Abstract

Reducing the rate of over‐representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out‐of‐home care (OOHC) is a key Closing the Gap target committed to by all Australian governments. Current strategies are failing. The “gap” is widening, with the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC at 30 June 2020 being 11 times that of non‐Indigenous children. Approximately, one in five Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children entering OOHC each year are younger than one year. These figures represent compounding intergenerational trauma and institutional harm to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities. This article outlines systemic failures to address the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents during pregnancy and following birth, causing cumulative harm and trauma to families, communities and cultures. Major reform to child and family notification and service systems, and significant investment to address this crisis, is urgently needed. The Family Matters Building Blocks and five elements of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (Prevention, Participation, Partnership, Placement and Connection) provide a transformative foundation to address historical, institutional, well‐being and socioeconomic drivers of current catastrophic trajectories. The time for action is now.

Keywords: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, child and family services, intergenerational trauma, out‐of‐home care, prenatal notifications

1. INTRODUCTION

Prior to colonisation, evidence suggests that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were likely to be physically, socially and emotionally healthier than European children in 1788 (Thomson, 1984). New parents were supported using principles of “Grandmothers' law” (Langton, 1997; Ramsamy, 2014). The safety and well‐being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children was fostered within systems of kinship and community care (McMahon, 2017). Since colonisation, systemic violence, removal from lands, suppression of cultural practices, racism and discrimination have caused suffering, illness and death – leaving a legacy of trauma impacting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Atkinson, 2002). This systemic violence includes the forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, known as the “Stolen Generations” (Wilson, 1997), which has disrupted vital kinship systems and impacted the capacity of affected parents to provide nurturing care (Chamberlain, Gee, et al., 2019). The interface between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and governments is beleaguered by poor relationships, fragmented responsibility and conflicting priorities, all of which perpetuate inequities. The World Health Organisation's framework (Marmot et al., 2012) for understanding the causes of health inequities demonstrates how historical violence and family disruption lead to compounding cycles of intergenerational trauma (Chamberlain, Gee, et al., 2019) and childhood adversity, with major impacts on lifelong health (Anda et al., 2010; Felitti et al., 1998; Hughes et al., 2017), well‐being and prosperity (Henry et al., 2018).

In 2007, all Australian governments signed a commitment to Closing the Gap in life expectancy by improving health outcomes and equity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with progress against key targets reported annually to Parliament. Recognition of the critical importance of early life experiences to improving health and supporting families to provide nurturing care (Britto et al., 2017) is a core element of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plan (Department of Health, 2013), developed to guide efforts for Closing the Gap. In July 2020, a new National Agreement on Closing the Gap was signed and, for the first time, was formed as an agreement between governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peak bodies. This agreement included 17 national socioeconomic targets across areas that have an impact on life outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, including a target of reducing the rate of over‐representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out‐of‐home care (OOHC) by 45 per cent by 2031 (SNAICC, 2020). Redressing compounding cycles of intergenerational trauma, a legacy of colonisation, will be central to achieving this target.

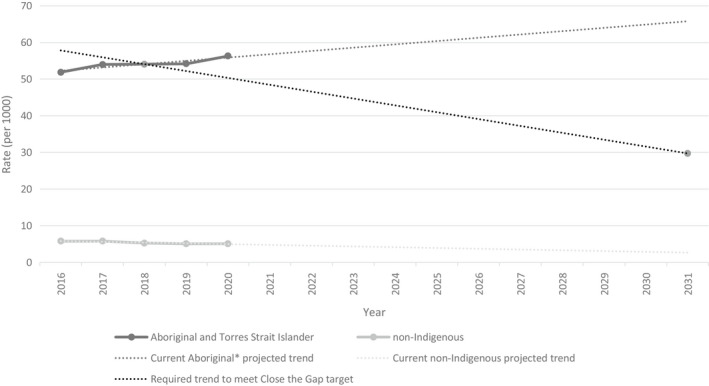

However, current trends demonstrate that rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC are continuing to increase, and were 11 times that of non‐Indigenous children on 30 June 2020 (Figure 1) (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2021; Productivity Commission, 2021). While future projections based on current trends are limited, if current trajectories continue, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children will be over‐represented in OOHC by more than 20 times that of non‐Indigenous children in 2031 (see illustration of projections in Figure 1). The Family Matters report estimate that, without urgent action, the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC is projected to double by 2029 (SNAICC, 2020).

FIGURE 1.

Australian children in out‐of‐home care at 30 June each year, by Indigenous status, with projections based on current trends

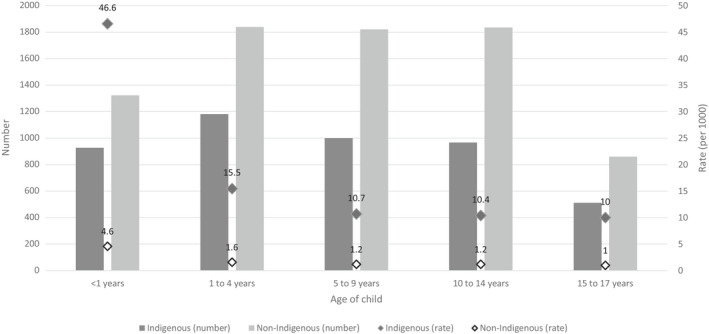

A major contributor to these trends is the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children being removed into OOHC shortly after birth or before one year of age, often with notifications to child protection services (CPS) before the child is born. During 2019–2020, one in five Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children admitted into OOHC were less than one year of age – at a rate of 46.6 per 1000 children, more than ten times the rate of non‐Indigenous infants at 4.6 per 1000 children (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2021) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Australian children admitted into out‐of‐home care, 2019–2020, by age group and Indigenous status. Data were extracted from AIHW Child Protection Australia data tables (2019–2020) (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2021)

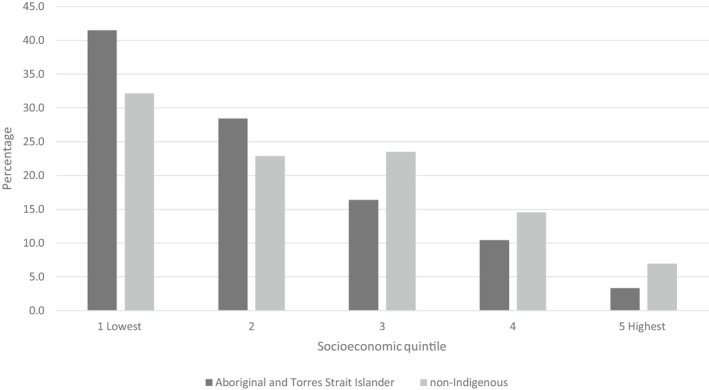

The AIHW data highlight the importance of socioeconomic inequities, which are obscured in many other representations of these sensitive data. In 2019–2020, rates of substantiations (i.e. the conclusion, following an investigation of a notification, that there was reasonable cause to believe that a child had been, was being or was likely to be, abused, neglected or otherwise harmed) followed clear inequities across socioeconomic areas (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2021) (see Figure 3). The socioeconomic gradients in substantiations were more evident among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Socioeconomic inequities are often obscured in public health data, and it is vital that the root causes of any social or health issues are clearly illuminated, understood and addressed (Thurber et al., 2021).

FIGURE 3.

