Abstract

This paper proposes a new methodology based on textual analysis to forecast US recessions. Specifically, it presents an index in the spirit of Baker et al. (JAMA 131:1593–1636, 2016) and Caldara and Iacoviello (JAMA 1222, 2018) that tracks developments in US real activity. When used in a standard recession probability model, this index outperforms the yield curve-based forecast, a standard method to forecast recessions, at medium horizons, up to 8 months. Moreover, the index contains information not included in yield data, that are useful to understand recession episodes; when included as an additional control along with the slope of the yield curve, it improves forecasting accuracy by between 5% and 40%, depending on the horizon considered. These results are stable to a number of different robustness checks, including different estimation methods, different definitions of recession and controlling for asset purchases by major central banks. Our textual analysis data also improve the forecasting accuracy of several other popular leading indicators for the US business cycle.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1057/s41308-022-00177-5.

JEL Classification: E17, E47, E37, C25, C53

Introduction

There are several empirical regularities in the US business cycle that can be exploited to forecast US recessions. One of them is the widely used yield curve indicator. Yield curve recession probability models exploit the slope of the yield curve, the difference between short- and long-term interest rates on Federal securities, to forecast US recessions, employing standard binary regression methods. Estrella and Hardouvelis (1991), de Lindt and Stolin (2003) and, more recently, Benzoni et al. (2018), have shown that there are strong empirical regularities that make the slope of the yield curve a good recession indicator, particularly at medium term horizons. This approach has been revised in the context of the Asset Purchase Programs (APPs), adopted by major central banks. APP purchases tend to target long-term securities, resulting in a compression of the long-end of the yield curve, which does not translate proportionally into a reduction in short-term yields. As a consequence, the yield curve flattens not because investors change their beliefs about the future of the economy and adjust their portfolios, but rather as the result of policy actions. This can lead to false recession signals which can be potentially more misleading for the US economy because of its role of global safe assets issuer.1 Alternative popular modelling choices exploit commodity prices (in particular, the price of copper), stock market returns or even soft data such as consumer purchases of household services, to predict future economic slowdown.2

In this paper, we explore a different approach that uses information obtained from newspaper articles. Use of such data is not new and has been applied, between others, to the measurement of geopolitical risk, Caldara and Iacoviello (2018) and uncertainty, Baker et al. (2016). The advantage of text data is that they capture a combination of hard and soft information on the state of the economy, at high frequency, and can serve to complement data provided by more traditional indicators such as surveys, financial market and production inventories. In addition, newspaper-based data are available at daily frequency and are relatively easy to update for a large set of economies.

Compared to other applications, our paper provides innovations in four dimensions. First, we apply the approach by Baker et al. (2016) to the study of recession probabilities, building an index that traces developments in US real activity. Specifically, we construct an index that measures the proportion of newspaper articles discussing a recession over the total number of articles published in each period. We find that the constructed index correlates well with several US business cycle indicators, such as National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) recession dummies or industrial production (IP) growth. Second, we show, in a formal regression framework, that the proposed index outperforms the standard yield-curve model at medium horizons (from 1 to 8 months) implying that text-based data have strong now-casting properties. Third, our results suggest that the text-based index provides complementary information to the yield curve. Adding the index to a standard yield curve model specification improves the forecasting accuracy by between 5% and 40%, depending on the forecast horizon considered. Fourth, we compare the forecasting performance of our text-based index with other popular US leading indicators, such as surveys and financial market data, the Gilchrist and Zakrajšek (2012) “excessive bond premium”, and the text-based indices by Shapiro et al. (2020) and Ardia et al. (2019). Our index outperforms several of them at short to medium horizons, confirming its good now-casting properties. Moreover, a model that includes both our index and each of these indicators generally improves the share of correct predictions by a significant amount, implying that our text-based index provides complementary information on the state of the US economy. Our results are robust to several robustness exercises, such as changing the definition of recessions or the estimation framework.

Related Literature

This paper is related to two major strands of the literature: recession probability modelling, and application of computational linguistic and textual analysis tools to economics.

Recession probability modelling. Using interest rates and their term structure as a predictor of recessions has received much attention in the literature. Previous works, such as Kessel (1965), Fama (1986), Mody and Taylor (2003) and Benzoni et al. (2018), find a strong link between the flattening of the yield curve (i.e., the reduction of the differential between short-term and long-term rates) and periods of recession or economic slowdown. In times of economic slowdown, market participants anticipate that interest rates in the future will be lower, either because the economy will enter a contraction or policy rates will be cut in the future to provide stimulus. The expectation of lower future rates leads to portfolio adjustments and reduces longer-term yields, which can result in an inverted yield curve.3 To the extent that markets forecast economic downturns correctly, the flattening of the yield curve in the present can be taken as signalling a higher probability of a future recession. Several empirical evidences have shown that the term structure of interest rates used to have greater predictive power than other leading economic and financial indices. In particular, Estrella and Mishkin (1996) compare the treasury yield curve with other widely used indicators of future economic activity and find that the differential between long- and short-term interest rates outperforms many traditional forecasting measures for the USA, including the US Commerce Department index.

Technically, yield curve information have been included in different forecasting frameworks for GDP, consumption and employment, see for example Stock and Watson (2003). More recently, probit models have been used to forecast the probability of a future recession, captured by NBER recession dates.4 Estrella and Hardouvelis (1991), Chauvet and Potter (2002) and Wright (2006) show that this approach, compared to continuous variable specifications, delivers more accurate recession forecasts. Another advantage of using a binary recession indicator variable is that it identifies the start and duration of the recession, while models forecasting continuous economic variables could be more affected by endogeneity. Specifically, Estrella and Hardouvelis (1991) and Wright (2006) show that simple probit regressions give more accurate recession forecasts than more sophisticated models for horizons of 1 to 12 months. However, these models have recently been the subject of criticism following the implementation of APPs by major central banks. Asset purchases compress the long end of the yield curve, possibly even more in the case of US treasuries, which distorts the historical relation between the yield curve and real activity, Engstrom and Sharpe (2018). The relevance of such distortion is still being debated, for example, Debortoli et al. (2019) suggest that the impact should be modest.5 The present paper conducts several robustness checks to account for potential distortions induced by the APP period. Finally, potentially because of the aforementioned reasons, the forecasting power of the yield curve has weakened in more recent samples; therefore, other forward-looking indicators have been developed to complement information extracted from yields. One example is the “excess bond premium” proposed by Gilchrist and Zakrajšek (2012) as a leading indicator for the US business cycle.6 In this paper, we show that our index complements these more recent forward-looking indicators and improves their forecast performances.

