Abstract

Background

Hand eczema (HE) has a significant impact on patients’ quality of life and work‐related activities. However, little is known about the patients' perspectives on quality of care for HE.

Objectives

To evaluate the patient perspective of the HE care process in a tertiary referral center.

Methods

Qualitative, semi‐structured focus groups were carried out, recorded, transcribed, and analysed using an inductive‐deductive thematic approach.

Results

Fifteen patients participated in four focus groups. Time and attention, together with being listened to and understood by the health care professional, were the most important aspects of care for HE mentioned by participants. Other aspects of care that were regarded as important were that diagnoses, causes and follow‐up of HE were not always clear to the participant; more psychosocial support was needed, and that participants experienced frequent changes in doctors. Information provided by nurses was valuable, but more individualized advice was needed.

Conclusions

To better meet the needs of patients, more explanation should be given about the causes of HE and the final diagnosis. Besides focusing on the treatment, it is also important to focus on its impact on the patient and options for psychosocial and peer support should be discussed. Furthermore, the beneficial role of the specialized nurse as part of integrated care was emphasized.

Keywords: focus groups, hand dermatitis, hand eczema, patient‐caregiver communication, psychosocial care, qualitative research, quality of care

Time and attention, together with being listened to and being understood, were the most important aspects of care mentioned by patients.

It is extremely important to focus on the impact of having chronic hand eczema (CHE), and options for psychosocial and peer support should be discussed.

A specialised nurse is of added value as part of integrated care in patients with CHE.

1. INTRODUCTION

Hand eczema (HE) is a common inflammatory skin disease, with a 1‐year prevalence of up to 10% in the general population. 1 This condition, often chronic (CHE), has a profound impact on patients, significantly affecting their quality of life and causing functional impairment in their work and daily activities. 2 For patients in whom CHE exposure to irritants or a contact allergy play a role, education and individual counseling have been found to have a positive effect on the severity of their disease and/or their quality of life. 3 Moreover, it appears that patients who are more satisfied with the care they are receiving are generally more inclined to follow treatment instructions. 4 These findings underline the importance of the content and quality of care for patients with CHE. Some previous qualitative studies briefly included the patients' perspective on quality of care. 5 , 6 , 7 However, no study has focused specifically on CHE and the patients' perspectives on quality of their care in a tertiary referral center.

Qualitative research provides a comprehensive understanding of patients' experiences regarding the health care provided. It is an appropriate method to examine understanding, attitudes and views of participants and allow individuals to describe their experiences. It can provide rich, explanatory data and the opportunity to explore factors specifically pertinent to the patient. Qualitatively research can provide useful insights into the key aspects and most important themes of the specific topic as well as act as a preliminary investigation to further quantitative research, 8 particularly in areas that have received little previous investigation.

Understanding of the perspectives of the patient on the quality of care could lead to improvements in health care to better meet their needs. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to explore patients' perspectives and experiences regarding the health care provided for their CHE at the outpatient clinic of the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG), a tertiary referral hospital in the northern part of the Netherlands.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Design

To explore patients' perspectives and experiences regarding the health care provided for their CHE, a qualitative design using focus groups was chosen. 9 The focus group design was chosen because of the ability of group interaction to generate data. In focus groups, participants are encouraged to talk to each other by asking questions, exchanging anecdotes, and commenting on each other's experiences. It was hypothesized that participants would be able to help each other to explore and clarify their views to a greater extent than in a one‐to‐one interview. We also hypothesized that the group interaction would reveal more unexpected dimensions and topics of interest compared to one‐to‐one sessions. In addition, in cases of different opinions on the same theme/topic, participants could interact with each other to provide more insight into the underlying cause of the difference. We selected eligible participants from among our current patients. To avoid selection bias, potential participants were recruited by a researcher who was not directly involved in the patients' health care. Only patients who had been diagnosed with CHE (at least one episode for more than 3 months, or two or more episodes in 1 year), 10 who have completed their diagnostic phase and receive(d) follow‐up appointments at the UMCG (whereby the diagnostic phase had been completed at least 3 months previously), and who had been following their current therapy for at least 3 months were considered eligible. As CHE is often a heterogeneous skin disease, patients were selected purposively using a maximum variation strategy, with maximum variation in age, sex, referrer, treatment, level of education, and severity of HE among the participants in the focus groups. 11 The average severity of CHE over the past 3 months was assessed by the participants, using the validated photographic guide for self‐assessment: almost clear, moderate, severe, or very severe. 12 , 13 Nineteen adults with CHE fulfilled the a priori determined eligibility criteria regarding diversity and variety, and 15 were willing to participate in the interview. Based on treatment (topical/systemic) and availability, we divided the participants into four focus groups: one group using only topical treatment, two groups receiving only systemic treatment, and one mixed group. Group size ranged from three to five participants. Between July and October 2020, we held four semi‐structured focus groups at the outpatient clinic of the UMCG Department of Dermatology. Because of the COVID‐19 policy that was introduced during this study, the last focus group took place online.

