Abstract

Background:

Thoracoscopic enucleation of oesophageal leiomyomas has been adopted by many centres. The procedure when performed in prone position gives good results. The long-term outcome has not been reported earlier. This single-centre study establishes the role of this particular technique.

Methods:

A retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained hospital database was performed and after following the study criteria eleven cases of oesophageal submucosal tumours were included in the study. All patients underwent thoracoscopic enucleation in the prone position by a single surgeon. Peri-operative data were recorded and patients followed up for a mean period of 78 months (range = 24–120 months).

Results:

Thoracoscopic enucleation in prone position was done for all patients with no conversions to an open procedure. Two patients had a mucosal rent during dissection that was repaired. There was no post-operative morbidity greater than Clavien-Dindo Grade 2. Long-term follow-up is available for eight patients (73%) with no recurrence of disease or symptoms.

Conclusion:

Oesophageal submucosal tumours (predominantly leiomyomas) are benign neoplasms with an indolent biological behaviour and deserve a procedure that would serve the purpose of minimal post-operative morbidity coupled with excellent outcome. Thoracoscopic enucleation in the prone position provides a physiological benefit that translates into better peri-operative outcomes without compromising the long-term outcome and should be the preferred form of treatment for oesophageal submucosal tumours.

Keywords: Enucleation, leiomyoma, oesophageal neoplasms, prone position, submucosal tumours, thoracoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Benign lesions of the oesophagus are rare, comprising approximately one-fifth of the total mass lesions of the oesophagus.[1] These submucosal lesions (E-SMTs) are mesenchymal in origin and comprise a spectrum including leiomyomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs), schwannomas, granular cell tumours and lipomas.[1] The characteristic submucosal location and indolent biological behaviour of these neoplasms make them a distinctive pathoneoplastic entity which have a common clinical presentation and subsequently common surgical management. Minimal invasive methods at surgical treatment have been accepted and adopted as the standard of care by an increasing number of institutions. Case reports and small case series have described thoracoscopic enucleation of oesophageal submucosal tumours with acceptable results.[2] Performing thoracoscopic procedures in the prone position has distinct physiological advantages which translate into lesser pulmonary complications and consequently an improved outcome in terms of morbidity.[3,4] The pan-oesophageal anatomical distribution of lesions with treatment rendered in the prone position with both right and left approaches along with long-term outcomes has not been reported from a single centre. We present our experience of thoracoscopic enucleation in the prone position for E-SMTs with excellent long-term outcomes at a tertiary teaching hospital.

METHODS

After obtaining institutional review board approval, with the waiver of consent due to the retrospective nature of the study, a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained hospital database was performed. All cases of E-SMTs treated by minimal invasive approach between January 2011 and December 2020 were considered for the study. Inclusion criteria included the submucosal location of the lesion and treatment by thoracoscopic enucleation in the prone position. Cases requiring an extended resection for reasons like large size and malignant appearance on imaging were excluded from the study. A total of 22 cases of E-SMTs were identified and after following the study criteria eleven cases were included in the study and final analysis. Pre-operative workup to characterise the oesophageal pathology in terms of its location, extent and relation to surrounding structures was done which included an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE) along with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) [Figure 1] followed by cross-sectional imaging (contrast-enhanced computed tomography [CT] scan). The approach to the tumour via the left or right side was based on the location and relation to surrounding structures as evident on imaging. All patients underwent thoracoscopic enucleation in the prone position. Relevant clinical data including demographics, intra-operative and post-operative characteristics were noted [Table 1]. Follow-up protocol included an outpatient visit at 1 week, 3 months and 6 months after surgery. For mid- and long-term follow-up an out-patient visit or alternatively a telephonic conversation with a pre-set questionnaire was carried out at 1, 3 and 5 years.

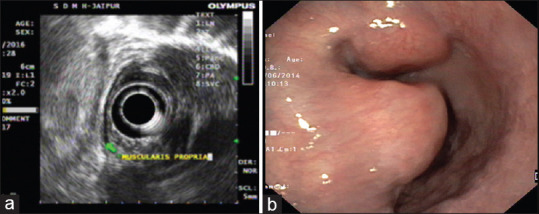

Figure 1.

