as a coagulation bath resulting in smooth fibers with diameters of 144±12 μm (Figure 1A, B). Subsequently, citrate‐stabilized Monomaleimido Nanogold particles were coupled to these wet‐spun fibers, and gold toning using LI Silver solution and LM GoldEnhance solution was performed based on previously established protocols. [6] As examined using SEM imaging, the procedure yielded a dense gold coverage on the fiber surfaces with particle diameters of 50±14 nm (Figure 1C). To analyze sufficient loading density, the impact of AuNP coating on electrical resistivity was determined via potentiostatic measurements. A 2 cm long piece of wet spun fibers was clamped between two metal plates at a fixed gap distance of 1 cm. The current was measured at ambient temperature while linearly increasing direct current (DC) voltage from 0 to 5 V at 0.2 V increments (Figure 1D). Non‐gold coated spider silk fibers acted as an isolator.

Figure 1.

SEM images of wet‐spun ntagCyseADF4(κ16) fiber (A) and the respective fiber surface before (B) and after (C) surface modification with AuNPs. Potentiostatic measurements were performed to examine the impact of AuNP coating on the electrical resistivity (D).

Based on the ohmic behavior together with the respective fiber dimensions, the resistivity was calculated as shown in Table 1. Significant drop of resistivity after AuNP binding confirmed the presence of AuNPs on the protein fiber's surface, and the pronounced electrical response of AuNPs indicated that the AuNP binding was dense enough. Considering, that only the gold layer significantly contributes to the fiber's conductivity, the resistivity of the gold layer alone was approximated assuming a thickness of 50 nm (AuNP diameter). With this simplification, the resistivity of the AuNP layer was calculated as 1.2 Ωmm2 m−1. This is still by a factor of ≈50 higher than the characteristic value for gold but considering that the layer consists of particles with less intermediate contact than a dense layer, this result is noteworthy. Furthermore, the data confirmed the applicability of thiol‐maleimide Michael addition as a strategy to selectively link functional agents to cysteine‐modified engineered spider silk fibers.

Table 1.

Impact of AuNP‐modification on electrical resistivity of wet‐spun ntagCyseADF4(κ16) fibers.

|

Fiber |

I max [mA] |

U max [V] |

R [Ω] |

ρ [Ωmm2 m−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

w.o. AuNP |

2.1E‐09 ±3.6E‐10 |

2.3E+00 ±9.7E‐01 |

1.1E+12 ±6.5E+11 |

6.7E+11 ±1.9E+11 |

|

with AuNP |

9.3E+00 ±7.0E‐01 |

4.5E+00 ±6.3E‐01 |

4.9E+02 ±3.3E+01 |

9.9E+02 ±2.0E+01 |

Janus Fiber Production: To demonstrate the possibility of downscaling fiber dimensions to achieve high surfaces and simultaneously realize complex functional structures with high spatial resolution in the nano‐regime, electrospinning was performed. Based on previous work in which electrospinning and extensive mechanical characterization of eADF4(C16) nanofibers was demonstrated, a dependence of mechanical properties on relative humidity (RH) was shown. At low RH (10 %), maximal fiber strength σ max was in the regime of 200 MPa, maximal fiber extensibility ϵ max around 5 % and the Young's modulus E at 6 GPa. In contrast, at 80 % RH σ max dropped to 51 MPa, E to 1.1 GPa, and ϵ max increased to 363 %. [30]

Here, the even more challenging formation of Janus fibers was approached. To exemplarily show the setup, only one half of a fiber should be functionalized. Three steps were required to achieve water stable half‐functionalized fibers—electrospinning of bi‐phasic fibers, post‐treatment, and AuNP‐coupling (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of a side‐by‐side electro spinning process to produce Janus fibers of two different spider silk proteins, and subsequent covalent binding of AuNPs on the phase, which is site‐specifically functionalized.

