Abstract

Asian sea bass mince gels having different adjusted moisture/water content (80 and 85%; w/w) were prepared with addition of sodium bicarbonate (SB) at various concentrations (0, 0.05 and 0.1%; w/w). Fish mince gels of 80% water content added with 0.05 and 0.1% SB (G80-0.05 and G80-0.1, respectively) had the highest increase (135–139%) in breaking force (BrF) than the respective control gel (G80) (P < 0.05). For gel with 85% water content, a lower increase (17–28%) in BrF was found with the addition of SB as compared to their corresponding control (G85). Whiteness of all samples was continuously decreased with increasing amount of SB, however the water holding capacity was increased drastically with augmenting levels of SB, regardless of the water content (P < 0.05). A loss in the elasticity of gel was attained with the addition of SB as indicated by decreasing storage modulus. A finer and more compact network was detected in a gel containing SB, irrespective of water content. Based on sensory scores, gel having 85% water content added with 0.05 and 0.1% SB had similar acceptability to the control gel (G80) containing 80% water content (commercial level). Therefore, SB at the appropriate level could improve the gelling properties with higher water holding ability of the mince gel with high acceptability.

Keywords: Asian sea bass, Sodium bicarbonate, Gelation, Textural properties, Rheology

Introduction

Fresh fish has been used to prepare fish balls or other gel-based products, which have been widely consumed in Thailand (1200 tonnes/year) and other Southeast Asian countries (Park 2005). Fish mince products are considered as a healthy food with high nutritional value (Huda et al. 2010). Fish ball is one of the important fish mince products made by setting fish paste (added with salt), followed by cooking at 90 °C. The setting is practically implemented to strengthen the gel network, mainly mediated by indigenous transglutaminase (Liu et al. 2021; Singh et al. 2019). In Thailand, ground fish meat (fish mince) has been used for preparing fish balls called “Luk-chin”. However, those products contain a high amount of added starches such as rice flour, etc. and phosphates for enhancement of textural properties. Moreover, those ingredients have been used to lower the production cost. However, starchy texture or flavor could lower the quality and acceptability. Those starches also can be related to various health concerns such as obesity, diabetes, etc., while consumption of phosphates present in the diet is associated with ill effects (Robertson et al. 2018). Thus, their usages in foods have been avoided (Hunt and Park 2014). In addition, those ingredients, especially starch, yielded fish ball with undesirable characteristics. Phosphate could result in the astringent taste. Therefore, the use of alternative additive in the presence of high-water content could produce acceptable fish balls or surimi gel, which is softer and more elastic and juicier.

Sodium bicarbonate (SB) commonly called “baking soda” is affirmed as a General Recognized as Safe (GRAS) food ingredient. It is one of the cheap and commonly available food ingredients, used in households and bakery industry. According to the FDA, the maximum daily dosage of SB is limited to 200 mEq/day (16.8 g) for consumers with the age up to 60 years old. In Thailand, SB has been used in various kinds of food such as fish, chicken, and pork meat balls to improve the textural properties and water holding capacity. Recently, it was used to improve water holding capacity (WHC) as well as gelling properties of fish mince or surimi gel (Liu et al. 2021). SB was incorporated in the soaking solution for augmenting WHC of Pacific white shrimp, in which its efficacy was equivalent to phosphate compounds (Chantarasuwan et al. 2011b). Bledsoe et al. (2000) reported the enhanced textural properties of Alaska pollock and Pacific whiting surimi gel in the presence of SB (0.075–0.125%). Furthermore, SB combined with 5% sorbitol and 4% sugar acted as a cryoprotectant in surimi from Alaska pollock during both conventional and fast freezing processes (Hunt and Park 2014). In previous work, 0.3% SB in combination with 8% sucrose/sorbitol has been used as stabilizer during frozen storage of Nile tilapia mince (Kaewjumpol et al. 2013). Although surimi, washed fish mince, shows the better gelling property since highly concentrated myofibrillar proteins can undergo aggregation to form the ordered network more effectively than unwashed mince, it was tedious for washing and dewatering processes. In addition, the wash water must be treated properly before discharge, thus increasing the cost for water treatment. Nowadays, Asian sea bass has increasing demand and it can be used for production of several value-added product such as fish ball, etc., apart from fillets or slices. However, no information on the gel properties of Asian sea bass fish mince exists. In addition, the use of SB in fish mince gel, particularly for enhancement of WHC as well as textural properties in the presence of high amount of water could be a means to develop the jelly product from unwashed Asian sea bass mince. This can be applied for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in production of unwashed Asian sea bass mince jelly products, especially fish ball or fish bar. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to determine textural, microstructural, and sensorial properties of unwashed Asian sea bass mince gel with different adjusted moisture contents (AMCs) as influenced by SB at various levels.

Material and methods

Chemicals and Asian sea bass

All chemicals used were of analytical grade. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME), glycerol, wide range molecular weight markers and glutaraldehyde were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). N, N, N′, N′-tetramethyl ethylene diamine (TEMED) and all other chemicals for electrophoresis were procured from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA). The purity of the used chemicals was ≥ 99.0%. The fresh Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer) were brought on ice to the laboratory from a fish market.

