Abstract

Exercise and physical activity can improve bone strength and the risk of falls, which may offer benefits in the prevention and management of osteoporosis. However, uncertainty about the types of exercise that are safe and effective instigates lack of confidence in people with osteoporosis and health professionals. Existing guidelines leave some questions unresolved. This consensus statement aimed to determine the physical activity and exercise needed to optimise bone strength, reduce fall and fracture risk, improve posture and manage vertebral fracture symptoms, while minimising potential risks in people with osteoporosis. The scope of this statement was developed following stakeholder consultation. Meta-analyses were reviewed and where evidence was lacking, individual studies or expert opinion were used to develop recommendations. A multidisciplinary expert group reviewed evidence to make recommendations, by consensus when evidence was not available. Key recommendations are that people with osteoporosis should undertake (1) resistance and impact exercise to maximise bone strength; (2) activities to improve strength and balance to reduce falls; (3) spinal extension exercise to improve posture and potentially reduce risk of falls and vertebral fractures. For safety, we recommend avoiding postures involving a high degree of spinal flexion during exercise or daily life. People with vertebral fracture or multiple low trauma fractures should usually exercise only up to an impact equivalent to brisk walking. Those at risk of falls should start with targeted strength and balance training. Vertebral fracture symptoms may benefit from exercise to reduce pain, improve mobility and quality of life, ideally with specialist advice to encourage return to normal activities. Everyone with osteoporosis may benefit from guidance on adapting postures and movements. There is little evidence that physical activity is associated with significant harm, and the benefits, in general, outweigh the risks.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, Exercise, Hip, Spine, Bone density

Background

It is estimated that 137 million women and 21 million men have high osteoporotic fracture risk globally, with this prevalence expected to double in the next 40 years.1 Fractures of the hip and spine can lead to loss of independence, disability and reduced life expectancy.2 Vertebral fractures are associated with long-term pain and other physical and psychological symptoms,3–5 whereas hip fractures are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.6 7

Current approaches to reduce fracture incidence include identifying people with significant fracture risk and prescribing pharmaceutical treatment, using education and support to promote adherence to medication, and developing falls prevention strategies especially for those who are older and frailer.8 9 Additional preventive strategies include healthy eating with adequate calcium and vitamin D, not smoking or consuming excessive alcohol and being physically active in adolescence and young adulthood to maximise peak bone mass.8 9

Epidemiological and intervention studies provide evidence of a strong relationship between physical activity, exercise and bone health, with regular exercisers having a lower incidence of fracture.10 Exercise can both increase bone mineral density (BMD) and reduce falls risk. However, there is still uncertainty about whether increasing volume and intensity of exercise, especially in later life or when bone strength is compromised, will improve bone strength, and importantly, what type or intensity of exercise intervention is most beneficial.

Osteoporotic fractures may be precipitated by a fall or with loading during activity. People with osteoporosis and health professionals are thus concerned that physical activity could increase fracture risk, although evidence to support these concerns is limited. Uncertainty persists about what is appropriate and safe in people with, or at risk of, osteoporosis, and may be accompanied by concerns about liability. As a result, people significantly reduce activity levels, limiting both function and enjoyment.11 This may have important adverse implications for their bone health, falls and future fracture risk.

For the vast majority of adults and older adults, taking part in activities that promote muscle and bone strength is safe and will help to maintain or improve function, irrespective of age or health.12–14 Providing authoritative and effective guidance may prompt an increase in physical activity and exercise. This will have wider beneficial effects on physical, social and psychological health14 15 alongside physical literacy, including physical competence, knowledge and understanding, to engage in physical activities for life.16

There is no UK guidance on exercise and osteoporosis. Although there is international guidance on safe and effective exercise and physical activity for bone health, from the USA,17 Australia13 and Canada,18 some key questions remain unanswered. These include the appropriate intensity of exercise interventions for those with diagnosed osteoporosis, whether there are real harms from any particular types of exercises or activities, and whether or how to modify physical activity for specific ‘fracture risk’ groups.

Objective

The objective of this consensus statement is to provide guidance on the role of exercise and physical activity in the prevention and management of osteoporosis.

The specific aims are to:

Clarify the role of physical activity and exercise for optimising bone strength and reducing falls and fracture risk.

Clarify the role of physical activity and exercise in managing the pain and symptoms of vertebral fracture.

Review any safety issues of exercise for those with osteoporosis, to address fears of causing fractures (particularly in the spine) while engaging in exercise or day-to-day physical activities.

Promote confidence and a positive approach so that people with osteoporosis do more rather than less exercise and physical activity.

Ensure consistent advice for people with osteoporosis so that people can exercise safely and effectively.

The target population is people with osteoporosis, who have bone mineral density measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry in the osteoporotic range or a significant fracture risk based on a fracture risk assessment score, with or without fragility fracture. Separate consideration is made for those with vertebral or multiple low trauma fractures and for those who are living with frailty and are unsteady or experiencing falls. Physical activity includes any activity, whatever the purpose, that increases energy expenditure, while exercise is structured physical activity performed to enhance or maintain performance or health.

This document updates the principles underpinning previous guidance on exercise and physical activity and distils current research evidence for people with osteoporosis.19 This guidance is developed for clinicians, including physiotherapists and exercise practitioners, as well as policy makers, and is designed to inform clinical practice and policy.

Methods

Developing scope through stakeholder consultation

To determine the scope and content for the consensus statement, stakeholder consultations were undertaken in 2017. First, face-to-face stakeholder discussion groups were held. Two groups consisted of people with osteoporosis; both were recruited through the Royal Osteoporosis Society database of members in two UK areas of differing socioeconomic status (Camerton and Stoke-on-Trent). A further stakeholder group in Camerton involved exercise and health professionals, again recruited through local Royal Osteoporosis Society contacts and professional members. Discussions were facilitated by ZP, using a discussion guide (online supplemental appendix I), to explore perceptions of the importance and role of exercise, identify areas of uncertainty and to seek views on the provisional content framework for the consensus document. The discussions were audio-recorded, written field notes taken and a summary of the main discussion themes produced.

bjsports-2021-104634supp001.pdf (393.7KB, pdf)

Second, an online/telephone survey was distributed to people affected by osteoporosis and interested health professionals recruited through Royal Osteoporosis Society members, healthcare professionals and social media channels. Participants provided ‘free text’ responses about what they felt were the key issues and uncertainties about exercise and osteoporosis (online supplemental appendix II). These were entered into a spreadsheet and structured according to categories and themes.

