Abstract

Introduction:

Household food insecurity (HFI) is a persistent public health issue in Canada that may have disproportionately affected certain subgroups of the population during the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of this systematic review is to report on the prevalence of HFI in the Canadian general population and in subpopulations after the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020.

Methods:

Sixteen databases were searched from 1 March 2020 to 5 May 2021. Abstract and full-text screening was conducted by one reviewer and the inclusions verified by a second reviewer. Only studies that reported on the prevalence of HFI in Canadian households were included. Data extraction, risk of bias and certainty of the evidence assessments were conducted by two reviewers.

Results:

Of 8986 studies identified in the search, four studies, three of which collected data in April and May 2020, were included. The evidence concerning the prevalence of HFI during the COVID-19 pandemic is very uncertain. The prevalence of HFI (marginal to severe) ranged from 14% to 17% in the general population. Working-age populations aged 18 to 44 years had higher HFI (range: 18%–23%) than adults aged 60+ years (5%–11%). Some of the highest HFI prevalence was observed among households with children (range: 19%–22%), those who had lost their jobs or stopped working due to COVID-19 (24%–39%) and those with job insecurity (26%).

Conclusion:

The evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic may have slightly increased total household food insecurity in Canada during the pandemic, especially in populations that were already vulnerable to HFI. There is a need to continue to monitor HFI in Canada.

Keywords: food insecurity, COVID-19, systematic review, underserved populations, Canada

Highlights

This review examined household food insecurity (HFI) during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, with data collected between April 2020 and April 2021.

The reported HFI prevalence among the general population ranged from 14% to 17%. Subpopulations most vulnerable to HFI included households whose working-age members lost their employment (range: 24%–39%) or were job-insecure (26%) and households with children (range: 19%–22%). The certainty of evidence for most findings was low to very low, which means the interpretation could change as new research findings emerge.

The evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic may have slightly increased total household food insecurity in Canada during the pandemic, especially in populations that were already vulnerable to HFI.

New research on the impacts of COVID-19 on household food insecurity in the territories, in remote communities and among Indigenous and racialized populations is needed.

Policies and interventions are needed to reduce HFI in Canada within the context of the pandemic, the pandemic recovery period and beyond.

Introduction

Household food insecurity (HFI) is a persistent public health issue in Canada and can be understood as a harmful lack in the basic human right to food.1,2 It is a marker of both deprivation and impoverishment and is a potent social determinant of health.3 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 in 8 households (12.7%) in Canada were food-insecure,1 representing 4.4 million Canadians, including 1.2 million children.1

The measurement and monitoring of household food insecurity in Canada adopts a narrow focus, defining food insecurity as the inadequate or insecure access to food due to financial constraints. In Canada nationally, and in this paper, household food insecurity is operationalized using responses to the Household Food Security Survey Module.4 Research has consistently demonstrated that those living in food-insecure households have poorer mental, physical and oral health, report greater stress and are more likely to suffer from chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and mood and anxiety disorders.5-9 HFI is also associated with more frequent hospitalizations and early death.10 Health care costs among severely food-insecure adults are more than double that of food-secure adults, even after adjusting for well-established social determinants of health, such as education and income levels.11

Monitoring of HFI in Canada for almost two decades has shown that some segments of society are more affected than others. For example, one-third (33.1%) of female-led, lone-parent households are food-insecure.1 HFI also differs markedly by Indigenous status and cultural group. Some of the highest rates of food insecurity have been found among households in which the respondent identified as Indigenous (28.2%) or Black (28.9%).1 While being unemployed can contribute to HFI, data collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic show that most food-insecure households had members who were in the workforce.1,12 In 2017–2018, two out of three (65.0%) food-insecure households reported their main source of income as wages or salaries from employment rather than social assistance, employment insurance or seniors’ pensions.1 Another study found that most food-insecure working households had members that worked in low-wage, temporary or part-time jobs.12 The COVID-19 pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on some of these same subpopulations in terms of both COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations, as well as indirect effects such as unemployment.13

To inform HFI policy and action in Canada, we undertook a systematic review of the prevalence of HFI in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of this review was to report on the prevalence of HFI in the general population, and to identify subpopulations that may be more affected by HFI. This is important, as there is speculation that the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected household food insecurity among vulnerable subgroups.13

Methods

Review scope and team

This systematic review built upon the studies identified by a rapid review of the evidence on the prevalence of HFI in North America during the COVID-19 pandemic conducted by the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools (NCCMT).14 The methods used in that rapid review differed from a traditional systematic review in terms of the screening process. In this case, only one reviewer screened the titles and abstracts, as opposed to the usual two people independently screening the abstracts and full text for inclusion. All inclusions were later verified by an independent second reviewer. The list of included studies was also confirmed with two subject matter experts to ensure that no studies were missing.