Preparation of unwashed mince gel

Firstly, the fish muscle meat (without red meat at the lateral line) was rinsed with chilled water (0–2 °C) to remove blood, followed by blending using a food blender for 1 min to obtain the homogenous mince. The prepared mince having moisture content of 78.16% determined by AOAC method (AOAC 2002) was kept in ice until further processing (not more than 3 h). The obtained mince was blended for 1 min in the presence of 3% (w/w) salt to form paste (solubilized myofibrillar proteins). Thereafter, mince paste was divided into two parts. For the first part, paste (200 g) was added with cold distilled water (18.4 mL) to obtain the moisture contents of 80% (w/w) followed by blending for another 2 min. Thereafter, sodium bicarbonate (SB) was added at three final levels, 0, 0.05 and 0.1% (w/w) and blended for another 1 min. Those concentrations of SB were selected from the preliminary study. The resulting paste samples were filled into a polyvinylidene chloride casing (diameter: 25 mm) and both ends of the casing were closed tightly. The whole process was performed below 8–10 °C. For gelation, the casing added with paste was immersed into hot water bath (Memmert, Schwabach, Germany) at 40 °C for 30 min, followed by cooking at 90 °C for 20 min. Successively, all samples were cooled in iced water for 60 min and stored overnight at 4 °C before analyses. Similarly, for the second part of mince paste, gels containing different levels of SB were prepared as described previously, except the moisture content of paste (200 g) was adjusted to 85% (w/w) with cold water (93.27 mL). The gel from fish mince with AMC of 80% and added with SB at 0, 0.05 and 0.1% were named as G80, G80-0.05 and G80-0.1, respectively. Samples having 85% AMC with SB at 0, 0.05, and 0.1% were denoted as G85, G85-0.05, and G85-0.1, respectively. Before analysis, casing was removed, and samples having diameter of 25 mm were cut into the length of 25 mm (except for expressible moisture content) and then allowed to stand at room temperature for 1 h.

Analyses

Breaking force (BrF) and deformation (DeF)

BrF and DeF of gels samples were examined using a penetration method with the help of TA-XT2 texture analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, Surrey, United Kingdom), equipped with spherical plunger made up of stainless steel (diameter: 5 mm), which was used at a penetration velocity of 60 mm/min (Singh et al. 2020).

Expressible moisture content (EMC)

EMC of gel samples were measured using the standard weight method as described by Buamard and Benjakul (2017). Gels were cut to obtain a 5 mm thickness or height and weighed (X). Samples were then put between Whatman paper No. 4 (2 pieces) on the top and 3 pieces at the bottom of the samples. A standard weight (5 kg) was located on the top and left for 2 min. The pressed gel samples were weighed (Y). EMC was measured using the following calculation:

Whiteness

Whiteness of samples were measured following the methods of Wijayanti et al. (2021). The color of fish mince gel was analyzed using Hunterlab (ColorFlex, Hunter Associates Laboratory, Reston, VA, USA). Lightness (L*), redness/greenness (a*) and yellowness/blueness (b*) were measured. Whiteness index was computed using the subsequent equation:

Protein pattern

Protein patterns of mince gels were determined with the aid of sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using the method explained by Laemmli (1970). The gel samples (3 g) were heated in 27 mL of 5% (w/v) SDS solution at 85 °C. The mixture was then homogenized using a homogenizer (IKA Labortechnik, Selangor, Malaysia) at a speed of 11,000 rpm for 2 min. The homogenate was then incubated at 85 °C for 1 h to dissolve total proteins. The samples were centrifuged using a centrifuge (MIK-RO20, Hettich Zentrifugan, Germany) at 3500×g for 20 min to remove undissolved debris. Protein concentration of the supernatant was determined by the Biuret method (Robinson and Hogden 1940) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Then the proteins from each sample were separated using 10% (w/v) running gel and 4% (w/v) stacking gel and stained for 24 h using 0.05% (w/v) Coomassie Blue R-250 in 50% (v/v) methanol and 7.5% (v/v) acetic acid, followed by destaining using the mixture of 30% (v/v) methanol and 10% (v/v) acetic acid for 6 h.

Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) images

Microstructures of all the samples were viewed using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM) (Apreo, FEI, the Netherlands). The sample preparation was performed as per the method described by Singh et al. (2020). In brief, gel blocks with a thickness of 2–3 mm were fixed with 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) for 3 h at room temperature, followed by rinsing with distilled water. Fixed specimens were dehydrated in ethanol with serial concentrations of 25, 50, 70, 80, 90 and 100% (v/v). Samples were subjected to critical point drying using CO2 as transition fluid. The prepared samples were mounted on a bronze stub and sputter-coated with gold and visualized using SEM. Three images were analyzed for each treatment.

Dynamic rheology

All fish mince pastes added without and with SB at various levels were prepared as described in Sect. 2.2. Each paste (1 g) was subjected to dynamic rheological analysis using HAAKE RheoStress1 rheometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Karlsruhe, Germany) following the method of Buamard and Benjakul (2018). The oscillation frequency of 1 Hz with 1% deformation was used for the analysis. These conditions gained a linear response in the viscoelastic region. The temperature sweep was recorded during heating from 20 to 90 °C with heating rate of 1 °C/min. Silicone oil was used to minimize water evaporation of fish mince pastes during measurement.

Textural profile analysis (TPA)

The gel samples (height: 25 mm and diameter: 25 mm) without the casing were used for the TPA. Textural parameters such as hardness, cohesiveness, springiness, chewiness, and gumminess of the samples were examined using a Model TA-XT2 texture analyzer (Stable Micro System, Surrey, UK) installed with cylinder probe with a diameter of 2.5 cm (Buamard and Benjakul 2018).

Sensory properties

Acceptability of all the gel samples was evaluated using a 9-point hedonic scale by 80 panelists (22 males and 58 females, aged 18–55 years) as per the procedure of Meilgaard et al. (2006). The panelists who had no seafood allergy and often consumed fish mince products were recruited for analysis. The panelists were asked to evaluate appearance, color, odor, taste, texture, overall liking of gel samples. The 9-point hedonic scale, in which 1, extremely dislike; 2, very much dislike; 3, moderately dislike; 4, slightly dislike; 5, neither like nor dislike; 6, slightly like; 7, moderately like; 8, very much like; 9, extremely like, was used for the sensory analysis.

Zeta potential and pH

The fish paste (10 g) added with various AMC and SB levels was homogenized in distilled water (90 mL) (Techaratanakrai et al. 2011). The probe of a pH700 meter (Eutech Instruments, Singapore) was directly placed in the homogenates and the pH was recorded.

The fish mince protein was extracted with 0.6 M KCl following the method of Buamard and Benjakul (2017). Fish muscle protein solutions containing SB at levels equivalent to those found in the corresponding gels were determined for zeta potentials using a zeta potential analyzer (Brookhaven ZetaPALS, Brookhaven Instruments, NY, USA). All measurements were performed at a temperature and medium refractive index of 25 °C and 1.333, respectively. Five milliliters of samples were evaluated at an angle of 173° after 2 min of autocorrelation of zeta potential. The averages of ten readings were recorded.

