Abstract

Objective

This scoping review aimed to present an overview of the literature on communication tools in esthetic dentistry. A variety of communication tools have been proposed to include patients in the shared decision‐making (SDM) workflow. Only little is known about implementing communication tools in dentistry and their impact on patient communication and patient satisfaction. A systematic literature search was performed in Medline, Embase, Cochrane, and World of Science to identify if communication tools have an impact on patient satisfaction.

Material and Methods

The search included studies from January 1, 2000 to March 3, 2020 published in English, focusing on patient communication tools and patient satisfaction in esthetic dentistry.

Results

Out of 6678 records, 53 full‐texts were examined. Ten studies were included. Data of the included studies were extracted systematically and subsequently analyzed. All studies found that patient communication utilizing specific communication tools positively impacted either patient satisfaction, patient‐dentist relationship, information retention, treatment acceptance, quality of care or treatment outcome.

Conclusions

Additional communication tools besides conventional verbal communication are able to enhance patient satisfaction, improve quality of care and establish a better patient‐dentist relationship. It seems essential to further develop standardized communication tools for SDM in dental medicine, which will allow the comparison of research on this topic.

Clinical significance

This scoping review shows the importance of patient involvement in the decision‐making process for improved patient satisfaction with esthetic dental treatments. With an increased implementation of communication tools, patient satisfaction and SDM may further improve in the future.

Keywords: esthetic dentistry, patient communication tools, patient satisfaction, scoping review, shared decision making

1. INTRODUCTION

Patients desiring to improve their dental esthetics often face difficulties imagining potential treatment outcomes, as they cannot oversee all available possibilities regarding their final dental appearance. 1 Therefore, the diagnostic phase is of great importance for the patient, dentist and, dental technician to understand the patients' desires and expectations. 2 , 3

Within the last years, patient behavior evolved towards a more inclusive attitude regarding the decision‐making process. 4 , 5 This innovative patient‐dentist relationship, in contrast to the previously established paternalistic model, is characterized by a shared involvement of the patient and the clinician in the process of treatment decision–making, known as shared decision‐making (SDM). 6 , 7 The two main goals of SDM are to inform patients comprehensively about different treatment possibilities and to understand patients' preferences and demands related to proposed options. 7 Integrating the patient into the decision‐making process demonstrates respect towards the patient and was reported to increase the patient's overall health, well‐being, self‐esteem, quality of health care, and satisfaction. 8 , 9 , 10

A variety of communication tools were proposed to include patients in the SDM workflow. 11 In a conventional workflow, tools such as a manual wax‐up of the desired dental shapes and sizes onto a stone cast can be used for communication. This proposition by the dental technician may subsequently be visualized by performing a clinical mock‐up try‐in. 12

Recently, technological developments were proposed for the digital workflow, such as 2D/3D smile design or augmented reality (AR) software. 11 , 13 , 14 In 2016, the first international Delphi Consensus Process was performed to develop a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids. 15 Based on the work of the Cochrane Collaboration's systematic review group, the scope was to define quality standards for the development and evaluation of decision aids. A need for improved management of clinical decision‐making and measurable quality improvement was stated to achieve patient‐centered and efficient health care. However, only little is known about implementing communication tools in dentistry and their impact on information and communication with the patient. 13 , 16

This scoping review aimed to present an overview of the literature regarding the impact of communication tools in esthetic dentistry. A selection of studies evaluating patients' satisfaction was performed to identify if communication tools applied before/during the treatment could bring medical benefits.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

For the present review, PRISMA extension for scoping reviews was followed. 17

(1) Identification of the research question, (2) Identification of relevant studies (database and keywords), (3) Determination of inclusion and exclusion criteria, (4) Data extraction, (5) Summary of the results.

3. IDENTIFICATION OF THE RESEARCH QUESTION

This review aimed to analyze studies published in the field of esthetic dentistry which examined the use of communication strategies/tools (verbal/visual/device) for patient information and treatment planning and its' influence on patient satisfaction with the final treatment outcome.

4. IDENTIFICATION OF RELEVANT WORK

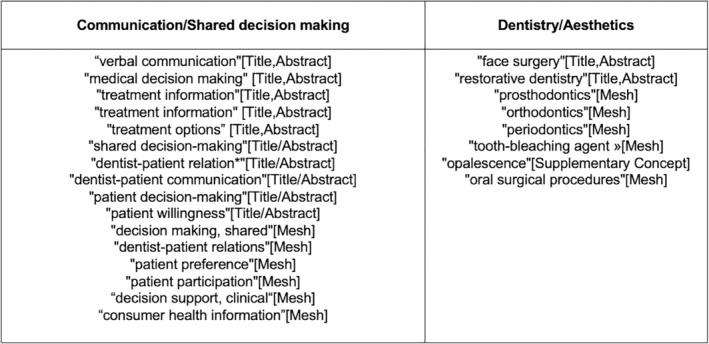

Two main fields were identified: “communication of a certain treatment plan or SDM” and “esthetic dentistry.” A derivative sequence of keywords and free terms was developed thereafter (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Derivative sequence of key words

