Abstract

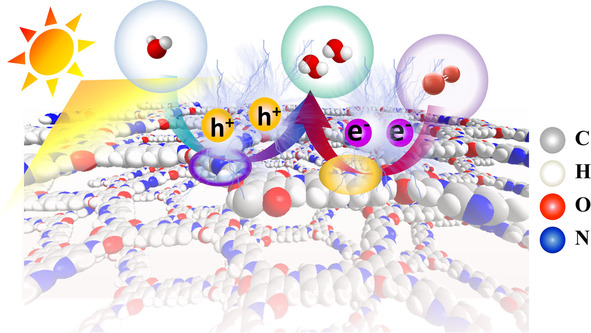

Synthesizing H2O2 from water and air via a photocatalytic approach is ideal for efficient production of this chemical at small‐scale. However, the poor activity and selectivity of the 2 e− water oxidation reaction (WOR) greatly restricts the efficiency of photocatalytic H2O2 production. Herein we prepare a bipyridine‐based covalent organic framework photocatalyst (denoted as COF‐TfpBpy) for H2O2 production from water and air. The solar‐to‐chemical conversion (SCC) efficiency at 298 K and 333 K is 0.57 % and 1.08 %, respectively, which are higher than the current reported highest value. The resulting H2O2 solution is capable of degrading pollutants. A mechanistic study revealed that the excellent photocatalytic activity of COF‐TfpBpy is due to the protonation of bipyridine monomer, which promotes the rate‐determining reaction (2 e− WOR) and then enhances Yeager‐type oxygen adsorption to accelerate 2 e− one‐step oxygen reduction. This work demonstrates, for the first time, the COF‐catalyzed photosynthesis of H2O2 from water and air; and paves the way for wastewater treatment using photocatalytic H2O2 solution.

Keywords: Bipyridine, COFs, Environmental Chemistry, H2O2 , Photosynthesis

A bipyridine‐based covalent organic framework photocatalyst (COF‐TfpBpy) showed excellent activity for H2O2 photosynthesis with a solar‐to‐chemical conversion efficiency of 0.57 % at 298 K and 1.08 % at 333 K. The photocatalytic process involves a 2 e− water oxidation and 2 e− oxygen reduction from water and air. The photocatalytic H2O2 solution can be directly used for Rhodamine B degradation and sterilization of E. coli.

Introduction

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is widely used in the restoration of water environment as an environmentally friendly strong oxidant. It has been reported that many pollutants, including organic dyes, organochlorine pesticides, cyanides, phenols, antibiotics, microplastics, and personal care products, can be treated with H2O2. [1] In addition, H2O2 can also be used as an environmentally friendly disinfectant to inactivate pathogenic microorganisms, since it does not cause secondary pollution to the environment. [2] Due to the increased awareness in environmental protection and the current COVID‐19 pandemic, the demand for H2O2 is expected to increase substantially.

At present, the typical industrial production of H2O2 is based on anthraquinone method. However, this method involves expensive palladium‐based catalysts and complex reactions (catalyst hydrogenation and oxidation processes). It also requires a large amount of organic agents and generates toxic by‐products. [3] Therefore, it is very important to develop the alternative approach for H2O2 manufacture based on efficient, economical and environmentally‐friendly process. In recent years, photocatalytic synthesis of H2O2 utilizing semiconductor catalysts has attracted significant interests. [4] Visible‐light‐responsive non‐metal polymers have also been investigated as potential catalysts for H2O2 photosynthesis due to the low stability of H2O2 under UV light, heat, and in the presence of metal ions. [5] Among the reported non‐metal photocatalysts,[ 6 , 7 ] graphitic carbon nitride (g‐C3N4) is the most widely studied. This is attributed to the rich active sites of imine (C=N), which facilitate good catalytic activity for H2O2 photosynthesis. [7] Without the presence of sacrificial reagents, however, the g‐C3N4 catalyzed photosynthetic production rate of H2O2 does not exceed 100 μM h−1 under one standard sun light. Although the catalytic performance of g‐C3N4 can be improved by composite, defect and single‐atom engineering,[ 7 , 8 ] the efficiency of H2O2 production over g‐C3N4 based photocatalysts is still poor without the addition of sacrificial reagents or stabilizers.[ 8b , 8c , 9 ] Accordingly, the development of novel, efficient visible‐light‐responsive non‐metal semiconductor materials is of particular interest.

Covalent organic framework compounds (COFs) are a new type of visible‐light‐responsive non‐metallic polymer which have developed substantially in recent years. [10] Preliminary studies have shown that COFs have great potential in photocatalytic hydrogen production and CO2 reduction, [11] but there are few reports on its applications on the photocatalytic synthesis of H2O2. [5d] Based on structural analysis, COFs have a highly ordered porous crystalline network structure to prevent the recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes, and the energy band and reactive sites can be structured at the molecular level. The structural characteristics impart these unique properties on COFs, which are known to improve catalyst activity. Therefore, COFs are envisaged as promising photocatalysts for the light‐driven synthesis of H2O2 without a sacrificial reagent.

In this work, bipyridine based COFs containing imine bonds are compared with g‐C3N4 (possessing a C=N reactive site) for the photocatalytic production of H2O2 from water and air. Firstly, we have verified that bipyridine based COFs featured a high activity for the production of H2O2 from water and air. The optimized photosynthetic rate of H2O2 reached 1042 μM h−1 under one standard sun light at 298 K, which was 496 times more efficient than that for pure g‐C3N4 (2.1 μM h−1). The apparent quantum yield (AQY) between 420–550 nm was greater than 8 %. The solar‐to‐chemical conversion (SCC) efficiency was 0.57 % for H2O2 synthesis, a value that substantially higher than the typical photosynthetic efficiency of plants (≈0.10 %). [12] The SCC efficiency of the same catalyst at 333 K (1.08 %) was also higher than the highest value to date (1.0 %, no sacrifice reagents and buffer reagents). [13] After 8 h of irradiation (the average duration of light in a day), the concentration of synthesized H2O2 reached 5.6 mM, which was directly used to degrade Rhodamine B (RhB) and inactivate Escherichia coli (E. coli). More importantly, we revealed the importance of bipyridine in COFs for H2O2 photocatalytic production from water and air. Bipyridine presents as active site, which is directly involved in the photocatalytic production of H2O2 via a 2 e− one‐step redox reactions. Our findings revealed that COFs are excellent catalysts for the visible‐light‐driven production of H2O2, and this class of compounds may be a good starting point in the search for more active COFs photocatalysts.

