Abstract

In recent years, there has been much reflection on the measures used to assess and monitor contraceptive programming outcomes. The meaning and measurement of intention‐to‐use (ITU) contraception, however, has had less attention and research despite its widespread inclusion in many major surveys. This paper takes a deeper look at the meaning and measurement of ITU around contraception. We conducted a scoping review guided by the following questions: What is the existing evidence regarding the measurement of ITU contraception? What definitions and measures are used? What do we know about the validity of these measures? We searched databases and found 112 papers to include in our review and combined this with a review of the survey instruments and behavioral theory. Our review found growing evidence around the construct of ITU in family planning programming and research. However there are inconsistencies in how ITU is defined and measured, and this tends not to be informed by advances in behavioral theory and research. Further work is needed to develop and test measures that capture the complexity of intention, examine how intention differently relates to longer‐range goals compared to more immediate implementation, and demonstrate a positive relationship between ITU and contraceptive use.

Keywords: intention to use, contraception, scoping review, demand

INTRODUCTION

Understanding women's demand for contraception is essential for designing, implementing, and assessing responsive contraceptive programs. There are currently two ways to measure demand. The first is measuring women's unmet need for contraception, which is a top‐down population measure of need. The unmet need has been the main measure of demand since the 1970s, though it has undergone much critique and revision (Westoff 1978; Westoff and Ochoa 1991; Bradley et al. 2012).1 , 2 The second way to capture demand for family planning is to measure the intention‐to‐use (ITU) contraception, which has also been measured since the 1970s using items such as “I intended to do x.”3 Unlike unmet need, ITU draws on a woman's directly expressed desire to use contraception, her perception of risk to pregnancy, or her interest to use in the future (Ross and Winfrey 2001; Khan et al. 2015). This more person‐centered measure of demand directly captures women's stated preferences about using contraception and may actually better predict need and actual use (Ross and Winfrey 2001).

There have been advances in how we understand and measure intentions in the fields of social psychology and behavioral theory. Drawing on this work, we understand that intentions signal the end of a person's deliberation processes about what actions one will perform, how hard one will work for it, and how much effort one will apply to achieve the desired outcomes (Ajzen 1991; Gollwitzer 1993; Webb and Sheeran 2006; Gollwitzer and Sheeran 2008). Here, we use Triandis's (1980, 203) definition of intention: “Behavioral intentions are instructions that people give to themselves to behave in certain ways.” The nature of intention and its relationship to behavior has been theoretically mapped in a range of behavioral theories and models (e.g., the theory of planned behavior, self‐regulation theories, and phased models). Each theory has its own model of intention and its relationship to action. Whether the theory is based on goal striving theory of planned behavior, self‐regulation, or a staged model of behaviors (transtheoretical model, health belief model), they share a common understanding that intention is not a dichotomous variable, rather, it can be strong or weak, and it is conditioned, among other things, on time (i.e., intention to do immediately vs. at some point in the future) as well as proximity and attributes of the intended behavior. These advances in definition and measuring intention have yet to be applied to the construct of ITU in family planning.

In recent years as part of the post‐2012 Family Planning Summit renaissance, there has been much reflection on the measures used to assess and monitor contraceptive programming, for example, unmet need, additional users, demand satisfied, and continuation have been reexamined and refined (Cleland et al. 2014; Bradely and Casterline 2014; Dasgupta et al. 2017). Compared with other measures, ITU has received relatively little attention and it has not been subject to extensive independent research in the same way. The few scholars working on ITU argue that it merits further attention, concerning capturing ideational formation and demand for contraception and as a proximal predictor of future contraceptive use and it is time to get intentional about intent to use (Babalola et al. 2015; Hanson et al. 2015; Sarnak et al. 2020; Curtis and Westoff 1996; Callahan and Becker 2014). This scoping review presents the first attempt to synthesize what we know about ITU and hopes to start to fill this evidence gap. The following paper outlines the findings from a scoping review that examines the extent, range, and nature of the evidence on measuring ITU and the trends and gaps in the evidence with the aim of galvanizing research interest on this promising person‐centered measure of demand.

METHODS

Our aim was to examine the extent, range, and nature of the evidence on measuring ITU. We chose a scoping review because it allowed us to survey a topic that has yet to be examined comprehensively. This review methodology allowed us to encompass a range of evidence sources and uses a variety of study selection approaches. Our research methodology is based on Colquhoun et al. (2014) framework for scoping reviews, which includes (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results (also see Arksey and O'Malley 2005; Levac et. al. 2010).

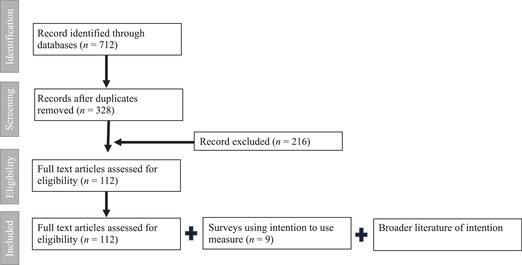

The review was guided by the questions: What is the existing evidence regarding the measurement of ITU contraception? What definitions and measures are used? What do we know about the validity of these measures? To identify the relevant studies, we used three data sources: (1) we searched relevant databases of the peer‐reviewed literature, (2) we reviewed survey instruments that collected ITU, and (3) we reviewed the broader literature. Figure 1 outlines our scoping review process.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of scoping review

To identify the peer‐reviewed literature, we ran search strings using synonyms of “intent to use” and “contraception” in PubMed and Web of Science. The search terms included (intent* OR intend*) AND (“to use”) OR (intent* OR intend* OR willingness) AND (contracept* OR “birth control” OR “family planning”). A total of 712 records were found and downloaded into an excel spreadsheet. We reviewed the spreadsheet for duplicate records and 384 were removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 328 records were reviewed against the following inclusion criteria: refers a measure of ITU; refers any modern contraceptives, including condoms and emergency contraception; published between 1990 and present; and published in English. After the review, we retained 112 papers for full paper review (see Table A3 for bibliography).

A data‐charting form was developed that detailed the variables we extracted. We abstracted data on the following categories:

Author;

Year of publication;

Country;

Study design;

Research objectives;

Target population;

Outcome of interest;

Definition of ITU;

Theoretical frameworks, if any;

How ITU was measured;

Findings.

We grouped the studies by the measures, theories, and the study design used and broad findings.

In addition to the peer‐reviewed sources of evidence, we also reviewed how different surveys measured ITU (see Table A1). To further contextualize the findings in the broader literature, we also read key papers on intentions from behavioral science. To provide a picture of the extent, range, and nature of existing evidence on ITU, we compare the findings from the peer‐reviewed search with those from two other data sources.

TABLE A1.

Intention to use measures in the survey instruments reviewed

| Survey Instrument (year) | Intention to Use Measure |

|---|---|

| CDC RH assessment toolkit in a conflict setting a (2011) | Do you think you will use a method to delay or avoid pregnancy in the next 12 months? |

| PMA2020 (2020) b | Female Questionnaire (Panel)

|

| UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys c | Not included |

| CDC Reproductive Health Surveys (2018) d |

|

| National Survey of Family Growth (US) e | Not included |

| NATSAL (UK) f | Not included |

RESULTS

Intention is a complex construct, and there is much debate about the nature of intention and if and how it relates to action. Behavioral theory distinguishes between types of intention, its properties, intensities, and determining variables. How we think intention works is central to how we operationalize it in measurement. After describing the characteristics of the evidence, in this section we detail the findings. The findings are grouped in relation to the definition of ITU, how the measure is used, the characteristics, and the reported results.

Characteristics of the Evidence

The peer‐reviewed papers are described in Table 1, together with a description of the research objective and study design for each paper alongside details about the theoretical framework, the ITU items used, and the reported results.

TABLE 1.

