Abstract

Objective:

To determine the associations of pancreatobiliary maljunction (PBM) in the West.

Background:

PBM (anomalous union of common bile duct and pancreatic duct) is mostly regarded as an Asian-only disorder, with 200X risk of gallbladder cancer (GBc), attributed to reflux of pancreatic enzymes.

Methods:

Radiologic images of 840 patients in the US who underwent pancreatobiliary resections were reviewed for PBM and contrasted with 171 GBC cases from Japan.

Results:

Eight % of the US GBCs (24/300) had PBM (similar to Japan; 15/171, 8.8%), in addition to 1/42 bile duct carcinomas and 5/33 choledochal cysts. None of the 30 PBM cases from the US had been diagnosed as PBM in the original work-up. PBM was not found in other pancreatobiliary disorders. Clinicopathologic features of the 39 PBM-associated GBCs (US:24, Japan:15) were similar; however, comparison with non-PBM GBCs revealed that they occurred predominantly in females (F/M = 3); at younger (<50-year-old) age (21% vs 6.5% in non-PBM GBCs; P = 0.01); were uncommonly associated with gallstones (14% vs 58%; P < 0.001); had higher rate of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (69% vs 44%; P = 0.04); arose more often through adenoma-carcinoma sequence (31% vs 12%; P = 0.02); and had a higher proportion of nonconventional carcinomas (21% vs 7%; P = 0.03).

Conclusions:

PBM accounts for 8% of GBCs also in the West but is typically undiagnosed. PBM-GBCs tend to manifest in younger age and often through adenoma-carcinoma sequence, leading to unusual carcinoma types. If PBM is encountered, cholecystectomy and surveillance of bile ducts is warranted. PBM-associated GBCs offer an invaluable model for variant anatomy-induced chemical (reflux-related) carcinogenesis.

Keywords: anomalous, anomaly, bile duct, carcinogenesis, carcinoma, gallbladder, hyperplasia, junction, maljunction, reflux, union

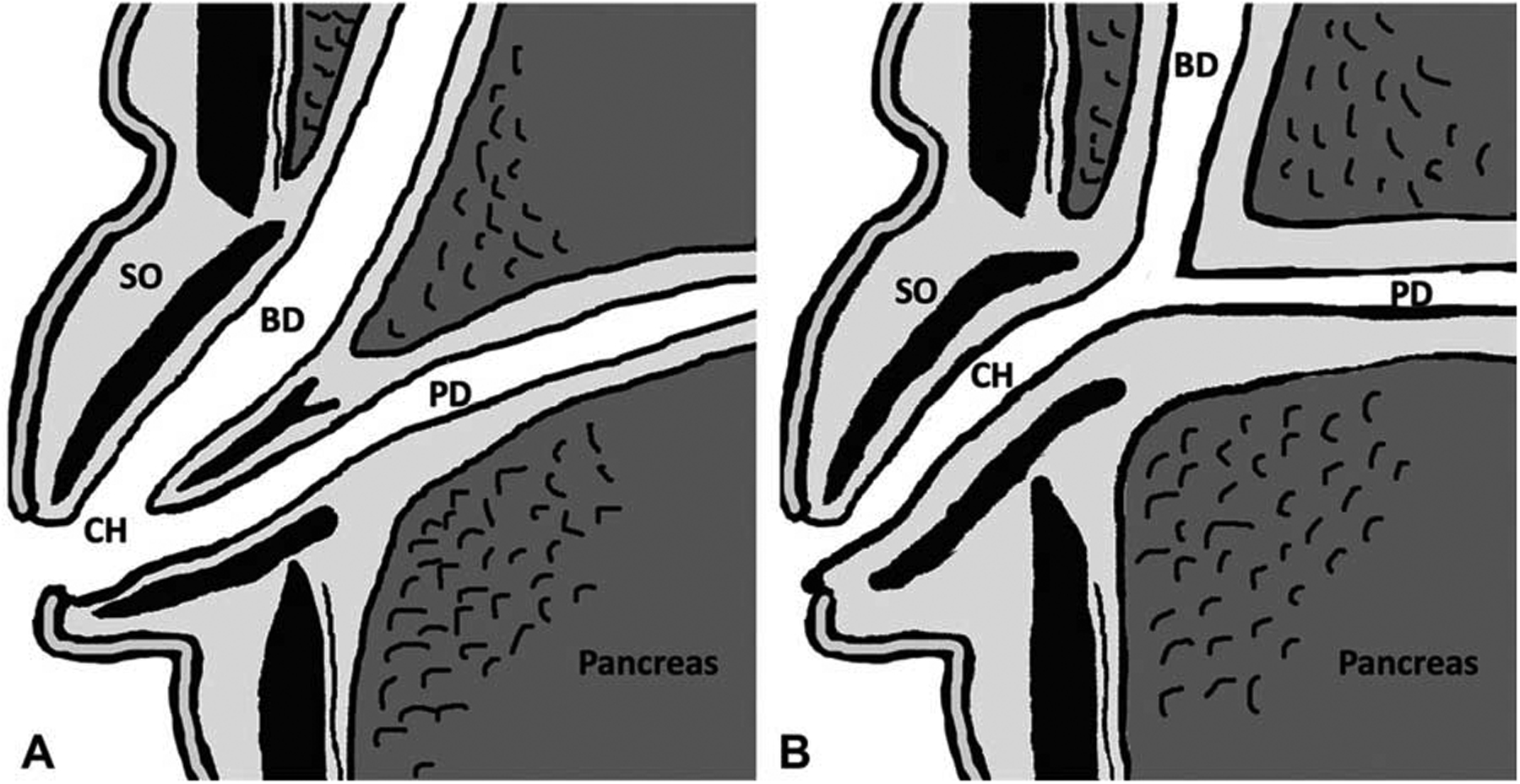

Pancreatobiliary maljunction (PBM), which is the “anomalous” union of the main pancreatic duct and the common bile duct in a supra-Oddi position instead of an intra-sphincteric merger (Figure 1), was first described in 1916,1 but became recognized in 1970 s in Japan as a significant disorder and a major risk factor for gallbladder cancer (GBC).2,3 This has led to the creation of the Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction (JSPBM), which collects nation-wide data and issues diagnostic criteria, with updates provided in 1987, 1994, and 2014.4–6 As a result, abdominal ultrasounds, which are routine component of healthcare check-up protocols in Japan, were modified to include a search for surrogate signs of PBM (such as mucosal thickening in the gallbladder). if PBM is verified with further analysis, cholecystectomy is recommended. As a result of this national awareness, substantial experience accumulated in the Far East regarding this relatively rare condition and its associations, which led to the realization that the overall incidence of biliary cancers is 200 times higher in patients with PBM than in the general Japanese population.7 The frequency of PBM in resected GBCs is reportedly 10% in Japan8 and is now being reported to be even higher in South Korea, which also screens for PBM.9 The carcinogenic effect of PBM has been shown to be due to reflux of pancreatic enzymes (unchecked by the Oddi) to the bile ducts and gallbladder, which has been confirmed by the detection of acinar enzymes in the gallbladder bile of these patients.10–12

FIGURE 1.

