Abstract

Aim

To develop and psychometrically test an occupational violence (OV) risk assessment tool in the emergency department (ED).

Design

Three studies were conducted in phases: content validity, predictive validity and inter‐rater reliability from June 2019 to March 2021.

Methods

For content validity, ED end users (mainly nurses) were recruited to rate items that would appropriately assess for OV risk. Subsequently, a risk assessment tool was developed and tested for its predictive validity and inter‐rater reliability. For predictive validity, triage notes of ED presentations in a month with the highest OV were assessed for presence of OV risk. Each presentation was then matched with events recorded in the OV incident register. Sensitivity and specificity values were calculated. For inter‐rater reliability, two assessors—trained and untrained—independently assessed the triage notes for presence of OV risk. Cohen's kappa was calculated.

Results

Two rounds of content validity with a total of N = 81 end users led to the development of a three‐domain tool that assesses for OV risk using aggression history, behavioural concerns (i.e., angry, clenched fist, demanding, threatening language or resisting care) and clinical presentation concerns (i.e., alcohol/drug intoxication and erratic cognition). Recommended risk ratings are low (score = 0 risk domain present), moderate (score = 1 risk domain present) and high (score = 2–3 risk domains present), with an area under the curve of 0.77 (95% confidence interval 0.7–0.81, p < .01). Moderate risk rating had a 61% sensitivity and 91% specificity, whereas high risk rating had 37% sensitivity and 97% specificity. Inter‐rater reliability ranged from 0.67 to 0.75 (p < .01), suggesting moderate agreement.

Conclusions

The novel three‐domain OV risk assessment tool was shown to be appropriate and relevant for application in EDs. The tool, developed through a rigorous content validity process, demonstrates acceptable predictive validity and inter‐rater reliability.

Impact

The developed tool is currently piloted in a single hospital ED, with a view to extend to inpatient settings and other hospitals.

Keywords: emergency nursing, instrument development, psychometrics, risk assessment, risk factors, workplace violence

What problem did the study address?

Risk assessment tools can facilitate early identification of, and intervention for, occupational violence (OV) risk in emergency departments (EDs).

Clinical utility of an OV assessment tool hinges on three key important attributes—comprehensive, brief and objective; but no current tool meets the three key important attributes.

What were the main findings?

A novel three‐domain OV risk assessment tool was developed for use in EDs that prompts review of the patient's aggression history, behaviours and clinical presentation.

The tool demonstrated acceptable predictive validity by triggering risk stratification: low (score = 0), moderate (score = 1) and high (score = 2–3), with an AUC of 0.77 (95% confidence interval 0.7–0.81).

Tool trials by a trained and untrained assessor showed moderate agreement.

Where and whom will the research have an impact?

The three‐domain OV risk assessment tool can be used in EDs and may be transferrable to inpatient settings.

The tool is currently being trialled in a public metropolitan ED with a high prevalence of OV.

1. INTRODUCTION

Patient‐related occupational violence (OV) risks in emergency departments (EDs) should be assessed comprehensively, briefly and objectively using patient history, presenting behaviours and the characteristics of their presentation. However, there are no tool/s that meet these requirements. Therefore, the aim of this study is to develop and psychometrically test an OV risk assessment tool in the ED.

2. BACKGROUND

OV is universally defined as ‘any physical attack or verbal abuse that occurs in the workplace or is associated with the workplace that could potentially lead to physical and/or psychological harm’ (Cabilan & Johnston, 2019, p. 732). It is pervasive in EDs worldwide, with an increasing incidence (Nikathil et al., 2018) and a reported staff prevalence as high as 90% (Nikathil et al., 2017).

In EDs, OV is worse than in any other hospital settings (Hahn et al., 2013); however, it is impactful to the overall health system. For patients, incidents and the way they are managed can be disengaging, dehumanizing (Wong et al., 2020) and distressing (Akther et al., 2019). Staff who are subjected to such violence report significant physical, psychological and emotional harms after violent events (Lanctôt & Guay, 2014). For health services, there are costs associated with staff sick leave, compensation claims (Speroni et al., 2014) and, potentially, replacement of skilled staff who are unable or unwilling to work after events. Prevention should therefore be prioritized to limit the incidence and mitigate the detrimental impacts of OV (D'Ettorre et al., 2018; Morphet et al., 2018).

Focussing in the ED literature, prevention‐focussed interventions are those that are aimed at preventing OV incidents from occurring (Cabilan et al., 2021). Recognition of the value of patient risk assessment as a tool for OV prevention is growing. For example, ED nurses believe that OV‐specific patient risk assessment could provide them with the opportunity to pre‐emptively identify patients who could perpetrate violence enabling staff to undertake appropriate precautions and instigate early interventions (Cabilan et al., 2020). Indeed, several studies exploring the impact of risk assessment affirm that a routine patient risk assessment could reduce OV incidents, negate the need for coercive restraints and/or limit detrimental impacts of OV in EDs (Daniel, 2015; Kling et al., 2011; Senz et al., 2020; Sharifi et al., 2020).

