Abstract

Objective

To determine the role of gasdermin E (GSDME)–mediated pyroptosis in the pathogenesis and progression of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and to explore the potential of GSDME as a therapeutic target in RA.

Methods

The expression and activation of caspase 3 and GSDME in the synovium, macrophages, and monocytes of RA patients were determined by immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and Western blot analysis. The correlation of activated GSDME with RA disease activity was evaluated. The pyroptotic ability of monocytes from RA patients was tested, and the effect of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) on caspase 3/GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis of monocytes and macrophages was investigated. In addition, collagen‐induced arthritis (CIA) was induced in mice lacking Gsdme, and the incidence and severity of arthritis were assessed.

Results

Compared to cells from healthy controls, monocytes and synovial macrophages from RA patients showed increased expression of activated caspase 3, GSDME, and the N‐terminal fragment of GSDME (GSDME‐N). The expression of GSDME‐N in monocytes from RA patients correlated positively with disease activity. Monocytes from RA patients with higher GSDME levels were more susceptible to pyroptosis. Furthermore, TNF induced pyroptosis in monocytes and macrophages by activating the caspase 3/GSDME pathway. The use of a caspase 3 inhibitor and silencing of GSDME significantly blocked TNF‐induced pyroptosis. Gsdme deficiency effectively alleviated arthritis in a mouse model of CIA.

Conclusion

These results support the notion of a pathogenic role of GSDME in RA and provide an alternative mechanism for RA pathogenesis involving TNF, which activates GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis of monocytes and macrophages in RA. In addition, targeting GSDME might be a potential therapeutic approach for RA.

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by persistent synovitis, systemic inflammation, cartilage loss, and bone erosion, eventually resulting in disability and decreased quality of life (1). A prominent feature of RA is persistent inflammation (2). Identification of specific molecules and their roles in inflammation is important for understanding the pathogenesis of RA and for developing novel therapies.

Pyroptosis is a gasdermin‐mediated proinflammatory form of programmed cell death, characterized by cell swelling, large bubble blowing from the membrane, and eventual cell rupture, followed by the release of inflammatory cytokines and danger signals (3). After cleavage of full‐length gasdermin proteins, their N‐terminal fragments are released, which oligomerize and insert into the cell membrane, forming pores (4, 5). The best understood member of the gasdermin family, gasdermin D (GSDMD), can be cleaved by caspases 1, 4/5, 8, and 11, resulting in the induction of pyroptosis and release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β) and IL‐18 (6, 7, 8, 9, 10).

Similar to GSDMD, GSDME is specifically cleaved by caspase 3, which results in the production of pore‐forming N‐terminal fragments of GSDME (GSDME‐N) (11). Caspase 3 generally induces apoptosis in GSDME‐negative cells and initiates pyroptosis in cells with high levels of GSDME, converting the noninflammatory apoptosis‐inducing machinery to proinflammatory pyroptosis programming in these cells (12, 13, 14, 15). Currently, our understanding of the role of GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis is limited to chemotherapy‐induced cell death and cancer therapy (11, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20). Owing to the highly proinflammatory character of pyroptotic cells, we speculated that GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis plays a critical role in triggering immunity and in driving the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. However, whether GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis contributes to the pathogenesis and progression of autoimmune diseases, including RA, remains unknown.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is abundant in the circulation as well as in the synovial fluid and tissues of RA patients (21). It plays a key role in sustained synovial inflammation by enhancing the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL‐6, and by inducing NF‐κB activation and metalloproteinase production (22). Moreover, TNF inhibits bone formation and accelerates bone absorption (23). Excessive production of TNF is associated with the development of RA (24). TNF inhibitors, including monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins, are the most commonly recommended clinical treatments for RA (25, 26). TNF is a strong inducer of apoptosis, owing to its ability to activate caspase 3 (27, 28). Activated caspase 3 reportedly cleaves and activates GSDME, which results in pyroptosis in GSDME‐expressing cells. In this context, an important question related to RA pathogenesis arises as to whether the abundance of TNF in patients with RA induces pyroptosis in GSDME‐expressing cells by activating the caspase 3/GSDME pathway, and thereby, promotes systemic and joint inflammation.

To answer this question, we first tested the expression and activation of caspase 3/GSDME in synovial macrophages and circulating monocytes from RA patients. Second, we investigated whether TNF induced GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis in monocyte/macrophages. Finally, we used Gsdme −/− mice in a collagen‐induced arthritis (CIA) model to further assess the role of GSDME in the pathogenesis of RA. We found that in RA patients, TNF induces the activation of caspase 3/GSDME and initiates pyroptosis in monocytes and macrophages. We also identified a critical role of GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis in the pathogenesis and progression of RA.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and healthy controls

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University (approval number 201608003). Fifty‐eight RA patients who met the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1987 revised classification criteria for RA (29) or the ACR/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology 2010 classification criteria (30) were recruited from the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology at The Third Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University between January 2018 and April 2021. All participants provided written informed consent. The clinical characteristics of the RA patients are listed in Supplementary Table 1, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963.

Human synovial tissue samples were obtained from patients with osteoarthritis (OA; n = 7) or RA (n = 7) who had undergone knee replacement surgery. Tissue samples with suspected articular infections were excluded. For in vitro experiments, monocytes were purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy controls (n = 17) and RA patients (n = 58). Patients with RA complicated by severe infection, malignancy, or neurologic disease, and those with other autoimmune diseases, such as myositis, scleroderma, or systemic lupus erythematosus, were excluded. Patients with active RA received combination therapy that included TNF inhibitors. Healthy volunteers and OA patients were recruited as controls.

Cells and reagents

A THP‐1 monocyte cell line was purchased from ATCC. In some experiments, macrophages were pretreated with 50 μM Z‐DEVD‐FMK (a caspase 3 inhibitor) (catalog no. HY‐12466; MedChemExpress) and then incubated with a specific medium for further investigation, as indicated below. Cycloheximide (CHX; catalog no. 66‐81‐9) was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich. All in vitro experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

In vitro isolation of peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes

PBMCs were obtained from fresh whole blood from healthy controls and RA patients and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Peripheral blood monocytes were isolated from PBMCs using an EasySep human monocyte isolation kit (catalog no. 19359; StemCell Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified monocytes were harvested and labeled with PerCP–Cy5.5–conjugated anti‐CD14 antibody (BD Biosciences) for flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure 1A, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963). Purified monocytes from healthy controls and RA patients were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; complete 1640 medium) for 4 hours, and then examined by flow cytometric, immunofluorescence, and Western blot analysis. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was also measured. In addition, purified monocytes from 8 untreated RA patients and from 7 RA patients after effective treatment were cultured in complete 1640 medium for 4 hours. Finally, Western blot analysis was performed to determine the expression of GSDME‐N.