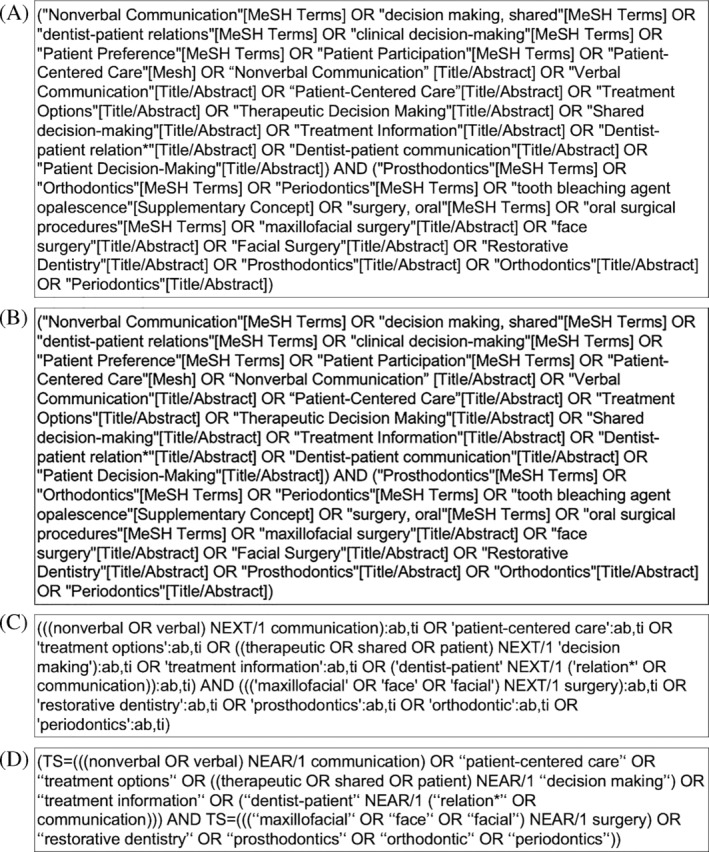

To identify potentially relevant studies, the following bibliographic databases were searched: Medline, Embase, Cochrane, and World of Science from January 1, 2000 to March 3, 2020. The search strategies were drafted by an experienced librarian (MVB) and further refined through team discussions (Figure 2A–D). The final search results were exported into EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, London, UK), and duplicates were removed using Covidence (Covidence, Melbourne, Australia).

FIGURE 2.

(A) Search strategy developed for Pubmed. (B) Search strategy developed for Embase. (C) Search strategy developed for Cochrane. (D) Search strategy developed for Web of Science

5. DETERMINATION OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA

The inclusion criteria were: clinical studies in English language, involving human subjects published between January 1, 2000 and March 3, 2020. Only peer‐reviewed studies were included. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Not a clinical study (excluding case reports); studies involving less than 10 participants; (2) studies not conducted in the field of esthetic dentistry; (3) studies not focusing on patient‐dentist communication; (4) studies not focusing on patient satisfaction; (5) studies not written in English.

6. DATA CHARTING

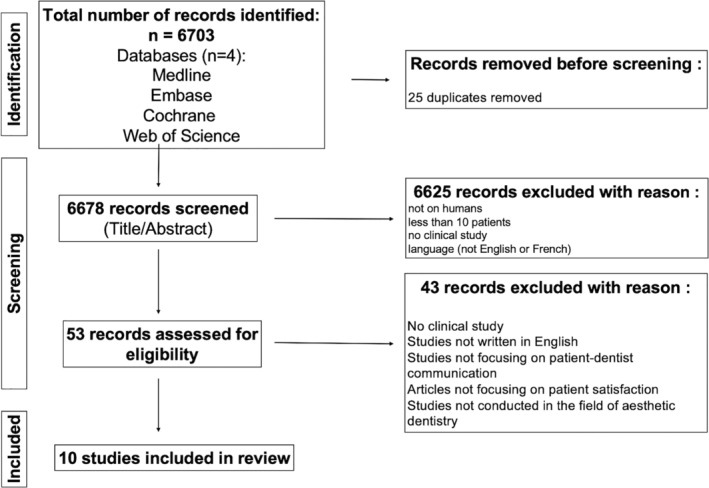

To ensure consistency of the reviewing process, all authors first screened the first 50 publications, randomly selected, through a systematic review management software (Covidence, Melbourne, Australia), discussed the results, and extracted data manually. Two reviewers (Malin Strasding and Romane Touati) sequentially evaluated the titles and thereafter the abstracts using the software as mentioned earlier. Afterward, three reviewers (Malin Strasding, Romane Touati, and Laurent Marchand) evaluated the full texts for potentially relevant studies. Disagreements on study selection were resolved by consensus and discussion with another author (Irena Sailer). (See Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Identification of relevant studies

7. DATA EXTRACTION

A data‐extraction form was jointly developed by the authors (Malin Strasding (MS), Romane Touati (RT), and Laurent March and (LM) to determine which variables to extract. The three authors independently extracted the data, discussed the results, and continuously updated the data‐extraction form in an iterative process.

Studies were classified in a table into 13 different categories (see Table 1 and Table 2): Study design; Field of specialization; Country; Study settings (university/private dental clinic/public health sector); Study period; Patient age; Gender distribution; Number of patients enrolled; Purpose of the study; Main findings; Tools used for patient‐dentist communication (verbal, written, visual, digital); Methodology for assessment of patient satisfaction; Details of the assessment method. The studies were divided into two groups regarding the satisfaction assessment method. The first group included structured questionnaires using yes/no questions or Lickert's scale and the second group included semistructured questionnaires (SSQ) as defined for qualitative studies. 18 , 19 According to this definition, structured questionnaires were using close‐ended questions where the patient can only choose between the different possibilities given by the interviewer, whereas SSQ gave the respondent the possibility to answer in his/her own words. 18 , 19

TABLE 1.

Extracted data of included articles 1–5

| Article number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General information | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Title | Introduction and assessment of orthognathic information clinic | The dentist's communicative role in prosthodontic treatment | Dentist‐patient communication and patient satisfaction in prosthetic dentistry | Factors influencing satisfaction with the process of orthodontic treatment in adult patients | Orthognathic surgery: Pretreatment information and patient satisfaction |

| Authors | Bergkulla, N.; Hanninen, H.; Alanko, O.; Tuomisto, M.; Kurimo, J.; Miettinen, A.; Svedstrom‐Oristo, A. L; Cunningham, S.; Peltomaki, T. | Sondell, K.; Palmqvist, S.; Soderfeldt, B. | Sondell, K.; Soderfeldt, B.; Palmqvist, S. | Wong, L; Ryan, F. S.; Christensen, L. R.; Cunningham, S. J. | AlKharafi, L; AlHajery, D.; Andersson, L. |

