Abstract

This study aimed to use orange albedo flour as a fat replacer and evaluate its effect on three chicken mortadella formulations: C (control, 0% replacer addition, chicken skin as a fat source), F1 (4.8% replacer addition, standing for 22.8% partial fat replacement), and F2 (8.4% replacer addition, standing for 34% partial fat replacement). Fat replacer addition increased moisture and carbohydrate contents but reduced protein and ashes in mortadella formulations. F1 and F2 showed reductions in firmness, chewiness, cohesiveness, and springiness when compared to C. Furthermore, L* and b* parameters increased and a* reduced by fat replacer addition into formulations. All formulations showed good oxidative stability over the 90 days of storage. Fat replacer inclusion decreased polyunsaturated fatty acids and ω-6 contents. Overall, formulations had good sensorial acceptance and purchase intention by consumers, regardless of fat replacer addition. All formulations also had stable emulsion confirmed by optical microscopy. In short, orange albedo flour was feasible as fat replacer in chicken mortadella formulation, not compromising its quality and enabling light mortadella preparation.

Keywords: Agroindustrial by-product, Pectin, Sensorial analysis, Optical microscopy, Lipid oxidation

Introduction

Meat products are important in human nutrition, especially for providing healthy nutrients such as essential amino acids, iron, and calcium (Damodaran and Kirk 2019). Among them, mortadella stands out as an emulsified product highly appreciated for its pleasant sensorial attributes such as aroma, taste, and texture, which comes mainly due to fat content in its composition (Hygreeva et al. 2014). Chicken skin is the main fat source in chicken mortadella and has about 52.80% moisture, 13.01% protein, 34.48% fat, and 0.46% ashes (Henry et al., 2019). Nevertheless, consumer demands for meat products have changed because of potential health risks associated with high-fat diets, such as overweight and cardiovascular diseases (Schönbach et al. 2019). Thus, food industries have adopted new processing technologies and used different ingredients to provide healthier products to consumers.

Dietary fiber is a feasible mean of replacing fat used to improve food functional properties such as gelation and/or emulsification, viscosity, and water-holding capacity, besides reducing cooking losses and improving texture, especially in meat products (Elleuch et al. 2011). Among the fibers used, pectin stands out for its water solubility. This polysaccharide is mostly found in citrus peels and widely used as a food additive due to its gelation and emulsion stabilization properties (Leroux et al. 2003).

Citrus fruit processing usually generates large amounts of waste, mainly from the fruit part known as albedo. This, in turn, is rich in pectin, which can be recovered and add value to food formulations, economic and ecological benefits to the food sector (Hygreeva et al. 2014).

Some studies have shown that dietary fiber inclusion in meat products improves their properties. Coksever and Saricoban (2010) demonstrated that Turkish fermented sausages (sucuks) added with 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0% orange albedo have fewer cooking losses and lipid contents, mainly at 5.0%. In the same line, Han and Bertam (2017) observed improves in water-holding capacity and decreases in cooking losses by incorporating 2% inulin, cellulose, carboxymethylcellulose, chitosan, and pectin, separately, into a low-fat meat emulsion system. Shan et al. (2015) also added grapefruit albedo to Frankfurt sausages at six different levels (0.0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, 10.0, and 12.5%) and observed emulsifying capacity increases, mainly at 5%, and cooking loss reductions, mainly at 7.5%.

Given the above, our study aimed to use orange albedo in as a fat replacer in chicken mortadella formulations, evaluating their physicochemical, technological, and sensory properties.

Material and methods

Raw material

Albedo used in this study was removed from oranges [Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck] of the variety Pera, which were obtained from local commerce in the city of Paranavaí—PR (Brazil). After sanitizing, the fruits had their albedo removed for processing, drying, and flour acquisition, and then preparing a fat replacer.

Orange albedo flour preparation

Orange albedo flour was prepared at the Federal Institute of Paraná State (IFPR), Campus Paranavaí (Paranavaí, PR, Brazil). The oranges were washed in running water and neutral detergent, and then sanitized by immersion in running chlorinated water for 15 min, and then rinsed. The outer part of orange peel (flavedo) was manually removed until the white part of the peel (albedo) appeared. This was then removed and subjected to bleaching in boiling water for 3 min, followed by thermal shock in an ice bath. The material was subjected to drying in an air forced-circulation and -renewal oven (TE394/2, Tecnal, Brasil) at 45 °C for 12 to 15 h. The dried material was ground in a knife mill grinder (IKA A11, Germany) until producing a 60-mesh flour.

Fat replacer preparation

Fat replacer was developed using the method described by Santos (2003). First, a 2.5-mg anhydrous citric acid (99% PA) solution (Alphatec) was prepared in 200 mL distilled water to maintain pH between 3.2 and 3.5, measured by a digital pH meter (Mettler Toledo FE20 Five Easy™). Then, 10.0 g orange albedo were added to each 100 mL solution, which was then heated at 100 °C under constant stirring for 20 min. Lastly, the mix was cooled to room temperature (about 25 °C) and stored under refrigeration (4 °C) before being used.

Orange albedo flour and fat replacer physical–chemical analyses

Orange albedo flour was analyzed in triplicate for proximate chemical composition (AOAC, 2000). Moisture was determined by drying in an oven at 105 °C to constant weight. Ashes were quantified by incineration in a muffle furnace at 550 °C. Lipid content was analyzed by the Soxhlet method, using petroleum ether as solvent. Proteins were quantified by the micro-Kjeldahl method, using a 6.25 conversion factor. Total, soluble, and insoluble fibers were determined by the enzymatic–gravimetric method. Carbohydrate contents were calculated by difference.