Differentiation of THP‐1 cells and bone marrow–derived cells into macrophages

THP‐1 monocytes were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Life Technologies) at 37°C under 5% CO2. For generation of macrophages, THP‐1 cells were incubated with 100 ng/ml phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA; Sigma) for 48 hours, which fully induced monocytes to differentiate into adherent macrophages (31) (Supplementary Figure 1B). THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages were cultured in complete 1640 medium. The purity of differentiated macrophages was measured by flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure 1C).

Bone marrow cells from the femurs and tibias of C57BL/6 wild‐type mice or Gsdme −/− mice were induced to differentiate into macrophages. Bone marrow cells were collected in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco) with 10% FBS (complete DMEM) and incubated with 10 ng/ml macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (catalog no. 315‐02; PeproTech) for 6–7 days to generate bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMMs) (32). Thereafter, murine BMMs were seeded in 24‐well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well in 0.5 ml fresh complete DMEM or in 6‐well plates at 1.5 × 106 cells/well in 2 ml fresh complete DMEM overnight. For assessment of purity, murine BMMs were labeled with Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated anti‐CD11b antibody (BD Biosciences) and phycoerythrin‐conjugated anti‐F4/80 antibody (BioLegend), and analyzed by flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure 1D).

TNF stimulation of RA monocytes, THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages, and murine BMMs

Purified monocytes from each RA patient were divided into 2 parts, seeded in 24‐well or 6‐well culture plates, and cultured in the presence or absence of human TNF (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Immunofluorescence and Western blot analyses were performed to measure cell death and expression of the indicated proteins. THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages were seeded in 24‐well or 6‐well plates and incubated with different concentrations of human TNF (catalog no. 300‐01A; PeproTech) for 36 hours. After complete adherence to the walls of the plates, murine BMMs were cultured with different concentrations of murine TNF (catalog no. 315‐01A; PeproTech) for 36 hours.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)–mediated knockdown of GSDME in THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages

For siRNA‐mediated knockdown of GSDME, 100 pmoles of 2 specific siRNAs (5′‐GCGGTCCTATTTGATGATGAA‐3′ and 5′‐GATGATGGAGTATCTGATCTT‐3′; synthesized by GenePharma) targeting GSDME and 1 negative control siRNA (purchased from GenePharma) were used. The siRNAs were transfected into macrophages using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen). The efficacy of transfection was detected by Western blot analysis and real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Histologic, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence analyses

Human synovial tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and serial paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Mouse bones were decalcified in 0.5M EDTA (pH 7.4) on a shaker for 3 weeks and embedded in paraffin. After deparaffinization and rehydration, serial sections were treated with 200 μg/ml proteinase K (Sigma) for 30 minutes at 37°C or were soaked in citrate buffer (10 mM citric acid, pH 6.0) for 16–18 hours at 60°C to unmask the antigen. For immunohistochemical analysis, sections were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes, and then blocked with 1% sheep serum at room temperature for 1 hour. Serial sections were incubated with anti‐CD68 (catalog no. 14‐0688‐82; ThermoFisher), anti‐GSDME (catalog no. ab215191; Abcam, and catalog no. PA5‐103976; ThermoFisher), anti‐cleaved caspase 3 (catalog no. 9661; Cell Signaling Technology), antivimentin (catalog no. sc‐373717; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti‐TNF (catalog no. A11534; ABclonal Technology), anti–IL‐1β (catalog no. 12242; Cell Signaling Technology), anti‐CD14 (catalog no. 60253‐1‐lg; Proteintech, and catalog no. ab181470; Abcam), and anti‐F4/80 (catalog no. ab16911; Abcam, and catalog no. sc‐377009; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies overnight at 4°C.

For staining with secondary antibodies, species‐matched Alexa Fluor 594–labeled, Alexa Fluor 488–labeled, or horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–labeled antibodies were used (1:400 in 1% bovine serum albumin [BSA] for 1 hour at 37°C). 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine was used as a chromogen, and hematoxylin was used as a counterstain in immunohistochemistry. For immunofluorescence staining, DAPI (Thermo) was used to label nuclei.

For immunofluorescence staining, cells were plated on 24‐well culture plates with coverslips. After treatment, the medium was aspirated and cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes, and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X‐100 for 10–20 minutes at room temperature to expose intracellular antigen. Cells were washed with PBS, blocked with 1% BSA for 1 hour, and incubated with primary antibodies, and then treated as described above.

Cell death assays

Flow cytometry

Purified monocytes or macrophages were cultured under different conditions. The cells were harvested, washed twice with cold PBS, and stained using an Annexin V–FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD PharMingen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were then analyzed using a BD FACSAria III flow cytometer. Data were acquired and processed using FlowJo software. Each experiment was repeated 3 times. Generally, the Annexin V/PI kit is used to detect phosphatidylserine exposed on the external leaflet of the plasma membrane in apoptotic cells. It can also label pyroptotic cells due to membrane rupture, which allows for the recognition of phosphatidylserine on the inner leaflet. Propidium iodide (PI) was used to detect dying cells, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

LDH‐based cytotoxicity assay

In vitro, cell death was also detected by an LDH release assay using a CytoTox 96 Non‐Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay kit (catalog no. G1780; Promega), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Microscopy and PI staining

To morphologically distinguish pyroptotic and apoptotic cells, cells were seeded in 24‐well plates, cultured to 40–60% confluency, and then treated as indicated in the figure legends. Lytic cell death was visualized and measured by PI incorporation, as described above. Cells were stained with PI (2 μg/ml; to label necrotic cells) for 10 minutes at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342. The cells were then observed and brightfield images were captured using an Olympus microscope. Fluorescent images were captured using a fluorescence microscope and analyzed. All image data displayed are representative of ≥3 randomly selected fields.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed to detect protein expression in synovial tissue samples and in in vitro experiments. Synovial tissue samples were frozen and powdered by grinding in liquid nitrogen and then thawed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer supplemented with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. A bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Beyotime) was used to quantify the proteins. Samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Primary antibodies for the following proteins were used for immunodetection: GSDME (catalog no. ab215191; Abcam), activated caspase 3 (catalog no. 9661; Cell Signaling Technology), and β‐actin (catalog no. AP071; Bioworld Technology). After washing with Tris buffered saline–Tween, the probed membranes were incubated with HRP‐labeled secondary antibodies (HRP‐labeled goat anti‐rabbit IgG [heavy and light chains] [catalog no. 111‐035‐003; Jackson ImmunoResearch] and HRP‐labeled goat anti‐mouse IgG [heavy and light chains] [catalog no. 115‐035‐003; Jackson ImmunoResearch]) and then visualized with an FDbio‐Dura ECL Kit (FD‐bio science). Protein expression was analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Generation of a mouse model of CIA