Refining scope through exercise expert consultation

A UK Expert Exercise Steering Group (EESG) consisting of 12 clinical and academic experts developed the consensus statement (online supplemental appendix III). This group included four physiotherapists, three rheumatologists, three academics and an osteoporosis specialist nurse; all but one of whom were female. Nine were clinically active with mean (SD) 18 (13) years of clinical experience, and ten were research active with 18 (11) years research experience. A wider UK Exercise Expert Working group (EEWG) consisted of a further 16 experts: nine physiotherapists, two patient representatives, two patient advocates, an exercise instructor, nurse and physiologist; 13 female and 3 male (online supplemental appendix III). Experts were selected to provide relevant clinical, research expertise and/or lived experience, often through contacts of the Royal Osteoporosis Society clinical and scientific advisory committees, or professional bodies (such as the Chartered Society of Physiotherapists).

The scope was refined by the EESG by teleconference and email, and evidence synthesised. The scope and evidence were then reviewed in a full day, face-to-face meeting of the EESG and EEWG in London in September 2017. A summary was circulated, with all members invited to comment.

Literature search strategy

The EESG identified several international osteoporosis and falls prevention guidance documents, meta-analyses and systematic reviews. These have synthesised the published evidence, agreed key principles and reported evidence12 20–46 and consensus-based guidance.12 13 17 18 The EESG agreed a pragmatic approach to review and update existing literature reviews and that a further systematic review of all the scientific and clinical evidence was not indicated. We thus repeated the searches conducted in previous systematic reviews of exercise and BMD43; falls47 and outcomes after vertebral fracture.44

Limited literature was available on the adverse events and safety issues associated with physical activity and exercise for adults with osteoporosis and osteopenia so a systematic review was undertaken that has been published separately.48

Formulation of recommendations

Reviews of literature were circulated to the EESG and EEWG. It was agreed that, as there was inevitably limited evidence to answer some of the core questions, the statement would need to base some recommendations for best practice on agreed principles. It would also aim to provide some ‘standard responses’ to common questions to aid meaningful discussion between practitioners and the people they are treating or working with. Where appropriate, key statements or standard responses were agreed using discussion and modifying wording as needed to reach consensus across the EESG and EEWG, which was confirmed by email after each draft. Recommendations were made in each section based on either the evidence reviewed (marked E) or expert consensus (marked C) where limited or no research evidence was available and unanimous agreement across the EESG and EEWG was achieved.

The EESG then developed the draft statement and presented it for review by the EEWG at a second face-to-face meeting in London in March 2018. This involved more detailed discussion of the wording. Final changes were approved by email with each member of EESG and EEWG providing confirmation that they agreed with the final principles and recommendations.

Consultation strategy

The draft statement was endorsed by the Royal Osteoporosis Society clinical and scientific committee. It was disseminated to stakeholders, including partnership organisations (online supplemental appendix IV). Public consultation was sought (through the Royal Osteoporosis Society website) from September to October 2018. Feedback was collated on a spreadsheet according to the strong, straight and steady themes. Any changes were initially reviewed by the editorial group (DAS, SL, EMC, KB-W) before being circulated for discussion/agreement by expert groups. An online meeting of the EESG was then held in October 2018 to review all changes.

Results

Outcome of stakeholder consultation

Stakeholder meetings for those with, or at risk of, osteoporosis were attended by 27 people (25 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis with two of their spouses). The professionals’ stakeholder meeting was attended by 13 health or exercise professionals (four physiotherapists, three osteoporosis specialist nurses, three Pilates instructors and three health professionals with osteoporosis).

The stakeholder group discussions identified that people with osteoporosis viewed exercise and physical activity as very important with wide-ranging benefits on health and well-being, and areas of frustration, about being given no, conflicting or negative ‘don’t do’ exercise advice by health professionals. Areas of uncertainty, for both non-professionals and professionals alike included what exercise was ‘best’ and safe to improve specific and general bone and muscle strength, dependent on ability. People with osteoporosis wanted more specific information about exercise regimens to guide safe functional activity, and professionals wanted more information about how to tailor advice, dependent on patient characteristics.

A total of 880 stakeholders participated in the online survey. Of those who provided demographic information, >70% were aged between 56 and 75 years; 772 (94%) described their ethnic origin as ‘white’ and 782 (96%) said they were female. Most respondents were people with osteoporosis: 521 (61%) diagnosed from a bone density scan; 83 (10%) reported one spinal fracture and 114 (13%) reported more than one spinal fracture; 148 (17%) had other fragility fractures; 44 (5%) said they were less mobile and unaccustomed to regular exercise. One hundred and thirty-nine respondents (16%) were health professionals.

Of the respondents who provided specific queries, 44% wanted to know what exercise was effective for strengthening bones (including specific questions on type, intensity and duration, or site-specific exercise) and 38% wanted to know about the role of exercise in prevention or management of vertebral fractures. Over a third had questions about the safety of specific exercises, such as Pilates or yoga positions. Questions about equipment, including vibration platforms, were asked. There was substantial uncertainty about what exercise was effective or safe, from both health professionals and those with osteoporosis.

The preferred format for receiving information was leaflets (90%) online video clips (59%) and DVDs (36%).

Outcome of refining scope through exercise expert consultation

The EESG consideration of scope concluded that two key themes arose from stakeholder consultations: what exercise is effective in increasing bone strength, and what exercise is safe and appropriate for those with, or at risk of, vertebral fractures. Given that the majority of fractures result from a fall, the EESG added exercise for falls prevention as a further theme. User consultation in stakeholder discussion groups (as described above) was undertaken to identify acceptable terminology for these themes, resulting in the following:

Strong: physical activity and exercise to benefit bone strength;

Steady: physical activity and exercise to prevent falls;

Straight: physical activity and exercise to reduce risk of vertebral fracture, improve posture and manage symptoms after vertebral fracture.

Under each theme recommendations were specified for:

All people with osteoporosis. People with osteoporosis were defined here as someone with BMD in the osteoporosis range (a dual energy X ray absorptiometry (DXA) bone density scan measurement T-score <−2.5) or a significant fracture risk (based on fracture risk assessment) with or without fragility fractures (including vertebral).

People with vertebral fractures or multiple low trauma fractures (the latter group may be at more significant risk of vertebral fracture during exercise).

People living with frailty and unsteadiness or those experiencing falls.

Interventions of interest included exercise or other physical activity. Outcomes included BMD or other proxies of bone strength, falls, fracture incidence, spinal curvature/posture and pain related to vertebral fracture. Recommendations were intended to be applicable for community, primary and secondary care settings.

Literature search

The updated searches from previous systematic reviews of exercise and BMD,43 falls47 and outcomes after vertebral fracture44 yielded 35, 19 and 3 new trials, respectively.

Safety of exercise in people with osteoporosis or fragility fractures

Information from three sources was reported: observational and case studies reporting circumstances of osteoporotic fracture; reports of exercise interventions in people with osteoporosis; adverse event reporting from exercise interventions to increase bone strength and to reduce falls risk.