Details of included papers

| Year | Author | Study Design | Research objectives | Theoretical framework | ITU item | Reported results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 |

A. Joffe and S. M. Radius USA |

Cross‐sectional survey | Does self‐efficacy theory explain intent to use condoms of sexually and nonsexually active adolescents in the USA | Self‐efficacy theory | If you are planning to have sex, how likely is it that you will use a condom next time? |

|

| 1996 | S. L. Curtis and C. F. Westoff MOROCCO. |

Prospective Cohort Study Multivariate analysis |

Assess the predictive effect of contraceptive intentions on subsequent individual contraceptive behavior in Morocco | Not given |

“Do you intend to use a method to delay or avoid pregnancy at any time in the future?” “Do you intend to use a method within the next 12 months?” |

|

| 1996 |

S. J. Hiltabiddle GLOBAL |

Systematic review | To examine the factors associated with adolescent condom use | Health belief model | Not detailed |

|

| 1996 |

Minh Nguyet Nguyen, Jean François Saucier, and Lucille A. Pica CANADA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To determine whether attitudes and other variables are associated with intention to use condoms in sexually inactive male adolescents in Canada | Theory of reasoned action | Not detailed |

|

| 1999 |

E. Zimmers, G. Privette, R. H. Lowe, and F. Chappa USA |

Randomly assigned field experiment | To assess the impact of viewing a video on women with a willingness to try and to continue using female condoms in the USA | Social psychological perspective | Not detailed |

|

| 1999 | Sara Ann Peterson, NIGER |

Cross‐sectional survey Multivariate logistic regression |

To examine the differences between polygamous and monogamous spouses with regard to approval of birth control, desired family size, communication between spouses, and intention of using birth control in Niger | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2000 |

Marie Pierre Gagnon, and Gaston Godin USA |

Randomized control trial with vignettes | To assess the potential effects of new antiretroviral therapies on preventive sexual behaviors by exploring the intention of young adults to maintain condom use following a modification in the outcomes of HIV infection | Theory of planned behavior and theory of interpersonal behavior |

“If the occasion presents itself, I would use a condom with a new sexual partner”; “I would use a condom if I had a new sexual partner”; “I evaluate my chances of using a condom with a new sexual partner as …” |

|

| 2000 |

Ingela Lundin Kvalem and Bente Træen NORWAY |

Randomized control trial | To examine the relationship between contraceptive self‐efficacy and the intention to use condoms among Norwegian adolescents | Self‐efficacy and sexual script theory | Not detailed |

|

| 2001 |

Anna Fazekas, Charlene Y. Senn, and David M. Ledgerwood CANADA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To identify the variables that best predict whether or not young women intend to use condoms during their sexual encounters with new partners | Theory of planned behavior | Attitudes Toward Condoms Questionnaire (ATCQ) number of subscales tapping different dimensions of condom attitudes |

|

| 2001 |

John A. Ross and William L. Winfrey GLOBAL |

Cross‐sectional survey | To assess what proportion of women during experience unmet need for contraception and what proportion express an intention to use and, second, how much do these women account for all unmet needs in an entire population, and how much do they represent all women who intend to practice contraception | Not given | • Do you intend to use a method to delay or avoid pregnancy in the next 12 months? |

|

| 2001 |

S. Agha ZAMBIA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To examine intention to use the female condom among men and women in Zambia, who were exposed to mass‐marketing of the female condom | Not given |

“Do you intend to use the female condom in the future?” “Do you intend to use the male condom in the future?” |

|

| 2002 |

Anna Graham, Laurence Moore, Deborah Sharp, and Ian Diamond UK |

Cluster randomized controlled trial | To assess the effectiveness of a teacher‐led intervention to improve teenagers’ knowledge about emergency contraception in the UK | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2002 |

Sohail Agha and Ronan Van Rossem TANZANIA |

Cross‐sectional survey Path analysis is a regression based |

To assess whether a mass media campaign designed to promote the use of the female condom had an impact on intentions to use the female condom among men and women of reproductive age in Tanzania |

Diffusion of innovation | Not detailed |

|

| 2003 | Michael R. Spence, Kindra K. Elgen, and Todd S. Harwell USA. | Cross‐sectional survey | To identify factors associated with awareness of emergency contraception (EC), prior use of EC, and intent to use EC in the future among women at the time of pregnancy testing in the USA | Not given | “Would you use emergency birth control?” |

|

| 2003 |

Neeru Gupta, Charles Katende, and Ruth E. Bessinger UGANDA |

Pre–Post Delivery of Improved Services for Health (DISH) evaluation surveys | To examine the associations between multimedia behavior, change communication (BCC) campaigns, and women's and men's use of and intention to use modern contraceptive methods in target areas of Uganda | Theory of diffusion of innovation |

|

|

| 2003 |

T. K. Roy, F. Ram, Parveen Nangia, Uma Saha, and Nizamuddin Khan INDIA |

Cohort survey Logistic regression |

To examine intention to use a method as a measure of contraceptive demand | Not given |

|

|

| 2003 |

I. Mogilevkina, and V. Odlind UKRAINE |

Unmatched case‐control study | To investigate contraceptive practices and factors behind contraceptive preferences among Ukrainian women attending for abortion or gynecological health check‐up | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2004 |

Ruhul Amin, and Takanori Sato USA |

Pre‐ and postintervention and comparison sites | To systematically evaluate a school‐based comprehensive program to assess its impact contraceptive use, future contraceptive intention | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2004 |

Ruey Hsia Wang, Min Tao Hsu, and Hsiu Hung and Wang TAIWAN |

Cross‐sectional survey adolescent boys | To explore the predictors of contraceptive intention in adolescent males in Taiwan | Theory of reasoned action (TRA) and self‐efficacy |

|

|

| 2004 |

Margareta Larsson, Karin Eurenius, Ragnar Westerling, and Tanja Tydén SWEDEN |

Quasi‐experimental, pre‐ and postintervention with a control logistic regression |

To evaluate a community‐based intervention regarding emergency contraceptive pills (ECP), including a mass media campaign and information to women visiting family planning clinics |

Theory of diffusion of Innovation and the health belief model |

|

|

| 2005 |

Sara J, Newmann, Alisa B. Goldberg, Rodolfo Aviles, Olga Molina de Perez, and Anne F. Foster‐Rosales EL SALVADOR |

Cross‐sectional survey with postpartum adolescents | To describe demographics and contraceptive familiarity and use among postpartum adolescents in El Salvador | Not given | ‘‘Do you plan on using contraception in the future?’’ |

|

| 2005 |

Cynthia Rosengard, Jennifer G. Clarke, Kristen DaSilva, Megan Hebert, Jennifer Rose, and Michael D. Stein USA |

Cross‐sectional survey with women | To explore correlates of intentions to use condoms with main and casual partners among incarcerated women | Theory of planned behavior | “How often do you plan to use condoms in the next six months (following release from the Rhode Island Department of Corrections) with your [main/steady, casual/nonsteady] partner?” |

|

| 2005 |

Jennifer K. Legardy, Maurizio Macaluso, Lynn Artz, and Ilene Brill USA |

Randomized control trial A binomial regression analysis |

To assess whether participant baseline characteristics modified the effects of a skill‐based intervention promoting condom use | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2005 |

Daryl B. O'Connor, Eamonn Ferguson, and Rory C. O'Connor UK |

Cross‐sectional survey | To explore the extent to which male hormonal contraception is perceived as risky compared to other prevention behavior s and examine the effects of message framing on intentions to use hormonal male contraception | Prospect theory The theory of planned behavior (TPB) | Not detailed |

|

| 2006 |

Ekere James Essien, Gbadebo O. Ogungbade, Harrison N. Kamiru, Ernest Ekong, Doriel Ward, and Laurens Holmes NIGERIA |

Cross‐sectional study | To examine multiple predictors of condom, use among Uniformed Services Personnel in Africa in Nigeria | Self‐efficacy theory | Respondents were asked if there is a particular place, they go to get a condom. |

|

| 2006 |

Cees Hoefnagels, Harm J. Hospers, Clemens Hosman, Leo Schouten, and Herman Schaalma NETHERLANDS |

Cross‐sectional survey. | To investigate whether ITU condoms change when there is no pregnancy risk, to allow such changes to be predicted from an STD risk‐perception perspective with undergraduate students in the Netherlands | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2006 |

Hong Ha M. Truong, Timothy Kellogg, Willi McFarland, Mi Suk Kang, Philip Darney, and Eleanor A. Drey USA |

Examination of medical records of adolescents | To examine the changes between a choice of contraceptive methods before abortion and contraceptive intentions after abortion in the USA | Not given | Analysis of medical records—individual change in primary contraceptive choices before abortion compared to contraceptive intentions after abortion |

|

| 2007 |

Eun Seok Cha, Kevin H. Kim, and Willa M. Doswell KOREA |

Cross‐sectional survey | This study examined the mediating role of condom self‐efficacy between the parent‐adolescent relationship and the intention to use condoms in Korea | Theory of reasoned action | Not detailed |

|

| 2008 |

Ruey‐Hsia Wang, Chung‐Ping Cheng, and Fan‐Hao Chou TAIWAN |

Cross‐sectional survey | To investigate how social influences, attitude, and self‐efficacy operate together to influence contraceptive intention in Taiwan | Theory of reasoned action | “If you want to have sex within the next year, how strong is the possibility of your using contraceptives?” |

|

| 2008 |

Cynthia J, Mollen, Frances K. Barg, Katie L. Hayes, Marah Gotcsik, Nakeisha M. Blades, and Donald F. Schwarz USA |

