Abstract

To evaluate the impact of a community health worker intervention (CHW) (referred to as Personalized Support for Progress (PSP)) on all-cause health care utilization and cost of care compared with Enhanced Screening and Referral (ESR) among women with depression. A total of 223 patients (111 in PSP and 112 in ESR randomly assigned) from three women’s health clinics with elevated depressive symptoms were enrolled in the study. Their electronic health records were queried to extract all-cause health care encounters along with the corresponding billing information 12 months before and after the intervention, as well as during the first 4-month intervention period. The health care encounters were then grouped into three mutually exclusive categories: high-cost (> US$1000 per encounter), medium-cost (US$201–$999), and low-cost (≤ US$200). A difference-in-difference analysis of mean total charge per patient between PSP and ESR was used to assess cost differences between treatment groups. The results suggest the PSP group was associated with a higher total cost of care at the baseline; taking this baseline difference into account, the PSP group was associated with lower mean total charge amounts (p = 0.008) as well as a reduction in the frequency of high-cost encounters (p < 0.001) relative to the ESR group during the post-intervention period. Patient-centered interventions that address unmet social needs in a high-cost population via CHW may be a cost-effective approach to improve quality of care and patient outcomes.

Keywords: Health care economics, Patient navigation, Women’s health, Mental health, Emergency department utilization, Social determinants of health

Introduction

Depression is among the most burdensome disorders in the USA and abroad, causing a negative impact on quality of life, economic productivity, and health care costs (Bruffaerts et al. 2012; Greenberg et al. 2015; Ustun et al. 2004). In the USA, major depressive disorder accounts for 400 million disability days per year and represents an economic burden of greater than $80 million per year when considering the direct medical costs, suicide-related mortality costs, and indirect workplace costs (Greenberg et al. 2015; Greenberg et al. 2003; Merikangas et al. 2007). Furthermore, patients with depression have higher rates of health care utilization and greater health care costs, particularly with emergency department (ED) visits, when compared with patients of similar age, sex, and chronic conditions without depression (Chiu et al. 2017; Wammes et al. 2018). Other factors common among individuals with depression, such as unmet social needs, exacerbate the economic burden of depression, especially in reproductive-aged women (Chechulin et al. 2014; Fitzpatrick et al. 2015; Garg et al. 2015; Wammes et al. 2018). Indeed, this population of reproductive-aged women must frequently rely on governmental support for income, childcare, insurance, and housing (Hildebrandt and Stevens 2009; Narain et al. 2017). These services account for some of the invisible costs of depression that also interfere with improvement of depression and self-sufficiency and contribute to the intergenerational cycle of poverty (Casey et al. 2004; Garg et al. 2015; Toy et al. 2016).

Community health workers (CHW) show promise to mitigate the costs associated with depression by helping address unmet social needs and connect vulnerable populations to appropriate health and support services, and evidence indicates that CHWs may decrease unnecessary health care utilization (Enard and Ganelin 2013). CHWs can serve as important links in the health care system between patients and providers and help vulnerable patients by addressing structural barriers (transportation, child care, applying for public assistance programs), language barriers (interpretation, literacy), care coordination barriers (scheduling appointments or referrals), and psychological barriers (fear, distrust, or anxiety) (Freeman and Rodriguez 2011; Natale-Pereira et al. 2011). With close ties to their communities, CHWs represent trusted members of the health care team, and they can extend that trust to the rest of the health care system (Carroll et al. 2010; Han et al. 2009; Petereit et al. 2008).

