Abstract

The present study aimed at assessing the impact of addition of fumaric acid (0.5%), as an active agent, in a corn starch (2%) based edible coating, on the lipid quality and microbial shelf life of silver pomfret (Pampus argenteus) fish steaks stored at 4 °C. Treating fish steaks with FA resulted in a bacteriostatic effect leading to reduced counts of total mesophilic and psychrotrophic bacteria, H2S producing bacteria and Pseudomonas spp. The total mesophilic bacterial count of uncoated control sample exceeded the permissible limit of 7 log cfu g−1 on 6th day and had the lowest microbial shelf life. FA incorporation in the CS coating improved the microbial stability of fish steaks resulting in a shelf life of 15 days. The outcomes of the study suggest that CS based coating is beneficial in delaying lipid oxidation as displayed by the lower TBA and PV values while FA is an effective agent for further increasing the preservative action of CS coating by significantly inhibiting microbial growth as well as lipid quality deterioration, which could be exploited by the seafood industry as an active packaging component.

Keyword: Psychrotrophic bacterial count, Pampus argenteus, Oxygen barrier, Seafood

Introduction

The silver pomfret or white pomfret (Pampus argenteus) is one of the most important commercial fishes in India and also a highly preferred edible fish worldwide (Zhao et al. 2010). The estimated landing of silver pomfret in India for the year 2019 was 28,606 tonnes (CMFRI 2019). It is usually recognized as a premium export quality fish, because of its unique and excellent taste, white flesh and soft ‘buttery’ texture and are generally sold as butterfishes. This high valued fish is usually traded as fresh or in chilled/refrigerated and frozen forms. The fresh fishes have a very short shelf life due to deterioration in quality by lipid oxidation, enzyme activity and microbial spoilage and therefore commonly stored in chilled/refrigerated condition (Qiu et al. 2014). But, storing at refrigerated temperature also doesn’t sufficiently enhance the shelf life, which finally leads to quality loss and making the seafood unfit for consumption. The refrigerated silver pomfret is very high in demand among consumers, since they are close to fresh fish in quality. Hence, finding alternative methods for further lengthening the storage life of refrigerated fish is gaining popularity (Wu et al. 2016).

Recently, there is a growing attention on natural resources, which can be employed as edible coatings and films for enhancing the quality, safety and storage life of food. The thin layer of edible coatings can be made from polysaccharides, proteins and lipids or its amalgamations and offer several benefits including biodegradability, edibility, barrier properties and environmental friendliness. Furthermore, since the edible coatings can carry antimicrobial/antioxidant components and other food additives, they can act as food preservatives (Günlü et al. 2014). Edible coatings and films can thus offer extra protection and extend the shelf stability of refrigerated stored seafood. Starch, a natural renewable polysaccharide, is one of the most frequently used materials for edible coating/film making, owing to its abundance, biodegradability, low oxygen permeability, commercial availability, flexibility, low cost and relative ease in handling (Ortega-Toro et al. 2017). In particular, corn starch (CS) has been broadly studied in the food industry to be used as coating and for developing biodegradable plastics, because of its promising features like good film forming ability, highest global production, low cost and edibility (Song et al. 2018). Meanwhile, the ability of corn starch based edible coating to enhance the post-harvest storage life of food can be safely enriched by incorporation of active ingredients like antioxidant compounds and antimicrobial agents.

The initial freshness of fish is generally lost due to enzymatic and chemical reactions while the fish gets significantly spoiled due to microbial action and hence it decides the product shelf life (Gram and Huss 1996). Many organic acids, which has long been used for food preservation, display both bactericidal and bacteriostatic properties (Tango et al. 2014) and can act as excellent antimicrobial agents. Fumaric acid (C4H4O4), a four-carbon unsaturated dicarboxylic acid, is an important natural organic acid, which is popular as a food additive, since 1946. This low cost and practically non-toxic food additive (Santini et al. 2012) have excellent bactericidal activity (Comes and Beelman 2002) and antioxidant property. Fumaric acid (FA) appears as white crystalline powder and is found naturally in some plants. In addition to that, human skin also produces FA upon exposure to sunlight, which gives consumers a feeling that it’s a safe food additive. FA find its use as additive in several foods like tortillas, fruit juices, soft drinks, dairy based products, some kinds of breads, wine, desserts and jellies. Processed and packaged food are also added with FA including frozen seafood, sausage casings, canned and smoked meat. The E number of this fruit-like/sour tasting additive is E297. FA has been permitted by Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) as a food additive, which also has got the status of Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) by USFDA. Previously, FA was used as an antimicrobial agent against pathogenic microorganisms in apple cider, broccoli sprouts and lettuce (Chikthimmah et al. 2003; Kondo et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2009). Nevertheless, there is lack of information about the antimicrobial activity as well as antioxidant capacity of FA, when used as an active additive in the edible coatings applied in the real food matrices like fish. Hence, the present study intended at assessing the preservative action of corn starch (CS) based bio-active edible coating containing FA on silver pomfret (Pampus argenteus) fish steaks by evaluating its microbiological, bio-chemical and organoleptic quality changes during refrigerated storage at 4 °C.

Materials and methods

Materials

Corn starch and fumaric acid were procured from Merck (India). The media used for microbiological quality analysis of silver pomfret fish steaks during refrigerated storage were bought from HiMedia (Mumbai, India). All the other reagents employed in the present study were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (India) and Merck (India).

Preparation of coating solutions

Three different coating solutions (CS, FA and CSFA) were prepared for the study. The first one was a corn starch based edible coating solution (CS) and the second one was fumaric acid (FA) solution. To prepare CS, 20 g corn starch (2% w/v) was dissolved in 1000 ml of sterilized distilled water and the solution was heated in a water bath at 80 °C for 15 min with constant agitation. Later, the solution was sterilized using an autoclave and kept at room temperature for cooling. A dipping solution of fumaric acid (0.5% w/v) without corn starch was also prepared (FA). Then, for preparing the third coating solution, which was corn starch based bio-active edible coating containing fumaric acid (CSFA), 5 g of FA was added to 1000 ml starch solution to get a final concentration of 0.5% and homogenized by means of a T18 digital ULTRA TURRAX® homogenizer (IKA®, Karnataka, India. Finally, all the prepared solutions were kept at 4 °C till use.

Preparation, coating and storage of silver pomfret fish steaks

The fresh silver pomfret (Pampus argenteus), weighing 550 ± 30 g with an average length of 24 ± 3 cm, was bought from Jaleshwar fish landing centre (Veraval, Gujarat, India) and carried to fish processing laboratory of ICAR-CIFT, Veraval, Research Centre (Gujarat, India) in insulated fish boxes with sufficient ice. The fishes were beheaded, gutted and washed using chilled potable water before cutting into steaks of 2.5 cm length with an average weight of 120 ± 10 g. Then, the fish steaks were again washed in chilled potable water and divided into four sets. One set was uncoated control (CL), second set was coated with 2% corn starch (CS), the third set was dip treated with 0.5% fumaric acid (FA) and the fourth set was coated with 2% corn starch containing 0.5% fumaric acid (CSFA).