(a) An endoscopic ultrasound image showing a well-defined hypoechoic lesion arising from muscularis propria of oesophagus suggestive of a submucosal lesion. (b) An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showing a sub mucosal tumour with intact mucosa

Table 1.

Patient demographics and peri-operative characteristics

| Patient characterstics and variables | Mean±SD or Number |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 11 (females=4, males=7) |

| Mean age (years) | 49.4 (range 38-65) |

| Mean duration of symptoms (months) | 11.08 (range=0.5-24) |

| Imaging modality for diagnosis (%) | |

| UGIE | 11 (100) |

| EUS | 11 (100) |

| CECT | 11 (100) |

| FNAB | 3 (27) |

| Number of patients with co-morbidities (%) | 2/11 (18) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |

| Type II diabetes mellitus | |

| Mean tumour size (cm) | 3.54±1.36 |

| Approach (%) | |

| Left | 2 (18) |

| Right | 9 (82) |

| Location of tumour (%) | |

| Upper | 1 (9) |

| Middle | 3 (27) |

| Lower | 7 (64) |

| Mean operative duration (min) | 138.63±9.64 |

| Intra-operative complications (mucosal rent) (%) | 2/11 (18) |

| Post-operative complication (%) | |

| Leak on post-operative imaging | 1 (9) |

| Pulmonary complications | 2 (18) |

| Mean post-operative day for ICD removal | 5.63±3.93 |

| Mean duration of starting oral liquids (days) | 3.27±4.07 |

| Mean length of stay (days) | 6.36±4.3 |

| Mean period of follow-up (months) | 78 (range=24-120) |

| Complications (requiring intervention) | |

| Short term (<1 year) (%) | 1 (9.09) |

| Mid-term (1-3 years) | Nil |

| Long term (5 years) | Nil |

| Readmissions | None |

| Mortality | None |

ICD: Intercostal drain, UGIE: Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound, FNAB: Fine-needle aspiration biopsy, CECT: Contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography

Surgical technique

All thoracoscopic procedures in the prone position underwent general anaesthesia based on a pre-determined protocol. Prophylactic third-generation anti-microbial was administered at induction of anaesthesia. A non-selective intubation was done with a single lumen endotracheal tube with the patient still on the wheel-in trolley followed by placement of a 36 F bougie in the upper oesophagus to be used later during tumour excision. A central venous access and arterial line placement for invasive haemodynamic monitoring was done. The patient was then turned prone. The procedure began by creating pneumothorax through the seventh intercostal space inferior to the angle of the scapula with the insufflating pressure kept at 6–8 mm of mercury. A 10 mm port for the camera was cited through this followed by two working ports in the fifth and eighth intercostal space, of 10 mm and 5 mm calibre, respectively, maintaining the principle of triangulation. The vagus nerve was identified and safeguarded in all cases. Longitudinal oesophageal myotomy was performed overlying the tumour using a diathermy hook. With blunt dissection, the tumour was adequately exposed from the surrounding muscle layer and a stay suture passed through the lesion for optimal traction to aid in enucleation. A 36 F bougie in the cervical oesophagus placed post-intubation was advanced into the stomach to act as a guide and scaffolding to enable tumour dissection off the mucosa. This was carried out by blunt dissection and use of ultrasonic shears (Harmonic Scalpel, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA) for haemostasis. In a case where adhesions precluded safe extirpation separation was done using a long articulating endoscopic linear cutter (Echelon 60 Endopath, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH). Where a mucosal rent did occur, primary repair with 3-0 polydioxanone in continuous manner was performed. The myotomy was closed with 3-0 silk in an interrupted manner [Figure 2]. The bougie was withdrawn into the cervical oesophagus and an intra-corporeal leak test using methylene blue was performed in all cases. The oesophagus distal to the lesion was clamped with atraumatic graspers and methylene blue instilled through the bougie to check the integrity of the myotomy repair in all and the mucosal repair in two patients. The excised mass was removed using a retrieval bag and a 28 F chest tube was placed concluding the procedure. An oral contrast study using water-soluble agent was done on the first post-operative day and liquid intake initiated for the patients if no leak was detected. The patients were discharged after the removal of the chest drain.

