Abstract

Aims

To increase the quality and safety of patient care, many hospitals have mandated that nursing clinical handover occur at the patient's bedside. This study aims to improve the patient‐centredness of nursing handover by addressing the communication challenges of bedside handover and the organizational and cultural practices that shape handover.

Design

Qualitative linguistic ethnographic design combining discourse analysis of actual handover interactions and interviews and focus groups before and after a tailored intervention.

Methods

Pre‐intervention we conducted interviews with nursing, medical and allied health staff (n = 14) and focus groups with nurses and students (n = 13) in one hospital's Rehabilitation ward. We recorded handovers (n = 16) and multidisciplinary team huddles (n = 3). An intervention of communication training and recommendations for organizational and cultural change was delivered to staff and championed by ward management. After the intervention we interviewed nurses and recorded and analyzed handovers. Data were collected from February to August 2020. Ward management collected hospital‐acquired complication data.

Results

Notable changes post‐intervention included a shift to involve patients in bedside handovers, improved ward‐level communication and culture, and an associated decrease in reported hospital‐acquired complications.

Conclusions

Effective change in handover practices is achieved through communication training combined with redesign of local practices inhibiting patient‐centred handovers. Strong leadership to champion change, ongoing mentoring and reinforcement of new practices, and collaboration with nurses throughout the change process were critical to success.

Impact

Ineffective communication during handover jeopardizes patient safety and limits patient involvement. Our targeted, locally designed communication intervention significantly improved handover practices and patient involvement through the use of informational and interactional protocols, and redesigned handover tools and meetings. Our approach promoted a ward culture that prioritizes patient‐centred care and patient safety. This innovative intervention resulted in an associated decrease in hospital‐acquired complications. The intervention has been rolled out to a further five wards across two hospitals.

Keywords: clinical handover, communication, discourse analysis, ethnography, nursing, organizational development, patient safety, patient‐centred care

1. INTRODUCTION

Ineffective communication is a major cause of adverse events in hospitals around the world (Slawomirski et al., 2017; World Health Organization, 2013), resulting in patient harm and death (Garling, 2008) and triggering patient complaints (Taylor et al., 2002). One of the most ubiquitous, significant and problematic aspects of communication in hospitals is clinical handover, the transfer of responsibility and accountability for patient care between health professionals (Australian Medical Association, 2006). Inadequate handover communication is a key contributing factor to patient harm, with 80% of adverse events involving miscommunication during handover (Joint Commission International, 2018).

Improving handover communication to reduce adverse events has been a longstanding international policy imperative (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2012; Catalano, 2006; World Health Organization, 2007). Initiatives have included a shift towards patient‐centred approaches to care, prompting many hospitals to move handover from staff‐only areas to the patient's bedside. However, analysis of bedside handovers shows that many nurses struggle with the complex communicative demands of interactions in which they must simultaneously manage the informational and interactional aspects of this crucial point of transition in patient care (Della et al., 2020; Eggins & Slade, 2016a; Eggins et al., 2016). Although communication training can help nurses to conduct effective bedside handovers (Slade et al., 2018; Snyder & Engström, 2016; Tobiano et al., 2018), training alone is unlikely to result in sustained change to handover practices. Research suggests a more effective approach to practice change is integrating training into broader institutional change tailored to the local context—the organizational environment, culture and individuals (Dorvil, 2018; McMurray et al., 2010). Linguists argue that this local context should include the challenges and demands of actual communication practices during handover (Eggins & Slade, 2016a).

1.1. Background

The fact that clinical handovers are typically delivered verbally under time pressure and in far from ideal environments means communication risks are ever‐present. Ineffective communication during handover can result in unstructured handovers that may contain inconsistent, irrelevant or repetitive information (Manias et al., 2015; Spooner et al., 2016). Inaccurate or incomplete information is a potential safety issue, especially when clinicians do not adequately explain the reasons for their decisions (Eggins et al., 2016). Handovers can be monologic, lacking meaningful interaction between clinicians and/or with patients, and disciplinary hierarchies can mean that incoming staff are reluctant to ask questions that could clarify ambiguities or omissions (Eggins et al., 2016). Poor quality written documentation and the lack of an explicit transfer of accountability and responsibility can hinder continuity of care (Blair & Smith, 2012).

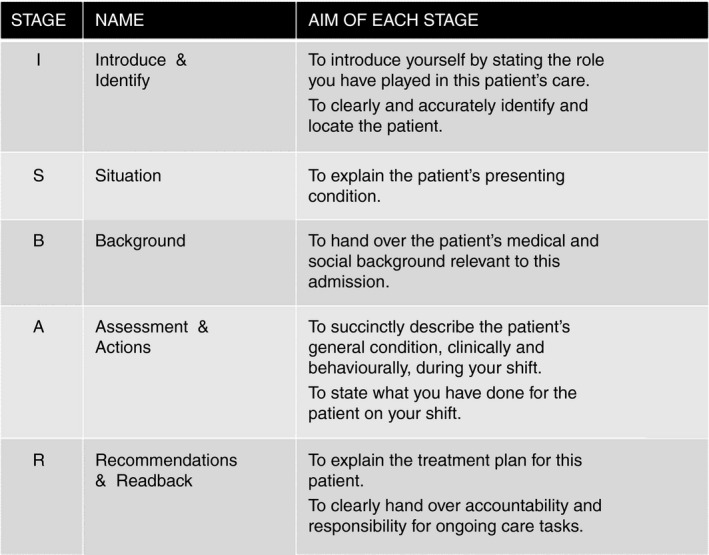

In Australia, failures in clinical handover have been identified as a major cause of preventable harm to patients (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2012). For over a decade the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) has been working to improve clinical handover (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2010). Standard 6 of the ACSQHC’s National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards provides criteria for effective communication to ensure safe patient care (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2017). For safe and effective handovers, the ACSQHC advocates (1) using structured handover tools such as the ISBAR protocol (Identify, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) to provide a framework for communicating the minimum information content (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2019a); and (2) prioritizing bedside handovers to support patient involvement (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2019b).

Structured handover tools help standardize information provided in handover. Two integrative reviews considering structured tools in nursing handover concluded that their use can enhance the handover process, including through improving communication skills, enhancing reliability of information transfer and fostering critical thinking (Anderson et al., 2015; Bakon et al., 2017). Systematic reviews on the impact of structured handover tools on patient safety found evidence that using tools like ISBAR could improve patient safety by reducing communication errors such as omissions and inaccuracies (Bukoh & Siah, 2020; Müller et al., 2018).

Complementing the need to make handovers structured is the equally important requirement that handovers be inclusive. In theory, bedside handover is an expression of a patient‐centred approach to care, recognizing a patient's right to participate in their health care. Bedside handovers can facilitate communication between nurses and patients, fostering the nurse–patient relationship and increasing nurse and patient satisfaction (Gregory et al., 2014; Mardis et al., 2016; Tobiano et al., 2018). Including patients in handover helps them stay informed about their condition and care plan, and encourages shared decision‐making (McMurray et al., 2011). Patient inclusion can also improve patient safety as patients can contribute information about their care and progress, correct errors, provide missing information and answer questions (McMurray et al., 2011; Tobiano et al., 2018). Bedside handovers have been associated with decreased patient falls and medication errors (Sand‐Jecklin & Sherman, 2013), and increased completion of certain nursing care tasks and documentation (Kerr et al., 2013).

However, simply conducting handover at the bedside does not guarantee patient inclusion. One study of over 500 bedside nursing handovers found patients were actively involved in fewer than half (Chaboyer et al., 2010). Actively involving patients in handover depends not only on proximity, but also on whether nurses’ communication practices foster patient engagement in the process (Dahm et al., 2022; Eggins & Slade, 2016a). Thus, nurses can benefit from training that provides them with the communication skills required to include patients in handover (Anderson et al., 2015; Drach‐Zahavy & Shilman, 2015; Tobiano et al., 2018). This study aims to improve the patient‐centredness of nursing handover by addressing the communication challenges of bedside handover and the organizational and cultural practices that shape handover.

