Abstract

Ubiquitin (Ub) binding domains embedded in intracellular proteins act as readers of the complex Ub code and contribute to regulation of numerous eukaryotic processes. Ub-interacting motifs (UIMs) are short α-helical modular recognition elements whose role in controlling proteostasis and signal transduction has been poorly investigated. Moreover, impaired or aberrant activity of UIM-containing proteins has been implicated in numerous diseases but targeting modular recognition elements in proteins remains a major challenge. To overcome this limitation, we developed Ub variants (UbVs) that bind to 42 UIMs in the human proteome with high affinity and specificity. Structural analysis of a UbV:UIM complex revealed the molecular determinants of enhanced affinity and specificity. Furthermore, we showed that a UbV targeting a UIM in the cancer-associated Ub-specific protease 28 potently inhibited catalytic activity. Our work demonstrates the versatility of UbVs to target short α-helical ubiquitin receptors with high affinity and specificity. Moreover, the UbVs provide a toolkit to investigate the role of UIMs in regulating and transducing ubiquitin signals and establish a general strategy for the systematic development of probes for Ub-binding domains.

Keywords: ubiquitin, phage display, protein engineering, ubiquitin-interacting motifs

Introduction

The ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) plays a pivotal role in the timely and targeted degradation of cellular proteins upon their covalent but reversible modification with the small protein ubiquitin (Ub). In addition to marking proteins for disposal, the attachment of Ub to protein substrates (ubiquitination) is key for regulating the amplitude and timing of signal transduction pathways 1–4. Consequently, aberrant ubiquitination is implicated in many diseases, including development defects, autoimmune disorders, and cancer 5.

Ubiquitination involves the coordinated activity of an E1-E2-E3 enzyme cascade, which results in the conjugation of ubiquitin to N-termini or lysine residues of cellular proteins, and subsequently, attachment of additional Ub moieties to the N-terminus or one of seven lysines in conjugated Ub itself to form homotypic, heterotypic, or branched Ub chains. Ub chains are further edited and disassembled by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that remove Ub molecules from protein substrates, thus controlling protein fate 6. Different Ub chain topologies confer distinct localization and function, as for example, K11-linked Ub chains control cell progression through mitosis, whereas K48-linked Ub chains drive proteosomal degradation 7–9.

To a large extent, the signalling function of the Ub code is mediated by the interaction of Ub-conjugated proteins with Ub-binding domains (UBDs) embedded in a variety of proteins with diverse structure, function and localization 10–12. UBDs typically bind Ub weakly, and virtually all known interactions are mediated through a common face on Ub that encompasses a hydrophobic patch centered on Ile44 11,12. Nonetheless, dynamic NMR studies have shown that interactions between Ub and UBDs are highly diverse and are regulated not only by the structure of the UBD, but also, by the conformational dynamics of Ub and Ub chains 13.

To date, more than 20 families of diverse UBDs with different folds and binding modes have been described 10–12, and the simplest of these is the family of Ub interacting motifs (UIMs), which consist of a single amphipathic α-helix of ~20 residues that interacts with Ub through a conserved face 14,15. Interactions between Ub and UIMs are typically very weak (KD = 0.1–1 mM) 16, but nonetheless, they have been implicated in many cellular functions, including proteosomal degradation, DNA-damage repair, and endocytosis 17–19. Recently, UIMs have been shown to interact with the Ub-like protein autophagy-related protein 8 (Atg8), suggesting connections between vesicular trafficking and autophagy, and a potential role for UIMs in regulating proteostasis 20.

UIMs are often found in tandem repetitions, which result in co-operative and tight binding to Ub chains 21,22. Moreover, the length and flexibility of the intervening regions between UIMs can dictate the selectivity of UIMs for particular Ub chains 23–25, and consequently, regulation of the localization and trafficking of proteins. Protein mislocalization and accumulation have been implicated in many cancers, but the role of UIM-containing proteins in pathogenesis is still poorly defined.

Given the importance of UIM-containing proteins in normal and abnormal cellular functions, there is a need for molecular probes that can interact with UIMs specifically in cells. Unfortunately, the minimalist structure of UIMs precludes the development of small-molecule probes. To address this need, we sought to develop a comprehensive toolkit of specific affinity reagents for the predicted family of UIMs in the human proteome, using a ubiquitin variant (UbV) technology that we applied previously to develop intracellular probes of DUBs 26–29, E2 conjugating enzymes, E3 ligases 30,31 and their complexes 32,33, and a UIM from yeast 34.

We used phage display to develop UbVs targeting 42 of 60 predicted UIMs in the human proteome, and many of these bound with high affinity and specificity to their cognate targets. Structural studies of an optimized UbV bound to its cognate UIM revealed the molecular basis for enhanced affinity and specificity. Moreover, a UbV targeting a UIM embedded in the cancer-associated DUB Ub-specific protease 28 (USP28) acted as an inhibitor of catalytic function in vitro and in cells, showing that UbVs can be used to elucidate UIM functions and aid the identification of potential drug targets.

Results

A panel of e UIMs in the human proteome

Canonical UIMs match the following consensus: Ac-Ac-Ac-x-x-φ-x-x-Ala-φ-x-x-Ser-z-x-Ac, where Ac is an acidic residue, z is a bulky hydrophobic or polar residue with aliphatic content, and φ is a hydrophobic residue 19,35,36. However, other physiologically relevant non-canonical UIMs able to interact with Ub have been observed in nature 35,37–39, suggesting that UIMs can tolerate sequence variations.

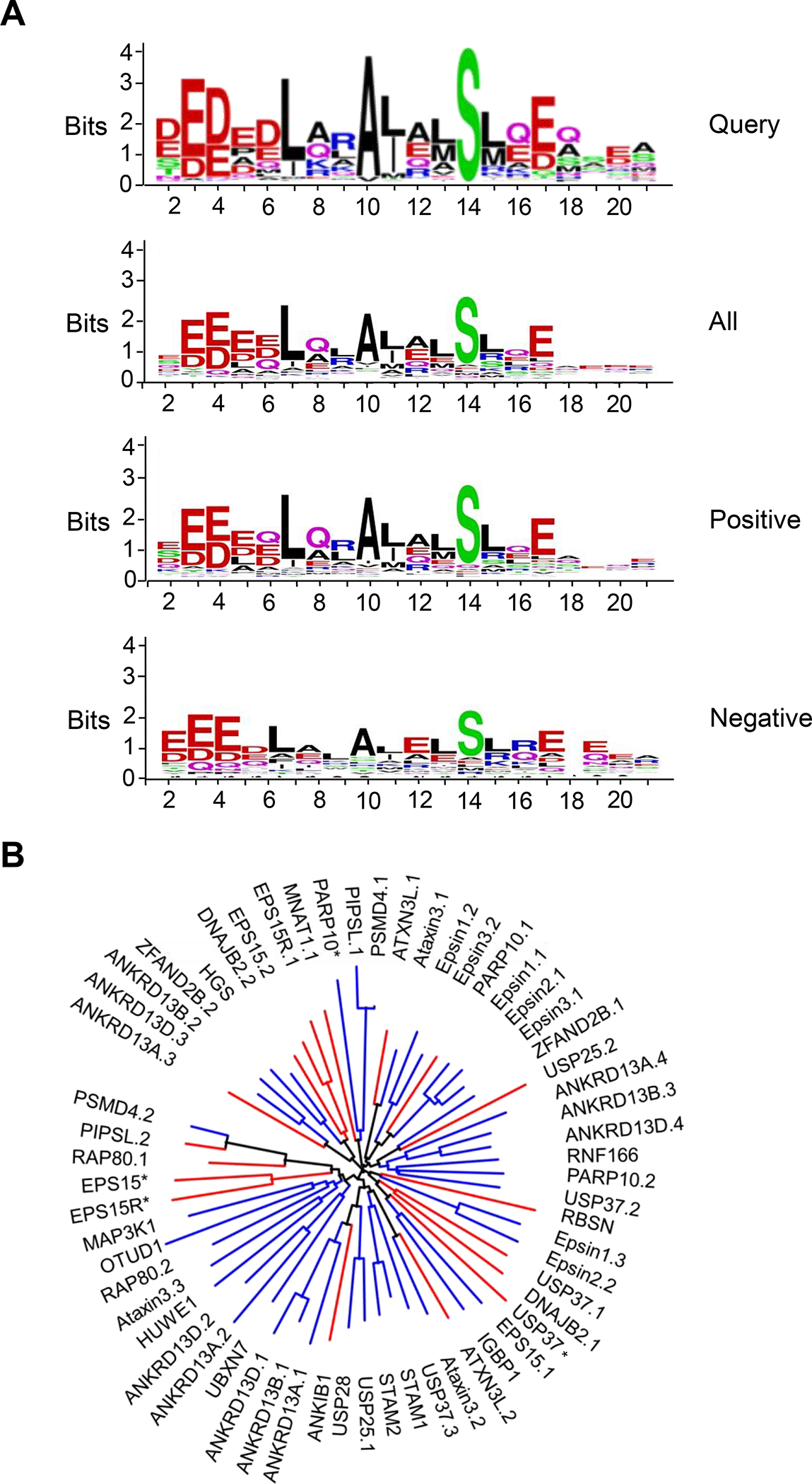

To assemble a panel of human UIMs, we searched the Pfam database 40 for non-redundant sequences matching the UIM consensus across 950 species, and created a logo representing both sequence alignments and profile hidden Markov models 41. The obtained query sequence logo (Figure 1A) was in good agreement with previously reported UIM consensus sequences 19,35 and it was used to query human proteins in the UniProt and SMART databases 42,43. We further refined our set of UIMs by additional literature searching, and by considering as UIMs only those sequences that were found in at least two databases and were good matches to the consensus sequence as well as the HHM profile. In total, we identified 60 UIMs embedded in 31 human proteins characterized by a wide variety of architectures and functions, including E3 Ub ligases (HUWE1, RNF166), DUBs (USP25, USP28, USP37, OTUD1), endocytic adaptor proteins (EPS15, Epsins) and chaperones (DNAJB2) (Table 1 and Supplementary File 1).

Figure 1. Identification of UIM sequences in the human proteome.

(A) Sequence logos of the non-redundant sequences derived from 950 species (query), all 60 human UIMs used in this study (all), 42 UIMs for which isolation of UbVs was successful (positive), and 18 UIMs that did not yield UbVs (negative). Sequence logos were generated using the WebLogo online tool 78. (B) Un-rooted phylogenetic tree of UIM sequences used in this study. The tree was drawn using the interactive tree of life online tool 79. Blue branches show UIMs for which UbVs were selected, whereas red branches display UIMs which did not yield UbVs. See Table 1 for UIM sequences.

Table 1.

