Abstract

Objective

To engage young adults (18–35 years of age) with life-limiting neuromuscular conditions, their parents, and health and community providers in the development of a public health approach to palliative care. A public health approach protects and improves health and wellness, maximises the quality of life when health cannot be restored and improves the quality, scope and accessibility of age-appropriate care and services.

Methods

Group concept mapping (GCM) was used to determine the most important priorities for these young adults. GCM involves three district phases: (1) brainstorming ideas, (2) sorting and rating ideas based on level of importance and (3) analysing and interpreting concepts maps. Online software was used to collect information for phases 1 and 2 and develop concept maps. In phase 3, a face-to-face workshop, participants analysed and interpreted the concept maps. The combination of online and face-to-face research activities offered the needed flexibility for participants to determine when and how to participate in this research.

Results

Through this three-phase patient engagement strategy, participants generated 64 recommendations for change and determined that improvements to programming, improvements to funding and creating a continuum of care were their most important priorities. Five subthemes of these three priorities and development of the concept map are also discussed.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates the unique perspectives and experiences of these young adults and offers recommendations to improve services to enhance their health and well-being. Further, these young adults were integral in the development of recommendations for system changes to match their unique developmental needs.

Keywords: chronic conditions, young adult, transition to adult care, patient participation, health care quality access and evaluation, palliative care

Introduction

With advances in medicine and technology, youth with progressive and life-limiting neuromuscular conditions (LLNMCs) are now living into adulthood1 and will require substantive specialised health and community support for their lifetime.2 While successful programmes have been developed to support youth with neuromuscular conditions in paediatric care,2–4 when they enter adult services, similar supports are not available. For example, young adults (YAs) have challenges finding adult healthcare providers with expertise in their conditions and accessing post-secondary education, vocational opportunities, financial support for caregivers, medical equipment (eg, power wheel chairs, ventilators, feeding equipment) and independent living.3–6

Lack of foresight about how to support these YAs has resulted in reactive rather than anticipatory and preventive care.7 8 Further, these YAs find that the resources and services offered when they enter adult services and programmes do not match their developmental needs, resulting in missed opportunities for them to do what is meaningful to them in their YA years, such as attend college and university, have meaningful vocation or work, and live independently.3 7 9 10 While more attention is now being focused on growing populations of older adults with complex and life-limiting conditions,2 YAs with shorter life spans are being overlooked.7 A holistic approach to care that provides access to requisite services to support their health needs and developmental goals is challenging but necessary.2 7

One type of care to consider is a public health approach to palliative care. This type of care focuses on anticipating and managing complex conditions over extended and unpredictable periods of time and addresses the numerous challenges and gaps to provide care to patients across multiple sectors.11 The public health approach has an enviable record of contributions to population health and addressing major health issues effectively because it is holistic and encompasses individuals, social networks, community organisations and institutions, health systems and policy makers.11 12

The conceptual congruence between public health and palliative care approaches facilitated the introduction and adoption of public health palliative care models worldwide and showed promising evidence of effectiveness.11–14 A public health approach protects and improves health and wellness, maximises the quality of life when health cannot be restored and improves the quality, scope and accessibility of age-appropriate care and services.13 14 With neuromuscular conditions, the focus of care is often biomedical (eg, slowing muscular weakness and prolonging life span) at the expense of a holistic approach that includes psychosocial health and living a rich and fulfilling life.10 A public health approach to palliative care has the potential to improve the quality of life and well-being for those with shortened life spans through person-centred strategies.10 11

This paper demonstrates the steps taken to develop a strategic plan for a public health approach to care for YAs with LLNMC using group concept mapping (GCM). The purpose of this study was to engage these YAs, their parents, and health and community providers in British Columbia, Canada, to identify priorities and actions to develop a public health approach to palliative care. This study focuses on YAs with LLNMC (18–35 years of age) who require 24 hours care attendants, fatigue easily and whose independent function may be limited to a few fingers or a hand to control their power wheelchairs and computers.