ED nurses are well positioned to initiate OV risk assessment because they have good patient visibility due to the broad scope of direct patient care they undertake, such as triaging, regular assessment and monitoring, medication administration, communication, transportation and education (Cole et al., 2016). They are present at every stage of the patient's journey from admission to discharge. Generally, ED nurses have a positive attitude towards risk assessment (Cabilan et al., 2020; Daniel et al., 2015), but their adherence to and perceived utility of risk assessment tools hinge on their compatibility with existing clinical processes (Viljoen et al., 2018). For example, in one study (Daniel et al., 2015), the implementation of violence risk assessment through direct questioning at triage was unsuccessful because it was incompatible with the usual nursing processes. Further, the length of OV risk assessment tools validated for inpatients might also preclude their use in fast‐paced or time‐constrained EDs (Levin et al., 2016).

A scoping literature review of OV risk assessment tools that can be used in EDs revealed pertinent information that could guide the development of a desirable risk assessment tool (Cabilan & Johnston, 2019). First, OV risks fall into three key domains: patient history, behaviours and characteristics of clinical presentation. Second, while there are prompting or validated tools exploring risks of patient violence in existence, they do not specifically address these important domains. Lastly, when nurses were questioned about essential tool attributes, they believed that for an OV risk assessment tool to be clinically useful it must be comprehensive, brief (i.e., three to five items) and objective (Cabilan et al., 2020). Aligning these attributes against the available risk assessment tools in the ED (Daniel, 2015; Luck et al., 2007; Partridge & Affleck, 2018; Sands, 2007; Wilkes et al., 2010) reveals a dissonance between ED end user needs and tool utility. Unless an OV risk assessment tool meets the needs of the ED staff, it is unlikely to be adopted in practice. Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop and psychometrically test an OV risk assessment tool in the ED, with a view to extend to inpatient settings. A novel tool that can be initiated in the ED and adaptable to the inpatient setting presents an opportunity to have a standard OV risk assessment tool. When this is achieved, the benefits afforded by risk assessments—such as mitigation of OV incidents, coercive restraints and negative impacts of OV (Daniel, 2015; Kling et al., 2011; Senz et al., 2020; Sharifi et al., 2020)—could be impactful and consistent.

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Aim

This study aimed to develop and psychometrically test an OV risk assessment tool in the ED.

4. METHODOLOGY

4.1. Study design

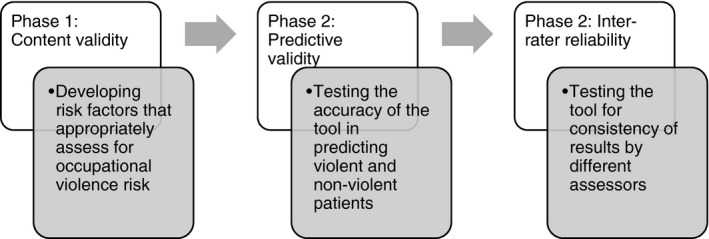

This mixed methods study consisted of three phases: content validity, predictive validity and inter‐rater reliability (see Figure 1), undertaken from June 2019 to March 2021. Content validity (Phase 1) ensures that the tool can appropriately measure OV risk. Predictive validity (Phase 2) is not only important in accurately predicting violent events but also crucial in decisions relating to the subsequent management of patients. Predictive validity measures how accurately the tool can predict those who will be violent (sensitivity) and will not be violent (specificity; DeVon et al., 2007). Without predictive validity, there is the risk of implementing a tool that could lead to false negatives, therefore, underestimation and risk of harm, or false positives that could lead to overestimation and misapplication of resources (Large & Nielssen, 2011). An effective tool can be applied by a multitude of users with varying clinical experiences. Examining inter‐rater reliability (Phase 3) establishes whether the tool yields the same results when applied by different users.

FIGURE 1.

Visual overview of the study designs used to establish validity and reliability of the new occupational violence patient risk assessment tool

4.2. Setting

The primary study ED is a public, metropolitan, adult tertiary referral hospital in Brisbane, Australia. It has over 61,000 presentations annually, with clinical areas: resuscitation area, acute care area, short‐stay unit, ambulatory care, procedure rooms and a mental health unit. Patients' health records are fully digital—from tracking, documentation, test ordering and results, and prescribing. Based on an internal survey in 2017, 98% of nurses self‐reported being exposed to verbal or physical OV from patients. This provided the impetus for the ED leadership team to focus on OV and undertake comprehensive internal audits of OV incidences.

4.3. Sampling and data analysis

4.3.1. Phase 1: Content validity

Tool items were generated deductively from a previous systematic scoping review (Cabilan & Johnston, 2019), yielding a total list of 34 possible risk items for OV (Table 1) spanning three risk domains—patient history, behaviours and clinical presentation. These risk items and the associated domains were forwarded to end users for relevance rating, as part of a questionnaire, to help direct tool development.

TABLE 1.

