Abstract

We found two types of branched-chain amino acid permease gene (BAP2) in the lager brewing yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus BH-225 and cloned one type of BAP2 gene (Lg-BAP2), which is identical to that of Saccharomyces bayanus (by-BAP2-1). The other BAP2 gene of the lager brewing yeast (cer-BAP2) is very similar to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae BAP2 gene. This result substantiates the notion that lager brewing yeast is a hybrid of S. cerevisiae and S. bayanus. The amino acid sequence homology between S. cerevisiae Bap2p and Lg-Bap2p was 88%. The transcription of Lg-BAP2 was not induced by the addition of leucine to the growth medium, while that of cer-BAP2 was induced. The transcription of Lg-BAP2 was repressed by the presence of ethanol and weak organic acid, while that of cer-BAP2 was not affected by these compounds. Furthermore, Northern analysis during beer fermentation revealed that the transcription of Lg-BAP2 was repressed at the beginning of the fermentation, while cer-BAP2 was highly expressed throughout the fermentation. These results suggest that the transcription of Lg-BAP2 is regulated differently from that of cer-BAP2 in lager brewing yeasts.

Lager brewing yeasts (bottom-fermenting yeasts) were originally classified as Saccharomyces carlsbergensis (8) but have been recently reclassified as Saccharomyces pastorianus, which is thought to be a natural hybrid between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces bayanus (25). Tamai et al. (22) and Yamagishi and Ogata (27) reported that the genome of lager brewing yeasts consists of both types of chromosomes, those originating from S. cerevisiae and those from S. bayanus, indicating that the lager brewing yeasts have two types of allele, i.e., one that has its origin from S. cerevisiae and the other from S. bayanus. Fujii et al. (5) and Tamai et al. (23) reported that lager brewing yeasts contain two types of ATF1 gene and HO gene, respectively, one similar to that of S. cerevisiae and the other identical to that of S. bayanus. On the other hand, it has been reported that lager brewing yeasts contain an S. cerevisiae type gene and a Saccharomyces monacensis type gene (1, 9, 10). The amino acid sequence homology between the S. cerevisiae type gene and the non-S. cerevisiae type gene in lager brewing yeasts is high (75 to 94%) (1, 5, 9, 10, 23). It is as yet unclear whether all the non-S. cerevisiae type genes found in lager brewing yeasts originated from the same species (e.g., S. bayanus or S. monacensis).

In brewing, transport of branched-chain amino acids (i.e., leucine, valine, and isoleucine) is very important, specifically because the metabolites of these compounds are converted to higher alcohols, which are some of the most important flavors in alcoholic beverages. The branched-chain amino acids are transported by at least four permeases, which are the general amino acid permease (Gap1p) (7), the branched-chain amino acid permeases (Bap2p and Bap3p) (2, 6), and the high-affinity tyrosine permease (Tat1p) (4). Gap1p can transport all naturally occurring amino acids, including citrulline and d-amino acids (7, 12), and is active during growth on poor nitrogen sources, such as proline. Gap1p activity is downregulated transcriptionally and posttranslationally in response to preferred nitrogen sources, such as glutamine, aspargine, and ammonia (21). Under these conditions, most of the branched-chain amino acids are transported by Bap2p, Bap3p, and Tat1p. The transcription of the branched-chain amino acid permease genes (BAP2 and BAP3) is induced by some amino acids, such as leucine and phenylalanine, in the medium (2, 3), and this induction requires Ssy1p as a sensor for external amino acids (4).

We found that the constitutive expression of BAP2 in a brewing yeast strain accelerated the rates of assimilation for branched-chain amino acids, while the disruption of BAP2 did not affect assimilation rates for these amino acids during the brewing process (13). This suggests that there are possibly other functional permeases present during the brewing process. These could be Bap3p, Tat1p, and/or other branched-chain amino acid permease homologues, which exist in lager brewing yeasts.

In this paper, we report on the isolation and characterization of the non-S. cerevisiae type BAP2 gene found in lager brewing yeast.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

Yeast strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. The Escherichia coli strain JM109 (recA1 Δ[lac-proAB] endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 F′traD36 proAB lacIqZ ΔM15) (28) (TOYOBO Co., Ltd.) served as the plasmid host. Growth and handling of E. coli bacteria, plasmids, and yeast strains followed standard procedures (18, 19). Yeast cells were grown at 30°C in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium (18), YPM medium (1% yeast extract, 2% bacto-peptone, 2% maltose), or SD medium (2% glucose, 0.67% Yeast Nitrogen Base without amino acids; Difco). Yeast transformation was performed using the lithium acetate method (11). The selections for positive clones were carried out on either YPD plates supplemented with 300 μg of G418/ml, YPD plates supplemented with 10 mM formaldehyde, or YPD plates supplemented with 1 μg of aureobasidin A (Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd.)/ml. For the suppression of the growth defect of the Δgap1 Δssy1 strain, SLD agar plates (0.17% Yeast Nitrogen Base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate [Difco], 2% glucose, 0.1% leucine, 2% agar) were used. For the transcription analysis in poor nitrogen source, SPM medium (0.17% Yeast Nitrogen Base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate [Difco], 2% maltose, 0.1% proline) was employed.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Yeast species and strain | Source and remarks |

|---|---|

| S. pastrianus BH-225 | Lager brewing yeast from our own stock |

| S. bayanus IFO1127 | S. bayanus type strain from IFOa |

| S. cerevisiae X2180-1A | MATaSUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1 from YGSCb |

| S. cerevisiae YK006 | MATaSUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1 gap1::AUR1-C |

| S. cerevisiae YK007 | MATaSUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1 gap1::AUR1-C ssy1::SFA1 |

| S. cerevisiae YK008 | MATaSUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1 gap1::AUR1-C ssy1::SFA1 with a vector (pYCGPY) |

| S. cerevisiae YK009 | MATaSUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1 gap1::AUR1-C ssy1::SFA1 with pYCGPYBP2 [PYK1p-BAP2] |

| S. cerevisiae YK010 | MATaSUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1 gap1::AUR1-C ssy1::SFA1 with pYCGPYLgBP [PYK1p-Lg-BAP2] |

IFO, The Institute for Fermentation, Osaka, Japan.