Color parameters were measured in triplicate both for orange albedo and fat replacer, using a colorimeter (Minolta, CR400), with light source D65 and 10° vision angle. Results were expressed by the CIELAB system: L* (luminosity), a* (red–green component); b* (yellow–blue component). Water activity (wa) was measured only for fat replacer samples, using a AquaLab dew-point hygrometer (4 TEV, AquaLab, EUA).

Chicken mortadella processing

Chicken mortadella formulations were prepared at the Federal University of Technology—Paraná, Campus of Londrina (Londrina, PR, Brazil). Chicken breast fillets, artificial packaging, and soy protein concentrate were kindly donated by the company Frios Londrina (Londrina, PR, Brazil). Chicken skin and mechanically separated meat (MSM) were provided by the company Frango Granjeiro (Rolândia, PR, Brazil). Finally, Duas Rodas kindly donated sodium erythorbate, curing salt, sodium tripolyphosphate, powdered spices, and white pepper.

For this study, three chicken mortadella formulations were prepared, namely: C (control), F1, and F2, which comprised inclusions of 0%, 4.8%, and 8.4% fat replacer, respectively. First, chilled (0 °C) chicken breast fillets (43.0%) were brought to the chopper along with ice (11.0%), cut, and added with CMS (23.53%) as grinding began. After mass homogenization, chicken skin and orange albedo flour (fat replacer) were added as fat sources. Next, soy protein concentrate (4.00%) was added together with manioc starch (3.00%), salt (2.00%), sugar (0.60%), sodium tripolyphosphate (0.25%), garlic (0.20%), curating salt (0.10%), sodium erythorbate (0.10%), white pepper (0.08%), paprika (0.08%), and onion (0.06%). After about 3-h resting, the dough was stuffed into artificial polyamide casings, in units of about 300 g each. Cooking was performed in a Dubnoff water bath as follows: 20 min at 45 °C, 20 min at 55 °C, 20 min at 65 °C, 20 min at 75 °C, and at 85 °C until the internal temperature of dough reaches 72 °C. Afterward, the mortadella formulations were cooled in running water and stored at 4 °C.

Chicken mortadella physical–chemical analyses

Chicken mortadella formulations were evaluated for proximate chemical composition in triplicate (AOAC, 2000), as described in item 6.1.2.4.

Color parameters were determined in triplicate in the inner part of mortadella pieces. Six different points were measured per sample by the colorimeter (Minolta, CR400), with light source D65 and 10° vision angle. Results were expressed by the CIELAB system: L* (luminosity), a* (red-green component); b* (yellow-blue component). Total color difference (ΔE) was calculated throughout the storage period (1 to 90 days) for all mortadella formulations, using the following equation: ΔE* = [(L*to—L*t)2 + (a*to—a*t)2 + (b* to – b*t)2]1/2; wherein to indicates 24 h storage after processing and t indicates the storage times of 40, 60 and 90 days.

Chicken mortadella formulations were measured for pH in triplicate, using a Mettler Toledo pH meter. The formulations were also assessed for water activity (wa), using the AquaLab dew-point hygrometer (4 TEV, AquaLab, EUA).

Water-holding capacity (WHC) was determined in triplicate, according to the method of Troy et al. (1999), which is based on sample weight difference after heating (90 °C) and centrifugation (9000 × g to 4 °C per 10 min.). Results were expressed by weight difference in retained water percentage.

Firmness, texture, elasticity, cohesiveness, and chewiness (chewiness = hardness × cohesiveness × elasticity) were evaluated in triplicate using a Universal TA.XT2i texturometer with a P035 metallic probe, as in Bourne (1978). To this purpose, samples were cut into cylindrical form (3 cm diameter × 2.2 cm height). The formulations were compressed to 50% at pre-test, test, and post-test rates of 5 mm s−1, and compression force of 0.98 N.

Chicken mortadella lipid oxidation

Mortadella formulations were evaluated for lipid oxidation in triplicate, using samples processed after 24 h and stored for 30, 60, and 90 days at 4 °C by thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) (Tarladgis et al. 1964) modified by Crackel et. al. (1988), expressed as mg TBARS kg−1.

Chicken mortadella fatty acids profile

Lipids were extracted in triplicate, using samples processed after 1, 30, 60, and 90 days at 4 °C by the method of Bligh and Dyer (1959). The hydrolysis and transesterification of the fatty acids were performed according to ISO method 5509 (ISO 1978), using 2 mol L−1 NaOH in methanol and n-heptane. The fatty acid methyl esters were analyzed using a Shimadzu 17A gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and a fused-silica capillary column (100.00 m × 0.25 mm) with 0.25 µm CP Sil-88. The column was programmed to heat up: first to 65 °C and held for 15 min; second to 165 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1 and held for 2 min; third to 185 °C at 4 °C min−1 and held for 8 min; and finally to 235 °C at 4 °C min−1 and held for 5 min. The detector and injector were kept at 260 °C. Hydrogen was used as carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.2 mL min−1 and split mode (1: 100). Gas flows were 1.2 mL min−1 for carrier gas (H2), 30 mL min−1 for auxiliary gas (N2), and 30 and 300 mL min−1 for flame gases, H2 and synthetic air, respectively. Fatty acids were identified based on the fatty acid methyl esters pattern (Sigma FAME 189,191). Peaks were integrated using area, and results expressed as a percentage of each identified fatty acid.

