Abstract

Aim

A follow‐up conversation with bereaved parents is a relatively well‐established intervention in paediatric clinical practice. Yet, the content and value of these conversations remain unclear. This review aims to provide insight into the content of follow‐up conversations between bereaved parents and regular healthcare professionals (HCPs) in paediatrics and how parents and HCPs experience these conversations.

Methods

Systematic literature review using the methods PALETTE and PRISMA. The search was conducted in PubMed and CINAHL on 3 February 2021. The results were extracted and integrated using thematic analysis.

Results

Ten articles were included. This review revealed that follow‐up conversations are built around three key elements: (1) gaining information, (2) receiving emotional support and (3) facilitating parents to provide feedback. In addition, this review showed that the vast majority of parents and HCPs experienced follow‐up conversations as meaningful and beneficial for several reasons.

Conclusion

An understanding of what parents and HCPs value in follow‐up conversations aids HCPs in conducting follow‐up conversations and improves care for bereaved parents by enhancing the HCPs' understanding of parental needs.

Keywords: bereavement, end‐of‐life, follow‐up, paediatrics, parents

Abbreviations

- CCCU

Cardiac Critical Care Unit

- COREQ

COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research

- DSM‐V

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders‐V

- HCP(s)

Healthcare Professional(s)

- ICD‐11

International Classification of Diseases‐11

- NICU

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- PALETTE

Palliative cAre Literature rEview iTeraTive mEthod

- PGD

Prolonged Grief Disorder

- PICU

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses

- WHO

World Health Organization

Key Notes.

During a follow‐up conversation in paediatrics, bereaved parents are in need of information and emotional support, and value being invited to provide feedback to the healthcare professionals (HCPs).

Both parents and HCPs experience follow‐up conversations as valuable and meaningful.

The parents' needs regarding closure and meaning making, and the HCPs' ability to identify parents at risk to develop prolonged grief require further research.

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite advances in paediatrics, some parents still have to cope with the most devastating type of bereavement by losing their child due to premature birth, trauma or a life‐threatening illness. The loss of a child is a dreadful event in the life of parents and may result in psychosocial and health‐related problems up to years after the death of the child. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4

Many parents of deceased children or neonates feel supported by, and appreciate, bereavement care provided by regular healthcare professionals (HCPs). 5 , 6 Over the past years, several bereavement practices and parent‐focused interventions have been developed to assist parents during their child's end‐of‐life and/or after child loss. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Among the various types of bereavement practices and interventions, several follow‐up support services exist, such as follow‐up conversations, sending a condolence letter or sympathy card, making a phone call and sending flowers etcetera. 6 , 8 , 10 The follow‐up conversation, often described as the first scheduled meeting after the death of the child between the parents and the HCPs, is in itself relatively well established as part of bereavement practices in neonatology and paediatrics. Previous studies underline the significance of organising at least one meaningful follow‐up encounter between parents and involved HCPs after the death of a child. 6 , 10 Such an organised follow‐up encounter helps parents feel cared for, reduces their sense of isolation and improves their coping. 6 , 8 , 10 When follow‐up contact is missing, parents may feel abandoned by the HCPs who cared for their child, which can add additional feelings of loss to the already present devastating loss of the child, known as secondary loss. 10

Although follow‐up conversations are mentioned as an important support practice, the goals and content of these conversations are hardy explicated and how parents experience these conversations remains unclear. Also, HCPs lack clear guidelines for conducting meaningful follow‐up conversations. Bereavement care, including conducting follow‐up conversations, is largely practice‐based and a matter of learning on the job that relies on the individual HCP’s opinion, bond with the parents and experience. 11 , 12 , 13 In addition, many HCPs face difficulty conducting follow‐up conversations because they feel uncertain about the effects their actions might have on the parents and keep wondering if the current way of carrying out the follow‐up conversation is actually beneficial for parents.

In order to better align follow‐up conversations to the bereaved parents' needs and to provide HCPs with guidance, this systematic review aims to gain insight into the content of follow‐up conversations and to explore how these conversations are experienced by both, parents and HCPs.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

A systematic review was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA). 14 Since this review is conducted in a relatively young field and terminology addressing follow‐up conversations is diffuse, the Palliative cAre Literature rEview iTeraTive mEthod (PALETTE) was used to establish the literature search. 15 This systematic review was registered in Prospero (registration number: CRD42021241506).

2.2. Databases and searches

Relevant articles that met all inclusion criteria and, as such, should inevitably be part of the systematic review are referred to as golden bullets. According to the PALETTE method, 15 a set of golden bullets was identified from articles suggested by experts in the field of paediatric palliative care, preliminary searches and by back‐ and forward reference checking. From these articles, synonyms around the concepts of ‘follow‐up conversations’ and ‘paediatrics’ were extracted and terminology became more clear, a process known as pearl growing. Subsequently, the search was built around the established terminology supported by an information specialist from the University Medical Library. The search was adjusted and repeated until all golden bullets emerged in the search results. At that point, the search was validated. Lastly, the final literature search was conducted in the databases PubMed and CINAHL. For the full search strings, see Appendix S1.

2.3. Study selection

The included studies were limited to original research articles published in peer‐reviewed English language journals between 1 January 1998 and 3 February 2021. We included 1998 as a starting point because the World Health Organization (WHO) officially defined paediatric palliative care in 1998. From this point on, research in paediatric palliative care had a more focused and well‐defined terminology. Included articles must address the content of follow‐up conversations and/or the experiences of parents and/or HCPs with these conversations. The studies must address a follow‐up conversation defined as the first scheduled meeting between the parents of the deceased child and the HCPs, who have been involved during the child's end‐of‐life. The term ‘parents’ refers to the primary caretakers of the child, which indicates the biological parents, adoptive parents, substitute parents or other guardians. Furthermore, HCPs were defined as all types of regular HCPs who primarily provide care and/or treatment in the field of neonatology or paediatrics. These HCPs encounter bereavement care in their daily practice, yet are not specialised in this type of care. Children were defined as from the age of 0 through 18 years old. Studies that purely focus on prenatal death and stillbirth were excluded, since the field of stillbirth lies more closely to prenatal care and obstetrics, which requires a different kind of support. Furthermore, we excluded studies addressing follow‐up conversations within complex bereavement care. Complex bereavement care is focused on parents who experience a serious disruption in adapting to the loss of their child. Therefore, those follow‐up conversations are mainly performed by specialists in bereavement care.

