Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate histomorphometric outcomes of lateral maxillary sinus augmentation in different areas of the same cavity and to correlate results to bucco‐palatal sinus width (SW) and residual bone height (RBH).

Material and Methods

Patients needing maxillary sinus floor elevation (RBH <5 mm) to insert two nonadjacent implants were treated with lateral augmentation using a composite graft. Six months later, two bone‐core biopsies (mesial/distal) were retrieved in implant insertion sites. SW and RBH were measured on cone beam computed tomography, and correlations between histomorphometric and anatomical parameters were evaluated by multivariate linear regression analysis.

Results

Twenty patients underwent sinus augmentation, and eighteen were included in the final analysis (two dropouts for membrane perforation). Mean newly formed mineralized tissue percentage (%NFMT) after 6 months in mesial and distal sites was 17.5 ± 4.7 and 11.6 ± 4.7, respectively (p = .0004). Multivariate linear regression showed a strong negative correlation between SW and %NFMT (β coefficient=−.774, p < .0001) and no correlation between RBH and %NFMT (β coefficient =−.038, p = .825).

Conclusions

The present study confirms that %NFMT after lateral sinus augmentation occurs at different rates in different anatomical areas of the same maxillary sinus, showing a strong negative correlation with SW, whereas no influence of RBH was observed. Clinicians should regard SW as a guide for graft selection and to decide duration of the healing period. Researchers should consider SW as a predictor variable, when comparing regenerative outcomes of different biomaterials by using maxillary sinus as an experimental model.

Keywords: bone regeneration, bone substitutes, guided tissue regeneration, maxillary sinus, sinus floor elevation

1. INTRODUCTION

Sinus floor elevation with lateral approach, first presented in 1976 by Tatum and then described in literature by Boyne and James (1980), represents a predictable option to increase insufficient available bone height in the edentulous posterior maxilla, in order to allow placement of adequate length implants (Raghoebar et al., 2019). Autologous bone has been the first grafting material used for this procedure, being regarded for a long time as the gold standard for its osteoconductive, osteoinductive and osteogenetic properties. However, even if autologous bone grafts demonstrated significantly higher new bone formation after sinus augmentation if compared with other bone substitutes (Browaeys et al., 2007; Danesh‐Sani et al., 2017), their use is associated with major drawbacks such as increased morbidity, limited availability and low dimensional stability over time (Truedsson et al., 2013). For these reasons, the possible use and behaviour of alternative biomaterials (including allografts, xenografts, alloplastic grafts, composite grafts, platelet concentrates and growth factors) has been widely investigated in this specific clinical application (Batas et al., 2019; Dursun et al., 2016; Galindo‐Moreno et al., 2011; Monje et al., 2017; Stacchi et al., 2017). Evaluation of newly formed tissue quality is conducted by histomorphometric analysis of bone‐core biopsies assessing the percentage of newly formed mineralized tissue (NFMT), residual graft particles (RG), newly formed nonmineralized tissue (NFNMT) and total mineralized tissue (TMT=NFMT+RG) (Moy et al., 1993). Numerous systematic reviews synthesized the available evidence on this topic, failing in demonstrating the superiority of a specific bone substitute in terms of new bone formation after sinus augmentation procedures (Corbella et al., 2016; Danesh‐Sani et al., 2017; Ting et al., 2017; Trimmel et al., 2021).

Extensive neo‐angiogenesis and graft colonization by osteoprogenitor cells are the two essential biological steps for new bone formation after maxillary sinus floor elevation (Carano & Filvaroff, 2003). Following the cascade of inflammatory mediators released after surgical trauma, both the development of new capillary networks from the normal vasculature and the migration of pluripotent mesenchymal cells start mainly from sinus bony walls and floor, with a centripetal proceeding of the entire process (Busenlechner et al., 2009). Schneiderian membrane could also represent an additional source for osteoprogenitor cells and blood supply, but current evidence does not consistently support the real clinical significance of its contribution to new bone formation after sinus augmentation (Dragonas et al., 2020).

These biological activities are influenced by maxillary sinus dimensions. A retrospective radiographic study observed, after one‐stage transcrestal sinus lift, a better intra‐sinus bone coverage of implants inserted in narrow sinuses than in wide ones (Spinato et al., 2015). Histomorphometric analyses demonstrated significantly lower percentages of newly formed bone in wide than in narrow sinus cavities after 6 months of healing, irrespective of the surgical approach (Avila et al., 2010; Lombardi et al., 2017; Soardi et al., 2011; Stacchi et al., 2018). However, large variations in bucco‐palatal width are normally observable within the same sinus cavity, in relation on the area in which measurement is performed: limited bucco‐palatal width is typical of the premolar region (mesial recess), whilst a large, often widely pneumatized cavity is more frequent in the molar region. Therefore, it seems quite difficult to build a meaningful model to classify maxillary sinus cavities into ‘narrow’, ‘medium’ or ‘wide’ (Bertl et al., 2018). Nevertheless, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no investigations have been conducted yet focussing on the healing potential of sites with different bucco‐lingual width within the same maxillary sinus.

Therefore, the aim of this multicentre prospective study was to analyse new bone formation 6 months after lateral sinus floor elevation in different anatomical areas of the maxillary sinus. The null hypothesis of this study is that there were no differences in new bone formation after lateral sinus augmentation in areas of the same maxillary sinus with different bucco‐palatal width.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Study protocol

This study was designed as a multicentre prospective study and was reported following STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) guidelines (von Elm et al., 2007). All procedures were performed in strict accordance with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in Fortaleza (2013) for investigations with human subjects. The study protocol had been approved by the relevant ethical committee (Comitato Etico Calabria‐Sezione Area Nord n. 55/2016) and registered in a public database for clinical trials (NCT04830670). Patients, after being thoroughly informed about the study protocol, the treatment, its alternatives and any potential risk, signed a written informed consent for the participation in the study and authorized the use of their data for research purposes.

2.2. Selection criteria

Any patient with Kennedy class II partial edentulism (Kennedy, 1928), needing unilateral sinus floor elevation for the placement of two nonadjacent dental implants supporting a fixed partial prosthesis, was eligible for entering this study. Patients were consecutively enrolled in this study, provided that they complied with the following inclusion criteria:

Residual bone crest height <5 mm and width ≥6 mm in both sites where implant placement was planned;

Age >18 years;

Written informed consent given.