Textual analysis in economics. There is a growing stream of work exploring textual analysis methods to construct economic indicators. For example, Hansen et al. (2018) study monetary policy decision-making, based on an analysis of Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) minutes via computation linguistic algorithms; Ke et al. (2019) construct an index of investor sentiment, applying textual analysis methods to the Dow Jones Newswires; Gholampour and van Wincoop (2019) use information extracted from professional traders’ tweets to explain exchange rate movements; and finally, Minesso Ferrari et al. (2020) analyze trade-related announcements on social media to construct an indicator of the trade tensions between the USA and China. In this context, press articles are another important source of information since they reflect how economic commentators perceive the state and the outlook of the economy; in other term, they are an aggregate measure of economic sentiment that, if properly measured, can become a powerful prediction tool. For example, Matsusaka and Sbordone (1995) and Batchelor and Dua (1998) show that consumer sentiment helps to predict GDP, and even after controlling for other relevant variables.7 More recently, Bybee et al. (2021) estimate a topic model based on Wall Street Journal articles. The resulting indices explain about 25% of stock price volatility and improve the predicting power of VAR models of the US business cycle. One of the topics identified in their exercises is indeed related to “recessions” covering words such as “week economy”, “economic downturns”, “hit bottom”, “hardest hit”; when included in a VAR framework, this time series is used to generate a impulse responses to “extreme shocks” of media attention. Our approach is similar in spirit but simpler; we do not require text data on large cross-section of articles and we do not need to estimate a topic model to construct our recession indicator. On top of practical advantages, because our method does not require the estimation of a first-stage model, our text-based index is not subject to estimation uncertainty related, for example, to the number of topics estimated, the sample considered or uncertainty over the “parameters” of the topic model itself.8

Text analysis is also used in forecasting. Ardia et al. (2019) use machine learning techniques to build a weighted index based on topical analysis-based sentiment sub-indices, that is used to forecast US industrial production. Kalamara et al. (2020) also apply machine learning tools, combined with data extracted from major UK newspapers, to improve the prediction of an empirical business cycle model. Shapiro et al. (2020) and Burri and Kaufmann (2020) have also recently proposed sentiment-scoring model based on lexicons, for the USA and the Swiss economies, that improve the accuracy of real activity forecast models. Differently from these contributions, our proposed index is focused on forecasting recessions. Also, while the previous indices require heavy computational power, our index, which is based on measuring the proportion of articles discussing recessions, is parsimonious and easy to compute while still improving forecast results. Finally, if our index is used together with those by Ardia et al. (2019) and Shapiro et al. (2020), the combined model outperforms the predictions of the individual indices, implying that our indicator contains information that are not already included in those by Ardia et al. (2019) and Shapiro et al. (2020).

Textual analysis methods are also used widely to measure uncertainty and estimate its implications for business cycle fluctuations. Baker et al. (2016) and Caldara and Iacoviello (2018) create measures of uncertainty based on the share of articles discussing USA or global geopolitical tensions. They show that, in a VAR setting, these indices can be used to disentangle the role of “geopolitical tension” shocks. Caldara et al. (2020) use a similar approach to analyze the role of trade tensions. In this paper, we use similar text data methods to create a high-frequency measure of the state of the US business cycle. The use of sentiment series derived from newspapers articles provides several benefits. First, they incorporate news and events that might take time to be reflected in more traditional, but low-frequency, macroeconomic variables. Moreover, this type of data provides useful signals about the present and future state of the economy and summarizes several “hard” and “soft” information discussed by economic commentators. Finally, the correlation between this indicator and the state of the economy is more likely to remain stable over time, and not to be distorted by APP.

Data

Our main source of data is Factiva Analytics, which gathers articles from major newspapers around the world, since the early 1980s.9 In particular, the platform enables the sorting of articles by topic, geographical location and language. In the present study, we consider only articles written in English, published by US-based newspapers and covering domestic news. This avoids contamination from news about foreign recessions or global shocks that affect differently the US and enables a focus only on factors relevant to the domestic economy.

Similar to Caldara et al. (2020) and Baker et al. (2016), we compute our US business cycle indicator as the share of newspaper articles on the USA, falling in the economic topic, published daily, that contain the words ”recession” or ”slowdown.” In other words, the index is defined as the ratio between articles discussing a recession relative to the total number of articles published about the economy.10 Intuitively, if a crisis is about to erupt, newspapers should devote more space to discussion of economic slowdown compared to periods of expansion. It is important, also, to construct the index based on the share of economic articles. The total number of articles published has grown over time and is reflected by the increased number of pages in published newspapers. This would increase the number of articles discussing economic contraction in the most recent part of the sample which prevents comparison across time. However, relative numbers should be more stable to the rise in the media coverage and, thus, be a more consistent indicator. Baker et al. (2016) and Caldara et al. (2020) use the same approach to construct their political and trade uncertainty indices.

Figure 1 reports our index. For each calendar day from 1 January 1985 to 30 September 2020, we compute the share of articles discussing a recession in the US economy relative to all the articles published that day. Our approach benefits from its simplicity and easy scalability to other countries. The resulting index can be computed, potentially, for each calendar date, which allows assessment of the relatively high-frequency changes in newspaper sentiment and, hence, provides a good now-casting tool. To conduct a formal comparison between the information extracted from newspapers and that provided by financial data, we aggregate the index at monthly frequency, which is the frequency most commonly used to analyze US recessions, see Wright (2006).

Fig. 1.

Newspaper-based index of US recessions. Notes: the text-based index (left scale) is reported against NBER recession dummies (shaded areas) and US industrial production (right scale). The index is computed as the share of articles discussing a slowdown of the US economy relative to all other articles published in the USA

In Fig. 1, the index is plotted against NBER recession dummies and US industrial production. It identifies the 2001 and 2008 recessions and, more generally, correlates with contractions in US output. Note that the NBER defines a month to be in a recession with a lag of about two quarters.11 This means that if a particular month is identified by the indicator as a recession month, there will be a lag before the NBER dummies signal it as in a recession period; hence, when newspapers are published, that period is not formally defined as a month of recession. Figure 1 suggests, also, that our newspaper-based index could be a good coincident indicator of US real activity. In the succeeding sections, we formally test the now-casting and forecasting properties of our index in a standard recession probability model (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variables | Mean | Standard deviation | Time periods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index | 0.22 | 0.47 | Jan 1985-Dec 2020 |

| Spread | 1.75 | 1.12 | Jan 1985-Dec 2020 |

The Information Content of Newspaper Data

Forecasting US Contractions

To formally test the predictive power of the index, we include it in a recession probability model in the spirit of Ang et al. (2006) and Wright (2006).12 Their frameworks are based on probit regressions where the probability of being in a recession at a future horizon is explained by the slope of the yield curve at t (the difference between the short- and long-term rate).13 In our specification, rather than exploiting the yield differential, we use our newspaper-based index. The model is specified formally as follows:

| 4.1 |

where is the standard normal cumulative distribution function. Recession periods are defined using NBER recession dummies and Eq. (4.1) is estimated for at monthly frequency. By construction, the model conditions the predictions for periods on only the information available at time t.14 As in standard recession probability models, we keep all observations in the sample. In spirit, this framework is similar to the local projection proposed by Jordá (2005) where the outcome variable in the future is conditional on the information set available in the present. Table 2 presents the estimates of , as well as fit (the log-likelihood function and the pseudo-) and model selection statistics (the BIC and AIC). Overall, the estimates show a strong and positive relation between the index and future recessions at each time horizon.

Table 2.