Children who were the subjects of substantiations, by socioeconomic area and Indigenous status (percentage), 2019–2020

Outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children admitted to OOHC in Australia are very concerning. The Our youth, our way: Inquiry into the over‐representation of Aboriginal children and young people in the Victorian youth justice system report outlines a trajectory from OOHC to the youth justice system and finds significant failings of child protection and OOHC systems, in particular residential care (Commission for Children & Young People, 2021). The physical, developmental and psychological health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC is also of significant concern (Shmerling et al., 2020). More broadly, in a longitudinal study of young Australians, 37.5 per cent reported that they had attempted suicide within four years of leaving OOHC (Cashmore & Paxman, 2007). Children removed from their parents often also experience lifelong interactions with child protection and justice systems, entrenched disadvantage and institutionalisation and disconnection from culture, community and family (Herrman et al., 2016; Tune, 2017).

The current situation can only be described as a national crisis, reflecting systemic failures, discrimination, impacts of colonisation and harmful policies (O'Donnell et al., 2019). In her Family is Culture report, Professor Davis questions whether Australia is meeting its obligations as a United Nations member and signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Davis, 2019), and to child welfare legislation in maintaining the best interests of the child and the integrity of Indigenous families and communities.

In this paper, we outline concerns about systemic and CPS failures regarding meeting the needs of parents experiencing social and/or emotional complexity. We argue for urgent reform and call for action for substantial investment to alter these trajectories. Our argument is bound within evidence‐based and culturally informed expertise and calls for health, social and welfare systems and their epistemological foundations to be transformed to support success rather than failure for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families.

Systemic failures that do not address the needs of parents experiencing social and emotional complexity:

Increasing number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC, separated from families, communities and culture. This does not reflect the intent of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (Davis, 2019; Guthrie et al., 2020; SNAICC, 2019, 2020) or the Australian Government Closing the Gap commitments (Australian Government, 2021).

Child Protection Services (CPS) are a significant barrier for parents accessing support to prevent family disruptions and trauma for the child. Guidelines to support pre‐birth involvement of CPS have been implemented in most Australian jurisdictions, ostensibly to enable early support for parents to prevent family disruptions and trauma for the child (Harrison et al., 2016; Taplin, 2017). Yet, fear of CPS remains a significant barrier to parents accessing support (Langton et al., 2020). CPS notifications can be triggered by a wide range of “potential risks” to the unborn child, contributing to sharp increases in infant removals in the past decade (Wise & Corrales, 2021). For example, in Western Australia, pre‐birth involvement of CPS can be triggered by a previous child being notified to the department; a family member being convicted of an offence against a child; drug and alcohol use; serious mental illness; family and domestic violence (FDV); the young age of a mother; cognitive impairment; homelessness; or the mother being in care. These blunt “screening” measures often lack specificity, which can lead to a high number of “false positives”, with significant harm caused to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. Recent analysis in New South Wales (NSW) noted that “almost 1 in 10 Aboriginal children in NSW, who entered Kindergarten in 2012, were subject to a [risk of significant harm] report before they were born” (Davis, 2019). Critically, there is no evidence whether prenatal reporting leads to improved provision of acceptable and effective support, improved outcomes for the child and mother (SNAICC, 2019), and whether it reduces the likelihood of the child being removed at or shortly after birth (Davis, 2019).

Coercive practices are overused by maternity and CPS with risk of harm and triggering of protective “threat” responses. Experts raise concerns that, in many instances, there is a risk of more harm than benefit of “interventions” for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and parents. For example, an increased focus on FDV is important, but within the context of pregnancy, this attention can be used as an additional “weapon” against mothers experiencing FDV (Langton et al., 2020). The ultimatum of requiring mothers to leave the relationship, or have her child removed, is often experienced as further systemic violence, rather than “care” supported by CPS. Perversely, threats of removal and increasing fear of losing a baby are more likely to decrease disclosure of FDV, potentially putting lives at greater risk (Langton et al., 2020). Further, there is substantial evidence to demonstrate the benefit and importance of keeping parents and their children together safely through addressing the perpetration of FDV (Cramp & Zufferey, 2020; Humphreys et al., 2020). The Power Threat Meaning Framework explains how we have learned as human beings to respond to threats that misuse power (Johnstone et al., 2018). Natural survival responses (e.g. fight, flight or freeze) are more easily reactivated or “triggered” in people who have experienced previous trauma (Blue Knot Foundation, 2021; Kozlowska et al., 2015). These “threat” or “stress” responses can negatively impact upon both maternal and foetal health (Sandman & Davis, 2012) and maternal behaviour – increasing risk and creating a harmful and dangerous reinforcing spiral. “Safety” during pregnancy and birth is critical for parents, yet antenatal health support is considered “unsafe” by many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents – because of the fear of interventions by CPS, lack of cultural safety, racism and other factors (Varcoe et al., 2013). Whatever the reason for the CPS notification, the heightened fear can also lead to reduced engagement with antenatal care, posing further risks to the unborn baby and mother during pregnancy (Sandman & Davis, 2012). Paradoxically, in some instances, a parent not attending antenatal care has been reported as grounds for CPS notification. This is despite antenatal care attendance being recognised as a woman's choice (Clinical Excellence Queensland, 2020).

Systemic racism and discrimination are inherent in CPS involvement (Edwards et al., 2021 ). “Risk factors” can trigger a prenatal CPS notification, and many are directly related to intergenerational trauma and the ongoing impacts of colonisation and socioeconomic deprivation (including homelessness), reflecting systemic racism. Governments and CPS fail to recognise that sustained racism and overwhelming numbers of children removed from families over generations represent cumulative harm of the system on individuals. Instead, these authorities blame the individual victims. Lack of engagement with CPS is a major “reason” for infant removal; however, the historical legacy of government policies has driven distrust of government, resulting in a lack of engagement. Yet, government services fail to take any responsibility for this situation, leaving vulnerable families to bear full responsibility with catastrophic consequences. Policy directives of statutory CPS and “regulatory ritualistic responses” (Davis, 2020) that determine practice within pregnancy and early parenting care settings mean that these factors related to systemic racism are, for too many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents, portrayed primarily as risks of harm to the unborn child (Harrison et al., 2016), rather than as social and emotional needs for support. Homelessness is a clear example of structural factors having a profound impact on families (Aboriginal Housing Victoria, 2020), which can be used as a rationale for removing children. This needs to be addressed by upstream policies.

Removal of infants shortly after birth occurs without acceptable and effective support being provided to the parents, despite CPS notification in pregnancy. Too often this occurs, without prior discussion with the parents, which is referred to within service systems as an “undisclosed infant removal” (Davis, 2019; Marsh et al., 2019; SNAICC, 2020). This unacceptable practice denies parents' information and opportunities for agency regarding their healthcare and the welfare of their infant, their right and opportunity for love, healing and recovery, and access to effective evidence‐based therapeutic support. Further, it runs counter to laws and “best practice principles” related to child protection about the need to give the widest possible protection and assistance to the parent and child, and to preserve culture. It also compounds lack of trust in the system for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents and denies their right to be involved in CPS decision‐making processes about the best interests of their infant.