The fish steaks were dipped in the CS, FA and CSFA solutions (Fish and solution in 1:2 ratio) for 10 min in chilled condition. The control samples were immersed in distilled water. The dipped fish steaks were then allowed to air dry for 5 min on a pre-sterilized container to fix the coating. Further, all the fish steaks (CL, CS, FA & CSFA) were individually packed in a pouch of ethylene–vinyl alcohol (EVOH) bought from Sealed Air (India) Pvt. Ltd. (Bangalore, India). The multilayer (nylon, EVOH and polyethylene) film pouches with 15 × 20 cm size had a thickness of 138–140 µ and oxygen transmission rate of 3.86 cc m−2 24 h−1 at 1 atmospheric pressure. The fish samples were then heat sealed and stored at 4 ± 0.2 °C and evaluated periodically for microbiological (total viable count, psychrotrophic count, Pseudomonas spp. and H2S producing bacteria), bio-chemical (TVB-N, TBA, PV and pH) and sensory quality.

Microbiological analysis

Sample preparation

The fish steak sample was taken using sterile pincers, scalpel and scissors. 10 g of fish steak sample was put under aseptic conditions to a stomacher bag (Seward Stomacher circulator bag, Model No. 400, England). It was homogenized for 1 min with the help of a lab stomacher blender (Seward Stomacher 400 Circulator, England) at 230 rpm after adding 90 ml of sterile normal saline (0.85%). Further, using 0.85% normal saline, suitable successive decimal dilutions were made for microbiological examination.

Total mesophilic and psychrotrophic counts

The total mesophilic and psychrotrophic bacterial counts were determined by spread plate method after preparing serial decimal dilutions of the homogenized fish steak sample. Plate count agar (PCA, HiMedia, HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India) was used for inoculating the sample. The plates were kept for incubation at 37 °C for 48 h for mesophilic bacterial counts (Townley and Lanier 1981) and at 7 °C for 7 days for total psychrotrophic count (Hitching et al. 1995). The results are expressed as log cfu/g.

Pseudomonas spp.

Pseudomonas spp. was counted employing Cetrimide Fucidin Cephaloridine agar (CFC, Oxoid code CM 559 with SR 103 (0.4 ml)) (Mead and Adams 1977).

H2S producing bacteria

Peptone Iron agar (PIA) (code 289100, BBL Difco) with added 1% salt was used for counting hydrogen sulphide (H2S) producers including Shewanella putrefaciens (Gram et al. 1987).

Bio-chemical analysis

Determination of pH

5 g of fish steak sample was homogenized using 25 ml of distilled water and the pH value was noted (Remya et al. 2017) using a glass electrode digital pH meter (Cyberscan 510, Eutech Instruments, Singapore).

Determination of total volatile base nitrogen (TVB-N)

Total volatile bases in the fish steak samples were analyzed as total volatile base nitrogen (TVB-N) by Conway’s micro diffusion method (Conway 1962) using TCA extract and the results are expressed as mg N2 100 g–1 of the sample.

Determination of peroxide value (PV)

Peroxide value (PV) in the fish steak samples was analyzed by iodimetric titration (AOCS 1989) and displayed as milliequivalent of O2 kg−1 fat.

Determination of thiobarbituric acid (TBA) value

TBA value was checked by distillation method and shown as mg malonaldehyde (MDA) kg−1 of fish sample (Tarladgis et al. 1960).

Sensory analysis

Analysis of the sensory quality of the fish steak samples during refrigerated storage was done by a team of 10 researchers trained in the fish processing laboratory using a 9-point hedonic scale (Meilgaard et al. 1999), in which 9 and 1 represented extremely desirable and extremely undesirable, respectively. Before serving, the fish steaks were boiled in 1.5% salt solution for 10 min and water was offered to the panelists for restoring the taste after every sample analysis. The team members judged organoleptic properties such as general appearance, colour, odour, flavour, texture and taste of fish steak and assigned the score for overall acceptability. The shelf life criteria were decided in such a way that rejection would happen, when the sensory score reach ≤ 5 for overall acceptability of fish steak samples.

Statistical analysis

SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Inc., Chicago, USA, version 17) software was used for statistical analysis of the obtained results. All the measurements were done in triplicate. For comparing the mean values of results, one-way ANOVA was employed and finally, the results were stated as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) was used for finding out significant difference between the treatments at p < 0.01 for microbiological quality attributes and at p < 0.05 for the rest of the parameters.

Results and discussion

Microbiological quality

Total mesophilic and psychrotrophic bacterial counts

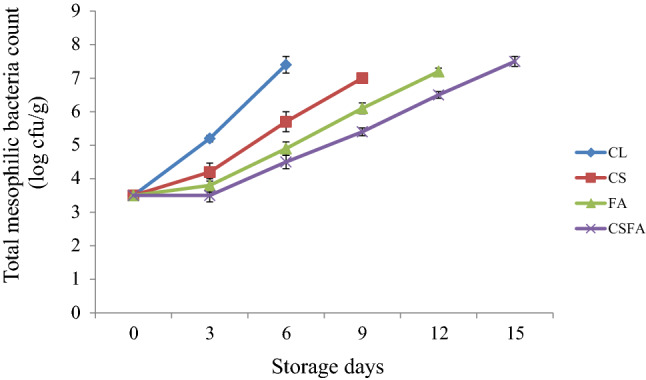

The total mesophilic and psychrotrophic counts assume significance, since it gives an indication about the microbial spoilage in food. The initial total mesophilic and psychrotrophic counts of the silver pomfret fish steak were 3.5 and 3 log cfu g−1, respectively, which indicated the good quality of fish sample used. Variations in the counts of total mesophilic and psychrotrophic bacteria in silver pomfret fish steaks during refrigerated storage is shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Compared to coated samples, the uncoated control (CL) had a significantly (p < 0.01) higher increase in the count of total mesophilic and psychrotrophic bacteria over the period of storage. The results also exhibited that the fish steaks coated with CS containing FA had the lowest counts for both total mesophilic bacteria and psychrotrophic bacteria, which could be attributed to the combined synergistic action of antimicrobial FA and CS coating. Similarly, high molecular weight chitosan coating reduced mesophilic bacterial count in refrigerated channel catfish fillets due to its antimicrobial efficiency and oxygen barrier effect in food (Karsli et al. 2021). Previously, many researchers have studied the bactericidal and bacteriostatic efficiency of organic acids (Salmond et al. 1984; Cherrington et al. 1991; Smyth et al. 2018; Popelka et al. 2020). Other than lowering the pH of the food, the lipid membrane of bacteria is penetrated by FA molecules causing destabilization of the pH in the cytoplasm (Smyth et al. 2018). Acidification of the cell cytoplasm of microbes, by releasing excess protons, subsequent to dissociation of the acid, is generally regarded as the overall mechanism of growth inhibition of microorganisms by organic acids. In addition to general inhibition, a specific inhibition by undissociated acid due to disruption of an unidentified metabolic function has also been reported (Salmond et al. 1984). It was recorded that FA causes disruption of membrane proteins and structure leading to interruption of ATP synthesis in the membrane.