Using the studies with Canadian data identified by the NCCMT rapid review, our multidisciplinary team, with expertise in knowledge synthesis, epidemiology, chronic and infectious diseases and public health, undertook independent data extraction, risk of bias assessment and quality of evidence evaluation. The review methods were established prior to the conduct of the review and carried out with no significant deviations. The outcome domain to be assessed was HFI.

Search strategy, inclusion criteria and selection process

As part of the original NCCMT rapid review, 16 databases were searched from 1 March 2020 up to and including 5 May 2021, using key terms related to food insecurity. A full copy of the search strategy is available online.15 Searches were limited to English- and French-language studies, and there were no restrictions based on publication status: peer-reviewed, pre-print and non–peer reviewed sources were included. All identified references were exported into DistillerSR systematic review software (Evidence Partners, Inc., Ottawa, ON, Canada) and duplicates were removed. A single reviewer screened all titles and abstracts for potential eligibility. Another reviewer screened full-text articles of all potentially eligible studies for final inclusion. These inclusions were verified by a second reviewer at the data extraction stage. Conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer. More detailed information about the rapid review can be found elsewhere.14

In the current systematic review, we included studies from the NCCMT rapid review that reported on the prevalence of HFI in Canadian households. Studies that included households outside of Canada were only included if they reported on Canadian HFI separately. We included data collected after the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic (11 March 2020). Studies that reported a comparison to prepandemic values were included if they provided data on HFI prevalence during the pandemic.

Data extraction

A form was developed to extract data on key study characteristics (e.g. study design, date of study, tool used to measure HFI), participant characteristics (e.g. demographic and socioeconomic variables) and HFI prevalence outcomes (data extraction form available upon request). The form was pre-tested by all three reviewers to ensure clarity and consistency and that all the necessary information to address the research topic was extracted. For each HFI outcome, the prevalence, numerator and denominator were extracted along with the confidence interval, range and/or standard deviation.

Prevalence estimates were extracted for the general population as well as for subgroups of interest, which were identified in consultation with subject matter experts as well as policy makers at the Public Health Agency of Canada. These subgroups were: low-income households, single-parent households, Indigenous households, households with children, home ownership status (owner, renter), main source of income of household head, employment status of household head, sex or gender of the household head, race or racial identity of household head, and sexual orientation of the household head. Subpopulation analysis was not limited to these populations, and other affected groups were included in the analysis as necessary. One reviewer extracted the study characteristics and outcomes, and a second reviewer verified the extracted information. Any discrepancies found by the verifier were discussed and resolved by consensus. In the event of missing or unclear data, the original authors of the studies were contacted.

Risk of bias and certainty of evidence appraisal

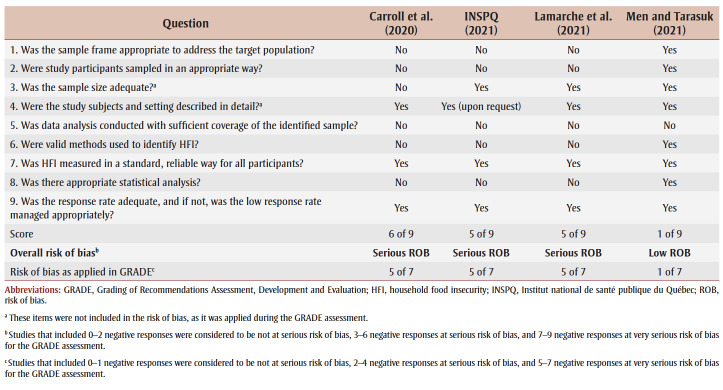

We first assessed the risk of bias of individual studies using a validated critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies designed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI).16 The checklist includes nine questions focussed on assessing selection and information bias. We then assessed the certainty of evidence of each HFI outcome (total HFI, to include marginal, moderate and severe HFI vs. moderate and severe HFI) by applying the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology.17