Patients were excluded from this study if presenting one or more of the following general exclusion criteria:

Absolute medical contraindications to implant surgery (Hwang & Wang, 2006);

Smokers;

Uncontrolled diabetes (HBA1c >7.5%);

Treated or under treatment with intravenous antiresorptive drugs;

Allergy to bovine collagen;

Irradiated in the head and neck area;

Pregnant or breastfeeding;

Substance abusers;

Psychiatric problems or unrealistic expectations;

Patient not fully able to comply with the study protocol.

Local exclusion criteria consisted of the following:

Maxillary sinus conditions contraindicating sinus floor elevation (Pignataro et al., 2008);

Poor oral hygiene and motivation (Full Mouth Plaque Score >20% and or Full Mouth Bleeding Score >10%);

Schneiderian membrane perforation occurred during surgery.

2.3. Presurgical phase

Patients recruited in the present study underwent a careful clinical examination, including assessment of periodontal conditions (probing and periapical radiographs), evaluation of maxillary sinus conditions and analysis of available bone volume in the edentulous areas on cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) and study of occlusal relationships (diagnostic wax‐up). All periodontal patients underwent causal therapy, re‐evaluation and, if necessary, further periodontal treatment before being scheduled for sinus augmentation. A resin surgical template was manufactured by duplicating the diagnostic wax‐up.

All patients received professional deplaquing 1 week prior to surgery and were prescribed with chlorhexidine digluconate 0.2% mouthwash twice a day until the day of surgery.

2.4. Surgical procedure

Antibiotic prophylaxis (2‐g single‐dose amoxicillin) was administered to all patients 1 h before surgery. After performing local anaesthesia (articaine 4% with epinephrine 1:100.000) and elevating a full‐thickness flap, the surgical guide was positioned and an antrostomy was created by consuming the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus with ultrasonic instrumentation in the area between the two planned implant sites (Stacchi et al., 2015). The sinus membrane was then carefully elevated with manual instruments until exposing sinus floor and lateral, medial and anterior sinus walls. After checking manual integrity with visual inspection, the sub‐antral space was filled with a granular composite graft (50%–50% mix of cortico‐cancellous porcine graft [Gen‐Os, Tecnoss] and synthetic nano‐hydroxyapatite [Fisiograft Bone, Ghimas]). A resorbable bovine collagen membrane (Bio‐Gide, Geistlich), fixed with two pins, was placed to cover the lateral antrostomy, and flaps were sutured with Sentineri sutures (Sentineri et al., 2016) and single stitches using synthetic monofilament. Patients were prescribed with antibiotics for 6 days (amoxicillin 1 g two times a day), nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen 600 mg), when needed, and chlorhexidine digluconate 0.2% mouthwash twice a day for 1 week. Patients received specific post‐operative instructions for sinus surgery (e.g. sneeze with mouth open, avoid nose blowing and avoid using straws for drinking). Sutures were removed after 12 days, and patients were recalled at 30‐day intervals to check the course of healing.

After 6 months of healing, CBCT scan was performed to evaluate the radiographic outcome of the regenerative procedure and to plan implant insertion. With the assistance of the same surgical template used in the augmentation surgery, two bone‐core biopsies were harvested in the planned implant sites by using trephine drills with an inner diameter of 3 mm (2982.Y0.30, DenTag) under copious irrigation. Dental implants with moderately rough surface were then inserted in the biopsy sites: after 5 months of submerged healing, they were restored with screwed metal–ceramic prostheses.

2.5. Radiographic measurements

An independent assessor (A.R.) performed radiographic measurements on the three CBCT cross‐sectional slices (step 1 mm; width 1 mm) corresponding to the position where the biopsy was retrieved, and the mean of the three measures was recorded. Measurements were repeated after 1 week with the same protocol, and the mean of the two sessions was considered in the final analysis. The following measurements were performed: (1) residual bone height (RBH) between the alveolar crest and the sinus floor; and (2) sinus width (SW) (distance between buccal and palatal walls at 10‐mm level, comprising the residual alveolar crest, as described by Avila et al., 2010 and Stacchi et al., 2018). Distances were measured in millimetres by using the specific tool of an imaging software (OsiriX MD, Pixmeo SARL). Intra‐class correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to assess intra‐rater repeatability during the two measurement sessions (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979).

2.6. Sample processing for histological analysis

Histological and histomorphometric analyses of all specimens were performed by one of the authors (V.N.), blinded to the study design and to the biopsy origin. Biopsies, left inside the trephine burs to maintain bone‐core orientation, were carefully rinsed with cold 5% glucose solution to remove blood remnants maintaining the correct osmolarity (278 mOsm/L).

Specimens were subsequently fixed for 3 days in 10% buffered formalin solution at pH 7.2 and then dehydrated in an ascending series of alcohol rinses. After 5 days of preinfiltration in a 50% resin/alcohol solution (LR White, London Resin Co. Ltd.), biopsies were removed from trephine burs and sample infiltration was completed with methacrylate resin (Technovit 7200 VLC, Kulzer) (Lebeau et al., 1995).

After 12 days of polymerization, specimens were cut along their longitudinal axis using a high‐precision carborundum disc at 50 µm and then ground down under running water with a series of polishing discs to about 30 ± 10 µm. The slides were then mounted and stained with acid fuchsine–toluidine blue and von Kossa stain.

2.7. Histomorphometry

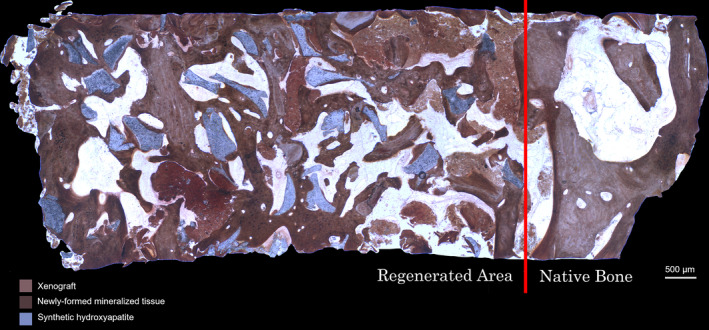

Histomorphometric analysis was performed only on the newly formed tissue: the part of the biopsy including pristine crestal bone was separated from the augmentation area with a manually drawn line (Adobe Photoshop, Adobe) (Figure 1). Analysis was performed using transmitted brightfield light microscope (Biostar B3; Exacta Optech), connected to high‐resolution digital camera (Moticam 5.0; Motic Microscopy). An image processing software (Image‐Pro Plus 6.0; Media Cybernetics Inc.) was used to analyse images. Each biopsy was represented by three histological sections. Three rectangular microscopic fields of 3 mm2 were randomly selected in specific areas of each section: one in the central region of the specimen and two in the periphery. Based on a semi‐automatic segmentation process, the tissue types NFMT, NFNMT and RG were classified and quantified: inaccurately classified areas were manually corrected under visual control. Data were expressed as the percentage of area occupied by the selected tissue type on the total test area, with the final result of each biopsy represented by the average of the three histological slices. The following histomorphometric parameters were measured or calculated: %NFMT (NFMT area per total area; NFMT/TA), %NFNMT (NFNMT area per total area; NFNMT/TA), %RG (RG area per total area; RG/TA) and %TMT (%NFMT+%RG).