YGSC, Yeast Genetics Stock Center, University of California, Berkeley.

Southern analysis.

Yeast genomic DNA was prepared according to the standard method (18). The genomic DNA was digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, fractionationed in a 1% agarose gel, and transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N+; Amersham Pharmacia, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Labeling probe DNA, hybridization, membrane washing, and detection of hybridizing probe DNA were carried out with a Gene Images random-prime labeling and detection system (Amersham Pharmacia). The hybridization and washing temperature was 60°C, except in the case of low-stringency conditions (50°C).

Cloning and DNA sequencing of Lg-BAP2.

Lg-BAP2 was cloned by colony hybridization from SpeI libraries of the lager brewing yeast S. pastorianus BH-225 and S. bayanus IFO1127 constructed in pBlueScript SK(−) (20). An about 2.7-kb SpeI fragment was cloned from each strain and sequenced using an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems).

Construction of plasmids.

The construction of plasmids for the disruption of the general amino acid permease gene (GAP1) (12) and amino acid sensor gene (SSY1) (4) was carried out using PCR techniques. The plasmids and oligonucleotides used are listed in Table 2. Amplified PCR products were subcloned using the TOPO TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen) according to the supplier's instructions. The integrity of PCR fragments was verified by sequencing. The GAP1 coding region was prepared by PCR with genomic DNA of X2180-1A as template using the oligonucleotides 001 and 002 as primers. After digestion with SacI and BamHI, the 1.9-kb GAP1 open reading frame (ORF) was inserted into the SacI-BamHI gap of pUC19 (28) to yield pGAP1. The yeast glyceraldehyde- 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (TDH3) promoter was amplified from pIGZ2 (14) by PCR using the oligonucleotides 003 and 004 as primers. After digestion with SacI and HindIII, the TDH3 promoter was ligated with the 2.0-kb HindIII-SalI fragment encoding AUR1-C (aureobasidin A resistance gene) prepared from pAUR112 (Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd.), and inserted into the SacI-SalI gap of pUC19 to yield pTDH3-AUR1C. The plasmid pTDH3-AUR1C was digested with XbaI, repaired, and resealed with phosphorylated BglII linkers. The 3.1-kb KpnI-BglII TDH3-AUR1-C fragment was excised and inserted into the KpnI-BglII gap of pGAP1 to give pΔGAP1. Plasmid pΔGAP1 was linearized at SacI and XbaI sites before transformation of yeast cells.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this studya

| Name | Description or sequence |

|---|---|

| Plasmids | |

| pGAP1 | 1.9-kb fragment containing GAP1 in pUC19 |

| pTDH3-AUR1C | 3.1-kb fragment containing TDH3-AUR1-C in pUC19 |

| pΔGAP1 | gap1::TDH3-AUR1-C in pUC19 |

| pUC-SFA1 | 2.5-kb fragment containing TDH3-SFA1 in pUC119 |

| pUC-SSY1 | 1.4-kb fragment containing SSY1 (nucleotide positions −715 to −4 and 1817 to 2550) in pUC18 |

| pΔSSY1 | ssy1::TDH3-SFA1 in pUC18 |

| pYCGPY | Centromere-based vector with TDH3-G418r |

| pBAP2Sph | 4.6-kb SphI fragment containing BAP2 in pUC18 |

| pBAP2ES | 4.6-kb SphI/Eco47III fragment containing BAP2 in pUC18 |

| pBAP2ORF | 2.0-kb SacI/KpnI fragment containing BAP2 in pUC18 |

| pYCGPYBP2 | BAP2 in pYCGPY |

| pYCGPYLgBP | Lg-BAP2 in pYCGPY |

| Oligonucleotides | |

| 001 | 5′CTCGAGCTCATGAGTAATACTTCTTCGT-3′ |

| 002 | 5′-CTCGGATCCCTTTAGATTAATGACGAGA-3′ |

| 003 | 5′-TCAGAGCTCGGTACCGGAGCTTACCAGTTCTCA-3′ |

| 004 | 5′-TCAAAGCTTCTGTTTATGTGTGTTTATTCG-3′ |

| 005 | 5′-AAGCTTAATGTCCGCCGCTACTGTTGG-3′ |

| 006 | 5′-GTCGACGTTGGTAGTTAGGAACAGGC-3′ |

| 007 | 5′-GGTACCGGAGCTTACCAGTTCTCACA-3′ |

| 008 | 5′-TAAAAGCTTCTGTTTATGTGTGTTT-3′ |

| 009 | 5′-GAATTCAGGAAAAACTCGAGAGTTACTAG-3′ |

| 010 | 5′-GGTACCTCAAGGAACTTCCCTATTTTTAAGC-3′ |

| 011 | 5′-GGTACCCAGTGTCGACAGGTTATTCTAGTCCTTGGGTTG-3′ |

| 012 | 5′-GGATCCAGGTAACCAACTTCTTCGCTCTT-3′ |

| 013 | 5′-GATCACCCGGGT-3′ |

| 014 | 5′-AAGCTTAGATCTTCAGAACTAAAAAAATAATAAGGAA-3′ |

| 015 | 5′-TCTAGAGCTCTGTGATGATGTTTTATTTGTTTTGATT-3′ |

| 016 | 5′-TCTAGAACAGGATCCTTGGTTGAACACGTTGCCAAG-3′ |

| 017 | 5′-GAATTCACTAGTGATCCGGAGCTTTCAATCAAT-3′ |

| 018 | 5′-GAGCTCTTTGAATGCCATTATCAGAAGAC-3′ |

| 019 | 5′-GCGGCCGCTAACGACTAGTGTCCGAACTTTA-3′ |

The underlined nucleotides were added to generate restriction sites.