Methods

Design

GCM is a mixed methods approach in which qualitative strategies (eg, idea generating, sorting and descriptive analysis) along with multivariate quantitative methods (eg, multidimensional scaling, cluster analysis) enable researchers to capture, organise, group and rank conceptual data from a variety of individuals and groups.15 16 Through a structured mixed method process and the use of unique software,17 GCM brings diverse groups of stakeholders together to organise their individual ideas into a common framework to represent group perception of an issue.15 16 There are three distinct phases: (1) brainstorming ideas, (2) sorting and rating ideas and (3) analysing and interpreting the concept maps.15 16

An advantage of using GCM methodology is that it offers opportunities for participants to engage in community-based participatory research and decision making throughout all stages of the research process. Further, it supports hard-to-reach participants to overcome geographical barriers and condition-specific limitations and disabilities that preclude gathering together for face-to-face meetings.15 18 19 For a detailed description of the methodological processes of using GCM as a patient engagement strategy for this study, please refer to Cook and Bergeron.18

Recruitment and sampling

A purposeful sample of YAs with LLNMC, parents, and health and community providers was recruited to participate in all three phases of this study. Recruitment of the YAs and parents was sensitively managed to ensure that invitations were not distributed if the YAs’ health and well-being status were not known. For example, recruitment involved collaborating with the counselling programme at the children’s hospice and the neuromuscular nurse clinician from the children’s hospital to ensure the health and well-being of every YA before inviting them and their parents to participate.18 Email invitations to the potential participants included a letter of information that explained each phase of the study, that participation in each phase was optional, how consent would be obtained for each phase and instructions on how to log on and off the secure project website.18 Study participants determined their participation each time the study moved to a new phase, and informed consent was obtained for all phases of this study. Our recruitment strategy was sensitive to the burden and stress experienced by all participants, particularly the YAs. Therefore, we designed the participation opportunities so that each participant could individualise their level of participation in each phase of the study.18

Data collection

Phase 1: brainstorming ideas

Using the secure project website, participants brainstormed statements online to answer the question: What could be done to improve services and opportunities that will provide a palliative approach to care for YAs with life-limiting conditions? Submitted ideas were anonymous, but could be viewed by all online participants. When data collection for this phase was closed, the researchers reviewed the statements to synthesise similar or duplicate ideas.15 Forty-eight participants brainstormed 84 ideas that were synthesised by the researchers into 64 unique statements.

Phase 2: sorting and rating ideas

These 64 statements were re-entered into the GCM software17 to randomly order them for the online sorting and rating activities. The same pool of participants invited to phase 1 were invited to phase 2 to sort the 64 statements into similar groups and apply a name to each group and/or rate the importance of each of the statements relative to the other statements using a Likert scale with five choices from 1=extremely important to 5=relatively unimportant.18 Participants had the option to complete both tasks or choose one. There was no time limit to complete either task, and the participants could log in or out of the project website as many times as needed.

The next step used the GCM-specific software17 to generate visual maps that depicted relationships between the data to identify ‘clusters’ and the ‘importance’ of ideas to generate concept maps. These maps represented the group conceptualisation of ideas generated from individual responses.15 16

Phase 3: analysing and interpreting the concept maps

A purposeful sample20 of the YAs, their parents, and health and community providers from phases 1 and 2 was invited to participate in a face-to-face workshop based on their unique perspectives and experiences to ensure representation across the groups. While phases 1 and 2 were conducted online, phase 3 was conducted face-to-face to provide opportunities for the YAs to engage with the health and community providers about the YAs’ perspectives and priorities.17 While not all the YAs lived within a reasonable distance of the face-to-face workshop or had access to transportation or support workers to attend with them, it was important for the YAs that could attend to be representative voices.18 Reimbursement of parking and travel expenses were offered to all participants. No other financial reimbursement was offered. The workshop included both large and small group discussions starting with a review of the point, cluster and importance rating cluster maps.15 16 Working in small and large groups, participants actively engaged in analysing and interpreting the generated data and finalising the names and conceptual groupings of the clusters.18