Results and Discussion

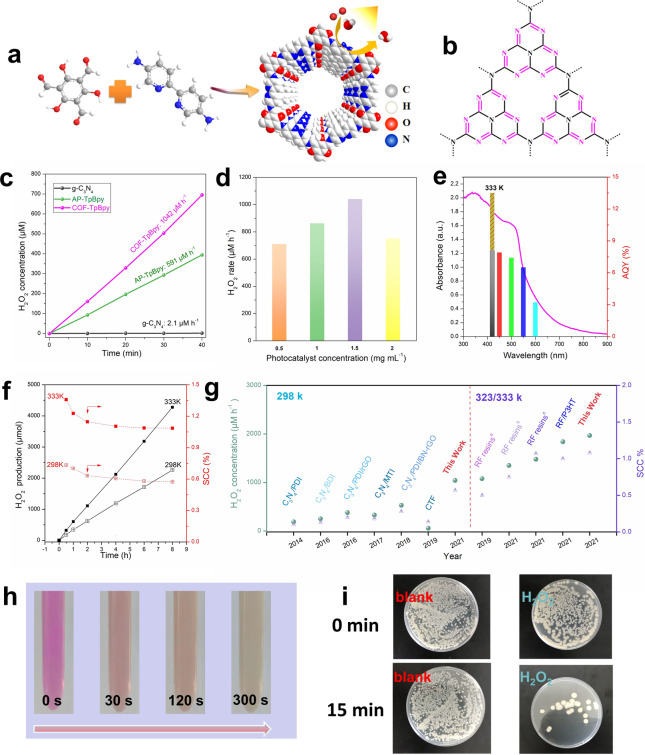

Figure 1a and Figure 1b showed the molecular structures of bipyridine‐based COF and g‐C3N4, respectively. Bipyridine‐based COF (COF‐TfpBpy) and the corresponding amorphous polymer (AP‐TfpBpy) were prepared from 1,3,5‐triformylphloroglucinol (Tfp) and 2,2′‐bipyridine‐5,5′‐diamine (Bpy). Different from the XRD characteristic peak of AP‐TfpBpy, the strong XRD peak of COF at 2θ=3.68° corresponded to the (100) plane, indicating that the COF material has a better crystalline morphology (Figure S1a). Further characterization data of IR, 13C NMR and XPS confirmed the same chemical composition and bond structure of AP‐TfpBpy and COF‐TfpBpy, respectively (Figure S1b–d, Figure S2). SEM and TEM images showed that the crystals of COF‐TfpBpy and AP‐TfpBpy are both interlaced linear morphology, and COF‐TfpBpy has better crystallinity (Figure S3). And thus, it possesses a higher specific surface area than AP‐TfpBpy (Figure S4) and g‐C3N4 (Figure S5). X‐ray diffraction (XRD), infrared spectroscopy (IR), X‐ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) indicated the successful preparation of typical g‐C3N4 samples (Figure S5–S7). For photocatalytic H2O2 production, water and air were employed as the oxygen and hydrogen sources. One xenon lamp (λ>420 nm; light intensity at 420–700 nm: 40.8 mW cm−2) was used as a light source. Peroxidase (POD) chromogenic method was used to determine the H2O2 concentrations due to the low interference with different electron sacrificial reagents addition, and the standard curve is drawn (Figure S8, S9).

Figure 1.

Photocatalytic performance of COF‐TfpBpy, AP‐TfpBpy and g‐C3N4 for H2O2 production from water and air. a) Schematic diagram of synthesis of COF‐TfpBpy with bipyridine active sites. b) Schematic structures of g‐C3N4 with C=N active sites. c) Photocatalytic activity of COF‐TfpBpy, AP‐TfpBpy and g‐C3N4 for H2O2 production in pure water. Conditions: λ>420 nm (298 K; xenon lamp, light intensity at 420–700 nm: 40.8 mW cm−2), water (10 ml), catalyst (15 mg). d) Photocatalytic activity of COF‐TfpBpy with different catalyst concentrations. Apparent quantum efficiency (e) and solar‐to‐chemical conversion efficiency (f) of COF‐TfpBpy. Conditions: λ>420 nm at 333 K or λ>300 nm at 298 K (xenon lamp, light intensity at 420–700 nm: 40.8 mW cm−2), water (400 ml), catalyst (600 mg). g) performance comparison of COF‐TfpBpy with other reported photocatalysts. h) RhB (10 mg L−1) decomposition in a photocatalytically produced H2O2 solution of via a fenton reaction. i) Sterilization of E. coli with a photocatalytically produced H2O2 solution.

Figure 1c revealed the photocatalytic activity of COF‐TfpBpy, AP‐TfpBpy and g‐C3N4. There is a clear linear relationship between H2O2 production and irradiation time. After 40 min of irradiation, the H2O2 concentration in the presence of COF‐TfpBpy reached 695 μM, which was about 1.8 and 496 times more efficient than that produced in the presence of AP‐TfpBpy (394 μM) and g‐C3N4 (1.4 μM), respectively. Figure 1d shows the photosynthetic rate of H2O2 in 10 ml water with different amounts of COF‐TfpBpy (5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, 20 mg) to assess the optimum catalyst concentration. It was found that 15 mg of COF‐TfpBpy (1.5 g L−1) furnished the highest photosynthetic rate of 1042 μM h−1, which is the best of those evaluated under one standard sun light (Table S1). The decreasing of H2O2 concentration alone with increasing concentrations of COF‐TfpBpy may be attributed to the fact that excess catalyst affects the light absorption of the reaction system. Figure 1e, f show the AQY and SCC efficiency of H2O2 production in water and air over COF‐TfpBpy, under the optimal catalyst concentration (1.5 g L−1 COF‐TfpBpy) in 400 mL water. At 298 K, the AQY@420 nm of COF‐TfpBpy was 8.1 %, with a total SCC efficiency of 0.57 %. At 333 K, the AQY@420 nm and SCC efficiency of COF‐TfpBpy were 13.6 % and 1.08 %, respectively, which were higher than the most efficient photocatalyst RF/P3HT (AQY, 10 %; SCC efficiency, 1.0 %; Figure 1g and Table S1). [13] To the best of our knowledge, COF‐TfpBpy is the first COFs catalyst reported that can photocatalytically produce H2O2 without the presence of sacrificial reagents or stabilizers. [5d]