A formaldehyde resistance gene, SFA1 (24) of S. cerevisiae, was used as a dominant selective marker in the construction of the Δssy1 strain. The SFA1 gene fragment (nucleotide positions −1 to 1401) was prepared by PCR with genomic DNA of X2180-1A as a template using the oligonucleotides 005 and 006 as primers. The oligonucleotide primers 007 and 008 were used for amplification of the TDH3 promoter as described above. The resultant 1.4-kb HindIII-SalI fragment for SFA1 and 1.1-kb KpnI-HindIII fragment for the promoter sequence were ligated together into the KpnI and SalI sites of the pUC119 vector (26) to give pUC-SFA1. The 0.7-kb SSY1 5′-flanking region (nucleotide positions −715 to −4) was obtained by PCR with genomic DNA of X2180-1A as a template by using the oligonucleotide primers 009 and 010. The 0.7-kb SSY1 3′-flanking region (nucleotide positions 1817 to 2550) was obtained in the same way, using the oligonucleotide primers 011 and 012. The 5′-flanking fragment was digested with EcoRI and KpnI, and the 3′-flanking fragment was digested with KpnI and BamHI. The resultant fragments were ligated together into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of the pUC18 vector (28), in which the original SalI site had been eliminated. The resulting plasmid was designated pUC-SSY1. To construct pΔSSY1, the 2.5-kb KpnI-SalI fragment was excised from pUC-SFA1 and inserted into the KpnI-SalI gap of pUC-SSY1. pΔSSY1 was digested with EcoRI and BamHI prior to the transformation of YK006 (Δgap1) to obtain a Δgap1 Δssy1 double disruptant (YK007).

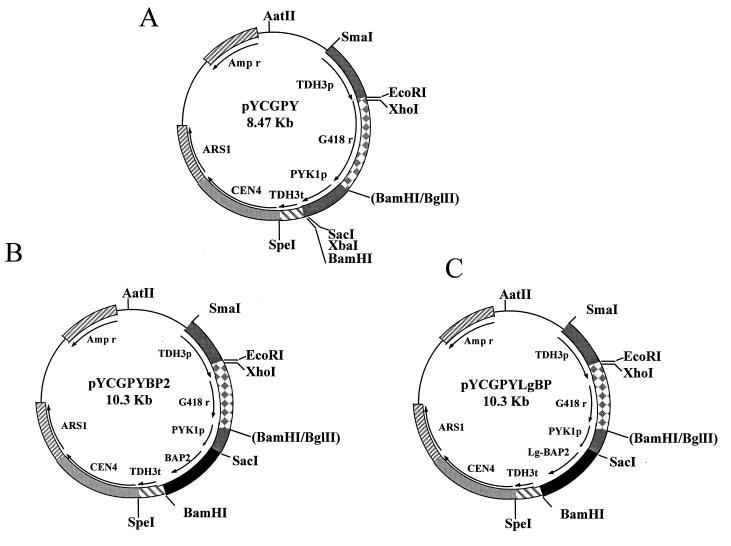

The plasmid pYCGPY (Fig. 1A) is a centromeric vector that allows expression of genes placed downstream of the yeast pyruvate kinase (PYK1) promoter and contains the kanamycin resistance (G418r) gene (15) for use as a selective marker. The G418r gene embraced by the TDH3 promoter and terminator sequences was prepared as a 2.5-kb BamHI fragment from pIGZ2 (14) and cloned into the BamHI site of YCp50 (17) to give YCpG418r. YCpG418r was partially digested with BamHI and self-ligated with a phosphorylated oligonucleotide, 013, to eliminate one of the two BamHI sites present in YCpG418r. The resulting plasmid (YCpG418rSma) was then digested with AatII and BamHI to release a 2.9-kb AatII-BamHI fragment. To obtain the PYK1 promoter region (nucleotide positions −798 to −1), PCR was carried out with the oligonucleotides 014 and 015 as primers and genomic DNA of X2180-1A as the PCR template. The TDH3 terminator region was amplified from plasmid pIGZ2 by PCR, with the oligonucleotides 016 and 017 as primers. The 0.8-kb HindIII-XbaI PYK1 promoter fragment and the 170-bp XbaI-EcoRI TDH3 terminator fragment were coligated into the HindIII-EcoRI gap of pUC19 to create pPTPYK1. The 1.0-kb BglII-SpeI fragment was then excised from pPTPYK1 and ligated with the 2.9-kb AatII-BamHI fragment from YCpG418rSma and the 4.6-kb SpeI-AatII fragment from YCp50 to obtain pYCGPY.

FIG. 1.

The structures of the plasmids. (A) PYCGPY is a centromeric vector containing yeast centromere sequence (CEN4), yeast autonomously replicating sequence (ARS1), yeast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase promoter (TDH3p), the G418 resistance gene (G418r), the yeast pyruvate kinase promoter (PYK1p), the yeast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase terminator (TDH3t), and the ampicillin resistance gene (Ampr). (B and C) BAP2 and Lg-BAP2 were inserted in the SacI-BamHI site of PYCGPY and named PYCGPYBP2 and PYCGPYLgBP, respectively.