This study investigates the impact of Personalized Support for Progress (PSP), a prioritization-based CHW intervention for marginalized women with depression, compared with the lower intensity, enhanced standard of care model called Enhanced Screening and Referral (ESR) on the all-cause total cost of care for 12 months before and after the intervention. Personalized Support for Progress is a patient-centered, CHW intervention using a decision aid to identify patients’ prioritized needs based on self-determination theory (SDT) to facilitate experiences of autonomy, competence, and relatedness to improve depression and quality of life (Rousseau et al. 2014; Ryan and Deci 2000). A previously published evaluation of PSP has demonstrated participant satisfaction and improvements in depression in both treatment groups (Poleshuck et al. 2019). As a follow-up to the previous study, this subsequent analysis seeks to understand the impact of the PSP intervention on the all-cause total cost of care to determine the broader feasibility and sustainability of this patient-centered, CHW-based intervention on a population with high health care expenditures and unmet social needs. The hypothesis was that the women who were in the PSP group incurred a lower total cost of care and utilized fewer all-cause high-cost care, including visits to ED or inpatient admissions, than the women in the ESR group.

Methods

The data used for this study were extracted from the electronic health records (EHR) and the corresponding billing data obtained from the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) EHR database. More detailed descriptions of the subjects, procedures, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and protection of human subjects are described elsewhere (Poleshuck et al. 2015; Poleshuck et al. 2019). The University of Rochester’s Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study.

In summary, study participants were identified by research assistants who screened for depressive symptoms via the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) in the waiting rooms of three URMC urban women’s health clinics in Rochester, NY, from January 2014 to October 2015. Women with elevated depressive symptoms (PHQ9 ≥ 10) who consented, regardless of pregnancy status, were enrolled and randomized to either PSP or ESR. Each participant randomized to the PSP intervention group was then partnered with a CHW who provided customized support around using a decision aid to identify priorities and develop plans to address them. The CHW then worked with and supported the participants in addressing these prioritized areas for 4 months. For the PSP group, the frequency and type of contact were participant-driven, varying from monthly phone calls to weekly visits. On the other hand, those randomized to the ESR group were provided with a resource list with information specifying where they could obtain assistance with issues they identified. Enhanced Screening and Referral participants then received monthly check-in phone calls until the end of the 4-month intervention period. The CHW was not informed that health care costs would be evaluated as an outcome of the project; therefore, it is highly unlikely that the CHW might have altered her behavior to consciously accommodate this aspect of the study.

Health care costs were measured by charge amount for all health care encounters including professionally billed data, hospitalizations, labs, supplies, room charges, and facilities charges at all sites within the URMC health record billing database 12 months before and after the intervention, as well as during the 4-month intervention. Costs from all the encounters were divided into 3 mutually exclusive categories based on the per encounter charge amounts: high-cost encounters (> US$1000 per encounter), medium-cost encounters (US$201–$999), and low-cost encounters (≤ US$200). These cut-off points were determined based on the distribution of the charge data. Examples of high-cost encounters include visits to the ED, which comprise 21% of all high-cost encounters in this dataset, and inpatient encounters related to labor and delivery (L&D), which account for approximately 12%, with the remaining departments contributing 5% or less. Examples of departments in the medium-cost encounters are obstetrics and gynecology (OB-GYN) outpatient visits (15%) and microbiology (12%), with all other departments contributing 5% or less. Low-cost departments included inpatient pharmacy (16%), chemistry labs (14%), and phlebotomy (11%), with the remaining departments again contributing 5% or less.

Four dependent variables were examined: total per patient charge dollar amount per period along with per patient counts of high, medium, and low-cost encounters per period. To estimate the PSP impact on these dependent variables relative to ESR, a difference-in-difference (DD) approach was used. The DD approach explicitly takes into account the possibility that there may be pre-intervention baseline differences between the PSP and ESR groups in terms of the dependent variables. Although the random selection of patients into either group reduces the likelihood of this possibility, the DD approach ensures that the post-intervention differences observed in the data are not confounded by such baseline differences.

To implement the DD approach, a set of multivariate regression models were used corresponding to each of the dependent variables. The explanatory variables were an indicator variable that equals 1 if the patient was randomized to the PSP group and zero otherwise (i.e., ESR being the reference) and another indicator variable that indicates the observation period—“pre,” “during,” or “post,” with “pre” serving as the reference—and a set of interaction terms between the PSPESR indicator and the observation period indicators. The coefficients on the interaction terms therefore represented the PSP intervention effect.

