Abstract

The conjugative transposon CTnDOT is virtually identical over most of its length to another conjugative transposon, CTnERL, except that CTnDOT carries an ermF gene that is not found on CTnERL. In this report, we show that the region containing ermF appears to consist of a 13-kb chimera composed of at least one class I composite transposon and a mobilizable transposon (MTn). Although the ermF region contains genes also carried on Bacteroides transposons Tn4351 and Tn4551, it does not contain the IS4351 element which is found on these transposons. In CTnDOT, insertion of the ermF region occurred near a stem-loop structure at the end of orf2, an open reading frame located immediately downstream of the integrase (int) gene of CTnDOT, and in a region known to be important for excision of CTnERL and CTnDOT. The chimera that comprises the ermF region can apparently no longer excise and circularize, but it contains a functional mobilization region related to that described for the Bacteroides MTn Tn4399. Analysis of 19 independent Bacteroides isolates showed that the ermF region is located in the same position in all of the strains analyzed and that the compositions of the ermF region are almost identical in these strains. Therefore, it appears that CTnDOT-like elements present in community and clinical isolates of Bacteroides were derived from a common ancestor and proliferated in the diverse Bacteroides population.

Bacteroides species contain two types of integrated transmissible elements, conjugative transposons (CTns) and mobilizable transposons (MTns). CTns carry genes needed for excision, conjugal transfer of the excised circular intermediate, and integration into the recipient genome. A recent study of human colonic Bacteroides isolates concluded that there is extensive horizontal gene transfer among Bacteroides strains (40). Today, more than 80% of Bacteroides isolates carry a CTn similar to those described here. CTns have been found in a variety of bacteria, including Enterococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Lactococcus spp., Butyrivibrio sp., Clostridium sp., Salmonella sp., Pseudomonas sp., Mezorhizobium sp., and Vibrio sp. (1, 11, 14, 19, 26, 28, 29, 34, 45, 51). MTns rely on CTn functions to trigger their excision and provide the transfer apparatus that allows the excised MTn circular forms to be transferred by conjugation. MTns have been found in Bacteroides spp. and in Clostridium sp. (9, 10, 13, 23, 39, 43, 47, 49) and may well have a wider distribution. Examples of Bacteroides MTns include Tn4399, Tn4555, Tn5520, NBU1, and NBU2. MTns of this type are widely distributed in different Bacteroides species. Approximately one-half of the natural isolates surveyed had DNA that cross-hybridized with a highly conserved region shared by most MTns (40). The MTns characterized in previous studies were not linked genetically to the CTns that mobilize them but rather were integrated in separate sites on the chromosome. CTn-encoded proteins required for MTn transfer act in trans to trigger excision and provide the mating apparatus. We report here the first example of an MTn that has integrated into a CTn and is transferred as part of the CTn; our results extend our understanding of the ecology and evolution of horizontal gene transfer mechanisms in the Bacteroides group.

The ermF region was found as a result of experiments performed to assess differences between two very closely related Bacteroides CTns, CTnERL and CTnDOT. In regions in which genes from both CTns have been sequenced, the sequence identity is high (>85% in most cases) (4). There are clearly differences between these two CTns, however; the most marked difference is that CTnDOT carries an ermF gene not found on CTnERL. This observation, together with the fact that CTnDOT appeared to be at least 10 kb larger than CTnERL, suggested that CTnDOT might have arisen from a CTnERL type of element by acquiring a DNA segment that contained ermF.

The ermF gene has previously been found on three Bacteroides plasmids (38, 42, 46). In all three cases, ermF was part of a 5- to 10-kb composite transposon, which was flanked by the insertion sequence IS4351. In contrast, the presence of ermF on CTnDOT was not associated with the presence of IS4351, since there was no cross-hybridization between IS4351 DNA and DNA from Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron carrying CTnDOT. In this work we located the junctions of the ermF region, and in this paper we describe the complete sequence of the 13-kb insertion, which appears to be a hybrid of mobilizable and nonmobilizable Bacteroides transposons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Community isolates were obtained from students in the microbial diversity course at Woods Hole, Mass. (designations beginning with WH), while all of the other strains are clinical isolates obtained from various sources in the United States (40). The methods used for growth of Bacteroides strains, DNA isolation, cloning, and conjugal transfer have been described previously (15, 30, 33, 37). The antibiotic concentrations used were as follows: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; cefoxitin, 20 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 10 μg/ml; erythromycin, 10 μg/ml; gentamicin, 200 μg/ml; tetracycline, 1 μg/ml; thymidine, 100 μg/ml; and trimethoprim, 100 μg/ml. To test for plasmid mobilization, cultures of Bacteroides mating donors were grown in the presence of tetracycline at a concentration of 1 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant phenotypea | Source and/or description | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | |||

| DH5aMCR | RecA | Gibco-BRL | |

| EM24R | RecA Strr Nalr Rifr | RecA derivative of LE392 with spontaneous mutations to rifampin and nalidixic acid resistance | 33 |

| J53 R751 | Tpr | Contains self-transmissible IncPβ plasmid, R751 | 16, 25 |

| HB101 | RecA Strr | 5 | |

| B. thetaiotaomicron 5482A strains | |||

| BT4100 | (Thy− Tpr) | Spontaneous thymidine-requiring mutant of BT5482A | 41 |

| BT4104 | (Thy− Tpr Tcr) | BT4100 with CTnERL inserted into the chromosome | 41 |

| BT4107 | (Thy− Tpr Tcr Emr) | BT4100 with CTnDOT inserted into the chromosome | 41 |

| BT4108 | (Thy− Tpr Tcr Emr) | BT4100 with CTn12256 inserted into the chromosome | 3 |

| Plasmids | |||

| pLYL7oriTRK2 | Apr Mob+ (Cefr Mob−) | E. coli-Bacteroides shuttle vector that is not mobilizable in Bacteroides | 20 |