The interviews were conducted by a facilitator experienced in running focus groups, employed by the UMCG to evaluate and improve health care through patient participation. The facilitator was not involved in patient health care. A physician, not directly involved in the care of the participants with CHE, was present during the interviews to explain, where necessary, aspects related to care. The physician had no active role in performing the interviews. Besides the facilitator and the independent physician, each focus group included three to five participants with CHE. The study was approved by the local Medical Ethical Review Board (METC; reference number: 202000229), and all participants gave written informed consent.

2.2. Data collection

During the focus groups participants were asked to describe their experiences and perspectives regarding different aspects of care received for their CHE, based on questions in the topic guide (Table S1). The topic guide was created to cover important domains based on existing literature and expert opinion. To prepare the topic guide, the recommendations of the guidelines, as published by the guidelines development group of the European Society of contact dermatitis, for diagnoses, prevention, and treatment of hand eczema were used, 14 together with a conceptual model of CHE. 15 The conceptual model of CHE was based on a literature search and qualitative interviews with patients and expert dermatologists and includes core signs, symptoms, and impact of CHE. Several aspects of the conceptual model can serve as indicators of quality of care. Part of this model was used to create the topic guide (especially the part on the impact of CHE). 15 In addition, relevant parts of a previous qualitative study in patients with CHE by Mollerup et al investigating the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour in daily life of patients with CHE, were used. 5 For topics based on expert opinion, a dermatologist with expertise in the field of CHE and a member of the eczema patient association were interviewed. At our outpatient clinic, a specialized nurse plays an important role in the standard care of patients with HE, by providing information, guidance, and help with self‐management. 16 In order to be able to evaluate this aspect of care, questions evaluating the care provided by a nurse were included in the topic list. The topic guide contained several subtopics with, mostly, open‐ended questions about the diagnostic phase, communication, information and follow‐up, and questions regarding improvement of care. Besides the questions in the topic list, further open‐ended questions were asked to clarify answers and to obtain more information. Examples of questions that have been asked are: “How would you describe that to yourself?” and “What experience do you have with that specific part of care?”. During the interviews participants were often encouraged to elaborate and clarify their answers. Each focus group lasted approximately 2 hours.

2.3. Analysis

We audio‐recorded and transcribed all interviews verbatim. All data, including individual traceable excerpts, were pseudonymized. Two authors (MMS and FMR) independently coded the text in ATLAS.ti, version 8.4.5. 17 To further analyse the data, a thematic approach was chosen. One of the key advantages of a thematic analysis is its flexibility and ability to incorporate both an inductive and deductive approach, which was very suited to the aim of the current study. The inductive approach made it possible to move from observation to hypothesis, to approach the best possible reflection of the patients' perspective without prior assumptions. This gave the opportunity to include codes and themes not initially included in the topic list during analysis. The deductive approach ensured that the analysis included results on predefined topics considered important based on previous literature and expert opinion. 18 , 19 All individual codes were grouped in themes. After analysing all focus groups, the two authors discussed their code and theme lists to achieve consensus regarding interpretation of the findings. These discussions did not elicit new themes, but some codes were moved between themes. After the fourth focus group, no new codes and/or themes emerged during analysis and data saturation was reached.