Estimation results of Equation (4.1) from 1 to 16 months ahead

| Months ahead |

s.e. | Obs. | Likelihood Log |

AIC | BIC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.93 | 0.34 | 415 | 81.93 | 0.30 | 167.87 | 175.93 |

| 2 | 1.75 | 0.35 | 414 | 84.77 | 0.28 | 173.54 | 181.59 |

| 3 | 1.67 | 0.33 | 413 | 86.74 | 0.26 | 177.48 | 185.53 |

| 4 | 1.74 | 0.35 | 412 | 84.52 | 0.28 | 173.04 | 181.09 |

| 5 | 1.68 | 0.34 | 411 | 86.12 | 0.27 | 176.25 | 184.29 |

| 6 | 1.55 | 0.32 | 410 | 89.48 | 0.24 | 182.96 | 191.00 |

| 7 | 1.39 | 0.29 | 409 | 93.56 | 0.20 | 191.13 | 199.15 |

| 8 | 1.23 | 0.26 | 408 | 97.33 | 0.17 | 198.66 | 206.69 |

| 9 | 1.10 | 0.23 | 407 | 100.04 | 0.14 | 204.08 | 212.10 |

| 10 | 1.06 | 0.23 | 406 | 100.85 | 0.14 | 205.70 | 213.71 |

| 11 | 0.94 | 0.20 | 405 | 103.40 | 0.11 | 210.79 | 218.80 |

| 12 | 0.88 | 0.20 | 404 | 104.35 | 0.11 | 212.70 | 220.70 |

| 13 | 0.86 | 0.19 | 403 | 104.75 | 0.10 | 213.50 | 221.50 |

| 14 | 0.77 | 0.18 | 402 | 106.34 | 0.09 | 216.69 | 224.68 |

| 15 | 0.64 | 0.17 | 401 | 108.58 | 0.07 | 221.15 | 229.14 |

| 16 | 0.48 | 0.15 | 400 | 111.34 | 0.04 | 226.67 | 234.66 |

Coefficients and robust standard errors of Eq. (4.1) estimated at different forecast horizons. The is the pseudo-, AIC and BIC the Akaike and the Bayesian information criteria, respectively

Although the predictive power of the index is statistically significant at all horizons, the link with future recessions is stronger for the medium term (up to 8 months ahead). At longer time horizons, the index shows a consistent statistically significant relation with the probability of future recessions, but explains a relatively small share of the volatility of the dependent variable, as captured by the log-likelihood. Moreover, the predictive power of the indicator decreases stronger at long-term horizons. This most likely reflects the difficulty involved in producing accurate long-term forecasts of recessions using high-frequency indicators and not controlling for macroeconomic fundamentals that determine long-term economic trends.

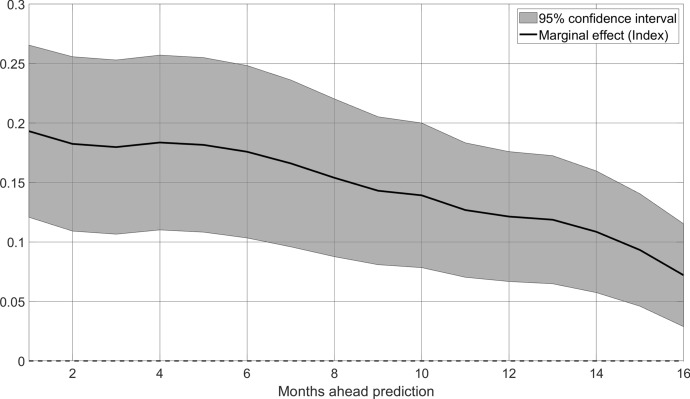

Turning to quantitative estimates, marginal effects describe the increase in the probability of a future recession for a 1% increase in the newspaper-based index. In this model, they are defined as the derivative of the dependent variable for the explanatory variables, i.e., .15 Figure 2 plots the marginal effect of a 1% increase in the index (i.e., the share of articles discussing future recessions rises by 1 p.p.). A 1% increase in the newspaper-based indicator leads to a 20% higher likelihood of a recession in the following next 4 months and an around 10% higher likelihood over a 16-month horizon. The economic significance of these estimates can be understood considering historical episodes. For example, in the run-up to the global financial crisis, the text-based indicator rose by between 1.5 and 2 p.p., implying a 30% to 40% higher probability of a crisis in the succeeding year, see Fig. 1. At longer horizons, the link between our indicator and future recessions however weakens. The same 1% increase in the share of articles discussing a US recession increases probability by only 5% 16 months into the future. The significant drop in the marginal effect coefficient, by three-quarters, shows that at longer future horizons, the text-based indicator constitutes a more ambiguous signal for recessions

Fig. 2.

Marginal effects from Eq. (4.1). Notes: Marginal effects from the probit regression for a 1% increase in the newspaper-based index (i.e., a 1% increase in the share of newspaper articles discussing a recession in the USA). Grey shaded areas report 95% confidence intervals

The above evidence supports the hypothesis that newspaper-based information contain indeed relevant data to study medium-term business cycle fluctuations. To enable comparison with a standard recession model, we estimate Eq. (4.1) replacing the newspaper index with the slope of the US yield curve. Table A.1 and Fig. A.1, in the Online Appendix, present the same results for this alternative model. The comparison with our baseline specification suggests that our proposed indicator captures a different set of information than the yields. Specifically, the yield curve does not correlate with future recessions at short horizons. As a consequence, the newspaper-based index greatly outperforms the fit of the yield curve model up to eight months ahead. At longer horizons, instead, the explanatory power of the yield curve model (as defined by the pseudo- or the log-likelihood) begins to catch up against our baseline specification. Compared to interest rates, the newspaper-based index appears to capture more effectively current events and thus appears to be a strong now-casting tool. On the contrary, the yield curve prices-in faster longer-term expectations than the newspaper index, which gives it stronger predictive power for longer horizons. Therefore, it would seem that the newspaper index and the yield curve are natural complements for recession probability models. These results are confirmed when measures of fit are considered. Both the AIC and the BIC imply that for short- to medium-term estimates, the model based on the newspaper index should be preferred while at longer horizons, they favor the yield curve model.

To formally test whether, indeed, the newspaper-based index and the yield curve are complements, we run a third specification of the model that includes both the index and the slope of the yield curve:

| 4.2 |

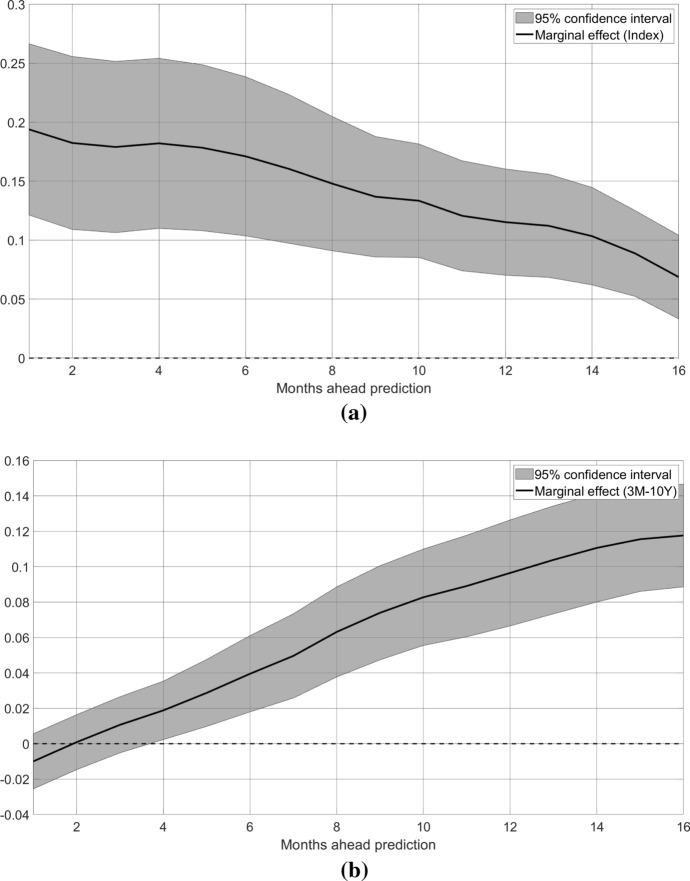

Table 3 and Fig. 3 report the regression coefficients and the marginal effects for each forecasting horizon of Eq. (4.2). They provide several interesting results. First, only the index is significant at all forecasting horizons. This suggests that indeed at short- to medium-term horizons, the yield curve provides no other information additional to what is contained in the newspaper-based indicator. However, at longer horizons, Table 2 implies somewhat weaker correlation of the text-based indicator with recessions compared to yield data. Still, the index remains significant, even when yield-curve data are included in the regression framework. This last result shows that also at longer horizons, the indicator contains some information that are useful for long-term forecasting and that are not already captured by the information present in the spread between the short- and long-term rates. The mirror image of this finding is that when both indicators are included in the model, see Table 3, the overall model fit improves significantly as far as simple metrics such as the pseudo- or the log-likelihood are considered. Model selection criteria, that penalize less parsimonious regressions, also suggest that gains from combining the two variables are particularly sizable at longer horizons. Contrast, for example, the last two columns of Tables 2 and 3: both the AIC and the BIC statistics favor the larger model at medium to long horizons, above 4 months.16 In other terms, model selection criteria again suggest that both variables provide valuable (and different) information on future US business cycle developments. Finally, the elasticities of the recession probability to the index and the yield curve, as measured by marginal effects, are very similar between the baseline model and Eq. (4.2), see Fig. 3. This, again, implies that these two variables contain complementary information on the future of the economy.

Table 3.

Estimation results of Equation (4.2) from 1 to 16 months ahead

| ahead Months |

s.e. | s.e. | Obs. | Likelihood Log |

AIC | BIC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.94 | 0.35 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 415 | 81.42 | 0.31 | 168.84 | 180.92 |

| 2 | 1.75 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 414 | 84.77 | 0.28 | 175.54 | 187.61 |

| 3 | 1.67 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 413 | 86.19 | 0.27 | 178.37 | 190.45 |

| 4 | 1.76 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 412 | 82.72 | 0.30 | 171.44 | 183.50 |

| 5 | 1.73 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 411 | 81.86 | 0.30 | 169.72 | 181.78 |

| 6 | 1.64 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 410 | 81.51 | 0.30 | 169.02 | 181.07 |

| 7 | 1.52 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 409 | 81.48 | 0.30 | 168.96 | 181.00 |

| 8 | 1.43 | 0.27 | 0.61 | 0.13 | 408 | 78.66 | 0.33 | 163.31 | 175.35 |

| 9 | 1.36 | 0.25 | 0.74 | 0.15 | 407 | 75.45 | 0.35 | 156.91 | 168.93 |

| 10 | 1.40 | 0.25 | 0.87 | 0.16 | 406 | 70.98 | 0.39 | 147.96 | 159.98 |

| 11 | 1.29 | 0.26 | 0.95 | 0.18 | 405 | 69.50 | 0.40 | 145.01 | 157.02 |

| 12 | 1.32 | 0.27 | 1.10 | 0.21 | 404 | 64.96 | 0.44 | 135.91 | 147.92 |

| 13 | 1.38 | 0.29 | 1.28 | 0.23 | 403 | 60.24 | 0.48 | 126.47 | 138.47 |

| 14 | 1.32 | 0.30 | 1.41 | 0.24 | 402 | 57.92 | 0.50 | 121.85 | 133.84 |

| 15 | 1.11 | 0.27 | 1.45 | 0.24 | 401 | 58.53 | 0.50 | 123.05 | 135.03 |

| 16 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 1.40 | 0.21 | 400 | 61.48 | 0.47 | 128.96 | 140.94 |

Coefficients and robust standard errors of Eq. (4.2) estimated at different forecast horizons. The is the pseudo-, AIC and BIC the Akaike and the Bayesian information criteria, respectively

Fig. 3.

Marginal effects from Equation (4.2). Notes: Marginal effects , from the probit regression for a 1% increase in the newspaper index (a) and a 1% increase in the slope of the yield curve (b). Grey shaded areas report 95% confidence intervals

A Formal Test for the Goodness of Fit

To formally test the predictive power of the index and compare it to the yield curve, we rely on the so-called Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC)17 analysis, also referred to as the “area under the curve”, which is the most commonly used method to evaluate forecasts of nonlinear outcomes.

In the case of a binary choice, the ROC summarizes the ability of the model to correctly predict the binary outcome, that is, a 0 (1) if a 0 (1) occurs. In a nutshell, the ROC is constructed by computing the true positive rate (i.e., the share of the model’s correct predictions) against the false positive rate (i.e., the share of incorrect predictions). Both rates are defined for a given threshold of the outcome variable, in this case, a level of the predicted probability above (below) which a recession is predicted. Then, the set of true positives and true negatives for different threshold values is plotted as the ROC curve, showing the share of the correct predictions of the model for any given threshold. The ROC curve is generally compared to the 45 degree line (which is the ROC for a random assignment model).18 The more accurate the model is, the farther from the 45 degree line will be its ROC curve since the model’s predictive power should be significantly better than a random choice. Figure A.2 presents these curves for the 1-month and 16-month ahead forecasts.

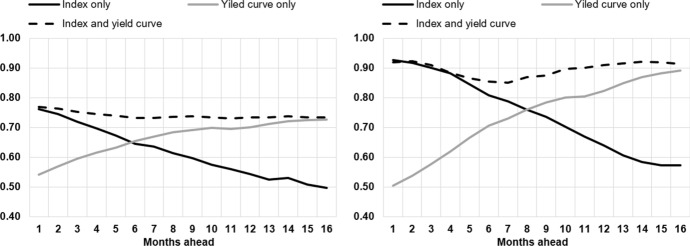

To make comparison easier, the entire ROC curve can be summarized by the so-called ROC statistic, which is defined as the ratio of the area below the ROC curve, but above the 45 degree line, and the total area above the 45 degree line. If the area between the ROC curve and the 45 degree line is large, the model performs significantly better than the random assignment (i.e., its ROC curve lies far away from the 45 degree line). In this way, the ROC statistic captures the accuracy of the model since, in better models, the difference between the two areas would be larger. The ROC statistic is naturally bounded between 0 (a model no different from flipping a coin) and 1 (the perfect model that always delivers correct predictions). Figure 4 reports the ROC statistics for the baseline model, Eq. (4.1), the yield curve model19 and the model including both variables, Eq. (4.2).

Fig. 4.

