Abstract

Objective

This study was conducted to assess the prevalence of intestinal parasites and the associated factors among food handlers in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Design

An institution-based, cross-sectional study design was used. Stool samples were collected from food handlers and examined using direct wet mount and formalin-ether concentration techniques. Personal and establishment-related information was collected using a pretested questionnaire, with a structured observation. Multivariable binary logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with the prevalence of intestinal parasites on the basis of adjusted OR (AOR) and 95% CI and p values <0.05.

Setting

Food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Participants

411 food handlers participated in the study.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the prevalence of intestinal parasites, defined as the presence of one or more intestinal parasitic species in stool samples.

Results

One or more intestinal parasites were detected in 171 (41.6%; 95% CI 36.6% to 46.4%) stool samples. The most common intestinal parasites were Entamoeba histolytica/dispar (12.7%), Giardia duodenalis (11.2%) and Ascaris lumbricoides (8.3%). The presence of intestinal parasites among food handlers was associated with low monthly income (AOR: 2.83, 95% CI 1.50 to 8.84), untrimmed fingernails (AOR: 4.36, 95% CI 1.98 to 11.90), no food safety training (AOR: 2.51, 95% CI 1.20 to 5.58), low level of education (AOR: 3.13, 95% CI 1.34 to 7.44), poor handwashing practice (AOR: 2.16, 95% CI 1.03 to 4.22) and lack of medical check-up (AOR: 2.31, 95% CI 1.18 to 6.95).

Conclusion

The prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers in food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa was high. The presence of intestinal parasites was linked to socioeconomic conditions, poor hand hygiene conditions and absence of food safety training. It is crucially important to promote handwashing practices and provide food hygiene and safety training in these settings.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Public health, PARASITOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study focused on a key group (food handlers) that has potential to spread foodborne infections to consumers.

The use of sensitive diagnostic techniques and a combination of methods with triplicate examinations would have led to an improved rate of recovered intestinal parasites in this study that would better indicate the true prevalence.

The use of a single stool sample might have affected the results of parasitic examinations since the sensitivity of the direct smear examination technique is reduced when a single stool sample is examined, and the formalin-ether concentration technique might have also damaged parasite eggs.

Introduction

Foodborne diseases are increasingly becoming a serious global public health problem. WHO estimates indicate that each year worldwide, unsafe food causes 600 million cases of foodborne diseases and 420 000 deaths. The WHO estimated that globally each year 33 million years of healthy lives are lost due to eating unsafe food and this number is likely an underestimate.1 One of the causes of foodborne diseases is contamination during food preparation; food handlers carrying pathogens might be the origin of this condition. Foods can be contaminated with faecal materials at the point of production or during food preparation at both home and commercial premises.2 Food handlers with poor personal hygiene and inadequate knowledge of food safety could be potential sources of infections. Food handlers who harbour and excrete enteropathogens may contaminate the food through their hands contaminated with faeces, or through transmission to food or food contact surfaces, and finally to healthy individuals.3–7

The contribution of infected food workers (whether symptomatic or not) to foodborne disease outbreaks has been difficult to establish. However, reports showed that food workers in many settings have been responsible for foodborne disease outbreaks for decades. For instance, members of the Committee on Control of Foodborne Illnesses of the International Association for Food Protection analysed 816 foodborne disease outbreaks with 80 682 cases in different countries where food workers were implicated as the source of the contamination. The report also estimated that infected food workers were documented as responsible for 18% of 766 outbreaks occurring in the USA.8 9 Moreover, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as cited in Mathew et al,10 20%–40% of foodborne illnesses associated with consumption of contaminated food originated from catering establishments.10

Food handling personnel play a role in the transmission of foodborne diseases. The health of food handlers is of great importance in maintaining the quality of food products. Accordingly, pre-employment and periodic medical check-ups are very important to safeguard consumers from getting diseases from contaminated foods, along with other food safety measures.11 12 However, pre-employment and periodic medical check-ups are not commonly practised in Ethiopia. As a result, many of the food handlers working in different food establishments all over the country may harbour one or more enteropathogens. For instance, a systematic review and meta-analysis reported that the overall pooled prevalence estimate of intestinal parasites among food handlers in food service establishments in Ethiopia was 33.6% (95% CI 27.6% to 39.6%),13 and the common factors associated with high prevalence of intestinal pathogens among them are poor hand hygiene, inadequate access to water and sanitation facilities, and poor socioeconomic conditions.13–18 However, the prevalence and risk factors may be different across various settings. Accordingly, this study was conducted to assess the prevalence of intestinal parasites and the associated factors among food handlers working in food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and setting