A schema of the junction between pancreatic and bile ducts. A: Normal junction. The junction between pancreatic and bile ducts is located in the duodenal wall. At the duodenal papilla, sphincter of Oddi surrounds the pancreaticobiliary junction, and regulates the flow of bile while preventing the reflux of pancreatic secretion into bile duct. B: Pancreatobiliary maljunction. The common channel is longer than normal, which abrogates the influence of the sphincter on the pancreatobiliary junction, allowing the reciprocal reflux of pancreatic secretion and bile. BD indicates bile duct;CH, common channel;PD, pancreatic duct; SO, sphincter of Oddi.

Although PBM is widely recognized in Asia9,13 and incorporated in healthcare screening protocols, the same cannot be said for the US, where PBM, with the exception of those associated with choledochal cysts,14,15 is still largely dismissed as an Asian disorder.16 However, data on the incidence and role in biliary carcinogenesis of PBMs that are unaccompanied by choledochal cysts (“nondilated” type) are highly limited in the Western hemisphere. It has been increasingly appreciated that the frequency of PBM in the US population may in fact be similar to that in Japan,17–21 about 1% of the population.

In this study, to determine the frequency and associations of PBM in the West, 840 patients who had undergone pancreatobiliary resections, including 300 consecutive GBCs, were investigated for PBM, and the findings were contrasted with 171 GBCs from Japan. The clinicopathologic characteristics of the PBM-associated GBCs identified were also subjected to detailed analysis.

METHODS

The study was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the Institutional Review Board.

Cases

Frequency Analysis

To determine the true frequency of PBM that accompanies GBC in the US, imaging studies performed on 300 consecutively resected GBCs, all with adequate imaging available, were carefully reviewed (T.M.). The radiologic studies available for PBM assessment for this purpose included direct cholangiopancreatography (N = 63), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (N = 143) and computed tomography (N = 94).

Additionally, 540 resections from the US, on whom adequate imaging was available, were analyzed (T.M.): 42 consecutive distal bile duct carcinomas (BDCs), 30 peri-hilar BDCs, 61 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas, 97 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs) (46 of the head and 51 of the body/tail), 88 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) (36 of the head and 52 of the body/tail), 46 noninvasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, 46 noninvasive mucinous cystic neoplasms, 33 prophylactic extrahepatic bile duct resections (with clinical diagnosis of choledochal cyst) and 97 routine cholecystectomies without neoplasms.

Separately, from Japan, 171 consecutive resected GBCs were analyzed (T.M.) for PBM along with 47 prophylactic cholecystectomies (24 including bile duct resections) performed on patients with PBM diagnosed during routine testing.

Clinicopathologic Analysis of PBM-Associated GBCs

Overall, 39 resected PBM-associated GBCs (24 from the US and 15 from Japan) with adequate pathological material available for analysis were identified. For the detailed comparative analysis (V.A., B.M., and B.P.) of this group with GBCs without PBM for parameters such as types of inflammation, 43 cases of from the US and 30 from Japan were randomly selected.

