Abstract

Purpose

To report our experience with a case of a very atypical clinical onset of multiple sclerosis in a young boy during a COVID-19 infection.

Case report

A 16-year-old boy was referred to our ophthalmology clinic with a complete isolated bilateral horizontal gaze palsy. The condition had onset suddenly 2 weeks prior and he had no associated symptoms, as well as no significant medical history. His corrected visual acuity was 0.0 logMAR in both eyes. While hospitalized, he was found infected with COVID-19. Subsequent brain MRI showed multiple lesions typical of a yet undiagnosed MS, as well as an active pontine plaque which was highly probable the cause of the horizontal gaze palsy. High-dose steroid treatment was initiated 1 week later, after the patient exhibited negative COVID-19 test results.

Conclusion

Clinical manifestations of MS are rarely seen in male teenagers and only a few cases of isolated bilateral horizontal gaze palsy have been reported as the initial manifestation, but never during concomitant COVID-19 infection. We presume that the presence of COVID-19 may have been a neuroinflammatory trigger of underlying MS.

Keywords: COVID-19, pediatric Neuro-Ophthalmology, atypical multiple sclerosis, horizontal Gaze Palsy

Introduction

Optic neuritis is the most common ocular manifestation of multiple sclerosis (MS), occurring at the clinical onset of disease in up to 30% of cases. Ocular motility disorders are rarely the initial manifestation of MS (5–8% of cases); internuclear ophthalmoplegia is the most frequent of these disorders. 1 At present, there is no clear evidence for a relationship between coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and MS (or other demyelinating diseases), although coronavirus RNA sequences have been detected in the cerebrospinal fluid and active demyelinating plaques of several patients with MS.2,4 (Cristallo et al. 1997, Murray 1992 Ann Neurol). In this report, we describe an unusual case of sudden bilateral horizontal gaze palsy in a young boy, which was subsequently identified as the clinical onset of juvenile MS in a patient with COVID-19.

Case description

A 16-year-old boy was referred to our ophthalmology clinic with the complaint of severe difficulty in lateral eye movement. The condition had onset suddenly 2 weeks prior, without any associated symptoms. He was in good overall health with no significant medical history, and had received no treatment during the previous year. Complete bilateral horizontal gaze palsy was evident during our first evaluation; normal vertical ocular motility and full convergence/divergence capacity were present. The patient did not complain of diplopia in primary position of gaze and his corrected visual acuity was 0.0 logMAR in both eyes; complete ocular examination findings were unremarkable except for motility impairment.

The patient was hospitalized in our pediatric care unit; a standard nasopharyngeal swab demonstrated infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-coronavirus (CoV)-2. The patient was immediately admitted to the isolation ward; viral infection was confirmed by nasopharyngeal swab findings 48 h later. Blood analysis revealed the presence of high titre anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies, while IgM antibodies were already negative.

The patient was not vaccinated because at the time of the ocular complaints (late 2020) there were no vaccines available.

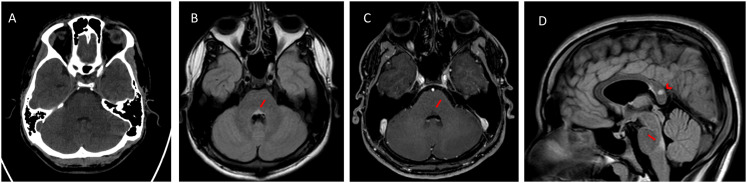

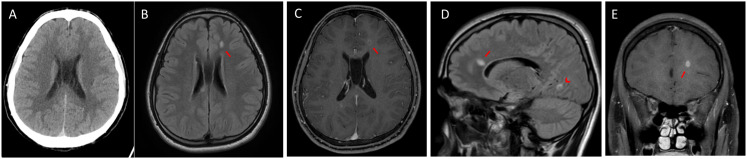

Cerebral computed tomography scan findings on admission were unremarkable (Figures 1A and 2A). Subsequent brain magnetic resonance imaging showed multiple small ovoidal white matter lesions with perivenular plaque distribution typical of MS, particularly at the callososeptal interface (Figure 1B–E, arrow). Other findings included propagation along the medullary venules and perpendicular to the lateral ventricles, in a triangular configuration (i.e. Dawson's fingers) involving the corpus callosum (Figure 1E, arrowhead) and juxtacortical (Figure 2D) and periventricular white matter. Some plaques showed rings of contrast enhancement suggestive of activity; these were initially faint (Figure 1C) and more pronounced in the late-enhancement phase (Figure 1E). The lesions were distributed in multiple regions of the brain (Figures 1D and 2D, arrowhead) and occurred at different times (according to the enhancement findings). Thus, the patient was diagnosed with MS in accordance with the 2017 revised McDonald's criteria. The MS plaque responsible for horizontal gaze palsy was not visible on axial computed tomography at the level of the posterior pontine tegmentum (Figure 2A), but was evident on magnetic resonance imaging, particularly on axial T2-weighted fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images (Figure 2B) and sagittal FLAIR images (Figure 2D, arrow). The plaque did not demonstrate any enhancement (Figure 2C). The patient did not subsequently develop any symptoms of COVID-19, but persistent positive COVID-19 test results delayed the initiation of high-dose intravenous steroids currently recommended as first-line treatment for juvenile MS. The active presence of Coronavirus in our patient determined a therapy decision as high-dose steroid treatment generally carries a higher risk of infection. So, intravenous high-dose steroid treatment was initiated 1 week later when SARS-CoV-2 PCR nasopharyngeal swabs became negative. He was treated using a modified Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial protocol (i.e. 500 × 2 mg intravenous methylprednisolone, daily for 5 days without oral tapering). After 4 weeks of hospitalization, the patient exhibited partial ocular motility improvement; full ocular motility was evident 2 weeks later. The patient was then discharged with a diagnosis of juvenile MS and COVID-19 remission.

