Abstract

Pyment is a type of mead that is produced from the alcoholic fermentation of a honey solution with the addition of grape juice. Due to the demand for new beverages, pyment can be a profitable alternative for both grape and honey producers. Therefore, this work aimed to characterize the aromatic and physicochemical composition of pyments. The pyments were prepared with addition of 10, 20 and 30% of Moscato juice, and compared with Moscato wine and traditional mead. The results showed an increase in the fermentation rates of Moscato-pyments, indicating that the addition of Moscato juice reverses the low fermentative vigor often reported in mead fermentations. Physicochemical parameters showed an increase in total acidity and a decrease in residual sugar and alcohol, depending on Moscato juice concentration. Moscato-pyments showed an intermediate concentration of volatile compounds between the traditional mead and Moscato wine, with a better balance between fruity, floral and buttery, manifesting characteristic aromas of wines made with Moscato grapes and simultaneously, exposing characteristic aromas of honey. The sensory analysis reveals a significant difference between mead, pyments and Moscato wine. In general, pyments were considered, by the panelists, as the most equilibrated with intermediary aroma intensity, floral, fruity and honey aromas, and good persistence in the mouth.

Keywords: Moscato, Mead, Volatile compounds, Physiochemical characteristics, Sensory analysis

Introduction

Honey is a natural product, consumed and produced on a large scale worldwide (Pires et al. 2013) and has been used since antiquity as a basis in alcoholic beverages production (Iglesias et al. 2014). Mead is defined as an alcoholic beverage produced by the fermentation of a diluted solution of honey, and its ethanol concentration can vary from 4 to 22% (v/v). Mead and its variants are produced and consumed worldwide with many recipes and manufacture suggestions available in digital media. On the other hand, the scientific research available is scarce (Teramoto et al. 2005). Currently, it is considered a drink with progressive economic importance due to the increased demand for fermented products and the need for options for beekeepers (Mendes-Ferreira et al. 2010). Pires et al (2013), when analyzing the global indexes of patent documents associated with mead and related technologies found an important increase in the number of patents since 2011. Moreover, according to the 2015 Annual Report of the Mead Industry (USA), there was an increment of 130% in mead production between 2012 and 2013, and an 84% increase in sales between 2012 and 2014 (Herbert 2015).

There is a wide variety of types of meads classified, among other factors, based on the raw materials used in their preparation, such as spices, herbs, juices, among others. The name "pyment" is used to describe a type of fermented meads with red or white grapes or grape juices. It is expected that the final product will have a different character from the traditional mead with the contribution of honey and grapes in the final sensory characteristics (Vidrih and Hribar 2016). The sensory characteristics and typicity of pyments are determined by the source of honey, the grape variety, and the proportions used to compose the wort.

The highlands of the northeast of Rio Grande do Sul state, known as “Serra Gaúcha”, is responsible for 90% of Brazilian wine production. In this region, the cultivation of vines and the production of wine have a considerable economic and social impact (Welke et al. 2013) and are responsible for important wine tourism (Barbosa et al. 2018). Among the grapes grown in this region, there are the Moscato grape varieties, a complex of aromatic cultivars with a natural ability to produce typical wines characterized by fresh, floral and fruity aromas with balanced acidity (Rizzon et al. 2008). Brazilian Moscato wines are produced with several Moscato varieties (Moscato Branco, Moscato Bianco R2, and Moscato Giallo), with an eventual contribution of other Moscato and Malvasias varieties that determine the typicity of these aromatic wines (Marcon et al. 2019).

Brazil produces approximately 46 tons of honey per year, and Rio Grande do Sul, particularly the “Serra Gaúcha” region, is the most important producer of honey with more than 6.3 tons per year (IBGE 2017). The physical, chemical and organoleptic characteristics of honey depend on the flowering plants foraged by bees, the climatic conditions, bee species, maturation, processing and storage. In this context, most of the honey types commercialized in Brazil are defined as wild, apple, citrus, eucalyptus, canola, or multifloral and produced by small beekeepers and sold within the harvest year (Marquele-Oliveira et al. 2017). Honey is commercialized in Brazil or exported, but small beekeepers face distribution and marketing problems.

In this context, Moscato-pyments represent an option for new products derived from honey and grapes, being a good alternative to provide innovative alcoholic beverages to consumers and increase the profit of beekeeping and winemakers (Iglesias et al. 2014). Based on the possibility of obtaining a product with greater added value and with relatively simple technologies, the aim of this work was to characterize the aromatic and physicochemical composition of Moscato-pyments prepared with different dilutions of honey wort and Moscato juice (Moscato Branco) produced in the highlands of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

Material and methods

Wort and fermentative conditions

The experiments were conducted with a multifloral commercial light honey collected at the end of summer 2019 in the highlands of Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. Honey was characterized based on Brazilian legislation (Normative instruction n°11/2000, 20 October) using the Brazilian official analytical methods and showed: total acidity (23.94 meq/kg), ash content (0.15 g/100 g), solids (0.036 g/100 g), moisture content (17.9%), total sugar (79.8 g/100 g), and assimilable nitrogen (48.2 mg/kg).

The honey-wort was prepared according to Schwarz et al (2020) and the concentration of yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN) was corrected in each treatment by the addition of ammonium phosphate, in order to obtain a fixed final concentration of approximately 150 mg/L of YAN (yeast assimilable nitrogen).

