Abstract

Young cereals contain higher quantities of nutrients such as sterols, γ-oryzanols, tocols and phenolic compounds than mature grains. They are more easily digested with low allergenic potential. Applications of young cereals include plant-based milk substitutes, substitution of wheat flour, malting, fructose and pigments production. Research on young cereals is scarce and mainly focused on botanical studies. This review focused on major young cereals (wheat, rice and corn) compositions, bioactive compounds and applications that will benefit future research in plant-based food and functional ingredients. During grain maturity, amylose content increased, whereas amylopectin content and its structure varied depending largely on grain type. In rice, non-significant differences in average chain length of amylopectin during grain maturity were reported, with protein contents of young rice and wheat higher than at their mature stages. High digestibility of the flowery-to-milky stage rice protein indicated lower allergen levels. Immune-reactive gluten was not found in young wheat. Young wheat contained high essential amino acids with a more balanced profile, particularly for lysine. The angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory effect of milky stage protein hydrolysate was higher than mature protein. Young grains contained less starch with more fiber and sugar. Antioxidant activity in young rice was high as it contained gamma-oryzanol, ascorbate, glutathione tocopherols and phenolic compounds. This review of the available information concerning the composition, properties and functional ingredients of immature cereals will assist future research in plant-based food and functional ingredients.

Keywords: Young cereal, Bioactive compound, Composition, Application

Introduction

Young or immature cereal grains are traditionally believed to have increased nutritional value and nourishment; they are also easy to digest. However, few studies are available on the chemical compositions, bioactive compounds, characterizations and applications of young cereal grains. Young durum wheat has been consumed as a functional food for thousands of years in the Middle East and North African countries together with wheat and rye (Lin and Lai 2011). In Thailand, young rice at the milky stage is consumed as a plant-based milk substitute called young rice milk, while dough stage rice is used to make a nourishing dessert from green rice flakes. Recently, several studies have focused on rice and wheat at different development stages. Wanly et al. (2018) investigated the structure of young waxy rice starches, while Jiamyangyuen et al. (2017) examined changes in bioactivities (especially antioxidant properties) and chemical compositions of different Thai rice varieties. Pantoa et al. (2020a, b) focused on the bioactivities and allergenicity of young rice protein and its hydrolysate as a new source of plant-based protein with high protein content and low allergens. Petrovska-Avramenko et al. (2016) and Kim et al. (2016) investigated the chemical composition, antioxidants and anti-proliferative activities in immature and mature wheat grains. Other research interests encompassed the applications and health benefits of foods made from young wheat such as phytic acid in Firiks (Ozkaya et al. 2018) and dietary fiber and phenolics that affected sourdough fermentation and the baking process of bread (Saa et al. 2017).

Young cereal starch structure and physiochemical properties alter during grain development and impact eating qualities. Starch structure studies included amylose and amylopectin content, MW distribution, degree of polymerization and starch granule morphology. Starch properties such as pasting and thermal properties are affected by its structure during grain development. Low allergenic cereal plant-based protein is favored by vegans and suitable for infants with lactose intolerance. Cereal-based milk is the first weaning food for infants in many countries. The proteins of immature cereal grains are hypoallergenic with low MW, and almost completely digested during the gastric phase as food formulations for sensitive groups. Young cereal protein is commercially feasible and offers beneficial applications for use as a plant-based protein alternative with high protein content, easy digestion, low allergens and high bioactivity. Young cereal protein hydrolysate acts against the proliferation of many cancer cells (such as HepG2, Coa2, Hela and HT-29) and is a good source of antioxidants and ACE inhibitory activity (Pantoa et al. 2020b).

Young cereals also have higher bioactive compounds than mature grains such as plant sterols, tocols and phenolic compounds. In young wheat, soluble fractions of the phenolic compounds hydroxyl-cinnamic, p-coumaric and sinapinic acid were higher, while insoluble-bound fractions increased with longer development stages (McCallum and Walker 1991). Young cereal grains also have high fiber and sugar content with less starch (Casiraghi et al. 2011; Nardi et al. 2003). Wholemeal flour made from immature durum wheat kernels contained larger amount of fructans, vitamin C and glutathione than mature kernels, indicating a higher level of antioxidant capacity (Paradiso et al. 2006), while whole immature rice grains contained gamma-oryzanol, antioxidants, vitamin B, tocopherols and phenolics as major bioactive compounds (Aguilar-Garcia et al. 2007).

However, no comprehensive review exists on the properties and bioactive compounds of immature or young cereals. Research on young cereals is scarce, with the focus mainly on botanical studies. This review of the available information on the composition, properties and functional ingredients of immature cereals will be beneficial for the future direction of new research in plant-based food and functional ingredients.

Cereal grain development stages

Development stages of cereal grains are defined according to their physiological changes, with counting starting from the day of flowering or silking to the fully ripe stage. Counting for the first day and period of each stage differ and are usually agreed by the stakeholders. For example, the Rice Department in Thailand assigns the first day after flowering (DAF) when 80% of rice in the field is flowering. Some use the term “days after pollination” (DAP) as interchangeable for DAF. Grain development in each stage is explained in Table 1. The five stages of rice grain development are divided as flowery (0–7 DAF), milky (8–14 DAF), dough (15–21 DAF), mature (22–28 DAF) and fully mature (29–35 DAF) (Butsat et al. 2009). Corn kernel development is classified into six stages using days after silking (DAS) as silking (0–8 DAS), blister (9–14 DAS), milk (15–21 DAS), dough (22–28 DAS), dent (29–30 DAS) and mature (31–55 DAS) (Larson 2020). For wheat, the reproductive phases are classified using grain phenotype as grain growth (1–4 DAF), grain enlargement or pre-milky (4–10 DAF), milky (11–16 DAF), soft dough (17–21 DAF), hard dough (22–30 DAF) and maturity or ripe (55 DAF) (Manning et al. 2008).

Table 1.

