Abstract

Objectives

To compare the proportion of patients with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury reporting an acceptable symptom state, between non-surgical and surgical treatment during a 10-year follow-up.

Methods

Data were extracted from the Swedish National Knee Ligament Registry. Exceeding the Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS) for the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) was the primary outcome. The PASS and KOOS4 (aggregated KOOS without the activities of daily living (ADL) subscale) were compared cross-sectionally at baseline and 1, 2, 5 and 10 years after ACL injury, where patients treated non-surgically were matched with the maximum number of patients with ACL reconstruction for age, sex and activity at injury.

Results

The non-surgical group consisted of 982 patients, who were each matched against 9 patients treated with ACL reconstruction (n=8,838). A greater proportion of patients treated with ACL reconstruction exceeded the PASS in KOOS pain, ADL, sports and recreation, and quality of life compared with patients treated non-surgically at all follow-ups. With respect to quality of life, significantly more patients undergoing ACL reconstruction achieved a PASS compared with patients receiving non-surgical treatment at all follow-ups except at baseline, with differences ranging between 11% and 25%; 1 year −25.4 (−29.1; −21.7), 2 years −16.9 (−21.2; −12.5), 5 years −11.0 (−16.9; −5.1) and 10 years −24.8 (−36.0; −13.6). The ACL-reconstructed group also reported statistically greater KOOS4 at all follow-ups.

Conclusion

A greater proportion of patients treated with ACL reconstruction report acceptable knee function, including higher quality of life than patients treated non-surgically at cross-sectional follow-ups up to 10 years after the treatment of an ACL injury.

Keywords: Anterior Cruciate Ligament, Knee

Introduction

Both non-surgical treatment, that is, rehabilitation alone, and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction after ACL injury are widely accepted treatments, with the potential to restore satisfactory knee joint function, at least in the short term.1–7 However, the current knowledge of prognostics and outcome after non-surgical treatment is limited and these factors have been sparsely investigated. For instance, there is only one registry study from the Swedish National Knee Ligament Registry (SNKLR) that has compared patients treated non-surgically with patients with ACL reconstruction, and favourable outcomes have been reported for patients who underwent ACL reconstruction in terms of knee function and knee-related symptoms, 1–5 years after ACL injury or reconstruction.8 Contrary to these findings, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) by Frobell et al 3 9 did not demonstrate differences in patient-reported outcomes (PROs) between the two treatments at 2-year and 5-year follow-ups.3 9

To improve quality of life (QoL) and minimise knee-related restrictions for patients who have sustained an ACL injury, it is imperative to understand the factors that affect short-term and long-term outcomes and the way the outcome is influenced by the type of treatment. However, the results for the region-specific outcomes, such as the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)10 11 reflecting patient-reported knee function, are sometimes difficult to interpret in daily practice and carry the risk of potential wash-out, as the outcomes may contain several items. Another reason is that a clinically relevant change in PRO may not correlate with the individual patient’s satisfactory state of feeling well. The Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS)12 has gained increasing attention in clinical research and provides a threshold value for PROs at which patients regard their knee function as acceptable.12–14 The use of PASS cut-offs provides a reference value beyond which patients regard themselves as feeling well and offers new opportunities to understand and interpret the results when treatment options after ACL injuries are compared. Recently, the responder criteria, PASS, has been used to interpret the KOOS in patients in the RCT by Frobell et al,3 resulting in no difference in the proportion of patients exceeding the cut-off for feeling well, PASS in KOOS, 2 years after surgical or non-surgical treatments after an ACL injury.15

To establish evidence for the way patients with ACL injury undergoing non-surgical treatment and ACL reconstruction compare with one another, it may be helpful to use pre-determined responder criteria in terms of the PASS to interpret PROs. As a result, we compared the proportion of patients with ACL injury that report acceptable knee function (PASS in KOOS) at baseline and 1, 2, 5 and 10 years following non-surgical treatment and ACL reconstruction, respectively. In addition, we compared the aggregated KOOS4, as a proxy for overall knee function, between treatment groups.

Material and methods

The SNKLR

The SNKLR is a nationwide quality registry with the overall aim of improving the outcome of treatments for patients with ACL injuries in Sweden. The registry was initiated in January 2005 and has a coverage of approximately 90% of all ACL reconstruction surgeries performed in Sweden.16

Data on ACL injuries and associated injuries are prospectively collected through both a surgeon-reported section and a patient-reported section. In the event of ACL reconstruction, the operating surgeon reports information such as the activity at the time of injury, time from injury to ACL reconstruction, graft selection, surgical fixation techniques and concomitant injuries. In the current study, the type of activity at the time of ACL injury was classified as alpine/skiing, pivoting sport (such as soccer, team handball, floorball and basketball), non-pivoting sport (such as running, cycling, equestrian sports and volleyball) and other (such as traffic accidents and accidents at work or during outdoor life). Patients with an ACL injury who choose to undergo non-surgical treatment are informed by their treating physician, physical therapist or nurse that they have the option to register in the SNKLR through their personal security number. To date, the SNKLR does not systematically collect data from patients who undergo non-surgical treatment, although they are invited to register and complete follow-ups similar to patients undergoing an ACL reconstruction. Therefore, the coverage of non-surgically treated patients with ACL injury in the SNKLR is unknown. Age and sex are automatically registered through the patient’s social security number. The patient-reported section is organised in a similar fashion, independently of whether the patient is treated non-surgically or surgically. This section is based on PROs, including the KOOS, reported at baseline/preoperatively and at 1, 2, 5 and 10 years after ACL injury and reconstruction, respectively. Participation in the SNKLR is voluntary for both patients and surgeons, since there is no national legislation making registry participation and data input mandatory. Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans of this study.