Articles that emerged from the searches in PubMed and CINAHL were imported into EndNote, where duplicates were removed. The remaining articles were imported into Rayyan, a Web‐based screening tool that facilitated blind title/abstract screening by two researchers independently (MvK, EK). Thereafter, the eligible articles were full‐text screened by the same researchers. Consensus was reached for all articles after deliberation. Lastly, the references of the relevant articles were checked to identify additional articles that met the inclusion criteria.

2.4. Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted using a pre‐designed form. Extracted data consisted of: the country, aim, design, setting of the study, method of data collection, sample, the content of the conversations, experiences of parents and experiences of HCPs. The data regarding the content of the follow‐up conversations and parents' and HCPs’ experiences were then analysed using a thematic analysis approach. The data from the three main predefined categories (content, parent experience and HCP experience) were categorised in subthemes, reflected in the different paragraphs of the results section.

Each article underwent a quality assessment that was performed by two researchers independently (MvK, EK). Qualitative studies were assessed using the Consolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ), recommended by Cochrane Netherlands. 16 The COREQ consists of 32 items covering the following three domains: research team and reflexivity, study design, and analysis and findings. Items could be scored with 0 points when not reported in the articles, 0.5 points when partly described, and 1 point when fully reported. Quality appraisal did not affect inclusion of the article in the systematic review due to its descriptive nature. 17

3. RESULTS

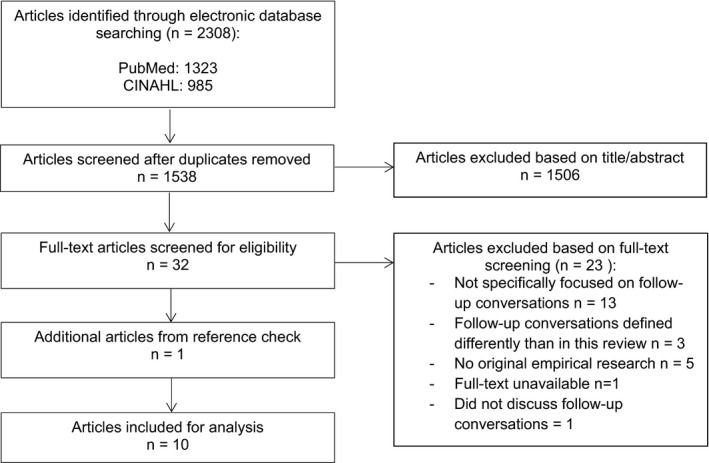

The search generated 1538 individual articles, of which nine met the inclusion criteria 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 and one was added following an additional reference check 27 (for full study flow, see Figure 1). All included articles represented qualitative studies. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 Two articles were unclear in research design, and they were assessed as qualitative studies based on the methods of data collection and data analysis: using video‐recordings 24 and a thematic analysis. 26 An overview of the included articles and their baseline characteristics is provided in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow literature search and selection

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics

|

Author Year Country |

Aim of the study |

Study design Method of data collection |

Setting |

Sample Deceased subjects |

Content of the conversations |

Parents' experiences |

HCPs' experiences |

Quality appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brink et al. (2017) DK |

To identify parents’ experience of a follow‐up meeting and to explore whether it was adequate to meet the needs of parents for a follow‐up after their child's death in the PICU. |

Generic qualitative study. Semi‐structured interviews 2—12 weeks after the follow‐up conversation. |

University Hospital, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) |

Parents (n = 10) attending a follow‐up meeting 4–8 weeks after the death of their child Children (n=6) who died in the PICU with a variety of causes of death |

‐ Information: Discuss various topics and, provide answers, give a causal explanation after a unexpected death. ‐ Emotional support: Discuss how parents are dealing/coping, staff showing emotions. ‐ Feedback: Parents want to provide feedback in order to improve practice. |

‐ Nervousness and tension before but all pleased to have participated. Opportunity to enhance grieving process. ‐Emotional involvement from HCP’s enables better coping. ‐ Closure of the course in the PICU. Helps to find encouragement to grieve. ‐Meaningful that the meeting was interdisciplinary; attention for treatment and care ‐ Experienced no time pressure ‐ Important that HCPs involved in the meeting were those who had been present through hospitalisation and the time of the child's dead since this felt safe for them. ‐ Regarding location: stressful to return, helpful to revisit, felt as a ‘second home'. Mostly willing to return to the hospital |

21 out of 32 | |

|

Eggly et al. (2011) USA |

To describe the development of a framework to assist paediatric intensive care unit physicians in conducting follow‐up meetings with parents after their child's death. . |

Generic qualitative study. Telephone interviews 3–12 months after the death of a child |

Seven academic tertiary care children's hospitals participating in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN), Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) |

A framework for follow‐up meetings based on the experience/perspectives of parents (n = 56) of children who died in an CPCCRN PICU and PICU attendings and fellows (n = 70) practising or training at a CPCCRN site Children (n=48) who died in a CPCCRN affiliated PICU. |

‐ The framework is a general set of principles adaptable to the specific context of each family's circumstances. ‐ Balance of different aspects based on the parents’ needs. ‐ Opportunity for parents to express their thoughts and feelings and identify their issues. ‐ Gaining information: Chronological course of the illness and provided treatment, the last hours of life and risks for the surviving children should be discussed using understandable terminology. ‐ Assess how parents are coping so professional referrals can be made. ‐ Parents need to gain reassurance that both the family and the medical team did everything they could to prevent the child's death. ‐ Parents want an opportunity to provide feedback regarding the care. ‐Meetings should be multidisciplinary so varying needs can be addressed. ‐ Meetings should be with the HCPs who cared for the child. |

‐Felt the meetings were beneficial to parents and to themselves. ‐ Benefits for them: a better understanding of parents’ perspectives, an opportunity to increase skill and experience to assist future families, a chance to reconnect with families and find out how they are coping, an opportunity to reach closure and professional gratification. ‐ Benefits may seem trivial, but may serve to counteract burnout and compassion fatigue. |

11 out of 32 | |

|

Eggly et al. (2013) USA |

To examine physicians conceptualisation of closure as a benefit of follow‐up meetings with bereaved parents |

Generic qualitative study. Semi‐structured telephone interviews. |

Seven academic tertiary care children's hospitals participating in the CPCCRN, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) |

Paediatric critical care physicians and fellows (n = 67) practising or training at a CPCCRN clinical centre and conducting follow‐up meetings with bereaved parents. Children who died in a CPCCRN affiliated PICU. |

HCPs and parents should: ‐ Review details of the death ‐ Discuss new information ‐ Address new or lingering questions |

Parents can move towards closure by: ‐ Gaining a better understanding of the causes and circumstances of the child's death ‐ Considering the child's end‐of‐life in retrospect ‐ Reconnecting or resolving relationships with HCPs. ‐ Gaining reassurance that HCPs did everything possible relieves parental quilt and increases trust in the medical team ‐ Providing feedback; allows them to contribute their experiences as information that would ultimately improve care for others ‐ Moving on and accepting the reality of dead; the follow‐up meeting is a point in time from which parents can move on. |