Description of the different development stages of rice, wheat, and corn

| Variety | Growth stage | DAF/DAS | Description | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Flowering | 0–7 | The florets on the main stem panicle start to reach anthesis. At least one caryopsis on the main stem panicle is elongated to the end of the husk; husks are green | Bustat et al. (2009) |

| Milky | 8–14 | The endosperm forms a milky liquid. At least one caryopsis on the main stem panicle has a caryopsis filling the cavity of the lemma and palea (husk); husks are still green | ||

| Dough | 15–21 | The milky liquid solidifies into a sticky white mass. At least one grain on the main stem panicle has a yellow husk | ||

| Mature | 22–28 | The grain is mature or ripe; the endosperm becomes hard and opaque. Grains on the main stem panicle start to have a brown husk | ||

| Fully mature | 29–35 | All grains have a brown husk | ||

| Corn | Silking | 0–8 | Silks emerge from the ear to receive pollen and begin to fertilize. The ovule has a silk attached which grows outside the husk at the ear tip to receive pollen to fertilize a kernel | Larson 2020 |

| Blister | 9–10 | After successful fertilization, kernels begin to develop; silks dry out and turn brown | ||

| Milky | 15–21 | Kernels are yellow outside. Starch accumulates rapidly and the kernels contain a milky white fluid | ||

| Dough | 22–28 | The grains remain soft and very moist, while the cob attains a light pink color | ||

| Dent | 29–30 | All kernels are fully dented. The kernel crown turns a bright, shiny, dark yellow color of mature kernels and obtains a firm consistency. This indicates the onset of hard starch development | ||

| Mature | 31–55 | Physiological maturity is attained on completion of kernel development | ||

| Wheat | Grain enlarge | 1–10 | The seed increases rapidly as the cells enclosing the embryo sac divide and expand. The watery ripe stage when squashed contains only water. Grains are green | Manning et al. 2008 |

| Milky | 11–16 | The grains are grown to almost full length and are one-tenth of their final weight | ||

| Soft dough | 17–21 | Filling continues. During the mid-milky stage, the grains start to change to a yellow color | ||

| Hard dough | 22–30 | All grains have a golden color | ||

| Harvest ripe | 55 | The grains stop growing and turn honey-brown or straw-colored, while and the tillers die off |

Young cereal starch

Starch granules

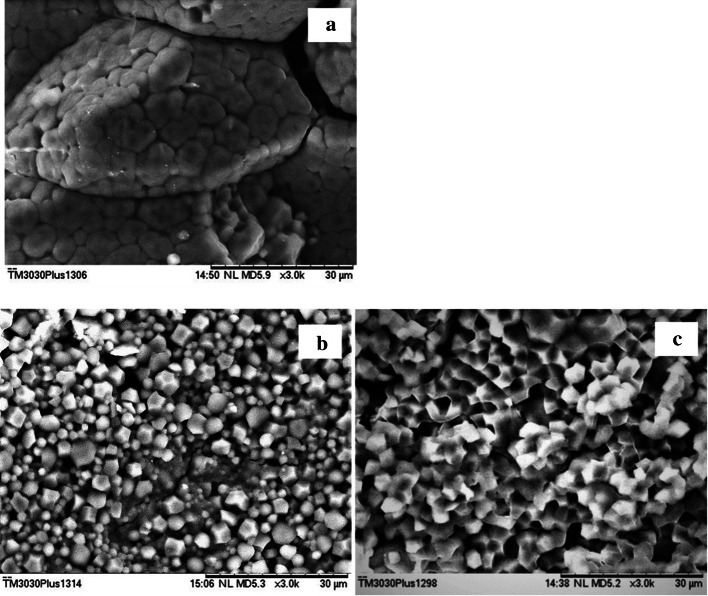

During the grain filling period, sugars are transformed into starch and reach a stable level at the mature stage. Rice starch granules are formed and packed in the amyloplasts during grain filling (Fig. 1a). A well-defined crystalline diffraction pattern of rice starch was exhibited at 4 DAF (Briones et al. 1968). During the first 10 DAF, the rice grain rapidly filled and starch granule size greatly increased, with the shape changing from spherical to polygonal by the end of the dough stage. During the grain filling period at 15 DAF, starch granules grew rapidly, assumed their shape and almost all the endosperm was filled (Juliano and Tuano 2019). Largest granule size was found at the mature stage, where the highest accumulation of starch and increase in cell numbers led to high pressure inside the granules. This resulted in a change in granule shape from spherical (Fig. 1b) to polygonal (Fig. 1c) (Jennings et al. 2002). The X-ray diffraction pattern of rice starch during the grain filling stage remained unchanged as typical A-type but crystallinity increased from 31 to 37.5% (Wanly et al. 2018). Corn starch granules were initiated at 6 DAS. Granule size was 1–4 μm with spherical shape and increased rapidly during 10–18 DAS. At 30 DAS, the starch granules reached 23 μm and changed to polygonal shapes (Li et al. 2007).

Fig. 1.

SEM images (3000x) of rice starch granules a packed in an amyloplast, b 10 DAF, mixture of small spherical and polygonal granules, c 20 DAF, more homogeneous larger polygonal shaped starch granules. Pictures taken by Dr. Thidarat Pantoa using a scanning electron microscope SU3500, Coax group cooperation, Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand on 22 March 2019

Amylose

Amylose content increased slightly with grain maturity. The iodine binding capacity of amylose of mature wheat at 6 weeks after anthesis (16–17 g iodine/100 g) was higher than the immature stage at 2 weeks after anthesis (12–13 g iodine/100 g) (Matheson 1971). The amylose content of Japonica rice increased from 9% (5 DAF) to 18.5% (17 DAF) (Asaoka et al. 1985), while the amylose content of normal corn also increased from 9.2% (12 DAF) to 24.2–24.4% (30 and 45 DAF) (Li et al. 2007). The apparent amylose fraction in wheat starch at the early stage (7–14 DAF) consisted of intermediate-type materials, while branched amylose appeared at the later stage (28–49 DAF) (Waduge et al. 2014). The molecular weight of amylose in corn showed a small decrease in average molecular weight in the late maturity stage, indicating the depolymerization of linear glucans (Praznik et al. 1987).

Amylopectin

The rate of amylopectin synthesis was higher than amylose at the early stage (Asoaka et al. 1985). The early waxy phase of wheat had larger amounts of amylopectin than the mature stage (Gambus et al. 2000). Waxy starch at the early stage showed a broad peak, with high polydispersity of branched starch components (Gumul et al. 2008), while the branch density of starch increased from 81.9 to 83.9% in the later stage of grain filling (Wanly et al. 2018). In rice grains, the blue value, average chain length, β-amylosis limit and iodine affinity remained constant during ripening. The chain length distribution of amylopectin showed a slight increase in long chain components, corresponding with an increase in iodine affinity (Hizukuri et al. 1995).

In corn, average amylopectin branch chain length of endosperm increased from DP 23.6 (10 DAS) to DP 26.9 (14 DAS) with a slight decline to DP 25.4 (30 DAS) and DP 24.9 (45 DAS) (Li et al. 2007). Short chain amylopectin (DP 6–12) of corn starch decreased from 21.1% (10 DAS) to 16.7% (20 DAS) and then increased to 17.4% (30 DAS) and 19.4% (45 DAS) (Li et al. 2007). In rice, several researchers reported that the average chain length of amylopectin was not significantly different during grain maturity (Asoaka et al. 1985) while Nakamura et al. (2019) reported very low levels of long chain amylopectin (DP > 35) in the early stage (4–8 DAF). Hizukuri et al. (1995) reported that numbers of large molecular size starch increased during the latter part of grain development, indicating an increase in branched molecules and a constant number of linear molecules. The average degree of polymerization number (DPn) and average degree of polymerization weight (DPw) of rice increased from 940 to 1130 and 2820 to 3700 at 7 DAF and 30 DAF, respectively. In wheat, the high MW amylopectin increased from 0.35 to 1.4 MDa in the early phase to late waxy phase, and reached 1.8 MDa in the fully mature phase (Gumul et al. 2008).