At present, the reported concentrations of H2O2 photocatalytically produced after 8 h (the average time of light in a day) are at the mM level, which can be used directly for environmental remediation. [2] However, there were few reports on the use of H2O2 solutions generated by photocatalysis in treatment of pollutants, due to the presence of sacrificial reagents or buffers. In this work, after 8 h irradiation, the H2O2 concentration in COF‐TfpBpy system was 5.6 mM; and the H2O2 concentration was 5.4 mM even after five cycles (Figure S10a). The XRD and IR spectroscopy (Figure S10) on COF‐TfpBpy after the reaction showed that the catalyst had good stability in the photocatalytic process. When the equilibrium concentration of H2O2 reached 29.5 mM after 60 h irradiation (Figure S10b and c), the broadening of 26.5 degrees XRD peak (Figure S10d) indicated the slight exfoliation of the COF‐TfpBpy, although its photocatalytic activity was not affected. These findings indicated that COF‐TfpBpy is a recyclable photocatalyst. In order to verify the feasibility of the photocatalytically produced H2O2 solution for pollutant removal, RhB and E. coli were chosen as the target pollutants. Figure 1h shows that a 3.5 mL RhB solution (10 mg L−1) can be completely decomposed within 5 min by adding 0.5 mL (5.6 mM) of a photocatalytically produced H2O2 solution (Video S1). The growth of E. coli was effectively inhibited after 200 μL of a photocatalytically produced H2O2 solution was added into the plate (Figure 1i). These results revealed that the photocatalytic produced H2O2 solutions can be directly applied for the treatment of environmental pollutants with excellent performance.

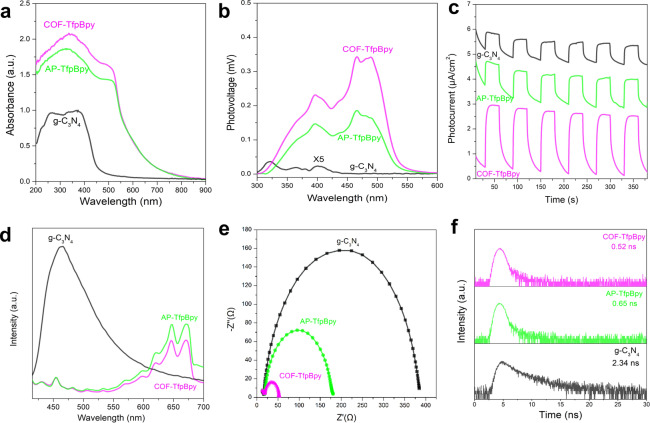

The prerequisite for the occurrence of a catalytic reaction is that thermodynamics permits it. The band structure of COF‐TfpBpy, AP‐TfpBpy and g‐C3N4 were confirmed by experimental methods. Figure 2a displays the UV/Visible diffuse reflectance spectrum (DRS). It can be seen that COF‐TfpBpy and AP‐TfpBpy have a wider visible light absorption range than that of the g‐C3N4. In addition, surface photovoltage spectroscopy (SPV) revealed a high photoinduced voltage for COF‐TfpBpy (Figure 2b). According to the plots of (a h v)1/2 vs photon energy (h v), the band gap energies (E g) of COF‐TfpBpy, AP‐TfpBpy and g‐C3N4 were calculated as 2.37. 2.32 and 2.86 eV, respectively (Figure S11). According to the Mott–Schottky plots, the E CB of COF‐TfpBpy, AP‐TfpBpy and g‐C3N4 were calculated as 0.21 V, 0.23 V and −0.67 V, respectively (Figure S12). Based on the equation E g=E VB−E CB, the VB positions of COF‐TfpBpy, AP‐TfpBpy and g‐C3N4 were calculated as 2.58, 2.55 and 2.20 V. As shown in Figure S13, the band structures of COF‐TfpBpy and AP‐TfpBpy were sufficient for the synthesis of H2O2 from H2O (E =+1.78 V vs NHE) and O2 (E =+0.68 V vs NHE). [12] On the other hand, COF‐TfpBpy also displayed higher wettability than that of the g‐C3N4 (Figure S14), which ensures the good dispersion in water for H2O2 photosynthesis.

Figure 2.

The efficiencies of light absorption and photogenerated carrier separation of COF‐TfpBpy, AP‐TfpBpy and g‐C3N4. a) DRS spectra. b) SPV spectra. c) Photocurrent. d) Fluorescence spectra. e) EIS spectra. f) TFS spectra.

Except for the high light absorption efficiency of COF‐TfpBpy and AP‐TfpBpy (Figure 2a and b), the efficiency of photogenerated carrier separation should be another important reason for the high activity of H2O2 photocatalysis.[ 14 , 15 ] The photocurrent response is related to the separation rate of electrons and holes generated by light. As shown in Figure 2c, the photocurrent density of COF‐TfpBpy was significantly higher than that of AP‐TfpBpy and g‐C3N4, which indicated the COF‐TfpBpy had a higher charge separation efficiency and more usable surface carriers in photocatalytic reaction. [15] Furthermore, the lower fluorescence intensity of COF‐TfpBpy indicated that the crystallization affects the separation efficiency of the photocarriers (Figure 2d). [16] It also can been found that the multiple PL and SPV signals due to the wide molecular weight distribution and a large number of defects of COF‐TfpBpy and AP‐TfpBpy. Crystalline COF‐TfpBpy displays higher separation efficiency than amorphous AP‐TfpBpy and g‐C3N4. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and transient fluorescence spectroscopy (TFS) are effective methods to evaluate the motion characteristics of carriers. As shown in Figure 2e and f, COF‐TfpBpy had a smaller charge transfer resistance, which lead to a faster interface electron transfer speed. In addition, the average relaxation lifetime of COF‐TfpBpy (0.52 ns) was lower than that of AP‐TfpBpy (0.65 ns) and g‐C3N4 (2.34 ns). [14] It also indicated that photogenerated carriers of COF‐TfpBpy were more quickly captured by reactive substrates and thus were able to drive redox reactions, and the separation of electrons and holes in COF‐TfpBpy was particularly efficient. [14] However, only a 1.8‐fold improvement in reaction rate (from 591 μM h−1 of AP‐TfpBpy to 1042 μM h−1 of COF‐TfpBpy) revealed that the crystallinity was not the key reason for the high performance of the bipyridine based polymers. On the contrary, the 281‐fold improvement in reaction rate, from 2.1 μM h−1 of g‐C3N4 to 591 μM h−1 of AP‐TfpBpy, indicated that the difference in active sites of photocatalysts was responsible for the high performance of the bipyridine based polymers.