2. THE STUDY

2.1. Aim

The aim of this qualitative study was to improve the patient‐centredness of nursing clinical handover in a targeted ward by developing, delivering and evaluating an intervention that addressed both the communication challenges of bedside handover and the range of situated practices that enabled and constrained patient‐centred communication during handover.

2.2. Design

The research team applied a qualitative methodology combining ethnographic and discourse analytic approaches (Eggins & Slade, 2012, 2016a; Eggins et al., 2016; Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004) to analyze actual nursing handovers, interviews and focus groups pre and post a tailored intervention. Our qualitative study aligns with the principles of the capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour (COM‐B) model (Michie et al., 2011). The COM‐B model describes how a person's capability (physical and psychological) and opportunity (social and environmental) influence motivation (reflective and automatic) to enact a behaviour. It is a useful framework for considering barriers to desired behaviours (e.g. patient‐centred handover practices) and designing interventions to address these. Qualitative evaluation is recognized as a way of evaluating the implementation of nursing interventions and improvements, particularly when interventions occur in natural settings (Rørtveit et al., 2020). Previous research on communication in hospital emergency departments (Pun et al., 2017; Slade et al., 2015) and clinical handover (Eggins et al., 2016) has demonstrated the effectiveness of our approach. The multidisciplinary research team was led by an applied linguist and included nurse–researchers, nurses and linguist research assistants (all female).

2.3. Sample and participants

The study was conducted in the Rehabilitation Ward of a New South Wales metropolitan teaching hospital as part of a larger multi‐site study across three affiliated hospitals. The Rehabilitation Ward is a 22‐bed inpatient ward specializing in care for patients with neurological, orthopaedic or musculoskeletal conditions. The ward has 28 nurses (16 full‐time, 12 part‐time), 5 medical staff and 18 allied health (7 full‐time, 11 part‐time) with a varied skill mix and scope of clinical practice (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Rehabilitation Ward staff

| Staff | Full‐time | Part‐time |

|---|---|---|

| Nursing | ||

| Registered Nurses including Nursing Unit Manager, Clinical Nurse Educator, Care Coordinator and Clinical Nurse Specialist | 13 | 8 |

| Enrolled Nurses | 3 | 3 |

| Assistants in Nursing | 0 | 1 |

| Medical | ||

| Consultants, Senior Registrars, Resident Medical Officers | 5 | 0 |

| Allied health | ||

| Physiotherapists, Occupational Therapists, Dieticians, Social Workers, Speech Pathologists, Clinical Neuropsychologists | 7 | 11 |

Hospital management selected this ward for the study following persistent difficulties in implementing hospital handover policy. This policy mandated the use of ISBAR to ensure the most important information is handed over in a structured format; and at least one bedside handover in a 24‐h period to facilitate the transfer of patient care needs from one shift to the next and provide an opportunity for patient and carer participation in handover. The policy also stipulated that during bedside handover the nurse on the outgoing shift must:

-

‐

introduce the patient to the oncoming shift nursing staff and introduce the nurse to the patient

-

‐

focus communication on patient care needs

-

‐

facilitate discussion on patient care concerns, condition changes and changes in proposed management

-

‐

ask the patient if they have any questions or comments

-

‐

invite the patient to confirm or clarify information

-

‐

refer to relevant charts, care plans or tools during bedside handover.

Nurses had only received an online ISBAR training module to support them to meet these requirements. The team also considered other ward handover practices relevant to the effectiveness of nursing handover, in particular the nursing‐led multidisciplinary team ‘huddle’ held each morning to share patient information among nursing, medical and allied health staff (Clinical Excellence Commission, 2017).

With the assistance of the Nursing Unit Manager (NUM) and using purposive sampling we recruited nursing, medical and allied health staff (n = 20) and nursing students (n = 7) for interviews and focus groups in phase 1, and nurses (n = 6) for interviews in phase 3. Maximum variation strategies were employed to ensure a diverse sample of participants in terms of clinical roles and level of experience. Recruitment ceased once we reached thematic saturation and no new themes were raised in interviews.

Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants for the recordings of nursing handovers to capture handovers that arose naturally as a part of the ward's routine. Inclusion criteria were: (i) clinicians engaged in giving or receiving clinical handover on the selected ward and willing to provide written informed consent and participate in the study; and (ii) patients over the age of 16, likely to be present on the selected ward while their care was handed over, with the cognitive and physical capacity to give written informed consent and willing to participate in the study. Patients with a history of a condition that inhibited their ability to understand the study were excluded.

2.4. Data collection

The study involved three phases: phase 1, pre‐intervention data collection in the nominated ward; phase 2, delivery of the intervention (communication training and organizational and cultural change recommendations), based on findings from analysis of phase 1 data; and phase 3, collection and analysis of post‐intervention data. Figure 1 summarizes the research process.

FIGURE 1.

The research process

Data were collected between February and August 2020. All interviews, focus groups and handovers were audio‐ or video‐recorded and professionally transcribed. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction. Prior to phase 1, two members of the research team (DS, LG) provided briefing sessions at the hospital to introduce themselves and inform ward staff and management about the research.

2.4.1. Phase 1: Pre‐intervention

In phase 1 (February 2020), four experienced qualitative researchers on the team (DS, LG, BB, MD) conducted 15 individual semi‐structured interviews (ranging between 15 to 75 min; 1 repeat interview) with nursing (n = 5), medical (n = 4) and allied health staff (n = 5) and 2 focus groups (11 and 26 min) with nursing staff (n = 6) and students (n = 7) on site. These were designed to elicit insider perspectives on the problems and challenges with ward handover practices. The interview schedule (adapted from Eggins et al., 2016) included open‐ended questions about nursing handover, potential problems and their impact on patient safety and quality of care, the skillset and patient information required for effective handover, the purpose and conduct of the multidisciplinary team huddles and the flow of patient information among team members. Four members of the research team (DS, LG, BB, MD) also observed and audio‐recorded 16 routine nursing handovers and 3 huddles. Thematic sketches of nurses’ positioning and movements during handover and materials (patient brochures and handover sheets) were also collected, de‐identified and analyzed.

2.4.2. Phase 2: The intervention

Based on phase 1 findings, in phase 2 (June 2020) the team presented ward management with an intervention. This consisted of 18 recommendations to improve ward handover practices, including the delivery of a communication training module to address the interactional and informational risks identified in the phase 1 data. In June 2020, the applied linguist and nurse–researcher delivered 2‐h communication in nursing clinical handover training sessions to 35 people, including nurses, ward‐ and hospital‐level management and a small group of allied health and medical staff. The evidence‐based training aimed to (1) improve the informational dimension of handover through use of ISBAR to structure both the handover sheet and the verbal handover; and (2) improve the interactional dimension of handover through use of the Connect, Ask, Respond, Empathise (CARE) protocol (Eggins & Slade, 2016b). The training explored with nurses the rationales for and advantages of bedside handovers so they recognized the value of this workplace practice. It also helped nurses develop collaborative strategies to address problems in handover delivery and communication identified in phase 1, including handling confidential information. The training featured video re‐enactments of handovers based on audio/video recordings of actual nurse handovers in Australian hospitals. During training nurses applied their knowledge of the ISBAR and CARE protocols to critique these re‐enactments and participated in handover role‐plays to gain the communication skills required to conduct safe and effective bedside handovers. The communication training was well received by participants, with 94% of participants who completed an evaluation form rating it on a scale of 1 to 6 as ‘6 very useful’.