Statistical analysis

A completely randomized design was used for the entire study. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. Data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and comparison of means via Duncan’s multiple range tests (P < 0.05) was done using a SPSS 23 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA).

4. Results and discussion

4.1. BrF and DeF

BrF and DeF of gels having different AMC and added with varying amounts of SB are shown in Fig. 1a, b, respectively. In general, the force that can withstand by a material before breaking is called BrF and the distance at which that material breaks is called DeF. When AMC was increased to 85% (G85), lower BrF of gels was noticed as compared to the samples with lower AMC (80%; G80) in the absence of SB (P < 0.05). An upsurge in BrF was noticed for G80-0.05 and G80-0.1 samples by 135 and 139%, respectively, compared to that of G80 (P < 0.05). Nevertheless, both samples, G80-0.05 and G80-0.1, had similar BrF (P > 0.05). When SB was added to G85 samples, slight increases in BrF were found (P < 0.05). G85-0.1 sample showed higher BrF than G85 and G85-0.05 (P < 0.05). However, only slight upsurge in BrF (17 and 28%) was found when SB at 0.05 and 0.1 was incorporated in G85, respectively. For DeF, similar values were noticed for G80 and G85 samples (P > 0.05). However, when SB was added, the higher DeF was obtained for G80-0.05, G80-0.1, and G85-0.1 sample, compared to others (P < 0.05). Moreover, G85-0.05 sample had similar DeF to G80 and G85 samples (P > 0.05). Normally, several bondings such as both covalent and non-covalent bonds could be formed during the setting of fish mince at 40 °C. The ε-(γ-glutamyl) lysine linkage, a non-disulfide bond formed between myosin heavy chain (MHC) by an endogenous transglutaminase (TGase), was involved in strengthening the gel network (Singh et al. 2019). The highest increase in BrF of G80 samples with the addition of SB was more likely due to the increasing pH (away from the isoelectric point), which might cause the dissociation or dissolution of myofibrillar proteins (Lee et al. 2015). These phenomena might result in higher solubility and unfolding of myofibrillar proteins. This plausibly enhanced ionic or hydrophobic interaction of fish proteins (Lu et al. 2021). Besides those aforementioned interactions, the exposure of cysteine might be favored in the formation of disulphide bond, which could increase the gel strength (Lavoisier et al. 2019; Singh et al. 2020). Chantarasuwan et al. (2011a) observed decreasing turbidity of natural actomyosin solution from Pacific white shrimp with increasing SB levels, which was related to the increases in solubility. Bledsoe et al. (2000) observed the improved gel properties of pollock surimi, with the addition of 0.1–0.125% of SB in combination with 0.3% phosphate salt. Similarly, Alaska pollock surimi added with 3% sodium chloride and 1.5% SB had the increases in BrF and DeF from 10.41 N and 11.9 mm (pH 7.04) to 14.64 N and 15 mm (pH 8.12), respectively (Nozaki and Nakamura 2004). The lower BrF of G85 samples as compared to the G80 samples was more likely due to the lower content of myofibrillar proteins with an increasing amount of water added. Generally, myofibrillar proteins are the major proteins accountable for the establishment of the gel network (Sun and Holley 2011). Thus, the different levels of water and SB had a profound influence on the strength and elasticity of the fish mince gel.

Fig. 1.

Breaking force (a), deformation (b), expressible moisture content (c), whiteness (d) of unwashed Asian sea bass mince gels, pH of mince paste (e) and zeta potential of mince protein solution (f) with different adjusted moisture contents added without and with sodium bicarbonate at various concentrations. Different uppercase letters on the bars within the same sodium bicarbonate level indicate a significance difference having (P < 0.05). Different lowercase letters on the bars indicate a significance difference between all samples (P < 0.05). G80: gels having adjusted moisture content of 80% (w/w) without sodium bicarbonate, G80-0.05 and G80-0.1: gels having adjusted moisture content of 80% (w/w) added with 0.05 and 0.1% sodium bicarbonate (w/w), respectively. G85: gels having adjusted moisture content of 85% (w/w) without sodium bicarbonate, G85-0.05 and G85-0.1: gels having adjusted moisture content of 85% (w/w) added with 0.05 and 0.1% sodium bicarbonate (w/w), respectively

Expressible moisture content (EMC)

EMC has been used to examine the potential of gel to absorb water, so called water holding capacity (WHC). In general, the gels with less EMC have the higher potential to imbibe water (Singh et al. 2019). Three-dimensional protein gel network formed during setting, cooking and subsequent cooling have the capability to hold water to a high extent (Buamard and Benjakul 2017; Singh et al. 2020). Moreover, in cooled gels, hydrogen bonds could help to entrap water in gel network (Damodaran and Parkin 2017). EMC was decreased with increasing SB levels (Fig. 1c), irrespective of AMC of the samples (P < 0.05). G80-0.1 sample exhibited the lowest EMC (P < 0.05). Overall, G80 samples showed a lower EMC than the G85 samples at all SB levels added (P < 0.05). Lower EMC of SB added samples, especially at higher levels, was likely associated with the ionic interactions between charged protein chains and water at higher pH (Bledsoe et al. 2000). Various studies have reported the increased WHC of myofibrillar proteins with increasing pH (Ni et al. 2014; Shen et al. 2019). Moreover, negatively charged domain on protein surface could help dissociate the actomyosin complex, thus augmenting the space for water to be entrapped (Benjakul et al. 2010). Normally, in an aqueous system, protein has a zero-net charge at its isoelectric point, at which positive and negative charges are balanced. Changes in net surface charge or pH change were most likely related to unfolding or exposure of charged amino acids. Coincidently, different degrees of protonation or deprotonation of protein molecules could be obtained (Benjakul et al. 2010; Chantarasuwan et al. 2011b). Denatured proteins consist of negative and positive polarization center of –COO and –NH groups in proteins chains, in which multilayer water system can be formed (Damodaran and Parkin 2017). Although the lowest EMC value was observed for all G80 samples (1.32–5.18%), the low EMC was found for G85-0.1 (2.42%), followed by G85-0.05 samples (6.32%). The result indicated that SB at sufficient levels (0.1%) could help to develop gel network to imbibe water effectively, even though the concentration of meat proteins became diluted. Despite increasing water content, WHC of gel samples could be improved via the SB addition.