Microbiological analyses

Microbiological analyses were performed in triplicate in mortadella samples processed and stored for 7 days at 4 °C, according to Resolution number 12 of ANVISA (BRASIL 2001). The analyses comprised counts of thermotolerant coliforms (45 °C), Staphylococcus coagulase positive, Clostridium sulfite reductor (46 °C), and Salmonella spp.

Chicken mortadella sensorial analysis

Mortadella sensorial analysis was conducted at Londrina State University (Londrina, PR, Brazil), after approval by the university Ethics Committee on Human Research (CAE n° 08,631,219.7.0000.5231). The team of evaluators included 100 untrained individuals, of which 70% women and 30% men of different ages. The sensorial analysis was carried out in individual booths where each participant received one sample at time, each sample (20 g) were randomly labeled with a 3-digit code number.

All formulations (C, F1, and F2) were tested for acceptance using a 9-point hedonic scale (1 = disliked extremely to 9 = liked extremely) regarding appearance, color, aroma, taste, texture, and overall impression. As for purchase intention, a 5-point Likert scale (1 = definitely would not buy to 5 = certainly would buy) was adopted. Using the averages of parameters, an acceptance index (AI) was calculated by the following equation: AI (%) = A × 100/B; wherein A is the average score obtained by an attribute and B is the maximum score given to the same attribute.

Chicken mortadella optical microscopy

Mortadella samples were cut into 1.5 cubic cm shapes before being fixed in a 10% buffered formaldehyde solution for 48 horas. Next, they remained in alcohol 70% until the macroscopic cleavage performance. Then, they were submitted to dehydration, diaphonization, and paraffinization in an automatic tissue processor, using progressive baths of alcohol, xylol and paraffin in liquid state, respectively. The samples were then included in paraffin, with blocks kept under refrigeration for posterior sectioning in a microtome to 5 µm thick sections. These sections were put on histological slides and remained in an oven for 4 h for paraffin melting, and then maintained under room temperature. Afterward, they were colored with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), together with the assembly of glass slides and synthetic resin. Measurements were performed under a Opticam 0500R optical microscope at 20 times magnification.

Statistical analysis

Data were evaluated by the Statistica 7.0 (StatSoft) software, using the Tukey’s test at 5% probability to compare means among mortadella formulations and among storage periods.

Results and discussion

Orange albedo flour and fat replacer physical–chemical analyses

The main components in orange albedo flour were total carbohydrates, representing 79.44% (Table 1). Oliveira et al. (2019) obtained a similar value for mombuca blood orange flour (77.5%). The second components found at higher proportions were dietary fibers, representing 63.92%, of which 29.34% soluble fibers and 34.58% insoluble fibers. Therefore, orange albedo flour is rich in dietary fiber, making it a feasible fat substitute in meat products. Our findings corroborate those of Rivas et al. (2008), who detected pectin as predominant component in orange albedo (42.5%), as well as fractions of soluble sugars (16.9%), and cellulose (9.21%) and hemicellulose (10.5%).

Table 1.

Average of values of approximate chemical composition and color parameters (L*, a*, b*) evaluated in orange albedo flour and color parameters (L*, a*, b*), pH and water activity (Aw) evaluated in fat replacer based on orange albedo flour

| Parameters | Flour orange albedo |

|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 13.15 ± 0.26 |

| Lipids (%) | 0.32 ± 0.08 |

| Proteins (%) | 4.78 ± 0.43 |

| Ash (%) | 2.31 ± 0.02 |

| Total Carbohydrates (%) | 79.44 ± 0.27 |

| Dietary Fibers (%) | 63.92 ± 1.53 |

| Soluble Fibers (%) | 29.34 ± 1.04 |

| Insoluble Fibers (%) | 34.58 ± 0.72 |

| L* | 90.92 ± 2.03 |

| a* | − 1.12 ± 0.17 |

| b* | 22.55 ± 0.32 |

| Fat replacer | |

| L* | 93.38 ± 2.94 |

| a* | − 1.54 ± 0.09 |

| b* | 18.75 ± 1.07 |

| pH | 3.48 ± 0.06 |

| Aa | 0.99 ± 0.002 |

Results expressed as average ± standard deviation

Moisture content in orange albedo flour was 13.15%, which is in accordance with Resolution RDC No. 263, of 09/22/2005, of the National Health Surveillance Agency (Brasil, 2005). The contents of proteins and ashes were similar to those found by Tozatti et al. (2013), who observed 4.64% proteins and 2.35% ashes in orange peel and bagasse flours. The minor constituents were lipids (0.32%), making orange albedo flour a suitable ingredient in mortadella formulations as a fat replacer.

Color analysis revealed that orange albedo flour was clear (L* = 90.92), slightly greenish (a* = − 1.12) and yellowish (ab* = 22.55). These results are similar to those described by Menezes et al. (2019) for orange albedo flour. Accordingly, fat replacer prepared with the flour also was clear (L* = 93.38), slightly greenish (a* = − 1.54), and yellowish (b* = 18.75) (Table 1).

Regarding pH, the replacer was acid (3.48) due to citric acid inclusion for gelification. As orange albedo is pectin rich, its acidification is important. Reductions in pH decrease dissociation of carboxylic groups, increasing contact regions between the molecules, retaining water, and forming a gel (Damodaran and Kirk 2019).