In parallel with the training, the NUM oversaw implementation of a suite of recommendations made by the research team. Recommendations covered handover events, handover tools, cultural change and mentoring, and handover policy (Appendix S1). A key recommendation on handover events was the redesign of the multidisciplinary team ‘huddle’. In collaboration with staff, this became a short risk‐focused safety meeting and a template was developed to structure the meeting around patient safety risks. The NUM and the Clinical Nurse Educator facilitated a staff working group to redevelop the nursing handover sheet to reflect the ISBAR protocol. Throughout the intervention, the NUM and Clinical Nurse Educator were present on the ward to observe staff conducting handover. They provided real time mentoring to reinforce training in the ISBAR and CARE protocols, listened to staff feedback on the intervention and supported staff through the transition to bedside handover. The Clinical Nurse Educator spent additional time mentoring new and less experienced nurses on using the dual protocols to conduct bedside handover. New staff were also given the opportunity to observe and conduct bedside handovers while supernumerary.

2.4.3. Phase 3: Post‐intervention

In phase 3 (August 2020), the team returned to the ward 6 weeks after the intervention to assess its impact on ward handover practices and attitudes. Two members of the research team (DS, JT) conducted six individual semi‐structured interviews (ranging between 18 and 51 min) with nursing staff (n = 6), asking them to reflect on the training and associated changes to ward culture and handover practices. We observed, recorded and analyzed three nursing handovers.

2.5. Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the participating hospital. Participants were given a verbal and written explanation of the aims of the research, a statement of their right to choose to participate or not and an assurance of confidentiality. All participants provided written informed consent.

2.6. Data analysis

All audio/video‐recorded data were transcribed, de‐identified and assigned a code or pseudonym for analysis. The interview and focus group data were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six‐phase approach to thematic analysis. Two members of the research team (MD, LC), one of whom had not been involved in data collection and brought a fresh perspective to the analysis, immersed themselves in the data through repeated reading, noting initial ideas for coding. They then generated initial data‐driven codes independently keeping code books in Microsoft OneNote. Together they sorted codes into potential themes and used the principle of constant comparisons to ensure coherence with the coded extracts and the dataset as a whole. This meant potential themes were iteratively reviewed and refined. The data were managed in Microsoft Excel.

The audio‐recorded nursing handover data were analyzed linguistically by DS, MD, LC, BB drawing on tools from functional linguistics, in particular, Systemic Functional Linguistics (Eggins, 1994; Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004). We analyzed the informational dimension of handover (how nurses organize and express clinical information about the patient) using an adapted version of the ISBAR protocol. The ISBAR protocol (Figure 2) re‐glosses the ISBAR elements in nursing‐oriented terms to help nurses transfer patient information in a logical, coherent sequence. We analyzed the interactional dimension of handover (how nurses interact with patients) using the CARE communication protocol developed and validated by DS and her team (see Eggins & Slade, 2016b; Pun et al., 2019). The CARE protocol (Figure 3) provides nurses with strategies to improve the quality of interaction with the patient to support patient inclusion and safety. By identifying the informational and interactional structures according to the ISBAR and CARE communication protocols, we could evaluate whether the handovers fulfilled their dual goals of communicating the minimum information content in a structured manner and enabling patient inclusion.

FIGURE 2.

The ISBAR protocol (Identify, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) adapted for nursing handovers

FIGURE 3.

The CARE protocol (Connect, Ask, Respond, Empathise) for bedside nursing handovers

By triangulating findings from the thematic analysis of interview and focus group data with observations, linguistic analysis of interactions and nursing documentation, we were able to combine information about what people said they did with what they actually did (Eggins et al., 2016; Mays & Pope, 1995).

2.7. Rigour

Researchers employed several strategies described by Creswell and Creswell (2017) to ensure qualitative validity and reliability of the study. Strategies to confirm validity included triangulation of data collected through multiple sources (interviews and focus groups, observations, interactions and documentation) and member checking to confirm the accuracy of our findings. We conducted a follow‐up briefing with a senior nurse to discuss preliminary findings and co‐construct several recommendations. Additionally, we engaged with ward management to discuss draft findings and verify recommendations. Strategies to confirm reliability included checking verbatim transcripts against recordings for accuracy prior to analysis, cross‐checking codes derived independently and, for the linguistic analysis, resolving disputes over interactional and informational categories though group discussion. In terms of the communication training, pre and post studies evaluating the impact of the CARE and ISBAR protocols have shown their efficacy in improving nurse understanding and practice of bedside handover (Pun et al., 2019; Slade et al., 2018). Finally, the study is reported in accordance with Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (O’Brien et al., 2014) and the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (Tong et al., 2007; Supplementary Material).

3. FINDINGS

3.1. Phase 1: Pre‐intervention findings

Analysis of phase 1 ethnographic observations, interviews and focus groups and audio‐recorded handover interactions revealed shortcomings in handover delivery and communication. The researchers found that these communication issues were directly shaped and constrained by systemic factors in the organizational and cultural context of the ward (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

The impact of systemic factors on handover delivery and communication

3.1.1. Problems in handover delivery and communication

Inappropriate handover location

Despite hospital guidelines mandating bedside handover, most handovers occurred in the corridor or just inside the patient's room, not at the bedside. Nurses stated strong concerns about confidentiality, which they said hampered their ability to conduct handover at the bedside in earshot of other patients. One nurse stated that nurses were ‘always thinking that confidentiality is an issue’ and were uncertain about ‘what can and can't I say in front of the patient’ (Registered Nurse [RN] 2). How nurses perceived patient preference also determined handover location. Nurses felt that some patients found it ‘off‐putting to have a bedside handover’ because they overheard what was being said about them and other patients (RN focus group 2).

Lack of patient involvement

The nurses’ preference to conduct handover in the corridor meant that patient involvement in handover was low and often limited to a greeting. Nurses did not see handover as an opportunity to involve patients in their care, but rather focused on the quick transfer of information as described by this nurse:

Because our patients are here months and months […] we know them pretty well. It’s important for the handover just to tell us what changes, any medication changes … […] Just come to the main points. That’s what we are trying to do. So that way we’re not wasting time. So the handover gets finished faster. (RN focus group 2)

Table 2, ‘Rebecca’, is representative of the naturally occurring handovers recorded in phase 1. In this example, an incoming nurse walks into Rebecca's room to greet her, before returning to the corridor for handover. Despite being in earshot, the nurses talk about Rebecca as if she is not present, referring to her in the third person (‘She is eating, drinking well’; ‘her mobility is poor’) or omitting the pronoun altogether to talk only of her body parts and processes (‘didn't open bowels’).

TABLE 2.

‘Rebecca’ corridor handover

| Turn | Speaker | Talk | ISBAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Outgoing N: | That's Rebecca. (Rebecca's room) | I |

| 2. | Incoming N1: | (5 sec) [quietly in background] (Hi Rebecca, how are you?) | |

| 3. | Incoming N2: | She's in Room 9, isn't it? | |

| 4. | Incoming N2: | Rebecca==She's in Room 9. | |

| 5. | Outgoing N: | ==Rebecca. 33 years, female, diagnosis (HD) upper‐ [very quietly] ( ) we give her shower so we give her wash and her mobility is four wheel walker standby assist and whole day she just ( ) to want to stay in her bed. She is eating, drinking well. We feed her [combined] with medication, obs stable, normal. |

I A |

| 6. | Incoming N1: | Thank you. | |

| 7. | Outgoing N: | Oh, and didn't open bowels. | A |

| 8. | Incoming N1: | [quietly] That's her. |

Key: (words in parentheses) indicates transcriber's doubt; ( ) impossible to transcribe; == signals overlap with another speaker.

Abbreviation: ISBAR, Identify, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation.

Even when nurses gave handover at or near the bedside, patients were rarely involved. The outgoing nurse rarely introduced patients to the incoming team and rarely told them which incoming nurse would be looking after them. One nurse commented on the lack of patient involvement in bedside handover suggesting that some nurses had not changed their communication during handover to facilitate patient inclusion:

I know bedside handover is a good idea, but I notice often we older nurses are still practicing the same [at the bedside] as if we were [giving handover] out of the room. (RN3)

The transcript in Table 3, ‘Jim’, shows that the patient's involvement is limited to a greeting, despite the fact that the handover is conducted at the bedside. The outgoing nurse does not introduce Jim to the incoming team or invite him to contribute. Several discourse features hindered patient involvement. The outgoing nurse's repeated use of the judgmental term ‘refuse’ (turns 3 and 5) implies that Jim is not being cooperative. Her use of reported speech in turn 3 (‘He said he's gonna shower in the afternoon’) implies that Jim may not be telling the truth. The remark ‘Always say’ (turn 4) appears to imply a claim such as ‘Jim/patients always say that’, which Jim may perceive as critical.