Results

Participants

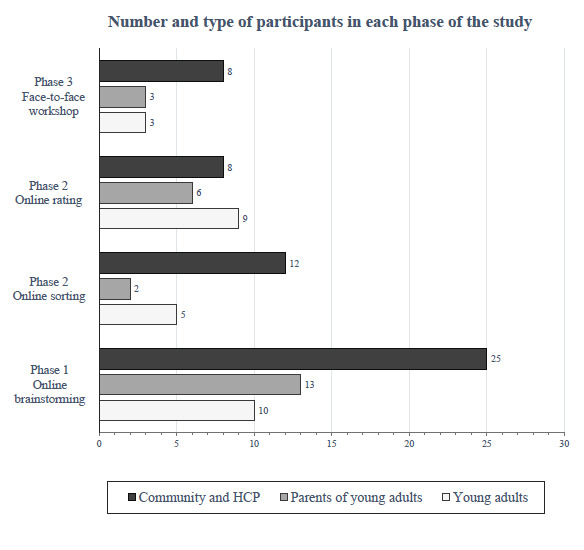

YAs with LLNMC, parents, and community and health providers were represented in all phases of this study. Figure 1 describes the number of participants in each stage of the study. Having 48 participants for brainstorming, 19 participants for sorting and 23 for rating more than doubles the number of participants needed to meet statistical requirements for GCM.15 Of the YA’s who participated, eight have had neuromuscular conditions for more than 20 years and two have had neurological or other conditions for 16–20 years. Related to living conditions, 8 out of 10 YA’s lived at home, 1 lived independently and 1 in an extended care facility. Of the parents that participated, the majority had their YA with LLNMC living at home with them, two did not and one’s child was deceased. Of the community and healthcare professionals, the majority had a paediatric scope of practice, the next largest group had an adult focus and a small number (<8 participants) had a role in both paediatric and adult palliative care systems.

Figure 1.

Number and type of participants by category. HCF, health care provider.

The concept maps

In GCM, several different maps are generated to develop two-dimensional and three-dimensional maps using non-metric multidimensional scaling analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis to identify relationships between ideas generated, create clusters and generate concept maps.15 Non-metric multidimensional scaling creates a plot map of an x-y graph representing the set of statements brainstormed, based on a similarity matrix, and hierarchical cluster analyses depict relationships between statements to generate the cluster and importance rating maps.15

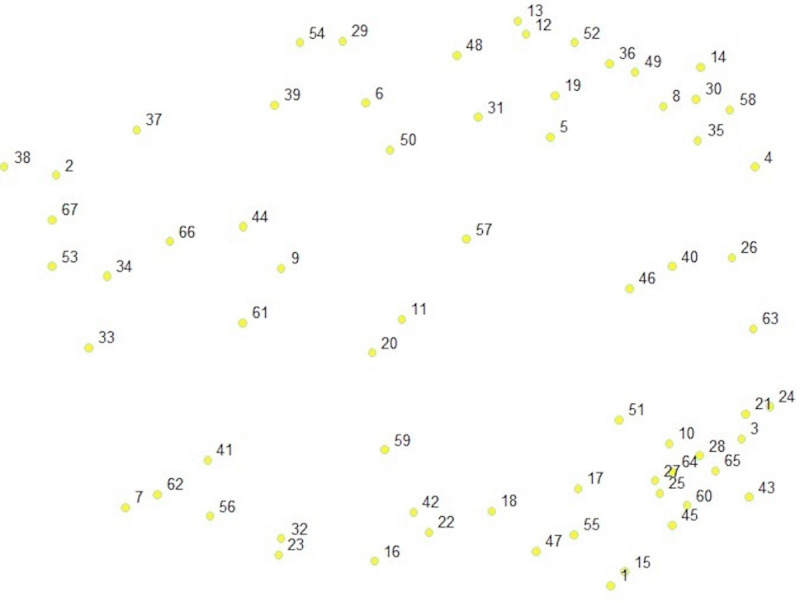

Point map

The point map is the foundation of GCM15 and is generated using the phase 2 data in which participants sort the statements into similar groupings and name each grouping. Our point map shows a visual arrangement of the 64 statements, numbered 1–64, and plotted on an x-y graph (figure 2). The closer the dots are to each other, the more often participants sorted ideas together, and the further away they are from each other, the less often participants sorted them together.15 16 For example, statements 14 (Streamline processes and make it easier to access funding from the Ministry of Social Developmental and Social Innovation) and 41 (Promote greater public awareness of living with a life-limiting condition) were never sorted into the same pile, whereas statements 28 (Ensure continuity of palliative care from paediatric to adult services) and 64 (Create YA palliative care transition management plans and templates) were often sorted together. This point map provides the basis for subsequent cluster analysis.

Figure 2.

A point map demonstrating a visual arrangement of the 64 statements plotted on an x-y graph.