ROC statistics for the three models (index, yield curve, index and yield curve) at different forecast horizons. Notes: The ROC statistic is computed as the ratio between the area below the ROC line, but above the 45 degree line, and the total area above the 45 degree line. It is naturally bounded between 0, the random assignment model, and 1, the model with all correct predictions

The results depicted in Fig. 4 show several relevant properties of our index. First, Fig. 4 confirms our previous intuition, that the index outperforms the yield curve at medium horizons of one to eight months. At those horizons, the index-based predictions are significantly more accurate than the predictions based on yields (contrast the black and the grey line in the figure).20 Second, although it is true that the index loses some degree of predictive power at longer horizons, after 9 months ahead, the share of accurate forecasts is still relevant up to 13 months ahead. Finally, the model that combines both variables results in “the best of both worlds” as the information provided by the index and the yield curve are complementary and enhance long-term forecasting. In particular, the ROC based on Eq. (4.2) (the black dashed line) follows closely the accuracy of the index-only model for short horizons, leveraging on the strong forecasting properties of the newspaper-based index in the medium term (forecast accuracy is improved compared to the yield curve model by 10 to 40 p.p.). For long-run forecasts, Eq. (4.2) exploits both indicators; the ROC statistic relative to the yield curve model is improved by about 15 p.p. for the 8- to 11-month ahead prediction, and by about 10 p.p. for horizons of more than 12 months.

Predicted Recessions

Equations (4.1) and (4.2) can be used to compute implied recession probabilities at different horizons. Figure 5 reports the implied probabilities at the 1- to 12-month horizons for the three models considered previously. The first, second and third rows show the predictions of the index-only model, the yield curve model and the combined model, respectively. As Table 2 suggests, the index-based model performs well for medium horizons; consider, for example, the third chart in the first row of Fig. 5. This is a remarkable result since, considering that when the model identifies a recession in a given month, the NBER has yet to define the beginning of a recession period (the NBER requires 2 quarters, i.e., 6 months, of consecutive contraction to mark the beginning of a recession). However, at longer horizons (fourth graph in the first row), Eq. (4.1) delivers less accurate results and generates more false-positives (i.e., incorrect prediction of recessions).

Fig. 5.

Predicted recession probabilities at different forecast horizons. Notes: recession probabilities are computed based on Equation (4.1), for the index and the yield curve models, and on Equation (4.2) for the model including both the yield curve and the index

Forecasts based on the index are on average more accurate than those based on the yield curve model (compare rows 1 and 2 in Fig. 5). The yield curve model fails to pick up recessions at 1 and 4 months ahead horizons and, at 8- and 12-month horizons, the yield curve implies a significant share of false-positives (e.g. in the period 2003-2005) and larger than implied by the index-based model. Finally, the third row in Fig. 5 shows the implied recession probabilities based on Eq. (4.2). This model outperforms both specifications—particularly at longer horizons. For instance, the last graph in row 3 of Fig. 5 shows the 12-month ahead prediction; Eq. (4.2) sends more accurate signals ahead of the 2008 recession compared to the other two specifications and, also, does not produce the same number of false positives as implied by the yield curve model.

Robustness and Comparison with Other Recession Indicators

Results reported in Sects. 4.1 and 4.2 are robust to different changes to the model. Our proposed indicator, moreover, improves the recession forecast of several more recent US business cycle indicators.

Different estimation method. Our first robustness check is to change estimation method. We re-estimate Eqs. (4.1) and (4.2) using a logit instead of a probit model. Logistic regressions have several practical advantages, including the assumption that residuals are not necessarily normally distributed and there is no requirement for homoscedasticity. Also, in a logit framework, the coefficients can be interpreted directly as marginal effects. These characteristics relax some of the assumptions imposed in our baseline specification. However, logistic models require observations to be independent of each other, that is, they must not be repeated measures derived from the same data generating process (such as GDP) making them less suited for the analysis of time series data. For this reason, our preferred choice for Eq. (4.1) is the probit model. However, our main results are unchanged when moving to a logistic framework. Table A.2 and Table A.3 in the Online Appendix report the estimated coefficients, fit statistics and model selection criteria for the logistic regression, which are broadly consistent with the baseline estimates presented earlier. Also, the ROC statistics, plotted in Fig. 6, are in line with our baseline results and the implied recession probabilities are qualitatively similar to the baseline model, with the logistic estimation exhibiting higher uncertainty, resulting in more volatile implied probabilities and more false-positives and negatives, see Fig. A.3.

Fig. 6.

ROC statistic for the three models (index, yield curve, and index and yield curve) at different forecast horizons, estimated with a logit regression. Notes: The ROC statistic is computed as the ratio between the area below the ROC line, but above the 45 degree line, and the area above the 45 degree line. It is naturally bounded between 0, the random assignment model, and 1, the model with all correct predictions

Different definitions of recession. As a second robustness exercise, we change the definition of recession. The NBER defines a recession as ”... a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.”21, thus weighing different indicators and measures of the business cycle. In most cases, the NBER requires at least two consecutive quarters of contraction to mark the beginning of a recession period. As a robustness exercise, we change the definition of a recession to four or eight consecutive months of IP contraction and re-estimate Eq. (4.1) and Eq. (4.2) using this alternative dependent variable. These alternative definitions have also the practical advantage of increasing the number of recession periods in the sample considering a larger number of episodes that are related to cyclical slowdowns of US real activity.22

Our main results are robust to this change in recession definition, suggesting that the newspaper-based index captures rich information on the US economy. Figure 7 plots the ROC statistics for both models and confirms the baseline result of the index as superior to the yield curve for medium horizons. Results also show that there are improvements to forecasts at all horizons when these two indicators are combined. Similar conclusions are reached considering the estimated coefficients or regression measures of fit, which are reported in Table A.4 to Table A.7 in the Online Appendix. Predicted recessions are also consistent with the baseline estimates. Notably, the model picks up the 1991 recession, although it is not identified as such using the IP-based definition, see Fig. A.5.

Fig. 7.

ROC statistics for the three models (index, yield curve, index and yield curve) at different forecast horizons and definition of recessions. Notes: In the left panel, a recession is defined as 4 consecutive months of IP contraction; in the right panel, a recession is defined as 8 consecutive months of contraction. The ROC statistic is computed as the ratio between the area below the ROC line, but above the 45 degree line, and the area above the 45 degree line. It is naturally bounded between 0, the random assignment model, and 1, the model with all correct predictions

Accounting for APP distortions. Since the 2008 global financial crisis, all major central banks implemented APPs, which have compressed the value of global safe assets, and particularly, US treasuries. This could have important consequences for recession forecasting. First of all, it might distort the historical relation between the yield curve and recessions, resulting in less accurate yield-based forecasts because the slope of the yield curve is flattened by central bank purchases rather than expectations on the economic outlook. This could imply that the yield curve produces more false-positives that in the absence of APP, see Engstrom and Sharpe (2018).23 In turn, the comparison between the yield curve model and the index-based model might be biased (i.e., in the latest part of the sample, the yield curve model might show an artificially higher ratio of false-positives).

There is also another, more subtle, channel through which central bank interventions might affect our estimates. The historical relation between the flattening of the yield curve and recessions is well-known and commonly discussed on economic columns. If the yield curve has flattened in recent years as the result of central bank actions, this might have been discussed by economic commentators, who might have referred to the relation between the yield curve and past US recessions. As a result, our index (which is computed as the share of articles discussing US recessions among all articles published) might be artificially inflated and might provide biased results for the post global financial crisis period. To tackle these issues, we conduct three robustness exercises.