Patients

For patients registered with non-surgical treatment, data were accessible from 1 January 2006 to 30 October 2019 in the SNKLR, in terms of all patient-related and follow-up data, respectively, at baseline and at 1, 2, 5 and 10 years after ACL injury. Data for patients treated with ACL reconstruction were accessible from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2018, in terms of all patient-related, surgery-related and follow-up data. We included all patients registered with non-surgical treatment, who had a complete registration of baseline information that consisted of the date of ACL injury, age, sex, activity at ACL injury and had any KOOS follow-up data registered. The non-surgically treated patients were matched with as many patients as possible who had undergone ACL reconstruction in terms of age ±3 years, sex and the type of activity at the time of injury. Follow-up data were not part of the matching procedure. This resulted in each non-surgically treated patient being matched to nine patients, who had undergone primary ACL reconstruction. All patients registered with a unilateral ACL reconstruction were eligible for inclusion and matching. The exclusion criteria were patients registered with an ACL revision or a contralateral knee injury and patients who had sustained a medial collateral ligament or lateral collateral ligament injury that required surgical treatment or associated injuries, including fracture, tendon injury, nerve damage or vascular damage. We also excluded patients who crossed over from non-surgical treatment to ACL reconstruction. Patients aged <15 years were also excluded.

Outcome measures

The primary endpoint of this study was exceeding the PASS in the KOOS subscales at each cross-sectional follow-up from baseline to 10 years after ACL injury or reconstruction. To exceed the PASS cut-offs in the study is hereinafter named reporting or achieving a PASS. The timing of the follow-up was based on the patient’s completion of PROs in the SNKLR after ACL injury for patients treated non-surgically and after surgery for patients treated with an ACL reconstruction. Baseline KOOS was reported on the day of the ACL reconstruction for the patients who underwent surgery, while patients who were treated non-surgically on average responded to KOOS 87.3 (54.4) days after the ACL injury.

The KOOS is a five-dimension questionnaire, validated for patients with knee injuries and knee osteoarthritis.10 11 The KOOS dimensions are five in number and consist of pain, knee-related symptoms, activities of daily living (ADL), function in sport and recreation and knee-related QoL. The KOOS consists of a total of 42 items with five response options each that are scored from 0 (no problem) to 4 (extreme problem). Scores from each domain are then transformed to a scale ranging from 0 (worst) to 100 (best).

Whereas the minimal important change indicates whether or not the patient is feeling better, the PASS, on the other hand, indicates whether the patient is actually feeling well. The PASS for the KOOS is estimated through threshold values for each subscale. These values were obtained by asking patients with an ACL injury the following question: ‘Taking account of all the activity you have during your daily life, your level of pain and also your activity limitations and participation restrictions, do you consider the current state of your knee satisfactory?’, with the answers yes or no.12 The PASS thresholds (sensitivity, specificity) for the KOOS subscales (table 1) were determined by Muller et al 12 and have previously been used.

Table 1.

PASS thresholds for the KOOS subscales defined by Muller et al 12

| KOOS symptoms | KOOS pain | KOOS ADL | KOOS Sport&Rec | KOOS QoL |

| 57 (0.78, 0.67) | 89 (0.82, 0.81) | 100 (0.70, 0.89) | 75 (0.87, 0.88) | 62.5 (0.82, 0.85) |

The PASS for each KOOS item is presented as the threshold value with the sensitivity and specificity (listed in parentheses), unless otherwise stated.

ADL, activities of daily living; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; QoL, quality of life; Sport&Rec, function in sport and recreation.

In addition, the KOOS4 was used to determine the overall knee function in patients after ACL injury treatment. In a relatively young and active population undergoing ACL reconstruction, the KOOS subscale of ADL is limited by ceiling effects, as patients’ scores cluster towards the best possible score of the subscale. To avoid this, the KOOS4 was developed from the KOOS and is an average score (ranging from 0 to 100) constructed from four of the five KOOS subscales: KOOS pain, KOOS symptoms, KOOS sport and recreation and KOOS QoL.3

Statistical methods

The statistical analyses were performed using SAS/STAT (V.14.2, 2016; SAS Institute). For categorical variables, frequencies (n) and proportions (%) were presented and, for continuous variables, the mean and SD, the median and minimum-maximum, 95% CIs and frequencies (n) were presented. For the comparison between non-surgical treatment and ACL reconstruction groups, Fisher’s exact test (lowest one-sided p value divided by 2) was used for dichotomous variables, the χ2 test was used for non-ordered categorical variables and Fisher’s non-parametric permutation test was used for continuous variables. The 95% CI for the mean difference regarding continuous variables between the groups was based on Fisher’s non-parametric permutation test. Comparisons were made for the PASS in each KOOS domain and KOOS4 between the two treatment groups at each time point (1, 2, 5 and 10 years) with greedy matching (non-surgical: ACL reconstruction) for age, sex and activity at injury, using a nearest neighbour approach.17 All the tests were two sided and performed at the 5% significance level.