Fig. 1.

Changes in the total mesophilic bacteria count* of silver pomfret steaks during refrigerated storage. ∗mean ± SD, n = 3, p < 0.01, CL, Uncoated control; CS, Coated with corn starch; FA, Treated with fumaric acid; CSFA, Coated with CS added with FA

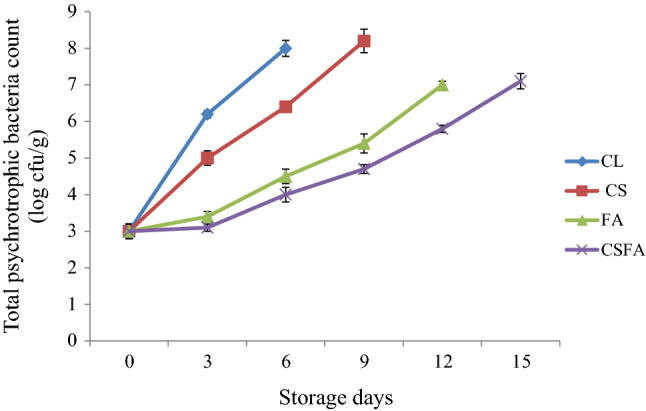

Fig. 2.

Changes in the total psychrotrophic bacteria count* of silver pomfret steaks during refrigerated storage. ∗mean ± SD, n = 3, p < 0.01, CL, Uncoated control; CS, Coated with corn starch; FA, Treated with fumaric acid; CSFA, Coated with CS added with FA

The total mesophilic bacteria count or the aerobic plate count of CSFA displayed a lag phase of 3 days seemingly indicating bacteria acclimatizing to the changed new surroundings before multiplication, which could be chiefly due to the inhibitory effect of FA on microbial growth. The corn starch based edible coating with oxygen barrier properties as well as storage at refrigerated temperature also seemed to have facilitated the inhibition of growth of aerobic spoilage organisms. There was no lag phase detected for CS and FA samples. However, both the CS coated and FA treated samples had significantly (p ≤ 0.01) lower counts of aerobic mesophilic bacteria, compared to control. The upper acceptable limit of 7 log cfu g−1, set by International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods (ICMSF, 1986) for total mesophilic count in fresh fishes, was exceeded by CL, CS, FA and CSFA samples on 6th, 9th, 12th and 15th days of storage, respectively, indicating the microbial shelf life, which matched with the sensory refusal of samples by judging panel. Based on the total mesophilic count, the shelf life of control sample is estimated to be 6 days. The CSFA fish steaks were microbiologically agreeable till the end of storage of 15 days, which thus prolonged the shelf stability of silver pomfret fish steak by 9 days, compared to uncoated control fish steaks. In one of the previous studies, potato starch-based coating treatment added with thyme essential oil decreased the aerobic plate count by 4 log CFU/g in shrimps, compared to the uncoated samples (Alotaibi and Tahergorabi 2018). Grape seed extract (GSE) showed inhibiting effect on bacterial growth in snakehead fillet during chilled storage due to the significant antibacterial action of GSE and had lower total viable counts than control (Li et al. 2020). García-Soto et al. (2013) observed that treatment with two natural organic acids (citric acid, CA and lactic acid, LA) in the form of flake icing systems, led to a significant growth inhibition of aerobic mesophiles in European hake (Merluccius merluccius) and García-Soto et al. (2014a) reported that presence of CA and LA in the icing medium protected chilled megrim (Lepidorhombus whiffiagonis) from aerobic mesophiles. A group of previous researchers (Kim et al. 2009) noted that there was 1.60 log CFU/g reduction in the count of aerobic microorganisms in broccoli sprouts by fumaric acid treatment. Another study (Comes and Beelman 2002) conveyed a decrease of 5 log in the count of Escherichia coli (O157:H7), when apple cider was treated with 0.15% (wt/vol) FA along with 0.05% (wt/vol) sodium benzoate.

In the beginning of the experiment, count of psychrotrophs was recorded less than mesophiles. It was reported that the gram-negative psychrotrophs are mainly accountable for spoilage and consequent quality deterioration of fresh fish stored at low temperature under air (Gram and Huss 1996; Sallam 2007). As the refrigerated storage of the fish steaks progressed, psychrotrophs dominated the bacterial flora in CL, due to rapid multiplication at low temperatures than mesophiles, confirming that bacterial flora in uncoated control sample included mostly psychrotrophs (Duan et al. 2010; Remya et al. 2017). It was noted that FA treatment and CSFA coating could significantly (p ≤ 0.01) inhibit the growth of psychrotrophic fish spoilers as displayed by lower counts than mesophiles all over the storage period. It was also observed that there were notable differences in the counts of total psychrotrophic bacteria of both FA and CSFA in comparison to samples coated with CS alone. At the end of the sensory shelf life, psychrotrophic counts of CL, CS, FA and CSFA fish steaks were 8, 8.2, 7 and 7.1 log cfu g−1, respectively. Similarly, there was a record that fumaric acid treatment significantly reduced the count of psychrotrophs in vacuum packaged ground beef patties during storage at 4 °C (Podolak et al. 1996). Also, significant (p < 0.05) differences were noted in the count of psychrotrophs among organic acid treated (citric and lactic acid) and control megrim fish samples after longer chilled storage indicating the protective action of organic acids against microbes (García-Soto et al. 2014a).