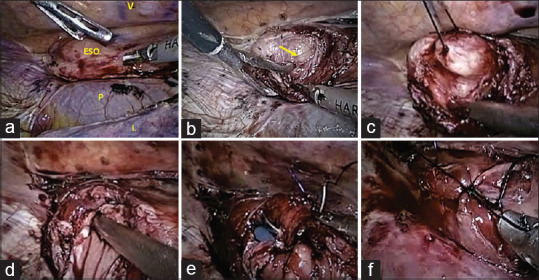

Figure 2.

Intra-operative pictures showing. (a) A thoracoscopic view of mediastinal structures in the prone position showing the oesophagus in relation to the vertebral column (V), pericardium (P) and lung (L). Leiomyoma (block arrow) at the distal third of oesophagus can be seen as an intra-mural bulge. (b) The tumour (block arrow) is seen after a myotomy has been performed. (c) A silk suture is passed through the tumour to provide traction to aid in dissection off the mucosa. (d) The oesophageal lumen is seen after a mucosal rent has occurred (the shaft of the suction canula can be seen in the lumen). (e) The mucosal rent is repaired with a monofilament absorbable suture (polydioxanone). (f) After excising the tumour and repairing the mucosal rent the myotomy is closed in an interrupted manner

RESULTS

Between January 2011 and December 2020, 22 patients were identified with E-SMTs who had undergone surgical correction using a minimal invasive approach. Eleven patients underwent visceral resections due to inherent tumour properties which contradicted an enucleating procedure through thoracoscopy and were thus excluded from the final study group. These included a giant leiomyosarcoma (one), tumours at gastrooesophageal (GE) junction (nine) and the presence of dense adhesions (one). Thoracoscopic enucleation in prone position was performed in eleven patients with no conversion [Table 2].

Table 2.

Results

| Age (years)/sex | Tumour size (mm) | Location | Approach | FNAC | Complication | Hospital stay (days) | Histology | Long-term complication/recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 56/male | 40 | Lower 1/3rd (IA) | Right | Yes | Mucosal rent, pneumonitis | 18 | LM | Esophageal web |

| 40/male | 20 | Upper 1/3rd (abo AOA) | Left | No | Nil | 5 | LM | Nil |

| 47/male | 20 | Middle 1/3rd (JA) | Right | No | Nil | 3 | LM | Nil |

| 38/female | 50 | Middle 1/3rd (JA) | Right | No | Atelectasis, pleural effusion | 5 | LM | LFU |

| 58/male | 60 | Middle 1/3rd (behind AOA) | Left | Yes | Mucosal rent | 7 | LM | Nil |

| 65/male | 30 | Lower 1/3rd (IA) | Right | No | Nil | 10 | LM | Nil |

| 45/female | 30 | Lower 1/3rd (IA) | Right | No | Nil | 5 | LM | Nil |

| 56/male | 50 | Lower 1/3rd (IA) | Right | No | Nil | 3 | LM | Nil |

| 38/female | 20 | Lower 1/3rd (IA) | Right | No | Nil | 5 | LM | Nil |

| 48/female | 40 | Lower 1/3rd (IA) | Right | Yes | Nil | 4 | LM | Nil |

| 52/male | 30 | Lower 1/3rd (IA) | Right | No | Nil | 5 | LM | Nil |

IA: Infra-azygous, JA: Juxta-azygous, AOA: Arch of aorta, LM: Leiomyoma, LFU: Lost to follow-up, FNAC: Fine-needle aspiration cytology