Qualitative research | To explore the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of urban, minority adolescent girls about intention to use emergency contraception pills and to identify barriers to emergency contraception pill use among 15–19 Black adolescent girls in hospital settings in the USA | Theory of planned behavior | If they would be considering ECP in the future |

|

| 2008 |

M. Williams, A. Bowen, M. Ross, S. Timpson, U. Pallonen, and C. Amos USA |

Cross‐sectional survey Two structural equation models |

To investigate the contribution of a personal norm of condom‐use responsibility to the formation of intentions to use male condoms during vaginal sex among heterosexual African American crack cocaine smokers in Houston, Texas | Integrated behavior al model | Respondents were asked if s/he intended to use a male condom the next time s/he had vaginal sex with the named partner |

|

| 2008 |

Hee Sun Kang, and Linda Moneyham KOREA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To examine the intentions, knowledge, and attitudes of college students regarding the use of emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs) and condom in Korea | Theory of planned action | Not detailed |

|

| 2009 |

Omololu Adegbola, and AdeyemI Okunowo NIGERIA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To assess the intention to use postpartum contraceptives and factors influencing use among pregnant and puerperal women in Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), Lagos, Nigeria | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2009 |

G Anita Heeren, John B. Jemmott, Andrew Mandeya, and Joanne C. Tyler SOUTH AFRICA |

Prospective cohort study | To test the hypothesis that hedonistic and normative beliefs regarding sexual partners and peers, and control beliefs regarding condom‐use technical skill and impulse control would predict the intention to use condoms, which would predict condom use three months later among undergraduates at a university in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa | Theory of planned behavior | Not detailed |

|

| 2010 |

Sohail Agha PAKISTAN |

Cross‐sectional survey | To assess the perceived costs and motivations for specific contraceptive use behaviors among currently married women 15–49 and men married to women 15–49 in Pakistan | Synthesis framework | “Do you or your spouse intend to use this method in the next 12 months?” |

|

| 2011 |

Tina R Raine, Anne Foster‐Rosales, Ushma D. Upadhyay, Cherrie B. Boyer, Beth A. Brown, Abby Sokoloff, and Cynthia C. Harper USA |

A 12‐month longitudinal cohort study | To assess contraceptive discontinuation, switching, factors associated with method discontinuation, and pregnancy among women initiating hormonal contraceptives among adolescent girls and women aged 15–24 years attending public family planning clinics, USA | Theory of reasoned action | “How sure are you that you will use the baseline method selected for 1 year?” |

|

| 2011 |

Saima Hamid, Rob Stephenson, and Birgitta Rubenson PAKISTAN |

Cross‐sectional survey | To explore how young married women's involvement in the arrangements surrounding their marriage is associated with their ability to negotiate sexual and reproductive health decisions in marriage in Pakistan | Self‐efficacy theory | Not detailed |

|

| 2011 |

Katherine E. Brown, Keith M. Hurst, and Madelynne A. Arden UK |

Randomized Control Trials | To evaluate the impact of intervention materials, designed to enhance self‐efficacy and anticipated regret, on contraceptive behavior and antecedents of contraceptive use in a sample of adolescents in the UK | Theory of planned behavior | ‘‘I intend to use a method of contraception effectively every time I have sex’’ |

|

| 2011 |

Jongwon Lee, Mary Ann Jezewski, Yow Wu Bill Wu, and Mauricio Carvallo USA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To explore the relationship between acculturation and beliefs, attitudes, norms, and intention regarding oral contraceptive use among Korean immigrant women using acculturation in the USA | Theory of reasoned action | Intention to use oral contraceptives in the future |

|

| 2011 |

V. Khanal, C. Joshi, D. Neupane, and R. Karkee NEPAL |

Cross‐sectional survey | To find perceptions, practices, and factors affecting the use of family planning among abortion clients in Nepal | Intention to use FP after abortion |

|

|

| 2012 |

Joy Noel Baumgartner, Rose Otieno‐Masaba, Mark A. Weaver, Thomas W. Grey, and Heidi W. Reynolds KENYA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To explore the facility‐and provider‐level characteristics that may be associated with same day uptake or intention to use contraception after a Voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) visit, and contraceptive use three months later among youth clients in Kenya | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2012 |

Elizabeth Rink, Kris FourStar, Jarrett Medicine Elk, Rebecca Dick, Lacey Jewett, and Dionne Gesink USA |

In‐depth interviews | This study examines the extent to which age, fatherhood, relationship status, self‐control of birth control method, and the use of birth control influence young Native American men's intention to use family planning services in the USA | Not given | “How likely is it that you will seek birth control services in the next year?” |

|

| 2012 |

Elizabeth Rink, Kris FourStar, Jarrett Medicine Elk, Rebecca Dick, Lacey Jewett, and Dionne Gesink USA |

In‐depth interviews | To examine the influence of age, fatherhood, and mental health factors related to historical trauma and loss on young American Indian (AI) men's intention to use birth control in the USA | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2012 |

Shelly Campo, Natoshia M. Askelson, Erica L. Spies, and Mary Losch USA |

Cross‐sectional survey. | To examine how the extended parallel process model (EPPM) constructs of fear, susceptibility, severity, response efficacy, and self‐efficacy related to young adult women's intention to use contraceptives | EPPM | ‘‘How likely are you to use birth control the next time you have sexual intercourse?’’. |

|

| 2012 |

Catherine Potard, Robert Courtois, Mathieu Le Samedy, B. Mestre, M. J. Barakat, and Christian Réveillère FRANCE |

Cross‐sectional survey | To identify the determinants of the intention to use and actual use of condoms in a sample of French adolescents based on Ajzen's theory of planned behavior with adolescent boys and girls in France | Theory of planned behavior | I intend to use a condom every time I shall have sex with a new partner in the next three months |

|

| 2012 |

Jin Yan, Joseph T.F. Lau,; Hi Yi Tsui, Jing Gu, and Zixin Wang CHINA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To investigate the prevalence of male condom use and associated factors among monogamous STI female patients | Health belief model | Not detailed |

|

| 2013 |

Victor Akelo, Sonali Girde, Craig B. Borkowf, Frank Angira, Kevin Achola, Richard Lando, Lisa A. Mills, Timothy K. Thomas, and Shirley Lee Lecher KENYA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To analyze FP attitudes among HIV‐infected pregnant women enrolled in a Prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission (PMTCT) clinical trial among HIV positive pregnant women about future FP use in Western Kenya | Not given | Intention to use any form of FP in the future |

|

| 2013 |

Patrizia Di Giacomo, Alessia Sbarlati, Annamaria Bagnasco, and Loredana Sasso ITALY |

Cross‐sectional survey | To describe what puerperal women know about postpartum contraception and to identify their related needs and expectations in Italy | Not given | Intention to use contraception in the postpartum period |

|

| 2013 |

Rajesh Kumar Rai, and Sayeed Unisa INDIA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To examine the reasons for not using any method of contraception as well as reasons for not using modern methods of contraception, and factors associated with the future intention to use different types of contraceptives in India | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2014 |

Bernice Kuang, John Ross, and Elizabeth Leahy Madsen GLOBAL |

Cross‐sectional survey | To define high and low motivation groups by stated intention to use, past use, and unmet need, to determine how these groups differ in characteristics and in the region of residence in the African continent | Not given | “Do you think you will use a contraceptive method to delay or avoid pregnancy at any time in the future?” |

|

| 2014 |

Laili Irani, Ilene S. Speizer, and Jean‐Christophe Fotso KENYA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To examine the association between relationship‐level characteristics (desire for another child, communication about the desired number of children, and FP use) and contraceptive use and intention to use among nonusers in Kenya | Social ecological theory |

|

|

| 2014 |

Charles Picavet, Ineke van der Vlugt, and Ciel Wijsen THE NETHERLANDS |

Cross‐sectional survey Multivariate analysis |

To examine whether increased knowledge about ECPs may increase the intention to use these products among women in the Netherlands | Theory of reasoned action | Imagine you had intercourse without using contraception. You do not want to become pregnant. Would you take emergency contraception? |

|

| 2014 |

Susan Krenn, Lisa Cobb, Stella Babalola, Mojisola Odeku, and Bola Kusemiju NIGERIA |

Pre and post Cross‐sectional survey | To describe the activities designed and implemented by Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NUHRI) to meet the project's stated objectives and to illustrate how having a demand lens influenced programming decisions in ways that other family planning programs probably would not have considered in Nigeria | Ideation theory | Not detailed |

|

| 2014 |

Getachew Mekonnen, Fikre Enquselassie, Gezahegn Tesfaye, and Agumasie Semahegn ETHIOPIA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To assess the prevalence and associated factors of long‐acting and permanent contraceptive methods in Jinka town, southern Ethiopia | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2014 |