The experiment was carried out by adding 30% (v/v), 20% (v/v) and 10% (v/v) of Moscato grape juice in honey-wort and compared with products obtained by fermenting Moscato and the traditional mead. The filtered grape juice used in this experiment was produced from a blend of Moscato Branco, Moscato Giallo and Moscato Bianco R2 grapes in an approximate ratio of 60:30:20, respectively.

The fermentations were conducted with Saccharomyces cerevisiae Zymaflore Spark (SC, Laffort, France) previously used in studies realized by Schwarz et al (2020). Starter culture was prepared by growing the yeast in YEPD (yeast extract 1%, peptone 1%, and glucose 2%) for 24 h at 28 °C under constant orbital shaking (150 rpm), collected by centrifugation, washed with 0.9% NaCl saline and added to the wort to obtain an initial inoculum of 106 cells/ml. Experiments were conducted in 5 L glass flasks with 4 L of wort, closed with Muller valves and without shaking. The fermentations were performed in the dark, to avoid oxidation, at a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C, a commonly used temperature for wine production, and were monitored daily by weight loss (CO2 release). At the end of the fermentations, physicochemical and volatile compounds analyses were performed.

Physicochemical analysis

Specific gravity and total soluble solids (° Brix) were evaluated directly with a densimeter (Densito®). The pH was determined by the potentiometric method using a pH meter (Digimed®) at 20 °C. Total residual sugars (g/L) and reducing sugars (g/L) were evaluated by the colorimetric method using 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS). Color intensity was evaluated by absorbance at 420 nm using a spectrophotometer (Model 2800, Hitachi, Japan). The alcohol concentration (% v/v) was determined by densitometry after steam distillation of mead samples. Total acidity and volatile acidity (meq/L) were evaluated by titration with 0.1 N sodium hydroxide solution, using phenolphthalein as an indicator, and by steam distillation followed by titration, respectively. Glycerol (g/L) concentration was quantified by an enzymatic assay using the Megazyme® Glycerol kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. The residual yeast assimilable nitrogen, YAN (mg/L) was determined by the formol titration technique and fermentation rate was estimated by the linear regression of the exponential phase of the CO2 weight loss.

Analysis of volatile compounds

The volatile compounds were determined by headspace solid-phase micro-extraction (SPME) with DVB/CAR/PDMS (divinylbenzene/carboxenon polydimethylsiloxane) 50/30 μm fiber, according to Schwarz et al (2020). A gas chromatograph – GC (model 6890, Agilent Technologies, USA), coupled to a mass selective detector (MS) 5973 (Agilent Technologies, USA), with HP-INNOWAX column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) was used for the determination of chemical composition. The MS parameters included electron impact ionization of 70 eV and a mass range of m/z 30–550, using the Selective Ion Monitoring mode (SIM). The software ChemStation (Agilent Technologies) was used for spectra processing. The compounds identification was performed by comparison of the Retention Time and fragmented mass standards with the authentic compounds or with mass spectra in the Wiley database (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA) and NIST Database. Quantification of the compounds was performed by comparing the area of the compound to the area of the internal standard (3-octanol).

Odor activity values (OAV)

The contribution of each volatile compound to the aroma was qualitatively evaluated by its associated descriptor and by its odor activity value (OAV). Values were calculated using the ratio between the concentration of the compound and the threshold of perception reported in the literature (Ribéreau- Gayon et al. 2006; Welke et al. 2014). Only volatile compounds with OAVs > 0.1 were considered to contribute to the aromatic profiles of the meads (Guth 1997) and submitted to principal components analysis (PCA).

Sensory analysis

Sensory analysis of meads, Moscato wine and pyments was carried on by a panel of 12 trained enologists using a 0–9 scale of descriptive attributes (where 0 corresponds to no perception and 9 as high intensity) and general acceptance (0 to 100 scores) adapted from the evaluation sheet proposed by Zanus (2014). Before tasting, panelists participated in two 60-min training sessions to generate and agree upon sensory attributes (Lawless and Heymann 2010). The samples were presented to the panelists blind labeled, with random three-digit codes to avoid bias, at 10 °C, in standard wine-tasting glasses (ISO 3591, 1977), and tasted in triplicate in a randomized order. Panelists were required to wait 20 s between each sample and cleanse their palates with unsalted crackers and water”.

Statistical analysis

The results were analyzed statistically by analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) and Tukey’s test, and the results of the volatile compound above their odor thresholds also were submitted to principal components analysis (PCA). The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistic v22 software and statistical significance was attributed to values of P ≤ 0.05.

Results and discussion

The physicochemical parameters varied depending on the concentration of honey wort and Moscato grape juice, except YAN that was adjusted to approximately 150 mg/L with ammonium phosphate (Table 1). The highest values of specific gravity, soluble solids and sugar content were verified in honey wort, while the lowest values were obtained in Moscato juice. Pyment worts with 10, 20 and 30% Moscato juice exhibited intermediary values, however, these did not differ significantly from those of honey wort. The color intensity of honey wort, determined by absorbance at 420 nm, was significantly higher than Moscato juice and pyment worts, independently of grape juice proportion. Conversely, Moscato juice showed the highest acidity and lowest pH. The addition of Moscato juice contributed to increase wort acidity and decrease pH of pyment worts.

Table 1.