There was a male preponderance (seven males and four females) with a mean age of 49.4 years (range 38–65 years). All patients were symptomatic, with dysphagia being the most common symptom (68%) followed by chest pain (42%). Three patients were referred for surgical intervention with an EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) already in place, suggestive of leiomyoma. Based on the tumour location and laterality, the procedure was performed from the right side in nine patients and through the left side in two patients. The tumour location for right-sided lesions was infra-azygous in seven cases and juxta-azygous in two cases, with the latter sub-group requiring intra-operative division of azygos vein. The two-left sided tumours were located one each, below and above the arch of the aorta, respectively. All right-sided procedures were carried out with three and left-sided with four ports. One patient required a stapled transection due to dense adhesion to underlying mucosa that was safely accomplished using a long articulating endoscopic linear cutter with the oesophageal bougie in-situ. Intraoperatively, two patients had a mucosal rent which was repaired with absorbable monofilament sutures in a continuous manner. The intra-operative leak test was negative in all patients. The mean size of the enucleated tumour was 3.54 cm ± 1.36 with the maximum being 5 × 6 cm [Figure 3]. The mean duration of hospital stay was 6.36 days ± 4.319 (range 3-18 days). Histopathology and immunohistochemistry confirmed all enucleated lesions as leiomyoma (positive for desmin and smooth muscle actin and negative for CD34 and CD117).

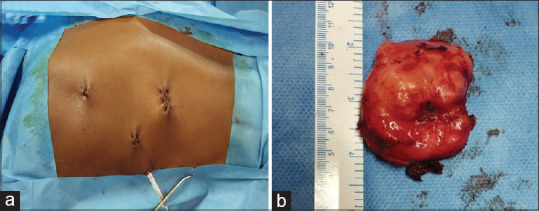

Figure 3.

(a) The port sites after completion of the procedure. (b) Gross specimen of an excised leiomyoma

On the first operative day, one patient had a minimal leak evident on the oral contrast study. The patient was kept nil by mouth along with supportive care and total parenteral nutrition and intercostal chest tube in situ. A repeat oral contrast study done on the 15th post-operative day demonstrated no leak and enabled the resumption of the oral liquid diet. The chest tube was removed on the seventeenth postoperative day. One patient with pleural effusion and atelectasis was managed conservatively with chest physiotherapy and supportive care. Overall, morbidity was seen in these two patients (18.1%) and included a minimal output-controlled leak from the mucosal repair site with subsequent pneumonitis in one patient and self-resolving atelectasis and minimal pleural effusion in the other. This depicts a grade 2 and a grade 1 complication respectively, based on the Clavien-Dindo classification.

Short-term (up to 1 year) follow-up was available for eleven patients (100%), mid-term follow-up (one to 3 years) for ten patients (91%) and long-term follow-up (5 years) for 8 patients (73%) patients. In the short-term follow-up, three patients were symptomatic. One patient (who had a contrast leak in the immediate post-operative period) presented with dysphagia at 3 months and on evaluation was found to have an oesophageal web at GE junction which responded to a single session of endoscopic dilatation. The other two patients presented with retrosternal discomfort at three and 6 months, respectively, and responded to empirical proton pump inhibitors and lifestyle modification. In the mid-term and long-term follow-up, all patients remained symptom-free.

DISCUSSION

The E-SMTs encompass a heterogeneous group of neoplasms that are characterised by a similar presentation, require a sequential evaluation and are treated by surgical extirpation based on the principle of enucleation. These benign lesions are fifty times less common than malignant lesions and account for less than 5% of resected oesophageal tumours.[5] Leiomyomas are distributed throughout the gastrointestinal tract and 10% of these are located in the oesophagus.[6] Nonetheless, it is the most common benign oesophageal neoplasm with incidence in autopsy series ranging from 0.005% to 5.1%.[7,8] Leiomyoma and GISTs share a common analogy with regard to their submucosal location but are distinct entities considering their ultrastructure, immunohistochemical markers and clinical outcome.