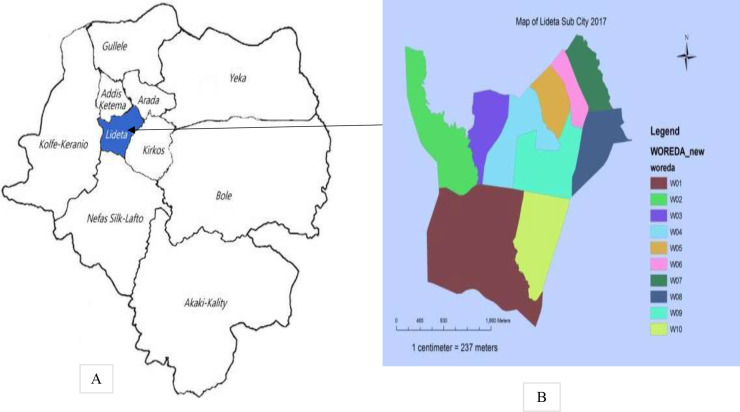

This an institution-based, cross-sectional study with laboratory investigations conducted in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa from 20 March to 20 April 2021. The Lideta subcity is one of the 10 subcities of Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. The subcity is located at the global positioning system coordinates of 9°0′N and 38°45′E and is divided into 10 districts (figure 1). In the Lideta subcity, there are a total of 281 food establishments and 1124 food handlers working in these food establishments.

Figure 1.

Map of Addis Ababa City (A) and the Lideta subcity (B). Source: Lideta Subcity Administration.

Sample size calculation and sampling techniques

The sample size was calculated using the single population proportion formula, with the following assumptions: prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers in Addis Ababa University students’ cafeteria, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (p)=45.3%,19 level of significance (α)=5%, 95% CI (standard normal probability), z=the standard normal tabulated value, and margin of error (d)=5%.

The final sample size was 419 after considering a 10% non-response rate. The Lideta subcity was selected at random from a total of 10 subcities of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Using the list of food handlers working in different food establishments in the subcity obtained from the Addis Ababa Food, Medicines and Healthcare Administration Authority as a sampling frame, we used computer-generated random number to select food handlers. Food handlers who were treated with antihelminth and antiprotozoan drugs in the last 4 weeks were excluded from the study.

Stool sample collection

Stool sample collectors first explained to the randomly selected food handlers the purpose of stool collection. The food handlers were then asked to urinate first without pooping to avoid urine contamination of the stool. Stool sample collectors then handed out a paper to food handlers and instructed them to defecate on it to avoid stool contamination with stored faeces and dirt. Food handlers were asked to place approximately 50 g of the last part of the stool, the softest part, into the collection container after defecating on the paper. Stool sample collectors did not violate the privacy of the food handlers during the stool sample collection. Stool sample collectors then immediately stored the stool sample in a cold box after labelling it with a code on the outer surface of the plastic cup.

Personal and food establishment data collection

We used a structured questionnaire and an observational checklist to collect food handlers’ personal data and food establishment-related information. The questionnaire was developed by reviewing related published articles.15 20–24 The tool was first prepared in the English language and translated to the local Amharic language by two native Amharic speakers fluent in English, and then back-translated to English by two independent English language experts fluent in Amharic to check for consistency. The questionnaire consisted of three parts: (1) food handlers’ sociodemographic characteristics, (2) food handlers’ personal hygiene conditions and (3) food establishment-related factors (online supplemental file). The questionnaire was pretested to evaluate the instructions and the response format and to ensure questions work as intended and are understood by the individuals who are likely to respond to them. Data collectors were trained in the data collection tool as well as ethical issues during interviews and observations. Supervisors supervised the data collection process and checked for completeness of data on a daily basis. We gathered handwashing data by assessing food handlers’ usual handwashing behaviours using self-reports. We also looked at the hands of the food handlers to check for the general cleanliness and conditions of the fingernails. In addition, we asked the food handlers to demonstrate how they wash their hands on a regular basis, which we evaluated using a checklist for effective handwashing.

bmjopen-2022-061688supp001.pdf (123.8KB, pdf)

Detection of ova of parasites in stool samples

We used direct stool examination (wet mount) and formalin-ether concentration (FEC) techniques to detect the ova of intestinal parasites in stool samples. One drop of physiological saline was placed on a clean slide. Using an applicator stick, a small amount of stool specimen was emulsified in saline solution. The preparation was covered with a cover slip and examined under the microscope for absence or presence of intestinal parasites. The entire saline preparation was systematically examined for helminth eggs, larvae, ciliates, cysts and oocysts using 10× objective, with the condenser iris closed sufficiently to provide good contrast, while 40× objective was used to assist in the detection of eggs, cysts and oocytes.25