TABLE 3.

‘Jim’ bedside handover

| Turn | Speaker | Talk | ISBAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Incoming N1: | Ji:::m, Hello Jim. Hi, how are you? | |

| 2. | Patient (Jim): | ( ) | |

| 3. | Outgoing N: | Another handsome man. ( ) pleasant. Uh so Jim is 80 years old. He came with a total hip replacement on eighteenth of eleventh … 2019. Uh his mo‐ his mobility is independent. He refuse shower. He said he's gonna shower in the afternoon‐ early afternoon. |

I S A |

| 4. | Nurse: | [quietly] ( ) always say. | |

| 5. | Outgoing N: | What else? He walking, he refused Coloxyl and Senna this morning he said, because he opened the bowel yesterday. He is walking independently. His observations is good, so he settled. Aren't you? | A |

| 6. | [No audible response from patient. The outgoing nurse moves straight onto handing over the next patient in the same manner] |

Key: ::: elongated vowel sound; … short pause.

Abbreviation: ISBAR, Identify, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation.

Relatives were also rarely invited to participate in handover. When they did contribute, often uninvited, nurses often did not acknowledge or respond to their comments with rapport or empathy. In Table 4, ‘Dolores’, an extract from a naturally occurring bedside handover, although Dolores’ son tries to contribute information about his mother's loss of consciousness (turns 31 and 33), the outgoing nurse speaks over his attempts (turns 32 and 34), before shutting him down both physically (turn 35) and verbally (turn 36) to continue the handover. Later, when Dolores’ son talks about his personal experience with his mother's condition (turns 39, 41, 43, 45 and 47), the outgoing nurse interrupts to continue handover (turns 44, 46 and 48). Her failure to acknowledge the son's contribution shows a lack of respect for his experience and the valuable clinical information this represents.

TABLE 4.

‘Dolores’ bedside handover

| Turn | Speaker | Talk | ISBAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30. | Outgoing N: | So I quickly took her a few steps to the bed and soon she says to me, that she's not feeling good. So she starts to lean on me and then she just stopped talking. So lost‐ lost consciousness== | A |

| 31. | Patient's son: | ==yes yeah== | |

| 32. | Outgoing N: | ==about 10 seconds or something. ==So I just quickly… | A |

| 33. | Patient's son: | ==She has bla‐ she has blackouts. | |

| 34. | Outgoing N: | ==Blackouts, ==yeah. | |

| 35. | Patient's son: |

==yeah == we've ( ) yeah [Outgoing nurse turns her back on son and husband] |

|

| 36. | Outgoing N: | ==So I just quickly put her back to bed and I was calling [nurse manager's name] because no one was around, I was like shouldn't I just== | A |

| 37. | Patient (Dolores): | ==no one comes | |

| 38. | Outgoing N: | ==call Code Blue. But lucky Dr [doctor's name] was here, so she came to assess her. She says, pretty normal common for her. So actually doctor made a plan for her, said if she's having these pass out, like … doesn't‐ like her‐ herself doesn't come back in one minute, we need to call Code Blue, otherwise we just call her, you know, shake her. Because ==she… | B |

| 39. | Patient's son: | ==Yeah, she's come to within about a minute. You know. If you‐ | |

| 40. | Outgoing N: | Yup | |

| 41. | Patient's son: | If you put her on her back | |

| 42. | Nurses: | ==Mm‐hm | |

| 43. | Patient's son: | and put a pillow, she'll sort of … | |

| 44. | Outgoing N: | Yep, ==actually after we… | |

| 45. | Patient's son: | ==It's usually less than a minute. | |

| 46. | Outgoing N: | Yeah, after we== put her back to bed … | |

| 47. | Patient's son: | ==She can't remember anything. ==She can't remember doing it. | |

| 48. | Outgoing N: | ==she ( ) and then she starts the talking. She still says she's not feeling well, but we tilt the bed down and we re‐ re‐check her blood pressure and then actually her blood pressure went up very high. (…) | A |

| 49. | [Outgoing nurse continues assessment] |

Abbreviation: ISBAR, Identify, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation.

Lack of information structure

Despite hospital guidelines mandating the use of ISBAR, there was little adherence to an ISBAR‐derived minimum dataset. The ward's handover sheet did not reflect the ISBAR structure. Nurses described the information provided in handover as ‘inconsistent’ and ‘not really following ISBAR’ (RN2). Nurses were aware of the potential risks to patient safety, acknowledging that this lack of structure meant that ‘important things get missed’ leading to ‘patient safety incidents […] like falls and not actually handing over what we are doing about the falls risk patients’ (RN2).

The lack of a protocol to present information systematically is evident in two naturally occurring handovers—the ‘Rebecca’ (Table 2) and ‘Jim’ (Table 3) handovers. In these examples, the ISBAR stages Identify and Situation are minimal; the outgoing nurses focus on providing Assessment. As one student nurse said, nurses ‘hand over what happened during that shift and that's about it’ (Student nurse, focus group). In both handovers the Background stage is not covered, nor are any Recommendations offered. These were typical omissions in pre‐intervention handovers. Student nurses expressed concern about the practice of omitting the patient's background and leaving ‘it to us to read all about that’ in the medical file (Student nurse, focus group). The practice of omitting the Recommendation stage poses risks to continuity of care as the care plan is not summarized and lines of responsibility and accountability for patient care tasks are left implicit.

3.1.2. Systemic issues related to ward organization and nursing culture

As the examples in Tables 2, 3, 4 presented above show, there was a marked disconnect between nursing clinical handover policy and actual ward practice. Analysis of observations, documentation and interview data suggested that this apparent disregard of handover guidelines was the result of systemic issues related to organizational and cultural factors in the ward context.

Organizational barriers to handover

Lack of awareness of hospital and national policy and guidelines

There was little evidence that ward nurses were familiar with national (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2017) and state (Clinical Excellence Commission, 2019) handover guidelines or hospital handover policies. Nurses did not refer to these in interviews or focus groups.

Ritualized but ineffective handover routines

The nursing‐led multidisciplinary team huddles did not follow the recommended structure or content described by the Clinical Excellence Commission (2017) policy. The meetings followed a patient‐by‐patient sequence with the presenting nurse sometimes providing information that was irrelevant to other disciplinary groups. As a result, the meetings were lengthy, inefficient and failed as a means of communicating critical patient information among the multidisciplinary team. There were no formal processes to ensure the ward nurses were informed about relevant patient information for their shift. Rather, one nurse described how the team leader attending the huddle would ‘have a chat’ (RN3) with the ward nurse to pass on relevant updates. The huddles appeared to have become a ward ritual, recognized by participants as often tedious and inadequate but persisting unchallenged. As one nurse noted, ‘With multidisciplinary team huddles there's no structure there and there is inconsistency, information gets missed, there's lots of gaps in there’ (RN2).

Practical organizational constraints on compliance with guidelines

Nurses often could not conduct handovers consistent with the hospital's policy because despite being outlined in guidelines, handovers rarely started on time, ran longer than recommended and were frequently interrupted.

Cultural barriers to handover

Culture of non‐accountability of nurses

Accountability and responsibility for patient care were not clear, allowing for some ‘buck passing.’ Nurses indicated that they did not see themselves as responsible or accountable for all patients on the ward. One nurse noted that there was a tendency to ‘pass the buck to the doctor or the allied health clinicians and say, “Patient has this. Doctors informed. Full stop”’ (RN2) as if to excuse themselves from further responsibility for care. Another nurse spoke of how this lack of accountability and responsibility for patient care negatively affected communication between staff:

It’s kind of the culture of nurses to say, “I don’t know anything about it”. [So it’s important to] keep the communication open between different people who come to your unit, you can’t shut them down by saying … “I’ve just been to lunch. I’ve no idea”. It’s not good communication. (RN1)

Because patient allocation occurred after the handover had been delivered, responsibility and accountability were not transferred directly to the incoming nurse responsible for each patient.