There is inadequate culturally safe therapeutic support available for parents with complex social and emotional needs. The World Health Organisation defines health as a “state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (World Health Organisation, 1946). Healthcare services can excel in addressing a wide range of complex and emergent physical health issues (e.g. caring for preterm babies and the response to novel coronavirus). Yet, complex social and emotional health issues experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are too often classified as “risk factors” and parents are referred “out” of health services to CPS for “support”, rather than providing culturally safe social and emotional healthcare. In a national survey of perinatal care providers, 98 per cent identified trauma, stress and grief as significantly impacting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers, yet almost half (43 per cent) did not feel satisfied with the ability of their service to address these issues (Highet & Goddard, 2014).

Vulnerable parents with complex social and emotional needs are “re‐victimised” by the system, with limited or no therapeutic support provided to them after the highly traumatic and psychologically damaging experience of having their baby taken from them (Davis, 2019).

CPS and maternity service documentation of unborn notifications are often poorly recorded and not consistent with accepted professional standards, resulting in poor data for oversight and accountability (Davis, 2019). In some jurisdictions, such as Victoria, the Aboriginal Child Specialist Advice and Support Service (ACSASS) must be consulted at every point in CPS decision making, involving an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander child. However, mandatory requirements are not always followed, family engagement is poor, and decision‐making power still rests with CPS. Too often, critical decisions impacting the lives of vulnerable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families are made without sufficient transparency, accountability, expertise, evidence and evaluation – and critically without adequately engaging parents in the process or considering the family's support needs as a priority, despite legislative and policy mandates.

- Healthcare providers, family support workers and police are exposed to a risk of “moral injury”. Moral injury is defined as “the strong cognitive and emotional response that can occur following events that violate a person's moral or ethical code” (Williamson et al., 2021). Working within a system that harms families and does not address the complex social and emotional needs of parents places all workers at risk. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers (Davis, 2019) and young inexperienced workers (Shergill, 2018) providing direct support to mothers, babies and families are at the highest risk of “moral injury”. As well as being a serious workplace safety concern, this is likely to decrease the capacity to recruit and retain the workforce, particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers, many of whom are impacted by trauma in the legacies of colonisation. As Professor Davis notes in the Family is Culture Report:Newborn removals also pose ‘clinical, moral and ethical challenges’ for midwives, who in some circumstances question the need for the removal and resent being unable to inform the mother of an impending assumption of care. Midwives can also be frustrated at the lack of opportunity to collaborate with the [child protection] department to ensure the safety and wellbeing of the mother and her child. (Davis, 2019)

Unjust treatment of and discrimination against parents who are incarcerated are widespread. However, while access to data relating to highly vulnerable incarcerated parents is difficult to obtain (Dowell et al., 2018), the Family is Culture report noted that a mother's application to care for her newborn in a safe and supervised environment was denied as CPS had failed to complete a safety and risk assessment prior to the child's birth (Davis, 2019). There are limited understandings of the rights of children to be with their parents and family, and very limited opportunities to support the rights of incarcerated parents to have time with their babies. This is despite a unique opportunity to provide full‐time live‐in support, away from potentially dangerous environments and harmful influences that may have contributed to the parent being incarcerated. [Correction added on 15 February 2022 after first online publication: The word “and this” was replaced in the sentence with “that” to read as (that may have contributed.…] Evidence demonstrates that prison‐based programmes have positive outcomes for both mothers and infants (Shlonsky et al., 2016). Further evidence from longitudinal studies in the United States demonstrates that becoming a parent is the most significant lifecourse opportunity for people involved with the justice system from a young age, for recovery and escape from a trajectory of extremely poor social and emotional well‐being (Abram et al., 2017).

The interacting factors identified above have devastating and disproportionately compounding effects on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, which in turn is used to justify policy interventions (Harrison et al., 2016). For example, previous involvement with CPS places parents at higher risk of future intervention; women who are victims of family violence are “blamed” or made responsible for keeping their children safe from a violent partner or family member. Such policy positions reinforce, and are reinforced by, dominant discourses that cast difficulties that can be experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents through a frame of pathologisation and/or criminalisation, supporting racist and discriminatory undertones that permeate the helping professions in community and statutory service systems (Bond, 2017). While these quotes below relate to NSW, the issues, as outlined in the Family is Culture report by Professor Davis (2019), strongly resonate with our authorship team.

Newborn removals are highly traumatic for the birth parents, with birth mothers recounting feelings of shock, pain, sorrow, disbelief, anxiety, guilt, shame and emptiness upon the removal of their babies. Birth mothers and fathers are left to live in an ‘in‐between state where their child is gone but did not die’, and the complexity and depth of their grief can lead to serious and longstanding psychological damage. This may then have a significantly detrimental effect on their later experiences of pregnancy and parenthood. It is widely recognised in the literature relating to compulsory child removals that many women suffer ‘a downturn in functioning’ post removal. Anecdotal evidence indicates that women may ‘seek comfort in a further pregnancy’. This may lead to successive removals of newborns from the woman's care. (Davis, 2019)

This state of affairs is unacceptable, falling far short of human rights standards and the ethical requirements of professional staff involved. Social work, maternity and early parenting support services are directly implicated in practices, which contribute to complex trauma and must take responsibility for redressing these. The current situation facing too many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families is immensely harmful to babies and their families, is therapeutically unsound and unsupported by evidence, and compounds rather than resolves cycles of intergenerational trauma and disadvantage for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Safe, fair, therapeutically sound and effective alternatives are available.

1.1. Call for action

There is unanimous agreement that the safety, love and nurturing of children are paramount (Department of Social Services, 2018). This debate centres on the ways in which safety, love and nurturing can and should be ensured.

Pregnancy and the first year after birth is a unique opportunity for therapeutic intervention, which is different from normal life circumstances. Evidence shows that the transition to parenting is a time of optimism and hope, offering a unique lifecourse opportunity for healing and recovery, even after severe trauma (Chamberlain, Ralph, et al., 2019). It is a known state of heightened psychological malleability thought to be partly due to hormonal changes necessary for pregnancy and attachment (Kim, 2021). Supporting parents to provide nurturing care (Britto et al., 2017) can foster a “virtuous cycle” of mutually reinforcing love, which fosters recovery from trauma through a process known as “earned security” (Segal & Dalziel, 2011). This is a key opportunity for interrupting cycles of intergenerational trauma, reducing the rate of infants admitted to OOHC, and changing current trajectories to reduce over‐representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC. Effective preventive interventions will also reap substantial cost savings in the high direct and indirect costs of OOHC.

The Family Matters Building Blocks (SNAICC, 2016) and five key elements of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (Prevention, Participation, Partnership, Placement and Connection) (SNAICC, 2019) provide an organising framework to coordinate a comprehensive response, with children and families at the centre. [Correction added on 15 February 2022 after first online publication: The plural form was deleted for the word “Partnerships” to read as “Partner”] We outline examples of actions under each of the child placement principles below.

-

Prevention

Redesign maternity and neonatal services to ensure all parents have access to culturally responsive, trauma‐integrated experienced support during pregnancy, birth and early postpartum (Kildea et al., 2019). This must include community‐led, continuity‐of‐care models, which studies show can dramatically increase attendance and engagement in antenatal care – and reduce preterm births by 50 per cent (Kildea et al., 2021). Building trusting relationships between parents and professionals is the key feature of these models, which enables effective two‐way communication to enable understanding of complex social and emotional needs, and ability to access skilled therapeutic care and practical support. These culturally responsive models of care should include trauma‐integrated approaches, such as:

Resources to help parents understand and learn about parenting, cultural ways of fostering children's social and emotional well‐being, the effects of trauma, practical strategies to help and culturally safe support services available.