| pLYL11 | Apr Mob+ (Cefr Mob−) | pLYL7oriTRK2 with a 2.5-kb fragment which includes the oriT-mob region from NBU1 | 20 |

| pGW39.1 | Apr Mob+ (Cefr Mob−) | 3.5-kb PCR product was amplified from BT4107 using Vent polymerase, digested with EcoRI, and cloned into the EcoRI-SmaI sites of pLYL7oriTRK2 | This study |

| pTC-COW | Cmr Mob+ (Cmr Tcr Mob+) | E. coli-Bacteroides shuttle vector that is mobilizable in E. coli and Bacteroides due to the pB8-51 oriV-mob region | 12 |

| pLYLO5 | Apr Mob+ (Cefr Mob+) | E. coli-Bacteroides shuttle vector that is mobilizable in E. coli and Bacteroides due to the pBI143 oriV-mob region | L.-Y. Li, unpublished data |

The phenotypes in parentheses are Bacteroides phenotypes, and the phenotypes not in parentheses are E. coli phenotypes. Abbreviations: Mob+, mobilizable by RP4 or R751 (in E. coli); (Mob+), mobilizable by CTnERL or CTnDOT (in B. thetaiotaomicron); (Mob−), not mobilizable by CTnERL or CTnDOT (in B. thetaiotaomicron); Apr, ampicillin resistance; Cefr, cefoxitin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Emr, erythromycin resistance; Nalr, naladixic acid resistance; Rifr, rifampin resistance; Strr, streptomycin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance; Tpr, trimethoprim resistance; Thy−, thymidine auxotroph.

Location of the junctions of the ermF region.

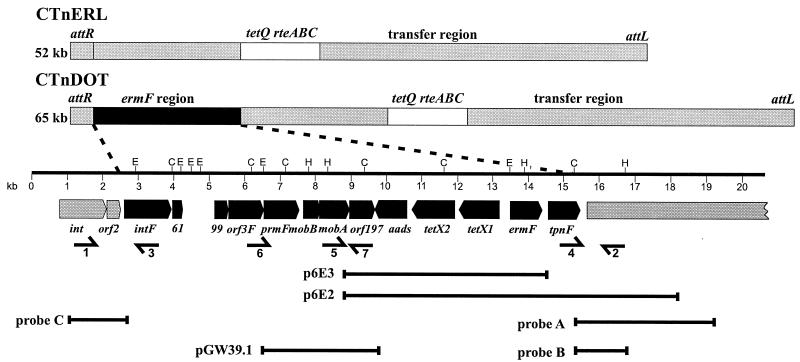

To locate the junctions of the ermF region, we tested previously cloned DNA fragments (p6E2 and p6E3) that contained portions of this region to find DNA segments that hybridized not only with DNA from B. thetaiotaomicron carrying CTnDOT but also with DNA from B. thetaiotaomicron carrying CTnERL (Fig. 1) (36). p6E3, which contained the smaller cloned region, hybridized to DNA from the strain carrying CTnDOT but not to DNA from the strain carrying CTnERL, whereas p6E2 hybridized to both. The two fragments cross-hybridized with each other, but p6E2 had an additional 4 kb of DNA. This indicated that one junction of the ermF region was located within this 4-kb segment (probe A [Fig. 1]). This 4-kb segment was subcloned to obtain smaller probes. The junction was further localized by using a 1.5-kb HindIII-ClaI fragment of p6E2 (probe B). The 1.5-kb probe hybridized to both CTnDOT and CTnERL.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the Bacteroides CTns CTnERL and CTnDOT. CTnDOT is distinguished from CTnERL by a 13-kb insertion designated the ermF region which is present in CTnDOT (black box) but absent from CTnERL. Regions present in both CTnDOT and CTnERL are indicated by gray and white boxes. Open reading frames and their orientations are indicated. Cosmid clones p6E3 and p6E2, probes A and B used for localization of the right ermF region junction, and probe C used for localization of the left ermF region junction are also shown. Primers and their directions are represented by arrows; these primers were utilized for amplification of junction fragments (primers 1 and 2), for detection of a putative circular transposition intermediate (primers 3 to 5), and for amplification of the putative mobilization genes for mobilization experiments (primers 6 and 7). The putative mobilization genes were cloned onto Bacteroides mobilization-deficient vector pLYL7oriTRK2, and the resulting construct was designated pGW39.1. Restriction sites for the following restriction enzymes are indicated: EcoRI (E), ClaI (C), and HindIII (H).

The other junction, the one closest to the end of CTnDOT, was located by using a segment containing the CTn integrase gene (int) as the probe (probe C [Fig. 1]). The int gene was located at the end of CTnDOT near the ermF region (attR). DNA preparations from cells carrying CTnDOT or CTnERL were digested with HincII and SspI. The int probe hybridized to DNA from both conjugative transposons, but the fragment from CTnDOT to which it hybridized was of a different size from that of the fragment from CTnERL to which it hybridized, indicating that the right junction was close to the integrase gene.

Sequencing of the ermF region.

To locate the junctions more precisely, we sequenced the regions of CTnDOT that contained the two junctions. These sequences were then compared with the sequences of the corresponding regions on CTnERL (Fig. 2). Initially, a sequence was obtained from the p6E2 clone, but it soon became apparent that the cloned DNA had probably undergone rearrangements and deletions. Consequently, information obtained from a partial sequence of p6E2 was used to design primers for PCR amplification of DNA directly from CTnDOT. The corresponding region on CTnERL was obtained by performing PCR with primers designed on the basis of the CTnDOT sequences from the left- and right-junction regions (Fig. 1). Sequencing of the ermF region was performed by the University of Illinois Biotechnology Genetic Engineering Facility with an Applied Biosystems model 373A, version 2.0.1A, dye terminator automated sequencer. Primers were synthesized by the University of Illinois Biotechnology Genetic Engineering Facility or by Operon Technologies, Inc. (Alameda, Calif.). Taq polymerase (Gibco-BRL), Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), or eLONGase polymerase (Gibco-BRL) was utilized according to the manufacturer's instructions.

