Abstract

Context

The transition from medical student to junior doctor is challenging. Junior doctors need to become part of the physician community of practice (CoP), while dealing with new responsibilities, tasks and expectations. At the same time, they need to learn how to navigate the frontiers and intersections with the other communities of practice that form the Landscape of Practice (LoP). This study aims to understand how junior doctors experience interprofessional collaboration (IPC) and what elements shape these experiences considering their transition to clinical practice.

Methods

In this multicentre qualitative study, 13 junior doctors individually drew two rich pictures of IPC experiences, one positive and one negative. A rich picture is a visual representation, a drawing of a particular situation intended to capture the complex and non‐verbal elements of an experience. We used semi‐structured interviews to deepen the understanding of junior doctors' depicted IPC experiences. We analysed both visual materials and interview transcripts iteratively, for which we adopted an inductive constructivist thematic analysis.

Results

While transitioning into a doctor, junior doctors become foremost members of the physician CoP and shape their professional identity based on perceived values in their physician community. Interprofessional learning occurs implicitly, without input from the interprofessional team. As a result, junior doctors struggle to bridge the gap between themselves and the interprofessional team, preventing IPC learning from developing into an integrative process. This professional isolation leaves junior doctors wandering the landscape of practice without understanding roles, attitudes and expectations of others.

Conclusions

Learning IPC needs to become a collective endeavour and an explicit learning goal, based on multisource feedback to take advantage of the expertise already present in the LoP. Furthermore, junior doctors need a safe environment to embrace and reflect on the emotions aroused by interprofessional interactions, under the guidance of experienced facilitators.

Short abstract

Van Duin et al. demonstrate that junior doctors learn interprofessional collaboration implicitly, leading to practical implications to help junior doctors become effective team members.

1. INTRODUCTION

Taking the first steps as a doctor can be challenging for junior doctors. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 They need to translate theoretical knowledge from an academic setting into clinical actions in a work environment while coping with new responsibilities, tasks and expectations. 2 , 3 , 6 This transition to post‐graduate training brings uncertainty about junior doctors' new roles, for which many feel unprepared, and triggers insecurity in the newcomers regarding their competence. 1 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 At the same time, junior doctors have a strong sense of responsibility, want to demonstrate their independence and perceive ‘asking for help’ as ‘failing to cope’. 2 , 4 , 8 In this context of transition, interprofessional collaboration can be especially demanding. Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) happens when different health care professionals work together to provide optimal health care. 9 We believe that understanding how junior doctors engage in and experience their interprofessional collaborations may inform pedagogical strategies to foster their transition into autonomous practitioners capable of collaborating with different health care professionals.

With health care organisations worldwide becoming more complex and costly, interprofessional collaboration and education are crucial to enable mutual learning, effective teamwork and strengthen educational resources. 9 , 10 , 11 Junior doctors become a member of the physician community of practice (CoPP), which involves understanding one's own role as a physician and developing skills and practices (competence) within the physician community. At the same time, junior doctors also entre a landscape of health care practice (LoHCP)—a landscape of communities of practice brought together in the same working environment. The LoHCP is an interprofessional community with different health care professionals who share the same objective: enabling good patient care.

Junior doctors need to learn to navigate the LoHCP, which requires acquiring knowledge about the practices of other professions to understand what is required to thrive as an effective physician within an interprofessional health care team. 12 This ‘knowledgeability’ is defined by Wenger‐Trayner et al. 13 as the ‘complex relationships people establish with respect to a landscape of practice, which make them recognisable as reliable sources of information or legitimate providers of services’. Knowledgeability grows at the boundaries of individual communities, where members of the communities of practices interact, and is vital to become a good collaborator. 14

It becomes clear, that in order to engage in shared learning experiences, junior doctors' journey needs to not only take place inward—within the physician community—but also across boundaries of communities. 14 This may raise tensions, as each community has its own culture, customs and beliefs, and the newcomers need to find common ground within the interprofessional healthcare team and establish nurturing relationships, while adapting to their new role as doctors. 1 , 12 , 15

Successfully understanding and managing relationships with supervisors, nurses and other health professionals increases junior doctors' confidence in taking on their new role as doctors. 4 Research shows that team support facilitates the transition to autonomous practice, particularly when junior doctors perceive IPC as something positive. 2 , 4 However, when IPC is dysfunctional, it may be challenging to build supportive working relationships, and IPC may even become a burden. This burden is especially heavy for junior doctors who are not aware of their own roles and unfamiliar with the roles of other team members. 4

Although IPC in medical practice has been extensively studied, much less is known about junior doctors' experiences with IPC and the challenges they face as newcomers in the LoHCP. 16 , 17 Researchers have been focusing on identifying barriers and facilitators of productive IPC, and although this provides useful and valuable information regarding the nature and context of IPC experiences, it does not allow for an in‐depth understanding of the complexity of junior doctors' IPC experiences in relation to the dynamic transition process they embark on. 16 , 17 , 18 For instance, Olde Bekkink et al. 18 divided junior doctors' barriers to interprofessional communication into three levels: the clinical environment (the system), interpersonal relationships and personal factors. These levels correspond with aspects of interprofessional collaboration as follows. At the system level, junior doctors have to adapt to working in ever‐changing interprofessional teams and deal with high workloads. 17 , 18 Considering their interpersonal relationships, junior doctors often lack awareness of the role of other health professionals in the team, 17 , 19 struggle with power asymmetries 18 , 19 and feel unsupported. 18 On a personal level, junior doctors may experience low self‐confidence and imposter syndrome. 18 , 20

However, in order to understand the interplay between junior doctors and the IPC context, and how junior doctors internally and emotionally shape their IPC experiences in the background of their entrance in both the CoPP and the LoHCP, a research method is needed that allows for exactly that ‘finding out’ complex situations and everything that is (subjectively) connected to them. 21 A better understanding of how junior doctors experience IPC during their transition to practice may inform the design of pedagogical strategies to optimise the support of junior doctors' personal and professional development.

This study aims to understand (a) how junior doctors experience IPC and (b) what elements shape their experiences with IPC.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

We conducted a multicentre qualitative study, adopting an inductive constructivist thematic analysis to explore how junior doctors experience IPC. Our data corpus consisted of interviews and rich pictures. 22 We collected data using the U4 network and interviewed junior doctors from different specialties and institutions, aiming to enrich our understanding of this complex phenomenon. The U4 network is a collaboration between the European universities of Ghent (Belgium), Uppsala (Sweden), Göttingen (Germany) and Groningen (the Netherlands).

2.2. Participants and ethical approval

Previous studies have identified the first 2 years of clinical practice after graduation as the most stressful and demanding years in terms of preparation for IPC. 2 , 16 , 17 To broaden the understanding of IPC experiences, we purposefully selected 13 junior doctors representing a variety in gender, nationality and workplace (inside the hospital and in primary care). Participants were required to have a minimum of 6 months and a maximum of 3 years of work experience as a doctor. Junior doctors were approached in person or by e‐mail by the contact person of their university (PFP, SB and MHO) or by TSvD. Subsequently, junior doctors who were interested in participating were contacted by TSvD. She sent them the information letter and consent form by email, made an online appointment for the interview and collected the signed informed consent forms. The participants were informed that the data would be handled anonymously and confidentially, that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. The participants did not receive any compensation. All participants provided written informed consent.