An ordinary least square regression model was used to fit the charge data, while Poisson models were used to fit the counts of high-, medium-, and low-cost encounters (to account for the discrete nature of these dependent variables). Because the same patients were observed multiple times in the data, clustered standard errors were estimated to account for the intra-person correlation of the error terms. To translate the coefficient estimates obtained from the regression models into corresponding estimates in terms of the dependent variables, “observed” and “expected” values were calculated. That is, observed values represented the post-intervention values of the dependent variables among the PSP group as observed in the data. Expected values were then calculated by setting the coefficients on the aforementioned interaction terms in the regression model to zero—that is, the expected value of the dependent variables had the PSP patient had been enrolled in ESR instead of PSP. The differences between the observed and expected values therefore represented the PSP intervention effect, accounting for the pre-intervention baseline differences between the two groups. A p value of 0.05 or lower was used to represent statistical significance.

Results

The initial trial findings have been published elsewhere (Poleshuck et al. 2019). A total of 225 women were randomized; 2 were withdrawn from the final analysis due to later discovering that they did not meet eligibility criteria. The final sample included 223 participants, 111 in PSP and 112 in ESR. Randomization balance for demographics and baseline variables was assessed using a conservative p value of < 0.20. This was a racially/ethnically diverse population of women (76.2% of identified as a race other than White/Caucasian), 30% of whom were pregnant at the time of the study, with significant unmet social needs (Poleshuck et al. 2019). There were no group differences in pregnancy status, insurance status, illicit substance use, or unmet social needs (Poleshuck et al. 2019). In the PSP group, the frequency of CHW visits over the course of the intervention was participant-driven and was distributed as follows: 7% of the participants had zero visits, 25% had one or two visits, 22% had three visits, 20% had four or five visits, 22% had six to nine visits, and 4% had 10 or more visits.

In terms of health care costs, the pre-intervention comparison of the PSP participants to the ESR participants suggested that despite the randomization, the PSP participants had marginally more high-cost encounters (p = 0.076) (Table 1). Taking into account such baseline differences, however, the DD analysis found that the PSP participants were associated with a statistically significant reduction of approximately 34% in total charge amounts during the post-intervention period (p = 0.008; Table 2). Moreover, consistent with the pattern observed in the total cost of care, the DD analysis showed a statistically significant reduction in the frequency of high-cost encounters (p < 0.001, Table 3). On the other hand, the DD estimates for the PSP impact on medium- and low-cost encounters were not statistically significant (p = 0.132 and p = 0.135; Tables 4 and 5, respectively).

Table 1.

Pre-intervention baseline comparisons

| Variable | PSP (n = 112) | ESR (n = 111) | Difference | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total mean charge per patient | $17,062 | $13,066 | $3996 | [9839, −1848] | 0.179 |

| Frequency of high-cost encounters per patient | 4.53 | 2.85 | 1.68 | [3.54, −0.18] | 0.076 |

| Frequency of medium-cost encounters per patient | 18.60 | 16.38 | 2.22 | [6.86, −2.41] | 0.346 |

| Frequency of low-cost encounters per patient | 23.74 | 20.68 | 3.05 | [10.17, −4.06] | 0.399 |

Table 2.

Difference-in-difference estimates of mean total charge per patient

| Time interval | Observed mean total charge among PSP | Expected mean total charge among PSP | Difference | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (12-month total) | $17,062 | $17,062 | – | – |

| During (4-month total) | $11,022 | $12,608 | −$1586 | 0.588 |

| Post (12-month total) | $14,814 | $22,339 | −$7525 | 0.008 |

Table 3.