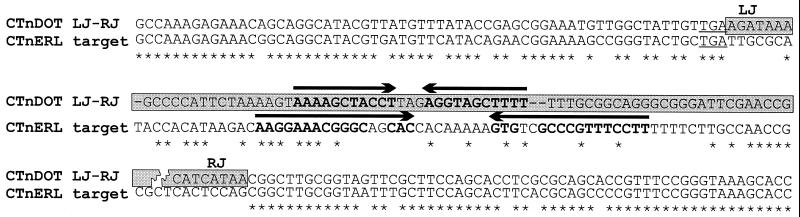

FIG. 2.

ClustalW alignment of the CTnERL target site for integration of the ermF region and the CTnDOT junction sequences at the left (LJ) and right (RJ) junctions of the ermF region. An asterisk indicates 100% nucleotide identity. The TGA stop codon of orf2 is underlined, and this codon is the point of divergence between the CTnERL and CTnDOT sequences at the left end of the ermF region. Potential stem-loop structures downstream of orf2 in CTnDOT and CTnERL target sequences are indicated by boldface type, and the directions of the inverted repeats are indicated by arrows above the appropriate sequences. Sequences that are part of the ermF region and hence are not present in CTnERL are indicated by a gray background. The 89 nucleotides of CTnERL between the stop codon of orf2 and the left and right junctions of the ermF region are not present in CTnDOT.

Comparison of ermF region left and right junctions from CTns other than CTnDOT.

In an effort to determine whether the ermF region is always found integrated downstream of orf2 and contains both MTn and nonmobilizable transposon components, PCR analyses of the left-junction (primers 1 and 3 [Fig. 1]) and right-junction (primers 2 and 4 [Fig. 1]) regions were performed. The strains of Bacteroides utilized in these studies were known to contain CTnDOT left and right ends and resistance determinants, which are associated with CTnDOT-like elements (e.g., ermF and tetX) (40). The primers utilized in these experiments are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| 1 | GGATGACCGCCACCGAAATAGCC |

| 2 | AGAATATGCGCAAAGGCTCG |

| 3 | CCTTTAACGTGGAGATGTACTTGTTG |

| 4 | CCCAGAACGAGCTGGAAGTACGATGG |

| 5 | ACAGACATTTCGGGGTTCTGCCATAG |

| 6 | TGAATATGTTGGCAGATTACGGAATGCGT |

| 7 | CATAACTACGTCGTACAACATCGTATTGG |

Assays for excision of the ermF region.

We tested for excision of the ermF region by using a Southern blot assay or a PCR assay. Testing for excision with the Southern blot method involved digesting DNA with enzymes, which cut around the junction regions, and probing with probes for the left and right junctions in order to detect an intermediate in which the left and right junctions were joined. To address the possibility that excision may be regulated by antibiotics, as is the case for CTnERL, CTnDOT, and NBU1 (32), we attempted to detect excision after exposing cells to tetracycline and/or erythromycin.

When excision frequencies are low, it is difficult to detect an excision product by a Southern blot assay. Therefore, we decided to test for excision by using a PCR assay, which involved using outward-facing primers in order to allow detection of a circular transposition intermediate. For all MTns in which the excised transposition intermediate has been characterized, a circular intermediate is formed, and so the primers are facing inward towards each other, although they are on opposite strands; use of these primers results in amplification and hence detection of the intermediate (22, 39, 43). Two sets of primers were used in case the ends of the MTn were not the ends of the 13-kb ermF region but were defined by the NBU-related part of that region (primers 3 and 4 or primers 3 and 5 [Fig. 1]).

Mobilization experiments.

To determine whether the putative mobilization genes were functional, a 3.5-kb PCR fragment containing the mobA and mobB genes was PCR amplified from a CTnDOT-containing Bacteroides strain, BT4107, and cloned into pLYL7oriTRK2 (20), generating pGW39.1 (primers 6 and 7 [Fig. 1]). The primers utilized in these experiments are shown in Table 2. pLYL7oriTRK2 contains a transfer origin from the conjugative plasmid RK2, which is recognized by the RP4 transfer apparatus but not by the transfer apparatus of CTnERL or CTnDOT and hence is not mobilizable in Bacteroides strains. pGW39.1 was subsequently transferred from Escherichia coli MCR to Bacteroides strains in a triparental mating in which another E. coli strain, HB101, contained the helper plasmid RP4. RP4 is not maintained in Bacteroides spp. Matings between Bacteroides donors and E. coli HB101 recipients to test the function of the mob genes were performed as described previously (20).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the ermF region has been submitted to the EMBL nucleotide sequence database and has been assigned the accession number AJ311171.

RESULTS

Size of the ermF region.

A comparison of the sequences from CTnERL and CTnDOT showed that ermF was in a 13-kb region that was not present in CTnERL (Fig. 1). The insertion appeared to have occurred near a stem-loop structure at the end of orf2, an open reading frame immediately downstream of the integrase gene (int) (7). This stem-loop structure is located 20 bp downstream of the orf2 stop codon and so may function as a transcriptional terminator for orf2; alternatively, it may be involved in the regulation of downstream genes via an attenuation mechanism. Despite the sequence divergence downstream of the orf2 stop codon in CTnERL and CTnDOT, upon integration of the ermF region element, another inverted repeat, a 22-bp inverted repeat, replaced the 34-bp repeat found in the CTnERL element (Fig. 2). Presumably, the replacement of a similar regulatory structure in this region may have minimized any problems that integration of a genetic element caused in this region. This is reminiscent of integration of other genetic elements, in many cases adjacent to tRNAs, which often results in substitution of one stem-loop structure that is thought to be involved in processing of the pre-tRNA molecule for another stem-loop structure (35, 52, 54). If the tRNA was subsequently not processed correctly, this could potentially affect the viability of the cell.