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical committees from the relevant institutions for each participating centre: the NVMO ethical review board (file 2019.3.8), the Ethics Committee Ghent (file 2019/1389), the Ethics Committee University Medical Center Göttingen (file 11/10/19) and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (file 2019‐05379). None of the participants were supervised directly by members of the research team.

2.3. Data collection

Between March and August 2020, junior doctors from three different countries (Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands) were video‐interviewed by TSvD using Zoom® (Zoom 5.0.2), as this study took place during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Due to logistical difficulties, we were unable to include any Swedish junior doctors.

To explore junior doctors' experiences with IPC, we used a combination of rich pictures and semi‐structured interviews. A rich picture is a visual representation of a particular situation, intended to show the experience in all its complexity: context, connections, people involved, interrelations and emotions. 21 Rich pictures allow individuals to remember and tell the story of their experiences non‐verbally, which may enrich their memory recollection. 23 In addition, rich pictures help support a dialogue between participant and researcher, and the rich picture itself can also be aesthetically analysed, providing complementary information. 21 , 22 , 23 The semi‐structured interviews were used to deepen the understanding of junior doctors' depicted IPC experiences. 22

Participants were asked to draw two rich pictures: one of a rewarding or exciting experience concerning IPC while working as a junior doctor and one of a frustrating or challenging experience. TSvD gave all participants the same instructions (see Appendix 1) and showed them an example of a rich picture. 21 Participants used two white A4‐paper sheets and coloured pencils and/or markers. Drawing took approximately 40 min, after which participants shared their pictures with TSvD and the interview started (see Appendix 2 for a description of the interview structure). All interviews were conducted in English, audio‐recorded and lasted 40–60 min.

2.4. Data analysis

We performed an inductive constructivist thematic analysis, which involved an iterative process of data collection and analysis. In other words, the authors used early insights and ideas from the first rich pictures and interviews to further elaborate on specific concepts and ideas in the interviews that followed. 24 , 25 The pictures and interviews were analysed in a parallel and dialogical process. Due to the richness of our data, every included sample held much relevant information to reaching our study aim. 26 Throughout the analysis process, TSvD, MAdCF and MACV engaged in frequent discussions to ensure that all aspects of the data would be thoroughly analysed, capture a broad range of perspectives and reach a mutual understanding of codes, categories and themes.

The first step of data analysis already started during the interview in which both TSvD and the participant actively and subjectively made sense of the depicted experience. 27 All interviews were manually transcribed verbatim by TSvD. To further familiarise with the data, the transcripts were repeatedly and actively read. The interview transcripts were analysed as follows (parallel with the rich pictures, see also the paragraphs below): (1) initial line‐by‐line open coding of the first transcripts (summarising each sentence with a short description, e.g., ‘feeling insecure,’ ‘knowing the team’ and ‘bearing responsibility’); (2) focussed coding of the subsequent transcripts (after each interview), constantly comparing new data with previously analysed data and merging similar codes into coding categories (e.g., ‘alignment’ and ‘mutual respect’); (3) connecting the coding categories from step two into meaningful groups (‘personal’, ‘interpersonal’ and ‘context’) and (4) relating different codes (selective coding) and interpreting the meaning of the data (e.g., ‘identity’, ‘power’ and ‘support’), sorting them into themes. Coding was data driven, adopting an inductive framework. Data organisation was supported by Atlas.ti version 8 (atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and the use of thematic maps. The thematic maps helped to further organise the themes and to identify overarching themes.

Parallel to exploring the interview transcripts, TSvD, MAdCF and MACV aesthetically analysed the rich pictures in dynamic group sessions. In each session, TSvD asked MAdCF and MACV (who were blind to the respective interview) to describe the drawing and elaborate on the use of space (including connections and relations), the use of colour, the different elements (symbols, metaphors and emotions) and finally to make a general interpretation of the drawing. 28 After the aesthetic analysis, TSvD shared the story behind the drawing with MAdCF and MACV, further exploring the meanings and assumptions behind the drawing and connecting the drawing with the interview. After each group session, TSvD organised the discussed data into patterns and shared the summary with MAdCF and MACV to consolidate a mutual understanding.

The final step of the rich picture analysis was the gallery walk. For the gallery walk, all rich pictures were presented simultaneously on a wall and viewed by a selected group of researchers. The group consisted of an educational scientist experienced with rich pictures, an experienced supervisor in anaesthesiology, a junior doctor (who did not take part in the interviews), a midwife and researchers TSvD and MACV. During the gallery walk, the group reflected on the different aspects of the pictures, for example, how the junior doctor related to the team (connectedness, nearness to others vs. distance), the position of the junior doctor in the drawing (vs. position of the depicted patient), the environmental influences (workload, time and settings that influence the collaboration) and the emotional atmosphere. The gallery walk was structured as follows. First, the group looked at the pictures for 30 min, after which they discussed their interpretations for 40 min, coming to a shared understanding of the meanings. Second, the group looked at the pictures of the rewarding/exciting experiences and the frustrating/challenging experiences separately for 20 min, looking for similarities and differences between the two groups of drawings. Finally, the group engaged in a meaning‐making discussion that lasted for 40 min. TSvD guided the gallery walk and audio recorded the discussions. 23

The rich picture analysis complemented the coding process and the identification of themes.

2.5. Research team and reflexivity

Our research team's different perspectives contributed to the enrichment of this study. As a year 6 medical student, TSvD's close proximity to the junior doctors facilitated the understanding of their experiences and fostered trust to gather sensitive data. MAdCF, an internal medicine specialist experienced in qualitative research as well as rich pictures, contributed a different cultural perspective. Together with MACV, a gynaecologist and senior educator, MAdCF contextualised the findings regarding the reality of clinical and educational practices, based on their experiences as senior physicians supervising undergraduate and postgraduate medical trainees. ADCJ is a professor in medical education, experienced in qualitative research and helped identify the relevant data, critically revising the findings. The foundation of this research was laid by the U4 network, with PFP, SB and MHO all having leading positions in both interprofessional collaboration and education in their respective institutions, broadening the team's understanding of IPC and shaping the conceptualisation and design of the study, as well as the relevancy of the data.

3. RESULTS

A total of 13 junior doctors (7 from the Netherlands, 3 from Germany and 3 from Belgium; Table 1) drew two situations related to IPC, which they labelled as a positive and a negative experience. Their professional experience as a junior doctor varied from 8 to 27 months. The variety in participants' nationalities and specialisms, including surgical, non‐surgical and primary care workplaces, provided a broad view of IPC in various settings. Junior doctors depicted an array of emotions in both positive and negative experiences. IPC experiences were shaped by the junior doctor (personal), the interprofessional team and the supervisor (interpersonal), and the context of the situation (system). We grouped the elements influencing how junior doctors experienced IPC into three themes: (1) learning IPC implicitly (feedback, emotions and supervision); (2) transitioning into a doctor (role perceptions and team dynamics) and (3) judging the value/quality of the collaboration by its perceived outcome (good or bad experience) (see Figures C1–C3 for evolution of thematic map).