For the FEC technique, an estimated 1 g of formed stool sample or 2 mL of watery stool were emulsified in about 4 mL of 10% formol water contained in a screw-cap bottle. A further 3 mL of 10% formol water were added and mixed well by shaking. The emulsified stool samples were sieved, and the sieved suspension transferred to a conical (centrifuge). Then 3 mL of diethyl ether were added and the tube was stoppered-mixed for 1 min with a tissue wrapped around the top of the tube and with the stopper loosened. It was then centrifuged for 1 minute at 3000 revolutions per minute (RPM). Using a stick, the layer of faeces debris from the side of the tube was loosen and the tube inverted to discard the ether, faecal debris and formol water, leaving behind the sediment. The tube was returned to its upright position and the fluid from the sides of the tube allowed to drain to the bottom. The bottom of the tube was taped to resuspend and mix the sediment. The sediment was transferred to a slide and covered with a cover glass and was examined microscopically using the 10× objective for focusing and the 40× objective for proper identification.

Standard operating procedures were used for every laboratory procedure during the laboratory examination, stool specimen collection, transportation and storage. We used stool sample collection and transportation containers that are leak-proof, dry-clean and free from any traces of disinfectants. We ensured correct labelling of stool sample containers using the date of sample collection and the code of the study participants. All stool specimens were stored in an ice box for transportation and were preserved at 4°C in the laboratory until analysed for the ova of parasites. Triplicate examinations of the stool samples were applied to improve the recovery rate of intestinal parasites. Moreover, the expiry date of normal saline, ether and formol was evaluated before stool sample preparation and examination.

Outcome variable of the study

The prevalence of intestinal parasites, the primary outcome variable of the study, was defined as the presence of one or more intestinal parasite species in the stool samples.

Data processing and analysis

Data were entered using Epi Info V.3.5.3 statistical package and exported into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) V.20 for further analysis. For most variables, data were presented by frequencies and percentages. Univariable binary logistic regression analysis was used to choose variables for the multivariable binary logistic regression analysis. Variables with p value less than 0.25 in the univariable analysis and other well-known confounders from the literature were then analysed by multivariable analysis to control for the possible effects of confounders and to predict the prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers based on the predictors. The adjusted analysis for the primary exposure (hand hygiene, food safety training and medical check-up) and the secondary risk factors (educational status and monthly income) focused on the direct effects. In the adjusted model, variables with significant associations were identified on the basis of adjusted OR (AOR) with 95% CI and p value <0.05. The predictive power of the model was checked using McFadden’s pseudo R-squared.

Consent to participate

There were no risks due to participation and the collected data were used only for this research purpose, with complete confidentiality and with the privacy of food handlers during stool sample collection assured. Written informed consent was obtained from the food handlers. Furthermore, we advised food handlers who had one or more ova of parasites to visit health institutions for treatment. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the study.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

We collected personal information and stool samples from a total 411 food handlers, with a response rate of 97.62%. Majority (293, 71.3%) of the study participants were female. The median age of the respondents was 28 years (IQR 20–39 years). About half (198, 48.18%) of the respondents were aged 25 years and below and half (207, 50.3%) reported that they had completed primary school education. Of the food handlers, 278 (67.6%) reported that they had 3 years or less of work experience and 111 (27.0%) earned <1500 Ethiopian birr (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of food handlers (N=411) working in different food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 20 March–20 April 2021

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Frequency | % |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 293 | 71.3 |

| Male | 118 | 28.7 |

| Age in years | ||

| ≤25 | 198 | 48.2 |

| 26–35 | 113 | 27.5 |

| 36–50 | 100 | 24.3 |

| Educational status | ||

| Tertiary education | 23 | 5.6 |

| Secondary school | 163 | 39.7 |

| Primary school | 207 | 50.3 |

| Illiterate | 18 | 4.4 |

| Service years | ||

| ≤3 | 278 | 67.6 |

| >3 | 133 | 33.4 |

| Average monthly income in Ethiopian birr | ||

| <1500 | 111 | 27.0 |

| 1501–2500 | 152 | 37.0 |

| 2501–3500 | 94 | 22.9 |

| >3500 | 54 | 13.1 |

Personal hygiene characteristics of food handlers

Of the food handlers, 242 (58.9%) did not keep their fingernails short, and 194 (47.2%) and 206 (50.1%) did not regularly wash their hands with soap after visiting a toilet and before eating, respectively. Of the food handlers, 208 (50.6%) reported that they regularly wear clean protective clothes. About a quarter (76, 24%) reported that they received food safety training and 121 (29.4%) had a medical check-up in the 6 months prior to the survey (table 2).

Table 2.