Physicochemical parameters of honey wort, Moscato juice and pyment worts with different concentrations of grape juice

| Parameters | Honey wort | Pyment wort (10%) | Pyment wort (20%) | Pyment wort (30%) | Moscato juice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific gravity | 1.09297a | 1.09283a | 1.09026a | 1.08712a | 1.05972b |

| Soluble solids (°Brix) | 22.23a | 22.20a | 21.63a | 20.93a | 14.67b |

| Total sugars (g/L) | 203.6a | 200.1ab | 198.8b | 199.6ab | 128,5c |

| Color intensity 420 nm | 0.6863a | 0.6120b | 0.5327c | 0.5183c | 0.1617d |

| pH | 3.89a | 3.61b | 3.43bc | 3.41bc | 3.13c |

| Titratable acidity (mEq/L) | 44.02c | 48.67c | 59.33b | 65.53b | 160.14a |

| YAN (mg/L) | 146.95a | 145.74a | 145.15a | 142.56a | 140.44a |

Different letters within each line denote significant differences at p < 0.05 by the Tukey’s test

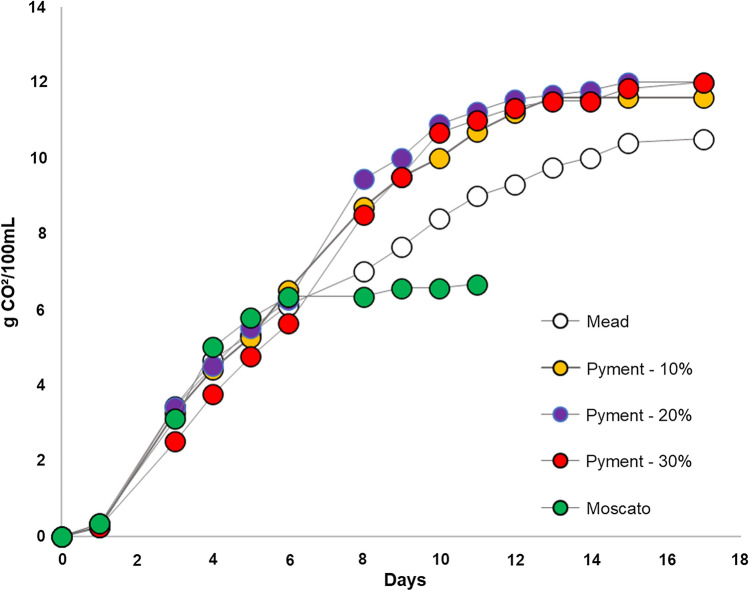

The fermentation kinetics determined by CO2 release (Fig. 1) showed that as expected, based on the lower sugar content of Moscato juice (Table 1), Moscato wines finished fermentation after 6 days with a total carbon dioxide release of 6.4 g/100 mL. Conversely, mead (honey wort) finished fermentation after 16 days with a total CO2 release of 10.5 g/100 mL. Moscato-pyments, independently of grape juice concentration (10 to 30%) exhibited very similar fermentative behaviors, finishing the fermentations with 11.5 to 12 g/100 mL of CO2 after 13 days. Fermentation kinetics (g CO2/L/Day) during the exponential phase differed significantly 0.56 to 1.25 g CO2/100 mL/day for mead and Moscato wine, respectively, and with intermediary values for different honey wort/Moscato juice mixtures (Table 2). Most fermentation problems in mead are considered to be due to a deficiency of nitrogen, minerals and other growth factors (Schwarz et al. 2021). As a way to correct problems related to fermentative vigor, yeast strains with low nitrogen demand (Schwarz et al. 2020), or the addition of inorganic compounds (Schwarz et al. 2021) or fruit juices (Gupta and Sharma 2009) have been used to stimulate fermentation and improve the mead production process.

Fig. 1.

Fermentation kinetics of mead, Moscato wine, and pyments with 10, 20, and 30% Moscato juice. Values are mean of three replications

Table 2.

Physicochemical parameters of mead, Moscato wine and pyments with 10, 20, and 30% Moscato juice (mean ± standard deviation)

| Mead | Pyment 10% | Pyment 20% | Pyment 30% | Moscato wine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific gravity | 1.007 ± 0.001a | 1.0035 ± 0.0023b | 1.0002 ± 0.0006c | 0.9993 ± 0.0005c | 0.9949 ± 0.0001d |

| pH | 3.48 ± 0.07a | 3.41 ± 0.01a | 3.42 ± 0.02a | 3.24 ± 0.03b | 3.28 ± 0.06b |

| Color intensity (420 nm) | 0.30 ± 0.05a | 0.13 ± 0.02b | 0.12 ± 0.01b | 0.11 ± 0.03bc | 0.03 ± 0c |

| YAN (mg/L) | 31.27 ± 2.71ab | 23.45 ± 4.69b | 26.58 ± 5.42ab | 42.21 ± 12.41a | 31.27 ± 2.71ab |

| Reducing sugars (g/L) | 41.33 ± 1.69a | 35.21 ± 4.75a | 25.63 ± 1.19b | 19.04 ± 2.27b | 1.12 ± 0.10c |

| Total residual sugars (g/L) | 49.37 ± 2.94a | 42.87 ± 4.15a | 33.2 ± 0.63b | 25.44 ± 1.85c | 2.06 ± 0.27d |

| Titratable acidity (mEq/L) | 59.33 ± 1.15c | 58.07 ± 3.46c | 76.10 ± 8.72b | 81.33 ± 1.15b | 152.21 ± 2a |

| Volatile acidity (mEq/L) | 12.33 ± 0.58a | 11.67 ± 2.08a | 11.01 ± 1.00a | 12.00 ± 0a | 6.02 ± 0b |

| Ethanol (% v/v) | 11.53 ± 0.12a | 12.20 ± 0.35a | 11.9 ± 0.26a | 11.53 ± 0.31a | 8.27 ± 0.12b |

| Fermentation rate (g CO2/100 mL/day) | 0.56 ± 0,04c | 1.08 ± 0.02b | 1.11 ± 0.05b | 1.11 ± 0.02b | 1.25 ± 0.01a |

| Glycerol (g/L) | 6.18 ± 0.20a | 5.65 ± 0.68a | 5.80 ± 0.37a | 5.75 ± 0.28a | 5.39 ± 0.31a |

| Glycerol/etanol ratio | 0.54 ± 0.01b | 0.46 ± 0.07b | 0.49 ± 0.04b | 0.50 ± 0.03b | 0.65 ± 0.04a |