Difference-in-difference estimate of PSP impact on high-cost encountersa

| Time interval | Observed mean high-cost encounters among PSP | Expected mean high-cost encounters among PSP | Difference | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (12-month total) | 4.53 | 4.53 | – | – |

| During (4-month total) | 3.39 | 4.05 | −0.66 | 0.524 |

| Post (12-month total) | 3.64 | 7.95 | −4.31 | <0.001 |

High-cost departments included visits to the emergency department (21%) and inpatient encounters related to labor and delivery (12%), with the remaining departments contributing 5% or less

Table 4.

Difference-in-difference estimate of PSP impact on medium-cost encountersa

| Time interval | Observed mean medium-cost encounters among PSP | Expected mean medium-cost encounters among PSP | Difference | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (12-month total) | 18.60 | 18.60 | – | – |

| During (4-month total) | 9.24 | 9.65 | −0.42 | 0.719 |

| Post (12-month total) | 17.18 | 20.19 | −3.01 | 0.132 |

Medium-cost departments included outpatient OB-GYN (15%) and microbiology (12%), with the remaining departments contributing 5% or less

Table 5.

Difference-in-difference estimate of PSP impact on low-cost encountersa

| Time interval | Observed mean low-cost encounters among PSP | Expected mean low-cost encounters among PSP | Difference | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (12-month total) | 23.74 | 23.74 | – | – |

| During (4-month total) | 13.20 | 15.02 | −1.82 | 0.463 |

| Post (12-month total) | 19.59 | 24.42 | −4.83 | 0.135 |

Low-cost departments included inpatient pharmacy (16%), chemistry laboratory (14%), and phlebotomy (11%), with the remaining departments contributing 5% or less

Discussion

The purpose of this analysis was to determine the impact of PSP, a CHW intervention, on health care utilization and cost of care for women with co-occurring depression and socioeconomic disadvantage. Our findings suggest a significant reduction in health care costs in the 12-month post-intervention period for the PSP group. The results indicated that the cost savings are largely driven by a decrease in the frequency of high-cost visits, and the departments that housed that largest percentage of high-cost visits were the ED (21%) and inpatient hospital visits related to L&D (12%).

These findings are aligned with prior studies that showed that CHW interventions are associated with decreased odds of returning to the ED in some populations (Enard and Ganelin 2013). Our findings support a growing body of evidence that CHW interventions to address unmet social needs are not only highly satisfactory for patients; they may also positively impact health care utilization (Bhaumik et al. 2013; Karnick et al. 2007; Sadowski et al. 2009; Taylor et al. 2016; Woods et al. 2012).

The women in this study represent a group with significant unmet social needs and mental health needs; one-third of the participants were pregnant at the time of the intervention, adding an additional layer of complexity and risk for being high-cost patients. Given that the women in this study were recruited from OB-GYN offices, that a significant percentage of women in the study were pregnant, and that non-White/Caucasian race and poverty are significantly correlated with increased maternal morbidity and mortality, it is not surprising that the second most frequent high-cost department in this study was L&D (Chechulin et al. 2014; Fitzpatrick et al. 2015; Wammes et al. 2018). These factors make this population an important group to target with low-cost, patient-centered, satisfactory, and helpful interventions given the negative individual, family, and community impacts of not addressing these factors, as well as the potential cost savings associated with assisting this population. Given the benefits of CHW interventions in improving patient outcomes and satisfaction, CHWs are valuable members of the health care team. As demand for CHW interventions grow, adequate compensation for CHW that equals their contributions should follow (Rush 2012).

The results suggest that cost of care increased over time, as indicated by the “expected” mean total charges in Table 2 (from $17,062 per patient during the pre-12-month period to $22,339 during the post-12-month period). The “expected” mean costs were obtained based on what the ESR group experienced over time in terms of health care utilization and costs. One reason for this increase is the secular trends in healthcare price (i.e., inflation). Another potential reason is that many of the patients who were pregnant during the pre-intervention period gave birth during the post-intervention period, which would lead to a higher cost of care. This study was not designed to examine specifically how the intervention might have impacted pregnancy-related care utilization and cost, and therefore, this aspect of the intervention remains a topic of future research.