FIGURE 1.

Histomorphometric analysis was performed only on the newly formed tissue: the part of the biopsy including pristine crestal bone was separated from the augmentation area with a manually drawn line (von Kossa stain; 30× magnification)

2.8. Predictor and outcome variables

This prospective study tested the null hypothesis of no differences in new bone formation after lateral sinus augmentation in areas of the same maxillary sinus with different bucco‐palatal width against the alternative hypothesis of a difference.

The primary predictor variables were sinus width (SW) and residual bone height (RBH).

Primary outcome measure:

Newly formed mineralized tissue (NFMT) after 6 months of healing.

Secondary outcome measures:

Residual graft (RG) after 6 months of healing;

Newly formed nonmineralized tissue (NFNMT) after 6 months of healing;

Total mineralized tissue (TMT) after 6 months of healing;

Any complications or adverse events.

2.9. Sample size calculation and statistical power

A statistical software (Primer of Biostatistics, Version 6.0, Mc Graw‐Hill) was used to determine the sample size of this prospective study, basing on data reported in a previous publication on histomorphometric outcomes of lateral sinus augmentation correlated with SW (Avila et al., 2010). Expected difference in NFMT (as mean percentage) between narrow and wide part of the augmented sinus was 13.8% ± 18.2%. A sample of 16 histological specimens for each group was required to detect significant differences between the two groups (confidence level 5% with statistical power of 80%).

2.10. Statistical analysis

An independent investigator (A.R.) performed data analysis using a statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0, IBM Corp.). The presence/absence of normal distribution was assessed with Shapiro–Wilk test; all parameters met the required assumptions to apply parametric tests. Descriptive statistics included mean and standard deviation. A p‐value lower than .05 was considered as statistically significant.

Differences in %NFMT, %RG, %NFNMT, %TMT, SW and RBH between mesial and distal sites were evaluated with a two‐tailed paired t‐test. In addition, a multivariate linear regression analysis was performed in order to investigate the independent association between anatomical parameters (SW and RBH) and the primary histomorphometric outcome (%NFMT).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population and clinical results

Twenty consecutive patients (out of 37 examined) were included in this study and underwent unilateral maxillary sinus floor elevation with lateral approach. Surgeries were performed between April 2017 and August 2019 in four Italian private practices (Cassano allo Ionio, Gorizia, Terranegra di Legnago, Treviso) by experienced operators (Fa. Be. n = 3; Fe. Be. n = 4; T.L. n = 6; and C.S. n = 7). Two patients (Fe. Be. n = 1; and T.L. n = 1) dropped out from the study at the time of surgery due to small membrane perforations occurring during elevation with manual instruments (2/20—10%): in both cases, the perforation was sealed with autologous platelet‐rich fibrin membranes and grafting procedure could be successfully completed. Eighteen patients (10 males; 8 females; mean age 59.1 ± 8.2; age range 48–78 years) were included in the final analysis: 36 bone‐core biopsies were harvested and 36 implants were subsequently inserted into the biopsy sites. No intra‐ and post‐operative complications or adverse events were recorded in this study. All implants were functioning with a follow‐up varying from 7 to 31 months after prosthetic loading.

3.2. Radiographic measurements

Residual bone height, as measured on the cross‐sectional images of the biopsy sites, ranged from 2.0 to 4.9 mm (mean 3.4 ± 0.8 mm). RBH in mesial sites ranged from 2.4 to 4.9 mm (mean 3.7 ± 0.7 mm), whilst in distal sites varied from 2.0 to 4.3 mm (mean 3.1 ± 0.7 mm). RBH resulted to be significantly higher in mesial sites than in distal sites (p = .003).

Sinus width in the biopsy sites, measured at 10‐mm level comprising the residual alveolar crest, ranged from 7.3 to 23.4 mm (mean 14.2 ± 4.1 mm). SW in mesial sites ranged from 7.3 to 16.1 mm (mean 11.3 ± 2.4 mm), whilst in distal sites varied from 10.2 to 23.4 mm (mean 17.0 ± 3.4 mm). SW resulted to be significantly higher in distal sites than in mesial sites (p < .0001).

Intra‐class correlation coefficient score for radiographic measurements (>0.96) resulted in an excellent intra‐examiner repeatability: mean difference in RBH and SW was 0.09 and 0.11 mm, respectively.

3.3. Histological and histomorphometric analyses

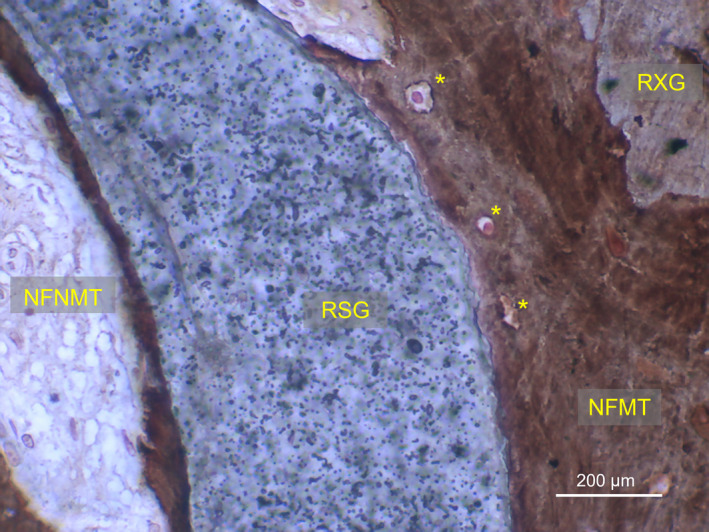

Residual graft particles were still easily recognizable within the regenerated tissue 6 months after surgery, with most of the particles surrounded by newly formed mineralized tissue, merging them with bridges. Numerous osteocytes were detectable within the NFMT section, suggesting the presence of woven bone in active remodelling phase (Hernandez et al., 2004) (Figure 2). The sections of the harvested samples which were examined (newly formed tissue only) had a mean surface of 10.92 ± 2.4 mm2 for the mesial sites and 9.93 ± 3.1 mm2 for the distal sites. The difference between mean biopsy surface in the two groups was not statistically significant (p = .103). After 6 months of healing, cumulative mean %NFMT was 14.6 ± 5.5, %RG was 36.3 ± 12.5 and %NFNMT was 49.2 ± 10.3. Cumulative mean %TMT was 25.4 ± 14.5.