Personal hygiene characteristics of food handlers (N=411) working in different food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 20 March–20 April 2021

| Variables | Frequency | % |

| Condition of fingernails | ||

| Trimmed | 169 | 41.1 |

| Untrimmed | 242 | 58.9 |

| Regular handwashing with soap after toilet | ||

| Yes | 217 | 52.8 |

| No | 194 | 47.2 |

| Regular handwashing with soap before eating | ||

| Yes | 205 | 49.9 |

| No | 206 | 50.1 |

| Wearing clean protective clothes regularly | ||

| Yes | 208 | 50.6 |

| No | 203 | 49.4 |

| Food safety training | ||

| Yes | 76 | 24 |

| No | 335 | 76 |

| Medical check-up (in the last 6 months) | ||

| Yes | 121 | 29.4 |

| No | 290 | 70.6 |

Intestinal parasites in food handlers

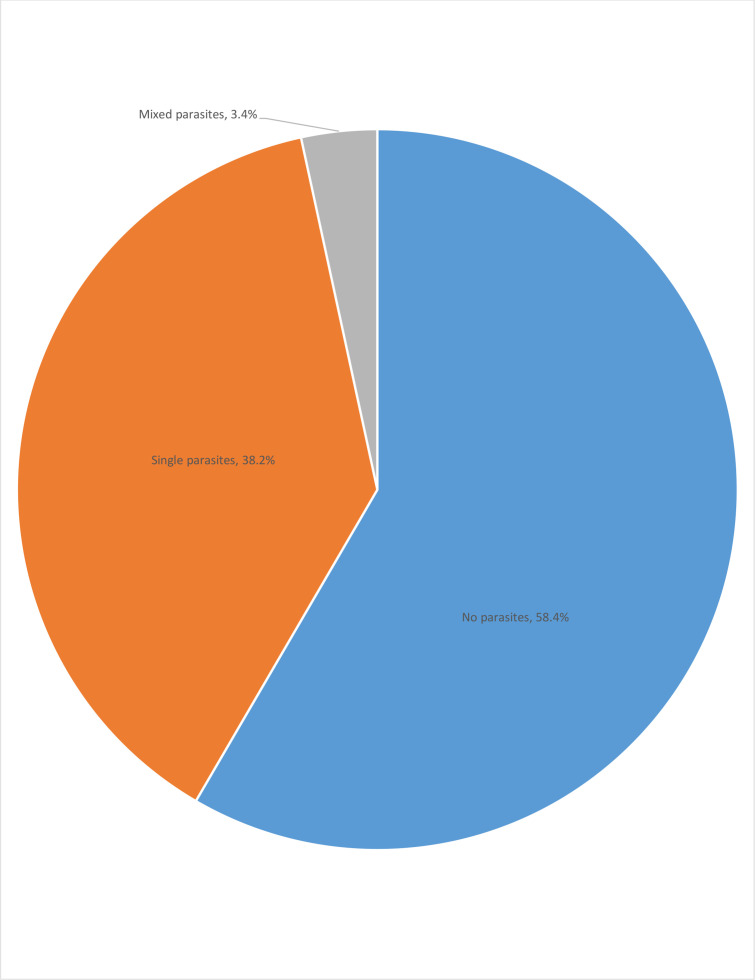

A total of 411 food handlers were examined, with 171 (41.6%) (95% CI 36.6% to 46.4%) having ova of one or more intestinal parasites (98 (23.8%) were protozoan and 73 (17.8%) were helminth parasites), of which 14 (3.4%) had mixed parasites (figure 2). The most common intestinal parasites were Entamoeba histolytica/dispar (52, 12.7%), Giardia duodenalis (46, 11.2%), Ascaris lumbricoides (34, 8.3%), hookworms (15, 3.6%), Trichuris trichiura (14, 3.4%) and Taenia species (10, 2.4%) (table 3).

Figure 2.

Proportion of food handlers with no, single and mixed parasites (N=411) working in different food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 20 March–20 April 2021.

Table 3.

Common intestinal parasites detected among food handlers (N=411) working in different food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 20 March–20 April 2021

| Parasitic species | Frequency | % |

| Entamoeba histolytica/dispar | 52 | 12.7 |

| Giardia duodenalis | 46 | 11.2 |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 34 | 8.3 |

| Hookworms | 15 | 3.6 |

| Trichuris trichiura | 14 | 3.4 |

| Taenia species | 10 | 2.4 |

Factors associated with intestinal parasites among food handlers

Sex, age, educational level, work experience, monthly income, wearing clean protective clothes, fingernail status, handwashing after toilet, handwashing before eating, food safety training and medical check-up were the variables entered in the univariable binary logistic regression analysis, of which educational status, average monthly income, condition of fingernails, handwashing with soap before eating, food safety training and medical check-up in the last 6 months were the candidate variables for the final model and were selected based on p value <0.25. Handwashing with soap after visiting the toilet is a well-known confounder in the literature and was included in the final model even if its p value was greater than 0.25. In the multivariable binary logistic regression analysis, the prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers was significantly associated with poor handwashing practice (AOR: 2.16, 95% CI 1.03 to 4.22), untrimmed fingernails (AOR: 4.36, 95% CI 1.98 to 11.90), lack of medical check-up (AOR: 2.31, 95% CI 1.18 to 6.95), no food safety training (AOR: 2.51, 95% CI 1.20 to 5.58), low level of education (AOR: 3.13, 95% CI 1.34 to 7.44) and low monthly income (AOR: 2.83, 95% CI 1.50 to 8.84) (table 4). Table 4 includes the effect estimates from the model with all the seven variables. In this case, one should know that the educational status and monthly income estimates are for direct effects.