Two modifications were made to the JBI critical appraisal tool when applying risk of bias within the GRADE assessment. Question 3, pertaining to sample size, was removed, as this question was assessed during the GRADE assessment and we did not want to double penalize any study. Question 4, pertaining to the detailed description of subjects and setting, was considered not applicable, as this item relates to an issue of reporting rather than the study’s risk of bias. Therefore, seven questions in total were included in the risk of bias assessment as it was utilized in the GRADE assessment. Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias for each study. Reviewers resolved conflicts through consensus or consultation with a third reviewer. In the event of missing or unclear data, the original authors of the included studies were contacted.

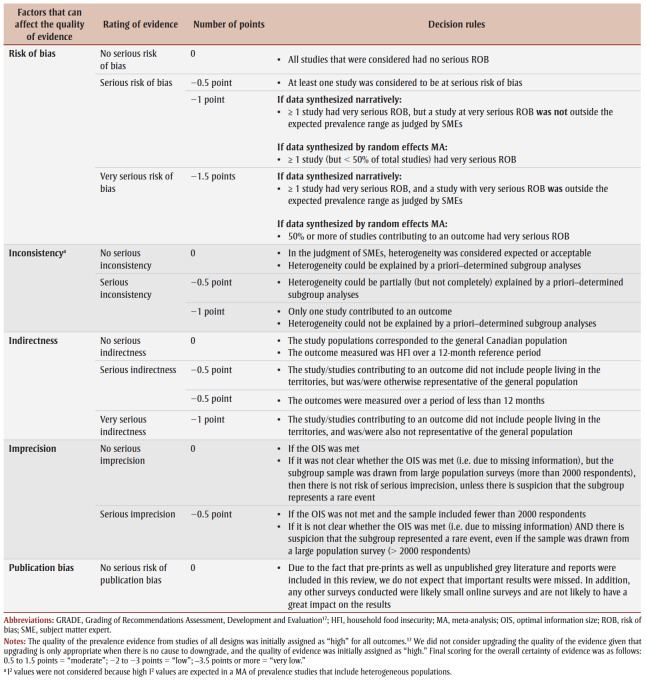

In the absence of a formal framework for prevalence in GRADE, we used the GRADE framework for assessment of incidence estimates in the context of prognostic studies.17 We then made specific adaptions, similar to what others have done18 (details available upon request). One reviewer assessed the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome and another verified the assessment, with disagreements resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. Details of the GRADE decision framework are outlined in Table 1. Following guidelines,17 we initially assigned the certainty of evidence from studies of all designs as “high” for all outcomes, with final level of certainty rating scored as high (0 point loss), moderate (−0.5 to −1.5 points), low (−2 to −3 points) or very low (−3.5 points or more).

Table 1. GRADE decision rules framework as applied in the systematic review on household food insecurity, Canada, March 2020 to May 2021.

Synthesis methods

We conducted a narrative synthesis of the evidence for the research question according to overall findings that emerged from the literature. Individual studies were compared based on the characteristics of the populations, the outcome measures and the reference time period. Meta-analyses were planned if more than two studies were available that adequately reported similar data suitable for pooling.

