Abstract

To address inborn errors of immunity (IEI) which were underdiagnosed in resource-limited regions, our centre developed and offered free genetic testing for the most common IEI by Sanger sequencing (SS) since 2001. With the establishment of The Asian Primary Immunodeficiency (APID) Network in 2009, the awareness and definitive diagnosis of IEI were further improved with collaboration among centres caring for IEI patients from East and Southeast Asia. We also started to use whole exome sequencing (WES) for undiagnosed cases and further extended our collaboration with centres from South Asia and Africa. With the increased use of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), we have shifted our diagnostic practice from SS to WES. However, SS was still one of the key diagnostic tools for IEI for the past two decades. Our centre has performed 2,024 IEI SS genetic tests, with in-house protocol designed specifically for 84 genes, in 1,376 patients with 744 identified to have disease-causing mutations (54.1%). The high diagnostic rate after just one round of targeted gene SS for each of the 5 common IEI (X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) 77.4%, Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome (WAS) 69.2%, X-linked chronic granulomatous disease (XCGD) 59.5%, X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (XSCID) 51.1%, and X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM1) 58.1%) demonstrated targeted gene SS should remain the first-tier genetic test for the 5 common X-linked IEI.

Keywords: inborn errors of immunity, primary immunodeficiency diseases, targeted gene, Sanger sequencing, whole exome sequencing, next generation sequencing

Introduction

Inborn errors of immunity (IEI), previously known as primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDD), arise from intrinsic defects in immunity, with most due to genetic mutations, and comprise over 400 diseases that could present with a diverse range of disorders including infection, autoimmunity, inflammation, malignancy, and allergy (1, 2). These multitudes of disorders could present with a wide spectrum of phenotypes of varying severities, resulting in difficulty recognising and diagnosing IEI promptly and accurately, especially in resource-limited countries and regions (3).

With rapid advance in both immunological and genetic studies in IEI including newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) over the last 20 years, the prognosis of patients with IEI living in resource-rich countries and regions have improved enormously due to rapid and accurate genetic diagnosis with treatment tailored to specific IEI, together with family counseling regarding recurrence risk and reproductive choices (3–5). However, for most countries and regions of Asia and Africa, many patients with suspected IEI now still do not have ready access to these diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, let alone 20 years ago, resulting in underdiagnosis of IEI and a protracted diagnostic odyssey for many families (6).

To improve awareness and recognition of IEI in our region, we started to offer e-consultation and genetic investigations free of charge for patients suspected to have IEI referred to us by our collaborators since 2001. This was built on our paediatric immunology service started in 1988, with us having rapidly acquired the in-house capacity to diagnose IEI genetically and treat the more common IEI effectively (7–17). With more experience, we started to offer the research based targeted gene Sanger sequencing (SS) for the 5 common X-linked IEI, namely X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS), X-linked chronic granulomatous disease (XCGD), X-linked hyper-IgM (HIGM1) and X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (XSCID), to our collaborators in South-East Asia and mainland China initially, followed by those in South Asia and Africa. The collaboration has resulted in providing accurate genetic diagnosis leading to appropriate management of these patients as well as increasing awareness of IEI in these countries and regions (18–31).

Over the years, we have increased the number of targeted genes subjected to SS to more than 80, as well as helped our collaborators in setting up their local genetic diagnostic service through sharing of protocols and primers, resulting in local centres with expertise and diagnostics for IEI without the need to refer patients with suspected IEI to us for genetic diagnosis (32–42).

Since 2009, we started to use next generation sequencing (NGS) to investigate patients with suspected IEI whose genetic mutations could not be identified by targeted gene SS. In the same year, we established the Asian Primary Immunodeficiency (APID) Network to provide an electronic platform for both data management and better consultative service for our collaborators (43, 44).

In this study, we aimed to review the role of targeted gene SS in the diagnostic pathway for patients with suspected IEI referred to us from 2001 to 2021, to define which suspected IEI should be subjected to targeted gene SS before offering NGS, with criteria that the gene is the most commonly found to be causal among all the genes that are associated with that clinical phenotype, and with at least a 50% diagnostic rate using one round of SS.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Patients with suspected IEI referred to us from different centres over a 20-year period (2001–2021) were included. Various diagnostic work up including laboratory tests and immunological assays were done in the referring centres. Referring clinicians would send us the clinical details and laboratory findings, which would be deposited in our APID network database. Only those patients with clinical presentation indicative of IEI would be followed up (currently can refer to the IUIS phenotypic classification) (2). Cases with HIV infection or other known causes of immune compromise would be excluded. One or several rounds of e-consultation would be conducted between the referring clinicians and the corresponding author who ultimately decided on which targeted gene SS would be done, with clinical and laboratory criteria specific to each top X-linked gene applied listed here below. X-linked genes would be normally sequenced in boys born of non-consanguineous marriages with a non-conflicting family history only, e.g., without affected sisters. Onset of recurrent bacterial infections or enteroviral infections approximately after 6 months of age, and if available, very low IgG level and B cell count would prompt the immediate sequencing of the BTK gene. The WAS gene was sequenced in boys with recurrent bacterial, viral, and fungal infections, eczema, and importantly, thrombocytopenia. The CYBB gene would be sequenced in boys with recurrent bacterial and fungal infections, BCGitis or BCGosis, and if available, a positive nitroblue tetrazolium test (NBT) or dihydrorhodamine (DHR) 123 test. The IL2RG gene was sequenced in boys presenting in first few months of life with recurrent severe infections, low absolute lymphocyte count, and if available, a very low T or NK cell count. The CD40LG gene was sequenced in boys with recurrent sinopulmonary infections, liver and biliary tract disease, and if available, a high IgM level accompanied by low IgG and IgA levels. Additional or more advanced laboratory investigations were normally not requested before proceeding to genetic testing as most patients were referred from resource-limited settings. Less than 5% of referral cases were not offered genetic testing due to insufficient clinical details. Once genomic DNA were received, genetic diagnosis by research-based targeted gene SS was then performed by our centre free of charge. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Review Board of The University of Hong Kong and Queen Mary Hospital (Ref. no. UW 08-301).

Targeted Gene SS

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood of patients by different centres, with consent obtained from parents or guardians before blood collection. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primer pairs covering entire coding region and flanking splice sites were designed for individual IEI genes. Research-based targeted gene SS was performed by PCR or long PCR direct SS of both sense and antisense strands of DNA as described in our previous studies (19, 20, 22–25). Homology analyses with reference sequences were performed by Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). Mutations, identified by bioinformatics analysis, were described with reference to Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) nomenclature (45). For those patients with typical phenotypes including the 5 common IEI, relevant single targeted gene SS has been offered in the first round of screening, e.g., BTK(Bruton tyrosine kinase) gene for XLA, WAS (WASP actin nucleation promoting factor) gene for WAS, CYBB (cytochrome b-245 beta chain) gene for XCGD, IL2RG (interleukin 2 receptor subunit gamma) gene for XSCID and CD40LG (CD40 ligand) gene for XHIM. For the other IEI, targeted gene or gene panel SS were offered at the same time. Further targeted gene tests were performed if no causal mutation identified in the previous round of SS.

Results

From 2001 to 2021, 1,376 patients with suspected IEI have been referred from different centres as shown in Figure 1 . We have developed 84 different IEI targeted gene tests according to the diversity of IEI cases referred. Totally, we have performed 2,024 targeted gene SS for all these IEI patients referred, with 744 patients identified to have disease-causing mutations. The positive diagnostic rates among patients and tests are 54.1% (744 out of 1,376 patients) and 36.8% (744 out of 2,024 SS) respectively, with 1.47 SS performed per patient on average. The details of the mutations were described in the Tables 1 – 4 , and Supplementary Tables 1, 2 . Tables 1 – 4 , and Supplementary Table 1 show all causal mutations found in the corresponding genes of the 5 common IEI while Supplementary Table 2 for all other IEI genes.

