Abstract

The development of synthetic non‐equilibrium systems opens doors for man‐made life‐like materials. Yet, creating distinct transient functions from artificial fuel‐driven structures remains a challenge. Building on our ATP‐driven dynamic covalent DNA assembly in an enzymatic reaction network of concurrent ATP‐powered ligation and restriction, we introduce ATP‐fueled transient organization of functional subunits for various functions. The programmability of the ligation/restriction site allows to precisely organize multiple sticky‐end‐encoded oligo segments into double‐stranded (ds) DNA complexes. We demonstrate principles of ATP‐driven organization into sequence‐defined oligomers by sensing barcode‐embedded targets with different defects. Furthermore, ATP‐fueled DNAzymes for substrate cleavage are achieved by transiently ligating two DNAzyme subunits into a dsDNA complex, rendering ATP‐fueled transient catalytic function.

Keywords: Chemical Reaction Network, Dissipative Self-Assembly, DNA Nanoscience, DNAzyme, Transient Catalysis

Fuel‐driven DNA self‐assemblies with various transient functions such as catalytic activity are realized in an enzymatic reaction network of concurrent ATP‐powered ligation and restriction of DNA species. The catalytic function with a temporal lifetime can be repeatedly activated by multiple additions of ATP fuel, allowing for fuel‐dependent substrate cleavage.

Living systems use dynamic non‐equilibrium structures, in which adaptive biological functions are maintained by continuous input of energy. [1] In living cells, cytoskeletons such as actin filaments and microtubules are dynamically formed by temporally activating corresponding self‐assembling units fueled by biological fuels (ATP and GTP). [2] Motor proteins powered by ATP move along them and convert chemical energy into mechanical work, [3] which plays pivotal roles for intracellular transport and for spindle apparatus formation and chromosome separation during mitosis and meiosis. [4] The non‐equilibrium nature of these structures serves as an inspiration for chemists to develop more life‐like synthetic systems that cannot be achieved from equilibrium‐type self‐assemblies.

Great efforts have been made in chemical fuel‐driven supramolecular self‐assemblies to achieve various structures and materials, such as supramolecular fibrils, conformational switches, colloid clustering, motion, and hydrogels with a fuel‐dependent lifetime. [5] DNA has emerged as an ideal building block for self‐assemblies owing to its programmable molecular recognition, and static DNA nanostructures can be coupled to dynamic operation conditions to achieve higher‐order autonomous structures. [6] DNA‐based systems for allosteric switches, cargo uptake and release, as well as DNA nanotubes have been autonomously controlled by nucleic acid fuel strands and enzyme‐assisted networks. [7] Unfortunately, existing examples mostly focus on system design and structural complexities, and fuel‐driven systems with transient functions, such as catalytic activity, are still very rare. Relevant examples include environmental signal regulated transient vesicle formation for enhanced catalytic activity at the hydrophobic bilayer owing to increased solubility of reactants and light‐triggered transient release of azobenzene derivative inhibitor from a catalytic ligand for temporally enhanced catalytic activity. [8] Additionally, fuel strands have been used to trigger transient organization of functional motifs for a photoactive photosensitizer/acceptor module, in which the assembly is rather energetically down‐hill from the beginning. [9]

We previously reported ATP‐driven dynamic covalent DNA self‐assemblies organized via an enzymatic reaction network (ERN) of concurrent ATP‐powered ligation and restriction, and realized fuel‐driven adaptive properties and dynamic structures from a polymer level to multicomponent colloids and coacervates systems, and very recently we achieved fuel‐driven DNA strand displacement cascades, automatons and DNA nanotubes. [10] Although high system and structural complexities have been achieved in such ATP‐fueled DNA systems, fueled transient functions have not been realized by previous systems. One of the key advantages in such systems is the prominent potential to precisely organize functional motifs due to programmable molecular recognition in ATP‐powered ligation. [10e]