Results

A total of 982 patients treated non-surgically (57% men) were included. The mean age at injury was 30.2 (SD 10.6) years and approximately half of the ACL injuries (54.8%) were sustained during pivoting sports. Each non-surgically treated patient was matched against 9 patients who had undergone ACL reconstruction (n=8,838) (table 2). The number of non-surgically treated patients with available PRO data was 489 at baseline, 740 at the 1-year, 614 at the 2-year, 329 at the 5-year and 97 at the 10-year follow-up.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of all patient in the non-reconstructed and ACL-reconstructed groups with data at any follow-up

| Characteristic | Non-reconstructed (n=982) | ACL-reconstructed (n=8,838) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 30.2 (10.6) | 30.0 (10.5) |

| Sex (n, %) | ||

| Male | 555 (56.5) | 4,995 (56.5) |

| Female | 427 (43.5) | 3,843 (43.5) |

| Activity at injury (n, %) | ||

| Alpine/skiing | 224 (22.8) | 2,016 (22.8) |

| Pivoting sport | 538 (54.8) | 4,842 (54.8) |

| Non-pivoting sport | 44 (4.5) | 396 (4.5) |

| Other | 176 (17.9) | 1,584 (17.9) |

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

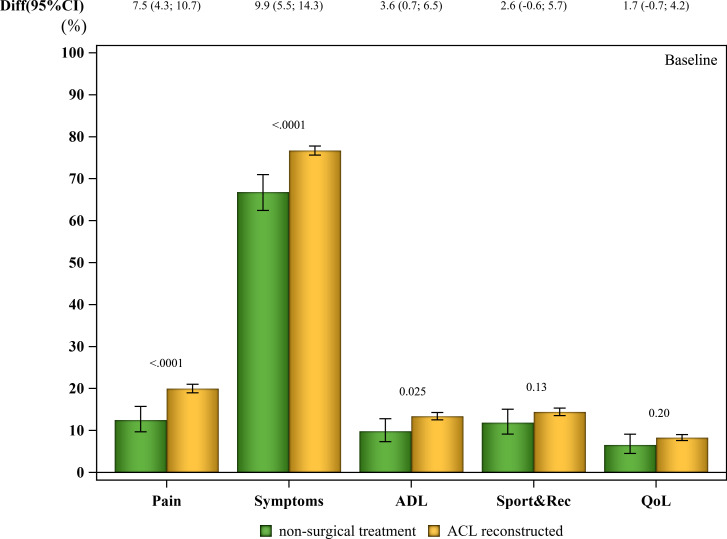

At baseline, a larger proportion of patients in the ACL reconstruction group reported a PASS for KOOS pain (mean difference 7.5% (95% CI 4.3% to 10.7%), p=0.0001), symptoms (mean difference 9.9% (95% CI 5.5% to 14.3%), p<0.0001) and ADL (mean difference 3.6% (95% CI 0.7% to 6.5%), p=0.025) compared with patients treated non-surgically (table 3). There were no differences in the PASS for the KOOS sport and recreation (95% CI 2.6 (−0.6 to 5.7), p=0.13) and QoL subscales (95% CI 1.7 (−0.7 to 4.2), p=0.20, figure 1).

Table 3.

Mean differences in the proportion of achieved PASS between patients treated non-surgically and ACL-reconstructed patients.

| Pain | Symptoms | ADL | Sport&Rec | QoL | |

| Baseline | −7.5 (−10.7 to −4.3)* | −9.9 (−14.3 to −5.5)* | −3.6 (−6.5 to −0.7)* | −2.6 (−5.7 to 0.6) | −1.7 (−4.2 to 0.7) |

| 1 year | −13.0 (−16.8 to −9.2)* | −2.3 (−5.1 to 0.5) | −10.0 (−13.4 to −6.6)* | −13.2 (−17.0 to −9.4)* | −25.4 (−29.1 to −21.7)* |

| 2 years | −10.0 (−14.3 to −5.6)* | −1.7 (−4.6 to 1.2) | −5.3 (−9.4 to −1.2)* | −9.7 (−14.0 to −5.4)* | −16.9 (−21.2 to −12.5)* |

| 5 years | −6.5 (−12.5 to −0.5)* | −1.8 (−5.5 to 1.9) | −7.9 (−13.6 to −2.1)* | −9.3 (−15.3 to −3.4)* | −11.0 (−16.9 to −5.1)* |

| 10 years | −19.0 (−30.2 to −7.8)* | −4.7 (−12.7 to 3.4) | −11.5 (−22.4 to −0.7)* | −18.2 (−29.3 to −7.1)* | −24.8 (−36.0 to −13.6)* |

Data are presented as the mean with 95% CIs between groups, unless otherwise stated. Mean differences are reported as patients treated non-surgically compared with patients treated with ACL reconstruction. Therefore, negative mean differences indicate superior outcomes for patients treated with ACL reconstruction.