Oesophageal leiomyomas have a male preponderance (2:1) with peak incidence in the 3–5th decade.[5] Histologically, they originate from the smooth muscle in the muscularis mucosae or muscularis propria with genesis from the former layer being rarer (7%).[9] Anatomically, their location, predominantly in the middle and distal third of the oesophagus reflects the transformation from striated muscles in the proximal oesophagus to smooth muscles in the distal part.[10] The demographics of the present study also emulate these trends. There were seven males (64%) and four females (36%) in the study group with a mean age of 50.6 years. Location wise, the distribution in the upper, middle and distal third was 9%, 27% and 64%, respectively.

The slow growth of leiomyomas, their submucosal location and compliance of the oesophageal tube leads to a longer duration to diagnosis with a significant proportion remaining asymptomatic (15%–50%) and diagnosed only as an incidental finding.[11] A review of more than eight hundred cases showed that duration of more than 5 years existed in 30% of cases, 2–5 years in another 30% and under 1 year in 40% of cases before the diagnosis was made.[12] The most common presentation is dysphagia followed by retro-sternal or epigastric pain.[12] Leiomyomas are extremely slow-growing lesions with only isolated case reports describing progression to malignant pathology. A study of eighty-four patients with leiomyomas of whom twenty-six (31%) were followed under surveillance, found growth of only 0.5 mm over a mean of 70 months (range 4–288 months) follow-up with no malignant transformation.[13]

Evaluation of foregut pathology proceeds sequentially beginning with an UGIE followed by imaging to characterise the lesion with respect to its possible pathological origin and ascertain its location in relation to the surrounding structures. The critical investigation in evaluating E-SMTs is EUS. It elaborates the oesophageal wall into five layers with leiomyoma located in layer 2–4 and GIST in layer 4.[13] A contrast-enhanced CT scan defines the relation of the lesion to surrounding structure helping in planning the surgical procedure. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan has shown 100% sensitivity for gastric GISTs but only some leiomyomas tend to be PET avid and thus its role as a diagnostic modality is minimal in cases of oesophageal submucosal tumours.[14,15]

Obtaining a pre-operative histological diagnosis remains a contentious issue. It is widely acknowledged that performing a pre-operative EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology or biopsy (FNAB) is not prudent considering the issues of equivocal yield and intervention induced unfavourable factors which could preclude a safe dissection. The sub-mucosal location itself proves to be a limiting factor as endoscopic biopsies often do not reach the muscularis propria with a failure rate up to 50% and an inadequate tissue volume to run immunohistochemistry in 66% of cases.[16] An attempt at tissue diagnosis also increases the possibility of adhesion formation to the mucosa distorting the anatomical planes and subsequently increasing the possibility of a mucosal breach with the attendant risk of oesophageal leak and mediastinitis. Bonavina et al. reported mucosal perforation in 50% of patients undergoing FNAB and only 8% in those who did not undergo biopsy.[17] In the present study, three patients were seen and taken up for surgery after endoscopic biopsy had already been performed. Two of these patients had a mucosal rent which were repaired and the third patient required severance using an endoscopic linear cutter without mucosal breach. A satisfactory outcome was eventually achieved in all of these patients. None of the other eight patients who underwent upfront surgery had a mucosal perforation. Taking into account the aforementioned patho-clinical factors, coupled with the extremely low incidence of GIST as compared to leiomyoma and a high negative predictive value of EUS, a pre-operative working diagnosis based on EUS is sufficient to plan the eventual surgical management.

Symptomatic lesions warrant surgical removal. Other indications for surgery include a size >5 cm, atypical findings on imaging, presence of mucosal abnormalities on endoscopy and an increasing size for lesions kept under surveillance.[18] The treatment rendered should have a minimal morbidity as the lesion itself is benign with an extremely low probability to malignant progression. A minimal invasive approach based on the principle of enucleation has proved to be an optimal strategy to extirpate these lesions with oesophagectomy reserved only for larger lesions (8–10 cm), an annular morphology, multiple or diffuse involvements or features suggestive of leiomyosarcoma.[19] A retrospective study of 40 patients of oesophageal leiomyoma showed complete resolution of symptoms at a mean follow-up of 27 months with no cases of recurrence after enucleation.[20] Similar results were reciprocated in the present study wherein thoracoscopic enucleation was performed for all patients that provided symptomatic resolution and relieved symptoms on long-term follow-up. Thus, enucleation, as an organ-preserving surgical approach, can be considered a blanket technique for virtually all E-SMTs.