Access to holistic, culturally acceptable support services to foster empowerment and self‐care, offer compassionate care and support, build connections, provide parent education and opportunities to develop skills, provide practical assistance and support to develop life skills, reduce isolation and offer a range of healing and therapeutic approaches (Arabena, 2014; Austin & Arabena, 2021).

Education for care providers to build expertise in culturally responsive trauma‐integrated care. This includes standard training approaches to develop baseline skills and competencies, and also mentoring and supervision to build expertise and wisdom to enable best practice in supporting parents with complex social and emotional needs (Chamberlain et al., 2016). Incorporating and relearning Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of communicating effectively about sensitive issues, including using Dadirri, yarning and story‐telling, are critical (Chamberlain et al. 2020).

-

Partnership

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities must drive the development and implementation of culturally embedded models of care for new and expectant parents, including service design and administration, Aboriginal Family Led Decision Making models (currently being evaluated in NSW and Western Australia) and other supports. Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations should lead the design and delivery of systems, services and practice. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have demonstrated the capacity to lead highly effective crisis responses during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Crooks et al., 2020) and are best placed to lead a comprehensive response to this complex issue (Chamberlain et al., 2016). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐led, preventive services and solutions are highly cost‐effective (Harris‐Short & Tobin, 2019). Economic reports on the effectiveness of preventive, community‐led services demonstrate significant increased returns on investment for vulnerable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families (SNAICC, 2020).

-

Placement

Where parents are identified as needing more intensive support, all alternatives to removing the child must be explored. This includes practical, timely and active support to address risks associated with structural inequities and socioeconomic deprivation, such as housing. This could also include enabling access to culturally safe high‐quality childcare and other necessary family supports over the perinatal and early childhood period (Sandner & Thomsen, 2018), such as the Bubup Wilam Aboriginal Child and Family Centre in Melbourne. There is a need for urgent investment in developing and evaluating pilot interventions for culturally safe, high‐quality live‐in supported parent accommodation, co‐designed with communities, which offer safe nurturing healing support. Examples such as the He Korowai Trust (2021) in Aotearoa demonstrate that this can be an acceptable strategy to provide full‐time live‐in support, and research to develop and trial these strategies is urgently needed. Using the unique opportunity to provide full‐time live‐in support for incarcerated parents to care for their infants is another important strategy to develop and evaluate a pilot programme.

-

Participation

Parents, families and communities must be at the centre of child protection decision making. Discussions and decision making must be transparent and open with the family in the presence of a chosen support person (e.g. Waminda's Program [NSW] and Aboriginal Family Led Decision Making pilot (Western Australian Government, 2021)), including identification of family or kin to provide care. Under no circumstances should any plans be made with hospital staff for infants to be removed from families' care without discussion and preventive plans being made with the parents and families (Marsh et al., 2019). An ethical approach demands that parents are entitled to information and opportunity for engagement in support and care and involvement in decisions about the best interests of their child. In every health service providing evidence‐based care, it is an expectation that service providers will identify risks, and strategies to mitigate these risks. The prevailing argument supporting the practice of deception around unborn CPS reports and newborn removals is that informing the parent may increase the risk that they withdraw from or try to leave maternity care (Davis, 2019). However, deeming parents to be a “flight risk” is not a justifiable rationale supported by evidence (Davis, 2019, p.189). The risk of flight and trauma is far greater where there is deception (Davis, 2019). There is no evidence that deceiving parents about plans to forcibly take their baby after birth reduces the risk of parents leaving hospital early. Rather, open, honest, transparent systems of support would allow parents and families to participate in the development of clear and attainable options.

Consideration should be given to essential development and evaluation of a pilot model of care where CPS and perinatal care providers work together under the leadership of Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (The Victorian Aboriginal Children and Young People's Alliance, 2019) to develop comprehensive support plans and foster accountability, transparency and professional practice in planning support in the presence of a chosen support person (e.g. Aboriginal Family Led Decision Making). These are consistent with a therapeutic justice model of care (Marsh et al., 2019), which includes expertise and community “wise counsel” to foster access to appropriate support and ensure that complex decision‐making processes are transparent. This will help to ensure the best possible decisions are made with members of families, to increase trust in the system and build the evidence base needed for supporting parents with complex social and emotional needs. Further, close connection and intimate knowledge of the family would not be lost.

Any notification should be accompanied by an assessment of needs and a support plan to reduce risk and provide the appropriate level of therapeutic intervention required to promote successful outcomes, whether this be for mental illness, drug use, violence, trauma or disability. The focus during this critical parenting transition should be on the current situation, rather than past concerns (The Victorian Aboriginal Children and Young People's Alliance, 2019). This is particularly salient for young parents exiting the OOHC system themselves, who frequent express fervent desire for a “fresh start” and “parenting differently” (Chamberlain, Ralph, et al., 2019). Support services must provide practical strengths‐based structural and economic support for parents to achieve these hopes and dreams of having a happy, healthy family.

-

Connection

Where infants are removed from their parents by CPS, it is vital to ensure ongoing support for parents and families to strengthen relationships, address identified concerns and enable timely reunification. Culture remains a key feature of well‐being and resilience (Gee et al., 2014). All children have a fundamental right to connect to their family, community and culture (Harris‐Short & Tobin, 2019; Krakouer et al., 2018; United Nations, 1989). Strategies may include ensuring parents are provided with keepsakes and ways of promoting bonding with their baby (e.g. photographs, updates, clothes), support to express breastmilk if they choose to do so, and emotional support that includes fostering supportive connections. Contact arrangements need to be established as early as possible to enable connection for children to families. It is important to work holistically with the whole family to ensure that extended family and community supports are available to parents. This may include asking parents for permission to contact extended family members for support purposes, in line with culturally appropriate collective child‐rearing practices.

2. CONCLUSION

The current system continues to fail, and perpetuate harms inflicted on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. Culturally unsafe, inappropriate and unvalidated “risk assessment” measures; punitive approaches that prevent access to care; lack of highly skilled, trained staff to support vulnerable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families; poor quality ineffective unacceptable therapeutic support options; and an absence of rigorous evaluation and evidence are driving alarming and worsening outcomes in removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies from their families. We must build the skills and resources to address compounding effects in this critical “window of opportunity” so that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities can ensure the safety and well‐being of their children.

We must commit to open and courageous truth‐telling about current child protection systems and practice, to ensure the safety and well‐being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and children. There is a need for urgent reform to take meaningful active steps to fully implement the intent and recommendations of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (SNAICC, 2019), Family Matters Report 2020 (SNAICC, 2020) and Family is Culture report (Davis, 2019). We must maximise therapeutic outcomes and promote therapeutic, evidence‐based, community‐led, culturally responsive, trauma‐integrated interventions and practices. This includes identifying feasible alternatives to removing babies from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents after birth and investment in immediate implementation and evaluation.

We recognise the complexities and challenges in achieving urgently needed change in this arena of policy and practice. Dealing with complexity in perinatal care is not new. For millennia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have had systems for mentoring maternity care workers (traditional midwives and healers) to develop and provide technical and emotional expertise, with integrated referral systems. Perinatal services now have more trained “experts” than ever. Yet, parents experiencing social and emotional complexity are referred from the therapeutic health sector to the CPS statutory sector for “support”. We argue this creates barriers for parents accessing effective support and is punitive rather than therapeutic. If CPS involvement is required, it should be “brought in” as a participant in the multidisciplinary culturally responsive therapeutic care team to contribute to transparent shared decision‐making processes with the family.