A 9.0-kb DNA fragment containing the BAP2 locus was isolated from a genomic library derived from S. cerevisiae (strain X2180-1A). The 4.6-kb SphI fragment containing the BAP2 ORF was excised and subcloned into the SphI gap of pUC18 to give pBAP2Sph. pBAP2Sph was digested with SmaI and Eco47III and resealed to give pBAP2ES. The 5′-flanking region was trimmed with exonuclease III, and a 500-bp SacI-PstI fragment encompassing the 60-bp 5′-flanking region and part of the BAP2 ORF was prepared and ligated together with a 1.5-kb PstI-KpnI fragment from pBAP2ES into the SacI-KpnI gap of pUC18 to give pBAP2ORF. Eventually the SacI-BamHI fragment from pBAP2ORF, containing the BAP2 ORF, was inserted into the SacI-BamHI gap of pYCGPY, thus creating pYCGPYBP2 (Fig. 1B), in which the BAP2 gene is controlled by the constitutive PYK1 promoter. The Lg-BAP2 ORF was prepared as a SacI-BamHI fragment by PCR with genomic DNA of the brewing yeast BH-225 as a template using the oligonucleotides 018 and 019 as primers. The fragment of Lg-BAP2 ORF was inserted into the SacI and BamHI sites of pYCGPY and placed under control of the constitutive PYK1 promoter, to yield pYCGPYLgBP (Fig. 1C).

Northern analysis.

Total RNA was prepared according to the standard method (18). Agarose gel electrophoresis was carried out with 45 μg of RNA per lane, and subsequent Northern analysis was performed with 32P-labeled DNA fragments as probes. After hybridization, the blot was washed twice with 0.1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) as described previously (18). This condition is sufficiently stringent to distinguish the transcripts of cer-BAP2 and Lg-BAP2 in lager brewing yeast BH-225 using a BAP2 fragment (nucleotide positions +180 to +891) isolated from S. cerevisiae X2180-1A and an Lg-BAP2 fragment (+1 to +1300) from BH-225 as probes. For the detection of other genes, approximately 700-bp PCR products from genomic DNA of X2180-1A were used as probes.

Fermentation conditions.

The fermentation was performed in a 2-liter fermentation tube. The initial wort gravity was 12% (wt/vol) prepared with 100% malt. The fermentation was carried out at 12°C with a pitching rate of 15 × 106 cells/ml of wort and a dissolved oxygen content of 9 ppm.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data of Lg-BAP2 from lager brewing yeast BH-225 and by-BAP2-1 from S. bayanus IFO1127 have been deposited with DDBJ under the accession numbers AB049008 and AB049009, respectively.

RESULTS

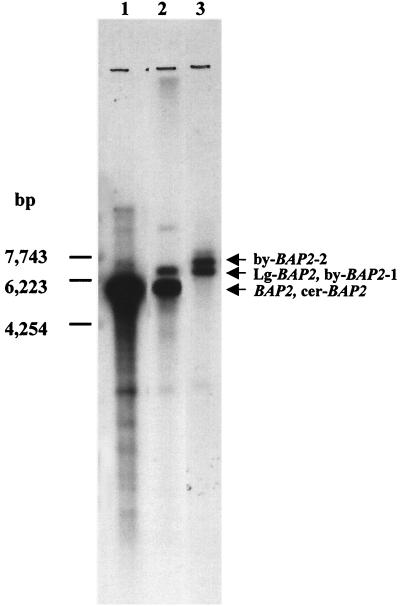

Southern analysis of BAP2 in lager brewing yeast, S. cerevisiae, and S. bayanus.

To investigate the existence of the non-S. cerevisiae-type of BAP2 in a lager brewing yeast, low-stringency (50°C) Southern analysis of yeast genomic DNAs from S. cerevisiae X2180-1A, lager brewing yeast strain BH-225, and S. bayanus IFO1127 was carried out using a fragment of the BAP2 gene (nucleotide positions +180 to +891) from S. cerevisiae X2180-1A as a probe. A 5.5-kb DNA fragment from S. cerevisiae X2180-1A hybridized to this probe (Fig. 2, lane 1), while two fragments from S. bayanus IFO1127 hybridized to this probe (Fig. 2, lane 3). Lager brewing yeast strain BH-225 showed two fragments, one identical in size to that of S. cerevisiae and the other identical to one of the two bands of S. bayanus IFO1127 (Fig. 2, lane 2). This result suggests that the lager brewing yeast BH-225 possesses two BAP2 genes, one similar to that of S. cerevisiae and the other similar to that of S. bayanus. As shown in Fig. 2, we named the S. cerevisiae type BAP2 gene and the non-S. cerevisiae type BAP2 homologue in BH-225 cer-BAP2 and Lg-BAP2, respectively, and we named the two BAP2 homologues in S. bayanus IFO1127 by-BAP2-1 and by-BAP2-2, respectively. A DNA fragment encompassing the 5′-flanking region and the open reading frame of cer-BAP2 (nucleotide positions −886 to +1827) in BH-225 was isolated by PCR using chromosomal DNA of BH-225 as a template. The sequence similarity between the isolated fragment and the BAP2 sequence in the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) (http://genome-www.stanford.edu/Saccharomyces) was proven to be 99.3% (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Genomic Southern hybridization with S. cerevisiae BAP2 probe (nucleotides 180 to 891). Genomic DNA was digested with XbaI. Lane 1, S. cerevisiae X2180-1A; lane 2, lager brewing yeast BH-225; lane 3, S. bayanus IFO1127.

Cloning of the BAP2 homologue from lager brewing yeast and S. bayanus.