Lack of valuing of and commitment to patient‐centred care

In the interviews and focus groups, no nurses spoke about the many benefits of a patient‐centred approach to care. Patients and carers were not made aware of handover times nor invited to participate. Some nurses did, however, acknowledge that they should be ‘including the patient during the whole process’ (RN8), suggesting a general awareness of the issue of patient inclusion in handover. Such comments highlighted a need for training in how to communicate inclusively, negotiate the presence of family and carers, and manage their input during handover.

Hierarchical constraints against speaking up

Nurses also reported internal hierarchies that made it difficult for junior and student nurses to speak up about concerns or ask questions. One student nurse reported feeling alienated by the hierarchical culture:

Then some of them [nurses], I don’t think they like students, so they just look at us like, to say ‘don’t just stand there and harass us all day'. (Student nurse, focus group)

As a result, professional learning opportunities for junior and student nurses were missed. These students expressed a need for mentoring and guidance on how they should conduct handover and write in patient medical records. One student nurse commented on the difficulty of working effectively without guidance:

Normally the morning shift, most of the nurses they are really busy because it’s nearly time for the medication and everything. So, no one—I mean, what’s going on we don’t know. We have to find out later and we can’t ask them because they are very busy and we don’t want to interrupt while they are giving medication as well. (Student nurse, focus group)

3.1.3. Summary of phase 1 findings

Overall, these findings demonstrated the need for an intervention that combined communication training in bedside handover with a suite of recommendations designed to create organizational and cultural change to make bedside handover possible, productive and respected.

3.2. Phase 3: Post‐intervention findings

Six weeks after the intervention, the research team returned to the ward to record interviews and handovers and observe uptake of the recommendations. This post‐intervention data revealed improvements to handover communication, ward organization and nursing culture.

3.2.1. Changes in handover delivery and communication

Bedside handover location

Nurses reported that handovers routinely took place at the patient's bedside rather than in the corridor. Nurses did not mention their previously strongly held concerns about patient confidentiality; nor held on to earlier claims that patients did not want bedside handovers. These findings suggest the training had successfully explained the rationale for bedside handover and allayed nurses’ concerns. Acknowledging the benefits of this practice for patients, one nurse commented that patients now knew ‘the exact nurse who's going to be looking after you throughout the day. […] whatever question you have, this is the person for you to answer [ask]’ (RN11). She also remarked that nurses could now visualize the patient, noting the benefits for providing patient care:

When you’re around the bed, you seem to like just look on the board behind them, their mobility, the patient’s face, how they’re sitting, how they’re positioned, small things like that made a big difference in terms of how we can look after this patient better, rather than standing outside not knowing who’s going to be behind the curtain. (RN11)

Increased patient involvement

Reflecting this deeper appreciation for patient‐centred approaches to care, nurses actively involved patients in the handover and interacted with them beyond the previously token greetings (discussed below in the naturally occurring bedside handover in Table 5). Nurses acknowledged a change in attitude towards patient inclusion in handover. Nurses felt that the emphasis was ‘now with the interaction with the patients’ (RN9) and this had ‘given the patients that opportunity to be a bit more involved in their care planning’ (RN3). Nurses reflected on the many benefits of involving patients in handover, explaining that they were ‘more up‐to‐date with what's going on with the patient’ (RN9). They also noted that patients could contribute information about their care, correct errors, provide missing information and answer questions. One nurse stated that greater involvement ‘gives the patients an opportunity to say, no, that's wrong’ (RN9), while another commented that ‘asking the patient, is there any concerns? Is there something you want to add?’ (RN11).

TABLE 5.

‘Ruth’ bedside handover

| Turn | Speaker | Talk | CARE | ISBAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Incoming N1: | Hello hello. | Connect | |

| 2. | Incoming N2: | We just … we are still waiting for a mask. | ||

| 3. | Incoming N1: | Oh Ruth is here lah. How are you, Ruth? | Connect | |

| 4. | (Patient) Ruth: | Not too bad ==thank you | ||

| 5. | Incoming N1: | ==That's good [chuckles] You look good. | Connect | |

| 6. | Incoming N2: | Are you still waiting for the mask? | ||

| 7. | [Overspeaking] | |||

| 8. | Outgoing N: | Hi Ruth. Um you know me, I’m Jane, this is afternoon nurse you know Poh, ==Anna | Connect | I |

| 9. | Ruth: | ==Yes [nodding] | ||

| 10. | Outgoing N: | and Vicky are going to look after you today. So Ruth, we moved her to this room this afternoon before lunch because we needed some bed for the male patient there. So she was happy. And very kind. |

Connect Empathise |

I |

| 11. | So you know Ruth, a (85) year old female, her medical diagnosis is here with a history of diabetes. Uh this morning she went for physiotherapy and they changed her mobility to a four‐wheel walker now. So she needs only supervision with mobility. How are you doing with that, good isn't it? | Ask |

I S B A |

|

| 12. | Ruth: | Good ==good. | ||

| 13. | Outgoing N: | ==Did you like the walker? | Ask | |

| 14. | Ruth: | Yeah ==yes, it's good. | ||

| 15. | Outgoing N: | ==Yeah. So before she went for physiotherapy she had some PRN Endone 2.5 milligram, and it worked well, isn't it, Ruth? |

Respond Ask |

A |

| 16. | Ruth: | Yeah. | ||

| 17. | Outgoing N: | Endone. Yeah. | Ask | |

| 18. | Ruth: | Yeah. | ||

| 19. | Outgoing N: | So no other pain complaint after that. Her vital observation between (the flags) this morning, blood pressure fantastic, no high between (the flags). No clinical review, you know she has got the altered criteria which is due to change today. So I check with the doctor if they have changed it already or not. But her blood pressure is really very good. Continue fluid balance chart and her weight is 87.7 ==and this is very happy news for Ruth. | Empathise |

A |

| 20. | Incoming N1: | ==Oh: good! ==[laughing] Dropped 2 kilos. | Empathise | |

| 21. | Ruth: | ==[chuckling] It's coming down. | ||

| 22. | Incoming N1: | Yeah! | Respond | |

| 23. | Outgoing N: | So she has dropped nearly one kilo in two days almost yep. [moves closer to patient] So you can see the legs are getting better now. It is less cellulitis. | A | |

| 24. | Incoming N1: | [walks over to patient to check her legs] Can I just have a look? [patients starts to lift her pants to show her left leg] oh:: | Ask | |

| 25. | Outgoing N: | It's ==less now. | ||

| 26. | Incoming N1: | It's ==still quite ( ) is it. I think you need to elevate your legs. | Ask | |

| 27. | Ruth: | I did. That's why I’ve got the bed up. | ||

| 28. | Incoming N1: | Good, good. [checking the right leg] How's the other one? |

Respond Ask |

|

| 29. | Ruth: | Yes, it's … yep. | ||

| 30. | Incoming N1: | ==Okay [nodding] okay, all right. | Respond | |

| 31. | Outgoing N: | ==So dressing was due today, and I changed already and just to clean with normal saline and– sorry normal saline and a (Mepilex border). It is improving, there is no sloughiness or oozing or discharging from anything so we'll continue with the second daily dressing. Uhm, doctor– sorry pathology lady took some blood this morning and for the ==INR. |

A R A |

|

| 32. | Incoming N1: | ==INR, yep. | ||

| 33. | Outgoing N: | So yesterday the blood result was good. So she did have some Warfarin with 1.8 INR. Let's see today what doctor going to chart it out, you know. But so far, no other issues. Anything you want to add Ruth? Any concerns? | Ask |

A R |

| 34. | Ruth: | No, no. No concerns. | ||

| 35. | Incoming N1: | ==Ah good. | Respond | |

| 36. | Outgoing N: | ==Anything you worry, or anything you want to tell nurses for this afternoon? | Ask | |

| 37. | Ruth: | No. | ||

| 38. | Outgoing N: | Yeah, the reason why Ruth choose this side bay is because it's easier for her to ==go to the toilet, it's just close by. | B | |

| 39. | Incoming N1: | ==go to the toilet. Mm. | ||

| 40. | Outgoing N: | And before it was stand by assist, but now it is just with ==supervision. | A | |

| 41. | Incoming N1: | ==Supervision. Good good. | ||

| 42. | [Over speaking] | |||

| 43. | Outgoing N: | Thank you. | Connect | |

| 44. | Incoming N2: | So we'll see you… | ||

| 45. | Outgoing N: | All good, my dear. | Connect | |

| 46. | Ruth: | Okay, thank you. | ||

| 47. | Incoming N1: | Thank you. We'll see you later, Ruth. | Connect | |

| 48. | Ruth: | Thank you. |

Abbreviations: CARE, Connect, Ask, Respond, Empathise; ISBAR, Identify, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation.