Count of Pseudomonas spp. and H2S producers

The psychrotrophic gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria, Pseudomonas spp. and H2S producers including Shewanella putrefaciens, are described as specific spoilage organisms (SSOs) in aerobically stored fish at low temperature (Gram and Huss 1996). Since the microbial flora of spoiled fish caught from all waters are almost dominant by these species, counts of these two act as microbial spoilage indicators of fishes stored under refrigeration. There are previous reports about reduction of counts of major spoilage microorganisms in addition to aerobic bacteria by the use of salts of organic acids (Sallam 2007; Mohan et al. 2010; Yesudhason et al. 2014). In the present study, both the species showed a similar evolution in the uncoated control (CL) sample during refrigerated storage. The initial count of aerobic Pseudomonas spp. in silver pomfret fish steak was 2.2 log cfu g−1, which was on the rise in all the samples along with storage time (Fig. 3). Still, the count of Pseudomonas spp. raised swiftly in control sample and reached a value of 7.5 log cfu g−1 on 6th day making it 5.3 log higher than the initial count. But, rate of increase in the count of Pseudomonas spp. was slow in CS, FA and CSFA samples, which had the final counts of 6.1 log cfu g−1, 5.7 log cfu g−1 and 5 log cfu g−1, respectively. The results indicated that corn starch based edible coating significantly (p ≤ 0.01) controlled the growth of aerobic bacteria, which is also revealed by lower count of Pseudomonas spp. than H2S producing bacteria during storage. On the day of sensory rejection of CL, i.e., on 6th day, there was 2.7 log cfu g−1 difference in the count of Pseudomonas spp. between CS and CL, proving the fact that edible coating can act as oxygen barrier leading to growth inhibition of aerobic bacteria. The final counts of CS, FA and CSFA samples were 1.4–2.5 log cfu g−1 lower than the uncoated control sample. There were also significant (p ≤ 0.01) differences in the count of CSFA compared to CS and FA, possibly due to the additive effect of CS based edible coting with high O2 barrier efficiency and antibacterial FA. Previously, there was an observation that sodium acetate coupled with modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) was effective in inhibiting the growth of Pseudomonas spp. in seer fish stored at low temperature (Yesudhason et al. 2014).

Fig. 3.

Changes in the Pseudomonas spp. count* of silver pomfret steaks during refrigerated storage. ∗mean ± SD, n = 3, p < 0.01, CL: Uncoated control; CS, Coated with corn starch; FA, Treated with fumaric acid; CSFA, Coated with CS added with FA

H2S producers including Shewanella putrefaciens has been stated as specific spoilage bacteria in aerobically stored fish under refrigeration (Koutsoumanis and Nychas 1999). In the current experiment, the H2S producing bacteria were confirmed as Shewanella putrefaciens, which produces volatile sulfides including H2S by degrading sulfur containing amino acids and was one of the major group of microbes in CL and CS samples. The ability of S. putrefaciens to reduce trimethylamine-N-oxide (TAMO) to trimethylamine (TMA) leading to strong and fishy off-odour production and its psychrotrophic nature are making it significant in the microbial spoilage of marine fish stored at low temperature (Vogel et al. 2005; Na et al. 2018). The count of H2S producing bacteria was 2.1 log cfu g−1 in the starting and its changes over the period of storage is displayed in Fig. 4. The count increased progressively with storage time for CL and CS coated samples while FA and CSFA samples displayed a significantly (p ≤ 0.01) slow growth in the count of H2S producers, which reveals the ability of antibacterial fumaric acid in inhibiting the growth of psychrotrophic H2S producing bacteria. On 6th day, the count of CL reached 7.7 log cfu g−1, which was 7.2 log cfu g−1 for CS on the day of sensory rejection. The counts of FA and CSFA fish steaks on 12th and 15th days of refrigerated storage were 6.2 log cfu g−1 and 5.3 log cfu g−1, respectively. The results conveyed that there was substantial delay in the growth of H2S producers in fish steak samples coated with CSFA, suggesting that, among the treatments, the active corn starch coating containing fumaric acid was the most efficient in controlling the growth of H2S producers. This can be credited to the CS based edible coating combined with antimicrobial FA. Fumaric acid has proven bactericidal action, which decreases the intracellular pH by diffusing through the cell membrane and acid pH in the internal cell and also impairs or alters the functions of enzymes, structural proteins and DNA (Park and Ha 2019). The undissociated FA molecules and the resulted low pH, which suppresses the growth of bacteria, could be the reason for reduced count of H2S producers. Similarly, there was a report (Mohan et al. 2010) on H2S producers as the chief micro-flora of the untreated seer fish (Scomberomorus commerson) steaks aerobically stored in ice, in which sodium salt of acetic acid along with O2 scavenger notably inhibited growth of H2S producers. On the contrary, Smyth et al. (2018) reported that organic acid treatments (citric acid and lactic acid @ 5% (w/v)) did not significantly (p > 0.05) affect the Pseudomonas spp. and H2S producing bacteria counts in cod (Gadus morhua) fillets aerobically stored at 2 °C.

Fig. 4.

Changes in the count of H2S producers* of silver pomfret steaks during refrigerated storage. ∗mean ± SD, n = 3, p < 0.01, CL, Uncoated control; CS, Coated with corn starch; FA, Treated with fumaric acid; CSFA: Coated with CS added with FA

Sensory quality

Analysis of sensory quality is very important for evaluating the freshness of fish, since it gives a direct measurement of spoilage to the consumers. In the current study, the original sensory score for overall acceptability was 9.1 for the silver pomfret fish steaks on 0th day (Fig. 5). The fish was very fresh and had sea weedy odour, shiny appearance and firm texture, which gradually altered with the storage time and matched with the increase in the total mesophilic count of the fish steak samples. During storage, there was a reduction in the overall sensory score for all the samples, but the quality deterioration was significantly (p ≤ 0.05) lower in coated samples. There were significant (p ≤ 0.05) differences in the sensory score of CS and FA dip treated samples. None of the members in the judging panel noticed acidic or sour taste and flavour in the FA treated samples. FA and CSFA fish steaks showed significant (p ≤ 0.05) variation in the organoleptic properties only towards the end of the storage study and CSFA samples had the highest sensory score throughout the storage period, owing to the combined action of FA and corn starch coating. The preservative ability of FA with antimicrobial and antioxidant efficiency and the barrier properties of corn starch edible coating might have led to superior sensory score for CSFA fish steak samples. Compared to the uncoated control sample, which was acceptable for human consumption only for 6 days, the coated samples had extended sensory shelf life. The upper acceptable value of ≤ 5 for overall sensory score was crossed on 6th, 9th, 12th and 15th days of refrigerated storage for CL, CS, FA and CSFA samples, respectively, indicating the sensory shelf life. Thus, the treatments with CS, FA and CSFA increased the shelf life of fish steaks by 3, 6 and 9 days, respectively, revealing the efficiency of corn starch edible coating and FA for preventing or reducing quality loss. Likewise, chitosan-sodium alginate-nisin coated shrimp had better sensory score during chilled storage because of the synergetic functional properties including antioxidant, antimicrobial and oxygen barrier properties of the coating components (Cen et al. 2021). Due to larger reductions in the microbial growth in ground beef patties, Podolak et al. 1996 stated that fumaric acid could be an excellent antimicrobial preservative for meat during storage. Similarly, European hake stored in a novel flake icing system containing citric and lactic acid had better sensory attributes compared to fish stored in traditional ice (García-Soto et al. 2013). For silver pomfret (Pampus argenteus), an enhancement of 3–6 days in the shelf life, due to conjugate chitosan gallate coating during refrigerated storage, was reported in an earlier study (Wu et al. 2016).