As for water activity, the fat replacer had a high value (0.99), hence high free water content. However, this did not influence was in mortadella, as there was no difference in was among formulations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Average values of chemical composition, water holding capacity (WHC), pH, water activity (wa), texture parameters, color parameters (L*, a*, b*) and color difference (ΔE) of chicken mortadella prepared with addition of 0% (C), 4.8% (F1) and 8.4% (F2) of fat replacer based on orange albedo flour

| Parameters | C | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 64.27c ± 0.23 | 67.32b ± 0.28 | 68.70a ± 0.34 |

| Ash (%) | 3.62a ± 0.05 | 3.53b ± 0.02 | 3.45c ± 0.04 |

| Proteins (%) | 20.90a ± 0.77 | 18.85b ± 0.51 | 18.82b ± 0.76 |

| Lipids (%) | 8.82a ± 0.31 | 6.81b ± 0.12 | 5.82c ± 0.49 |

| Total Carbohydrates (%) | 2.39b ± 0.02 | 3.49a ± 0.04 | 3.21a ± 0.05 |

| Soluble Fibers (%) | 0.50b ± 0.46 | 0.72b ± 0.17 | 1.72a ± 0.11 |

| WHC (%) | 98.09a ± 0.11 | 98.01a ± 0.12 | 97.96a ± 0.15 |

| pH | 6.18a ± 0.01 | 6.19a ± 0.01 | 6.14b ± 0.01 |

| wa | 0.98a ± 0.00 | 0.98a ± 0.00 | 0.99a ± 0.01 |

| Firmness (N) | 99.74a ± 4.97 | 81.80b ± 2.51 | 78.36b ± 5.39 |

| Cohesivity | 0.82a ± 0.04 | 0.81ab ± 0.03 | 0.78b ± 0.01 |

| Elasticity | 0.97a ± 0.02 | 0.98a ± 0.00 | 0.97a ± 0.01 |

| Chewability | 87.51a ± 3.09 | 63.17b ± 1.26 | 60.94b ± 3.25 |

| Resilience | 0.416a ± 0.05 | 0,397ab ± 0.02 | 0,366b ± 0.02 |

| L* | 63.62c ± 0.70 | 64.52b ± 0.68 | 65.25a ± 0.91 |

| a* | 13.14a ± 0.64 | 12.40b ± 0.69 | 12.22b ± 0.25 |

| b* | 13.46a ± 0.73 | 12.89b ± 0.67 | 13.04ab ± 0.32 |

| ΔE (0–90 days) | 2.42a ± 0,89 | 1.20b ± 0.55 | 1.51b ± 0.60 |

Results expressed as average ± standard deviation

a,bMeans within rows followed by different letters differ significantly by Tukey’s test at 5% probability

Chicken mortadella physical–chemical analyses

Chicken mortadella proximate chemical composition (Table 2) was influenced by fat replacer addition. Moisture contents differed (p < 0.05) among all treatments as fat replacer was added, showing about 90% water in their composition. F2 had higher moisture content, which may be due to fat replacer addition, as water is the second largest constituent (Table 1). However, moisture increases had no effect on wa of the product, which may be due to its higher fiber content (Table 1). A similar result was reported by Fernández-Ginés et al. (2004), who observed moisture increases in mortadella due to incorporation of raw or cooked lemon albedo.

The inclusion of 4.8% fat replacer (F1) reduced fat by 22.79%, while 8.4% (F2) by 34.0% (p < 0.05) compared to the control. Thus, F2 can be labelled as light chicken mortadella since it has at least 25% less lipids of what is regulated by RDC number 54, of 11/12/2012 (Brasil, 2012). Lipid reductions in meat products by inclusion of dietary fibers has already been described by other authors (Henck et al. 2019; Han and Bertram 2017; Henning et al. 2016; Coksever and Sariçoban 2010).

Addition of fat replacer increased (p < 0.05) soluble dietary fiber content in mortadella formulations. This was due to the presence of highly soluble dietary fiber in orange albedo flour (Table 1), which is mainly composed of pectin (Leroux et al. 2003).

F1 and F2 showed lower protein contents (p < 0.05) than did the control. This is due to the higher protein content in chicken skin (13.01%) (Henry et al. 2019) when compared to the fat replacer from orange albedo flour (4.78%, Table 1). Henning et al. (2016) also reported lower protein contents in sausages containing commercial pineapple fibers as fat replacer, as the formulation had lower meat fat content. Such lower protein content may also be related to increasing moisture contents in meat products, as observed by Coksever and Saricoban (2010).

The formulations added with fat replacers had higher total carbohydrate content than the control (p < 0.05). However, all values of this parameter, as well as those for lipids and proteins, remained within the requirements in the Normative Instruction number 4, of 03/31/2000 (Brasil 2000).

Ash content reduced (p < 0.05) with increasing fat replacer concentration. This may be due to the higher amount of water in fiber-added formulations (Henning et al. 2016).

Fat replacer addition had no effect (p > 0.05) on water-holding capacity (WHC) of mortadella formulations (Table 2). All three formulations had high WHC values, which also contributed to product texture and yield. Water activity (wa) was also not affected by fat replacer addition, but had high values (Table 1). However, adding 8.4% fat replacer (F2) reduced pH in mortadella formulation, probably due to the high acidity of orange albedo flour (pH = 3.48, Table 1).

Fat replacer addition (F1 and F2) also decreased product firmness (p < 0.05) compared to the control (Table 2). A similar behavior was also observed for chewiness, as this is influenced by product firmness. Firmness and chewiness reductions may be related to the increased moisture contents in F1 and F2. Han and Bertram (2017) also reported firmness and chewiness decreases in emulsified meat products, which showed a fat reduction with addition of 2% pectin.

As for cohesivity and springiness, F2 was around 2.5% and 12% lower (p < 0.05) than the control formulation, respectively, while elasticity was not affected by fat replacer addition. The effect on cohesivity has already been reported by other authors who used fibers as partial fat replacers in meat products (Henck et al. 2019).