A few case studies described instances of vertebral fractures during horse riding or during a golfing mid-swing stroke.48 However, the majority of observational or non-randomised studies in people with osteoporosis did not report adverse events, apart from muscle soreness and joint discomfort.44 48 There were some reports of vertebral fractures associated with end-range, sustained, repeated or loaded flexion exercises, including sit-ups49 and some yoga positions involving extreme spinal flexion.50 One study reported fractures associated with rolling from prone to supine and dropping a weight on a foot.51

In exercise interventions designed to increase BMD, many studies did not report whether there were adverse events. Of 62 trials, 11 reported fractures48 over the course of the studies but rarely due to the intervention itself. Overall, 5.8% of intervention group participants sustained fractures compared with 9.6% of control group participants.48 In particular, there was no evidence of symptomatic vertebral fracture in association with impact exercise or moderate to high-intensity muscle-strengthening exercise.48 Closely supervised high-intensity resistance and impact training in osteoporotic men and women was associated with few adverse effects and no vertebral fractures.52 53 In a further study of strength, balance and daily moderate to vigorous physical activity in people with osteoporosis, adverse events (both falls and fractures) did not differ significantly between the control and the intervention groups.54 These trials demonstrate that exercise can be conducted even in those who already have osteoporosis.

In studies on exercise for fall prevention, only 27 out of 108 trials reported adverse events and only one study reported a (pelvic stress) fracture.21 There is some evidence that brisk walking increased fracture risk in a population already at risk of falls and fracture, who may therefore require strength and balance exercise to improve stability before embarking on brisk walking or fatiguing exercise.47

Overall, there is little evidence of harm, including fractures, occurring while exercising. Furthermore, cases that were identified comprised a mixture of people with and without osteoporosis (as defined by DXA). Exercise is therefore unlikely to cause a fracture (and specifically a vertebral fracture) and does not need to be adapted for those with osteoporosis according to fracture risk or low BMD (including osteoporosis or osteopenia determined by DXA).

Strong: physical activity and exercise to promote bone strength and prevent fractures

Research evidence underlying recommendations is summarised in online supplemental appendix V. This evidence was considered alongside previous guidance12 13 17 and EESG consensus to agree recommendations (Box 1).

Box 1. Recommendations for exercise to promote bone strength.

For all people with osteoporosis

Muscle-strengthening physical activity and exercise is recommended on two or three days of the week to maintain bone strength. [E]

For maximum benefit, muscle strengthening should include progressive muscle resistance training. In practice, this is the maximum that can be lifted 8–12 times (building up to three sets for each exercise). Lower intensity exercise ensuring good technique is recommended before increasing intensity levels. [E]

All muscle groups should be targeted, including back muscles to promote bone strength in the spine. [C]

Daily physical activity is recommended as a minimum, spread across the day and avoiding prolonged periods of sitting. [C]

In addition:

For people with osteoporosis who do not have vertebral fractures or multiple low-trauma fractures

Moderate impact exercise is recommended on most days to promote bone strength (eg, stamping, jogging, low-level jumping, hopping) to include at least 50 impacts per session (jogs, hops etc). [C]

Brief bursts of moderate impact physical activity should be considered: about 50 impacts (eg, 5 sets of 10) with reduced impact in between (eg, walk-jog). [C]

For people with osteoporosis who have vertebral fractures or multiple low trauma fractures

Impact exercise on most days at a level up to brisk walking is recommended, aiming for 150 minutes over the week (20 min per day). This a precautionary measure because of theoretical (unproved) risks of further vertebral fracture in this group. [C]

Individualised advice from a physiotherapist is recommended for both impact and progressive resistance training to ensure correct technique, at least at the start of a new programme of exercise or activity. [C]

For people with osteoporosis who are frail and/or less able to exercise

Physical activity and exercise to help maintain bone strength should be adapted according to individual ability. [C]

Strength and balance exercise to prevent falls will be needed for confidence and stability before physical activity levels are increased. In practice, falls prevention may be a priority. [C]

The combination of impact and progressive resistance training best promotes bone strength43 as reflected in other national guidance.12 13 17 18

Resistance exercise is ideally supervised to ensure good technique and minimise injury risk,13 18 with interventions starting with lower loads while correct technique is attained. For consistent gains, resistance exercise should be progressive—that is, loads gradually increased.55 The ultimate intensity recommended previously was 8–12 repetitions maximum (RM)18—that is, the maximum weight that could be lifted 8–12 times or 8 repetitions at 80–85% 1 RM13—that is, 80–85% of the maximum load that could be lifted just once. Both recommend increasing to two to three sets. EESG consensus was that recommending an 8–12 RM was easier to implement outside a formal laboratory setting, although supervised progressive resistance training at higher intensity is likely to have greatest effects on BMD.

Resistance exercises involving major muscle groups should be used to load skeletal sites at risk of osteoporotic fracture, such as the spine, proximal femur and forearm. This may be achieved through one exercise each for legs, arms, chest, shoulders and back using exercise bands, weights or body weight,18 or eight exercises targeting major muscle groups of the hip and spine, including weighted lunges, hip abduction/adduction, knee extension/flexion, plantar–dorsiflexion, back extension, reverse chest fly, and abdominal exercises13 (while avoiding loaded spinal flexion). The latter recommendation could be replaced by fewer compound movements, such as squats and dead lifts. Such activities should be performed on two or three days of the week. While evidence relates to progressive resistance training, performed usually in a formal exercise setting or using specialist equipment, such activities are undertaken by only a small proportion of the population.56 To enable activity, EESG consensus was that other sports or leisure activities that might promote muscle strength should also be encouraged, such as circuit training, rowing, Pilates or yoga, stair climbing, sit to stands, heavy housework or gardening and carrying shopping, although repeated or end-range flexion should be avoided in these activities (figure 1).

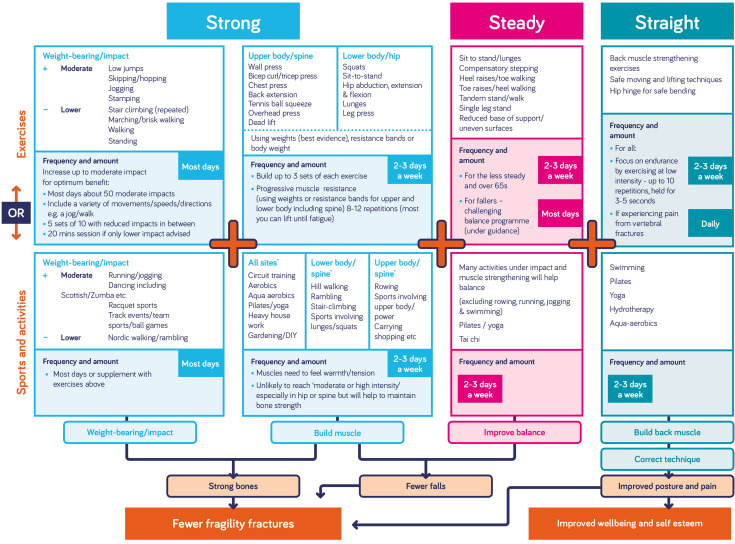

Figure 1.

