Abstract

Background and Aim:

In the era of minimally invasive procedures and as a way to decrease the incidence of post-operative pancreatic fistula (POPF), the use of staplers for distal pancreatectomy (DP) has increased dramatically. Our aim was to investigate whether reinforced staplers decrease the incidence of clinically relevant PF after DP compared with staplers without reinforcement.

Methods:

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Cochrane Library were searched for eligible studies from inception to 1 November 2021, and a systematic review and a meta-analysis were done to detect the outcomes after using reinforced staplers versus standard stapler for DP.

Results:

Seven studies with a total of 681 patients were included. The overall incidence of POPF and the incidence of Grade A POPF after DP are similar for the two groups (overall POPF, risk ratio [RR] = 0.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.71–1.01, P = 0.06; I2 = 38% and Grade A POPF, RR = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.78–1.69, P = 0.47; I2 = 49%). However, the incidence of clinically significant POPF (Grades B and C) is significantly lower in DP with reinforced staplers than DP with bare staplers (Grades B and C, RR = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.29–0.71, P = 0.0005; I2 = 17%). Nevertheless, the time of the operation, the blood loss during surgical procedure, the hospital stay after the surgery and the thickness of the pancreas are similar for both techniques.

Conclusion:

Although staple line reinforcement after DP failed to prevent biochemical PF, it significantly reduced the rate of clinically relevant POPF in comparison to standard stapling.

Keywords: Distal pancreatectomy, pancreatic fistula, reinforcement, stapler

INTRODUCTION

Distal pancreatectomy (DP) is performed mainly for malignant, pre-malignant or sometimes benign lesions affecting the body and/or tail of the pancreas. This surgery involves resection of the pancreatic portion that lies to the left of the superior mesenteric vein. While DP (with or without splenectomy) is considered a minor procedure compared with pancreatic head resection (pancreatoduodenectomy), the morbidity rate associated with this procedure remains high. Pancreatic fistula (PF) and leakage are the foremost common and clinically relevant complications, approximately 30% of patients develop post-operative pancreatic fistula (POPF) and their occurrence is thought to rely on the surgical technique and skills.[1]

Fistula is associated with local and general complications (pancreatic fluid collection, formation of intra-abdominal abscesses, surgical site infection, sepsis, delayed gastric emptying and respiratory complications) that consequently affect the patient, the surgeon and the healthcare system. In general, it prolongs hospital stay for specialised treatment, including revision surgery and drainage.[2]

Numerous techniques have been adapted to decrease the incidence of POPF, such as using somatostatin analogues,[3] prophylactic stenting of the pancreatic duct,[4] stump coverage with tissue patch,[5] pancreatojejunostomy[6] and pancreatogastrostomy[7] almost without significant improvement in outcome. However, according to a network meta-analysis comparing three techniques and outcomes of stump closure after DP, the use of stapler closure or anastomotic closure for the pancreatic remnant after DP significantly reduces POPF rates compared with suture closure.[8]

Recently, a reinforced stapler with bioabsorbable materials was produced to supply additional support for the resection line of the pancreas by overlaying the staple line with reinforcement. Many studies illustrated that reinforced staplers dramatically reduce the rate of PF compared with stapler closure without reinforcement.[9,10,11] Nevertheless, other studies showed that the use of reinforced staplers with bioabsorbable materials did not cause a dramatic reduction of clinically relevant PF after DP.[12,13,14] Moreover, more studies demonstrated that the use of reinforced staplers with bioabsorbable materials actually increased the incidence of clinically relevant PF after DP.[15] Meanwhile, according to a meta-analysis studying the efficacy of reinforced staplers used for DP, no significant difference regarding clinically relevant PF could be detected between stapler closure with and without reinforcement.[16] Thus, it can be said that the safety and efficacy of reinforced staplers with bioabsorbable materials for DP is still controversial.