Thermal properties

Normal corn starch at 10 DAS exhibited lower gelatinization temperature and enthalpy because of the low proportion of long chain amylopectin (DP ≥ 37, 16.3%) and high proportion of short branch chain amylopectin (DP 6–24, 69.4%), which led to weak crystallinity (Li et al. 2007). This structure caused lower onset gelatinization temperature and enthalpy at young stage (63 °C and 14.5 J/g), which increased after maturation (67 °C and 15.6 J/g) (Li et al. 2007). The gelatinization temperature of corn starch rose with an increase in amylopectin chain length, while decrease in amylopectin short chains helped to develop well-organized crystallinity in the mature stages (Li et al. 2007). Short chain amylopectin (DP 6–12) of rice starch negatively correlated with gelatinization temperature (Kong et al. 2015). An opposite result was found in immature corn starch where onset and peak gelatinization temperatures were higher than for mature starch but enthalpy and temperature ranges were lower (Jennings et al. 2002). Starch in the endosperm was more uniform at the early stage and became more heterogeneous with cells of different physiological ages as the kernels matured. In the early stage, when starch granules were more homogeneous, the gelatinization temperature range became narrower. After maturation, the granules were more heterogeneous. Gelatinization started earlier in some granules, which increased the gelatinization temperature range (Jennings et al. 2002). Small and medium rice starch granules also negatively correlated with gelatinization temperature. In waxy rice starch, onset gelatinization temperature was steady at 61 °C throughout grain development (7–30 DAF) (Asaoka et al. 1985).

Pasting properties

Peak viscosity of immature corn starch was higher than mature starch as less amylose was presented at the early stages (Jennings et al. 2002). The amylose content limited the swelling power of starch granules. Immature corn starch contained more highly branched and large MW amylopectin, resulting in lower pasting temperature and higher peak viscosity than mature starch (Jennings et al. 2002). The increment of intrinsic viscosity positively correlated with average MW increase of amylopectin (Gumul et al. 2008), while short chain amylopectin (DP 6–12) positively correlated with breakdown viscosity. Starch granules in immature kernels were loosely arranged or less compact, hence they required less energy to gelatinize (Jennings et al. 2002).

Immature wheat starch paste exhibited higher plasticity and required higher shear stress to achieve yield stress compared with mature wheat starch (Gambus et al. 2004). Immature wheat starch pastes also showed higher thixotropic behavior, as the ability to rebuild the structure quickly after shearing force (Gambus et al. 2004). Low paste viscosity of immature wheat starch was also related to strong α-amylase activity, causing starch hydrolysis at the early stages (Iametti et al. 2006).

Young cereal sugars and dietary fibers

Young wheat grains had less starch but more fiber and sugar than mature wheat (Casiraghi et al. 2011). During the ripening stage, free sugar was converted into starch, causing a continuous reduction in total sugar content during grain development (Petrovska-Avramenko et al. 2016). The milky stage of wheat contained much higher fructose (around 7 times) than at the mature stage and was suggested for use in fructose production (D’Egidio et al. 1997). In rice, glucose and fructose content at 15–18 DAF were higher than in the mature grains. Young rice contained galactose and traces of arabinose that were involved in building the cell walls (Lin and Lai 2011). The reducing sugar content in young rice grains ranged 0.2–0.5% (Ji et al. 2013), while reducing sugar in 74 DAS corn was 6.4% and decreased to 1.7% at maturity (Xu et al. 2010). Free sugars in rice reached maximum levels at about 9 DAF and then reduced after starch was assimilated to a minimum at 15 DAF (Fig. 2) (Singh and Juliano 1977).

Fig. 2.

Accumulation of starch, free sugar, protein and free amino N of rice during grain development. Figure adapted with permission from Juliano and Tuano (2019)

Total dietary fiber content varied with maturity stages and cultivars. The dietary fiber contents of young rice and wheat (5.7–7.0% and 19.1–19.8%) were higher than at the mature stages (4.6–6.0% and 14–17.3%) (Table 2). The soluble dietary fiber fractions in young stage rice and wheat (0.6–1.0% and 4.5–5.5%) were also higher than at the mature stage (0.3% and 4.2–4.8%) (Lin and Lai 2011; Saa et al. 2017). Young durum wheat contained higher dietary fiber (19.8%); therefore, the consumption of young durum wheat improved the proliferation of lymphocytes and immune response stimulation with decrease in plasma cholesterol and triglycerides and a positive effect on lipid composition (Merendino et al. 2006). Wholemeal flour made from young durum wheat kernels contained higher amounts of fructan, ascorbate and glutathione than the mature kernels, indicating a higher level of antioxidant capacity (Nardi et al. 2003; Paradiso et al. 2006).

Table 2.

Protein and dietary fiber of cereal grains at different development stages

| Variety | Development stage | Protein (%) | Dietary fiber (%) | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insoluble | Soluble | Total | ||||