The benefits of minimal invasive surgery are now well established, with less post-operative pain leading to early mobilisation and consequently decreased pulmonary complications proving the foremost factor motivating foregut surgeons to adopt thoracoscopic approach instead of the much morbid open thoracotomy. Thoracoscopic surgery in the lateral decubitus position is widely practiced but respiratory mechanics stay compromised considering that the non-dependent lung collapses and the dependent lung is compressed by pressure from the mediastinum and abdominal contents. The prone position with the aid of gravity induces the cardiopulmonary organs to shift towards the anterior chest wall while concomitantly retracting the oesophagus from the vertebra and the artificial pneumothorax compresses the lung without manual retraction and without the need for selective single lung ventilation. The result is two-fold: Improved respiratory mechanics and optimal visualisation of the surgical field.[21] As compared to the lateral decubitus position there is increased functional residual capacity, better ventilation-perfusion matching and consequently better intra-operative oxygenation.[22] With regard to conduction of the procedure itself, the view is superior with a wide working space, need for less trocars, decreased blood loss due to the pneumothorax and better ergonomics.[23] All these factors translate into decreased pulmonary complications and expeditious recovery.

Thoracoscopic enucleation of oesophageal submucosal tumours in prone position is aided by anatomical factors. Favourable ergonomics coupled with the fact that most oesophageal SMTs tend to occur and project out of the right wall of the oesophagus in the lower and middle third make thoracoscopic enucleation in prone position a preferred approach by an increasing number of surgeons and the procedure can be accomplished with the good outcome with or without ligation of the azygous vein.[24] In the present study, the approach was based on anatomical rationality, with the two lesions in relation to the arch of the aorta, one above and one behind that were dealt with from the left side. Importantly, the site of enucleation remains a ‘locus minoris resistentiae’ and closure of myotomy should be done to prevent loss of peristalsis, bulging of the mucosa, and formation of pseudodiverticulum leading to dysphagia.[18] Myotomy closure was done for all our patients and follow-up revealed no long-term sequelae in the form of motility impairment or dysphagia in any of them.

Thoracoscopic enucleation of oesophageal leiomyoma and oesophagectomy in prone position was initially reported in 1992.[25] There have only been small case series and reports describing enucleation in the prone position [Table 3]. Palanivelu et al. have described prone position for their 12 patients exclusively having mid-oesophageal lesions which were approached from the right side, with 58.3% of patients completing long term follow-up.[21] Similarly, Claus et al. reported on ten patients having undergone similar surgery but with a shorter follow-up of 3 months only.[23]

Table 3.

Studies describing thoracoscopic enucleation of oesophageal mesenchymal tumours in prone position

| Author (year) | Number cases (male/female) | Tumour size (mm) | Approach (right/left) | Preoperative FNAB | Final Pathology (leiomyoma/GIST/others) | Operation time (min) | Blood loss | Morbidity | Hospital stay (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zaninotto et al. (2006)[26] | 2 (1/1) | N/A | 2/0 | 0/2 | N/A | 90-180 | N/A | 0/2 | 3-10 |

| Yamada et al. (2007)[27] | 1 (0/1) | 30 | 1/0 | 0/1 | 0/1/0 | 152 | Minimal | 0/1 | 10 |

| Palanivelu et al. (2007)[21] | 12 (9/3) | 50-60 | 12/0 | 0/12 | 10/2/0 | 85-128 | Minimal | 2/12 Dysphagia, pneumonia | 3-7 |

| Dapri et al. (2010)[19] | 1 (0/1) | 50 | 1/0 | 1/1 | 1/0/0 | 85 | Minimal | 0/1 | 3 |

| Shimada et al. (2012)[28] | 1 (1/0) | 40 | 1/0 | 0/1 | 1/0/0 | N/A | N/A | 0/1 | 7 |