Table 4.

Factors associated with intestinal parasites among food handlers (N=411) working in different food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 20 March–20 April 2021

| Variables | Intestinal parasites | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Yes | No | |||

| Educational status | ||||

| Illiterate | 9 | 9 | 3.60 (1.81to 10.80) | 3.13 (1.34 to 7.44)* |

| Primary school | 92 | 115 | 2.88 (1.65 to 6.17) | 2.22 (1.10 to 6.65)* |

| Secondary school | 68 | 95 | 2.58 (1.20 to 5.56) | 2.16 (1.10 to 5.20)* |

| Tertiary education | 5 | 18 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Average monthly income in Ethiopian birr | ||||

| <1500 | 56 | 55 | 2.91 (1.43 to 7.86) | 2.84 (1.50 to 8.84)* |

| 1501–2500 | 68 | 84 | 2.31 (1.14 to 6.96) | 2.28 (0.63 to 8.10) |

| 2501–3500 | 33 | 61 | 1.55 (1.05 to 4.85) | 1.41 (0.60 to 5.96) |

| >3500 | 14 | 40 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Condition of fingernails | ||||

| Untrimmed | 134 | 108 | 4.43 (2.12 to 12.62) | 4.36 (1.98 to 11.90)** |

| Trimmed | 37 | 132 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Handwashing with soap after toilet | ||||

| No | 101 | 93 | 2.28 (1.10 to 7.51) | 2.19 (0.92 to 5.62) |

| Yes | 70 | 147 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Handwashing with soap before eating | ||||

| No | 112 | 94 | 2.95 (1.23 to 6.72) | 2.16 (1.03 to 4.22)* |

| Yes | 59 | 146 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Food safety training | ||||

| No | 153 | 182 | 2.71 (1.34 to 8.53) | 2.51 (1.20 to 5.58)* |

| Yes | 18 | 58 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Medical check-up in the last 6 months | ||||

| No | 140 | 150 | 2.71 (1.27 to 7.56) | 2.32 (1.18 to 6.95)* |

| Yes | 31 | 90 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

McFadden’s pseudo R-squared=0.492.

*Statistically significant at p<0.05, **statistically significant at p<0.01.

AOR, adjusted OR; COR, crude OR.

Discussion

This is an institution-based, cross-sectional study that assessed the intestinal parasites among food handlers working in food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The study found that 41.6% (95% CI 36.6% to 46.4%) of food handlers had one or more intestinal parasites. The prevalence of intestinal parasites reported in this study was comparable with findings of studies conducted among food handlers in Bule Hora (46.3%)16 and Addis Ababa University (45.3%).19 The prevalence of intestinal parasites reported in this study was lower than the findings of studies in Nekemte Town (52.1%)26 and Mekelle University (49.4%).15 Furthermore, the prevalence of intestinal parasites reported in the current study was higher than the findings of studies conducted among food handlers in Wolaita Sodo (23.6%),14 Jimma (33%),27 Madda Walabu University (25.3%),28 Motta Town (27.6%),29 Nairobi (15.7%),30 Iran (9%),31 Saudi Arabia (23%)32 and Thailand (10%).33 The high prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers working in food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa might be explained by poor socioeconomic conditions, poor hand hygiene and inadequate access to basic sanitation services.

The high prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers working in food establishments in the Lideta subcity suggests poor hygiene practices and inadequate access to sanitation services among food handlers. The results may also suggest that there might be transmission of intestinal parasitic infections from food handlers to food users, unless large-scale screening and mass drug administrations are done. As documented in the literature, infected food handlers play a significant role in the transmission of infections to customers of the food establishments where they are working.4

This study showed that the educational status of food handlers was associated with a high prevalence of intestinal parasites. The prevalence of intestinal parasites was higher among food handlers who were illiterate or attended primary and secondary education compared with food handlers who attended tertiary education. This may be due to the fact that educated food handlers may be aware of transmission and prevention methods for infectious diseases. Education encourages changes in healthy behaviours. Other similar studies also reported the relation of education with occurrence of parasitic infections.34–38

The current study revealed that monthly income was associated with the prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers. Food handlers with low monthly income had higher odds of having intestinal parasites. This may be due to the fact that food handlers of low economic status could not afford services such as soap, household water treatment, toilets and other facilities, which would limit their opportunities to practise healthy measures. The effect of low income on risk of parasites is complex and could be attributed to limited access to sanitary materials, sources of drinking water and food, environment sanitation, and education.37–40