Regarding color parameters, addition of fat replacer increased (p < 0.05) L* value in mortadella formulation (Table 2), which might be due to fat replacer color (Table 2). A similar observation was made by Fernández-Ginés et al. (2004) for mortadella added with raw or cooked lemon albedo. The parameter a* was inferior (p < 0.05) in formulations with fat replacer (F1 and F2) compared to the control mortadella; therefore, they were less reddish. Fernández-Ginés et al. (2004) also mentioned a* reduction by adding raw or cooked lemon albedo into bologna mortadella and related it to product moisture, as higher moisture samples corresponded to lower a* values, as in our study. In regards to parameter b*, F1 showed a lower value (p < 0.05) than the control, but F2 did not differ (p > 0.05) from the others; therefore, fat replacer had little influence on this color parameter.

To be perceptible to the human eye, color difference (ΔE) should be greater than 2 (Moarefian et al. 2013). After 90-day storage, only the control formulation showed such perceptible difference (ΔE = 2.42), while F1 and F2 had ΔE below that of control and less than 2 (p < 0.05). These results therefore indicate that the fat replacer contributed to color maintenance, which is important for the sale of mortadella.

Microbiological analyses detected in 25 g of sample the following counts: < 3 CFU g−1 for thermotolerant coliforms (45 °C), < 100 CFU g−1 for Staphylococcus coagulase positive, < 10 CFU g−1 for Clostridium sulfite reductor (46 °C), and absence of Salmonella sp. Therefore, all mortadella formulations were innocuous.

Chicken mortadella lipid oxidation

When compared to the control formulation, F2 showed lower lipid oxidation (p < 0.05) on the first day of storage (Table 3), but with no significant difference from F1. However, at 30, 60, and 90 days of storage, TBARS values were similar among all mortadella formulations. A higher lipid oxidation on the first day of storage may have been due to the high fat content in the control formulation. However, as the days passed under refrigeration, antioxidants in the control formulation, such as erythorbic and sodium nitrite, helped to control lipid oxidative reactions.

Table 3.

Average values of lipid oxidation of chicken mortadella prepared with addition of 0% (C), 4.8% (F1) and 8.4% (F2) of fat replacer based on orange albedo flour

| Lipid oxidation ( mg of TBARS.kg−1 of sample) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Storage (days) | C | F1 | F2 |

| 01 | 0.10aB ± 0.01 | 0.08abB ± 0.02 | 0.07bB ± 0.00 |

| 30 | 0.16aA ± 0.03 | 0.16aA ± 0.01 | 0.16aA ± 0.02 |

| 60 | 0.10aB ± 0.02 | 0.09aB ± 0.01 | 0.08aB ± 0.01 |

| 90 | 0.09aB ± 0.02 | 0.10aB ± 0.02 | 0.09aB ± 0.01 |

Results expressed as average ± standard deviation

A,BMeans within rows followed by different uppercase letters differ significantly by Tukey’s test at 5% probability

a,bMeans within columm followed by different lowercase letters differ significantly by Tukey’s test at 5% probability

Between the first and the 30th day of storage, TBARS levels increased in the three mortadella formulations, reaching a peak of 0.16 mg TBARS Kg−1 mortadella sample. From the 60th day of storage onwards, TBARS levels reduced by 62.5% but remained constant until the 90th day.

Importantly, all formulations showed good oxidative stability during storage period. Therefore, addition of fat replacer made from orange albedo flour did not affect mortadella quality, contributing to its shelf life and sensory stability. Henck et al. (2019) reported similar results for chicken sausages added with wheat and alpha-cyclodextrin during 60 days of storage.

Chicken mortadella fatty acids profile

The fatty acids mostly found in all formulations of chicken mortadella were monounsaturated oleic acid (C18:1 ω-9), saturated palmitic and linoleic acids (C16:0), and polyunsaturated linoleic acid (C18:2 ω-6) (Table 4). Saldaña et al. (2015) found the same main fatty acids at similar amounts in chicken mortadella.

Table 4.

Fatty acid profiles identified in chicken mortadella prepared with addition of 0% (C), 4.8% (F1) and 8.4% (F2) of fat replacer based on orange albedo flour

| Fatty Acids | C | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| C6:0 | 0.21a ± 0.04 | 0.19a ± 0.09 | 0.25a ± 0.03 |

| C14:0 | 0.52a ± 0.06 | 0.46a ± 0.06 | 0.48a ± 0.08 |

| C16:0 | 22.90a ± 0.27 | 23.20a ± 0.44 | 23.17a ± 0.02 |

| C16:1 ω -7 | 5.02a ± 0.15 | 5.12a ± 0.10 | 4.50b ± 0.27 |

| C18:0 | 6.44a ± 0.16 | 6.16a ± 0.79 | 7.07a ± 0.22 |

| C18:1 ω -9 | 39.05a ± 0.13 | 39.53a ± 0.79 | 40.50b ± 0.23 |

| C18:2 ω -6 | 22.40a ± 0.38 | 22.06a ± 0.35 | 21.18b ± 0.25 |

| C18:3 ω -3 | 1.74a ± 0.04 | 1.59ab ± 0.20 | 1.39b ± 0.13 |

| C20:4 ω -6 | 0.66a ± 0.25 | 0.58a ± 0.10 | 0.55a ± 0.03 |

| SFA | 30.07a ± 0.25 | 30.01a ± 0.99 | 30.97a ± 0.41 |

| MUFA | 44.07a ± 0.63 | 44.63a ± 0.21 | 44.99a ± 0.71 |

| PUFA | 24.80a ± 0.20 | 24.23b ± 0.54 | 23.13c ± 0.35 |

| ω-3 | 1.74a ± 0.04 | 1.59ab ± 0.20 | 1.39b ± 0.13 |

| ω-6 | 23.06a ± 0.17 | 22.64b ± 0.41 | 21.74c ± 0.27 |

| PUFA/SFA | 0.82a ± 0.01 | 0.81a ± 0.03 | 0.75b ± 0.03 |

| ω-6/ ω-3 | 13.23a ± 0.24 | 14.50a ± 2.07 | 15.72a ± 1.40 |

Results expressed as average ± standard deviation

a,bMeans within rows followed by different lowercase letters differ significantly by Tukey’s test at 5% probability