For the cloning of the non-S. cerevisiae type BAP2 homologue (Lg-BAP2) from lager brewing yeast, we obtained a 1.3-kb PCR fragment of Lg-BAP2 from lager brewing yeast BH-225 by using primers designed on the BAP2 sequence. The DNA homology between the BAP2 sequence in SGD and Lg-BAP2 in this region was about 80% (data not shown). Southern analysis was carried out using this PCR fragment of Lg-BAP2 as a probe. As shown in Fig. 3A, this fragment did not hybridize to X2180-1A (lane 1 and lane 4). Lager brewing yeast BH-225 showed one fragment that hybridized with this probe, which was similar in size to one of the two fragments of S. bayanus IFO1127 (lanes 2 and lane 5). S. bayanus IFO1127 showed two fragments that hybridized with this probe, one identical in size to that of Lg-BAP2 of BH-225 (by-BAP2-1) and another one (by-BAP2-2) (lane 3 and lane 6). The hybridization intensity of by-BAP2-1 with the probe (Lg-BAP2) was higher than that of by-BAP2-2, suggesting that the DNA homology between by-BAP2-1 and Lg-BAP2 is higher than that between by-BAP2-2 and Lg-BAP2.

FIG. 3.

Genomic Southern hybridization with the Lg-BAP2 probe. (A) Genomic DNA was digested with EcoRV (lanes 1 to 3) and with XbaI (lanes 4 to 6). Lane 1 and lane 4, S. cerevisiae X2180-1A; lane 2 and lane 5, lager brewing yeast BH-225; lane 3 and lane 6, S. bayanus IFO1127. (B) Genomic DNA was digested with SpeI. Lane 1, lager brewing yeast BH-225; lane 2, S. bayanus IFO1127.

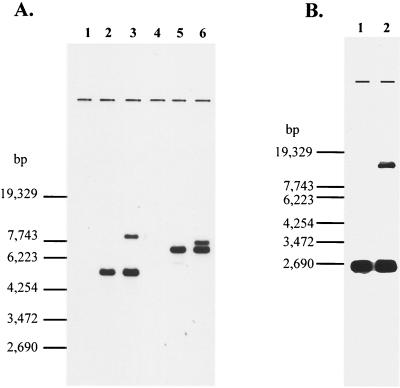

Further Southern blot analysis indicated that Lg-BAP2 from BH-225 and by-BAP2-1 from IFO1127 could be cloned as approximately 2.7-kb SpeI fragments (Fig. 3B). Thus, SpeI-libraries of genomic DNA of BH-225 and IFO1127 were constructed in pBlueScript SK(−) and the clones containing the Lg-BAP2 or by-BAP2-1 were isolated by colony hybridization, using the PCR fragment of Lg-BAP2 as a probe. The SpeI fragment of approximately 2.7 kb in size which contains the whole ORF and 5′-flanking region (about 800 bp) was obtained from each strain. From the results of DNA sequencing, it was revealed that the sequence of Lg-BAP2 from BH-225 was 100% identical to that of by-BAP2-1 from S. bayanus IFO1127. DNA homology of the 5′-flanking region (about 800 bp) and the open reading frame between the BAP2 sequence in SGD and Lg-BAP2 was 60 and 80%, respectively. The amino acid sequence comparison between Bap2p from SGD and Lg-Bap2p from BH-225 is shown in Fig. 4. Deduced amino acid sequence homology between Bap2p and Lg-Bap2p was 88%. This homology seems to be comparable with previously reported homology between lager brewing yeast-specific proteins and their S. cerevisiae counterparts: Met2p (94%), Ilv1p (95.7%), Ilv2p (92.3%), partial Ura3p (93%) (9) and Atf1p (75.7%) (5).

FIG. 4.

Amino acid sequence homology between the Lg-Bap2 protein of the lager brewing yeast BH-225 and the Bap2 protein of S. cerevisiae. The numbers indicate the amino acid positions. Amino acid sequence identities between two proteins are shaded.

There are some reports regarding the chromosomal structure of lager brewing yeasts (22, 27). In these reports, it is shown that lager brewing yeasts have chromosomes that are a mix of those from S. cerevisiae and from S. bayanus. From the results of pulsed-field electrophoresis and subsequent Southern analysis, the sizes of chromosomes carrying Lg-BAP2 and by-BAP2-1 in the lager brewing yeast BH-225 and S. bayanus IFO1127, respectively, were identical (S. bayanus chromosome 12). Additionally, the sizes of chromosomes harboring cer-BAP2 and BAP2 in BH-225 and S. cerevisiae X2180-1A, respectively, were identical (S. cerevisiae chromosome II) (data not shown).

Function of Lg-Bap2p as a branched-chain amino acid permease.

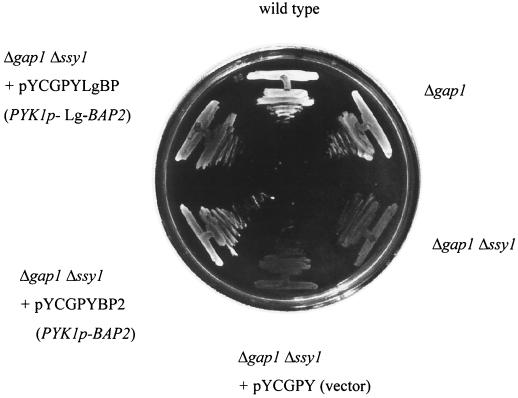

Branched-chain amino acids are transported by at least four transporters, which are the general amino acid permease (Gap1p) and high- and low-affinity transporters specific for branched-chain amino acids (Bap2p, Bap3p, and Tat1p). Didion et al. (4) showed that deletion of the gene for amino acid sensor SSY1 in a Δgap1 strain abolishes branched-chain amino acid uptake to an extent similar to that of the Δgap1 Δbap2 Δbap3 Δtat1 strain. To confirm the function of Lg-Bap2p as a branched-chain amino acid permease, we attempted the constitutive expression of Lg-BAP2 in YK007 (Δgap1 Δssy1) and investigated the complementation of the growth defect of YK007 on SLD agar plates, which contained leucine as the sole nitrogen source. Lg-BAP2 could complement the growth defect of YK007 on SLD agar plates as well as BAP2 (Fig. 5). These results indicate that Lg-Bap2p, as well as Bap2p, is functional as a leucine transporter.