Summary of exercise recommendations (from Royal Osteoporosis Society).63 Most research evidence is based on formal exercise. The suggested sports and activities include some with research evidence and some that may safely help engagement in activity and improve quality of life based on expert consensus.

Weightbearing or impact activity includes running, jumping, aerobics, some forms of dancing and many ball games and sport. As it does not necessarily require specialist facilities or equipment, this can be more accessible for many people than resistance exercise. Previous guidance recommends aerobic exercise for 30 min per day, 5 days a week,18 to comply with recommendations for other health outcomes, but this may not necessarily include exercise with sufficient gravitational loading to increase bone strength. Australian recommendations are more specific in suggesting impact exercise on 4–7 days per week, with each session including 50 jumps: 3–5 sets of 10–20 repetitions with 1–2 min rest between sets.13 They recommended high intensity (>4 times body weight (BW)), which may be encountered in gymnastics or drop jumps) for those without osteoporosis, and 2–4 BW for those at moderate risk of osteoporosis. Because of the lack of evidence of greater benefit of the high versus moderate intensity, EESG consensus was to recommend moderate impact exercise, such as jumps, skipping, hopping, running, higher impact forms of dance such as Scottish dancing or Zumba, or ball sports (figure 1) but not very high impact exercise such as landing from height. Consistent with Australian guidance,13 the recommended volume and frequency was ~50 moderate impacts interspersed with rest pauses, on most days.

People with vertebral fractures or multiple low trauma fractures, will have greater general bone fragility and a higher risk of further fracture. The expert group consensus was more cautious about moderate impact exercise in these people. A discussion about personal preferences and concerns is recommended to aid decisions about amending or excluding specific leisure or sports activities. An individualised progressive tailoring of intensity of both impact and muscle-strengthening exercise, under supervision, would often be appropriate. Gradually increasing impact up to ‘moderate’ could be appropriate depending on the number of vertebral fractures and symptoms experienced; other medical conditions, level of fitness or previous experience of moderate impact activity before the vertebral fracture need to be considered.

When starting an impact or muscle-strengthening programme, factors including general fitness, previous exercise and comorbidities should be considered in everyone. Building up gradually, employing good technique, and monitoring both progress and any adverse effects, is the best approach. Urinary incontinence may be a barrier to impact exercise so addressing stress incontinence may be a necessary step to being able to implement such an exercise programme. Learning best possible posture and correct technique is recommended as part of any progressive muscle resistance training. Balance and muscle strength training will be important for those at risk of falling before increasing to activities such as brisk walking.

Some sports and leisure activities involve an inherent risk of injurious impact, falling and fracture, such as contact sports, horse riding and skiing.48 However, for those who practice these regularly, the benefits provided by the activity, including enjoyment and benefits to muscle and bone strength, are likely to outweigh the risks unless people have had multiple fragility fractures or painful spinal fractures. People with osteoporosis may need some reassurance to continue with activities they enjoy.

Steady: exercise and physical activity to prevent falls

Research evidence is summarised in online supplemental appendix V and recommendations in Box 2. Substantial evidence suggests that targeted strength and balance training can prevent falls.21 Such specific exercise may be accessed by referral to a falls service for those who have experienced falls or are limiting activity though fear of falling.

Box 2. Recommendations for exercise to reduce falls.

For all people with osteoporosis (particularly those aged 65 or who have poor balance)

Physical activity or exercise to improve balance and muscle strength is recommended. [E]

Balance and muscle strength exercise (including activities such as Tai Chi, dance, yoga and Pilates) are recommended at least twice a week to reduce the risk of falls especially in older age. [C]

For people with osteoporosis who are already having falls

People who fall repeatedly or have started to avoid activity as a result of concern about falling, should be referred to a local falls service. [C]

Exercise interventions to prevent falls should be tailored to suit the individual to ensure that they challenge balance without increasing falls risk. [E]

Specific and highly challenging balance and muscle-strengthening exercises, supervised by a trained health or exercise professional, are recommended. [E]

Highly challenging balance and muscle strength training for 3 hours a week over at least 4 months is recommended—this could be around 25 min/day or 3×1 hour sessions a week. [E]

The Otago or Falls Management Exercise (FaME) programmes are recommended. [E]

Gradual progression from strength and balance exercises to higher impact exercise (such as brisk walking) is recommended for the frailer older adult to prevent an increase in falls risk. [C]

Exercise to strengthen back muscles and improve posture should be considered to reduce falls risk. [C]

Advice about reducing falls risk should be communicated in a positive way to be relevant and effective. [E]

Strength and balance training is recommended that is individualised, supervised by a health or exercise professional, highly challenging and conducted for 3 hours per week over at least 4 months, in line with previously published evidence.21 The consensus opinion was that following such exercise, weightbearing activities such as brisk walking could be introduced.

For people who are not eligible for a falls service, the consensus was that activities that improve balance and muscle strength, such as Tai Chi, dance, yoga or Pilates could be conducted, at least twice a week in line with physical activity guidance.

As kyphosis may increase fall risk, consensus was that exercise to strengthen back muscle (particularly of spinal extensors) and improve posture should also be recommended to reduce falls risk.

How professionals communicate the benefits of falls prevention exercise is important. Most people do not perceive themselves as fallers or as frail. People need to be motivated to take part in falls prevention exercise using appropriate language, such as ‘maintaining independence’ and ‘reducing the risk of fractures’ rather than ‘fall prevention’. Emphasising the importance of balance to feel confident and be able to enjoy other activities may also be useful.57

Straight: modifying physical activity and exercise to reduce risk of vertebral fracture, improve posture and manage symptoms after vertebral fracture

Given the limited evidence about how to reduce risk of vertebral fracture during activity, and the role of exercise in improving kyphosis and managing vertebral fracture (online supplemental appendix V), recommendations (Box 3) are consensus rather than evidence based and take into account previous consensus statements.

Box 3. Recommendations to reduce risk of vertebral fracture, improve posture and manage symptoms of vertebral fracture.

For all people with osteoporosis

A positive and reassuring approach is recommended to reduce fear, enhance confidence and control - ‘how to’ rather than ‘don’t do’, especially as most people with osteoporosis are unlikely to experience a vertebral fracture during these activities. [C]

Exercises to improve muscle strength in the back are recommended to improve posture and support the spine. Aim for exercises repeated 3–5 times and held for 3–5 s at least twice a week. [C]

-

Safe techniques for day-to-day moving and lifting are: [C]

‘Think straight’—a straight upper back (and keeping the neck in line with the spine) is the key principle for all movements that involve bending and lifting.

However, recognising the natural curves in the back, flexibility and function remain important and should be encouraged.

Safe lifting techniques are recommended rather than instructions such as ‘don’t lift’ or ‘only lift up to a specific weight’.