Male C57BL/6 wild‐type mice were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of Southern Medical University. C57BL/6 Gsdme‐knockout (Gsdme −/−) mice were generated by CRISPR/Cas‐mediated genome engineering (Cyagen Bioscience). CIA was induced in 8‐week‐old male wild‐type and Gsdme −/− mice. Chicken type II collagen (catalog no. 20012; Chondrex) was dissolved in 0.05M acetic acid (final concentration 2 mg/ml) and then emulsified with Freund's complete adjuvant (CFA) containing heat‐killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37RA (Chondrex). C57BL/6 mice were injected intradermally with a 100‐μl emulsion at the base of tail on days 1 and 21 (33). Clinical assessment of CIA was performed daily for each limb as previously described (34).

CIA was generated in DBA/1J mice as previously described (35). Eight‐week‐old male DBA/1J mice were immunized with 100 mg bovine type II collagen (2 mg/ml; Chondrex) emulsified 1:1 in CFA (containing 1 mg/ml M tuberculosis; Chondrex) on day 1 and then injected with Freund's incomplete adjuvant (Chondrex) on day 21.

All animals were maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions in the Laboratory Animal Center of Southern Medical University. The protocols for animal experimentation were approved by the Southern Medical University Experimental Animal Ethics Committee (no. 00171035 and no. 00181785).

Quantitation of inflammatory cytokines

The plasma levels of cytokines in mice were measured with commercially available enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay kits for IL‐1β (JM‐02323M2), IL‐6 (JM‐02446M2), and TNF (JM‐02415M2).

Statistical analysis

Graphs were prepared and statistical data were analyzed using GraphPad software version 8.4 and IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software. Arthritis scores in mice were compared using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. Data were compared between various groups by one‐way analysis of variance, Student's t‐test, or chi‐square test. Spearman's correlation analysis was used to evaluate correlations of the data. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

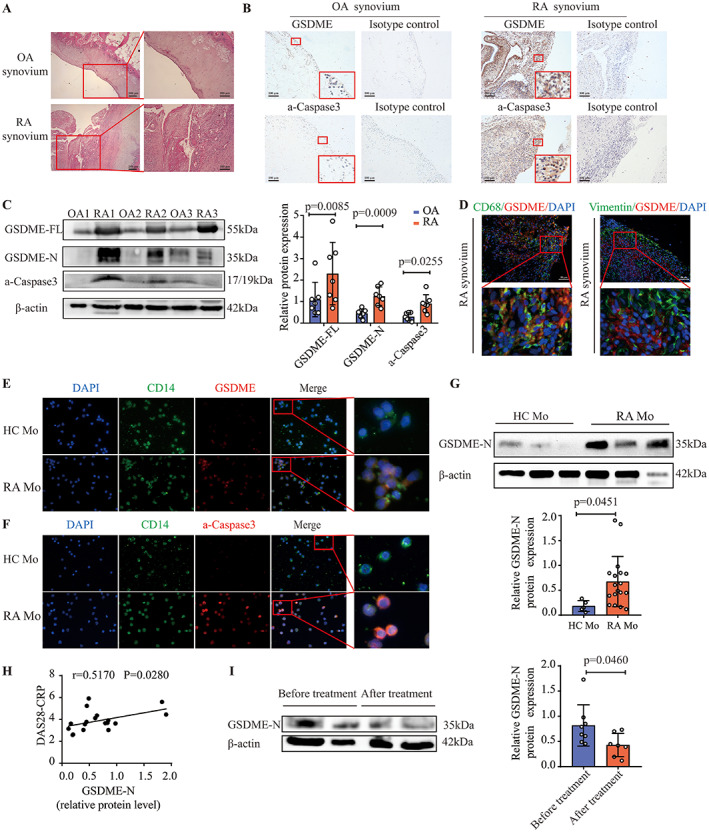

Elevated expression and activation of GSDME in synovial macrophages from RA patients

Persistent synovitis is a hallmark of RA. Consistently, we noted infiltration of inflammatory cells into the synovial tissue (Figure 1A). To assess the expression of GSDME, synovial tissue specimens were collected from RA patients and sex‐matched OA patients undergoing surgery. By immunohistochemical analysis, we first demonstrated higher expression of GSDME in synovial tissue samples from RA patients than in those from OA patients (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 2, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963). We further verified that the expression of GSDME‐N was higher in synovial tissue samples from RA patients than in synovial tissue samples from OA patients (Figure 1C). The increased expression of GSDME‐N in synovial tissue samples from RA patients led us to presume that caspase 3, which specifically cleaves GSDME, might also be activated. Indeed, the level of activated caspase 3 was significantly increased in the synovial membrane of RA patients compared to OA patients (Figures 1B and C and Supplementary Figure 3, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963).

Figure 1.

Increased expression and activation of gasdermin E (GSDME) in synovial macrophages and CD14+ monocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and positive correlation of GSDME level with RA disease activity. A, Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin–stained synovial tissue samples from patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and patients with RA. Right panels show higher‐magnification views (bars = 100 μm) of the boxed areas in the left panels (bars = 200 μm). B, Representative immunohistochemistry images of GSDME and activated caspase 3 (a‐caspase 3) expression in synovial tissue samples from OA patients (n = 7) and RA patients (n = 7). Lower boxed areas show higher‐magnification views (original magnification × 400) of the upper boxed areas (original magnification × 100). C, Western blot (left) and quantification (right) of the expression of full‐length GSDME (GSDME‐FL), the N‐terminal fragment of GSDME (GSDME‐N), and activated caspase 3 in synovial tissue samples from OA patients (n = 7) and RA patients (n = 7). D, Immunofluorescence images showing the expression of GSDME in CD68‐positive synovial macrophages and vimentin‐positive fibroblasts in synovial tissue samples from RA patients (n = 7). Bottom panels show higher‐magnification views (original magnification × 800) of the boxed areas in the top panels (bars = 50 μm). E and F, Representative images of immunostaining for DAPI, CD14, GSDME, and activated caspase 3 in peripheral blood monocytes (Mo) from healthy controls (HCs) and RA patients. For the merged images, right panels show higher‐magnification views (original magnification × 1600) of the boxed areas in the left panels (original magnification × 400). G, Western blot (top) and quantification (bottom) of GSDME‐N expression in peripheral blood monocytes from healthy controls and RA patients. H, Correlation of GSDME‐N expression, measured by Western blot analysis, in peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients (n = 18) with RA disease activity measured by the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the C‐reactive protein level (DAS28‐CRP). I, Western blot (left) and quantification (right) of GSDME‐N expression in peripheral blood monocytes from patients with active RA before treatment (n = 8) and after treatment with combination therapy that included tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (n = 7). In C and G, symbols represent individual subjects; bars show the mean ± SD protein level relative to β‐actin. Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963/abstract.