| Rice | ||||||

| Waxy Indica, Non-waxy Japonica |

15 DAF 18 DAF Mature |

4.7–6.1 5.2–6.3 4.3–5.7 |

0.6–1.0 0.6–0.7 0.3 |

5.7–6.7 5.8–7.0 4.6–6.0 |

Lin and Lai 2011 | |

| Japonica |

15 DAF 25 DAF Mature |

7.5–7.9 7.6–7.7 6.9–7.1 |

3.7–3.8 3.0–3.6 3.6–3.8 |

Ji et al. 2013 | ||

| White rice, Color rice |

Flowery Milky Dough Mature |

9.2–9.8 9.3–11.5 7.7–8.8 7.2–8.6 |

Pantoa et al. 2020a | |||

| Wheat | ||||||

| Durum wheat |

Milky Mature |

11.6–13.4 10.5–11.2 |

13.6–14.6 11.4–13.0 |

4.5–5.5 4.2–4.8 |

19.1–19.2 16.3–17.3 |

Saa et al. 2017 |

| Durum wheat |

Young Mature |

15.0 16.5 |

19.8 14.0 |

Merendino et al. 2006 | ||

| Green wheat |

Young Mature |

12.0 14.0 |

19.5 14.5 |

Yang et al. 2012 | ||

| Wheat flour |

Young Mature |

12.4 10.5 |

10.3 1.7 |

Kim and Kim 2017 | ||

| Corn | ||||||

| Yellow corn |

74 DASe 86 DASe 98 DASe 116 DASe |

13.1 10.2 10.3 8.8 |

Xu et al. 2010 | |||

Young cereal protein and protein hydrolysate

Total protein in young stage rice (7.5–11.5%) and wheat (11.6–15.1%) was higher than at the mature stage (6.9–7.1% and 10.5–13.8%, respectively) (Kim et al. 2007; Ji et al. 2013; Saa et al. 2017; Pantoa et al. 2020a). Rice grain protein started to accumulate at 4 DAF, reached maximum at 8 DAF and decreased after 10–13 DAF as higher starch was produced (Luthe 1983). A major protein in rice was glutelin (80%) which increased rapidly from 5 DAF and reached maximum at 30 DAF, whereas other storage proteins occurred at 8–10 DAF (Juliano and Tuano 2019). Results in Table 2 showed that protein contents of rice in the flowery, milky, dough and mature stages were 9.2, 9.3, 7.7 and 7.2% in white rice and 9.8, 11.5, 8.8 and 8.6% in colored rice, respectively. Milky stage rice had the highest protein content (9.3–11.5%, db) which was higher than the mature stage (8.6%, db) (Pantoa et al. 2020a). As indicated in Fig. 2, highest soluble protein and free amino N content of rice were observed at the young stage (10–12 DAF) (Singh and Juliano 1977). Similarly, young stage corn exhibited higher protein (13.1%) than the fully mature stage (8.8%) (Xu et al. 2010). Albumin content in corn decreased from 3.9% in the young stage (74 DAS) to 0.7% in the mature stage (Xu et al. 2010). Landry and Moureaux (1976) reported that albumin and globulin contents first increased and then decreased after grain ripening. Young wheat protein was reported to be a good source of plant-based protein as it contained higher essential amino acids and a better-balanced amino acid profile, particularly for lysine content (4.5 mg/100 g) than the mature stage (2.9 mg/100 g) (Nardi et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2007).

Allergenic potential of young cereal grain protein

Pantoa et al. (2020a) reported on potential protein allergens in rice including non-specific lipid transfer protein-1, α-amylase/trypsin inhibitor family proteins, α-globulin, glyoxalase-1, globulin-like protein, protein disulfide isomerase, granule-bound starch synthetase, embryo globulin and α-glucosidase, corresponding with MW of 14–16, 25–26, 30–33, 52, 55, 60, 63 and 90 kDa. Mature stage rice contained an abundance of prolamin that had low digestibility, causing food allergy as many food allergens are resistant to gastric digestion (Kubota et al. 2014). However, reports on the immediate hypersensitivity reaction toward rice are limited (Pantoa et al. 2020a). In vitro digestibility revealed that flowery-to-milky stage white rice had lower allergens (13–14, 37–39 kDa in colored rice and 52 kDa in white rice) than the dough-to-mature stage (Pantoa et al. 2020a). Protein digestibility at the gastric phase rapidly decreased with complete digestion within 0.30 min for 13–14, 22–23 and 37–39 kDa. Thus, young rice at the flowery-to-milky stage was proposed for use as a new source of rice protein with high protein contents (9.19–11.48%) compared to rice bran (8.9%) with very low possibility of allergens. The main allergens that discriminated the flowery-to-milky stage from the dough-to-mature stages in white rice were 52 kDa globulin-like protein, 13–14 kDa prolamin and in colored rice 13–14 kDa prolamin (Pantoa et al. 2020a).

Bioactivities of young rice protein hydrolysates

The DPPH and iron chelating activities of alcalase® protein hydrolysates obtained from milky stage rice were higher than its native protein. Young rice protein at the flowery-to-milky stage had relatively low MW and was easily digested into small peptides (Pantoa et al. 2020b).

Antioxidant activities of peptides can also be generated under the human digestive system (Lin and Lai 2011). Colored rice hydrolysate exhibited higher anti-proliferation of liver cancer cells (HepG2) than white rice at all grain development stages (Pantoa et al. 2020b). The proliferation of Caco-2 cells decreased from 34 to 12% after treatment with young and mature wheat extract (40 mg/mL). The E50 values of Hela cells and HT-29 cells were lower after treatment with young wheat extract (31.4, 39.3 mg/mL, respectively) than mature wheat extract (56, 73.7 mg/mL, respectively) (Kim and Kim 2016). The ACE inhibitory activity of protein hydrolysate in the milky stage of white rice (96.3%) and flowery stage of colored rice (78.5%) was higher than its native protein (69.1–72.8%) (Pantoa et al. 2020b).

Young cereal bioactive compounds

Phenolic compounds

Phenolic contents of different cereals at various development stages are summarized in Table 3. Young wheat showed higher antioxidant activities than at the mature stage because of higher free, bound and total phenolic compounds, while antioxidant activity of cereals was mainly governed by phenolic compounds, especially the free phenolic fraction. Other phenolics such as syringic, chlorogenic, protocatechuic, hydroxybenzoic, vanillic and cinnamic acid were observed below detection level in all development stages (Lin and Lai 2011). In wheat, soluble fractions of phenolic compounds such as hydroxyl-cinnamic, p-coumaric and sinapinic acid decreased, while insoluble-bound fractions increased with longer seed development (McCallum and Walker 1991). Variation in phenolic content was largely affected by factors such as genetic, rate of endosperm/outer layer development, rate of phenolic acid bound to cell walls and exposure to biotic stresses (Muroi et al. 2009). By contrast, total phenolic content of corn increased from milky stage (4.8–12.3 mg GAE/g, db) to mature stage (6.6–19.7 mg GAE/g, db). Creamy yellow corn had lower total phenolic content than purplish black or dark colored genotypes (Harakotr et al. 2014). The DPPH, FRAP and TEAC antioxidant activity of corn showed an increase with maturation. The DPPH scavenging activity increased from milky stage (0.2–11.7 µmol TEAC/g, db) to mature stage (5.6–21.6 µmol TEAC/g, db) (Harakotr et al. 2014).

Table 3.