The ‘hip hinge’ is a simple technique for safe bending that facilitates this and can be practised and integrated into all day-to-day movements.

Always move in a smooth, controlled way within a comfortable range. Rotation (twisting) movements should be safe if performed smoothly and comfortably.

Engage abdominal muscles during movements.

Movements or exercise that involve sustained, repeated or end-range flexion should be modified or avoided. [C]

Any exercise that causes the back to curve excessively especially with an added load should be modified or avoided. [C]

People who are experienced, demonstrate flexibility in the spine and can manage the moves comfortably and smoothly, should be advised that they can continue with these activities as long as they are fit enough to manage them with ease. As a precaution, alternatives to exercises such as the ‘roll down ‘and ‘curl up’ in Pilates should be considered. [C]

Correct form and technique is important [C]

For people with osteoporosis with vertebral fracture

Prompt moving and lifting advice is recommended soon after painful vertebral fractures to reduce fear and maintain mobility and function. [C]

A referral to a physiotherapist will be helpful although some advice will also be important as soon as possible after a painful fracture. [C]

Daily exercises to strengthen back muscles (with a focus on endurance by exercising at low intensity), reduce muscle spasm, relieve pain, improve flexibility, and promote best possible posture are recommended with a referral to a physiotherapist for tailored advice. Aim for repeated exercise 3–5 times and held for 3–5 s. [C]

Maintaining physical activity and exercise is recommended to address pain and improve well-being. [C]

Professionals should explain how exercise interventions may help with back pain as people are fearful that exercise will make pain worse. [C]

-

Yoga and Pilates and similar exercise programmes should be considered to help with posture and pain through teaching form, alignment and muscle strength and relaxation. [C]

Classes should, if possible, by led by an instructor who has been trained to work with older individuals or those with osteoporosis and can amend exercises according to ability and range of movement.

Breathing and pelvic floor exercises are recommended to help with other symptoms that may be exacerbated by severe spinal kyphosis. [C]

Hydrotherapy should be considered to help improve quality of life. [C]

The risks of exercise were found to be relatively low6 and the benefits of exercise to health and well-being are substantial,12–14 so it is recommended that the emphasis is on being able to continue rather than prohibit exercise.

As reduced kyphosis may benefit pain, falls and vertebral fracture risk, exercises to improve posture (particularly by increasing the strength of spinal extensors) are recommended. Exercise can improve back extensor strength and posture, to counter the expected neuromuscular changes linked to weaker, less fatigue-resistant, muscles, combined with deficits due to spinal pathology that exacerbate back muscle weakness and postural deformity in people with osteoporosis.58 Improvements in back extensor muscle function are likely to underpin the improvements observed in standing balance.59 Different trials have used varying frequency and intensity of exercise. Overall, the consensus from the trials is that the initial dose and progression needs to be tailored to the individual to provide safe but incremental challenge and that the higher the dose and the longer the duration of the intervention the greater change observed, particularly in people over 70 years old.60

Avoiding activities that may provide excessive spinal load or flexion is a pragmatic approach to limit potential triggers of vertebral fracture, and more detailed strategies are supplied in previous guidance.18

People with pain following vertebral fracture may benefit from exercise to improve symptoms as well as helping to maintain usual activity. While such exercise should be delivered with expert advice, it is important that those with limited access to physiotherapy still have opportunity to benefit, so yoga or Pilates classes with an instructor with an understanding of appropriate exercise and movement for patients with vertebral fracture may be an alternative. Hydrotherapy improved quality of life61 so may be appropriate for improving vertebral fracture symptoms as those affected may find water-based exercise more comfortable, although it may not benefit bone strength.

Responses to consultation

A total of 155 comments were received. Minor changes were made in response to this feedback. In 2020/2021, the final updated statement was again reviewed and updated by the EESG to confirm that recommendations were still consistent with more recent evidence.

To support implementation, a range of resources were developed, which are available on the Royal Osteoporosis Society website: infographics and quick guide for health professionals62 63 as well as fact sheets and videos for the public.64

Discussion

Health professionals and people with osteoporosis had substantial uncertainty about the efficacy and safety of exercise for those with osteoporosis. However, evidence synthesis confirmed that physical activity and exercise have multiple potential benefits for those with osteoporosis: it may modestly benefit bone strength; improve muscle strength and balance and hence reduce falls risk and reduce kyphosis, which may benefit pain, self-esteem and risk of falls and fractures. Physical activity has a range of other health benefits. We conducted an updated and more thorough analysis of adverse events (particularly fractures) reported during exercise: harms have not been consistently reported, and although a small number of fractures have been reported during exercise, the benefits outweigh the risks. The level of evidence for people who have existing fractures is lower unfortunately; there is inconsistent evidence that exercise could benefit pain, physical function and quality of life. Many of our recommendations for this group are thus based on consensus rather than evidence.

We recommend several overarching principles. Physical activity and exercise have an important role in promoting bone strength, reducing falls risk and managing vertebral fracture symptoms, so they should be part of a broad approach that includes other lifestyle changes, combined with pharmaceutical treatment where appropriate. People with osteoporosis should be encouraged to do more rather than less. This requires professionals to adopt a positive and encouraging approach, focusing on ‘how to’ messages rather than ‘don’t do’. Although specific types or exercise may be most effective, even a minimal level of activity should provide some benefit. The evidence indicates that physical activity and exercise is not associated with significant harm, including vertebral fracture; in general, the benefits of physical activity outweigh the risks. Professionals should avoid restricting physical activity or exercise unnecessarily according to BMD or fracture thresholds as this may discourage exercise or activities that promote bone and other health benefits. Finally, people with painful vertebral fractures need clear and prompt guidance on how to adapt movements involved with day-to-day living, including how exercises can help with posture and pain. Anyone with osteoporosis may benefit from guidance on amending some postures and movements to care for their back. Supporting resources were produced.62–64

Bone strength

A combination of high load resistance exercise or weightbearing exercise with impact appears the most effective for bone strength. Moderate impact exercise may be more effective but lower impact (equivalent to brisk walking) was advised in those with vertebral fractures or multiple low trauma fractures. Several recent reviews confirmed the efficacy of resistance exercise65–67; one reported no benefit but was selective in the studies included.68 Consistent with previous guidance, we recommend that resistance exercise should progress to high intensity. Although some recent meta-analyses did not detect greater benefits from high than lower load resistance exercise,66 67 69 some of the interventions classified as high intensity were of more moderate loading, and substantial heterogeneity meant that it was not possible to detect significant differences according to intensity.66 67 One recent meta-analysis confirmed that high-intensity training was more effective than moderate intensity at the lumbar spine.70

Falls risk

A high proportion of fractures result from falls, and we recommend strength and balance training to reduce fall incidence, based on a large body of evidence. Exercise is effective in preventing fall-related injuries in people with osteoporosis,71 and in the broader population, participants randomised to exercise interventions had 26% fewer injurious falls, and 16% fewer fractures, than those randomised to control groups.72 This highlights that although health practitioners and people with osteoporosis may be concerned about vertebral fractures sustained during exercise that can directly be attributed to the exercise, it is important to balance this concern with the injuries prevented by exercise despite it being much harder to directly attribute an injury to not exercising.