3. RESULTS

During the interviews free conversation and expression took place between the participants and between participants and the facilitator. Each participant contributed substantially and significantly, although the extent of their contributions varied (see Table 1 for patient characteristics). The analysis generated five key themes: diagnostic phase, providing information, patient–professional communication, psychosocial support, and treatment and follow‐up (see Table 2). All patients' quotes were translated into English by a native English‐speaking editor. For specific quotes related to each theme see Table S2.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participants with chronic hand eczema participating in focus groups

| Male (n = 7) | Female (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| <45 | 3 | 2 |

| ≥45 | 4 | 6 |

| Treatment a | ||

| Topical only | 2 | 5 |

| Systemic | 5 | 3 |

| Referral | ||

| Dermatologist | 6 | 3 |

| Occupational related b | 0 | 2 |

| General practitioner | 1 | 3 |

| Education level c | ||

| Low (level 0‐2) | 0 | 1 |

| Medium (level 3‐4) | 4 | 5 |

| High (level 5‐8) | 3 | 2 |

| Session | ||

| Live | 5 | 5 |

| Digital | 2 | 3 |

| Hand eczema severity d | ||

| Almost Clear | 1 | 3 |

| Moderate | 1 | 3 |

| Severe | 4 | 1 |

| Very severe | 1 | 1 |

Topical treatment included topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and coal tar. Systemic treatment included alitretinoin, ciclosporin, dupilumab, and acitretin.

Referrals from different health care providers, but all occupational related.

Distinctions in education were based on the International Standard Classification of Education 2011 classification. 20

TABLE 2.

The defined key themes with associated categories and codes

| Key theme | Category | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic phase | Patch test | Experience with patch test |

| Patch test | Homework after patch testing | |

| Patch test | No allergens found | |

| Diagnosis of hand eczema | Diagnosis unclear | |

| Diagnosis of hand eczema | Attention to causes of hand eczema | |

| Providing information | Written and oral information | Satisfied with provided information |

| Information by nurse | Added value | |

| Information by nurse | Adapt to patient's need for information | |

| Practical advice | Need for practical advice | |

| Practical advice | Attention to consequences of corona policy | |

| UMCG app | Good experiences with app when patients have flare up | |

| Patient‐professional communication | Time and attention | Satisfied with doctor's listening to patient |

| Several doctors | Keep telling the story | |

| Several doctors | Shared decision‐making depends on doctor | |

| Several doctors | Advantage of several doctors | |

| Peer‐to‐peer health communication | Satisfied with communication between health care providers | |

| Shared decision‐making | The degree of shared decision‐making depends on the physician | |

| Shared decision‐making | Expertise of the physician versus own expertise | |

| Shared decision‐making | Concerns about how choices are made | |

| Psychosocial support | Psychosocial care | No need for psychosocial care |

| Psychosocial care | More focus needed on the impact of hand eczema | |

| Psychosocial care | The importance of psychosocial care | |

| Contact with other patients | Recognition | |

| Contact with other patients | Learn from each other | |

| Contact with other patients | No awareness of existence of patient association | |

| Individual approach | Lack of individual approach | |

| Individual approach | Improving individual approach | |

| Treatment and follow‐up | Treatment | Step‐down approach based on own experiences |

| Treatment | Fear of topical steroids | |

| Treatment | Flare up when reducing systemic medication | |

| Treatment | Concerns about consequences of systemic treatment for their body | |

| Accessible contact | Easy contact in event of a flare up | |

| Contact person | Umbrella function | |

| Contact person | Point of contact to share what you encounter in daily life with regard to hand eczema |

Abbreviations: UMCG, University Medical Center Groningen.

3.1. Diagnostic phase

3.1.1. Referral

Almost all participants indicated that they had been able to visit the clinic soon after referral by a general practitioner, occupational physician, or another dermatologist.

3.1.2. Patch testing

The information provided for the patch test procedure, both written and oral, was perceived as clear. However, opinions about the patch test itself were diverse. Six of the 15 participants described the test as unpleasant, with itching and not being able to shower as the most commonly mentioned complaints. One participant suggested dividing the patch test into several sessions, with smaller surfaces covered. After a positive test result, most participants described the explanation they had received by the dermatologist about positive contact allergies as clear and the supportive, written information as practical. A few participants expressed the view that avoiding the products, based on their test results, required time and effort, partly because of the many synonyms mentioned on the product labels. One participant indicated the importance of physicians' advice on how possibly to avoid work‐related allergens while continuing in the same profession. A few participants expressed frustration that no contact allergies were found, or that symptoms were not resolved after avoiding sources of allergens.