Allahna Esber, Randi E. Foraker, Maryam Hemed, and Alison Norris TANZANIA |

Cross‐sectional survey Multivariable logistic regression |

To study the effect of partner approval of contraception on intention to use contraception among women obtaining post abortion care in Zanzibar, Tanzania | Not given | “Do you think you will use a method of contra‐ ception in the future?” |

|

| 2014 |

Maricianah Onono, Cinthia Blat, Sondra Miles, Rachel Steinfeld, Pauline Wekesa, Elizabeth A. Bukusi, Kevin Owuor, Daniel Grossman, Craig R. Cohen, and Sara J. Newmann KENYA |

Pre‐ and postintervention survey | To determine if a health talk on family planning (FP) by community clinic health assistants (CCHAs) will improve knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions about contraception in HIV‐infected individuals in Kenya | The Information Motivation and Behavioral framework | Intention to initiate a new FP method |

|

| 2014 |

Md Mosfequr Rahman, Md Golam Mostofa, and Md Aminul Hoque BANGLADESH |

Cross‐sectional survey | Explores women's decision‐making autonomy as a potential indicator of the use of contraception in Bangladesh | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2014 |

Alem Gebremariam and Adamu Addissie ETHIOPIA |

Cross‐sectional study | To assess intention to use long‐acting and permanent contraceptive methods (LAPMs) and identify associated factors among currently married women in Adigrat town, Ethiopia | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2014 |

Mengistu Meskele and Wubegzier Mekonnen ETHIOPIA |

Cross‐sectional survey In‐depth interviews |

To examine the association between women's awareness, attitude, and barriers with their intention to use LAPMs among users of short‐term methods in Ethiopia | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2015 |

Tina R. Raine‐Bennett, and Corinne H. Rocca USA |

Psychometric evaluation | To develop and validate the psychometric properties of the Contraceptive Intent Questionnaire (CIQ), an instrument that can enable providers to identify young women who may be at risk of contraceptive nonadherence in the USA | Theory of reasoned action | Measures the latent construct of contraceptive intent and is designed to capture both conscious and unconscious factors that comprise a woman's predisposition to use contraception developed items |

|

| 2015 |

Hae Won Kim KOREA |

Cross‐sectional study with | To compare the ECP awareness of males and females and its associations with intention to use four other contraceptive methods (condoms, oral contraceptive pills, and withdrawal and rhythm methods) of unmarried university students in Korea | Theory of planned behavior |

I will choose this method myself; I will use this method consistently; I will choose this method without another's recommendation |

|

| 2015 |

Mishal S. Khan, Farah Naz Hashmani, Owais Ahmed, Minaal Khan, Sajjad Ahmed, Shershah Syed, and Fahad Qazi PAKISTAN |

Unmatched case‐control study | To quantitatively evaluate the effect of family members' opposition to family planning on intention to use contraception among poor women who have physical access to family planning services in two public hospitals in Karachi, Pakistan | Not given | Information on women's intention to use contraception in the future was solicited by first mentioning the local names of a list of 11 contraceptive methods and asking (one by one) if the woman was aware of it (knowledge of contraception assessment) and then asking whether they intend to use any form of contraception in the near or distant future |

|

| 2015 |

Jongwon Lee, Mauricio Carvallo, and Taehun Lee USA |

Psychometric evaluation | To evaluate the psychometric properties of a measure of attitudes and subjective norms toward OC use among Korean American women in the USA | The theory of reasoned | Not detailed |

|

| 2015 |

Sadaf Khan, Breanne Grady, and Sara Tifft GLOBAL |

Cross‐sectional survey | To describe a demand estimation exercise conducted in response to an initiative to introduce Sayana Press in 12 countries in Sub‐Saharan Africa and South Asia | Not given | ||

| 2015 |

Echezona E. Ezeanolue, Juliet Iwelunmor, Ibitola Asaolu, Michael C. Obiefune, Chinenye O. Ezeanolue, Alice Osuji, Amaka G. Ogidi, Aaron T. Hunt, Dina Patel, and Wei Yang, John E. Ehiri NIGERIA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To determine if (1) male partners’ awareness of, and support for, female contraceptive methods, and (2) influence of male partners’ contraceptive awareness and support on pregnant women's expressed desire to use contraception among pregnant women and their male partners in Nigeria | Not given | Male participants were asked the following questions among others: (a) are you aware of types of female contraceptive methods? (b) If yes, mention any methods that you are aware of. (c) Would you support your spouse's use of any form of contraception (men's support for contraception)? (d) If yes, what type? Female participants were asked the following: (a) Are you aware of types of female contraceptive methods? (b) Are you interested in using any contraceptive method? (c) If yes, which type(s)? |

|

| 2015 |

Stella Babalola, Neetu John, Bolanle Ajao, and Ilene S. Speizer KENYA AND NIGERIA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To examine differences and commonalities in the determinants of contraceptive use intentions in these two contexts with a special focus on ideational variables in Kenya and Nigeria | Ideation model of strategic communication and behavior change | Not detailed |

|

| 2015 |

Ramos Mboane, Madhav P. Bhatta MOZAMBIQUE |

Cross‐sectional survey | To examine the influence of a husband/partner's healthcare decision‐making power on a woman's intention to use contraceptives in Mozambique | Not given | Are you thinking about using any contraceptive method to delay or avoid getting pregnant in the future? |

|

| 2015 |

Jessica D. Hanson, Faryle Nothwher, Jingzhen Ginger Yang, and P. Romitti USA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To test and analyze direct and indirect measures of perceived behavioral control (PBC) in the context of birth control use among women. In addition, it aimed to examine the associations between PBC measures, intention, and actual birth control use in the USA | The theory of planned behavior |

|

|

| 2015 |

Fand Zavier and Shireen J. Jejeebhoy INDIA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To better understand the contraceptive practices of young abortionseekers aged 15–24 years in India | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2015 |

Christopher Godwin Udomboso, A. Y. Amoateng. and P. T. Doegah GHANA and NIGERIA |

Cross‐sectional study | To examine the effects of selected bio‐social factors on the intention to use contraception among never married and ever‐married women in Ghana and Nigeria | Not given | DHS |

|

| 2016 |

Yonatan Moges Mesfin and Kelemu Tilahun Kibret ETHIOPIA |

Systematic review and meta‐analysis | To summarize the evidence of practice and intention to use long‐acting and permanent family planning methods among women in Ethiopia | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2016 |

Matthew F. Reeves, Qiuhong Zhao, Gina M. Secura, and Jeffrey F. Peipert USA |

Prospective cohort study | To compare unintended pregnancy rates by the initially chosen contraceptive method after counseling to traditional contraceptive effectiveness in the same study population in the USA | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2016 |

Jennifer H. Tang, Dawn M. Kopp, Gretchen S. Stuart, Michele O'Shea, Christopher C. Stanley, Mina C. Hosseinipour William C. Miller, Mwawi Mwale, Stephen Kaliti, Phylos Bonongwe and, Nora E. Rosenberg MALAWI |

Prospective cohort study | To evaluate if implant knowledge and intent to use implant were associated with implant uptake of postpartum women in Malawi | Not given | The contraceptive methods she was planning to use in the first year after de‐ livery |

|

| 2016 |

Kebede Haile, Meresa Gebremedhin, Haileselasie Berhane, Tirhas Gebremedhin, Alem Abraha, Negassie Berhe, Tewodros Haile, Goitom Gigar, and Yonas Girma ETHIOPIA |

Cross‐sectional study | To assess magnitude and factors associated with a desire for birth spacing for at least two years or limiting childbearing and nonuse of LAPMs among married women of reproductive age in Ethiopia | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2016 |

Gareth Roderique‐Davies, Christine McKnight, Bev John, Susan Faulkner, Deborah Lancastle UK |

Cross‐sectional survey | To investigate women's intention to use long‐acting reversible contraception using two established models of health behavior in the UK | The theory of planned behavior and the health belief model | Not detailed |

|

| 2016 |

Maureen French, Alexandra Albanese, and Dana R. Gossett USA |

Retrospective cohort study Regression analysis |

To evaluate the effect of high‐risk pregnancy status on antepartum contraceptive planning and postpartum use among women delivering at a university hospital in the USA | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2016 |

Fentanesh Nibret Tiruneh, Kun Yang Chuang, Peter A. M. Ntenda, and Ying Chih Chuang ETHIOPIA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To explore the relationship of various predisposing, enabling, and need factors with the intention to use contraceptives, as well as the actual contraceptive behavior among women in Ethiopia. Intention to use contraception could be an important indicator of the potential demand for family planning services in Ethiopia | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2016 |

N. van der Westhuizen and G. Hanekom SOUTH AFRICA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To determine the quantity and quality of knowledge about the IUCD, and to evaluate its acceptability for future use in South Africa | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2017 |

Francesca L. Cavallaro, Lenka Benova, David Macleod, Adama Faye, and Caroline A. Lynch SENEGAL |