Results

Study selection

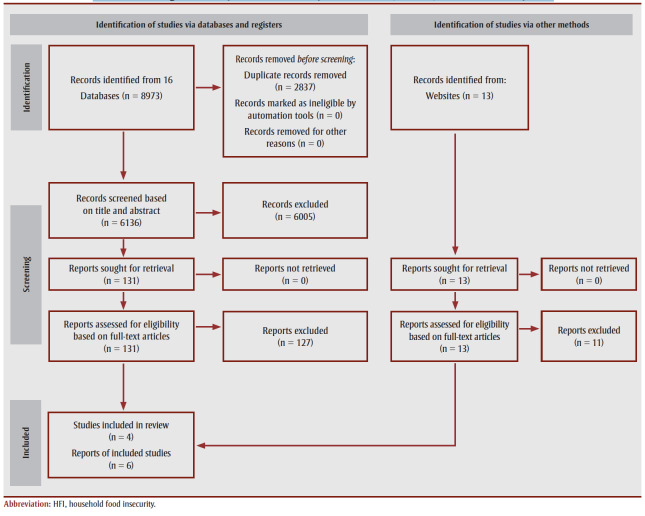

Figure 1 presents the study selection process using the PRISMA flow diagram.19 Reasons for exclusion were not reported due to the rapid time frame of the NCCMT rapid review. A total of 8986 studies were identified in the search (8973 from databases and registers and 13 from other sources), of which 144 were deemed potentially relevant. Six publications, representing four unique datasets, were deemed eligible for inclusion in this review.13,20-24 Three studies13,20,21 reported findings from the same dataset collected in May 2020 as part of the Canadian Perspectives Survey Series (CPSS-2) from Statistics Canada. All three CPSS-2 studies reported prevalence values within 1% of each other, with small differences due to criteria for inclusion of data in the final analysis. Among these studies,13,20,21 we excluded two studies and included only the study by Men and Tarasuk13 in our review, as this study reported on HFI in the most detail for the subpopulations of interest and was the only peer-reviewed study utilizing the data. Four studies were therefore ultimately included in the current review.13,22-24

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of study selection for HFI systematic review, Canada, March 2020 to May 2021.

Study characteristics

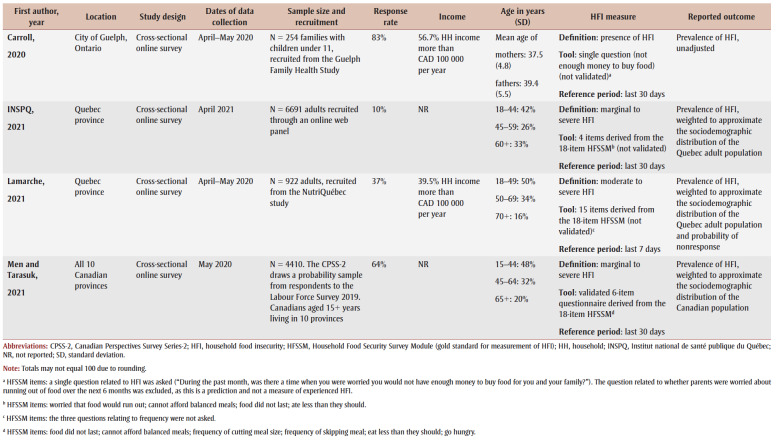

The study characteristics are included in Table 2. All four studies utilized web surveys to collect data. Two studies were large, population-based, cross-sectional surveys13,24 and two studies were cross-sectional surveys conducted within the context of an ongoing longitudinal cohort study.22,23 Three studies were peer-reviewed13,22,23 and one was a non–peer reviewed government report.24 Sample sizes varied from 254 to 6691 participants. Each study used a different instrument to measure HFI and different criteria to define HFI. For example, one study22 defined HFI as moderate or severe experiences of HFI, whereas the other studies included marginal, moderate and severe experiences of HFI.13,23,24 Three studies measured HFI over the previous 30 days,13,23,24 while one study22 used a reference period of 7 days. Three studies collected data in the first wave of the pandemic, between April and May 2020,13,22,23 and one in the third wave, in April 2021.24

Table 2. Selected study characteristics, systematic review of household food insecurity in Canada, March 2020 to May 2021.

Risk of bias in studies

A summary of the risk of bias assessments is provided in Table 3, with detailed assessments available upon request. Serious concerns about risk of bias were found for three of the four included studies,22-24 while the remaining study was assessed at low risk of bias.13

Table 3. Risk of bias assessments for systematic review of HFI, Canada, March 2020 to May 2021.