Sequences of UlMs in the human proteome.

| Gene name | UniProt accession code | Residues | Sequence | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | |||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |||

| Consensus | x | x | Ac | Ac | Ac | x | φ | x | x | A | φ | x | φ | S | z | x | Ac | x | x | x | x | ||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKRD13D.3 | Q6ZTN6 | 477–496 | - | S | F | E | E | Q | L | R | L | A | L | E | L | S | S | R | E | Q | E | E | R |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKRD13B.2 | Q86YJ7 | 585–604 | - | S | Y | D | E | Q | L | R | L | A | M | E | L | S | A | Q | E | Q | E | E | R |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ZFAND2B.2 | Q8WV99 | 221–240 | - | Q | E | E | E | D | L | A | L | A | Q | A | L | S | A | S | E | A | E | Y | Q |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| HGS | O14964 | 258–277 | - | Q | E | E | E | E | L | Q | L | A | L | A | L | S | Q | S | E | A | E | E | K |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PARP10* | Q53GL7 | 729–748 | - | Q | D | V | E | E | L | D | R | A | L | R | A | A | L | E | V | H | V | Q | E |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PIPSL.1 | A2A3N6 | 696–715 | - | S | A | D | P | E | L | A | L | V | L | R | V | F | M | E | E | Q | R | Q | R |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PSMD4.1 | P55036 | 211–230 | - | S | A | D | P | E | L | A | L | A | L | R | V | S | M | E | E | Q | R | Q | R |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ataxin3.1 | P54252 | 224–243 | - | E | D | E | E | D | L | Q | R | A | L | A | L | S | R | Q | E | I | D | M | E |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Epsin1.2 | Q9Y6I3 | 208–227 | - | E | D | D | A | Q | L | Q | L | A | L | S | L | S | R | E | E | H | D | K | E |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Epsin3.2 | Q9H201 | 236–255 | - | D | E | D | L | Q | L | Q | L | A | L | R | L | S | R | Q | E | H | E | K | E |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Epsin1.1 | Q9Y6I3 | 183–202 | - | E | E | E | L | Q | L | Q | L | A | L | A | M | S | K | E | E | A | D | Q | P |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Epsin2.1 | O95208 | 275–294 | - | E | E | E | L | Q | L | Q | L | A | L | A | M | S | R | E | V | A | E | Q | E |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Epsin3.1 | Q9H201 | 209–228 | - | E | E | E | L | Q | L | Q | L | A | L | A | M | S | R | E | E | A | E | K | P |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ZFAND2B.1 | Q8WV99 | 197–216 | - | S | E | D | E | A | L | Q | R | A | L | E | M | S | L | A | E | T | K | P | Q |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKRD13A.4 | Q8IZ07 | 574–590 | - | E | E | E | A | E | L | Q | Q | V | L | Q | L | S | L | T | D | K | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKRD13B.3 | Q86YJ7 | 610–626 | - | Q | E | E | E | E | L | E | R | I | L | R | L | S | L | T | E | Q | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKRD13D.4 | Q6ZTN6 | 502–518 | - | Q | E | E | E | D | L | Q | R | I | L | Q | L | S | L | T | E | H | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| RNF166 | Q96A37 | 221–237 | - | D | E | E | A | A | F | Q | A | A | L | A | L | S | L | S | E | N | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PARP10.2 | Q53GL7 | 673–690 | Q | E | E | A | A | A | L | R | Q | A | L | T | L | S | L | L | E | Q | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| USP37.2 | Q86T82 | 806–825 | - | R | E | E | Q | E | L | Q | Q | A | L | A | Q | S | L | Q | E | Q | E | A | W |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Epsin1.3 | Q9Y6I3 | 233–252 | - | G | D | D | L | R | L | Q | M | A | I | E | E | S | K | R | E | T | G | G | K |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Epsin2.2 | O95208 | 300–319 | - | G | D | D | L | R | L | Q | M | A | L | E | E | S | R | R | D | T | V | K | I |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| EPS15.1 | P42566 | 851–870 | - | S | E | E | D | M | I | E | W | A | K | R | E | S | E | R | E | E | E | Q | R |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| IGBP1 | P78318 | 46–60 | - | L | D | L | L | E | K | A | A | E | M | L | S | Q | L | D | - | - | - | - | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ataxin3.2 | P54252 | 244–263 | - | D | E | E | A | D | L | R | R | A | I | Q | L | S | M | Q | G | S | S | R | N |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| USP37.3 | Q86T82 | 828–847 | - | K | E | D | D | D | L | K | R | A | T | E | L | S | L | Q | E | F | N | N | S |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| STAM | Q92783 | 171–190 | - | K | E | E | E | D | L | A | K | A | I | E | L | S | L | K | E | Q | R | Q | Q |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| STAM2 | O75886 | 165–184 | - | K | E | D | E | D | I | A | K | A | I | E | L | S | L | Q | E | Q | K | Q | Q |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| USP25.1 | Q9UHP3 | 97–116 | - | D | D | K | D | D | L | Q | R | A | I | A | L | S | L | A | E | S | N | R | A |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| USP28 | Q96RU2 | 97–116 | - | D | N | K | D | D | L | Q | A | A | I | A | L | S | L | L | E | S | P | K | I |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKRD13A.1 | Q8IZ07 | 483–503 | D | E | D | Y | E | I | M | Q | F | A | I | Q | Q | S | L | L | E | S | S | R | S |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKRD13B.1 | Q86YJ7 | 503–522 | - | D | D | D | D | L | L | Q | F | A | I | Q | Q | S | L | L | E | A | G | S | E |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKRD13D.1 | Q6ZTN6 | 395–414 | - | E | D | D | D | L | L | Q | F | A | I | Q | Q | S | L | L | E | A | G | T | E |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| UBXN7 | O94888 | 285–304 | - | S | E | D | S | Q | L | E | A | A | I | R | A | S | L | Q | E | T | H | F | D |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKRD13A.2 | Q8IZ07 | 519–538 | - | T | Y | D | A | Q | Y | E | R | A | I | Q | E | S | L | L | T | S | T | E | G |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKRD13D.2 | Q6ZTN6 | 441–460 | - | E | E | Q | L | Q | L | E | R | A | L | Q | E | S | L | Q | L | S | T | E | P |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| HUWE1 | Q7Z6Z7 | 1370–1389 | - | S | E | E | D | Q | M | M | R | A | I | A | M | S | L | G | Q | D | I | P | M |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ataxin3.3 | P54252 | 331–349 | - | S | E | E | D | M | L | Q | A | A | V | T | M | S | L | E | T | V | R | N | D |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| RAP80.2 | Q96RL1 | 105–124 | E | E | E | E | E | L | L | R | K | A | I | A | E | S | L | N | S | C | R | P | S |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| OTUD1 | Q5VV17 | 457–476 | - | - | - | K | R | D | E | E | L | A | K | S | M | A | I | S | L | S | K | M | Y |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| MAP3K1 | Q13233 | 1184–1202 | - | E | E | E | E | A | L | A | I | A | M | A | M | S | A | S | Q | D | A | L | P |

| PSMD4.2 | P55036 | 282–301 | - | T | E | E | E | Q | I | A | Y | A | M | Q | M | S | L | Q | G | A | E | F | G |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKRD13A.3 | Q8IZ07 | 549–569 | - | R | F | D | N | D | L | Q | L | A | M | E | L | S | A | K | E | L | E | E | W |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| DNAJB2.2 | P25686 | 250–269 | - | S | E | D | E | D | L | Q | L | A | M | A | Y | S | L | S | E | M | E | A | A |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| EPS15.2 | P42566 | 877–896 | - | Q | E | Q | E | D | L | E | L | A | I | A | L | S | K | S | E | I | S | E | A |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| EPS15R.1 | Q9UBC2-2 | 752–771 | - | N | E | E | Q | Q | L | A | W | A | K | R | E | S | E | K | A | E | Q | E | R |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| MNAT1 | P51948 | 142–161 | - | R | E | Q | E | E | L | E | E | A | L | E | V | E | R | Q | E | N | E | Q | R |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ATXN3L.1 | Q9H3M9 | 224–243 | - | Q | D | E | E | D | F | Q | R | A | L | E | L | S | R | Q | E | T | N | R | E |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PARP10.1 | Q53GL7 | 650–667 | L | E | E | E | A | A | L | Q | L | A | L | H | R | S | L | E | P | Q | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| USP25.2 | Q9UHP3 | 123–140 | - | - | - | - | T | D | E | E | Q | A | I | S | R | V | L | E | A | S | I | A | E |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| RBSN | Q9H1K0 | 496–515 | - | Y | D | Q | Q | Q | T | E | K | A | I | E | L | S | R | R | Q | A | E | E | E |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| USP37.1 | Q86T82 | 704–723 | - | S | E | E | E | L | L | A | A | V | L | E | I | S | K | R | D | A | S | P | S |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| DNAJB2.1 | P25686 | 210–226 | - | G | V | P | D | D | L | A | L | G | L | E | L | S | R | R | E | Q | Q | P | S |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| USP37* | Q86T82 | 651–670 | - | D | S | E | D | E | L | K | R | S | V | A | L | S | Q | R | L | C | E | M | L |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ATXN3L.2 | Q9H3M9 | 244–258 | - | R | E | D | E | H | L | R | S | T | I | E | L | S | M | Q | G | S | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ANKIB1 | Q9P2G1 | 857–870 | - | E | D | D | P | N | I | L | L | A | I | Q | L | S | L | Q | E | S | G | L | A |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| EPS15* | P42566 | 442–462 | - | T | Y | E | E | E | L | A | K | A | R | E | E | L | S | R | L | Q | Q | E | T |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| EPS15R* | Q9UBC2-2 | 778–797 | - | Q | E | Q | E | D | L | E | L | A | I | A | L | S | K | A | D | M | P | A | A |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| RAP80.1 | Q96RL1 | 80–99 | M | T | E | E | E | Q | F | A | L | A | L | K | M | S | E | Q | E | A | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PIPSL.2 | A2A3N6 | 766–783 | M | T | E | E | E | K | I | V | C | A | M | Q | M | S | L | Q | G | A | - | - | - |

The sequences of human UlMs are aligned and clustered based on sequence similarity (see Figure 1B for phylogenetic tree), and residues matching the consensus sequence are shaded in grey. Dashes indicate gaps in the alignment, x denotes any residue, Ac denotes acidic residues, φ denotes hydrophobic amino acids, and z denotes bulky hydrophobic residues or polar residues with high aliphatic content. For proteins containing multiple UlMs, the number following the decimal in the gene name indicates the numerical order in the protein (e.g. ANKRD13D.3 denotes the third UlM in ANKRD13D). Entries labelled with an asterisk refer to sequences that were found only in the Smart database but are good matches to the UlM consensus sequence. Sequences that were successful or unsuccessful in generating UbVs from phage-displayed libraries are shown above or below the dashed line, respectively.