‐ Some HCPs feel the word ‘closure’ does not accurately reflect the concept they want to describe. HCPs can move towards closure by: ‐ Reconnecting with families; Want to see how parents are coping. ‐ Further exploring the causes and circumstances of the death ‐ Fulfilling professional duty; their work is not complete until they provide parents with final explanations. . |

19,5 out of 32 |

|

Granek et al. (2015) CA |

To examine follow‐up practices employed by paediatric oncologists after patient death. |

Generic qualitative study. Interviews |

Two paediatric hospitals, Pediatric Oncology Department |

Paediatric oncologists (n = 21) conducting follow‐up practices with bereaved families. Children who died from cancer. |

‐ Parents and HCPs can talk about what had happened. ‐ Parents can ask any lingering questions. ‐ Parents want to hear that everything possible was carried out for their child. |

‐ The follow‐up meetings can be a beginning of the process of slowly disconnecting from the HCPs that were a major part of their lives for so long and who they may have felt close to. |

16,5 out of 32 |

|

|

McHaffie et al. (2001) SCO |

To explore parents’ experiences of bereavement care after withdrawal of newborn intensive care |

Generic qualitative study. Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews |

Three neonatal referral centres, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) |

Parents (n=108) attending a follow‐up appointment after newborn intensive care was withhold/ withdrawn. Neonates/infants (n = 62) who died after treatment withholding / withdrawing in newborn intensive care. |

Full frank information: ‐ Should be given sensitively so parents can build a clear picture of what happened and assess their future risks. ‐ Should answer parents’ questions. ‐ Should be understandable for parents in order to learn and accept the facts. ‐ Reassurance about what had been done, the decision and future risks needs to be given where possible, but no false reassurance. ‐ Sharing memories and experiences is important for emotional support. ‐Care and respect for the whole family is ensured. |

‐ Wanting to find out how the parents are coping is of great value. ‐ Showing compassion and understanding, communicating effectively and demonstrating a personal interest was appreciated. ‐ Multidisciplinary is important because it is a burden to go to multiple separate follow‐up appointments. ‐ Appreciated an unhurried approach. ‐ Should be with the neonatologist who had cared for the baby before the death. ‐ Prefer to be seen soon after the death. Early contact is desirable since parents want to piece together a coherent picture in order to make progress in their grieving, to assess the risks of recurrence or the genetic implications and to contemplate another pregnancy. ‐ Revisiting the hospital can be painful. |

‐ Barriers in conducting follow‐up conversations can be: workload, resources, availability of support from colleagues. | 12 out of 32 |

|

Meert et al. (2007) USA |

To investigate parents’ perspectives on the desirability, content, and conditions of a physician‐parent conference after their child's death in the PICU |

Generic qualitative study. Audio‐recorded telephone interviews 3–12 months after the death of a child. |

Seven academic tertiary care children's hospitals in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development CPCCRN PICU |

Parents (n = 56) attending a physician‐parent conference after their child's death in a CPCCRN affiliated PICU. Children (n = 48) who died in a CPCCRN affiliated PICU. |

Parents should: ‐ Gain information about their child's illness and death. Topics: chronology of events, cause of death, treatment, autopsy, genetic risk and steps towards prevention, medical documents, withdrawal of life support, ways to help others, bereavement support and what to tell family. ‐ Be able to seek emotional support. Reassurance they did everything they could. Sense that HCPs still care about them. ‐ Be able to voice complaints, provide feedback and express gratitude. Improve care for other families. |

The most important component is the provision of information. ‐ Difficult to comprehend information at the time of the child's demise. ‐ Highest in importance related to treatment and cause of death. ‐ Review of the sequence of events to make sense of what happened. ‐ Medical records and autopsy reports can increase the understanding. ‐ Appreciate the follow‐up meeting being with the HCPs who had close relationships with their child. ‐ The majority is willing to return to the hospital and want to meet within the first three months. ‐ Early enough to have any benefit, not too soon cause parents need to be able to comprehend was is being said. Some wanted to meet earlier, others wanted to wait until the distress of acute grief had begun to subside. |

20 out of 32 |

|

|

Meert et al. (2011) USA |

To investigate critical care physicians experiences and perspectives regarding follow‐up meetings with parents after a child's death in the PICU |

Generic qualitative study. Semi‐structured, audio‐recorded telephone interviews. |

Seven academic tertiary care children's hospitals in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development CCCRN, PICU. |

Critical care physicians (n = 70) practising or training at a CPCCRN clinical centre. Children who died in a CPCCRN affiliated PICU. |

Elements of the meetings: ‐ Providing information (past and new information available) ‐ Emotional support (family coping, providing reassurance and expressing condolences) ‐ Receiving feedback ‐ Informational topics included: autopsy, questions, hospital course, cause of death, genetic risk, bereavement services, and legal or administrative issues. ‐ Discuss whatever the family wants to discuss |

‐ Desire a follow‐up meeting with the HCP(s) who cared for their child. ‐ Benefits of the meetings included: an opportunity to ask questions and gain information, closure, reassurance, reconnection with staff, talk through feelings, professional referrals and greater trust in the healthcare team. |

‐ Majority perceived that follow‐up meetings were beneficial to parents and themselves. ‐ Some report no benefit for themselves, the follow‐up meetings just allows them to fulfil their professional obligations to parents. ‐ The same HCPs desire to consider the meetings on a ‘case‐by‐case’ basis because there is a need for emotional protection. ‐ Benefits included: understanding of parents’ perspectives, opportunity to increase skill and experience assisting families, reassurance, reconnection with families, closure and professional gratification. ‐ Barriers included time and scheduling, parents and physician unwillingness, distance and transportation, language and cultural issues, parents’ anger and lack of a system for meeting initiation and planning. ‐ Logistic barriers can be overcome. Personal barriers are more prohibitive. ‐ The majority participated in follow‐up meetings that were located at the hospital and occurred within 3 months after death. ‐ Need for flexibility in timing: meet when families are ready and autopsy results are available. |

.18 out of 32 |

|

Meert et al. (2014) USA |

To evaluate the feasibility and perceived benefits of conducting physician‐parent follow‐up meetings after a child's death in the PICU according to a framework developed by the CPCCRN |

Observational study. Video‐recorded follow‐up meetings using the CPCCRN framework and evaluation surveys completed by parents and critical care physicians. |

Seven academic tertiary care children's hospitals in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development CPCCRN, PICU |