Vertebral fracture prevention and management

We follow previous guidance in recommending safe lifting strategies and in particular avoiding loaded flexion or end of range movements, both during everyday life and exercise such as Pilates or yoga. We also recommend exercise to strengthen spine muscles, that may reduce pain and reduce kyphosis which may further reduce risks of falls and fractures.

Our recommendations for people with vertebral fracture are to undertake strength and balance training, although keep impact exercise to an intensity no more than brisk walking unless under instruction with personalised advice. Exercises to strengthen the spine muscles should be conducted and symptoms may also benefit from pelvic floor exercise or hydrotherapy. Given the limited evidence, these recommendations are consensus based. An updated Cochrane review on exercise after vertebral fracture found that evidence was still sparse and findings variable; no further studies had reported adverse events.45 Recent findings continue to be mixed; a home-based exercise intervention produced only modest improvements in physical function and no change in quality of life, pain or kyphosis in women with vertebral fracture; authors ascribed this to poor adherence to home-based exercise.73 A shorter resistance and balance training intervention improved strength, balance and fear of falling, which may reduce falls risk and increasing confidence to remain active.74 There is thus no later evidence that would affect the recommendations and the level of evidence about exercise in those with vertebral fracture is still low.

Exercise and pharmaceutical treatment

The level of evidence and magnitude of benefit from exercise is substantially lower than that for osteoporosis medication,8 with much less funding to exercise studies. Thus, exercise should be viewed as an adjunct rather than an alternative to pharmaceutical treatment where this is indicated. However, people with osteoporosis are keen to contribute to management of their osteoporosis with lifestyle approaches/exercise, and inactivity will increase the risk of falls and many other health conditions, so it is important to consider exercise even when pharmaceutical treatment is used.

Strengths and limitations

The evidence reviewed was primarily composed of targeted exercise interventions, often conducted in a laboratory or clinic. Although such well-controlled interventions are informative about the parameters of exercise that are effective, they may be less available to many people with osteoporosis (although a fall prevention exercise programme should be available to those at risk of falls). We took the pragmatic decision to recommend some types of exercise available in the community that seemed likely to provide the necessary training stimulus (figure 1), although the type and intensity of such exercise may be much more variable. Even if such exercise is less effective it may at least postpone inactivity-related decline.

This statement provides updated evidence consideration and application to the UK setting. Limitations to the process include that the stakeholder groups were predominantly white and female, although advice and access to exercise is needed for all populations. Furthermore, we have no health economic evaluation. Limitations to the strength of recommendations arise due to limited evidence available in some areas, including lack of studies with fracture as primary outcome, inconsistent reporting of adverse effects of exercise and limited number of interventions in men, ethnic minority groups and people with osteoporosis (although recent findings from LIFTMOR studies suggest that principles developed in theoretical studies and broader populations apply to those with osteoporosis). A further limitation is that many individual trials have small sample sizes, and so we are reliant on meta-analyses of data pooled from multiple studies. This may cause problems with exercise interventions: heterogeneity may arise through different types of exercise interventions, intensity, frequency and volume of exercise or population characteristics, such as age, health status and habitual activity. Even within one exercise mode, such as resistance training, differences in exercise intensity, or velocity of contraction, could affect efficacy. Furthermore, selection of studies for meta-analyses has differed in search strategies, inclusion and exclusion criteria and classifications of exercise, sometimes producing conflicting findings. We have not formally rated the quality of the reviews in our analysis. Given the highly localised effects of exercise on bone, the efficacy at specific skeletal sites may vary depending on the precise exercises used. Finally, most studies focused on BMD, but localised adaptations in bone mean that such changes may not parallel changes in bone strength.

Implementation

This consensus statement provides clear consistent advice for people living with osteoporosis and health professionals working with them about the evidence for, and safety of, exercise (see online supplemental appendix VI for further UK-specific guidance), supported by resources.62–64 To ensure effective implementation of the strong, steady and straight exercise approaches, the factors that act as both facilitators and barriers to implementation need consideration. These include appropriate and timely identification and management of people living with osteoporosis by primary and secondary care providers; provision of exercise interventions that conform to evidence-based requirements and the complexity of providing multiple exercise programmes for different long-term conditions in the context of limited resources; and uptake and adherence to exercise interventions (short-term and long-term). Osteoporosis exercise programmes, like other exercise programmes for older people and those with long-term conditions, need to be more than a prescribed set of exercises. They need to consider education and physical literacy, support and goal setting, motivation strategies, behaviour change techniques and take into consideration needs and preferences.75 76 For effective implementation of the strong, steady and straight exercise approaches an infrastructure for measuring and monitoring quality assurance and improvement is needed, to ensure ongoing fidelity (the right populations targeted by the right professionals, dose, frequency, intensity, challenge, resistance, etc.). We need to demonstrate impact to justify investment in osteoporosis programmes. This is increasingly important as the impact of COVID-19 and increased prevention and rehabilitation needs have the potential to jeopardise the offer of exercise for osteoporosis.

Conclusions

Key recommendations are that people with osteoporosis should undertake resistance and impact exercise to maximise bone strength; should take part in activities to improve strength and balance to reduce falls and undertake spinal extension exercise to improve posture, and potentially reduce pain levels caused by vertebral fractures, risk of falls and vertebral fracture. Although we recommend avoiding postures involving a high degree of spinal flexion (especially weighted) during exercise or daily life, and that people with vertebral fracture or multiple low trauma fractures should only exercise up to an impact equivalent to brisk walking, there is limited evidence of harms from exercise. People with vertebral fractures may benefit from exercise to reduce pain, improve mobility and quality of life, ideally with advice from a physiotherapist. Most importantly, inactivity should be avoided, physical activity encouraged and reassurance provided to counter the fear of moving that could detrimentally affect bone strength and health/quality of life more broadly.

Footnotes

Twitter: @KBrookeWavell, @LaterLifeTrain, @ProfKarenB, @emcbristol, @sarahdebiase, @AGILECSP, @zpaskins, @JonTobias1, @KateAWard17

Contributors: All authors were involved in conceptualising the paper, drafting, revisions and editing and final review. DAS and SL led consensus process. KB-W, DAS and SL led the drafting of the manuscript with contributions from KB, EMC, SDB, SA and ZP. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final paper.

Funding: Development of this statement was facilitated by funding by the Royal Osteoporosis Society, UK.