3.1.3. Diagnosis of hand eczema

Three participants were uncertain about their diagnosis. One of those participants indicated that the eczema always presents itself differently and had never asked about the cause. Another participant indicated that he had asked about this, but that the doctors could not give an exact answer. Two participants mentioned that it would be valuable to pay specific attention and increase the focus in the diagnostic phase to the different causes of HE.

3.2. Providing information

3.2.1. Written and oral information

In general, the participants were satisfied with both the oral and written information provided. For example, participants mentioned the clear information about the patch test procedure and clear instructions on how to apply topical medication. Furthermore, they mentioned that important key aspects were covered during consultations and detailed written information was provided to be read carefully at home.

3.2.2. Information and guidance by the nurse

Half the participants reported that they had not received a consultation or information from a specialized nurse, or that they could not remember it. The participants who recalled a consultation with the nurse had received information individually; only one had received it in a group with others. They indicated that the information about HE was of added value. But some participants expressed that there were opportunities for improvement (see Practical advice below).

3.2.3. Practical advice

A few participants reported a greater need for practical advice, which they would like to receive, for example, from a nurse. Examples included advice on how to organize their life to minimize the impact of CHE on daily activities, and how to reduce exposure to irritants and allergens. A subject of specific interest was how to deal with CHE in combination with the recommended COVID‐19 hand hygiene measures, as they might contradict standard advice of avoiding exposure to water and irritants. Although advice regarding reducing exposure, where mentioned, was valuable, a need for advice tailored to individual preferences of the participants, rather than required measures, was mentioned. Also, the need to discuss the use of specific skin products (eg during bathing and showering) was suggested by the participants.

3.2.4. Access to care via eHealth

Also discussed was the ability of participants to access health records online (website/App), including, among other things, their appointments and results of examinations. Participants reported good experiences with the App and used it to view test results, which were quickly visible. The App was also used to reschedule appointments in case of a flare‐up of their CHE.

3.3. Patient‐professional communication

3.3.1. Time and attention

Twelve participants expressed having been given sufficient time and attention during visits. They also indicated that this, together with being listened to and understood by the health care professional, was one of the most important aspects of care for CHE. Participants described physicians as very dedicated, prompt to call as soon as results were known, and pro‐active in looking for substitutions when medications were not available because of supply shortages.

3.3.2. Different physicians

Almost all participants mentioned having had consultations with different physicians, making it necessary to retell their story repeatedly. Participants also noted differences in the way the physicians communicated. Some allowed more time for shared decision‐making; others took more time for education during visits; and others were more empathetic. Two participants reported that they had received conflicting advice from physicians. Several indicated that seeing fewer different physicians during visits would be an improvement. Although four participants also understood that in a teaching hospital, seeing different physicians is unavoidable. Also, most participants expressed a preference for a particular physician. On the other hand, one participant mentioned that seeing different physicians could be an advantage, as another physician might have a different view.

3.3.3. Communication between health care providers

During the focus groups, various opinions emerged regarding communication between their health care providers. Some participants found it annoying when, in their presence, a resident in dermatology discussed their condition with the supervisor. This made them feel that the consultation was about, and not with, them. Others, however, felt that such consultations led to better treatment. Communication between dermatologists and specialists outside dermatology was experienced as positive. For example, in case of deviating lab values for a participant on systemic therapy, contact with a specialist would be sought and his/her advice taken into consideration. However, concerning contact between the general practitioner (GP) and the dermatologist, a few participants indicated that the GP was not well informed because letters had not been regularly sent. Others were not sure whether the GP had been properly informed.

3.3.4. Shared decision‐making

In general, participants experienced enough opportunity for shared decision‐making. However, there was considerable variety in how far shared decisions could be taken. According to the participants, shared decisions depended on the capability of the physician and on their own empowerment. One participant noted that decisions regarding treatment were made in an advisory manner.