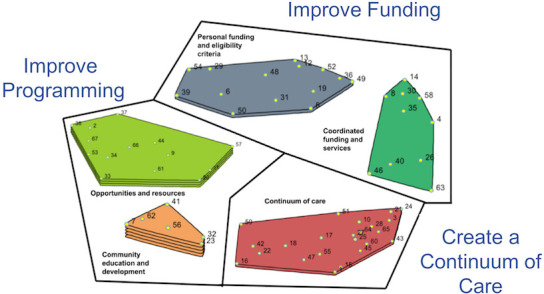

Cluster maps

The next map generated was the cluster map. The purpose of this map is to show how the 64 statements (represented in the point map) could be grouped into two-dimensional clusters. There is no formula for selecting the ‘correct’ number of clusters (how the dots on the point map cluster together), and the number of clusters vary from study to study with a range of between 2 and 20 clusters.15 For our study, we used a feature of the software to examine a range of possible cluster solutions, considered the content of the statements within clusters and calculated the average bridging values (a calculation of whether a statement was sorted with statements that are further away on the map) for each cluster and the average number of categories from the sorting process to determine that a five-cluster solution most accurately represented the ‘best fit’ for the statements within each cluster. Participants in phase 3 reviewed and confirmed this cluster solution and identified the best suited names to describe the five clusters.18 These were: (1) community education and development, (2) opportunities and resources, (3) creating a continuum of care, (4) personal funding and eligibility criteria and (5) coordinated funding and services. A stress value, which reflects how often the ideas were sorted together into a cluster by participants, was calculated. The result was a stress value of 0.2655. This demonstrates that participants sorted the statements in a similar manner and supports the robustness of the five-cluster solution, as this value is lower than the pooled study analysis of 0.28.21

Next, the importance rating cluster map (figure 3) was reviewed with the workshop participants. The importance ratings of each of the 64 statements are represented in the layers within each cluster. The more layers within the cluster, the more important those statements were rated.15 For example, the ‘Community engagement and development’ cluster has the most layers (five), whereas ‘Coordinated funding and services’ has the least layers (one).

Figure 3.

A conceptual map demonstrating the three priorities for a palliative approach to care: (1) improve programming, (2) create a continuum of care and (3) improve funding and the five-cluster solution with importance ranking. The more layers in the cluster, the more important that cluster is when compared with the others.

Conceptual groupings to identify strategic directions

The next step was to identify conceptual groupings among the five clusters. Workshop participants considered the placement of the clusters in relation to each other, the themes and statements within each cluster, and the importance ratings of the statements within each cluster. The result of their consideration was the identification of three conceptual groups: (1) improve programming, (2) improve funding and (3) create a continuum of care (figure 3).

The next step determined the highest average importance rating for each conceptual grouping. For example, improve programming had the highest average importance rating (2.60) followed by create a continuum of care (2.21) and improve funding (2.20). Thus, the statements within the improve programming grouping were judged by participants as most important and contained the highest rated single action among all the statements, which was create an adult make a wish programme. This ranking process confirmed the 30 most important actions to improve services and opportunities for providing a public health approach to palliative care for YAs with LLNMC. The most highly rated statements to improve services and opportunities within each cluster are listed in table 1. The results from calculating the ‘go zone’ (statements that were rated as important to YAs compared with other participants) resulted in 13 statements that were judged by YAs to be most important. These are represented in table 1 with the star symbol.

Table 1.

The most highly rated statements to improve service and opportunities for YAs with neuromuscular life-limiting conditions organised by conceptual grouping and clusters within the groupings

| Cluster | Statement | Average importance rating |

| Improve programming (overall importance rating=2.60) | ||

| Community education and development | 2.72 | |

| Be mindful of needs of other residents living in institutional facilities when providing a palliative approach to care. (32)* | 3.57 | |

| Promote greater public awareness of living with a life-limiting conditions. (41) | 3.09 | |

| Opportunities and resources | 2.49 | |

| Create an adult make a wish programme. (2)* | 3.61 | |

| Create more opportunities for young adults to connect socially in the community (38) | 2.70 | |

| Develop a template for hiring private care aides. (61) | 2.65 | |

| Offer web-based opportunities for young adults to connect on-line, share resources, tips and experience. (53) | 2.64 | |