Cross‐sectional survey | To analyze FP trends among harder‐to‐reach groups (including adolescents, unmarried and rural poor women) in Senegal | Coale's framework of fertility decline | DHS measures used ITU as a proxy for willingness |

|

| 2017 |

Nadine Shaanta Murshid PAKISTAN |

Cross‐sectional survey | To examine the association between reports of IPV and the use of contraceptives in Pakistan | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2017 |

Veronika V. Mesheriakova and Kathleen P. Tebb USA |

Prospective cohort study | To examine the effectiveness of an iPad‐based application (app) on improving adolescent girls’ sexual health knowledge and on its ability to influence their intentions to use effective contraception among girls aged 12–18 years recruited from three school‐based health centers in California | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2017 |

Rajesh Kumar Rai, ETHIOPIA |

Cross‐sectional survey Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis | To examine whether the sex composition of living children and future desire for additional children were associated with the intention to use contraceptives among Ethiopian women aged 15–49 | Social cognitive approach | Not detailed |

|

| 2017 |

Elena Fuell Wysong, Krystel Tossone, and Lydia Furman USA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To examine whether low‐income inner‐city expectant women who intend to breastfeed make different contraceptive choices than those who intend to formula feed in expectant women age 14 years and older receiving prenatal care at MacDonald Women's Hospital the USA | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2017 |

Caroline Wuni, Cornelius A. Turpin, and Edward T. Dassah GHANA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To determine factors influencing current use and future contraceptive intentions of women who were attending child welfare clinics within two years of delivery in Sunyani Municipality, Ghana | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2018 |

Amy G. Bryant, Ilene S. Speizer, Jennifer C. Hodgkinson, Alison Swiatlo, Siân L. Curtis, and Krista Perreira USA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To understand practices, preferences, and barriers to the use of contraception for women obtaining abortions at clinics in North Carolina. | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2018 |

Victoria Shelus, Lauren VanEnk, Monica Giuffrida, Stefan Jansen, Scott Connolly, Marie Mukabatsinda, etc RWANDA |

Mixed method study | To explore the impact of a serial radio drama on fertility awareness and other factors in Rwanda | Not given |

|

|

| 2018 |

Bola Lukman Solanke, Olufunmilola Olufunmilayo Banjo, Bosede Odunola Oyinloye, Soladoye Sunday Asa NIGERIA |

Cross‐sectional survey Unadjusted multinomial logistic regression |

To examine the association between grand multiparity and intention to use modern contraceptives in Nigeria. | The theory of planned behavior | This information was sourced from currently married women who were not using a modern method. The variable has three categories, namely, (1) use later, (2) uncertain, and (3) does not intend to use. |

|

| 2018 |

Tom Lutalo, Ron Gray, John Santelli, David Guwatudde, Heena Brahmbhatt, Sanyukta Mathur, David Serwadda, Fred Nalugoda, and Fredrick Makumbi UGANDA |

Prospective cohort study | To estimate rates of an unfulfilled need for contraception, defined as having the unmet need and intent to use contraception at baseline but having an unintended pregnancy or with persistent unmet need for contraception at follow up of sexually active nonpregnant women with unmet need for contraception in Uganda | Not given | “Do you intend to use any contraceptive method between now and your next pregnancy?” |

|

| 2018 |

Sumitra Dhal Samanta, Gulnoza Usmanova, Anjum Shaheen, Murari Chandra, and Sunil Mehra INDIA |

Cross‐sectional survey | to describe the design, implementation, and baseline findings of “family‐centric safe motherhood approach among marginalized young married couples in rural India” with the primary aim to improve the reproductive health of just married and first time pregnant couples in India | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2018 |

Heba Mahmoud Taha Elweshahi, Gihan Ismail Gewaifel, Sameh Saad EL‐Din Sadek, and Omnia Galal El‐Sharkawy EGYPT |

Cross‐sectional survey | To estimate the level of unmet need for postpartum family planning one year after birth as well as identify factors associated with having unmet needs in Alexandria, Egypt | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2018 |

Teklehaymanot Huluf Abraha, Hailay Siyum Belay, Getachew Mebrahtu Welay ETHIOPIA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To assess intention to use modern contraceptives and to identify factors associated among postpartum women in Aksum town, Ethiopia | Not given | Not given |

|

| 2018 |

Zhongchen Luo, Lingling Gao, Ronald Anguzu, Juanjuan Zhao CHINA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To describe the intentions of and barriers to the use of long‐acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) in the postabortion period among women seeking abortion in mainland China | Not given |

“Would you like to use an intrauterine device (IUD) for contraception in the immediate postabortion period?” “Would you like to use an implant for contraception in the immediate postabortion period?” |

|

| 2018 |

Ana Luiza Vilela Borges, Osmara Alves dos Santos, and Elizabeth Fujimori BRAZIL |

Prospective cohort study | To examine the effect of pregnancy planning status in the concordance between intention to use and current use of contraceptives among postpartum women primary health care facilities in São Paulo, Brazil | Not given | To assess women's intentions to use contraceptives, we asked them while they were pregnant what type of contraceptive they intended to use after childbirth |

|

| 2018 |

Jody R. Lori, Meagan Chuey, Michelle L. Munro‐Kramer, Henrietta Ofosu‐Darkwah, and Richard M. K. Adanu GHANA |

Prospective cohort study | To examine the uptake and continuation of family planning following enrolment in group versus individual ANC in Ghana | Not given | Immediate postpartum intention to use family planning |

|

| 2018 |

Sebastian Eliason, Frank Baiden, Derek Anamaale Tuoyire, and Kofi Awusabo‐Asare GHANA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To better understand the issues by examining the sex composition of living children and how it is associated with reproductive outcomes such as pregnancy intendedness and intention to use postpartum family planning among women in a matrilineal area of Ghana | Not given | The intention to adopt postpartum family planning (PPFP) |

|

| 2018 |

Bobby Kgosiemang and Julia Blitz BOTSWANA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To assess the level of knowledge, attitudes, and practices of female students with regard to emergency contraception at the University of Botswana | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2019 |

Philile Shongwe, Busisiwe Ntuli, and Sphiwe Madiba, ESWATINI |

Qualitative, Focus group discussions | To explore the views of Eswatini men about the acceptability of vasectomy | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2019 |

Natasha A. Johnson, Elena Fuell Wysong, Krystel Tossone, and Lydia Furman USA |

Pre‐ and postsurvey | To understand how women's prenatal infant feeding and contraception intentions were related to postpartum choices in of expectant women ‡14 years of age receiving care at MacDonald Women's Hospital, Cleveland, Ohio | Not given | Not recorded in the pretest, only posttest |

|

| 2019 |

Hailay Syum, Gizienesh Kahsay, Teklehaymanot Huluf, Berhe Beyene, Hadgu Gerensea, and Gebreamlak Gidey, and others ETHIOPIA |

Cross‐sectional study | To assess intention to use LAPMs and their determinants among short‐acting users in health institutions among women who are short‐acting contraceptive users that visited health institutions Aksum Town, North Ethiopia | Not given | Desire to use long‐acting and permanent contraception methods as reported by the study participant |

|

| 2019 |

Fauzia Akhter Huda, John B. Casterline, Faisal Ahmmed, Kazuyo Machiyama, Hassan Rushekh Mahmood, Anisuddin Ahmed, and John Cleland BANGLADESH |

Cross‐sectional survey |

To understand how Bangladeshi women's perceptions of a method's attributes are associated with their intention to use that method. To examine associations between 12 method attributes and intention to use the pill or the injectable in Bangladesh |

Not given | Intended to do so in the next 12 months and whether they intended to do so at any time in the future. |

|

| 2019 |

Aalaa Jawad, Issrah Jawad, and Nisreen A. Alwan GLOBAL |

Systematic review | To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions using social networking sites (SNSs) to promote the uptake of and adherence to contraception in reproductive‐age women | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2019 |

Sara Adelman, Caroline Free, and Chris Smith CAMBODIA |

Randomized controlled trial | To evaluate which characteristics collected at the point of abortion are associated with contraceptive use over the extended postabortion period for women in Cambodia | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2019 |

Ona L. McCarthy, Hanadi Zghayyer, Amina Stavridis, Samia Adada, Irrfan Ahamed, Baptiste Leurent, Phil Edwards, Melissa Palmer, and Caroline Free PALESTINE |

Randomized controlled trial | To estimate the effect of a contraceptive behavioral intervention delivered by mobile phone text message on young Palestinian women's attitudes towards effective contraception among women aged 18–24 years living in the West Bank, who were not using contraception. | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2019 |

Silas Ochejele,; Chris Ega, Muhammad Shakir Balogun, Patrick Nguku, Tunde Adedokun, and Hadiza Usman NIGERIA |