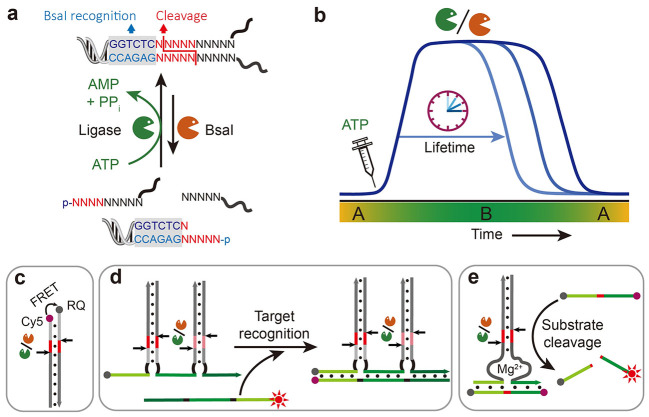

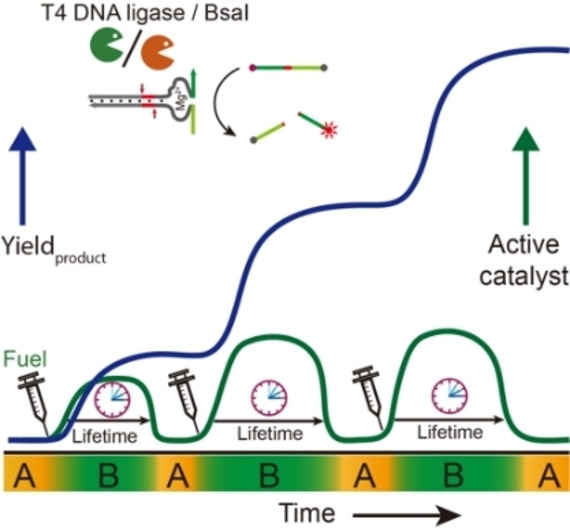

Herein, we introduce ATP‐fueled self‐assemblies with transient functions in the ERN of concurrent ATP‐powered ligation and BsaI‐controlled restriction. Functional subunits are encoded with sticky ends to guide their assemblies on the double‐stranded (ds) DNA complex via ATP‐fueled dynamic ligation (Figure 1a). Importantly, the ligation/cleavage site and the sequence downstream are fully programmable, enabling precise organization of two functional motifs on one dsDNA complex via two steps of consecutive ligation through distinct molecular recognition. The ATP amount regulates the lifetime of the system at a given concentration of enzymes (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

ATP‐fueled DNA assemblies with transient functions. a) Schematic illustration of ATP‐fueled transient organization of functional motifs. b) Programmable lifetime for the fuel‐driven transient functional state. After adding ATP, the system enters into an activated state, state B, from its ground state, state A, which returns to state A once the ATP is consumed. c–e) DNA assemblies at the fuel‐driven active state for c) FRET, d) multivalent target sensing, and e) DNAzyme for substrate cleavage. The dynamic ligation/cleavage sites on the dsDNA are indicated by arrows.

We first show the steps towards target recognition by Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) using appropriately placed fluorophore and quencher molecules on the individual building block. (Figure 1c, d). Finally, we progress towards ATP‐fueled transient catalytic activity for controlled substrate cleavage by transiently ligating two DNAzyme subunits to the dsDNA complex (Figure 1e).

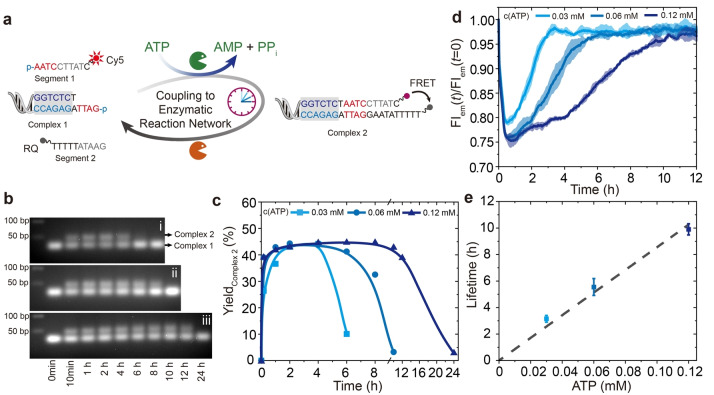

We first discuss the ATP‐fueled transient organization of functional motifs of a FRET pair using Complex 1, Segment 1, and Segment 2 (Figure 2a). Segments 1 and 2 carry the FRET pair that are separated before adding ATP due to their unstable hybridization of 5 base pairs (bp). After adding ATP, Complex 1 consecutively ligates with Segment 1 and Segment 2 to generate Complex 2, where the fluorophore and quencher are in close proximity, thus quenching the fluorescence. Simultaneous BsaI restriction cleaves Complex 2 to reset the system. All building blocks are constantly cycled in a dynamic fashion in the dynamic steady state (DySS).

Figure 2.

ATP‐fueled transient organization of functional motifs. a) Schematic illustration of ATP‐fueled transient FRET. b) Time‐dependent AGE (2 wt.%, 105 V, 1.5 h) corresponding to transient complex 2 with programmable lifetimes by fueling with i) 0.03, ii) 0.06, and iii) 0.12 mM ATP. c) Time‐dependent yield of complex 2 calculated from AGE. Lines are guides to the eye. d, e) Programmable lifetimes seen by time‐dependent FIs at different ATP concentrations. The shaded areas and error bars correspond to the standard deviation of duplicate measurements. Conditions: 37 °C, 10 μM of each DNA species, 0.92 WU T4 DNA ligase, 1 U BsaI, and varied concentration of ATP.