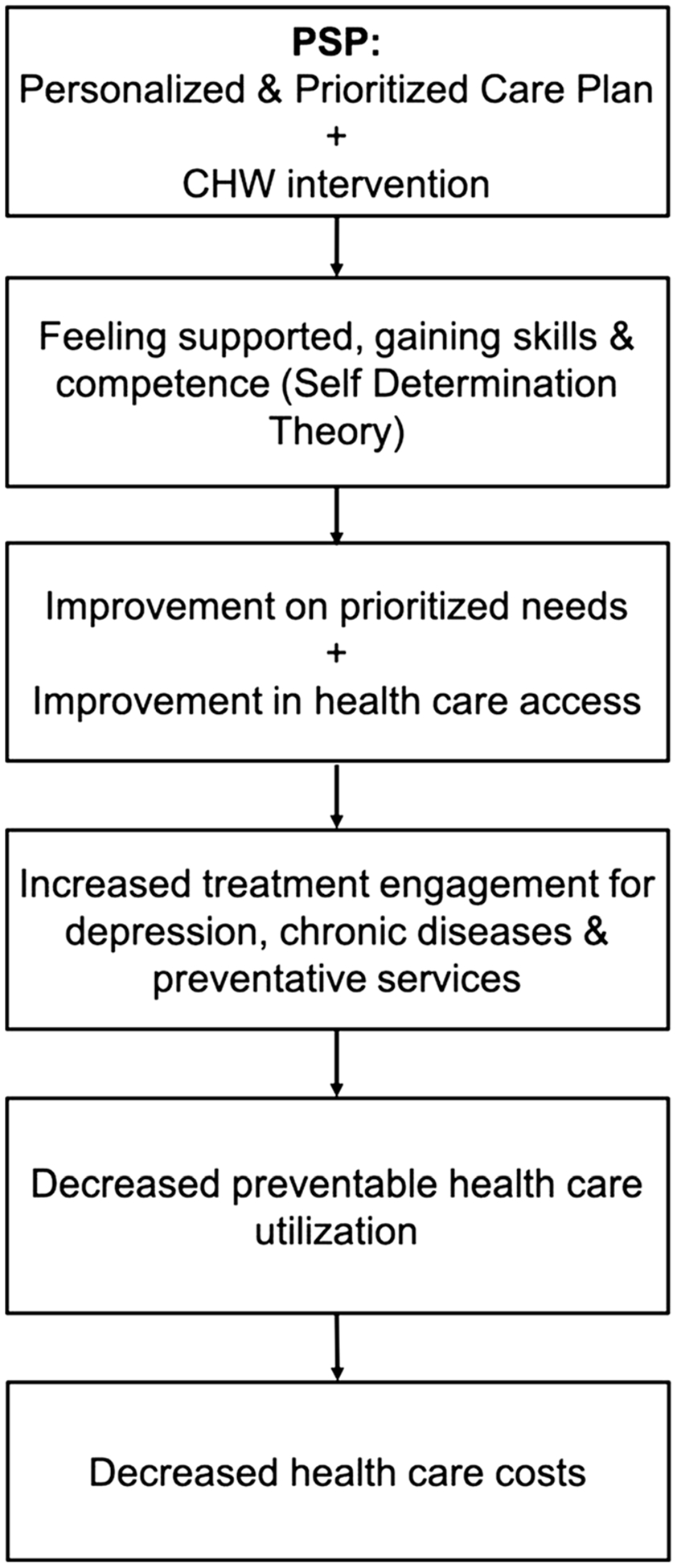

While understanding how PSP reduced costs is beyond the scope of this project, we have hypotheses worth further exploration in future studies. We believe that by offering support, assistance with health care navigation, and increased patient autonomy, the patients experienced enhanced feelings of connectedness and increased engagement in treatment for depression, chronic diseases, and preventative services, thus leading to lower utilization of avoidable costly acute care and decreased total cost of care (Fig. 1). This conceptual model aligns with prior studies that have showed that CHW interventions improve patient satisfaction and decrease unnecessary ED visits (Enard and Ganelin 2013). While we do not have the sample size to further investigate the relationships between the frequency and intensity of CHW contact, improvement in participant depression scores, and cost reduction, we hope that this study provides a solid foundation for subsequent studies to examine these relationships. Furthermore, future studies will help elucidate whether support through the CHW intervention was enough to reduce costs, or if the connections to preventative health care services including mental health that the CHW helped forge reduced avoidable costly acute visits, or a combination of the two.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized model for PSP intervention. Boxes correspond to each step in the model, and arrows between connect one step to the next. The PSP intervention provides a personalized care plan that is prioritized for the patient’s needs, as well as a CHW who provides health care navigation and both logistical and peer support using the self-determination theory, or “SDT” (Ryan and Deci 2000). SDT allows patients to feel supported, gaining skills and competence, leading to improvement in their prioritized needs, as well as the CHW interventions that improve access to health care services. This leads to increased engagement in treatment for depression, chronic diseases, and preventative services, which decreases preventable health care use and decreased costs

Limitations

The cost data in this study are uniquely robust given its inclusion of facilities billing data in addition to professionally billed data, which is often difficult to obtain in cost analyses. However, the data used for this study may be subject to measurement error due to the fact that patient health records may not be accurately aligned with the corresponding billing data. Additionally, this analysis has relied on charge amounts rather than actual reimbursement amounts from