3.4. Psychosocial support

3.4.1. Psychosocial care

Eleven participants mentioned the significant impact of CHE on their daily life and social activities. A few participants indicated that they had considered ending their life because of the burden of having CHE and its impact on their quality of life. Although most participants emphasized the value of psychosocial care; they felt that consideration of this aspect of care could have been greater. However, a few participants indicated needing psychosocial care only in cases of severe flare‐ups of their CHE. Participants felt that physicians were more focused on the treatment of CHE than on its impact. On the other hand, a few participants did not consider it the task of the dermatological physician to provide on counsel these psychosocial aspects; instead, the possibilities for this specific kind of care should be given with a referral, if needed. Some could conceive a greater role for a specialized nurse in psychosocial aspects. In addition, online discussion groups, patient associations, and psychiatrists were mentioned.

3.4.2. Contact with other patients

Contact with other patients, as in the form of a support group, was mentioned as important in psychosocial support. A large number of participants were not aware that a patient association for patients with (hand) eczema existed and had not been informed of this during their visits. They indicated that they would have liked to receive such information.

3.4.3. Individual approach

Participants considered it important for those giving care to look at the individual patient, because they believed every patient and every case of CHE was different. The physician should realize that there is a difference between practice and theory, and not everything is applicable to every CHE case. They also mentioned that it is important for dermatologists to be cognizant of the way they convey their message(s) to patients and of its subsequent impact.

3.5. Treatment and follow‐up

3.5.1. Treatment

Participants mentioned experiencing treatment of their CHE as a search for the most beneficial treatment. Some participants had a clear idea of how continuation of the treatment would be, but others indicated having uncertainties about follow‐up. Experiences with topical corticosteroids (TCS) varied. One participant mentioned being afraid of the amount of steroids entering the body when using TCS. A few participants said they did not use the TCS in a standard step‐down approach but used their own experience as to when and how to apply them. Another mentioned the added value of clear guidance by the doctor regarding reduction of TCS application towards a maintenance schedule.

On systemic treatment, a few participants found it a disadvantage that medication at some point had to be reduced, resulting in a flare‐up of the CHE. A few participants mentioned that it was not always clear to them how choices were made regarding various systemic treatments for their CHE and which considerations were taken into account. One participant indicated that, before making a choice, he would have liked a transparent explanation of the likelihood of a treatment's effectiveness.

3.5.2. Access to care when needed

Most participants found it important that the clinic was easy to contact in the event of flare‐ups, side‐effects, or questions. Participants expressed having contacted the clinic by phone or by using the online App. In their experience, an extra appointment could be quickly arranged in the event of a flare‐up.

3.5.3. Continuity of care

Several times participants expressed the need for a primary contact person. Some indicated a need for easy access to a professional when experiencing psychological problems; others mentioned the need to be able to talk about the impact of a treatment and to receive information and advice regarding questions. Two participants mentioned that a primary contact person would be particularly valuable when many physicians were involved. One participant suggested that the specialized nurse could act as a primary contact person to provide more continuity in care.

4. DISCUSSION

This qualitative study explored the experiences and perspectives of patients with CHE regarding their care in a tertiary center. It elicited various aspects of experiences with care that the participants identified as being important: the diagnostic phase, providing information, communication, psychosocial support, treatment, and follow‐up. Points for improvement were also mentioned. As yet, no similar, robust qualitative study on patients' perception of care of CHE has been published. Such qualitative research is essential to set standards regarding the care to be provided and to optimise it.