Next, we determined the expression of GSDME in synovial macrophages and fibroblasts, the 2 major cell populations in the synovium of RA patients, by immunofluorescence. The expression of GSDME was elevated in synovial macrophages but not in synovial fibroblasts (Figure 1D and Supplementary Figures 4 and 5, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963).

Strong correlation between GSDME‐N expression in RA peripheral blood monocytes and RA disease activity

Similar to synovial macrophages, we found higher expression of GSDME and GSDME‐N in peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients than in those from healthy controls (Figures 1E and G and Supplementary Figure 6, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963). Activated caspase 3 was consistently up‐regulated in peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients (Figure 1F and Supplementary Figure 7, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963). Interestingly, the expression of GSDME‐N correlated positively with the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the C‐reactive protein level (36) in RA patients (Figure 1H). Moreover, the expression of GSDME‐N was significantly reduced in RA patients after combination therapy that included TNF inhibitors (Figure 1I). These data suggest that GSDME is involved in the pathogenesis and progression of RA.

Propensity for pyroptosis in RA monocytes with higher GSDME expression

Given the high expression of GSDME in peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients, we purified peripheral blood monocytes from healthy controls and RA patients to further investigate pyroptosis in RA peripheral blood monocytes. After incubation in RPMI 1640 medium for 4 hours, peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients exhibited typical cell swelling and large bubble blowing from the plasma membrane (Figure 2A). Using fluorescence microscopy, increased numbers of PI‐positive cells were also observed in peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients compared to healthy controls (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure 8, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963). Moreover, LDH release was notably increased in the RA monocyte supernatant (Figure 2B). Flow cytometry revealed a higher percentage of PI‐positive cells among peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients than in those from healthy controls (Figure 2C). These results indicate that peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients are prone to spontaneous GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis.

Figure 2.

Increased capacity for pyroptosis in GSDME‐expressing peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients. CD14+ monocytes were purified from healthy controls and RA patients, and cultured for 4 hours in vitro. A, Left, Brightfield and fluorescence microscopy images of peripheral blood monocytes stained with Hoechst and propidium iodide (PI; red) (positive staining indicates lytic cell death). Bottom panels show higher‐magnification views (original magnification × 1600) of the boxed areas in the top panels (original magnification × 400). Arrows indicate pyroptotic cell bubbles. Right, Percentage of PI‐positive cells in 5 randomly chosen fields in peripheral blood monocytes from healthy controls (n = 7) and RA patients (n = 7). B, Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release from peripheral blood monocytes from healthy controls (n = 4) and RA patients (n = 4). C, Flow cytometric analysis (left) and percentage (right) of PI‐positive monocytes from healthy controls (n = 3) and RA patients (n = 3). D, Western blot of the expression of GSDME‐FL and GSDME‐N (left) and quantification of the expression of GSDME‐N (right) in monocytes from RA patients (n = 6), left untreated or treated with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) for 24 hours. Values are the protein level relative to β‐actin. E, Left, Phase‐contrast and fluorescence microscopy images of RA peripheral blood monocytes stained with Hoechst (blue) and PI (red). Phase‐contrast microscopy and PI staining images were merged. Bottom panels show higher‐magnification views (original magnification × 1600) of the boxed areas in the top panels (original magnification × 400). Arrows indicate pyroptotic cell bubbles. Right, Percentage of PI‐positive cells among untreated RA monocytes (n = 7) and RA monocytes treated with TNF (n = 7). Symbols represent individual subjects; bars show the mean ± SD. See Figure 1 for other definitions. Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963/abstract.

Similar to previous studies, we found high TNF expression in synovial tissue samples from RA patients (21) (Supplementary Figure 9, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963). To determine whether TNF induced GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis, we isolated peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients and treated them with TNF. As expected, TNF dramatically increased the expression of GSDME‐N in peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients (Figure 2D), and simultaneously increased the induction of pyroptosis, characterized by typical morphologic changes and PI staining (Figure 2E and Supplementary Figure 10, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963). Taken together, these results indicate that TNF alone induces pyroptosis in peripheral blood monocytes from RA patients.

