Abstract

Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494 produces the antibiotic phosphinothricin tripeptide (PTT). In the postulated biosynthetic pathway, one reaction, the isomerization of phosphinomethylmalate, resembles the aconitase reaction of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. It was speculated that this reaction is carried out by the corresponding enzyme of the primary metabolism (C. J. Thompson and H. Seto, p. 197–222, in L. C. Vining and C. Stuttard, ed., Genetics and Biochemistry of Antibiotic Production, 1995). However, in addition to the TCA cycle aconitase gene, a gene encoding an aconitase-like protein (the phosphinomethylmalate isomerase gene, pmi) was identified in the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster by Southern hybridization experiments, using oligonucleotides which were derived from conserved amino acid sequences of aconitases. The deduced protein revealed high similarity to aconitases from plants, bacteria, and fungi and to iron regulatory proteins from eucaryotes. Pmi and the S. viridochromogenes TCA cycle aconitase, AcnA, have 52% identity. By gene insertion mutagenesis, a pmi mutant (Mapra1) was generated. The mutant failed to produce PTT, indicating the inability of AcnA to carry out the secondary-metabolism reaction. A His-tagged protein (Hispmi*) was heterologously produced in Streptomyces lividans. The purified protein showed no standard aconitase activity with citrate as a substrate, and the corresponding gene was not able to complement an acnA mutant. This indicates that Pmi and AcnA are highly specific for their respective enzymatic reactions.

The structurally identical antibiotics phosphinothricin tripeptide (PTT) and bialaphos are produced by Streptomyces viridochromogenes and by Streptomyces hygroscopicus (4, 18), respectively. They consist of two molecules, l-alanine and one molecule of the unusual amino acid phosphinothricin (PT). A biosynthetic pathway for bialaphos, consisting of at least 13 steps, was postulated following analysis of nonproducing S. hygroscopicus mutants (summarized in reference 35). Several enzymes were purified, and various genes of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster were mapped in S. hygroscopicus (35), as well as in S. viridochromogenes (1, 12, 28, 32). It was shown that the respective genes and enzymes were highly similar (up to 80%) on the DNA and amino acid levels (29, 39, 40). As the genetic organizations of the two clusters are basically identical, it has been concluded that the biosynthesis in both producing strains proceeds in the same way.

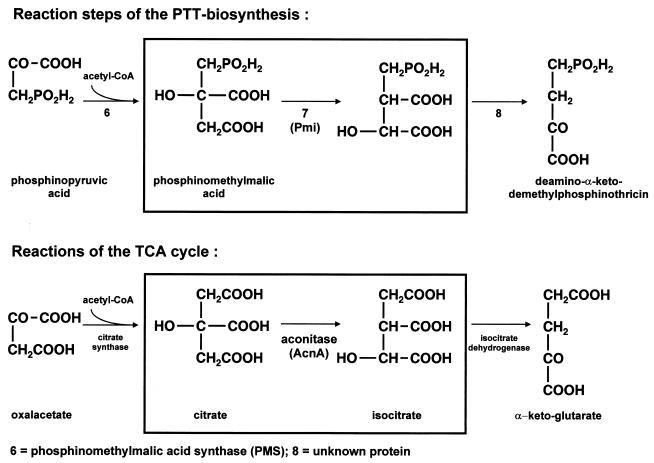

The biosynthetic steps 6, 7, and 8 were found to be similar to the citrate synthase, aconitase, and isocitrate dehydrogenase reactions of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, respectively (Fig. 1). In contrast to the step 6 reaction, for which a specific PTT biosynthetic gene and protein were identified (15), the subsequent steps, especially the isomerization of phosphinomethylmalate in step 7, were speculated to be catalyzed by the enzymes of the primary metabolism (35). Three facts supported this. First, inhibition of aconitase resulted in a PTT-negative phenotype; second, no mutants blocked in these steps could be generated by nonspecific mutagenesis; and third, biotransformations using crude cell extracts from Streptomyces lividans or Brevibacterium lactofermentum were possible (35).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of selected reactions of PTT biosynthesis and the TCA cycle. The isomerizations of citrate and of phosphinomethylmalic acid are marked by boxes.