*P<0.05.

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ADL, activities of daily living; PASS, Patient Acceptable Symptom State; QoL, quality of life; Sport&Rec, function in sport and recreation.

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients with acceptable knee function on the different subscales (PASS on KOOS) at baseline; 489 non-reconstructed patients and 5,976 ACL-reconstructed patients. p<0.05 is statistically significant. The error bars represent the exact 95% CI for the proportion of patients reporting a KOOS above the PASS cut-off. Pairwise comparison between groups were determined based on the Fisher’s exact test (two sided). ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ADL, activities of daily living; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; PASS, patient acceptable symptom state; QoL, quality of life; Sport & Rec, function in sport and recreation.

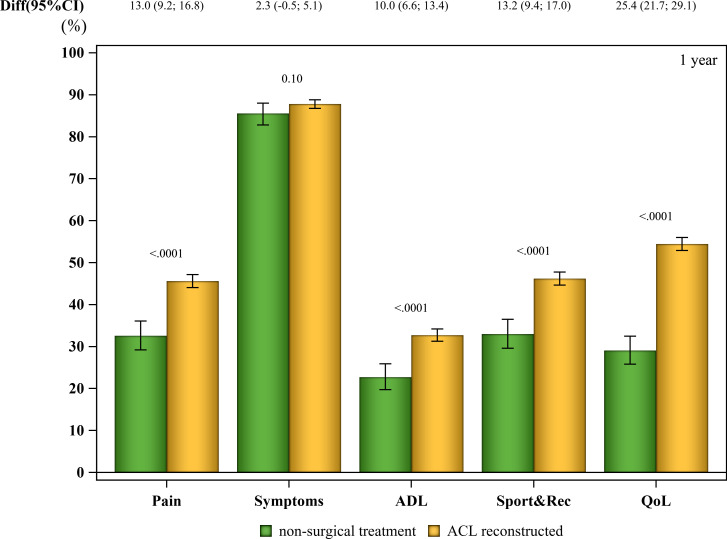

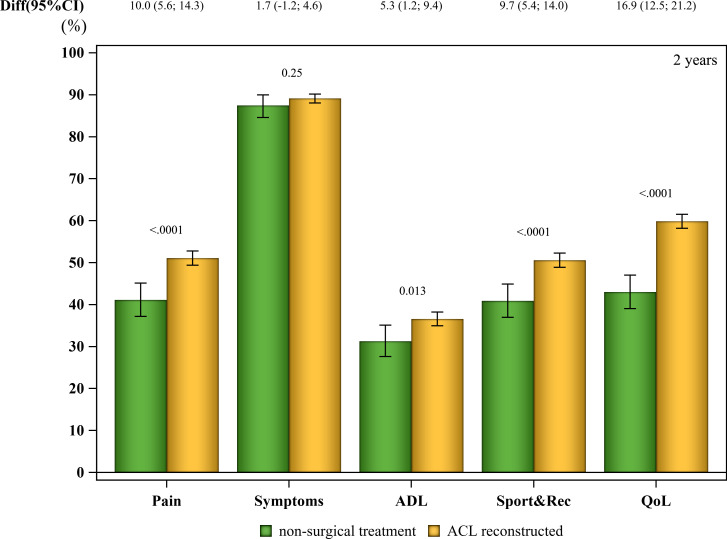

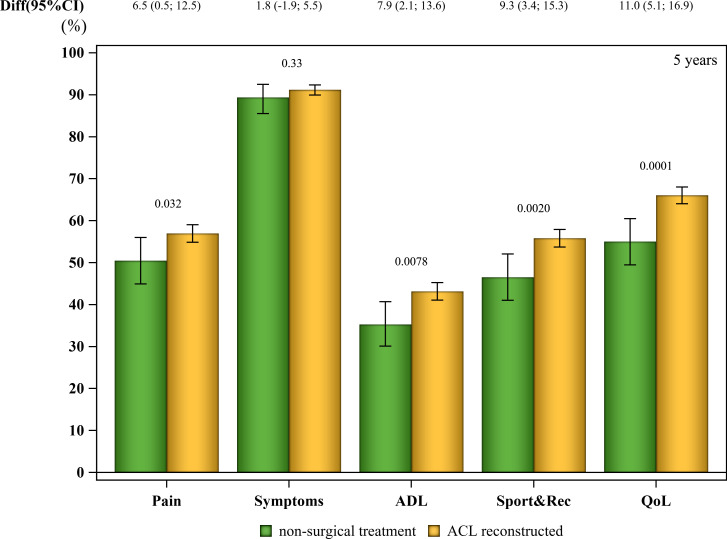

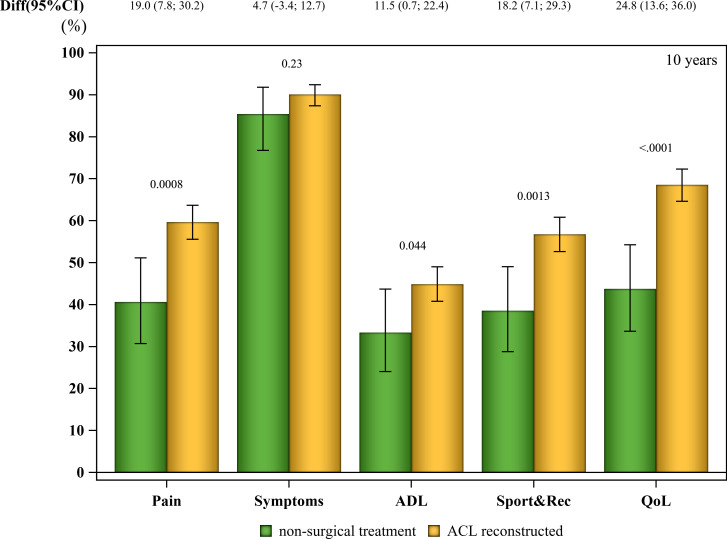

At the 1-year, 2-year, 5-year and 10-year follow-ups, there were no differences between the groups at any time point in the proportion of patients achieving a PASS on the KOOS symptom subscale. However, on all the other subscales, the ACL reconstructed group consistently had a greater proportion of patients reporting a PASS on all follow-up occasions (figures 2–5). The differences ranged from 5.3% (95% CI −5.3 (−9.4% to −1.2%) p=0.013) on the ADL subscale at 2 years of follow-up to the greatest differences on the QoL-subscale at the 1-year and 10-year follow ups, 25.4% (mean −25.4 (95% CI −29.1 to −21.7) p<0.0001) and 24.7% (mean −24.7 (95% CI −36.0 to −13.6) p<0.0001), respectively (table 3).

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients achieving acceptable knee function on the different subscales (PASS on KOOS) at 1 year after an ACL injury; 740 non-reconstructed patients and 4,018 ACL-reconstructed patients. A p<0.05 is statistically significant. The error bars represent the exact 95% CI for the proportion of patients reporting a KOOS above the PASS cut-off. Pairwise comparison between groups were determined based on the Fisher’s exact test (two sided). ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ADL, activities of daily living; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; PASS, patient acceptable symptom state; QoL, quality of life; Sport & Rec, function in sport and recreation.