| Journal | European Journal of Orthodontics | International Journal of Prosthodontics | International Journal of Prosthodontics | American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics | Medical Principles and Practice |

| Year of publication | 2017 | 2004 | 2002 | 2018 | 2014 |

| Reference | Eur J Orthod. 2017 Nov 30;39(6):660–664 | Int J Prosthodont. 2004 Nov‐Dec;17(6):666–71 | Int J Prosthodont. 2002 Jan‐Feb;15(1):28–37 | Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018 Mar;153(3):362–370 | Med Princ Pract. 2014;23(3):218–24 |

| Study information | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Cohort study | Cohort study | Cohort study | Cross‐sectional study | Cohort study |

| Field of specialization | Orthognathic Surgery and Orthodontics | Prosthodontics | Prosthodontics | Orthodontics | Orthognathic Surgery and Orthodontics |

| Country | Finland | Sweden | Sweden | England | Kuwait |

| University/private setting | University | Three specialist clinics | Three specialist clinics | University and Private practice | Four specialist clinics |

| Study period | 2013–2014 | 1998–1999 | 1998–1999 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Patient age | 15–67 years | mean: 53 years (male)‐54 years (female) | mean: 53 years (male)‐54 years (female) | 40–57 years | mean: 21,1 years |

| Gender distribution | 32% male, 68% female | 51% male, 49% female | 51% male, 49% female | 15% male, 85% female | 29.7% male, 70.3% female |

| Number of patients enrolled | 85 | 61 | 61 | 26 | 74 |

| Specific information | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose of the study | Assessment of patients opinion and satisfaction on a new information clinic and statistic analysis of this new information clinic. | Investigation of the dentist's role in the provider‐patient relationship as to verbal communication and patient satisfaction with the treatment outcome in prosthetic dentistry. | To investigate the patient‐dentist communication dimensions on patient satisfaction. 2 satisfaction concepts were specified: satisfaction with single visit (care) and satisfaction with the overall treatment outcome. | Investigating factors influencing patient satisfaction with the process of orthodontic treatment. | The influence of pre‐treatment information on over all posttreatment satisfaction after orthognatic surgery. |

| Main findings | Patients gave positive feedback for “information clinic” ‐ this system got implemented into clinical routine. The provided information was to help in the decision‐making process to proceed; not proceed with orthognatic treatment in general. | Patient evaluation of the care during an encounter is dependent on the dentist's verbal communication activity during the encounter (short term). This communication has no impact on the satisfaction with the overall prosthetic treatment outcome in the intermediate time perspective. | The study showed the importance of the opportunity for patients to ask and talk about their dental health situation. Dentists generally should listen more and talk less during a treatment intervention. The study shows the feasibility to examine the communication process in dentistry. | In general, patients were satisfied with the process of treatment. Out of several factors (themes), quality of communication has a major impact on patient satisfaction. Making patients feel involved in their own care showed a benefit for satisfaction. Communication skills training for staff should be provided. | Participants were more likely to be satisfied when they were provided with more information about discomfort and surgical risks. |

| Tools used for patient communication/shared decision‐making | Interdisciplinary Information clinic, prior to taking the patient records and prior to treatment begin. Present specialists: orthodontist, oral hygienist, oral and maxillofacial surgeon, psychologist as well as a previous patient. 15–20 min talks with each specialist were undertaken. In addition to verbal and written explanation, a digital &$$$; | Verbal communication was used. Communication was recorded and analyzed and seven dimensions of verbal communication were found. | Verbal communication was used. Communication was recorded and analyzed and seven dimensions of verbal communication were found. | No tools specifically described, verbal communication only | Verbal communication was used. |

| Assessment method | Questionnaire | Two Questionnaires | Two Questionnaires | Semistructured interview | Telephone interview with a structured questionnaire |

| Details of the assessment method | An existing questionnaire was translated, adapted, and expanded to suit the needs of this study. | First questionnaire for assessment of patient satisfaction with care (during treatment). 11 questions total; eight questions based on Dental Visit Satisfaction Scale. Second questionnaire: patient satisfaction with treatment outcome (end of treatment). Questionnaire given at baseline and 3 months after completing treatment. | The “patient satisfaction with treatment outcome” questionnaire was distributed twice during the treatment period: once before treatment begin and once 3 months after completion of treatment. The “patient satisfaction with care” questionnaire analyzed the satisfaction from a short‐term perspective (11 questions derivate from the Dental Visit Satisfaction Scale). | Qualitative interview: large amount of data ware analyzed to generate themes and subthemes regarding patient satisfaction. Communication strategy was one of the four themes extracted. | The questions aimed at exploring if the patients were sufficiently informed about risks, discomforts, functional problems (among others) before and during treatment. Questions about the overall satisfaction with treatment were also included. |

TABLE 2.

Extracted data of included articles 6–10

| Article number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General information | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Title | Adolescents' perception of the quality of orthodontic treatment | Satisfaction with orthodontic treatment | Patient self‐reported satisfaction with maxillary anterior dental implant treatment | Satisfaction with orthodontic treatment outcome | The effect of esthetic consultation methods on acceptance of diastema‐closure treatment plan: a pilot study |

| Authors | Larsson, B. W.; Bergstrom, K. | Keles, F.; Bos, A. | Levi, A.; Psoter, W. J.; Agar, J. R.; Reisine, S. T.; Taylor, T. D. | Feldmann, I. | Almog, D.; Sanchez Marin, C; Proskin, H. M.; Cohen, M. J.; Kyrkanides, S.; Malmstrom, H. |

| Journal | Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences | The Angle Orthodontist | International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants | The Angle Orthodontist | Journal of the American Dental Association |

| Year of publication | 2005 | 2013 | 2003 | 2014 | 2004 |

| References | Scand J Caring Sci. 2005 Jun;19(2):95–101 | Angle Orthod. 2013 May;83(3):507–11 | Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2003 Jan‐Feb; 18(1):113–20 | Angle Orthod. 2014 Jul;84(4):581–7 | J Am Dent Assoc. 2004 Jul;135(7):875–81 |