Definition of PBM

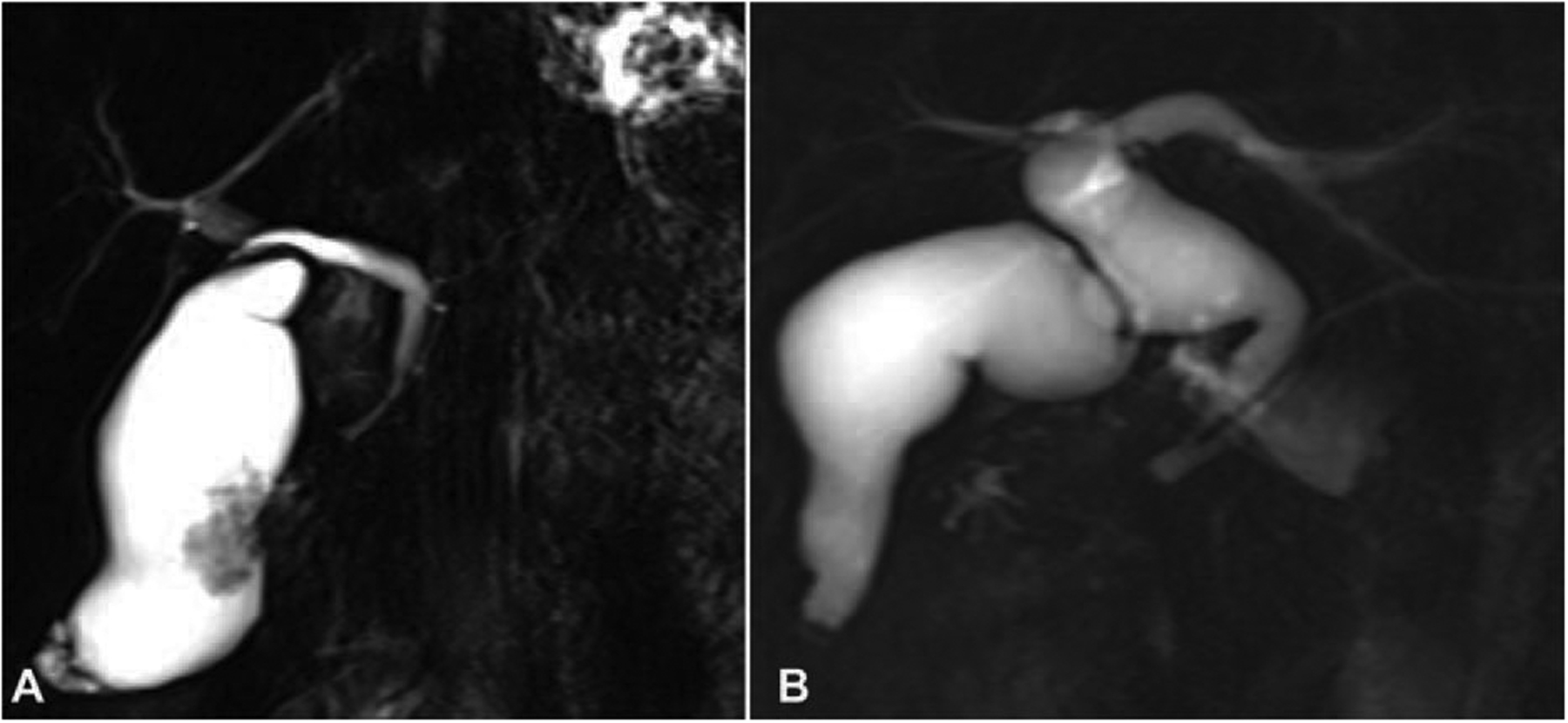

In this study, PBM was defined using the criteria put forth in 2013 by the JSPBM as (A) maljunction/malunion of the main pancreatic duct and common bile duct (determined by direct cholangiography) outside the Oddi sphincter (and its influence), or, (B) anatomically situated outside the duodenal wall on MRI and/or computed tomography6,10,22–25 (Figure 2). Because in cases with a relatively short common channel, it is necessary to confirm by direct cholangiography that the effect of the sphincter of Oddi does not extend to the junction,6,26 cases that were indeterminate for this feature (N = 423) were excluded from this study.22–25,27–30 Cases indeterminate for PBM because of ampullary invasion of carcinoma or biliary/pancreatic stenting or collapse of bile/pancreatic duct (N = 321) were also excluded.

FIGURE 2.

Two types of PBM in the US cohort. PBMs were classified into 2 distinct types based on imaging findings (10). A: “nondilated” (< 1.0 cm) type. B: “dilated” (2: 1.0 cm) type.

Additionally, based on bile duct diameter, PBM was classified as “dilated” (2: 1.0 cm) and “nondilated” (< 1.0 cm) types as has been customary for adult cases described in the literature.7,31,32

Clinical Data

The patient’s age, sex, race, findings on clinical presentation and clinical follow-up data were obtained by contacting the primary physicians or reviewing patients’ charts. The radiologic findings were also evaluated for the size of the bile duct. Presence or absence of cholelithiasis was investigated from gross description and/or MRI/ultrasonography material. A significant proportion of the cases were referral patients, and the data on the treatment they have received was unfortunately not reliable and therefore was not included in the analysis.

Pathological Evaluation

The pathology material of all 1099 cases analyzed in this study was personally reviewed by the authors. For the cases with PBM-associated GBCs that were subjected to further detailed analysis, a mean of 4 tumor slides per case were available for histopathologic examination (range, 1–77). The pathologic characteristics of the GBC including the histopathologic typing of the invasive carcinoma and presence and type of the precursor lesions were investigated per the current classification schemes.33–37 The stage of the tumor was analyzed per AJCC TNM staging parameters.38 Additionally, the degree of peri-tumoral inflammation was assessed semi-quantitatively as negative, mild, moderate, or severe, for each of the inflammatory cell types (lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils) as described previously.37,39–41 Presence or absence of lymphoid follicles and necrosis in the tumor were also recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison was performed between the clinicopathological factors identified in the patients verified to have PBM versus non-PBM by Fisher exact test. Differences between the 2 groups in continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Overall survival and median survival were calculated by the Kaplan Meier method, and survival curves were compared by Log-rank test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analysis was performed with a statistical software package (JMP12, SAS institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

Frequency of PBM in the US Was Similar to that in Japan, and PBM Was Also Closely Associated With Gallbladder and Extrahepatic Bile Duct Cancers, and Choledochal Cysts Of the 300 resected GBCs in the US with adequate imaging available, PBM was detected in 24 cases (8.0%), similar to the 8.8% (15/171) detected in the Japanese GBCs (P = 0.8) (Figures 2 and 3).

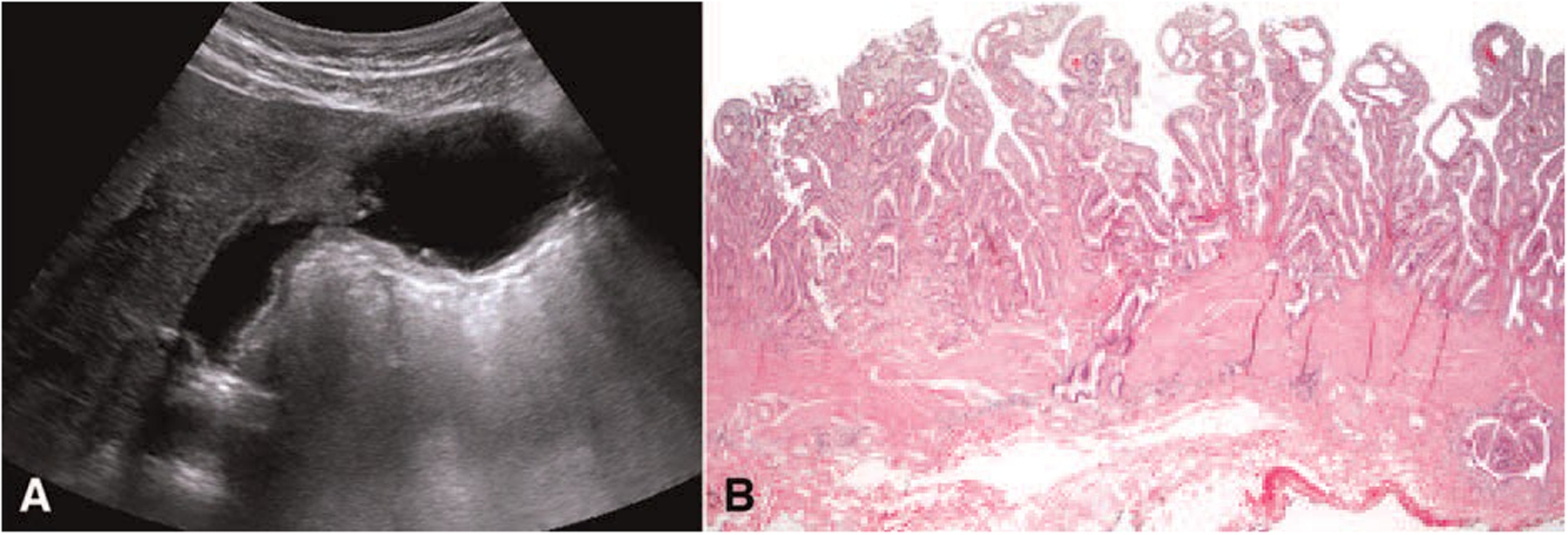

FIGURE 3.