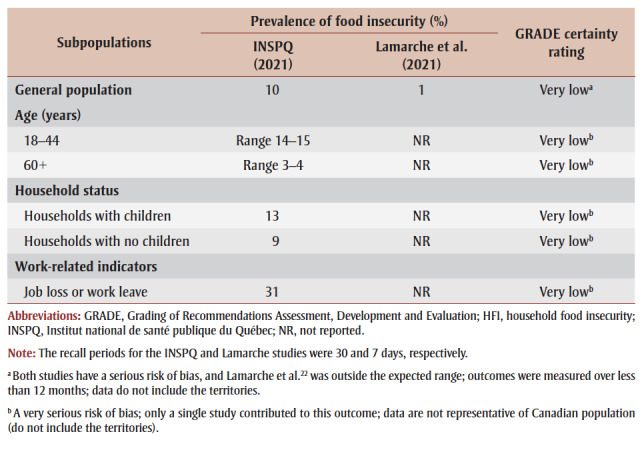

Prevalence of HFI

The prevalence of total HFI for the general population (including marginal, moderate and severe HFI) ranged from 14% to 17% across included studies (low certainty; Table 4). Thus, the evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic may have slightly increased total household food insecurity. The prevalence of moderate and severe HFI over the last 30 days was 10% (very low certainty; Table 5). The prevalence of moderate and severe HFI over the last 7 days was 1% (very low certainty; Table 5). The COVID-19 pandemic may have increased the prevalence of moderate and severe HFI, but the evidence is very uncertain and new evidence may change the interpretation of this data.

Table 4. Prevalence of total household food insecurity (marginal, moderate and severe) among selected subpopulations from a systematic review of HFI, Canada, March 2020 to May 2021.

Table 5. Prevalence of moderate and severe household food insecurity among selected populations from a systematic review of HFI, Canada, March 2020 to May 2021.

|

Data by subgroup for all levels of HFI are summarized below. GRADE was applied to all subgroup analyses, as detailed in Table 4 and 5.

Households with children

Two studies reported higher HFI prevalence in households with versus without children (22% vs. 16% and 19% vs. 12%, respectively); however, no formal statistical tests were conducted for between-group differences, as confidence intervals were not reported in the original studies.13,24

Age

Two studies reported on HFI prevalence and age of the primary respondent.13,24 One study found that the highest prevalence of HFI was in those aged 18 to 44 (range: 21%–22%) and the lowest prevalence in those aged 60 and older (range: 9%–11%).24 A second study found that respondents aged 25 to 34 years had the highest HFI prevalence (range: 18%–23%) among all age groups, whereas those aged 65 and older had the lowest prevalence (range: 5%–7%).13 No statistical testing was reported for between-group differences.

Gender

Two studies found similar HFI prevalence by respondent’s gender, with 17% in both men and women in one study24 and 15% in men and 14% in women in another study.13 A third study found similar prevalence of HFI among middle- and high-income parents in Ontario, ranging from 9% for mothers to 5% for fathers.23

Living conditions

One study found that HFI among those living in apartments, flats, or double, row or terrace housing was 19%, and 12% in those living in single, detached houses.13 The same study reported HFI in rural (17%) and urban (14%) residents.13 A second study found similar HFI prevalence among urban (10% in metropolitan region residents) and rural residents (11%).24

Immigrant status

One study found that HFI was 22% among immigrants and 16% among non-immigrants,24 while a second found similar HFI prevalence between immigrant status (15% immigrants vs. 14% Canadian-born).13

Education

Two studies found HFI prevalence to be between 15% and 20% among those with a high school diploma and 11% to 12% among those with a university degree.13,24

Marital status

One study described HFI prevalence by marital status, reporting 21% HFI among single or never married populations versus 10% among married couples.13

Employment circumstances

Two studies found different HFI prevalence by employment circumstances.13,24 One found that among those who were absent from work in the last week because of a business closure or layoff due to COVID-19, the prevalence of HFI was 32% (compared to 11% for those at work without absence). The study also reported that 26% of job-insecure individuals experienced HFI compared with 8% of their job-secure counterparts.13 Similarly, a second study found that HFI was high for people experiencing job loss or work leave (39%).24 The same study also found that food insecurity was at least twice as prevalent among applicants for Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) (28%) and employment insurance (EI) (23%) as among non-applicants (11%).24

