Abstract

Nitrate flux between sediment and water, nitrate concentration profile at the sediment-water interface, and in situ sediment denitrification activity were measured seasonally at the innermost part of Tokyo Bay, Japan. For the determination of sediment nitrate concentration, undisturbed sediment cores were sectioned into 5-mm depth intervals and each segment was stored frozen at −30°C. The nitrate concentration was determined for the supernatants after centrifuging the frozen and thawed sediments. Nitrate in the uppermost sediment showed a remarkable seasonal change, and its seasonal maximum of up to 400 μM was found in October. The directions of the diffusive nitrate fluxes predicted from the interfacial concentration gradients were out of the sediment throughout the year. In contrast, the directions of the total nitrate fluxes measured by the whole-core incubation were into the sediment at all seasons. This contradiction between directions indicates that a large part of the nitrate pool extracted from the frozen surface sediments is not a pore water constituent, and preliminary examinations demonstrated that the nitrate was contained in the intracellular vacuoles of filamentous sulfur bacteria dwelling on or in the surface sediment. Based on the comparison between in situ sediment denitrification activity and total nitrate flux, it is suggested that intracellular nitrate cannot be directly utilized by sediment denitrification, and the probable fate of the intracellular nitrate is hypothesized to be dissimilatory reduction to ammonium. The presence of nitrate-accumulating sulfur bacteria therefore may lower nature's self-purification capacity (denitrification) and exacerbate eutrophication in shallow coastal marine environments.

Nitrogen is a primary limiting nutrient in many coastal marine environments (15, 17), and N removal via denitrification in sediments is an important process regulating the degree of eutrophication of shallow coastal ecosystems (19). The availability of nitrate (NO3−) is an important factor controlling denitrification activity in many aquatic sediments (12, 19, 20).

Lomstein et al. (13) demonstrated the presence of intracellular pools of NH4+ and NO3− in deposited microalgae in the surface sediment of a coastal bay area and found a distinct seasonal maximum for both pools after sedimentation of a phytoplankton bloom in early spring and a minimum in fall and winter.

In 1995, it was reported that there is a large pool of intracellular NO3− associated with filamentous sulfur bacteria, Thioploca spp. from the continental shelf under the oxygen-minimum zone in the upwelling region off the coast of Peru and Chile at a water depth between 40 and 280 m (7, 26). Analysis of single filaments of Thioploca showed that intracellular NO3− is contained in their vacuoles at concentrations up to 500 mM (7). It was previously assumed that Thioploca would reduce their intracellular NO3− to dinitrogen (N2) gas (denitrification), but the incubation experiments of washed Thioploca sheaths with 15N compounds showed that although conversion to dinitrogen cannot be ruled out, dissimilatory reduction of NO3− to ammonium (NH4+) is the preferred pathway in Thioploca (16). Beggiatoa spp. from the Bay of Concepción, Chile, at a depth of 25 m, also have the capacity to concentrate NO3− intracellularly at levels ranging from 15 to 116 mM (25), indicative of a similar nitrate-respiring metabolism.

Intracellular NO3− accumulation at concentrations of 130 to 160 mM was also reported for large, vacuolate, filamentous sulfur bacteria, Beggiatoa spp., from a Monterey Canyon cold seep at a depth of 900 m and from Guaymas Basin hydrothermal vents at a depth of 2,004 m (14). A respiratory conversion of NO3− to NH4+ driven by oxidation of hydrogen sulfide or endogenous stores of elemental sulfur is indicated as the metabolism for their intracellular NO3− (D. C. Nelson, S. C. McHatton, A. A. Ahmed, and J. P. Barry, Abstr. 1999 Aquat. Sci. Meet. Am. Soc. Limnol. Oceanogr., 1999).

Furthermore, a new genus of nitrate-accumulating sulfur bacteria, Thiomargarita, was found off the Namibian coast. Thiomargarita also oxidizes sulfide with NO3− that is accumulated to a concentration of 100 to 800 mM in a central vacuole (18). All three genera of nitrate-accumulating sulfur bacteria, Thioploca, Beggiatoa and Thiomargarita, are closely related according to 16S rRNA sequences and seem to have a similar physiology (18).

Nitrate-accumulating sulfur bacteria discovered to date inhabit sediments of upwelling areas characterized by high primary productivity, high sediment concentrations of soluble sulfide, and low levels of dissolved oxygen in bottom waters (7, 14, 18, 25). The probable fate of the intracellular NO3− accumulated in their vacuoles is considered to be dissimilatory reduction to NH4+ (11, 16; Nelson et al., Abstr. 1999 Aquat. Sci. Meet. Am. Soc. Limnol. Oceanogr.). The ecological implication of their nitrate metabolism, namely, that intracellular NO3− is dissimilatorily reduced to NH4+ is significant, since this means that nitrogen is conserved within the system and is recycled into pelagic nitrogen cycling.

In the present study, NO3− flux between sediment and water, NO3− concentration profile at the sediment-water interface, and in situ sediment denitrification activity were measured seasonally at the innermost part of Tokyo Bay, Japan, which is a shallow, semienclosed basin characterized by strong, human-induced eutrophication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site.