Ultrasonography and histopathological findings in the US cohort. A: Ultrasonography. The diffuse thickness of the inner layer of the gallbladder wall in pancreatobiliary maljunction-associated gallbladder carcinoma. (55 years, female, dilated type) B: Mucosal hyperplasia was seen in the background mucosa. (H&E stain, X20).

One of 42 patients with distal BDCs (2.4%) in the US had PBM findings on MRI. Of note, none of these 25 US cases (24 GBC and 1 BDC) had been diagnosed in the original work-up; this diagnosis was accomplished only in this retrospective study.

Of the 33 patients with choledochal cyst, 5 (15%) had PBM. All of these were female, with a mean age of 42 years (24–69) at surgery. In these 5 cases, mean diameter of the bile duct was 25 mm (range, 13 – 60). Three of these were Type IA, 1 was Type IC and 1 was Type IVA according to the Todani classification.42

No PBM was identified for pancreatobiliary resections performed for other conditions: 0/21 peri-hilar carcinomas, 0/61 intrahepatic BDCs, 0/97 Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (46 of the head and 51 of the body/tail), 0/88 Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (36 of the head and 52 of the body/tail), 0/46 noninvasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, 0/46 mucinous cystic neoplasms, 0/97 routine cholecystectomies without neoplasms.

Forty-seven patients in Japan had undergone prophylactic surgery with preoperative diagnosis of PBM detected during screening (23 underwent simple cholecystectomy, and 24 underwent cholecystectomy with bile duct resection). Two of these patients were found to have “incidental” GBCs in the operation specimen (one T1 and the other T2). Three other patients developed bile duct cancer during the follow-up (see below for details on the follow-up).

Clinicopathologic Characteristics of PBM-Associated GBCs (Table 1)

TABLE 1.

The Clinicopathological Characteristics of Pancreatobiliary Maljunction-Associated Gallbladder Carcinomas

| GBC Cases With PBM | GBC Cases Without PBM | P-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL (N = 39) | US (N = 24) | Japan (N = 15) | P-value US vs Japan | ALL (N = 73) | US (N = 43) | Japan (N = 30) | P-value US vs Japan | PBM Present vs Absent | |

| Race/ethnicity, n | |||||||||

| Asian | 15 | 0 | 15 | <0.0001 | 31 | 1 | 30 | <0.0001 | 0.28 |

| White | 17 | 17 | 0 | 20 | 29 | 0 | |||

| African American | 7 7 0 | 18 | 18 | 0 | |||||

| Age, yr, mean (range) | 63 (34–81) | 62 (35–81) | 65 (50–71) | 0.38 | 66.8 (34–95) | 65 | 70 | 0.19 | 0.06 |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 30 (77) | 20 (83) | 10 (67) | 0.22 | 49 (67) | 27 (63) | 22 (73) | 0.34 | 0.2785 |

| Presenting symptoms | |||||||||

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 27 (69) | 19 (79) | 8 (53) | 0.08 | 43 (59) | 32 (74) | 11 (37) | 0.001 | 0.28 |

| Jaundice, n (%) | 5 (13) | (4) | 4 (27) | 0.04 | 22 (30) | 17 (40) | 5 (17) | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Cholelithiasis, n (%) | 5/35 (14) | 3/20 (15) | 2/15 (13) | 0.88 | 38/66 (58) | 25/36 (69) | 13/30 (43) | 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| Maximum diame er of hebile duc, mm, mean (range) | 7 (4–20) | 11 (4–26) | 0.02 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Status of the bile duct, n | |||||||||

| Dilated Type IA | 312 | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Dilated Type IB | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.08 | |||||

| Dilated Type IC | 413 | ||||||||

| Non-dilated Type | 31 | 22 | 9 | ||||||

| pT stage, n | |||||||||

| pTis–1, n (%) | 6 (15) | 2 (8) | 4 (27) | 0.12 | 15 (21) | 10 (23) | 5 (17) | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| ICPN, n (%) | 12 (31) | 7 (29) | 5 (33) | 0.78 | 9 (12) | 6 (14) | 3 (10) | 0.61 | 0.01 |

| Lymph node metastasis, n (%) | 10/31 (32) | 6/18 (33) | 4/13 (31) | 0.88 | 26/43 (60) | 12/22 (55) | 14/21 (67) | 0.41 | 0.01 |

| Nonordinary carcinoma, n (%) | 8 (21%) | 6 (25) | 2 (13) | 5 (7) | 3 (7) | 2 (7%) | |||

| Sarcomatoid Carcinoma | 312 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Adenosquamous Carcinoma | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.38 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.95 | 0.03 |

| Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma | 000 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Small Cell Carcinoma | 000 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |||||

| Mixed adenocarcinoma/NEC | 330 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Mucinous Carcinoma | 000 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||||

GBC indicates gallbladder carcinoma; ICPN, Intracholecystic papillary-tubular neoplasm; NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma; PBM, pancreatobiliary maljunction.

Clinical Features

Of the 39 cases with PBM-associated GBCs (24 from US, 15 from Japan), 30 were female, suggesting a significant female predominance (female/male ratio, 3:1). This female predominance was even more striking in the US group, where 83% of PBM-associated GBCs were female compared to 63% in the non-PBM GBCs.

The mean age at the time of cholecystectomy was significantly younger (mean, 60.7 years; range, 34 – 81) than that of GBCs without PBM (66.7 years, 34 – 95, P = 0.07). Notably, 21% (n = 5) of PBM-GBCs were younger than 50 years vs 6.5% in GBCs without PBM (P = 0.01). Moreover, when we reviewed GBC patients younger than 50 years old, 22% of these were found to be PBM associated.