Research is urgently needed to develop and evaluate safe, acceptable and effective responses for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families that ensure the benefits of any pre‐birth support outweigh the harms and identify systemic structural issues beyond NSW. This research must be led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and researchers. It must also consider the rights and needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies, parents and families, engaging with care providers, government child protection practitioners and policymakers.

Addressing complex social and emotional needs is as challenging as addressing physical needs and is critical in the perinatal period – with strategies to improve culturally safe social and emotional care involving family support workers shown to have a significant impact on physical outcomes such as preterm births (Kildea et al., 2021). Similar investments of resources and expertise are required to achieve similar levels of success in terms of better outcomes and the associated cost savings in relation to care and support for infants and parents.

Achieving these reforms will not be easy. It requires a fundamental shift in the relationships between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, health services and CPS, with families at the centre. Self‐determination for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities needs to be actualised – to enable communities to reassert systems of kinship and community care that foster the safety and well‐being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Health services need to work with communities to develop therapeutic models of care to support families with complex social and emotional health needs. Also, CPS need urgent reform – to enable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to design and administer systems grounded in their values, perspectives and aspirations, and through them promote transparent, compassionate and healing‐focused practice with families that is consistent with social justice and reduces the incidence of moral injury. The quality of life of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children caught in the CPS system depends on it, as do their prospects of a full life term. True reconciliation begins here.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge SNAICC – National Voice for our Children – for their leadership and advocacy in this field. We are also grateful to the SAFeST Start group members for supporting the development of this position statement and to the families, frontline workers and other advocates working to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families to stay together from the start. Catherine Chamberlain is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship (1161065). Research at the Murdoch Children's Research Institute is supported by the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

Biographies

Catherine Chamberlain is a Trawlwoolway Palawa woman from Tasmania and Professor of Indigenous Health at the Centre for Health Equity, the University of Melbourne, and Registered Midwife and Public Health Researcher with more than 25 years of experience in maternal and child health. Her research aims to improve health equity. She currently leads the Healing the Past by Nurturing the Future Project, which aims to co‐design perinatal awareness, recognition, assessment and support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents experiencing complex trauma.

Dr Paul Gray is a Wiradjuri man from NSW and Associate Professor at the Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research, UTS, where he leads the child protection research hub. Paul is committed to reimagining child protection systems and practice to end their disproportionate impact on our children, families and communities and promote healing. He also serves as Co‐chair of the SNAICC Family Matters National Leadership Group.

Debra Bennet is a Goorie Woman, a direct descendant of the Kullali peoples (of South Western QLD) and Wakka Wakka and Gubbi Gubbi peoples (of South East QLD). With 28 years of successful community and cultural development experience, Debra has held various roles in the art sector, disability sector, correctional centres and adult education arenas. Debra is currently employed as Director of Indigenous Services with Relationships Australia (QLD).

Alison Elliott Clinical Family Therapist and Workforce Development Trainer and Team Leader of the Indigenous Team, the Bouverie Centre, La Trobe University. Alison has family connections to Wiradjuri Country and Celtic heritage, and she grew up in Dharug Country (Hawkesbury River NSW). She is involved in the Healing the Past by Nurturing the Future Project and is Lead Facilitator for We Al‐li, which provides Culturally Informed Trauma Integrated Healing Approach (CITIHA) training to individuals, families, communities and organisations.

Marika Jackomos is a Yorta Yorta, Greek and African American woman and Manager of Aboriginal Programs for Mercy Hospitals Vic. She has more than 20 years of experience working in tertiary and primary health.

Jacynta Krakouer (BSc, MSW, MSP Melb) is a Mineng Noongar academic whose teaching and research expertise centres on child and family welfare, particularly with Indigenous peoples. She is a Research Fellow at the Health and Social Care Unit at Monash University. Undertaken at the University of Melbourne in the Department of Social Work, Jacynta's PhD thesis explores Indigenous people's understandings of cultural connection for Indigenous children and young people in out‐of‐home care in Victoria, Australia.

Professor Rhonda Marriott AM is a Nyikina woman from the Kimberley and Director of the Ngangk Yira Research Centre at Murdoch University. A Registered Nurse and Midwife, she leads a research programme based on co‐design with the community for authentic, meaningful research evidence. She led the Birthing on Noongar Boodjar Research Project, which produced critical recommendations for translation to midwifery practice. With Aunty Doreen Nelson, she co‐edited Ngangk Waangening (Mothers' Stories) of 12 elders and senior women's stories of childbirth.

Birri O'Dea is a Kungalu and Birri–Gubba (Wiri) woman, whose work is focused on improving outcomes for pregnant urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Her current PhD research explores how an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander‐specific maternity service could potentially help reduce statutory child removals at birth. Birri has a Master of Public Health (MPH) degree and wrote her thesis on cultural safety in maternity care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in an urban setting.

Dr Julie Andrews is descended from the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung people and is a member of the Yorta Yorta Dhulanyagan family clan of the Ulupna people. Dr Andrews is an anthropologist and researches urban Aboriginal communities, families and socio economic elements contributing to Aboriginal advancement. She is Convenor of Aboriginal Studies and is Co‐Chair of the Aboriginal Studies Indigenous Strategy committee.

Shawana Andrews is a Trawlwoolway Palawa woman of north‐east Tasmania and Associate Professor at the University of Melbourne. She is Director of the Poche Centre for Indigenous Health and Senior Academic Specialist in the Department of Social Work. Shawana is a Social Work and Public Health Researcher in the areas of Aboriginal mothering practices and family violence, Aboriginal feminisms and gendered knowledge, and cultural practice‐based methodologies.

Caroline Atkinson is a Bundjalung and Yiman woman and Accredited Social Worker with a PhD (Charles Darwin University, 2009). Dr Atkinson is International Leader in complex and intergenerational trauma and culturally informed strengths‐based healing approaches in Indigenous Australia. She is CEO of her family organisation, We Al‐li, designing and coordinating the delivery of Culturally Informed Trauma Integrated Healing Approaches (CITIHA) training and resource development for organisations and communities across Australia focusing on system transformation and implementation.

Emeritus Professor Judy Atkinson (AM) is an Aboriginal Australian Jiman /Bundjalung woman, who also has Anglo, Celtic and German heritage. Currently, patron of We Al‐li Pty Ltd and working across community‐based trauma‐specific recovery programmes, she is Internationally Renowned Leader in intergenerational trauma and has over 35 publications in the field. She has been awarded the Carrick Neville Bonner Award for her “educaring” programmes and the prestigious Fritz Redlich Memorial Award for Human Rights and Mental Health.

Alex Bhathal (MAASW, MA, BSW Hons 1) is a Qualified Social Worker and Lecturer in Social Work and Social Policy with La Trobe University. Alex previously worked with SNAICC – National Voice for Our Children as National Manager of Family Matters, the campaign to end the over‐representation and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in child protection. She has worked in child protection and out‐of‐home care services in two jurisdictions.

Gina Bundle is a Yuin/Monaro woman and Program Coordinator of Badjurr–Bulok Wilam Program at the Royal Women's Hospital.