FIGURE 2.

Histological microphotography showing residual graft particles (RXG and RSG) bridged by newly formed mineralized tissue (NFMT) after 6 months of healing. Osteocytes (*) are present within NFMT, suggesting the presence of woven bone in active remodelling phase. RXG, residual xenograft; RSG, residual synthetic graft; NFNMT, newly formed nonmineralized tissue (von Kossa stain; 400× magnification)

Mean %NFMT in mesial and distal sites was 17.5 ± 4.7 and 11.6 ± 4.7, respectively. Mean %NFMT resulted to be significantly higher in mesial than in the distal biopsies (p = .0004). Mean %RG in mesial sites was 35.7 ± 10.8, whist in distal ones was 36.8 ± 14.2, showing no significant differences between the two groups (p = .67). Mean %TMT was 26.6 ± 12.4 and 24.2 ± 16.6 in mesial and distal sites, respectively, with no significant differences between the two groups (p = .11). Mean %NFNMT varied from 46.7 ± 8.6 (mesial sites) to 52.6 ± 11.6 (distal sites), resulting significantly higher in the distal sites (p = .01). Complete histomorphometric outcomes, radiographic measurements and demographics are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographics, anatomical characteristics and histomorphometric outcomes of the entire sample

| Patient | Gender | Age (ys) | Anatomical features (mm) | Histomorphometric outcomes (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW | RBH | NFMT | RG | NFNMT | ||||||||

| Mes | Dis | Mes | Dis | Mes | Dis | Mes | Dis | Mes | Dis | |||

| 1 | F | 55 | 9.7 | 20.4 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 12.5 | 6.9 | 46.6 | 35.7 | 40.9 | 57.4 |

| 2 | M | 69 | 11.4 | 10.2 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 12.6 | 12.9 | 38.8 | 15.7 | 48.6 | 71.4 |

| 3 | M | 53 | 16.1 | 16.4 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 8.2 | 9.2 | 38.0 | 34.7 | 53.8 | 56.1 |

| 4 | F | 54 | 11.7 | 21.3 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 16.8 | 10.5 | 48.8 | 52.4 | 34.4 | 37.0 |

| 5 | M | 49 | 10.4 | 19.1 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 18.6 | 8.5 | 16.4 | 21.1 | 65.0 | 70.4 |

| 6 | M | 64 | 9.2 | 19.2 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 19.8 | 7.6 | 24.8 | 43.2 | 55.4 | 49.2 |

| 7 | M | 56 | 11.4 | 17.2 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 22.2 | 13.1 | 34.7 | 41.1 | 43.1 | 45.8 |

| 8 | F | 57 | 15.8 | 23.4 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 14.6 | 5.3 | 55.0 | 67.3 | 30.4 | 27.4 |

| 9 | M | 78 | 12.1 | 15.7 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 18.6 | 11.3 | 39.6 | 49.3 | 41.8 | 39.4 |

| 10 | M | 66 | 8.4 | 13.8 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 24.4 | 13.1 | 27.7 | 42.1 | 47.9 | 44.8 |

| 11 | F | 63 | 11.4 | 17.9 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 17.8 | 7.9 | 34.8 | 42.3 | 47.4 | 49.8 |

| 12 | M | 64 | 12.3 | 13.9 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 13.7 | 14.1 | 43.3 | 36.7 | 43.0 | 49.2 |

| 13 | F | 71 | 7.3 | 14.4 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 24.4 | 16.1 | 19.1 | 23.6 | 56.5 | 60.3 |

| 14 | F | 54 | 11.3 | 15.0 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 17.5 | 18.6 | 35.6 | 27.6 | 46.9 | 53.8 |

| 15 | F | 56 | 12.3 | 16.6 | 3.9 | 2.4 | 14.4 | 15.6 | 34.3 | 23.3 | 51.3 | 61.1 |

| 16 | M | 48 | 7.8 | 16.3 | 4.9 | 2.3 | 19.3 | 7.9 | 39.6 | 48.3 | 41.1 | 43.8 |

| 17 | M | 51 | 11.6 | 13.7 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 25.6 | 23.2 | 19.3 | 11.6 | 55.1 | 65.2 |

| 18 | F | 54 | 14.1 | 21.5 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 14.6 | 6.6 | 46.8 | 46.5 | 38.6 | 46.9 |

| Total |

8F 10 M |

59.1 ± 8.2 | 11.3 ± 2.4 | 17.0 ± 3.4 | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 17.5 ± 4.7 | 11.6 ± 4.7 | 35.7 ± 10.8 | 36.8 ± 14.2 | 46.7 ± 8.6 | 52.6 ± 11.6 |

Abbreviations: Dis, distal site; F, female; M, male; Mes, mesial site; NFMT, newly formed mineralized tissue; NFNMT, newly formed nonmineralized tissue; RBH, residual bone height; RG, residual graft; SW, sinus width; Ys, years.