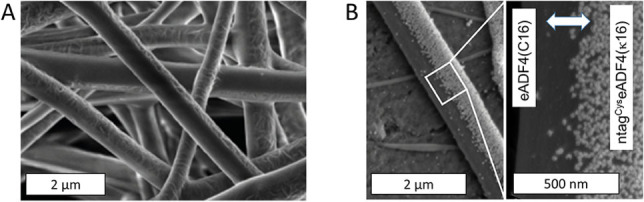

Initially, a conventional electrospinning setup (single syringe, one‐phase fiber mat) was modified to include two syringes allowing for the formation of two‐phase fiber mats. An additional ring electrode was used to inhibit double‐jet‐formation, keeping the two solutions together to stabilize Janus fiber formation. Non‐woven meshes were electrospun using a flow rate of 350 μL h−1 at each needle, a voltage of +22/−4 kV and a distance of 14 cm between the needle tip and the collector plate. To enforce interaction between the two materials, positively charged ntagCyseADF4(κ16) was spun on the one side and negatively charged eADF4(C16) on the other side allowing for charge–charge interactions at the interface. Strikingly, besides the cysteine‐tag, the proteins only differ in one amino acid in the 16 times repeated sequence motif, which is lysine in ntagCyseADF4(κ16) and glutamic acid in eADF4(C16). [31] Side‐by‐side electrospinning of these proteins at a concentration of 100 mg mL−1 from HFIP resulted in Janus fibers with diameters of 0.68±0.16 μm (see Figure 3A), and fiber production rate was calculated to be more than 40 m s−1. Considering the use of HFIP as solvent, which is known to be a strong denaturing agent, [32] as‐spun fibers displayed predominantly amorphous secondary structure rendering them water‐soluble. Consequently, post‐treatment was applied to increase protein crystallinity resulting in water‐stable fibers, which is an important prerequisite for applying gold coupling with aqueous agents as well as for various other applications. Post‐treatment was tested with three different agents (100 % ethanol, 70 % ethanol and pure MilliQ water) by vapor annealing of samples at 60 °C for 4 h. Secondary structural changes were determined applying FTIR spectroscopy and quantified via Fourier Self Deconvolution (FSD) (Figure 2 and Figure S1).

Figure 3.

SEM images of electrospun Janus fibers made of eADF4(C16) and ntagCyseADF4(κ16) before (A) and after (B) coupling with gold nanoparticles.

Figure 2.

Impact of different post‐treatment agents on the secondary structure of electrospun silk Janus fibers. Data were obtained by quantification of FT‐IR spectra via FSD (n=9). Since both phases of the Janus fiber were made of almost identical proteins, the post‐treatment changes were homogeneous throughout the fibers.

For all three of the tested agents, post‐treatment resulted in a significant increase in β‐sheet content at the expense of random coils and α‐helices. The percentage of turns remained more or less unchanged. It was expected that ethanol treatment causes an increase in β‐sheet formation via the desorption (and re‐adsorption) of water. [33] Nevertheless, the highest increase in β‐sheet formation was upon post‐treatment with pure MilliQ water. According to Huang et al., this can be traced back to a combination of reduced glass transition temperature in hydrated silk together with high temperature mobilizing the silk molecules to undergo conformational changes. [34] Based on this examination, MilliQ water was chosen as the most attractive system for further post‐treatment in this work.

Post‐treated fibers were subsequently coated with AuNPs following the same procedure as for gold coupling on wet‐spun fibers. Strikingly, only the thiol‐bearing ntagCyseADF4(κ16) displayed a high density of coupled AuNPs, whereas the eADF4(C16) side remained completely uncoated (Figure 3). The resistivity of the pure gold layer as obtained from the potentiostatic measurements can be used to calculate the theoretical resistivity of coated Janus fibers lying in the range of 16 Ωmm2 m−1. This result emphasizes the fact, that the efficiency of systems with surface functionality is highly dependent on volume‐to‐surface ratio.

Janus particles display high potential particularly in the biomedical field [35] as well as applications such as photochemical water splitting. [36] In this context, a recently published article by Marschelke et al. emphasized the need for biogenic and biocompatible Janus materials. [36] Addressing this demand, we could show, that highly specific side‐by‐side arrangements with nano‐resolutions can be created applying biotechnologically designed spider silk proteins with tailored chemical function. With the only difference between the two phases of the Janus fiber being the ntagCys terminal domain and the charge, homogeneous Janus fibers can be produced with only the terminal group acting as a specific binding motif. Mechanical analysis and SEM‐imaging of cast films made of eADF4(C16) and ntagCyseADF4(κ16) as well as eADF4(C16) combined with ntagCyseADF4(κ16) in a bilayer film confirmed high compatibility accompanied by similar mechanical properties, implying their excellent connectivity in a stable composite arrangement (Figure S2).