The high prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers was associated with hand hygiene. Food handlers who did not keep their fingernails short had higher odds of having intestinal parasites. The odds of having intestinal parasites were also higher among food handlers who did not wash their hands with soap before eating. This might be due to the fact that the area beneath the fingernails has the highest concentration of micro-organisms on the hands and is the most difficult to clean.41–44 Moreover, food handlers may ingest disease-causing pathogens when they eat without washing their hands. Hands are among the most important mechanisms that transmit pathogenic micro-organisms, leading to infections.45 Evidence indicates that hands, together with food contact or other environmental surfaces, cause 60% of spread of gastrointestinal infections. Contaminated hands could also be associated with up to 50% of respiratory tract infections.46

This study showed that the presence of intestinal parasites among food handlers was significantly associated with food safety training. The odds of having intestinal parasites were high among food handlers who did not take food safety training compared with their counterparts. This could be due to the fact that food handlers who did not take food safety training may lack the necessary knowledge and practice towards transmission and prevention of disease-causing pathogens. Moreover, food safety training or health education promotes health behaviours towards hygiene and sanitation practices. Health education increases knowledge and acceptability of interventions. It also sustains integrated control of infections.47–49

Furthermore, the presence of intestinal parasites was significantly associated with medical check-ups. The odds of having intestinal parasites were high among food handlers who did not undergo a medical check-up in the 6 months prior to the survey. Other studies have also reported that medical check-ups of food handlers are associated with the prevalence of intestinal parasites.15 31 50 This is because food handlers who did not know about their health conditions before employment and while working in different establishments have lower likelihood of taking treatment and mass drugs, and as a result they may have new or existing infections or reinfections.

To increase the degree to which inferences from the sample population can be generalised to a larger group of population, we recruited study participants at random or in a manner in which they are representative of the population that we wished to study, ensuring that every member of the population had an equal chance to be included in the study. In addition, we calculated adequately powered sample size using sample size determination procedures appropriate to the study objective, with appropriate assumptions. Furthermore, the findings could be applicable to other situations and settings with similar characteristics to the population of the current study.

Even if use of sensitive diagnostic techniques and a combination of methods with triplicate examinations would help recover a higher rate of intestinal parasites in this study that would indicate the true prevalence, this study still had some limitations. The collection of a single stool sample may affect the results of parasitic examinations since the sensitivity of the direct smear examination technique is reduced when a single stool sample is examined. The FEC technique may also damage the eggs of the parasites. The handwashing data assessed by self-reports may not be reliable since the study subjects may provide more socially acceptable answers rather than be truthful and they may not be able to assess themselves accurately. Moreover, we prescreened variables using univariable analysis (p<0.25) even though we retained some well-known confounders from the literature regardless of their univariable p values. This could lead to incorrect exclusion of a potential confounder and hence led to inadequate adjustment for confounding.

Conclusion

The prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers working in food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia was found to be high. This high prevalence of intestinal parasites was linked to food handlers’ socioeconomic conditions, poor hand hygiene conditions, absence of food safety training and no regular medical check-ups. It is, therefore, important to promote handwashing practices among food handlers, provide food hygiene and safety training, and establish a system to regularly check their health conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are pleased to acknowledge Yanet Health College, the study participants, the managers of food establishments in the Lideta subcity of Addis Ababa, the data collectors and the supervisors for their contribution to the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: WA designed the study, facilitated the data collection and conducted the data analysis. BG, TS, ZNM and ZG supervised the data collection and analysis and contributed to conceptualising the study. ZG prepared the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.WA is acting as a guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. De-identified individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article will be made available upon request to the primary author immediately following publication.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and the ethical and methodological aspects of this protocol were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Yanet Health College (reference number: YEC/060/21). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) . Estimating the burden of foodborne diseases. Available: https://www.who.int/activities/estimating-the-burden-of-foodborne-diseases [Accessed 01 Feb 2022].