Figure 1.

Map showing 72 referring centres in 17 countries. (Created with Datawrapper).

Table 1.

Causal mutations identified in WAS gene (Reference Sequence LRG_125) of the WAS patients.

| Patient ID | Gene | Mutant allele | cDNA/nucleotide change | Protein change | Mutant type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WAS-016A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.35G>C LRG_125t1:c.62del |

G12A N21Tfs*24 |

Missense Frameshift |

| WAS-051A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.58C>T | Q20X | Missense |

| WAS-149A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.91G>A | E31K | Missense |

| WAS-039A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.116T>G | L39R | Missense |

| WAS-083A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.134C>T | T45M | Missense |

| WAS-102A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.134C>T | T45M | Missense |

| WAS-088A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.167C>T | A56V | Missense |

| WAS-056A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.190T>A | W64R | Missense |

| WAS-025A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.217T>C | C73R | Missense |

| WAS-045A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.218G>A | C73Y | Missense |

| WAS-055A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.223G>A | V75M | Missense |

| WAS-048A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.245C>A | S82Y | Missense |

| WAS-121A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.256C>T | R86C | Missense |

| WAS-030A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.257G>A | R86H | Missense |

| WAS-082A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.257G>A | R86H | Missense |

| WAS-101A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.257G>A | R86H | Missense |

| WAS-137A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.257G>A | R86H | Missense |

| WAS-148A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.257G>A | R86H | Missense |

| WAS-044A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.257G>T | R86L | Missense |

| WAS-097A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.300G>C | E100D | Missense |

| WAS-070A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.397G>A | E133K | Missense |

| WAS-131A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.397G>A | E133K | Missense |

| WAS-136A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.397G>A | E133K | Missense |

| WAS-151A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.397G>A | E133K | Missense |

| WAS-001A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1354G>T | E452X | Missense |

| WAS-049A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1376C>T LRG_125t1:c.1421T>A |

P459L M474K |

Missense Missense |

| WAS-071A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1378C>T | P460S | Missense |

| WAS-154A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.97C>T | Q33* | Nonsense |

| WAS-110A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.100C>T | R34* | Nonsense |

| WAS-152A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.100C>T | R34* | Nonsense |

| WAS-160A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.100C>T | R34* | Nonsense |

| WAS-123A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.107_108del | F36* | Nonsense |

| WAS-029A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.121C>T | R41* | Nonsense |

| WAS-078A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.121C>T | R41* | Nonsense |

| WAS-112A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.121C>T | R41* | Nonsense |

| WAS-128A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.184G>T | E62* | Nonsense |

| WAS-050A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.290G>A | W97* | Nonsense |

| WAS-100A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.100C>T | R34* | Nonsense |

| WAS-119A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.306C>G | Y102* | Nonsense |

| WAS-158A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.403C>T | Q135* | Nonsense |

| WAS-106A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.454C>T | Q152* | Nonsense |

| WAS-006A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.472C>T | Q158* | Nonsense |

| WAS-023A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.631C>T | R211* | Nonsense |

| WAS-028A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.631C>T | R211* | Nonsense |

| WAS-033A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.631C>T | R211* | Nonsense |

| WAS-087A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.631C>T | R211* | Nonsense |

| WAS-107A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.631C>T | R211* | Nonsense |

| WAS-124A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.631C>T | R211* | Nonsense |

| WAS-126A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.631C>T | R211* | Nonsense |

| WAS-127A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.631C>T | R211* | Nonsense |

| WAS-018A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.995dup | N335* | Nonsense |

| WAS-117A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1317_1318delinsTT | Q440* | Nonsense |

| WAS-138A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1336A>T | K446* | Nonsense |

| WAS-125A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.330dup | T111Hfs*11 | Frameshift |

| WAS-004A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.350del | F117Sfs*10 | Frameshift |

| WAS-034A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.410_419del | F137Sfs*121 | Frameshift |

| WAS-155A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.431_432insT | K144Nfs*25 | Frameshift |

| WAS-032A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.436del | Q146Kfs*115 | Frameshift |

| WAS-072A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.442dup | R148Kfs*21 | Frameshift |

| WAS-094A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.472_473dup | Q158Hfs*104 | Frameshift |

| WAS-019A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.566del | P189Qfs*72 | Frameshift |

| WAS-015A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.587_588del | G196Afs*10 | Frameshift |

| WAS-002A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.649_652dup | P218fs*5 | Frameshift |

| WAS-003A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.649_652dup | P218fs*5 | Frameshift |

| WAS-021A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.647_659dup | P222Tfs*4 | Frameshift |

| WAS-113A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.665dup | A223Sfs*2 | Frameshift |

| WAS-027A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.735del | K245Nfs*16 | Frameshift |

| WAS-008A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.950del | P317Hfs*128 | Frameshift |

| WAS-059A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1001del | G334Vfs*111 | Frameshift |

| WAS-010A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1006_1007del | K336Gfs*158 | Frameshift |

| WAS-058A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1023_1024del | L342Afs*152 | Frameshift |

| WAS-156A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1052dup | P352Tfs*143 | Frameshift |

| WAS-012A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1092del | G366Afs*79 | Frameshift |

| WAS-084A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1143del | P383Lfs*62 | Frameshift |

| WAS-141A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1190del LRG_125t1:c.1188_1199del |

P397Rfs*48 P401_P404del |

Frameshift In-frame Deletion/Insertion |

| WAS-057A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1219_1235dup | P413Gfs*38 | Frameshift |

| WAS-007A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1265_1275del | A422Gfs*69 | Frameshift |

| WAS-118A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1271dup | L425Pfs70 | Frameshift |

| WAS-099A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1295del | G432Efs*13 | Frameshift |

| WAS-011A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.120_132+1dup | Splicing | |

| WAS-009A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.132+1G>T | Splicing | |

| WAS-075A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.133-1G>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-047A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.687G>T | G229= | Splicing |

| WAS-120A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.274-2A>C | Splicing | |

| WAS-031A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.360+1G>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-129A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.360+5G>C | Splicing | |

| WAS-040A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.361-7T>G | Splicing | |

| WAS-109A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.361-1G>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-096A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.559+1G>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-115A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.559+2T>C | Splicing | |

| WAS-063A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.734+2T>C | Splicing | |

| WAS-020A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.735-1G>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-024A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.735-1G>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-150A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.735-1G>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-054A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.777+1G>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-114A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.777+1G>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-134A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.777+1G>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-133A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.777+2dup | Splicing | |

| WAS-061A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.777+3G>C | Splicing | |

| WAS-014A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.777+3_777+6del | Splicing | |

| WAS-130A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.777+3_777+6del | Splicing | |

| WAS-013A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.931+2T>C | Splicing | |

| WAS-104A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1338+1G>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-139A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1338+2T>G | Splicing | |

| WAS-022A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1453+1G>C | Splicing | |

| WAS-111A | WAS | X-linked | LRG_125t1:c.1453+2T>A | Splicing | |

| WAS-103A | WAS | X-linked | EX1-EX2del LRG_125t1:c.1378C>T |

P460S | Gross Deletion Missense |

| WAS-089A | WAS | X-linked | EX1-EX12del | Gross Deletion |

Repeated mutations are in bold. WAS, WASP actin nucleation promoting factor; WAS, Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome. *translation termination (stop) codon.

Table 4.