Overall, the evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic may have resulted in an increase in prevalence of HFI among the known vulnerable subgroups identified above. Due to the lack of data, we were not able to assess levels of HFI among those with vulnerabilities related to household income or housing status, nor among households with Indigenous members or racialized communities. Their omission should not preclude concern for their continued or increased HFI during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to determine the prevalence of HFI in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population and in subpopulations. We found four studies that assessed HFI, three in the early pandemic during the first wave (April–May 2020) and one during the third wave (April 2021). These studies reported a prevalence of 14% to 17% for the general population. Results further indicated that households with children, households with members who had lost their jobs or stopped working due to the pandemic and households where members faced job insecurity (might lose job) had the highest prevalence of HFI. In addition, working-age populations (aged 18–44) were most affected; however, these differences should be interpreted cautiously; no statistical testing was conducted to determine whether differences were statistically significant, as confidence intervals were not reported in these studies. Consistent with prepandemic studies, there were low rates of HFI among seniors, in line with previous evidence demonstrating the protectiveness of the guaranteed annual income pension program.25

The certainty of evidence for most findings was low to very low, which means the interpretations could change as new research findings emerge. We believe that the true prevalence of HFI may be greater than reported in these studies, particularly among vulnerable subgroups such as those living in remote regions of Canada, low-income individuals and those in tenuous living situations—not all of whom were captured by the studies included in this review. The reasons for this are explicated below.

First, HFI in territories, remote or isolated communities and Indigenous populations was not specifically assessed in any of the studies, due to a lack of data. The prevalence of HFI has traditionally been higher in these populations, and while they represent a small population, their exclusion could contribute to an overall underestimation of HFI prevalence in Canada. Two of the four studies were conducted in Quebec, which had the lowest HFI prevalence rate of all the provinces and territories before the pandemic, in 2017–2018 (11.1% vs. 12.7% across Canada).1

Second, all data came from web-based surveys, which may have favoured the participation of more affluent populations with more time and resources, and underrepresented disadvantaged populations who are at higher risk of HFI. For instance, two studies included a large proportion of older people, who are traditionally more food secure than the general population of Canada,22,24 and two studies included a large proportion of people with a higher average income (>CAD100 000) than the general population.22,23 Such populations tend to have lower rates of HFI. Thus, the use of a web survey may have underestimated the prevalence of HFI.

Third, as data were mostly collected in the early pandemic (April–May 2020), some households may not yet have fully experienced the impact of employment and income loss on their HFI.

Fourth, a 7-day or 30-day reference period is not as sensitive as a 12-month period to capture HFI, and thus we would expect HFI over the year to be higher. Given that three of the four studies were conducted at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic,13,22,23 it was not possible for researchers to use a 12-month period to calculate HFI during the pandemic. However, as the pandemic has now been ongoing for nearly two years at the time of writing, future studies should use an expanded time period to collect these data.

To determine whether the COVID-19 pandemic–associated public health measures influenced HFI prevalence, a comparison to prepandemic data is needed. While a direct comparison of these data to prepandemic levels of HFI is not possible due to differences in methodology, we are nonetheless able to make indirect comparisons using Statistics Canada data. A recent report, utilizing the CPSS-2 data, found that one in seven households in the 10 provinces were affected by HFI in April 2020.20 After adjusting for differences in the questionnaire and reference time period, the authors found that food insecurity was significantly higher during the early COVID-19 pandemic in comparison to Statistics Canada 2017–2018 data:21 14.6% versus 10.5%, respectively. Unfortunately, this was a 30-day measure collected in April 2020 and we do not have data describing what happened after this date. Data from the Institut national de sant publique du Qubec (INSPQ) at various time points between August 2020 and April 2021 demonstrate that HFI remained relatively stable in Quebec over time (range: 17%–19%)*; however, these findings may not be directly generalizable to other Canadian provinces and territories.

This review shows that people in working-age households, households with children and those who either lost their jobs or were job insecure may have suffered the highest levels of HFI. While the COVID-19 pandemic did not create HFI in Canada, many of the subpopulations with high HFI are also some of the most impacted by employment and income loss as a result of the pandemic. HFI is tightly linked to income and reflects the broader material circumstances of households, such as income, assets like property, and other resources that a household could draw upon.1 It seems that HFI was particularly prevalent among workers who were not able to work due to the pandemic business closures.13,24 Between February and April 2020, half of job losses occurred in the bottom earnings quartile, disproportionately affecting the younger, hourly paid, and non-unionized workers.26 Between March and May 2020, nearly half of the residents in the 10 provinces indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic had impacted their ability to meet financial obligations or essential needs.27

Taken together, findings point to the role that financial resources and income play in HFI. Benefit programs, such as the CERB and the Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB), may have offset some of the impact on certain Canadian households. CERB was launched on 6 April 2020 and ran through September 2020, when it was replaced by the CRB for unemployed workers ineligible for EI. The aim of these programs was to provide temporary income to Canadians who faced unemployment due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As most of the data in this review were collected in the early pandemic (April–May 2020), some of the benefits from CERB and other programs may have been missed.