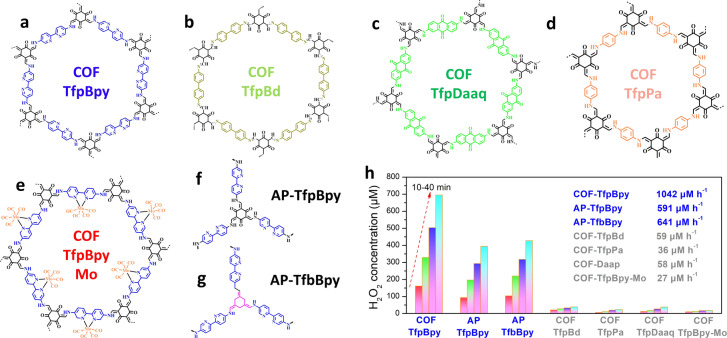

In order to determine which monomer is the active site in COF‐TfpBpy (Figure 3a), the bipyridine monomer was replaced by benzidine (Bd), 2,6‐diaminoanthraquinone (Daaq) or p‐phenylenediamine (Pa) to form COF‐TfpBd (Figure 3b), COF‐TfpDaaq (Figure 3c) and COF‐TfpPa (Figure 3d), respectively. The structure, chemical bond, morphology, specific surface area and light absorption capacity of the prepared COF‐TfpBd, COF‐TfpDaaq and COF‐TfpPa were determined by PXRD, IR, 13C NMR, XPS, SEM, TEM and BET (Figure S15–S25), and the suitable band structures for photocatalytic H2O2 production by the above three COFs were determined by DRS and Mott–Schottky plots. Finally, the performance of these materials on H2O2 photocatalytic synthesis was studied. It was found that the activities were 59, 58 and 36 μM h−1 for COF‐TfpBd, COF‐TfpDaaq and COF‐TfpPa, respectively, all of which were far below the performance of COF‐TfpBpy and AP‐TfpBpy. On the other hand, Mo was used to block the nitrogen atom of 2,2′‐bipyridine of the COF‐TfpBpy (COF‐TfpBpy‐Mo) to evaluate the importance of the bipyridine monomer (Figure 3e and Figure S26–S29). The rate of H2O2 production in the presence of COF‐TfpBpy‐Mo was 26 μM h−1, which was also far below the performance of COF‐TfpBpy and AP‐TfpBpy (Figure 3f). It indicated that bipyridine is the active site of COF‐TfpBpy in the light driven reaction. Another 2,2′‐bipyridine based amorphous polymer (AP‐TfbBpy) formed from 1,3,5‐triformyl benzene (Tfb) and 2,2′‐bipyridine‐5,5′‐diamine (Bpy) was prepared to verify the importance of bipyridine active site (Figure 3g and Figure S30, S31). According to the XRD spectrum (Figure S30a), both AP‐TfpBpy and AP‐TfbBpy were amorphous, and the activity of AP‐TfbBpy was 641 μM h−1, which was very close to that of the AP‐TfpBpy (Figure 3h). It implied the importance of bipyridine in the photocatalysts for H2O2 production. In order to eliminate the influence of specific surface area on photocatalytic performances, the specific surface area rates of materials were compared. As shown in Figure S32, the photocatalytic H2O2 production of bipyridine based COFs (COF‐TfpBpy: 73.9 μM h−1 m−2; AP‐TfbBpy: 45.5 μM h−1 m−2) was much more efficient than that of the non‐bipyridine COFs (COF‐TfpDaaq: 5.9 μM h−1 m−2; COF‐TfpBd: 6.6 μM h−1 m−2; COF‐TfpPa: 3.9 μM h−1 m−2). And the linear bipyridine non‐porous polymer (surface area: 38.2 m2 g−1) also showed higher activity (247 μM h−1) than those of the g‐C3N4 and non‐bipyridine COFs (Figure S33). Therefore, the bipyridine active site, rather than the material porosity, determines the photocatalytic activity of COFs presented in this study.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures and photocatalytic performance of different COFs and APs for H2O2 photocatalytic production from water and air at 298 K. a) Structure of COF‐TfpBpy. b) Structure of COF‐TfpBd. c) Structure of COF‐TfpDaaq. d) Structure of COF‐TfpPa. e) Structure of COF‐TfpBpy‐Mo. f) Structure of AP‐TfpBpy. g) Structure of AP‐TfbBpy. h) H2O2 photocatalysis rates of different COFs and amorphous polymer photocatalysts.