Different letters within each line denote significant differences at p < 0.05 by the Tukey’s test

Physicochemical analysis showed an inverse relation between grape juice proportion and the final density with a correlation of 0.90. Moreover, the highest the honey concentration in pyment worts, the highest the total and reducing sugar concentration in final meads or pyments (Table 2). According to Pereira et al (2014), 40 g/L of residual sugar in meads has already been described and is a result of non-fermentable sugars usually found in honey, such as trehalose, isomaltose and melezitose.

Color intensity (OD420), an important sensory factor, significantly decreased with the addition of Moscato juice, varying between 0.3 (yellow) and 0.03 (pale yellow) units (Table 2). Similarly, titratable acidity showed an indirect relation with the addition of Moscato juice, but all of them were relatively low. The increase in titratable acidity can be considered advantageous because it has a positive sensory effect, especially when associated with the presence of residual sugar and high ethanol, bringing greater balance in the mouth (Noordeloos and Nagel 1972). In the case of mead, the higher acidity can reduce the sweet sensation resulting from the high concentration of residual sugars.

As expected, based on the sugar content of worts, ethanol concentration varied depending on the Moscato juice concentration. The lower values were obtained with Moscato juice, while non-significant differences were evidenced between the different concentrations of honey wort vs. Moscato juice (Table 2). On the other hand, there were no significant differences in the amount of glycerol (g/L) between the treatments, ranging from 6.18 g/L in the traditional mead and 5.39 g/L in the Moscato wine, with intermediate values in the pyments. The production of glycerol is desirable to obtain good quality meads since its presence gives greater fullness and smoothness in the mouth (Gomes et al. 2015). The observed glycerol content is within the concentrations commonly found in white wines (Ribéreau-Gayon et al. 2006).

Volatile acidity varied among treatments, with higher concentrations depending on honey wort relative concentration (Table 1). However, the ethanol/volatile acidity ratio did not differ between treatments. In the same sense, glycerol concentration did not vary between treatments but was indirectly related to ethanol concentration (Table 1).

The concentration of 32 compounds, including alcohols, esters, fatty acids, terpenes and other volatile compounds, were identified by GC/MS in mead, pyments, and Moscato wine (Table 3). To characterize the aromatic composition, the sum of acetate esters, ethyl esters, terpenes and higher alcohols, the individual production of each identified volatile compound and the values of odor activity (OAV) were considered.

Table 3.

Concentration of volatile compounds (mg/L) in mead, pyments and Moscato wine

| Compounds* | Mead | Pyment 10% | Pyment 20% | Pyment 30% | Moscato wine | Odor threshold** | Retention Times (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols | 120.31 ± 7.68b | 105.05 ± 3.08b | 81.8 ± 4.15b | 111.52 ± 8.65b | 312.85 ± 41.01a | ||

| 1-propanol | 3.23 ± 0.57bc | 2.66 ± 0.22c | 2.26 ± 0.31c | 5.06 ± 0.15b | 8.59 ± 1.55a | 500 | 5.42 |

| 1-propanol, 2-methyl | 2.55 ± 0.62b | 2.57 ± 0.48b | 2.68 ± 0.78b | 3.53 ± 0.26b | 14.45 ± 5.01a | 75 | 7.20 |

| 1-butanol, 3-methyl | 75.67 ± 7.16bc | 58 ± 1.54cd | 51.97 ± 1.4d | 87.52 ± 6.97b | 166.26 ± 12.22a | 300 | 11.52 |

| 1-pentanol, 3-methyl | 0.12 ± 0.02a | 0.15 ± 0.04a | 0.21 ± 0.05a | 0.20 ± 0a | 0.23 ± 0.2a | 1 | 15.94 |

| 2-phenilethanol | 38.35 ± 0.78b | 40.93 ± 3.66b | 23.88 ± 4.52b | 13.78 ± 2.13b | 119.11 ± 27.12a | 7.5 | 37.76 |

| 1-hexanol | 0.05 ± 0.02b | 0.41 ± 0.24b | 0.57 ± 0.14b | 1.16 ± 0.19b | 2.99 ± 1.01a | 8 | 17.49 |

| 1-octanol | 0.18 ± 0.03a | 0 ± 0b | 0 ± 0b | 0 ± 0b | 0.16 ± 0.14ab | 0.9 | 24.96 |

| 1-dodecanol | 0.15 ± 0.03a | 0.33 ± 0.01a | 0.24 ± 0.12a | 0.27 ± 0.23a | 1.07 ± 0.78a | 1 | 32.25 |

| Volatile fatty acids | 113.13 ± 15.11a | 60.43 ± 8.3b | 73.79 ± 9.48b | 73.8 ± 8.49b | 50.74 ± 1.41b | ||

| hexanoic acid | 8.88 ± 0.77a | 6.16 ± 1.07bc | 5 ± 0.04c | 5.45 ± 1.44bc | 7.36 ± 0ab | 0.42 | 35.93 |