The investigation was carried out at a 10-m-deep station in the innermost part of Tokyo Bay (35.62°N, 139.98°E) (Fig. 1). The sediment texture was that of silty mud with a high organic-matter content (particulate organic carbon [POC]; ∼2% sediment [dry weight]), and the sediment was poorly inhabited by benthic fauna throughout the year due to anoxia in the bottom water during summer. Oxygen penetration depth in the surface sediment was only 2 to 3 mm even when dissolved oxygen (O2) in the bottom water was at air saturation (M. Sayama, unpublished data).

FIG. 1.

Study area and sampling site (●) in the innermost part of Tokyo Bay.

Sampling.

Water and sediment were sampled by scuba diving at approximately monthly intervals. Temperature, salinity, and concentrations of O2, nitrite (NO2−) and NO3− were determined in samples of surface water (0.3 m below the surface) and bottom water (20 cm above the sediment). Samples for determination of O2 concentrations were taken in 100-ml Winkler bottles. Samples for determination of NO2− and NO3− concentrations were stored frozen at −30°C in 50-ml polyethylene bottles. Sediment samples were collected in 5-cm-wide (inside diameter [i.d.]) and 25-cm-long acrylic tubes for determination of density, water content, total NO3− flux between sediment and water, concentration profiles of NO3− at the sediment-water interface, and in situ sediment denitrification activity. All sediment cores were carefully inspected, and only those with an undisturbed sediment-water interface were used. All measurements were initiated in the laboratory within a few hours after sampling.

Total NO3− flux.

Total NO3− flux between sediment and water was determined by whole-core incubation in the dark at the in situ bottom water temperature using four intact cores in 1992 to 1993 according to the method described by Jensen et al. (8), with some modifications. The sediment was first adjusted in height so that the acrylic tubes contained about 17 cm of sediment core overlaid by 8 cm of water (corresponding to about 150 ml). The water phase was then discarded (except for a few milliliters to avoid disturbance of the sediment-water interface) and was carefully replaced by 100 ml of fresh bottom water that was filtered through Whatman GF/C filters (1.2-μm-pore-size fiber glass filters) and aerated at atmospheric saturation. Teflon-coated magnets (0.5 by 3 cm) were placed in the water column 1 cm above the sediment surface and were gently driven by an external, rotating magnet to ensure appropriate stirring of the water column. The cores were transferred into a thermostatted water bath at the in situ bottom water temperature, and total flux measurement was started about 15 min later. The top of the core tubes was kept open during the incubation to allow repeated sampling of the overlying water so that the dissolved O2 concentrations in the overlying water were always under nearly air-saturated conditions during the total flux measurements. Two and a half milliliters of the overlying water was taken at 0.5- to 1-h intervals, and a total of six water samples were withdrawn during 4 h of incubation. The total flux was calculated by measuring the changes in concentration in the overlying water during the incubation (linear regression) and by multiplying the obtained rate with the specific volume/surface area ratio of the water overlying the sediment core. No correction was made for water column activity, since filtered bottom water was used as the overlying water.

NO3− concentrations in sediment.

NO3− concentrations in the sediments were determined in 1992 to 1993 together with the total flux measurements. To determine NO3− concentrations in the sediment, three undisturbed sediment cores were sectioned into 5-mm-depth intervals, and each segment was stored frozen at −30°C for several weeks. Pore water was separated by centrifuging the frozen and thawed sediment samples at 2,000 × g for 10 min, and the NO3− concentration was determined for the supernatants.

Diffusive NO3− flux.

Molecular diffusive flux (Fdiffusive) of NO3− between sediment and water was calculated from the interfacial concentration gradient using Fick's first law of diffusion (e.g., see article by Berner [4]):

|

where φ is porosity at the sediment surface (depth, 0 to 5 mm), Ds is the molecular diffusion coefficient in sediment (Ds = φ2D0) (Ullman and Aller [27]), D0 is the temperature-corrected molecular diffusion coefficient in water (5), and dC/dx is the interfacial concentration gradient. Interfacial concentration gradients were found by linear interpolation between the bottom water concentration at the sediment surface and the concentration in the 0- to 5-mm-depth section assigned to a depth of 2.5 mm.

NO3− concentration profiles before and after freezing samples of water and sediment.

Since freezing and thawing the samples of water and sediment seemed to have some effect on the NO3− concentration, a change of NO3− concentration profile before and after freezing of the samples of water and sediment was examined in October 1993. To determine the NO3− concentration profiles at the sediment-water interface, the overlying water in an undisturbed sediment core was withdrawn at 5-mm intervals with a syringe through a vertical series of silicone-filled holes (i.d., 2.5 mm) placed at 5-mm intervals along the side of the core tubes and the sediment in the same core was then sliced into discrete depth intervals. Each sample of water or sediment was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min immediately after sectioning (unfrozen samples) or was stored frozen at −30°C for several weeks and centrifuged immediately after thawing (frozen samples). The NO3− concentration was determined for the supernatants.

Variations of NO3− and NH4+ concentrations in sediment caused by different extraction conditions.