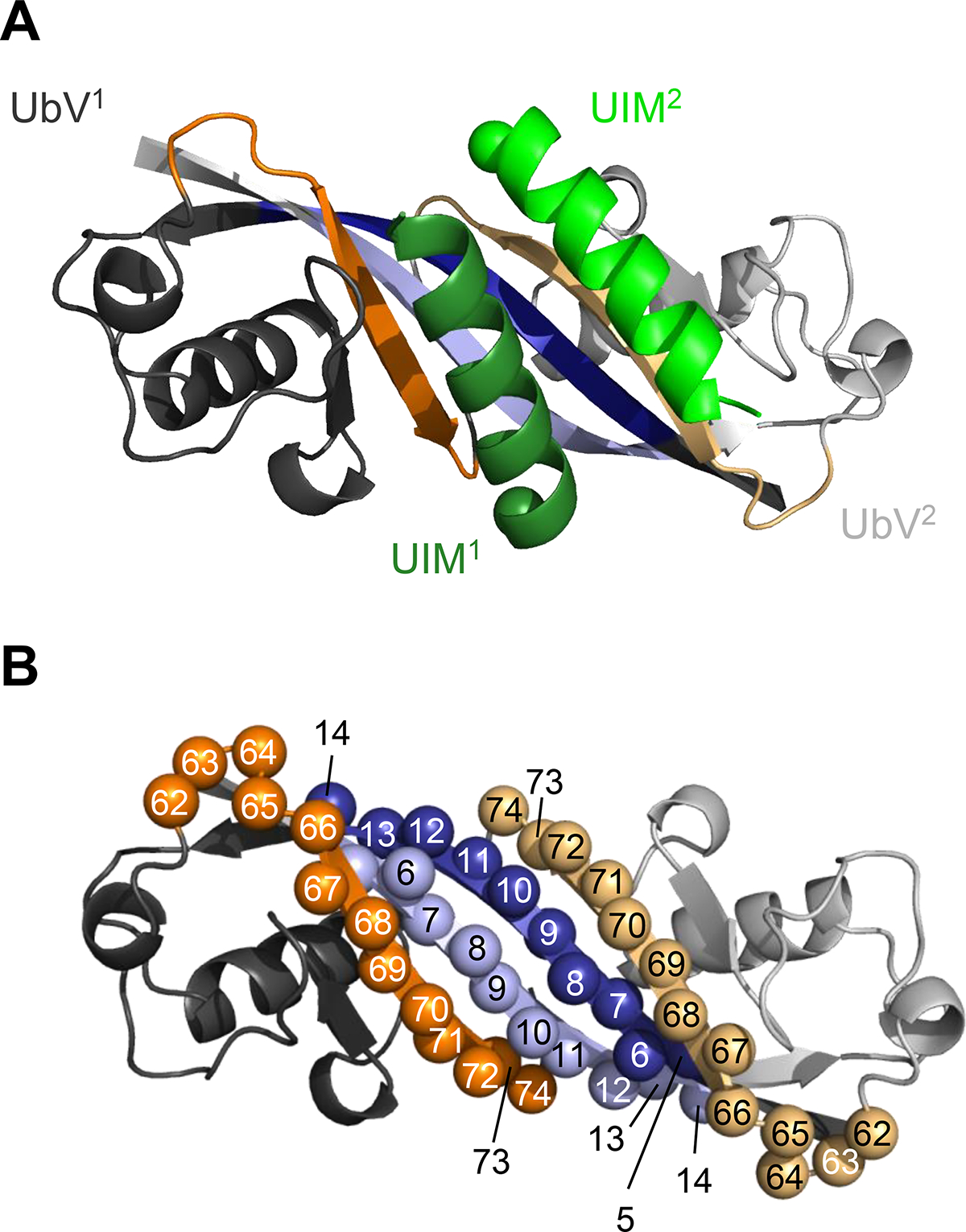

Design and construction of a UIM-targeting UbV library

To design and construct a phage-displayed UIM-targeting UbV (UtU) library, we analyzed the previously reported structure of UbV.v27.1 in complex with a peptide representing the UIM of the yeast protein vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 27 (Vps27) 34,36,44. UbV.v27.1 forms a non-covalent dimer as a consequence of a swap between the β1-strands of two UbV monomers 44, and consequently, binds the UIM with a 2:2 stoichiometry (Figure 2). Binding results in the burial of 850 and 545 Å2 of surface area on each UIM peptide and the UbV.v27.1, respectively, and each peptide sits on top of the β1-strand from one UbV monomer and the β3-strand from the second UbV monomer. Thus, we targeted for diversification continuous stretches of 10 positions in strand β1 (positions 5–14) and 9 positions in strand β3 (positions 66–74). The C-terminal region of the UIM peptide is disordered in the structure, and thus, we also diversified 4 positions preceding strand β3 (positions 62–65), as this region is close to the UIM C-terminus. In total, we subjected 23 positions to a “soft randomization” strategy with degenerate codons that encoded approximately 50% wild-type sequence and 50% mutations at each diversified position (Figure 2). The resulting library UtU contained 1.7 × 1010 unique members.

Figure 2. Design of a UbV library targeting UIMs.

(A) Structure of the dimeric UbV.v27.1 in complex with two copies of the UIM from Vps27 (PDB: 6NJG). The first and second UbV monomer (UbV1 and UbV2, respectively) are in dark or light color, respectively. The β1-strand and β3-strand are colored blue or orange, respectively, and other regions are colored grey. The first and second UIM helices (UIM1 and UIM2, respectively) are colored dark or light green, respectively, and N-termini are depicted as spheres. (B) Design of library UtU. The UbV.v27.1 dimer is colored as in (A) and positions that were diversified in the library are shown as spheres labeled with the position number.

Selection and characterization of UIM-binding UbVs

The 60 UIMs were purified from Escherichia coli as recombinant proteins consisting of a UIM fused to the C-terminus of glutathione-S-transferase (GST), and the fusion proteins were used as baits for binding selections with phage pools representing the library UtU. Positive binding UbV-phage were defined by phage ELISA as those that exhibited at least 10-fold higher binding signal for their cognate target compared with GST. The selections yielded at least one positive UbV for 42 of the 60 UIMs, and in total, 138 unique UbVs were obtained (Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary File 1).

To determine whether there were differences between the UIMs that were positive or negative for selecting binding UbVs, we first determined the average number of matches at the 10 positions that were used to define a UIM consensus (Table 1, grey shaded positions). The mean of the matches to the consensus across the 10 positions was 8.0 or 7.1 for the 42 positive or 18 negative sequences, respectively. To explore position-specific differences, we compared sequence logos derived from all 60 sequences, the 42 positive sequences and the 18 negative sequences (Figure 1A). As expected, all three logos were highly similar to one other and to the query logo, but there were significant differences at some positions. In particular, at the three positions in the query logo showing the highest conservation (Leu7, Ala10, Ser14), the positive sequence logo showed a higher match to the consensus than did the negative sequence logo. Moreover, at three other positions that showed conservation in the query logo (Arg9, Leu11, Glu17), we observed stronger conservation in the positive sequence logo compared with the negative sequence logo. At three additional positions, the most preferred sequence differed, with the positive sequences preferring Gln8, Ala12 and Gln16 and the negative sequences preferring Ala8, Glu12 and Arg16. We also aligned the 60 UIMs based on their sequence homology and assembled them in an unrooted phylogenetic tree (Figure 1B). Analysis of the phylogenetic tree revealed that among the 18 UIMs that did not yield UbVs, 11 clustered into three distinct clades, suggesting that at least some of the negative sequences had a larger degree of similarity than the positive sequences. Taken together, these results showed that the UIM sequences that yielded UbVs were more similar to each other (Figure 1B), to the query logo (Figure 1A) and to the UIM consensus motif (Table 1) compared with the UIM sequences that did not yield UbVs, but the similarities and differences were distributed across many positions.

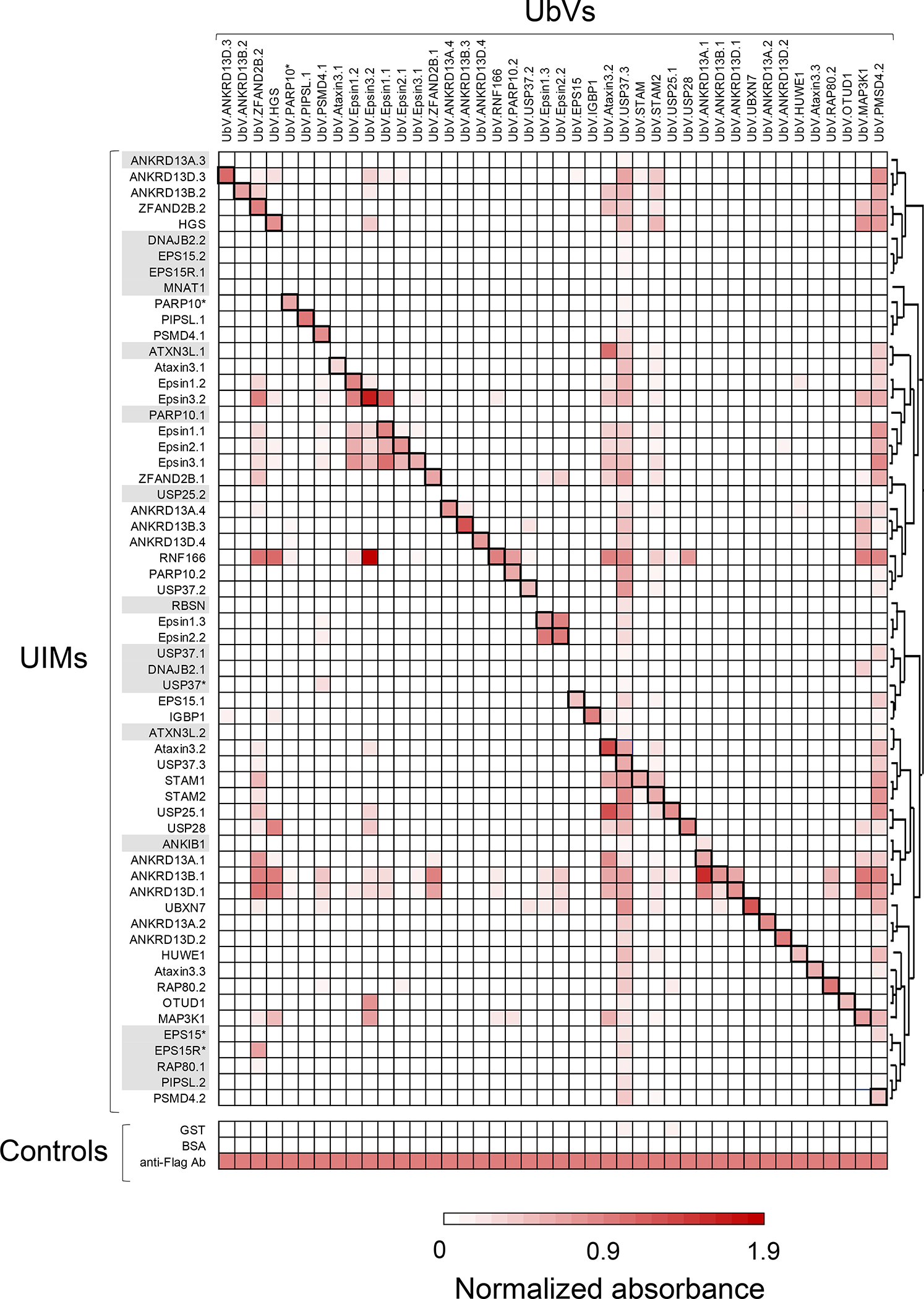

Specificity of the UbV panel was assessed comprehensively by assaying binding of each of the 138 phage-displayed UbVs against all 60 UIMs by phage ELISA (Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary File 2). Based on this pairwise analysis of 8,280 interactions between UbVs and UIMs, we identified the most selective UbV for each of the 42 UIMs that were successful in selections (Table 2 and Supplementary File 1) and the specificity of each UbV across the set of 60 UIMs was depicted as a heat map (Figure 3).

Table 2.