METHODS

Search strategy

PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science and Cochrane Library were searched for data from inception to 1 November 2021 with the following terms: DP and staplers. More searches by Google Scholar have been used to supplement the search with the sites mentioned above. All studies were reviewed and evaluated by two authors (Elkomos B. E. and Elkomos P. E.) according to the eligibility process. Abstract-based eligibility studies were obtained, and the manuscripts were fully reviewed. Report bibliographies that meet the eligibility criteria were reviewed for further studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The eligible studies included the following: (1) randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective or retrospective cohort studies; (2) target population were patients who underwent DP using staplers; (3) studies designating a comparison of reinforcement of stapler line versus bare staplers as a primary aim; (4) studies providing a sufficient description of the methods and baseline characteristics and (5) the main outcome was the incidence of PF for both reinforced and standard staplers. The following types of studies were not included in our study: (1) unrelated or in vitro studies; (2) reviews, case reports and case series and (3) studies missing a comparison group.

Outcomes of interest

We assessed five primary outcomes for reinforced and standard staplers for DP in this meta-analysis, including the incidence of POPF (Grades A, B and C), the time of the operation, the blood loss during the operation, the hospital stay after operation and the thickness of the pancreas. POPFs were classified according to the 2016 update of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS).[17]

Data extraction

We extracted data on study characteristics (author, year of publication, country of operation and number of institutes included in the study), patient characteristics (age, sex and body mass index [BMI]), operative details (laparoscopic or open technique, the time of the operation, the blood loss during the operation and the thickness of the pancreas) and outcomes (hospital stay, the time of the operation, the blood loss during operation and the overall incidence of POPF). The data were extracted by two investigators (Elkomos B. E. and Elkomos P. E.) independently.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was performed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,[18] which is recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. For all the results included, the pooled risk ratios (RRs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with fixed effects models. However, if there was moderate or considerable heterogeneity (I2>40), random effects models were used to solve the heterogeneity between studies. All calculations for the current meta-analysis were performed with Review Manager 5.4 for Windows (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom).

Assessment of publication bias and heterogeneity

Funnel plots were generated so that we could visually inspect for publication bias. The statistical methods for detecting funnel plot asymmetry were the Begg–Mazumdar rank correlation test and the Egger regression asymmetry test. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed with forest plots and the inconsistency statistic (I2). An I2 value of 40% or less corresponded to low heterogeneity. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

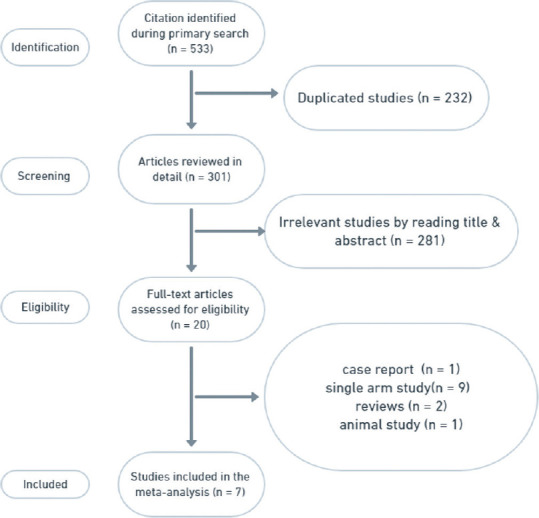

Characteristics of eligible studies

As shown in the flow diagram [Figure 1], 533 articles were revealed using the following search string: surgical staplers and DP. After careful selection according to our eligibility criteria, 7 studies with 681 participants were included in the meta-analysis. These trials included four RCTs and three retrospective cohort studies. Three were multicentre studies, whereas the others were single-centre studies. While fix studies used polyglycolic acid (PGA) mesh-reinforced staplers and one study reinforced the stapler line with PGA mesh after using bare staplers, only one study used Biodesign® staple line reinforcement (SLR).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Patients’ baseline data included number, age, sex and BMI. In addition to that, the approach of the surgery (laparoscopic or open) and the pathology of the pancreases were comparable between the two groups in all studies [Table 1].

Table 1.