The isolation and characterization of a PTT biosynthesis-specific aconitase-like gene in S. viridochromogenes, described in this paper, casts doubt on this hypothesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, phages, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains, phages, and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. The morphological and physiological properties of wild-type S. viridochromogenes and of the pmi mutant were examined on yeast malt medium (YM) (28). Cultivation was carried out at 30°C; liquid cultures were incubated in 100 ml of medium in an orbital shaker (180 rpm) in 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks with steel springs. The isolation of spores was done as described by Hopwood et al. (16).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and phages

| Strain, phage, or plasmid | Relevant genotype and phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. viridochromogenes | ||

| Tü494 | PTT-producing wild type | 4 |

| Mapral | Non-PTT producing; pmi::aprP Aprar | This study |

| ACOA | TCA cycle aconitase gene mutant; acnA::aphII Kanr | 30 |

| S. lividans | ||

| TK23 | spec | 16 |

| T7 | tsr; T7 RNA polymerase gene | J. Altenbuchner, personal communication |

| E. coli | ||

| BL21 (DE3)pLysS | F−ompT hsdFB (rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) pLysS (Camr) | 10, 34 |

| ET12567 | F−dam 13::Tn9 dcm-6 hsdM hsdR lacYI | 20 |

| XL1 Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔ M15Tn10 (Tetr)] | 8 |

| Phage λ-WT8 | λ phage clone carrying approximately 20 kb of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster from S. viridochromogenes | 29 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIJ486, pIJ487 | pIJ101 derivate; tsr; promoterless aphII gene; promoter probe vector | 38 |

| pDS77 | pUC18 carrying the 7.5-kb SacI fragment of λ-WT8 | This study |

| pDS80 | pIJ486 carrying a 228-bp StuI/EcoRI fragment of the upstream region of pmi | This study |

| pDS81 | pIJ487 carrying a 228-bp StuI/EcoRI fragment of the upstream region of pmi | This study |

| pDS200 | pK18 carrying a 2-kb EcoRI/SacI pmi fragment of pDS77 | This study |

| pDS201 | pK19 carrying native pmi on a 3.3-kb StuI fragment | This study |

| pEH5 | pRSETB carrying pmi as a PCR-generated BglII/HindIII DNA fragment (hispmi∗) | This study |

| pEH7 | pEH5 derivate carrying a 3.0-kb KpnI/HindIII fragment of pDS201 (hispmi) | This study |

| pEH10 | pGM9 derivate carrying pEH7 as a HindIII fragment | This study |

| pEH13 | pUC21 carrying the 1.8-kb apramycin-PermE resistance cassette | This study |

| pEH14 | pDS200 derivate; 1.8-kb EcoRV/StuI fragment of pEH13 carrying the apramycin-PermE resistance cassette (aprP) is inserted in the blunt-ended MluI site of the 2-kb EcoRI/SacI pmi fragment | This study |

| pEH15 | pK19 carrying the ermE promoter (PermE) as a 0.3-kb BamHI/KpnI fragment | This study |

| pEH16 | pEH15 derivate carrying hispmi as a 3.2-kb XbaI/HindIII fragment of pEH7 under the control of PermE | This study |

| pEH17 | pGM8 derivate carrying pEH16 as a HindIII fragment | This study |

| pEH20 | pEM4 carrying the native pmi gene as a StuI fragment | This study |

| pEM4 | Streptomyces-E. coli shuttle vector; tsr PermE | 24 |

| pGM8 | tsr aacCI; temperature-sensitive Streptomyces vector | 21 |

| pGM9 | aphII ble tsr; temperature-sensitive Streptomyces vector | 21 |

| pIJ4026 | pUC18 carrying ermE gene from Saccharopolyspora erythraea | M. J. Bibb; John Innes Institute |

Cloning, restriction mapping, and in vitro manipulation of DNA.

Methods for isolation and manipulation of DNA were as described by Sambrook et al. (26) and Hopwood et al. (16). Restriction endonucleases were purchased from various suppliers and used according to their instructions. The oligonucleotides used for identification of aconitase genes were Ac1 (5′-GGSAACCGSAACTTCGAGGGSCGS-3′) and Ac2 (5′-GTSACSACSGACCACATCTS-3′).

Gene insertion mutagenesis and transformation.

The mutant Mapra1 was generated by polyethylene glycol-mediated transformation of wild-type protoplasts with plasmid pEH14 as described by Hopwood et al. (16). The Escherichia coli and Streptomyces plasmids used in the transformation of S. viridochromogenes were isolated from the methylase-negative strain E. coli ET 12567 (20) and S. lividans TK23, respectively. Transformation of E. coli was performed using the CaCl2 method described by Sambrook et al. (26). For standard cloning experiments, E. coli XL1 Blue was used.

Southern hybridization.

Southern hybridization was carried out using the nonradioactive DIG DNA labeling and detection kit from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Hybridizations using the oligonucleotides Ac1 and Ac2 were performed at 57°C with a stringent washing step with 1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). In oligonucleotide hybridization experiments using chromosomal DNA as a template, the detection was carried out by the chemiluminescence method (Roche). Hybridization experiments with the 2-kb EcoRI/SacI pmi fragment as a probe were done at 68°C with a stringent washing step with 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS.