Implementation of communication protocols

Analysis of the video‐recorded handovers indicated that the communication training had helped nurses gain communication skills to manage the interactional and informational issues identified in phase 1. Participants identified the CARE and ISBAR protocols as the most useful components, commenting that these had helped them structure their handover interactions:

I like this framework. I see the opportunity to improve clinical handover in terms of making it more interactive, including the consumer, empowering the nurses to own it […] I think it gives them structure, and it gives them something to reference, a reference point. It’s very clear about the objectives, about where it fits in with communicating for safety, where it fits in with team leader roles, individual nurses’ accountability. (RN2)

Following the training nurses more often sequenced information in the systematic structure of the ISBAR protocol, thereby providing a minimum dataset of information for bedside handover. Nurses noted the importance of restructuring the handover sheet by ISBAR to facilitate this change:

Redesigning the handover tool so it supported ISBAR. I think that was a big thing for them. Previously the handover tool was very messy, it was not structured. (RN3)

The transcript in Table 5, ‘Ruth’, a naturally occurring bedside handover, exemplifies the changes to communication practices observed in the post‐intervention phase. The nurses apply the CARE protocol to actively involve Ruth in the handover. The incoming nurse engages Ruth directly by greeting her (turns 1, 3 and 5), empathically sharing joy in her progress (turns 20 and 22) and having a conversation while examining her legs (turns 24, 26, 28 and 30). The outgoing nurse introduces herself and the team (turns 8 and 10) and encourages Ruth to contribute information frequently (turns 11, 13, 15, 33 and 36). Both nurses demonstrate active listening by responding to input from Ruth (turns 22 and 28). While the nurses do address Ruth by her first name, there is still a residue of earlier practices, with the nurses regularly referring to Ruth using pronouns ‘her’ and ‘she’ rather than addressing Ruth directly with ‘you’, as had been suggested in the training. In terms of structure, the outgoing nurse applies the ISBAR protocol to organize the information she is handing over in a logical sequence, with the exception of the information provided at the end to flag a patient safety issue (turns 38 and 40). Each ISBAR stage is covered, although the outgoing nurse does not seek Readback to ensure shared understanding and clearly hand over accountability and responsibility for Ruth's ongoing care tasks.

3.2.2. Changes to organizational practices and cultural attitudes

Organizational changes

Team huddle reconceptualised

The multidisciplinary huddle, renamed the Rapid Risk Meeting, had become an efficient 10‐min meeting that fulfilled its function of communicating critical information on patient safety concerns among team members, as noted by this nurse:

I think the Rapid Risk Meeting has seen great benefits. It’s brought the multidisciplinary team together. […] It’s risk‐focused, it’s management of the risks, there’s open discussion between the multidisciplinary team, they’re involved in the discussion, the decisions that come out of that meeting. I think that’s been a key piece in changing the culture and bringing that multidisciplinary team engagement across the floor. (RN3)

This change, combined with the introduction of formal processes to facilitate the flow of patient information from the Rapid Risk Meeting to ward nurses, meant that ‘all the team knows who they have to prioritize and who they have to be careful with the safety for patients’ (RN10).

Practical changes

The intervention had also prompted considerable changes to practical dimensions of handover. Patient allocation occurred before handover so that responsibility and accountability for care were handed over from the outgoing nurse to an identified incoming nurse. Changes to ward routines meant that handover was able to commence on time and did not take longer than 30 min. Information sheets were displayed around the ward, notifying patients and carers of the time and purpose of bedside handover and inviting them to participate.

Changes to nursing culture

The intervention provided the impetus for positive change to aspects of ward nursing culture. Nurses noted ‘more professionalism’ (RN10) exhibited on the ward and commented that the training had ‘encouraged [them] to be accountable for their shift and the care that they've provided’ (RN2). This increased sense of professionalism was accompanied by the nurses’ increased appreciation of the value of patient‐centred care. One nurse suggested that patient‐centred care helped develop the nurse‐patient relationship, stating that it is ‘good for the patients to know who's looking after them in the afternoon, that familiar face’ (RN9). Another nurse raised the importance of patient‐centred care in helping patients understand their condition and care plan:

For the patient it is important because they know why I’m in Rehab and what is the goal that’s set for me. […] So, they know that this is the plan. […] It improves care of the patient. (RN10)

The intervention also facilitated a turnaround in the hierarchical aspects of ward culture that previously alienated junior and student nurses. After the intervention, nurses embraced a culture of mentoring and modelling practice to student and junior nurses. Student nurses were routinely buddied up with nurses to support their professional development. Nurses articulated the benefits of mentoring inexperienced nurses and modelling handover practice:

If a junior nurse comes along and you have someone who really supports this framework … it really helps them lay the foundation … doing it the correct way. This is the way we do it. I guess they adapt [adopt] it in their practice. (RN9)

3.2.3. Impact on patient outcomes

The hospital routinely collects data from its reporting system to analyze trends in inpatient falls, hospital‐acquired pressure injuries and medication errors. As a qualitative study we did not assess the impact of the intervention on these patient safety measures; however, the observed improvements to patient outcomes are worth noting. The monthly average over a 9‐month period following training and implementation of the recommendations (July 2020 to March 2021) was compared with the monthly average of the same period over the previous 3 years (July to March in 2017/18, 2018/19 and 2019/20). There was a 48% reduction in inpatient falls (M = 3.9 vs. 2.0); a 20% decrease in the number of hospital‐acquired pressure injuries (M = 0.6 vs. 0.4); and a 43% reduction in medication errors (M = 0.8 vs. 0.4). Following the intervention, the Rehabilitation Ward went 86 consecutive days without a patient fall. Prior to this the average rate of patient falls was 4 per month. Nursing management attributed these improvements in patient safety, at least in part, to the intervention and its implementation:

It’s communication. It’s all the communication elements coupled with leadership and the [clinical nursing handover] project is the vehicle. So, without having a vehicle to pin the leadership to, which was the communication piece, you flounder. […] The increased communication coupled with the leadership saw an associated reduction in falls, pressure injuries and medication errors. (Nurse Manager 1)

3.2.4. Key drivers for intervention success

Several key drivers were critical to the success of the intervention including strong ward‐level leadership, engaging nurses in the change process and ongoing support from nursing leadership during the intervention phase and beyond. Leadership at the ward‐level was crucial to take accountability for change and set clear expectations for nurses. One nurse commented that the NUM had ‘been very good at setting the agenda, driving it and setting the […] program, [saying] this is what we want to see’ (RN2). Including nurses to become part of the change process helped facilitate changes in ward culture and practice. As RN2 remarked:

I think that engagement with the nursing team where they’ve been able to be a part of the change from the start. So we’ve brought them along the journey. So they participate in the training and then after the training, there were a lot of discussions […]. That involvement from the start I think has really increased their engagement. In not only better bedside [project name] but other things, other changes in the ward. It’s had a really big cultural, like it’s impacted on the cultural change. (RN2)

The ongoing mentoring and continued reinforcement of the practice changes were crucial to emphasize management expectations and consolidate new practices. RN3 commented on the intensive mentoring carried out by the ward's Clinical Nurse Educator:

So the Clinical Nurse Educator for the past few weeks has been on the floor at 1:30 every day that she’s been here, following them, observing, giving them real time feedback. So she’d pull them‐ you know, after a handover, she’d tell them what she picked up on that was good and give them a bit of constructive feedback as well. (RN3)

4. DISCUSSION

This study combined ethnographic and discourse analytic approaches to analyze handover practices in a local ward context. The research team made ward‐level recommendations and developed communication training to address the identified context‐specific organizational, cultural and communicative challenges to bedside handover.