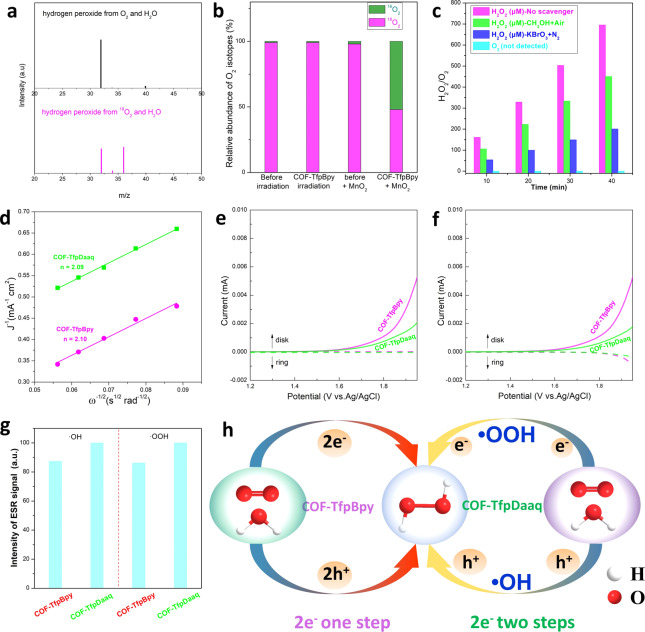

To study the role of bipyridine in COFs for H2O2 photocatalytic production from water and air, the water oxidation and oxygen reduction were tested. Firstly, 18O2 isotope experiments are preformed (Figure 4a and b), no additional 16O2 was detected and almost no oxygen can be measured from WOR half reaction with 0.1 M KBrO4 as e− trapping agent in Ar atmosphere (Figure 4c), which indicated that the 4 e− oxidation of water to oxygen did not occur. On the other hand, the decomposition product of the reaction between photogenerated H2O2 and MnO2 consisted of 1 : 1 18O and 16O. And the ORR half reaction rate (675 μM h−1) was about two folds treater than that of WOR rate (302 μM h−1). These indicated the atom utilization efficiency for the reaction between H2O and O2 (to generate H2O2) was close to 100 %, and the H2O2 photosynthesis underwent 2 e− ORR and 2 e− WOR pathways.

Figure 4.

The effect of the bipyridine monomer on H2O2 photocatalysis. a) and b) 18O2 isotope experiment to explore the source of H2O2. c) Amount of O2 and H2O2 produced on COF‐TfpBpy in KBrO4 (0.1 M, as the electron acceptor) solution, and H2O2 produced on COF‐TfpBpy in CH3OH (10 % v/v, as the hole acceptor) solution. d) The Koutecky–Levich plots obtained by RDE measurements versus Ag/AgCl. e) and f) RRDE voltammograms obtained in 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution with a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 and a rotation rate of 1000 rpm. The potential of the Pt ring electrode is set at −0.23 V versus Ag/AgCl to detect O2. The potential of the Pt ring electrode is set to 0.6 V versus Ag/AgCl to detect H2O2. The oxidation current observed during RRDE tests indicates the oxidation of H2O2 occurs at the ring electrode. g) The intensity of ESR signal of ⋅OOH and ⋅OH by COF‐TfpBpy and COF‐TfpDaaq. h) The diagram of 2 e− two‐steps and 2 e− one‐step redox process.

We further investigated the 2 e− ORR and 2 e− WOR pathways of COFs using rotating disk electrode (RDE) and rotating ring‐disk electrode (RRDE) measurements, respectively. As shown in Figure 4d and Figure S34, the average electron transfer number involved in oxygen reduction reactions were calculated to be 2.10 and 2.09 for COF‐TfpBpy and COF‐TfpDaaq, respectively. It indicated that 2 e− ORR pathway was independent of bipyridine site. During RRDE tests, the potential of the rotating disk electrode was scanned from 1.2 to 1.95 V (vs Ag/AgCl) with a scan rate of 10 mV s−1, while a constant potential of −0.23 V was applied to the Pt ring electrode. In this setup, the O2 generated at the rotating disk electrode can be swept to the ring electrode where O2 can be reduced. As shown in Figure 4e, the increasing disk currents with potentials higher than 1.5 V (solid lines, vs Ag/AgCl) indicate that water oxidation occurred at the rotating disk electrode for both COF‐TfpBpy and COF‐TfpDaaq. No reduction currents were observed for COF‐TfpBpy and COF‐TfpDaaq at the Pt ring electrode, suggesting that COF‐TfpBpy and COF‐TfpDaaq cannot generate O2 via water oxidation (4 e− WOR process). However, when the potential applied at the ring electrode was changed to an oxidative potential of +0.6 V, a much higher oxidation current can be observed for COF‐TfpBpy compared to COF‐TfpDaaq, due to H2O2 oxidation at the Pt ring electrode (Figure 4f). Hence, the RDE and RRDE measurements supported that H2O2 photosynthesis underwent 2 e− ORR and 2 e− WOR pathways for COFs.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

Whether COF has bipyridine site or not, it shows a 2 e− redox process. But, bipyridine sites may result in different reaction steps for H2O2 photosynthesis. It has been reported two routes for ORR and two routes for WOR, which are possible for the photocatalytic synthesis of H2O2 from water and air via 2 e− redox process. The WOR routes include a 2 e− two‐steps process for H2O2 synthesis with ⋅OH as the intermediate species [Eq. (1) and (2)], and a 2 e− one‐step WOR process for H2O2 generation [Eq. (3)]. ORR routes include a 2 e− two‐steps ORR process for H2O2 synthesis with ⋅OOH as the intermediate species [Eq. (4) amd (5)], and a 2 e− one‐step ORR process for H2O2 generation [Eq. (6)]. In order to study the effect of bipyridine site on the mechanisms of H2O2 production, ⋅OOH and ⋅OH from bipyridine based COF‐TfpBpy and non‐bipyridine based COF‐TfpDaaq were quantified. As shown in Figure 4g and Figure S35, 5,5‐dimethyl‐pyrroline N‐oxide (DMPO) was used as a free‐radical spin‐trapping agent in electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) to measure ⋅OOH and ⋅OH. The ⋅OOH and ⋅OH signal intensity for both COF‐TfpBpy and COF‐TfpDaaq were comparable. However, compared with COF‐TfpDaaq, COF‐TfpBpy produced more H2O2 (Figure 3c). Therefore, it implied that H2O2 from bipyridine based COFs was mainly produced by a 2 e− one‐step redox process; while the H2O2 was produced through a 2 e− two‐steps process via ⋅OOH and ⋅OH intermediate species for non‐bipyridine based COFs. We further carried out a capture experiment of the active species to confirm the above arguments (Figure S36). The addition of benzoquinone (BQ, ⋅OOH scavenger) and tert‐butanol (⋅OH scavenger) did not result in significant effect on the amount of H2O2 generated in the presence of bipyridine based COF‐TfpBpy, AP‐TfbBpy and AP‐TfpBpy; yet the same reagents greatly inhibited the generation of H2O2 in the presence of non‐bipyridine based COF‐TfpDaaq, COF‐TfpBd and COF‐TfpPa. It thus proved the argument that bipyridine site changes the mode of H2O2 generation from a 2 e− two‐steps process to a 2 e− one‐step redox process. As those shown in Figure 4h, under light illumination of bipyridine based COF‐TfpBpy, H2O reacted directly with two holes to form H2O2, whilst O2 reacted directly with two electrons and two protons to form H2O2. The non‐bipyridine based COF‐TfpDaaq obtained H2O2 through intermediates (⋅OOH and ⋅OH) via a 2 e− two‐steps redox process. Further investigations are still required to determine the exact mechanism of the 2 e− one‐step redox process at the bipyridine site.