TABLE 1.

Demographics

| Participant | Gender | Age | Months of working experience | Specialty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Female | 26 | 19 | Orthopaedics |

| P2 | Male | 27 | 24 | Mentally disabled care |

| P3 | Female | 27 | 11 | Psychiatry |

| P4 | Male | 27 | 24 | Emergency medicine |

| P5 | Female | 28 | 12 | Gynaecology |

| P6 | Female | 28 | 13 | Internal medicine |

| P7 | Male | 24 | 8 | Paediatrics |

| P8 | Female | 25 | 9 | Geriatrics |

| P9 | Female | 27 | 17 | Radiotherapy |

| P10 | Female | 25 | 10 | Intensive care |

| P11 | Female | 26 | 22 | Family medicine |

| P12 | Female | 26 | 23 | Family medicine |

| P13 | Male | 30 | 27 | Anaesthesiology |

3.1. Learning IPC implicitly: Feedback, emotions and supervision

3.1.1. Feedback

Learning IPC often occurred implicitly. Supervisors' feedback seldom addressed the junior doctor's performance as a collaborator nor did it provide an opportunity for junior doctors to engage in conversations about their leadership skills. When junior doctors referred to feedback sessions, these either centred on the junior doctor's performance (‘you should check more often’) or on the team's performance (‘we worked really well together’). Junior doctors received no feedback regarding their attitudes or behaviours from physicians within the physician group. Furthermore, the environment surrounding the interprofessional team did not facilitate learning from feedback due to interprofessional boundaries, which created professional/cultural silos. In these silos, empowered feedback givers at the workplace were mainly (senior) physicians and feedback from other team members regarding collaborative skills was rare. Consequently, junior doctors did not see the interprofessional team as an available and meaningful source of feedback regarding their collaborative skills. In the few cases when junior doctors did receive interprofessional feedback, it was indirect: head nurses transferring complaints from nurses to the junior doctor or a senior physician passing on nurses' wishes as conveyed to him by a head nurse. Due to the boundaries separating the professional silos, junior doctors and the other health professionals did not engage in conversations about attitudes, beliefs and expectations. Without this feedback, junior doctors lacked awareness of how their behaviour affected the team, preventing them from improving their working relationships. As there were no IPC communication channels between the junior doctor and the interprofessional team, a frustrating IPC experience remained frustrating without the team coming together to understand each other's perspectives, as the following quote illustrates:

… it wasn't a long discussion, but she [an experienced nurse] did not agree with what I said. It was not in the words [what she said], it was more how they [both nurses] reacted. I think I was already disappointed in the communication … I was thinking about all the other decisions, and not this one. So yeah, for me it was a waste of time. (P11)

3.1.2. Emotions

Junior doctors found IPC experiences emotional, which seemed to distract their ability to learn from IPC experiences. In positive IPC experiences, junior doctors felt happiness and a strong sense of pride—of both themselves and the whole team. When asked why they had positive feelings about the collaboration, the answer often revolved around their own performance. In these positive experiences, junior doctors felt supported by the team and could share responsibilities, which made them feel confident and competent as beginning physicians. However, because of this positive atmosphere (‘all is well’), junior doctors did not seem to reflect ‘further’ on how they contributed to IPC or how others experienced their participation and role in the team.

I did not show it to anyone, but I was really anxious, and I felt really supported by the nurse, who was with me, that I was able to do this, to do something new, try something new, in a safe environment. And this picture [of a positive IPC experience] not only depicts this one nurse, but also all the other nurses in the hospital I'm working with. Because I'm doing a lot of new things, and they allow me to do that, and they work in a team with me. So that feels really good. (P5)

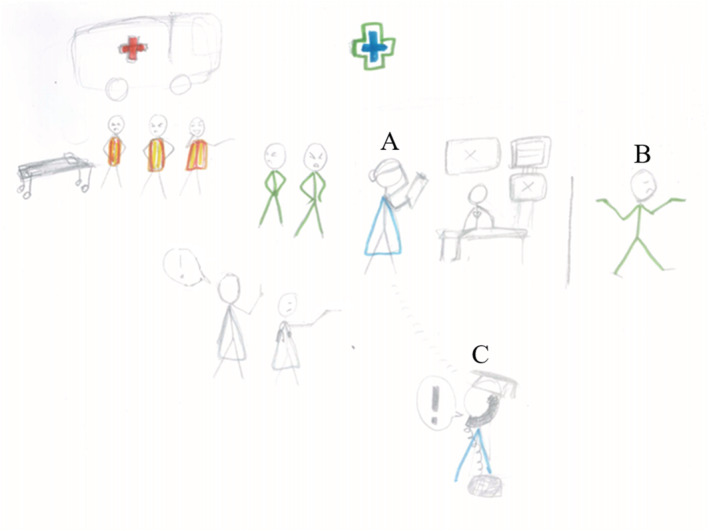

In negative IPC experiences, junior doctors experienced anger, sadness, frustration and sometimes guilt. They struggled to modulate their emotions, resulting in an inability to take on a ‘helicopter view’ of the situation or to understand the perspectives of others in the team. Underlying these emotions was often a sense of ‘helplessness’, and, at the time of drawing, junior doctors still did not understand what had gone wrong in challenging collaborations (especially in cases of conflict). As they did not share these emotions within the interprofessional team, junior doctors felt alone and unsupported, especially regarding their responsibility for good patient care (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

This rich picture tells the story of a junior doctor (A, Sarah, fictitious name) who was called to the emergency department to evaluate and admit a psychiatric patient. Sarah decided to exclude a cardiologic cause for the patient's symptoms. Still, the emergency crew clearly wanted Sarah to admit the patient as fast as possible and leave the emergency department. The tension increased when Sarah tried to order additional laboratory tests but was denied by the angry emergency crew. Sarah felt like an outsider and perceived antipathy from the whole team. This antipathy is depicted by their angry and even jeering faces (top left) and by a nurse walking away from Sarah (B, top right), showing she did not have the time to interact. Sarah felt belittled, intimidated and sad by the fact that she had been judged before she was able to explain her side of the story. In the meantime, her supervisor kept insisting and pressing her over the phone to admit the patient only after checking the tests. In the end, Sarah felt ashamed that she was not self‐confident enough and did not handle the situation smoothly. She also felt embarrassed that she had to follow her supervisors' orders without considering the opinions of the emergency crew. Sarah did not share her feelings with the emergency crew, neither did she discuss them with her supervisor. Only the technicalities of the case were addressed during supervision. The supervisor (C) wears a professor's hat as a metaphor for his top‐down behaviour [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

It's just a lot of bad vibes coming towards me, and a lot of question marks, me showing not knowing how to reach my co‐workers, or how to reach my supervisor. Why wasn't I called by the head nurse of the department? And me trying to do what's best for my patient, but the feeling I got out of it was not a feeling I did what was best for the patient, but the feeling I got out of this was: well, apparently I cannot do anything good for anyone at all. (P9)

Considering both positive and negative IPC experiences, junior doctors did not seem equipped to learn from these situations or deepen their reflections on how they related to the interprofessional team. Junior doctors also missed opportunities to become aware of how the interaction between them and the team could be modulated and improved.