A comparison of sequences from CTnDOT and CTnERL showed that the elements had virtually identical sequences in the region around the insertion except for an 89-bp sequence on CTnERL, which did not align at all with the sequence of the junction regions on CTnDOT (Fig. 2). Either the entry of the inserted region caused deletions to occur in the region or CTnDOT arose from a CTn that was different from CTnERL in this region.

Features of the ermF region.

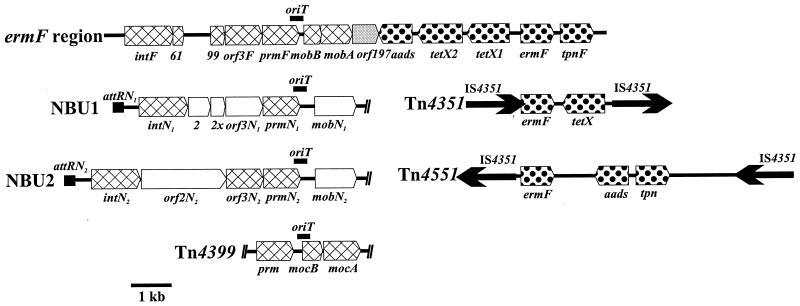

The entire inserted segment was sequenced, and the gene map of the 13-kb ermF region is shown in Fig. 3, where it is compared with maps of the genes of other MTns and nonmobilizable transposons. The IntF, Orf3F, and PrmNF proteins were most closely related to the corresponding proteins encoded by the MTns NBU1 and NBU2, although the levels of amino acid identity were not very high (26 to 45%). The MobA and MobB protein sequences exhibited the highest levels of amino acid identity to the MocA (33%) and MocB (29%) proteins encoded by genes of the MTn Tn4399. The inserted region also carries antibiotic resistance genes that encod proteins that exhibit high levels of amino acid sequence identity (95 to 100%, except for the tetX1-encoded protein) to proteins encoded by resistance genes found on Bacteroides nonmobilizable transposons Tn4351 and Tn4551 (Fig. 3). A transposase homolog encoded in this region by tnpF exhibited 42% amino acid identity over 279 amino acids to a transposase encoded by tnp on Tn4551, but the transposase encoded on Tn4551 is not the transposase of IS4351, the insertion element that mediates transposition of the transposon. The ermF region looks like a hybrid element, part of which is related to MTns and part of which is related to transposons.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the ermF region of CTnDOT with related mobilizable transposons (NBU1, NBU2, and Tn4399) and nonmobilizable transposons (Tn4351 and Tn4551) from Bacteroides. Regions of amino acid identity with proteins from MTns (cross-hatched boxes) and nonmobilizable transposons (dotted boxes) are indicated. Note that only parts of mobilizable transposons NBU1, NBU2, and Tn4399 are shown.

In the nonmobilizable transposon portion of the CTn there were two copies of the tetX gene. One of the tetX genes, tetX2, encoded a protein that was virtually identical (99.0% amino acid sequence identity over 388 amino acids) to the protein encoded by a tetX gene found on Bacteroides transposon Tn4351. However, the protein encoded by the other gene, tetX1, exhibited only 66% amino acid sequence identity to the proteins encoded by tetX2 and tetX genes.

It is interesting that neither Tn4351 nor Tn4551 alone contains all of the transposon-like genes that are present in the ermF region (Fig. 3). Tn4351 contains a copy of the tetX and ermF genes but does not contain a copy of aads or tpn. Conversely, Tn4551 contains a copy of aads, ermF, and tpn but does not contain a copy of tetX. Consequently, it is possible that the ermF region may have evolved by insertion of more than one nonmobilizable transposon. orf61, orf99, and orf297 showed no significant homology to the sequences available in the GenBank databases.

Location of the ermF region in Bacteroides strains containing CTnDOT-like elements.

From previous studies we knew that many Bacteroides strains contained CTnDOT-like elements, but we did not know whether the ermF region was located in the same position in these Bacteroides strains as in CTnDOT. All of the 19 isolates tested yielded a product that was either 368 bp long (17 isolates) or 300 bp long (2 isolates) for the right junction and a product that was either 1,024 bp long (17 isolates) or 900 bp long (2 isolates) for the left junction (Table 3). Our results indicate that the ermF region composition and position of integration are the same in independently isolated strains of Bacteroides, which suggests that the CTnDOT element may have been derived from a common ancestor. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the ermF region itself appears to have arisen by insertion of at least two different integrating elements.

TABLE 3.

Sites of integration for the ermF region in Bacteroides isolates

| Straina | Size of product (bp)

|

Element(s) presentc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ermF region left junction (primers 1 and 3)b | ermF region right junction (primers 4 and 2)b | No ermF region CTnERL product (primers 1 and 2)b | ||

| WH104 | 1,024 | 368 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| WH106 | 1,024 | 300 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| WH111 | 1,024 | 300 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| DH3925 | 1,024 | 368 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| DH3927 | 1,024 | 368 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| DH3941 | 900 | 368 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| DH4087 | 1,024 | 368 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| DH4096 | 1,024 | 368 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| DH4114 | 900 | 368 | CTnDOT | |

| DH4172 | 1,024 | 368 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| BF12256 | 1,024 | 368 | CTnDOT | |

| BFAK87 | 1,024 | 368 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| BFCEST | 1,024 | 368 | CTnDOT | |

| BFERL | 1,024 | 368 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| BTDOT | 1,024 | 368 | CTnDOT | |

| BF7397 | 1,024 | 368 | CTnDOT | |

| BF7639 | 1,024 | 368 | CTnDOT | |

| BF8223 | 1,024 | 368 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| BF8928 | 1,024 | 368 | 625 | CTnERL, CTnDOT |

| BT4107d | 1,024 | 368 | CTnDOT | |

| BT4104d | 625 | CTnERL | ||

All strains analyzed in PCR experiments were known to cross-hybridize to probes specific for tetQ, the joined left and right ends of CTnDOT, ermF, and tetX (40).