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients achieving acceptable knee function on the different subscales (PASS on KOOS) at 2 years after an ACL injury; 614 non-reconstructed patients and 3,396 ACL-reconstructed patients. A p<0.05 is statistically significant. The error bars represent the exact 95% CI for the proportion of patients reporting a KOOS above the PASS cut-off. Pairwise comparison between groups were determined based on the Fisher’s exact test (two sided). ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ADL, activities of daily living; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; PASS, patient acceptable symptom state; QoL, quality of life; Sport & Rec, function in sport and recreation.

Figure 4.

Proportion of patients achieving acceptable knee function on the different subscales (PASS on KOOS) at 5 years after an ACL injury; 329 non-reconstructed patients and 2,202 ACL-reconstructed patients. A p<0.05 is statistically significant. The error bars represent the exact 95% CI for the proportion of patients reporting a KOOS above the PASS cut-off. Pairwise comparison between groups were determined based on the Fisher’s Exact test (2-sided). ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ADL, activities of daily living; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; PASS, patient acceptable symptom state; QoL, quality of life; Sport & Rec, function in sport and recreation.

Figure 5.

Proportion of patients achieving acceptable knee function on the different subscales (PASS on KOOS) at 10 years after an ACL injury; 97 non-reconstructed patients and 584 ACL-reconstructed patients. A p<0.05 is statistically significant. The error bars represent the exact 95% CI for the proportion of patients reporting a KOOS above the PASS cut-off. Pairwise comparison between groups were determined based on the Fisher’s exact test (two sided). ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ADL, activities of daily living; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; PASS, patient acceptable symptom state; QoL, quality of life; Sport & Rec, function in sport and recreation.

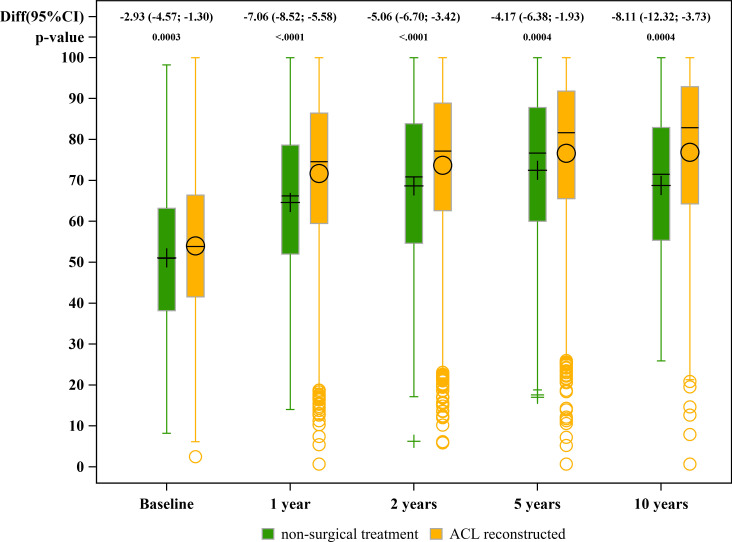

Patients treated with ACL reconstruction reported a significantly greater KOOS4 at all follow-ups compared with patients treated non-surgically, with the greatest difference at the 10-year follow-up (mean −8.11 (95% CI −12.32 to −3.81), p=0.0006, figure 6).