| Study information | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Cross‐sectional study | Trend study | Observational study | Observational study | Pilot study |

| Field of specialization | Orthodontics | Orthodontics | Prosthodontics | Orthodontics | Restorative dentistry |

| Country | Sweden | Netherlands | USA | Sweden | USA |

| University/private setting | Public dental service ‐ orthodontic clinic | University | University | Public dental service ‐ orthodontic clinic | University |

| Study period | 2001 | 2008–2009 | 2000 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Patient age | mean: 17, 1 years | <30 years | 18–80 years, mean: 56 years | mean: 14.3 years | 18–60 years, mean: 34.9 years |

| Gender distribution | 47% male, 53% female | 34.8% male, 65.2% female | 47.4% male; 52.5% female | male: n = 54; female: n = 56 | 20.8% male, 79.2% female |

| Number of patients enrolled | 151 | 115 | 78 | 110 | 24 |

| Specific information | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose of the study | (1) Description of adolescent's perception of quality of care receiving orthodontic treatment. (2) Assessment of relationship between patient's perception of quality of orthodontic care and their self‐reported experiences of various outcome‐related aspects on the other. | The examination of patients' satisfaction with the received orthodontic treatment. | The assessment of the overall patient satisfaction with the treatment outcome. | The evaluation of the factors associated with treatment outcome satisfaction. | The assessment of preferred communication tools to help the patients best understand and visualize the treatment plan and esthetic changes. |

| Main findings | The implication of the patient in the decision‐making process enhanced the perception of quality of care. The possibility to participate in the SDM process contributed to an overall higher satisfaction rating. More active involvement of patients in the decision‐making process is suggested. | The dentist‐patient relationship was the most important factor contributing to patient satisfaction. | Communication between dentist and patient is important to achieve an optimal esthetic result that will be satisfactory to both parties, since their perceptions of esthetics do not necessarily coincide. | In order to improve orthodontic treatment outcome, a more active involvement of patients in the decision‐making process is suggested. | Digital computer‐imaging simulation is more effective in achieving treatment plan acceptance than the three other methods. |

| Tools used for patient communication/shared decision‐making | No tools specifically described, verbal communication only | No tools specifically described, verbal communication only | No tools specifically described, verbal communication only | No tools specifically described, verbal communication only | (1) Before/after photos of other patients; (2) Wax‐up on model of patient; (3) Intraoral mock‐up; (4) Digital computer‐imaging simulation. Every patient received every tool. |

| Assessment method | Quality from the Patient's perspective Questionnaire (QPP) | Questionnaire | Self‐administered questionnaire | Two Questionnaires | Two Questionnaires |

| Details of the assessment method | The QPP questionnaire was modified and adapted to fit this study. The quality of care as well as the outcome‐related aspects were included in this questionnaire. | 58 items questionnaires with 11 items on satisfaction with doctor‐patient relationship. Questions about patient satisfaction and patient perspective on treatment outcome. | The 24 items, self‐administered, structured questionnaire was developed specifically for this project. Questions include satisfaction with information prior to treatment and satisfaction with the dentist. | First questionnaire prior to treatment: 11 items concerning treatment motivations and expectations. Second questionnaire: after active treatment at first visit in retention phase. Questions about satisfaction with treatment outcome, general quality of care, perceived pain, and discomfort during active treatment. | First questionnaire: given to patient directly after each consultation method with questions to determine the subject's perceptions regarding treatment plan acceptance. Second questionnaire: to compare the four methods and to determine the preferred method. |

8. RESULTS

The search of Medline, Embase, Cochrane, and Web of Science provided 6703 titles, yielding a total of 6678 titles upon duplicates removal. Of these, 6625 studies were excluded after reviewing the titles and abstracts, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The full texts of the remaining 53 studies were examined in detail. Forty‐three studies did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Table 3 for the reasons for exclusion). Finally, 10 studies were included in this scoping review (Figure 3). All information retrieved from the included studies is given in Table 1 and Table 2.

TABLE 3.

List of excluded articles with reasons for exclusion

| Title | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Barber, S.; Pavitt, S.; Meads, D.; Khambay, B.; Bekker, H.Can the current hypodontia care pathway promote shared decision‐making?Journal of Orthodontics Jun 2019;46 (2): 126–1362019 Jun | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| de Souza, R. A.; de Oliveira, A. F.; Pinheiro, S. M.; Cardoso, J. P.; Magnani, M. B.Expectations of orthodontic treatment in adults: the conduct in orthodontist/patient relationshipDental Press J Orthod Mar‐Apr 2013;18(2):88–942013 Mar‐Ap | Not addressing SDM or satisfaction with information prior to treatment |

| Dunbar, A. C.; Bearn, D.; McIntyre, G.The Influence of Using Digital Diagnostic Information on Orthodontic Treatment Planning ‐ A Pilot StudyJournal of Healthcare Engineering Dec 2014;5(4):411–4272014 Dec | No link to SDM and patient information prior to treatment |

| Knobel, A.; Haßfeld, S.Preoperative information. Development of a multimedia‐based system on CD‐ROM to give preoperative information to patients acceptance of the systemMund‐, Kiefer‐ und Gesichtschirurgie 2005;9(2):109–1152005 | No information on treatment outcome |

| Ben Gassem, A.; Foxton, R.; Bister, D.; Newton, J. T.Patients' Acceptability of Computer‐Based Information on Hypodontia: a Randomized Controlled TrialJDR clinical and translational research 2018;3(3):246–2552018 | No information on treatment outcome |

| Bradley, E.; Shelton, A.; Hodge, T.; Morris, D.; Bekker, H.; Fletcher, S.; Barber, S.Patient‐reported experience and outcomes from orthodontic treatmentJournal of Orthodontics 2020;():14653125209043772020 | Not about patient satisfaction with communication/information given |