DNA sequencing and analysis.

pmi genes containing DNA fragments were subcloned in the sequencing vectors pK19, pUC18, and pBluescript SK(+). The DNA sequences were determined by standard techniques (27). The DNA fragments were examined for open reading frames with the codon usage program of Staden and McLachlan (5, 31). The programs BLAST (2), CLUSTAL W (36), GeneDoc (22), and TreeView (23) were used for homology searches, multiple alignments and phylogenetic trees. The accession numbers of genes used for construction of the phylogenetic tree are deposited in GenBank (J05224, X82841, Z73234, M33131, L22081, U17709, AF002133, U56817, X60293, U46154, D29629, AE000121, AE000590, Z75208, X53090, X84647, M31047, M58510, and U20180) and SwissProt (Q23500, P17279, P55251, and P55811).

Isolation of the pmi gene by PCR.

The pmi gene was isolated by PCR. The following reaction mixture was used: 0.5 μg of pDS201 (a pK19 derivative containing a StuI fragment of λ-WT8 carrying the pmi gene, which is subcloned into the HincII site of the plasmid) as a template, 1.0 μM primer 1 (5′-AAAGATCTCGCCGATTCCAAGAGGCC-3′) and primer 2 (5′-TTTAAGCTTTCACGCCGATTCCAAGAG-3′), 10 μl of 10× reaction buffer (with 2 mM MgCl2), 5% dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 0.5 μl of Pwo DNA polymerase (Roche). After denaturation (3 min at 94°C), 25 cycles of amplification (1 min at 94°C, 1.5 min at 60°C, and 2 min at 72°C) were performed in a PTC100 thermocycler from MJ Research, Inc. (Watertown, Mass.). The PCR products were electrophoretically separated in a 1% agarose gel, isolated by gel elution (Qiaquick; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and directly employed for cloning.

Heterologous expression of pmi and purification of the His-tagged protein.

YEME medium (200 ml) (16) with 25 μg of thiostrepton/ml and 10 μg of kanamycin/ml in 1,000-ml Erlenmeyer flasks (with steel springs) was inoculated with 4 ml of homogenized cells of a 2-day-old preculture of S. lividans T7(pEH10) and incubated for 24 h at 30°C and 180 rpm. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g and 4°C for 10 min and then resuspended and incubated in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mg of lysozyme/ml, 10 μg of RNaseA/ml, 5 μg of DNase I/ml) (4 ml per g [wet weight]) for 30 min on ice. The cells were broken twice, using a French press (10,000 lb/in2). The insoluble protein fraction was harvested by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 30 min. The protein was purified from the soluble crude cell extract by metal chelate affinity chromatography using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin according to the standard protocol provided by Qiagen. The collected fractions were analyzed by standard SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in 10% gels (26). The gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, and fractions containing Hispmi* were pooled.

Determination of aconitase activity.

The standard aconitase activity was assayed spectroscopically at 240 nm after the conversion of citrate to isocitrate. One unit of enzyme activity could convert 1 nmol of substrate (tri-sodium citrate dihydrate) per min, and cellular activities are expressed as units per milligram (17).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data reported have been assigned accession no. Y17269 and Y17270 in the EMBL data library.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of aconitase-like genes in the chromosome of S. viridochromogenes.

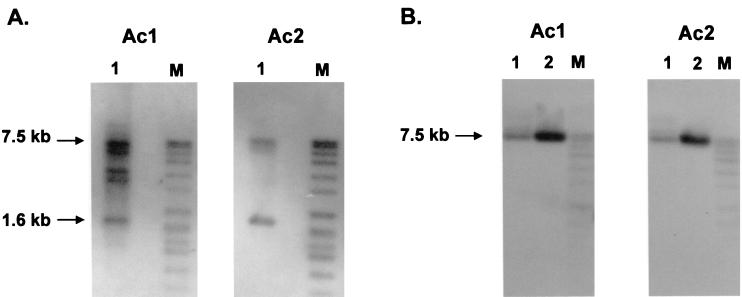

In order to examine the proposed role of the TCA cycle aconitase in PTT biosynthesis (35), we intended to isolate the S. viridochromogenes aconitase gene. The deduced amino acid sequences of aconitase genes from different organisms were aligned. Two oligonucleotides (Ac1 and Ac2) were deduced from conserved motifs (motif 1, GNRNFRGR; motif 2, VTTDHISPAG) and used in Southern hybridization experiments. By hybridization against SacI-restricted total DNA from S. viridochromogenes, two predominant signals (7.5 and 1.6 kb) were identified with both oligonucleotides, suggesting the occurrence of at least two genes for this group of enzymes (Fig. 2). In further examinations, one of the signals (a 1.6-kb SacI DNA fragment) was assigned to an internal fragment of the TCA cycle aconitase gene acnA (30).