We identified one qualitative study in patients with CHE by Mollerup et al that investigated the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour in the daily life of patients with CHE using focus groups. 5 Although the focus of Mollerup et al's study was different, it had some convergence with the results of the current study. It reported that patients lacked knowledge, especially regarding the causes of eczema and experienced “trial‐and‐error” advice during medical consultations. In line with that study, we found that some participants did not know the cause of their HE and suggested that it would be valuable to give increased attention to the different causes of HE. In addition, several participants experienced the treatment of their CHE as a search for the most beneficial treatment. Mollerup et al also pointed to the need for a more personal approach, concluding that HE care should be more individualized, which is in line with our findings. 5 A second study qualitatively addressed the perception of illness in patients with occupational skin disease, of whom the majority had skin problems located on their hands. The patients' perspective of quality of care was also briefly included. Overlapping themes, such as psychological consequences and causes of the skin condition, were reported, but mostly not in relation to the quality of care. Regarding the reported perspectives of the quality of care, dissatisfaction with the doctor, the importance of the allergy tests, and unsatisfactory dermatological treatment attempts were mentioned by the participants of the interviews, which is partly in line with the current study. As the study focused specifically on occupational skin disease, rather than CHE in general, the results might be not completely generalizable to the current study. 6

A recently published systematic review examined qualitative studies exploring experiences of people with eczema in general (eg, atopic dermatitis). 7 The most important findings from this research were that information and advice were inadequate, the psychosocial impact was not recognized, and patients felt the need to know the underlying cause of their eczema. These findings are also in line with our study. In addition, our study found the following important insights: diagnoses were not always clear; more psychosocial support was needed; participants experienced frequent changes in physicians; information provided by nurses was valuable, but more practical and individualised advice was needed.

For some participants the cause of their HE was unclear. This can possibly be explained by the fact that the causes of HE are often multifactorial. To improve the diagnostic phase, it might be helpful to emphasize and extend the focus during the first appointment to the multifactorial causes of HE, the outline of the diagnostic phase, the limitations of diagnostic tests, the possible (multifactorial) diagnosis, and what the treatment of the HE–based on the diagnosis–may involve. After the diagnostic phase, another appointment should take place to discuss the results, the specific diagnosis, and the consequences thereof.

Our study showed that participants with CHE attach great importance to time, personal attention, and psychosocial support, given the serious impact of the disease on their lives. Some participants even indicated having had a suicidal thoughts because of their eczema. Even though CHE has been known to affect a person's quality of life, our findings again underline the importance of psychosocial support. 2 , 21 , 22 , 23 Other studies also point to the need for more attention to the psychosocial impact. 21 , 22 Our study showed that participants do not expect their treating physician or specialized nurse to provide such care, but they should rather suggest possible options for psychosocial support and refer the patient further, the simplest option being referral to a patient association for peer support.

Participants indicated that they saw many different physicians, thereby experiencing differences in communication, degrees of shared decision‐making, and empathy. In a university hospital this is unavoidable because of residents participating in different outpatient clinics, as several participants were aware of. However, to achieve more continuity in care, as suggested by the participants, a primary contact person would be a good option. Occasionally the specialized nurse was mentioned as suitable for this role.

Despite offering consultations with a nurse as standard part of care for every patient with HE, only half of the participants remembered consulting a nurse. Of the participants who remembered contact with a nurse, they indicated that although they regarded the information provided by the nurse as valuable, they expressed a greater need for individualized, practical advice. The satisfaction resulting from appointments with a nurse is supported by previous literature in which patients said that nurses paid more attention to practical advice about dealing with problems in daily life. 24