Phenolic and ferulic acid content of cereals at different development stages

| Variety | Stage | Phenolic content (mg GAE/100 g, db) | Ferulic acid (µg/g, db) | Ref | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free | Soluble | Insoluble | Total | Free | Soluble | Insoluble | Total | ||||

| Rice | Waxy indica, Non-waxy Japonica |

15 DAF 18 DAF Mature |

20–280 20–350 10–80 |

30–90 30–40 50 |

150–490 80–220 120–400 |

260–800 150–600 180–560 |

12.4–38.8 8.1–25.1 5.8–10.7 |

6.8–103.2 6.4–21.8 10.7–13.1 |

200.0–443.2 98.0–201.2 124.4–184.3 |

219.5–490.6 135.2–232.7 148.2–200.8 |

Lin and Lai 2011 |

| White, Red, Black |

Flowery Milky Dough Mature Full mature |

49–69 35–141 29–119 25–112 28–116 |

Jiamyangyuen et al. 2017 | ||||||||

| White, Red, Black |

7 DAF 14 DAF 21 DAF Mature |

14–201 12–143 10–113 9–56 |

33–422 23–354 14–232 13–75 |

29–69 21–52 19–49 18–82 |

42.7–149.5 40.4–109.1 40.3–124.9 42.8–179.2 |

Shao et al. 2014 | |||||

| Wheat | Durum wheat |

Milky Full mature |

63–68 68–74 |

169–184 191–200 |

232–252 259–274 |

Saa et al. 2017 | |||||

| Hard wheat |

Young Mature |

144 121 |

388 324 |

532 446 |

Kim and Kim 2016 | ||||||

| Corn | Normal yellow corn |

74 DASe 86 DASe 98 DASe 116 DASe |

33 18 28 6 |

120 67 51 41 |

276 318 287 233 |

430 404 365 281 |

Xu et al. 2010 | ||||

| Waxy corn & Normal yellow corn |

86 DASe 98 DASe 116 DASe |

67–255 34–293 23–388 |

14–24 10–14 4–9 |

Hu and Xu 2011 | |||||||

Ferulic acid

Ferulic acid represents 50–65% of total bound phenolic compounds and is the predominant phenolic acid in cereals at all development stages. Ferulic acid was concentrated in the insoluble fraction of rice bran (Irakli et al. 2012). Highest ferulic acid was found at the young stage and declined during grain ripening (McKeehen et al. 1999). As documented in Table 3, a progressive decrease of ferulic acid in rice was observed in all free, soluble and insoluble fractions after maturation (Lin and Lai 2011). The biological availability of ferulic acid in food matrix depended on the proportion of free and soluble esters of ferulic acid rather than the total quantity. Similarly, ferulic acid content in wheat also decreased after maturation because the rate of endosperm development was faster than the rate of bran production during grain filling. There was also an increase in bonding between the phenolics and cell wall materials during maturation (McKeehen et al. 1999).

Flavonoids

Antioxidant activity highly correlated with total flavonoids and the total phenolic fraction of rice (Lin and Lai 2011). Anthocyanin is a polyphenolic pigment, with content varying by genotype, growing stage, growing environment and evaluation method (Xu et al. 2010). The main anthocyanin found in the milky stage of corn was cyanidin-3(3″,6″-dimalonylglucoside) and in the mature stage was cyanidin-3(6″-malonylglucoside). The predominant anthocyanin of purplish-black genotype was cyanindin-3-glucoside (Harakotr et al. 2014). Black waxy corn exhibited highest phenolics, anthocyanin and antioxidant activity, whereas yellow corn had a higher proportion of carotenoid than white corn at all maturity stages (Hu and Xu 2011). Cyanidin-3-glucoside and peonidin-3-glucoside were the main anthocyanin compounds in black rice and availability was higher at the young stage (Ryu et al. 1998). Anthocyanin content of mature stage corn was higher than at the young stage (Table 4), while monomeric anthocyanin content in corn increased during development stages. The milky stage of purplish black waxy corn had higher acylated anthocyanin (67.1–88.2%) than the mature stage (46.2–83.6%) and showed favorable stability for use in the food industry (Harakotr et al. 2014). Anthocyanin content in colored rice (175 mg/100 g) was lower than corn (276 mg/100 g). Results in Table 4 showed that total, free and soluble flavonoid contents of young rice at milky-dough stage and young wheat were higher than mature stage, while the insoluble fraction of flavonoids was higher in rice at the mature stage (Kim and Kim 2016).

Table 4.

Flavonoid and anthocyanin contents of young cereal grains

| Variety | Growing stage | Flavonoid (mg CE/100 g, db) | Anthocyanin μgCGE/g, db |

Ref | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free | Soluble | Insoluble | Total | ||||

| Rice | |||||||

| Waxy indica, Non-waxy Japonica |

15 DAF 18 DAF Mature |

5–81 25–95 15–20 |

7–60 10–25 18–20 |

39–26 40–98 35–110 |

125–360 100–150 90–140 |

Lin and Lai 2011 | |

| White, Red, Black rice |

Flowery Milky Dough Mature Fully mature |

23–76 24–142 19–168 21–115 21–96 |

0 0–30 0–340 0–370 |

Jiamyangyuen et al. 2017 | |||

|

White, Red, Black Rice |

7 DAF 14 DAF 21 DAF Mature |

266 1747 1722 876 |

Shao et al. 2014 | ||||

| Wheat | |||||||

| Durum |

Milky Mature |

16.1–26.4 18.6–24.6 |

16.4–22.2 17.4–19.2 |

32.5–48.6 37.7–42.0 |

Saa et al. 2017 | ||

| Hard |

Immature Mature |

22 18 |

451 216 |

473 234 |

Kim and Kim 2016 | ||

| Corn | |||||||

| Waxy corn |

Milky Mature |

0.6–694.6 0.8–1438.6 |

Harakotr et al. 2014 | ||||

| Black waxy |

86 DASe 98 DASe Mature |

635.8 1380.8 2761.1 |

Hu and Xu 2011 | ||||

Tocopherols, tocotrienols and γ-oryzanols

α-Tocopherol (α-T), γ-tocotrienols (γ-T3) and α-tocotrienols (α-T3) were the main tocols found in rice (Lin and Lai 2011). Total tocols in young rice (36–59.3 μg/g) were higher than in mature rice (26.3–36.0 μg/g). In mature rice, tocopherol content (6.7–13.31 μg/g) was lower than tocotrienol (37.5–52.5 μg/g) (Aguilar-Garcia et al. 2007), while black and red rice predominantly contained α-T, which showed the highest antioxidant DPPH activity (Yawadio et al. 2007). The α-T was the most abundant tocol in rice, with content in the dough stage (15–18 DAF) higher (24.5–25.6 μg/g) than at the mature stage (8.3–12.7 μg/g), while γ-T3, the main tocotrienol in rice, was higher in young rice (10.0–14.1 μg/g) than mature grain (5.1–6.7 μg/g) (Table 5). By contrast, tocopherols, tocotrienols and tocols of young wheat (1.8–8.0, 1.9, 4.0 μg/g, respectively) were lower than mature wheat (3.0–16.5, 2.1, 5.8 μg/g, respectively) (Yang et al. 2012; Kim and Kim 2016).