Since the NO3− concentration found in frozen sediment of 0- to 5-mm depth was extremely high in October, variations of NO3− and NH4+ concentrations in the sediment caused by different extraction conditions were examined in October 1993. Freshly sectioned surface (depth, 0 to 5 mm) sediment was homogeneously mixed and then treated as follows. (i) The sediment was centrifuged immediately. (ii) Homogenized fresh sediment (2.5 g [wet weight]) was added to a 45-ml polypropylene centrifuge tube containing 10 ml of artificial seawater (ASW) (27.2 g of NaCl, 0.7 g of KCl, 2.0 g of CaCl2, and 6.0 g of MgSO4 per liter, with an adjusted pH of 8.0 to 8.2 and 0.05% NaHCO3), and the sediment suspension was shaken vigorously for >2 min and then centrifuged. (iii) Procedure was the same as for ii, but deionized water (DW; Milli-Q) was used instead of ASW. (iv) Procedure was the same as for ii, but 1 M KCl was used instead of ASW. (v) The sediment mixture was stored frozen at −30°C and centrifuged immediately after thawing. Each treatment was done in triplicate, and NO3− and NH4+ concentrations were determined for the supernatants after centrifuging at 2,000 × g for 10 min.

In situ sediment denitrification.

In situ denitrification activity was measured in 1988 to 1989 separately from the flux and concentration measurements. Additional measurements were repeated to verify the reproducibility of the activity in July and November 1990. The measurements of denitrification were based upon the acetylene inhibition technique with undisturbed sediment cores (22). Acetylene, which inhibits the reduction of N2O to N2, is distributed into undisturbed sediment cores, and the rate of N2O accumulation in cores is used as a measure of in situ denitrification. I essentially used the core design and incubation procedure described by Andersen et al. (1) with slight modification.

Six sediment cores were taken for each determination of denitrification activity. In each core, the water phase was first discarded (except for a few milliliters to avoid disturbance of the sediment-water interface) and was carefully replaced with fresh bottom water to fill up the core tubes completely. The bottom water, whose dissolved O2 concentration had been kept at nearly in situ level, was used without filtration. The core was then hermetically capped with a rubber stopper, leaving ca. 8 cm (150-ml volume) of the overlying water. A small magnetic stirring bar was placed underneath the rubber stopper to mix the water phase in the same way as the total flux measurement. C2H2-saturated distilled water (600 μl) was injected into the sediment at depths from 0 to 6 cm through a vertical series of silicone-filled holes (i.d., 2.5 mm) placed at 5-mm intervals along the side of the tubes. The water phase also received C2H2-saturated water, and the final inhibitory concentrations in the pore water and in the overlying water were about 10% of saturation (vol/vol). The cores were incubated in the dark at the in situ bottom water temperature using a thermostatted water bath. Incubations of duplicate cores were terminated at 0, 1, and 2 h.

After incubation, the exact height (volume) of the water in each tube was recorded. Ten milliliters of the water phase was then transferred to a closed serum bottle (70-ml volume). The bottle was shaken vigorously for >1 min to equilibrate the dissolved N2O with the gas phase. The excess pressure was then released by inserting a needle to the rubber stopper of the serum bottle, and 5 ml of the headspace gas was taken to a preevacuated glass vial of this volume (Venoject, VT-050P; Terumo Corp., Tokyo, Japan) for storage. After removal of the overlying water, the upper 6 cm of the sediment was sectioned into depth intervals of 0 to 1, 1 to 2, 2 to 4, and 4 to 6 cm. Each segment was quickly transferred to a preweighed 100-ml beaker containing 20 ml of 4% (vol/vol) neutralized formalin. The beakers were immediately closed with rubber stoppers and shaken for >1 min. After the weight of each segment had been recorded, another 5 ml of the headspace gas was stored in a preevacuated Venoject tube for analyses of N2O.

In the headspace analysis, the volumetric solubility coefficients given by Weiss and Price (28) were used to calculate the concentration of N2O in the original samples of water and sediment. The cores terminated at zero time were to correct for in situ N2O content in the water and sediment. Denitrification activity at each sediment layer was calculated as the mean of the N2O accumulation rates measured in four different cores. I assumed that the N2O accumulating in the water phases of the cores was a result of diffusion from the uppermost centimeter of the sediment. This assumption seemed valid because the accumulation of N2O during the incubations with C2H2 was always highest in the uppermost centimeter, thus creating a gradient of N2O up into the water phase. Arial activity of denitrification was calculated from depth integration of the activity in the sediment at a depth from 0 to 6 cm.

Chemical analysis.

Salinity was measured potentiometrically, and a Winkler titration was performed to determine the dissolved O2 concentration (24). Nutrient concentrations were determined by an autoanalyzer (AutoAnalyzer II; Bran+Luebbe Inc., Tokyo, Japan) using the methods of Solorzano (21) for NH4+ and Armstrong et al. (2) for NO3− and NO2− after thawing of the stored frozen samples. When necessary, an additional centrifugation (2,000 × g, 10 min) was performed to clear the supernatants completely. Triplicate determinations of the densities (grams centimeter−3) and water contents (weight loss after 24 h at 105°C) of the sediment samples served to convert the measured concentrations and activities into appropriate dimensions.