Figure 2.

A) Axial computed tomography on hospital admission, at the level of the posterior pontine tegmentum lesion, showing unremarkable findings. B) Axial FLAIR image showing a hyperintense lesion, which was responsible for horizontal gaze palsy. C) Axial T1-weighted image obtained after gadolinium administration showing no lesion enhancement. D) Sagittal FLAIR image showing the vertical extent of the lesion in the posterior pontine tegmentum (arrow); another MS lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum was noted as an incidental finding (arrowhead).

Figure 1.

A) Axial computed tomography on admission, at the level of the anterior callososeptal interface, showing unremarkable findings. B) Axial FLAIR image showing a typical hyperintense lesion in the callososeptal interface. C) Axial T1-weighted image obtained after gadolinium administration showing slight enhancement of the lesion in the early phase. D) Sagittal FLAIR image showing that the lesion had propagated along the medullary venules and was perpendicular to the lateral ventricles in a triangular configuration (i.e. Dawson's fingers; arrow); another MS lesion of the occipito-mesial juxtacortical white matter was noted as an incidental finding (arrowhead). E) Coronal T1-weighted image obtained after gadolinium administration showing more pronounced enhancement of the lesion in the late phase.

The legal guardian of the patient's signed written informed consent to authorize the publication of clinical records and data included in this case report; you can observe the ocular motility limitations of the young boy at onset and after resolution in the video section herein enclosed.

Discussion

This case is important for several reasons. First, clinical manifestations of MS are rarely seen in teenagers, particularly males. Second, to our knowledge, isolated bilateral horizontal gaze palsy has only occasionally been reported as the initial manifestation of juvenile MS.4,5 Third, our patient exhibited concomitant COVID-19 at the clinical onset of demyelination. Thus, we presume that the presence of COVID-19 may have been a neuroinflammatory trigger of underlying MS. This could be related to the marked neurotropism of SARS-CoV-2, which may cause anosmia, ageusia, headache, dizziness, acute Guillain-Barre or Miller Fisher syndromes (with diplopia and ophthalmoplegia), internuclear ophthalmoplegia, viral meningitis, post-infectious acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, or acute cerebrovascular disease. SARS-CoV-2 can directly enter the brain after inhalation via the cribriform plate and olfactory bulb; the virus may then affect sensitive motor nerves. 6 We suspect that it contributed to bilateral horizontal gaze palsy in our patient. We have also observed an outbreak of bilateral blepharospasm as a delayed neurological manifestation of COVID-19. 7

Notably, the onset of MS in our patient occurred during SARS-CoV-2 infection in an immunocompetent host; we suspect that SARS-CoV-2 triggered the demyelinating process in a manner similar to typical MS onset. Therefore, what occurred to our young patient underlines once again the close relationship between viral infections (Coronavirus in this case) and exacerbations of MS (see for example the reported rise in MS relapse following an episode of Epstein–Barr, VZ, Cytomegalo, or Flu virus infection). 8

Another interesting consideration can be made regarding the use of steroids in MS patient with a concomitant SARS-CoV-2 positivity; although steroids have been actually recognized as a treatment for COVID-19 infection, this was not so clear when our young patient was hospitalized on late 2020. So, we preferred to delay steroid administration until confirmation of COVID-19 remission to avoid inducing immunodepression; such a change in immune status could convert COVID-19 from an asymptomatic entity to clinical disease. Furthermore, we preferred an intravenous route of administration with a high dosage considering the age of the patient, the dramatic MRI features, and the bilateral severe impairment of the ocular motility. We are aware that oral steroids may be considered a valid alternative for MS in this COVID-19 pandemic era but this has been demonstrated in cases of relapses. 9

The impact of COVID-19 on visual pathways is not yet known, but this case report is expected to enhance general understanding of central nervous system involvement in COVID-19. We emphasize the importance of an appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic approach in affected patients to avoid transient steroid-related immunodeficiency, which could exacerbate viral infection.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Arturo Carta https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6284-0588

Emanuela Claudia Turco https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4896-1164

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Walsh RD, McClelland CM, Galetta SL. The neuro-ophthalmology of multiple sclerosis. Future Neurol 2012; 7: 679–700. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray RS, Brown B, Brian Det al. et al. Detection of coronavirus RNA and antigen in multiple sclerosis brain. Ann Neurol 1992; 31: 525–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cristallo A, Gambaro F, Biamonti Get al. et al. Human coronavirus polyadenylated RNA sequences in cerebrospinal fluid from multiple sclerosis patients. New Microbiol 1997; 20: 105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sigari AA, Etemadifar M, Salari M. Complete horizontal gaze palsy due to bilateral paramedian pontine reticular formation involvement as a presentation of multiple sclerosis: a case report. BMC Neurol 2019; 19: 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nerrant E, Tilikete C. Ocular motor manifestations of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroophthalmol 2017; 37: 332–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin JE, Asfour A, Sewell TB, et al. Neurological issues in children with COVID-19. Neurosci Lett 2021; 743: 135567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Z, Kang H, Li Set al. et al. Understanding the neurotropic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2: from neurological manifestations of COVID-19 to potential neurotropic mechanisms. J Neurol 2020; 267: 2179–2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donati D. Viral infections and multiple sclerosis. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models 2020; 32: 27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segamarchi C, Silva B, Saidon P, et al. Would it be recommended treating multiple sclerosis relapses with high dose oral instead intravenous steroids during the COVID-19 pandemic? Yes. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020; 46: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]