Only 14% of PBM-associated GBCs was associated with cholelithiasis vs. 58% in non-PBM cases (P < 0.001). PBM group appeared to present less commonly with jaundice (13% vs 30%, P = 0.04). The diameter of the bile ducts of the PBM-GBC cases in the Japanese group was larger, and jaundice was more common as the presentation sign than those in the US group.

Pathologic Findings

Close to one third of the PBM-associated GBC cases (31%) arose in association with an adenomatous lesion (intracholecystic papillary-tubular neoplasm; ICPN), compared to only 12% in non-PBM group (P = 0.02).

PBM-associated GBCs also had a higher frequency of unusual histopathological types (21%) with 3 sarcomatoid carcinomas, 2 adenosquamous carcinomas, and 3 with neuroendocrine carcinoma component versus these unusual carcinoma types constituting only 7% of non-PBM GBCs (P = 0.03).

Metastasis to lymph nodes identified in the cholecystectomy specimens was less commonly seen in PBM cases (32%) than in non-PBM ones (60%, P = 0.02). T-stage was similar between PBM and non-PBM cases. The Japanese PBM-associated GBCs tended to have a higher number of early stage cancers: 4/15 Japanese PBM cases were T1 (27%), whereas only 2 of the US cases were (8%), P = 0.123.

Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes were more common in PBM versus non-PBM GBCs (69%, vs 44%, P = 0.04). Plasma cell and neutrophilic infiltration in the tumor itself also tended to be more common in PBM cases, although this difference did not reach statisti-cal significance (69% vs 46% and 50% vs 37%, P = 0.05 and P = 0.05, respectively). Frequencies of lymphoid follicle formation and tumor necrosis were not significantly different (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Frequency of Inflammation in Gallbladder Carcinoma Cases

| GBC Cases With PBM (N = 26) | GBC Cases Without PBM (N = 54) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma cell infiltration, n (%) | |||

| Peri-tumoral | 18 (69) | 39 (72) | 0.78 |

| In the tumor stroma | 18 (69) | 25 (46) | 0.05 |

| In the tumor parenchyma | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.14 |

| Lymphocytic infiltration, n (%) | |||

| Peri-tumoral | 18 (69) | 24 (44) | 0.03 |

| In the tumor stroma | 16 (62) | 24 (44) | 0.15 |

| In the tumor parenchyma | 4 (15) | 9 (17) | 0.88 |

| Neutrophilic infiltration, n (%) | |||

| In the tumor stroma | 13 (50) | 20 (37) | 0.27 |

| In the tumor parenchyma | 13 (50) | 15 (28) | 0.05 |

| Lymphoid follicles, n (%) | 18 (69) | 27 (50) | 0.10 |

| Necrosis in the tumor, n (%) | 11 (42) | 22 (41) | 0.89 |

GBC indicates gallbladder carcinoma; PBM, pancreatobiliary maljunction.