Causal mutations identified in CD40LG gene (Reference Sequence LRG_141) of the HIGM1 patients.

| Patient ID | Gene | Mutant allele | cDNA/nucleotide change | Protein Change | Mutant Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XHIM-061A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.346G>T | G116C | Missense |

| XHIM-020A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.418T>G | W140G | Missense |

| XHIM-030A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.430G>A | G144R | Missense |

| XHIM-025A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.482T>A | L161Q | Missense |

| XHIM-050A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.676G>A | G226R | Missense |

| XHIM-029A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.680G>A | G227E | Missense |

| XHIM-049A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.692T>G | L231W | Missense |

| XHIM-037A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.761C>T | T254M | Missense |

| XHIM-058A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.761C>T | T254M | Missense |

| XHIM-047A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.415C>T | Q139* | Nonsense |

| XHIM-011A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.419G>A | W140* | Nonsense |

| XHIM-014A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.420G>A | W140* | Nonsense |

| XHIM-001A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.654C>A | C218* | Nonsense |

| XHIM-022A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.654C>A | C218* | Nonsense |

| XHIM-010A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.103del | Q35Rfs*2 | Frameshift |

| XHIM-004A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.291_299delinsG | D97Efs*13 | Frameshift |

| XHIM-024A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.511_512del | I171Lfs*29 | Frameshift |

| XHIM-017A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.158_161del | I53Kfs*13 | Frameshift |

| XHIM-054A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.158_161del | I53Kfs*13 | Frameshift |

| XHIM-052A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.489del | R165Dfs*26 | Frameshift |

| XHIM-016A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.599del | R200Nfs*42 | Frameshift |

| XHIM-002A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.616_619del | L206Efs*35 | Frameshift |

| XHIM-003A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.719_720del | N240Sfs*3 | Frameshift |

| XHIM-019A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.157-2A>G | Splicing | |

| XHIM-021A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.410-2A>G | Splicing | |

| XHIM-036A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.289-28_302del | Splicing | |

| XHIM-051A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.156+1G>A | Splicing | |

| XHIM-053A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.346+2T>A | Splicing | |

| XHIM-056A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.289-1G>C | Splicing | |

| XHIM-057A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.347-1G>C | Splicing | |

| XHIM-007A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.289-2A>G | Splicing | |

| XHIM-009A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.289-2A>G | Splicing | |

| XHIM-055A | CD40LG | X-linked | EX1_EX2del | Gross Deletion | |

| XHIM-005A | CD40LG | X-linked | EX1_EX5del | Gross Deletion | |

| XHIM-008A | CD40LG | X-linked | EX1_EX5del | Gross Deletion | |

| XHIM-018A | CD40LG | X-linked | LRG_141t1:c.288+259_409+652delinsTCGT | Gross Deletion |

Repeated mutations are in bold. CD40LG, CD40 ligand; HIGM1, X-linked immunodeficiency with hyper-IgM type 1. *translation termination (stop) codon.

Table 2.

Causal mutations identified in CYBB gene (Reference Sequence LRG_53) of the XCGD patients.

| Patient ID | Gene | Mutant allele | cDNA/nucleotide change | Protein change | Mutant type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XCGD-110A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.-65C>T | Regulatory | |

| XCGD-072A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.376T>C | C126R | Missense |

| XCGD-018A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.577T>C | S193P | Missense |

| XCGD-004A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.613T>A | F205I | Missense |

| XCGD-044A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.626A>G | H209R | Missense |

| XCGD-077A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.665A>G | H222R | Missense |

| XCGD-062A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.911C>G EX11-EX13del |

P304R | Missense Gross Deletion |

| XCGD-067A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.925G>A | E309K | Missense |

| XCGD-013A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.935T>A | M312K | Missense |

| XCGD-145A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.985T>C | C329R | Missense |

| XCGD-058A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1014C>A | H338Q | Missense |

| XCGD-060A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1016C>A | P339H | Missense |

| XCGD-111A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1022C>T | T341I | Missense |

| XCGD-008A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1025T>A | L342Q | Missense |

| XCGD-125A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1075G>A | G359R | Missense |

| XCGD-121A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1154T>G | I385R | Missense |

| XCGD-038A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1234G>A | G412R | Missense |

| XCGD-078A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1244C>T | P415L | Missense |

| XCGD-005A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1498G>C | D500H | Missense |

| XCGD-136A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1546T>C | W516R | Missense |

| XCGD-103A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1548G>C | W516C | Missense |

| XCGD-043A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1583C>G | P528R | Missense |

| XCGD-120A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.84G>A | W28* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-106A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.123C>G | Y41* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-128A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.217C>T | R73* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-095A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.271C>T | R91* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-142A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.388C>T | R130* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-029A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.469C>T | R157* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-074A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.469C>T | R157* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-101A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.469C>T | R157* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-032A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.676C>T | R226* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-076A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.676C>T | R226* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-107A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.676C>T | R226* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-137A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.676C>T | R226* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-138A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.676C>T | R226* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-019A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.868C>T | R290* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-084A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.868C>T | R290* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-108A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.868C>T | R290* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-147A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.868C>T | R290* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-080A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1328G>A | W443* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-059A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1399G>T | E467* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-014A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1437C>A | Y479* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-006A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1555G>T | E519* | Nonsense |

| XCGD-028A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.77_78del | F26Cfs*8 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-083A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.126_130delinsTTTC | R43Ffs*18 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-009A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.713del | V238Gfs*4 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-118A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.714_715insTA | H239Yfs*4 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-139A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.722_726delTAACA | I241fs*243 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-115A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.725_726del | T242Sfs*3 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-037A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.742del | I248Sfs*7 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-003A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.742dup | I248Nfs*36 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-102A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.742dup | I248Nfs*36 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-113A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.742dup | I248Nfs*36 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-030A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.857_867del | V286Afs*58 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-092A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1038del | E347Rfs*39 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-079A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1313del | K438Rfs*64 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-010A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1327del | W443Gfs*59 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-073A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1332del | C445Afs*57 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-126A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1565del | T522Kfs*11 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-134A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1599_1602del | V534Sfs*12 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-090A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1619_1626dup | A543Kfs*7 | Frameshift |

| XCGD-075A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.70_72del | F24del | In-frame Deletion/Insertion |

| XCGD-007A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.646_648del | F216del | In-frame Deletion/Insertion |

| XCGD-048A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1164_1166delinsATC | 388_389delinsES | In-frame Deletion/Insertion |

| XCGD-129A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1322_1324del | F441del | In-frame Deletion/Insertion |

| XCGD-045A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.45+1G>A | Splicing | |

| XCGD-100A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.45+1G>A | Splicing | |

| XCGD-119A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.45+1G>C | Splicing | |

| XCGD-143A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.45+2delT | Splicing | |

| XCGD-017A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.46-1G>C | Splicing | |

| XCGD-132A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.141+1_141+2del | Splicing | |

| XCGD-093A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.141+3A>T | Splicing | |

| XCGD-001A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.252G>A | A84= | Splicing |

| XCGD-002A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.252G>A | A84= | Splicing |

| XCGD-104A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.252G>A | A84= | Splicing |

| XCGD-114A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.252G>A | A84= | Splicing |

| XCGD-015A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.253-1G>A | Splicing | |

| XCGD-089A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.674+6T>C | Splicing | |

| XCGD-109A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.675-1G>T | Splicing | |

| XCGD-042A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.804+2T>C | Splicing | |

| XCGD-071A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1150_1151+2delAAGT | Splicing | |

| XCGD-098A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1151+1G>A | Splicing | |

| XCGD-099A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1314+2T>G | Splicing | |

| XCGD-023A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1315-2A>C | Splicing | |

| XCGD-061A | CYBB | X-linked | EX1-EX13del | Gross Deletion | |

| XCGD-041A | CYBB | X-linked | EX7-EX11del | Gross Deletion | |

| XCGD-116A | CYBB | X-linked | EX8-EX13del | Gross Deletion | |

| XCGD-026A | CYBB | X-linked | LRG_53t1:c.1713A>T | *571Yext*8 | Extension |

Repeated mutations are in bold. CYBB, cytochrome b-245 beta chain; XCGD, X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. *translation termination (stop) codon.