FIG. 2.

Detection of aconitase-like genes in the genome of S. viridochromogenes. Chromosomal DNA from S. viridochromogenes and DNA from λ phage λ-WT8 were digested with the endonuclease SacI and applied in oligonucleotide hybridization experiments using the oligonucleotide probes Ac1 and Ac2 derived from conserved motifs of aconitases. (A) DNA fragments (7.5 and 1.6 kb) hybridizing with both oligonucleotides were identified in the chromosomal DNA of S. viridochromogenes. (B) Lane 1, the hybridizing 7.5-kb SacI fragment was found on phage clone λ-WT8 carrying a part of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster. Lane 2, pDS77 carrying the 7.5-kb SacI fragment of λ-WT8. M, digoxigenin-labeled DNA molecular weight marker VII (Boehringer).

Isolation of an aconitase-like gene in the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster.

To check whether the second signal corresponded to a PTT biosynthetic gene, hybridization experiments with the two aconitase-related oligonucleotides were carried out. As a template, DNA of a λ phage clone (λ-WT8) carrying approximately 20 kb of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster (29) was used. A 7.5-kb SacI fragment hybridizing with Ac1 and Ac2 was identified and shown to present the second signal (Fig. 2A). In further subcloning experiments, it was subsequently restricted to a 2-kb EcoRI/SacI DNA fragment.

Sequence analysis of pmi

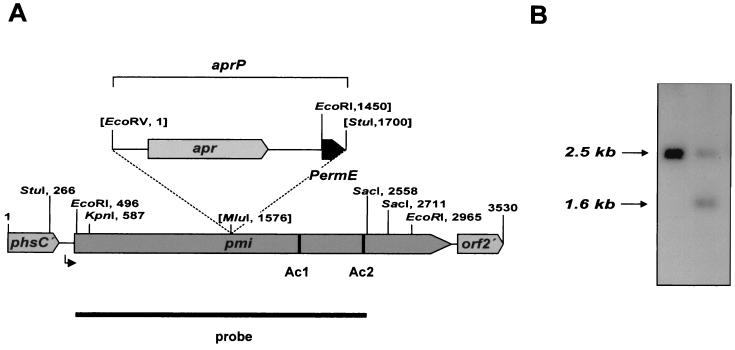

The 2-kb EcoRI/SacI subfragment was cloned into pK18, resulting in pDS200. Its DNA sequence was determined, together with those of adjacent fragments. One complete gene and two incomplete open reading frames were identified on a 3.5-kb DNA fragment. The complete pmi gene has a size of 2,667 bp and encodes a protein of 889 amino acids. A putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence (5′-GAGGAG-3′) is located 6 bp in front of the GTG start codon. The gene is flanked upstream by the 3′ region of the PTT synthetase C gene (phsC), whose gene product is involved in the nonribosomal synthesis of the tripeptide PTT (biosynthetic step 11) (D. Schwartz, unpublished data), and downstream by a gene of unknown function called orf2 (Fig. 3). pmi and the previously described TCA cycle aconitase gene acnA (30) show an identity of approximately 68% at the DNA level. Whereas the G+C content in the coding region is approximately 72%, typical for Streptomyces, the G+C content in the intergenic region between phsC and pmi was determined to be 62 mol%. No significant similarities to Streptomyces or E. coli promoters (6, 14, 33) were found.

FIG. 3.

Genetic localization and gene insertion mutagenesis of the pmi gene. (A) Arrangement of genes on a 3.5-kb DNA fragment carrying a part of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster. pmi, gene encoding Pmi; phsC′, 3′ terminus of the PTT synthetase gene C (phsC); orf2′, 5′ region of the orf2 gene from S. viridochromogenes. Restriction sites used in subcloning experiments are marked, and the region with promoter activity is indicated by an arrow. The apramycin-PermE resistance cassette (aprP) and the insertion site used in gene inactivation of pmi are marked. Restriction sites which are destroyed by insertion of the cassette are indicated by brackets. The DNA regions which correspond to the oligonucleotides Ac1 and Ac2 and the EcoRI/SacI DNA fragment used as a probe are marked. (B) The correct gene replacement in mutant Mapra1 is shown by Southern hybridization experiments using the 2-kb SacI/EcoRI pmi fragment as a probe. Lane 1, EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNA of S. viridochromogenes wild type; lane 2, EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNA of Mapra1.

Identification of a promoter in the intergenic region of pmi and phsC.