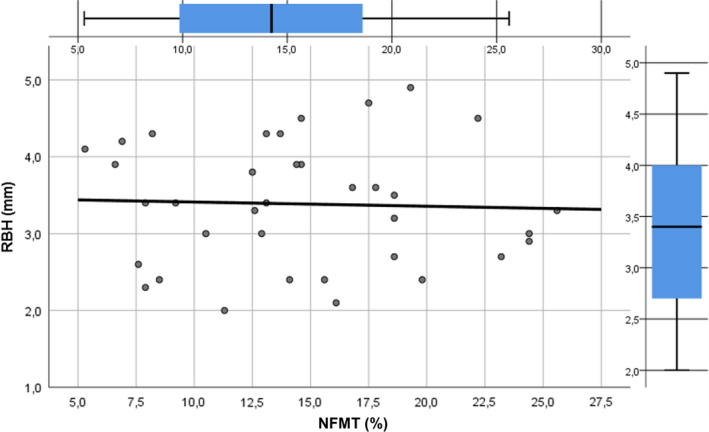

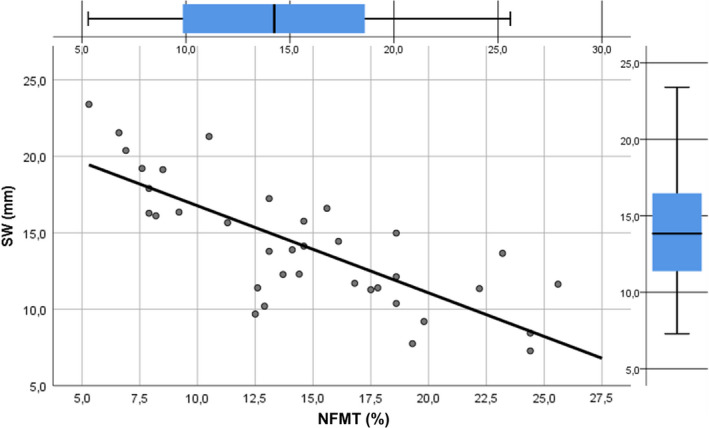

In addition, an indirect significant association between SW (β coefficient =−.774, p < .0001) and %NFMT after 6 months was showed in the multivariate linear regression model, whilst no correlation was demonstrated between RBH and %NFMT (β coefficient =−.038, p = .825) (Figure 4). More detailed results are reported in Table 2 and Figures 3 and 4.

FIGURE 4.

Linear regression line describing the absence of correlation between new bone formation and residual bone height. NFMT, newly formed mineralized tissue; RBH, residual bone height

TABLE 2.

Multivariate linear regression model analyzing the independent association between anatomical parameters (SW and RBH) and the primary histomorphometric outcome (%NFMT)

| Number of biopsies: 36 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory variable | β coefficient | SE | t | Significance | |

| Model: Outcome NFMT (%) 2 = .587 | |||||

| SW | −0.774 | 0.001 | −7.131 | p < .001 | S |

| RBH | −0.038 | 0.012 | −0.223 | p = .825 | NS |

Abbreviations: NFMT, newly formed mineralized tissue; NS, not significant; p, p‐value; RBH, residual bone height; S, significant; SE, standardized error of the β coefficient; SW, sinus width; t, t‐value.

FIGURE 3.

Linear regression line describing the strong negative correlation between new bone formation and sinus width. NFMT, newly formed mineralized tissue; SW, sinus width

4. DISCUSSION

The influence of anatomical, biological and surgical features on new bone regeneration after maxillary sinus floor elevation has been widely investigated. Prompt availability of mesenchymal osteoprogenitor cells and fast development of new blood vessels network are the two key factors for osseous repair (Hankenson et al., 2011; Scala et al., 2010). In the maxillary sinus, both components mainly originate from bony walls and floor; then, new bone formation starts from the periphery and progresses towards the grafted area with a centripetal pattern (Busenlechner et al., 2009). This entails that narrow sinuses could represent a more favourable biological environment for bone regeneration if compared with wide cavities: histological human studies conducted on lateral (Avila et al., 2010; Soardi et al., 2011) and transcrestal approach (Lombardi et al., 2017; Stacchi et al., 2018) confirmed this hypothesis, reporting significantly higher percentages of newly formed bone after 6 months of healing in narrow than in wide sinuses. It is still unclear if graft consolidation occurs also in wide cavities after a longer period of time or if a large sinus represents a sort of critical‐sized defect, in which bone regeneration will never adequately complete. Moreover, the irregular morphology and the high‐dimensional variability of maxillary sinus among different individuals do not permit to classify the entire sinus cavity as narrow or wide, but each single future implant site presents specific anatomical characteristics influencing biological response (Bertl et al., 2018; Uthman et al., 2011). It should be also considered that mesial sites could benefit from an additional osteogenic source represented by the anterior sinus wall which, in this investigation, was always exposed and put in contact with the graft.

The present study analysed regenerative outcomes in mesial and distal sites within the same maxillary sinus: unsurprisingly, sinus cavity width in distal sites (mean 17.0 ± 3.4 mm) resulted significantly wider than in mesial sites (mean 11.3 ± 2.4 mm). Histomorphometric analysis showed that mean %NFMT in biopsies taken after 6 months of healing in mesial sites (17.5 ± 4.7) was significantly higher than mean %NFMT in distal sites (11.6 ± 4.7), in accordance with a recent clinical study (Reich et al., 2016). Mean cumulative %NFMT was 14.6 ± 5.5, a relatively low value if compared with mean %NFMT usually reported in literature after maxillary sinus floor elevation: Corbella et al. (2016), in their meta‐analysis, reported %NFMT ranging from 31.4 to 43.9 six months after sinus augmentation with porcine bone alone. However, data from the present analysis are consistent with other studies evaluating xenogeneic and/or synthetic grafts behaviour in lateral sinus lift, in which histomorphometric analysis was limited to the augmented area without the inclusion of pristine crestal bone (%NFMT ranging from 10.4 to 19) (Payer et al., 2014; Wildburger et al., 2014; Zerbo et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2012).

Sinus bucco‐palatal width (SW) and %NFMT showed a strong negative correlation, in agreement with numerous previous studies (Avila et al., 2010; Kolerman et al., 2008; Lombardi et al., 2017; Soardi et al., 2011; Stacchi et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2021) but in disagreement with a recent article (Pignaton et al., 2019). This difference could be explained by methodological differences between the two studies (grafting material, healing time and method for clustering sinus width) and possible patient‐related variables (which are absent in the present study, as mesial and distal biopsies were harvested from the same sinus).

Our findings indirectly confirmed a very recent investigation evaluating the vertical gradient of bone graft consolidation in biopsies harvested 6 months after lateral sinus augmentation (Beck et al., 2021). This latter study showed that %NFMT gradually decreases from sinus floor towards the apical part of the augmentation area: this negative gradient was moderate in the premolar area and steeper in the molar area. It could be reasonably hypothesized that in the premolar area, where the sinus cavity is narrower (mesial recess), the osteogenic contribution of lateral and palatal bony walls was more significant than in the molar area, where the sinus is wider.

In the present study, biopsies were taken mesially and distally to the area where the antrostomy was designed during surgery, as the bony window removal could play a negative influence on remodelling and consolidation of the graft into new bone (Artzi et al., 2005; Avila‐Ortiz, Wang, et al., 2012).