First, we introduce a dummy for the APP period, which is interacted with other coefficients. Formally, we modify Eqs. (4.1) and (4.2) as follows:

| 4.3 |

| 4.4 |

Where is a dummy that takes the value 1 for the period post-November 2008, when the Fed first started quantitative easing (QE) interventions. This is a simple way to account for possible nonlinearities in the APP period since the interaction terms should capture exactly the changed relation between the dependent variables and the NBER recession dummies during the APP period.24 Second, we correct the time series for the slope of the yield curve to account for APP effects and use the corrected series for the estimation. This is in line with Gräb et al. (2019).25 Third, we exclude from the newspaper-based index all articles discussing the yield curve. This means that all sources of interaction between the lower interest rate environment and recessions are excluded automatically. Although this choice excludes several potentially relevant information on the US business cycle, it has the advantage of producing more conservative estimates, that can be considered as a lower bound to our findings. If the main results hold with this definition of the index, they cannot be driven by distortions to the yield curve induced by central bank interventions.

Figures A.6, A.7 and A.8 report the respective ROC statistics for the three robustness exercises. Our results are mainly unchanged under these three alternative specifications. Most important, the ROC statistics lead to the same conclusions as in the baseline specification: the index outperforms the yield curve at medium horizons and the model featuring both our index and the yield curve improves the statics by between 5% and 30% depending on the horizon considered. In the Online Appendix, we also report the full regression tables for these alternative models; the estimated coefficients remain broadly stable relative to baseline estimates while measures of fit, such as the log-likelihood or the pseudo-, or model selection criteria do not imply a strong preference for any of these specifications.

Alternative business cycle indicators. There are some alternative business cycle indicators that have been shown to have robust forecasting properties. Hwang (2019), for example, compares the forecasting accuracy of financial data, employment statistics and surveys. The “excess bond premium,” proposed by Gilchrist and Zakrajšek (2012), has also been shown to be a good leading indicator for the US business cycle.26 The Ardia et al. (2019) and Shapiro et al. (2020) indices—also based on text sentiment analysis—have proved successful for forecasting US IP and consumer confidence, respectively. To compare our findings against them, we estimate Eq. (4.1) using some of these alternative measures to predict future US recessions. More formally, we estimate:

| 4.5 |

where is a matrix of the alternative indicators and is a vector of the loadings. We consider six sets of leading indicators: S &P500 and the 3-month Libor-TBill spread; unemployment rate and weekly hours worked; the Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) and the Michigan consumers’ confidence survey; the Gilchrist-Zakrajšek excessive bond premium and term spread; the Ardia et al. (2019) index and the Shapiro et al. (2020) index.

Figure 8 compares the ROC from these alternative models with our baseline framework where only the text-based indicator is used, Eq. (4.1). Excluding financial data and surveys, that benefit from more estimated parameters and therefore higher degrees of freedom, our index outperforms other variables at short to medium horizons. At longer horizons, other forecast indicators deliver more accurate results, for example the indices by Ardia et al. (2019) or Shapiro et al. (2020). A similar pattern emerges when recessions are defined based on IP contractions, see Fig. A.9 in the Online Appendix. These results are not surprising, as our index is unidimensional and uses a simple methodology, while the alternative indicators combine several data sources. It might also reflect the rapid inclusion of short-term news into the newspaper-based index compared to some of the alternative variables proposed that, instead, capture more effectively long-term trends.

Fig. 8.

ROC statistics for the models described by Eqs. (4.2) and (4.5) at different forecast horizons estimated with a probit regression. Notes: The ROC statistic is computed as the ratio between the area below the ROC line, but above the 45 degree line, and the area above the 45 degree line. Financial variables include the S &P500 and the 3-month Libor-TBill spread; employment variables include the unemployment rate and weekly hours worked; surveys include the PMI index and the Michigan consumers’ confidence survey; EBP includes the excess bond premium and the terms spread proposed by Gilchrist and Zakrajšek (2012)

We subsequently test whether our text-based indicator contains additional information relative to the variables included in Fig. 4.5, i.e., whether forecasts improve when the index is included along the aforementioned variables, by adding our indicator to the regression:

| 4.6 |

For each set of variables considered, we contrast the ROC statistic of the baseline, Eq. 4.5, against the augmented model (Eq. 4.5) in Fig. 9. Including the text-based indicator improves the forecast accuracy of all indices both at short- and long-term horizons, with improvements ranging from 2 to 40 percentage points depending on the variable and the horizon considered. The largest gains are recorded when the index complements employment data and the Ardia et al. (2019) indicator. Similarly to the yield curve, these results suggest that indeed our text-based measure provides information that are not already present in the business cycle indicators considered and, therefore, appears to be a natural complement to them when forecasting recessions. Figure A.10 in the Online Appendix repeats the same analysis defining recessions based on IP contractions. Our findings are broadly robust to this alternative specification, with all models becoming relative less efficient in forecasting. In other terms, all ROC curves are materially lower, signaling for all models a higher share of false predictions.

Fig. 9.

ROC statistics for the models described by Eqs. 4.5 and 4.6, which includes the text-based indicator, at different forecast horizons estimated with a probit regression. Notes: The ROC statistic is computed as the ratio between the area below the ROC line but above the 45 degree line and the area above the 45 degree line. Financial variables include the S &P500 and the 3-month Libor-TBill spread; employment variables include the unemployment rate and weekly hours worked; surveys include the PMI index and the Michigan consumers’ confidence survey; EBP includes the excess bond premium and the terms spread proposed by Gilchrist and Zakrajšek (2012)

Out-of-sample forecasts. The recession probabilities reported in the previous section are based on in-sample forecasting, that is, they are the fitted values of Eqs. (4.1) and (4.2), respectively, when parameters are estimated on the entire sample. In contrast, real-time forecasting implies that the forecast of a future recession is based on parameters estimated only on past data. In this case, the model performance can vary since large recession episodes can significantly change parameter estimates. To verify the real-time forecasting properties of the news-based index, we consider two major recession episodes, the 2008 global financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic, to evaluate the model performance and produce real time forecasts before those periods.27 Overall, our empirical model predicts the 2008 recession with a good level of accuracy, see Fig. A.11, in particular under the specification that includes both the yield curve and the index, at the 1, 4, 8 and 12 months horizon. However, the model fails to forecast the Covid-19 recession (Fig. A.12), i.e., implied recession probabilities were low only a few months before the outbreak of the pandemic. This emphasizes the unique nature of the Covid-19 crisis where non-economic factors, that is, a global pandemic, triggered an unprecedented fall in global demand and trade. Since this pandemic-induced contraction was largely unrelated to past macroeconomic dynamics, models based on historical regularities could not forecast it.

Conclusion

In this paper, we develop a text-based indicator to trace US economic activity slowdowns. The index is based on the share of newspaper articles per day that discuss a recession in the USA. This approach, which, essentially, extends Baker et al. (2016) methodology to real variables, has several advantages: first, it is easy to replicate and does not require complex computational techniques; second, the indicator can be scaled easily to any country with the relevant newspaper information; third, the indicator can be updated daily and employed for now-casting and monitoring of high-frequency developments; fourth, the index contains a set of rich economic information not necessarily captured by financial market data.