4.3. Whiteness

The whiteness of the gel samples in the presence and absence of SB at various levels is shown in Fig. 1d. The maximum whiteness was noticed for both control gels (G80 and G85) (P < 0.05). When SB was incorporated into the gels, whiteness was diminished with increasing level of SB for G80 samples (P < 0.05). However, SB at both levels resulted in similar whiteness of G85 samples (P > 0.05). This could be related to the increasing solubility of various fish muscle proteins, which might result in the release of pigments such as myoglobin and hemoglobin from the fish muscles. Those pigments might be oxidized during the high temperature setting and cooking of gels, thus causing lower whiteness. In general, all those water-soluble pigments, sarcoplasmic protein, lipids, etc. are removed from fish mince during the washing process. This results in improved whiteness of washed fish mince gel, compared with unwashed mince gel (Singh and Benjakul 2018). In the current study, whole fish mince was used without washing; therefore, it contained a high amount of sarcoplasmic proteins, lipids or pigments, which might be oxidized during gel preparation. Moreover, the formation of denser structure could lead to higher light absorption, resulting in lower whiteness (Hu et al. 2015). Similarly, Chanarat and Benjakul (2013) observed lower whiteness of gels from India mackerel fish protein isolates when added with microbial transglutaminase (MTGase) and suggested that the denser gel network induced by increased MTGase possessed the higher light absorption, leading to a darker color of gels. Therefore, the addition of SB into fish mince gel resulted in lower whiteness.

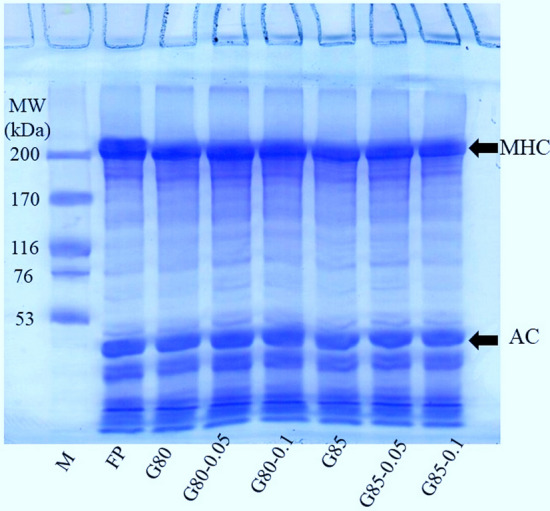

4.4. Protein patterns

Protein patterns of fish mince and gels added without and with SB at several levels are shown in Fig. 2. In general, fish proteins consist of MHC and actin of MW varying between 200–210 and 45–47 kDa, respectively as the major myofibrillar proteins (Ochiai and Ozawa 2020; Fang et al. 2021). This was advocated by the prominent band-intensity of the aforementioned proteins (lane FP). During setting, MHC band intensity was lowered to some degree for all the samples. This was owing to cross-linking via the formation of the non-disulfide linkage of MHC by TGase (Singh et al. 2020). Moreover, hydrolysis of fish proteins facilitated by the indigenous proteases firmly bound to the muscle could result in MHC degradation in this temperature range (Singh et al. 2020). Nevertheless, the actin band was not affected during setting, irrespective of SB additions. This might be due to its lower affinity as a substrate for TGase (Petcharat and Benjakul 2017). SB showed no adverse impact on the formation of non-disulfide covalent bonding between MHCs. Based on pH of gel, which was between neutral to slightly alkaline pH range, TGase could still function for protein cross-linking. It was postulated that covalent bonds including disulphide bonds and non-disulphide covalent bonds contributed to gel strength. Moreover, hydrogen bonds, ionic and hydrophobic interactions in the samples added with SB were also involved in the formation of gel network, as evidenced by increased BrF (Fig. 1). Those weak bondings could be destroyed by the SDS and high temperature (85 °C) used for the preparation of sample prior to analysis (Buamard and Benjakul 2017, 2018). The result indicated that proteins in unwashed mince were still cross-linked in the presence of SB and SB did not interfere in the setting phenomenon, which was evidenced by no difference in MHC band intensity.

Fig. 2.

Protein patterns of unwashed Asian sea bass mince gels with different adjusted moisture contents added without and with sodium bicarbonate at various concentrations. Caption: see Fig. 1. M: high molecular weight markers; MHC: myosin heavy chain; AC: actin; MW: molecular weight; kDa: kilodalton