Clinical Outcome

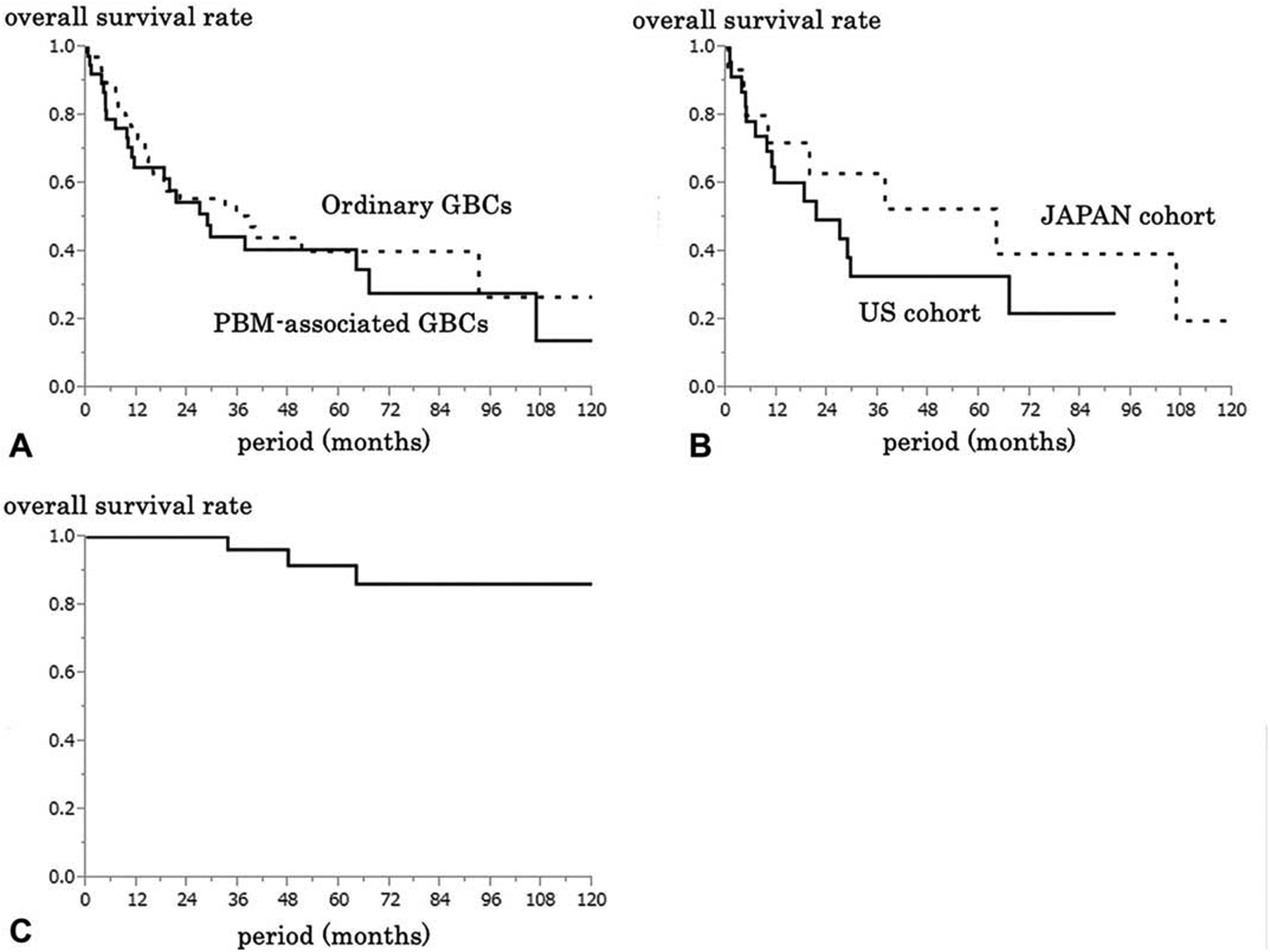

There were no significant differences in prognosis between PBM-associated GBCs versus non-PBM GBCs (median survival: 29 months, 3-year survival rate: 44%, 5-year: 41%, vs median: 38 months, 3-year: 50%, 5-year: 40%, P = 0.5) (Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves. A: A comparison between of patients with pancreatobiliary maljunction (PBM)-associated (n = 39) and not associated (n = 73) GBCs. B: A comparison between of patients with PBM-associated GBCs in the US (n = 24) and Japan (n = 15) cohorts. C: Survival curve of PBM patients who underwent prophylactic cholecystectomy in Japan cohort (n = 40).

The survival of the patients with PBM-associated GBCs in the Japanese group tended to be better than that in the US group, but this did not reach statistical significance (median survival: 64 months, 3-year survival rate: 63%, 5-year: 53%, vs median: 21 months, 3-year: 33%, 5-year: 33%, P = 0.3) (Figure 4B).

All 5 PBMs detected along with choledochal cysts in the US group (none of which had in-situ or invasive carcinoma in the specimen) were still alive during follow-up period (mean, 24 months; range, 13 – 51).

For the 47 Japanese patients who had undergone prophylactic cholecystectomies based on the diagnosis of PBM, follow-up information was available for 40 and the 5-year survival was 92% (Figure 4C). The 2 cases with GBC detected in the cholecystectomy specimens “incidentally” had one T1, and the other, T2 carcinomas. For the remainder, at a median follow-up of 59 months (1 – 152), 3 died of biliary tract carcinoma at 34,48, and 64 months after surgery.

DISCUSSION

This study establishes that the frequency of PBM in GBCs in the US, 8%, is in fact very similar to that seen in Asia (8.8% in the Japanese group in this study, and 4% – 18% in the literature from Asia8,9,43–46). The same is also likely true for extrahepatic bile duct cancers, although the numbers are smaller (detected in 1/42 cases (2.4%) in the US group in this study compared to 4.4% as reported in Asia).23 In fact, considering that PBM was also detected in 15% of the US choledochal cysts (“dilated-type PBM”), and since choledochal cysts are known to be associated with biliary cancers, it is likely that the connection between PBM and bile duct cancers in the US is probably even stronger than disclosed in this study.

This study also demonstrates that PBM is indeed underrecognized in the US In fact, until their discovery during this study, none of the 25 PBMs in the US group had been diagnosed as such during the original patient work up or at any time during their clinical course.

The data in this study also confirms that the risk of gallbladder and distal bile duct cancer is very high in patients with PBM, not only in Asia but also in the West. In addition to accounting for approximately 8% of the GBC cases and 2% to 5% of bile duct cancers in both populations, there are 2 other important findings in this study that indirectly point to the substantive magnitude of this risk. First, PBM is rarely discovered outside the setting of GBC or BDC (or its associated choledochal cysts); none of the 374 US patients who were free of these diseases had PBM. Second, and more important, is the PBM cohort from Japan regarding the patients who had been discovered to harbor PBM during screening and undergone prophylactic surgery for this reason. Two of these patients were found to have GBC in the cholecystectomy specimens, and 3 additional developed cancer in long term follow-up in the remaining biliary tract, suggesting that if surgical intervention had not been performed in this group, potentially many more of them would have developed cancers. All these findings combined indicate that PBM patients are highly prone to develop GBC and BDC. Thus these results suggest that the screening and interference policies developed by the JSPBM4–6 are effective and could be considered also in the US.

This study also brings a different perspective to the choledochal cysts occurring in the West. In Far East, the close association of PBM with some types of choledochal cysts have been well documented to an extent that these choledochal cysts are also referred as “dilated PBM.”2,3,28,42 It is believed that the reflux that is caused by PBM is a factor in the development of these cystic dilatation of the ducts. The association of choledochal cysts with carcinoma may in fact be an epi-phenomenon, through the reflux allowed by PBM in these cases. Therefore, patients with choledochal cysts discovered in the West also ought to be investigated for PBM and placed into the appropriate management protocols discussed below.

Several important aspects of PBM-associated GBCs were also discovered during this study. They are uncommonly associated with gallstones (only 14%). Worldwide, most GBCs are attributed to gallstones. In fact, it is believed that gallstone-associated inflammatory carcinogenesis accounts for more than 90% of GBCs, especially in high-incidence regions like Chile,47,48 whereas, PBM-associated GBCs seem to create a different, reflux-associated proteolytic enzyme-induced chemical carcinogenesis. Furthermore, cancers arising via this mechanism seem to arise at an earlier age, in patients with a mean age that is 6 years younger (mean, 60) than gallstone-associated GBC (mean, 66), and with about a fifth of the PBM-associated GBC patients being younger than 50 years old, and about a fifth of the GBCs under the age of 50 being PBM-associated. This propensity towards development at an earlier age may not be surprising considering that PBM presumably exposes the patient to reflux from birth onwards, whereas gallstones typically develop in later years.