Basic data of the studies

| Studies: Author, year, country | Study design | Study period | Number of centres | Arm | Sample size (n) | Age (year) | Gender: Male/female (n) | BMI (kg/m2) | Laparoscopic operation (yes/no) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johnston et al. (2009), USA[19] | Retrospective cohort | 2002-2007 | 1 | Reinforced | 70 | 49 (29-82)** | 38/32 | N/A | 24/46 |

| Bare | 44 | 55 (23-82)** | 25/19 | N/A | 4/40 | ||||

| Hamilton et al. (2012), USA[10] | RCT | 2007-2010 | 1 | Reinforced | 54 | 57.5±15.6* | 20/34 | 27.91±5.78* | 25/29 |

| Bare | 46 | 58.6±13.4* | 25/21 | 30.97±7.28* | 22/24 | ||||

| Hayashibe and Ogino (2018), Japan[20] | Retrospective cohort | 2004-2015 | 1 | Reinforced | 29 | 72.6±10.3* | 9/20 | N/A | N/A |

| Bare | 22 | 63.0±17.8* | 9/13 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Jang et al. (2017), Korea[9] | RCT | 2011-2014 | 5 | Reinforced | 44 | 59.9 (12.0)* | 19/25 | N/A | N/A |

| Bare | 53 | 54.5 (14.1)* | 20/33 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Kondo et al. (2019), Japan[21] | RCT | 2016-2017 | 5 | Reinforced | 61 | 70 (62-76)** | 31/30 | 22.1 (19.9-25.0)** | 14/47 |

| Bare | 59 | 73 (67-78)** | 25/24 | 20.8 (19.6-23.9)** | 14/45 | ||||

| Kawaida et al. (2019), Japan[22] | Prospective cohort | 2013-2018 | 1 | Reinforced | 56 | 62.9±2.0* | 18/38 | 22.1±0.5* | 24/32 |

| Bare | 37 | 66.1±2.5* | 19/18 | 22.0±0.7* | 9/28 | ||||

| Wennerblom et al. (2021), Sweden[23] | RCT | 2014-2016 | 4 | Reinforced | 56 | 67 (35-84)** | 27/29 | 26.7 (18.7-47.3)** | 13/43 |

| Bare | 50 | 68 (28-89)** | 27/23 | 26.8 (18.9-37.6)** | 9/41 |

*The results are presented as means and SD, **The results are presented as median and range. SD: Standard deviation, RCT: Randomised controlled trial, NA: Not available, BMI: Body mass index

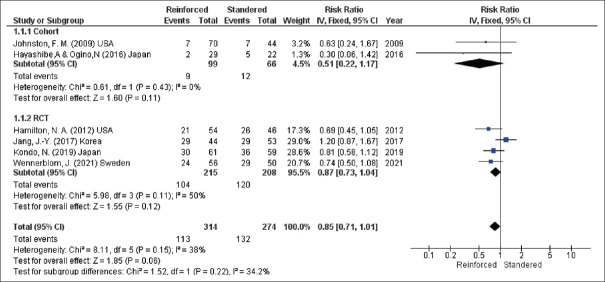

Overall post-operative pancreatic fistula

The seven studies assessed overall POPF after DP. However, the pooled result showed no significant difference in the incidence of POPF for the two techniques (overall POPF, RR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.71–1.01, P = 0.06; I2 = 38%) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Overall incidence of POPF. POPF: Post-operative pancreatic fistula, CIs: Confidence intervals, RRs: Risk ratios, RCTs: Randomised controlled trials, df: Degree of freedom, IV: Inverse variance