The most specific UbVs selected for binding to human UlMs.

| UbV | Sequence | IC50 (nM) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | a | b | ||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||

| Ub.wt | V | K | T | L | T | G | K | T | I | T | Q | K | E | S | T | L | H | L | V | L | R | L | R | G | G | * | * | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ANKRD13D.3 | - | T | I | V | S | - | F | - | - | - | - | N | T | G | - | V | A | - | - | - | - | H | - | S | L | R | A | 35 ± 5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ANKRD13B.2 | - | Y | - | - | - | A | - | N | R | - | - | R | - | - | N | - | L | - | - | - | - | P | S | S | L | R | A | 730 ± 80 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ZFAND2B.2 | - | - | I | - | A | - | - | - | T | - | K | - | K | - | A | V | Y | V | A | - | - | - | G | S | L | R | A | 320 ± 30 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.HGS | - | - | - | - | - | M | E | - | M | - | - | - | K | - | I | - | Y | R | - | - | - | - | K | S | L | R | A | 10 ± 2 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.PARP10* | - | R | A | I | A | W | N | I | F | I | - | N | K | - | A | - | Y | - | G | - | S | V | K | S | L | R | A | 90 ± 20 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.PIPSL1 | - | P | I | - | S | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | A | - | G | V | - | - | - | M | - | S | L | R | A | 10 ± 1 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.PSMD4.1 | - | - | L | - | - | W | R | S | V | - | H | S | - | L | S | - | Y | - | A | - | K | P | T | S | L | R | A | 20 ± 5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.Ataxin3.1 | - | M | - | - | P | R | - | - | L | R | - | - | Q | A | A | - | - | - | - | F | T | R | K | S | L | R | A | 100 ± 10 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.Epsin1.2 | - | - | S | - | - | M | R | R | L | - | K | E | - | - | S | - | Y | - | - | V | P | R | K | S | L | R | A | 10 ± 5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.Epsin3.2 | A | R | N | V | S | V | R | - | L | - | E | N | G | - | - | - | Y | - | - | - | S | I | - | S | L | R | A | 25 ± 5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.Epsin1.1 | - | - | S | V | M | L | R | - | M | A | E | R | G | A | - | - | R | G | - | - | M | - | G | S | L | R | A | 30 ± 5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.Epsin2.1 | - | R | - | F | - | W | - | - | - | - | R | - | D | - | - | - | Y | - | - | S | - | F | L | S | L | R | A | 40 ± 10 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.Epsin3.1 | - | - | S | - | - | L | - | I | - | M | A | - | G | A | S | V | Y | - | - | S | - | I | K | S | L | R | A | 90 ± 10 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ZFAND2B.1 | - | - | I | - | A | Y | Q | - | V | S | H | T | L | - | - | I | - | D | A | - | - | P | - | S | L | R | A | 150 ± 20 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ANKRD13A.4 | - | - | - | H | - | W | N | - | - | S | L | - | Y | - | K | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | S | S | L | R | A | 180 ± 10 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ANKRD13B.3 | - | - | - | H | - | M | W | P | L | - | K | S | - | - | - | - | - | V | - | I | K | R | - | S | L | R | A | 110 ± 10 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ANKRD13D.4 | - | R | - | H | A | M | R | - | D | V | R | Q | - | - | I | - | - | - | L | - | W | P | - | S | L | R | A | 630 ± 130 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.RNF166 | - | - | - | I | - | V | R | - | D | P | H | R | G | C | - | - | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | S | L | R | A | 30 ± 5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.PARP10.2 | L | - | Q | - | - | - | - | I | - | - | S | Q | - | - | - | V | - | - | - | - | V | - | - | S | L | R | A | 170 ± 40 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.USP37.2 | - | - | I | R | A | V | - | Y | - | N | K | - | K | - | I | - | - | V | - | - | - | H | - | S | L | R | A | 740 ± 70 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.Epsin1.3 | - | - | - | V | - | - | - | P | - | I | K | - | D | - | - | V | Y | N | A | - | - | F | - | S | L | R | A | 30 ± 5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.Epsin2.2 | - | R | - | F | - | W | - | - | - | - | R | - | D | - | - | - | Y | - | - | S | - | F | L | S | L | R | A | 30 ± 10 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.EPS15 | - | - | Q | F | N | - | T | - | - | R | L | - | K | Y | N | - | Y | - | - | H | S | H | - | S | L | R | A | 80 ± 10 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.IGBP1 | A | - | V | - | S | V | F | - | - | P | R | - | - | T | S | I | L | - | A | - | - | - | M | S | L | R | A | 2.0 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.Ataxin3.2 | - | T | A | V | W | V | - | R | T | V | - | N | G | - | S | - | - | V | A | - | - | - | - | S | L | R | A | 20 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.USP37.3 | - | - | D | - | R | - | T | R | - | - | - | R | A | Y | - | - | Y | F | - | H | S | R | G | S | L | R | A | 190 ± 40 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.STAM | - | - | S | - | - | - | Y | - | M | R | H | R | - | - | I | - | Y | - | - | I | - | F | T | S | L | R | A | 130 ± 30 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.STAM2 | - | - | - | I | - | - | - | S | - | - | - | R | G | - | N | V | Y | F | - | A | - | - | - | S | L | R | A | 30 ± 10 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.USP25.1 | - | T | I | I | W | - | - | - | - | - | - | Y | G | - | R | - | - | G | A | - | - | - | - | S | L | R | A | 130 ± 30 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.USP28 | - | - | L | - | - | I | H | A | F | - | - | G | - | Y | P | I | Y | - | A | - | - | - | - | S | L | R | A | 15 ± 5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ANKRD13A.1 | M | - | - | - | A | A | M | - | - | - | H | - | G | - | - | - | - | V | - | V | - | V | - | S | L | R | A | 420 ± 40 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ANKRD13B.1 | - | - | I | - | - | A | - | N | - | - | H | Q | G | - | S | - | - | N | - | - | - | Q | K | S | L | R | A | 90 ± 10 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ANKRD13D.1 | - | - | I | - | - | R | - | - | - | - | - | - | K | L | - | - | - | - | - | P | - | F | - | S | L | R | A | 140 ± 20 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.UBXN7 | - | - | M | I | - | S | E | Y | L | S | K | T | K | - | I | - | - | F | G | R | W | - | S | S | L | R | A | 75 ± 10 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ANKRD13A.2 | L | S | L | I | I | - | R | - | - | M | - | E | G | G | R | - | V | - | G | - | - | - | G | S | L | R | A | 20 ± 2 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.ANKRD13D.2 | - | A | - | F | A | V | S | L | V | - | - | - | D | - | R | - | T | I | - | I | K | - | - | S | L | R | A | 250 ± 30 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.HUWE1 | - | W | F | - | - | - | N | K | Y | P | - | - | K | - | - | I | L | I | L | H | - | - | - | S | L | R | A | 10 ± 5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.Ataxin3.3 | - | V | - | - | - | P | S | S | E | S | - | R | - | - | V | V | V | V | - | P | - | - | - | S | L | R | A | 20 ± 1 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.RAP80.2 | - | - | I | H | S | R | Q | H | F | - | D | - | G | A | A | - | - | - | - | - | W | R | - | S | L | R | A | 40 ± 10 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.OTUD1 | I | T | - | - | - | V | - | S | S | V | - | - | Q | - | R | V | F | - | L | G | - | - | Q | S | L | R | A | 10 ± 1 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.MAP3K1 | - | - | N | - | - | L | - | - | - | - | M | R | A | - | N | V | W | - | - | - | - | R | - | S | L | R | A | 20 ± 5 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UbV.PSMD4.2 | - | - | A | I | - | - | - | Y | - | - | K | - | A | - | S | - | Y | I | - | F | S | H | - | S | L | R | A | 360 ± 60 |

The sequence of the most selective UbV is shown for each of 42 UlMs that were successful in phage display selections. The affinity of each phage-displayed UbV for its cognate UlM was estimated as an IC50 value by competitive phage ELISA (Figure S2). Positions that were diversified in the library are shown, and dashes indicate conservation as the Ub.wt sequence. The last four positions were not diversified, but rather, they were fixed as sequences that differ from Ub.wt to ensure that they could not be recognized by E1 charging enzymes, and thus, could not be involved in ubiquitination reactions in cells. Numbering is based on Ub.wt and letters denote the extended C-terminus of UbVs.

Figure 3. Specificity of UIM-binding UbVs.

The specificities of selected UbVs were determined by phage ELISA. Binding of phage-displayed UbVs (x-axis, sequences in Table 2) was assessed for peptides representing all 60 UIMs (y-axis, sequences in Table 1), which were clustered based on their sequence similarity. Binding was also assayed for the negative controls GST and BSA, and for a positive control anti-Flag antibody that recognized a Flag tag fused to the N-terminus of the phage-displayed UbV. The absorbance at 450 nm was normalized to the absorbance measured for the anti-Flag Ab control, and the normalized mean of three independent experiments is shown. Black boxes indicate interactions between UbVs and their cognate UIM target. Grey shading indicates UIMs which failed to generate binding UbVs. The specificity profiles of all 138 isolated UbVs are shown in Figure S1 and measured absorbance values of each interaction are reported in Supplementary File 2.

While some UbVs exhibited cross-reactivity for many UIMs, this analysis revealed that many were remarkably specific, with 26% recognizing their cognate UIM only and 52% recognizing three or fewer UIMs.

Moreover, competitive phage ELISAs revealed that the majority of the UbVs bound to their cognate UIMs with high apparent affinities, with 57% exhibiting IC50 values below 100 nM (Table 2 and Figure S2), while Ub.wt recognizes UIMs with affinities in the 100–500 μM range11. Although these measurements are only semi-quantitative in nature, they represent a good estimation of the enhanced affinity of the engineered UbVs.

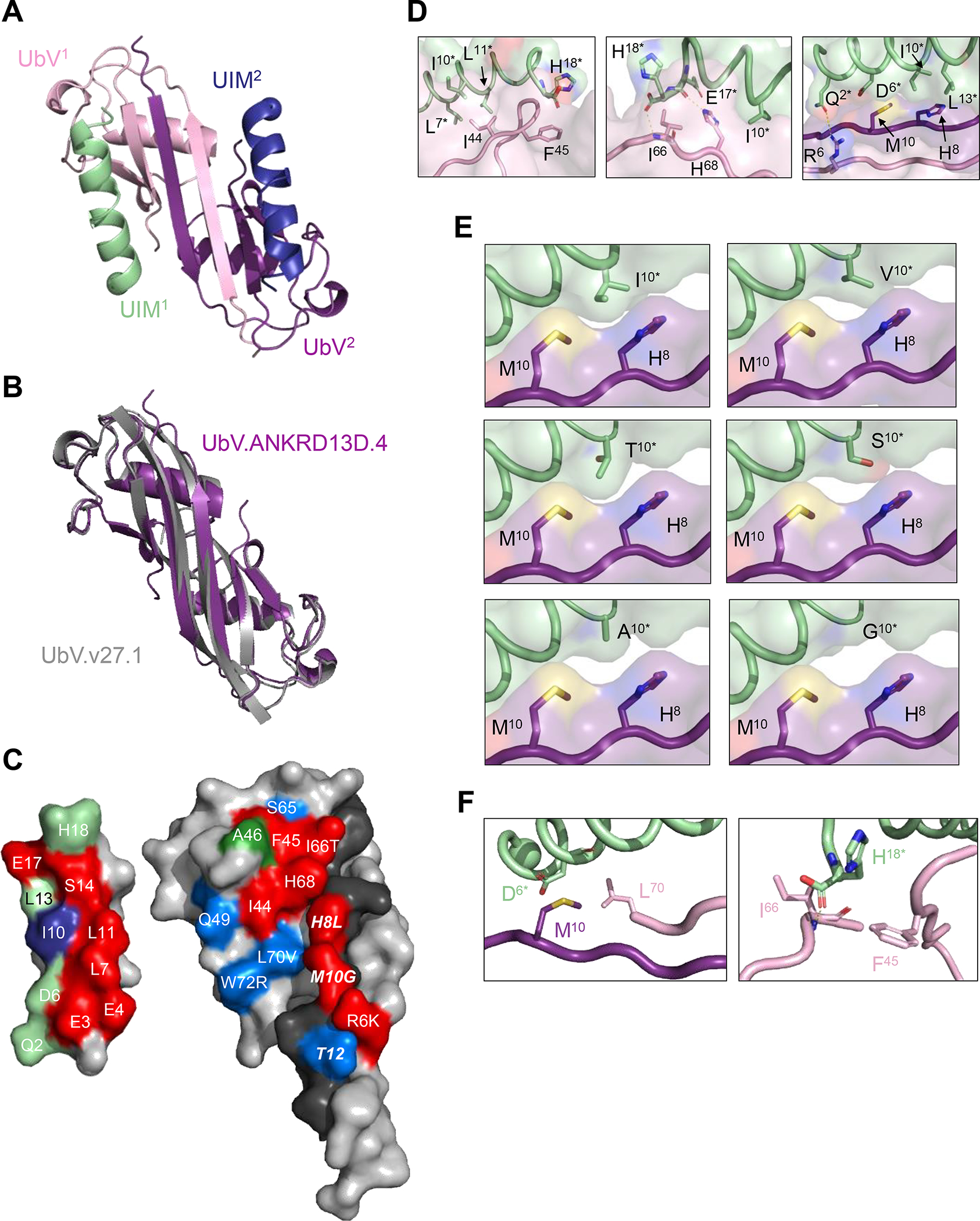

Structural analysis of a UbV:UIM complex

To better understand the basis for enhanced affinity and specificity, we attempted to crystallize several UbV:UIM complexes and were successful in determining the X-ray structure of UbV.ANKRD13D.4 in complex with a synthetic peptide representing the fourth UIM (UIM.ANKRD13D.4) of the Ankyrin Repeat Domain 13D protein (ANKRD13D) at 2 Å resolution (Table 3).