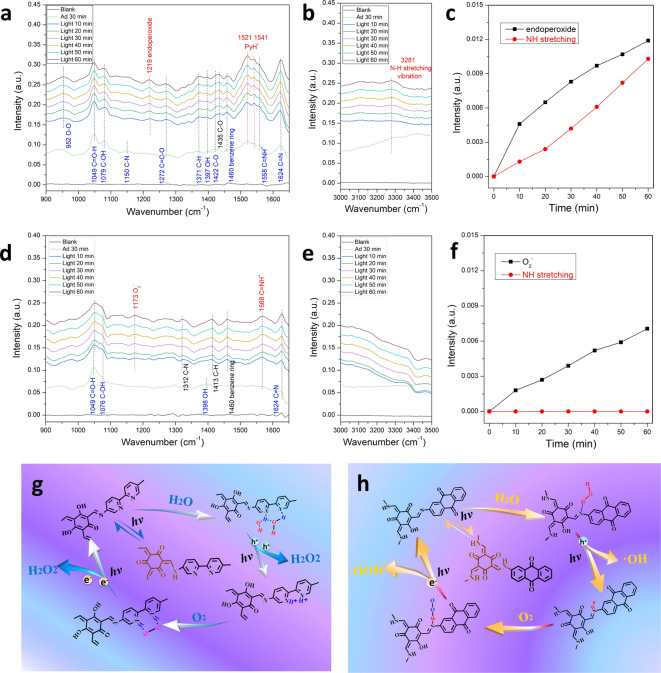

In situ Fourier transform infrared (in situ IR) spectrometry is an effective method to understand the photocatalytic mechanism. Figure 5a–f show the in situ IR spectrometry of COF‐TfpBpy and COF‐TfpDaaq for H2O2 photocatalysis under a continuous steam‐saturated O2 flow. After the system was equilibrated for 30 min, vibrations corresponding to C−OH (1076 cm−1), O−H (1397 cm−1), C−O (1422 cm−1), and C=N (1624 cm−1) for COF‐TfpBpy were apparent. For COF‐TfpDaaq, vibrations corresponding to C−OH (1076 cm−1), O−H (1398 cm−1), and C=N (1624 cm−1) were also apparent.[ 16 , 17 ] However, the intensity of these signals for COF‐TfpDaaq were very low. In contrast, the higher signal intensities indicated the conversion of COF‐TfpBpy from the keto‐amine form into the enol‐imine form under aqueous conditions. [17] The structural changes of COF‐TfpBpy also gave rise to the signals corresponding to C=O−H (1049 cm−1), C−N (1150, 1292 cm−1), C=C−O (1272 cm−1), C−H (1371 cm−1) and the benzene ring (1460 cm−1). More importantly, there were strong vibrations for PyH+ (1521, 1541 cm−1) and C=NH+ (1558 cm−1) in COF‐TfpBpy,[ 16 , 18 ] that were not observed from the spectra of COF‐TfpDaaq. These implied that bipyridine is an important monomer for enol‐to‐keto tautomerism due to the strongly adsorbed H2O molecules on the bipyridine nitrogen of COF‐TfpBpy. On the contrary, Daaq and reported phenyl monomers were unable to result in the structural change from keto‐amine form into enol‐imine form of imine‐based COFs. [19] This may be the origin of H2O2 photocatalysis over COF‐TfpBpy, because water oxidation is the rate‐determining step.

Figure 5.

Photocatalytic mechanism of H2O2 synthesis in the presence of COF‐TfpBpy or COF‐TfpDaaq based on in situ FT‐IR. a) and b) In situ FT‐IR spectrum of COF‐TfpBpy for photosynthetic H2O2 production at 900–1650 cm−1 and 3000–3500 cm−1. c) The peak intensity of endoperoxide intermediate species and NH stretching vibration changes with increasing illumination time. d) and e) In situ FT‐IR spectrum of COF‐TfpBpy for photosynthetic H2O2 production at 900–1650 cm−1 and 3000–3500 cm−1. f) The peak intensity of O2− and NH stretching vibrations changes with increasing illumination time. g) and h) Photocatalytic mechanism of H2O2 synthesis in the presence of COF‐TfpBpy and COF‐TfpDaaq.

Under light irradiation, the signal intensity corresponding to C=N, C−OH and C=NH+ increased, and particularly pronounced signals are also apparent for COF‐TfpDaaq (Figure S37). It indicated that light also induced the transformation of the keto‐amine form into the enol‐imine form.[ 17 , 20 ] Meanwhile, some structural transformation induced infrared vibration have shifted (such as 1422 to 1435 cm−1 for C−O) for COF‐TfpBpy, and new infrared vibration appeared (C−N: 1312 cm−1; C−O: 1413 cm−1; benzene ring: 1460 cm−1) for COF‐TfpDaaq due to the structural transformation accelerating. However, these apparent structural transformations did not affect the H2O adsorption on the bipyridine nitrogen. New infrared vibration signals at 952, 1219 and 3281 cm−1 for COF‐TfpBpy can be attributed to the O−O bonding, endoperoxide intermediate species and the NH stretching vibration, respectively. [21] The intensity of these new infrared vibrations gradually increased along with the increase in illumination time. Combined with the increased vibrations of PyH+ (1521, 1541 cm−1) and the appeared (BPy)(H2O) n clusters (Figure S38), [22] the 2 e− one‐step redox process over COF‐TfpBpy can be summarized as Figure 5g. Initially, the COF‐TfpBpy undergoes light‐induced structural transformation. Two bipyridine nitrogen atoms adsorb two water molecules, and hydrogen bonds are formed between the two water molecules. Photoexcitation leads to the oxidation of the two water molecules to generate H2O2, leaving two protonated pyridine substituents (PyH+). [23] An oxygen molecule is then adsorbed on the PyH+ substituent of COF‐TfpBpy to form an endoperoxide intermediate (N−H−O−O−H−N), which is easily transformed into H2O2 via a selective 2 e− reduction. The enhanced activity of protonated COF‐TfpBpy and its absence of activity in nonaqueous solvents for H2O2 production also support that the initial step is a 2 e− water oxidation (Figure S39). Compared with COF‐TfpBpy, new peaks for COF‐TfpDaaq were apparent at 1173 cm−1 and 1568 cm−1, which corresponded to O2− and C=NH+, respectively.[ 20 , 24 ] O2− is the single electron reduction product from O2, which indicates that H2O2 was photocatalytically produced by a 2 e− two‐steps process with COF‐TfpDaaq. As shown in Figure 5h, the structure of COF‐TfpDaaq also undergoes light‐induced transformation. Then, the nitrogen atom of C=N adsorbs a single water molecule. After photoexcitation, the water molecules are oxidized to generate ⋅OH and protonate the imine (C=NH+). Two ⋅OH radicals can couple to generate one H2O2. A single oxygen molecule can be adsorbed on the C=NH+ of COF‐TfpDaaq to form the O2− intermediate species, and O2− is transformed into ⋅OOH via a single‐electron reduction. Then, the ⋅OOH radical is converted to H2O2 via another one‐electron reduction. The non‐dominant 2 e− two‐steps process of COF‐TfpBpy catalyst is not considered due to the high selectivity of the 2 e− route for photocatalytic H2O2 production.