I gave him [the nurse] the feeling that I was superior, but that's absolutely what I did not want to do …. To this date, I actually do not really know what went wrong, but it somehow did. And I tried to talk through it afterwards, and eh, yeah, we are good again, but it did not really resolve the conflict on that day. Somehow I pissed him off, and I do not know how or why. (P13)

3.1.3. Supervision

Striking was that in these turbulent IPC experiences, junior doctors did not reach out to their experienced physician supervisor for help or guidance. Although hierarchy was mentioned as a barrier to ask for help, the main reason was that IPC and supervision were seen as separate entities (Figure 1). One junior doctor was unable to resolve a conflict with a nurse and explained why he did not approach his supervisor, a belief that other junior doctors shared:

It would not really make sense that they [supervisors] would be interested … there was no patient at risk or anything, it was just like a personal thing, of communication, or miscommunication between me and the nurse. And nothing really to do with mistakes or error in the patient's care. (P13)

This quote illustrates that junior doctors who do not see how directly IPC may impact patient care and safety. Both junior doctors and supervisors seemed to not perceive IPC as a learning objective, which resulted in supervisors not opening conversations about IPC, and junior doctors not looking at their supervisors as role models for collaborative behaviour. Furthermore, the other health care professionals did not appear in the drawings as formal and empowered feedback givers.

3.2. Transitioning into a doctor: Role perceptions and team dynamics

3.2.1. Becoming a doctor

While transitioning into their new roles, junior doctors perceived they should be able to work autonomously and bear sole responsibility. They felt they needed to be the one ‘in power’ in the team, making the medical decisions independently. One junior doctor described it as follows:

… as a doctor you have a certain responsibility, towards the patients but also towards the people you work with, especially in a hierarchy, you need to … It's really hard in the beginning to accept that you are like the higher person, because you are used to being the lowest person, but eventually you are the one with more responsibility, because you decide or not whether a patient can go home. (P1)

Most junior doctors did not feel prepared to bear the responsibility of working autonomously. They felt insecure and unsure of their competencies. Simultaneously, they perceived pressure from the team and the supervisor to ‘do what was expected of them,’ ‘know what to do’ and ‘take control of the situation’. In this context, some junior doctors felt like they were ‘playing a character’ by ‘pretending’ to make independent medical decisions, by telling team members what to do and perhaps most consequentially, by not asking for help to show autonomy and confidence—all threats to interprofessional engagement and patient safety. This dichotomy between feeling insecure and the urge to take responsibility and control often made junior doctors feel alone, unsupported and solely responsible for patients' clinical outcomes. These feelings triggered a strong focus on the self. With a primary focus on navigating their own roles, junior doctors struggled to connect with other team members and understand the roles of others, creating a gap between them and the team that was difficult to bridge. However, as junior doctors grew in competence and self‐assurance, they became more comfortable in their roles, managed their expectations better and opened the door to accept help from the team.

I think as a young doctor you are very often looked at as if you should be in control, and that you really do not experience that you are in control. Because usually as a young doctor you are just the next young doctor in line for the nurses. As in: ‘You're just a new doctor, and the old [previous] doctor was there for a year’, so they [the nurses] are used to a more experienced person, and they know what you should be able to do. And when you get there you are like ‘I have no idea what I have to do’. And then it's very comforting that after a while you get that feeling [knowing what to do] as well. Yes, they [the nurses] want something from me, but I know how I can help them with that. And well, that's pretty nice. (P8)

3.2.2. Feeling supported by the team

When junior doctors worked in naturally supportive teams, it generated a sense of control that reassured junior doctors' professional identity, contributing to its development and facilitating (interprofessional) learning opportunities. This reassurance eased the transition considerably. Also this supportive environment provided a strong sense of ‘doing it together’ and gave junior doctors a feeling of belonging in the team. Junior doctors reported support happening in the following ways: (a) experienced team members advising and guiding the junior doctor; (b) team members reassuring the junior doctor/team members complimenting the junior doctor's work (boosting junior doctors' confidence) and (c) other team members doing a good job themselves, which gave junior doctors a feeling that they could rely on the team and share responsibility. One junior doctor felt unprepared for a task but could rely on a supportive team which did not threaten her autonomy but enhanced it, providing her with a sense of control:

And so trying to de‐escalate the patient I get a bit stressed, or I get to the end of my abilities, because it does not work very well at first. I cannot handle the patient alone, but on the ward there are two nurses who are very experienced, and trained for these situations, and stay calm, and they have my back, so they do not directly tell me what to do, but they stand behind me, and guard me, and they step in whenever the situation might get a little bit dangerous. So they make sure that the situation stays under control …. (P3)

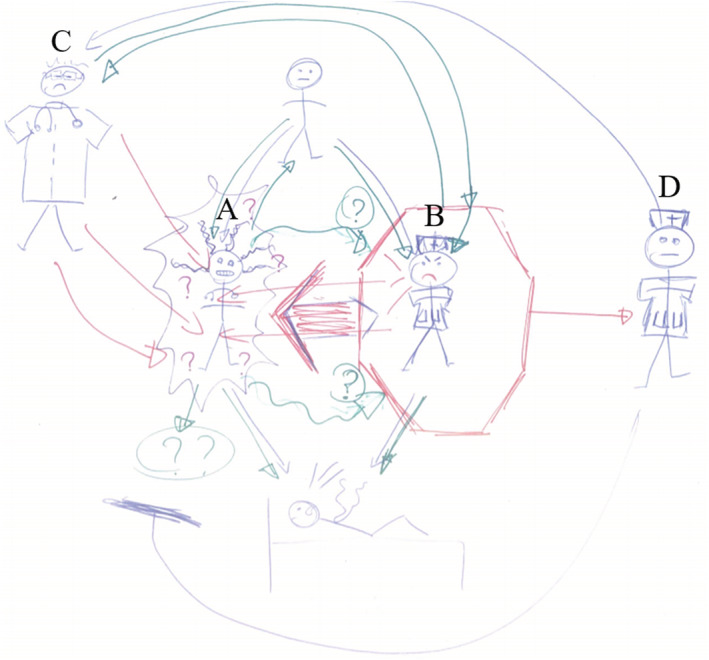

3.2.3. Feeling supported by the supervisor

Besides the interprofessional team, supervisors played a key role in the way junior doctors experienced IPC. In general, supervisors had leading positions and power inside the interprofessional teams. They could use their power to give space and autonomy to junior doctors to develop into their role as a doctor and find a place inside the team. Furthermore, the supervisors modulated the complexity of junior doctors' tasks and could build up their self‐confidence. However, they could also weaken junior doctors' positions by taking over during a collaboration, ‘belittling’ them by changing junior doctors' clinical decisions or leaving them out of the decision‐making process altogether (Figure 2). When excluded from the decision‐making, junior doctors felt insecure and ‘outside’ of the team, damaging the ongoing working relations with the other team members.