Cross‐sectional study | To determine the factors that affect the contraceptive intentions of women who survive SAMM in Kaduna State, northern Nigeria. | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2019 |

Crystal L. Moore, Alison H. Edie, Jennifer L. Johnson, and Eleanor L. Stevenson USA |

Pre‐ and postintervention survey | The LARC QI intervention Project aims were threefold: (1) increase knowledge about LARC by 50% among college students attending group educational sessions one month after implementation; (2) increase intention to use a LARC method by 20% among college students one month after the implementation of the LARC‐QI project, and (3) increase usage of LARC methods three months after implementation of the project in the USA | Not given | Not detailed |

|

| 2019 |

E. Costenbader, S. Zissette, A. Martinez, K. LeMasters, and N. A. Dagadu (Costenbader, et al. 2019) DRC |

Cross‐sectional survey | 18–22 college students in DRC | Theory of planned behavior | On the survey, respondents were asked how likely they were to use modern contraceptives in the future. This question was asked on a four‐point Likert scale, with one being extremely unlikely to use and four being extremely likely to use modern contraceptives in the future |

|

|

||||||

| 2019 |

Andrea L. DeMaria, Beth Sundstrom, Amy A. Faria, Grace Moxley Saxon, and Jaziel Ramos‐Ortiz USA |

Cross‐sectional survey | To assess combined oral contraceptive pill (COC) users’ intention to obtain LARC | Theory of planned behavior (TPB) | TPB factors were measured and adapted from Ajzen's Likert scales |

|

| 2019 |

Dana Sarnak, Amy Tsui, Fredrick Makumbi, Simon Kibira, and Saifuddin Ahmed UGANDA |

Cohort study | To assess the dynamic influence of unmet need on time to contraceptive adoption, as compared with that of contraceptive intentions and their concordance in Uganda | Not given | Whether they would use contraceptives in the future, and their responses were classified as (1) intend to use and (2) do not intend to use |

|

| 2020 |

Janine Barden‐O'Fallon, Jennifer Mason, Emmanuel Tluway, Gideon Kwesigabo, and Egidius Kamanyi TANZANIA |

Pre post intervention study (no control) | To assess the effect of providing revised injectable and HIV risk counseling messages on contraceptive knowledge and behavior during a three‐month pilot intervention in Tanzania. | Not given | Not detailed |

|

From 1990 to 1999, seven papers on ITU were published. This increased to 28 papers from 2000 to 2009, of which over half related to condom use. From 2010 to 2020, 76 papers on ITU were published, and more than 50 papers came out in between 2015 and 2020. Sixty‐eight papers used cross‐sectional study designs and 15 longitudinal studies using cohorts to look at the relationships between variables over time. There were 15 experimental and quasi‐experimental studies, seven of which were randomized‐control trials (RCTs). There were three mixed‐method studies, three qualitative studies, three reviews, and two studies of psychometric scales.

The surveys that we included contain the Demographic Health Surveys (DHS), the Measure Evaluation Family Planning, and Reproductive Health Indicators Database, CDC RH assessment toolkit in a conflict setting, PMA2020, Track20/FP2020, Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, Reproductive Health Surveys (CDC), Breakthrough Action Research Indicators, National Survey of Family Growth (US), and NATSAL (UK).

Synthesis of Results

What Theoretical Frameworks Are Used?

Of the 112 papers include, 67 papers did not state or explain how they understood intention worked. Twenty‐five papers used Azjen's (1991) theory of planned action or a variation of it, in which attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, influence an individual's intentions towards a given behavior; such intentions predict whether an individual engages in that behavior in the future (Nguyen, Saucier, and Pica 1996; Gagnon and Goden 2000; Fazekas, Senn, and Ledgerwood 2001; Wang et al. 2004; Rosengard et al. 2005; O'Connor, Ferguson, and O'Connor 2005; Cha, Kim, and Doswell 2007; Wang et al. 2008; Kang et al. 2008; Heeren et al. 2009; Raine et al. 2011; Brown, Hurst, and Arden 2011; Lee et al. 2011; Potard et al. 2012; Picavet, Vlugt, and Wijsen 2014; Raine‐Bennett and Rocca 2015; Kim et al. 2015; Lee, Carvallo, and Lee 2015; Hanson et al. 2015; Roderique‐Davies et al. 2016; Solanke, Oyinloye, and Asa 2018; Costenbader et al. 2019; DeMaria et al. 2019). Twelve papers referred to other behavioral theories of intention including the health belief model (three papers), diffusion theory (three papers), and ideation theory (two papers), or specific constructs like self‐efficacy (four papers). Seven of the papers used more bespoke models that were not easily categorized under established behavioral models, such as the social‐psychological perspectives (Zimmers et al. 1999), prospect theory (O'Connor, Ferguson, and O'Connor 2005), synthesis framework (Agha 2010); the extended parallel process model (EPPM) (Campo et al. 2012); social ecological theory (Irani, Speizer, and Fotso 2014); and the information motivation and behavioral framework (Onono et al. 2014) and integrated behavioral model (Williams et al. 2008).

How ITU Is Operationalized

Across the papers, there is no accepted definition or measure of intent to use contraception. Over 50 papers did not state the exact wording of the items and, of those that did, few of the measures were validated. There are two notable exceptions. Raine‐Barrett and Rocca 2015 (2015) developed the Contraceptive Intent Questionnaire (CIQ) that measures contraceptive intent among adolescent girls in the USA, based on a theory of reasoned action and necessity‐concerns framework. The CIQ has modest reliability and good internal validity. Lee, Carvallo, and Lee (2015) developed another measure for determining the degree to which Korean immigrant women in the USA intend to use oral contraceptives that was both valid and reliable.

Of the papers that did specify the exact wording used to measure ITU, twenty‐four used the items from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) or a slight variation of it. The way that the DHS measures are applied in these papers is not standard or consistent. We found that 10 papers used the question (or a variation of it), Do you think you will use a contraceptive method to delay or avoid pregnancy at any time in the future?, six papers used the question, Do you intend to use a method within the next 12 months, and eight papers used a combination of the two questions. Another 15 papers defined ITU in relation to a specific method (e.g., emergency contraceptive pill, condoms, and long acting and permanent methods (APM) or to a specific time frame (e.g., postdelivery or abortion),

Twenty papers drew on theory of planned/reasoned behavior to inform their items (Gagnon and Godin 2000; Fazekas, Senn, and Ledgerwood 2001; Wang et al. 2004, 2008; Rosengard et al. 2005, Williams et al. 2008; Kang and Moneyham et al. 2008; Raine et al. 2011; Raine‐Barrett and Rocca 2015; Brown, Hurst, and Arden 2011; Lee et al. 2015, 2011; Potard et al. 2012; Picavet, Vlugt, and Wijsen 2014; Kim et al. 2015; Hanson et al. 2015; Roderqiue‐Davies 2016; Costenbader et al. 2019; DeMaria et al. 2019). Five papers used bespoke theories to inform their measures (Campo et al. 2012; Irani, Speizer, and Fotso 2014; Onono et al. 2014; Agha 2010; Larsson et al. 2004). Of these items that were explicitly informed by theory, one‐third (seven papers) aligned with the DHS items.

How ITU Is Used

The review found that ITU has become increasingly popular over time. Of the 112 papers found in this scoping review, 92 papers treated ITU as a dependent variable (alone or in some combination with knowledge and attitudes, and contraceptive use). There are three broad ways that ITU has been used in the evidence found.

The first way ITU has been applied was to augment the current measures of unmet need. Several authors have incorporated information on women's future contraceptive intentions to distinguish contraceptive readiness of women with unmet needs (Moreau et al. 2019; Ross and Winfrey 2001; Roy et al. 2003; Cavallaro et al. 2017; Sarnak et al. 2020; Khan 2015; Callahan and Becker 2014; Moreau et al. 2019).

The second way ITU was used was to measure ideational formation and outcome for those developing and implementing behavior change programming. Twelve papers used ITU, as opposed to self‐reported contraceptive use, as the outcome measure for counseling and social and behaviour change communication (SBCC) interventions and programs. (Shelus et al. 2018; Amin and Sato 2004; Zimmers et al. 1999; Krenn, et al. 2014; Jawad, Jawad, and Alwan 2019; McCarthy et al. 2019; Moore et al. 2019; Graham et al. 2002; Agha and Van Rossem 2002; Brown, Hurst, and Arden 2011; Onono et al. 2014; Barden‐O'Fallon et al. 2020).

The final way ITU was used in the papers was to predict future use of contraception. Fifteen papers assessed the relationship and causal pathways between ITU and contraceptive use (Curtis and Westoff 1996; Kvalem et al. 2000; Roy et al. 2003; Ross and Winfrey 2001; Callahan and Becker 2014; Lori et al. 2018; Tang 2016; Johnson et al. 2019; Adelman, Free, and Smith 2019; Raine et al. 2011; Lutalo et al. 2018; Haile et al. 2016; Akelo et al. 2013; Potard et al. 2012; French, Albanese, and Gossett 2016). ITU was also used to identify the determinants that predict contraception use.