The results of this study suggest that the research team's evidence‐based approach to communication training helped nurses recognize the importance of handover as a critical communicative event and appreciate their essential role in it (Waters, 2019). Recent reviews on nursing bedside handover (Anderson et al., 2015), patient participation in nursing handover (Drach‐Zahavy & Shilman, 2015; Tobiano et al., 2018) and patient involvement at the micro‐level of healthcare (Snyder & Engström, 2016) have highlighted the need for specific communication training for clinicians to foster patient inclusion in their care. Our communication training helped nurses better appreciate the principles of patient‐centred care and recognize the benefits of patient inclusion to quality of care and patient safety. Training in the CARE protocol gave nurses practical strategies to address the interactional risks in handover and resulted in more meaningful and useful interactions with patients and colleagues. Using these strategies helped nurses switch from talking about patients as if they were not present to, for the most part, talking with them during handover. Training in the ISBAR protocol equipped nurses with a structured tool to address informational risks and helped nurses transfer more complete information in a more logical sequence, supported by the ISBAR‐structured handover sheet. These findings are consistent with previous studies investigating use of the CARE and ISBAR protocols to improve communication during handover (Pun et al., 2019, 2020; Slade et al., 2018).

In addition to improving communication during handover, our results suggest that training in conducting bedside handover can effectively address nurse attitudes towards this practice that function as a barrier (Tobiano et al., 2017). Consistent with recent research (Anderson et al., 2015; Manias et al., 2015; Tobiano et al., 2018) nurses held particular concerns about maintaining patient confidentiality during bedside handover, despite patients not having a strong preference for how sensitive information is handled (Whitty et al., 2017). These concerns contributed to a preference for conducting handover in the corridor, excluding patients from participating in their care. The observed change in handover location from corridor to bedside suggests the strategies for handling sensitive information and ensuring patient confidentiality taught in the training sufficiently addressed nurse concerns about these issues.

The substantial change we observed in both practice and perceptions of bedside handover cannot be attributed to the communication training alone, given the recognized challenges in changing entrenched handover communication practices (McMurray et al., 2010; Pun et al., 2019). This study's results were likely due to a combination of several factors. First, the design and implementation of the intervention, which integrated communication training into a broader suite of ward‐level recommendations to improve handover, and was tailored to the local organizational, cultural and communicative context (Michie et al., 2011). Second, the ward management's well‐planned and well‐executed implementation plan combined with the NUM’s ward leadership (Waters, 2019) was crucial. Previous studies have emphasized the need for ‘champions’ to achieve and sustain behavioural change in healthcare settings (Bonawitz et al., 2020; Dorvil, 2018; McMurray et al., 2010). The NUM championed change through taking personal responsibility for the intervention's success, setting clear expectations about handover practices, being physically present on the ward and accessible to staff throughout the intervention, and engaging nurses to share responsibility for implementation of the recommendations. Nursing staff met regularly to provide feedback on implementation, discuss barriers to success and be involved in decision‐making, which helped facilitate change in practice. Furthermore, nurses were supported in the transition to bedside handover (Bressan et al., 2019; Waters, 2019) through the ongoing, systematic mentoring and modelling the NUM and Clinical Nurse Educator carried out. This helped actively reinforce and consolidate new practices and created a climate where staff felt empowered to ask questions and raise concerns.

The numerous recent reviews on nursing bedside handover are evidence of the multitude of studies investigating different approaches to nursing bedside handover interventions and their impact on patient safety, patient and staff satisfaction and patient participation (Anderson et al., 2015; Bressan et al., 2019; Dorvil, 2018; Gregory et al., 2014; Mardis et al., 2016; Tobiano et al., 2018). However, it seems that few studies consider the organizational, cultural and linguistic aspects of the local ward context as the basis for a tailored intervention to improve the patient‐centredness of nursing clinical handover. In designing and implementing the project in this integrated way, changing communication in handover practices to focus on enabling patient inclusion and communicating the minimum information content became the impetus for nurses to embrace a ward culture that valued patient‐centred care and patient safety. It seems probable that this will have a positive impact on the sustainability of the intervention and potentially lead to enhanced quality of care and patient safety over time.

4.1. Limitations

Several limitations apply to this study. First, while small in scale and based in a single hospital research site with a sample size of three multidisciplinary team huddles and 19 handover interactions, detailed qualitative analysis of collected ethnographic data provided meaningful and multi‐dimensional insights into the organizational, cultural and communicative challenges with ward handover practices. The small scale ensured that the research team gained an in‐depth understanding of the local ward context, which was critical to effective design and implementation of the intervention (Michie et al., 2011). It also ensured that nursing staff and management could take ownership of the change process and work closely with the research team to implement the recommendations.

Second, the simultaneous implementation of multiple recommendations (Appendix S1) was necessary to address, in a short time frame, the systemic factors in the organizational and cultural context of the ward that impacted on handover delivery and communication; however, this made it difficult to identify which changes were most effective.

Third, even though the short follow‐up period did not allow assessment of the longer‐term sustainability of the intervention, a train‐the‐trainer communication module is being developed and implemented to allow new staff to receive the same communication in nursing clinical handover training. The practice of mentoring new staff in using the ISBAR and CARE protocols in their handover practice will help ensure sustainability.

Fourth, the absence of a comparison group means we did not control for confounding factors that may have influenced the results. The limitations described here seem relatively common among studies aiming to improve handover practices (Mardis et al., 2016, 2017), and suggest the need for funding for research to measure outcomes over the longer term, with larger groups and the possibility of comparisons.

5. CONCLUSION

Adopting a multipronged approach integrating practical communication training into broader ward‐level changes to handover practice tailored to the ward's organizational, cultural and communicative context resulted in sustainable changes to nursing handover practices and the ward culture. The intervention enabled nurses to use the CARE and ISBAR protocols to conduct effective bedside handovers by simultaneously attending to the interactional and informational dimensions of this complex communicative event. By actively involving patients and their colleagues during handover and providing more complete and comprehensive transfer of information, nurses recognized the value of handover practices in terms of reducing patient harm. Integrated approaches to improving communication in nursing handover are likely to be more resource intensive in the short term when compared with standalone communication training as they require committed leadership, staff collaboration and ongoing mentoring to support successful implementation. However, the positive impact to both handover practice and ward culture suggests the potential for achieving more sustainable change. This is an important consideration for hospitals throughout Australia and internationally as they look to implement initiatives to improve handover communication to deliver enhanced patient‐centred care and patient safety.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Laura Chien, Diana Slade, Maria Dahm, Bernadette Brady, Liza Goncharov and Suzanne Eggins declare that they have no conflict of interest. Elizabeth Roberts, Joanne Taylor and Anna Thornton are employees of St Vincent's Health Network Sydney. St Vincent's Curran Foundation, the fundraising group for all St Vincent's hospitals and facilities in New South Wales, provided funding for the study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria (recommended by the ICMJE): (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15110.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research team would like to thank the hospital staff and patients who participated in this study and the hospital administrators who supported the research.