Round 1 item‐level content validity indices (I‐CVI) of 34 risk items of occupational violence in the emergency department grouped under the domains of history, behaviours and clinical presentation

| n | I‐CVI | |

|---|---|---|

| History (N = 7 end users) | ||

| Criminal history | 2 | 0.29 |

| Frequent presentations | 2 | 0.29 |

| Involuntary admission | 4 | 0.57 |

| Mental illness | 3 | 0.43 |

| Previous history of aggression (includes domestic violence or older people abuse) | 5 | 0.71 |

| Substance abuse | 4 | 0.57 |

| Behaviours (N = 7 end users) | ||

| Angry | 5 | 0.71 |

| Anxiety | 4 | 0.57 |

| Clenched fist | 6 | 0.86 a |

| Demanding | 6 | 0.86 a |

| Dissatisfied, unhappy or frustrated | 3 | 0.43 |

| Distressed | 4 | 0.57 |

| Glaring or staring | 4 | 0.57 |

| Intimidating | 4 | 0.57 |

| Irrational or bad attitude | 4 | 0.57 |

| Irritable | 4 | 0.57 |

| Mumbling | 3 | 0.43 |

| Pacing or restlessness | 3 | 0.43 |

| Resisting care | 5 | 0.71 |

| Tone of voice (i.e., sarcasm and demeaning) | 4 | 0.57 |

| Use of threatening language | 6 | 0.86 a |

| Clinical presentation (N = 8 end users) | ||

| Alcohol and/or drug intoxication | 7 | 0.88 a |

| Altered cognitive status (i.e., confusion and dementia) | 7 | 0.88 a |

| Brought in by ambulance | 0 | 0 |

| Brought in by police | 5 | 0.63 |

| Drug seeking presentation | 6 | 0.75 |

| Female patients | 0 | 0.00 |

| Male patients | 0 | 0.00 |

| Non‐compliant with medications (mental health patients) | 4 | 0.50 |

| Older adults | 0 | 0 |

| Pain or discomfort | 2 | 0.25 |

| Parents of young children | 0 | 0 |

| Suicidal or self‐harming | 4 | 0.50 |

| Younger age | 0 | 0 |

Relevant item‐level content validity index.

There is a lack of consensus about the adequacy of sample size for content validity (Anthoine et al., 2014), but arbitrarily, 5–10 ratings are considered sufficient (Almanasreh et al., 2019). Recruitment for content validity was initiated in the primary study ED (Round 1) and later via the national professional body for ED nurses (Round 2; College of Emergency Nursing Australasia [CENA]). End users, mainly nurses, were those who self‐reported experience of OV while working in ED. They were encouraged to forward the study invitation to peers in other EDs, because wider involvement could enable broader generalizability of the tool being developed. No identifying information was collected from end users to encourage open responses (Cabilan et al., 2021).

Content validity was undertaken in two rounds of end user review. As noted above, in the first round, the questionnaire was sent to N = 22 end users (primarily from the primary study ED) who were purposively selected based on experience (novice and experienced) and engagement with OV issues. They were prompted to nominate whether they thought risk assessment for OV should be undertaken specifically, using individual risk items (from the list of 34 drawn from the wider literature), or broadly, using the three risk domains already developed (Cabilan & Johnston, 2019). If individual risk items were preferred, end users then had to rate each of the 34 OV risk items (Table 1) as 1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = quite relevant, 4 = highly relevant (Polit & Beck, 2006). Ratings were dichotomized to either not relevant (rating of 1 or 2) or relevant (rating of 3 or 4), then relevant ratings were divided by the total number of experts to derive an item‐level content validity index (I‐CVI). For an item to be included as a prompt in the tool, its index had to be ≥0.78 (Polit & Beck, 2006). If tool item prompts were close to this cut‐off, discussion ensued between the authors for a decision to retain or eliminate items. Employing this adjunct inductive process is consistent with content validity methodology to improve the reliability of prompts being included to assess for OV (Dixon & Johnston, 2019). These data were used to develop a preliminary version of the tool.

In the second round, the preliminary tool was re‐sent to the end users from Round 1 and also to all CENA members to enable a much broader participant pool to contribute. In addition to relevant ratings, end users were asked also to rate the clarity of the preliminary tool on a 1–4 scale: 1 = not clear, 2 = somewhat clear needing major revisions to be clear, 3 = quite clear needing minor revisions to be clear, 4 = clear requiring no alterations to be clear. These ratings were dichotomized to unclear (rating of 1 or 2) and clear (rating of 3 or 4) to calculate per cent agreement for clear ratings between end users. The preliminary tool was updated in response to the second round of ratings from end users. The outcome of this phase was a three‐domain OV risk assessment tool that included specific items as prompts in each domain draft for subsequent testing and refinement in Phases 2 and 3.

4.3.2. Phase 2: Predictive validity

The second phase of tool development consisted of testing the tool developed in Phase 1 against the existing OV data from the incident register collected by the OV audit nursing staff. For each presentation, the primary author (CJC) scrutinized triage notes for any documented evidence of OV risk items. Then, each presentation was matched with the OV incident register in the primary study ED to determine the occurrence of OV during their ED stay. For the sample size calculation, OV prevalence was conservatively estimated at 5%, the lowest threshold for predictive validity sample size calculation for sensitivity and specificity (Bujang & Adnan, 2016). This estimate was also informed by a systematic review with a calculated prevalence of 0.11% (Nikathil et al., 2017). Thus, to have 80% power to detect sensitivity or specificity higher than 50%, the sample size needed to be N = 3980 or N = 209, respectively (Bujang & Adnan, 2016). To meet the required sample size, a month of ED presentations (N = 5523) with the highest OV prevalence was selected. Five per cent of the dataset (N = 276) was randomly selected and checked for agreement by another author (BL).