We test the properties of the index in a standard recession probability model, which shows that the index outperforms the standard yield curve model at medium horizons (up to 8 months). We show, also, that the text-based index adds relevant information on top of what is implied by the slope of the yield curve at all forecast horizons. We test this formally, using ROC statistics; we find that the model that includes both the index and the yield curve outperforms the other models by between 5% and 40% depending on the forecast horizon and the variables considered. Our results are robust to a range of robustness checks including different estimation methods, a different definition of recession and, most important, accounting for distortions induced by APP. Finally, we show that the text-based index adds additional information relative to what implied by more sophisticated forward-looking indicators for the US economy, improving the forecast accuracy of these models.

This paper, in conclusion, shows the potential of high-frequency textual analysis methods to forecast real economic activity. These methods include a wide range of economic information, such as hard data on production to consumers survey data, in a single indicator, which complements the information provided by existing alternative sources. The results of our estimations are promising; we leave the integration of our index in more complex forecasting models based, for example, on smooth transitions or Markov chains, to future research.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Biographies

Massimo Ferrari Minesso

is a senior economist in the International Policy Analysis Division of the European Central Bank (ECB) and a research fellow of the Complexity Lab in Economics. He holds a PhD in Economics from the Catholic University of Milan. His research interests are mainly in macro-finance, international macroeconomics and monetary economics.

Laura Lebastard

is an economist in the Euro Area External Sector & Euro Adoption Division of the European Central Bank (ECB). She holds a PhD in Economics from University Paris-Saclay. Her research interests are mainly in international trade and international macroeconomics.

Helena Le Mezo

currently works as an analyst in the International Department of the European Central Bank. She holds a Master’s degree in Economics from the Toulouse School of Economics.

Footnotes

Kearns et al. (2018) show that monetary policy spillovers on yields are stronger for economies, such as the US, that are more financially integrated. See Pescatori and Turunen (2016) and Ferrari et al. (2021) for a discussion of how these spillovers have changed in a “low-for-long” environment.

Another explanation would be that market participants expect a recession in the future and agents rebalance their portfolios by acquiring safe assets. This leads to a rise in the price of bonds and a consequent fall in their remuneration.

See Favara et al. (2016) and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, NBER-based Recession Indicators for the United States from the Period following the Peak through the Trough [USREC], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USREC.

There is a large literature that tries to estimate the distortions generated by asset purchases on the yield curve and the implications for recession forecasts. Among the numerous works on this topic see: Engstrom and Sharpe (2018), Christensen (2018), Bauer and Mertens (2018b), Bauer and Mertens (2018a) and Gräb and Tizck (2020). However, at the same time, Chauvet and Potter (2002) Chauvet and Potter (2005) find evidence of breaks in the relation between the yield curve and economic activity.

Other examples are text-based indices, such as Shapiro et al. (2020) and Ardia et al. (2019) or financial market data Davis et al. (2022).

Taylor and McNabb (2007) investigate the role of consumer and business confidence for 4 European economies and find that sentiment variables matter for the prediction of recessions. More recently, Christiansen (2012) shows that sentiment variables improved both in-sample and out-of-sample performance of recession prediction models significantly and, especially, when paired with common recession predictors. Davis et al. (2022) evaluate the effectiveness of stock prices for the prediction of real activity during the Covid-19 pandemic. Candelon et al. (2012) provides a comparison between different frameworks.

A topic model categorizes words into a predetermined numbers of categories (the topics) depending on which words or group of words (N-grams) tend to appear together in the documents considered. The number of topics is defined a-priori by the researcher and the allocation is based on a numerical optimization algorithm. As a consequence, the words and N-grams included in each topic can depend on the number of topic chosen and the underlying optimization process.

Factiva collects news from 32,000 different sources including, among many others, The Wall Street Journal, the New York Times as well as Dow Jones articles.

This methodology is similar to The Economist’s R-word index. See Gauging the gloom, The Economist, Sep. 2011.

The NBER defines a recession as “two consecutive quarters of negative real gross domestic product (GDP) growth,” see The NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Procedure.

Other relevant examples are: King et al. (2007), Chen et al. (2011) and Johansson and Meldrum (2018).

The properties of these models are discussed in Estrella et al. (2003).

In addition, agents do not know if they are entering a recession in period t since, by construction, NBER recessions are announced with a lag of 2 quarters. As a result, the NBER announcement of a recession period is likely to be exogenous to the index in t.

Given the nonlinear nature of the estimator, they capture the change in the probability of a positive outcome for a unitary increase in that specific regressor (keeping the others constant).

For the case of model with yields only, reported in Table A.1 of the Online Appendix, the combine models is instead preferred at all horizons by the information criteria.

This statistic takes its name from radar controls. The ROC was first used during World War II in the context of analyzing of radar signals to quantify the ability of operators to correctly identify incoming aircrafts. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the US army embarked on some new research to increase the accuracy of detection of Japanese aircrafts. Specifically, US officials measured the ability of a radar receiver operator to distinguish between enemy aircraft (true positives) and noise (false positive) when reading the radar signals. The resulting ratio, between accurate and wrong calls, was termed the “Receiver Operating Characteristic.” Since then, the method has been used widely in statistics to quantify the level of true predictions delivered by models for nonlinear outcomes.

The 45 degree line represents the ROC curve for a random prediction model where both outcomes have the same probability of being chosen. In reality, in a binary model, the share of correct predictions from the random model (50%) does not depend on the value of the threshold.

The specification of the yield curve model is reported in Eq. (A.1) in Appendix A.

This result confirms the preliminary evidence in Table 2 and Table A.1.

See The NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Procedure: Frequently Asked Questions.

It has often been argued that binary models based on NBER recession dates suffer from the limited number of “positive” outcomes in the sample. Relaxing the recession period definition allows for a larger number.

However, other studies suggest that central bank APPs have only a limited impact on recession probability models based on the slope of the yield curve, see Bauer and Mertens (2018a), Bauer and Mertens (2018b), Christensen (2018) and Debortoli et al. (2019).

Notice, however, that after 2010, all recessions become collinear with the QE dummy, therefore Figs. 4.3 and 4.4 cannot be estimated at longer horizons, after seven months in the future.

They estimate an autoregressive distributed lag model for the US term premium. In this model, the term premium is regressed on foreign central bank holdings, domestic central bank holdings and country-specific fundamentals including level and volatility of growth and inflation. The corrected series are the fitted values derived from the regression.

In practice, we estimate the model using data up to these recessions and assess the implied recession probabilities for these episodes.

We would like to thank Michele Ca’ Zorzi, Georgios Georgiadis, Johannes Gräb, Marek Jarocinski, Michele Lenza, David Lodge, Arnaud Mehl, Maria Sole Pagliari, Bernd Schnatz, and participants to seminars at the ECB and the COMPNET 2020 conference. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of either the European Central Bank or the ESCB. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Massimo Ferrari Minesso, Email: massimo.ferrari_minesso@ecb.europa.eu.

Laura Lebastard, Email: Laura.Lebastard@ecb.europa.eu.

Helena Le Mezo, Email: Helena.Le_Mezo@ecb.europa.eu.