Follow‐ up meetings (n = 36). between bereaved parents (n = 50) and critical care physicians (n = 36). Children (n = 194) who died in a CPCCRN affiliated PICU. |

‐ Most parents find the meeting helpful and think it will help them cope in the future. ‐ The following aspects are the most helpful: The opportunity to gain information, receive emotional support, provide feedback, honest, unhurried and nonthreatening style of communication. ‐ Most parents could understand the information. |

‐ Were willing to be trained to use the structured CPCCRN follow‐up meeting framework. ‐ The majority thinks that the meeting is beneficial to parents and to themselves. ‐ HCPs benefited by: reconnecting with parents, gaining a deeper understanding of parents’ perspectives and achieving a sense of closure ‐ Most of the HCPs find the framework easy to use |

23,5 out of 32 . |

|

|

Meert et al. (2015) USA |

To identify and describe types of meaning‐making processes that occur among parents during bereavement meetings with their child's intensive care physician after their child's death in a PICU |

Secondary data analysis of an observational study, Video‐recorded follow‐up meetings using the CPCCRN framework. |

Seven academic tertiary care children's hospitals in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development CPCCRN, PICU. |

Follow‐up meetings (n = 35) between bereaved parents (n = 53). Children (n = 35) who died in a CPCCRN affiliated PICU. |

Four major meaning‐making processes were identified: 1. Sense making: Seeking biomedical explanations, revisiting prior decisions and roles, and assigning blame. Explain why they made the decisions they did, and sought reassurance from HCPs that the best decisions had been made 2. Benefit finding: Exploring positive consequences of the death, including ways to help others, such as giving feedback to the hospital, making donations, participating in research, volunteering and contributing to new medical knowledge and donating organs. 3. Continuing bonds: Parents’ ongoing connection with the deceased child manifested by reminiscing about the child. Parents recalled actions of HCPs that showed dignity and respect for the child. 4. Identity reconstruction: Changes in parents’ sense of self, including changes in relationships, work, home and leisure. |

‐ May facilitate meaning‐making processes by providing information, emotional support and an opportunity for feedback. | 22 out of 32 | |

|

Midson et al. (2010) UK |

To explore the experiences of parents with end‐of‐life care issues in a tertiary treatment centre. |

Generic qualitative study. A survey about parents’ experiences during an interview. |

A tertiary treatment hospital, PICU +Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), Cardiac Critical Care Unit (CCCU) and other wards |

Parents (n = 28 families) attending a follow‐up visit after the death of their child. Children between 3 days and 17 years old who died in a tertiary treatment centre |

‐ Some found that the follow‐up visit was helpful in explaining and answering questions. ‐ Other parents were left with unanswered questions and felt frustrated if further research did not answer their questions. ‐ Other parents felt that the follow‐up conversations made them re‐live the whole experience and left them with a lot of questions. ‐ Some parents were not ready for the follow‐up meeting but kept the contact details for later. |

16,5 out of 32 |

Eight studies addressed follow‐up conversations in the field of paediatrics. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 Of these, seven studies focused on the Pediatric Intensive Care (PICU) 18 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 and one focused on paediatric oncology. 21 One study addressed follow‐up conversations in the field of neonatology, concentrating on the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). 27 One study addressed follow‐up conversations in the field of both paediatrics and neonatology, consisting of the PICU, the Cardiac Critical Care Unit (CCCU) and several other paediatric wards. 26 Five studies brought out the perspective of the parents, 18 , 22 , 25 , 26 , 27 three studies the perspective of the HCPs, 20 , 21 , 23 and two studies the perspectives of both the parents and the HCPs. 19 , 24 Seven of the studies provided insight into the content of follow‐up conversations based on interviews with both the parents and the HCPs. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 27 Hereafter, an overview will be provided on firstly the content of follow‐up conversations, secondly the experiences of parents regarding these conversations and lastly the experiences of HCPs with the conversations.

3.1. The content of follow‐up conversations

The preferable content of the follow‐up conversation is built around three key elements: (I) Gaining information, (II) Receiving emotional support and (III) Facilitating parents to provide feedback. These three key elements were described from both the perspectives of the parents and the HCPs (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary of the content of follow‐up conversations

| The content of follow‐up conversations |

| 1. Gaining information: |

| A description all the proceedings during the child's illness and death. |

| An answer/solution to the lingering questions/concerns parents may still have. |

| 2. Receiving emotional support: |

| Parents want to feel that the HCPs care about them and their deceased child. |

| The HCPs should ask the parents how they are coping with the loss. |

| Parents want to gain the reassurance that they did everything that they could and made the right decisions. |

| 3. Facilitating parents to provide feedback |

| Parents want to provide feedback on aspects of the care that need to be improved. |

| Parents also want to express their appreciation and gratitude for the care they received. |

3.1.1. Gaining information

The majority of the articles showed that gaining information encompassed an opportunity for parents to gain an understanding of all the events surrounding the child's end‐of‐life and to ask remaining or new emerging questions. According to the parents, the information should be provided in an understandable manner. 24

Gaining an understanding of all the events surrounding the child's death is important since parents described that the intense emotions they experienced during their child's end‐of‐life and surrounding their death, inhibited their ability to accurately and efficiently process information, and to comprehend information provided at that time. 22 Therefore, during the follow‐up conversation parents found it crucial to be provided with a clear and detailed overview of all the occurred events to build up a cohesive picture of what exactly happened, which facilitated acceptance and moving forward in their lives. 18 , 24 , 27 It was mentioned that the description of the proceeded events must at least include the chronological course of the child's illness, the provided treatment, the cause of death and the genetic risk to other children/family members. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 27 Besides addressing previously known information, parents and HCPs emphasised the importance of disclosing all new information that became available since the death of the child. 18 , 20 , 23 New information mainly consisted of the autopsy results, 22 , 23 which posed an additional source of information that increased the parents understanding of the child's treatment and cause of death. 22

In many articles, it was mentioned that parents and HCPs found it important that parents get an opportunity to address their new or lingering questions and concerns during the follow‐up conversation. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 27 According to the parents and HCPs, these questions or concerns should be resolved during the follow‐up conversation in order to prevent parents from delaying their process of grief. 18 , 19 , 27 Addressing the questions or concerns that parents may have provided an opportunity to talk about their thoughts and feelings. 19 In one article, it was mentioned that allowing parents to speak and be heard at the follow‐up conversation increased parents' satisfaction and reduces possible conflict with HCPs. 22