N2O was analyzed on a Shimadzu model GC-14APsE gas chromatograph equipped with a 63Ni Electron Capture Detector kept at 320°C. A backflush system prevented C2H2 contamination of the detector. Gases were separated on an 80/100-mesh Porapak Q column (2 m long and 3 mm wide) operated at 80°C. Pure N2 was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 15 ml min−1.

RESULTS

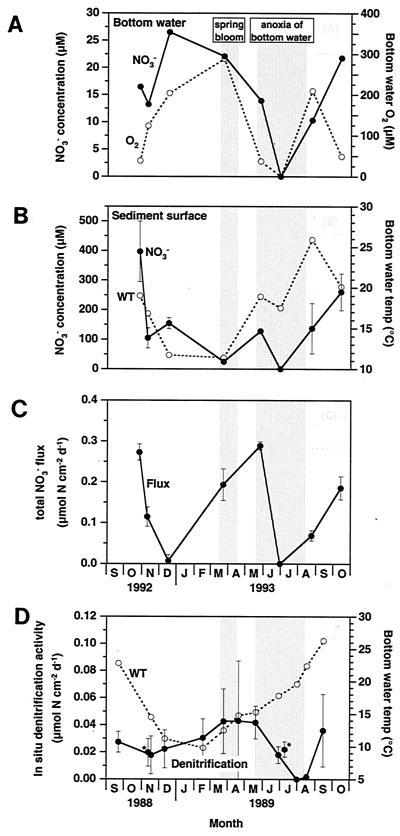

The inner part of Tokyo Bay is characterized by strong, human-induced eutrophication, and due to the marked saline stratification, O2 was totally depleted (anoxia) in the bottom water during summer over a wide area (Fig. 2). As destratification was initiated in early fall, O2 concentrations in the bottom water gradually increased and recovered to nearly air-saturated conditions during winter and early spring. Episodic oxygen depletion in the bottom water was often observed in late spring and early summer.

FIG. 2.

(A) Seasonal variations of O2 and NO3− concentrations in bottom water, 1992 to 1993. Symbols: ●, NO3− concentration; ○, O2− concentration in bottom water. (B) Seasonal variation of NO3− concentrations extracted from frozen and thawed samples of the uppermost sediment (depth, 0 to 5 mm), 1992 to 1993 (n = 3; SE indicated). Symbols: ●, NO3− concentration; ○, bottom water temperature (WT) (C) Seasonal variation of the total NO3− flux between sediment and water, 1992 to 1993 (n = 4; SE indicated). Positive values indicate flux from the overlying water into the sediment. d−1, day−1. (D) Seasonal variation of the activity of in situ sediment denitrification, 1988 to 1989. Symbols: ●, denitrification activity (n = 4; SE indicated); ○, bottom water temperature (WT). ∗, These two points were measured in 1990 to inspect the reproducibility of sediment denitrification activity. There was good agreement with activity results obtained in different years. Shaded areas indicate (left to right) the period of a spring phytoplankton bloom and the period of anoxic bottom water.

Total NO3− flux.

The directions of the total NO3− fluxes between sediment and water measured with undisturbed sediment cores were from the overlying water into the sediment at all seasons (Fig. 2). A maximum uptake of 0.27 μmol of N cm−2 day−1 was recorded in October 1992; the uptake decreased rapidly in late fall and was negligible in December. A dramatic increase was observed in early spring following the sedimentation of a phytoplankton bloom, and the uptake reached its maximum again in March to May. There was no NO3− uptake during the marked summer stratification when O2 and NO3− were absent in the bottom water. As destratification was initiated in early fall, the uptake started to increase and reached its maximum again in October 1993.

During the total flux measurements, the cores were always incubated at nearly air-saturated conditions, but in situ bottom water concentrations of dissolved O2 were sometimes deficient, especially during the summer stratification. The supplementary experiments showed that there was no significant influence of dissolved O2 concentrations in the overlying water on the total NO3− flux in July (Sayama, unpublished data). In August, the NO3− uptake into the sediment measured at 100% air saturation (0.07 ± 0.01 μmol of N cm−2 day−1; mean ± standard error [SE]; n = 4) was somewhat lower than that measured at 0% air saturation (0.10 ± 0.02 μmol of N cm−2 day−1; n = 4).

NO3− concentrations in frozen sediment.

The NO3− concentrations extracted from the frozen sediment samples always peaked at a depth of 0 to 5 mm throughout the year, except in July. There was a huge pool of NO3−, ca. 400 μM, in the uppermost sediment (depth, 0 to 5 mm) in October 1992 (Fig. 2). The NO3− pool at the sediment surface decreased considerably in late fall and was negligible in early spring. The NO3− pool recovered to the winter level during early summer, but a final depletion occurred during the summer stratification when O2 and NO3− were absent in the bottom water. As destratification was initiated in early fall, the NO3− pool increased dramatically and a huge pool of ca. 260 μM was found again in October 1993. The NO3− concentrations in the uppermost sediments exceeded the concentration in the bottom water throughout the year (Fig. 2), and the interfacial concentration gradient was the steepest in October.