Part of the mechanism by which PBM leads to biliary carcinogenesis has been elucidated in prior studies. The hydrostatic pressure in the pancreatic duct is greater than that of the bile duct.49,50 Therefore, when there is free communication between 2 ducts or a long common channel exists, pancreatic juice flows from the pancreatic duct into the bile duct. Reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the gallbladder is believed to be the cause of carcinoma in patients with PBM and has been implicated even in about 5% of non-PBM cases, which show higher acinar enzyme levels presumably through some reflux mechanism other than PBM.51 This reflux process is accompanied (or preceded) by a distinctive pattern of mucosal hyperplasia that can be referred as reflux-cholecystopathy as a prelude to cancer.52

In the present study, we discovered that the carcinomas occurring in this setting are not only often unaccompanied by gallstones, but they also often develop through the “adenomacarcinoma sequence,” with close to third of cases showing a recognizable intracholecystic papillary tubular neoplasm component which is otherwise uncommon in GBCs [12% in non-PBMs in this study, and 7% in the literature].35 Additionally, this PBM-associated chemical carcinogenesis pathway is more commonly associated with unusual carcinoma types such as sarcomatoid, adenosquamous, and neuroendocrine, than the gallstone-associated type. Of note, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and neutrophils are more commonly seen in the PBM-associated cancers, raising interesting questions regarding the immune nature of these tumors, and also brings up the potential for use of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of these cancers, which needs to be further investigated. Although the survival of the PBM-GBC in Japan seemed to be slightly better, this was not statistically significant, and it may be related to the fact that they also tended to be earlier stage too, which was also not statistically significant in comparison. Larger cohorts that are also controlled for treatment are needed to further investigate these issues. This study, the first to disclose the association of PBM with GBC in the West creates the launching pad for this phenomenon to be recognized also in the West. As experience with this condition improves, and larger cohorts are collected and analyzed, it is quite possible that other biologic and behavioral/prognostic differences will also be identified for this reflux-associated pathway.

Based on these findings, we recommend the following multi-disciplinary practice considerations, some of which are already in place in Far East, to be also employed in the West:

Imaging studies performed for gallbladder and biliary tract disease should also include an evaluation for PBM as a part of the check-list.

If an abdominal ultrasound reveals mucosal thickening in the gallbladder, further investigation for PBM, possibly with additional imaging studies, is warranted as has been recommended by JSPBM.4–6

If reflux cholecystopathy52 findings are discovered in cholecystec-tomy specimens, pathologists should add a comment to emphasize this possibility, and accordingly the patient should be considered for further assessment for PBM, if clinically indicated.

Similarly, if a choledochal cyst is discovered, the possibility of PBM should be investigated specifically in the patient.

All patients with GBC on whom proper imaging studies are available or accessible should be considered for reevaluation for PBM, and if PBM is discovered, it may be wiser to place the patient on surveillance for bile duct cancers. This is particularly important if the GBC is superficial and curable because then the risk PBM poses for the bile ducts may become a bigger concern on long term follow-up. If the GBC is not associated with gallstones, arises in a patient younger than 50, or coexists with ICPN or synchronous bile duct neoplasm, or is an unusual phenotype (sarcomatoid, adenosquamous or neuroendocrine), then the suspicion of PBM should be even greater.

If a patient with PBM-associated GBC is planned to undergo cholecystectomy or other biliary tract surgery, a pre-operative bile duct brushing and/or choledocoscopy should be performed to investigate for possible synchronous bile duct neoplasia. If this is not possible, intraoperative bile duct brushing may be considered.