Reported Results

Where ITU augmented the current measures of unmet need, Sarnak et al. (2020) found that women classified as having unmet need were slower to adopt contraception than those without unmet need in Uganda; however, women intending future contraceptive use were significantly faster to adopt than those not intending. Women with no unmet need but intending to use had the highest rate of adoption. Two papers indicate that women move in and out of the unmet need grouping depending on a range of variables (Callahan and Becker 2014; Ross and Winfrey 2001).

Where ITU was used was to measure ideational change, 14 papers used ITU as an outcome measure to assess Social and Behavior Change programs (such as radio and TV shows, phone, iPad, mass and social media, and school and community‐based education). Two papers looked at specific counseling on long‐acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) and found that counseling was associated with increased ITU (Barden‐O'Fallen et al. 2020; Moore et al. 2019). The fact that only two papers looked at ITU in the context of counseling interventions reinforces an observation made by Raine et al. (2011): there has been little attention on how to support women with low intentions in clinical settings.4

Where papers used ITU to assess the relationship and causal pathways between ITU and use of contraceptives, five prospective cohort studies have found that intention to practice contraception is a strong predictor of subsequent use in Bangladesh, Ghana, India, Morocco, and the USA (Curtis and Westoff 1996; Roy et al. 2003; Callahan and Becker 2014; Lori et al. 2018; Tang et al. 2016; Johnson et al. 2019). Ross and Winfrey's (2001) secondary analysis of DHS data in 27 countries found that for each increase of one percentage point in stated ITU contraceptives, there was nearly a 1% rise in the actual use of contraceptives. ITU also has been found to have a positive relation to contraceptive continuation; Raine et al. (2011) and Adelman, Free, and Smith (2019) found that a higher intent to use a method was associated with a lower risk of discontinuation. However, five papers found null or negative associations between ITU and use (Lutalo et al. 2018; Hale et al. 2016; Akelo et al. 2013; Potard et al. 2012; French, Albanese, and Gossett 2016). In an RCT in Norway, Kvalem et al. (2000) found a relationship between adolescents’ actual use of condoms at the most recent occasion of sexual intercourse and their intention to do so the next time (Kvalen et al. 2000).

The majority of studies looked at ITU in cross‐sectional studies at national, facility, and household levels. The cross‐sectional studies explored the variables that were associated with ITU contraception and suggest that ITU contraception is affected by many personal and social variables. These can be grouped into broader categories: (1) socioeconomic variables such as social and economic factors that indicate a person's status within a community; and (2) behavioral variables, for example, an individual's knowledge and attitude (see Table A2). The socioeconomic variables had a positive relationship with ITU and included higher educational attainment, number of children, and partner's support for family planning. The behavioral variables that had a positive relationship with ITU included a positive attitude to contraception, support from those immediately around the person (such as partners and friends), knowledge about contraceptive methods, and previous experience using contraception. These studies, however, provide little information about the relations between the variables over time or the causal relationship between them.

TABLE A2.

Overview of variables’ relationship to ITU found in the studies

| Positive association with ITU | Negative association with ITU | |

|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic factors | ||

| Education | Baumgarter et al. 2012; Cavallaro et al. 2017; Kuang, Ross, and Madsen 2014; Adegbola and Okunowo 2009; Syum et al. 2019; Huda et al. 2019; Mekonnen et al. 2014; Tiruneh et al. 2016; Spence, Elgen, and Harwell 2003; Di Giacomo et al. 2013; Meskele et al. 2014; Kgosiemang and Blitz 2018; Udomboso et al. 2015 | |

| Number of children | Baumgarter et al. 2012; Cavallaro et al. 2017; Syum et al. 2019; Hamid, Stephenson, and Rubenson 2011; Luo et al. 2018; Adelman, Free, and Smith 2019; Ochejele et al. 2019; Babalola et al. 2015; Peterson 1999; Costenbader et al. 2019 | Solanke, Oyinloye, and Asa 2018; Udomboso et al. 2015 |

| Abortion | Adelman, Free, and Smith 2019; Mogilevkina and Odlind 2003; Truong et al. 2006; Francis and Jejeebhoy 2015 | |

| Unplanned pregnancy | Spence, Elgen, and Harwell 2003; Curtis and Westoff et al. 1996; Campo et al. 2012 | Borges et al. 2018 |

| Partner support for FP | Ezeanolue et al. 2015; Agha 2010; Abraha, Belay, and Welay 2018; Triuneh et al. 2016; Onono et al. 2014; Yan et al. 2012; Hiltabiddle 1996; Akelo et al. 2013; Williams et al. 2008; Esber et al. 2014 | |

| Married/partnered | Baumgarter et al. 2012; Newman et al. 2005; Akelo et al. 2013; Luo et al. 2018; Tiruneh et al. 2016; Legardy et al. 2005 |

Cavallaro et al. 2017 Essien et al. 2006 |

| Type of relationship/sexual frequency | Irani, Speizer, and Fotso 2014; Luo et al. 2018; Spence, Elgen, and Harwell 2003; Campo et al. 2012; Francis and Jejeebhoy 2015 | Yan et al. 2012 |

| Parity | Adegbola and Okunowo 2009; Rink et al. 2012; Rai et al. 2017; Mogilevkina and Odlind 2003; Babalola et al. 2015 | Picavet, Vlugt, and Wijsen 2014 |

| Age | Adegbola and Okunowo 2009; Syum et al. 2019; Hamid, Stephenson, and Rubenson 2011; Nangia et al. 2003 | Solanke, Oyinloye, and Asa 2018; Kuang, Ross, and Madsen2014; Spence, Elgen, and Harwell 2003 |

| household decision making | Syum et al. 2019; Hamid, Stephenson, and Rubenson 2011; Rahman, Mostofa, and Hoque 2014; Mboane and Bhatta 2015 | |

| Ideal family size | Kuang, Ross, and Madsen 2014; Tiruneh et al. 2016 | |

| RuraL | Solanke, Oyinloye, and Asa 2018; Kuang, Ross, and Madsen 2014 | |

| Income | Kuang, Ross, and Madsen 2014; Tiruneh et al. 2016 | |

| High‐risk pregnancy | French, Albanese, and Gossett 2016 | |

| Late marriage | Tiruneh et al. 2016 | |

| Breastfeeding | Udomboso et al. 2015; Fuell, Tossone, and Furman 2017 | |

| Violence | Murshid 2017 | |

| Urban | Cavallaro et al. 2017 | |

| Behavioral factors | ||

| Attitude to contraception (willingness to use) | Wang et al. 2008; Raine et al. 2011; Hitabiddle et al. 1996; Lee, Carvallo, and Lee 2015; Syum et al. 2019; Picavet, Vlugt, and Wijsen 2014; Krenn et al. 2014; Mollen et al. 2008; Potard et al. 2012; Fuell, Tossone, and Furman 2017; Wang et al. 2004; Fazekas, Senn, and Ledgerwood 2001; O'Connor, Ferguson, and O'Connor 2005; Kang and Moneyham 2008; Lee et al. 2011; Gebremariam and Addissie 2014; Meskele et al. 2014; DeMaria et al. 2019 | |

| Subjective norms (pressure from others) partner parents | Raine et al. 2011; Hitabiddle et al. 1996; Heeran et al. 2009; Khan et al. 2015; Lee, Carvallo, and Lee 2015; Rosengard et al. 2005; Akelo et al. 2013; Mollen et al. 2008; Williams et al. 2008; Gagnon and. Godin 2000; Esber et al. 2014; Abraha, Belay, and Welay 2018; Roderique‐Davies et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2004; Agha 2010; Babalola et al. 2015 | |

| Knowledge of method | Shongwe, Ntuli, and Madiba 2019; Cavallaro et al. 2017; Tang et al. 2016; Khan et al. 2015; Syum et al. 2019; Abraha, Belay, and Welay 2018; Mesheriako et al. 2018; Moore et al. 2019; Larsson et al. 2004; Mogilevkina and Odlind 2003; Di Giacomo et al. 2013; Babalola et al. 2015; Gebremariam and Addissie 2014; Nguyen, Saucier, and Pica 1996; Khanal et al. 2011; Meskele et al. 2014; Costenbader et al. 2019 | Newman et al. 2005; van der Westhuizen and Hanekom 2016 |