3.1.2. Receiving emotional support

Parents and HCPs described the second key element that should be part of follow‐up conversations as receiving emotional support. Receiving emotional support consisted of feeling cared for by HCPs, attention for parents' everyday life and their coping, and reassurance. Overall parents considered emotional support from HCPs important since it enabled them to cope with the loss of their child and gave them some sort of comfort. 18 , 27

Firstly, parents stressed that they want to feel cared for and respected by the HCPs, and not be abandoned by them. 22 , 25 , 27 HCPs could perform multiple acts that contributed to parents feeling cared for, such as starting the follow‐up conversation by expressing their condolences to the parents, 20 , 24 sharing memories and experiences of the deceased child 28 and carrying out actions that demonstrated dignity and respect for the deceased child. 25 , 28

Secondly, several articles mentioned that receiving emotional support included asking the parents how they deal with everyday life and how they cope with the loss after their child's death. 18 , 19 , 23 The response of parents to the death of their child must be critically appraised by the HCP, since signs of complicated grief may be present. An unusual absent or excessive reaction could indicate that parents need further professional help and the HCP could refer parents to a specialist in the field of bereavement. 19

Lastly, both the parents and the HCPs often mentioned that an important part of emotional support is providing reassurance. 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 27 Multiple studies addressed that parents sought reassurance from the HCP on several facets. They wanted to hear that HCPs did everything they could to prevent the child's death. Moreover, parents often felt guilty and wanted to be reassured that the child's death was not a result of their actions, that they had made the right decisions, they had done everything they could do and they were not to blame for the child's death. 19 , 22 , 25 , 27 One article mentioned that gaining reassurance on these aspects relieved parental guilt and increased their trust in the decisions made by the medical team. 20

3.1.3. Facilitating parents to provide feedback

The majority of the articles emphasised the importance of facilitating parents to provide feedback on the care their child received. 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 25 From the parents' perspective, it was learned that parents wanted to provide feedback on aspects of the care that needed to be improved. Parents often felt the need for something positive to result from their experience by a means of ultimately preventing other families from experiencing similar problems as they did while losing a child. 20 , 22 , 25 Several articles mentioned that besides the constructive feedback, parents often wanted to express their appreciation and gratitude for the care they received from the HCPs. 18 , 22 , 25

3.1.4. The importance of tailoring the conversation to the parents' needs

One article highlighted that the three key elements that illustrated the content of a follow‐up conversations were applicable to all situations. However, these key elements always needed to be tailored to the specific circumstances of each family. 19 Different situations may raise different kinds of concerns and questions for parents. For example, parents feel a greater need for a causal explanation when their child died sudden and unexpected. 18

3.2. The experiences of parents with follow‐up conversations

The vast majority of the parents experienced the follow‐up conversation after the death of their child as meaningful and helpful. 18 , 19 , 23 , 24 , 26 Nearly all parents felt nervous and tense prior to the conversation but afterwards were pleased to have participated. 18 Firstly, we will describe the positive experiences of parents with follow‐up conversations, secondly the negative experiences and lastly the location and timing of the follow‐up conversation about which disunity prevailed among parents.

3.2.1. Positive experiences with the follow‐up conversation

The parents with an overall positive experience pinpointed one particular benefit that they gained from attending the follow‐up conversation: moving towards closure. 18 , 20 , 23 Parents stated that the follow‐up conversation facilitated a definitive closure of the course in the hospital which helped them in moving closer towards accepting the reality of the death, finding encouragement to grieve, coming to terms with the loss and moving forward in their grieving process. 18 , 24 Experiences during the follow‐up conversations that contributed to the concept of closure were acquiring a better understanding of the causes and circumstances surrounding the child's death, 26 considering the child's end‐of‐life in retrospect, momentarily reconnecting with the HCPs, gaining reassurance and providing feedback. 18 , 20 One article mentioned that parents who went through a protracted time of illness before the child's death, as is often the case in oncology, experienced the follow‐up conversation to contribute to the process of slowly disconnecting from the HCPs. Since the HCPs had been a major part of parents' lives for a long time, slowly letting go of the constant presence and support of the HCPs further facilitated closure. 21

Besides the particular benefit of gaining closure, multiple articles showed a number of practical aspects of the follow‐up conversation that the majority of parents evaluated as positive: the interdisciplinarity, the absence of time pressure and the presence of the HCPs who had cared for the child during the end‐of‐life. 18 , 20 , 22 , 27

Interdisciplinarity is defined as the presence of different types of HCPs, for example physicians, nurses and (para‐)medics. It was shown that the interdisciplinarity during the follow‐up conversation was appreciated by the parents since questions about both the treatment provided by the physicians and the bedside care conducted by the nurses can be answered. Parents experienced the presence of the nurses as pleasant since most nurses possessed the ability to approach the parents with adequate tenderness and empathy. 18 , 27 Interdisciplinarity in the field of neonatology encompassed the presence of different specialties such as obstetrics. Parents were grateful for this sort of interdisciplinarity because it relieved the burden of attending separate follow‐up conversations of each individual specialty. 27

The absence of time pressure was experienced by parents through the unhurried approach during the follow‐up conversation. Parents experienced no time pressure despite the predetermined time frame that most of the follow‐up conversations do have. 18 , 27

Attendance of the HCPs who had been present through hospitalisation and the time of the child's death was important for parents. 18 , 20 , 22 , 27 Parents often had an intimate and intense relationship with these HCPs and felt safe discussing their emotions and feelings with them. 18 , 20 Their absence during the follow‐up conversation could feel as an abandonment.

3.2.2. Negative experiences with the follow‐up conversation

Despite the positive experiences, some parents did not benefit from the follow‐up conversation. A few parents were left with unanswered questions after the visit which made them feel frustrated. Other parents re‐lived traumatic experiences during the conversation without resolving the aspects that firstly caused the trauma. 26

3.2.3. Experiences with the location and timing of the conversation

Disunity prevailed among parents regarding the location and timing of the follow‐up conversation. Regarding the location of the follow‐up conversation, some parents found it stressful, painful and traumatic to return to the hospital, 18 , 27 while a large group of parents experienced no problems returning. 18 , 22 , 27 For some parents, revisiting the hospital is even helpful because it had felt like a second home for a long time. 18

Parents’ opinions on the preferred timing for the follow‐up conversation differed, which may be related to a difference in paediatrics versus neonatology. One article stated that the majority of parents would like to meet with the HCPs within the first three months after the death of their child. 22 This period provided parents with enough time to let the acute feelings of distress and despair subside, while still being soon enough after the child's death to gain benefit from of the follow‐up conversation. 22 However, other articles emphasised that in particular parents of deceased neonates preferred to meet the HCPs sooner than three months after the child's death since they often wanted to assess the risks of recurrence, to discuss the genetic implications and to contemplate a subsequent pregnancy. 22 , 27 In another article, it was suggested that it is wise to have some sort of flexibility in the timing for the meeting, so it can take place whenever the parents are ready. 23

3.3. The experiences of HCPs with follow‐up conversations

From the HCPs' perspective, it was learned that the vast majority believed that follow‐up conversations were not only beneficial for the parents but also for themselves. 19 , 23 , 24 Hereafter, the benefits HCPs gained from follow‐up conversation and barriers towards the conversation are discussed.