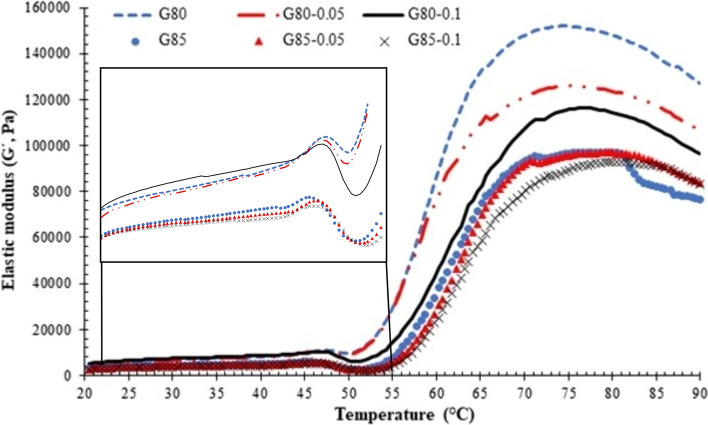

4.5. Rheological properties

Variations in elastic moduli (G′) of unwashed mince paste in the absence and presence of SB at several levels as a function of heating temperature (20–90 °C) are shown in Fig. 3. During the shearing process, the stored deformation energy of samples tested is measured as G′, which denotes the elastic behavior of a sample (Singh et al. 2020). Overall, the highest G′ values were noticed for G80 samples as compared to the G85 samples. As shown in the inset, the G80-0.1 samples heated in the temperature range of 20–43 °C had the highest G′ value, followed by G80-0.05 and G80 samples, respectively. A similar trend was also found for G85 samples. At 45–55 °C, a sharp decline in G′ value of all the samples was probably mediated by proteolysis of myofibrillar proteins induced by heat activated proteases tightly bound to fish muscles or sarcoplasmic proteases (Buamard and Benjakul 2017; Singh and Benjakul 2017, 2018). In addition, dissociation or unfolding of proteins in fish mince increased the fluidity of mince paste, leading to the lower G′ value (Buamard and Benjakul 2017, 2018). With further increasing temperature, aggregation or entanglement of unfolded proteins enhanced the G' values (Buamard and Benjakul 2017, 2018). However, the G′ value of G80-0.1 was lower as compared to those of G80 and G80-0.05 samples and the highest G′ value was obtained for G80 till 90 ºC. The initial increase in G′ values (around 20–45 °C) of all samples was more likely associated with the formation of protein network via weak bondings between protein chains, in which myofibrillar proteins in the paste were dissociated from its super helix structure (Luo et al. 2020). However, higher increase in G′ for SB added samples was possibly related to the higher unfolding of protein chains correlated with augmented solubility. As a consequence, higher inter-connections between adjacent protein chains occurred as compared to the control samples (without SB). When the temperature was increased further from 50 to 65 °C, the lower G′ values for all the G80 samples might be due to proteolysis of proteins by both sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar bound endogenous proteases, which were still active at 55–65 °C. The addition of SB at higher level caused the lower G′. Higher unfolded proteins in the presence of SB could favor hydrolysis by proteases. This was supported by the higher decrease in G′ value. A similar trend was also found for all G85 samples. However, G′ values were lower in all G85 samples than those of G80 samples. This could be due to the lower protein content associated with the higher amount of water (85%). At temperature of 75–90 ºC, the decline in G′ was found for all the sample. Heating at high temperature could destroy some weak bonds, resulting in lower interaction as witnessed by the lowered G′. Overall, the addition of SB resulted in lower G′ of resulting gels in a dose-dependent manner. Therefore, SB incorporation had a direct impact on the viscoelastic characteristics of unwashed mince paste.

Fig. 3.

Dynamic rheology of unwashed Asian sea bass mince pastes with different adjusted moisture contents added without and with sodium bicarbonate at various concentrations. Caption: see Fig. 1

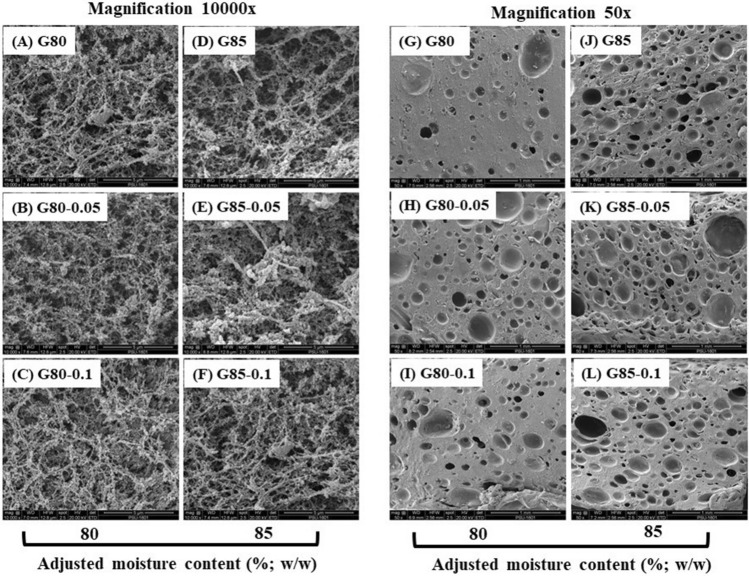

4.6. Microstructure

Microscopic structures of unwashed mince gel in the absence and presence of SB at varying levels are displayed in Fig. 4. For gels without SB, G85 had a looser and coarser network with a larger void/cavity than G80 sample (Fig. 4a, e). This was evidenced by the lower BrF of G80 sample (Fig. 1a). However, when SB was added to both gels, G80-0.05 and G80-0.1 samples had the denser and more regular network with smaller and lesser voids or holes as compared to G85-0.05 and G85-0.1 samples. For G85 samples added with SB, although microstructure showed an ordered or regular gel network, it had lower connections between protein chains and a looser network as compared to the G80 samples. This was due to the lower amount of protein present in G85 samples. The result was also reconfirmed with the presence of a porous surface (having more holes) when visualized at lower magnification (50×) (Fig. 4f–k). Those pores could be formed due to the generation of carbon dioxide (CO2) bubbles from the SB (NaHCO3), which were released during heating (Massingue 2018). Ramadhan et al. (2014) also reported those scattered pores with different sizes in surimi prepared from duck meat, which could hold more water. The gel network with finer structure and the smaller hole provides a higher surface for water adsorption of water, which were in line with higher WHC of gels containing SB (Fig. 1c). Thus, SB showed a potential to adsorb more water for all the gels.

Fig. 4.

Microstructure of unwashed Asian sea bass mince gels with different adjusted moisture contents added without and with sodium bicarbonate at various concentrations. Caption: see Fig. 1

Texture profile

Texture profiles of the samples added without and with SB are shown in Table 1. A similar value of hardness was found for G80 and G85 samples (P > 0.05). Normally, hardness is the force required to compress food, which indicates the ability of gel network formation (Singh et al. 2020). An increase in hardness was found in both G80-0.05 and G80-0.1 (P < 0.05). G80-0.05 sample showed the highest hardness, followed by G80-0.1 (P < 0.05). The lowest hardness was obtained for G85-0.05 sample (P < 0.05). The result was generally in accordance with the BrF (Fig. 1a). All the samples had similar springiness (P > 0.05). In general, springiness show the elasticity of food products (Rosenthal 2010). Cohesiveness is the ratio of area under the peaks that shows the recovery after deformation. The highest cohesiveness was noticed in G85-0.1 sample, whereas the lowest value was noticed for G80 and G80-0.05 samples (P < 0.05). Those results were mainly supported by the presence of a higher amount of water, which allowed the samples to recover back to original form. This phenomenon determined the elasticity of gels. For the remaining samples, no difference in cohesiveness was noticed (P > 0.05). Gumminess reflects both high viscosity and stickiness of material; while chewiness is the force needed to chew a solid food to the point, which is sufficient for swallowing (Peleg 2019). Similar to the hardness, gumminess and chewiness of gels having 80% AMC were increased with the addition of SB as compared to those of G80 sample. Overall, the incorporation of SB, especially at higher concentrations, improved the textural properties of unwashed mince gel as compared to the control gels (without additives), irrespective of AMC, especially the strength and elasticity as well as juiciness.