Shanamae Davies is a proud Kaurna/Ngarrindjeri/Narungga woman with 10 years of experience as an Aboriginal Maternal Infant Care (AMIC) practitioner in South Australia. She has experience in both Aboriginal community‐controlled and mainstream health services providing quality perinatal care to Aboriginal women, babies and their families. She is a strong advocate for the women in her care, for culturally safe, family‐centred care. She is in her final year of midwifery study.

Helen Herrman AO is Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at Orygen and the Centre for Youth Mental Health, the University of Melbourne, and Director of the World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre in Mental Health, Melbourne, Australia. She is appointed Officer of the Order of Australia and is Former President of the World Psychiatric Association and the International Association of Women's Mental Health. Her research and development interests include promoting mental health, community mental healthcare and women's mental health.

Sue Anne Hunter is a proud Wurundjeri and Ngurai Illum Wurrung woman, and Child and Family Services Practitioner who has focused her career around using culture as a foundation for healing trauma, and addressing the impacts of colonisation on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and their families and communities. She is currently Yoo‐rrook Justice Commissioner.

Glenda Jones‐Terare is the CEO of Kurbingui Youth and Family Development, an Aboriginal Community Controlled Not for Profit organisation that provides services to communities throughout Greater Brisbane, Moreton Bay and Southeast Regions. Glenda‘s professional experience extends to working with Traditional Owners / Elders and community members throughout the Western Cape, Woorabinda, Far North, Central, North, and Southeast regions of Queensland, establishing and implementing support services. [Correction added on 15 February 2022 after first online publication: Glenda Jones‐Terare’s author biography was updated. It previously read: Glenda Jones‐Terare is a Chief Executive Officer of Kurbingui Youth and Family Development, Queensland. Glenda holds a Bachelor of Social Science with a Major in Psychology, a Graduate Diploma in Communication (Business), a Master of Business in Communication Studies, a Diploma in Community Development and a Certificate in Childcare, and is currently undertaking a Graduate Diploma of Strategic Leadership. She has also undertaken significant professional development, training and community consultations in various areas of community services.

Cathy Leane is a Dharug woman, mother, grandmother and carer. She has more than 20 years of experience working in early childhood services. Previously, she was Senior Policy Advisor for the South Australian Department of Premier and Cabinet. Her expertise includes policy development, implementation and research with a whole of government perspective. Her current role with Women's and Children's Health Network includes coordination of research partnerships, research translation and community engagement.

Dr Sarah Mares is an Infant, Child and Family Psychiatrist with more than 30 years of clinical and academic experience with infants, young children and their families, particularly those facing complex adversity and risk. She is an Adjunct Senior Lecturer in the School of Psychiatry at the UNSW.

Dr Jennifer McConachy is a Social Worker and Academic at the University of Melbourne. She has worked with children and families, mostly within the child protection system for over 30 years; and was instrumental in bringing the concept of family finding to Australia. Her PhD focused on state government‐level policy for involving extended family with family support services as an essential system and cultural change to keep children connected to and living within their kith and kin network.

Dr Fiona Mensah is a Senior Research Fellow in Epidemiology and Biostatistics with the Intergenerational Health Group at the Murdoch Children's Research Institute. Her research focuses on the social health of families and children. Centred in pregnancy and early childhood, her research seeks to redress impacts of adversity for families by provision of culturally informed strengths‐based healthcare. She co‐leads community‐based studies including longitudinal cohort studies, randomised controlled trials, and whole of system evaluations of policy and quality improvement.

Catherine Mills is Professor of Bioethics and the Director of the Monash Bioethics Centre, Monash University. Her research addresses ethical, social and regulatory issues in human reproduction. She currently leads research projects funded by the ARC and MRFF and participates in a project funded by the NHMRC.

Dr Janine Mohammed is a Narungga–Kaurna woman from South Australia and currently CEO of the Lowitja Institute, Australia's National Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research. She has more than 20 years of experience working in nursing, management, project management, research, workforce and health policy in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Awards include an Atlantic Fellowship for Social Equity (2019), a Doctorate of Nursing (2020) and a Distinguished Fellowship by the George Institute for Global Health Australia (2021).

Lumbini Hetti Mudiyanselage is a Bilingual and Culturally Diverse Social Worker and Case Manager with the Victorian Aboriginal Childcare Agency (VACCA).

Melissa O'Donnell is Deputy Director at the Australian Centre for Child Protection, University of South. Melissa is Internationally Recognised Researcher in the area of child maltreatment and has utilised population‐level linked data to contribute new knowledge and evidence. The main focus of research includes the following: risk and protective factors for child maltreatment; outcomes for children in care; and infant removals by child protection. Melissa collaborates with government and non‐government partners to ensure the translation of research into policy and practice.

Dr Elizabeth Orr Liz has worked alongside diverse community‐based projects to improve prevention strategies and service responses for women and children affected by all forms of violence, inequality and exclusion (e.g. racism, poverty). She was a recipient of a Lowitja Institute PhD scholarship for her thesis “Stories of Good Practice from Aboriginal Hospital Liaison Officers and Social Workers in Hospitals in Victoria”, which was awarded the Nancy Millis Medal at the La Trobe University in 2018.

Professor Naomi Priest is a Lifecourse and Social Epidemiologist. She is Group Leader of Social‐Biological Research at the Centre for Social Research and Methods, Australian National University, and Honorary Fellow at the Murdoch Children's Research Institute. Professor Priest's research programme focuses on examining how social forces and social exposures become biologically embedded and embodied, and on understanding and addressing inequalities in health, social determinants of health and health inequalities for children and youth, throughout the lifecourse.

Professor Yvette Roe is a Proud Njikena Jawuru woman from the West Kimberley, WA. She has more than 30 years of experience working in Indigenous health and is Emerging Nationally and Internationally Known Leader on Indigenous health. A Co‐Director of the Molly Wardaguga Research Centre, Charles Darwin University, she has devoted herself to be a two‐way interpreter of research between the academy and First Nations people and to use research as a mechanism for structural, social, cultural and political change.

Dr Kristen Smith is Senior Research Fellow and Research Director of the Indigenous Studies Unit in the Centre for Health Equity at the University of Melbourne. Her interdisciplinary research traverses the fields of medical anthropology, Indigenous studies, epidemiology, human geography, public health and health promotion. Smith has conducted extensive fieldwork research in remote and regional areas across Australia with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities on issues including family violence, alcohol management and health information technologies and communication.

Professor Catherine Waldby is Director of the Research School of Social Sciences at the Australian National University, and Visiting Professor at the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at King's College London. Prior to this, she was Professorial Future Fellow in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Sydney. Her researches focuses on social studies of biomedicine and the life sciences. She is Author of more than sixty research articles and seven monographs.

Professor Helen Milroy is a descendant of the Palyku people of the Pilbara region, Western Australia. Currently Helen is the Stan Perron Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the Perth Children’s Hospital and University of Western Australia, Chair of the Gayaa Dhuwi Proud Spirit Australia and a board member of Beyond Blue. Helen has been Commissioner on several national Commissions and joint winner of the Australian Mental Health Prize (2020) and named the WA Australian of the Year (2021).

Professor Marcia Langton AM is an anthropologist and geographer, and since 2000 has held the Foundation Chair of Australian Indigenous Studies at the University of Melbourne where she is also the Associate Provost. She has published extensively in the areas of political and legal anthropology, Indigenous agreements and engagement with the minerals industry, and Indigenous culture and art. Her present research focusses on alcohol management and Indigenous family violence.