- 2.Tappes SP, Chaves Folly DC, da Silva Santos G, et al. Food handlers and foodborne diseases: grounds for safety and public and occupational health actions. Rev Bras Med Trab 2019;17:431. 10.5327/Z1679443520190316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derrick J, Hollinghurst P, O'Brien S, et al. Measuring transfer of human norovirus during sandwich production: simulating the role of food, food handlers and the environment. Int J Food Microbiol 2021;348:109151. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michaels B, Keller C, Blevins M, et al. Prevention of food worker transmission of foodborne pathogens: risk assessment and evaluation of effective hygiene intervention strategies. Food Service Technology 2004;4:31–49. 10.1111/j.1471-5740.2004.00088.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedberg C. Epidemiology of viral foodborne outbreaks: Role of food handlers, irrigation water, and surfaces. In: Viruses in foods. Springer, 2016: 147–63. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dreyfuss M. Foodborne or pandemic: an analysis of the transmission of norovirus-associated gastroenteritis and the role of food handlers. Medicine 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vollaard AM, Ali S, van Asten HAGH, et al. Risk factors for transmission of foodborne illness in restaurants and street vendors in Jakarta, Indonesia. Epidemiol Infect 2004;132:863–72. 10.1017/S0950268804002742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greig JD, Todd ECD, Bartleson CA, et al. Outbreaks where food workers have been implicated in the spread of foodborne disease. Part 1. description of the problem, methods, and agents involved. J Food Prot 2007;70:1752–61. 10.4315/0362-028X-70.7.1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Todd ECD, Greig JD, Bartleson CA, et al. Outbreaks where food workers have been implicated in the spread of foodborne disease. Part 3. factors contributing to outbreaks and description of outbreak categories. J Food Prot 2007;70:2199–217. 10.4315/0362-028X-70.9.2199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathew RR, Ponnambath DK, Mandal J, et al. Enteric pathogen profile and knowledge, attitude and behavior about food hygiene among food handlers in a tertiary health care center. International Journal of Medicine and Public Health 2019;9:60–5. 10.5530/ijmedph.2019.3.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moyo D, Moyo F. Outcomes of food handlers’ medical examinations conducted at an occupational health clinic in Zimbabwe. Preprints 2020. 10.20944/preprints202008.0416.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biswal M, Khurana S, Taneja N, et al. Is routine medical examination of food handlers enough to ensure food safety in hospitals? J Commun Dis 2012;44:139–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yimam Y, Woreta A, Mohebali M. Intestinal parasites among food handlers of food service establishments in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1–12. 10.1186/s12889-020-8167-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumma WP, Meskele W, Admasie A. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated factors among food handlers in Wolaita Sodo university students Caterings, Wolaita Sodo, southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health 2019;7:140. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nigusse D, Kumie A. Food hygiene practices and prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers working in Mekelle university student’s cafeteria, Mekelle. Global Advan Res J Soc Sci 2012;1:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajare ST, Gobena RK, Chauhan NM. Prevalence of intestinal parasite infections and their associated factors among food handlers working in selected catering establishments from Bule HorA, Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int 2021;2021:6669742. 10.1155/2021/6669742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alemu AS, Baraki AG, Alemayehu M, et al. The prevalence of intestinal parasite infection and associated factors among food handlers in eating and drinking establishments in Chagni town, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2019;12:1–6. 10.1186/s13104-019-4338-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tefera T, Mebrie G. Prevalence and predictors of intestinal parasites among food handlers in Yebu town, Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS One 2014;9:e110621. 10.1371/journal.pone.0110621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aklilu A, Kahase D, Dessalegn M, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites, salmonella and shigella among apparently health food handlers of Addis Ababa University student’s cafeteria, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:1–6. 10.1186/s13104-014-0967-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marami D, Hailu K, Tolera M. Prevalence and associated factors of intestinal parasitic infections among asymptomatic food handlers working at Haramaya university cafeterias, eastern Ethiopia. Ann Occup Environ Med 2018;30:1–7. 10.1186/s40557-018-0263-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gamar TA, Musa HH, Altayb HN, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers attending public health laboratories in Khartoum state, Sudan. F1000Res 2018;7:687. 10.12688/f1000research.14681.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariam ST, Roma B, Sorsa S, et al. Assessment of sanitary and hygienic status of catering establishments of Awassa town. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 2000;14:91–8. 10.4314/ejhd.v14i1.9934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gezehegn D, Abay M, Tetemke D, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with intestinal parasites among food handlers of food and drinking establishments in Aksum town, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2017;17:1–9. 10.1186/s12889-017-4831-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jallow HS, Kebbeh A, Sagnia O. High prevalence of intestinal parasite carriage among food handlers in the Gambia. Inter J Food Science and Biotech 2017;2:1. doi:0.11648/j.ijfsb.20170201.11 [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO . Training manual on diagnosis of intestinal parasites based on the who bench AIDS for the diagnosis of intestinal parasites, district laboratory practice in tropical countries. WHO/CTD/SIP/98.2 CD-Rom, 2004. Available: http://usaf.phsource.us/PH/PDF/HELM/trainingmanual_sip98-2.pdf [Accessed 27 May 2021].