3.3.1. Benefits gained from the follow‐up conversation

The benefits HCPs gained from the follow‐up conversations included learning from parents, reconnecting with parents and gaining closure. 19 , 20 , 23 , 24

Regarding learning from parents, HCPs stated that they gained a deeper understanding of the parents' perspectives during the follow‐up conversations. HCPs mentioned that they took the parents' perspectives and feedback into account to reflect on the consequences their actions had on them. These insights facilitated HCPs to improve their future practice and increased their skill and experience to assist future families under their care. 19 , 20 , 23 , 24

Concerning reconnecting, HCPs mentioned that caring for a child and their parents had often been intimate and intense. An abrupt end to their relationship with the parents directly after the child had passed away, felt unsettling to the HCPs because they wanted to keep an eye on parents. HCPs considered it beneficial to reconnect with parents during the follow‐up conversation and find out how they were coping. 19 , 20 , 23 , 24

HCPs mentioned that in conducting follow‐up conversations, they fulfilled their professional duties, obtained professional gratification and thereby gained closure for each deceased child they cared for. 19 , 20 , 23 , 24 Most HCPs described follow‐up conversations as part of their jobs and felt like their work was not complete until they had provided parents with final explanations.

The previously stated benefits may seem minor but may serve to prevent burnout and compassion fatigue in HCPs. 19

3.3.2. Barriers to follow‐up conversations

Besides the benefits HCPs gained by conducting follow‐up conversations, two articles also identified multiple barriers that made conducting follow‐up conversations more difficult for HCPs. These barriers can be divided into different categories, namely emotional and practical barriers for the HCPs, emotional and practical barriers for the parents seen from the HCPs perspective, and a systemic barrier.

Emotional and practical barriers for the HCPs, included HCPs unwillingness, time and scheduling. HCPs' unwillingness can be based on existing emotional discomfort. The emotional barrier and discomfort arose from the fact that conducting a follow‐up conversation can remove a form of self‐protection for HCPs. Some HCPs wanted to put the death of the child aside after a while to protect themselves from feeling overwhelmed and emotionally exhausted. Yet, conducting follow‐up conversations repeatedly confronted them with intense and overwhelming situations. These confrontations can increase the risk of burnout and compassion fatigue. 23 HCPs that experienced this level of discomfort with the conversation did not find any personal benefit in conducting follow‐up conversations and tried to sustain their emotional stability by not meeting with parents. 23 The practical barriers for HCPs consisted of busy clinical days, a high work load and conflicting schedules. These aspects made it harder for the HCPs to schedule follow‐up conversations and to spend as much time as the family needed. 23 , 27

Emotional and practical barriers for the parents seen from the HCPs perspective included parents' unwillingness and parents' anger or distrust, distance and transportation, language and cultural issues. Distance and transportation formed a barrier because some parents needed to travel a long distance. 23 Language created an issue when there needed to be a translator present to be able to conduct the follow‐up conversation with non‐English speaking parents. 23

A lack of a system for conversation initiation and planning formed an additional barrier for HCPs. The HCPs had faith in overcoming the practical barriers with a little bit of effort. However, the personal and emotional barriers were viewed as more limiting. 23

4. DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, the content of follow‐up conversations after the death of a child and an overview on how these conversations are experienced by parents and HCPs is described. Follow‐up conversations are built around three key elements: (1) gaining information, (2) receiving emotional support and (3) facilitating parents to provide feedback. The vast majority of parents experienced the follow‐up conversation as meaningful and helpful in their grieving process. One particular benefit parents gained was moving towards a definite closure of the course in the hospital. Furthermore, parents perceived the interdisciplinarity, the absence of time pressure and the continuation of the bond with HCPs as strengths of the follow‐up conversations. The vast majority of HCPs believed that the follow‐up conversations they had conducted were beneficial to them. The benefits HCPs derived from conducting follow‐up conversations included learning from the parents, reconnecting with the parents and gaining a sense of closure from the deceased child they have cared for. HCPs identified the following barriers in conducting follow‐up conversations: finding time and scheduling, parents' and HCPs' unwillingness, distance and transportation, language and cultural issues, parents' anger or distrust, and a lack of a system for conversation initiation and planning.

After the death of a child, parents' lives and their view on the world and themselves are largely disrupted. In order to adjust to their new reality in which their child is physically absent, parents need to incorporate the loss into their autobiographical memory, for example adjust how they view themselves and the ongoing bond with their child. 6 , 28 , 29 To incorporate the loss, parents need a fitting picture of all the events that lead to the death of their child. 6 In particular, HCPs involved in childcare can aid parents in gaining a full understanding of the proceedings surrounding the death, which is acknowledged as an important element of the follow‐up conversation by both parents as well as HCPs. 18 , 22 , 27 Sense making, creating such a comprehensive picture, is a component of meaning making. 30 , 31 Meaning making is known as an important element required to make such an adjustment after child loss 31 , 32 and aids parents in coming to terms with the loss, in which parents might find comfort and reassurance. 32 The inability to ‘make sense’ of the of the situation is known to enhance grief intensity in parents. 33

Another parental need this systematic review puts forward is that parents seek reassurance on having been ‘a good parent’ during the end‐of‐life and whether they have made the right decisions. What is perceived as being ‘a good parent’ differs per individual, yet a common theme consists of having done right to the child, including in health‐related decisions. 34 , 35 , 36 Additionally, parents need reassurance on having made the right decisions, 37 and on the fact that HCPs did everything they could and no mistakes were made. 38

Most of the time, these two goals, the desire to gain a comprehensive picture of the events and the search for reassurance regarding parenthood and decision‐making, will complement each other. Yet what if the full picture enhances doubts or creates new uncertainties? In that case, the follow‐up conversation may have an adverse effect on parents and increase feelings of guilt, which has a negative impact on parental readjustment. 39 Moreover, guilt in bereavement may have severe impact on parents’ psychological and physical health and general well‐being. 40 Hence, the balance between providing an honest and accurate picture on the one hand and reassurance on the other is a delicate subject for HCPs. Future studies should focus on how to address and uphold this balance in follow‐up conversations.