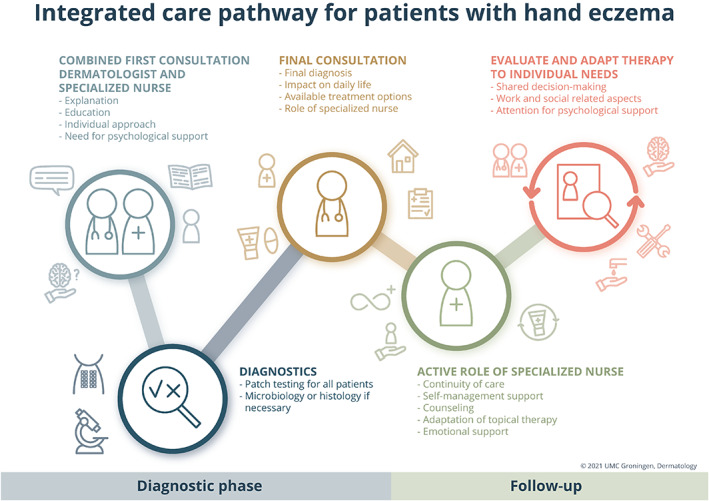

The effectiveness of integrated multidisciplinary care for patients with HE, including a dermatologist, nurse and an occupational physician, was investigated by van Gils et al. 25 , 26 During this study period, the nurse had the task of care manager and the patients visited a nurse several times for education. 25 The integrated care programme significantly improved clinical outcome measures, as compared with usual care. 26 Although previous literature points out the advantages of the role of a nurse in care for CHE, it appears it is yet to be fully integrated into daily practice. Our current research even more strongly underlines the added value of a specialized nurse, who can play a major role in integrated care by providing information, education, support, and coordination. A combined first consultation for every HE patient is recommended, with visiting the specialized nurse after the first appointment with the physician as a standard part of care. This allows extra time for education about the nature of the diagnoses as well as triggering factors, topical therapies, the use of various types of gloves, and individualized advice regarding avoidance of exposure to irritants and allergens. During follow‐up the specialized nurse could act as an approachable primary contact person for extra information, self‐management support, counselling, and emotional support. In addition, evaluation and adaptation of topical therapy (including TCS) and advice on individual needs is a major part of the role of the specialized nurse. Furthermore, the specialized nurse can act as an intermediary between the patient and physician during follow‐up. The integrated care pathway for patients with HE, with recommendations based on the patients' experiences reported in this study, is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Integrated care pathway for patients with hand eczema. Based on the patients' experiences mentioned during the focus groups

The main strength of the study is that it includes the different participants involved in the CHE care process: patient, dermatologist, specialized nurse, and facilitator. A patient with CHE (a member of the patient association for people with atopic dermatitis and who did not receive care for HE at the UMCG), was involved in compiling the topic list and interpreting the results. To reduce selection and information bias, none of the health care providers from the treatment team was involved in selecting the participants or was present during the focus groups.

This study also has limitations. Although focus groups have an advantage in terms of group interaction and the possibility of gaining insight into the cause of individual differences in experience, focus group norms may silence individual experiences. In addition, participants could feel a lack of confidentiality in the presence of fellow participants and/or the physician. Although, the physician was not directly involved in the care of the participants with CHE, and had no active role during the focus groups, her presence may potentially have led to the loss of some delicate or sensitive information. Last, it must be taken into account that this research focused on patients from a tertiary referral center. However, to increase generalizability we selected a heterogeneous group of participants with enough variation in CHE severity, referrers, educational level, age, and sex. In addition, the themes that emerged during analysis were not specifically unique to a tertiary setting but involved aspects of HE care in general. This makes the recommendations for practice also suitable for other health care professionals treating HE. For this research we chose an experienced, independent facilitator to encourage participants to share and discuss freely. However, due to her limited knowledge of HE specifically, sometimes she lacked the ability to ask follow‐up questions.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our study found that (1) the diagnosis of CHE was not always clear to every participant, (2) more psychosocial support is needed, (3) participants felt that they saw too many different physicians, (4) the role of nurses is of added value, (5) more practical and individualised advice is needed, with a single point of contact. Further research should include multicentre studies, also in non‐tertiary referral hospitals, to evaluate if the findings in the current study are generalizable to broader patient populations. Further studies could also investigate the improvement of care after the implementation of the recommendations for daily practice discussed in the current study, in which psychosocial support should be of particular concern.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Manon Sloot: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (lead); formal analysis (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (lead); visualization (lead); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (equal). Laura Loman: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (supporting); methodology (equal); supervision (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Geertruida L.E. Romeijn: Conceptualization (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Fieke Rosenberg: Formal analysis (equal); writing – review and editing (supporting). Bernd Arents: Conceptualization (supporting); supervision (supporting); writing – review and editing (lead). Marie Louise Anna Schuttelaar: Conceptualization (equal); supervision (lead); writing – review and editing (lead).

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Dr Marie L.A. Schuttelaar received consultancy fees from Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and is an advisory board member for Sanofi Genzyme, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, LEO Pharma, Lilly. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Table S1. List of topics used for each focus groups.

Table S2. Quotes related to themes from four focus groups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank all participants in the focus groups for their contribution.