In order to account for the difference in selectivity, DFT calculation was used to compare the adsorption energies of H2O and O2 on different N sites of COF‐TfpBpy. As shown in Figure S40, O2 cannot adsorb onto the N sites of COF‐TfpBpy without light irradiation. However, the adsorption energy (−0.677 eV) for two H2O molecules onto bipyridine nitrogen atoms was lower than that of one H2O molecule on an imine nitrogen atom (−0.384 eV) or one H2O molecule on a bipyridine nitrogen atom (−0.376 eV). It indicated that the bipyridine site was favorable for simultaneous adsorption of two water molecules to accelerate the 2 e− one‐step WOR under light irradiation. After protonation of the catalyst to C=NH+ or PyH+, O2 can be adsorbed on H sites of C=NH+ or PyH+. The adsorption energy (−2.702 eV) of molecular O2 on bipyridine via the endoperoxide intermediate species was much lower than that of molecular O2 on bipyridine (−1.243 eV) or C=NH+ via the O2− intermediate species (−0.376 eV). It indicates that bipyridine protonation was favorable for O2 adsorption via endoperoxide intermediate species and accelerated the oxygen reduction reaction under light irradiation. The presence of bipyridine in the photocatalyst induced the high selectivity of the 2 e− one‐step route for H2O2 production.

Conclusion

In summary, we reported the crystalline polymer photocatalyst (COF‐TfpBpy) for the efficient photocatalytic production of H2O2 without sacrificial reagents and stabilizers. The photocatalytic H2O2 solution can be directly used in the pollutant removal and water disinfection. Our investigations revealed that protonation of the nitrogen atom in the bipyridine monomer facilitated the formation of suitable intermediates for H2O2 formation via 2 e− one‐step redox reactions. The resulting bipyridine‐based polymer photocatalyst exhibited excellent activity for H2O2 production with 100 % atom utilization efficiency. Our findings provide important insights into the design and synthesis of bipyridine‐based polymer photocatalysts at the molecular level, and could be an excellent starting point to develop superior H2O2 photocatalysts.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51872147, 22136003), the 111 Project (D20015), and the outstanding young and middle‐aged science and technology innovation teams, Ministry of Education, Hubei province, China (T2020004), Australian Research Council (ARC) through Future Fellowship (FT210100298, FT210100806), Discovery Project (DP220100603), Linkage Project (LP210100467), and Industrial Transformation Training Centre (IC180100005) schemes, CSIRO Energy Centre and Kick‐Start Project. The Study Melbourne Research Partnerships program has been made possible by funding from the Victorian Government through Study Melbourne. Open access publishing facilitated by RMIT University, as part of the Wiley ‐ RMIT University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

M. Kou, Y. Wang, Y. Xu, L. Ye, Y. Huang, B. Jia, H. Li, J. Ren, Y. Deng, J. Chen, Y. Zhou, K. Lei, L. Wang, W. Liu, H. Huang, T. Ma, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202200413; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202200413.

Contributor Information

Prof. Liqun Ye, Email: lqye@ctgu.edu.cn.