Spider silk proteins have been previously shown to display various attractive properties such as non‐toxicity, biocompatibility, and microbe‐resistance.[ 13a , 37 ] In combination with specific AuNP coating in the nanometer range novel electrical properties of silk fibers can be achieved. Besides applications such as photocatalytic water splitting via mineralization of titanium dioxide on the uncoated eADF4(C16) side, future work will focus on the biomedical use of such biphasic fibers, e.g. in the field of nerve regeneration. Combining the cell‐binding‐motif‐containing eADF4(C16)‐RGD with a conductive ntagCyseADF4(κ16)‐AuNP side could on the one hand promote neuronal cell adhesion and on the other hand enable electrical stimulation. Furthermore, electrospun fibers can be produced in an aligned manner providing morphological anisotropy for guided cell growth. Thus, combining intrinsically attractive material properties of recombinant spider silk with precisely positioned additional surface functionality in a fast process opens the door to a new class of multi‐functional nano‐ and micro‐materials.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) grant SPP1569 (SCHE603/15‐1 and 15‐2). Furthermore, the authors would like to thank Dr. Stephen Strassburg for his valuable comments on the first draft of this manuscript. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

G. Lang, C. Grill, T. Scheibel, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202115232; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202115232.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Latif R., Noor M. M., Yunas J., Hamzah A. A., Polymers 2021, 13, 2276; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Agboola O., Fayomi O. S. I., Ayodeji A., Ayeni A. O., Alagbe E. E., Sanni S. E., Okoro E. E., Moropeng L., Sadiku R., Kupolati K. W., Oni B. A., Membranes 2021, 11, 139; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c. da Silva T. R., de Azevedo A. R. G., Cecchin D., Marvila M. T., Amran M., Fediuk R., Vatin N., Karelina M., Klyuev S., Szelag M., Materials 2021, 14, 3549; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1d. Arefin A. M. E., Khatri N. R., Kulkarni N., Egan P. F., Polymers 2021, 13, 1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Makvandi P., Iftekhar S., Pizzetti F., Zarepour A., Zare E. N., Ashrafizadeh M., Agarwal T., Padil V. V. T., Mohammadinejad R., Sillanpaa M., Maiti T. K., Perale G., Zarrabi A., Rossi F., Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 583–611. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nemani S. K., Annavarapu R. K., Mohammadian B., Raiyan A., Heil J., Haque M. A., Abdelaal A., Sojoudi H., Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1801247. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Resetco C., Hendriks B., Badi N., Du Prez F., Mater. Horiz. 2017, 4, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pounder R. J., Stanford M. J., Brooks P., Richards S. P., Dove A. P., Chem. Commun. 2008, 5158–5160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herold H. M., Aigner T. B., Grill C. E., Kruger S., Taubert A., Scheibel T., Bioinspiration Biomimetics 2019, 8, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lang G., Herold H., Scheibel T., Subcell. Biochem. 2017, 82, 527–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kiseleva A. P., Krivoshapkin P. V., Krivoshapkina E. F., Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 00554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Harvey D., Bray G., Zamberlan F., Amer M., Goodacre S. L., Thomas N. R., Macromol. Biosci. 2020, 20, 2000255; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Harvey D., Bardelang P., Goodacre S. L., Cockayne A., Thomas N. R., Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1604245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Zhao H., Heusler E., Jones G., Li L., Werner V., Germershaus O., Ritzer J., Luehmann T., Meinel L., J. Struct. Biol. 2014, 186, 420–430; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Raynal L., Allardyce B. J., Wang X. G., Dilley R. J., Rajkhowa R., Henderson L. C., J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 8037–8042; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Das S., Pati D., Tiwari N., Nisal A., Sen Gupta S., Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 3695–3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Steiner D., Winkler S., Heltmann-Meyer S., Trossmann V. T., Fey T., Scheibel T., Horch R. E., Arkudas A., Biofabrication 2021, 13, 045003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heidebrecht A., Eisoldt L., Diehl J., Schmidt A., Geffers M., Lang G., Scheibel T., Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 2189–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Kumari S., Lang G., DeSimone E., Spengler C., Trossmann V. T., Lücker S., Hudel M., Jacobs K., Krämer N., Scheibel T., Mater. Today 2020, 41, 21–33; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Kumari S., Lang G., DeSimone E., Spengler C., Trossmann V. T., Lucker S., Hudel M., Jacobs K., Kramer N., Scheibel T., Data Brief 2020, 32, 106305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weiss A. C. G., Herold H. M., Lentz S., Faria M., Besford Q. A., Ang C. S., Caruso F., Scheibel T., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 24635–24643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Söz C. K., Trosien S., Biesalski M., ACS Mater. Lett. 2020, 2, 336–357. [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Agrawal G., Agrawal R., ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 1738–1757; [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Lattuada M., Hatton T. A., Nano Today 2011, 6, 286–308; [Google Scholar]

- 16c. Oh J. S., Lee S., Glotzer S. C., Yi G.-R., Pine D. J., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Walther A., Muller A. H. E., Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5194–5261; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Fan X. S., Yang J., Loh X. J., Li Z. B., Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2019, 40, 1800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 18a. Li J., Concellon A., Yoshinaga K., Nelson Z., He Q. L., Swager T. M., ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 1166–1175; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Li J., Savagatrup S., Nelson Z., Yoshinaga K., Swager T. M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11923–11930; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18c. Jurado-Sánchez B., Escarpa A., Electroanalysis 2017, 29, 14–23; [Google Scholar]

- 18d. Yánez-Sedeño P., Campuzano S., Pingarron J. M., Appl. Mater. Today 2017, 9, 276–288. [Google Scholar]

- 19.