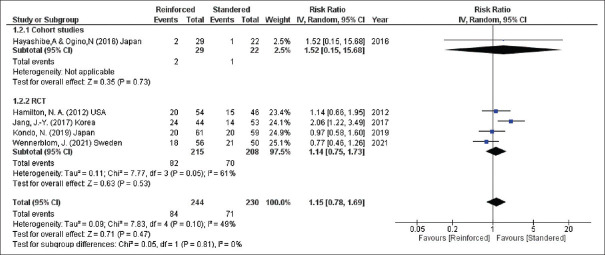

Biochemical post-operative pancreatic fistula

Grade A POPF was calculated for the two groups in five studies (474 participants) and the incidence of this biochemical POPF was similar for the techniques (Grade A POPF, RR = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.78–1.69, P = 0.47; I2 = 49%) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Incidence of biochemical POPF. POPF: Post-operative pancreatic fistula, CIs: Confidence intervals, RRs: Risk ratios, RCTs: Randomised controlled trials, df: Degree of freedom, IV: Inverse variance

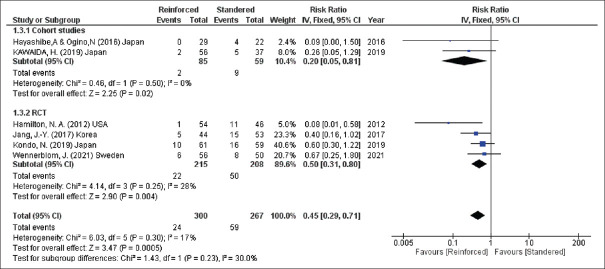

Clinically significant post-operative pancreatic fistula

Regarding Grade B and C POPF that was reported in six studies (567 participants), a significant decrease in the incidence of POPF could be detected after reinforcement of the stapler line (Grades B and C, RR = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.29–0.71, P = 0.0005; I2 = 17%) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Incidence of clinically significant POPF. POPF: Post-operative pancreatic fistula, CIs: Confidence intervals, RRs: Risk ratios, RCTs: Randomised controlled trials, df: Degree of freedom, IV: Inverse variance

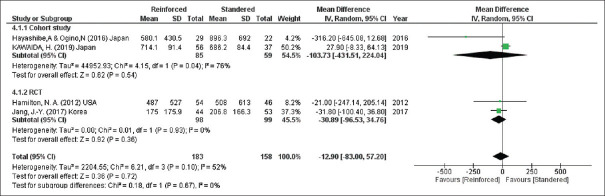

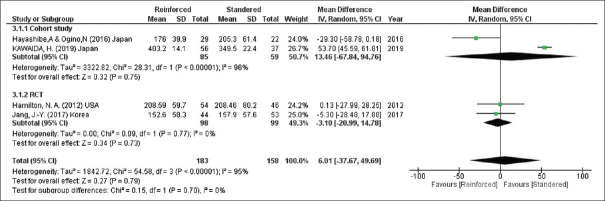

Blood loss during operation

According to four studies (341 participants), no difference could be detected in the blood loss during the operation for both methods (blood loss, mean difference = −12.90, 95% CI = −83.00–57.20, P = 0.72; I2 = 52%) [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Blood loss during the operation. CIs: Confidence intervals, RCTs: Randomised controlled trials, SD: Standard deviation, df: Degree of freedom, IV: Inverse variance

Time of the operation

Turning to the duration of the operation, the two groups had equal time in the surgery according to four studies (341 participants) (time of the operation, mean difference = 6.01, 95% CI = −37.67–49.69, P = 0.79; I2 = 95%) [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Duration of the operation. CIs: Confidence intervals, RCTs: Randomised controlled trials, SD: Standard deviation, df: Degree of freedom, IV: Inverse variance

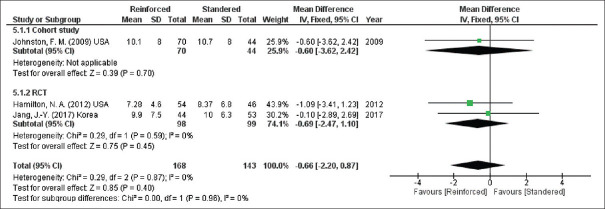

Hospital stay

In addition to that, according to the pooled results from three studies (311 participants), the two groups had equal time of hospitalisation (hospital stay, mean difference = −0.66, 95% CI = −2.20–0.87, P = 0.40; I2 = 0%) [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Hospital stay. CIs: Confidence intervals, RCTs: Randomised controlled trials, SD: Standard deviation, df: Degree of freedom, IV: Inverse variance