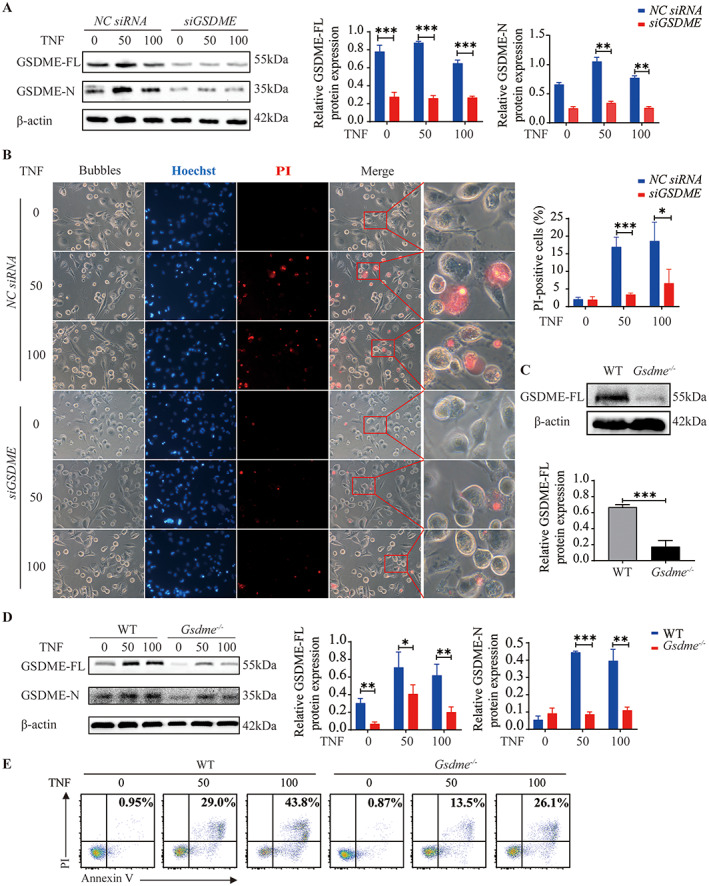

TNF induction of the expression of caspase 3/GSDME and pyroptosis in macrophages

To examine whether TNF triggers caspase 3/GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis in macrophages, we incubated THP‐1 cells with PMA to induce differentiation into macrophages. We considered TNF + CHX treatment to be a positive control because it induces the activation of GSDME and results in pyroptosis. TNF + CHX dramatically enhanced the expression of activated caspase 3 and GSDME‐N, and induced pyroptosis in THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) induction of pyroptosis of macrophages through activation of the caspase 3/GSDME pathway in vitro. THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages were seeded in 24‐well or 6‐well plates and incubated with different concentrations of TNF (ng/ml) for 36 hours or TNF and cycloheximide (CHX) (10 μg/ml; positive control) for 24 hours. A, Western blot (left) and quantification (right) of GSDME‐FL, GSDME‐N, and activated caspase 3 expression in macrophage lysates treated as indicated. Values are the protein level relative to β‐actin. B, Left, Phase‐contrast and fluorescence microscopy images of macrophages treated as indicated and stained with Hoechst (blue) and propidium iodide (PI; red). For the merged images, right panels show higher‐magnification views (original magnification × 1600) of the boxed areas in the left panels (original magnification × 400). Right, Percentage of PI‐positive cells. C, Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release from macrophages treated as indicated. D, Flow cytometric analysis of cells stained with annexin V/PI to determine cell death (left) and percentage of PI‐positive cells (right) among macrophages treated as indicated. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Bars show the mean ± SD. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P < 0.001. NS = not significant (see Figure 1 for other definitions). Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963/abstract.

Interestingly, when THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages were cultured in the presence of different concentrations of TNF for 36 hours, TNF alone also increased the expression of activated caspase 3, GSDME, and GSDME‐N in a concentration‐dependent manner (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figures 11A and B, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963). In parallel, cell swelling and large bubble blowing were significantly evident after TNF treatment (Figure 3B). The number of PI‐positive cells was increased after stimulation with TNF, as demonstrated by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry (Figures 3B and D). Moreover, TNF treatment resulted in an increased release of LDH (Figure 3C). To determine whether TNF had the same effect on pyroptosis in mouse macrophages, we generated BMMs from C57BL/6 mice. TNF induced pyroptosis in mouse BMMs, characterized by increased expression of GSDME‐FL and GSDME‐N and an increased number of PI‐positive cells. These results suggest that TNF, a key factor in the pathogenesis of RA, promotes the induction of macrophage pyroptosis by activating the caspase 3/GSDME pathway.

Reduction of TNF‐induced macrophage pyroptosis upon inhibition of the caspase 3/GSDME pathway

To further verify the role of caspase 3 in TNF‐induced macrophage pyroptosis, THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages were pretreated with a caspase 3–specific inhibitor (Z‐DEVD‐FMK) for 1 hour, followed by treatment with TNF for 36 hours. Z‐DEVD‐FMK treatment decreased the expression of activated caspase 3, GSDME, and GSDME‐N in macrophages treated with TNF (Figures 4A and 4B). Similarly, Z‐DEVD‐FMK reduced the induction of pyroptosis by TNF in THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages (Figures 4C and 4D).

Figure 4.

Reduction of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–induced GSDME‐mediated macrophage pyroptosis by the caspase 3–specific inhibitor Z‐DEVD‐FMK. After treatment with Z‐DEVD‐FMK for 1 hour, THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages were exposed to 50 or 100 ng/ml TNF. A, Representative immunofluorescence microscopy images showing the expression of GSDME in macrophages treated as indicated. Bars = 50 μm. B, Western blot of GSMDE‐FL, GSDME‐N, and activated caspase 3 expression (left), quantification of GSDME‐N expression (middle), and quantification of activated caspase 3 expression (right) in lysates of macrophages treated as indicated. Values are the protein level relative to β‐actin C, Left, Representative fluorescence microscopy and brightfield images of macrophages treated as indicated and stained with propidium iodide (PI; red). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst (blue). For the merged images, the right panels show higher‐magnification views (original magnification × 1600) of the boxed areas in the left panels (original magnification × 400). Right, Percentage of PI‐positive cells. D, Left, Flow cytometric analysis of cells treated as indicated and stained with annexin V/PI. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Right, Percentage of PI‐positive cells. In B, C, and D, bars show the mean ± SD. * = P < 0.05; *** = P < 0.001. See Figure 1 for other definitions. Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963/abstract.

We successfully silenced GSDME with siRNAs in THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages and then examined TNF‐induced pyroptosis in these cells (Supplementary Figures 12A and B, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963). The silencing resulted in decreased expression of GSDME‐N (Figure 5A) and reduction in TNF‐induced pyroptosis (Figure 5B). In addition, BMMs from Gsdme −/− mice showed decreased TNF‐induced pyroptosis (Figures 5D and E). Overall, these results indicate that inhibition of the caspase 3/GSDME pathway could reduce TNF‐induced pyroptosis of macrophages.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–induced pyroptosis in macrophages by GSDME silencing. A and B, After transfection with GSDME or negative control (NC) small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for 48 hours, THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages were left untreated or treated with 50 or 100 ng/ml TNF for the indicated times. A, Western blot of GSDME‐FL and GSDME‐N expression (left), quantification of GSDME‐FL expression (middle), and quantification of GSDME‐N expression (right) in macrophages treated as indicated for 36 hours after the silencing of GSDME. Values are the protein level relative to β‐actin. B, Left, Representative brightfield and fluorescence microscopy images showing the morphology of macrophages treated as indicated after the silencing of GSDME. For the merged images, right panels show higher‐magnification views (original magnification × 1600) of the boxed areas in the left panels (original magnification × 400). Right, Percentage of propidium iodide (PI)–positive cells. C, Western blot (top) and quantification (bottom) of GSDME‐FL expression in wild‐type (WT) and Gsdme −/− mice, showing the efficiency of Gsdme knockout. Values are the protein level relative to β‐actin. D, Western blot of GSDME‐FL and GSDME‐N expression (left), quantification of GSDME‐FL expression (middle), and quantification of GSDME‐N expression (right) in lysates of bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMMs) from WT and Gsdme −/− mice, cultured with the indicated concentrations of TNF for 36 hours. Values are the protein level relative to β‐actin. E, Flow cytometric analysis of murine BMMs treated as indicated and stained with annexin V/PI. In A, B, and D, bars show the mean ± SD. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P < 0.001. See Figure 1 for other definitions. Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963/abstract.