SFA = (6:0 + 14:0 + 16:0 + 18:0); MUFA = (16:1 ω-7 + 18:1 ω-9); PUFA = (18:2 ω-6 + 18:3 ω-3 + 20:2 + 20:3 + 20:4 ω-6); ω3 = (18:3 ω-3); ω-6 = (18:2 ω-6 + 20:4 ω-6)

All three mortadella formulations showed significant differences (p > 0.05) between contents of saturated (SFA) and monounsaturated (MUFA) fatty acids. Yet, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and ω-6 decreased with addition of fat replacer. This can be justified by fat content reductions. High contents of polyunsaturated fatty acids can lead to greater oxidative instability (Min and Ahn 2009), as observed in the control during early storage (Table 3).

The ratio between polyunsaturated and saturated fatty acids ranged between 0.75 and 0.82, with the lowest value in F2; however, they were all above the recommended minimum for intake of 0.4 (Wood et al. 2003). The ratio between ω-6 and ω-3 showed no differences among samples but high values for this relation, varying, on average, from 13:1 to 15:1, due to meat and fat.

Adding 8.4% fat replacer (F2) reduced (p < 0.05) palmitoleic (C16:1 ω-7) and linoleic (C18:2 ω-6) fatty acid contents compared to control and F1, and C18:3 ω-3 content compared to control. This could be due to a 34% reduction in fat content in F2 (Table 2). Conversely, unsaturated oleic acid (C18: 1 ω-9) was found in greater proportion in F2 than in F1 and control, which, however, had no impact on the increased lipid oxidation of this formulation (Table 3).

Chicken mortadella sensorial analysis

All three mortadella formulations had no differences for acceptance and purchase intention tests, nor regarding sensory attributes. Therefore, fat replacer addition had no effect on the sensorial characteristics of the mortadella formulations (Table 5). Averages of the three formulations were between 6.76 and 6.82 for global evaluation, which indicates a good acceptance by consumers.

Table 5.

Average of achieved score of sensorial acceptance and purchase intente of chicken mortadella prepared with addition of 0% (C), 4.8% (F1) and 8.4% (F2) of fat replacer based on orange albedo flour

| Attributes | C | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | 6.49a ± 1.73 | 6.65a ± 1.73 | 6.88a ± 1.57 |

| Color | 6.39a ± 1.75 | 6.37a ± 1.76 | 6.75a ± 1.63 |

| Aroma | 6.50a ± 1.93 | 6.43a ± 1.77 | 6.56a ± 1.66 |

| Taste | 6.84a ± 1.40 | 6.86a ± 1.56 | 6.53a ± 1.56 |

| Texture | 6.89a ± 1.77 | 7.01a ± 1.68 | 6.96a ± 1.50 |

| Overall impression | 6.76a ± 1.58 | 6.80a ± 1.59 | 6.82a ± 1.37 |

| Purchase intention | 3.49a ± 0.99 | 3.63a ± 1.07 | 3.53a ± 1.01 |

Results expressed as average ± standard deviation

a,bMeans within rows followed by different lowercase letters differ significantly by Tukey’s test at 5% probability

The other attributes had averages between 6.37 and 7.01. These findings show the potential for producing light mortadella with a 34% reduction in fat (F2) from orange juice by-product, without compromising product sensory quality.

As for purchase intention, scores remained between 3 (would probably buy it/would probably not buy it) to 4 (would possibly buy the product). Therefore, both control and fat replaced (F1 and F2) formulations had similar possibilities of being chosen by the consumer.

All attributes showed acceptability indexes above 70%, varying from minimum requirement to good market acceptance. Other authors have already reported good sensorial acceptance for Bologna sausages added with other vegetal source of dietary fiber (Fernández-Ginés et al. 2004).