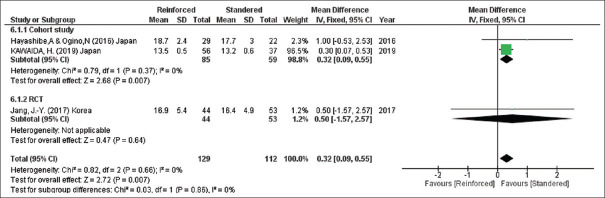

Thickness of pancreas

According to three of the included studies (241 participants), the thickness of the pancreases was less for those who received the slandered group (thickness of the pancreases, mean difference = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.09–0.55, P = 0.007; I2 = 0%) [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Thickness of the pancreases

Publication bias assessment

There was no evidence of publication bias. The funnel plot analysis demonstrated a symmetrical appearance, and the P values were greater than 0.05 for all comparisons according to the BeggMazumdar test and Egger test.

DISCUSSION

Post-operative PF is one of the most challenging issues facing pancreatic surgeons and according to the 2016 ISGPS, ‘Grade A POPF’ is now redefined and described as a ‘biochemical leak’. This is because it has no clinical importance and is no longer considered a true PF. However, Grade B POPF requires a change in the post-operative treatment. For instance, drains may be left in place more than 3 weeks or repositioned through endoscopic or percutaneous procedures. In addition to that, Grade C POPF needs reoperation or leads to single or multiple organ failure and/or mortality as a result of the PF.[17] Countless operative techniques have been adapted to decrease their incidence including somatostatin analogues,[3] prophylactic stenting of the pancreatic duct[4] and pancreatojejunostomy,[6] and many materials have been used to cover the stump after DP including a teres ligament patch,[5] a seromuscular patch of jejunum,[24] falciform ligament patch and fibrin glue[25] and fibrin glue.[26,27,28]

In the era of minimally invasive procedures, the use of staplers for DP has increased dramatically. While some studies reported that the use of PGA for reinforcement after transection of the pancreas with a linear stapler reduces the rate of clinically significant POPF,[10,29] other studies reported that reinforced stapler for pancreatic transection during DP does not decrease the incidence of clinically relevant PF compared to stapler without reinforcement.[19,21]

According to the pooled results of seven studies, the overall incidence of POPF after DP is similar for the two groups. However, the incidence of clinically significant POPF (Grades B and C) is significantly lower in DP with reinforced staplers than DP with bare staplers. Nevertheless, the time of the operation, the blood loss during surgical procedure and the hospital stay after the surgery were similar for both techniques.

While six of the included studies used PGA mesh to reinforce the stapler line, only one study[23] used a stapler reinforced with Biodesign® which is an extracellular matrix biomaterial derived from submucosal tissue from pig small intestine. PGA, a biodegradable polymer, is made up of a simple linear aliphatic polyester. PGA is a synthesised material from glycolic acid monomers through ring-opening polymerisation, and it has low solubility in water and organic solvents because of its high degree of crystallinity.[30] PGA mesh causes an inflammatory process immediately after insertion and is infiltrated by granulation tissue within 3 weeks and the material is usually absorbed after 2–3 months.

PGA mesh has previously been used to repair abdominal wall defects and prevent herniation after laparotomy.[31] In addition to that a combination of fibrin glue with this material have often been used to prevent bile leak after hepatic resection.[32] Moreover, this mesh has been used to decrease the rate of recurrence after thoracoscopic bullectomy.[33]

Regarding Biodesign®, it is an absorbable biomaterial sheet made up of collagen-based extracellular matrix derived from pig small intestinal submucosa. This material is used to decrease the incidence of post-operative staple line leakage and bleeding associated with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.[34]

This study helps resolve the conflict between the included RCTs about whether we should reinforce the stapler to decrease the incidence of POPF or not. In addition to that, to our knowledge, it is the largest meta-analysis in this field because all the studies designed to compare the outcome between reinforced versus bare staplers for DP were included to increase the statistical power of the results.