Fig. 5.

Changes in the overall acceptability score* of silver pomfret steaks during refrigerated storage. ∗mean ± SD, n = 3, p < 0.05, CL, Uncoated control; CS, Coated with corn starch; FA, Treated with fumaric acid; CSFA, Coated with CS added with FA

Bio-chemical quality

pH

Since pH is affected by changes in the concentrations of free hydrogen and hydroxyl ions due to the alterations in the food redox equilibrium by microbial or enzymic activity, monitoring pH has been considered as one of the valuable methods for evaluating the quality of fishes during post-mortem storage. The pH value of the fresh silver pomfret steak (CL) was equal to 5.49 ± 0.04 (Table 1, which showed a decrease initially and then displayed an increase with the storage period. pH values of CS, FA and CSFA in the beginning of the storage study were 5.47 ± 0.01, 5.34 ± 0.02 and 5.40 ± 0.01, respectively. Post mortem glycolysis leads to buildup of lactic acid resulting in an initial drop in the pH of the fish muscle. Also, FA treatment caused a significant (p ≤ 0.05) reduction in the pH of FA and CSFA fish steaks, compared to CL and CS. Earlier studies also reported a similar decrease in pH. There was pH drop in salmon slices treated with organic acids (Sallam 2007) and in shrimps coated with chitosan containing acetic acid because of the acidity of the organic acid in the coating (Na et al. 2018). Towards the end of storage period, the pH values tend to increase for the control as well as treated samples. A previous experiment revealed that the control hake fish samples preserved by conventional ice had a steady increase in pH with storage time (p < 0.05), corresponding to the increased microbial activity, compared to fish samples stored in ice containing natural organic acids (García-Soto et al. 2013). In the present work, there was a rapid rise in the pH in uncoated control sample attaining a value of 7.15 at the end of sensory shelf life. The further increase in the values of pH during post-harvest storage of fish is reported to be due to the surge in the volatile bases (e.g., ammonia and trimethylamine) formed by either microbial or endogenous enzymes (López-Caballero et al. 2007). Hence, throughout the storage, values of pH for the coated fish steak samples were significantly (p ≤ 0.05) lower than that of the control, indicating delayed bacterial activity and spoilage. Reduction in pH and the existence of its dissociated form are reportedly responsible for the antimicrobial activity of fumaric acid (Comes and Beelman 2002). Also, during storage, pH values of FA and CSFA samples were lesser than the samples coated with corn starch alone, possibly due to the acidic nature of FA used for treatment in addition to its antimicrobial effect.

Table 1.

Changes in the pH, Total Volatile Basic Nitrogen (TVB-N), Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) value and Peroxide value (PV) of silver pomfret fish steaks during refrigerated storage

| Attributes | Treatments | Storage days | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 | ||

| pH | CL | 5.49 ± 0.04Dab | 5.45 ± 0.04 Da | 7.15 ± 0.03Dc | NA | NA | NA |

| CS | 5.47 ± 0.01CDb | 5.40 ± 0.01Ca | 6.30 ± 0.04Cc | 7.00 ± 0.01Cd | NA | NA | |

| FA | 5.34 ± 0.02Ab | 5.29 ± 0.01Aa | 5.35 ± 0.04Abc | 6.15 ± 0.01Bd | 6.40 ± 0.05e | NA | |

| CSFA | 5.40 ± 0.01Bbc | 5.39 ± 0.05Ba | 5.40 ± 0.02Bab | 6.00 ± 0.02Ad | 6.32 ± 0.03e | 6.54 ± 0.02f | |

| TVB-N (mg N2 100 g−1) | CL | 8.25 ± 1.2Aa | 25.7 ± 1.0Db | 36.4 ± 2.0Dc | NA | NA | NA |

| CS | 8.25 ± 1.2Aa | 19.0 ± 3.1Cb | 28.2 ± 2.2Cc | 34.2 ± 3.0Cd | NA | NA | |

| FA | 8.25 ± 1.2Aa | 14.1 ± 1.2ABb | 22.7 ± 1.0Bc | 28.4 ± 2.5ABd | 33.6 ± 2.3e | NA | |

| CSFA | 8.25 ± 1.2Aa | 12.7 ± 2.5Ab | 18.3 ± 0.9Ac | 24.6 ± 2.1Ad | 27.5 ± 1.5de | 32.1 ± 3.3f | |

| TBA (mg Malonaldehyde kg−1) | CL | 0.24 ± 0.02Aa | 1.15 ± 0.12Db | 3.26 ± 0.22Dc | NA | NA | NA |

| CS | 0.24 ± 0.02Aa | 0.73 ± 0.03Cb | 1.24 ± 0.15Cc | 2.11 ± 0.06Cd | NA | NA | |

| FA | 0.24 ± 0.02Aa | 0.51 ± 0.01Bb | 0.82 ± 0.05Bc | 1.45 ± 0.20Bd | 2.05 ± 0.04e | NA | |

| CSFA | 0.24 ± 0.02Aa | 0.35 ± 0.04Ab | 0.56 ± 0.06Ac | 0.95 ± 0.13Ad | 1.54 ± 0.05e | 2.32 ± 0.26f | |

| PV (meq of O2 kg−1) | CL | 0.95 ± 0.10Aa | 4.45 ± 0.20Dc | 3.95 ± 0.31Db | NA | NA | NA |

| CS | 0.95 ± 0.10Aa | 1.70 ± 0.25BCb | 3.77 ± 0.07Cd | 3.55 ± 0.14Cc | NA | NA | |

| FA | 0.95 ± 0.10Aa | 1.55 ± 0.11Bb | 2.16 ± 0.16ABc | 3.36 ± 0.06Be | 3.06 ± 0.06d | NA | |

| CSFA | 0.95 ± 0.10Aa | 1.34 ± 0.05Ab | 1.83 ± 0.22Ac | 2.65 ± 0.10Ad | 3.04 ± 0.09f | 2.98 ± 0.14e | |

A–DMean ± SD in the column for each attribute with different superscripts are significantly different between treatments (p < 0.05)

a–eMean ± SD in the row with different superscripts are significantly different between storage period (p < 0.05)

CL, Uncoated control; CS, Corn starch coating; FA, Fumaric acid treatment; CSFA, Corn starch coating added with fumaric acid