| octanoic acid | 70.88 ± 12.67a | 36.34 ± 7.07b | 51.04 ± 9.03ab | 44.46 ± 7.24b | 32.48 ± 1.2b | 0.5 | 42.56 |

| n-decanoic acid | 33.1 ± 2.27a | 16.84 ± 2.09b | 16.83 ± 0.62b | 23.22 ± 5.3b | 8.69 ± 1.62c | 10 | 48.94 |

| dodecanoic acid | 0.27 ± 0.1b | 1.08 ± 0.03ab | 0.92 ± 0.06b | 0.67 ± 0.84b | 2.21 ± 0.49a | 1 | 52.90 |

| Acetate esters | 34.87 ± 1.26b | 25.13 ± 0.69b | 30.19 ± 3.37b | 35.96 ± 2.82b | 135.53 ± 15.79a | ||

| isoamyl acetate | 4.82 ± 0.8b | 4.06 ± 0.74b | 5.57 ± 0.82b | 7.79 ± 1.06ab | 12.21 ± 3.66a | 0.26 | 8.13 |

| hexyl acetate | 0 ± 0b | 0.03 ± 0.03b | 0.22 ± 0b | 0.60 ± 0b | 2.83 ± 0.53a | 0.67 | 13.21 |

| 2-phenylethyl acetate | 10.5 ± 2.1b | 7.42 ± 1.24b | 6.79 ± 2.11b | 5.84 ± 1.97b | 67.56 ± 17.09a | 0.25 | 34.10 |

| ethyl acetate | 19.54 ± 3.17b | 13.61 ± 1.4c | 17.61 ± 1.85bc | 21.73 ± 1.35b | 52.92 ± 0.58a | 160 | 2.78 |

| Ethyl esters | 179.46 ± 19.01a | 55.81 ± 5.36b | 36.06 ± 5.89b | 52.63 ± 10.6b | 45.76 ± 13.12b | ||

| ethyl hexanoate | 5.45 ± 0.94a | 2.6 ± 1.15b | 1.56 ± 0.18b | 2.14 ± 0.14b | 6.81 ± 0.58a | 0.08 | 11.56 |

| ethyl octanoate | 55.62 ± 9.65a | 14.98 ± 3.37bbc | 14.24 ± 2.28bc | 20.26 ± 2.27b | 5.82 ± 0.29c | 0.58 | 19.95 |

| ethyl decanoate | 105.88 ± 8.04a | 29.87 ± 2.13b | 17.57 ± 5.02b | 24.75 ± 11bb | 21.43 ± 15.59b | 0.4 | 28.00 |

| ethyl dodecanoate | 10.18 ± 0.96a | 7.46 ± 0.34ab | 2.13 ± 0.58c | 4.58 ± 0.02bc | 9.42 ± 2.61a | 1.5 | 35.40 |

| ethyl phenylacetate | 0.16 ± 0.02a | 0.11 ± 0.02a | 0.16 ± 0.03a | 0.12 ± 0.03a | 0.09 ± 0.08a | 0.65 | 33.11 |

| ethyl 9-decenoate | 1.66 ± 0.09a | 0.55 ± 0.07b | 0.24 ± 0.02b | 0.61 ± 0.1b | 2.04 ± 0.76a | 0.1 | 29.84 |

| Terpenoids | 1.98 ± 0.15d | 3.54 ± 0.29cd | 5.22 ± 0.4bc | 6.65 ± 0.51b | 31.33 ± 1.63a | ||

| linalool | 0.83 ± 0d | 1.39 ± 0.34d | 2.14 ± 0.18c | 3.07 ± 0.32b | 10.63 ± 0a | 0.05 | 24.69 |

| hotrienol | 0.96 ± 0.06c | 1.21 ± 0.14c | 1.71 ± 0.08b | 1.6 ± 0.26b | 6.51 ± 0a | 0.11 | 27.12 |

| citronellol | 0.19 ± 0.08b | 0.27 ± 0.06b | 0.38 ± 0.07b | 0.39 ± 0.1b | 2.23 ± 0.57a | 0.4 | 32.84 |

| alpha-terpineol | 0 ± 0d | 0.43 ± 0.07c | 0.67 ± 0.15c | 1.08 ± 0.12b | 4.95 ± 0a | 0.4 | 30.14 |

| limonene | 0 ± 0b | 0.07 ± 0.03b | 0.03 ± 0.01b | 0.06 ± 0.04b | 0.38 ± 0.14a | 0.02 | 9.40 |

| geraniol | 0 ± 0b | 0.1 ± 0b | 0.14 ± 0.03b | 0.38 ± 0.04b | 4.43 ± 1.74a | 0.03 | 22.80 |

| cosmene | 0 ± 0b | 0.07 ± 0.01b | 0.14 ± 0.04b | 0.07 ± 0.04b | 2.22 ± 0.23a | - | 19.16 |

| Other volatile compounds | |||||||

| acetaldehyde | 1.44 ± 0.09b | 0.4 ± 0.16b | 0.69 ± 0.09b | 1.29 ± 0.21b | 5.28 ± 2.08a | 0.5 | 1.70 |

| Diethyl succinate | 0 ± 0a | 0.14 ± 0.05a | 0.13 ± 0.03a | 0.09 ± 0.02a | 0.39 ± 0.43a | 200 | 29.38 |

| Vinil guaiacol | 0.27 ± 0.04a | 0.2 ± 0.01a | 0.28 ± 0.01a | 0.25 ± 0.08a | 1.18 ± 0.86a | 1.146 | 46.79 |

Volatile compounds such as higher alcohols, fatty acids and esters are important quality parameters and sensory indicators for alcoholic beverages (Saénz-Navajas et al. 2013).