FIGURE 2.

This rich picture tells the story of a junior doctor (A, Jane fictitious name) taking care of a patient with advanced brain tumour—stage IV glioblastoma (figure lying in bed at the bottom of the drawing). The patient was receiving palliative care at the radiotherapy department and would return to the residence where he was living. The nurse (B) confronted Jane the morning of his discharge, telling her she disagreed with the patient's discharge and treatment plan. Jane listened to the nurse's concerns in an engaging conversation and changed some of the medication to be prescribed for the patient. During the process, Jane felt like hitting a wall, with the nurse coming across aggressively bringing forth personal arguments as Jane did not take up all of the nurse's advice. After this, Jane received a call from her supervisor (C), telling her he had received a call from the head nurse of the department (D) and that he would change the treatment. Jane felt betrayed (‘stabbed in the back’). After such a long conversation with the nurse, she did not expect to be crossed over like this. She felt no support or respect from the team. Jane drew herself chaotic, with the red lines representing all the bad vibes coming towards her. The big red arrow indicates the angry nurse shouting directly at her. The question marks show Jane's insecurity, feeling so responsible to do what she thought was best for the patient and her failure in reaching out to her co‐workers. Jane drew her supervisor a bit outside of the situation, adding to it that there was a big threshold between them [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

One junior doctor had an extensive discussion with a nurse about the treatment of a patient in palliative care, after which the nurse went to her supervisor. In the end, the supervisor changed the treatment without discussing it with the junior doctor:

… this one nurse was obviously not happy with that [the decision regarding care of the patient]. But I was, how to say, confident that the patient was being helped in the correct and humane and respectful way. And then, after that … I had to call my supervisor for something else, and then he said: ‘oh, by the way, I got a call from the head of the, the head nurse of the department’, who was called by the nurse who I spoke forty minutes with, ‘I'm going to change this and that in the treatment of the patient before he leaves to his residence’. Eh, so yeah, that was a very shitty feeling. (P9) (Figure 2)

This quotation shows the interplay between the team, the supervisor and the junior doctor and how this can affect junior doctors' perceptions of IPC and their confidence as autonomous doctors.

3.3. Judging the value/quality of the collaboration by its perceived outcome: Good or bad experience

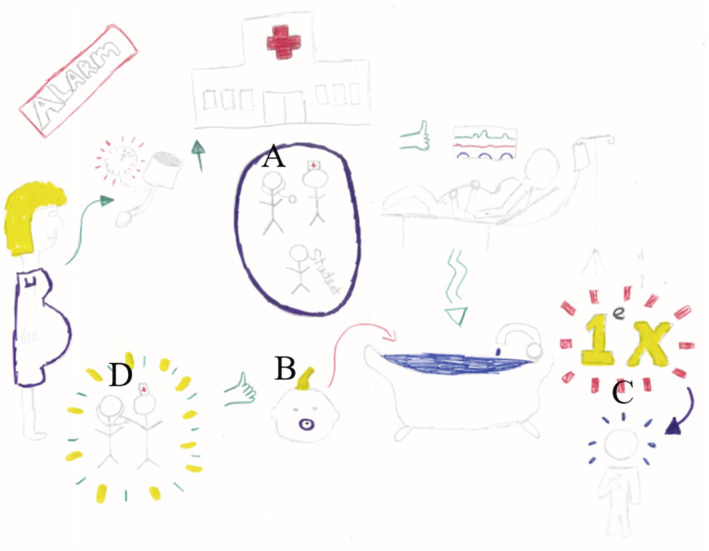

3.3.1. Good experience

The outcome of the IPC experience impacted how junior doctors judged the collaboration. When asked to draw a positive IPC experience, junior doctors depicted clinical situations with positive patient outcomes (e.g., a healthy newborn and a mother being able to stay with her children and success in reducing length of hospital stay). Along with the good clinical outcome came a sense of pride and happiness that increased junior doctors' self‐esteem and was transferred to the team (Figure 3). These positive feelings shaped the whole perception of the particular collaboration.

FIGURE 3.

This rich picture tells the story of a junior doctor (A, Emily fictitious name) working in gynaecology. Emily assisted a pregnant woman who came in with a high blood pressure during her delivery. The pregnant woman asked to give birth in a bath, which made Emily insecure as she had never done this before. Emily felt supported by the midwife (figure standing next to A), which made her confident enough to try a bath delivery for the first time. Together, Emily and the midwife assisted the bath delivery and it went well: The woman had a positive birth experience and the baby was healthy (indicated by the green thumb up next to the baby's head, B). Emily felt so proud to have successfully managed her first bath delivery (C). Afterwards, the midwife complimented Emily, represented by the green and yellow circle around Emily and the midwife, and the midwife putting her hand on Emily's shoulder (D). The midwife expressed that she was very happy that Emily tried it and felt that Emily was in control of the situation. Emily explained that she, the midwife and student midwife worked and acted as a team and that the three of them were in the centre of the experience of the delivering woman and her partner [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

… her delivery was great, so that also really felt like we really did this, we as a team, can do this. The hospital is also a good place to deliver your baby, and you can have a good experience. And that's not only me, that's the whole team, that's the nurses who are with me, because without them I could not do it. So that's why I'm very proud of what I've drawn here, the circle in the middle of the picture, with all three of us, and also our student, they are really a support to all the ladies [women in labour/women delivering a baby]. (P5) (Figure 3)

3.3.2. Bad experience

When asked to draw a negative IPC experience, junior doctors depicted situations related to unmet therapeutical goals (including lengthening of hospital stay and a patient who suddenly became critically ill) or conflicting situations. These ‘bad outcome’ experiences had in common that the junior doctor did not feel happy with the way the situation turned out. Due to the negative emotions associated with a bad outcome, junior doctors also perceived the collaboration as negative. Interestingly, the strong negative emotions drove junior doctors to take a central position in the story and the picture, with the patient in the background. Negative IPC experiences, therefore, were much more about junior doctors themselves, and less about patient care and the team, even though the situation was judged on the basis of perceptions of the latter two. One junior doctor explained why she drew herself in the middle of the picture representing a negative IPC experience:

I drew myself quite big in the centre of the drawing. And my supervisor behind me, but a bit higher. But yeah, because I was, I think in my head this drawing was about me. And I see I drew the nurse a few times smaller. But I wanted to show that I was really frustrated with myself. And I think in the other drawing [of a positive IPC experience] I just wanted to show the whole package of the experience, that wasn't so much about myself, but more about the teamwork. (P10)