Figure 6.

KOOS4 score from baseline and 1-year, 2-year, 5-year and 10 year follow-ups for non-reconstructed patients and ACL-reconstructed patients. A p<0.05 is statistically significant. The coloured boxes and bars express the median and 1st and 3rd quartile. The crosses and circles (in the yellow and green boxes, respectively) express the mean KOOS4 for the treatment groups. The crosses and circles below the box plots illustrate outliers. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ADL, activities of daily living; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; QoL, quality of life; Sport & Rec, function in sport and recreation.

All average PASS in KOOS and KOOS4 outcomes are presented in online supplemental appendix tables 1 and 2.

bjsports-2021-105115supp001.pdf (40.4KB, pdf)

bjsports-2021-105115supp002.pdf (18.8KB, pdf)

Discussion

The most important finding in this study was that, starting from baseline to the 10-year follow-up, patients undergoing ACL reconstruction to a greater extent perceived an acceptable symptom state of their knee compared with patients treated non-surgically after an ACL injury. A greater proportion of patients who had undergone ACL reconstruction achieved a PASS on the KOOS compared with patients treated non-surgically, on all subscales except symptoms throughout the 1–10 year follow-ups. Moreover, there was a consistently greater proportion of achievement of a PASS in patients treated with ACL reconstruction compared with patients treated non-surgically, with differences ranging from 10% to 25% at 1 year, 5% to 17% at 2 years, 7% to 11% at 5 years and 12% to 25% at 10 years, respectively. An arbitrary, non-evidence-based cut-off for a difference of 10% in PASS has previously been used to interpret the results as clinically meaningful.15 Based on this, our study results suggest that the difference in KOOS QoL between groups may achieve clinical relevance favouring surgery at all follow-ups, while Pain and Sport&Recreation achieved clinical relevance at the 1-year and 10-year follow-ups in particular. On the other hand, the difference in KOOS4, a currently non-validated aggregated KOOS used to determine overall knee function, between groups never exceeded an estimated MIC of 9 points,15 suggesting no clinically relevant differences between treatments. In addition, we acknowledge that many other factors influence treatment decision-making after an ACL injury, such as cost-benefit, adverse events, risk of post-traumatic osteoarthritis and patient-choice. Therefore, while the results should be interpreted within the context of these important decision-making factors, our results suggest that ACL reconstruction may be associated with clinically meaningful and favourable PROs compared with non-surgical treatment. This is supported by the observation that the largest difference at all follow-ups was observed in knee-related QoL, where fewer than half the patients treated non-surgically achieved a PASS until the 10-year follow-up.

Only a limited number of studies are available comparing PROs after non-surgical treatment and ACL reconstruction, where the majority comprise relatively small cohorts, have short-term follow-ups and demonstrate conflicting results.3 8 18 19 In line with the results of the current study, a previous study from the SNKLR reported superior outcomes in knee-related QoL and function in sports for patients undergoing ACL reconstruction compared with patients treated non-surgically at 1 and 2 years of follow-up.8 In addition, the patients treated with ACL reconstruction reported superior knee-related symptoms and knee-related QoL at the 5-year follow-up compared with non-surgically treated patients. However, Ardern et al 8 analysed the KOOS continuously at all follow-ups and most of the differences were not clinically relevant.8 Conversely, previous RCTs comparing treatments after ACL injury found no meaningful difference, in patient-reported knee function between non-surgical treatment and ACL reconstruction (early or delayed) at the 2-year follow-up3 20 and no difference at the 5-year follow-up.9 However, approximately 50% of patients randomised to the non-surgical group opted for delayed ACL reconstruction,3 9 leaving questions of why non-surgical treatment was unsatisfactory for some patients. Additionally, the results of the secondary analysis of the same RCT showed that early ACL reconstruction may reduce the risk of developing medial meniscal damage compared with optional delayed ACL reconstruction (45% vs 53%).21 Grindem et al 19 reported that there are few differences in knee function, sports participation and knee reinjury rate at the 2-year follow-up between surgically and non-surgically treated patients following ACL injury, and is in agreement with the results by Frobell et al.3 9 The divergence in the results of available studies warrants further evaluation of the topic. One possible explanation for the discrepancy between the aforementioned studies and this study, where superior results for ACL reconstruction are reported, could be related to differences in the patient selection for surgical and non-surgical treatment as a result of the study designs, as well as the larger number of patients included in the current study. It should be noted that studies on ACL reconstruction have reported mean improvements in knee function at 1 and 2 years after ACL injury compared with baseline, suggesting that both treatment options are acceptable when it comes to improving knee function and QoL in this population of patients.