Sensitivity and specificity were calculated where values can range from 0% to 100%. Sensitivity was determined by the proportion of presentations that correctly identified by application of the tool as ‘violent’. Specificity represented the proportion of presentations correctly identified as not being violent (Bewick et al., 2004). Positive likelihood ratio (PLR) was also calculated to quantify the probability of an OV if a risk item was present. PLR of <5, 5–10 and >10 were interpreted as small, moderate, and high likelihood that OV will occur, respectively (Attia, 2003). For the different risk ratings: low (score = 0 risk item), moderate (score = 1 risk item) and high (score = 2–3 risk items), area under the curve (AUC) was plotted using sensitivity (y axis) and 1 − specifity (x axis). AUC values range from 0.5 to 1; the closer the value is to 1, the more accurate the risk ratings are (Bewick et al., 2004).

4.3.3. Phase 3: Inter‐rater reliability

The triage notes of each presentation in the dataset were examined independently for documented evidence of any of the three OV risk items by trained (CJC) and untrained (BL) assessors. To have 80% power to detect κ ≥ 0.60, the sample size needs to be N = 192 (Shan, 2016); therefore, the randomly selected dataset from Phase 2 (predictive validity) was reused. The presence of a risk item was assigned 1, absence a 0 so that Cohen's kappa (κ) could be calculated (McHugh, 2012). Possible κ values were 0–0.20 (no agreement), 0.21–0.39 (minimal agreement), 0.40–0.59 (weak agreement), 0.60–0.79 (moderate agreement), 0.80–0.90 (strong agreement) and ≥0.91 (almost perfect agreement; McHugh, 2012).

Statistical analyses for predictive validity and inter‐rater reliability were conducted in IBM SPSS v23.0. Tests with corresponding p value of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

4.4. Ethical considerations

Each study was approved by the health service (HREC/19/QMS/52677; LNR/2021/QMS/73342) and university human research ethics committees (2019/002683; 2021/000519).

5. RESULTS

5.1. Content validity

In the first round of content validity, N = 11 end users responded (50% response rate). Six of these end users considered it appropriate for nurses to assess OV risk broadly based on three domains: patient history, currently evident behaviours and current clinical presentation. Eight end users then provided relevance ratings for 34 items (Table 1). Overall, results indicated that:

None of the six individual risk items listed in under patient history achieved a relevant I‐CVI (≥0.78). After discussion and reflection on existing evidence (Cabilan et al., 2020; Pich et al., 2017; Spelten et al., 2020), consensus moderation directed that previous history of aggression (CVI = 0.71) be included as a relevant risk domain of OV.

Three of the 15 specific behaviours had a relevant I‐CVI (I‐CVI = 0.86): (a) clenched fist; (b) demanding; and (c) use of threatening language (Table 1). Again, consensus moderation informed by end user input and consideration of previous evidence (Cabilan et al., 2020; Spelten et al., 2020) directed that (d) angry and (e) resisting care behaviours be included as prompting items in the tool, under the domain of behavioural concern, despite both scoring a I‐CVI below the 0.78 threshold.

Of the 13 item characteristics associated with clinical presentation domain, two were considered highly relevant (I‐CVI = 0.88). These were (a) alcohol and/or drug intoxication and (b) altered cognitive status. A third, a drug‐seeking presentation (I‐CVI = 0.75), was discussed. Consensus discussion concluded that this is a potentially prejudicial and somewhat unquantifiable construct, and so it was excluded.

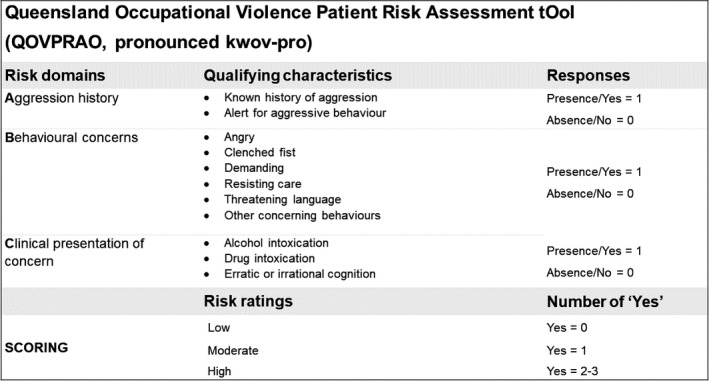

Based on the responses in Round 1, the preliminary tool had three single elements representing risk domains: aggression history, behavioural concerns and clinical presentation/s of concern. The key individual risk items were then used as prompts for each domain, to prompt the assessor to look for each and so enable the assessor to discriminate constituting characteristics for each risk domain (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The Queensland Occupational Violence Patient Risk Assessment tOol (QOVPRAO, pronounced kwov‐pro)

In the second round, N = 81 respondents rated the three‐domain OV risk assessment tool. An overwhelming majority of respondents rated aggression history (n = 70, I‐CVI = 0.86), behavioural concerns (n = 77, I‐CVI = 0.95) and concerns with clinical presentation/s of concern (n = 72, I‐CVI = 0.89) as relevant. A total of 93% (n = 76) responded that the tool is either ‘clear and requires no revisions’ or ‘quite clear’ needing minor revisions to be clear. These minor revisions were undertaken as directed.