| Carr, K. M.; Fields, H. W.; Beck, F. M.; Kang, E. Y.; Kiyak, H. A.; Pawlak, C. E.; Firestoneg, A. R.Impact of verbal explanation and modified consent materials on orthodontic informed consentAmerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Feb 2012;141(2):174–1862012 Feb | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Barkhordar, A.; Pollard, D.; Hobkirk, J. A.A comparison of written and multimedia material for informing patients about dental implantsDent Update Mar 2000;27(2):80–42000 Mar | Poster, no article |

| Othman, S.; Lyons, T.; Cohn, J. E.; Shokri, T.; Bloom, J. D.The Influence of Photo Editing Applications on Patients Seeking Facial Plastic Surgery ServicesEsthetic Surgery Journal 2020;():2020 | Not in dentistry |

| Patel, J. H.; Moles, D. R.; Cunningham, S. J.Factors affecting information retention in orthodontic patientsAmerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Apr 2008;133(4):S61‐S672008 Apr | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Patel, A. M.; Richards, P. S.; Wang, H. L.; Inglehart, M. R.Surgical or non‐surgical periodontal treatment: Factors affecting patient decision makingJournal of Periodontology 2006;77(4):678–6832006 | Not in esthetic dentistry |

| Reissmann, D. R.; Bellows, J. C.; Kasper, J.Patient Preferred and Perceived Control in Dental Care Decision MakingJdr Clinical & Translational Research Apr 2019;4(2):151–1592019 Apr | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Parker, K.; Cunningham, S. J.; Petrie, A.; Ryan, F. S.Randomized controlled trial of a patient decision‐making aid for orthodonticsAmerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Aug 2017;152(2):154–1602017 Aug | No treatment conducted |

| Miller, J. R.; Larson, B. E.; Satin, D.; Schuster, L.Information‐seeking and decision‐making preferences among adult orthodontic patients: an elective health care modelCommunity Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology Feb 2011;39(1):79–862011 Feb | Not adressing patient satisfaction with communication/information given |

| Anderson, M. A.; Freer, T. J.An orthodontic information package designed to increase patient awarenessAustralian Orthodontic Journal 2005;21(1):11–182005 | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Barber, S.Shared decision‐making in orthodontics: Are we there yet?J Orthod Jun 2019;46(1_suppl):21–252019 Jun | Not a clinical study |

| Thomson, A. M.; Cunningham, S. J.; Hunt, N. P.A comparison of information retention at an initial orthodontic consultationEuropean Journal of Orthodontics Apr 2001;23(2):169–1782001 Apr | Not addressing patient satisfaction with communication/information given |

| Rivas Ruiz, F.Variability in Therapeutic Decision Making: Evaluation of the Validity of an Information and Communication Technology ToolActas Dermo‐Sifiliograficas 2017;108(7):6072017 | Not a clinical study |

| Sousa Dias, N.; Tsingene, F.SAEF ‐ Smile's Esthetic Evaluation form: a useful tool to improve communications between clinicians and patients during multidisciplinary treatmentThe European journal of esthetic dentistry: official journal of the European Academy of Esthetic Dentistry 2011;6(2):160–1762011 | Not a clinical study |

| Srai, J. P. K.; Petrie, A.; Ryan, F. S.; Cunningham, S. J.Assessment of the effect of combined multimedia and verbal information vs verbal information alone on anxiety levels before bond‐up in adolescent orthodontic patients: A single‐center randomized controlled trialAmerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Oct 2013;144(4):505–5112013 Oct | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Rozier, R. G.; Horowitz, A. M.; Podschun, G.Dentist‐patient communication techniques used in the United States: The results of a national surveyJournal of the American Dental Association 2011;142(5):518–5302011 | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Al‐Silwadi, F. M.; Gill, D. S.; Petrie, A.; Cunningham, S. J.Effect of social media in improving knowledge among patients having fixed appliance orthodontic treatment: A single‐center randomized controlled trialAmerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Aug 2015;148(2):231–2372015 Aug | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Alagesan, A.; Vaswani, V.; Vaswani, R.; Kulkarni, U.Knowledge and awareness of informed consent among orthodontists and patients: A pilot studyContemp Clin Dent Sep 2015;6(Suppl 1):S242‐72015 Sep | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Ahn, J. H. B.; Power, S.; Thickett, E.; Andiappan, M.; Newton, T.Information retention of orthodontic patients and parents: A randomized controlled trialAmerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Aug 2019;156(2):169 − +2019 Aug | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Kupke, J.; Wicht, M. J.; Stutzer, H.; Derman, S. H. M.; Lichtenstein, N. V.; Noack, M. J.Does the use of a visualized decision board by undergraduate students during shared decision‐making enhance patients' knowledge and satisfaction? ‐ A randomized controlled trialEuropean Journal of Dental Education Feb 2013;17(1):19–252013 Feb | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Levine, T. P.The effects of a humorous video on memory for orthodontic treatment consent informationAmerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Feb 2020;157(2):240–2442020 Feb | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Chi, J. J.Reflections on Shared Decision MakingOtolaryngology‐Head and Neck Surgery Nov 2018;159(5):809–8102018 Nov | Not in dentistry |

| Gebhard‐Achilles, W.PEP: patient‐supported esthetic protocolEur J Esthet Dent Winter 2013;8(4):492–5052013 Winter | Not a clinical study |

| Ersoz, M.; Uz, Z.; Malkoc, S.; Karatas, M.A Patient‐ and Family‐Centered Care Approach to Orthodontics: Assessment of Feedbacks from Orthodontic Patients and Their FamiliesTurkish Journal of Orthodontics Jun 2016;29(2):38–432016 Jun | No assessment of communication |

| Chen, J. H.; Huang, H. L.; Lin, Y. C.; Chou, T. M.; Ebinger, J.; Lee, H. E.Dentist‐Patient Communication and Denture Quality Associated with Complete Denture Satisfaction Among Taiwanese Elderly WearersInt J Prosthodont Sep‐Oct 2015;28(5):531–72015 Sep‐Oct | Not in esthetic dentistry |