A goal HCPs brought up regarding the follow‐up conversation is to assess whether parents require additional support. Over time, most parents will be able to cope with child loss, yet about 10%–25% of bereaved parents develop complicated grief or ‘prolonged grief disorder’ (PGD). 41 , 42 , 43 PGD is an disorder listed in the DSM‐V and ICD‐11 manual, and known as a serious and longitudinal disruption in the grieving process, for which additional guidance by a mental healthcare specialist is required. 41 , 44 The follow‐up conversation could be a fitting time to assess which parents might be at risk to prevent further disruption, since parents who lost a child are known as a high‐risk group to develop PGD. 41 , 42 , 43 , 45 An overview of indicators to identify these parents is currently lacking. Future research could focus on identifying indicators and predictors of PGD in bereaved parents.

Based on the insights provided in this review, various suggestions for clinical practice can be made in order to improve follow‐up conversations in neonatology and paediatrics. An important note is that all these suggestions should be incorporated while arranging and conducting the follow‐up conversations, but always tailored to the specific circumstances of each family.

The first suggestion is that HCPs should first and foremost explore the parents' concerns, fears, doubts and needs for more information, not only regarding the illness trajectory and decision‐making, but also regarding their parenting during the end‐of‐life.

The second suggestion is that HCPs should facilitate parents' making meaning of their experiences with losing their child by offering the opportunity to provide feedback on the care received. By providing feedback on aspects of care that parents have experienced as non‐pleasant, they can prevent other parents from encountering the same problems in the future. Providing feedback is helpful for parents since they often want something meaningful to arise from their child's death and being of meaning to other parents.

The third suggestion is that follow‐up conversations should be conducted interdisciplinary, including the HCPs who have been involved in the child's end‐of‐life care and without time pressure. This enhances the opportunity for parents to ask questions, provide feedback and reflect on their parenting and the uniqueness of their child.

Furthermore, this review uncovered that the difficulties HCPs face while conducting follow‐up conversations are unlikely to be solved by just drawing up a guideline based on the previous given suggestions. Multiple studies included in this review point out that some HCPs can experience discomfort discussing death and bereavement related issues with parents due to a lack of (communication) training and inexperience. 19 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 24 Removing the barrier of discomfort may contribute in facilitating HCPs in carrying out follow‐up conversations. Additionally, other studies underline the lack of structured training on bereavement care for medical and nursing staff. 13 , 46 , 47 , 48 Therefore, the final and last suggestion for clinical practice is to provide structured training and education for HCPs, including coaching, skills training and learning on the job. Besides focusing on follow‐up conversations in training, broader attention should be provided on maintaining their emotional balance while providing bereavement care, which is emotionally challenging. The educational forms should be focused on important aspects such as theories on grief, the psychological processes of bereavement and communications skills. 19 , 20 , 21 , 26 , 49

This review has several strengths including gaining insight into the content of follow‐up conversations and both the parents and the HCPs perspectives, providing the reader with a robust description of the available knowledge regarding follow‐up conversations from the perspectives of all persons involved. In addition, the parents' and HCPs' experiences are separately presented, thereby resulting in more clarity on differences and similarities between their perceptions. Another strength is the inclusion of studies from different subspecialisms and departments within paediatric and neonatal medicine. Both the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) and the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), and paediatric oncology were addressed in this review. Therefore, the results are applicable to a variety of situations, enhancing transferability and possibilities for uptake in clinical practice. A limitation could be that no studies solely included follow‐up conversations with parents of children with chronic diseases and disabilities with a slow deterioration. These children often have long hospitalisation on the children's ward and at home. These circumstances are likely to affect the content of a follow‐up conversation. Another limitation could be that six of the included articles are conducted by the same research group, although the separate studies rely on rather large samples and a variety of data sources including parents, HCPs, and video or audio recordings of follow‐up conversations. Yet, less diversity in our results may occur than is actually the case in current practice.

In conclusion, this systematic review provides insight into the content of follow‐up conversations in paediatrics and the experiences of parents and HCPs with these conversations. These insights contribute to a better alignment to the needs of bereaved parents. Future research should explore the parental position towards closure and towards identifying parents that might be at risk for complicated grief. In addition, a better understanding of how to balance providing reassurance versus providing a realistic and complete picture of the events surrounding the child's death is needed to align to parental needs. Lastly, studies on how to optimally support HCPs in conducting follow‐up conversations should be performed and practical tools to support HCPs should be developed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Paulien Wiersma for sharing her expertise as an information specialist, in constructing the search string.

Biographies

Merel M. van Kempen

Eline M. Kochen

Marijke C.Kars

van Kempen MM, Kochen EM, Kars MC. Insight into the content of and experiences with follow‐up conversations with bereaved parents in paediatrics: A systematic review. Acta Paediatr. 2022;111:716–732. doi: 10.1111/apa.16248

Funding information

This publication is part of the emBRACE study (EMbedded BeReAvement Care in paEdiatrics), supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development [grant number 844001506]. The funding party did not take part in the conception and design, data collection and analysis, neither in drafting or revising the manuscript