The primers utilized in these experiments are shown in Fig. 1.

It is not known whether any of the strains has two copies of either a CTnERL element or a CTnDOT element, although it is clear that many strains contain both CTnERL and CTnDOT.

Strains BT4107 and BT4104 were included as control strains for CTnDOT and CTnERL, respectively.

It is also interesting that 13 (68%) of the 19 isolates tested for ermF region junction fragments also yielded a 625-bp product with primers 1 and 2 (Fig. 1) which was amplified only if a CTnERL element was present in the same background as CTnDOT. Alternatively, a 625-bp product may have been generated if the ermF region element were able to excise from the CTnDOT element (see below).

Tests for excision and mobilization of the ermF region in B. thetaiotaomicron strains containing CTnDOT.

No excision of the ermF region was detected by either Southern blot or PCR assays. Although no circular intermediate excision product was detected, it is possible that excision is not mediated by a circular intermediate, although this seems unlikely since MTns from Bacteroides typically form a circular transposition intermediate (32). It is possible, however, that integration of nonmobilizable transposons in the right end of the NBU-like element may have disrupted functions necessary for excision of the ermF region element. Similarly, it is also possible that the putative mobilization region present in the ermF region is not functional.

In an effort to determine whether the putative mobilization genes, mobA and mobB, are functional, a plasmid containing the putative mobilization region was constructed; this plasmid was designated pGW39.1 (Table 1 and Fig. 1). pGW39.1 was mobilized from both CTnERL- and CTnDOT-containing strains of B. thetaiotaomicron, after induction with a low level of tetracycline (1 μg/ml), at frequencies of 10−5 to 10−6 transconjugant per recipient (Table 4). No mobilization (<10−9 transconjugant per recipient) was detected in the absence of tetracycline induction; the same result is obtained for the mobilization region of the MTn NBU1 when it is provided in trans. This is interesting because Bacteroides plasmids carrying mob regions from pBI143 are mobilized at a frequency of 10−6 transconjugant per recipient without tetracycline induction, but only when a CTn is present in the same background. The frequency of plasmid mobilization increases 10- to 100-fold after tetracycline induction. These observations suggest that, irrespective of whether the mob region is provided on a plasmid or integrated, mobilization of NBU-like elements may be regulated more tightly by the coresident CTn than the mobilization of plasmids carrying pBI143 or pB8-51 mob regions.

TABLE 4.

Mobilization of the ermF element mob region

| Donor strain(s) | Mobilization frequencya (transconjugant/recipient)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Tc− | Tc+ | |

| BT4100(pGW39.1) | <10−9 | NAc |

| BT4100(pGW39.1, pTC-COW) | <10−9 | <10−9 |

| BT4104(pGW39.1) | <10−9 | 10−5 |

| BT4107(pGW39.1) | <10−9 | 10−5 |

| BT4104(pLYL11) | <10−9 | 10−4 |

| BT4107(pLYL7oriTRK2) | <10−9 | <10−9 |

| BT4104(pLYL05) | 10−6 | 10−4 |

| MCR(pGW39.1), HB101(R751)b | <10−9 | <10−9 |

| MCR(pLYL7oriTRK2), HB101(R75)b | <10−9 | <10−9 |

Frequencies were calculated from a typical mating experiment by determining the number of transconjugants recovered per recipient cell at the end of the experiment. Similar results were obtained in several independent experiments. Bacteroides donor strains were cultured in the presence of tetracycline (Tc+) or in the absence of tetracycline (Tc−).

The frequencies of plasmid mobilization between Bacteroides and E. coli are the frequencies for E. coli HB101 recipients except for experiments in which E. coli EM24NR was the recipient.

NA, experiment not appropriate since the donor strain was sensitive to tetracycline.

In addition, the presence of a coresident plasmid harboring a tetracycline resistance determinant in strains that do not contain a CTn (Table 4) was not sufficient for mobilization of pGW39.1. This result demonstrated that induction of pGW39.1 mobilization by tetracycline is dependent on a coresident CTnERL or CTnDOT element and not on exposure to tetracycline alone.

NBU MTns and other MTns are unusual in that their mobilization regions are recognized by E. coli IncP plasmids, such as RP4 (IncPα) and R751 (IncPβ) (21). The ability of pGW39.1 to be mobilized between E. coli strains by an IncP plasmid was also investigated. The IncPβ plasmid R751 was not able to mobilize pGW39.1 from E. coli DH5αMCR to E. coli EM24R. It is possible that the ermF mob genes are not expressed in E. coli and consequently cannot initiate mobilization in an E. coli host.

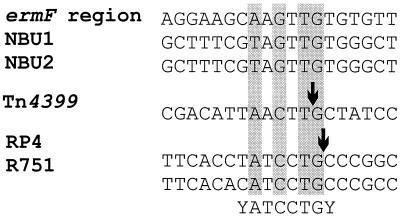

Given that the ermF element mob region is functional and given the sequence similarity between the mobilization regions of the ermF region element and those of other MTns, sequences were compared in order to identify the putative oriT region in the mob region of the ermF element. The nic site for Tn4399 has recently been determined (27) and is shown in Fig. 4. A similar sequence was found in the ermF mob region and is located between prmNF and mobB. This is interesting because the putative oriT regions of NBU1 and NBU2 have also been localized to the C-terminal ends of prmNF homologs (prmN1 and prmN2, respectively) (20, 21). Putative nic sites were also identified in these oriT regions and between the prmN and mobN genes, but these sites have not been confirmed experimentally.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the putative nic sites of the mob region from the ermF region of CTnDOT, NBU1, and NBU2 and the determined nic sites of Tn4399, RP4, and R751. Nucleotide positions conserved in the family of oriT sequences are indicated by gray shading, and cleavage sites that have been determined are indicated by arrows. The consensus sequence described for the RP4 family of oriT nic sites is shown below the aligned sequences. GenBank accession numbers are as follows: NBU1, AF238307; NBU2, AF251288; RP4, L27758; and R751, X54458.