| Provide better information for finding adaptive technologies. (66) | 2.52 | |

| Create a continuum of care (overall importance rating=2.21) | ||

| Create a continuum of care | 2.21 | |

| Remove the word 'palliative' replace with 'life-limiting' to make it more accessible. (42)* | 3.22 | |

| Ensure contracted home care nursing agencies to send in ONLY qualified palliative care nurses. (59)* | 2.74 | |

| Create young adult palliative care transition management plans and templates. (64)* | 2.57 | |

| Establish a Young Adult Palliative Care System to ensure access to appropriate palliative care that is distinct from paediatric or adult programmes. (17) | 2.57 | |

| Develop a holistic framework for assessing their needs and wants. (16) | 2.41 | |

| Provide opportunities for discussion about future healthcare plans and needs among caregivers, young adults and family members. (18) | 2.30 | |

| Engage family physicians. (55)* | 2.30 | |

| Offer access to a palliative care consult team at any point. (60) | 2.26 | |

| Develop collaborations among community supports, palliative approach to care and specialised teams. (10) | 2.22 | |

| Provide a physiatrist (rehabilitation physicians). (1) | 2.22 | |

| Share patient history and doctor reports with adult hospitals. (65)* | 2.22 | |

| Improve funding (overall importance rating=2.20) | ||

| Personal funding and eligibility criteria | 2.33 | |

| Create a Disabled Status Card to prove needs when applying for equipment and services. (50)* | 2.74 | |

| Provide support for young adults with children to manage all aspects of child care. (57) | 2.70 | |

| Support transportation needs for recreation and leisure activities.(29) | 2.65 | |

| Offer group homes in more cities. (6)* | 2.57 | |

| Ensure better management of equipment so it can be reused or recycled. (39)* | 2.48 | |

| Incorporate shared ride service for those with disabilities. (5) | 2.43 | |

| Develop resources to help with applications for independent living programmes. (19) | 2.35 | |

| Coordinated funding and services | 2.07 | |

| Develop a coordinated approach by all ministries and agencies involved in Community Living B.C. (63)* | 2.52 | |

| Develop a broader definition of palliative approach to care that includes dedicated funding. (26)* | 2.39 | |

| Provide advocates to help those with palliative conditions access programmes/funding. (46)* | 2.39 | |

| Revise the conditions of Registered Disability Savings Plan to ensure timely availability. (30) | 2.30 | |

| Allow income exemptions for person with disabilities to receive Student Aid BC, loans and grants. (58) | 2.13 | |

The number in brackets represents the original statement number on the cluster map.

*Statements most important for YAs (compared with parents and health and community providers).

YA, young adult.

Discussion

Our findings are an important first step to identify priorities and actions to develop a public health approach to palliative care for YAs with LLNMC. For example, the 13 statements starred in table 1 represent the most highly rated statements to improve services and opportunities for these YAs. These 13 statements represent calls to action that can guide system changes to improve services and opportunities to support these YAs.

Our process to determine the calls to action aligns with the principles of a public health approach to palliative care11 in which those in need of care work in partnership with health and community providers to meet the most important needs.22 For example, a public health approach would align with creating a continuum of care, improving personal funding and eligibility criteria and coordinating funding and resources. These recommendations address that these YAs experience diminished access to needed health and community services and acknowledge the uniqueness of their care needs and developmental stage across multiple sectors including healthcare, education, the community and home.8 The call for more education of health and community providers reflects current system insufficiencies such as uniformed conjectures about the value of shorter lives7 and that supports for living have not matched advances in healthcare7 resulting in barriers to post-secondary education and independent living.3–5 Finally, and perhaps most importantly, these calls to action are practical ways to enable these YAs to find meaningful ways to live and participate in their communities.10

Together for short lives, a national patient and family advocacy group for YAs with life-limiting conditions demonstrates the success of a national community engagement project in the UK that resulted in a national strategy for coordinated health, community and psychosocial support.23 A national strategy is especially important in Canada where access to services and supports varies widely depending on location. The creation of a national advocacy agency could be the catalyst to ignite a discussion on how to fill identified gaps to improve programming and funding and create a continuum of care to comprehensively support the health and well-being of YAs with LLNMC.