Chamberlain, C. , Gray, P. , Bennet, D. , Elliott, A. , Jackomos, M. , Krakouer, J. , … Langton, M. (2022). Supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Families to Stay Together from the Start (SAFeST Start): Urgent call to action to address crisis in infant removals. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 57, 252–273. Available from: 10.1002/ajs4.200

[Correction added on 15 February 2022 after first online publication: Elizabeth Orr’s affiliation has been corrected from ‘21’ to ‘22’.]

REFERENCES

- Aboriginal Housing Victoria (2020) MANA‐NA WOORN‐TYEEN MAAR‐TAKOORT Every Aboriginal Person Has a Home: The Victorian Aboriginal Housing and Homelessness Framework. Melbourne: Aboriginal Housing Victoria. [cited 29 November 2021]. Available at: https://www.vahhf.org.au/ [Google Scholar]

- Abram, K.M. , Azores‐Gococo, N.M. , Emanuel, K.M. , Aaby, D.A. , Welty, L.J. , Hershfield, J.A. et al. (2017) Sex and racial/ethnic differences in positive outcomes in delinquent youth after detention: a 12‐year longitudinal study. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(2), 123–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda, R.F. , Butchart, A. , Felitti, V.J. & Brown, D.W. (2010) Building a framework for global surveillance of the public health implications of adverse childhood experiences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39(1), 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabena, K. (2014) The First 1000 Days: catalysing equity outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Medical Journal of Australia, 200(8), 442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, J. (2002) Trauma trails, recreating song lines: the transgenerational effects of trauma in Indigenous Australia. North Melbourne: Spinifex Press. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, C. & Arabena, K. (2021) Improving the engagement of Aboriginal families with maternal and child health services: a new model of care. Public Health Research & Practice, 31(2), e30232009. 10.17061/phrp30232009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2021) Data tables: child protection Australia 2019–20. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Blue Knot Foundation (2021) Childhood trauma and stress response. Available from: https://www.blueknot.org.au/Resources/Information/Understanding‐abuse‐and‐trauma/What‐is‐childhood‐trauma/ [Accessed 13th June 2021] [Google Scholar]

- Bond, C. (2017) We just Black matter: Australia’s indifference to Aboriginal lives and land. The Conversation, 16 October. Available from: https://theconversation.com/we‐just‐black‐matter‐australias‐indifference‐to‐aboriginal‐lives‐and‐land‐85168 [Accessed 28th September 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- Britto, P.R. , Lye, S.J. , Proulx, K. , Yousafzai, A.K. , Matthews, S.G. , Vaivada, T. et al. (2017) Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. Lancet, 389(10064), 91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashmore, J. & Paxman, M. (2007) Longitudinal study of wards leaving care: four to five years on. Sydney, NSW: University of New South Wales Social Policy Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, C. , Fergie, D. , Sinclair, A. & Asmar, C. (2016) Traditional midwifery or ‘wise women’ models of leadership: Learning from Indigenous cultures:‘…Lead so the mother is helped, yet still free and in charge…’ Lao Tzu, 5th century BC. Leadership, 12(3), 346–363. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, C. , Gee, G. , Brown, S.J. , Atkinson, J. , Herrman, H. , Gartland, D. et al. (2019) Healing the Past by Nurturing the Future—co‐designing perinatal strategies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents experiencing complex trauma: framework and protocol for a community‐based participatory action research study. British Medical Journal Open, 9(6), e028397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, C. , Gee, G. , Gartland, D. , Mensah, F.K. , Mares, S. , Clark, Y. et al. (2020) Community perspectives of complex trauma assessment for Aboriginal parents: ‘its important, but how these discussions are held is critical’. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(2014). 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, C. , Ralph, N. , Hokke, S. , Clark, Y. , Gee, G. , Stansfield, C. et al. (2019) Healing the past by nurturing the future: a qualitative systematic review and meta‐synthesis of pregnancy, birth and early postpartum experiences and views of parents with a history of childhood maltreatment. PLoS One, 14(12), e0225441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Excellence Queensland (2020) Guideline: Partnering with the woman who declines recommended maternity care. Brisbane: Queensland Health. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for Children and Young People (2021) Our youth, our way: inquiry into the overrepresentation of Aboriginal children and young people in the Victorian youth justice system. Melbourne, Vic.: Commission for Children and Young People. [Google Scholar]

- Cramp, K. & Zufferey, C. (2020) The removal of children in domestic violence: widening service provider perspectives. Affilia, 36(3), 406–425. 10.1177/0886109920954422 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, K. , Casey, D. & Ward, J. (2020) First Nations people leading the way in COVID‐19 pandemic planning, response and management. Medical Journal of Australia, 213(4), 151–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. (2019) Family is culture: independent review of Aboriginal children and young people in out of home care in New South Wales. Sydney, NSW: Family Is Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. (2020) One year on from family is culture. Sydney, NSW: AbSec and the ALS (NSW/ACT). [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2013) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plan. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Social Services (2018) Supporting families, communities and organisations to keep children safe: National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Dowell, C.M. , Mejia, G.C. , Preen, D.B. & Segal, L. (2018) Maternal incarceration, child protection, and infant mortality: a descriptive study of infant children of women prisoners in Western Australia. Health Justice, 6(1), 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, F. , Wakefield, S. , Healy, K. & Wildeman, C. (2021) Contact with child protective services is pervasive but unequally distributed by race and ethnicity in large US counties. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(30), e2106272118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti, V.J. , Anda, R.F. , Nordenberg, D. , Williamson, D.F. , Spitz, A.M. , Edwards, V. et al. (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee, G. , Dudgeon, P. , Schultz, C. , Hart, A. & Kelley, K. (2014) Understanding social and emotional wellbeing and mental health from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspective. In: Dudgeon, P. , Milroy, H. & Walker, R. (Eds.) Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing principles and practice, 2nd edition. Canberra, ACT: Australian Council for Education Research and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J. , Thurber, K. , Lovett, R. , Gray, M. , Banks, E. , Olsen, A. et al. (2020) ‘The answers were there before the white man come in’: Stories of strength and resilience for responding to violence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities ‐ Family Community Safety for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Study Report. Canberra, ACT: Australian National University. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, C. , Harries, M. & Liddiard, M. (2016) Removal at birth and infants in care: maternity under stress. Communities, Children and Families Australia, 9(2), 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Harris‐Short, S. & Tobin, J. (2019) Chapter 30, Article 30: the rights of minority and Indigenous children. In: Tobin, J. (Ed.) The UN convention on the rights of the child: a commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- He Korowai Trust (2021) Developing Tino Rangatiratanga for over 20 years. Available from: http://hkt.org.nz/ [Accessed 7th August 2021] [Google Scholar]