A 228-bp StuI/EcoRI fragment was subcloned into the promoter probe vectors pIJ486 and pIJ487. S. lividans was transformed with these plasmids. Using spores of plasmid-carrying strains, the kanamycin resistance was determined after 2 days of incubation. Cloning of the fragment in the direction of pmi transcription in front of aphII in pIJ486 (pDS80) enabled S. lividans to grow on Luria-Bertani medium containing up to 800 μg of kanamycin ml−1. When the fragment was cloned in the opposite direction (pDS81), no significant resistance (approximately 10 μg ml−1) was obtained. pmi and the TCA cycle aconitase gene acnA seem to be differently regulated, since the identified promoter region of pmi showed no similarity to the corresponding region of acnA. In analogy to the bialaphos gene cluster in S. hygroscopicus (35), the transcription of the pmi promoter is probably affected by the PTT pathway-specific activator PrpA, whose gene is located at the right boundary of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster (D. Schwartz, unpublished).

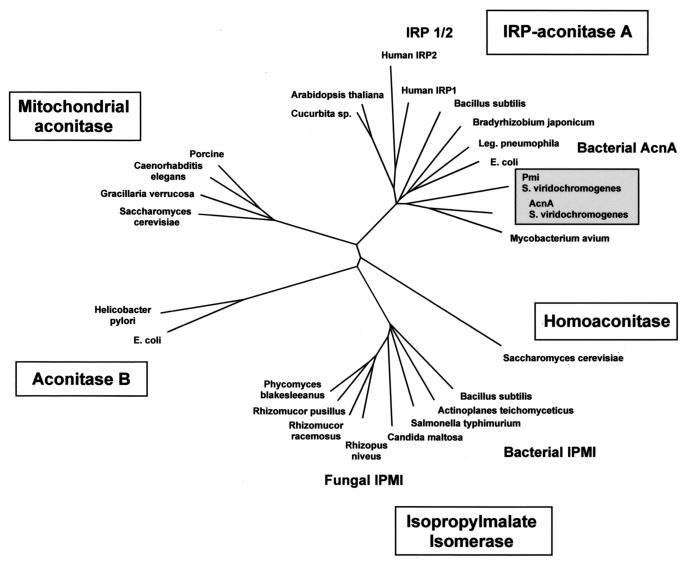

Analysis of the deduced Pmi protein.

The deduced Pmi protein, with 889 amino acids, significantly resembled aconitases from plants, bacteria, and fungi and iron regulatory proteins (IRP) from eucaryotes. Structurally conserved amino acids and cysteine residues involved in the formation of the [4Fe-4S] cluster typical for this class of enzymes (11) were identified. The greatest similarity was found to the TCA cycle aconitases of Streptomyces coelicolor (GenBank accession no. AF180948) and Mycobacterium avium (GenBank accession no. AF002133) (with identities of 54 and 50%, respectively). Pmi and the previously described S. viridochromogenes TCA cycle aconitase AcnA (30) showed an overall identity of approximately 52%. Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences of these two proteins to those of other members of the aconitase family, such as aconitases, isopropylmalate isomerases, and homoaconitases, showed that both AcnA and Pmi belong to the AcnA-IRP group (Fig. 4). In addition, their domain structures showed the characteristics of A-type aconitases. Three structurally conserved domains are linked to domain 4 at the carboxy-terminal ends of the proteins (13). This implies that the specific Pmi and AcnA proteins from S. viridochromogenes were generated by duplication of an ancestral aconitase gene. In Streptomyces, the duplication of structural genes is not a special feature. The occurrence of secondary-metabolism genes which have a similar counterpart in the primary metabolism has also been described for other genes, such as those for the acyl carrier protein in actinorhodin and fatty acid biosynthesis in S. coelicolor (25) or the p-aminobenzoate synthase gene in folic acid synthesis and chloramphenicol biosynthesis in Streptomyces venezuelae (7).

FIG. 4.

Dendrogram showing phylogenetic relationships between Pmi and AcnA from S. viridochromogenes and other members of the aconitase family. The dendrogram was generated by the program TreeView (23) using a multiple alignment of aconitases, isopropylmalate isomerases (IPMI), homoaconitases, and IRP deposited in GenBank and SwissProt (according to reference 13).

Gene insertion mutagenesis of the pmi gene.

In order to confirm the involvement of pmi in PTT biosynthesis, the gene was inactivated by gene insertion (Fig. 3A). To avoid polar effects, the apramycin-PermE resistance cassette (aprP) was inserted in the direction of transcription of pmi. The gene insertion mutagenesis was performed using plasmid pEH14 (Table 1). Apramycin-resistant, kanamycin-sensitive transformants were analyzed in Southern hybridization experiments, and clones were identified showing a double-crossover event between the chromosomal copy of pmi and the mutated fragment located on pEH14 (Fig. 3B). In comparison to the wild type, the mutant Mapra1 lost the ability to produce PTT, but it showed normal growth behavior and was able to form aerial mycelium and to sporulate. By genetic complementation using plasmid pEH20, which carries the native pmi gene, the ability of the mutant to produce PTT was restored (detected by a biological assay [1]), indicating that the insertion of the resistance cassette did not prevent the transcription of the PTT biosynthetic genes located downstream. Under the conditions of PTT production (after approximately 70 h of incubation), the crude cell extract of Mapra1 showed a specific aconitase activity (0.048 ± 0.0037 U/mg of protein) nearly identical to that of the wild-type extract (0.043 ± 0.0013 U/mg of protein). Therefore, the inability of the mutant to produce PTT revealed that AcnA cannot substitute for the function of Pmi, despite the high similarity of the two proteins.