FIG. 5.

Growth phenotypes of strains X2180-1A (wild type), YK006 (Δgap1), YK007 (Δgap1 Δssy1), YK008 (Δgap1 Δssy1, pYCGPY [vector]), YK009 (Δgap1 Δssy1, pYCGPYBP2 [PYK1p-BAP2]), and YK010 (Δgap1 Δssy1, pYCGPYLgBP [BPPYK1p-Lg-BAP2]) after 3 days of growth on an SLD agar plate which contained leucine as the sole nitrogen source.

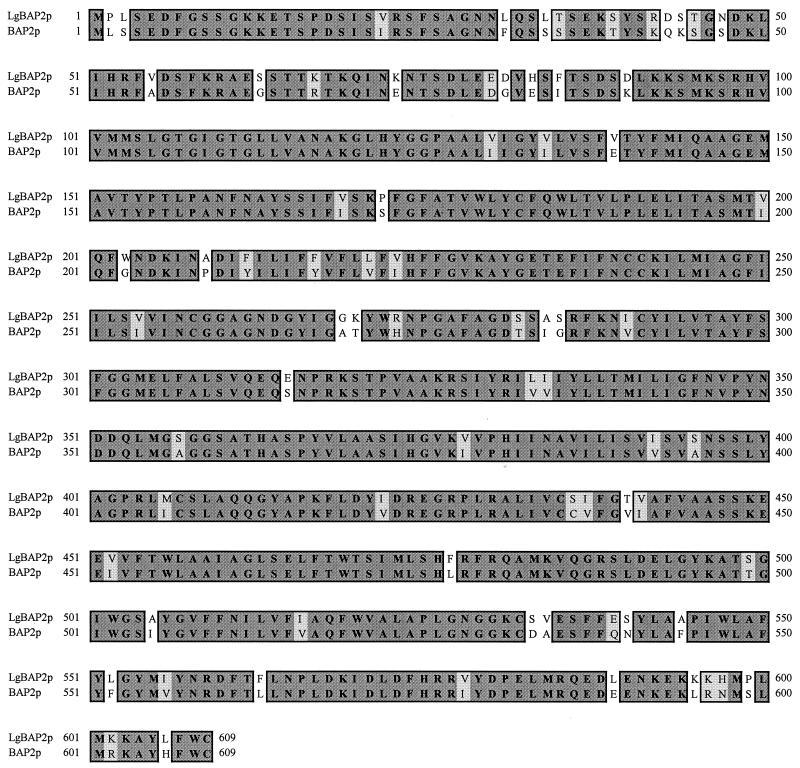

The expression profile of branched-chain amino acid permease genes in lager brewing yeast BH-225.

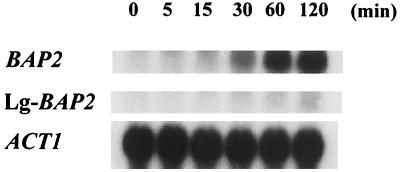

Since DNA homology of the promoter region between BAP2 in SGD and Lg-BAP2 from lager brewing yeast BH-225 was rather low, we anticipated that cer-BAP2 and Lg-BAP2 in BH-225 are differently regulated. As it is reported that transcription of the branched-chain amino acid permease genes (BAP2 and BAP3) is induced by several amino acids, especially by leucine (2, 3), we investigated the transcriptional induction of cer-BAP2 and Lg-BAP2 in BH-225 in response to leucine addition. The transcription of cer-BAP2 (detected with a BAP2 probe) was induced by leucine 30 min after addition, while the transcription of Lg-BAP2 was not induced (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

The transcription of BAP2 homologues in the lager brewing yeast BH-225 after addition of leucine was analyzed by Northern blotting. Cells were pregrown overnight on SD medium at 30°C. From these precultures, main cultures were inoculated at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 in fresh SD medium and grown subsequently to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.65 (for 4 h) at 30°C. Then, leucine was added to a final concentration of 2 mM. Total RNA was isolated at different time points after leucine addition and hybridized with BAP2, Lg-BAP2, and ACT1 as probes. ACT1 was used as a loading control.

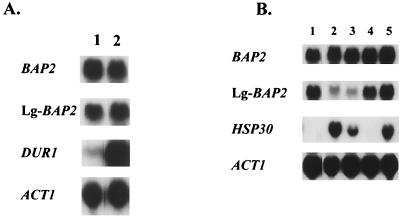

Furthermore, we investigated the change in the transcription levels of cer-BAP2 and Lg-BAP2 in response to nitrogen starvation, because brewing yeast cells undergo the nitrogen starvation during the latter period of fermentation. The cells were transferred from amino acid-rich medium (YPM) to nitrogen-poor medium (SPM), and the mRNA level was analyzed (Fig. 7A). The transcription levels of both cer-BAP2 (detected with the BAP2 probe) and Lg-BAP2 did not change after transfer to nitrogen-poor medium, while the transcription of DUR1 (urea amidolyase gene, inducible in response to nitrogen starvation) was induced after transfer to nitrogen-poor medium.

FIG. 7.