Chicken mortadella optical microscopy

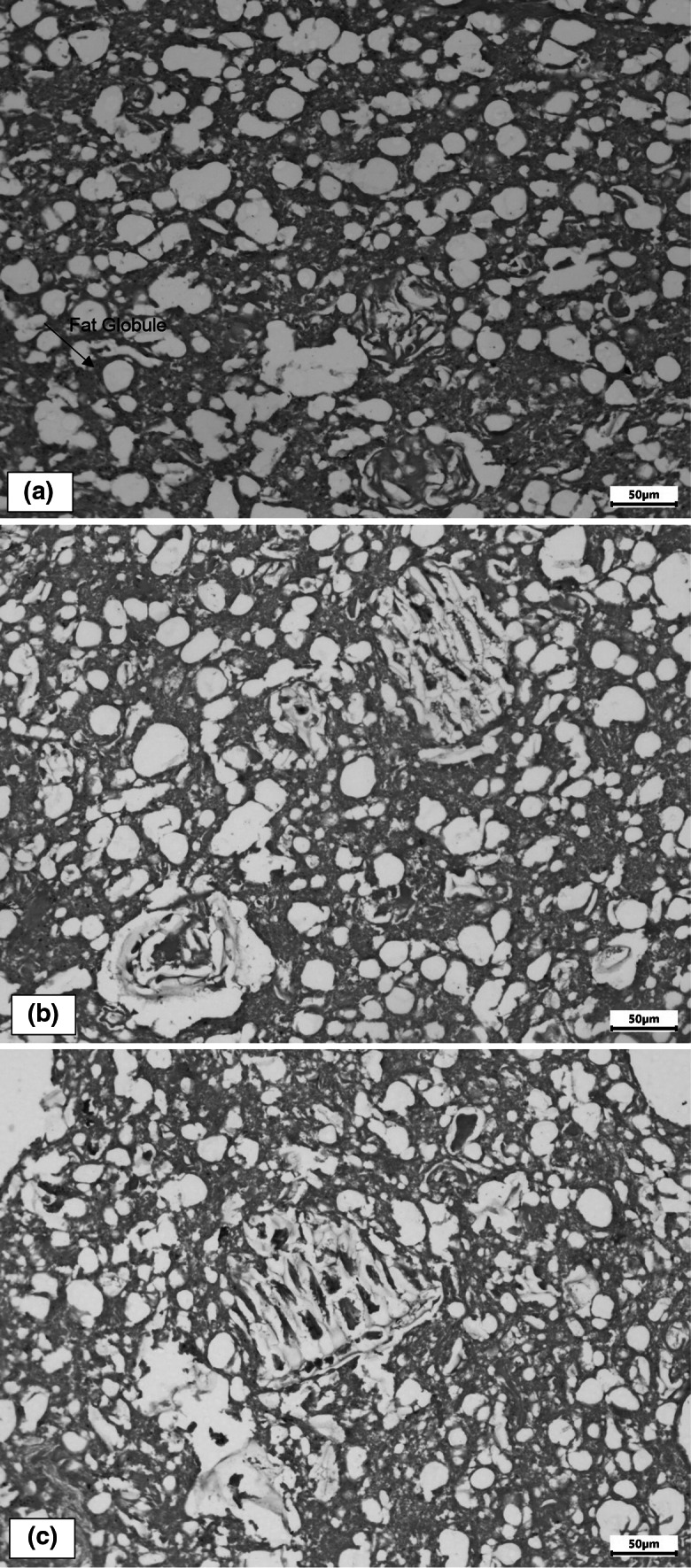

Optical microscopy control mortadella (Fig. 1a) showed predominance of uniform fat globules surrounded by a protein film, characterizing stable emulsion. F1 mortadella (Fig. 1b), apart from non-uniform fat globules, shows vegetable fibers derived from orange albedo flour, which are in a continuous emulsion and tend to approach fat globules. On the other hand, F2 mortadella (Fig. 1c) shows no trend of association between fibers and fat globules and vegetable fibers can be visualized more clearly in a continuous emulsion phase.

Fig. 1.

Optical microscopy of chicken mortadella prepared with addition of 0% (1a), 4.8% (1b) and 8.4% (1c) of fat replacer based on orange albedo flour, 20 times magnification

Our results demonstrate that all mortadella formulations had stable emulsion with fat globules wrapped in a protein film, even F2 with 34% fat reduction. Optical microscopy results corroborate our other results and show neither technological nor sensorial losses for these mortadella formulations.

Conclusion

The use of fat replacer prepared from orange albedo flour in mortadella formulations promoted an increase in moisture without changing water activity, besides promoting a significant reduction in fat content (23% for F1 and 35% for F2). It also did not affect water-holding capacity, emulsion stability, and lipid oxidation.

Addition of fat replacer increased luminosity and reduced firmness, chewiness, and cohesiveness without compromising elasticity, which were not noticed by sensory analyses. All mortadella formulations had good acceptance and high purchase intent by consumers.

The fat replacer made from orange albedo flour proved to be a feasible alternative for manufacturing chicken mortadella without compromising product quality.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the National Council for Scientific and Technological (CNPq) for granting a aster’s degree scholarship to Belluco, CZ.

Author contributions

BCZ, MDF and SAL planned the experiments. BCZ carried out the experiments. All authors contributed to the interpretation and discussion of the results. BCZ wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Funding

The National Council for Scientific and Technological (CNPq).

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest of this manuscript entitled by “Application of orange albedo fat replacer in chicken mortadella”.

Ethical approval

The project was approved by the Londrina State University Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Beings (CAAE n° 08631219.7.0000.5231).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Caroline Zanon Belluco, Email: carollzb@hotmail.com.

Fernanda Jéssica Mendonça, Email: fernanda.mendonca@live.com.

Iolanda Cristina Cereza Zago, Email: iolandacerezago@gmail.com.

Giovana Wingeter Di Santis, Email: giovanaws@uel.br.

Denis Fabrício Marchi, Email: denis.marchi@ifpr.edu.br.

Adriana Lourenço Soares, Email: adri.soares@uel.br.