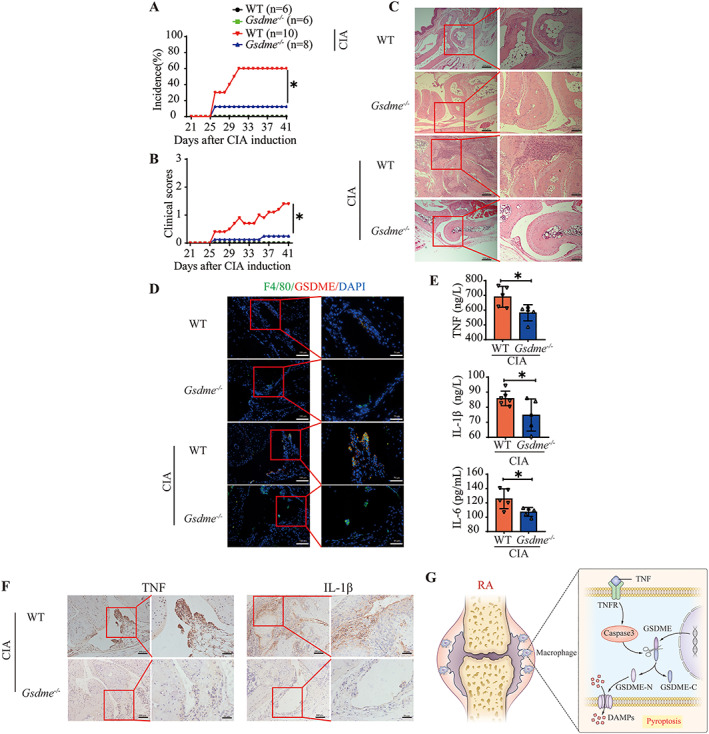

Alleviation of experimental arthritis in GSDME‐deficient mice

Given that RA synovial macrophages and circulating monocytes showed high expression of activated caspase 3 and GSDME, and that TNF activated caspase 3/GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis, we speculated that inhibition of pyroptosis by Gsdme knockout could protect mice against arthritis. To test our hypothesis, we immunized Gsdme −/− C57BL/6 (Gsdme −/− B6) mice and wild‐type C57BL/6 (B6) mice with collagen to induce arthritis, and evaluated clinical and immunologic features.

Gsdme −/− B6 and wild‐type B6 mice did not show any significant differences in the absence of collagen exposure (Figures 6A–C). However, compared with collagen‐treated wild‐type B6 mice, Gsdme−/− B6 mice had a dramatically decreased incidence of arthritis and decreased clinical arthritis scores following collagen exposure (Figures 6A and B). Moreover, synovitis was alleviated in H&E‐stained joint sections from collagen‐treated Gsdme −/− B6 mice compared to joint sections from collagen‐treated wild‐type B6 mice (Figure 6C). The expression of GSDME was up‐regulated in synovial macrophages from collagen‐treated wild‐type B6 mice (Figure 6D), as well as in those from collagen‐treated DBA/1J mice (Supplementary Figure 13, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963), but was markedly reduced in collagen‐treated Gsdme −/− B6 mice (Figure 6D). In parallel, the expression of activated caspase 3 was lower in synovial macrophages from collagen‐treated Gsdme −/− B6 mice than in those from collagen‐treated wild‐type B6 mice (Supplementary Figure 14, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963). The levels of circulating and synovial proinflammatory cytokines were lower in collagen‐treated Gsdme −/− B6 mice than in collagen‐treated wild‐type B6 mice (Figures 6E and F).

Figure 6.

Decreased arthritis incidence, clinical scores, and synovial inflammation in Gsdme‐deficient mice with collagen‐induced arthritis (CIA) compared to wild‐type (WT) mice with CIA. Male WT C57BL/6 mice (n = 10) and Gsdme −/− mice (n = 8) were immunized with chicken type II collagen emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant on days 0 and 21 for CIA induction. Mice of the same background without CIA were used as controls (n = 6 WT and 6 Gsdme −/− mice). A and B, Arthritis incidence (A) and clinical scores (B) in the indicated mouse groups. C, Hematoxylin and eosin–stained joint sections from WT and Gsdme −/− mice. Right panels show higher‐magnification views (bars = 100 μm) of the boxed areas in the left panels (bars = 200 μm). D, Immunofluorescence images showing the expression of gasdermin E (GSDME) in F4/80‐positive synovial macrophages from WT and Gsdme −/− mice. Right panels show higher‐magnification views (bars = 50 μm) of the boxed areas in the left panels (bars = 100 μm). E, Plasma concentrations of the cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β), and IL‐6 in the joints of WT and Gsdme −/− mice after CIA induction. Symbols represent individual mice; bars show the mean ± SD. F, Immunohistochemical staining for cytokines in the joints of WT and Gsdme −/− mice after CIA induction. Right panels show higher‐magnification views (bars = 50 μm) of the boxed areas in the left panels (bars = 100 μm). G, Model of the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). TNF induces pyroptosis by activating the caspase 3/GSDME pathway, promoting an inflammatory response. TNFR = TNF receptor; GSDME‐N = N‐terminal fragment of GSDME; GSDME‐C = C‐terminal fragment of GSDME; DAMPs = damage‐associated molecular patterns. * = P < 0.05. Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963/abstract.

DISCUSSION

GSDME shares ~45% sequence homology with other members of the gasdermin family and possesses the most conserved gasdermin‐N domain, and forms pores to execute pyroptosis. In tumors, GSDME also functions as a tumor suppressor by activating pyroptosis (16). The key role of GSDME in chemotherapy drug–induced organ toxicity was demonstrated in an animal experiment (12). However, the role of GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis in autoimmune diseases remains to be elucidated. We found a significant increase in the expression of GSDME and activated caspase 3 in synovial macrophages and circulating monocytes from RA patients. Activated caspase 3 specifically cleaves GSDME in the linker region, generating GSDME‐N. As expected, the expression of GSDME‐N was increased in monocytes and synovial macrophages from RA patients, and correlated positively with RA disease activity. Moreover, RA patients in remission exhibited lower expression of GSDME‐N. These findings provide the first clinical evidence of the key role of GSDME, identifying the close relationship between GSDME and RA pathogenesis. Interestingly, deletion of Gsdme in mice had a protective effect on clinical manifestations and synovitis in mice with CIA, supporting the notion of a pathogenic role of GSDME in RA.