5.2. Predictive validity

These three risk domains with their associated item prompts were then used to probe clinical records from the primary ED. Of the 5523 presentations recorded over 1 month, 157 (2.8%) initiated OV incidents as evidenced by the contemporaneous OV risk register. Of those 157 incidents, 60 (38.2%) were verbal, 20 (12.7%) were physical and 77 (49.1%) were both verbal and physical violence.

Table 2 shows the distribution of the recorded instances of aggression history, behavioural concerns and clinical presentation/s of concern in the triage notes of the study population. Overall, the recorded prevalence of documented aggression history was 3% (n = 165), behavioural concern was 3.1% (n = 170) and clinical presentation of concern was 9.1% (n = 503).

TABLE 2.

The prevalence of each occupational violence risk category amongst those who had a violent incident (+), did not have a violent incident (−) and in the overall study population

| Risk assessment domains | Incident (+), N = 157 | Incident (−), N = 5366 | Overall, N = 5523 | Sens (%) | Spec (%) | +LR | Inter‐rater reliability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | κ | p | ||||

| Aggression history | 34 | 21.7 | 131 | 2.4 | 165 | 3 | 22 | 98 | 9.0 | 0.67 | <.01 |

| Behavioural concerns | 49 | 31.2 | 121 | 2.3 | 170 | 3.1 | 31 | 98 | 13.6 | 0.60 | <.01 |

| Concerns with clinical presentation | 87 | 55.4 | 416 | 7.8 | 503 | 9.1 | 55 | 92 | 7.1 | 0.75 | <.01 |

Abbreviations: +LR, positive likelihood ratio; p, statistical value of Cohen's kappa; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; κ, Cohen's kappa.

Single risk domains show 22%–55% sensitivity, but 92%–98% specificity, which is indicative that the tool is moderately sensitive for predicting potentially violent patients and highly specific for predicting non‐violent patients. The likelihood ratios presented in Table 2 can be interpreted as presentations with aggression history and behavioural concerns, and those who were flagged with concerns relating to their clinical presentation were 9.0, 13.6 and 7.1 times (respectively) more likely to perpetrate OV than those who did not.

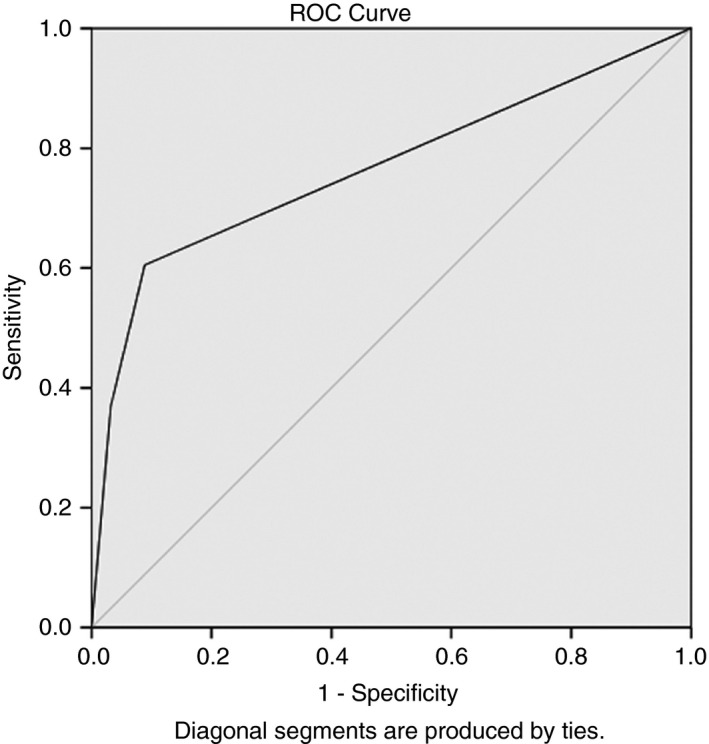

Using pre‐specified risk ratings of low (score = 0 risk domain present), moderate (score = 1 risk domain present) and high (score = 2–3 risk domains present), the AUC is 0.77 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.7–0.81, p < .01), indicating moderate predictive validity (Figure 3). Moderate risk yields 61% sensitivity and specificity of 91%. High risk rating is associated with a sensitivity of 37% and specificity of 97%.

FIGURE 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve using of risk ratings: Low (score = 0 risk domain present), moderate (score = 1 risk domain present) and high (score = 2–3 risk domains present). The area under the curve is 0.77 (95% confidence interval 0.7–0.81, p < .01)

5.3. Inter‐rater reliability

Inter‐rater reliability kappa values ranged from 0.67 to 0.75 (p < .01) aggression history, behavioural concerns and clinical presentation/s of concern (Table 2). These indicate moderate agreement between a trained and untrained assessor.

6. THE INSTRUMENT

The instrument developed from the three phases is the Queensland Occupational Violence Patient Risk Assessment tOol (QOVPRAO, pronounced kwov‐pro). In the QOVPRAO, OV risk is assessed using three domains: aggression history, behavioural concerns and clinical presentation/s of concern (see Figure 2). Supplementing these domains are qualifying characteristics that can be used to prompt the assessor to discriminate the presence or absence of a risk domain. Presence is marked yes, with a corresponding value of 1. Absence is marked no, with a corresponding value of 0. The values are summated, so that risk ratings can be calculated and judged as 0 = low risk, 1 = moderate risk and 2–3 = high risk (Figure 2).