TVB-N

Total volatile base nitrogen (TVB-N) is one of the best characterized bio-chemical indicators of seafood spoilage, which comprises ammonia, dimethylamine (DMA), trimethylamine nitrogen (TMA-N) and other volatile basic nitrogenous compounds. The results showed that TVB-N value in refrigerated stored silver pomfret fish steak samples increased with the rise in total mesophilic bacterial count and reduction in sensory score. Volatile amines are formed in fish partly due to endogenous enzyme action but majorly by microbial growth (García-Soto et al. 2014b). The initial TVB-N value of silver pomfret fish steak was 8.25 mg N2 100 g−1, which upon refrigerated storage gradually increased to 36.4 ± 2.6 mg N2 100 g−1 in uncoated control sample on 6th day (Table 1). TVB-N value beyond 30–35 mg N2 100 g−1 in fish flesh indicates that fish is spoiled and not suitable for human consumption. The values of TVB-N of all the four samples exceeded the above limit of acceptability on the day of sensory rejection. The high bacterial counts leading to increased breakdown of compounds like trimethylamine oxide (TMAO), peptides, amino acids, etc. (Gram and Huss 1996), would have attributed to a significantly higher increase in the basic nitrogen fraction for CL samples compared to coated fish steaks. Low oxygen permeability, leading to inhibition of growth of aerobic spoilage microorganisms, might have caused a decrease in the level of TVB-N in CS coated samples, in comparison to control. Throughout the storage, FA and CSFA fish steak samples maintained a significantly (p < 0.05) lower TVB-N value than that of CL and CS steaks. Such findings indicated prohibition of bacterial multiplication by FA and consequent delay in the formation of volatile basic compounds due to metabolic action of seafood spoilage bacteria. In a previous study in chilled hake (Merluccius merluccius) fish, combination of organic acids (ascorbic acid, citric acid and lactic acid) in the icing system reduced the production of amines by microbes due to their preservative action. The excess hydrogen ions in the cytoplasm owing to dissociation of organic acids lead to a reduction in pH to such levels, which are unfavourable for bacterial growth (Rey et al. 2012). Cen et al. (2021) observed that chitosan-sodium alginate-nisin coated Penaeus vannamei shrimp had the lowest TVB-N values during cold storage because of the preservative action of active ingredients in the coating leading to alteration of permeability of cell membrane, prevention of reproduction and metabolism of microbes.

PV and TBA

After microbial growth, lipid oxidation is the major reason for fish spoilage that limits the shelf life of fish species. This is important especially in fatty and medium fatty fishes like silver pomfret with high fat content, which creates the problem of rancidity leading to formation of toxic oxidation products, unpleasant flavour, loss of nutritional quality and shelf stability making the fish unfit for human consumption. Both peroxide value (PV) and thiobarbituric acid (TBA) value are widely used as indicators to measure the degree of lipid oxidation during fish storage.

The peroxide value (PV) is determined for measuring the degree of the initial stage of the oxidative changes in fish. The primary products of oxidation of lipid are hydroperoxides, which are odourless. Nonetheless, its deterioration generates an extensive range of compunds, which causes rancid flavour in rotten food. The results show that PV was 0.95 meq of O2 kg−1 for fresh silver pomfret fish steaks on day 0 (Table 1), which increased during the early period of refrigerated storage in all the samples with a significantly (p < 0.05) lower increase in coated samples. For uncoated CL sample, the maximum value for PV was reached on 3rd day of storage followed by a decrease on day 6 of storage. There were significant (p ≤ 0.05) differences in PV in coated fish steak samples on 3rd day of storage compared to control. PV of CS, FA and CSFA displayed a steady upward trend during storage and the highest PV was shown on 6th, 9th and 12th days of storage, respectively. Then, there was a decrease in PV and at the end of 15 days of refrigerated storage, PV of CSFA was 2.98 meq of O2 kg−1. The rise in PV in the early stages of storage attribute to forming of hydroperoxides higher than the rate of breakdown. Its reduction after attaining the maximum value was resulted from the lesser accessibility of substrate and instability of peroxide molecules resulting in production of hydroperoxides at the rate of breakdown (Pereira De Abreu et al. 2011). The results of the current experiment showed that the coatings were highly efficient in hindering the generation of PV in fish steaks during refrigerated storage. The high antioxidant efficiency of fumaric acid might have caused reduction in PV in FA. It was previously reported that combined treatment of acetic acid and ascorbic acid controlled the formation of primary lipid oxidation products in silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) fillets stored at 4 °C (Monirul et al. 2019). Organic acids are strong natural preservatives and hence can delay or inhibit lipid oxidation in food. A study on Indian mackerel (Rastrelliger kanagurta) stored in ice containing Garcinia spp. extract indicated substantial inhibition of peroxide formation because of the presence of organic acids in the extract (Apang et al. 2020). The highest resistance of CSFA to lipid oxidation can be inferred from the inferior oxygen permeability of the CS edible coating and antioxidant activity of FA, which might have led to lower PV in CSFA fish steak samples. There was a former detailing that the principle behind the antioxidant action of any compound including organic acids is either inhibition of the generation of reactive species or direct scavenging of free radicals (Pereira et al. 2009; Hunyadi 2019).

TBA (Thiobarbituric Acid) value indicates the extent of second stage of lipid oxidation, where aldehydes and ketones are produced from peroxides. The initial TBA value of silver pomfret steaks was 0.24 mg malonaldehyde kg−1. Though there was an increase in the TBA values of all the fish steak samples during storage, there was a significant (p < 0.05) difference in the TBA values among the four sets of samples. In some previous studies, the icing system containing citric acid and lactic acid hadn’t any substantial (p > 0.05) influence on the development of primary and secondary oxidation compounds in lean fishes like hake and megrim (García-Soto et al. 2013, 2014a). In the present study, the reduced TBA values in CS samples may be credited to the development of an O2 resistant layer by corn starch edible coating on fish surface. Fumaric acid had a significant (p < 0.05) influence in delaying lipid oxidation as revealed by the lower TBA values in FA treated fish steak samples. It was reported that fumaric acid, when used as additive in small quantity, gives a sour taste to foods or acts as acidulant or antioxidant or food preservative extending the shelf life of food longer than usual (Papadopoulos et al. 2001; Chun and Song 2014). Similar to this, incorporation of encapsulated citric acid minimized secondary oxidation values in ready-to-eat sea bass fish patties during storage at 4 °C in vacuum skin packaging (Bou et al. 2017). An earlier experiment for evaluating the antioxidant efficiency of organic acids, which are commonly using as food additives, by photo-storage chemiluminescence recorded that adipic acid, malic acid, and fumaric acid displayed high antioxidant activity leaving behind tartaric acid, ascorbic acid and citric acid (Papadopoulos et al. 2001). Addition of FA improved the antioxidant action of CS edible coating. The collective protective effects of both CS and FA might have resulted in lowest TBA values in CSFA during the entire storage period. The fishes typically produce an offensive odour, when TBA value reaches 1–2 mg malonaldehyde kg−1 and is generally viewed as the limit for consumability. The TBA concentration crossed the upper acceptable limit of 2 mg malonaldehyde kg−1 on 6th and 9th days in control (CL) and corn starch coated fish samples (CS), respectively. At the end of 12 and 15 days of storage, the TBA values of FA and CSFA were 2.05 and 2.32 mg malonaldehyde kg−1, respectively. The results of the current work proposed that lipid oxidation in refrigerated stored silver pomfret steaks can be minimized by the use of edible coatings with good barrier properties and incorporated with safe antioxidants like organic acids.