Table 3.

Causal mutations identified in IL2RG gene (Reference Sequence LRG_150) of the XSCID patients.

| Patient ID | Gene | Mutant allele | cDNA/nucleotide change | Protein change | Mutant type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL2RG-062A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.3G>T | M1I | Start Lost |

| IL2RG-043A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.202G>A | E68K | Missense |

| IL2RG-089A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.202G>A | E68K | Missense |

| IL2RG-080A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.252C>A | N84K | Missense |

| IL2RG-142A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.272A>G | Y91C | Missense |

| IL2RG-063A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.304T>C | C102R | Missense |

| IL2RG-048A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.340G>T | G114C | Missense |

| IL2RG-027A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.365T>C | I122T | Missense |

| IL2RG-005A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.371T>C | L124P | Missense |

| IL2RG-064A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.383T>C | F128S | Missense |

| IL2RG-111A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.386T>A | V129D | Missense |

| IL2RG-049A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.618T>A | H206Q | Missense |

| IL2RG-008A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.670C>T | R224W | Missense |

| IL2RG-047A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.670C>T | R224W | Missense |

| IL2RG-112A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.675C>A | S225R | Missense |

| IL2RG-041A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.676C>T | R226C | Missense |

| IL2RG-123A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.676C>T | R226C | Missense |

| IL2RG-004A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.677G>A | R226H | Missense |

| IL2RG-115A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.694G>C | G232R | Missense |

| IL2RG-079A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.709T>C | W237R | Missense |

| IL2RG-015A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.722G>T | S241I | Missense |

| IL2RG-009A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.854G>A | R285Q | Missense |

| IL2RG-014A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.854G>A | R285Q | Missense |

| IL2RG-020A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.854G>A | R285Q | Missense |

| IL2RG-022A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.854G>A | R285Q | Missense |

| IL2RG-025A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.854G>A | R285Q | Missense |

| IL2RG-061A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.854G>A | R285Q | Missense |

| IL2RG-083A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.854G>T | R285L | Missense |

| IL2RG-076A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.979_980delinsTT | E327L | Missense |

| IL2RG-122A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.979G>A | E327K | Missense |

| IL2RG-132A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.184T>A LRG_150t1:c.204G>C |

C62S E68D |

Missense Missense |

| IL2RG-147A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.181C>T | Q61* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-067A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.202G>T | E68* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-075A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.306C>A | C102* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-012A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.376C>T | Q126* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-103A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.376C>T | Q126* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-007A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.562C>T | Q188* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-033A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.562C>T | Q188* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-023A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.711G>A | W237* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-096A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.811G>T | G271* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-098A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.865C>T | R289* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-141A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.865C>T | R289* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-146A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.865C>T | R289* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-104A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.929G>A | W310* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-032A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.982C>T | R328* | Nonsense |

| IL2RG-028A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.127del | T43Pfs*28 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-003A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.310_311delinsG | H104Afs*43 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-016A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.359dup | E121Gfs*47 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-055A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.362del | E121Gfs*26 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-088A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.362del | E121Gfs*26 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-074A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.406_415del | R136Gfs*8 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-018A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.421del | Q141Rfs*6 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-017A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.507del | Q169Hfs*2 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-058A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.507del | Q169Hfs*2 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-120A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.658_659del | T220Vfs*8 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-040A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.741dup | S248Efs*55 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-097A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.741del | S248Afs*25 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-001A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.835del | V279Cfs*15 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-002A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.855-72_925-11del | T286Pfs*57 | Frameshift |

| IL2RG-145A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.115+1G>A | Splicing | |

| IL2RG-118A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.115+2T>C | Splicing | |

| IL2RG-143A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.270-2A>G | Splicing | |

| IL2RG-035A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.270-15A>G | Splicing | |

| IL2RG-059A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.270-15A>G | Splicing | |

| IL2RG-129A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.455-2A>T | Splicing | |

| IL2RG-144A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.757_757+1delinsTC | Splicing | |

| IL2RG-113A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.854+3G>T | Splicing | |

| IL2RG-006A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.854+5G>A | Splicing | |

| IL2RG-011A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.854+5G>A | Splicing | |

| IL2RG-042A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.855-2A>C | Splicing | |

| IL2RG-121A | IL2RG | X-linked | LRG_150t1:c.855-2A>T | Splicing |

Repeated mutations are in bold. IL2RG, interleukin 2 receptor subunit gamma; XSCID, X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. *translation termination (stop) codon.