Competing interests: KB-W, KB; EMC, SDB, SA, ZP, KRR, RML, JHT, KAW, JW and SL have no competing interests to declare. DAS is a director of Later Life Training, a not-for-profit organisation that provides training and qualifications to health and fitness professionals working with frailer older people.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Odén A, McCloskey EV, Kanis JA, et al. Burden of high fracture probability worldwide: secular increases 2010-2040. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:2243–8. 10.1007/s00198-015-3154-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cooper C. The crippling consequences of fractures and their impact on quality of life. Am J Med 1997;103:S12–19. 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)90022-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Suzuki N, Ogikubo O, Hansson T. The course of the acute vertebral body fragility fracture: its effect on pain, disability and quality of life during 12 months. Eur Spine J 2008;17:1380–90. 10.1007/s00586-008-0753-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Drew S, Clark E, Al-Sari U, et al. Neglected bodily senses in women living with vertebral fracture: a focus group study. Rheumatology 2020;59:379–85. 10.1093/rheumatology/kez249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nazrun AS, Tzar MN, Mokhtar SA, et al. A systematic review of the outcomes of osteoporotic fracture patients after hospital discharge: morbidity, subsequent fractures, and mortality. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2014;10:937–48. 10.2147/TCRM.S72456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klop C, Welsing PMJ, Cooper C, et al. Mortality in British hip fracture patients, 2000-2010: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Bone 2014;66:171–7. 10.1016/j.bone.2014.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clynes MA, Harvey NC, Curtis EM, et al. The epidemiology of osteoporosis. Br Med Bull 2020;133:105–17. 10.1093/bmb/ldaa005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Compston J, Cooper A, Cooper C, et al. UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch Osteoporos 2017;12:43. 10.1007/s11657-017-0324-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gyle S. Scottish IGN. management of osteoporosis and prevention of fragility fractures. SIGN 142. Published 2020. http://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign142.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moayyeri A. The association between physical activity and osteoporotic fractures: a review of the evidence and implications for future research. Ann Epidemiol 2008;18:827–35. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reventlow SD. Perceived risk of osteoporosis: restricted physical activities? Qualitative interview study with women in their sixties. Scand J Prim Health Care 2007;25:160–5. 10.1080/02813430701305668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giangregorio LM, Papaioannou A, Macintyre NJ, et al. Too fit to fracture: exercise recommendations for individuals with osteoporosis or osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:821–35. 10.1007/s00198-013-2523-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beck BR, Daly RM, Singh MAF, et al. Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise prescription for the prevention and management of osteoporosis. J Sci Med Sport 2017;20:438–45. 10.1016/j.jsams.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Department of Health and Social Care . UK Chief Medical Officers’ physical activity guidelines, 2019. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/ukchief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf [Accessed 18 Sep 2019].

- 15. Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol 1982;37:122–47. 10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones GR, Stathokostas L, Young BW, et al. Development of a physical literacy model for older adults - a consensus process by the collaborative working group on physical literacy for older Canadians. BMC Geriatr 2018;18:13. 10.1186/s12877-017-0687-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kohrt WM, Bloomfield SA, Little KD, et al. Physical activity and bone health. Med Sci Sport Exerc 2004;36:1985–96. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000142662.21767.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giangregorio LM, McGill S, Wark JD, et al. Too fit to fracture: outcomes of a Delphi consensus process on physical activity and exercise recommendations for adults with osteoporosis with or without vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:891–910. 10.1007/s00198-014-2881-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chartered Society of Physiotherapy . Physiotherapy guidelines for the management of osteoporosis, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bansal S, Katzman WB, Giangregorio LM. Exercise for improving age-related hyperkyphotic posture: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:129–40. 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;1:CD012424. 10.1002/14651858.CD012424.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhao R, Zhao M, Zhang L. Efficiency of jumping exercise in improving bone mineral density among premenopausal women: a meta-analysis. Sports Med 2014;44:1393–402. 10.1007/s40279-014-0220-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhao R, Zhao M, Xu Z. The effects of differing resistance training modes on the preservation of bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:1605–18. 10.1007/s00198-015-3034-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao R, Zhang M, Zhang Q. The effectiveness of combined exercise interventions for preventing postmenopausal bone loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47:241–51. 10.2519/jospt.2017.6969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Kohrt WM. Erratum: Exercise and bone mineral density in premenopausal women: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (International Journal of Endocrinology). Int J Endocrinol 2013;2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Kohrt WM. Effects of ground and joint reaction force exercise on lumbar spine and femoral neck bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:177. 10.1186/1471-2474-13-177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gómez-Bruton A, Gónzalez-Agüero A, Gómez-Cabello A, et al. Is bone tissue really affected by swimming? A systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e70119. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Kohrt WM. Exercise and bone mineral density in men: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Bone 2013;53:103–11. 10.1016/j.bone.2012.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gómez-Cabello A, Ara I, González-Agüero A, et al. Effects of training on bone mass in older adults: a systematic review. Sport Med 2012;42:301–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martyn-St James M, Carroll S. A meta-analysis of impact exercise on postmenopausal bone loss: the case for mixed loading exercise programmes. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:898–908. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.052704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marques EA, Mota J, Carvalho J. Exercise effects on bone mineral density in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Age 2012;34:1493–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martyn-St James M, Carroll S. Meta-analysis of walking for preservation of bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Bone 2008;43:521–31. 10.1016/j.bone.2008.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martyn-St James M, Carroll S. Effects of different impact exercise modalities on bone mineral density in premenopausal women: a meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Metab 2010;28:251–67. 10.1007/s00774-009-0139-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martyn-St James M, Carroll S. Progressive high-intensity resistance training and bone mineral density changes among premenopausal women: evidence of discordant site-specific skeletal effects. Sports Med 2006;36:683–704. 10.2165/00007256-200636080-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martyn-St James M, Carroll S. High-intensity resistance training and postmenopausal bone loss: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2006;17:1225–40. 10.1007/s00198-006-0083-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kemmler W, von Stengel S, Kohl M. Exercise frequency and bone mineral density development in exercising postmenopausal osteopenic women. is there a critical dose of exercise for affecting bone? Results of the Erlangen fitness and osteoporosis prevention study. Bone 2016;89:1–6. 10.1016/j.bone.2016.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kelley GA, Kelley KS. Exercise and bone mineral density at the femoral neck in postmenopausal women: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials with individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:760–7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Simas V, Hing W, Pope R, et al. Effects of water-based exercise on bone health of middle-aged and older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access J Sport Med 2017;8:39–60. 10.2147/OAJSM.S129182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Foster C, Armstrong MEG. What types of physical activities are effective in developing muscle and bone strength and balance? J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls 2018;3:58–65. 10.22540/JFSF-03-058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Babatunde OO, Forsyth JJ, Gidlow CJ. A meta-analysis of brief high-impact exercises for enhancing bone health in premenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:109–19. 10.1007/s00198-011-1801-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bolam KA, van Uffelen JGZ, Taaffe DR. The effect of physical exercise on bone density in middle-aged and older men: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:2749–62. 10.1007/s00198-013-2346-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pinheiro MB, Oliveira J, Bauman A, et al. Evidence on physical activity and osteoporosis prevention for people aged 65+ years: a systematic review to inform the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2020;17:150. 10.1186/s12966-020-01040-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Howe TE, Shea B, Dawson LJ. Exercise for preventing and treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;2011:1–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Giangregorio LM, Macintyre NJ, Thabane L, et al. Exercise for improving outcomes after osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD008618 10.1002/14651858.CD008618.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gibbs JC, MacIntyre NJ, Ponzano M, et al. Exercise for improving outcomes after osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;7:CD008618 10.1002/14651858.CD008618.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kemmler W, von Stengel S. Dose-response effect of exercise frequency on bone mineral density in post-menopausal, osteopenic women. Scand J Med Sci Sport 2014;24:526–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sherrington C, Michaleff ZA, Fairhall N, et al. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1749–57. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kunutsor SK, Leyland S, Skelton DA. Adverse events and safety issues associated with physical activity and exercise for adults with osteoporosis and osteopenia: a systematic review of observational studies and an updated review of interventional studies. J Frailty, Sarcopenia Falls 2018;03:155–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sinaki M, Mikkelsen BA, Beth A. Postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis: flexion versus extension exercises. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1984;65:593–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sinaki M. Yoga spinal flexion positions and vertebral compression fracture in osteopenia or osteoporosis of spine: case series. Pain Pract 2013;13:68–75. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00545.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gold DT, Shipp KM, Pieper CF, et al. Group treatment improves trunk strength and psychological status in older women with vertebral fractures: results of a randomized, clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:1471–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Watson SL, Weeks BK, Weis LJ, et al. High-intensity exercise did not cause vertebral fractures and improves thoracic kyphosis in postmenopausal women with low to very low bone mass: the LIFTMOR trial. Osteoporos Int 2019;30:957–64. 10.1007/s00198-018-04829-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Harding AT, Weeks BK, Lambert C, et al. Exploring thoracic kyphosis and incident fracture from vertebral morphology with high-intensity exercise in middle-aged and older men with osteopenia and osteoporosis: a secondary analysis of the LIFTMOR-M trial. Osteoporos Int 2021;32:451-465. 10.1007/s00198-020-05583-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Giangregorio LM, Gibbs JC, Templeton JA, et al. Build better bones with exercise (B3E pilot trial): results of a feasibility study of a multicenter randomized controlled trial of 12 months of home exercise in older women with vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 2018;29:2545–56. 10.1007/s00198-018-4652-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1334–59. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Skelton DA, Mavroeidi A. How do muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities (MBSBA) vary across the life course, and are there particular ages where MBSBA are most important? J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls 2018;3:74–84. 10.22540/JFSF-03-074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, et al. Recommendations for promoting the engagement of older people in activities to prevent falls. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:230–4. 10.1136/qshc.2006.019802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Evstigneeva L, Lesnyak O, Bultink IEM, et al. Effect of twelve-month physical exercise program on patients with osteoporotic vertebral fractures: a randomized, controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:2515–24. 10.1007/s00198-016-3560-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Madureira MM, Takayama L, Gallinaro AL, et al. Balance training program is highly effective in improving functional status and reducing the risk of falls in elderly women with osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 2007;18:419–25. 10.1007/s00198-006-0252-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Barker KL, Newman M, Stallard N. Exercise or manual physiotherapy compared with a single session of physiotherapy for osteoporotic vertebral fracture: three-arm prove RCT. Health Technol Assess 2019;23:vii–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Devereux K, Robertson D, Briffa NK. Effects of a water-based program on women 65 years and over: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother 2005;51:102–8. 10.1016/s0004-9514(05)70038-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Royal Osteoporosis Society . Strong, steady and straight. An expert consensus statement on physical activity and exercise for osteoporosis, 2019. Available: https://strwebstgmedia.blob.core.windows.net/media/1hsfzfe3/consensus-statement-strong-steady-and-straight-web-march-2019.pdf [Accessed 01 Mar 2021].