Table 3.

Data collection and refinement statistics for the X-ray structure of the complex between UbV.ANKRD13D.4 and UIM.ANKRD13D.4

| Data collection | |

|

| |

| Beamline | NECAT 24-ID-C |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9792 |

| Crystal | Native |

| Space group | P41212 |

| Cell dimensions [a=b,c (Å)] | 45.8, 84.4 |

| Resolution (Å) | 32.4–1.98 (2.03–1.98)* |

| Total no. unique observations | 6724 (448) |

| Mean [(I)/σ(I)] | 14.0 (3.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100) |

| Rmerge | 0.067 (0.511) |

| Multiplicity | 7.0 (6.8) |

| Wilson B -factor | 32.9 |

|

| |

| Refinement statistics | |

|

| |

| Resolution (Å) | 32.4–2.0 |

| No. of reflections | 6482(648)** |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.208/0.246 |

| RMSD Bond length (Å) | 0.006 |

| RMSD Bond angles (°) | 0.725 |

| No. of protein atoms | 764 |

| No. of Ion atoms | 6 (1 SO4-2, 1 Na+) |

| No. of water atoms | 17 |

| Average B -factor protein | 47.4 |

| Average B -factor ion atoms | 51.9 |

| Average B -factor water atoms | 48.8 |

| Ramachandran statistics (Molprobity) | |

| Preferred (%) | 97.8 |

| Allowed (%) | 2.2 |

| Disallowed | 0 |

| Clashscore | 5.9 |

Values in parentheses represent the highest resolution shell

number of reflections in the R-free set

The crystal, with tetragonal symmetry in space group P4122, contained only one UbV and one UIM in the asymmetric unit. However, using PISA 45,46, we determined that the most likely arrangement of this complex was as a 2:2 dimer, in which the second UbV and UIM are generated via 2-fold rotation around the x-y plane. The structure revealed that two UbVs form a symmetric β-strand-swapped dimer, in which the β1 strand of one UbV protomer is extended and forms an antiparallel β-sheet with the opposite UbV protomer (Figure 4A). Both UbV protomers interact with two UIM α-helices through a 2:2 binding stoichiometry, with the UIMs arranged in an anti-parallel orientation. The dimeric structure and overall fold are very similar to that of the previously described structure of UbV.v27.1 in complex with the UIM of yeast Vps27, as the mainchains of the UbVs in the two structures superposed with an RMSD of 1.52 Å (Figure 4B). However, while the two yeast UIM α-helices established contacts that enhanced affinity44, the two UIM.ANKRD13D.4 protomers are not in direct contact. The structural similarity between UbV.v27.1 and UbV.ANKRD13D.4 was further confirmed by size exclusion chromatography. In fact, as observed for UbV.v27.144, UbV.ANKRD13D.4 eluted as apparent oligomers and M10G substitution as in Ub.wt resulted in a UbV.ANKRD13D.4 variant that eluted at the same volume as Ub.wt, indicating the essential role of Met10 for maintaining the oligomeric state in UbV.ANKRD13D.4 (Figure S3).

Figure 4. Crystal structure of UbV.ANDRD13D.4 bound to UIM.ANDRD13D.4.

(A) Overall architecture of the dimeric UbV-UIM complex. The UbV protomers are colored pink (UbV1) or purple (UbV2) and the UIMs are colored green (UIM1) or blue (UIM2) with N-termini shown as spheres. (B) Superposition of UbV.ANKRD13D.4 (purple) and UbV.v27.1 (PDB ID: 6NJG, grey) homodimers. (C) Open book view of the contact surfaces between UIM1 (left) and UbV.ANKRD13D.4 (right). Only half of the UbV dimer is shown, consisting of UbV1 residues 1–74 and the β1-strand of UbV2 (residues 1–14). UbV1 and UbV2 are in light or dark color, respectively. Non-contact residues are colored grey. UbV residues that contact UIM1 are colored red if alanine substitutions abolished binding, blue if alanine substitutions had a <3-fold effect on binding, or green if they were not subjected to alanine-scanning (Supplementary Figure S3). UbV contact residues are labeled, and for those that differ from Ub.wt, the wt sequence is shown to the right of the residue label. Contact residues in UbV2 are labeled in bold italics. UIM1 residues that contact the UbV are colored red or blue if they occupy positions that define the UIM consensus and match or do not match the consensus sequence (Table 1), respectively, or green if they do not occupy positions that define the UIM consensus. UIM1 residues are numbered as in Table 1. (D) Close up views of molecular interactions between UbV.ANKRD13D.4 and UIM.ANKRD13D.4. The UbV and the UIM are coloured as in (A), with asterisks indicating UIM residues. Yellow dotted lines show polar contacts. (E) Close up views of the contacts between Ile10* or substitutions in UIM1 (green), and His8 and Met10 of UbV2 (purple). Ile10* was computationally mutated to residues found at position 10 in other UIMs (see Table 1 for full sequences). (F) Close up view of the interactions between Asp6* of UIM.ANKRD13D.4 and Met10 in UbV2 and Leu70 present in UbV1 (left panel) and of the contacts established between Phe45 and Ile66 of UbV.ANKRD13D.4 and His18* of UIM.ANKRD13D.4 (right panel). Dotted yellow line shows a polar interaction between the Ile66 backbone amine group and the carboxyl group of His18*.

The binding interfaces of UbV.ANKRD13D.4 involving the two UIMs were identical, and here we describe the interface involving UIM1. The binding interactions result in the burial of ~578 Å2 and ~460 Å2 of surface area on the UbV and the UIM, respectively (Figure 4C). On the UbV side, 77% of the interface (451 Å2) is formed by 10 residues from one UbV protomer (UbV1) and the remaining 23% (127 Å2) is formed by three residues (His8, Met10 and Thr12) from the second UbV protomer (UbV2). The UbV contains 13 substitutions relative to Ub.wt, but only six of these (Arg6, His8, Met10, Ile66, Leu70 and Trp72) are involved in the interface, where they contribute 38% of the buried surface area. On the UIM, one face of the α-helix is buried, and 11 residues make contacts that contribute to the buried surface area. These include seven residues at positions that define the UIM consensus (Table 1) (Glu3*, Glu4*, Leu7*, Ile10*, Leu11*, Leu13*, Ser14*, Glu17*; UIM residues are denoted by asterisks) and only Ile10* does not match the consensus sequence, which is Ala10*. The other three contact residues (Gln2*, Asp6*, His18*) occupy positions that are not conserved in the UIM consensus.

We used alanine-scanning mutagenesis to determine the functional contributions of contact residues within the UIM-binding site of UbV.ANKRD13D.4. In this method, individual amino acids are replaced with alanine residues, which results in the truncation of side chain atoms beyond the β-carbon, and the effects on affinity are good estimates of the energetic contributions of each side chain to binding 47,48. We constructed a panel of 12 alanine substitutions targeting major contact positions in the context of the phage-displayed UbV to enable facile binding measurements by phage ELISA. Direct-binding ELISAs showed that binding of UbV-phage to the GST-UIM.ANKRD13D.4 fusion was completely abolished by alanine substitutions at four UbV positions that differed from Ub.wt (Arg6, His8, Met10, Ile66) and three positions that were the same as Ub.wt (Ile44, Phe45, His68) (Figure S4A). The other five alanine substitutions had <3-fold effects on binding affinities estimated by competitive phage ELISAs (Figure S4B), and these included two positions that differed from Ub.wt (Leu70, Trp72) and 3 positions that matched Ub.wt (Thr12, Gln49, Ser65).

The alanine-scanning results were mapped onto the structure of UbV.ANKRD13D.4 to obtain a detailed view of the functional epitope for binding to UIM.ANKRD13D.4 (Figure 4C). This analysis revealed an extended functional epitope formed by two patches. One patch consisted of four residues (Ile44, Phe45, Ile66, His68) that overlapped with the Ile44-centered hydrophobic patch that is important for Ub.wt binding to many of its partners49, and a second patch consisted of three residues (Arg6, His8 and Met10) within the β1-strands that mediate formation of the UbV dimer. The functional epitope interacted with residues extended across the length of the UIM α-helix, and these interactions resulted in the burial of 311 and 251 Å2 of surface area on the UbV functional epitope and the UIM, respectively. Roughly half (55%) of the buried surface on the UIM was contributed by residues that matched the UIM consensus, showing that energetically important interactions are evenly divided between UIM residues that are conserved or divergent across the family.

We next analyzed the details of the molecular interactions between the seven residues that formed the UbV functional epitope and residues within the UIM binding surface (Figure 4D). The hydrophobic UbV residue Ile44 interacts with the hydrophobic sidechains of Leu7*, Ile10* and Leu11*, and the aromatic ring of the Phe45 sidechain makes favourable packing interactions with the mainchain and sidechain of His18* (Figure 4D, left panel). These residues are conserved in Ub.wt, and thus presumably, these interactions would also occur in the interaction between Ub.wt and the UIM. The UbV residue His68 is also conserved in Ub.wt, and thus, the interactions between its sidechain and the sidechains of Ile10* and Glu17*, as well as the hydrogen bond between the His68 sidechain and the Glu17* mainchain, could also occur in an interaction between Ub.wt and the UIM (Figure 4D, center panel). While the hydrogen bond between the mainchain α-amino group of UbV residue Ile66 and the mainchain carboxyl group of His18* could be established by Thr66 of Ub.wt, the interactions formed by the Ile66 sidechain cannot be replicated by Ub.wt (Figure 4D, center panel). The sidechain of UbV residue Arg6 makes a hydrogen bond with Gln2* of the UIM, which the shorter Lys6 sidechain of Ub.wt is unlikely to mimic, and the sidechain of UbV residue His8 makes close contacts with the sidechains of UIM residues Ile10* and Leu13*, which the smaller Leu8 sidechain of Ub.wt is unlikely to mimic (Figure 4D, right panel). Furthermore, the sidechain of UbV residue Met10 makes hydrophobic contacts with the Ile10* sidechain and the aliphatic portion of the Asp6* sidechain, and these interactions cannot be made by Ub.wt, which contains a Gly10 residue that lacks a sidechain (Figure 4D, right panel). Taken together the structural and functional analyses showed that the UbV uses several residues that are conserved with Ub.wt (Ile44, Phe45, His68) and several residues that are not conserved (Arg6, His8, Met10, Ile66) to mediate energetically favourable interactions with the UIM, and the interactions involving unconserved residues likely explain the enhanced affinity of the UbV compared with Ub.wt.