payers. This implies that the reported dollar amounts of the total cost of care reductions cannot be translated directly to actual reductions in expenditures by the payer because charge amounts are not equivalent to the amounts paid by payers or patients. Furthermore, the analysis only includes costs and care utilizations incurred within the URMC system; it does not include costs from visits at other unaffiliated health centers or independent providers. While there are two major hospital systems in the Rochester, NY, area, all women from this study were recruited from URMC OB-GYN clinics. Similarly, this study did not include some of the hidden costs of depression, such as workplace costs and governmental subsidies for disability and other supports. While accounting for the non-health care related expenses is beyond the scope of this study, these costs are unaccounted for and therefore underestimate the true cost of depression. For example, there are significant adverse health and economic costs to children of mothers with perinatal anxiety and depression (Bauer et al. 2016). We were not able to assess the costs to children in this study but hope it will be addressed in future studies.

Table 1 also indicates that there were non-trivial baseline differences between the PSP intervention and the ESR groups, albeit the differences are not statistically significant. These differences exist despite the fact that the selection of patients into either group was randomly determined; as such, it is not clear how and why they exist. Although the difference-indifference approach adopted in this study explicitly accounts for them in the analysis, and thus our results are robust to them, it is still not clear if our results may yet be subject to some unobserved confounders.

Lastly, the presence of “super-utilizers”—generally defined as a small number of patients who account for a disproportionately large portion of the total health care utilization and costs (Wammes et al. 2018; Zook and Moore 1980)— requires a more nuanced interpretation of the results. Statistically, super-utilizers can be seen as outliers due to their small numbers, but because they account for such a large portion of the total healthcare utilization and spending, they warrant closer examinations. In this study, however, due to the small sample size of such super-utilizers in the data, it is not feasible to do so. Moreover, currently there is a lack of consensus on how to define “super-utilizers” and a different conceptual framework is needed to examine the relationship between the super-utilizers and the cost savings (Johnson et al. 2015).