The results of the current study also suggest that at least one in three patients with an ACL injury, regardless of treatment, does not achieve acceptable knee function. This indicates that there is a great need for more research on treatments and their outcomes to improve knee function and QoL for patients with an ACL injury, as well as determining which patients will benefit most from the individual treatments. It should be borne in mind that, in the current study, the indications for treatment choice are unknown and it is possible that this may have affected the outcome. There is also a substantial difference in the number of patients undergoing non-surgical treatment compared with surgical treatment for an ACL injury in the SNKLR and the results may be influenced by attrition bias, since many of the non-surgically treated patients in Sweden have not been registered in the registry over the years.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large, prospective long-term registry study comparing non-surgical and surgical ACL treatment cross-sectionally and using a patient-acceptable threshold value to interpret the results from PROs. Nonetheless, the current study is not without limitations. Unfortunately, the results run the risk of confounding by indication, as there was no information in the SNKLR related to the indications to why the patients received the different treatments, or whether the patients treated without ACL reconstruction had concomitant injuries or underwent treatment for them. This limitation may be partly reflected by the baseline differences, where patients treated with ACL reconstruction reported superior knee function and a greater proportion reported acceptable pain, symptoms and function in ADL, compared with patients treated non-surgically. To increase the total number of patients, we used cross-sectional cohorts at all follow-ups and a greedy matching, where every patient treated non-surgically was matched with nine patients who had undergone ACL reconstruction in terms of age, sex and type of activity at ACL injury. This limits our opportunities to draw conclusions with regards to the effect of the individual treatments. As the matching procedure did not include KOOS follow-ups, there is a risk for potential selection bias, where patient demographics between groups were different at follow-ups. There was only a small proportion of patients who had available outcomes at the 10-year follow-up, which is why results from this follow-up should be considered with caution. One strength of this study was the use of the PASS threshold, which facilitates the interpretation of the proportion of patients that perceived their knee function as acceptable, which most likely is clinically relevant. Patients choosing non-surgical treatment are likely to have less demanding goals for their activity level and may be satisfied with the current state of their knee. However, there is no known PASS threshold for non-surgical treatment, therefore, applying the Muller et al’s12 thresholds to this group may have resulted in under- or over-estimating the proportion of non-surgically treated patients who were satisfied with their knee function. In addition, it is important to note that the PASS threshold is a cut-off determined on patients 1–6 years after ACL reconstruction. Subsequently, it is possible that what patients perceive as acceptable knee function in close proximity after the ACL injury and in the long term differ, that is, baseline/presurgical follow-up, 10-year follow-up and especially for the non-surgically treated patients.12 It is also important to note that receiver operating characteristics thresholds are only accurate when 50% achieve the outcome of interest.22 In the reference study by Muller et al,12 almost 90% of individuals achieved PASS, which introduces bias into these calculations. Preferably, in future studies, the PASS thresholds should be calculated on the patients, both non-surgical and ACL-reconstructed patients, in the actual study as a part of the PRO assessment. In addition, data on body mass index, concomitant injuries and surgical treatment other than ACL reconstruction were not known in the non-surgically treated group. The matching was based on patient characteristics, independent of follow-ups, meaning that there could be differences between the two treatment groups at each follow-up. However, the large number of patients should have reduced the effect of this limitation.

Conclusions

A significantly greater proportion of patients treated with ACL reconstruction reported acceptable knee function, including QoL, compared with patients treated non-surgically after an ACL injury at cross-sectional evaluations up to 10 years after treatment. Patients with an ACL reconstruction consistently had a greater proportion exceeding the PASS cut-offs on all KOOS subscales, apart from the symptom subscale, at all follow-ups, with significant differences up to 25%. The results of this study should be interpreted in the light of the potential limitations including, but not limited to, attrition bias, selection bias and the unknown proportion of non-surgically treated patients registered in the SNKLR.

Key messages.

What is already known on this topic

Both non-surgical and surgical treatments are accepted treatment options after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury.

The choice of surgical or non-surgical treatment should be reached via a shared decision-making process that considers the patient’s presentation, goals and expectations as well as a balanced presentation of the available evidence-based literature.

What this study adds

This observational study suggests that a greater proportion of patients treated with ACL reconstruction exceeded the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) threshold associated with Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS), at all follow-ups, compared with patients treated non-surgically up to 10 years after an ACL injury.

The ACL-reconstructed group reported a superior KOOS4, a proxy for overall knee function, at all follow-ups, compared with the non-surgical group.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large, prospective long-term registry study comparing non-surgical treatment with ACL reconstruction after an ACL injury in a cross-sectional manner and using a patient-acceptable threshold value to interpret the results of patient-reported outcomes, but it is unknown whether this difference is clinically relevant.

How this study might affect research, practice or policy

This study confirms that both non-surgical and surgical treatments after ACL injury are widely accepted with the potential to restore satisfactory knee joint function.

The use of PASS to interpret patient-reported outcomes may help clinicians understand the prognostics and outcome after ACL injury.

The results of the current study suggest that at least one in three patients with an ACL injury, regardless of treatment, does not achieve acceptable knee function. This indicates a need for more research on treatments and their outcomes to improve knee function and quality of life for patients with an ACL injury, as well as determining which patients will benefit most from the individual treatments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank biostatisticians Bengt Bengtsson and Nils-Gunnar Pehrsson from Statistiska Konsultgruppen for help with the statistical analyses and advice on the interpretation of data.