References

- Ang A, Piazzesi M, Wei M. What does the yield curve tell us about GDP growth? Journal of Econometrics. 2006;131(1–2):359–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2005.01.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardia D, Bluteau K, Boudt K. Questioning the news about economic growth: Sparse forecasting using thousands of news-based sentiment values. International Journal of Forecasting. 2019;35(4):1370–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.ijforecast.2018.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker RS, Bloom N, Davis SJ. Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2016;131(4):1593–1636. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjw024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor R, Dua P. Improving macro-economic forecasts: The role of consumer confidence. International Journal of Forecasting. 1998;14:71–81. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2070(97)00052-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M. D., and T. M. Mertens. 2018a. Economic forecasts with the yield curve. FRBSF Economic Letter,

- Bauer, M. D., and T. M. Mertens. 2018b. Information in the yield curve about future recessions. FRBSF Economic Letter

- Benzoni, L., Chyruk, O., and D. Kelley. 2018. Why does the yield-curve slope predict recessions? Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Working Paper, pages 2018–15

- Burri M, Kaufmann D. A daily fever curve for the Swiss economy. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics. 2020;156(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s41937-020-00051-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, L., Kelly, B. T., Manela, A., and D. Xiu. 2021. Business News and Business Cycles. NBER Working Papers, 29344

- Caldara, D., and M. Iacoviello. 2018. Measuring geopolitical risk. International Finance Discussion Papers, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.), 1222

- Caldara D, Iacoviello M, Molligo P, Prestipino A, Raffo A. The economic effects of trade policy uncertainty. Journal of Monetary Economics. 2020;109:38–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoneco.2019.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Candelon B, Dumitrescu E-I, Hurlin C. How to evaluate an early-warning system: Toward a unified statistical framework for assessing financial crises forecasting methods. IMF Economic Review. 2012;60(1):75–113. doi: 10.1057/imfer.2012.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet M, Potter S. Predicting a recession: evidence from the yield curve in the presence of structural breaks. Economics Letters. 2002;77(2):245–253. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1765(02)00128-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet M, Potter S. Forecasting recessions using the yield curve. Journal of Forecasting. 2005;24(2):77–103. doi: 10.1002/for.932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Iqbal A, Lai H. Forecasting the probability of US recessions: a probit and dynamic factor modelling approach. Canadian Journal of Economics. 2011;44(2):651–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5982.2011.01648.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, J. H. E. 2018. The slope of the yield curve and the near-term outlook. FRBSF Economic Letter

- Christiansen C. Predicting severe simultaneous recessions using yield spreads as leading indicators. International Journal of Forecasting. 2012;32:1032–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Davis SJ, Liu D, Sheng XS. Stock prices and economic activity in the time of coronavirus. IMF Economic Review. 2022;70(1):32–67. doi: 10.1057/s41308-021-00146-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Lindt RC, Stolin D. Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Journal of Monetary Economics. 2003;50:1603–1622. [Google Scholar]

- Debortoli, D., Galí, J., and L. Gambetti. 2019. On the empirical (ir)relevance of the zero lower bound constraint. In NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2019, volume 34, NBER Chapters, pages 141–170. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, May

- Engstrom, E., and S. A. Sharpe. 2018. The near-term forward yield spread as a leading indicator : A less distorted mirror. Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.), (2018-055)

- Estrella, A., and G. A. Hardouvelis. 1991. Term structure as a predictor of real economic activity. Journal of Finance, 2(46)

- Estrella, A., and F. S. Mishkin. 1996. The yield curve as a predictor of US recessions. Current Issues in Economics and Finance, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2

- Estrella A, Rodrigues A, Schich S. How stable is the predictive power of the yield curve? evidence from Germany and the united states. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2003;85(3):629–644. doi: 10.1162/003465303322369777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fama EF. Term premiums and default premiums in money markets. Journal of Financial Economics. 1986;17(1):175–196. doi: 10.1016/0304-405X(86)90010-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Favara, G., Gilchrist, S., Lewis, K. F., and E. Zakrajšek. 2016. Updating the recession risk and the excess bond premium. FEDS Notes

- Ferrari, M., Kearns, J. and A. Schrimpf. 2021. Monetary policy’s rising FX impact in the era of ultra-low rates. Journal of Banking & Finance 129(C).

- Gholampour, V., and E. van Wincoop. 2019. Exchange rate disconnect and private information: What can we learn from euro-dollar tweets? Journal of International Economics, 119(C): 111–132

- Gilchrist S, Zakrajšek E. Credit spreads and business cycle fluctuations. American Economic Review. 2012;102(4):1692–1720. doi: 10.1257/aer.102.4.1692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gröb, J., and S. Tizck. 2020. Estimating recession probabilities with a less distorted term spread. ECB Mimeo.

- Gräb, J., T. Kostka, and D. Quint. 2019. Quantifying the “exorbitant privilege” - potential benefits from a stronger international role of the euro. In The international role of the euro 2019. European Central Bank.

- Hansen S, McMahon M, Prat A. Transparency and deliberation within the fomc: A computational linguistics approach. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2018;133(2):801–870. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjx045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Y. 2019. Forecasting recessions with time-varying models. Journal of Macroeconomics, 62

- Johansson, P., and A. C. Meldrum. 2018. Predicting recession probabilities using the slope of the yield curve. FEDS Notes

- Jordá O. Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections. American Economic Review. 2005;95(1):161–182. doi: 10.1257/0002828053828518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamara, E., Turrell, A., Redl, C., Kapetanios, G., and S. Kapadia. 2020. Making text count: economic forecasting using newspaper text. Bank of England working papers, 865.

- Ke, Z. T., Kelly, B. T., and D. Xiu. 2019.Predicting returns with text data. NBER Working Papers, 26186.

- Kearns, J., Schrimpf, A., and D. Xia. 2018. Explaining monetary spillovers: The matrix reloaded. BIS Working Papers, (757).

- Kessel, R. A. 1965. Explanations of the term structure of interest rates. In R. A. Kessel, editor, The Cyclical Behavior of the Term Structure of Interest Rates. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- King, T. B., Levin, A. T., and R. Perli. 2007. Financial market perceptions of recession risk. Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2007-53.

- Liu, W., and E. Moench. 2016.What predicts US recessions? International Journal of Forecasting, 32(4).

- Matsusaka JG, Sbordone AM. Consumer confidence and economic fluctuations. Economic Inquiry. 1995;33:296–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.1995.tb01864.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minesso Ferrari, M., Kurcz, F., and M. S. Pagliari. 2020. Do words hurt more than actions? ECB Working Papers.

- Mody A, Taylor MP. The high-yield spread as a predictor of real economic activity: evidence of a financial accelerator for the united states. IMF Staff papers. 2003;50(3):373–402. [Google Scholar]

- Pescatori A, Turunen J. Lower for longer: Neutral rate in the US. IMF Economic Review. 2016;64(4):708–731. doi: 10.1057/s41308-016-0017-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, A. H., Sudhof, M., and D. J. Wilson. 2020. Measuring News Sentiment. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper Series, (2017-1).

- Stock JH, Watson MW. Forecasting output and inflation: the role of asset prices. Journal of Economic Literature. 2003;41(1):788–829. doi: 10.1257/jel.41.3.788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K, McNabb R. Business cycles and the role of confidence: Evidence for europa. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 2007;2018–15(2):185–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0084.2007.00472.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J. H. 2006. The yield curve and predicting recessions. Finance and Economics Discussion Serie, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.), 2006-07.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.