Food banks are another intervention commonly used to address food insecurity in the short term, but data both prior to and during the pandemic show that very few food-insecure households use food banks on a regular basis.13 Two studies13,20 utilizing the CPSS-2 dataset assessed food bank usage during the early pandemic in May 2020. Polsky et al.20 found that only 9.3% of food-insecure households had used a community organization to access free food within the last month. Men and Tarasuk13 reported that only 4.3% of households used food charity more than once in the last month. Given the low usage of food banks, other solutions that target issues of chronic poverty are required, particularly within the context of the pandemic and pandemic recovery periods.

Strengths and limitations

Findings from this review should be interpreted with caution, given a number of limitations. First, there is very limited evidence, as only three peer-reviewed and one non–peer reviewed study were identified. Second, with the exception of the CPSS-2 data, the data were limited to a single province or city, and no study included data from the territories. Third, most studies used convenience samples that favoured populations with higher socioeconomic status. While three studies used weighting methods to approximate the target population, this may provide only part generalizability, as the weighted data were still skewed in some instances. Fourth, most of the evidence is from the early pandemic (April–May 2020), with the exception of the INSPQ data (April 2021), thus we are unable to assess trends over time. Fifth, there is very serious risk of bias related to three of the four studies included. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution, as newly emerging evidence may change the interpretation of the results of this review. Sixth, the measures used to assess HFI differed across the four studies and we were therefore unable to pool data. Seventh, the expedited screening process may have introduced some risk of bias, due to not using two independent reviewers for screening.

Moving forward, we recommend further research on trends in HFI over time from high-quality representative surveys to compare early in the pandemic to later time points. Standardization of HFI measures is also needed to allow comparisons across populations and time. In addition, it will be important to capture other subgroups such as racialized populations, Indigenous people, LGBTQ+ communities, single parents, isolated or remote communities and people living in the territories, all of which have had traditionally higher rates of HFI. Finally, the impact of policy interventions, such as the CERB, is still unknown. Focussed research is required to determine the effect that these types of programs may have had on mitigating HFI.

Conclusion

This research draws attention to the important issue of food insecurity in Canada, especially as it affects vulnerable groups, and it adds to the limited information available that is specific to COVID-19. This review identifies knowledge gaps and can inform actions for HFI, specifically within the Canadian pandemic context. HFI is not a new issue related to the pandemic but a longstanding and prevalent problem that may have been exacerbated by the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted financial resources for many households, especially low-income households, those with young children, and those in tenuous work environments. Loss or reduction in employment due to the pandemic shutdown likely contributed to HFI. Populations most vulnerable to HFI appear to be households with working-age members who lost their employment or were job insecure, and households with children. This is not a departure from prepandemic vulnerable populations; the pandemic has only shone a spotlight on the already affected populations.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Veronica Belcourt and Laura Boland for their help with the GRADE assessments, as well as the Rapid Evidence Service team at the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools, including Emily Belita, Emily Clark, Leah Hagerman, Izabelle Siqueira and Taylor Colangeli.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions and statement

LI, GG and AJG contributed to the conceptualization of the work; LI, GG and TC conducted the data extraction, risk of bias and GRADE assessment; LI and GG jointly drafted the manuscript; VT, LM, SNS, MD, SS, TC and AJG contributed to the interpretation of the data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; all co-authors reviewed, edited and approved the final manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Tarasuk V, Mitchel A, et al. Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF) Toronto(ON): 2020. Household food insecurity in Canada, 2017-18. [Google Scholar]