| Claus et al. (2013)[23] | 10 (6/4) | 25-90 | 10/0 | N/A | 10/0/0 | 45-135 | Minimal | 0/10 | 2-5 |

| Shichinohe et al. (2014)[24] | 2 (1/1) | 50-45 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/0/1 | 181-174 | Minimal | 0/2 | 7-8 |

| Maki et al. (2015)[29] | 1 (1/0) | 45 | 1/0 | 0/1 | 1/0/0 | N/A | N/A | 0/1 | 12 |

| Matsumoto et al. (2016)[30] | 1 (0/1) | 60 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/0/1 | N/A | Minimal | 0/1 | 8 |

| This study (2020) | 11 (7/4) | 20-60 | 9/2 | 2/11 | 11/0/0 | 120-150 | Minimal | 2/11 Mucosal rent, Pneumonitis | 3-18 |

| Total | 42 (26/12) | 20-90 | 38/4 | 4/42 | 35/3/2 | 45-180 | Minimal | 4/42 | 3-18 |

FNAB: Fine-needle aspiration biopsy, GIST: Gastro intestinal stromal tumours, N/A: Not available

This study encompasses lesions in the upper, middle and lower third of oesophagus with the surgical procedure performed in the right as well as left prone position. With a 91% mid-term and a 73% long-term follow-up, with no recurrence of the disease and its symptoms, it establishes the advantages of the prone position for thoracoscopic procedures with excellent outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Thoracoscopic enucleation of submucosal tumours with the patient in prone position is a highly effective method with many inherent advantages. EUS confirming the sub-epithelial location of the neoplasm is sufficient enough to proceed with surgical enucleation for these mid-sized lesions. An attempt at pre-operative determination of histopathology may compromise the surgical outcome. The natural history of these submucosal tumours offers the advantage of enucleation serving as a complete treatment for these lesions and the excellent long-term outcome has been shown by this study. High-volume centres with expertise in minimally invasive surgery should be able to reproduce excellent long-term outcomes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beard KW, Reavis KM. Submucosal tumors of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. In: Yeo CJ, Gross SD, editors. Shakelford’s Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2018. pp. 496–514. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hihara J, Mukaida H, Hirabayashi N. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the esophagus: Current issues of diagnosis, surgery and drug therapy. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:6. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2018.01.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biere SS, Maas KW, Bonavina L, Garcia JR, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Rosman C, et al. Traditional invasive vs.minimally invasive esophagectomy: A multi-center, randomized trial (TIME-trial) BMC Surg. 2011;11:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palanivelu C, Prakash A, Senthilkumar R, Senthilnathan P, Parthasarathi R, Rajan PS, et al. Minimally invasive esophagectomy: Thoracoscopic mobilization of the esophagus and mediastinal lymphadenectomy in prone position-experience of 130 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choong CK, Meyers BF. Benign esophageal tumors: Introduction, incidence, classification, and clinical features. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;15:3–8. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(03)70035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine MS, Buck JL, Pantongrag-Brown L, Buetow PC, Hallman JR, Sobin LH. Fibrovascular polyps of the esophagus: Clinical, radiographic, and pathologic findings in 16 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:781–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.4.8610549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Postlethwait RW, Musser AW. Changes in the esophagus in 1,000 autopsy specimens. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1974;68:953–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer MD, Gibb SP, Ellis FH., Jr Giant leiomyoma of esophagus. J Surg Oncol. 1986;33:166–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930330304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatch GF, 3rd, Wertheimer-Hatch L, Hatch KF, Davis GB, Blanchard DK, Foster RS, Jr, et al. Tumors of the esophagus. World J Surg. 2000;24:401–11. doi: 10.1007/s002689910065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Madankumar MV, John SJ, Senthilkumar R. Minimally invasive therapy for benign tumors of the distal third of the esophagus – A single institute's experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:20–6. doi: 10.1089/lap.2007.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obuchi T, Sasaki A, Nitta H, Koeda K, Ikeda K, Wakabayashi G. Minimally invasive surgical enucleation for esophageal leiomyoma: Report of seven cases. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23:E1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seremetis MG, Lyons WS, deGuzman VC, Peabody JW., Jr Leiomyomata of the esophagus. An analysis of 838 cases. Cancer. 1976;38:2166–77. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197611)38:5<2166::aid-cncr2820380547>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Codipilly DC, Fang H, Alexander JA, Katzka DA, Ravi K. Subepithelial esophageal tumors: A single-center review of resected and surveilled lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:370–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamiyama Y, Aihara R, Nakabayashi T, Mochiki E, Asao T, Kuwano H, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography: Useful technique for predicting malignant potential of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Surg. 2005;29:1429–35. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dendy M, Johnson K, Boffa DJ. Spectrum of FDG uptake in large (>10 cm) esophageal leiomyomas. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:E648–51. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.11.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baysal B, Masri OA, Eloubeidi MA, Senturk H. The role of EUS and EUS-guided FNA in the management of subepithelial lesions of the esophagus: A large, single-center experience. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:308–16. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.155772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonavina L, Segalin A, Rosati R, Pavanello M, Peracchia A. Surgical therapy of esophageal leiomyoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:257–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samphire J, Nafteux P, Luketich J. Minimally invasive techniques for resection of benign esophageal tumors. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;15:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(03)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dapri G, Himpens J, Ntounda R, Alard S, Dereeper E, Cadière GB. Enucleation of a leiomyoma of the mid-esophagus through a right thoracoscopy with the patient in prone position. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:215–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0514-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang G, Zhao H, Yang F, Li J, Li Y, Liu Y, et al. Thoracoscopic enucleation of esophageal leiomyoma: A retrospective study on 40 cases. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:279–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Senthilkumar R, Annapoorni S, Jategaonkar PA. Thoracoscopic management of benign tumors of the mid-esophagus: A retrospective study. Int J Surg. 2007;5:328–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pelosi P, Croci M, Calappi E, Cerisara M, Mulazzi D, Vicardi P, et al. The prone positioning during general anesthesia minimally affects respiratory mechanics while improving functional residual capacity and increasing oxygen tension. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:955–60. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199505000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Claus CM, Cury Filho AM, Boscardim PC, Andriguetto PC, Loureiro MP, Bonin EA. Thoracoscopic enucleation of esophageal leiomyoma in prone position and single lumen endotracheal intubation. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3364–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2918-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shichinohe T, Kato K, Ebihara Y, Kurashima Y, Tsuchikawa T, Matsumoto J, et al. Thoracoscopic enucleation of esophageal submucosal tumor by prone position under artificial pneumothorax by CO2 insufflation. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24:e55–8. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828f71e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuschieri A, Shimi S, Banting S. Endoscopic oesophagectomy through a right thoracoscopic approach. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1992;37:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaninotto G, Portale G, Costantini M, Rizzetto C, Salvador R, Rampado S, et al. Minimally invasive enucleation of esophageal leiomyoma. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1904–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0838-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada M, Niwa Y, Matsuura T, Miyahara R, Ohashi A, Maeda O, et al. Gastric GIST malignancy evaluated by 18FDG-PET as compared with EUS-FNA and endoscopic biopsy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:633–41. doi: 10.1080/00365520601040450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimada Y, Okumura T, Nagata T, Sawada S, Yoshida T, Yoshioka I, et al. Successful enucleation of a fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography positive esophageal leiomyoma in the prone position using sponge spacer and intra-esophageal balloon compression. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;60:542–5. doi: 10.1007/s11748-012-0027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maki K, Takeno S, Nimura S, Yamana I, Shimaoka H, Hashimoto T, et al. Prone position is useful in thoracoscopic enucleation of esophageal leiomyoma. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2015;9:165–70. doi: 10.1159/000382071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto S, Masato W, Nobuhiro S, Kenichiro K, Kazuyoshi N. A case of esophageal schwannoma diagnosed preoperatively and performed left thoracoscopic enucleation in the prone position. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2016;77:1073–7. [Google Scholar]