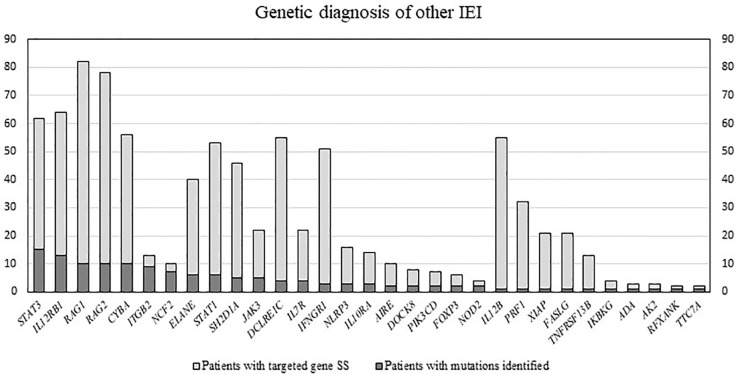

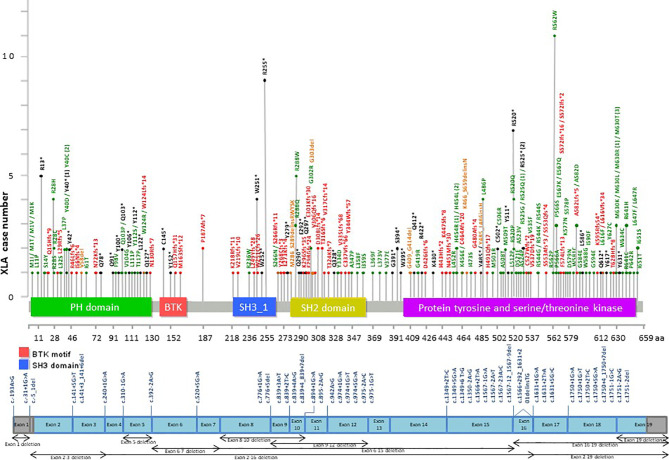

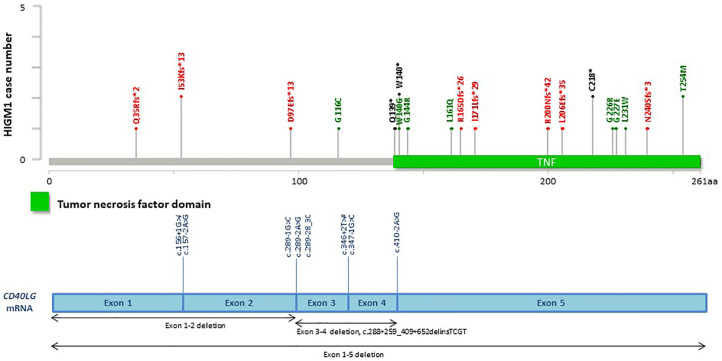

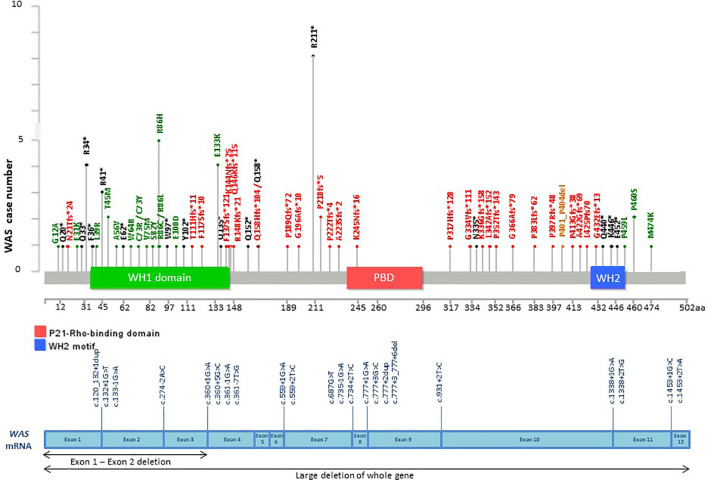

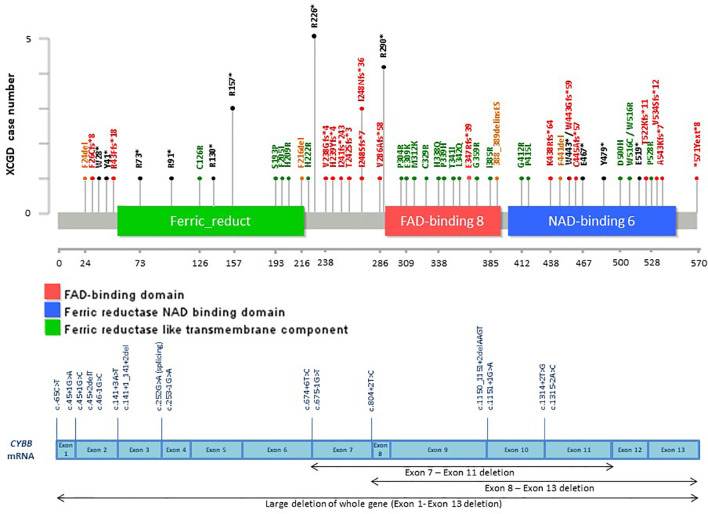

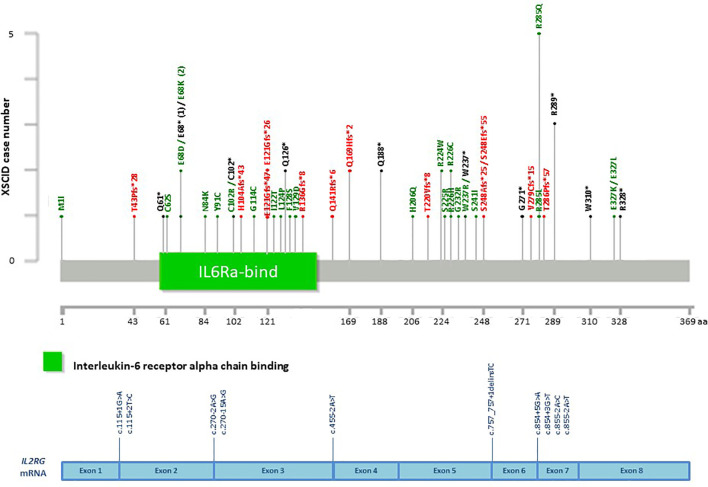

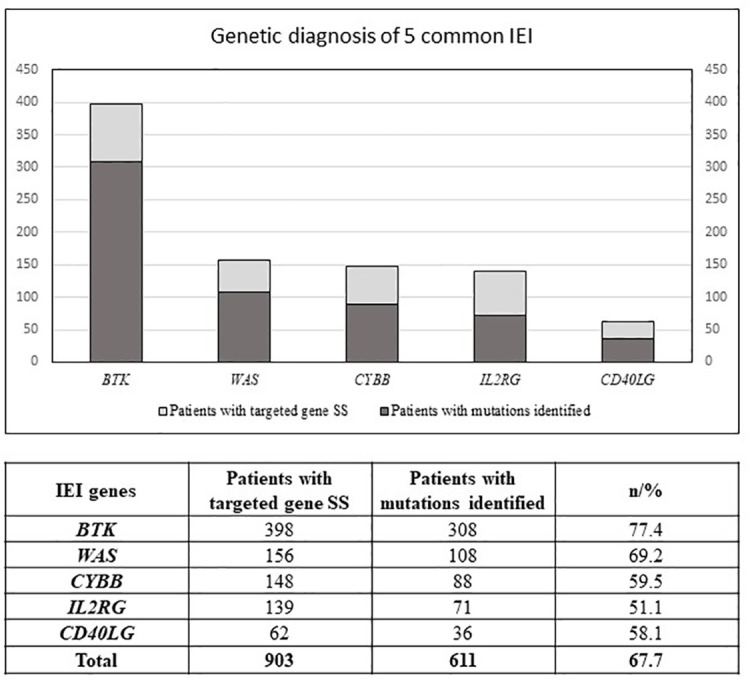

Among the patients with the 5 common IEI referred, 903 single targeted gene SS were performed in the first round of screening with 611 causal mutations identified (67.7%), with the positive diagnostic rate ranging from 51.1% (IL2RG gene mutations for XSCID) to 77.4% (BTK gene mutations for XLA) ( Figure 2 ). XLA is the most common referred IEI with the highest positive diagnostic rate. For the other typical and atypical IEI patients (including those with negative finding after screening for the 5 common IEI), a total of 1,121 targeted gene SS (single or multiple rounds of SS may have been done for each patient) were performed with causal mutations identified in 133 (11.9%; Table 5 and Figure 3 ). Among the 5 common IEI, the locations of causal mutations were shown in Figures 4 – 8 . The mutations identified include missense, nonsense, frameshift, and splicing variants. In addition, uncommon mutations such as gross deletion, in-frame deletion/insertion, start loss, stop loss and regulatory variants were identified.

Figure 2.

Number of patients with first round of targeted gene SS (Sanger Sequencing) performed, and number of patients with mutations identified. IEI, inborn errors of immunity; SS, Sanger sequencing; BTK, Bruton tyrosine kinase; WAS, WASP actin nucleation promoting factor; CYBB, cytochrome b-245 beta chain; IL2RG, interleukin 2 receptor subunit gamma; CD40LG; CD40 ligand.

Table 5.

Number of patients with targeted gene SS performed, and number of patients with mutations identified.

| IEI genes | Patients with targeted gene SS | Patients with mutations identified | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCF2 | 10 | 7 | 70.0 |

| ITGB2 | 13 | 9 | 69.2 |

| NOD2 | 4 | 2 | 50.0 |

| RFXANK | 2 | 1 | 50.0 |

| TTC7A | 2 | 1 | 50.0 |

| FOXP3 | 6 | 2 | 33.3 |

| ADA | 3 | 1 | 33.3 |

| AK2 | 3 | 1 | 33.3 |

| PIK3CD | 7 | 2 | 28.6 |

| DOCK8 | 8 | 2 | 25.0 |

| IKBKG | 4 | 1 | 25.0 |

| STAT3 | 62 | 15 | 24.2 |

| JAK3 | 22 | 5 | 22.7 |

| IL10RA | 14 | 3 | 21.4 |

| IL12RB1 | 64 | 13 | 20.3 |

| AIRE | 10 | 2 | 20.0 |

| NLRP3 | 16 | 3 | 18.8 |

| IL7R | 22 | 4 | 18.2 |

| CYBA | 56 | 10 | 17.9 |

| ELANE | 40 | 6 | 15.0 |

| RAG2 | 78 | 10 | 12.8 |

| RAG1 | 82 | 10 | 12.2 |

| STAT1 | 53 | 6 | 11.3 |

| SH2D1A | 46 | 5 | 10.9 |

| TNFRSF13B | 13 | 1 | 7.7 |

| DCLRE1C | 55 | 4 | 7.3 |

| IFNGR1 | 51 | 3 | 5.9 |

| XIAP | 21 | 1 | 4.8 |

| FASLG | 21 | 1 | 4.8 |

| PRF1 | 32 | 1 | 3.1 |

| IL12B | 55 | 1 | 1.8 |

| FAS | 20 | 0 | 0.0 |

| UNC13D | 16 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ICOS | 16 | 0 | 0.0 |