Table 1.

Textural profile of unwashed Asian sea bass mince gels with different adjusted moisture contents added without and with sodium bicarbonate at various concentrations

| Samples | Hardness (N) | Springiness (cm) | Cohesiveness | Gumminess (N) | Chewiness (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G80 | 27.67 ± 0.92cA | 0.93 ± 0.03aA | 0.70 ± 0.01cA | 18.64 ± 1.68cA | 16.23 ± 1.11cA |

| G80-0.05 | 60.80 ± 1.35aA | 0.91 ± 0.01aA | 0.69 ± 0.00cB | 41.26 ± 2.11aA | 37.33 ± 2.27aA |

| G80-0.1 | 52.82 ± 3.09bA | 0.91 ± 0.02aA | 0.71 ± 0.01bB | 35.97 ± 1.57bA | 31.92 ± 1.87bA |

| G85 | 27.86 ± 0.88cA | 0.92 ± 0.01aA | 0.71 ± 0.01bcA | 18.73 ± 2.08cA | 18.19 ± 0.27cA |

| G85-0.05 | 27.17 ± 1.45cdB | 0.93 ± 0.02aA | 0.70 ± 0.01bcA | 19.69 ± 0.32cB | 17.29 ± 0.63cB |

| G85-0.1 | 24.26 ± 0.99 dB | 0.94 ± 0.02aA | 0.73 ± 0.01aA | 17.43 ± 0.96cB | 16.60 ± 0.77cB |

Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Different uppercase superscripts in the same column within the same sodium bicarbonate level indicate significance difference (P < 0.05). Different lowercase superscripts in the same column indicate significance difference among all gel samples (P < 0.05). G80: gels having adjusted moisture content of 80% (w/w) without sodium bicarbonate, G80-0.05 and G80-0.1: gels having adjusted moisture content of 80% (w/w) added with 0.05 and 0.1% sodium bicarbonate (w/w), respectively. G85: gels having adjusted moisture content of 85% (w/w) without sodium bicarbonate, G85-0.05 and G85-0.1: gels having adjusted moisture content of 85% (w/w) added with 0.05 and 0.1% sodium bicarbonate (w/w), respectively

Acceptability

Likeness score for appearance, color, odor, and taste of gels prepared from unwashed Asian sea bass was not different among all the samples (P > 0.05) (Table 2). Although SB incorporation resulted in the lower whiteness, it had no adverse impact on the consumer acceptability for the color of the samples. For texture, the highest liking score was noticed for G80-0.05 sample, followed by G80-0.1 and G80 samples, respectively (P < 0.05). Overall, G85 samples showed a lower liking score for texture as compared to G80. When SB at both levels was added to G85 sample, the increases in liking scores were noticed (P < 0.05). Moreover, both G85-0.05 and G85-0.1 samples had similar liking scores for texture (P > 0.05). Therefore, SB was able to improve the texture of G85 samples. For the overall liking score, a higher score was attained for G80 samples than the G85 (P < 0.05). No differences in overall liking score were noticed among all the samples added with SB at both levels, regardless of AMC (80 and 85%). Overall, the SB at a concentration of 0.05% was optimum for improving the acceptability of gels. In general, all the liking scores were higher than the acceptable limit 5, which also suggested that the addition of a higher amount of water (85%) in combination with 0.05 or 0.1% of SB had no negative impacts on the consumer acceptability.

Table 2.

Likeness score of unwashed Asian sea bass mince gels with different adjusted moisture contents added without and with sodium bicarbonate at various concentration

| Samples | Appearance | Colour | Odour | Texture | Taste | Overall likeness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G80 | 7.89 ± 0.78aA | 8.00 ± 0.71aA | 7.44 ± 0.73aA | 6.64 ± 0.30cA | 7.44 ± 0.88aA | 7.09 ± 0.33bA |

| G80-0.05 | 7.89 ± 0.78aA | 7.89 ± 0.78aA | 7.67 ± 0.50aA | 8.22 ± 0.83aA | 7.67 ± 0.87aA | 8.22 ± 0.53aA |

| G80-0.1 | 7.56 ± 1.01aA | 8.00 ± 0.50aA | 7.78 ± 0.67aA | 7.33 ± 0.50bA | 7.56 ± .88aA | 7.88 ± 0.33aA |

| G85 | 7.56 ± 1.00aA | 7.89 ± 0.60aA | 7.67 ± 1.00aA | 6.00 ± 0.33dB | 7.22 ± 0.97aA | 6.32 ± 0.48cB |

| G85-0.05 | 8.00 ± 0.87aA | 8.11 ± 0.78aA | 7.56 ± 0.53aA | 6.78 ± 0.57cB | 7.33 ± 0.71aA | 7.33 ± 0.61bA |

| G85-0.1 | 8.11 ± 0.78aA | 8.22 ± 0.67aA | 7.56 ± 0.67aA | 6.78 ± 0.43cB | 7.56 ± 0.53aA | 7.22 ± 0.51bA |