Policy makers and service providers in other jurisdictions can use GCM as a tool to confirm and differentiate their findings from those of this study. Repeating a similar study across Canada will provide significantly more data and substantiate the need to strengthen services for all YAs with complex and life-limiting conditions. For example, momentum is gaining in Canada to ensure that paediatric services that include support for health, education, psychosocial, family and community support are developmentally incorporated into adult services.2 8 Engaging in this type of a national study would provide much needed information on how the Framework on Palliative Care in Canada24 could be used to develop a pathway to support a public health approach to palliative care for YAs with life-limiting conditions.

Lastly, our results provide support to three of the six short-term goals outlined in the Framework on Palliative Care in Canada.24 This framework provides a blueprint to help shape palliative care across Canada and identifies long-term (5–10 years), medium-term (2–5 years) and short-term goals.24 Of the six short-term goals identified, our study results contribute to three by identifying: (1) the range of wishes and needs of people with life-limiting conditions, specifically YAs with LLNMC; (2) the training and educational needs for healthcare providers and caregivers (eg, what a continuum of care system should include to better service these YAs) and (3) existing research and data collection gaps (eg, more research on YAs’ needs for a palliative approach to care needed). In addition, the Framework on Palliative Care highlights that YAs are an underserviced population in Canada.24 Our results may offer recommendations for YAs with other life-limiting conditions and underserved populations.

Study strengths and limitations

The key strength of this study is the patient engagement and participatory action approach used to gather, analyse and interpret data. GCM is uniquely suited as a participatory action approach to engage a community of study participants (such as YAs with LLNMC, parents, and health and community providers) as research collaborators.19 Putting those who have lived experiences alongside researchers, health providers and decision-makers are necessary to build a sustainable, accessible and equitable healthcare system and bring positive changes to the well-being of YAs with life-limiting conditions.25 The YAs in this study were engaged as knowledge brokers and experts in the personal and systemic barriers they experience.5 9

Concept mapping is also distinctively appropriate for engaging YAs with life-limiting conditions, specifically progressive neuromuscular conditions, their parents and community providers in research. The online method for data collection accommodates their varying energy levels and allows flexibility to participate in each phase of the study. The use of GCM software17 supports these unique needs.

While the number of YAs who participated may not represent the views of all YAs with life-limiting conditions, this is one of the first opportunities for any YAs with LLNMC to have their voices heard and even more so in a face-to-face workshop with healthcare provider stakeholders. Our rigorous recruitment strategy ensured that as many reachable YAs and their parents as possible were included in this study.18

Another limitation that evolved over the course of this research was using ‘palliative’ in our correspondence and brainstorming question. While many of the YA participants attended a children’s hospice practising a palliative approach to care, they do not see themselves as ‘palliative’ in the traditional understanding of the word describing the last months and weeks of life. While declining health and independence may limit their options, these YAs share the aspirations and goals of all YAs.9

One constraint of GCM pertinent to this study is the limitation of a single focus question, which may have limited participants’ ability to share other ideas to support their well-being and achieve their goals. Another constraint is the inability of GCM to describe or explore the relationship among the calls to action. Despite these limitations, the use of a mixed methods research design and a patient engagement participatory action research approach are strengths of this study.20

Future research

This study demonstrates the need for necessary changes to current services for YAs with LLNMC. While researchers are now focusing on understanding how paediatric services that include health, education, psychosocial, family and community support can be developmentally incorporated into to adult services,9 more data are needed to better position policy makers and service providers to meet the needs of these YAs and their communities of support.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates the unique perspectives and experiences of YAs living with LLNMC. Further, it was the first opportunity for the YAs to make recommendations for changes within health and community systems to match their unique developmental needs. This study also facilitated knowledge exchange and collaboration among these YAs, parents and caregivers, health and community professionals, and volunteers. Results included identifying three strategic directions (improve programming, improve funding and create a continuum of care) and five specific calls to action: (1) invest in community education and development, (2) provide opportunities and resources, (3) ensure coordinated funding and resources, (4) improve personal funding and eligibility criteria and (5) create a continuum of care. Further, there are 13 specific actions that these YAs recommended to improve services and opportunities. Our findings align with and could contribute to the best practices outlined in the Framework on Palliative Care in Canada.23 Moreover, our findings and study methods may have application beyond Canada to other jurisdictions.

Acknowledgments

Heartfelt thanks to the young adults and their parents who partnered with us and contributed their time and considerable effort. Thanks to Ms Cindy Baleywich from BC Children’s Hospital and Ms Susan Poitras from Canuck Place for their support with participant recruitment. Thanks to Joanie Maynard for support with technical writing, image development and manuscript review.