| AICDA | 13 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CASP10 | 12 | 0 | 0.0 |

| MVK | 10 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CD40 | 10 | 0 | 0.0 |

| UNG | 10 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IL10RB | 9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| RAB27A | 9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| NLRP12 | 7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CD79A | 7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| HAX1 | 7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| TNFRSF1A | 7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| TYK2 | 7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| LIG4 | 6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CARD9 | 6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| RASGRP1 | 6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ZAP70 | 6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IL10 | 5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IL24 | 5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IRAK4 | 5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CD19 | 4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| NCF4 | 4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| PNP | 3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IFNGR2 | 3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CLEC7A | 3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| MYD88 | 3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| PRKCD | 3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| MAGT1 | 2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IL12A | 2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ITK | 2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| STAT5B | 2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| STK4 | 2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| TCF3 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IL2RA | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CXCR4 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| LRBA | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| TCIRG1 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CLCN7 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| FERMT3 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| GATA2 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IL1RN | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IL36RN | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| IRF8 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| LAT | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| PGM3 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| PSMB8 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 1121 | 133 | 11.9 |

Official gene symbols approved by HGNC were used. Approved full gene names are available in HGNC. IEI, inborn errors of immunity; SS, Sanger sequencing; HGNC, HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee. Sum of patients are in bold.

Figure 3.

Number of patients with targeted gene SS performed, and number of patients with mutations identified. Official gene symbols approved by HGNC were used. Approved full gene names are available in HGNC. IEI, inborn errors of immunity; SS, Sanger sequencing; HGNC; HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee.

Figure 4.

Distribution of casual mutations in various exons, exon-intron junctions and corresponding domains of BTK gene. The upper diagram shows the distribution and frequency of amino acid mutations in various protein domains; while the lower diagram shows the locations of splice site mutations and large deletions of the gene. BTK, Bruton tyrosine kinase; XLA, X-linked agammaglobulinemia; PH, Pleckstrin homology; SH2, Src homology 2; SH3. Src homology 3.

Figure 8.

Distribution of casual mutations in various exons, exon-intron junctions and corresponding domains of IL2RG gene. The upper diagram shows the distribution and frequency of amino acid mutations in various protein domains; while the lower diagram shows the locations of splice site mutations and large deletions of the gene. CD40LG; CD40 ligand; HIGM1, X-linked immunodeficiency with hyper-IgM type 1.

Figure 5.

Distribution of casual mutations in various exons, exon-intron junctions and corresponding domains of WAS gene. The upper diagram shows the distribution and frequency of amino acid mutations in various protein domains; while the lower diagram shows the locations of splice site mutations and large deletions of the gene. WAS, WASP actin nucleation promoting factor; WAS, Wiskott Aldrich Syndrome; PBD, P21-Rho-binding domain; WH1, WASP homology 1 domain; WH2, WASP homology 2 domain.

Figure 6.

Distribution of casual mutations in various exons, exon-intron junctions and corresponding domains of CYBB gene. The upper diagram shows the distribution and frequency of amino acid mutations in various protein domains; while the lower diagram shows the locations of splice site mutations and large deletions of the gene. CYBB, cytochrome b-245 beta chain; XCGD, X-linked chronic granulomatous disease.

Figure 7.

Distribution of casual mutations in various exons, exon-intron junctions and corresponding domains of IL2RG gene. The upper diagram shows the distribution and frequency of amino acid mutations in various protein domains; while the lower diagram shows the locations of splice site mutations and large deletions of the gene. IL2RG, interleukin 2 receptor subunit gamma; XSCID, X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency.

Discussions

Using one single round of targeted gene SS in our study was successful in diagnosing 611 of the 903 patients (67.7%) suspected to have one of the 5 common IEI, i.e., XLA (77.4%), WAS (69.2%), XCGD (59.5%), XHIM (58.1%), and XSCID (51.1%), definitively. These 5 IEI are X-linked which renders the genetic diagnosis more readily and accurately achieved. At the clinical level, a positive family history of maternal uncles or male cousins affected with similar clinical and immunological phenotypes, suggestive of X-linked pattern of inheritance, will be the first clue. Moreover, the clinical and immunological phenotypes of these 5 IEI are relatively uniform, except for XSCID, which could have multiple phenotypes due to hypomorphic mutations of IL2RG gene as well as presence of multiple genes giving rise to similar immunological phenotypes. The immunophenotype of these 5 IEI is more easily defined by laboratory tests which are less technically demanding and more available, such as complete blood count, lymphocyte subsets, immunoglobulin profile, and the nitroblue tetrazolium test (6). Though the diagnostic resources and experience of referring clinicians could differ among different centres, affecting the accuracy of the diagnosis for these 5 IEI, our findings demonstrated that the individual positive diagnostic rate is much higher than that for the other IEI (11.9%), see Supplementary Figure 1 . In addition, referring clinicians can learn from our e-consultation and diagnostic algorithm to further improve the diagnostic rate. More importantly, these 5 IEI occur at much higher rates than the rest of the 400 IEI, resulting in a higher level of awareness among paediatricians, hence earlier recognition, and referral for definitive genetic diagnosis than the less common IEI.

At the genetic diagnostic level, X-linked IEI is easier to diagnose than autosomal recessive IEI in non-consanguineous population, because identification of causal mutation in a single allele is sufficient. Moreover, there is no pitfall of missing the identification of heterozygous gross deletion by Sanger sequencing as in autosomal IEI with PCR still positive in such cases. For the X-linked genes, gross deletion will be picked up by negative PCR, and then one can confirm the deletion in each exon by multiplex PCR, co-amplification of both target and reference gene, with normal control. Due to limitation of our primers design, causal mutations within those intronic and regulatory regions may not be included in the PCR regions, and hence cannot be identified. Nevertheless, the strengths of targeted gene SS include >99% high accuracy, fast turnaround time, low cost, with fewer variants of uncertain significance and no secondary findings (3, 4). Therefore, doing one round of single specific targeted gene SS remains the first-tier genetic test for patients suspected to have one of these 5 common IEI in our laboratory.

Apart from these 5 common IEI, there were 2 more IEI with over 50% genetic diagnostic success rates in our study using targeted gene SS, i.e., leucocyte adhesion deficiency type 1 (LAD1) and autosomal recessive chronic granulomatous disease (AR-CGD) due to neutrophil cytosolic factor2 (NCF2) gene mutations. For LAD1, the clinical and immunological phenotype is uniform with little variation, and LAD1 occurs at a much higher frequency than the other two types of LAD. With flow cytometric analysis of CD18, followed by integrin subunit beta 2 (ITGB2) gene SS, LAD1 can be diagnosed easily (46). Our one round of single targeted gene SS was successful in diagnosing 9 of the 13 patients (69.2%) suspected to have LAD1. As for AR-CGD due to NCF2gene mutations, the success rate of targeted gene SS in making the genetic diagnosis was 70% in our study (7 out of 10 patients), but this was achieved by doing multiple AR-CGD genes at the same time, after failing to identify the genetic mutation for CYBB gene in male patients suspected to have CGD. Therefore, the 70% success rate was not after doing just one round of single targeted gene SS, but after multiple rounds of targeted gene SS of genes responsible for AR-CGD.