Heterologous expression of pmi and protein purification

In order to characterize the Pmi protein, we intended to heterologously express the pmi gene in E. coli using the expression plasmid pRSETB (Fa. Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands). A DNA fragment containing the pmi gene was generated by PCR with BglII and HindIII restriction sites at its 3′- and 5′-terminal ends, respectively. The gene was cloned into the BglII/HindIII-digested vector, resulting in plasmid pEH5 (Table 1). By this cloning strategy, pmi transcription is under the control of the strong T7 promoter, and a His-tagged coding sequence is fused to the 3′-terminal end of the gene (hispmi). To exclude PCR-generated sequence faults, the sequence of the 5′-terminal end was verified by DNA sequence analysis. Furthermore, a 2.6-kb KpnI/HindIII fragment of pEH5 (with a KpnI site at bp 105 of the pmi gene) was exchanged for a 3-kb KpnI/HindIII fragment of pDS201 carrying the native part of pmi, resulting in pEH7 (hispmi*). E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS was transformed with pEH7, and the induced cells were examined for hispmi* expression. SDS-PAGE analysis of the crude cell extract showed no overexpression of pmi. The same results were achieved after protein purification by affinity chromatography under native or denaturating conditions and in Western blotting experiments with anti-His-tag antibodies.

In addition to pRSETB, other expression plasmids (pQE30 [Qiagen] and pJOE2775 or pJOE2702 [37]) were used, which are characterized by other promoters (T5 or rhaP promoter) or by fusion of the His tag at either the 3′- or 5′-terminal end of the gene. In all these experiments, an expression of pmi was not detectable. Only by expression as a gst (glutathione S-transferase gene)-pmi fusion could a very small amount of hybrid protein be obtained (data not shown). Similar problems were also reported for the expression of other Streptomyces genes, e.g., the chloroperoxidase gene from S. lividans (3) or the peptide synthetase gene phsA from S. viridochromogenes (28), which failed or resulted in inactive proteins in E. coli. It was speculated (28) that the lack of accessory proteins may play a role in this. Since Pmi (like other proteins of the aconitase family) is likely to possess a [4Fe-4S] cluster in its catalytic site, specific accessory proteins may be required for the formation of this cluster. This has been described for the synthesis of [4Fe-4S] proteins in the nitrogen-fixing bacterium Azotobacter vinelandii and in other procaryotes (9, 19, 41).

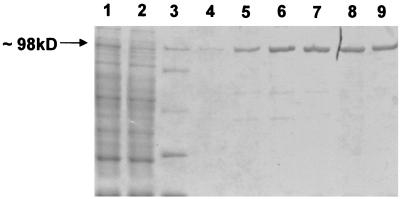

Because E. coli was unsuitable for pmi expression, we proceeded to express the gene in S. lividans T7 (Table 1). This strain possesses a thiostrepton-inducible T7 RNA polymerase gene (J. Altenbuchner, personal communication). The E. coli pmi expression plasmid pEH7, which carries hispmi* under the control of the T7 promoter, was cloned as a HindIII fragment into the vector pGM9, resulting in the Streptomyces-E. coli shuttle plasmid pEH10 (Table 1). S. lividans T7 was transformed with this plasmid, and after induction with thiostrepton, an overexpression of hispmi* was detected in the crude cell extract in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5). The soluble protein was purified by metal chelate affinity chromatography using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin under native conditions (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Heterologous expression of hispmi* in S. lividans T7 and purification of the protein by metal chelate chromatography. Protein-containing fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Lane 1, crude cell extract; lane 2, flowthrough of unbound protein; lane 3, size marker; lanes 4 to 9, elution of the protein. The size of the overexpressed His-tagged protein is marked by an arrow.

Test of standard aconitase activity.