We further investigated the nature of the UbV.ANKRD13D.4:UIM interaction by subjecting to alanine-scanning mutagenesis every UIM residue making contacts with the UbV. ELISA binding experiments showed that binding to UbV.ANKRD13D.4 is completely abolished by 7 out of 10 alanine substitutions in GST-UIM.ANKRD13D.4 variants (Figure S5A), and binding was significantly reduced for other alanine-substituted UIM variants that could still interact with the UbV (Figure S5B).

The structural and functional analysis also shed light on the basis for the exquisite specificity of UbV.ANKRD13D.4, which only recognizes its cognate UIM.ANKRD13D.4 amongst 60 UIMs (Figure 3). Most notably, UIM.ANKRD13D.4 is one of only two UIMs (along with UIM.ANKRD13B.3) that contain an Ile10* residue. In 52 of the other 58 UIMs, position 10* is occupied by an Ala residue, which matches the UIM consensus, and in the six remaining UIMs position 10* is occupied by a Val, Thr, Ser or Gly residue. Ile10* of UIM.ANKRD13D.4 makes favourable packing interactions with His8 and Met10 of UbV.ANKRD13D.4, and molecular modeling suggests that these interactions would be reduced with a Val10* or Thr10* residue and would be absent with a Ser10*, Ala10* or Gly10* residue (Figure 4E). To confirm this hypothesis, we constructed a panel of GST-UIM.ANKRD13D.4 variants in each of which Ile10* was substituted by a residue occurring at the same position in other UIMs and determined binding by competitive phage-ELISA. In agreement with our in silico analysis, mutation of Ile10* completely abolished binding of UbV.ANKRD13D.4 to 4 out of 5 UIM variants (Figure S6A). Only the UIM containing an I10V substitution retained binding to UbV.ANKRD13D.4, but its apparent affinity was significantly lower than that of wild-type (Figure S6B).

Thus, the critical difference at UIM position 10* can explain the specificity of UbV.ANKRD13D.4 for UIM.ANKRD13D.4 compared with all but one of the other UIMs that we analyzed. For UIM.ANKRD13B.3, differences at other positions relative to UIM.ANKRD13D.4 are likely responsible for its lack of binding to UbV.ANKRD13D.4. In particular, the sequence of UIM.ANKRD13B.3 differs at only two positions that are involved in contacts between UIM.ANKRD13D.4 and UbV.ANKRD13D.4, and molecular modeling shows that these differences are subtle at the structural level (Figure 4F). The sidechain and mainchain of Asp6* in UIM.ANKRD13D.4 pack closely with the sidechains of Met10 in UbV2 and Leu70 in UbV1 respectively, and it is possible that the longer Glu6* sidechain of UIM.ANKRD13B.3 may introduce a steric clash in this region. At the other end of the UIM.ANKRD13D.4 α-helix, the sidechain of His18* makes hydrophobic interactions with the aromatic ring of Phe45, whereas the sidechain and mainchain of Ile66 interact with the mainchain carboxyl and the C-α carbon of His18* respectively (Figure 4F, right panel). Although the Gln18* of UIM.ANKRD13B.3 is similar to His18* of UIM.ANKRD13D.4, it is possible that the longer sidechain of Gln18* might clash with the aromatic ring of Phe45. Taken together, these results show that, in most cases, the exquisite specificity of UbV.ANKRD13D.4 for its cognate UIM.ANKRD13D.4 can be explained by interactions involving the residue at position 10*, which is an Ile in UIM.ANKRD13D.4 but differs in all but one of the other UIMs in our panel.

Effects of a UIM-binding UbV on the function of USP28

The roles of UIMs in regulating the substrate recognition of DUBs has been described in several studies 25,50,51. We recently used UbVs to probe the contributions of the UIMs of zebrafish USP37 to catalytic function and showed that the third UIM in particular was required for optimal positioning and hydrolysis of K48-linked di-Ub 52. Similarly, we assessed the effects of UbV.USP28, which binds with high specificity and affinity (IC50 = 15 ± 5 nM) to the single UIM of the cancer-associated DUB USP28 (Figure 3 and Table 2) 53–55.

DUBs typically mediate cleavage of Ub chains by interacting with both the proximal Ub (primary amine donating) and distal Ub (carboxy terminus donating). We first used a model substrate, Ub-AMC, in which the proximal Ub moiety is replaced by a cleavable fluorescent molecule (AMC, 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin). We reasoned that if the UIM interacted with the proximal Ub, then blockade of the UIM by UbV.USP28 would have no effect on the cleavage of Ub-AMC, which lacks a proximal Ub. Indeed, as was the case with USP37 52, UbV.USP28 did not affect hydrolysis of Ub-AMC even at concentrations in the micromolar range (Figure 5A). In contrast, UbV.USP28 acted in a dose-dependent manner to protect K11-linked di-Ub chains from hydrolysis by USP28 (Figure 5B). Again, this resembled the case of USP37 where a UIM-binding UbV inhibited cleavage of K48-linked di-Ub. These results showed that the UIM of USP28 most likely enhances the cleavage of Ub chains by binding to the proximal Ub of K11-linked di-Ub and positioning the substrate correctly in the active site.

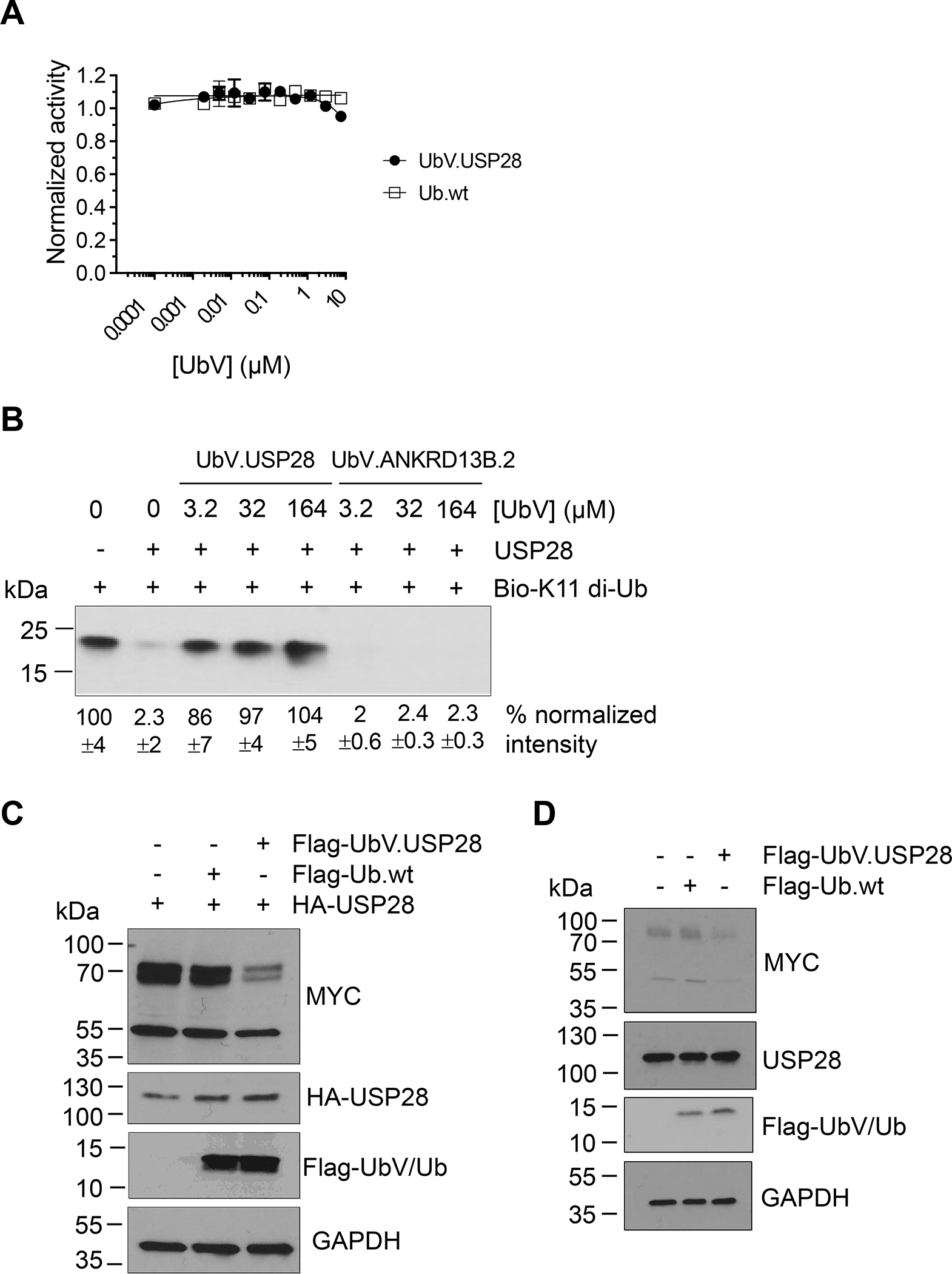

Figure 5. Effects of UbV.USP28 on USP28 function.

(A) Dose response curves for the effect of UbV.USP28 (filled circles) or Ub.wt (open squares) on the hydrolysis of Ub-AMC by USP28. Proteolytic activity was normalized to the activity in the absence of UbV.USP28 or Ub.wt and curves represent the mean of measurements from three independent experiments ± 1 SD. (B) Representative western blot showing effects of USP28 on levels of K11-linked di-Ub in the presence of UbV.USP28 or the irrelevant UbV.ANKRD13B.2. Biotinylated K11-linked di-Ub chains were incubated for 90 minutes with 100 nM USP28 in the absence or presence of indicated concentrations of UbVs, and following SDS-PAGE, were detected with neutravidin-HRP. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry and were normalized to the intensity in the absence of USP28 (mean ±1 SD; n = 3). (C) Representative western blot showing effects of UbV.USP28 on levels of endogenous MYC protein in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids encoding HA-tagged USP28 and Flag-tagged UbV.USP28 or negative control Ub.wt. Following SDS-PAGE, MYC protein, USP28, and UbV/Ub were detected with an anti-MYC, anti-HA or anti-Flag antibody, respectively. (D) Whole cell extracts from HeLa cells transfected with either UbV.USP28 or Ub.wt were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. UbV.USP28 inhibits the catalytic activity of endogenous USP28 resulting in reduced MYC levels.

Next, we explored whether UbV.USP28 could inhibit the function of USP28 in live cells. Previously, it has been shown that the MYC protein is a cellular substrate for USP28, and deubiquitination and consequent stabilization of this transcription factor may at least partly explain the pro-oncogenic effects of USP28 56. Thus, we employed a previously established cellular model system to evaluate the effect of UbV.USP28 on MYC protein levels 54. We transfected HeLa cells with a plasmid encoding HA-tagged USP28 and a plasmid encoding either Flag-tagged UbV.USP28 or Ub.wt as a negative control. Consistent with previous results with shRNA-mediated down-regulation of USP28 protein levels 56, expression of UbV.USP28 greatly reduced levels of endogenous MYC, whereas expression of Ub.wt had no effect (Figure 5C). Surprisingly we observed minimal MYC levels reduction when HeLa cells were transfected with UbV.USP28 or an unrelated UbV (Figure S7). However, MYC levels greatly decreased when UbV.USP28 was co-transfected with HA-USP28, suggesting the specific interaction of the UbV (Figure S7). We further confirmed these results by directly transfecting HeLa cells with Flag-tagged UbV.USP28 or Ub.wt without overexpression of USP28. As previously observed, UbV.USP28, but not Ub.wt, reduced endogenous MYC levels, albeit to a lower extent (Figure 5D).