Apoptosis and necrosis are 2 important programmed cell death procedures with different effects on inflammation and immune responses (37, 38). In apoptosis, cells shrink and disintegrate into apoptotic bodies that are usually engulfed by surrounding macrophages, leading to the noninflammatory nature of cell death (39). In necrosis, cells disrupt and release endogenous danger signals, resulting in inflammatory and immune responses (40). Unlike apoptosis, pyroptosis is a form of programmed necrosis with a highly proinflammatory nature (41). Although caspase 3 activation has long been regarded as the hallmark of apoptosis, the questions of why and how caspase 3 critically participates in the induction of pyroptosis are very fascinating.

GSDME levels play a role in determining the form of cell death in caspase 3–activated cells. Caspase 3 activation induces apoptosis in cells with low levels of GSDME but pyroptosis in cells with high levels of GSDME. We found that caspase 3 activation and GSDME cleavage led to obvious cell swelling with the formation of large bubbles, enhanced LDH release, and a high percentage of PI‐positive RA monocytes. In addition, in Gsdme −/− mice, the expression of GSDME was decreased in synovial macrophages and necrotic cell death was reduced in BMMs. Importantly, manifestations of arthritis and inflammatory cytokine release also decreased in Gsdme −/− mice after collagen challenge. We also confirmed that other related phenotypes which may lead to arthritis resistance, such as leukopenias or IgG synthesis problems, were not found in Gsdme −/− mice (Supplementary Figure 15, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.41963). Taken together, these results suggest that GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis may be strongly associated with the pathogenesis and progression of RA, further verifying the reliability of the “cell death immune recognition model.” We previously proposed that apoptosis induces immune tolerance, whereas necrosis initiates immune and inflammation responses (42). A “cell death immune recognition model” can help explain inflammation and autoimmunity in autoimmune diseases, and investigations into the detailed mechanisms of cell death–mediated immune responses may provide novel strategies for the treatment of autoimmune diseases (42, 43).

Given that GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis plays an essential role in the pathogenesis and progression of RA, we were curious to identify the initial trigger for pyroptosis in RA patients. In vitro, GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis can be triggered by chemotherapeutic drugs (11), metformin (44), apoptotic stimulators, and ATP (45). Consistent with previous clinical and experimental findings, our study indicates that TNF is abundant in synovial tissue samples from RA patients. Since TNF, combined with other stimulators, induces the activation of caspase 3, we wondered whether TNF itself could induce pyroptosis of monocytes and macrophages with high GSDME expression in RA patients. Indeed, TNF alone significantly enhanced the activation of caspase 3 and GSDME, and induced GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis of RA monocytes. Moreover, monocytes from RA patients in remission after treatment showed decreased expression of GSDME‐N and reduced pyroptosis. TNF also triggered GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis of THP‐1 cell–derived macrophages and BMMs. Pharmacologic inhibition of caspase 3 or genetic knockout of GSDME significantly blocked TNF‐induced pyroptosis. These results indicate that up‐regulation of TNF in RA patients might be an essential factor in promoting the activation of caspase 3 and GSDME and in the induction of pyroptosis in vivo.

The fact that TNF is mainly produced and released by monocytes and local macrophages further implies a feedback loop wherein monocytes and macrophages produce TNF and then respond to it by undergoing pyroptosis. Currently, TNF is recognized as a key pathogenic factor in RA and plays important roles in the development of T cells, production of antibodies, and acceleration of arthritis by promotion of the activation and proliferation of synovial fibroblasts (46, 47, 48). Therefore, inhibition of TNF is a widely recommended treatment for RA. Our findings provide another possible mechanism for the pathogenesis of RA, wherein TNF induces pyroptosis of monocytes and macrophages through the activation of the caspase 3/GSDME pathway.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that GSDME‐mediated pyroptosis is strongly involved in the pathogenesis of RA and that targeting GSDME may be a potential therapeutic approach in RA.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Sun had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design

He, Sun.

Acquisition of data

Zhai, Yang, Xu, J. Han, G. Luo, Y. Li, X. Li, Shi, X. Han, X. Luo, Song, Chen, Liang, Wu.

Analysis and interpretation of data

Zhai, Xu, Zhuang, Jie.

Supporting information

Disclosure Form

Appendix S1: Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Hongfen Shen and Dr. Chengzhi Huang for valuable assistance with the fluorescence‐activated cell sorting analysis.

Supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81873880 and 81671623), Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, China (2014B020212024), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2019A1515012113), Guangzhou Science and Technology Program Project (202002030342), and the President's Foundation of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China (QN2020006).

Drs. Zhai, Yang, and Xu contributed equally to this work.

Author disclosures are available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/action/downloadSupplement?doi=10.1002%2Fart.41963&file=art41963‐sup‐0001‐Disclosureform.pdf.

Contributor Information

Yi He, Email: heyi1983@smu.edu.cn.