In order to test whether Pmi is able to catalyze the aconitase reaction of the TCA cycle, the aconitase assay described by Kennedy et al. (17) was performed. No aconitase activity could be measured with either 50 or 500 mM trisodium citrate. The absence of aconitase activity seems not to be a result of the protein purification, as it was possible to purify the TCA cycle aconitase protein from S. viridochromogenes in an active form, using the same method (Schwartz, unpublished). In order to exclude the possibility that the chelating His tag has a negative effect on the [4Fe-4S] cluster of Pmi, the mutant Mapra1 was complemented with hispmi*. hispmi* was cloned as a 3.2-kb XbaI/HindIII fragment into the vector pEH15 downstream of the ermE promoter. The resulting plasmid, pEH16, was inserted as a HindIII fragment into the vector pGM8 (Table 1), and the mutant Mapra1 was transformed with the resulting plasmid, pEH17. By a biological test described by Alijah et al. (1), it was shown that the complemented mutant produced the antibiotic PTT at the same level as the wild type, indicating that the His-tagged protein possesses sufficient activity to support this phenotype under the conditions used.

Genetic complementation of the TCA cycle aconitase mutant ACOA with hispmi*

In order to verify that the Pmi protein is not able to catalyze the TCA cycle reaction, the TCA cycle gene (acnA) mutant ACOA was complemented using plasmid pEH17. ACOA is characterized by a growth delay and by the inability to develop aerial mycelium and to sporulate (bald phenotype) (30). Furthermore, ACOA has a defect in physiological differentiation shown by the loss of production of the secondary metabolite PTT, probably due to the absence of transcription of the PTT biosynthetic genes, including pmi. Introducing the plasmid pEH17 had no effect on the phenotype of ACOA, indicating that Pmi cannot carry out the isomerization of citrate and thus is specialized in the postulated secondary-metabolism reaction.

In the complete PTT biosynthetic gene cluster (Schwartz, unpublished), pmi is the only aconitase-like gene. Biochemical studies of PTT biosynthesis demonstrated that only the biosynthetic step 7 (Fig. 1) shares chemical and structural characteristics with the aconitase reaction of the TCA cycle (35). Therefore, Pmi probably catalyzes the isomerization of phosphinomethyl malic acid in this step. As the secondary metabolite phosphinomethylmalic acid is unfortunately not commercially available, its purification will be the essential step to demonstrate the postulated Pmi activity in further experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the DFG (Graduiertenkolleg Mikrobiologie) and by the BMBF (ZSP Bioverfahrenstechnik, D 3.2 E). G. Kienzlen and E. Heinzelmann were supported by grants from the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung and the Landesgraduiertenkolleg Baden-Württemberg, respectively.