7. DISCUSSION

In a series of three studies, we developed and validated the QOVPRAO, the three‐domain OV risk assessment tool for use by staff with patients in EDs. The tool is useful for assessing OV risk because it covers the three important risk domains identified from the literature and by experts in the area, namely, aggression history, behaviours and clinical presentation. Application of the tool to a retrospective clinical dataset showed that, individually, prompting risk domains had low sensitivity and high specificity. When any one of the risk domains were present and recorded in a patient presentation, an OV incident is moderately likely to occur, based on their PLRs. When applying risk ratings (low, moderate and high) based on the number of risk domains present, the tool demonstrates moderate predictive validity. There was moderate agreement between the two assessors. Thus, the tool meets the key criteria identified by end users in that it is comprehensive, brief and objective.

A comprehensive tool should be sensitive to static and dynamic risk factors, so for this reason OV risk assessment tools need to capture patient history (static risk), behaviours and the context of their clinical presentation (dynamic risk; National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health UK, 2015). To fit with the rapid time‐pressured ED workflow (Cabilan et al., 2020) and facilitate consistent adoption (Levin et al., 2016), an OV risk assessment tool needs to be brief (i.e., three to five items). The desire for a tool to be objective captures the desire of ED staff to stay safe but not prejudge or unfairly stereotype ED users (Cabilan et al., 2020). Tool objectivity is measured statistically, based on the association between risk factors or items and OV incidents (Lamont & Brunero, 2009), of which predictive validity is one.

The OV risk assessment tool herein is not the first assessment tool that has been proposed for use in EDs, but it is the first to directly respond to the expressed needs of ED end users. To grasp the novelty of the tool described herein, it is important to recognize the limitations of the tools previously proposed for use in EDs. An ABC approach (assessment, behaviours, conversation) that involves eight to 10 assessment items for each was proposed as a rapid assessment framework (Sands, 2007). The STAMP (Staring and eye contact, Tone and volume of voice, Anxiety, Mumbling and Pacing) and its extension the STAMPEDAR (… Emotions, Disease Process, Assertive/non‐Assertive, Resources; Chapman et al., 2009; Luck et al., 2007) and a 17‐cue assessment tool (Wilkes et al., 2010) were developed as a behaviourally focussed framework for assessing violence risk in patients. These tools have not seen widespread application because of their length, which does not conform to typical triage workflows and busy EDs. The Violence Risk Screen Decision Support was a digital single‐item screen prompt at triage if patients are at risk of violence based on the nurses' subjective perceptions of risk (Daniel, 2015). The Broset Violence Checklist was primarily designed to capture behaviours of inmates with mental illness in a maximum security unit (Linaker & Busch‐Iversen, 1995) and has been used in EDs with some success (Partridge & Affleck, 2018; Senz et al., 2020). Items in the Broset Violence Checklist (Linaker & Busch‐Iversen, 1995) suggest that some form of violence must have already occurred to trigger an alert, that is, boisterous behaviour, threats and attacking objects, so its use in EDs negates the purpose of OV prevention through risk assessment. The three‐domain OV risk assessment tool (QOVPRAO) builds on these existing tools and addresses their limitations.

The logical sequelae to the development of this tool is the implementation of the tool in the study ED. Successful implementation is underpinned by end users' confidence and capacity to conduct assessments consistently (Woods, 2013) and to respond to potentially or actually violent patients (Viljoen et al., 2018). Hence, the implementation in the local ED will include training and support on how to use the tool, the frequency of assessments in the ED and the appropriate management of potentially risky presentations for end users. The frequency of violence risk assessments will be aligned with the frequency of vital signs observations, that is, on arrival, then every 30 min if stable or every 15 min if unstable. Each risk rating will have specific management recommendations for patients, staff and ED environment (Cabilan et al., 2021). Following such implementation, the impact of the tool will be evaluated against clinically relevant outcomes including its effectiveness (OV rate and cost‐effectiveness), safety (staff injuries and patient injuries) and patient‐centredness (coercive restraints).

7.1. Limitations

We are unable to estimate the representativeness of end users due to their anonymity. However, we can presume that novice and experienced end users are represented because of the purposive and snowball sampling and the broad CENA membership. Retrospective analysis of triage notes is dependent on the completeness of documentation. For example, the prevalence of aggression history and behaviours were lower compared with clinical presentation. This could be due to underreporting of these factors. In pursuit of accuracy and possibly higher test sensitivity, a prospective study could have been conducted. However, it could not be conducted without influencing the outcome (OV incident) as it would be unethical and unsafe not to flag risky patients. As a consequence of the retrospective design, information about the risk factors relied on the triage notes, so changes to patient risk after triage were not captured. This could have misrepresented the actual prevalence of risk items during the ED stay. In its early stages, the tool will have limited generalizability. However, by isolating the initial implementation to one facility (the study ED), challenges can be thoroughly evaluated and surmounted. Subsequent to this, the authors intend to extend the tool to inpatients and the wider health service.