Values are mean ± SD (n = 80). Different uppercase superscripts in the same column within the same sodium bicarbonate level indicate significance difference (P < 0.05). Different lowercase superscripts in the same column indicate significance difference among all gel samples (P < 0.05). The 9-point hedonic scale used, where 1, extremely dislike; 2, very much dislike; 3, moderately dislike; 4, slightly dislike; 5, neither like nor dislike; 6, slightly like; 7, moderately like; 8, very much like; 9, extremely like. Caption: See Table 1

pH and Zeta potential

pH and zeta potential of meat proteins are shown in Fig. 1e, f, respectively. Similar pHs of G80 and G85 paste samples were found (6.23 and 6.25), respectively (P > 0.05). However, when samples were added with SB, the pH was increased for both G80 and G85 paste samples (6.32–6.64 and 6.35–6.85, respectively). Comparing between G80 and G85 paste samples, higher pH was found for G85 sample when SB was added. The higher protein content in the G80 sample showed greater buffering capacity, which could lower pH changes more effectively. Gelling properties of the fish proteins, especially myofibrillar proteins, are greatly impacted by the change in pH. Myofibrillar proteins at higher pH could expose the functional groups for the endogenous TGase as well as other interactions, especially aggregation (Liu et al. 2010). The pH higher than the isoelectric point caused myosin swelling associated with an augmented amount of water bound with proteins (Liu et al. 2010). The result was in line with the increasing WHC of gel samples (Fig. 1c).

For zeta potential, the lowest value was noticed for fish mince protein solution representing G80-0.1 paste (− 19.90 ± 4.06 mV), followed by the solution representing G80-0.05 and G85-0.1 paste (− 18.72 ± 0.83 and − 17.18 ± 5.57 mV, respectively) (Fig. 1f). Overall, the samples without SB addition had higher zeta potential than those containing SB (P < 0.05). The solution representing G80 paste had the lower zeta potential (− 14.95 ± 2.06) than that of G85 solution (− 11.74 ± 1.54) (P < 0.05). This could be related to the lower protein concentration of the latter, leading to the lower charge. On the other hand, solution representing G85-0.05 paste (− 14.66 ± 1.69) had a lower value, confirming that SB contributed to the increased negative charge. In general, sodium chloride might facilitate the solubilization of meat proteins. In the presence of SB, the ability of proteins to be deprotonated was higher. As a result, the negative charge could be more pronounced (Benjakul et al. 2010). HCO3− anion from SB could also neutralize the positive change moiety from NH3+ of the basic amino acid side chain. This could lead to an increase in negative charge, which caused the repulsion between the protein chains, which can improve the proteins solubility. In general, protein solubility is the prerequisite of functional properties of proteins. Thus, myofibrillar proteins with higher solubility more likely improved the textural and water holding properties of resulting gels.

Conclusion

Sodium bicarbonate (SB) directly influenced the gel properties of unwashed Asian sea bass mince. The addition of SB resulted in higher breaking force and deformation. SB at a higher level (0.1%) yielded an excellent water holding capacity for gels containing 80 or 85% moisture contents as indicated by the lowest EMC. The addition of SB at all levels resulted in lower whiteness, however, it showed no negative impact on consumer acceptability. The viscoelastic characteristics of gels were greatly influenced by SB addition. SB addition did not affect the polymerization of MHC. Based on the sensory property, gel containing 80% moisture content had the highest likeness score for texture (P < 0.05), when added with 0.05% SB compared to the remaining samples. Moreover, gels having higher moisture content (85%) showed improved textural likeness, when added with SB as compared to the respective control gel sample. SB addition resulted in the formation of a finer and denser network for gels having different water contents. The negative zeta potential and higher pH of extracted fish meat protein were associated with unfolding or dissociation of protein chains, which resulted in higher solubility and interactions among those chains. Thus, SB at 0.05% could be used for increasing water holding capacity and improving both textural and sensorial properties of the resulting gel containing high amount of water (85%).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and S.B.; methodology, A.S. and N.B..; software, A.S.; validation, A.S., S.B. and A. Z..; formal analysis, A.S. and N.B.; investigation, A.S. and N.B,; resources, S.B.; data curation, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, S.B. and A.Z.; visualization, A.S and; supervision, S.B.; project administration, S.B.; funding acquisition, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Prince of Songkla University (PSU), Hat Yai, Thailand (Grant No. AGR6402088N).

Availability of data and materials

Data are not shared.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have not disclosed any competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve any human or animal testing.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- AOAC (2002) Official Methods of Analysis. In Association of Official Analytical Chemists (16 ed.). Washington, DC.

- Benjakul S, Thiansilakul Y, Visessanguan W, Roytrakul S, Kishimura H, Prodpran T, Meesane J. Extraction and characterisation of pepsin-solubilised collagens from the skin of bigeye snapper (Priacanthus tayenus and Priacanthus macracanthus) J Sci Food Agric. 2010;90:132–138. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe GE, Rasco BA, Pigott GM. The affect of bicarbonate salt addition on the gel forming properties of Alaska pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) and Pacific whiting (Merluccius productus) surimi. J Aquat Food Prod Technol. 2000;9:31–45. doi: 10.1300/J030v09n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buamard N, Benjakul S. Cross-linking activity of ethanolic coconut husk extract toward sardine (Sardinella albella) muscle proteins. J Food Biochem. 2017;41:e12283. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buamard N, Benjakul S. Combination effect of high pressure treatment and ethanolic extract from coconut husk on gel properties of sardine surimi. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2018;91:361–367. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.01.074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chanarat S, Benjakul S. Impact of microbial transglutaminase on gelling properties of Indian mackerel fish protein isolates. Food Chem. 2013;136:929–937. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantarasuwan C, Benjakul S, Visessanguan W. The effects of sodium bicarbonate on conformational changes of natural actomyosin from Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) Food Chem. 2011;129:1636–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantarasuwan C, Benjakul S, Visessanguan W. Effects of sodium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate on yield and characteristics of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) Food Sci Technol Int. 2011;17:403–414. doi: 10.1177/1082013211398802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran S, Parkin KL (2017) Amino acids, peptides, and proteins. In: Fennema’s food chemistry. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp. 235–356