The strong negative correlation between SW and %NFMT carries important clinical and research implications. Clinicians should tailor grafting material selection (solely osteoconductive vs. osteoconductive/osteoinductive) and duration of healing period basing both on patient‐dependent factors (e.g. systemic conditions, age and dental status) and on the worst scenario in terms of SW among the planned implant sites within the same augmented sinus (Velasco‐Torres et al., 2017). On their part, researchers should always record SW in the biopsy retrieval site when performing histomorphometric evaluations and insert it as a predictor variable in the statistical models. This variable started to be considered very recently in clinical research (Galindo‐Moreno et al., 2020; Pignaton et al., 2019; Stacchi et al., 2018; Taschieri et al., 2020): the great majority of the histological studies comparing the performance of different grafting materials by using the maxillary sinus as experimental model did not evaluate this parameter, possibly introducing a major bias in the interpretation of results. In a very recent Bayesian network meta‐analysis on the histomorphometric outcomes from randomized clinical trials with different biomaterials used for maxillary sinus augmentation (Trimmel et al., 2021), only one trial (out of 34 included) reported and analysed SW in biopsy sites (Flichy‐Fernández et al., 2019).

No correlation was demonstrated between RBH and %NFMT: this outcome is consistent with many other studies demonstrating that graft remodelling into new bone was not significantly influenced by residual alveolar bone height (Avila et al., 2010; Avila‐Ortiz, Neiva, et al., 2012; Pesce et al., 2021; Pignaton et al., 2019; Stacchi et al., 2018; Taschieri et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021). From these findings, RBH should not be considered as a possible indicator of the regenerative potential of the site to be augmented, but only as a predictive factor for immediate implant placement (Stacchi et al., 2020). Different results were reported by Reich et al. (2016), who observed a direct correlation between RBH and %NFMT. In this study, however, anatomical region and not bucco‐palatal sinus width was included among the predictor variables of multiple regression model, possibly confounding the final outcomes.

Based on the results of the present study, new bone formation after maxillary sinus floor elevation is influenced by the bucco‐palatal width of different areas of the sinus cavity; then, the null hypothesis of the study can be rejected. However, some limitations have to be considered: the main one consists in the selection of a single time point for biopsies collection (6 months after surgery), which does not give information about possible further graft consolidation in longer healing periods, as showed in other studies (Soardi et al., 2011). Moreover, as this study was conducted by using only one composite graft, these results cannot be automatically extended to other bone substitutes: further histological studies conducted on a broader population are necessary to confirm and generalize the present outcomes.

5. CONCLUSION

The present study confirms that %NFMT 6 months after lateral sinus floor elevation occurs at different rates in different anatomical areas of the same maxillary sinus, showing a strong negative correlation with SW, whereas no influence of RBH was observed. Clinicians should evaluate SW in the planned implant site to optimize grafting material selection and to calibrate the duration of the healing period. Researchers should regard SW as a fundamental predictor variable, when comparing histomorphometric outcomes of different biomaterials by using maxillary sinus as an experimental model.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors do not have any financial interests, either directly or indirectly, in the products or information listed in this paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Claudio Stacchi: Conceptualization (lead); Data curation (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (lead); Supervision (lead); Writing – original draft (lead); Writing – review & editing (equal). Antonio Rapani: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (lead); Methodology (equal); Software (lead); Validation (lead); Writing – review & editing (equal). Teresa Lombardi: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Investigation (equal); Visualization (lead); Writing – review & editing (equal). Fabio Bernardello: Data curation (equal); Investigation (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Vanessa Nicolin: Investigation (equal); Project administration (lead); Resources (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Federico Berton: Data curation (equal); Investigation (lead); Methodology (equal); Software (equal); Validation (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal).

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study protocol had been approved by the relevant ethical committee (Comitato Etico Calabria‐Sezione Area Nord n. 55/2016).

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

This study was registered in a public database for clinical trials (NCT04830670).

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Patients, after being thoroughly informed about the study protocol, the treatment, its alternatives and any potential risk, signed a written informed consent for the participation in the study and authorized the use of their data for research purposes.

Supporting information

App S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Giovanna Baldini and Roberta Bortul (Bone Lab—University of Trieste) for their precious help in the histological analysis. Open Access Funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Trieste within the CRUI‐CARE Agreement. [Correction added on 19 May 2022, after first online publication: CRUI funding statement has been added.]

Stacchi, C. , Rapani, A. , Lombardi, T. , Bernardello, F. , Nicolin, V. , & Berton, F. (2022). Does new bone formation vary in different sites within the same maxillary sinus after lateral augmentation? A prospective histomorphometric study. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 33, 322–332. 10.1111/clr.13891