For the rest of the IEI, the success rates of achieving genetic diagnosis for each of these IEI after targeted gene SS were mostly under one-third, and in most cases, we had to do multiple rounds of targeted gene SS, with an overall success rate of only 10.9%. Therefore, whole exome sequencing (WES) is now our preferred first-tier genomic test for all the IEI except the 5 most common X-linked IEI and LAD1. However, exceptions do occur, such as AR-CGD due to NCF1 gene, which has pseudogenes, rendering both SS and WES not able to identify the causal mutations due to poor and limited coverage of sequences shared with pseudogenes. Fortunately, 97% of affected alleles in patients previously reported with p47-phox deficiency carry a hot spot mutation of “GT”deletion (ΔGT) in exon 2 of neutrophil cytosolic factor 1 (NCF1) gene (47). One can therefore simply identify the hot spot mutation by GeneScan® analysis as shown in Supplementary Figure 2 before proceeding to sequencing of the coding region. This approach was adopted by us to save time and cost

All in all, we were able to diagnose 744 of the 1376 patients (54.1%) referred to us suspected to have IEI, using targeted genes SS, with an average of 1.47 such tests per patient (ranging from 1 to 10). However, 632 of these 1376 patients (45.9%) of the referred patients remained genetically undiagnosed after single or multiple rounds of targeted gene SS.

With the availability of WES in 2009, we deployed this technology for selected undiagnosed IEI patients. Our first WES case for a male infant with early-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in 2009 resulted in the discovery of interleukin 10 receptor subunit alpha (IL10RA) gene mutations as the underlying cause of early-onset IBD (27), at about the same time when aberrant interleukin 10 (IL10) pathway was implicated as the underlying cause for early-onset IBD by another group using linkage analysis (48). Since then, we have incorporated WES more readily into our diagnostic algorithm, because of the cost coming down as well as developing our own in-house bioinformatic tools and analysis, resulting in discovery of novel IEI (49, 50). We shall review in future our experience in using WES for patients with suspected IEI who remain undiagnosed genetically after targeted gene SS. Comparison between targeted gene SS and NGS (whole exome sequencing WES) in our institutional service has been shown in Supplementary Figure 3 . In general, WES will have wider applications, but longer turnover time compared with SS under the service provided by our centre. However, if both the financial and human resource (laboratory staffs and bioinformaticians) is not a limiting factor, rapid WES may be considered to set up for those urgent cases with immediate clinical management decision (51).

In conclusion, single targeted gene SS should remain the first-tier genetic test for patients suspected to have one of the 5 common X-linked IEI before offering genomic tests such as WES or targeted gene panel (52). Flow chart of our current diagnostic algorithm, with the description of progressive changes in our bioinformatic analysis, has been provided as reference ( Supplementary Figure 4 ). We propose IEI centres in less resourced Asian and African countries and regions could consider setting up targeted gene SS for these 6 IEI which would yield a high enough success rate of genetic diagnosis in a significant number of IEI patients to become cost-effective (6, 53).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Clinical Research Ethics Review Board of The University of Hong Kong and Queen Mary Hospital (Ref. no. UW 08-301). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