(A) The transcription of BAP2 homologues in the lager brewing yeast BH-225 in response to nitrogen starvation was analyzed by Northern blotting. Total RNA was isolated after cultivation for 4 h in YPM medium (lane 1) and after transfer to SPM medium and was cultivated for 2 h (lane 2) and hybridized with BAP2, Lg-BAP2, DUR1, and ACT1 as probes. The blot that was hybridized with Lg-BAP2 probe was overexposed for comparison of the transcriptional level in these conditions. ACT1 was used as a loading control, and DUR1 was used as a control nitrogen starvation-induced gene. (B) The transcription of BAP2 homologues in the lager brewing yeast BH-225 in response to various stresses was analyzed by Northern blotting. Total RNA was isolated after incubation in YPM medium at 30°C (lane 1); in YPM medium containing 8% ethanol at 30°C (lane 2); in YPM medium containing 1 mM sorbate (pH 4.5) at 30°C (lane 3); in YPM medium containing 27% maltose at 30°C (lane 4); and in YPM medium at 37°C (lane 5) and hybridized with BAP2, Lg-BAP2, HSP30, and ACT1 as probes. ACT1 was used as a loading control, and HSP30 was used as a control stress-induced gene.

We also investigated the transcription of cer-BAP2 and Lg-BAP2 in response to various stresses, because brewing yeast cells are put under such stresses as a high concentration of alcohol, low pH, and osmotic stress due to a high concentration of sugars during beer fermentation. Some stress-inducible genes, such as a heat-shock-protein-encoding gene, HSP30, are induced in the latter period of fermentation (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 7B, the transcription of Lg-BAP2 was repressed when cells were treated with ethanol and weak organic acid (1 mM sorbate), while other treatment, such as osmotic stress (27% maltose) and heat shock (37°C), did not affect its transcription. Conversely, the transcription of cer-BAP2 (detected with the BAP2 probe) was not affected by any of these treatments. The control gene for stress induction, HSP30, was induced when cells were treated with ethanol, weak organic acid, and heat shock.

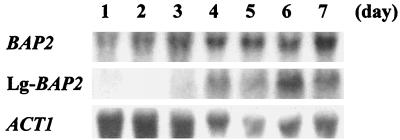

Finally, we investigated the transcription of cer-BAP2 and Lg-BAP2 during beer fermentation by Northern analysis. The transcription level of Lg-BAP2 was rather low at the beginning of the fermentation period, while cer-BAP2 (detected with the BAP2 probe) was highly expressed throughout the fermentation (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

The transcription of BAP2 homologues in the lager brewing yeast BH-225 during wort fermentation was analyzed by Northern blotting. Total RNA was isolated after 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 days of the fermentation period and hybridized with BAP2, Lg-BAP2, and ACT1 as probes. ACT1 was used as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

We have been investigating the transport of branched-chain amino acids during the brewing process, specifically because metabolic regulation of these compounds is important in the flavor control of alcohol beverages.

In this report, we investigated the branched-chain amino acid permease genes in a lager brewing yeast and found that it has two divergent BAP2 genes, one similar to that of S. cerevisiae and the other similar to that of S. bayanus. We have cloned the non-S. cerevisiae type BAP2 homologue from a brewing yeast, BH-225 (Lg-BAP2), and another BAP2 homologue from S. bayanus IFO1127 (by-BAP2-1), and found that they were 100% identical to each other. This result substantiates the notion that lager brewing yeast is a hybrid between S. cerevisiae and S. bayanus.

The results of Southern blot analysis revealed that S. bayanus IFO1127 has another BAP2 homologue (by-BAP2-2), which is different from Lg-BAP2 and by-BAP2-1 (Fig. 2 and 3). We have found that Saccharomyces uvarum IFO 0615 (type strain) showed a fragment that hybridized with the Lg-BAP2 probe, which is similar in size to by-BAP2-2 (data not shown). It suggests that IFO1127 could be a hybrid between S. bayanus and S. uvarum. Rainieri et al. (16) have reported that the type strain of S. bayanus and other strains that have been classified as S. bayanus lack homogeneity and have hypothesized that they are natural hybrids. Our results may support this hypothesis.

The transcription analysis revealed that Lg-BAP2 is regulated differently from cer-BAP2 in the brewing yeast. The former is not induced by the addition of leucine, whereas the latter is. The BAP2 promoter harbors putative binding sites for Gen4p and Leu3p (6), which also exist in the Lg-BAP2 promoter, but it has been shown that these sites are not involved in the transcriptional induction of BAP2 by leucine (3). De Boer et al. (2) showed that a portion of the BAP3 promoter (from −418 to −392 relative to the ATG start codon [UASaa]) is necessary and sufficient for the induction of BAP3 transcription by amino acids. The element found in the BAP2 promoter (nucleotide positions −417 to −400) is very similar to the UASaa of the BAP3 promoter, while the corresponding region of the Lg-BAP2 promoter is rather different (data not shown). This result supports the hypothesis that the UASaa is necessary for the induction of transcription by leucine. Since the wort prepared with 100% malt contains about 1 to 2 mM leucine, the difference of the transcription level of cer-BAP2 and that of Lg-BAP2 in the beginning of the fermentation period may be due to the difference of these genes in responsiveness to leucine.

The transcription of Lg-BAP2 seemed to be induced in the latter period of fermentation. In this period, most amino acids are exhausted and yeast cells are exposed to nitrogen starvation. However, the transcription of Lg-BAP2 was not induced in a poor nitrogen source, suggesting that the induction of Lg-BAP2 transcription in the latter period of fermentation is not due to nitrogen starvation. Yeast cells are also put under a lot of stress during fermentation. The concentration of alcohol increases and wort pH decreases in the latter period of fermentation. However, since the transcription of Lg-BAP2 was repressed in the presence of alcohol and weak acid (Fig. 7B), the induction of Lg-BAP2 transcription in the latter period of fermentation is not due to these stresses.