Prof. Tianyi Ma, Email: tianyi.ma@rmit.edu.au.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Miklos D. B., Remy C., Jekel M., Linden K. G., Drewes J. E., Hübner U., Water Res. 2018, 139, 118–131; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Chuang Y. H., Chen S., Chinn C. J., Mitch W. A., Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 13859–13868; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Hodges B. C., Cates E. L., Kim J. H., Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 642–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sun P., Tyree C., Huang C. H., Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4448–4458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xia C., Xia Y., Zhu P., Fan L., Wang H. H., Science 2019, 366, 226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hou H. L., Zeng X. K., Zhang X. W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 17356–17376; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 17508–17529. [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Kofuji Y., Isobe Y., Shiraishi Y., Sakamoto H., Tanaka S., Ichikawa S., Hirai T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 10019–10025; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Shiraishi Y., Takii T., Hagi T., Mori S., Kofuji Y., Kitagawa Y., Tanaka S., Ichikawa S., Hirai T., Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 985–993; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Chen L., Wang L., Wan Y. Y., Zhang Y., Qi Z. M., Wu X. J., Xu H. X., Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1904433; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5d. Krishnaraj C., Jena H. S., Bourda L., Laemont A., Pachfule P., Roeser J., Chandran C. V., Borgmans S., Rogge S. M. J., Leus K., Stevens C. V., Martens J. A., Speybroeck V. V., Breynaert E., Thomas A., Voort P. V. D., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 142, 20107–20116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Sachs M., Sprick R. S., Pearce D., Hillman S. A. J., Monti A., Guilbert A. A. Y., Brownbill N. J., Dimitrov S., Shi X., Blanc F., Zwijnenburg M. A., Nelson J., Durrant J. R., Cooper A. I., Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4968; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Bai Y., Wilbraham L., Slater B. J., Zwijnenburg M. A., Sprick R. S., Cooper A. I., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 9063–9071; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Liu L., Gao M. Y., Yang H., Wang X., Li X., Cooper A. I., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 19287–19293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Shiraishi Y., Kanazawa S., Kofuji Y., Sakamoto H., Ichikawa S., Tanaka S., Hirai T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 13454–13459; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 13672–13677; [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Wu S., Yu H., Chen S., Quan X., ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 24, 14380–14389; [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Zhang T., Schilling W., Khan S. U., Vincent Ching H. Y., Lu C., Chen J., Jaworski A., Barcaro G., Monti S., Wael K. D., Slabon A., Das S., ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 14087–14101. [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Kofuji Y., Ohkita S., Shiraishi Y., Sakamoto H., Tanaka S., Ichikawa S., Hirai T., ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7021–7029; [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Chu C. H., Zhu Q. H., Pan Z. H., Gupta S., Huang D. H., Du Y. H., Weon S., Wu Y. S., Muhich C., Stavitski E., Domen K., Kim J. H., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 6376–6382; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8c. Zhang P., Tong Y. W., Liu Y., Vequizo J. J. M., Sun H. W., Yang C., Yamakata A., Fan F., Lin W., Wang X. C., Choi W. Y., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 16209–16217; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 16343–16351. [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Teng Z. Y., Zhang Q. T., Yang H. B., Kato K., Yang W. J., Lu Y. R., Liu S. X., Wang C. Y., Yamakata A., Su C. L., Liu B., Ohno T., Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 374–384; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Shiraishi Y., Ueda Y., Soramoto A., Hinokuma S., Hirai T., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang N., Wang P., Jiang D. L., Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 6068. [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Chen R. F., Wang Y., Ma Y., Mal A., Gao X. Y., Gao L., Qiao L. J., Li X. B., Wu L. Z., Wang C., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1354; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Banerjee T., Gottschling K., Savasc G., Ochsenfeld C., Lotsch B. V., ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 400–409; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11c. Liu W. B., Li X. K., Wang C. M., Pan H. H., Liu W. P., Wang K., Zeng Q. D., Wang R. M., Jiang J. Z., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 17431–17440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reijnders L., Huijbregts M., Biofuels for Road Transport: A Seed to Wheel Perspective, Springer Science & Business Media, New York, 2008, pp. 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Tian Q., Jing L., Ye S., Liu J., Chen R., Small 2021, 17, 2103224; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Shiraishi Y., Hagi T., Matsumoto M., Tanaka S., Ichikawa S., Hirai T., Commun. Chem. 2020, 3, 169; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13c. Shiraishi Y., Matsumoto M., Ichikawa S., Tanaka S., Hirai T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 12590–12599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Fu S., Yao S., Guo S., Guo G. C., Yuan W., Lu T. B., Zhang Z. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20792–20801; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Tian N., Zhang Y. H., Li X. W., Xiao K., Du X., Dong F., Waterhouse G. I. N., Zhang T. R., Huang H. W., Nano Energy 2017, 38, 72–81; [Google Scholar]

- 14c. Zhang X., Ma P., Wang C., Gan L. Y., Chen X., Zhang P., Wang Y., Li H., Wang L., Zhou X., Zheng K., Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 830–842. [Google Scholar]

- 15.

- 15a. Zhao Y. J., Liu Y., Cao J. J., Wang H., Shao M. W., Huang H., Liu Y., Kang Z. H., Appl. Catal. B 2020, 278, 119289; [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Cao J. J., Wang H., Zhao Y. Y., Liu Y., Wu Q. Y., Huang H., Shao M. W., Liu Y., Kang Z. H., J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 3701–3707. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simons W. W., The sadtler handbook of infrared spectra, Vol. 16, Heyden and Son, London, 1978, 21A. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ning G. H., Chen Z. X., Gao Q., Tang W., Chen Z. X., Liu C. B., Tian B. B., Li X., Loh K. P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8897–8904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 18a. Castellà-Ventura M., Akacem Y., Kassab E., J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 19045–19054; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Dunwell M., Yan Y., Xu B., ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 5410–5419. [Google Scholar]

- 19.

- 19a. Kandambeth S., Mallick A., Lukose B., Mane M. V., Heine T., Banerjee R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 19524–19527; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Chong J. H., Sauer M., Patrick B. O., MacLachlan M. J., Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 3823–3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.

- 20a. Kodera Y., Wakisaka A., Ukegawa K., Murayama T., Ozawa T., YosHrromi S., J. Jpn. Soc. Colour Mater. 1992, 65, 294–297; [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Taneda M., Kodama Y., Eda Y., Koyama H., Kawato T., Chem. Lett. 2007, 36, 1410–1411; [Google Scholar]

- 20c. Koshima H., Takechi K., Uchimoto H., Shirob M., Hashizume D., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11423–11425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.

- 21a. Burks R. M., Hage D. S., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 395, 301–313; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Schulte-Ladbeck R., Edelmann A., Quintás G., Lendl B., Karst U., Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 8150–8155; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21c. Buttigieg G. A., Knight A. K., Denson S., Pommier C., Denton M. B., Forensic Sci. Int. 2003, 135, 53–59; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21d. Pacheco-Londoño L. C., Castro-Suarez J. R., Hernández-Rivera S. P., Adv. Opt. Technol. 2013, 532670; [Google Scholar]

- 21e. Brauer B., Dubnikova F., Zeiri Y., Kosloff R., Gerber R. B., Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2008, 71, 1438–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Feng J. Y., Lee Y. P., Witek H. A., Hsu P. J., Kuo J. L., Ebata T., J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 7489–7501; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Feng J. Y., Lee Y. P., Witek H. A., Ebata T.i, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 4936–4943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang J., Acharjya A., Ye M. Y., Rabeah J., Li S., Kochovski Z., Youk S., Roeser J., Grüneberg J., Penschke C., Schwarze M., Wang T. Y., Lu Y., Krol R. V. D., Oschatz M., Schomäcker R., Saalfrank P., Thomas A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 19797–19803; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 19950–19956. [Google Scholar]

- 24.

- 24a. Shao M. H., Liu P., Adzic R. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 7408–7409; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24b. Wan H. L., Zhou X. P., Weng W. Z., Long R. Q., Chao Z. S., Zhang W. D., Chen M. S., Luo J. Z., Zhou S. Q., Catal. Today 1999, 51, 161–175; [Google Scholar]

- 24c. Hu C., Hu Y., Fan C., Yang L., Zhang Y., Li H., Xie W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 19774–19778; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 19927–19931. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.