Higher alcohols provide aromas of almond cream and fusel alcohol (Catania and Avagnina 2010), and in low concentration can contribute favorably to the wine bouquet (Ebeler and Thorngate 2009). However, concentrations above 400 mg/L are considered a negative factor in wine quality (Garde-Cerdán and Ancín-Azpilicueta 2008). In general, Moscato wines exhibited a higher concentration of higher alcohols, particularly 2-methyl-1-propanol, 3-methyl-1-butanol, 2-phenylethanol, and 1-hexanol, compared with mead and Moscato-pyments (Table 3). The lower concentration of higher alcohols in mead and pyments can be attributed to the low presence of free amino acids in honey wort since higher alcohols are produced by yeasts from amino acids by the Ehrlich reaction (Ribéreau-Gayon et al. 2006). In grape must, the amino acid concentration can vary between 1000 and 4000 mg/L (Ribéreau-Gayon et al. 2006), whereas the amount of free amino acids in honey rarely exceeds 300 mg/L (Heremosin et al. 2003). Moreover, the main amino acid in honey (50% and 85% of the total free amino acids) is proline, which is used by yeast for protein synthesis, but it is not catabolized by the Ehrlich reaction (Pires et al. 2014). Moreover, as expected, the concentration of higher alcohols was accompanied by variations of their acetic esters, like isoamyl acetate and phenylethyl acetate, a group of compounds with an interesting fruity aroma.

Conversely, mead and Moscato-pyments showed higher concentrations of volatile fatty acids, as hexanoic, octanoic and n-decanoic acids, as well as their ethyl esters, compared with Moscato wine (Table 3). Volatile fatty acids are produced by the fatty-acid pathway of yeasts during fermentation (Duan et al. 2015), and their ethyl esters are the result of spontaneous ethanolysis in alcoholic beverages (Diaz-Maroto et al. 2005). Volatile acids are described as unpleasant aromas “fatty, rancid, and cheese”, while their ethyl esters are considered as important positive compounds with “fruity, pear, banana, apple, and floral” descriptors (Duan et al. 2015). Moreover, high amounts of medium-chain fatty acids in mead worts are believed to inhibit alcoholic fermentation (Sroka and Tuszynski 2007).

The highest concentration of terpenoids was found in Moscato wine (31.33 mg/L) and the lowest concentration in mead (1.98 mg/L). Terpenoids in pyments varied between 3.54 mg/L and 6.65 mg/L, increasing depending on the percentage of Moscato juice in the treatments. Thus, the addition of Moscato juice provides floral characteristics to the pyments, improving the sensory quality of these fermentation products. Linalool and hotrienol were the terpenes with the highest values in all treatments, but there were no significant differences between mead and pyment with 10% Moscato. α-terpineol, limonene, geraniol and cosmene were not evidenced in mead, suggesting that their presence is due to the addition of Moscato juice. The most characteristic aromatic compounds of the Moscato varieties belong to the chemical family of terpenes (Ribéreau-Gayon et al. 2006; Marcon et al. 2019). Linalol, geraniol, nerol, citronellol and α-terpineol are found in many floral wines, such as Moscato and Malvasia (Ribéreau-Gayon et al. 2006; Marcon et al. 2019). On the other hand, in honey the volatile organic compounds, including terpenes, are present in low concentrations and depend on the botanical origin of the honey (Jerković and Kuś 2014).

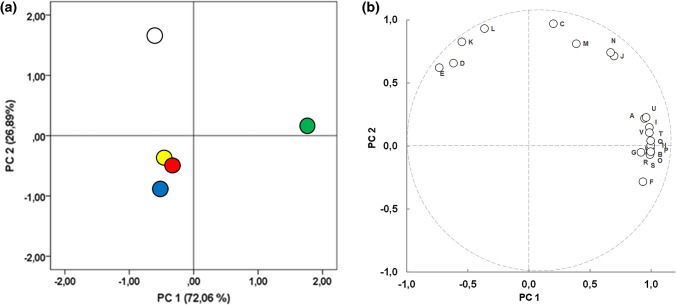

Odor activity values (OAVs) were determined and the average of only 22 compounds with an OAV > 1 were analyzed using multivariate principal component analysis (Fig. 2). In addition, the OAVs for the compounds that exhibited the same aromatic descriptor were grouped and only five aromas were established, namely floral, fruity, rancid, citrus, pungent and clove, with the floral, fruity and rancid aromatic descriptors being those that contributed more striking for the aromatic profile of the mead, Moscato wine, and pyments.

Fig. 2.

Principal component analysis (PC) based on OAV indexes (> 1) of volatile compounds a of mead (circle), pyments with 10% (yellow circle), 20% (blue circle) and 30% of Moscato juice (red circle), and Moscato wine (green circle), and b contribution of the variables for PCA scores: 2-phenilethanol (A); 1-dodecanol (B); hexanoic acid (C); octanoic acid (D); decanoic acid (E); dodecanoic acid (F); isoamyl acetate (G); hexyl acetate (H); phenylethyl acetate (I); ethyl hexanoate (J); ethyl octanoate (K); ethyl decanoate (L); ethyl dodecanoate (M); ethyl 9-decenoate (N); linalool (O); hotrienol (P); citronellol (Q); α-terpineol (R); limonene (S); geraniol (T); acetaldehyde (U) e vinil guaiacol (V) (Color figure online)

The first two components (95.97% of variance) of the multivariate analysis allowed the separation of three groups: (a) mead (without the addition of grape juice); (b) pyments with 10%, 20% and 30% of Moscato juice; and (c) Moscato wine. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the pyments showed complementary aromatic characteristics between mead and Moscato wine.