In summary, the emotions aroused by the clinical experience were determinant to juniors doctors' judgements about the quality of IPC. Supervisors and team members contributed to this perception. When the team complimented the junior doctor after a ‘good ending’, the perception that a good outcome equalled a happy team and good collaboration was fuelled (Figure 3). Vice versa, when there was a conflict, an unhappy team equalled a bad collaboration and a negative IPC experience. The fact that IPC was not an explicit learning goal made the reflections about team collaboration superficial, for instance, not including knowledgeability about other health professions, leadership and participation as a collaborator.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we addressed junior doctors' experiences with IPC during their transition to clinical practice. We identified three themes that shaped junior doctors' experiences with IPC: (1) learning IPC implicitly (feedback, emotions and supervision); (2) transitioning into a doctor (role perceptions and team dynamics) and (3) judging the value/quality of the collaboration by its perceived outcome (good or bad experience). In accordance with these three themes, we found that junior doctors had difficulty bridging the gap between themselves and the interprofessional team. First, junior doctors learn IPC implicitly—receiving no or only indirect feedback from the other health professionals regarding their collaborative efforts due to the existing interprofessional boundaries. This lack of feedback made it difficult for junior doctors to become aware of and understand different perspectives and prevented them to reflect on and learn from the strong emotions often aroused by IPC experiences. Second, while becoming a doctor, junior doctors felt they needed to be autonomous, to be ‘in control’ and to ‘know what to do’. This pressure led junior doctors to a self‐centred stance with their main focus on their new roles and performance, losing sight of how they relate to the interprofessional team—often discarding the available help of the team members surrounding them. Third, the emotions aroused by clinical experiences determined juniors doctors' judgements about the quality of IPC, instead of forming the basis for an open conversation about team collaboration.

Junior doctors need to become part of the community of physician practice (CoPP), while learning how to navigate the frontiers and intersections with the other communities that form the LoP. 14 It is clear that the two processes—becoming a member of the CoPP and navigating the LoHCP—occur in parallel. However, where junior doctors receive formal and direct feedback regarding their competence as a physician, feedback on their collaborative performance within the LoHCP—and by members of the LoHCP— is implicit and indirect. This limits interprofessional learning opportunities, which in turn delays their development into good interprofessional collaborators, that are able to travel both inward within their CoPP, as well as across boundaries to journey between communities in the LoHCP. 14

Stalmeijer and Varpio 12 argued in their recent cross‐edge cutting paper that, in order to prepare junior doctors for their roles in the LoHCP, an interprofessional approach to workplace learning and guidance is required. We follow their lead and suggest practical implications for medical educators to facilitate membership of junior doctors in both the CoPP and the LoHCP.

4.1. Practical implications

4.1.1. Empowering the whole team as feedback givers

Our study shows that boundary crossing is hampered by cultural silos, with each health care profession having its own culture, including behaviours, beliefs, attitudes, values and customs. 15 Within these cultural silos, only the physician supervisor is seen as an available credible source of feedback. Currently, the intraprofessional status quo—physicians teaching physicians—is maintained by the medical profession's power over the other professions. 29 To create interprofessional learning opportunities, the workplace needs to stimulate cross‐professional feedback. By empowering the whole team (i.e., nurses, physiotherapists, midwives, social workers and others) as feedback givers, the interprofessional team's role can be formalised within the workplace. 12 An important prerequisite is that power needs to be redistributed, starting with physician supervisors deliberately inviting the interprofessional team in the feedback process, taking advantage of other health professionals' comments on the collaborative attitude of both junior doctors and supervisors to start an IPC conversation. 30 By doing this, the physician supervisor acts as a collaborative role model, making the cultural silos more transparent, empowering the interprofessional team and legitimising their feedback. It is important to train feedback‐givers in giving feedback, 31 including how to make feedback specific and—in cases of challenging collaborations—how to give constructive feedback with a focus on learning. 32 , 33 Feedback givers should take into account that insecure junior doctors with low self‐confidence, non‐consolidated identities and limited exposure to other health professionals might be less receptive to receive (corrective/constructive) feedback. 30 , 34 Adopting multisource feedback (MSF) could help operationalise and facilitate the implementation of regular and formative interprofessional feedback, also helping junior doctors to actively seek feedback on their collaborative skills form the relevant CoP. 35

4.1.2. Setting IPC as an explicit learning goal

Both supervisors and junior doctors did not perceive IPC as an explicit learning goal: Feedback is given on (professional) performance, but not on how this performance is achieved in collaboration with the team. This mismatch calls for integrated interprofessional training, where both collaborative and professional (physician) competencies are acquired together. By making IPC an explicit learning goal, the entire landscape becomes involved in interprofessional learning. It starts with creating awareness as to how IPC relates to clinical practice. There is plenty of research indicating the positive influence of IPC on the working environment, job satisfaction and improved patient care. 11 , 36 , 37 , 38 However, it is essential to create awareness within the interprofessional team about each other's roles, attitudes and expectations. By understanding how each silo organises itself in terms of power and tasks, junior doctors gain knowledgeability about other professions and learn how to navigate the LoHCP. In functional interprofessional teams, supervisors could address IPC during their regular debriefing sessions. However, in dysfunctional teams, external health professionals who are skilled in interprofessional collaboration could scaffold junior doctors' development into good collaborators. This external input could also help the team as a whole improve their collaboration process. 39

4.1.3. Fostering knowledgeability: Bridging the gap

With interprofessional learning as an integrative process and IPC as an explicit learning goal, the LoHCP becomes more prominent in junior doctors' transition, learning trajectories and future careers. In this scenario, junior doctors simultaneously develop two identities: their physician and their landscape identity. The landscape identity is an interprofessional identity, a complementary social identity to their professional physician identity. 40 Nurturing both identities is essential, as professional identity formation is conditional to interprofessional identity formation and can enhance IPC by creating a feeling of ‘unity’ and belonging. 41 If the doctor's professional identity develops in insolation inside CoPP, junior doctors risk centring their identity on being self‐sufficient and ‘in power’, culminating in loneliness and feeling ‘out’ of the group. Our study shows that this focus on the self can threaten interprofessional engagement, which prevents junior doctors from fitting in, making themselves useful and learning how to take advantage of the group. On the contrary, if the doctor's professional identity grows inside the LoHCP, across boundaries of communities, junior doctors will understand the team as a source of wisdom and guidance and realise that interprofessional engagement feeds professional autonomy and self‐realisation. 12 With junior doctors becoming effective members of the LoHCP, their ‘sense of belonging’ will be fuelled, creating a multimembership in different communities, where they are supported and see the interprofessional team as a tool to become more competent, both as a physician and as a collaborator. 14

4.1.4. Emotions, reflection, and transformative learning: Consciously shaping experiences

Our study shows that IPC is a highly emotional process and the same goes for being a beginning doctor. 2 , 4 The emotions aroused by interprofessional interactions and clinical practice itself shaped junior doctors' IPC experiences and, consequently, their ability to learn from these experiences. With good IPC outcomes, junior doctors' positive emotions limited the extent to which they reflected on their performance within the team. With negative IPC outcomes, junior doctors' strong negative emotions isolated them in a self‐centred rumination process that prevented them from learning from other team members. 42 , 43 By judging the value of a collaboration by its outcome, also called outcome bias, junior doctors made an inference regarding the collaboration only based on the outcome rather than evaluating the whole collaboration with all its information. 44 , 45

A curriculum focused on workplace learning should provide two types of formal reflective spaces for junior doctors: one space for discussing IPC independent of the clinical outcome being good or bad, to help junior doctors create the habit of reflecting on teamwork and awareness of how their perception of teamwork can be influenced by the context in which it takes place. The second space is necessary for junior doctors to reflect on the emotions aroused in practice. Directly after an emotional event, it is important that there is a safe space for all team members to share their emotions, which can enable support, validation and comfort and strengthen interpersonal relations. 46 By reflecting on their emotions, junior doctors learn to recognise their emotions, understand how emotions influence their behaviour and the group and, finally, modulate their emotions to optimise their performance and the collaboration process. 47 , 48 Interestingly, many participants expressed how drawing rich pictures and talking about their experiences helped them reflect on the depicted situations. Some of them experienced the space needed for reflection for the first time.