- 19a. Li X. M., Zhou L., Wei Y., El-Toni A. M., Zhang F., Zhao D. Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15086–15092; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Zhang L. Y., Zhang M. J., Zhou L., Han Q. H., Chen X. J., Li S. N., Li L., Su Z. M., Wang C. G., Biomaterials 2018, 181, 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Synytska A., Khanum R., Ionov L., Cherif C., Bellmann C., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 1216–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.

- 21a. Yu D.-G., Yang C., Jin M., Williams G. R., Zou H., Wang X., Annie Bligh S. W., Colloids Surf. B 2016, 138, 110–116; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Yao Z.-C., Wang J.-C., Wang B., Ahmad Z., Li J.-S., Chang M.-W., J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2019, 50, 372–379; [Google Scholar]

- 21c. Yang J., Wang K., Yu D.-G., Yang Y., Bligh S. W. A., Williams G. R., Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 111, 110805; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21d. Lai W.-F., Huang E., Lui K.-H., Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 16, 77–85; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21e. Ji X., Li R., Jia W., Liu G., Luo Y., Cheng Z., ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 6430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.

- 22a. Xu W., Hu X., Zhuang S., Wang Y., Li X., Zhou L., Zhu S., Zhu J., Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1702884; [Google Scholar]

- 22b. Yan W. A., Miao D. Y., Babar A. A., Zhao J., Jia Y. T., Ding B., Wang X. F., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 565, 426–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hong B., Fan H., Cheng X.-B., Yan X., Hong S., Dong Q., Gao C., Zhang Z., Lai Y., Zhang Q., Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 16, 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- 24.

- 24a. Miao L., Liu G., Wang J., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 7397–7404; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24b. Wang Z., Lehtinen M., Liu G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12892–12897; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 13072–13077; [Google Scholar]

- 24c. Wang Z., Wang Y., Liu G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 1291–1294; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 1313–1316; [Google Scholar]

- 24d. Yang H.-C., Zhong W., Hou J., Chen V., Xu Z.-K., J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 523, 1–7; [Google Scholar]

- 24e. Ho C. C., Chen W. S., Shie T. Y., Lin J. N., Kuo C., Langmuir 2008, 24, 5663–5666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zakharov A. P., Pismen L. M., Soft Matter 2018, 14, 676–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luo Z., Jiang L., Xu C. F., Kai D., Fan X. S., You M. L., Hui C. M., Wu C. S., Wu Y. L., Li Z. B., Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 421, 127725. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lai W. F., Huang E., Lui K. H., Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 16, 77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.

- 28a. Sun Y. P., Liu H., Cheng L., Zhu S. M., Cai C. F., Yang T. Z., Yang L., Ding P. T., Polym. Int. 2018, 67, 25–31; [Google Scholar]

- 28b. Nieves D. J., Azmi N. S., Xu R., Levy R., Yates E. A., Fernig D. G., Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 13157–13160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Spiess K., Wohlrab S., Scheibel T., Soft Matter 2010, 6, 4168–4174. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lang G., Neugirg B. R., Kluge D., Fery A., Scheibel T., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 892–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Neubauer V. J., Trossmann V. T., Jacobi S., Dobl A., Scheibel T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 11847–11851; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 11953–11958. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Colomer I., Chamberlain A. E. R., Haughey M. B., Donohoe T. J., Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0088. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lang G., Jokisch S., Scheibel T., J. Visualized Exp. 2013, 75, 540492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang X. Y., Fan S. N., Altayp A. I. M., Zhang Y. P., Shao H. L., Hu X. C., Xie M. K., Xu Y. M., J. Nanomater. 2014, 2014, 682563. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Su H., Hurd Price C. -A., Jing L., Tian Q., Liu J., Qian K., Mater. Today Bio 2019, 4, 100033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marschelke C., Fery A., Synytska A., Colloid Polym. Sci. 2020, 298, 841–865. [Google Scholar]

- 37.

- 37a. Petzold J., Aigner T. B., Touska F., Zimmermann K., Scheibel T., Engel F. B., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1701427; [Google Scholar]

- 37b. Steiner D., Lang G., Fischer L., Winkler S., Fey T., Greil P., Scheibel T., Horch R. E., Arkudas A., Tissue Eng. Part A 2019, 25, 1504–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.