| Kafantaris, S. N.; Tortopidis, D.; Pissiotis, A. L.; Kafantaris, N. M.Factors Affecting Decision‐Making For Congenitally Missing Permanent Maxillary Lateral Incisors: A Retrospective StudyThe European journal of prosthodontics and restorative dentistry 2020;28(1):43–522020 | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Bassi, F.; Carr, A. B.; Chang, T. L.; Estafanous, E.; Garrett, N. R.; Happonen, R. P.; Koka, S.; Laine, J.; Osswald, M.; Reintsema, H.; Rieger, J.; Roumanas, E.; Estafanous, E.; Salinas, T. J.; Stanford, C. M.; Wolfaardt, J.Oral Rehabilitation Outcomes Network‐ORONetThe International journal of prosthodontics 2013;26(4):319–3222013 | Not a clinical study |

| Shahrani, I.; Tikare, S.; Togoo, R. A.; Qahtani, F.; Assiri, K.; Meshari, A.Patient's satisfaction with orthodontic treatment at King Khalid University, College Of Dentistry, Saudi ArabiaBangladesh Journal of Medical Science Apr 2015;14(2):146–1502015 Apr | Not in esthetic dentistry |

| Delivery of information to orthodontic patients using social mediaEvidence‐based dentistry 2017;18(2):59–602017 | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Wright, N. S.; Fleming, P. S.; Sharma, P. K.; Battagel, J.Influence of Supplemental Written Information on Adolescent Anxiety, Motivation and Compliance in Early Orthodontic TreatmentAngle Orthodontist Mar 2010;80(2):329–3352010 Mar | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Marshman, Z.; Eddaiki, A.; Bekker, H. L.; Benson, P. E.Development and evaluation of a patient decision aid for young people and parents considering fixed orthodontic appliancesJournal of Orthodontics 2016;43(4):276–2872016 | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Yu, M. S.; Jang, Y. J.Preoperative computer simulation for asian rhinoplasty patients: Analysis of accuracy and patient preferenceEsthetic Surgery Journal 2014;34(8):1162–11712014 | Not in dentistry |

| Abualfaraj, R. J.; McDonald, F.; Daly, B.; Scambler, S.Patients with cleft: Experiences, understanding and information provision during treatmentOrthodontics & Craniofacial Research Nov 2019;22(4):289–2952019 Nov | Not in dentistry |

| Guest, W; Forbes, D; Schlosser, C; Yip, S; Coope, R; Chew, J.aspects of elective surgery patients' decision‐making experiencesNursing Ethics Sep 2013;20(6):672–683 + B502013 Sep | Not a clinical study |

| Lin, M. L.; Huang, C. T.; Chiang, H. H.; Chen, C. H.Exploring ethical aspects of elective surgery patients' decision‐making experiencesNursing Ethics Sep 2013;20(6):672–6832013 Sep | Not addressing patient satisfaction with treatment outcome |

| Kufta, K.; Peacock, Z. S.; Chuang, S. K.; Inverso, G.; Levin, L. M.Components of Patient Satisfaction After Orthognathic SurgeryJ Craniofac Surg Jan 2016;27(1):e102‐52016 Jan | Not in esthetic dentistry |

| Herrero Antón De Vez, H.; Herrero Jover, J.; Comas, R.Personalized medicine: Technological bridge between patient and surgeon by 3D printed surgical guide in rhinoplastyInternational Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery 2018;13():S228‐S2302018 | Not in dentistry |

| Chikaher, A.; Stagnell, S.; Morton, A.; Sherry, M.The role of 3D printing in a district general hospital oral and maxillofacial departmentBritish Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2016;54(10):e712016 | Poster, no article |

All 10 studies were published between 2002 and 2018 and focused either on orthodontics (n = 6), 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 prosthodontics (n = 3) 26 , 27 , 28 or restorative dental treatment (n = 1). 29 Two of the six orthodontic studies included orthognathic surgery. 20 , 25 Most studies were of Scandinavian origin. 20 , 22 , 24 , 26 , 27 Six studies were conducted in a university setting, 20 , 21 , 23 , 25 , 28 , 29 two in the public dental health sector, 22 , 24 while two studies were conducted in a private clinic setting. 26 , 27 The number of patients enrolled varied between a minimum of n = 24 patients 29 and a maximum of n = 151 patients. 22 Patients of all age groups were included (for details, see Table 1 and Table 2).

The aims of the included studies were to investigate patient satisfaction with treatment outcomes, patient satisfaction with patient‐dentist communication and preferred communication tools, and the evaluation/investigation of factors influencing patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction was evaluated in one study with a SSQ, 21 while the other nine studies used a structured questionnaire (quantitative method). The following communication strategies/tools were applied: verbal (n = 4), 21 , 25 , 26 , 27 verbal and visual (n = 2). 20 , 29 Four studies did not mention additional tools for communication, and followed the conventional, verbal approach. 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28

The tools applied in the two studies that used verbal and visual communication methods were: (a) A PowerPoint presentation for patient information before orthognathic/orthodontic treatment 20 ; (b) A comparative analysis of four visual tools: (1) Before and after photos of other patients; (2) Wax‐up on the model of the patient; (3) Intraoral Mock‐up; (4) Digital computer‐imaging simulation. Every patient received four information sessions, each with a different tool. To determine patients' perceptions regarding treatment plan acceptance, they were given a questionnaire after each information session. Subsequently, patients were asked to compare the four communication tool methods and to determine their preferred method. The computer‐imaging was significantly more effective in achieving treatment plan acceptance than the other three methods and was best ranked by patients. Additionally, patients liked taking home photos to share with their families.

All studies found that patient communication utilizing specific communication tools (verbal, visual, and advice) positively impacted either patient satisfaction, patient‐dentist relationship, information retention, treatment acceptance, quality of care or treatment outcome (Table 1 and Table 2).