Special attention should be paid to junior doctors who experience bad treatment outcomes. In stressful situations where there is a lot at stake, the chances of the perceived outcome being bad are a lot higher, but it is in these situations that good IPC—and efficient collaboration—is especially important to ensure good patient care and sustainable professional relations.

4.2. Strengths, limitations and future research

This study uses a broad range of IPC experiences, with junior doctors varying in age, months of professional experience, specialism and nationality, which makes our findings more transferable than those of previous studies.

A strength in our methods is the parallel data analysis of the interviews and rich pictures, each informing the other and informing further data collection. In addition, during the whole analysis process, TSvD, MAdCF and MACV came together frequently for the aesthetic analysis, combining a senior supervisor perspective with a medical student perspective. This enabled an in‐depth shared understanding of the IPC experiences of junior doctors.

Our findings shed light on emotions junior doctors experienced during IPC, a relatively undiscovered area of research. One of the major strengths of this study is the use of rich pictures, which helped reveal intimate aspects of junior doctors' experiences. 49 The aesthetic value of the rich pictures complemented the words, 22 but in itself also provided information—especially what was or wasn't drawn in the pictures. An example is the details in which junior doctors could draw themselves, while leaving out details of others, as they connected more with themselves. The pictures stimulated reflective conversations, which in the end allowed for the themes to develop as they did.

This study has a small sample size and does not include any non‐northern European junior doctors, which might make the conclusions we draw less transferable. However, due to our data collection method, we did gather a large amount of rich data relevant to answering our study aim, using information power to guide our sample size. 26 Unfortunately, this study was impacted by the onset and further consequences of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Due to logistical difficulties, we were unable to include Swedish junior doctors, which would have provided a broader view on junior doctors' experiences of IPC. Interviews could not take place onsite and were conducted over Zoom. Although this provided practical advantages, such as bridging time and place limitations and allowing for flexible planning, some of the interpersonal interactions of a real face‐to‐face interview might have been lost. 50 , 51 To contribute to the generalizability of this study, all interviews were conducted in English, which meant that both researchers and participants had to communicate in their second language, which might have caused nuances to be missed. 52 The possible meanings lost in translation were however balanced out by the use of rich pictures, surpassing translation, enabling findings that were truly reflective of the participants.

The perspective of the nurses—the most frequently depicted health professionals—is lacking from this study. Neither were any nurses or other members of the interprofessional teams involved in data analysis, which is a major limitation. Future studies should include the experiences of nurses and other interprofessional team members, both junior and senior, preferably by letting them draw a rich picture of the same collaboration the junior doctor depicted. In addition, further studies should include different health care professionals in the data analysis.

We used the variety of IPC experiences to make our findings more transferable, but in doing so, we did not focus on differences between junior doctors, for instance, by comparing nationalities, gender or different specialisms. As a consequence of our purposeful sampling, there might be a participant bias, as all junior doctors volunteered to participate. That said, for this research, participants were required that were keen on sharing their experiences and were open to reflect on themselves and their experiences.

5. CONCLUSIONS

During their transition to clinical practice, junior doctors entre both the CoPP and the LoHCP. In both the CoPP and the LoHCP, IPC is key to facilitate membership and personal and professional development. Currently, junior doctors become foremost members of the CoPP and shape their professional identity based on perceived values in their physician community, receiving only explicit professional feedback regarding their physician competence. Interprofessional learning, however, occurs implicitly, with indirect feedback and no input from the interprofessional team. This leaves junior doctors wandering the LoHCP without understanding roles, attitudes and expectations of others. To help junior doctors become effective members of the LoHCP and navigate overlapping and bordering communities, an interprofessional approach to IPC is necessary. Therefore, IPC needs to become an explicit learning goal, and the whole interprofessional team needs to be empowered and trained as feedback givers. Through interactions with others at the intersections of communities, junior doctors develop knowledgeability, which enables them to bridge the gaps that exist due to professional/cultural silos. In addition, the workplace needs to provide a safe environment to embrace and reflect on emotions aroused by interprofessional interactions and clinical practice.

FUNDING INFORMATION

There are no funders to report for this submission.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have directly participated in the conception and writing of the manuscript and have approved the final version for publication.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was obtained from the Dutch association of Medical Education (NVMO, file 2019.3.8), the Ethics Committee Gent (file 2019/1389), the Ethics Committee University Medical Center Göttingen (file 11/10/19) and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (file 2019–05379).

Supporting information

Appendix 1. Instructions for the drawing of a rich picture.

Appendix 2. Description interview structure.

Appendix 3. Evolution of thematic map.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Tineke Bouwkamp‐Timmer for her editorial help and everyone connected to the U4 network for their input along the way. The authors also want to acknowledge all junior doctors that participated, for opening up and sharing their IPC experiences.

van Duin TS, de Carvalho Filho MA, Pype PF, et al. Junior doctors' experiences with interprofessional collaboration: Wandering the landscape. Med Educ. 2022;56(4):418-431. doi: 10.1111/medu.14711