Table 5.

Tocopherols, tocotrienol and oryzanol contents of young cereal grains

| Variety | Development Stage | Tocopherols (µg/g, db) | Tocotrienols (µg/g, db) | Total tocols (µg/g, db) |

Oryzanols (µg/g, db) |

Ref | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-T | β-T | γ-T | δ-T | α-T3 | β-T3 | γ-T3 | δ-T3 | |||||

| Rice | ||||||||||||

| Waxy indica, Non-waxy Japonica |

15 DAF 18 DAF Mature |

17.3–25.6 14.5–24.5 8.3–12.7 |

1.9–2.7 2.1–2.5 1.4–2.8 |

3.6–3.8 3.2–4.1 0.9–1.8 |

1.0–1.5 1.0–1.5 0.7–1.5 |

8.3–10.1 7.6–8.6 3.9–7.5 |

11.4–14.1 10.0–14.1 5.1–6.7 |

1.5–2.0 1.4–2.0 0.7–1.1 |

45.7–59.3 40.8–59.3 23.7–30.4 |

321–328 328–349 351–406 |

Lin and Lai 2011 | |

| Japonica |

15 DAF 25 DAF Mature |

4.1–6.9 7.1–7.7 6.4–6.7 |

5.7–6.1 3.8–4.4 1.5–1.7 |

4.8–5.1 4.4–4.8 5.2–5.7 |

13.4–18.6 15.8–18.6 9.9–11.4 |

29.5–36.0 30.7–33.5 24.4–26.3 |

Ji et al. 2013 | |||||

| Wheat | ||||||||||||

| Medium hard wheat |

Young Mature |

6.0 14.0 |

2.0 2.5 |

Yang et al. 2012 | ||||||||

| Hard wheat |

Young Mature |

13 24 |

5 6 |

19 21 |

40 58 |

Kim and Kim 2016 | ||||||

Application of young cereal grains

Plant-based milk substitute

Only soy and rice are recommended as alternative sources of plant protein for infants with lactose intolerances (Pantoa et al. 2020a). However, the biological values of soy and rice protein are lower than cow’s milk and have often been debated. Soy protein contains some food allergens and is not recommended for preterm infants, with use restricted to infants aged over 6 months. A rice-based formula is considered a better alternative since rice is known as a low allergenic food. Rice protein exhibited an efficiency ratio of 2–2.5, similar to milk casein (2.5), with no digestive problems after ingestion (Helm and Bruks 1996). Plant-based milk substitutes such as almond, oat, coconut, soy and rice milk are popular among health-conscious consumers, vegans and those with lactose intolerances. Most commercial rice milk is produced from mature stage rice and composed mainly of starch, with few rice milk drinks made from young rice, especially in the milky stage.

Wheat flour substitution

Immune-reactive gluten was not found in young wheat grain prior to 13 DAF (Iametti et al. 2006). Thus, young wheat flour was used to produce gluten-free foods such as pasta, bread and biscuit. Young durum wheat is also used in traditional Turkish food “Firik” which contains high dietary fiber (12.2–20.4 g/100 g) (Ozkaya et al. 2018). However, lack of gluten hampered the use of young wheat grain because of its poor structural property (D’Egidio et al. 1998; Saa et al. 2017). Young wheat flour dough had higher tensile strength and lower extensibility than mature wheat dough. Dietary fiber and protein content of young wheat (5.0% and 11.5%, respectively) were higher than mature wheat flour (3.1% and 8.5%, respectively) and this affected the network structure of the dough (Katagiri et al. 2011).

Bread made from young wheat had higher firmness with tougher crumb (Mujoo and Ng 2003), while sour dough bread made from 10% young wheat flour (26–36 DAF) increased in hardness by 50% with reduction in cohesiveness, springiness and resilience. Slowly digestible starch of sour dough bread (8.86–9.35%) was higher than the control (3.13%) because of high fiber in the immature stage. However, the estimated glycemic index of sour dough bread made from young wheat remained high because of the high reducing sugar content in young wheat flour (Cetin-Babaoglu et al. 2020). High bran content in young wheat flour and high acidity of sour dough resulted in weakening of the gluten network by proteolytic and amylolytic activity. Dough structure was soft and sticky, which subsequently impacted gas retention resulting in lower volume and greater firmness of the bread. Loaf volume of bread made from young wheat flour reduced from 642.9 to 462.3 cm3 (Pepe et al. 2013). The recommended level of young wheat flour was limited to 20% for leavened and unleavened bread (Levent and Bilgicli 2017), while addition of young wheat flour in “Madeleines” cake increased hardness and chewiness because of the high total dietary fiber (Kim and Kim 2017). Small addition (3%) of early waxy stage wheat and rye flour decreased bread crumb hardness due to the high resistance to swelling and pasting of the young starch granules (Gambus et al. 2004).

Addition of young wheat flour in pasta (30%) did not affect cooking and textural quality. Young wheat flour improved firmness and decreased stickiness in pasta. However, green and yellow coloration increased because of the higher bran content, together with an increase in browning reaction from the higher sugar content. Immature wheat was proposed as an interesting naturally enriched source of fructo-oligosaccharides and fiber (Casiraghi et al. 2013).

Others

Young wheat and barley are used to improve the quality of malt through their high amylolytic activity (Lysak et al. 1996), while the pasting characteristics of young wheat starch are utilized as a thickening agent for food products such as mayonnaise (Gambus et al. 2004). High absorption capacity and viscosity characteristics of young wheat flour are also used in meat pies which meet the protein to fat ratio. Young wheat grain can be used directly in soups and baby foods. Higher fructose in the milky stage of wheat was strongly recommended to use for fructose production (D’Egidio et al. 1997). Moreover, the pigment in young corn was recommended for use as dietary supplements, cosmetics and as food additives because of its high antioxidant properties (Harakotr et al. 2014).

Conclusion

Different physiology and composition of young stage cereals impacted functionalities, allergenicity, bioactivities and applications. Young cereals are composed of healthy ingredients such as low allergenic protein, dietary fiber, oligosaccharides and bioactive compounds such as phenolics, anthocyanins, tocopherols, tocotrienols and γ-oryzanols. Young cereal extract was proved to exhibit higher bioactivities such as antioxidant, ACE inhibitory activity and anticancer properties than at the mature stage. Young cereal starches or flours had lower allergen and produced low gluten foods suitable for highly sensitive consumers. Moreover. young cereals were a good source of functional food ingredients such as bioactive peptides, low allergen plant-based protein, antioxidants, colorants, thickening agents, low gluten and easy to digest foods. However, young cereals also had some shortcomings such as high sugar, high glycemic index values and low yield. These factors need to be addressed as trade-offs in future economic production of young cereal crops.