Taken together, these results showed that UbV.USP28 binds to the UIM of USP28 and inhibits hydrolysis of Ub chains both in vitro and in cells, and these findings suggest that targeting of UIMs may be an alternative means of inhibiting DUBs including USP28, USP37 and potentially others.

Discussion

UIMs are short α-helical modular recognition domains that, in addition to acting as Ub receptors, mediate the ubiquitination of proteins that contain them, regulating their activity 15,57,58. Unsurprisingly, UIM dysregulation has been associated with cancer and other diseases 59–61, highlighting their contribution in regulating proteostasis and cell signalling in vivo. However, understanding the biological role of UIMs has been limited due to their small surface and lack of molecular probes targeting them.

We developed a novel phage-displayed UbV library and selected UbVs to target short α-helical UIM motifs in the human proteome. By combining bioinformatics and literature searching, we identified 60 UIMs, and for 42 of these, we isolated UbVs that often exhibited high affinity and exquisite specificity. Indeed, many UbVs showed absolute binding specificity for their cognate UIMs amongst the entire panel of 60 UIMs, showing that UbVs can be engineered as highly selective probes to explore the biological functions of UIMs in the proteome. For example, some UbVs were able to distinguish between UIMs that differed in two amino acids, as in the case of UbVs targeting PIPSL and PSMD4.1. On the other hand, some UbVs were more promiscuous and bound to multiple UIMs. These promiscuous UbVs even bound to UIMs that did not yield UbVs in binding selections, and thus, they could be used as scaffolds to design new phage-displayed UbV libraries to obtain binders for additional α-helical motifs that are more divergent from the canonical UIM motif.

Structural and alanine-scanning analyses of UbV.ANKRD13D.4 in complex with its cognate UIM.ANKRD13D.4 revealed that only six of the 13 substitutions relative to Ub.wt were involved in the binding interface, and only four of these appear to be functionally important. Thus, it appears that a relatively limited number of sequence changes can endow UbVs with tight and specific recognition of particular UIMs. As observed previously for several other UbVs 27,31,32,44, UbV.ANKRD13D.4 formed a β1-strand-swapped dimer, and gel-filtration size-exclusion chromatography analysis of several UbVs isolated from the UtU library, which contained hydrophobic residues at position 10 (e.g. Trp, Leu, Ile), showed evidence of dimers and oligomers (Figure S8). These findings highlight the plasticity of the dimeric interface of UbVs and underscore the importance of the UbV dimer for achieving tight and specific recognition of its cognate UIM.

We previously used UbVs targeting UIMs of USP37 to dissect its catalytic mechanism52, demonstrating the usefulness of the UbV technology for investigating the functions of enzymes in the UPS. Here, we used a UbV that recognized the UIM of USP28 to show that binding to the UIM can inhibit catalytic activity for K11-linked di-Ub but not for Ub-AMC, demonstrating that USP28 inhibitors can target domains distinct from the catalytic site.

Thus, UbVs may be exploited to aid development of allosteric inhibitors of DUBs, including those with active sites that are catalytically active only upon binding to Ub - such as USP762,63 - and this in turn has the potential to significantly expand the possibilities for developing therapeutic inhibitors of DUBs.

In conclusion, our UbV panel provides a powerful toolkit for probing the function of UIMs in proteins in vitro and in cells, and our work provides a framework for the development of UbVs targeting other Ub-binding domains. Moreover, UbVs could facilitate the discovery of small-molecule inhibitors targeting modular recognition elements in the human proteome, and thus, could aid the identification of novel therapeutic targets and expand the druggable protein space.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge online at http://pubs.acs.org.

Supplemental Tables and Figures include sequences of selected UbVs, sequences of mutagenic oligonucleotides used to clone the UtU library, specificity profile heatmap of UIM:UbV interactions, UbVs binding curves, SEC profiles of UbVs characterized in the study and further data for in vivo inhibitory activity of UbV.USP28. Supplementary Files contain sequences of isolated UbVs and UIMs used in the study and raw data for UbVs binding specificity analysis.

Methods

Bioinformatic analysis to construct a panel of human UIMs

We searched the Pfam database 40 for non-redundant sequences matching the UIM consensus sequence across 950 species, and we identified 5,828 UIM-containing proteins. Hidden Markov model profile was generated using Skylign 64, and the list of UIMs was further curated by searching human proteins in the UniProt and Smart databases 42,43 with the consensus x-Ac-Ac-Ac-x-x-φ-x-x-Ala-φ-x-x-Ser-z-x-Ac (where Ac is an acidic residue, φ is a hydrophobic residue, A is alanine, S is serine, z is a bulky hydrophobic or polar residue with aliphatic content, and x is any residue). We validated the identified UIMs by literature searching and confirmed the identification of 57 UIMs. However, to assemble a list of UIMs as comprehensive as possible, following sequence analysis we decided to include in our panel three additional sequences (from USP37, EPS15 and PARP10) that were found only in the Smart database, but closely matched the UIM consensus sequence and were embedded in proteins known to contain other UIMs. Therefore, our dataset contained 60 UIM sequences from 31 human proteins (Table 1).

Phage-displayed library construction

The phage-displayed UbV library UtU was constructed by combinatorial site-directed mutagenesis of a phagemid designed for the display of UbV.v27.1 on phage. Two regions (region 1, positions 5–14; region 2, positions 62–74) were simultaneously mutated with a soft randomization strategy 65, in which the nucleotide ratios of diversified positions in the mutagenic oligonucleotides were adjusted to 70% of the wt nucleotide and 10% of each of the other three nucleotides (Table S2). Mutagenic oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. The constructed library UtU contained 1.7 × 1010 unique members.

Phage display binding selections

For selection of UIM-binding UbVs, GST-fused UIMs (0.2 μM in PBS) were immobilized on 96-well Nunc-Immuno MAXISORP plates (Thermo Scientific), and phage representing library UtU were cycled through five rounds of binding selections with the immobilized GST-UIM fusion protein, as described 66. To remove UbVs binding to non-target proteins, the phage library was pre-incubated for 1 hour at 25 °C on plates coated with 1 μM GST prior to transfer to plates coated with GST-UIM. Phage ELISAs were performed to identify positive clones able to bind to the GST-UIM fusions but not GST, and the amino acid sequences of UIM-binding UbVs were determined by DNA sequencing.

Expression and purification of GST-UIM fusion proteins

Plasmids encoding UIMs fused to the C-terminus of GST were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3), and single colonies were used to inoculate 10 ml 2YT medium containing 0.1 mg/ml carbenicillin. Cultures were grown overnight at 37 °C with 200 rpm shaking, diluted 1:100 in 2YT medium containing 0.1 mg/ml carbenicillin, grown at 37 °C with 200 rpm shaking to OD600 0.6–0.8, and induced with 0.1 mM IPTG at 18 °C with 200 rpm shaking for 18 hours. Cultures were pelleted and resuspended in 15 ml lysis Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich)). Cells were lysed by sonication, and protein purification was performed by standard methods with Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen), eluting proteins with an imidazole buffer gradient ranging from 30–300 mM. The purity of eluted fractions was determined by SDS-PAGE, and the buffer of eluted proteins was exchanged by dialysis at 4 °C into PBS pH 7.4. Protein concentrations were determined from OD280 measurements and calculated using extinction coefficients from ExPASy ProtParam 67.

Protein crystallization and structure determination

To purify UbV.ANKRD13D.4, E. coli BL21(DE3) cells previously co-transformed with UbV-encoding plasmid and a plasmid encoding the Erv1p and DsbC chaperones were grown in 2YT medium containing 0.1 mg/ml carbenicillin and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol at 37 °C with 200 rpm shaking to OD600 = 0.4. Erv1p and DsbC expression was induced with 0.5% (w/vol) arabinose, the temperature was lowered to 30 °C, and cultures were incubated with 200 rpm shaking for 45 min, as described 68. Protein expression was induced by adding 0.1 mM IPTG at 30 °C and cultures were incubated with 200 rpm shaking for 4 hours. His-tagged UbV protein was purified by standard methods on Ni-NTA (Qiagen), dialyzed three times into TEV cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 0.5 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), 0.5 mM EDTA) and digested for 18 hours at 4 °C with TEV protease at a 1:100 molar ratio of protease:substrate to remove the His-tag. After 18 hours, an excess of TEV was added and cleavage of His-tag was allowed to proceed for 3 hours. UbV protein was purified again with Ni-NTA resin, unretained fractions were collected, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-4 concentrators with a 3 kDa cutoff (EMD Millipore).

The UbV protein was buffer-exchanged into TBS buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-4 concentrators with a 3 kDa cutoff (EMD Millipore). The UbV protein was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using an ÄKTA system (GE Healthcare) equipped with a Hi-Load 16/60 Superdex 75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Protein purity was verified by SDS-PAGE, and UbV protein was concentrated to 12 mg/ml as described above. Protein concentration was determined by BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Crystals were grown in hanging drops by mixing 500 μM UbV protein with 500 μM UIM.ANKRD13D.4 peptide (RGQQEEEDLQRILQLSLTEH, GeneScript) in the reservoir solution (100 mM sodium acetate pH 4.5, 100 mM LiSO4, 50% (w/vol) PEG 400). Hanging drops were incubated at 20 °C for 6–10 days. Crystals were cryoprotected by soaking them in the reservoir solution containing a final ethylene glycol concentration of 20% (vol/vol). Data were collected at NE-CAT 24 ID-C (Advanced Photon Source, Chicago, IL) and processed with HKL2000 69.

The structure was solved by molecular replacement with Phaser 70 using the coordinates for UbV.15.2 (PDB 6CRN), a UbV targeting the DUSP domain of USP15 71. The β1-strand-swapped dimer of UbV.ANKRD13D.4 was rebuilt using Coot 72, whereas the UIM.ANKRD13D.4 α-helix was built from difference density using Coot, following several rounds of refinement with Phenix.refine in the PHENIX crystallography suite 73. Further refinement of the complex structure was accomplished with rebuilding in Coot, followed by automatic water-picking with Phenix.refine graphical interface. TLS parameters were generated from the coordinates and used during refinement 74, and the final model was validated using MolProbity 75, with no Ramachandran outliers and a good clashscore (see Table 3).

The UbV.ANKRD13D.4 figures were generated and rendered with PyMOL (version 2.1, Schrödinger, Cambridge, UK) and computational mutagenesis was performed using the mutation wizard tool in the PyMOL suite.

Analytical size-exclusion chromatography

Following cleavage of His-tag as previously described, UbVs were analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography on an ÄKTA Purifier 10 (GE Healthcare) using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (24 ml bed volume) (GE Healthcare). 500 μl/sample at 2 mg/ml were injected onto the column and eluted at 0.8 ml/min flow rate in TBS (50 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) The column was calibrated using molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad) ranging from 660 kDa to 1.35 kDa (thyroglobulin, IgG, ovalbumin, myoglobin, and vitamin B12).