REFERENCES

- 1. Sturman N, Tan Z, Turner J. “A steep learning curve”: Junior doctor perspectives on the transition from medical student to the health‐care workplace. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0931-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brennan N, Corrigan O, Allard J, et al. The transition from medical student to junior doctor: today's experiences of Tomorrow's Doctors. Med Educ. 2010;44(5):449‐458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Teunissen PW, Westerman M. Junior doctors caught in the clash: the transition from learning to working explored. Med Educ. 2011;45(10):968‐970. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang LY, Eliasz KL, Cacciatore DT, Winkel AF. The transition from medical student to resident: a qualitative study of new residents' perspectives. Acad Med. 2020;95(9):1421‐1427. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kilminster S, Zukas M, Quinton N, Roberts T. Preparedness is not enough: understanding transitions as critically intensive learning periods. Med Educ. 2011;45(10):1006‐1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04048.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tallentire VR, Smith SE, Skinner J, Cameron HS. Understanding the behaviour of newly qualified doctors in acute care contexts. Med Educ. 2011;45(10):995‐1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04024.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Lasson L, Just E, Stegeager N, Malling B. Professional identity formation in the transition from medical school to working life: a qualitative study of group‐coaching courses for junior doctors. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):165 doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0684-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kennedy TJT, Regehr G, Baker GR, Lingard LA. “It's a cultural expectation …” The pressure on medical trainees to work independently in clinical practice. Med Educ. 2009;43(7):645‐653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Green BN, Johnson CD. Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: working together for a better future. J Chiropr Educ. 2015;29(1):1‐10. doi: 10.7899/JCE-14-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet (London, England). 2010;376(9756):1923‐1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gilbert JHV, Yan J, Hoffman SJ. A WHO report: framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Allied Health. 2010;39(Suppl 1):196‐197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stalmeijer RE, Varpio L. The wolf you feed: challenging intraprofessional workplace‐based education norms. Med Educ. 2021;55(8):894‐902. doi: 10.1111/medu.14520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wenger‐Trayner E, Fenton‐O'Creevy M, Hutchinson S, Kubiak CW‐TB. Learning in Landscapes of Practice: Boundaries, Identity and Knowledgeability in Practice‐Based Learning. London: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hodson N. Landscapes of practice in medical education. Med Educ. 2020;54(6):504‐509. doi: 10.1111/medu.14061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hall P. Interprofessional teamwork: professional cultures as barriers. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):188‐196. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weller JM, Barrow M, Gasquoine S. Interprofessional collaboration among junior doctors and nurses in the hospital setting. Med Educ. 2011;45(5):478‐487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03919.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tang CJ, Zhou WT, Chan SW‐C, Liaw SY. Interprofessional collaboration between junior doctors and nurses in the general ward setting: a qualitative exploratory study. J Nurs Manag. 2018;26(1):11‐18. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Olde Bekkink M, Farrell SE, Takayesu JK. Interprofessional communication in the emergency department: residents' perceptions and implications for medical education. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:262‐270. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5bb5.c111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burford B, Morrow G, Morrison J, et al. Newly qualified doctors' perceptions of informal learning from nurses: implications for interprofessional education and practice. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(5):394‐400. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.783558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gottlieb M, Chung A, Battaglioli N, Sebok‐Syer SS, Kalantari A. Impostor syndrome among physicians and physicians in training: A scoping review. Med Educ. 2020;54(2):116‐124. doi: 10.1111/medu.13956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Armson R. Growing Wings on the Way: Systems Thinking for Messy Situations. Axminster, UK: Triachy Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cristancho S. Eye opener: exploring complexity using rich pictures. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4(3):138‐141. doi: 10.1007/s40037-015-0187-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cristancho SM, Helmich E. Rich pictures: a companion method for qualitative research in medical education. Med Educ. 2019;53(9):916‐924. doi: 10.1111/medu.13890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burnard P. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Nurse Res. 2006;13(4):84. doi: 10.7748/nr.13.4.84.s4 27702218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Watling CJ, Lingard L. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 70. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):850‐861. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.704439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753‐1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Varpio L, Paradis E, Uijtdehaage S, Young M. The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Acad Med. 2020;95(7):989‐994. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bell S, Morse S. How people use rich pictures to help them think and act. Syst Pract Action Res. 2013;26(4):331‐348. doi: 10.1007/s11213-012-9236-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Schaik SM, O'Sullivan PS, Eva KW, Irby DM, Regehr G. Does source matter? Nurses' and physicians' perceptions of interprofessional feedback. Med Educ. 2016;50(2):181‐188. doi: 10.1111/medu.12850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miles A, Ginsburg S, Sibbald M, Tavares W, Watling C, Stroud L. Feedback from health professionals in postgraduate medical education: Influence of interprofessional relationship, identity and power. Med Educ. 2021;55(4):518‐529. doi: 10.1111/medu.14426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wood L, Hassell A, Whitehouse A, Bullock A, Wall D. A literature review of multi‐source feedback systems within and without health services, leading to 10 tips for their successful design. Med Teach. 2006;28(7):e185‐e191. doi: 10.1080/01421590600834286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sargeant J, Mann K, Sinclair D, van der Vleuten C, Metsemakers J. Challenges in multisource feedback: intended and unintended outcomes. Med Educ. 2007;41(6):583‐591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02769.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shute VJ. Focus on formative feedback. Rev Educ Res. 2008;78(1):153‐189. doi: 10.3102/0034654307313795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eva KW, Armson H, Holmboe E, et al. Factors influencing responsiveness to feedback: on the interplay between fear, confidence, and reasoning processes. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17(1):15‐26. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9290-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Donnon T, al Ansari A, al Alawi S, Violato C. The reliability, validity, and feasibility of multisource feedback physician assessment: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2014;89(3) https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2014/03000/The_Reliability,_Validity,_and_Feasibility_of.34.aspx:511‐516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zwarenstein M, Reeves S, Perrier L. Effectiveness of pre‐licensure interprofessional education and post‐licensure collaborative interventions. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):148‐165. doi: 10.1080/13561820500082800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice‐based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD000072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reeves S, Lewin S, Espin S, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional Teamwork in Health and Social Care. Wiley‐Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Valentine MA, Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Measuring teamwork in health care settings: a review of survey instruments. Med Care. 2015;53(4):e16‐e30. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827feef6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reinders JJ, Lycklama À, Nijeholt M, van der Schans CP, Krijnen WP. The development and psychometric evaluation of an interprofessional identity measure: Extended Professional Identity Scale (EPIS). J Interprof Care. February 2020;1‐13. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1713064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reinders JJ. Task shifting, interprofessional collaboration and education in oral health care. 2018.

- 42. Fraser K, Ma I, Teteris E, Baxter H, Wright B, McLaughlin K. Emotion, cognitive load and learning outcomes during simulation training. Med Educ. 2012;46(11):1055‐1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04355.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hawkins N, Younan H‐C, Fyfe M, Parekh R, McKeown A. Exploring why medical students still feel underprepared for clinical practice: a qualitative analysis of an authentic on‐call simulation. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):165. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02605-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Allison ST, Mackie DM, Messick DM. Outcome biases in social perception: implications for dispositional inference, attitude change, stereotyping, and social behavior. In: Zanna MP, ed. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 28. Academic Press; 1996:53‐93 doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60236-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Baron J, Hershey JC. Outcome bias in decision evaluation. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1988;54(4):569‐579. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.4.569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nils F, Rimé B. Beyond the myth of venting: social sharing modes determine the benefits of emotional disclosure. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2012;42(6):672‐681. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1880 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology. 2002;39(3):281‐291. doi: 10.1017/s0048577201393198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shapiro J. The feeling physician: educating the emotions in medical training. Eur J Pers Centered Healthc. 2013;1(2):310‐316. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Helmich E, Diachun L, Joseph R, et al. “Oh my God, I can't handle this!”: trainees' emotional responses to complex situations. Med Educ. 2018;52(2):206‐215. doi: 10.1111/medu.13472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hanna P. Using internet technologies (such as Skype) as a research medium: a research note. Qual Res. 2012;12(2):239‐242. doi: 10.1177/1468794111426607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Janghorban R, Roudsari R, Taghipour A. Skype interviewing: the new generation of online synchronous interview in qualitative research. Int J Qual Stud Health Well‐Being. 2014;9(1):24152. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v9.24152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Helmich E, Cristancho S, Diachun L, Lingard L. ‘How would you call this in English?’: Being reflective about translations in international, cross‐cultural qualitative research. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6(2):127‐132. doi: 10.1007/s40037-017-0329-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Instructions for the drawing of a rich picture.

Appendix 2. Description interview structure.

Appendix 3. Evolution of thematic map.