- 63. Royal Osteoporosis Society . Strong, steady and straight: physical activity and exercise for osteoporosis. Quick guide: summary. Published online 2019. https://theros.org.uk/media/0o5h1l53/ros-strong-steady-straight-quick-guide-february-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 64. Royal Osteoporosis Society . Exercise and physical activity for osteoporosis and bone health, 2019. Available: theros.org.uk/exercise [Accessed 01 Apr 2021].

- 65. Shojaa M, Von Stengel S, Schoene D, et al. Effect of exercise training on bone mineral density in post-menopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. Front Physiol 2020;11:652. 10.3389/fphys.2020.00652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shojaa M, von Stengel S, Kohl M, et al. Effects of dynamic resistance exercise on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis with special emphasis on exercise parameters. Osteoporos Int 2020;31:1427–44. 10.1007/s00198-020-05441-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kemmler W, Shojaa M, Kohl M. Effects of Different Types of Exercise on Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. US: Springer, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mohammad Rahimi GR, Smart NA, Liang MTC, et al. The impact of different modes of exercise training on bone mineral density in older postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis research. Calcif Tissue Int 2020;106:577–90. 10.1007/s00223-020-00671-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Souza D, Barbalho M, Ramirez-Campillo R, et al. High and low-load resistance training produce similar effects on bone mineral density of middle-aged and older people: a systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Exp Gerontol 2020;138:110973. 10.1016/j.exger.2020.110973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kistler-Fischbacher M, Weeks BK, Beck BR. The effect of exercise intensity on bone in postmenopausal women (Part 2): a meta-analysis. Bone 2020;2021:115697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhao R, Bu W, Chen X. The efficacy and safety of exercise for prevention of fall-related injuries in older people with different health conditions, and differing intervention protocols: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Geriatr 2019;19:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. de Souto Barreto P, Rolland Y, Vellas B, et al. Association of long-term exercise training with risk of falls, fractures, hospitalizations, and mortality in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:394–405. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gibbs JC, McArthur C, Wark JD, et al. The effects of home exercise in older women with vertebral fractures: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2020;100:662–76. 10.1093/ptj/pzz188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Stanghelle B, Bentzen H, Giangregorio L, et al. Effects of a resistance and balance exercise programme on physical fitness, health-related quality of life and fear of falling in older women with osteoporosis and vertebral fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 2020;31:1069–78. 10.1007/s00198-019-05256-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cavill NA, Foster CEM. Enablers and barriers to older people’s participation in strength and balance activities: A review of reviews. J Frailty, Sarcopenia Falls 2018;03:105–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Spiteri K, Broom D, Bekhet AH, et al. Barriers and motivators of physical activity participation in middle-aged and older adults—a systematic review. J Aging Phys Act 2019;27:929–44. 10.1123/japa.2018-0343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bjsports-2021-104634supp001.pdf (393.7KB, pdf)