We are very grateful to J. Altenbuchner for providing the S. lividans T7 strain. The antibiotic thiostrepton was kindly provided by S. J. Lucania, Squibb, New York, N.Y.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alijah R, Dorendorf J, Talay S, Pühler A, Wohlleben W. Genetic analysis of the phosphinothricin-tripeptide biosynthetic pathway of Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü 494. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;34:749–755. doi: 10.1007/BF00169345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bantleon R, Altenbuchner J, van Pée K H. Chloroperoxidase from Streptomyces lividans: isolation and characterization of the enzyme and the corresponding gene. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2339–2347. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2339-2347.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayer E, Gugel K H, Hägele K, Hagenmaier H, Jassipow S, König W A, Zähner H. Stoffwechselprodukte von Mikroorganismen. Phosphinothricin und Phosphinothricyl-Alanyl-Alanin. Helv Chim Acta. 1972;55:224–239. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19720550126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bibb M J, Findlay P R, Johnson M W. The relationship between base composition and codon usage in bacterial genes and its use for the simple and reliable identification of protein-coding sequences. Gene. 1984;30:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourn W R, Babb B. Computer associated identification and classification of streptomycete promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3696–3703. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.18.3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown M P, Aidoo K A, Vining L C. A role for pabAB, a p-aminobenzoate synthase gene of Streptomyces venezuelae ISP5230, in chloramphenicol biosynthesis. Microbiology. 1996;142:1345–1355. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-6-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullock W O, Fernandez J M, Short J M. Xl1-Blue, a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta galactosidase selection. Focus. 1987;5:376–378. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig E A, Voisine C, Schilke B. Mitochondrial iron metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biol Chem. 1999;380:1167–1173. doi: 10.1515/BC.1999.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davanloo P, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Studier F W. Cloning and expression of the gene for bacteriophage T7 polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2035–2039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frishman D, Hentze M. Conservation of aconitase residues revealed by multiple sequence analysis. Implications for structure/function relationships. Eur J Biochem. 1996;239:197–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0197u.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grammel N, Schwartz D, Wohlleben W, Keller U. Phosphinothricin-tripeptide synthetases from Streptomyces viridochromogenes. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1596–1603. doi: 10.1021/bi9719410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gruer M J, Artymiuk P J, Guest J R. The aconitase family: three structural variations on a common theme. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:3–6. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harley C B, Reynolds R P. Analysis of Escherichia coli promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2343–2361. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.5.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hidaka T, Shimotohno K W, Morishita T, Seto H. Studies on the biosynthesis of bialaphos (SF-1293). 18. 2-phosphinomethylmalic acid synthase: a descendant of (R)-citrate synthase? J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1999;52:925–931. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.52.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. Norwich, United Kingdom: John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy M C, Emtage M H, Dreyer J-L, Bienert H. The role of iron in the activation-inactivation of aconitase. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:11098–11105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondo Y, Shomura T, Ogawa Y, Tsuruoka T, Watanabe H, Totsukawa K, Suzuki T, Moriyama C, Yoshida J, Inouye S, Niida T. Studies on a new antibiotic SF-1293. I. Isolation and physico-chemical and biological characterization of SF-1293 substances. Sci Rep Meiji Seika. 1973;13:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lill R, Diekert K, Kaut A, Lange H, Pelzer W, Prohl C, Kispal G. The essential role of mitochondria in the biogenesis of cellular iron-sulfur proteins. Biol Chem. 1999;380:1157–1166. doi: 10.1515/BC.1999.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacNeil D J, Gewain K M, Ruby C L, Dezeny G, Gibbons P H, MacNeil T. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene. 1992;111:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90603-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muth G, Nußbaumer B, Wohlleben W, Pühler A. A vector system with temperature-sensitive replication for gene disruption and mutational cloning in streptomycetes. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;219:341–348. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholas K B, Nicholas H B, Jr, Deerfield D W., II GeneDoc: analysis and visualization of genetic variation. EMBNETNEWS. 1997;4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Page R D H. TREEVIEW: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quiros L M, Aguirrezabalaga I, Olano C, Mendez C, Salas J A. Two glycosyltransferases and a glycosidase are involved in oleandomycin modification during its biosynthesis by Streptomyces antibioticus. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1177–1185. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Revill W P, Bibb M J, Hopwood D A. Relationship between fatty acid and polyketide synthases from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): characterization of the fatty acid synthase acyl carrier protein. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5660–5667. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5660-5667.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch T, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz D, Alijah R, Nußbaumer B, Pelzer S, Wohlleben W. The peptide synthetase gene phsA from Streptomyces viridochromogenes is not juxtaposed with other genes involved in nonribosomal biosynthesis of peptides. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:570–577. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.570-577.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz D, Recktenwald J, Pelzer S, Wohlleben W. Isolation and characterization of the PEP-phosphomutase and the phosphonopyruvate decarboxylase genes from the phosphinothricin tripeptide producer Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü 494. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;163:149–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz D, Kaspar S, Kienzlen G, Muschko K, Wohlleben W. Inactivation of the TCA cycle aconitase gene from Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494 impairs the morphological and physiological differentiation. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7131–7135. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.22.7131-7135.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staden R, McLachlan A D. Codon preference and its use in identifying protein coding regions in large DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:141–156. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strauch E, Wohlleben W, Pühler A. Cloning of a phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferase gene from Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494 and its expression in Streptomyces lividans and Escherichia coli. Gene. 1988;63:65–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strohl W R. Compilation and analysis of DNA sequences associated with apparent Streptomyces promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:961–974. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.5.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Studier F W, Moftt B A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Evol. 1986;189:113. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson C J, Seto H. Bialaphos. In: Vining L C, Stuttard C, editors. Genetics and biochemistry of antibiotic production. Oxford, United Kingdom: Butterworth Heinemann Bio/Technology; 1995. pp. 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. ClustalW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volff J N, Eichenseer C, Viell P, Piendl W, Altenbuchner J. Nucleotide sequence and role in DNA amplification of the direct repeats composing the amplifiable element AUD1 of Streptomyces lividans 66. Mol Microbiol. 1996;5:1037–1047. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.761428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward J M, Janssen G R, Kieser T, Bibb M J, Buttner M J. Construction and characterization of a series of multi-copy promoter-probe plasmid vectors for Streptomyces using the aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene from Tn5 as indicator. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;203:468–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00422072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wohlleben W, Alijah R, Dorendorf J, Hillemann D, Nußbaumer B, Pelzer S. Identification and characterization of phosphinothricin-tripeptide biosynthetic genes in Streptomyces viridochromogenes. Gene. 1992;115:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wohlleben W, Arnold W, Broer I, Hillemann D, Strauch E, Pühler A. Nucleotide sequence of the phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferase gene from Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494 and its expression in Nicotiana tabacum. Gene. 1988;70:25–37. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng L, Cash V L, Flint D H, Dean D R. Assembly of iron-sulfur clusters. Identification of an iscSUA-hscBA-fdx gene cluster from Azotobacter vinelandii. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13264–13272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]