Funding information

The present study was self‐funded.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data supporting the findings of the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Artzi, Z. , Kozlovsky, A. , Nemcovsky, C. E. , & Weinreb, M. (2005). The amount of newly formed bone in sinus grafting procedures depends on tissue depth as well as the type and residual amount of the grafted material. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 32, 193–199. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00656.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila, G. , Wang, H. L. , Galindo‐Moreno, P. , Misch, C. E. , Bagramian, R. A. , Rudek, I. , Benavides, E. , Moreno‐Riestra, I. , Braun, T. , & Neiva, R. (2010). The influence of the bucco‐palatal distance on sinus augmentation outcomes. Journal of Periodontology, 81, 1041–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila‐Ortiz, G. , Neiva, R. , Galindo‐Moreno, P. , Rudek, I. , Benavides, E. , & Wang, H. L. (2012). Analysis of the influence of residual alveolar bone height on sinus augmentation outcomes. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 23, 1082–1088. 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila‐Ortiz, G. , Wang, H. L. , Galindo‐Moreno, P. , Misch, C. E. , Rudek, I. , & Neiva, R. (2012). Influence of lateral window dimensions on vital bone formation following maxillary sinus augmentation. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Implants, 27, 1230–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batas, L. , Tsalikis, L. , & Stavropoulos, A. (2019). PRGF as adjunct to DBB in maxillary sinus floor augmentation: Histological results of a pilot split‐mouth study. International Journal of Implant Dentistry, 5, 14. 10.1186/s40729-019-0166-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, F. , Reich, K. M. , Lettner, S. , Heimel, P. , Tangl, S. , Redl, H. , & Ulm, C. (2021). The vertical course of bone regeneration in maxillary sinus floor augmentations: A histomorphometric analysis of human biopsies. Journal of Periodontology, 92, 263–272. 10.1002/JPER.19-0656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertl, K. , Mick, R. B. , Heimel, P. , Gahleitner, A. , Stavropoulos, A. , & Ulm, C. (2018). Variation in bucco‐palatal maxillary sinus width does not permit a meaningful sinus classification. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 29, 1220–1229. 10.1111/clr.13387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyne, P. J. , & James, R. A. (1980). Grafting of the maxillary sinus floor with autogenous marrow and bone. Journal of Oral Surgery, 38, 613–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browaeys, H. , Bouvry, P. , & De Bruyn, H. (2007). A literature review on biomaterials in sinus augmentation procedures. Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research, 9, 166–177. 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2007.00050.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busenlechner, D. , Huber, C. D. , Vasak, C. , Dobsak, A. , Gruber, R. , & Watzek, G. (2009). Sinus augmentation analysis revised: The gradient of graft consolidation. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 20, 1078–1083. 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carano, R. A. , & Filvaroff, E. H. (2003). Angiogenesis and bone repair. Drug Discovery Today, 8, 980–989. 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02866-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbella, S. , Taschieri, S. , Weinstein, R. , & Del Fabbro, M. (2016). Histomorphometric outcomes after lateral sinus floor elevation procedure: A systematic review of the literature and meta‐analysis. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 27, 1106–1122. 10.1111/clr.12702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesh‐Sani, S. A. , Engebretson, S. P. , & Janal, M. N. (2017). Histomorphometric results of different grafting materials and effect of healing time on bone maturation after sinus floor augmentation: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Periodontal Research, 52, 301–312. 10.1111/jre.12402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragonas, P. , Katsaros, T. , Schiavo, J. , Galindo‐Moreno, P. , & Avila‐Ortiz, G. (2020). Osteogenic capacity of the sinus membrane following maxillary sinus augmentation procedures: A systematic review. International Journal of Oral Implantology (Berlin), 13, 213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dursun, C. K. , Dursun, E. , Eratalay, K. , Orhan, K. , Tatar, I. , Baris, E. , & Tözüm, T. F. (2016). Effect of porous titanium granules on bone regeneration and primary stability in maxillary sinus: A human clinical, histomorphometric, and microcomputed tomography analyses. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 27, 391–397. 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flichy‐Fernández, A. J. , Blaya‐Tárraga, J. A. , O'Valle, F. , Padial‐Molina, M. , Peñarrocha‐Diago, M. , & Galindo‐Moreno, P. (2019). Sinus floor elevation using particulate PLGA‐coated biphasic calcium phosphate bone graft substitutes: A prospective histological and radiological study. Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research, 21, 895–902. 10.1111/cid.12741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo‐Moreno, P. , Moreno‐Riestra, I. , Avila, G. , Padial‐Molina, M. , Paya, J. A. , Wang, H.‐L. , & O'Valle, F. (2011). Effect of anorganic bovine bone to autogenous cortical bone ratio upon bone remodeling patterns following maxillary sinus augmentation. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 22, 857–864. 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.02073.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo‐Moreno, P. , Padial‐Molina, M. , Lopez‐Chaichio, L. , Gutiérrez‐Garrido, L. , Martín‐Morales, N. , & O'Valle, F. (2020). Algae‐derived hydroxyapatite behavior as bone biomaterial in comparison with anorganic bovine bone: A split‐mouth clinical, radiological, and histologic randomized study in humans. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 31, 536–548. 10.1111/clr.13590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankenson, K. D. , Dishowitz, M. , Gray, C. , & Schenker, M. (2011). Angiogenesis in bone regeneration. Injury, 42, 556–561. 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, C. J. , Majeska, R. J. , & Schaffler, M. B. (2004). Osteocyte density in woven bone. Bone, 35, 1095–1099. 10.1016/j.bone.2004.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, D. , & Wang, H. L. (2006). Medical contraindications to implant therapy. Part I: Absolute contraindications. Implant Dentistry, 15, 353–360. 10.1097/01.id.0000247855.75691.03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, E. (1928). Partial denture construction. Dental Items of Interest, 1, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kolerman, R. , Tal, H. , & Moses, O. (2008). Histomorphometric analysis of newly formed bone after maxillary sinus floor augmentation using ground cortical bone allograft and internal collagen membrane. Journal of Periodontology, 79, 2104–2111. 10.1902/jop.2008.080117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebeau, A. , Muthmann, H. , Sendelhofert, A. , Diebold, J. , & Löhrs, U. (1995). Histochemistry and immunohistochemistry on bone marrow biopsies: A rapid procedure for methyl methacrylate pathology. Research and Practice, 191, 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, T. , Stacchi, C. , Berton, F. , Traini, T. , Torelli, L. , & Di Lenarda, R. (2017). Influence of maxillary sinus width on new bone formation after transcrestal sinus floor elevation: A proof‐of‐concept prospective cohort study. Implant Dentistry, 26, 209–216. 10.1097/ID.0000000000000554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monje, A. , O'Valle, F. , Monje‐Gil, F. , Ortega‐Oller, I. , Mesa, F. , Wang, H. L. , & Galindo‐Moreno, P. (2017). Cellular, vascular, and histomorphometric outcomes of solvent‐dehydrated vs freeze‐dried allogeneic graft for maxillary sinus augmentation: A randomized case series. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Implants, 32, 121–127. 10.11607/jomi.4801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy, P. K. , Lundgren, S. , & Holmes, R. E. (1993). Maxillary sinus augmentation: Histomorphometric analysis of graft materials for maxillary sinus floor augmentation. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 51, 857–862. 10.1016/S0278-2391(10)80103-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payer, M. , Lohberger, B. , Strunk, D. , Reich, K. M. , Acham, S. , & Jakse, N. (2014). Effects of directly autotransplanted tibial bone marrow aspirates on bone regeneration and osseointegration of dental implants. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 25, 468–474. 