The first component (72.06%) separated Moscato wine from the pyments and the traditional mead. The compounds that most contributed to this separation were 2-phenylethanol, 1-dodecanol, dodecanoic acid, isoamyl acetate, hexyl acetate, phenylethyl acetate, terpenes (linalool, hotrienol, citronellol, terpineol, limonene and geraniol), acetaldehyde and vinyl guaiacol, for which the Moscato wine showed higher concentrations. Conversely, meads and pyments showed higher concentrations of decanoic acid. In general, pyments exhibited a better balance of aromatic compounds including both mead and Moscato wine typical compounds in lower concentrations. Grouping aromatic descriptors, muscat wine exhibited the highest amounts of compounds (OAV > 1) with the floral aroma, which can be attributed to phenylethyl acetate and linalool.

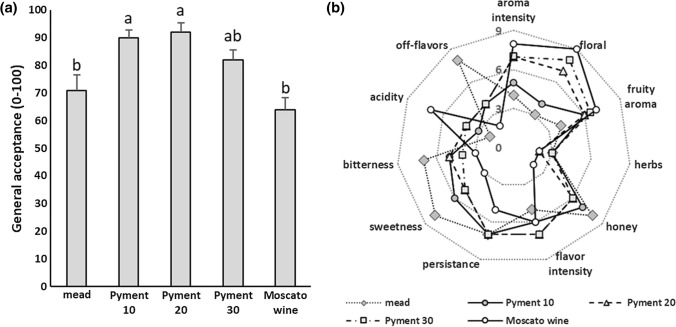

The sensory analysis reveals significant differences for general acceptance of mead, pyments and Moscato wine. As can be observed in Fig. 3a, mead and Moscato wine obtained lower scores than pyments, particularly those with 10 and 20% Moscato juice. The highest acceptance of pyments can be associated to the high content of off-flavor (described as rancid and reduced by panelists), bitterness and sweetness of mead, the low alcohol content and the high acidity of Moscato wine. In general, pyments were considered as most equilibrated with intermediary aroma intensity, floral, fruity and honey aromas, and good persistence in the mouth (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Sensory evaluation of mead, pyments and Moscato wine. a olfactory and flavor sensory attributes, and b general acceptance. Data are mean values, and different letters represent significant differences at p < 0.05 by the Tukey’s test

Conclusion

This is the first paper describing Moscato-pyments, an innovative fermenting beverage produced by a mixture of honey wort and Moscato juice. This report showed the fermentative behavior, as well as the peculiar aromatic and sensory characteristics of Moscato-pyments (10–30% Moscato juice). The chemical analysis and sensory evaluation of Moscato-pyments point to them as new innovative beverages that associate the aromatic characteristics of Moscato grapes (acidy taste and fruity/floral aromas) and meads (sweetness taste and honey aroma). Our results showed that Moscato-pyments are a highly appreciated beverage with complex and equilibrated aromas and taste, and can be an alternative product for both beekeepers and winemakers.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development-CNPq (Universal- 431538/2016-6), the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior (CAPES, finance code 001), and the University of Caxias do Sul, Brazil. Moreover, we thank the Cooperativa Vinícola Garibaldi for kindly provided Moscato juice, and the enologists that participated in the sensory panel.

Authors' contributions

LVS, ARM, APLD and SE conceived and planned the experiments, and carried out the experiments. FA and SMS performed the Analysis of volatile compounds. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript and provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development-CNPq (Universal- 431538/2016–6), the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior (CAPES, finance code 001), and the University of Caxias do Sul, Brazil.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Luisa Vivian Schwarz, upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could cause conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Barbosa FS, Scavarda AJ, Sellitto MA, Marques DIL. Sustainability in the winemaking industry: An analysis of Southern Brazilian companies based on a literature review. J Clean Prod. 2018;192:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catania CD, e Avagnina S (2010) La interpretación sensorial del vino. INTA

- Diaz-Maroto MC, Schneider R, Baumes R. Formation pathways of ethyl esters of branched short-chain fatty acids during wine aging. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:3503–3509. doi: 10.1021/jf048157o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan LL, Shi Y, Jiang R, Yang Q, Wang TQ, Liu PT, Duan CQ, Yan GL. Effects of adding unsaturated fatty acids on fatty acid composition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and major volatile compounds in wine. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2015;36:285–295. [Google Scholar]

- Ebeler SE, Thorngate JH. Wine chemistry and flavor: looking into the crystal glass. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:8098–8108. doi: 10.1021/jf9000555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garde-Cerdán T, Ancín-Azpilicueta C. Effect of the addition of different quantities of amino acids to nitrogen-deficient must on the formation of esters, alcohols, and acids during wine alcoholic fermentation. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2008;41:501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2007.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes T, Dias T, Cadavez V, Verdial J, Morais JS, Ramalhosa E, Estevinho LM. Influence of sweetness and ethanol content on mead acceptability. Pol J Food Nutr Sci. 2015;65:137–142. doi: 10.1515/pjfns-2015-0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta JK, Sharma R. Production technology and quality characteristics of mead and fruit-honey wines: a review. NOPR. 2009;8:345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Guth H. Identification of character impact odorants of different white varieties. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45:3022–3026. doi: 10.1021/jf9608433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert J (2015) American Mead Maker’s 2nd annual mead industry report. American mead maker. http://issuu.com/americanmead/docs/amma_15.1. Accessed 08 Jul 2021