Conclusion

Adopting effective and sustainable patient-centered interventions is of increasing importance in light of the Triple Aim, a well-known and regarded framework in population health, to improve care and health outcomes while improving patient experience and reducing costs (Berwick et al. 2008). Our study suggests that CHW interventions like PSP have the potential to reduce health care costs and improve patient experience through decreasing the frequency of costly ED and inpatient hospital visits. Given the benefits of CHW interventions and their value as members of the health care team, adequate compensation for CHW that matches their contributions is necessary (Rush 2012). Further research is needed to understand how CHWs effectively reduce costs and to determine if the cost savings of the intervention offset the cost of implementation, making it a sustainable intervention that is beneficial to patients and has a positive impact on health care utilization and total cost of care.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support from the University of Rochester School of Medicine’s Babigian Summer Research Fellowship and the Department of Psychiatry for funding the cost analysis; we also acknowledge and thank the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, AD-12-4261, for funding the randomized comparative effectiveness trial.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards The University of Rochester’s Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study. All aspects of this study where performed in accordance with institutional ethical standards and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bauer A, Knapp M, Parsonage M (2016) Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. J Affect Disord 192:83–90. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J (2008) The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 27:759–769. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaumik U, Norris K, Charron G, Walker SP, Sommer SJ, Chan E, Dickerson DU, Nethersole S, Woods ER (2013) A cost analysis for a community-based case management intervention program for pediatric asthma. J Asthma 50:310–317. 10.3109/02770903.2013.765447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruffaerts R, Vilagut G, Demyttenaere K, Alonso J, Alhamzawi A, Andrade LH, Benjet C, Bromet E, Bunting B, de Girolamo G, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, He Y, Hinkov H, Hu C, Karam EG, Lepine JP, Levinson D, Matschinger H, Nakane Y, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Scott KM, Varghese M, Williams DR, Xavier M, Kessler RC (2012) Role of common mental and physical disorders in partial disability around the world. Br J Psychiatry 200:454–461. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.097519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JK, Humiston SG, Meldrum SC, Salamone CM, Jean-Pierre P, Epstein RM, Fiscella K (2010) Patients’ experiences with navigation for cancer care. Patient Educ Couns 80:241–247. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey P, Goolsby S, Berkowitz C, Frank D, Cook J, Cutts D, Black MM, Zaldivar N, Levenson S, Heeren T, Meyers A (2004) Maternal depression, changing public assistance, food security, and child health status. Pediatrics 113:298–304. 10.1542/peds.113.2.298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chechulin Y, Nazerian A, Rais S, Malikov K (2014) Predicting patients with high risk of becoming high-cost healthcare users in Ontario (Canada). Healthc Policy 9:68–79 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3999564/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu M, Lebenbaum M, Cheng J, de Oliveira C, Kurdyak P (2017) The direct healthcare costs associated with psychological distress and major depression: a population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One 12:e0184268. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enard KR, Ganelin DM (2013) Reducing preventable emergency department utilization and costs by using community health workers as patient navigators. J Healthc Manag 58:412–427 discussion 428 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4142498/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick T, Rosella LC, Calzavara A, Petch J, Pinto AD, Manson H, Goel V, Wodchis WP (2015) Looking beyond income and education: socioeconomic status gradients among future high-cost users of health care. Am J Prev Med 49:161–171. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL (2011) History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 117:3539–3542. 10.1002/cncr.26262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Cook J, Cordella N (2015) Influence of maternal depression on household food insecurity for low-income families. Acad Pediatr 15:305–310. 10.1016/j.acap.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, Pike CT, Kessler RC (2015) The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry 76:155–162. 10.4088/JCP.14m09298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, Leong SA, Lowe SW, Berglund PA, Corey-Lisle PK (2003) The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry 64:1465–1475. 