References

- Association of official analytical chemists – AOAC . Official methods of analysis of AOAC international. 17. Gaithersburg: AOAC International; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37(8):911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne MC. Texture profile analysis. Food Technol. 1978;7(32):62–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.1978.tb01219.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brasil, Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento (2000) Instrução normativa n° 4, de 31 de março de 2000. Aprova os regulamentos técnicos de identidade e qualidade de carne mecanicamente separada, de mortadela, de linguiça e de salsicha. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil

- Brasil. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (2001) Resolução da diretoria colegiada, RDC n° 12, de 2 de janeiro de 2001. Regulamento técnico sobre padrões microbiológicos para alimentos. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil

- Brasil. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. (2005). Resolução RDC nº 263, de 22 de setembro de 2005: Aprova o “Regulamento técnico para produtos de cereais, amidos, farinhas e farelos”. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil

- Brasil. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. (2012). Resolução da diretoria colegiada, RDC n° 54, de 12 de novembro de 2012. Dispõe sobre o “Regulamento técnico sobre informação nutricional complementar”. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil

- Coksever E, Saricoban C. Effects of bitter orange albedo addition on the quality characteristics of naturally fermented Turkish style sausages (sucuks) J Food Agric Environ. 2010;8(1):34–37. doi: 10.1234/4.2010.1429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crackel RL, Gray JI, Pearson AM, Booren AM, Buckley DJ. Some further observations on the TBA test as an index of lipid oxidation in meats. Food Chem. 1988;28(3):187–196. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(88)90050-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran S, Parkin KL. Química de alimentos de fennema. 5a. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- de Menezes Filho ACP, de Souza JCP, de Souza Castro CF. Evaluation of the physicochemical and technological parameters of flour produced from orange and watermelon agro-industry residues. Rev Agrar. 2019;12(45):399–410. doi: 10.30612/agrarian.v12i45.9143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elleuch M, Bedigian D, Roiseux O, Besbes S, Blecker C, Attia H. Dietary fibre and fibre-rich by-products of food processing: characterisation, technological functionality and commercial applications: A review. Food Chem. 2011;124(2):411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.06.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ginés JM, Fernández-López J, Sayas-Barberá E, Sendra E, Pérez-Alvarez JA. Lemon albedo as a new source of dietary fiber: application to bologna sausages. Meat Sci. 2004;67(1):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Bertram HC. Designing healthier comminuted meat products: effect of dietary fibers on water distribution and texture of a fat-reduced meat model system. Meat Sci. 2017;133:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henck JM, Bis-Souza CV, Pollonio MA, Lorenzo JM, Barretto AC. Alpha-cyclodextrin as a new functional ingredient in low-fat chicken frankfurter. Br Poult Sci. 2019;60(6):716–723. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2019.1664726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning SSC, Tshalibe P, Hoffman LC. Physico-chemical properties of reduced-fat beef species sausage with pork back fat replaced by pineapple dietary fibres and water. LWT. 2016;74:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henry SG, Darwish SM, Saleh A, Khalifa A. Carcass characteristics and nutritional composition of some edible chicken by-products. Egypt J Food Sci. 2019;47(1):81–90. doi: 10.21608/EJFS.2019.16364.1018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hygreeva D, Pandey MC, Radhakrishna K. Potential applications of plant based derivatives as fat replacers, antioxidants and antimicrobials in fresh and processed meat products. Meat Sci. 2014;98(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISO - International Organization for Standardization Animal and vegetable fats and oils-Preparation of methyl esters of fatty acids. ISO Geneve Method ISO. 1978;5509:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Leroux J, Langendorff V, Schick G, Vaishnav V, Mazoyer J. Emulsion stabilizing properties of pectin. Food Hydrocoll. 2003;17(4):455–462. doi: 10.1016/S0268-005X(03)00027-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Min B, Ahn DU. Factors in various fractions of meat homogenates that affect the oxidative stability of raw chicken breast and beef loin. J Food Sci. 2009;74(1):41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moarefian M, Barzegar M, Sattari M. Cinnamomum zeylanicum essential oil as a natural antioxidant and antibactrial in cooked sausage. J Food Biochem. 2013;37(1):62–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2011.00600.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira NADS, Winkelmann DOV, Tobal TM. Farinhas e subprodutos da laranja sanguínea-de-mombuca: caracterização química e aplicação em sorvete. Braz J Food Tech. 2019 doi: 10.1590/1981-6723.24618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña E, Lemos ALDSC, Selani MM, Spada FP, Almeida MAD, Contreras-Castillo CJ. Influence of animal fat substitution by vegetal fat on Mortadella-type products formulated with different hydrocolloids. Sci Agricola. 2015;72(6):495–503. doi: 10.1590/0103-9016-2014-0387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schönbach JK, Nusselder W, Lhachimi SK. Substituting polyunsaturated fat for saturated fat: A health impact assessment of a fat tax in seven European countries. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan B, Li X, Pan T, Zheng L, Zhang H, Guo H, Jiang L, Zhen S, Ren F. Effect of shaddock albedo addition on the properties of frankfurters. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52(7):4572–4578. doi: 10.1007/s13197-014-1467-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarladgis B, Pearson A, Dugan Júnior LR. Chemistry of the 2-thiobarbituric test for determination of oxidative rancidity in foods II. Formation of the TBA-malonaldehyde complex without acid-heat treatment. J Food Sci Agric. 1964 doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740150904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tozatti P, Rigo M, Bezerra JRMV, Córdova KRV, Teixeira ÂM. Utilização de resíduo de laranja na elaboração de biscoitos tipo cracker. RECEN. 2013;15(1):135–150. doi: 10.5935/RECEN.2013.01.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Troy DJ, Desmond EM, Buckley DJ. Eating quality of low-fat beef burgers containing fat-replacing functional blends. J Sci Food Agric. 1999;79(4):507–516. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(19990315)79:4<507:AID-JSFA209>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JD, Enser M, Fisher AV, Nute GR, Whittington FM, Richardson RI (2003) Effects of diets on fatty acids and meat quality. Opt Méditerr Ser A 67:133–141. http://om.ciheam.org/om/pdf/a67/06600032.pdf