DISCUSSION

This is the first report of an MTn that has entered a CTn and is now moving as part of the CTn. Our results show that insertion of the ermF gene region occurred in a region of a CTnERL-like element that is immediately downstream of orf2 and immediately upstream of a region known to be essential for CTn excision (7, 8). Although in a separate study we found that orf2 has no role in integration or excision of the CTn, it was possible that insertion in this region could alter regulation of genes located immediately downstream of orf2, which do have a role in CTn excision (7, 8). We confirmed that CTnDOT transfers as well as CTnERL from B. thetaiotaomicron donors to B. thetaiotaomicron recipients (10−5 to 10−6 transconjugant per recipient), and therefore, insertion in the region immediately downstream of orf2 has no apparent adverse effect on the ability of the CTn to excise and transfer.

The CTnDOT type of element was rare in Bacteroides strains before 1970, but this type is now found in 10% of Bacteroides strains that belong to a number of species. CTnERL elements were found in 20 to 30% of Bacteroides strains before 1970, and now at least 60% of Bacteroides strains contain at least one copy of CTnERL (40). A further 10% of Bacteroides strains contain elements that cross-hybridize to the ends of CTnDOT/CTnERL-like elements but do not contain either erythromycin or tetracycline resistance determinants. The simplest explanation for the appearance of CTnDOT is that a CTnERL element acquired the ermF region, possibly in multiple steps; one of the steps could have been entry of an NBU type of MTn, and at least one but perhaps more involving a nonmobilizable transposon. Then CTnDOT spread widely to many different Bacteroides species. This is a clinically significant event because clindamycin was once a drug of choice for treating anaerobic infections, including those caused by Bacteroides, but the ermF gene, which confers resistance to clindamycin as well as to erythromycin, has made clindamycin much less effective (31).

In Bacteroides spp. CTns have made a significant contribution to the spread of tetracycline resistance, and now CTns may also be driving dissemination of the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) type of resistance via transmission of CTnDOT-like elements and also via the spread of other elements. Most of the antibiotic resistance present in the Bacteroides group is attributable to antibiotic resistance determinants carried by the CTns themselves. However, Bacteroides CTns can also mobilize coresident plasmids in cis or in trans and also stimulate excision and transfer of unlinked MTns (NBU2 and Tn4551) which are also known to harbor resistance determinants (48, 53). In a recent survey of 290 Bacteroides strains, 24% of the strains were found to be carrying erythromycin resistance genes. A total of 80% of the resistance was attributable to the erm type of resistance, including ermF (59%) carried by CTnDOT-like elements (48%) or Bacteroides transposons (Tn4351, Tn4551) (11%), ermG (13%), and ermB (8%). However, for the remaining 20% of erythromycin-resistant strains, the resistance phenotype was not attributable to the ermA, ermB, ermC, ermF, ermG, or ermQ gene (40), and so the source of antibiotic resistance remains to be determined.

Our results also indicate that the majority (68%) of community and clinical isolates contain both a CTnERL element and a CTnDOT-like element (Table 3). This probably reflects selection of the MLSB type of resistance in a Bacteroides population in which CTnERL is already well represented. However, there may be some other advantage in harboring more than one copy of a CTnDOT or CTnERL element, particularly if there is a linear relationship between the level of CTn excision and the level of transfer and therefore spread. However, we did not observe a detectable increase in the level of transfer under the laboratory conditions utilized for conjugal transfer. This failure to detect an increase in the level of CTnDOT transfer may have been due to a limitation in the sensitivity of the transfer assay, since it is difficult to detect differences in conjugal transfer, a multistep process, of less than 10-fold. Differences of less than 10-fold may still be significant for Bacteroides spp. in vivo, and laboratory conditions may not reflect the in vivo situation.

In all of the Bacteroides strains assayed, the ermF region appeared to be integrated in the same region of the CTnDOT element. Primer sets were designed that were specific for both the right and left junctions of the ermF region and therefore both the MTn component (right) and the composite transposon component (left). In every Bacteroides isolate analyzed, a product was obtained for each junction. This suggests that the compositions of the ermF region are very similar if not identical in all strains of Bacteroides containing CTnDOT. Therefore, the CTnDOT-like elements present in the Bacteroides population, diverse as it is (6, 17, 18), are likely to have been derived from a common ancestor.

The ermF region did not excise and circularize under any of the conditions which we tested. If a transposon had inserted into one end of the NBU-like element, it could very well have abolished excision by disrupting one of the ends of the NBU element. Alternatively, the ermF region may not excise and form a circular transfer intermediate, although this seems unlikely given that all related MTns characterized so far do form such a transfer intermediate.

Although excision functions appear to be inactive, the mobilization genes of the ermF region are still active. The presence of two active mobilization regions in CTnDOT would be expected to make the CTn somewhat prone to deletions, although other composite elements that contain two active mobilization regions have been described elsewhere (50). When two oriT regions are present in a plasmid, deletions of the region between the oriT regions occur (2, 24). The directionality of transfer from the ermF region oriT and the directionality of transfer from the original CTn oriT are not known. It is possible that they are opposite. If so, transfer from one might preclude transfer from the other. Whatever the case, transfer of CTnDOT itself is still as efficient as transfer of CTnERL, in which only one oriT and one set of mobilization genes have been found so far.