- Henry, K.L. , Fulco, C.J. & Merrick, M.T. (2018) The harmful effect of child maltreatment on economic outcomes in adulthood. American Journal of Public Health, 108(9), 1134–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrman, H. , Humphreys, C. , Halperin, S. , Monson, K. , Harvey, C. , Mihalopoulos, C. et al. (2016) A controlled trial of implementing a complex mental health intervention for carers of vulnerable young people living in out‐of‐home care: the ripple project. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highet, N. & Goddard, A. (2014) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Perinatal Mental Health Mapping Project: a scoping of current practice surrounding the screening, assessment and management of perinatal mental health across Australia's New Directions: Mothers and Baby Service program. Melbourne: Centre of Perinatal Excellence. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, K. , Bellis, M.A. , Hardcastle, K.A. , Sethi, D. , Butchart, A. , Mikton, C. et al. (2017) The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, C. , Kertesz, M. , Parolini, A. , Isobe, J. , Heward‐Belle, S. , Tsantefski, M. et al. (2020) Safe & together addressing complexity for children (STACY for Children). Sydney, NSW: ANROWS. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, L. , Boyle, M. , Cromby, J. , Dillon, J. , Harper, D. , Kinderman, P. et al. (2018) The Power Threat Meaning Framework: towards the identification of patterns in emotional distress, unusual experiences and troubled or troubling behaviour, as an alternative to functional psychiatric diagnosis. Leicester: British Psychological Society. [Google Scholar]

- Kildea, S. , Gao, Y. , Hickey, S. , Nelson, C. , Kruske, S. , Carson, A. et al. (2021) Effect of a Birthing on Country service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for First Nations Australians: a prospective, non‐randomised, interventional trial. Lancet Global Health, 9(5), e651–e659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kildea, S. , Hickey, S. , Barclay, L. , Kruske, S. , Nelson, C. , Sherwood, J. et al. (2019) Implementing birthing on country services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families: RISE framework. Women and Birth, 32(5), 466–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P. (2021) How stress can influence brain adaptations to motherhood. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 60, 100875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowska, K. , Walker, P. , McLean, L. & Carrive, P. (2015) Fear and the defense cascade: clinical implications and management. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 23(4), 263–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakouer, J. , Wise, S. & Connolly, M. (2018) "We live and breathe through culture": Conceptualising cultural connection for Indigenous Australian children in out‐of‐home care. Australian Social Work, 71(3), 265–276. 10.1080/0312407X.2018.1454485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langton, M. (1997) Grandmothers’ law, company business and succession in changing Aboriginal land tenure systems. In: Yunupingu, G. (Ed.) Our land is our life. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langton, M. , Smith, K. , Eastman, T. , O’Neill, L. , Cheesman, E. & Rose, M. (2020) Improving family violence legal and support services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Sydney, NSW: ANROWS. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. , Allen, J. , Bell, R. , Bloomer, E. & Goldblatt, P. (2012) WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. The Lancet, 380(9846), 1011–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, C.A. , Browne, J. , Taylor, J. & Davis, D. (2019) Making the hidden seen: a narrative analysis of the experiences of assumption of Care at birth. Women and Birth, 32(1), e1–e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, M. (2017) Lotjpa‐nhanuk: Indigenous Australian child‐rearing discourses. Ph.D thesis, Bundoora: La Trobe University. [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell, M. , Taplin, S. , Marriott, R. , Lima, F. & Stanley, F.J. (2019) Infant removals: the need to address the over‐representation of Aboriginal infants and community concerns of another ‘stolen generation. Child Abuse and Neglect, 90, 88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Productivity Commission (2021) Closing the Gap information repository. Available from: https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/children‐are‐not‐overrepresented‐child‐protection‐system [Accessed 17th June 2021] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsamy, N. (2014) Indigenous birthing in remote locations: grandmothers’ law and government medicine. In: Best, O. & Fredericks, B. (Eds.) Yatdjuligin: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nursing and midwifery care. London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sandman, C.A. & Davis, E.P. (2012) Neurobehavioral risk is associated with gestational exposure to stress hormones. Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism, 7(4), 445–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandner, M. & Thomsen, S.L. (2018) The effects of universal public childcare provision on cases of child neglect and abuse. IZA Institute of Labor Economics Discussion Paper Series IZA DP. No. 11687. Germany: IZA ‐ Institute of Labor Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, L. & Dalziel, K. (2011) Investing to protect our children: using economics to derive an evidence‐based strategy. Child Abuse Review, 20(4), 274–289. [Google Scholar]

- Shergill, M. (2018) Making the transition from university to the workplace: the emotional experiences of Newly Qualified Social Workers. Ph.D thesis, University of Sussex. [Google Scholar]

- Shlonsky, A. , Rose, D. , Harris, J. , Albers, B. , Mildon, R. , Wilson, S. et al. (2016) Literature review of prison‐based mothers and children programs: final report. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne, Save the Children Australia & Peabody Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Shmerling, E. , Creati, M. , Belfrage, M. & Hedges, S. (2020) The health needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out‐of‐home care. Journal of Paediatric and Child Health, 56(3), 384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNAICC (2016) The Family Matters roadmap. Melbourne, Vic.: SNAICC. [Google Scholar]

- SNAICC (2019) The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle: a guide to support implementation. Melbourne. Vic.: SNAICC. [Google Scholar]

- SNAICC (2020) The Family Matters report 2020: measuring trends to turn the tide on the over‐representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out‐of‐home‐care in Australia. Melbourne. Vic.: SNAICC. [Google Scholar]

- Taplin, S. (2017) Prenatal reporting to child protection: characteristics and service responses in one Australian jurisdiction. Child Abuse and Neglect, 65, 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Victorian Aboriginal Children and Young People's Alliance (2019) Referring 100% unborn reports to Aboriginal community controlled organisations. Available from: https://apo.org.au/node/270121 [Accessed 13 January 2022].

- Thomson, N. (1984) Australian Aboriginal health and health‐care. Social Science and Medicine and Health, 18(11), 939–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurber, K.A. , Barrett, E.M. , Agostino, J. , Chamberlain, C. , Ward, J. , Wade, V. et al. (2021) Risk of severe illness from COVID‐19 among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults: the construct of ‘vulnerable populations’ obscures the root causes of health inequities. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 45(6), 658–663. 10.1111/1753-6405.13172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tune, D. (2017) Independent review of out of home care in New South Wales – final report. Available from: https://www.acwa.asn.au/wp‐content/uploads/2018/06/TUNE‐REPORT‐indepth‐review‐out‐of‐home‐care‐in‐nsw.pdf [Accessed 01 August 2021] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (1989) Convention on the rights of the child. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx [Accessed 28 September 2021] [Google Scholar]

- Varcoe, C. , Brown, H. , Calam, B. , Harvey, T. & Tallio, M. (2013) Help bring back the celebration of life: a community‐based participatory study of rural Aboriginal women’s maternity experiences and outcomes. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(26). 10.1186/1471-2393-13-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Western Australian Government (2021) Aboriginal family led decision making. Available from: https://www.wa.gov.au/organisation/department‐of‐communities/aboriginal‐family‐led‐decision‐making [Accessed 07 August 2021] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V. , Murphy, D. , Phelps, A. , Forbes, D. & Greenberg, N. (2021) Moral injury: the effect on mental health and implications for treatment. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(6), 453–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R. (1997) Bringing them Home: report of the national inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, S. & Corrales, T. (2021) Discussion of the Knowns and Unknowns of Child Protection During Pregnancy in Australia, Australian Social Work, 10.1080/0312407X.2021.2001835 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (1946) Constitution of the World Health Organisation. Geneva: World Health Organisation.[Correction added on 15 February 2022 after first online publication: The citation and reference for Wise and Corrales (2021) were added to the article.] [Google Scholar]