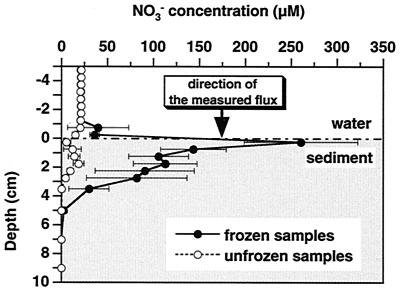

NO3− concentration profiles before and after freezing samples of water and sediment.

The NO3− concentration profiles changed significantly before and after samples of water and sediment collected in October 1993 were frozen (Fig. 3). The NO3− pool in the surface sediment of unfrozen samples (centrifuged immediately after sectioning) was much lower than that of frozen samples (frozen at −30°C and centrifuged immediately after thawing). In contrast to the concentration profile of the frozen samples, the great peak of NO3− was never observed in the uppermost sediment in the unfrozen samples. NO3− concentrations of the unfrozen samples showed a minimum in the uppermost sediment layer, followed by a small peak at a depth of 15 to 20 mm. The most striking feature was the shift of the interfacial concentration gradient to the inverse direction.

FIG. 3.

NO3− concentration profiles before and after samples of water and sediment from undisturbed sediment cores collected in October 1993 were frozen. Samples of water and sediment were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min immediately after sectioning or were stored frozen at −30°C and centrifuged immediately after thawing. The NO3− concentration was determined for the supernatants. Symbols mark the mean of replicate measurements (n = 3), and error bars indicate SE.

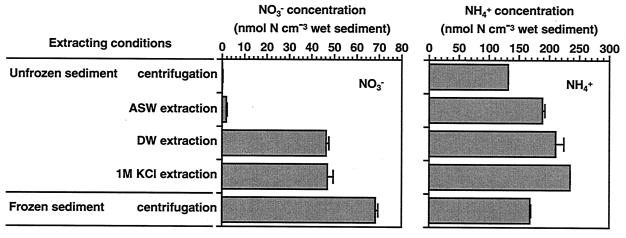

Variations of NO3− and NH4+ concentrations in sediment caused by different extraction conditions.

The NO3− concentration extracted by immediate centrifugation of unfrozen surface (depth, 0 to 5 mm) sediment collected in October 1993 was only 0.22 ± 0.06 nmol of N cm wet sediment−3 (mean ± SE; n = 3) (Fig. 4). There was a slight increase in the NO3− concentration when ASW extraction was performed: 1.96 ± 0.22 nmol of N cm wet sediment−3. However, DW extraction and 1 M KCl extraction resulted in a dramatic increase, with values of 46.4 ± 1.3 nmol of N cm wet sediment−3 for DW extraction and 47.0 ± 2.6 nmol of N cm wet sediment−3 for 1 M KCl extraction, which were roughly comparable to the concentration extracted from frozen sediment, 68.5 ± 1.0 nmol of N cm wet sediment−3.

FIG. 4.

Variations of NO3− and NH4+ concentrations in the sediment caused by different extraction conditions. Freshly sectioned surface (depth, 0 to 5 mm) sediment collected in October 1993 was homogeneously mixed and was then (i) centrifuged immediately, (ii) extracted with ASW, (iii) extracted with DW, (iv) extracted with 1 M KCl, and (v) stored frozen at −30°C and centrifuged immediately after thawing. NO3− and NH4+ concentrations were determined for the supernatants after centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 min. Bars represent the mean of replicate measurements (n = 3), and error bars indicate SE.

The variation of NH4+ concentration caused by different extraction conditions was statistically significant (P < 0.01) (analysis of variance), but it was fairly small compared to the variation for NO3− concentration (Fig. 4).

In situ sediment denitrification.

Similar to what was seen for the NO3− pool of frozen sediment, the activity of in situ sediment denitrification peaked at a depth of 0 to 5 mm in all seasons (data not shown). The activity of in situ sediment denitrification was approximately 0.02 μmol of N cm−2 day−1 in winter (Fig. 2). Following the spring bloom sedimentation, a seasonal maximum activity of approximately 0.04 μmol of N cm−2 day−1 was found in March to May. A final depletion occurred during the summer stratification when O2 and NO3− were absent in the bottom water. As destratification was initiated in early fall, the activity recovered to the winter level. Additional measurements in 1990 verified that there was good agreement with the activities obtained at different years (Fig. 2). Therefore, it seems reasonable to compare denitrification activity with the total NO3− flux measured during different years.

DISCUSSION

Intracellular nitrate pool in Tokyo Bay sediment.

In studies of sediment nitrogen cycling in shallow coastal marine sediments, attention has so far mainly been given to NO3− dissolved in pore water and an NO3− pool that is not a pore water constituent has been considered unlikely to exist in sediments.