9. DISCUSSION

The present scoping review identified studies that investigated communication tools for patients and their impact on patient satisfaction in the field of esthetics in dentistry. During the review process, a considerable amount of case reports presenting different available tools were found.

Even though case reports and studies with less than 10 participants were excluded to elevate the evidence level, 10 clinical observational studies met the inclusion criteria. This indicates the general lack of high‐quality evidence in this field of research, which is remarkable, considering the rapid development of digital tools in dentistry during recent years. 30 , 31 , 32 , 33

Today, approximately 15 smile design software are available for dental professionals. 30 In particular, AR has gained access to healthcare and gradually plays a role in dentistry, too. 11 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 AR technology is used for medical and dental purposes with the aim, among others, to simulate specific treatment goals. 11 , 38

Most studies included in this review were published by Scandinavian research groups, such as Sweden and Finland. One potential explanation for the leading role of these countries in respect to patient involvement in healthcare may be the Nordic leadership style, which comes along with a flat hierarchical structure in Scandinavian countries, and might promote a less paternalistic patient‐dentist relation. 39 Additionally, the Nordic health care system aims to increase patients' involvement in treatment planning and decision‐making. 40 The primary aim of several health care reforms in the Nordic countries during the last years was to improve responsiveness to patients. 40 In this sense, all Nordic countries have taken measures to strengthen the role of patients. 40

Another key finding of the present review is that most of the included studies were published in the field of orthodontics, 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 followed by prosthodontics. 26 , 27 , 28 As orthodontic and orthognathic treatments often result in substantial changes of dental and facial esthetics, it is comprehensible that research on improvement of patient communication, patient involvement, and SDM has its focus in this dental field. 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 Nevertheless, with an increasing interest in improving facial esthetics not only in respect to tooth position but also in color and shape, the importance of patient communication and SDM is rapidly increasing in other disciplines, including prosthodontics. 5

In general, in the health sector, a trend to use new, digital tools for patient information, patient‐doctor communication, and treatment planning can be observed. 45 , 46 Core specialization fields are esthetic and reconstructive surgery, as well as cancer therapy. In cancer therapy, patient involvement by SDM is very well established, and rapidly increasing with the use of new patient‐doctor communication technologies. 47 , 48

Whereas, in dental medicine, the implementation of communication tools in esthetics remains limited chiefly to conventional verbal communication. However, two studies used additional tools for patient‐dentist communication and patient involvement in the decision‐making process. 20 , 29 Only one clinical study compared different tools, 29 which demonstrates the lack of clinical evidence regarding the use of modern communication tools for patient involvement. This stands in contrast to developments mentioned above in the field of SDM and digital technologies, especially considering AR to gain importance in improving communication and supporting decision aids for patients. 11 , 35 , 38

Regarding the evaluation of patient satisfaction with communication and treatment outcome, a large variety of evaluation methods was found to be applied. Multiple different questionnaires were used by the different research groups, making the comparison among studies difficult. One research group used a SSQ, 21 while all other groups used structured questionnaires. SSQs are effective when the study's purpose is to collect qualitative information and to explore patients' thoughts, feelings and beliefs. 18 , 19 Within the structured questionnaires, a great variance of scales and questions (VAS scale, Lickert scale, and others) were applied. Not all of them were validated before usage.

Therefore, it seems essential to further develop standardized communication tools for SDM in dental medicine, which will allow the comparison of research on this topic. Additionally, these tools and methods should underly a scientific validation. Secondly, there is a need for standardized questionnaires to assess the impact of communication tools on patient satisfaction. The variety of questionnaires may be reduced to less, significant questionnaires, facilitating comparability among studies. Ultimately, more clinical evidence through controlled clinical trials is needed to prove the additional benefit of communication tools in dentistry for the involvement of patients in the decision‐making process.

The results of this study must be carefully interpreted. One limitation is that the 10 included studies are heterogeneous in terms of sample size and rigor in the description of the methodology. Despite a rigorous and transparent methodology, some potentially includable studies may have been missed. Furthermore, some studies were possibly not included because of the authors' choice of key‐words and terms.

10. CONCLUSIONS

This scoping review shows the importance of patient involvement in the decision‐making process for improved patient satisfaction with esthetic dental treatments. Additional communication tools besides conventional verbal communication enhances patient satisfaction with the treatment outcome, improve quality of care and establish a better patient‐dentist relationship. With an increased implementation of digital tools in esthetic dentistry, patient communication and SDM may further improve in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DISCLOSURE

The authors are grateful to Mafalda Vieira Burri for her valuable advice in the identification of the databases and the development of the search strategy. The authors would like to thank PD PhD Dobrila Nesic for reviewing the manuscript. The authors do not have any financial interest in the companies whose materials are included in this article. Open access funding provided by Universite de Geneve.

Touati R, Sailer I, Marchand L, Ducret M, Strasding M. Communication tools and patient satisfaction: A scoping review. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2022;34(1):104‐116. doi: 10.1111/jerd.12854

[Correction added on 5th Jan, after first online publication: Projekt Deal funding statement has been added.]