- 26.Eshetu L, Dabsu R, Tadele G. Prevalence of intestinal parasites and its risk factors among food handlers in food services in Nekemte town, West Oromia, Ethiopia. Res Rep Trop Med 2019;10:25–30. 10.2147/RRTM.S186723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Girma H, Beyene G, Mekonnen Z, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers at cafeteria of Jimma university specialized Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Asian Pac J Trop Dis 2017;7:467–71. 10.12980/apjtd.7.2017D7-20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuti KA, Nur RA, Donka GM, et al. Predictors of intestinal parasitic infection among food handlers working in Madda Walabu University, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis 2020;2020:9321348. 10.1155/2020/9321348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yesigat T, Jemal M, Birhan W. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Salmonella, Shigella, and Intestinal Parasites among Food Handlers in Motta Town, North West Ethiopia. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2020;2020:6425946:1–11. 10.1155/2020/6425946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamau P, Aloo-Obudho P, Kabiru E, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in certified food-handlers working in food establishments in the city of Nairobi, Kenya. J Biomed Res 2012;26:84–9. 10.1016/S1674-8301(12)60016-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kheirandish F, Tarahi MJ, Ezatpour B. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among food handlers in Western Iran. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2014;56:111–4. 10.1590/S0036-46652014000200004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaglool DA, Khodari YA, Othman RAM, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites and bacteria among food handlers in a tertiary care hospital. Niger Med J 2011;52:266. 10.4103/0300-1652.93802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kusolsuk T, Maipanich W, Nuamtanong S. Parasitic and enteric bacterial infections among food handlers in tourist-area restaurants and educational-institution cafeterias, Sai-Yok district, Kanchanaburi Province, Thailand. J Trop Med Parasitol 2011;34:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Mohammed HI, Amin TT, Aboulmagd E, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and its relationship with socio–demographics and hygienic habits among male primary schoolchildren in Al–Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2010;3:906–12. 10.1016/S1995-7645(10)60218-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heidari A, Rokni M. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among children in day-care centers in Damghan-Iran. Iran J Public Health 2003;32:31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quihui L, Valencia ME, Crompton DWT, et al. Role of the employment status and education of mothers in the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in Mexican rural schoolchildren. BMC Public Health 2006;6:1–8. 10.1186/1471-2458-6-225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woldu W, Bitew BD, Gizaw Z. Socioeconomic factors associated with diarrheal diseases among under-five children of the nomadic population in northeast Ethiopia. Trop Med Health 2016;44:1–8. 10.1186/s41182-016-0040-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gizaw Z, Addisu A, Gebrehiwot M. Socioeconomic predictors of intestinal parasitic infections among Under-Five children in rural Dembiya, Northwest Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Environ Health Insights 2019;13:1178630219896804. 10.1177/1178630219896804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Silva NR, Brooker S, Hotez PJ, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: updating the global picture. Trends Parasitol 2003;19:547–51. 10.1016/j.pt.2003.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahman A. Assessing income-wise household environmental conditions and disease profile in urban areas: study of an Indian City. GeoJournal 2006;65:211–27. 10.1007/s10708-005-3127-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wałaszek MZ, Kołpa M, Różańska A, et al. Nail microbial colonization following hand disinfection: a qualitative pilot study. J Hosp Infect 2018;100:207–10. 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fagernes M, Lingaas E. Factors interfering with the microflora on hands: a regression analysis of samples from 465 healthcare workers. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:297–307. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05462.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGinley KJ, Larson EL, Leyden JJ. Composition and density of microflora in the subungual space of the hand. J Clin Microbiol 1988;26:950–3. 10.1128/jcm.26.5.950-953.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hedderwick SA, McNeil SA, Lyons MJ, et al. Pathogenic organisms associated with artificial fingernails worn by healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2000;21:505–9. 10.1086/501794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pittet D, Allegranzi B, Sax H, et al. Evidence-Based model for hand transmission during patient care and the role of improved practices. Lancet Infect Dis 2006;6:641–52. 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70600-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bloomfield SF, Nath KJ. Use of ash and mud for handwashing in low income communities. The International scientific forum on home hygiene (IFH), 2009. Available: http://www.ifh-homehygiene.org/best-practice-review/use-ash-and-mud-handwashing-lowincome-communities [Accessed 02 July 2021].

- 47.Gyorkos TW, Maheu-Giroux M, Blouin B, et al. Impact of health education on soil-transmitted helminth infections in schoolchildren of the Peruvian Amazon: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7:e2397. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albright JW, Basaric-Keys J. Instruction in behavior modification can significantly alter soil-transmitted helminth (STh) re-infection following therapeutic de-worming. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2006;37:48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asaolu SO, Ofoezie IE. The role of health education and sanitation in the control of helminth infections. Acta Trop 2003;86:283–94. 10.1016/S0001-706X(03)00060-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharifi‐Sarasiabi K, Heydari‐Hengami M, Shokri A, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection in food handlers of Iran : A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Vet Med Sci 2021;7:2450–62. 10.1002/vms3.590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-061688supp001.pdf (123.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. De-identified individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article will be made available upon request to the primary author immediately following publication.