The NO3− concentrations extracted from the frozen samples of the uppermost sediment (depth, 0 to 5 mm) always exceeded the concentration in the bottom water (Fig. 2), and the interfacial concentration gradient was the steepest in October. The directions of the diffusive NO3− fluxes predicted from the interfacial concentration gradients were out of the sediment throughout the year. In contrast, the directions of the total NO3− fluxes measured with the undisturbed sediment cores were into the sediment at all seasons, and a seasonal maximum uptake was recorded in October and in March to May (Fig. 2). This contradiction between the directions of the diffusive flux and of the total flux implies that a large part of the NO3− pool extracted from the frozen surface sediments is not a pore water constituent, particularly in October.

This hypothesis is also supported by the finding that the NO3− pool of unfrozen surface sediments (centrifuged immediately after sectioning) was much smaller than that of the frozen surface sediments collected in October (Fig. 3 and 4) and that the NO3− concentration profiles changed significantly before and after the samples of water and sediment collected in October were frozen (Fig. 3). In contrast to the concentration profile of the frozen samples, the great peak of NO3− was never observed in the uppermost sediment in the unfrozen samples (Fig. 3). The most striking feature is the shift of the interfacial concentration gradient to the inverse direction. Now the direction of the diffusive NO3− flux predicted from the interfacial concentration gradient of the unfrozen samples is in agreement with that of the total NO3− flux measured with the undisturbed sediment cores.

Lomstein et al. (13) demonstrated the presence of intracellular pools of NH4+ and NO3− in deposited microalgae in the surface sediment of a coastal bay area and found a distinct seasonal maximum for both pools after sedimentation of a phytoplankton bloom in early spring and a minimum in fall and winter. The NO3− pool extracted from the frozen surface sediments in Tokyo Bay is, however, inferred not to be an intracellular pool in deposited microalgae, because the NO3− pool was small in late spring (Fig. 2) and NH4+ concentration showed only a minor change before and after the surface sediment collected in October was frozen (Fig. 4).

Recently, NO3− accumulation in an intracellular vacuole at concentrations greater than 15 to 800 mM has been reported for sulfur-oxidizing bacteria from offshore and deep-sea sediments of upwelling areas (7, 14, 18, 25). Those sulfur-oxidizing bacteria inhabit the environments characterized by high primary productivity, high sediment concentrations of soluble sulfide, and low levels of dissolved O2 in surrounding waters.

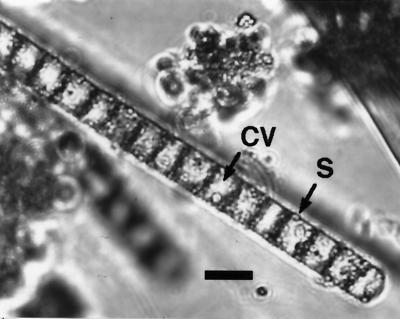

In hypertrophic, shallow coastal marine environments where sulfide production in the sediment is high and O2 in the bottom water is often depleted, white mats of filamentous sulfur bacteria on the sediment surface are frequently encountered (9, 10). In fact, there were filamentous sulfur bacteria in the surface sediment at the site of this study in October, and massive mats of filamentous sulfur bacteria are often formed on the sediment surface during the period of transition from anoxic to oxic bottom water. A preliminary microscopic inspection showed that the filamentous sulfur bacteria that constitute the white mats covering the sediment surface in Tokyo Bay in October 2000 are characterized by living as individual filaments, having considerable diameters (around 9 μm), and having a large central vacuole and intracellular globules of elemental sulfur (Fig. 5). These morphological characteristics of the bacteria are very much similar to those for a wide, vacuolate, nitrate-accumulating Beggiatoa sp. from a Monterey Canyon cold seep and Guaymas Basin hydrothermal vents (14) and from the Bay of Concepción, Chile (25). All populations of large, vacuolated Beggiatoa examined to date share the ability to concentrate NO3− at levels ranging from 15 to 160 mM in their intracellular vacuoles. Furthermore, a preliminary examination demonstrated that the filamentous sulfur bacteria in the surface sediment sampled at the study site in Tokyo Bay in October 2000 accumulated NO3− intracellularly at concentrations of 105 ± 36 mM (mean ± SE; n = 3) (Sayama and T. Kuwae, unpublished data).

FIG. 5.

Photomicrograph of suspended surface sediment (depth, 0 to 1 mm) sampled on 31 October 2000. CV, large central vacuole; S, intracellular globules of elemental sulfur. Bar, 10 μm.

Therefore, it seems reasonable to conclude that the huge NO3− pool extracted from the frozen surface sediments in Tokyo Bay is contained in the intracellular vacuoles of the filamentous sulfur bacteria, that freezing and thawing the surface sediment result in the breakage of the bacterial cells (14), and that intracellular NO3− is released into pore water in frozen and thawed sediments. The NO3− concentration extracted by use of ASW from the unfrozen surface (depth, 0 to 5 mm) sediment collected in October was negligibly low, while the NO3− concentrations extracted by use of DW and 1 M KCl were enormously high and roughly comparable to the concentration extracted from the frozen sediment (Fig. 4). This result can be consistently explained by the rupture of bacterial cells due to a drastic change in osmotic pressure and evidently supports the above conclusion.