It is odd that the ermF region of CTnDOT contains two copies of tetX, because tetX confers tetracycline resistance on aerobically grown E. coli but not on Bacteroides because the gene encodes an enzyme that uses oxygen to inactivate tetracycline (44). The origin of this gene is not known, but the gene is presumed to have come from some genus other than Bacteroides, since Bacteroides species are obligate anaerobes. Alternatively, the gene might have an oxygen-independent function in Bacteroides that has not been discovered. The fact that a gene that has a very divergent sequence (tetX1) has now been found raises the possibility that this gene is more widespread in nature than was previously thought to be the case. Similarly, the aads gene, which encodes a streptomycin resistance determinant, does not appear to provide a significant benefit to its Bacteroides host, because Bacteroides spp. are naturally resistant to aminoglycoside antibiotics.

In summary, our results suggest that the CTnDOT-like elements appear to have evolved from a single CTnERL element that acquired at least two other Bacteroides mobile elements, one of which contained ermF. Although the elements that make up the ermF region of the CTnDOT element do not appear to be able to excise from the host element, the mobilization region appears to be functional. Our results also indicate that the CTnDOT-like elements (which are now present in 10% of the diverse Bacteroides population) from various sources in the United States appear to have been derived from a common ancestor. This further illustrates the pervasiveness of the CTnERL-CTnDOT family of CTns and their significant role in horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance determinants in the Bacteroides group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rebecca Alavi for preliminary mapping of the ermF region of CTnDOT compared with CTnERL by Southern blot comparison. We also thank Laura Bedzyk for sequencing p6E2 and p6E3.