Acknowledgements

The first author acknowledges the Sri Lanka Council for the Agricultural Research Policy (SLCARP) grant as part of the PhD scholarship funding.

Abbreviations

- ACE

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- CE

Catechin equivalent

- CGE

Cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalent

- DAF

Days after flowering

- DAS

Days after silking

- DP

Degree of polymerization

- DPn

Average degree of polymerization number

- DPw

Average degree of polymerization weight

- EECC

EDTA equivalent chelating capacity

- FRAP

Ferric reducing power

- GAE

Gallic acid equivalent

- TEAC

Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity

- MW

Molecular weight

Authors’ contributions

Prisana Suwannaporn is developing the concept idea, funding acquisition, supervision, writing-review & editing manuscript, and project administration. R.A.A. Ranathunga is doing data collection, secondary data analysis, and writing original draft.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest, all authors are agree and informed before submission.

Consent for publication

The image used is modified and was asked for permission from the publishers.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aguilar-Garcia C, Gavino G, Baragaño-Mosqueda M, Hevia P, Gavino VC. Correlation of tocopherol, tocotrienol, γ-oryzanol and total polyphenol content in rice bran with different antioxidant capacity assays. Food Chem. 2007;102:1228–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asaoka M, Okuno K, Sugimoto Y, Fuwa H. Developmental changes in the structure of endosperm starch of rice (Oryza sativa L.) Agr Biol Chem. 1985;49:1973–1978. doi: 10.1080/00021369.1985.10867028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briones VP, Magbanua LG, Juliano BO. Changes in physicochemical properties of starch of developing rice grain. Cereal Chem. 1968;45:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Butsat S, Weerapreeyakul N, Siriamornpun S. Changes in phenolic acids and antioxidant activity in Thai rice husk at five growth stages during grain development. J Arg Food Chem. 2009;57:4566–4571. doi: 10.1021/jf9000549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casiraghi MC, Zanchi R, Canzi E, Pagani MA, Viaro T, Benini L, D’Egidio MG. Prebiotic potential and gastrointestinal effects of immature wheat grain (IWG) biscuits. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;99:795–805. doi: 10.1007/s10482-011-9553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casiraghi MC, Pagani MA, Erba D, Marti A, Cecchini C, D'Egidio MG. Quality and nutritional properties of pasta products enriched with immature wheat grain. Int J Food Sc Nutr. 2013;64:544–550. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2013.766152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetin-Babaoglu H, Arslan-Tontul S, Akın N. Effect of immature wheat flour on nutritional and technological quality of sourdough bread. J Cereal Sci. 2020;94:103000. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2020.103000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Egidio MG, Cecchini C, Corradini C, Donini V, Pignatelli V, Cervigni T. Innovative uses of cereals for fructose production. In: Campbell GM, Webb C, McKee SL, editors. Cereals. USA: Springer, Boston, MA; 1997. pp. 143–144. [Google Scholar]

- D’Edigio M, Cecchini C, Desiderio E, Cervigni T. Immature wheat grains as functional food. Brno (Czech Republic): Paper presented at the Cereals for Human Health and Preventive Nutrition; 1998. pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gambus H, Gumul D, Pielichowski K, Lewandowicz G, Nowotna A, Ziobro R (2000) Gelatinization of starch from immature cereal kernels. Paper presented at the IX international starch Convention, Krakow

- Gambus H, Gumul D, Juszczak L. Rheological properties of pastes obtained from starches derived from immature cereal kernels. Starch-Stärke. 2004;56:225–231. doi: 10.1002/star.200300240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gumul D, Gambus H, Ziobro R, Pikus S. Changes in molecular mass and crystalline structure of starch isolated from immature cereals. Polish J Food Nutr Sci. 2008;58:463–469. [Google Scholar]

- Harakotr B, Suriharn B, Tangwongchai R, Scott MP, Lertrat K. Anthocyanins and antioxidant activity in coloured waxy corn at different maturation stages. J Funct Foods. 2014;9:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helm RM, Burks AW. Hypoallergenicity of rice protein. Cereal Foods World. 1996;41:839–843. [Google Scholar]

- Hizukuri S, Takeda Y, Juliano BO (1995) Structural changes of non-waxy starch during development of rice grains. Presented at the progress in plant polymeric carbohydrate research, proceedings international symposium plant polymeric carbohydrate. Berlin, Germany

- Hu QP, Xu JG. Profiles of carotenoids, anthocyanins, phenolics, and antioxidant activity of selected color waxy corn grains during maturation. J Agri Food Chem. 2011;59:2026–2033. doi: 10.1021/jf104149q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iametti S, Bonomi F, Pagani MA, Zardi M, Cecchini C, D'Egidio MG. Properties of the protein and carbohydrate fractions in immature wheat kernels. J Agri Food Chem. 2006;54:10239–10244. doi: 10.1021/jf062269t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irakli MN, Samanidou VF, Biliaderis CG, Papadoyannis IN. Development and validation of an HPLC-method for determination of free and bound phenolic acids in cereals after solid-phase extraction. Food Chem. 2012;134:1624–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings SD, Myers DJ, Johnson LA, Pollak LM. Effects of maturity on corn starch properties. Cereal Chem. 2002;79:703–706. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.2002.79.5.703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji CM, Shin JA, Cho JW, Lee KT. Nutritional evaluation of immature grains in two Korean rice cultivars during maturation. Food Sci Biotech. 2013;22:903–908. doi: 10.1007/s10068-013-0162-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiamyangyuen S, Nuengchamnong N, Ngamdee P. Bioactivity and chemical components of Thai rice in five stages of grain development. J Cereal Sci. 2017;74:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2017.01.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano BO, Tuano APP. 2–Gross structure and composition of the rice grain. In: Bao J, editor. rice. 4. AACC International Press; 2019. pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri M, Masuda T, Tani F, Kitabatake N. Expression and development of wheat proteins during maturation of wheat kernel and the rheological properties of dough prepared from the flour of mature and immature wheat. Food Sci Tech Res. 2011;17:111–120. doi: 10.3136/fstr.17.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Kim SS. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities in immature and mature wheat kernels. Food Chem. 2016;196:638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Kim SS. Utilisation of immature wheat flour as an alternative flour with antioxidant activity and consumer perception on its baked product. Food Chem. 2017;232:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MC, Lee KS, Lee BJ, Kwon BG, Ju JI, Gu JH, Oh MJ. Changes in the physicochemical characteristics of green wheat during maturation. Korean J Food Nutr. 2007;36:1307–1313. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2007.36.10.1307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X, Chen Y, Zhu P, Sui Z, Corke H, Bao J. Relationships among genetic, structural, and functional properties of rice starch. J Agri Food Chem. 2015;63:6241–6248. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota M, Saito Y, Masumura T, Watanabe R, Fujimura S, Kadowaki M. In vivo digestibility of rice prolamin/protein body-I particle is decreased by cooking. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2014;60(4):300–304. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.60.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry J, Moureaux T. Quantitative estimation of accumulation of protein fractions in unripe and ripe maize grain. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1976;25:343–360. doi: 10.1007/BF02590310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larson E (2020) Corn reproductive stages and their management implications. Mississippi crop situation. https://www.mississippi-crops.com/2020/06/27/corn-reproductive-stages-and-their-management-implications/ Accessed: 20 Nov 2020