Conclusion

Silver pomfret is an important marine fish traded in the world, commanding high unit value in the export market, which makes its preservation and shelf-life extension at low temperature extremely important. In the present study, data from the microbiological quality analysis of refrigerated stored silver pomfret fish steaks showed that both FA and CSFA coating significantly (p ≤ 0.01) inhibited the growth of microbes compared to control, indicating the superior bacteriostatic efficiency of fumaric acid. CS edible coating with its ability to form an oxygen resistant layer on fish surface and FA with antioxidant capacity were proved to be excellent protectors against lipid oxidation in silver pomfret fish steaks without negatively impacting its organoleptic properties. The overall results of the present experiment suggested that CS edible coating containing fumaric acid could be a perfect selection for fish preservation and storage life extension at low temperature with scope for many applications in the seafood industry including active packaging.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Director, Indian Council of Agricultural Research-Central Institute of Fisheries Technology, Cochin, India for providing facilities to carry out this work. The authors also declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- CL

Control

- FA

Fumaric acid

- CS

Corn starch

- CSFA

Corn starch-based bio-active edible coating containing fumaric acid

Author contributions

SR & GKS conceived the idea, SR & EP carried out the work, SR & SKR wrote the manuscript, COM & TCJ edited the manuscript and CNR supervised the work.

Availability of data and material

Almost all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. If anything is missing, datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alotaibi S, Tahergorabi R. Development of a sweet potato starch-based coating and its effect on quality attributes of shrimp during refrigerated storage. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2018;88:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOCS (American Oil Chemists' Society) (1989) Official methods and recommended practices of American Oil Chemists Society, 5th edn. AOCS, Champaign, USA

- Apang T, Xavier KAM, Lekshmi M, et al. Garcinia spp. extract incorporated icing medium as a natural preservative for shelf life enhancement of chilled Indian mackerel (Rastrelliger kanagurta) LWT. 2020;133:110086. doi: 10.1016/J.LWT.2020.110086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bou R, Claret A, Stamatakis A, et al. Quality changes and shelf-life extension of ready-to-eat fish patties by adding encapsulated citric acid. J Sci Food Agric. 2017;97:5352–5360. doi: 10.1002/JSFA.8424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cen S, Fang Q, Tong L, et al. Effects of chitosan-sodium alginate-nisin preservatives on the quality and spoilage microbiota of Penaeus vannamei shrimp during cold storage. Int J Food Microbiol. 2021;349:109227. doi: 10.1016/J.IJFOODMICRO.2021.109227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrington CA, Hinton M, Mead GC, Chopra I. Organic acids: chemistry, antibacterial activity and practical applications. Adv Microb Physiol. 1991;32:87–108. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikthimmah N, LaBorde LF, Beelman RB. Critical factors affecting the destruction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in apple cider treated with fumaric acid and sodium benzoate. J Food Sci. 2003;68:1438–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb09663.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chun HH, Bin SK. Optimisation of the combined treatments of aqueous chlorine dioxide, fumaric acid and ultraviolet-C for improving the microbial quality and maintaining sensory quality of common buckwheat sprout. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2014;49:121–127. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.12283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CMFRI . Marine fish landings in India 2019. CMFRI booklet series no. 24/2020. ICAR - Kochi, India: Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Comes JE, Beelman RB. Addition of fumaric acid and sodium benzoate as an alternative method to achieve a 5-log reduction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 populations in apple cider. J Food Prot. 2002;65:476–483. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-65.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway EJ. Micro diffusion analysis and volumetric error. 5. London: Crosby Lockwood and Son Ltd; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Duan J, Cherian G, Zhao Y. Quality enhancement in fresh and frozen lingcod (Ophiodon elongates) fillets by employment of fish oil incorporated chitosan coatings. Food Chem. 2010;119:524–532. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.06.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Soto B, Aubourg SP, Calo-Mata P, Barros-Velázquez J. Extension of the shelf life of chilled hake (Merluccius merluccius) by a novel icing medium containing natural organic acids. Food Control. 2013;34:356–363. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODCONT.2013.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Soto B, Böhme K, Barros-Velázquez J, Aubourg SP. Inhibition of quality loss in chilled megrim (Lepidorhombus whiffiagonis) by employing citric and lactic acid icing. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2014;49:18–26. doi: 10.1111/IJFS.12268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Soto B, Fernández-No IC, Barros-Velázquez J, Aubourg SP. Use of citric and lactic acids in ice to enhance quality of two fish species during on-board chilled storage. Int J Refrig. 2014;40:390–397. doi: 10.1016/J.IJREFRIG.2013.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gram L, Huss HH. Microbiological spoilage of fish and fish products. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;33:121–137. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(96)01134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gram L, Trolle G, Huss HH. Detection of specific spoilage bacteria from fish stored at low (0 °C) and high (20 °C) temperatures. Int J Food Microbiol. 1987;4:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(87)90060-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Günlü A, Sipahioǧlu S, Alpas H. The effect of chitosan-based edible film and high hydrostatic pressure process on the microbiological and chemical quality of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss Walbaum) fillets during cold storage (4±1 °C) High Press Res. 2014;34:110–121. doi: 10.1080/08957959.2013.836643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hitching AD, Feng P, Matkins WD, Rippey SR, Chandler LA. Aerobic plate count. In: Tomlinsion LA, editor. Bacteriological analytical manual. 18. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: AOAC International; 1995. p. pp 4.01-4.29.. [Google Scholar]

- Hunyadi A. The mechanism(s) of action of antioxidants: from scavenging reactive oxygen/nitrogen species to redox signaling and the generation of bioactive secondary metabolites. Med Res Rev. 2019;39:2505–2533. doi: 10.1002/med.21592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICMSF (International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods) (1986) Sampling plans for fish and shellfish. In: ICMSF (ed) Microorganisms in foods 2, Sampling for microbiological analysis: principles and specific applications, 2nd edn. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Canada, pp 181–196