In conclusion, this study shows that PBM has a similar incidence and close association with gallbladder and biliary cancer in the US as it does in the Far East. Recognition of this phenome-non by medical community in the West is crucial for the timely and accurate diagnosis, proper patient management and prevention of the gallbladder/biliary cancers it leads to. This study also establishes for the first time that GBCs arising in association with PBMs have distinct clinicopathologic associations (including the young age of onset, lack of direct gallstone association, more common induction of adenoma-carcinoma sequence and unusual carcinoma types). GBC patients especially showing these characteristics, as well as any patient with surrogate associates of PBM such as choledochal cysts, gallbladder mucosal hyperplasia with reflux cholecystopathy, and synchronous neoplasms in biliary tree ought to be investigated for PBM by further imaging analysis since the entire extrahepatic biliary duct system is at risk for such patients. PBM-related GBCs form a distinct model of tumorigenesis different than the gallstone-inflammation pathway for cancer researchers to analyze, which may shed great light to the mechanisms of carcinogenesis at large. More importantly, this model brings new perspectives to the etiopathogenesis of pancreatobiliary tract cancers, revealing that an anatomic variation can lead to reflux-associated chemical carcinogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Keita Kanai, Department of Gastroenterology, Nagano Municipal Hospital, Jumpei Asano, Takayuki Watanabe, Department of Gastroenterology, Shinshu University Hospital, for assistance with the data collections.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kozumi K, Kodama T. A case of cystic dilatation of the common bile duct and etiology of the disease (in Japanese). Tokyo Med J. 1916;30:1413–1423. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babbitt DP. Congenital choledochal cysts: new etiological concept based on anomalous relationships of the common bile duct and pancreatic bulb. Ann Radiol (Paris). 1969;12:231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Komi N, Kuwashima T, Kuramoto M, et al. Anomalous arrangement of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system in choledochal cyst. Tokushima J Exp Med. 1976;23:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction (JSGPM). Committee for Diagnostic Criteria for Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction. Diagnostic criteria of pancreaticobiliary maljunction (in Japanese). Tan to Sui. 1987;8:115–118. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction (JSPBM). The Committee of JSPBM for Diagnostic Criteria. Diagnostic criteria of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1994;1:219–221. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamisawa T, Ando H, Hamada Y, et al. Diagnostic criteria for pancreaticobiliary maljunction 2013. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:159–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morine Y, Shimada M, Takamatsu H, et al. Clinical features of pancreaticobiliary maljunction: update analysis of 2nd Japan-nationwide survey. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:472–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasumi A, Matsui H, Sugioka A, et al. Precancerous conditions of biliary tract cancer in patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction: reappraisal of nationwide survey in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang J, Jang JY, Kang MJ, et al. Clinicopathologic differences in patients with gallbladder cancer according to the presence of anomalous biliopancreatic junction. World J Surg. 2016;40:1211 – 1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamisawa T, Ando H, Suyama M, et al. Japanese clinical practice guidelines for pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:731–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motosugi U, Ichikawa T, Araki T, et al. Secretin-stimulating MRCP in patients with pancreatobiliary maljunction and occult pancreatobiliary reflux: direct demonstration of pancreatobiliary reflux. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:2262 – 2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugiyama Y, Kobori H, Hakamada K, et al. Altered bile composition in the gallbladder and common bile duct of patients with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction. World J Surg. 2000;24:17–20. discussion 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang CM, Kim KS, Choi JS, et al. Gallbladder carcinoma associated with anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct junction. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21: 383–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ragot E, Mabrut JY, Ouaissi M, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunctions in European patients with bile duct cysts: results of the multicenter study of the French Surgical Association (AFC). World J Surg. 2017;41:538–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamada Y, Ando H, Kamisawa T, et al. Diagnostic criteria for congenital biliary dilatation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2016;23:342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison EM, Parks WR. Congenital disorders of the pancreas: surgical considerations. In: Jarnagin William R, editor. Blumgart’s Surgery of the Lover, Biliary Tract and Pancreas, 2-volume Set. 6th ed., Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, London, Hong Kong, Sydney, Tokyo: Elsevier Saunders press; 2017:861–874. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bechtler M, Eickhoff A, Willis S, et al. Choledochal cysttype IAwithdrainage through the ventral duct in pancreas divisum. Endoscopy. 2009;41(Suppl 2): E71–E72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia Cano J, Godoy MA, Morillas Arino J, et al. Pancreatobiliary maljunction. Not only an Eastern disease. An Med Interna. 2007;24:384–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adham M, Valette PJ, Partensky C. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction without choledochal dilatation associated with gallbladder cancer: report of 2 European cases. Surgery. 2005;138:961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alkhatib AA, Hilden K, Adler DG. Incidental pancreatography via ERCP in patients with anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction does not result in pancreatitis in a North American population. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1064 – 1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roland G, Ruiz A, Arrive L. Gallbladder carcinoma with anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35:779–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction without congenital choledochal cyst. Br J Surg. 1998;85:911–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irie H, Honda H, Jimi M, et al. Value of MR cholangiopancreatography in evaluating choledochal cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1381 – 1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugiyama M, Baba M, Atomi Y, et al. Diagnosis of anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction: value of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Surgery. 1998;123:391–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matos C, Nicaise N, Deviere J, et al. Choledochal cysts: comparison of findings at MR cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in eight patients. Radiology. 1998;209:443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Itokawa F, Kamisawa T, Nakano T, et al. Exploring the length of the common channel of pancreaticobiliary maljunction on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:68 – 73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirohashi S, Hirohashi R, Uchida H, et al. Pancreatitis: evaluation with MR cholangiopancreatography in children. Radiology. 1997;203:411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim MJ, Han SJ, Yoon CS, et al. Using MR cholangiopancreatography to reveal anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union in infants and children with choledochal cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa N, et al. MRCP of congenital pancreaticobiliary malformation. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam WW, Lam TP, Saing H, et al. MR cholangiography and CT cholangiography of pediatric patients with choledochal cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:401–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hueman MT, Vollmer CM Jr, Pawlik TM. Evolving treatment strategies for gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2101–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Itoi T, Kamisawa T, Fujii H, et al. Extrahepatic bile ductmeasurementbyusing transabdominal ultrasound in Japanese adults: multi-center prospective study. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1045–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albores-Saavedra J, Adsay NV, Crawford JM. Carcinoma of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed., Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010:266–273. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adsay NV. Gallbladder, extrahepatic biliary tree and ampulla. In: Mills S, Greenson JK, Hornick JL, eds. Stemberg’s Diagnostic Surgical Pathology. 6th ed., Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, London, Hong Kong, Sydney, Tokyo: Wolters Kluwer Press; 2015:1770–1846. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adsay V, Jang KT, Roa JC, et al. Intracholecystic papillary-tubular neoplasms (ICPN) of the gallbladder (neoplastic polyps, adenomas, and papillary neoplasms that are >/= 1.0 cm): clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 123 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36: 1279–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kloppel G, Adsay V, Konukiewitz B, et al. Precancerous lesions of the biliary tree. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roa JC, Tapia O, Cakir A, et al. Squamous cell and adenosquamous carcinomas of the gallbladder: clinicopathological analysis of 34 cases identified in 606 carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1069–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adsay NV, Bagci P, Tajiri T, et al. Pathologic staging of pancreatic, ampullary, biliary, and gallbladder cancers: pitfalls and practical limitations of the current AJCC/UICC TNM staging system and opportunities for improvement. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2012;29:127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alrawi SJ, Tan D, Stoler DL, et al. Tissue eosinophilic infiltration: a useful marker for assessing stromal invasion, survival and locoregional recurrence in head and neck squamous neoplasia. Cancer J. 2005;11:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quaedvlieg PJ, Creytens DH, Epping GG, et al. Histopathological characteristics of metastasizing squamous cell carcinoma of the skin and lips. Histopathology. 2006;49:256–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohashi Y, Ishibashi S, Suzuki T, et al. Significance of tumor associated tissue eosinophilia and other inflammatory cell infiltrate in early esoph-ageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(5a):3025 – 3030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, et al. Congenital bile duct cysts: classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134:263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M, Nakayama F. Adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder associated with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction. Am Surg. 1993;59:430–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu B, Gong B, Zhou DY. Association of anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction with gallbladder carcinoma in Chinese patients: an ERCP study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chao TC, Jan YY, Chen MF. Primary carcinoma of the gallbladder associated with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21:306–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elnemr A, Ohta T, Kayahara M, et al. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction without bile duct dilatation in gallbladder cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:382–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Espinoza JA, Bizama C, Garcia P, et al. The inflammatory inception of gallbladder cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1865:245 – 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koshiol J, Castro F, Kemp TJ, et al. Association of inflammatory and other immune markers with gallbladder cancer: results from two independent case-control studies. Cytokine. 2016;83:217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carr-Locke DL, Gregg JA. Endoscopic manometry of pancreatic and biliary sphincter zones in man. Basal results in healthy volunteers. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Csendes A, Kruse A, Funch-Jensen P, et al. Pressure measurements in the biliary and pancreatic duct systems in controls and in patients with gallstones, previous cholecystectomy, or common bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:1203–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horaguchi J, Fujita N, Kamisawa T, et al. Pancreatobiliary reflux in individuals with a normal pancreaticobiliary junction: a prospective multicenter study. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:875–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muraki T, Memis B, Reid MD, et al. Reflux-associated cholecystop-athy: analysis of 76 gallbladders from patients with supra-oddi union of the pancreatic duct and common bile duct (pancreatobiliary mal-junction) elucidates a specific diagnostic pattern of mucosal hyper-plasia as a prelude to carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:1167–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]