Phage ELISAs

GST-UIM protein was immobilized on 384-well MaxiSorp plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by adding 25 μl/well of 0.5 μM GST-UIM in PBS and incubating overnight at 4 °C. Wells were blocked by addition of 60 μl/well of PBS containing 0.5% BSA (PB buffer) and incubation at 25 °C for 1 hour. Plates were washed four times with 90 μl/well of PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PT buffer) and incubated with 25 μl/well of phage stocks previously diluted three-fold in PB buffer containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBT buffer). Following phage incubation at 25 °C for 1 hour with gentle agitation, plates were washed as described above, and phage binding was detected using 25 μl/well of an anti–M13-HRP conjugated antibody (1:3,000 dilution in PT buffer; GE Healthcare). Following incubation at 25 °C for 30 minutes with gentle shaking, plates were washed as described above, and binding was assessed by adding 25 μl/well of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) chromogenic substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Plates were incubated with TMB substrate at 25 °C with gentle shaking for 5–10 minutes, and the colorimetric reaction was stopped by addition 1 M H3PO4 (25 μl/well). Plates were read spectrophotometrically at 450 nm using a PowerWave XS microplate reader (BioTek).

Competitive phage ELISAs were performed as described 34, except GST-UIM protein was immobilized on plates at a concentration of 0.2 μM, and non-saturating concentrations of phage-displayed UbVs were allowed to bind to the immobilized targets for 20 minutes at 25 °C in the presence of varying concentrations (8,000–2 nM) of soluble GST-UIM protein.

For IC50 measurement of UbV.ANKRD13D.4 variants, competitive phage ELISAs were carried out as above, but soluble UIM.ANKRD13D.4 peptide (RGQQEEEDLQRILQLSLTEH, GenScript) was used as the competitor, instead of the GST-UIM protein. Data were plotted using the Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc), by fitting the curves with the one-site binding Hill model. The half maximal inhibition concentration (IC50) value was determined as the concentration of soluble UIM competitor that reduced by 50% the binding of phage-displayed UbVs to immobilized GST-UIM protein.

Cell Culture

HeLa cells (ATCC) were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies) containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Plasmids for cell culture

Mammalian-codon-optimized gene fragments encoding UbV.USP28, UbV.ANKRD13B.2 or Ub.wt lacking the two C-terminal Gly residues (Integrated DNA Technologies) were cloned into pCDNA3.1 (ThermoFisher), in frame with a N-terminal triple Flag tag, by Gibson assembly. An expression plasmid for HA-tagged human USP28 was obtained from Stephen Elledge (plasmid 41948, Addgene) 76.

USP28 activity assays

To assay for inhibition of cleavage of Ub-AMC (Boston Biochem, U-550), 5 nM USP28 (Boston Biochem, E-570) was incubated for 30 minutes at 25 °C with serial dilutions of UbV.USP28 ranging from 19–7,500 nM in cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.01% Tween-20), prior to the addition of 1 μM Ub-AMC. Release of AMC was detected for 30 minutes using a BioTek Synergy2 plate reader (BioTek Instruments) by monitoring the increase of fluorescence emission at 460 nm (excitation at 360 nm).

For K11-linked di-Ub chains (Boston Biochem, UC-40B) cleavage inhibition assays, Ub chains were biotinylated using succinimidyl-6-(biotinamido)-6-hexanamido hexanoate biotin (EZ-Link™ Sulfo-NHS-LC-LC-Biotin, Thermo Fisher), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To assay for inhibition of cleavage, 6 μM biotinylated K11-linked di-Ub chains were incubated for 90 minutes at 37 °C in cleavage buffer with 100 nM USP28 (BostonBiochem, E-570), in the absence or presence of 3.2, 32 or 164 μM UbV. The reaction was stopped by adding 6x Laemmli buffer (0.23 M Tris HCl pH 6.8, 24% v/v glycerol, 120 μM bromophenol blue, 0.23 M SDS, 100 mM DTT) and heating to 95 °C for 5 minutes. Following separation by SDS-PAGE, samples were transferred onto Immobilion-P polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Merk Millipore) using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer system (BioRad). Membranes were blocked at 25 °C for 2 hours with gentle shaking in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5% (w/v) BSA (blocking buffer) and probed with 1 μg/ml Neutravidin-HRP conjugate (Pierce) in blocking buffer containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 hour at 25 °C with gentle shaking. Membranes were washed three times with TBST for 10 minutes at 25 °C with gentle shaking. Biotinylated K11-linked di-Ub chains were detected with the ECL western blotting substrate (ThermoFisher), and bands were analyzed by densitometry using ImageJ2 77. Percent inhibition was calculated as 100X (pixel density of UbV-treated samples/pixel intensity lanes containing only biotinylated K11-linked di-Ub chains).

To assay for inhibition of USP28 in cells, HeLa cells were co-transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with plasmids encoding HA-tagged USP28 (0.8 μg) and Flag-tagged UbV.USP28 (1.7 μg), Flag-tagged UbV.ABKRD13B.2 (1.7 μg) or Flag-tagged Ub.wt (1.7 μg). For cells transfected only with the HA-tagged USP28 expression plasmid, empty pcDNA3.1 vector was added to supplement to a total of 2.5 μg of plasmid DNA transfected per well of a 6-well plate. For analysis of the effect of UbV.USP28 on endogenous USP28, Flag-tagged UbV.USP28 (1.7 μg) or Flag-tagged Ub.wt were transfected into HeLa cells as described above. 48 hours after transfection, cells were washed 3 times with ice-cold PBS and were lysed for 30 minutes at 4 °C in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40 (nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol, Sigma), 1 mM DTT, 1 mM Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate (Sigma). Cell debris and DNA were removed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm and 4 °C for 15 minutes, supernatant was collected, and protein concentration was determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Immunoblotting

40 μg whole cell lysate was loaded onto a reducing SDS-PAGE, and following electrophoretic separation, proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Merck Millipore) as described above. Membranes were blocked with Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5% skimmed milk (TBSM) at 25 °C, with gentle agitation for 2 hours. Blocked membranes were incubated at 4 °C with gentle agitation overnight with the following primary antibodies: 4 μg/ml anti-MYC/c-MYC (clone sc-40, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 4 μg/ml anti-USP28 (ab7089, Abcam), 0.5 μg/ml mouse anti-HA tag (clone HA-7, Sigma), and 0.44 μg/ml anti-GAPDH (clone FF26A, Abcam) in TBSM buffer containing 0.05% Tween-20. Blots were washed three times for 10 minutes with TBST (Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) and incubated at 25 °C with gentle agitation for 1 hour with anti-mouse IgG HRP-conjugated antibody (clone 7076, diluted 1:1,000, Cell Signalling Technology). For detection of Flag-tagged UbV.USP28 and Ub.wt, membranes were incubated with anti-Flag-tag-HRP conjugated antibody (diluted 1:1,000, Sigma) for 2 hours at 25 °C, with gentle agitation. Following secondary antibody binding, membranes were washed as previously described, developed using the ECL Plus substrate (Thermo Fisher) and imaged with X-ray films.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Peptide motifs embedded in intracellular proteins play a major role in protein networks essential for cell physiology. Ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs) are short α-helices that help to interpret the complex ubiquitin code into cell signals. Dysregulated UIM activity has been implicated in several diseases, but their characterization has been hampered by a lack of probes that can recognize UIMs with high affinity and specificity. We developed engineered ubiquitin variants (UbVs) able to target UIMs with exquisite specificity. We showed that UbVs can act as inhibitors of ubiquitin-specific proteases and may be useful tools for validation of potential therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. A. de Marco (University of Nova Gorica) for Erv1p and DsbC plasmids. We are grateful to Mr. J. Tang, Dr. N. Yang, Dr. K. Davis and Dr. M. Ustav Jr. for useful discussions, and Mrs. M.P. Mercado for technical help with IC50 measurements. Funding was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant MOP-93684 (S.S.S) and foundation grant to F.S. Research was conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines, which are funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the National Institutes of Health (P30 GM124165). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Abbreviations

- DUB

deubiquitinase

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- Ub

ubiquitin

- UBD

ubiquitin-binding domain

- UbV

ubiquitin variant

- UIM

ubiquitin-interacting motif

- UPS

ubiquitin proteasome system

- USP

ubiquitin-specific protease

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- (1).Zhang X; Smits AH; Tilburg G. B. A. van; Jansen PWTC; Makowski MM; Ovaa H; Vermeulen M An Interaction Landscape of Ubiquitin Signaling. Molecular Cell 2017, 65 (5), 941–955.e8. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Hammond-Martel I; Yu H; Affar EB Roles of Ubiquitin Signaling in Transcription Regulation. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24 (2), 410–421. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Grumati P; Dikic I Ubiquitin Signaling and Autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293 (15), 5404–5413. 10.1074/jbc.TM117.000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Hu H; Sun S-C Ubiquitin Signaling in Immune Responses. Cell Res 2016, 26 (4), 457–483. 10.1038/cr.2016.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Rape M Ubiquitylation at the Crossroads of Development and Disease. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2018, 19 (1), 59–70. 10.1038/nrm.2017.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Komander D; Clague MJ; Urbé S Breaking the Chains: Structure and Function of the Deubiquitinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009, 10 (8), 550–563. 10.1038/nrm2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Swatek KN; Komander D Ubiquitin Modifications. Cell Res 2016, 26 (4), 399–422. 10.1038/cr.2016.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Wickliffe KE; Williamson A; Meyer H-J; Kelly A; Rape M K11-Linked Ubiquitin Chains as Novel Regulators of Cell Division. Trends Cell Biol 2011, 21 (11), 656–663. 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Akutsu M; Dikic I; Bremm A Ubiquitin Chain Diversity at a Glance. J Cell Sci 2016, 129 (5), 875–880. 10.1242/jcs.183954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Randles L; Walters KJ Ubiquitin and Its Binding Domains. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012, 17, 2140–2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Veggiani G; Sidhu SS Peptides Meet Ubiquitin: Simple Interactions Regulating Complex Cell Signaling. Peptide Science 2019, 111 (1), e24091. 10.1002/pep2.24091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hurley JH; Lee S; Prag G Ubiquitin-Binding Domains. Biochem J 2006, 399 (Pt 3), 361–372. 10.1042/BJ20061138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lange OF; Lakomek N-A; Farès C; Schröder GF; Walter KFA; Becker S; Meiler J; Grubmüller H; Griesinger C; de Groot BL Recognition Dynamics up to Microseconds Revealed from an RDC-Derived Ubiquitin Ensemble in Solution. Science 2008, 320 (5882), 1471–1475. 10.1126/science.1157092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Berke SJS; Chai Y; Marrs GL; Wen H; Paulson HL Defining the Role of Ubiquitin-Interacting Motifs in the Polyglutamine Disease Protein, Ataxin-3. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280 (36), 32026–32034. 10.1074/jbc.M506084200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Miller SLH; Malotky E; O’Bryan JP Analysis of the Role of Ubiquitin-Interacting Motifs in Ubiquitin Binding and Ubiquitylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279 (32), 33528–33537. 10.1074/jbc.M313097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Fisher RD; Wang B; Alam SL; Higginson DS; Robinson H; Sundquist WI; Hill CP Structure and Ubiquitin Binding of the Ubiquitin-Interacting Motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278 (31), 28976–28984. 10.1074/jbc.M302596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Isasa M; Katz EJ; Kim W; Yugo V; González S; Kirkpatrick DS; Thomson TM; Finley D; Gygi SP; Crosas B Monoubiquitination of RPN10 Regulates Substrate Recruitment to the Proteasome. Molecular Cell 2010, 38 (5), 733–745. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]