The molecular diffusive flux (Fdiffusive) of NO3− in October calculated using the equation given earlier with the interfacial concentration gradient of the unfrozen samples (Fig. 3) is 0.04 ± 0.01 μmol of N cm−2 day−1 (n = 3), which is rather small compared to the total NO3− flux in October, 0.19 ± 0.03 μmol of N cm−2 day−1 (Fig. 2) (smaller by a factor of four). Therefore, the transport process dominating the sediment-water exchange of NO3− was not molecular diffusion at the study site in October. This result can be also explained consistently by the highly efficient gliding motility of Beggiatoa spp. and the large surface area of their filaments (9). Beggiatoa spp. may stretch their filaments up into the overlying water, take up NO3− from the nitrate-containing bottom water, and glide back into the sulfide-producing sediment.

Fate of intracellular nitrate.

The probable fate of the intracellular NO3− accumulated in the nitrate-accumulating sulfur bacteria discovered to date is considered to be dissimilatory reduction to NH4+ (11, 16; Nelson et al., Abstr. 1999 Aquat. Sci. Meet. Am. Soc. Limnol. Oceanogr.). The ecological implication of their nitrate metabolism, that intracellular NO3− is dissimilatorily reduced to NH4+, is significant, since this means that nitrogen is conserved within the system and is recycled into pelagic nitrogen cycling.

The in situ sediment denitrification activity measured by the acetylene inhibition technique was much smaller than the NO3− uptake by the sediment in almost all seasons, especially in March to May and in October (Fig. 2). The acetylene inhibition technique is subject to potential problems primarily because nitrification, and hence coupled denitrification, is inhibited by acetylene (3) and because inhibition of denitrification by acetylene can sometimes be incomplete, particularly in the presence of sulfide (6, 23), the concentration of which is generally very high in eutrophied coastal marine sediments. However, the difference between the NO3− uptake by the sediment and the in situ sediment denitrification activity was so large that it cannot be explained as an underestimation caused by the technical problems of the acetylene inhibition.

In addition, there was a significant correlation between NO3− and NO2− concentrations in the bottom water and the in situ sediment denitrification activity (r2 = 0.339; P < 0.05; n = 13). This suggests that the major source of NO3− for the sediment denitrification was coming from the overlying water at the study site.

From these results, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that the intracellular NO3− pool found in Tokyo Bay sediment cannot be directly utilized by the sediment denitrification and that the probable fate of it is also dissimilatory reduction to NH4+.

Influence of nitrate-accumulating sulfur bacteria on nitrogen cycling in sediment.

Judging from the difference between the NO3− concentrations in the bottom water and in the frozen and thawed surface sediments, there seems to be a significant amount of intracellular NO3− in almost all seasons (Fig. 2). The nitrate-accumulating sulfur bacteria therefore may play an important role in annual nitrogen cycling in shallow coastal marine sediment. In the innermost part of Tokyo Bay, the annual NO3− uptake into the sediment was 45.8 μmol of N cm−2 year−1 (Fig. 2), but the annual denitrification in the sediment was only 9.5 μmol of N cm−2 year−1 (Fig. 2), and the rest of NO3− taken up by the sediment (36.3 μmol of N cm−2 year−1) is hypothesized to be reduced dissimilatorily to NH4+. The ecological consequence of the huge pool of intracellular NO3− and its dissimilatory reduction to NH4+ is increased efflux of NH4+ to the water column (internal loading). Indeed, the annual NH4+ efflux was 207 μmol of N cm−2 year−1 at the site of this study (Sayama, unpublished data), and about 18% of the NH4+ released from the sediment is estimated to be coming from dissimilatory reduction of NO3−.

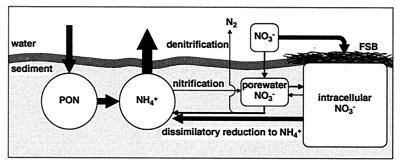

Summarizing the overall results, sediment nitrogen cycling at the sediment-water interface in the hypertrophic, shallow coastal marine environments where nitrate-accumulating sulfur bacteria dwell on or in the surface sediment is schematically illustrated in Fig. 6. A considerable amount of NO3− is transported into the intracellular NO3− pool in the surface sediment directly from the overlying bottom water by vertical migration of nitrate-accumulating sulfur bacteria. The accumulated intracellular NO3− is not directly available for sediment denitrification, and the probable fate of the intracellular NO3− is hypothesized as dissimilatory reduction to NH4+ and being recycled into pelagic nitrogen cycling together with the NH4+ coming from the mineralization of particulate organic nitrogen. Therefore, the presence of filamentous sulfur bacteria that accumulate a huge amount of NO3− in their intracellular vacuoles and reduce the intracellular NO3− dissimilatorily to NH4+ lowers nature's self-purification capacity (denitrification) and stimulates pelagic primary production or exacerbates eutrophication in shallow coastal marine environments.

FIG. 6.

Sediment nitrogen cycling at the sediment-water interface in hypertrophic, shallow coastal marine environments where nitrate-accumulating sulfur bacteria dwell on or in surface sediment. FSB, filamentous sulfur bacteria; PON, particulate organic nitrogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am very grateful to Peter Bondo Christensen (National Environmental Research Institute, Silkeborg, Denmark) for critical review of the manuscript and to S. Shimamura for technical assistance.