- Karsli B, Caglak E, Prinyawiwatkul W. Effect of high molecular weight chitosan coating on quality and shelf life of refrigerated channel catfish fillets. LWT. 2021;142:111034. doi: 10.1016/J.LWT.2021.111034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Kim MH, Song KB. Efficacy of aqueous chlorine dioxide and fumaric acid for inactivating pre-existing microorganisms and Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella typhimurium, and Listeria monocytogenes on broccoli sprouts. Food Control. 2009;20:1002–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2008.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo N, Murata M, Isshiki K. Efficiency of sodium hypochlorite, fumaric acid, and mild heat in killing native microflora and Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella typhimurium DT104, and Staphylococcus aureus attached to fresh-cut lettuce. J Food Prot. 2006;69:323–329. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-69.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoumanis K, Nychas GJE. Chemical and sensory changes associated with microbial flora of mediterranean boque (Boops boops) stored aerobically at 0, 3, 7, and 10°C. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:698–706. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.698-706.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhuang S, Liu Y, et al. Effect of grape seed extract on quality and microbiota community of container-cultured snakehead (Channa argus) fillets during chilled storage. Food Microbiol. 2020;91:103492. doi: 10.1016/J.FM.2020.103492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Caballero ME, Martínez-Alvarez O, del Gómez-Guillén MC, Montero P. Quality of thawed deepwater pink shrimp (Parapenaeus longirostris) treated with melanosis-inhibiting formulations during chilled storage. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2007;42:1029–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2006.01328.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mead GC, Adams BW. A selective medium for the rapid isolation of pseudomonads associated with poultry meat spoilage. Br Poult Sci. 1977;18:661–670. doi: 10.1080/00071667708416418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meilgaard M, Vance Civille G, Thomas Carr B (1999) Sensory Evaluation Techniques, Third Edition. CRC Press

- Mohan CO, Ravishankar CN, Srinivasa Gopal TK, et al. Effect of reduced oxygen atmosphere and sodium acetate treatment on the microbial quality changes of seer fish (Scomberomorus commerson) steaks stored in ice. Food Microbiol. 2010;27:526–534. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monirul I, Yang F, Niaz M, et al. Effectiveness of combined acetic acid and ascorbic acid spray on fresh silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) fish to increase shelf-life at refrigerated temperature. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci. 2019;7:415–426. doi: 10.12944/CRNFSJ.7.2.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Na S, Kim JH, Jang HJ, et al. Shelf life extension of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) using chitosan and ε-polylysine during cold storage. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;115:1103–1108. doi: 10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2018.04.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Toro R, Collazo-Bigliardi S, Roselló J, et al. Antifungal starch-based edible films containing Aloe vera. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;72:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos K, Triantis T, Dimotikali D, Nikokavouras J. Evaluation of food antioxidant activity by photostorage chemiluminescence. Anal Chim Acta. 2001;433:263–268. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(01)00787-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park JS, Ha JW. Ultrasound treatment combined with fumaric acid for inactivating food-borne pathogens in apple juice and its mechanisms. Food Microbiol. 2019;84:103277. doi: 10.1016/J.FM.2019.103277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira DM, Valentão P, Andrade PB. Organic acids of plants and mushrooms: Are they antioxidants? Funct Plant Sci Biotechnol. 2009;3:103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira De Abreu DA, Paseiro Losada P, Maroto J, Cruz JM. Natural antioxidant active packaging film and its effect on lipid damage in frozen blue shark (Prionace glauca) Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2011;12:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2010.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podolak RK, Zayas JF, Kastner CL, Fung DYC. Reduction of bacterial populations on vacuum-packaged ground beef patties with fumaric and lactic acids. J Food Prot. 1996;59:1037–1040. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.10.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popelka A, Abdulkareem A, Mahmoud AA, et al. Antimicrobial modification of PLA scaffolds with ascorbic and fumaric acids via plasma treatment. Surf Coatings Technol. 2020;400:126216. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.126216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X, Chen S, Liu G, Yang Q. Quality enhancement in the Japanese sea bass (Lateolabrax japonicas) fillets stored at 4 °C by chitosan coating incorporated with citric acid or licorice extract. Food Chem. 2014;162:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remya S, Mohan CO, Venkateshwarlu G, et al. Combined effect of O2 scavenger and antimicrobial film on shelf life of fresh cobia (Rachycentron canadum) fish steaks stored at 2 °C. Food Control. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.05.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rey MS, García-Soto B, Fuertes-Gamundi JR, et al. Effect of a natural organic acid-icing system on the microbiological quality of commercially relevant chilled fish species. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2012;46:217–223. doi: 10.1016/J.LWT.2011.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam KI. Chemical, sensory and shelf life evaluation of sliced salmon treated with salts of organic acids. Food Chem. 2007;101:592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmond CV, Kroll RG, Booth IR. The effect of food preservatives on pH homeostasis in Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2845–2850. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-11-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini AO, Pezza HR, Pezza L. Development of a sensitive potentiometric sensor for determination of fumaric acid in powdered food products. Food Chem. 2012;134:483–487. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.02.104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth C, Brunton NP, Fogarty C, Bolton DJ. The effect of organic acid, trisodium phosphate and essential oil component immersion treatments on the microbiology of cod (Gadus morhua) during chilled storage. Foods. 2018 doi: 10.3390/foods7120200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Zuo G, Chen F. Effect of essential oil and surfactant on the physical and antimicrobial properties of corn and wheat starch films. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;107:1302–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.09.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tango CN, Mansur AR, Kim GH, Oh DH. Synergetic effect of combined fumaric acid and slightly acidic electrolysed water on the inactivation of food-borne pathogens and extending the shelf life of fresh beef. J Appl Microbiol. 2014;117:1709–1720. doi: 10.1111/jam.12658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarladgis BG, Watts BM, Younathan MT, Dugan L. A distillation method for the quantitative determination of malonaldehyde in rancid foods. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1960;371(37):44–48. doi: 10.1007/BF02630824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Townley RR, Lanier T. Effect of early evisceration on the keeping quality of Atlantic croaker (Micropogonundulates) and grey trout (Cynoscion regalis) as determined by subjective and objective methodology. J Food Sci. 1981;46:863–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1981.tb15367.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel BF, Venkateswaran K, Satomi M, Gram L. Identification of Shewanella baltica as the most important H 2S-producing species during iced storage of Danish marine fish. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:6689–6697. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.6689-6697.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Fu S, Xiang Y, et al. Effect of chitosan gallate coating on the quality maintenance of refrigerated (4 °C) Silver Pomfret (Pampus argentus) Food Bioprocess Technol. 2016;9:1835–1843. doi: 10.1007/s11947-016-1771-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yesudhason P, Lalitha KV, Gopal TKS, Ravishankar CN. Retention of shelf life and microbial quality of seer fish stored in modified atmosphere packaging and sodium acetate pretreatment. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2014;1:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.fpsl.2014.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F, Zhuang P, Zhang L, Shi Z. Biochemical composition of juvenile cultured versus wild silver pomfret, Pampus argenteus: determining the diet for cultured fish. Fish Physiol Biochem. 2010;36:1105–1111. doi: 10.1007/s10695-010-9388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Almost all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. If anything is missing, datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.