However, we have to admit the presence of some limitations in this meta-analysis. First, some of the included studies were cohort studies and there is no doubt that a surgeon's selection bias plays a role in the choice of stump closure used for each individual case. Second, the use of Biodesign®SLR was reported in one study only. Therefore, more studies are needed to assess the efficiency of this material in decreasing POPF. Finally, we have to admit the presence of significant heterogeneity in some results.

CONCLUSION

With the shift towards minimally invasive left pancreatectomy, the use of stapled transection has increased dramatically. Although SLR after DP failed to prevent biochemical PF (Grade A POPF), it significantly reduced the rate of clinically relevant POPF in comparison to standard stapling.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kleeff J, Diener MK, Z’graggen K, Hinz U, Wagner M, Bachmann J, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: Risk factors for surgical failure in 302 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2007;245:573–82. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251438.43135.fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adam U, Makowiec F, Riediger H, Benz S, Liebe S, Hopt UT. Pancreatic leakage after pancreas resection. An analysis of 345 operated patients. Chirurg. 2002;73:466–73. doi: 10.1007/s00104-002-0427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarr MG, Group TP. The potent somatostatin analogue vapreotide does not decrease pancreas-specific complications after elective pancreatectomy: A prospective, multicenter, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:556–64. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frozanpor F, Lundell L, Segersvärd R, Arnelo U. The effect of prophylactic transpapillary pancreatic stent insertion on clinically significant leak rate following distal pancreatectomy: Results of a prospective controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2012;255:1032–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318251610f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassenpflug M, Hinz U, Strobel O, Volpert J, Knebel P, Diener MK, et al. Teres ligament patch reduces relevant morbidity after distal pancreatectomy (the DISCOVER Randomized Controlled Trial) Ann Surg. 2016;264:723–30. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawai M, Hirono S, Okada K, Sho M, Nakajima Y, Eguchi H, et al. Randomized controlled trial of pancreaticojejunostomy versus stapler closure of the pancreatic stump during distal pancreatectomy to reduce pancreatic fistula. Ann Surg. 2016;264:180–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uemura K, Satoi S, Motoi F, Kwon M, Unno M, Murakami Y. Randomized clinical trial of duct-to-mucosa pancreaticogastrostomy versus handsewn closure after distal pancreatectomy. Br J Surg. 2017;104:536–43. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H, Zhu F, Shen M, Tian R, Shi CJ, Wang X, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis comparing three techniques for pancreatic remnant closure following distal pancreatectomy. Br J Surg. 2015;102:4–15. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang JY, Shin YC, Han Y, Park JS, Han HS, Hwang HK, et al. Effect of polyglycolic acid mesh for prevention of pancreatic fistula following distal pancreatectomy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:150–5. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.3644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton NA, Porembka MR, Johnston FM, Gao F, Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, et al. Mesh reinforcement of pancreatic transection decreases incidence of pancreatic occlusion failure for left pancreatectomy: A single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2012;255:1037–42. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825659ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto M, Hayashi MS, Nguyen NT, Nguyen TD, McCloud S, Imagawa DK. Use of Seamguard to prevent pancreatic leak following distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 2009;144:894–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrone CR, Warshaw AL, Rattner DW, Berger D, Zheng H, Rawal B, et al. Pancreatic fistula rates after 462 distal pancreatectomies: Staplers do not decrease fistula rates. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1691–7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0636-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sepesi B, Moalem J, Galka E, Salzman P, Schoeniger LO. The influence of staple size on fistula formation following distal pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:267–74. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1715-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ceppa EP, McCurdy RM, Becerra DC, Kilbane EM, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, et al. Does pancreatic stump closure method influence distal pancreatectomy outcomes? J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1449–56. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2825-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guzman EA, Nelson RA, Kim J, Pigazzi A, Trisal V, Paz B, et al. Increased incidence of pancreatic fistulas after the introduction of a bioabsorbable staple line reinforcement in distal pancreatic resections. Am Surg. 2009;75:954–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen EH, Portschy PR, Chowaniec J, Teng M. Meta-analysis of bioabsorbable staple line reinforcement and risk of fistula following pancreatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:267–72. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-2016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery. 2017;161:584–91. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: A new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:ED000142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston FM, Cavataio A, Strasberg SM, Hamilton NA, Simon PO, Jr, Trinkaus K, et al. The effect of mesh reinforcement of a stapled transection line on the rate of pancreatic occlusion failure after distal pancreatectomy: Review of a single institution's experience. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2008.00001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashibe A, Ogino N. Clinical study for pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy with mesh reinforcement. Asian J Surg. 2018;41:236–40. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kondo N, Uemura K, Nakagawa N, Okada K, Kuroda S, Sudo T, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial comparing reinforced staplers with bare staplers during distal pancreatectomy (HiSCO-07 Trial) Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:1519–27. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawaida H, Kono H, Hosomura N, Amemiya H, Itakura J, Fujii H, et al. Surgical techniques and postoperative management to prevent postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatic surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:3722–37. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i28.3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wennerblom J, Ateeb Z, Jönsson C, Björnsson B, Tingstedt B, Williamsson C, et al. Reinforced versus standard stapler transection on postoperative pancreatic fistula in distal pancreatectomy: Multicentre randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg. 2021;108:265–70. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znaa113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiu CC. R3andomized clinical trial of techniques for closure of the pancreatic remnant following distal pancreatectomy (Br J Surg 2009;96:602-607) Br J Surg. 2009;96:1222. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carter TI, Fong ZV, Hyslop T, Lavu H, Tan WP, Hardacre J, et al. A dual-institution randomized controlled trial of remnant closure after distal pancreatectomy: Does the addition of a falciform patch and fibrin glue improve outcomes? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:102–9. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1963-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bassi C, Butturini G, Falconi M, Salvia R, Sartori N, Caldiron E, et al. Prospective randomised pilot study of management of the pancreatic stump following distal resection. HPB. 1999;1:203–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sa Cunha A, Carrere N, Meunier B, Fabre JM, Sauvanet A, Pessaux P, et al. Stump closure reinforcement with absorbable fibrin collagen sealant sponge (TachoSil) does not prevent pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: The FIABLE multicenter controlled randomized study. Am J Surg. 2015;210:739–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park JS, Lee DH, Jang JY, Han Y, Yoon DS, Kim JK, et al. Use of TachoSil(®) patches to prevent pancreatic leaks after distal pancreatectomy: A prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2016;23:110–7. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochiai T, Sonoyama T, Soga K, Inoue K, Ikoma H, Shiozaki A, et al. Application of polyethylene glycolic acid felt with fibrin sealant to prevent postoperative pancreatic fistula in pancreatic surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:884–90. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunatillake P, Mayadunne R, Adhikari R. Recent developments in biodegradable synthetic polymers. Biotechnol Annu Rev. 2006;12:301–47. doi: 10.1016/S1387-2656(06)12009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lak KL, Goldblatt MI. Mesh selection in abdominal wall reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142:99S–106S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashibe A, Sakamoto K, Shinbo M, Makimoto S, Nakamoto T. New method for prevention of bile leakage after hepatic resection. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:57–60. doi: 10.1002/jso.20548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyahara E, Ueda D, Kawasaki Y, Ojima Y, Kimura A, Okumichi T. Polyglycolic acid mesh for preventing post-thoracoscopic bullectomy recurrence. Surg Today. 2021;51:971–7. doi: 10.1007/s00595-020-02191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Washington MJ, Hodde JP, Cohen E, Cote L. Biologic staple line reinforcement for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A case series. Int J Surg Open. 2019;17:1–4. [Google Scholar]