Footnotes

Twitter: @senorski

Contributors: KP and EB drafted the initial version of the manuscript. EB, KP, AH, EHS and EHS contributed substantially to the acquisition of the data and the analysis of the data and they are responsible for drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. KS, VM and JK made large contributions to the revision and design of the work. EHS and KS are responsible for the concept of design. All the authors have read the final manuscript and given their final approval for the manuscript to be published. Moreover, all the authors agree to be accountable for every aspect of the research in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. EHS acted as the study guarantor.

Funding: This study received specific funding from the Healthcare Board, Region Västra Götaland, SE462 80 Vänersborg, Sweden, VGFOUREG-932137 and VGFOUREG-941429. In addition, the study was financed by grants from the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the county councils, the ALF-agreement (ALFGBG-942735).

Competing interests: VM declares consulting for Smith & Nephew. JK is the editor-in-chief of KSSTA. KS is a member of the Board of Directors for Getinge AB and consultant for Carl Bennet AB.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden, and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved this study (Dnr: 2011/337-31/3 & 2022-00913-01).

References

- 1. Diermeier TA, Rothrauff BB, Engebretsen L, et al. Treatment after ACL injury: Panther symposium ACL treatment consensus group. Br J Sports Med 2021;55:14–22. 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, et al. A progressive 5-week exercise therapy program leads to significant improvement in knee function early after anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010;40:705–21. 10.2519/jospt.2010.3345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, et al. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med 2010;363:331–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hurd WJ, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A 10-year prospective trial of a patient management algorithm and screening examination for highly active individuals with anterior cruciate ligament injury: Part 2, determinants of dynamic knee stability. Am J Sports Med 2008;36:48–56. 10.1177/0363546507308191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meunier A, Odensten M, Good L. Long-term results after primary repair or non-surgical treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a randomized study with a 15-year follow-up. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2007;17:230–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Musahl V, Karlsson J. Anterior cruciate ligament tear. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2341–8. 10.1056/NEJMcp1805931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. von Essen C, Eriksson K, Barenius B. Acute ACL reconstruction shows superior clinical results and can be performed safely without an increased risk of developing arthrofibrosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2020;28:2036–43. 10.1007/s00167-019-05722-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ardern CL, Sonesson S, Forssblad M, et al. Comparison of patient-reported outcomes among those who chose ACL reconstruction or non-surgical treatment. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2017;27:535–44. 10.1111/sms.12707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, et al. Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial. BMJ 2013;346:f232. 10.1136/bmj.f232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Collins NJ, Prinsen CAC, Christensen R, et al. Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS): systematic review and meta-analysis of measurement properties. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016;24:1317–29. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roos EM, Lohmander LS. The knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:64. 10.1186/1477-7525-1-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muller B, Yabroudi MA, Lynch A, et al. Defining thresholds for the patient acceptable symptom state for the IKDC subjective knee form and KOOS for patients who underwent ACL reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2016;44:2820–6. 10.1177/0363546516652888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hamrin Senorski E, Svantesson E, Beischer S, et al. Factors affecting the achievement of a Patient-Acceptable symptom state 1 year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a cohort study of 343 patients from 2 registries. Orthop J Sports Med 2018;6:232596711876431. 10.1177/2325967118764317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tubach F, Ravaud P, Baron G, et al. Evaluation of clinically relevant states in patient reported outcomes in knee and hip osteoarthritis: the patient acceptable symptom state. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:34–7. 10.1136/ard.2004.023028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roos EM, Boyle E, Frobell RB, et al. It is good to feel better, but better to feel good: whether a patient finds treatment 'successful' or not depends on the questions researchers ask. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:1474–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The Swedish Knee Ligament registry . Annual report, 2018. Available: https://www.aclregister.nu/media/uploads/Annual%20reports/annual_report_swedish_acl_registry_2018.pdf

- 17. Austin PC. A comparison of 12 algorithms for matching on the propensity score. Stat Med 2014;33:1057–69. 10.1002/sim.6004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Filbay SR, Grindem H. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2019;33:33–47. 10.1016/j.berh.2019.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grindem H, Eitzen I, Engebretsen L, et al. Nonsurgical or surgical treatment of ACL injuries: knee function, sports participation, and knee Reinjury: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96:1233–41. 10.2106/JBJS.M.01054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reijman M, Eggerding V, van Es E, et al. Early surgical reconstruction versus rehabilitation with elective delayed reconstruction for patients with anterior cruciate ligament rupture: compare randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2021;372:n375. 10.1136/bmj.n375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Snoeker BA, Roemer FW, Turkiewicz A, et al. Does early anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction prevent development of meniscal damage? results from a secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:612–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Terluin B, Eekhout I, Terwee CB. The anchor-based minimal important change, based on receiver operating characteristic analysis or predictive modeling, may need to be adjusted for the proportion of improved patients. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;83:90–100. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bjsports-2021-105115supp001.pdf (40.4KB, pdf)

bjsports-2021-105115supp002.pdf (18.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.