This study was supported by a grant from the Environmental Agency, Tokyo, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen T K, Jensen M H, Sørensen J. Diurnal variation of nitrogen cycling in coastal marine sediments I. Denitrification Mar Biol. 1984;83:171–176. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong F A, Stearns C R, Strickland J D. The measurement of upwelling and subsequent biological processes by means of the Technicon Autoanalyzer and associated equipment. Deep Sea Res. 1967;14:381–389. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bédard C, Knowles R. Physiology, biochemistry, and specific inhibitors of CH4, NH4+, and CO oxidation by methanotrophs and nitrifiers. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:68–84. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.68-84.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berner R A. Early diagenesis: a theoretical approach. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boudreau B P. Diagenetic models and their implementation: modelling transport and reactions in aquatic sediments. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen P B, Nielsen L P, Sørensen J, Revsbech N P. Microzonation of denitrification activity in stream sediments as studied with a combined oxygen and nitrous oxide microsensor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1234–1241. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.5.1234-1241.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fossing H, Gallardo V A, Jørgensen B B, Hüttel M, Nielsen L P, Schulz H, Canfield D E, Forster S, Glud R N, Gundersen J K, Küver J, Ramsing N B, Teske A, Thandrup B, Ulloa O. Concentration and transport of nitrate by the mat-forming sulphur bacterium Thioploca. Nature. 1995;374:713–715. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen M H, Lomstein E, Sørensen J. Benthic NH4+ and NO3− flux following sedimentation of a spring phytoplankton bloom in Aarhus Bight, Denmark. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1990;61:87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jørgensen B B. Distribution of colorless sulfur bacteria (Beggiatoa spp.) in a coastal marine sediment. Mar Biol. 1977;41:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jørgensen B B, Richardson K. Eutrophication in coastal marine ecosystems. Washington, D.C.: American Geophysical Union; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jørgensen B B, Gallardo V A. Thioploca spp.: filamentous sulfur bacteria with nitrate vacuoles. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1999;28:301–313. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koike I, Sørensen J. Nitrate reduction and denitrification in marine sediments. In: Blackburn T H, Sørensen J, editors. Nitrogen cycling in coastal marine environments. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 1988. pp. 251–273. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lomstein E, Jensen M H, Sørensen J. Intracellular NH4+ and NO3− pools associated with deposited phytoplankton in a marine sediment (Aarhus Bight, Denmark) Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1990;61:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHatton S C, Barry J P, Jannasch H W, Nelson D C. High nitrate concentrations in vacuolate autotrophic marine Beggiatoa spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:954–958. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.954-958.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nixon S W. Remineralization and nutrient cycling in coastal marine ecosystems. In: Nelson B J, Cronin L E, editors. Estuaries and nutrients. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 1981. pp. 111–138. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otte S, Kuenen J G, Nielsen L P, Paerl H W, Zopfi J, Schulz H N, Teske A, Strotmann B, Gallardo V A, Jørgensen B B. Nitrogen, carbon, and sulfur metabolism in natural Thioploca samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3148–3157. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.7.3148-3157.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryther J H, Dunstan W M. Nitrogen, phosphorus and eutrophication in the coastal marine environment. Science. 1971;171:1008–1013. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3975.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulz H N, Brinkhoff T, Ferdelman T G, Mariné M H, Teske A, Jørgensen B B. Dense populations of a giant sulfur bacterium in Namibian shelf sediments. Science. 1999;284:493–495. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seitzinger S P. Denitrification in freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems: ecological and geochemical significance. Limnol Oceanogr. 1988;33:702–724. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seitzinger S P. Denitrification in aquatic sediments. In: Revsbech N P, Sørensen J, editors. Denitrification in soil and sediment. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solorzano L. Determination of ammonia in natural waters by the phenol-hypochlorite method. Limnol Oceanogr. 1969;14:799–801. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sørensen J. Denitrification rates in a marine sediment as measured by the acetylene inhibition technique. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;36:139–143. doi: 10.1128/aem.36.1.139-143.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sørensen J, Rasmussen L K, Koike I. Micromolar sulfide concentrations alleviate acetylene blockage of nitrous oxide reduction by denitrifying Pseudomonas fluorescens. Can J Microbiol. 1987;33:1001–1005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strickland J D, Parsons T R. A practical handbook of seawater analysis. 2nd ed. Ottawa, Canada: Fisheries Research Board of Canada; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teske A, Sogin M L, Nielsen L P, Jannasch H W. Phylogenetic relationships of a large marine Beggiatoa. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1999;22:39–44. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(99)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thamdrup B, Canfield D E. Pathways of carbon oxidation in continental margin sediments off central Chile. Limnol Oceanogr. 1996;41:1629–1650. doi: 10.4319/lo.1996.41.8.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ullman W J, Aller R C. Diffusion coefficients in nearshore marine sediments. Limnol Oceanogr. 1982;27:552–556. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss R F, Price B A. Nitrous oxide solubility in water and seawater. Mar Chem. 1980;8:347–359. [Google Scholar]