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kahng LS. Patient‐dentist‐technician communication within the dental team: using a colored treatment plan wax‐up. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2006;18:185‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sancho‐Puchades M, Fehmer V, Hammerle C, Sailer I. Advanced smile diagnostics using CAD/CAM mock‐ups. Int J Esthet Dent. 2015;10:374‐391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Owens EG, Goodacre CJ, Loh PL, et al. A multicenter interracial study of facial appearance. Part 1: a comparison of extraoral parameters. Int J Prosthodont. 2002;15:273‐282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Woolf SH, Chan EC, Harris R, et al. Promoting informed choice: transforming health care to dispense knowledge for decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:293‐300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benecke M, Kasper J, Heesen C, Schaffler N, Reissmann DR. Patient autonomy in dentistry: demonstrating the role for shared decision making. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20:318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. Four models of the physician‐patient relationship. JAMA. 1992;267:2221‐2226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision‐making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681‐692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crawford MJ, Rutter D, Manley C, et al. Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. Brit Med J. 2002;325:1263‐1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edwards M, Davies M, Edwards A. What are the external influences on information exchange and shared decision‐making in healthcare consultations: a meta‐synthesis of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:37‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361‐1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marchand L, Touati R, Fehmer V, Ducret M, Sailer I. Latest advances in augmented reality technology and its integration into the digital workflow. Int J Comput Dent. 2020;23:397‐408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reshad M, Cascione D, Magne P. Diagnostic mock‐ups as an objective tool for predictable outcomes with porcelain laminate veneers in esthetically demanding patients: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 2008;99:333‐339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson BR, Schwartz A, Goldberg J, Koerber A. A chairside aid for shared decision making in dentistry: a randomized controlled trial. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:133‐141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park SG, Lee S, Kim MK, Kim HG. Shared decision support system on dental restoration. Expert Systems with Applications. 2012;39:11775‐11781. 10.1016/j.eswa.2012.04.074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sepucha KR, Fowler FJ Jr, Mulley AG Jr. Policy support for patient‐centered care: the need for measurable improvements in decision quality. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23(Suppl 2):54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rohlin M, Mileman PA. Decision analysis in dentistry–the last 30 years. J Dent. 2000;28:453‐468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kallio H, Pietila AM, Johnson M, Kangasniemi M. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi‐structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:2954‐2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. DeJonckheere M, Vaughn LM. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Fam Med Community Health. 2019;7:e000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bergkulla N, Hanninen H, Alanko O, et al. Introduction and assessment of orthognathic information clinic. Eur J Orthod. 2017;39:660‐664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wong L, Ryan FS, Christensen LR, Cunningham SJ. Factors influencing satisfaction with the process of orthodontic treatment in adult patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;153:362‐370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Larsson BW, Bergstrom K. Adolescents' perception of the quality of orthodontic treatment. Scand J Caring Sci. 2005;19:95‐101. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Keles F, Bos A. Satisfaction with orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2013;83:507‐511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feldmann I. Satisfaction with orthodontic treatment outcome. Angle Orthod. 2014;84:581‐587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. AlKharafi L, AlHajery D, Andersson L. Orthognathic surgery: pretreatment information and patient satisfaction. Med Princ Pract. 2014;23:218‐224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sondell K, Palmqvist S, Soderfeldt B. The dentist's communicative role in prosthodontic treatment. Int J Prosthodont. 2004;17:666‐671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sondell K, Soderfeldt B, Palmqvist S. Dentist‐patient communication and patient satisfaction in prosthetic dentistry. Int J Prosthodont. 2002;15:28‐37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levi A, Psoter WJ, Agar JR, Reisine ST, Taylor TD. Patient self‐reported satisfaction with maxillary anterior dental implant treatment. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2003;18:113‐120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Almog D, Sanchez Marin C, Proskin HM, Cohen MJ, Kyrkanides S, Malmstrom H. The effect of esthetic consultation methods on acceptance of diastema‐closure treatment plan: a pilot study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:875‐881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen YW, Stanley K, Att W. Artificial intelligence in dentistry: current applications and future perspectives. Quintessence Int. 2020;51:248‐257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Besimo CE, Zitzmann NU, Joda T. Digital Oral medicine for the elderly. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2171. 10.3390/ijerph17072171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Spagnuolo G, Sorrentino R. The role of digital devices in dentistry: clinical trends and scientific evidences. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020;9(6):1692. 10.3390/jcm9061692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vandenberghe B. The digital patient ‐ imaging science in dentistry. J Dent. 2018;74(1):S21‐S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Farronato M, Maspero C, Lanteri V, et al. Current state of the art in the use of augmented reality in dentistry: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kwon HB, Park YS, Han JS. Augmented reality in dentistry: A current perspective. Acta Odontol Scand. 2018;76:497‐503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ferrari V, Klinker G, Cutolo F. Augmented reality in healthcare. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:9321535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ayoub A, Pulijala Y. The application of virtual reality and augmented reality in Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Touati R, Richert R, Millet C, Farges JC, Sailer I, Ducret M. Comparison of two innovative strategies using augmented reality for communication in aesthetic dentistry: a pilot study. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:7019046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Andreasson U, Lundqvist M. Nordic Leadership. Nordic Council of Ministers; 2018:2018. 10.6027/ANP2018-835 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Magnussen JVK, Saltman RB. In: VK MJ, Saltman RB, eds. Nordic Health Care Systems: Recent Reforms and Current Policy Challenges (Review). 1st ed. Open University Press; 2009. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/98417/E93429.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thanathornwong B. Bayesian‐based decision support system for assessing the needs for orthodontic treatment. Healthc Inform Res. 2018;24:22‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jung SK, Kim TW. New approach for the diagnosis of extractions with neural network machine learning. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016;149:127‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xia J, Ip HH, Samman N, et al. Computer‐assisted three‐dimensional surgical planning and simulation: 3D virtual osteotomy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;29:11‐17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Anton de Vez H H, Herrero Jover J. Personalized Medicine: Technological Bridge between Patient and Surgeon by 3D Printed Surgical Guide in Rhinoplasty. Journal of Aesthetic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2018;04(01):1–3. 10.4172/2472-1905.100038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nanah A, Bayoumi AB. The pros and cons of digital health communication tools in neurosurgery: a systematic review of literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2020;43:835‐846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Uppot RN, Laguna B, McCarthy CJ, et al. Implementing virtual and augmented reality tools for radiology education and training, communication, and clinical care. Radiology. 2019;291:570‐580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sferra SR, Cheng JS, Boynton Z, DiSesa V, Kaiser LR, Ma GX, Erkmen CP. Aiding shared decision making in lung cancer screening: two decision tools. Journal of Public Health. 2021;43(3):673‐680. 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Spronk I, Burgers JS, Schellevis FG, van Vliet LM, Korevaar JC. The availability and effectiveness of tools supporting shared decision making in metastatic breast cancer care: a review. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.