Y-LL conceptualized the study. YL, XY, WT, PL, WY, and DL designed the study. K-WC, C-YW, SF, and PM performed genetic study. K-WC, and DL curated mutations. PL and DL phenotyped the patients. K-WC, C-YW, XY, and DL analyzed data. K-WC and C-YW drafted the manuscript. Other authors referred patients and provided clinical care and clinical data. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hong Kong Society for Relief of Disabled Children and Jeffrey Modell Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.883446/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Tangye SG, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Chatila T, Cunningham-Rundles C, Etzioni A, et al. Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: 2019 Update on the Classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee. J Clin Immunol (2020) 40(1):24–64. doi: 10.1007/s10875-019-00737-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bousfiha A, Jeddane L, Picard C, Al-Herz W, Ailal F, Chatila T, et al. Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: 2019 Update of the IUIS Phenotypical Classification. J Clin Immunol (2020) 40(1):66–81. doi: 10.1007/s10875-020-00758-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knight V, Heimall JR, Chong H, Nandiwada SL, Chen K, Lawrence MG, et al. A Toolkit and Framework for Optimal Laboratory Evaluation of Individuals with Suspected Primary Immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract (2021) 9(9):3293–3307 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vorsteveld EE, Hoischen A, van der Made CI. Next-Generation Sequencing in the Field of Primary Immunodeficiencies: Current Yield, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol (2021) 61(2):212–25. doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08838-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abraham RS, Butte MJ. The New "Wholly Trinity" in the Diagnosis and Management of Inborn Errors of Immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract (2021) 9(2):613–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leung D, Chua GT, Mondragon AV, Zhong Y, Nguyen-Ngoc-Quynh L, Imai K, et al. Current Perspectives and Unmet Needs of Primary Immunodeficiency Care in Asia Pacific. Front Immunol (2020) 111605:1605. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hui YF, Chan SY, Lau YL. Identification of mutations in seven Chinese patients with X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. Blood (1996) 88(10):4021–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lau YL, Chan GC, Ha SY, Hui YF, Yuen KY. The role of phagocytic respiratory burst in host defense against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis (1998) 26(1):226–7. doi: 10.1086/517036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lau YL, Jones BM, Low LC, Wong SN, Leung NK. Defective B-cell and regulatory T-cell function in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Eur J Pediatr (1992) 151(9):680–3. doi: 10.1007/BF01957573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lau YL, Kwong YL, Lee AC, Chiu EK, Ha SY, Chan CF, et al. Mixed chimerism following bone marrow transplantation for severe combined immunodeficiency: a study by DNA fingerprinting and simultaneous immunophenotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridisation. Bone Marrow Transplant (1995) 15(6):971–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lau YL, Low LC, Jones BM, Lawton JW. Defective neutrophil and lymphocyte function in leucocyte adhesion deficiency. Clin Exp Immunol (1991) 85(2):202–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05705.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lau YL, Wong SN, Lawton JW, Chow CB. Chronic granulomatous disease: a different pattern in Hong Kong? J Paediatr Child Health (1991) 27(4):235–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1991.tb00399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lau YL, Wong SN, Lawton WM. Takayasu's arteritis associated with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. J Paediatr Child Health (1992) 28(5):407–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1992.tb02703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, Chan CF. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis (1995) 20(1):197–8. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.1.197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roos D. X-CGDbase: a database of X-CGD-causing mutations. Immunol Today (1996) 17(11):517–21. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)30060-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Siu-Yuen C, Yuk-Fan H, Yu-Lung L. An 11-bp deletion in exon 10 (c1295del11) of WASP responsible for Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome. Hum Mutat (1999) 13(6):507. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yip KL, Chan SY, Ip WK, Lau YL. Bruton's tyrosine kinase mutations in 8 Chinese families with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Hum Mutat (2000) 15(4):385. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chan KW, Chen T, Jiang L, Fok SF, Lee TL, Lee BW, et al. Identification of Bruton tyrosine kinase mutations in 12 Chinese patients with X-linked agammaglobulinaemia by long PCR-direct sequencing. Int J Immunogenet (2006) 33(3):205–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2006.00598.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chan KW, Lee TL, Chung BH, Yang X, Lau YL. Identification of five novel WASP mutations in Chinese families with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Hum Mutat (2002) 20(2):151–2. doi: 10.1002/humu.9048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chang YH, Yu HH, Lau YL, Chan KW, Chiang BL. A new autosomal recessive, heterozygous pair of mutations of CYBA in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol (2010) 105(2):183–5. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chong JH, Jamuar SS, Ong C, Thoon KC, Tan ES, Lai A, et al. Tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome (THE-S): two cases and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr (2015) 174(10):1405–11. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2563-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee PP, Chan KW, Chen TX, Jiang LP, Wang XC, Zeng HS, et al. Molecular diagnosis of severe combined immunodeficiency–identification of IL2RG, JAK3, IL7R, DCLRE1C, RAG1, and RAG2 mutations in a cohort of Chinese and Southeast Asian children. J Clin Immunol (2011) 31(2):281–96. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9489-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee PP, Chan KW, Jiang L, Chen T, Li C, Lee TL, et al. Susceptibility to mycobacterial infections in children with X-linked chronic granulomatous disease: a review of 17 patients living in a region endemic for tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J (2008) 27(3):224–30. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31815b494c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee PP, Chen TX, Jiang LP, Chan KW, Yang W, Lee BW, et al. Clinical characteristics and genotype-phenotype correlation in 62 patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. J Clin Immunol (2010) 30(1):121–31. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9341-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee PP, Chen TX, Jiang LP, Chen J, Chan KW, Lee TL, et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of 35 Chinese children with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. J Clin Immunol (2009) 29(4):490–500. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9285-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee PP, Mao H, Yang W, Chan KW, Ho MH, Lee TL, et al. Penicillium marneffei infection and impaired IFN-gamma immunity in humans with autosomal-dominant gain-of-phosphorylation STAT1 mutations. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2014) 133(3):894–6 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mao H, Yang W, Lee PP, Ho MH, Yang J, Zeng S, et al. Exome sequencing identifies novel compound heterozygous mutations of IL-10 receptor 1 in neonatal-onset Crohn's disease. Genes Immun (2012) 13(5):437–42. doi: 10.1038/gene.2012.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Naidoo R, Jordaan N, Chan KW, Le Roux DM, Pienaar S, Nuttall J, et al. A novel CYBB mutation with the first genetically confirmed case of chronic granulomatous disease in South Africa. S Afr Med J (2011) 101(10):768–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rawat A, Singh S, Suri D, Gupta A, Saikia B, Minz RW, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease: two decades of experience from a tertiary care centre in North West India. J Clin Immunol (2014) 34(1):58–67. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9963-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsai HY, Yu HH, Chien YH, Chu KH, Lau YL, Lee JH, et al. X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome with CD40LG mutation: two case reports and literature review in Taiwanese patients. J Microbiol Immunol Infect (2015) 48(1):113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang W, Lee PP, Thong MK, Ramanujam TM, Shanmugam A, Koh MT, et al. Compound heterozygous mutations in TTC7A cause familial multiple intestinal atresias and severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Genet (2015) 88(6):542–9. doi: 10.1111/cge.12553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ben-Ali M, Kechout N, Mekki N, Yang J, Chan KW, Barakat A, et al. Genetic Approaches for Definitive Diagnosis of Agammaglobulinemia in Consanguineous Families. J Clin Immunol (2020) 40(1):96–104. doi: 10.1007/s10875-019-00706-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boushaki S, Tahiat A, Meddour Y, Chan KW, Chaib S, Benhalla N, et al. Prevalence of BTK mutations in male Algerian patterns with agammaglobulinemia and severe B cell lymphopenia. Clin Immunol (2015) 161(2):286–90. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rawat A, Jindal AK, Suri D, Vignesh P, Gupta A, Saikia B, et al. Clinical and Genetic Profile of X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia: A Multicenter Experience From India. Front Immunol (2020) 11612323:612323. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.612323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rawat A, Vignesh P, Sharma A, Shandilya JK, Sharma M, Suri D, et al. Infection Profile in Chronic Granulomatous Disease: a 23-Year Experience from a Tertiary Care Center in North India. J Clin Immunol (2017) 37(3):319–28. doi: 10.1007/s10875-017-0382-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rawat A, Vignesh P, Sudhakar M, Sharma M, Suri D, Jindal A, et al. Clinical, Immunological, and Molecular Profile of Chronic Granulomatous Disease: A Multi-Centric Study of 236 Patients From India. Front Immunol (2021) 12625320:625320. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.625320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Singh S, Rawat A, Suri D, Gupta A, Garg R, Saikia B, et al. X-linked agammaglobulinemia: Twenty years of single-center experience from North West India. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol (2016) 117(4):405–11. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.07.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Suri D, Rikhi R, Jindal AK, Rawat A, Sudhakar M, Vignesh P, et al. Wiskott Aldrich Syndrome: A Multi-Institutional Experience From India. Front Immunol (2021) 12627651:627651. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.627651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vignesh P, Loganathan SK, Sudhakar M, Chaudhary H, Rawat A, Sharma M, et al. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Children with Chronic Granulomatous Disease-Single-Center Experience from North India. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract (2021) 9(2):771–782 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vignesh P, Rawat A, Kumar A, Suri D, Gupta A, Lau YL, et al. Chronic Granulomatous Disease Due to Neutrophil Cytosolic Factor (NCF2) Gene Mutations in Three Unrelated Families. J Clin Immunol (2017) 37(2):109–12. doi: 10.1007/s10875-016-0366-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vignesh P, Rawat A, Kumrah R, Singh A, Gummadi A, Sharma M, et al. Clinical, Immunological, and Molecular Features of Severe Combined Immune Deficiency: A Multi-Institutional Experience From India. Front Immunol (2020) 11619146:619146. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.619146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vignesh P, Suri D, Rawat A, Lau YL, Bhatia A, Das A, et al. Sclerosing cholangitis and intracranial lymphoma in a child with classical Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer (2017) 64(1):106–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee PP, Lau YL. Primary immunodeficiencies: "new" disease in an old country. Cell Mol Immunol (2009) 6(6):397–406. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee PP, Lau YL. Improving care, education, and research: the Asian primary immunodeficiency network. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2011), 123833–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR, Hart RK, Greenblatt MS, Mcgowan-Jordan J, et al. HGVS Recommendations for the Description of Sequence Variants: 2016 Update. Hum Mutat (2016) 37(6):564–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.22981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kambli PM, Bargir UA, Yadav RM, Gupta MR, Dalvi AD, Hule G, et al. Clinical and Genetic Spectrum of a Large Cohort of Patients With Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency Type 1 and 3: A Multicentric Study From India. Front Immunol (2020) 11612703:612703. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.612703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Roos D, De Boer M, Koker MY, Dekker J, Singh-Gupta V, Ahlin A, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease caused by mutations other than the common GT deletion in NCF1, the gene encoding the p47phox component of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Hum Mutat (2006) 27(12):1218–29. doi: 10.1002/humu.20413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Glocker EO, Kotlarz D, Boztug K, Gertz EM, Schaffer AA, Noyan F, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptor. N Engl J Med (2009) 361(21):2033–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ben-Ali M, Yang J, Chan KW, Ben-Mustapha I, Mekki N, Benabdesselem C, et al. Homozygous transcription factor 3 gene (TCF3) mutation is associated with severe hypogammaglobulinemia and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2017) 140(4):1191–4.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mao H, Yang W, Latour S, Yang J, Winter S, Zheng J, et al. RASGRP1 mutation in autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome-like disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2018) 142(2):595–604.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chung CCY, Leung GKC, Mak CCY, Fung JLF, Lee M, Pei SLC, et al. Rapid whole-exome sequencing facilitates precision medicine in paediatric rare disease patients and reduces healthcare costs. Lancet Reg Health West Pac (2020) 1100001. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chinn IK, Chan AY, Chen K, Chou J, Dorsey MJ, Hajjar J, et al. Diagnostic interpretation of genetic studies in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases: A working group report of the Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Committee of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2020) 145(1):46–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Luk ADW, Lee PP, Mao H, Chan KW, Chen XY, Chen TX, et al. Family History of Early Infant Death Correlates with Earlier Age at Diagnosis But Not Shorter Time to Diagnosis for Severe Combined Immunodeficiency. Front Immunol (2017) 8808:808. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.