The mechanisms that differentiate the transcription profiles of cer-BAP2 and Lg-BAP2 during fermentation are expected to be very complicated because there are likely a lot of factors which could affect the transcription of these two genes. One of them could be the leucine concentration in wort. Further investigations are under way to clarify the factors involved in the distinct regulation of cer-BAP2 and Lg-BAP2. It is our aim to determine which phenotypes of lager brewing yeast are mainly attributed to the genes derived from non-S. cerevisiae type chromosomes. We hope that the identification and analysis of lager brewing yeast-specific genes that are essential for beer fermentation will help us improve the quality of beer production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Y. Kaneko, G. G. Stewart, C. Slaughter, and O. Younis for critical reading of the manuscript. The expert technical assistance of Y. Itokui is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borsting C, Hummel R, Schultz E R, Rose T M, Pedersen M B, Knudsen J, Kristiansen K. Saccharomyces carlsbergensis contains two functional genes encoding the acyl-CoA binding protein, one similar to the ACB1 gene from S. cerevisiae and one identical to the ACB1 gene from S. monacensis. Yeast. 1997;13:1409–1421. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199712)13:15<1409::AID-YEA188>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Boer M, Bebelman J P, Goncalves P M, Maat J, Van Heerikhuizen H, Planta R J. Regulation of expression of the amino acid transporter gene BAP3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:603–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Didion T, Grausland M, Kielland-Brandt M C, Andersen H A. Amino acids induce expression of BAP2, a branched-chain amino acid permease gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2025–2029. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2025-2029.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Didion T, Regenberg B, Jørgensen M U, Killand-Brandt M C, Andersen H A. The permease homolog Ssy1p controls the expression of amino-acid and peptide transporter genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:643–650. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujii T, Yoshimoto H, Nagasawa N, Bogaki T, Tamai Y, Hamachi M. Nucleotide sequences of alcohol acetyltransferase genes from lager brewing yeast, Saccharomyces carlsbergensis. Yeast. 1996;12:593–598. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199605)12:6%3C593::AID-YEA593%3E3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grauslund M, Didion T, Kielland-Brandt M C, Andersen H A. BAP2, a gene encoding a permease for branched-chain amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1269:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(95)00138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grenson M, Hou C, Crabeel M. Multiplicity of the amino acid permeases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. IV. Evidence for a general amino acid permease. J Bacteriol. 1970;103:770–777. doi: 10.1128/jb.103.3.770-777.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen E C. Recherches sur la morphologie des ferments alcooliques. XIII. Nouvelles etudes sur les levures de brasserie a fermentation basses. C R Trav Lab Carlasberg. 1908;7:179–217. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen J, Cherest H, Kielland-Brandt M C. Two divergent MET10 genes, one from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and one from Saccharomyces carlsbergensis, encode the alpha subunit of sulfite reductase and specify potential binding sites for FAD and NADPH. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6050–6058. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6050-6058.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen J, Kielland-Brandt M C. Saccharomyces carlsbergensis contains two functional MET2 alleles similar to homologues from S. cerevisiae and S. monacensis. Gene. 1994;140:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90727-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jauniaux J C, Grenson M. GAP1, the general amino acid permease gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleotide sequence, protein similarity with the other bakers yeast amino acid permeases, and nitrogen catabolite repression. Eur J Biochem. 1990;190:39–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kodama, Y., F. Omura, K. Miyajima, and T. Ashikari. Control of higher alcohol production by manipulation of the BAP2 gene in brewing yeast. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem., in press.

- 14.Nakazawa N, Ashikari T, Goto N, Amachi T, Nakajima R, Harashima S, Oshima Y. Partial restoration of sporulation defect in sake yeasts kyokai No. 7 and No. 9 by increased dosage of IME1 gene. J Ferment Bioeng. 1992;73:265–270. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oka A, Sugisaki H, Takanami M. Nucleotide sequence of the kanamaycin resistance transposon Tn 903. J Mol Biol. 1981;147:217–226. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rainieri S, Zambonelli C, Hallsworth J E, Pulvirenti A, Giudici P. Saccharomyces uvarum, a distinct group within Saccharomyces sensu stricto. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;177:177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose M D, Novick P, Thomas J H, Botstein D, Fink G R. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae genomic plasmid bank based on a centromere-containing shuttle vector. Gene. 1987;60:237–243. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose M D, Winston F, Hieter P. Methods in yeast genetics: a laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Short J M, Fernandez J M, Sorge J A, Huse W D. Lambda ZAP: a bacteriophage lambda expression vector with in vivo excision properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7583–7600. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanbrough M, Magasanik B. Transcriptional and posttranslational regulation of the general amino acid permease of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:94–102. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.94-102.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamai Y, Momma T, Yoshimoto H, Kaneko Y. Co-existence of two types of chromosome in the bottom fermenting yeast, Saccharomyces pastorianus. Yeast. 1998;14:923–933. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<923::AID-YEA298>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamai Y, Tanaka K, Umemoto N, Tomizuka K, Kaneko Y. Diversity of the HO gene encoding an endonuclease for mating-type conversion in the bottom fermenting yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus. Yeast. 2000;16:1335–1343. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(200010)16:14<1335::AID-YEA623>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van den Berg M A, Steensma H Y. Expression cassettes for formaldehyde and fluoroacetate resistance, two dominant markers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:551–559. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199705)13:6<551::AID-YEA113>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaughan-Martini A, Martini A. Saccharomyces Myen ex Reessm. In: Kurtzman C P, Fell J W, editors. The yeasts, a taxonomic study. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1998. pp. 358–371. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vieira J, Messing J. Production of single-stranded plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 1987;153:3–11. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)53044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamagishi H, Ogata T. Chromosomal structures of bottom fermenting yeasts. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1999;22:341–353. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(99)80041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]