Chien, L. J. , Slade, D. , Dahm, M. R. , Brady, B. , Roberts, E. , Goncharov, L. , Taylor, J. , Eggins, S. , & Thornton, A. (2022). Improving patient‐centred care through a tailored intervention addressing nursing clinical handover communication in its organizational and cultural context. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78, 1413–1430. 10.1111/jan.15110

Funding information

This research was supported by funding from the Geoff and Helen Handbury Foundation and St Vincent's Curran Foundation.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available and cannot be shared due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, J. , Malone, L. , Shanahan, K. , & Manning, J. (2015). Nursing bedside clinical handover: An integrated review of issues and tools. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(5–6), 662–671. 10.1111/jocn.12706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . (2010). OSSIE guide to clinical handover improvement. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our‐work/communicating‐safety/clinical‐handover/ossie‐guide‐clinical‐handover‐improvement [Google Scholar]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . (2012). Safety and quality improvement guide standard 6: Clinical handover (October 2012). ACSQHC. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/Standard6_Oct_2012_WEB.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . (2017). National safety and quality health service standards (2nd ed.). https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019‐04/National‐Safety‐and‐Quality‐Health‐Service‐Standards‐second‐edition.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . (2019a). Action 6.7 (NSQHS standards). https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs‐standards/communicating‐safety‐standard/communication‐clinical‐handover/action‐607 [Google Scholar]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . (2019b). Action 6.8 (NSQHS standards). https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs‐standards/communicating‐safety‐standard/communication‐clinical‐handover/action‐608 [Google Scholar]

- Australian Medical Association . (2006). Safe handover—Safe patients: Guidance on clinical handover for clinicians and managers. https://ama.com.au/sites/default/files/documents/Clinical_Handover_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bakon, S. , Wirihana, L. , Christensen, M. , & Craft, J. (2017). Nursing handovers: An integrative review of the different models and processes available. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 23(2), e12520. 10.1111/ijn.12520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair, W. , & Smith, B. (2012). Nursing documentation: Frameworks and barriers. Contemporary Nurse, 41(2), 160–168. 10.5172/conu.2012.41.2.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz, K. , Wetmore, M. , Heisler, M. , Dalton, V. K. , Damschroder, L. J. , Forman, J. , Allan, K. R. , & Moniz, M. H. (2020). Champions in context: Which attributes matter for change efforts in healthcare? Implementation Science, 15(1), 62. 10.1186/s13012-020-01024-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bressan, V. , Cadorin, L. , Pellegrinet, D. , Bulfone, G. , Stevanin, S. , & Palese, A. (2019). Bedside shift handover implementation quantitative evidence: Findings from a scoping review. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(4), 815–832. 10.1111/jonm.12746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukoh, M. X. , & Siah, C. J. R. (2020). A systematic review on the structured handover interventions between nurses in improving patient safety outcomes. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(3), 744–755. 10.1111/jonm.12936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, K. (2006). JCAHO’S national patient safety goals 2006. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing, 21(1), 6–11. 10.1016/j.jopan.2005.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaboyer, W. , McMurray, A. , & Wallis, M. (2010). Bedside nursing handover: A case study. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16(1), 27–34. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01809.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Excellence Commission . (2017). Safety huddles implementation guide. http://www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/403925/Safety‐Huddle‐Implementation‐Guide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Excellence Commission . (2019). Clinical handover. https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/PD2019_020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. , & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dahm, M. R. , Slade, D. , Brady, B. , Goncharov, L. , & Chien, L. (2022). Tracing interpersonal discursive features in Australian nursing bedside handovers: Approachability features, patient engagement and insights for ESP training and working with internationally trained nurses. English for Specific Purposes, 66, 17–32. 10.1016/j.esp.2021.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Della, P. R. , Aloweni, F. , Ang, S. Y. , Lim, M. L. , Uthaman, T. , Ayre, T. C. , & Zhou, H. (2020). Shift‐to‐shift nursing handovers at a multi‐cultural and multi‐lingual tertiary hospital in Singapore: An observational study. In Watson B. & Krieger J. (Eds.), Expanding horizons in health communication: An Asian perspective (pp. 179–203). Springer. 10.1007/978-981-15-4389-0_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorvil, B. (2018). The secrets to successful nurse bedside shift report implementation and sustainability. Nursing Management, 49(6), 20–25. 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000533770.12758.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drach‐Zahavy, A. , & Shilman, O. (2015). Patients’ participation during a nursing handover: The role of handover characteristics and patients'. Personal Traits, 71(1), 136–147. 10.1111/jan.12477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggins, S. (1994). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics. Pinter Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Eggins, S. , & Slade, D. (2012). Clinical handover as an interactive event: Informational and interactional communication strategies in effective shift‐change handovers. Communication & Medicine, 9(3), 215–227. 10.1558/cam.v9i3.215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggins, S. , & Slade, D. (2016a). Contrasting discourse styles and barriers to patient participation in bedside nursing handovers. Communication & Medicine, 13(1), 71–83. 10.1558/cam.28467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggins, S. , & Slade, D. (2016b). Resource: Communicating effectively in bedside nursing handovers. In Eggins S., Slade D., & Geddes F. (Eds.), Effective communication in clinical handover: From research to practice (pp. 115–125). De Gruyter. 10.1515/9783110379044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eggins, S. , Slade, D. , & Geddes, F. (Eds.). (2016). Effective communication in clinical handover: From research to practice. De Gruyter. 10.1515/9783110379044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garling, P. (2008). Final report of the Special Commission of Inquiry: Acute care services in NSW public hospitals. https://www.dpc.nsw.gov.au/publications/special‐commissions‐of‐inquiry/special‐commission‐of‐inquiry‐into‐acute‐care‐services‐in‐new‐south‐wales‐public‐hospitals/ [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, S. , Tan, D. , Tilrico, M. , Edwardson, N. , & Gamm, L. (2014). Bedside shift reports. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 44(10), 541–545. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M. A. K. , & Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar (3rd ed.). Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission International (2018). Communicating clearly and effectively to patients: How to overcome common communication challenges in health care. https://store.jointcommissioninternational.org/assets/3/7/jci‐wp‐communicating‐clearly‐final_(1).pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, D. , Lu, S. , & McKinlay, L. (2013). Bedside handover enhances completion of nursing care and documentation. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 28(3), 217–225. 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e31828aa6e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manias, E. , Geddes, F. , Watson, B. , Jones, D. , & Della, P. (2015). Perspectives of clinical handover processes: A multi‐site survey across different health professionals. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(1–2), 80–91. 10.1111/jocn.12986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis, M. , Davis, J. , Benningfield, B. , Elliott, C. , Youngstrom, M. , Nelson, B. , Justice, E. M. , & Riesenberg, L. A. (2017). Shift‐to‐shift handoff effects on patient safety and outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Medical Quality, 32(1), 34–42. 10.1177/1062860615612923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis, T. , Mardis, M. , Davis, J. , Justice, E. M. , Holdinsky, S. R. , Donnelly, J. , Ragozine‐Bush, H. , & Riesenberg, L. A. (2016). Bedside shift‐to‐shift handoffs: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 31(1), 54–60. 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays, N. , & Pope, C. (1995). Qualitative research: Observational methods in health care settings. British Medical Journal, 311(6998), 182–184. 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray, A. , Chaboyer, W. , Wallis, M. , & Fetherston, C. (2010). Implementing bedside handover: Strategies for change management. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(17–18), 2580–2589. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03033.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray, A. , Chaboyer, W. , Wallis, M. , Johnson, J. , & Gehrke, T. (2011). Patients’ perspectives of bedside nursing handover. Collegian, 18(1), 19–26. 10.1016/j.colegn.2010.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S. , van Stralen, M. M. , & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6(1), 42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M. , Jürgens, J. , Redaèlli, M. , Klingberg, K. , Hautz, W. E. , & Stock, S. (2018). Impact of the communication and patient hand‐off tool SBAR on patient safety: A systematic review. British Medical Journal Open, 8(8), e022202. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B. C. , Harris, I. B. , Beckman, T. J. , Reed, D. A. , & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]