- Fang Q, Shi L, Ren Z, Hao G, Chen J, Weng W. Effects of emulsified lard and TGase on gel properties of threadfin bream (Nemipterus virgatus) surimi. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2021;146:111513. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Liu W, Yuan C, Morioka K, Chen S, Liu D, Ye X. Enhancement of the gelation properties of hairtail (Trichiurus haumela) muscle protein with curdlan and transglutaminase. Food Chem. 2015;176:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huda N, Shen YH, Huey YL, Dewi RS. Ingredients, proximate composition, colour and textural properties of commercial Malaysian fish balls. Pak J Nutr. 2010;9:1183–1186. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2010.1183.1186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt A, Park JW. Comparative study of sodium bicarbonate on gelling properties of Alaska pollock surimi prepared at different freezing rates. J Food Qual. 2014;37:349–360. doi: 10.1111/jfq.12099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaewjumpol G, Thawornchinsombut S, Ahromrit A, Rojanakorn T. Effects of bicarbonate, xanthan gum, and preparation methods on biochemical, physicochemical, and gel properties of Nile tilapia (Oreochomis niloticus Linn) mince. J Aquat Food Prod Technol. 2013;22:241–257. doi: 10.1080/10498850.2011.642072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoisier A, Vilgis TA, Aguilera JM. Effect of cysteine addition and heat treatment on the properties and microstructure of a calcium-induced whey protein cold-set gel. Curr Res Food Sci. 2019;1:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.crfs.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Sharma V, Brown N, Mohan A. Functional properties of bicarbonates and lactic acid on chicken breast retail display properties and cooked meat quality. Poult Sci. 2015;94:302–310. doi: 10.3382/ps/peu063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Zhao S-m, Liu Y-m, Yang H, Xiong S-b, Xie B-j, Qin L-h. Effect of pH on the gel properties and secondary structure of fish myosin. Food Chem. 2010;121:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.12.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Yuan Y, Qin Y, Feng A, He Y, Zhou D, et al. Sweet potato starch addition together with partial substitution of tilapia flesh effectively improved the golden pompano (Trachinotus blochii) surimi quality. J Text Stud. 2021;52:197–206. doi: 10.1111/jtxs.12574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F, Kang Z-L, Wei L-P, Li Y-P. Effect of sodium bicarbonate on gel properties and protein conformation of phosphorus-free chicken meat batters. Arab J Chem. 2021;14:102969. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.102969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Guo C, Lin L, Si Y, Gao X, Xu D, et al. Combined use of rheology, LF-NMR, and MRI for characterizing the gel properties of hairtail surimi with potato starch. Food Bioproc Technol. 2020;13:637–647. doi: 10.1007/s11947-020-02423-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massingue AA. Processing and characterization of the surimi-like material from mechanically deboned turkey meat Departamento de Ciência dos Alimentos. Lavras: Universidade Federal de Lavras; 2018. p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Meilgaard MC, Carr BT, Civille GV. Sensory evaluation techniques. 4th dition. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ni N, Wang Z, He F, Wang L, Pan H, Li X, et al. Gel properties and molecular forces of lamb myofibrillar protein during heat induction at different pH values. Process Biochem. 2014;49:631–636. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2014.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki H, Nakamura T (2004) Salt treatment of fish pastes and manufacture of fish pastes products using it. In: JP Application (Ed) Japan

- Ochiai Y, Ozawa H. Biochemical and physicochemical characteristics of the major muscle proteins from fish and shellfish. Fish Sci. 2020;86:729–740. doi: 10.1007/s12562-020-01444-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. Surimi seafood: products, market, and manufacturing. In: Park J, editor. Surimi and Surimi Seafood. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis; 2005. pp. 375–433. [Google Scholar]

- Peleg M. The instrumental texture profile analysis revisited. J Text Stud. 2019;50(5):362–368. doi: 10.1111/jtxs.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petcharat T, Benjakul S. Effect of gellan and calcium chloride on properties of surimi gel with low and high setting phenomena. RSC Adv. 2017;7:52423–52434. doi: 10.1039/C7RA10869A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhan K, Huda N, Ahmad R. Effect of number and washing solutions on functional properties of surimi-like material from duck meat. J Food Sci Technol. 2014;51:256–266. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0510-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson TM, Alzaabi AZ, Robertson MD, Fielding BA. Starchy carbohydrates in a healthy diet: the role of the humble potato. Nutrients. 2018;10:1764. doi: 10.3390/nu10111764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson HW, Hogden CG. The biuret reaction in the determination of serum proteins: I. A study of the conditions necessary for the production of a stable color which bears a quantitative relationship to the protein concentration. J Biol Chem. 1940;135:707–725. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)73134-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal AJ. Texture profile analysis–how important are the parameters? J Text Stud. 2010;41:672–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.2010.00248.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Zhao M, Sun W. Effect of pH on the interaction of porcine myofibrillar proteins with pyrazine compounds. Food Chem. 2019;287:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Benjakul S. Effect of serine protease inhibitor from squid ovary on gel properties of surimi from Indian mackerel. J Text Stud. 2017;48:541–554. doi: 10.1111/jtxs.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Benjakul S. Proteolysis and its control using protease inhibitors in fish and fish products: a review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2018;17:496–509. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Benjakul S, Prodpran T. Effect of chitooligosaccharide from squid pen on gel properties of sardine surimi gel and its stability during refrigerated storage. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2019;54:2831–2838. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Prabowo FF, Benjakul S, Pranoto Y, Chantakun K. Combined effect of microbial transglutaminase and ethanolic coconut husk extract on the gel properties and in-vitro digestibility of spotted golden goatfish (Parupeneus heptacanthus) surimi gel. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;109:106107. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XD, Holley RA. Factors influencing gel formation by myofibrillar proteins in muscle foods. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2011;10:33–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00137.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Techaratanakrai B, Nishida M, Igarashi Y, Watanabe M, Okazaki E, Osako K. Effect of setting conditions on mechanical properties of acid-induced Kamaboko gel from squid Todarodes pacificus mantle muscle meat. Fish Sci. 2011;77:439–446. doi: 10.1007/s12562-011-0344-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wijayanti I, Singh A, Benjakul S, Sookchoo P. Textural, sensory, and chemical characteristic of threadfin bream (Nemipterus sp.) surimi gel fortified with bio-calcium from bone of Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer) Foods. 2021;10:96. doi: 10.3390/foods10050976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not shared.

Not applicable.