10.1111/clr.12172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesce, P. , Menini, M. , Canullo, L. , Khijmatgar, S. , Modenese, L. , Gallifante, G. , & Del Fabbro, M. (2021). Radiographic and histomorphometric evaluation of biomaterials used for lateral sinus augmentation: A systematic review on the effect of residual bone height and vertical graft size on new bone formation and graft shrinkage. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10, 4996. 10.3390/jcm10214996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignataro, L. , Mantovani, M. , Torretta, S. , Felisati, G. , & Sambataro, G. (2008). ENT assessment in the integrated management of candidate for maxillary sinus lift. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica, 28, 110–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignaton, T. B. , Wenzel, A. , Ferreira, C. E. A. , Borges Martinelli, C. , Oliveira, G. J. P. L. , Marcantonio, E. Jr , & Spin‐Neto, R. (2019). Influence of residual bone height and sinus width on the outcome of maxillary sinus bone augmentation using anorganic bovine bone. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 30, 315–323. 10.1111/clr.13417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghoebar, G. M. , Onclin, P. , Boven, G. C. , Vissink, A. , & Meijer, H. J. A. (2019). Long‐term effectiveness of maxillary sinus floor augmentation: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 46, 307–318. 10.1111/jcpe.13055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich, K. M. , Huber, C. D. , Heimel, P. , Ulm, C. , Redl, H. , & Tangl, S. (2016). A quantification of regenerated bone tissue in human sinus biopsies: Influences of anatomical region, age and sex. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 27, 583–590. 10.1111/clr.12627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scala, A. , Botticelli, D. , Rangel, I. G. Jr , de Oliveira, J. A. , Okamoto, R. , & Lang, N. P. (2010). Early healing after elevation of the maxillary sinus floor applying a lateral access: A histological study in monkeys. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 21, 1320–1326. 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.01964.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentineri, R. , Lombardi, T. , Berton, F. , & Stacchi, C. (2016). Laurell‐Gottlow suture modified by Sentineri for tight closure of a wound with a single line of sutures. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 54, e18–e19. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P. E. , & Fleiss, J. L. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 86, 420–428. 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soardi, C. M. , Spinato, S. , Zaffe, D. , & Wang, H. L. (2011). Atrophic maxillary floor augmentation by mineralized human bone allograft in sinuses of different size: An histologic and histomorphometric analysis. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 22, 560–566. 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.02034.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinato, S. , Bernardello, F. , Galindo‐Moreno, P. , & Zaffe, D. (2015). Maxillary sinus augmentation by crestal access: A retrospective study on cavity size and outcome correlation. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 26, 1375–1382. 10.1111/clr.12477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacchi, C. , Lombardi, T. , Oreglia, F. , Alberghini Maltoni, A. , & Traini, T. (2017). Histologic and histomorphometric comparison between sintered nano‐hydroxyapatite and anorganic bovine xenograft in maxillary sinus grafting: A split‐mouth randomized controlled clinical trial. BioMed Research International, 2017, 9489825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacchi, C. , Lombardi, T. , Ottonelli, R. , Berton, F. , Perinetti, G. , & Traini, T. (2018). New bone formation after transcrestal sinus floor elevation was influenced by sinus cavity dimensions: A prospective histologic and histomorphometric study. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 29, 465–479. 10.1111/clr.13144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacchi, C. , Spinato, S. , Lombardi, T. , Bernardello, F. , Bertoldi, C. , Zaffe, D. , & Nevins, M. (2020). Minimally invasive management of implant‐supported rehabilitation in the posterior maxilla, Part II. Surgical techniques and decision tree. International Journal of Periodontics and Restorative Dentistry, 40, e95–e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacchi, C. , Vercellotti, T. , Toschetti, A. , Speroni, S. , Salgarello, S. , & Di Lenarda, R. (2015). Intraoperative complications during sinus floor elevation using two different ultrasonic approaches: A two‐center, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research, 17, e117–e125. 10.1111/cid.12136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taschieri, S. , Ofer, M. , Corbella, S. , Testori, T. , Dellavia, C. , Nemcovsky, C. , Canciani, E. , Francetti, L. , Del Fabbro, M. , & Tartaglia, G. (2020). The influence of residual alveolar bone height on graft composition after maxillary sinus augmentation using two different xenografts: A histomorphometric comparative study. Materials, 13, 5093. 10.3390/ma13225093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum, O. H. (1976). Maxillary sinus grafting for endoosseous implants. Lecture presented at the Annual Meeting of the Alabama Implant Study Group. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, M. , Rice, J. G. , Braid, S. M. , Lee, C. Y. S. , & Suzuki, J. B. (2017). Maxillary sinus augmentation for dental implant rehabilitation of the edentulous ridge: A comprehensive overview of systematic reviews. Implant Dentistry, 26, 438–464. 10.1097/ID.0000000000000606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimmel, B. , Gede, N. , Hegyi, P. , Szakács, Z. , Mezey, G. A. , Varga, E. , Kivovics, M. , Hanák, L. , Rumbus, Z. , & Szabó, G. (2021). Relative performance of various biomaterials used for maxillary sinus augmentation: A Bayesian network meta‐analysis. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 32, 135–153. 10.1111/clr.13690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truedsson, A. , Hjalte, K. , Sunzel, B. , & Warfvinge, G. (2013). Maxillary sinus augmentation with iliac autograft ‐ a health‐economic analysis. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 24, 1088–1093. 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2012.02515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthman, A. T. , Al‐Rawi, N. H. , Al‐Naaimi, A. S. , & Al‐Timimi, J. F. (2011). Evaluation of maxillary sinus dimensions in gender determination using helical CT scanning. Journal of Forensic Science, 56, 403–408. 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2010.01642.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco‐Torres, M. , Padial‐Molina, M. , Avila‐Ortiz, G. , García‐Delgado, R. , O'Valle, F. , Catena, A. , & Galindo‐Moreno, P. (2017). Maxillary sinus dimensions decrease as age and tooth loss increase. Implant Dentistry, 26, 288–295. 10.1097/ID.0000000000000551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E. , Altman, D. G. , Egger, M. , Pocock, S. J. , Gøtzsche, P. C. , Vandenbroucke, J. P. , & Initiative, S. T. R. O. B. E. (2007). The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology, 18, 800–804. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildburger, A. , Payer, M. , Jakse, N. , Strunk, D. , Etchard‐Liechtenstein, N. , & Sauerbier, S. (2014). Impact of autogenous concentrated bone marrow aspirate on bone regeneration after sinus floor augmentation with a bovine bone substitute–a split‐mouth pilot study. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 25, 1175–1181. 10.1111/clr.12228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbo, I. R. , Zijderveld, S. A. , de Boer, A. , Bronckers, A. L. J. J. , de Lange, G. , ten Bruggenkate, C. M. , & Burger, E. H. (2004). Histomorphometry of human sinus floor augmentation using a porous beta‐tricalcium phosphate: A prospective study. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 15, 724–732. 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.01055.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Tangl, S. , Huber, C. D. , Lin, Y. , Qiu, L. , & Rausch‐Fan, X. (2012). Effects of Choukroun's platelet‐rich fibrin on bone regeneration in combination with deproteinized bovine bone mineral in maxillary sinus augmentation: A histological and histomorphometric study. Journal of Cranio‐Maxillofacial Surgery, 40, 321–328. 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W. , Wang, F. , Magic, M. , Zhuang, M. , Sun, J. , & Wu, Y. (2021). The effect of anatomy on osteogenesis after maxillary sinus floor augmentation: A radiographic and histological analysis. Clinical Oral Investigations, 25, 5197–5204. 10.1007/s00784-021-03827-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

App S1

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.