8. CONCLUSION

This project successfully designed a novel OV risk assessment tool, specifically developed for use in EDs. This three‐domain tool enables nurses and other staff to formulate a patient's risk of OV. It cues review of the patient's aggression history, behaviours and clinical presentation, using associated validated prompts, to trigger a relative risk stratification: low (score = 0 risk domain present), moderate (score = 1 risk domain present) and high (score = 2–3 risk domains present). The tool has acceptable predictive validity and inter‐rater reliability. It can, therefore, be implemented in EDs to help reduce the risk of OV and all the consequential impacts of OV on patients, staff, health services and the broader society.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15166.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was generously supported by the College of Emergency Nursing Australasia (CENA). The views of these researchers do not necessarily represent the views of CENA. C.J. Cabilan is a PhD candidate whose candidature is funded by a Queensland Health Advancing Clinical Research Fellowship. Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley ‐ University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Cabilan, C. J. , McRae, J. , Learmont, B. , Taurima, K. , Galbraith, S. , Mason, D. , Eley, R. , Snoswell, C. & Johnston, A. N. (2022). Validity and reliability of the novel three‐item occupational violence patient risk assessment tool. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78, 1176–1185. 10.1111/jan.15166

Contributor Information

C. J. Cabilan, Email: cj.cabilan@health.qld.gov.au, @cjcabilan.

Joshua McRae, @JoshuaMcRae15.

Centaine Snoswell, @CSnoswell.