Sloot MM, Loman L, Romeijn GLE, Rosenberg FM, Arents BWM, Schuttelaar MLA. Patients' perspectives on quality of care for chronic hand eczema: A qualitative study. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;86(3):204‐212. doi: 10.1111/cod.14020

Manon M. Sloot and Laura Loman contributed equally.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Supporting data are available on request. Please contact the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Quaade AS, Simonsen AB, Halling A‐S, Thyssen JP, Johansen JD. Prevalence, incidence, and severity of hand eczema in the general population: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84(6):361‐374. doi: 10.1111/cod.13804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fowler JF, Ghosh A, Sung J, et al. Impact of chronic hand dermatitis on quality of life, work productivity, activity impairment, and medical costs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(3):448‐457. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ibler KS, Jemec GBE, Diepgen TL, et al. Skin care education and individual counselling versus treatment as usual in healthcare workers with hand eczema: randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2012;345:e7822. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001570. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mollerup A, Johansen JD, Thing LF. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour in everyday life with chronic hand eczema: a qualitative study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(5):1056‐1065. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bathe A, Diepgen TL, Matterne U. Subjective illness perceptions in individuals with occupational skin disease: a qualitative investigation. Work. 2012;43(2):159‐169. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Teasdale E, Muller I, Sivyer K, et al. Views and experiences of managing eczema: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(4):627‐637. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(6996):42‐45. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311(7000):299‐302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Diepgen TL, Andersen KE, Chosidow O, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hand eczema – short version. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13(1):77‐84. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coyne IT. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs. 1997;26(3):623‐630. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-25-00999.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coenraads PJ, Van Der Walle H, Thestrup‐Pedersen K, et al. Construction and validation of a photographic guide for assessing severity of chronic hand dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(2):296‐301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hald M, Veien NK, Laurberg G, Johansen JD. Severity of hand eczema assessed by patients and dermatologist using a photographic guide. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(1):77‐80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07565.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Diepgen TL, Andersen KE, Chosidow O, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hand eczema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13(1):e1‐e22. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12510_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grant L, Seiding Larsen L, Burrows K, et al. Development of a conceptual model of chronic hand eczema (CHE) based on qualitative interviews with patients and expert dermatologists. Adv Ther. 2020;37(2):692‐706. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01164-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schuttelaar MLA, Vermeulen KM, Drukker N, Coenraads PJ. A randomized controlled trial in children with eczema: nurse practitioner vs. dermatologist. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(1):162‐170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hwang S. Utilizing qualitative data analysis software: a review of Atlas.ti. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2007;26(4):519‐527. doi: 10.1177/0894439307312485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237‐246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77‐101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. OECD/Eurostat/UNESCO Institute for Statistics . ISCED 2011 Operational Manual: Guidelines for Classifying National Education Programmes and Related Qualifications; OECD; 2015. doi: 10.1787/9789264228368-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Capucci S, Hahn‐Pedersen J, Vilsbøll A, Kragh N. Impact of atopic dermatitis and chronic hand eczema on quality of life compared with other chronic diseases. Dermatitis. 2020;31(3):178‐184. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marron SE, Tomas‐Aragones L, Navarro‐Lopez J, et al. The psychosocial burden of hand eczema: data from a European dermatological multicentre study. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78(6):406‐412. doi: 10.1111/cod.12973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Politiek K, Ofenloch RF, Angelino MJ, van den Hoed E, Schuttelaar MLA. Quality of life, treatment satisfaction, and adherence to treatment in patients with vesicular hand eczema: a cross‐sectional study. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;82(4):201‐210. doi: 10.1111/cod.13459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Courtenay M, Carey N. Nurse‐led care in dermatology: a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(1):1‐6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06979.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van Gils RF, van der Valk PGM, Bruynzeel D, et al. Integrated, multidisciplinary care for hand eczema: design of a randomized controlled trial and cost‐effectiveness study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):438. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Gils RF, Boot CRL, Knol DL, et al. The effectiveness of integrated care for patients with hand eczema: results of a randomized, controlled trial. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66(4):197‐204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.02024.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. List of topics used for each focus groups.

Table S2. Quotes related to themes from four focus groups.

Data Availability Statement

Supporting data are available on request. Please contact the corresponding author.