- Assembly UG, et al. UN General Assembly. (2) Vol. 302. Geneva(CH): 1948. Universal declaration of human rights; pp. 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk V, et al. Health Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2001. Discussion paper on household and individual food insecurity. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/healthy-eating/nutrition-policy-reports/discussion-paper-household-individual-food-insecurity-2001.html. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): The Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/health-nutrition-surveys/canadian-community-health-survey-cchs/household-food-insecurity-canada-overview/household-food-security-survey-module-hfssm-health-nutrition-surveys-health-canada.html. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, McLaren L, McIntyre L, et al. Chronic physical and mental health conditions among adults may increase vulnerability to household food insecurity. J Nutr. 2013;143((11)):1785–93. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.178483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior M, Falissard B, et al, et al. Food insecurity and children’s mental health: a prospective birth cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7((12)):e52615–93. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait CA, Smith PM, Rosella LC, et al. The association between food insecurity and incident type 2 diabetes in Canada: a population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2018:e0195962–93. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessiman-Perreault G, McIntyre L, et al. The household food insecurity gradient and potential reductions in adverse population mental health outcomes in Canadian adults. SSM Popul Health. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead V, onez C, Figueiredo R, Locker D, et al. Oral health disparities and food insecurity in working poor Canadians. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37((4)):294–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Men F, Gundersen C, Urquia ML, Tarasuk V, et al. Association between household food insecurity and mortality in Canada: a population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2020;192((3)):E53–E60. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.190385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk V, Cheng J, Oliveira C, Dachner N, Gundersen C, Kurdyak P, et al. Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. CMAJ. 2015;187((14)):E429–E436. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre L, Bartoo AC, Emery JH, et al. When working is not enough: food insecurity in the Canadian labour force. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17((1)):49–57. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012004053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Men F, Tarasuk V, et al. Food insecurity amid the COVID-19 pandemic: food charity, government assistance, and employment. Can Public Policy. 2021:202–30. doi: 10.3138/cpp.2021-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid review update 2: what is the prevalence of household food insecurity in North America as a result of COVID- 19 and associated public health measures. NCCMT. Available from: https://res.nccmt.ca/res-food-security-EN. [Google Scholar]

- Search strategy for rapid review: what is the prevalence of household food insecurity in North America as a result of COVID-19 and associated public health measures. NCCMT. Available from: https://www.nccmt.ca/uploads/media/media/0001/02/c6c61fee67e1a160fbe73613898e67dc18e6c30b.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Munn Z, et al. Chapter 5: Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence. Chapter 5: Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis [Internet]. Adelaide (Australia): The Joanna Briggs Institute. Available from: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/3283910689/Chapter+5%3A+Systematic+reviews+of+prevalence+and+incidence. [Google Scholar]

- Iorio A, Spencer FA, Falavigna M, et al, et al. Use of GRADE for assessment of evidence about prognosis: rating confidence in estimates of event rates in broad categories of patients. BMJ. 2015:h870–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righy C, Rosa RG, et al, et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in adult critical care survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2019:213–30. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2489-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021:n71–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polsky JY, Gilmour H, et al. Food insecurity and mental health during the COVID- 19 pandemic. Health Rep. 2020;31((12)):3–11. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x202001200001-eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic, May 2020 [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00039-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche B, Brassard D, Lapointe A, et al, et al. Changes in diet quality and food security among adults during the COVID-19–related early lockdown: results from NutriQubec. AM J Clin Nutr. 2021;113((4)):984–92. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll N, Sadowski A, Laila A, et al, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on health behavior, stress, financial and food security among middle to high income Canadian families with young children. Nutrients. 2020;12((8)):2352–92. doi: 10.3390/nu12082352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandmie et inscurit alimentaire - 4 mai 2021 [Internet] Government of Quebec. Available from: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/sondages-attitudes-comportements-quebecois/insecurite-alimentaire-mai-2021. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre L, Dutton DJ, Kwok C, Emery JH, et al. Reduction of food insecurity among low-income Canadian seniors as a likely impact of a guaranteed annual income. Can Pub Policy. 2016;42((3)):274–86. doi: 10.17269/cjph.107.5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux T, Milligan K, Schirle T, Skuterud M, et al. Initial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Canadian labour market. Can Pub Policy. 2020:S55–S65. doi: 10.3138/cpp.2020-049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajacova A, Jehn A, Stackhouse M, et al, et al. Mental health and economic concerns from March to May during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: insights from an analysis of repeated cross-sectional surveys. SSM Popul Health. 2020:100704–S65. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]