Amy N. B. Johnston, @amynbjohnston1

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Akther, S. F. , Molyneaux, E. , Stuart, R. , Johnson, S. , Simpson, A. , & Oram, S. (2019). Patients' experiences of assessment and detention under mental health legislation: Systematic review and qualitative meta‐synthesis. BJPsych Open, 5(3), e37. 10.1192/bjo.2019.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almanasreh, E. , Moles, R. , & Chen, T. F. (2019). Evaluation of methods used for estimating content validity. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 15(2), 214–221. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.03.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthoine, E. , Moret, L. , Regnault, A. , Sébille, V. , & Hardouin, J.‐B. (2014). Sample size used to validate a scale: A review of publications on newly‐developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12, 176–176. 10.1186/s12955-014-0176-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia, J. (2003). Moving beyond sensitivity and specificity: Using likelihood ratios to help interpret diagnostic tests. Australian Prescriber, 26(5), 111–113. 10.18773/austprescr.2003.082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bewick, V. , Cheek, L. , & Ball, J. (2004). Statistics review 13: Receiver operating characteristic curves. Critical Care, 8(6), 1–5. 10.1186/cc3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujang, M. A. , & Adnan, T. H. (2016). Requirements for minimum sample size for sensitivity and specificity analysis. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 10(10), YE01–YE06. 10.7860/jcdr/2016/18129.8744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabilan, C. J. , & Johnston, A. N. B. (2019). A scoping review of patient‐related occupational violence risk factors and risk assessment tools in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 31(5), 730–740. 10.1111/1742-6723.13362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabilan, C. J. , Johnston, A. N. B. , & Eley, R. (2020). Engaging with nurses to develop an occupational violence risk assessment tool for use in emergency departments: A participatory action research inquiry. International Emergency Nursing, 52, 100856. 10.1016/j.ienj.2020.100856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabilan, C. J. , Johnston, A. N. B. , Eley, R. , & Snoswell, C. (2021). What can we do about occupational violence in emergency departments? A survey of emergency staff. Journal of Nursing Management. 10.1111/jonm.13294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, R. , Perry, L. , Styles, I. , & Combs, S. (2009). Predicting patient aggression against nurses in all hospital areas. British Journal of Nursing, 18(8), 476–483. 10.12968/bjon.2009.18.8.41810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole, G. , Stefanus, D. , Gardner, H. , Levy, M. J. , & Klein, E. Y. (2016). The impact of interruptions on the duration of nursing interventions: A direct observation study in an academic emergency department. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(6), 457–465. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, C. (2015). An evaluation of violence risk screening at triage in one Australian emergency department. The University of Melbourne; https://minerva‐access.unimelb.edu.au/bitstream/handle/11343/56522/Catherine%20Daniel%20197028%209th%20November%202015.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, C. , Gerdtz, M. , Elsom, S. , Knott, J. , Prematunga, R. , & Virtue, E. (2015). Feasibility and need for violence risk screening at triage: An exploration of clinical processes and public perceptions in one Australian emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal, 32(6), 457–462. 10.1136/emermed-2013-202979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ettorre, G. , Mazzotta, M. , Pellicani, V. , & Vullo, A. (2018). Preventing and managing workplace violence against healthcare workers in emergency departments. Acta Biomed, 89, 28–36. 10.23750/abm.v89i4-S.7113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVon, H. A. , Block, M. E. , Moyle‐Wright, P. , Ernst, D. M. , Hayden, S. J. , Lazzara, D. J. , Savoy, S. M. , & Kostas‐Polston, E. (2007). A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 39(2), 155–164. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, D. , & Johnston, M. (2019). Content validity of measures of theoretical constructs in health psychology: Discriminant content validity is needed. British Journal of Health Psychology, 24(3), 477–484. 10.1111/bjhp.12373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, S. , Müller, M. , Hantikainen, V. , Kok, G. , Dassen, T. , & Halfens, R. J. G. (2013). Risk factors associated with patient and visitor violence in general hospitals: Results of a multiple regression analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(3), 374–385. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling, R. N. , Yassi, A. , Smailes, E. , Lovato, C. Y. , & Koehoorn, M. (2011). Evaluation of a violence risk assessment system (the Alert System) for reducing violence in an acute hospital: A before and after study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(5), 534–539. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, S. , & Brunero, S. (2009). Risk analysis: An integrated approach to the assessment and management of aggression/violence in mental health. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 5(1), 25–32. 10.1017/S1742646408001349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lanctôt, N. , & Guay, S. (2014). The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers: A systematic literature review of the consequences. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(5), 492–501. 10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Large, M. M. , & Nielssen, O. B. (2011). Probability and loss: Two sides of the risk assessment coin. The Psychiatrist, 35(11), 413–418. 10.1192/pb.bp.110.033910 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, S. K. , Nilsen, P. , Bendtsen, P. , & Bulow, P. (2016). Structured risk assessment instruments: A systematic review of implementation determinants. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 23(4), 602–628. 10.1080/13218719.2015.1084661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linaker, O. M. , & Busch‐Iversen, H. (1995). Predictors of imminent violence in psychiatric inpatients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 92(4), 250–254. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck, L. , Jackson, D. , & Usher, K. (2007). STAMP: Components of observable behaviour that indicate potential for patient violence in emergency departments [article]. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 59(1), 11–19. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04308.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morphet, J. , Griffiths, D. , Beattie, J. , Reyes, D. V. , & Innes, K. (2018). Prevention and management of occupational violence and aggression in healthcare: A scoping review. Collegian, 25(6), 621–632. 10.1016/j.colegn.2018.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health UK . (2015). Violence and aggression: Short‐term management in mental health, health and community settings: Updated edition. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng10/evidence/full‐guideline‐pdf‐70830253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikathil, S. , Olaussen, A. , Gocentas, R. A. , Symons, E. , & Mitra, B. (2017). Workplace violence in the emergency department: A systematic review and meta analysis [review]. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 29(3), 265–275. 10.1111/1742-6723.12761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikathil, S. , Olaussen, A. , Symons, E. , Gocentas, R. , O'Reilly, G. , & Mitra, B. (2018). Increasing workplace violence in an Australian adult emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 30(2), 181–186. 10.1111/1742-6723.12872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, B. , & Affleck, J. (2018). Predicting aggressive patient behaviour in a hospital emergency department: An empirical study of security officers using the Brøset Violence Checklist. Australasian Emergency Care, 21(1), 31–35. 10.1016/j.auec.2017.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pich, J. V. , Kable, A. , & Hazelton, M. (2017). Antecedents and precipitants of patient‐related violence in the emergency department: Results from the Australian VENT Study (Violence in Emergency Nursing and Triage). Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal, 20(3), 107–113. 10.1016/j.aenj.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. F. , & Beck, C. T. (2006). The content validity index: Are you sure you know what's being reported? Critique and recommendations. Research in Nursing and Health, 29(5), 489–497. 10.1002/nur.20147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands, N. (2007). An ABC approach to assessing the risk of violence at triage. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal, 10(3), 107–109. 10.1016/j.aenj.2007.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senz, A. , Ilarda, E. , Klim, S. , & Kelly, A. M. (2020). Development, implementation and evaluation of a process to recognise and reduce aggression and violence in an Australian emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 33, 665–671. 10.1111/1742-6723.13702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan, G. (2016). Sample size calculation for agreement between two raters with binary endpoints using exact tests. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 27(7), 2132–2141. 10.1177/0962280216676854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, S. , Shahoei, R. , Nouri, B. , Almvik, R. , & Valiee, S. (2020). Effect of an education program, risk assessment checklist and prevention protocol on violence against emergency department nurses: A single center before and after study. International Emergency Nursing, 100813. 10.1016/j.ienj.2019.100813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spelten, E. , Thomas, B. , O'Meara, P. , van Vuuren, J. , & McGillion, A. (2020). Violence against emergency department nurses; can we identify the perpetrators? PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0230793. 10.1371/journal.pone.0230793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speroni, K. G. , Fitch, T. , Dawson, E. , Dugan, L. , & Atherton, M. (2014). Incidence and cost of nurse workplace violence perpetrated by hospital patients or patient visitors. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 40(3), 218–228. 10.1016/j.jen.2013.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen, J. L. , Cochrane, D. M. , & Jonnson, M. R. (2018). Do risk assessment tools help manage and reduce risk of violence and reoffending? A systematic review. Law and Human Behavior, 42(3), 181–214. 10.1037/lhb0000280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes, L. , Mohan, S. , Luck, L. , & Jackson, D. (2010). Development of a violence tool in the emergency hospital setting. Nurse Researcher, 17(4), 70–82. 10.7748/nr2010.07.17.4.70.c7926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A. H. , Ray, J. M. , Rosenberg, A. , Crispino, L. , Parker, J. , McVaney, C. , Iennaco, J. D. , Bernstein, S. L. , & Pavlo, A. J. (2020). Experiences of individuals who were physically restrained in the emergency department. JAMA Network Open, 3(1), e1919381. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods, P. (2013). Risk assessment and management approaches on mental health units. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 20(9), 807–813. 10.1111/jpm.12022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.