- Levent H, Bilgicli N. Effects of immature wheat on some properties of flour blends and rheological properties of dough. Qual Assur Saf Crop Foods. 2017;9:55–65. doi: 10.3920/QAS2015.0734. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Blanco M, Jane J. Physicochemical properties of endosperm and pericarp starches during maize development. Carbohydr Polym. 2007;67:630–639. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2006.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PY, Lai HM. Bioactive compounds in rice during grain development. Food Chem. 2011;127(1):86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.12.092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luthe DS. Storage protein accumulation in developing rice (Oryza sativa L.) seeds. Plant Sci Lett. 1983;32:147–158. doi: 10.1016/0304-4211(83)90110-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lysak J, Fornal L, Gambus H, Gruchała L, Panasik M, Pior H. Preliminary studies on the quality and usability of wheat in early stages of kernel maturity. Polish J Food Nutr Sci. 1996;46:68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Manning B, Schulze K, McNee T. Grain development. In: White J, Edwards J, editors. Wheat growth and development, NSW department of primary industries. Australia: NSW; 2008. pp. 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Matheson NK. Amylose changes in the starch of developing wheat grains. Phytochemistry. 1971;10:3213–3219. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)97376-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum JA, Walker JRL. Phenolic biosynthesis during grain development in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) III. Changes in hydroxycinnamic acids during grain development. J Cereal Sci. 1991;13:161–172. doi: 10.1016/S07335210(09)80033-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKeehen JD, Busch RH, Fulcher RG. Evaluation of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) phenolic acids during grain development and their contribution to Fusarium resistance. J Agri Food Chem. 1999;47:1476–82. doi: 10.1021/jf980896f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merendino N, D'Aquino M, Molinari R, Gara LD, D'Egidio MG, Paradiso A, Cecchinie C, Corradini C, Tomassia G. Chemical characterization and biological effects of immature durum wheat in rats. J Cereal Sci. 2006;43:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2005.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mujoo R, Ng PKW. Physicochemical properties of bread baked from flour blended with immature wheat meal rich in fructooligosaccharides. J Food Sci. 2003;68:2448–2452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb07044.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muroi A, Ishihara A, Tanaka C, Ishizuka A, Takabayashi J, Miyoshi H, Nishioka T. Accumulation of hydroxycinnamic acid amides induced by pathogen infection and identification of agmatine coumaroyltransferase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2009;230:517–527. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-0960-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Ono M, Ozaki N. Structural features of α-glucans in the very early developαmental stage of rice endosperm. J Cereal Sci. 2019;89:102778. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2019.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nardi S, Calcagno C, Zunin P, D'Egidio MG, Cecchini C, Boggia R, Evangelisti F. Nutritional benefits of developing cereals for functional foods. Cereal Res Commun. 2003;31:445–452. doi: 10.1007/BF03543377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkaya B, Turksoy S, Ozkaya H, Baumgartner B, Ozkeser I, Koksel H. Changes in the functional constituents and phytic acid contents of firiks produced from wheats at different maturation stages. Food Chem. 2018;246:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoa T, Baricevic-Jones I, Suwannaporn P, Kadowaki M, Kubota M, Roytrakul S, Mills ENC. Young rice protein as a new source of low allergenic plant-base protein. J Cereal Sci. 2020;93:102970. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2020.102970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoa T, Kubota M, Suwannaporn P, Kadowaki M. Characterization and bioactivities of young rice protein hydrolysates. J Cereal Sci. 2020;95:103049. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2020.103049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso A, Cecchini C, De Gara L, D'Egidio MG. Functional, antioxidant and rheological properties of meal from immature durum wheat. J Cereal Sci. 2006;43:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2005.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe O, Ventorino V, Cavella S, Fagnano M, Brugno R. Prebiotic content of bread prepared with flour from immature wheat grain and selected dextran-producing lactic acid bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:3779–3785. doi: 10.1128/aem.00502-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovska-Avramenko N, Karklina D, Gedrovica I. Investigation of immature wheat grain chemical composition. Res Rural Dev. 2016;1:102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Praznik W, Schillinger H, Beck RHF. Changes in the molecular composition of maize starch during kernel development. Starch-Stärke. 1987;39:183–187. doi: 10.1002/star.19870390602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu SN, Park SZ, Ho CT. High performance liquid chromatographic determination of anthocyanin pigments in some varieties of black rice. J Food Drug Anal. 1998;6:729–736. [Google Scholar]

- Saa DT, Di Silvestro R, Dinelli G, Gianotti A. Effect of sourdough fermentation and baking process severity on dietary fibre and phenolic compounds of immature wheat flour bread. LWT. 2017;83:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.04.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, Xu F, Sun X, Bao J, Beta T. Phenolic acids, anthocyanins, and antioxidant capacity in rice (Oryza sativa L.) grains at four stages of development after flowering. Food Chem. 2014;143:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Juliano BO. Free sugars in relation to starch accumulation in developing rice grain. Plant Physiol. 1977;59:417–421. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.3.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waduge RN, Kalinga DN, Bertoft E, Seetharaman K. Molecular structure and organization of starch granules from developing wheat endosperm. Cereal Chem. 2014;91:578–586. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM-02-14-0020-R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanly W, Yaoqi T, Zhengjun X. Structural properties of the starches isolated from developing waxy rice seeds. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2018;37:1054–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Xu JG, Hu QP, Wang XD, Luo JY, Liu Y, Tian CR. Changes in the main nutrients, phytochemicals, and antioxidant activity in yellow corn grain during maturation. J Agri Food Chem. 2010;58:5751–5756. doi: 10.1021/jf100364k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Shin JA, Gan LJ, Zhu XM, Hong ST, Sung CK, Cho JW, Ku JH, Lee KT. Comparison of nutritional compounds in premature green and mature yellow whole wheat in Korea. Cereal Chem. 2012;89:284–289. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM-05-11-0068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yawadio R, Tanimori S, Morita N. Identification of phenolic compounds isolated from pigmented rices and their aldose reductase inhibitory activities. Food Chem. 2007;101:1616–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]