10.4088/jcp.v64n1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han HR, Lee H, Kim MT, Kim KB (2009) Tailored lay health worker intervention improves breast cancer screening outcomes in non-adherent Korean-American women. Health Educ Res 24:318–329. 10.1093/her/cyn021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt E, Stevens P (2009) Impoverished women with children and no welfare benefits: the urgency of researching failures of the temporary assistance for needy families program. Am J Public Health 99(5):793–801. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.106211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TL, Rinehart DJ, Durfee J, Brewer D, Batal H, Blum J, Oronce CI, Melinkovich P, Gabow P (2015) For many patients who use large amounts of health care services, the need is intense yet temporary. Health Aff (Millwood) 34:1312–1319. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnick P, Margellos-Anast H, Seals G, Whitman S, Aljadeff G, Johnson D (2007) The pediatric asthma intervention: a comprehensive cost-effective approach to asthma management in a disadvantaged innercity community. J Asthma 44:39–44. 10.1080/02770900601125391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Ames M, Cui L, Stang PE, Ustun TB, Von Korff M, Kessler RC (2007) The impact of comorbidity of mental and physical conditions on role disability in the US adult household population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:1180–1188. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narain K, Bitler M, Ponce N, Kominski G, Ettner S (2017) The impact of welfare reform on the health insurance coverage, utilization and health of low education single mothers. Soc Sci Med 180:28–35. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natale-Pereira A, Enard KR, Nevarez L, Jones LA (2011) The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer 117: 3543–3552. 10.1002/cncr.26264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petereit DG, Molloy K, Reiner ML, Helbig P, Cina K, Miner R, Spotted Tail C, Rost C, Conroy P, Roberts CR (2008) Establishing a patient navigator program to reduce cancer disparities in the American Indian communities of Western South Dakota: initial observations and results. Cancer Control 15:254–259. 10.1177/107327480801500309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poleshuck E, Wittink M, Crean H, Gellasch T, Sandler M, Bell E, Juskiewicz I, Cerulli C (2015) Using patient engagement in the design and rationale of a trial for women with depression in obstetrics and gynecology practices. Contemp Clin Trials 43:83–92 doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poleshuck E, Wittink M, Crean HF, Juskiewicz I, Bell E, Harrington A, Cerulli C (2019) A comparative effectiveness trial of two patient-centered interventions for women with unmet social needs: Personalized Support for Progress and Enhanced Screening and Referral. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 10.1089/jwh.2018.7640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau SJ, Humiston SG, Yosha A, Winters PC, Loader S, Luong V, Schwartzbauer B, Fiscella K (2014) Patient navigation moderates emotion and information demands of cancer treatment: a qualitative analysis. Support Care Cancer 22:3143–3151. 10.1007/s00520-014-2295-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CH (2012) Return on investment from employment of community health workers. J Ambul Care Manage 35:133–137. 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31822c8c26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 55:68–78. 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, Buchanan D (2009) Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. Jama 301:1771–1778. 10.1001/jama.2009.561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LA, Tan AX, Coyle CE, Ndumele C, Rogan E, Canavan M, Curry LA, Bradley EH (2016) Leveraging the social determinants of health: what works? PLoS One 11:e0160217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0160217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toy S, Tripodis Y, Yang K, Cook J, Garg A (2016) Influence of maternal depression on WIC participation in low-income families. Matern Child Health J 20:710–719. 10.1007/s10995-015-1871-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustun TB, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chatterji S, Mathers C, Murray CJ (2004) Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000. Br J Psychiatry 184:386–392. 10.1192/bjp.184.5.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wammes JJG, van der Wees PJ, Tanke MAC, Westert GP, Jeurissen PPT (2018) Systematic review of high-cost patients’ characteristics and healthcare utilisation. BMJ Open 8:e023113. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods ER, Bhaumik U, Sommer SJ, Ziniel SI, Kessler AJ, Chan E, Wilkinson RB, Sesma MN, Burack AB, Klements EM, Queenin LM, Dickerson DU, Nethersole S (2012) Community asthma initiative: evaluation of a quality improvement program for comprehensive asthma care. Pediatrics 129:465–472. 10.1542/peds.2010-3472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zook CJ, Moore FD (1980) High-cost users of medical care. N Engl J Med 302:996–1002. 10.1056/nejm198005013021804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]