| Previous experience | Joffe and Radius 1993; Hitabiddle et al. 1996; Huda et al. 2019; Picavet, Vlugt, and Wijsen 2014; Rosengard et al. 2005; Akelo et al. 2013; Esber et al. 2014; Luo et al. 2018; Adelman, Free, and Smith 2019; Ochejele et al. 2019; Kvalem et al. 2000; Campo et al. 2012; Wuni, Turpin, and Dassah 2017 | |

| Perceived risk | Hitabiddle et al. 1996; Huda et al. 2019, Rosengard et al. 2005; Hoefnagels et al. 2006; Gagnon and Godin 2000; Elweshahi et al. 2018; Luo et al. 2018 | |

| Perceived control | Mollen et al. 2008; Potard et al. 2012; Roderique‐Davies et al. 2016; DeMaria et al. 2019; Hanson et al. 2015 | |

| Pregnancy intentions | Raine et al. 2011; Baumgarter et al. 2012; Rosengard et al. 2005; Luo et al. 2018; Spence, Elgen, and Harwell 2003; Gebremariam and Addissie 2014; Wuni, Turpin, and Dassah 2017 | |

| Self‐efficacy | Shelus et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2008; Gagnon and Godin 2000; Wang et al. 2004; Cha, Kim, and Doswell 2007; Babalola et al. 2015 | |

| Communication/discussion | Akelo et al. 2013; Shelus et al. 2018; Agha and Van Rossem 2002; Campo et al. 2012; Wuni, Turpin, and Dassah 2017; Agha 2001; Wang et al. 2004 | |

| Attitude to pregnancy | Picavet, Vlugt, and Wijsen 2014; Akelo et al. 2013; Rai et al. 2017; Agha 2010. | |

| Injunctive norms/ social norms | Shongwe, Ntuli, and Madiba 2019; Costenbader et al. 2019 | |

| What other people are doing | Mollen et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2004; Fazekas, Senn, and Ledgerwood 2001; Nguyen, Saucier, and Pica 1996 | |

| Knowledge of use | Essien et al. 2006; Heeran et al. 2009 | |

| Confidence/ease of use | Hitabiddle et al. 1996; Lee, Carvallo, and Lee 2015; Huda et al. 2019; Ochejele et al. 2019 | |

| Anticipatory regret | Gagnon and. Godin 2000 | |

| Perceived benefits | Roderique‐Davies et al. 2016 | |

| Convenience | Hitabiddle et al. 1996; Heeran et al. 2009 | |

| Personal norm | Williams et al. 2008 | |

| Social identity | DeMaria et al. 2019 | |

Several studies focused on ITU for a specific method: condoms (15 papers), LARC methods (14 papers), and emergency contraceptive pills (ECP; six studies). These studies suggest that intentions may vary by the contraceptive method under consideration. For example, anxieties about longer‐term effects may be relevant to LARCs but not to condoms. The assessment by Kim et al. (2015) of ITU multiple methods in Korea found possible influences of ECP awareness on ITU other contraceptives.

Another finding is that there can be degrees of intentions. Several studies attempted to decipher the strength of intention (Solanke, Oyinloye, and Asa 2018; Kim 2015). Using DHS data in Nigeria, Solanke, Oyinloye, and Asa (2018) found that certain background characteristics had degrees of association with ITU. Rural residence was associated with higher ITU and advanced reproductive age and religion (compared to no religion) were associated with lower ITU. This suggests that it is possible to distinguish degrees of intention that could be relevant to programming.

DISCUSSION

In this scoping review, we identified 112 peer‐reviewed journal articles, assessed nine surveys, and scoped the theoretical literature on intention from behavioral science. Our findings indicate that measures of ITU contraception are being used in a variety of ways and in much research, suggesting the importance and utility of this construct. It may be particularly relevant in assessing programs focused on ideational change and it may help distinguish between women within the category of unmet need. By synthesizing the evidence, five prospective cohort studies have found that intention to practice contraception is a strong predictor of subsequent use and suggests it has the potential to predict contraceptive uptake and use in its own right (Curtis and Westoff 1996; Roy et al. 2003; Callahan and Becker 2014; Lori et al. 2018; Tang et al. 2016; Johnson et al. 2019). However, its definition and operationalization have been underelaborated and inconsistent.

What is notable is that the current operationalization of ITU is driven by the relevant items in the DHS and disconnected from advances in behavioral science. In behavioral science, intentions signal the end of a person's deliberations about what actions one will perform, how hard one will work for it, and how much effort one will apply to achieve the desired outcomes (Ajzen 1991; Gollwitzer 1993; Webb and Sheeran 2006; Gollwitzer and Sheeran 2008). Sheeran (2002), among others, argues that moving from intention to action is complex and moderated by the type of desired behavior, the intention type, properties of intention, and cognitive and personality variables. Sheeran illustrates this complex relationship by grouping people into those with positive intentions who subsequently act (inclined actors), those who fail to act (inclined abstainers), those with negative intentions who do act (disinclined actors), and those with negative intentions who do not act (disinclined abstainers).

Different variables have been associated with the strength of intention and whether an intention will be realized. Take, for example, whether intentions are stable over time or whether the behavior predicted is a single action (Webb and Sheeran 2006; Sheeran 2002). A person's control over the behavior (e.g., they do not have the necessary knowledge, resources, opportunity, availability, or cooperation) and the potential for adverse social reaction can limit the realization of an intention (Sheeran 2002; Webb and Sheeran 2006). Moreover, intentions do not always successfully translate into behavior because committing to achieve a behavior does not necessarily prepare people to deal with the issues faced when trying to achieve it. Gollwitzer and Sheeran (2008) helpfully distinguish between a goal intention and an implementation intention. Goal intentions relate to what people plan to do some time in the future, whereas implementation intention is more specific in terms of when, where, and how one intends to achieve it. Implementation intentions tend to be a single action, whereas goal intentions tend to be the outcomes that can be achieved by performing a variety of single actions.

Distinguishing the type of intention is critical because implementation intentions are more likely to translate into behavior than goal intentions (Cohen 1992).5 Gollwitzer and Sheeran (2008) argue that goal intentions do not prepare people for dealing with the obstacles they face in initiating, maintaining, disengaging from, or overextending oneself in realizing their intentions. Whereas an implementation intention sets out the when, where, and how in advance, this kind of planning bridges the intention to behavior gap and increases the likelihood of intentions being realized. Take, for example, Joffe and Radius (1993), who see intention for condom use as several single actions linked with specific implementation intentions: to purchase or request condoms from a drug store or clinic; to convince their partner to use them and to use condoms correctly during intercourse. Calculated together, these assess intent to use condoms. Here, the intention is broken down into a set of single actions that specify the situation for performing an intended action.

These developments in behavioral theory are relevant to how we understand intention in contraceptive decision‐making and our findings of the mixed evidence about the causal relationship between intent to use and contraceptive use. A closer reading reveals that the studies that found a positive relationship between intention and use and those that found no relationships or negative relationships can be grouped by the types of intention they measured. The papers that found a positive relationship measured “implementation intention” questions, which specified a time frame and/or a specific method. The papers that did not find a relationship between ITU tended to capture goal intention through questions about intentions for contraceptive use in the unspecified future. These insights from behavioral theory merit further examination about the predictive ability of ITU using implementation intention or goal intention, as well as investigating other variables surrounding intention. Furthermore, more research is needed to examine if the degrees of intention related to socio‐demographic variations related to different types of intention, such as goal and implementation.

Behavioral theory has also shown that intention is a debated, layered, and phased construct. So it is surprising that most papers in this review did not specify how they understood intention to work and how it related to behavior. This conspicuous absence suggests that there are some implicit assumptions about the ITU construct in the family planning field. The most immediate assumption here is that there is already an accepted definition and measurement of ITU. This review clearly shows that this is not the case, even among the studies that used the more common DHS measures of ITU. This assumed definition of ITU is not informed by behavioral sciences, rather it is driven by legacies from theories of demographic transitions.

In demography, there is an assumed association between reproductive intentions toward smaller families and fertility decline, whether it is caused by changing material conditions or diffusion of ideas (Johnson‐Hanks 2008). We can trace the assumptions about ITU in the DHS measures back to Coale's (1973) “ready, willing and able” model that has become popular in describing the adoption of new forms of behavior and the subsequent generalization of these behaviors. Lesthaeghe and Vanderhoeft (2001) refined Coale's model so that the transitions were understood as a process of diffusion of ideas and technologies. The model argues that three intersecting preconditions are necessary for adopting new behavior: individual readiness, willingness, and ability. Here, the intention is linked with “readiness,” an individualistic rational‐cost benefit analysis of whether or not to have a child, and whether the benefits of preventing pregnancy compensate for the costs of using family planning. Thus utility of new behavior should be self‐evident, and the advantages must outweigh the disadvantages (Coale 1973; Lesthaeghe and Vanderhoeft 2001; Dereudde et al. 2016; Mannan and Beaujot 2006).