Erwei Sun, Email: sunew@smu.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis [review]. Lancet 2016;388:2023–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mohammed FF, Smookler DS, Khokha R [review]. Metalloproteinases, inflammation, and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62 Suppl:ii43–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shi J, Gao W, Shao F. Pyroptosis: gasdermin‐mediated programmed necrotic cell death [review]. Trends Biochem Sci 2017;42:245–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kuang S, Zheng J, Yang H, Li S, Duan S, Shen Y, et al. Structure insight of GSDMD reveals the basis of GSDMD autoinhibition in cell pyroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:10642–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ding J, Wang K, Liu W, She Y, Sun Q, Shi J, et al. Pore‐forming activity and structural autoinhibition of the gasdermin family. Nature 2016;535:111–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 2015;526:660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aglietti RA, Estevez A, Gupta A, Ramirez MG, Liu PS, Kayagaki N, et al. GsdmD p30 elicited by caspase‐11 during pyroptosis forms pores in membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:7858–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sarhan J, Liu BC, Muendlein HI, Li P, Nilson R, Tang AY, et al. Caspase‐8 induces cleavage of gasdermin D to elicit pyroptosis during Yersinia infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E10888–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Broz P, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling [review]. Nat Rev Immunol 2016;16:407–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. He WT, Wan H, Hu L, Chen P, Wang X, Huang Z, et al. Gasdermin D is an executor of pyroptosis and required for interleukin‐1β secretion. Cell Res 2015;25:1285–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang CC, Li CG, Wang YF, Xu LH, He XH, Zeng QZ, et al. Chemotherapeutic paclitaxel and cisplatin differentially induce pyroptosis in A549 lung cancer cells via caspase‐3/GSDME activation. Apoptosis 2019;24:312–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Y, Gao W, Shi X, Ding J, Liu W, He H, et al. Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through caspase‐3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature 2017;547:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rogers C, Fernandes‐Alnemri T, Mayes L, Alnemri D, Cingolani G, Alnemri ES. Cleavage of DFNA5 by caspase‐3 during apoptosis mediates progression to secondary necrotic/pyroptotic cell death. Nat Commun 2017;8:14128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li YQ, Peng JJ, Peng J, Luo XJ. The deafness gene GSDME: its involvement in cell apoptosis, secondary necrosis, and cancers [review]. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2019;392:1043–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jiang M, Qi L, Li L, Li Y. The caspase‐3/GSDME signal pathway as a switch between apoptosis and pyroptosis in cancer. Cell Death Discov 2020;6:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Xia S, Kong Q, Li S, Liu X, et al. Gasdermin E suppresses tumour growth by activating anti‐tumour immunity. Nature 2020;579:415–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu X, He S. GSDME as an executioner of chemotherapy‐induced cell death. Sci China Life Sci 2017;60:1291–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Y, Yin B, Li D, Wang G, Han X, Sun X, et al. GSDME mediates caspase‐3‐dependent pyroptosis in gastric cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018;495:1418–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yu J, Li S, Qi J, Chen Z, Wu Y, Guo J, et al. Cleavage of GSDME by caspase‐3 determines lobaplatin‐induced pyroptosis in colon cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 2019;10:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mai FY, He P, Ye JZ, Xu LH, Ouyang DY, Li CG, et al. Caspase‐3‐mediated GSDME activation contributes to cisplatin‐ and doxorubicin‐induced secondary necrosis in mouse macrophages. Cell Prolif 2019;52:e12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tetta C, Camussi G, Modena V, Di Vittorio C, Baglioni C. Tumour necrosis factor in serum and synovial fluid of patients with active and severe rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1990;49:665–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee A, Qiao Y, Grigoriev G, Chen J, Park‐Min KH, Park SH, et al. Tumor necrosis factor α induces sustained signaling and a prolonged and unremitting inflammatory response in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:928–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu X. Innate lymphocytes in inflammatory arthritis [review]. Front Immunol 2020;11:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feldmann M, Maini RN. TNF defined as a therapeutic target for rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Nat Med 2003;9:1245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cheng Y, Yang F, Huang C, Huang J, Wang Q, Chen Y, et al. Plasmapheresis therapy in combination with TNF‐α inhibitor and DMARDs: a multitarget method for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2017;27:576–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Radner H, Aletaha D. Anti‐TNF in rheumatoid arthritis: an overview. Wien Med Wochenschr 2015;165:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aggarwal S, Gollapudi S, Gupta S. Increased TNF‐α‐induced apoptosis in lymphocytes from aged humans: changes in TNF‐α receptor expression and activation of caspases. J Immunol 1999;162:2154–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qian Q, Cao X, Wang B, Qu Y, Qian Q, Sun Z, et al. TNF‐α–TNFR signal pathway inhibits autophagy and promotes apoptosis of alveolar macrophages in coal worker's pneumoconiosis. J Cell Physiol 2019;234:5953–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO III, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:2569–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chanput W, Mes JJ, Wichers HJ. THP‐1 cell line: an in vitro cell model for immune modulation approach [review]. Int Immunopharmacol 2014; 23:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kayagaki N, Warming S, Lamkanfi M, Vande WL, Louie S, Dong J, et al. Non‐canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase‐11. Nature 2011;479:117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Inglis JJ, Simelyte E, McCann FE, Criado G, Williams RO. Protocol for the induction of arthritis in C57BL/6 mice. Nat Protoc 2008;3:612–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kruglov A, Drutskaya M, Schlienz D, Gorshkova E, Kurz K, Morawietz L, et al. Contrasting contributions of TNF from distinct cellular sources in arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:1453–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brand DD, Latham KA, Rosloniec EF. Collagen‐induced arthritis. Nat Protoc 2007;2:1269–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Van Riel PL. Disease Activity Score in rheumatoid arthritis. URL: https://www.das-score.nl.

- 37. Wallach D, Kang TB, Kovalenko A. Concepts of tissue injury and cell death in inflammation: a historical perspective [review]. Nat Rev Immunol 2014;14:51–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Calo G, Sabbione F, Vota D, Paparini D, Ramhorst R, Trevanu A, et al. Trophoblast cells inhibit neutrophil extracellular trap formation and enhance apoptosis through vasoactive intestinal peptide‐mediated pathways. Hum Reprod 2017;32:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nowak‐Sliwinska P, Griffioen AW. Apoptosis on the move [editorial]. Apoptosis 2018;23:251–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wallach D, Kang TB, Dillon CP, Green DR. Programmed necrosis in inflammation: toward identification of the effector molecules [review]. Science 2016;352:aaf2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kesavardhana S, Malireddi RK, Kanneganti TD. Caspases in cell death, inflammation, and pyroptosis [review]. Annu Rev Immunol 2020;38:567–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang F, He Y, Zhai Z, Sun E. Programmed cell death pathways in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus [review]. J Immunol Res 2019;2019:3638562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. He Y, Yang FY, Sun EW. Neutrophil extracellular traps in autoimmune diseases [editorial]. Chin Med J (Engl) 2018;131:1513–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zheng Z, Bian Y, Zhang Y, Ren G, Li G. Metformin activates AMPK/SIRT1/NF‐κB pathway and induces mitochondrial dysfunction to drive caspase3/GSDME‐mediated cancer cell pyroptosis. Cell Cycle 2020;19:1089–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zeng C, Li C, Shu J, Xu LH, Ouyang DY, Mai FY, et al. ATP induces caspase‐3/gasdermin E‐mediated pyroptosis in NLRP3 pathway‐blocked murine macrophages. Apoptosis 2019;24:703–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kruglov AA, Lampropoulou V, Fillatreau S, Nedospasov SA. Pathogenic and protective functions of TNF in neuroinflammation are defined by its expression in T lymphocytes and myeloid cells. J Immunol 2011;187:5660–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tumanov AV, Grivennikov SI, Kruglov AA, Shebzukhov YV, Koroleva EP, Piao Y, et al. Cellular source and molecular form of TNF specify its distinct functions in organization of secondary lymphoid organs. Blood 2010;116:3456–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Armaka M, Apostolaki M, Jacques P, Kontoyiannis DL, Elewaut D, Kollias G. Mesenchymal cell targeting by TNF as a common pathogenic principle in chronic inflammatory joint and intestinal diseases. J Exp Med 2008;205:331–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Disclosure Form

Appendix S1: Supporting information