This work was supported by grant AI22383 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayoubi P, Kilic A O, Vijayakumar M N. Tn5253, the pneumococcal omega (cat tet) BM6001 element, is a composite structure of two conjugative transposons, Tn5251 and Tn5252. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1617–1622. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1617-1622.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett M M, Erickson J M, Meyer R J. Recombination between directly repeated origins of conjugative transfer cloned in M13 bacteriophage DNA models ligation of the transferred plasmid strand. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3579–3586. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedzyk L A, Shoemaker N B, Young K E, Salyers A A. Insertion and excision of Bacteroides conjugative chromosomal elements. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:166–172. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.166-172.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonheyo G, Graham D, Shoemaker N B, Salyers A A. Transfer region of a Bacteroides conjugative transposon, CTnDOT. Plasmid. 2001;45:41–51. doi: 10.1006/plas.2000.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer H B, Roulland-Dussoix D. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification system of DNA in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1969;41:459–472. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradbury W C, Murray R G, Mancini C, Morris V L. Bacterial chromosomal restriction endonuclease analysis of the homology of Bacteroides species. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:24–28. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.1.24-28.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng Q, Paszkiet B J, Shoemaker N B, Gardner J F, Salyers A A. Integration and excision of a Bacteroides conjugative transposon, CTnDOT. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4035–4043. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.14.4035-4043.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng, Q., Y. Sutanto, N. B. Shoemaker, J. F. Gardner, and A. Salyers. Identification of genes required for excision of CTnDOT, a Bacteroides conjugative transposon. Mol. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Crellin P K, Rood J I. Tn4451 from Clostridium perfringens is a mobilizable transposon that encodes the functional Mob protein, TnpZ. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:631–642. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franco A A, Cheng R K, Chung G-T, Wu S, Oh H-B, Sears C L. Molecular evolution of the pathogenicity island of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis strains. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6623–6633. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.21.6623-6633.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franke A E, Clewell D B. Evidence for a chromosome-borne resistance transposon (Tn916) in Streptococcus faecalis that is capable of conjugal transfer in the absence of a conjugative plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:494–502. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.494-502.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner R G, Russell J B, Wilson D B, Wang G-R, Shoemaker N B. Use of a modified Bacteroides-Prevotella shuttle vector to transfer a reconstructed β-1,4-d-endogluconase gene into Bacteroides uniformis and Prevotella ruminicola B14. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:196–202. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.196-202.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hecht D W, Malamy M H. Tn4399, a conjugal mobilizing transposon of Bacteroides fragilis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3603–3608. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3603-3608.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochhut B, Jahreis K, Lengeler J W, Schmid K. CTnscr94, a conjugative transposon found in enterobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2097–2102. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2097-2102.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holdeman L V, Moore W E C. Anaerobe laboratory manual. 4th ed. Blacksburg: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jobanputra R S, Datta N. Trimethoprim R-factor in enterobacteria from clinical specimens. J Med Microbiol. 1974;7:169–177. doi: 10.1099/00222615-7-2-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson J L. Taxonomy of the Bacteroides. Deoxyribonucleic acid homologies among Bacteroides fragilis and other saccharolytic Bacteroides species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1978;28:245–256. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson J L, Harich B. Ribosomal ribonucleic acid homology among species of the genus Bacteroides. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1986;36:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Bouguenec C, de Cespedes G, Horaud T. Presence of chromosomal elements resembling the composite structure Tn3701 in streptococci. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:727–734. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.727-734.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li L Y, Shoemaker N B, Salyers A A. Characterization of the mobilization region of a Bacteroides insertion element (NBU1) that is excised and transferred by Bacteroides conjugative transposons. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6588–6598. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6588-6598.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li L Y, Shoemaker N B, Wang G R, Cole S P, Hashimoto M K, Wang J, Salyers A A. The mobilization regions of two integrated Bacteroides elements, NBU1 and NBU2, have only a single mobilization protein and may be on a cassette. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3940–3945. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3940-3945.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyras D, Rood J I. Transposition of Tn4451 and Tn4453 involves a circular intermediate that forms a promoter for the large resolvase, TnpX. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:588–601. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyras D, Storie C, Huggins A S, Crellin P K, Bannam T L, Rood J I. Chloramphenicol resistance in Clostridium difficile is encoded on Tn4453 transposons that are closely related to Tn4451 from Clostridium perfringens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1563–1567. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer R. Site-specific recombination at oriT of plasmid R1162 in the absence of conjugative transfer. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:799–806. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.799-806.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer R J, Shapiro J A. Genetic organization of the broad-host-range IncP-1 plasmid R751. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:1362–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.3.1362-1373.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullany P, Wilks M, Tabaqchali S. Transfer of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLS) resistance in Clostridium difficile is linked to a gene homologous with toxin A and is mediated by a conjugative transposon, Tn5398. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:305–315. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy C, Malamy M. Requirements for strand- and site-specific cleavage within the oriT region of Tn4399, a mobilizing transposon from Bacteroides fragilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3158–3165. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3158-3165.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rauch P J, De Vos W M. Characterization of the novel nisin-sucrose conjugative transposon Tn5276 and its insertion in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1280–1287. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1280-1287.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravatn R, Studer S, Zehnder A J B, van der Meer J R. Int-B13, an unusual site-specific recombinase of the bacteriophage P4 integrase family, is responsible for chromosomal insertion of the 105-kilobase clc element of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5505–5514. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5505-5514.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saito H, Miura K I. Preparation of transforming deoxy-ribonucleic acid by phenol treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1963;72:619–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salyers A A, Shoemaker N B. Resistance gene transfer in anaerobes: new insights, new problems. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(Suppl. 1):S36–S43. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.supplement_1.s36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salyers A A, Shoemaker N B, Stevens A M, Li L Y. Conjugative transposons: an unusual and diverse set of integrated gene transfer elements. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:579–590. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.579-590.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott K, Barbosa T, Forbes K, Flint H. High-frequency transfer of a naturally occurring chromosomal tetracycline resistance element in the ruminal anaerobe Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3405–3411. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3405-3411.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shoemaker N, Wang G, Salyers A. NBU1, a mobilizable site-specific integrated element from Bacteroides spp., can integrate nonspecifically in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3601–3607. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3601-3607.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoemaker N B, Barber R D, Salyers A A. Cloning and characterization of a Bacteroides conjugal tetracycline-erythromycin resistance element by using a shuttle cosmid vector. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1294–1302. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1294-1302.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shoemaker N B, Getty C, Guthrie E P, Salyers A A. Regions in Bacteroides plasmids pBFTM10 and pB8-51 that allow Escherichia coli-Bacteroides shuttle vectors to be mobilized by IncP plasmids and by a conjugative Bacteroides tetracycline resistance element. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:959–965. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.3.959-965.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shoemaker N B, Guthrie E P, Salyers A A, Gardner J F. Evidence that the clindamycin-erythromycin resistance gene of Bacteroides plasmid pBF4 is on a transposable element. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:626–632. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.2.626-632.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shoemaker N B, Salyers A A. Tetracycline-dependent appearance of plasmidlike forms in Bacteroides uniformis 0061 mediated by conjugal Bacteroides tetracycline resistance elements. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1651–1657. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1651-1657.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shoemaker N B, Vlamakis H, Hayes K, Salyers A A. Evidence for extensive resistance gene transfer among Bacteroides spp. and among Bacteroides and other genera in the human colon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:561–568. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.561-568.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shoemaker N B, Wang G R, Stevens A M, Salyers A A. Excision, transfer, and integration of NBU1, a mobilizable site-selective insertion element. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6578–6587. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6578-6587.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith C J, Macrina F L. Large transmissible clindamycin resistance plasmid in Bacteroides ovatus. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:739–741. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.2.739-741.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith C J, Parker A C. Identification of a circular intermediate in the transfer and transposition of Tn4555, a mobilizable transposon from Bacteroides spp. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2682–2691. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2682-2691.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Speer B S, Bedzyk L, Salyers A A. Evidence that a novel tetracycline resistance gene found on two Bacteroides transposons encodes an NADP-requiring oxidoreductase. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:176–183. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.176-183.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sullivan J T, Ronson C W. Evolution of rhizobia by acquisition of a 500-kb symbiosis island that integrates into a phe-tRNA gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5145–5149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tally F P, Snydman D R, Shimell M J, Malamy M H. Characterization of pBFTM10, a clindamycin-erythromycin resistance transfer factor from Bacteroides fragilis. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:686–691. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.2.686-691.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tribble G, Parker A, Smith C. The Bacteroides mobilizable transposon Tn4555 integrates by a site-specific recombination mechanism similar to that of the gram-positive bacterial element Tn916. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2731–2739. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2731-2739.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tribble G D, Parker A C, Smith C J. Genetic structure and transcriptional analysis of a mobilizable, antibiotic resistance transposon from Bacteroides. Plasmid. 1999;42:1–12. doi: 10.1006/plas.1999.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vedantam G, Novicki T J, Hecht D W. Bacteroides fragilis transfer factor Tn5520: the smallest bacterial mobilizable transposon containing single integrase and mobilization genes that function in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2564–2571. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2564-2571.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vijayakumar M N, Ayoubi P, Kilic A O. Organization of Tn5253, the pneumococcal Ω (cat tet) BM6001 element. In: Dunny G M, Cleary P P, McKay L L, editors. Genetics and molecular biology of streptococci, lactococci, and enterococci. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1991. pp. 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waldor M K, Tschape H, Mekalanos J J. A new type of conjugative transposon encodes resistance to sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, and streptomycin in Vibrio cholerae O139. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4157–4165. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4157-4165.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang H, Roberts A P, Lyras D, Rood J I, Wilks M, Mullany P. Characterization of the ends and target sites of the novel conjugative transposon Tn5397 from Clostridium difficile: excision and circularization is mediated by the large resolvase, TndX. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3775–3783. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.13.3775-3783.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J, Shoemaker N B, Wang G R, Salyers A A. Characterization of a Bacteroides mobilizable transposon, NBU2, which carries a functional lincomycin resistance gene. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3559–3571. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.12.3559-3571.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whittle G, Bloomfield G A, Katz M E, Cheetham B F. The site-specific integration of genetic elements may modulate thermostable protease production, a virulence factor in Dichelobacter nodosus, the causative agent of ovine footrot. Microbiology. 1999;145:2845–2855. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-10-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]