REFERENCES

- 1. Pohlkamp L, Kreicbergs U, Sveen J. Bereaved mothers’ and fathers’ prolonged grief and psychological health 1 to 5 years after loss—a nationwide study. Psychooncology. 2019;28(7):1530‐1536. 10.1002/pon.5112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosenberg AR, Baker KS, Syrjala K, Wolfe J. Systematic review of psychosocial morbidities among bereaved parents of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:503‐512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Valdimarsdóttir UA, Lu D, Lund SH, et al. The mother’s risk of premature death after child loss across two centuries. Elife. 2019;8:1‐13. 10.7554/eLife.43476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsgóttir U, Onelöv E, Henter JI, Steineck G. Anxiety and depression in parents 4–9 years after the loss of a child owing to a malignancy: a population‐based follow‐up. Psychol Med. 2004;34(8):1431‐1441. 10.1017/S0033291704002740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thornton R, Nicholson P, Harms L. Scoping review of memory making in bereavement care for parents after the death of a newborn. JOGNN ‐ J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2019;48(3):351‐360. 10.1016/j.jogn.2019.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kochen EM, Jenken F, Boelen PA, et al. When a child dies: a systematic review of well‐defined parent‐focused bereavement interventions and their alignment with grief‐ and loss theories. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):28. 10.1186/s12904-020-0529-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aschenbrenner AP, Winters JM, Belknap RA. Integrative review: Parent perspectives on care of their child at the end of life. J Pediatr Nurs. 2012;27(5):514‐522. 10.1016/j.pedn.2011.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Donovan LA, Wakefield CE, Russell V, Cohn RJ. Hospital‐based bereavement services following the death of a child: a mixed study review. Palliat Med. 2015;29(3):193‐210. 10.1177/0269216314556851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chong PH, Walshe C, Hughes S. Perceptions of a good death in children with life‐shortening conditions: an integrative review. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(6):714‐723. 10.1089/jpm.2018.0335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lichtenthal WG, Sweeney CR, Roberts KE, et al. Bereavement follow‐up after the death of a child as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:S834‐S869. 10.1002/pbc.25700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Contro N, Sourkes BM. Opportunities for quality improvement in bereavement care at a children’s hospital: assessment of interdisciplinary staff perspectives. J Palliat Care. 2012;28(1):28‐35. 10.1177/082585971202800105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeCinque N, Monterosso L, Dadd G, Sidhu R, Lucas R. Bereavement support for families following the death of a child from cancer: Practice characteristics of Australian and New Zealand paediatric oncology units. J Paediatr Child Health. Published Online. 2004;40(3):131‐135. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jensen J, Weng C, Spraker‐Perlman HL. A provider‐based survey to assess bereavement care knowledge, attitudes, and practices in pediatric oncologists. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(3):266‐272. 10.1089/jpm.2015.0430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zwakman M, Verberne LM, Kars MC, Hooft L, Van Delden JJM, Spijker R. Introducing PALETTE: an iterative method for conducting a literature search for a review in palliative care. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):1‐9. 10.1186/s12904-018-0335-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Allison T, Peter S, Jonathan C. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2007;19(6):349‐357. http://login.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsovi&AN=edsovi.00042154.200712000.00004&site=eds‐live&scope=site [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dixon‐Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(35): 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brink HL, Thomsen AK, Laerkner E. Parents’ experience of a follow‐up meeting after a child’s death in the paediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;38:31‐39. 10.1016/j.iccn.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eggly S, Meert KL, Berger J, et al. A framework for conducting follow‐up meetings with parents after a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(2):147‐152. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181e8b40c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eggly S, Meert KL, Berger J, et al. Physicians’ conceptualization of “closure” as a benefit of physician‐parent follow‐up meetings after a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Palliat Care. 2013;29(2):69‐75. 10.1177/082585971302900202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Granek L, Barrera M, Scheinemann K, Bartels U. When a child dies: Pediatric oncologists’ follow‐up practices with families after the death of their child. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1626‐1631. 10.1002/pon.3770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meert KL, Eggly S, Pollack M, et al. Parents’ perspectives regarding a physician‐parent conference after their child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2007;151(1):50‐55. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meert KL, Eggly S, Berger J, et al. Physiciansʼ experiences and perspectives regarding follow‐up meetings with parents after a childʼs death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(2):e64‐e68. 10.1097/pcc.0b013e3181e89c3a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meert KL, Eggly S, Berg RA, et al. Feasibility and perceived benefits of a framework for physician‐parent follow‐up meetings after a child’s death in the PICU. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(1):148‐157. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a26ff3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meert KL, Eggly S, Kavanaugh K, et al. Meaning making during parent‐physician bereavement meetings after a child’s death. Heal Psychol. Published Online. 2015;34(4):453‐461. 10.1037/hea0000153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Midson R, Carter B. Addressing end of life care issues in a tertiary treatment centre: lessons learned from surveying parents’ experiences. J Child Heal Care. 2010;14(1):52‐66. 10.1177/1367493509347060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McHaffie HE, Laing IA, Lloyd DJ. Follow up care of bereaved parents after treatment withdrawal from newborns. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;84(2):F125‐F128. 10.1136/fn.84.2.F125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boelen PA, Van Den HMA, Van Den BJ, Psychology C. A cognitive‐behavioral conceptualization of complicated grief. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2006;13(2):109‐128. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shear K, Shair H. Attachment, loss, and complicated grief. Dev Psychobiol. 2005;47(3):253‐267. 10.1002/dev.20091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stevenson M, Achille M, Liben S, et al. Understanding how bereaved parents cope with their grief to inform the services provided to them. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(5):649‐664. 10.1177/1049732315622189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gillies J, Neimeyer RA. Loss, grief, and the search for significance: toward a model of meaning reconstruction in bereavement. J Constr Psychol. 2006;19(1):31‐65. 10.1080/10720530500311182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lichtenthal WG, Breitbart W. The central role of meaning in adjustment to the loss of a child to cancer: implications for the development of meaning‐centered grief therapy. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9(1):46‐51. 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Keesee NJ, Currier JM, Neimeyer RA. Predictors of grief following the death of one’s child: the contribution of finding meaning. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(10):1145‐1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feudtner C, Walter JK, Faerber JA, et al. Good‐parent beliefs of parents of seriously ill children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(1):39‐47. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. October TW, Fisher KR, Feudtner C, Hinds PS. The parent perspective: “being a good parent” when making critical decisions in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(4):291‐298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):5979‐5985. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lichtenthal WG, Roberts KE, Catarozoli C, et al. Regret and unfinished business in parents bereaved by cancer: a mixed methods study. Palliat Med. 2020;34(3):367‐377. 10.1177/0269216319900301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Surkan PJ, Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, et al. Perceptions of inadequate health care and feelings. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(2):317‐323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(2):257‐301. 10.1037/a0018301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li J, Stroebe M, Chan CLW, Chow AYM. Guilt in bereavement: a review and conceptual framework. Death Stud. 2014;38(3):165‐171. 10.1080/07481187.2012.738770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shear MK. Clinical practice. Complicated Grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):153‐160. 10.1056/NEJMcp1315618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kersting A, Brähler E, Glaesmer H, Wagner B. Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population‐based sample. J Affect Disord. 2011;131(1–3):339‐343. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zetumer S, Young I, Shear MK, et al. The impact of losing a child on the clinical presentation of complicated grief. J Affect Disord. 2015;170:15‐21. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, et al. Prolonged grief disorder: psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM‐V and ICD‐11. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Boelen PA, Smid GE. Disturbed grief: prolonged grief disorder and persistent complex bereavement disorder. BMJ. 2017;357(May):1‐10. 10.1136/bmj.j2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stack CG. Bereavement in paediatric intensive care. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13(8):651‐654. 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Contro NA, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen HJ. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1248‐1252. 10.1542/peds.2003-0857-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nelson JE, Angus DC, Weissfeld LA, et al. End‐of‐life care for the critically ill: A national intensive care unit survey. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(10):2547‐2553. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239233.63425.1D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cook P, White DK, Ross‐Russell RI, Cook P, White DK, Ross‐Russell RI. Bereavement support following sudden and unexpected death: guidelines for care. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87(1):36‐38. 10.1136/adc.87.1.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1