Footnotes

Twitter: @L3YoungAdults

Contributors: Both authors, KAC and KB were involved in planning, conducting the research and reporting of the work described in this article. While our expertise varied among all the components of conducting the research and writing up for publication, we share the responsibility of the overall content as guarantors.

Funding: Funding for this research was provided by the Canadian Institute of Health Research Strategy for Patient Engagement Research and the Athabasca University Research Centre.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval to recruit participants for this study was obtained from Athabasca University (21795) and the Fraser Health Ethics Research Board (2015-073).

References

- 1. Bushby K, Finkel R, Birnkrant DJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:77–93. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70271-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cohen E, Patel H. Responding to the rising number of children living with complex chronic conditions. CMAJ 2014;186:1199–200. 10.1503/cmaj.141036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Joly E. Transition to adulthood for young people with medical complexity: an integrative literature review. J Pediatr Nurs 2015;30:e91–103. 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kerr H, Price J, Nicholl H, et al. Transition from children's to adult services for young adults with life-limiting conditions: a realist review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;76:1–27. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cook K, Siden H, Jack S, et al. Up against the system: a case study of young adult perspectives transitioning from pediatric palliative care. Nurs Res Pract 2013;2013:1–10. 10.1155/2013/286751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hamdani Y, Mistry B, Gibson BE. Transitioning to adulthood with a progressive condition: best practice assumptions and individual experiences of young men with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37:1144–115. 10.3109/09638288.2014.956187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abbott D, Carpenter J. ‘Wasting precious time’: young men with Duchenne muscular dystrophy negotiate the transition to adulthood. Disabil Soc 2014;29:1192–205. 10.1080/09687599.2014.916607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canadian Association of Paediatric Health Centres, Complex Care Community of Practice . CAPHC guideline for the management of medically complex children and youth through the continuum of care. Ottawa: Children’s Healthcare Canada, 2018. https://macpeds.mcmaster.ca/documents/CAPHC%20National%20Complex%20Care%20Guideline%202018_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cook KA, Jack SM, Siden H, et al. Investing in uncertainty: young adults with life-limiting conditions achieving their developmental goals. J Palliat Med 2016;19:830–5. 10.1089/jpm.2015.0241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Setchell J, Thille P, Abrams T, et al. Enhancing human aspects of care with young people with muscular dystrophy: results from a participatory qualitative study with clinicians. Child Care Health Dev 2018;44:269–77. 10.1111/cch.12526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Public Health Palliative Care International . The public health approach to palliative care, 2016. Available: http://www.phpci.info/public-health-approach/ [Accessed 23 Aug 2019].

- 12. Hassan E. Palliative care is a public health issue. Vancouver: BC Centre for Palliative Care, 2015. https://www.bc-cpc.ca/cpc/palliative-care-is-a-public-health-issue/ [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abel J, Kellehear A, Karapliagou A. Palliative care-the new essentials. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:S3–14. 10.21037/apm.2018.03.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simone CB. Public health approaches to palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:E1. 10.21037/apm.2018.05.03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kane M, Rosas S. Conversations about group concept mapping: applications, examples, and enhancements. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kane M, Trochim W. Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Concept Systems Incorporated. . Concept systems global MAX™, 2017. Available: www.conceptsystems.com/home [Accessed 29 Sept 2019].

- 18. Cook K, Bergeron K. Using group concept mapping to engage a hard to reach population in research: young adults with life limiting conditions. Int J Qual Methods 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vaughn LM, Jones JR, Booth E, et al. Concept mapping methodology and community-engaged research: a perfect pairing. Eval Program Plann 2017;60:229–37. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosas SR, Kane M. Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Eval Program Plann 2012;35:236–45. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abel J, Kellehear A. Palliative care reimagined: a needed shift. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:21–6. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Together for Short Lives . Resources and best practice on transition. Available: https://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/changing-lives/developing-services/transition-adult-services/research-best-practice/ [Accessed 30 Nov 2018].

- 24. Health Canada . Framework on palliative care in Canada. Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/palliative-care/framework-palliative-care-canada.html [Google Scholar]

- 25. Government of Canada . Strategy for patient-oriented research: putting patients first. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2014. http://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.697556/publication.html [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.