- Hermośin I, Chicon RM, Cabezudo MD (2003) Free amino acid composition and botanical origin of honey. Food Chem 83:263–268. 10.1016/s0308-8146(03)00089-x

- IBGE. Sistema IBGE de Recuperação Automática - SIDRA. Censo agropecuário 2017: Tabela 50.6622 - Número de estabelecimentos agropecuários com apicultura, quantidade de mel e cera de abelha vendidos e total de caixas de abelha - resultados preliminares. https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/censo-agropecuario/censo-agropecuario-2017. Accessed 08 Jul 2021

- Iglesias A, Pascoal A, Choupina AB, Carvalho CA, Fea´s X, Estevinho LM, Developments in the fermentation process and quality improvement strategies for mead production. Molecules. 2014;19:12577–12590. doi: 10.3390/molecules190812577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerković I, Kuś PM. Terpenes in honey: occurrence, origin and their role as chemical biomarkers. RSC Adv. 2014;4:31710–31728. doi: 10.1039/C4RA04791E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawless HT, Heymann H (2010) Sensory evaluation of food: principles and practices, 2nd edn. Springer Science & Business, New York NY. 10.1007/978-1-4419-6488-5

- Marcon AR, Schwarz LV, Dutra SV, Delamare APL, Gottardi F, Parpinello GP, Echeverrigaray S. Chemical composition and sensory evaluation of wines produced with different Moscato varieties. BIO Web Conf. 2019;12:02033. doi: 10.1051/bioconf/20191202033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marquele-Oliveira F, Carrão DB, De Souza RO, Baptista NU, Nascimento AP, Torres EC, Moreno GP, Buszinski AFM, Miguel FG, Cuba GL, dos Reis F, Lambertucci J, Redher C, Berretta AA (2017) Fundamentals of Brazilian honey analysis: an overview. In: de Toledo VAA (ed) Honey analysis, Chapter 7. Intershoper, pp 139–170. 10.5772/67279

- Mendes-Ferreira A, Cosme F, Barbosa C, Falco V, Inês A, Mendes-Faia A. Optimization of honey-must preparation and alcoholic fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae for mead production. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;144:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordeloos S, Nagel CW. Effect of sugar on acid perception in wine. Am J Enol Vitic. 1972;23:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AP, Mendes-Ferreira A, Oliveira JM, Estevinho LM, Mendes-Faia A. Effect of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells immobilisation on mead production. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2014;56:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pires EA, Ferreira MA, da Silva SMPC, Santos FL. Estudo prospectivo do hidromel sob o enfoque de documento de patentes. Geintec. 2013;3:033–041. doi: 10.47059/geintecmagazine.v3i5.286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pires EJ, Teixeira JA, Brányik T, Vicente AA. Yeast: the soul of beer’s aroma—a review of flavour-active esters and higher alcohols produced by the brewing yeast. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:1937–1949. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribéreau-Gayon P, Dubourdieu D, Done`che B, Lonvaud A (2006) Handbook of enology, vol 1: the microbiology of wine and vinifications. Wiley, Hoboken

- Rizzon LA, Salvado MBA, Miele A. Teores de cátions dos vinhos da Serra Gaúcha. Ciênc Tecnol Alimen. 2008;28:635–641. doi: 10.1590/S0101-20612008000300020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saénz-Navajas MP, Ballester J, Pêcher C, Peyron D, Valentin D. Sensory drivers of intrinsic quality of red wines: Effect of culture and level of expertise. Food Res Int. 2013;54:1506–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.09.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz LV, Marcon AR, Delamare APL, Agostini F, Moura S, Echeverrigaray S. Selection of low nitrogen demand yeast strains and their impact on the physicochemical and volatile composition of mead. J Food Sci Technol. 2020;57:2840–2851. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04316-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz LV, Marcon AR, Delamare APL, Echeverrigaray S. Influence of nitrogen, minerals and vitamins supplementation on honey wine production using response surface methodology. J Apic Res. 2021;60(1):57–66. doi: 10.1080/00218839.2020.1793277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sroka P, Tuszynski T. Changes in organic acid contents during mead wort fermentation. Food Chem. 2007;104:1250–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.01.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto Y, Sato R, Ueda S. Characteristics of fermentation yeast isolated from traditional Ethiopian honey wine, ogol. Afr J Biotechnol. 2005;4:160–163. doi: 10.5897/AJB2005.000-3032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vidrih R, Hribar J (2016) Mead: the oldest alcoholic beverage. In: Kristbergsson K, Oliveira J (eds) Traditional foods. Integrating Food science and engineering knowledge into the food chain, vol 10. Springer, Boston, pp 325–338. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-7648-2_26

- Welke JE, Manfroi V, Zanus M, Lazzarotto M, Zini CA. Differentiation of wines according to grape variety using multivariate analysis of comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography with time-of-flight mass spectrometric detection data. Food Chem. 2013;141:3897–3905. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welke JE, Zanus M, Lazzarotto M, Zini CA. Quantitative analysis of headspace volatile compounds using comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography and their contribution to the aroma of Chardonnay wine. Food Res Int. 2014;59:85–99. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zanus MC (2014) Espumante Moscatel – o sabor certo para sua sobremesa. http://www.cnpuv.embrapa.br/publica/artigos/moscatel.html. Accessed 08 Jul 2021

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Luisa Vivian Schwarz, upon request.