The experiments were performed at 37 °C using 10 μM of each DNA species, 0.92 Weiss units/μL (WU) T4 DNA ligase, 1 unit/μL (U) BsaI, and varied concentration of ATP. Agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) analyses of time‐dependent aliquots of the systems verify the transient formation of Complex 2 with a DySS yield of ca. 45 % (Figure 2b, c; integration of the intensity in AGE). An increase of the ATP concentration from 0.03 to 0.12 mM does not have a significant effect on the DySS yield because we use a significant excess of ATP. Yet, higher ATP concentrations lead to longer lifetimes for Complex 2. Although AGE gives detailed insights into the formation of new species, a higher temporal resolution is provided by FRET analysis. Before adding ATP, no ligation occurs in the system and the fluorophore and quencher are separated, showing fluorescence. Upon adding ATP, quenching occurs (Figure 2d, Figure S1). The consumption of ATP leads to a recovery of the fluorescence intensity (FI). An increase of the ATP concentration from 0.03 to 0.12 mM shifts the lifetime of Complex 2 from ca. 3 to 10 h, as calculated from the point the FI reaches the plateau (Figure 2d, e).

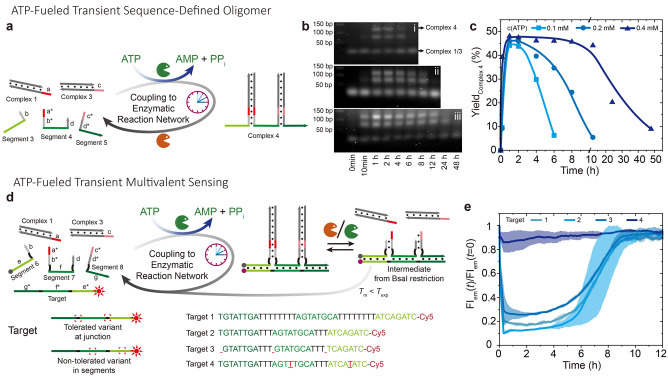

Next, we demonstrate ATP‐fueled sequenced‐defined oligomer for target sensing. Figure 3a shows a first design of a transient sequence‐defined oligomer, where three ssDNA Segments are functionalized with distinct sticky ends so that they can be sequentially ligated to two dsDNA complexes. Before the addition of ATP, Segments 3–5 are separated due to unstable hybridization of 6 bp at the junctions (gray units in the Segments, b,b*,d,d*). Upon adding ATP, they are joined together via ligation with two dsDNA complexes forming a sequence‐defined oligomer, Complex 4, which degrades to monomers after the ATP is consumed.

Figure 3.

ATP‐fueled transient target sensing. a) Schematic illustration of ATP‐fueled transient sequence‐defined oligomer. b) Time‐dependent AGE (2 wt.%, 80 V, 2.5 h) for transient sequence‐defined oligomers with programmable lifetimes by fueling with i) 0.1, ii) 0.2, and iii) 0.4 mM ATP. c) Time‐dependent yield of complex 4 calculated from AGE. Lines are guides to the eye. d) Schematic illustration of ATP‐fueled transient sequence‐defined oligomer for multivalent sensing. e) Time‐dependent FI measurements corresponding to transient sensing of different targets. The shaded areas correspond to the standard deviation of duplicate measurements. Conditions: b) 37 °C, 10 μM of each DNA species, 0.92 WU T4 DNA ligase, 1 U BsaI, and varied concentration of ATP. e) 10 μM of each DNA species for the sequence‐defined oligomer, 5 μM target, and 0.1 mM ATP.

The systems were set at 10 μM of each DNA species, 0.92 WU T4 DNA ligase, 1 U BsaI, and varied concentration of ATP. AGE verifies the transient formation of Complex 4 with programmable lifetimes by different ATP concentrations (Figure 3b). Due to its dynamic nature, some incompletely ligated species are also observed by AGE at longer migration distances. A grayscale analysis of Complex 4 and all other DNA species delivers time‐dependent yields of Complex 4, reaching ca. 45 % (Figure 3c). Increasing the ATP concentration extends the lifetime of Complex 4 from ca. 5 to 24 h, as defined by the point the yield decreases to half of its maximum value.

Having established the principles of recognition, we move forward to transient target sensing by the sequence‐defined oligomer via multivalent hybridization (Figure 3d). Our Target has three 8 nucleotide (nt) barcodes complementary to the green units in Segments 6–8. In the ssDNA Segments, the black 4 nt spacers next to the green barcodes are crucial for spontaneous dissociation of the intermediate from BsaI restriction, because omitting these spacers leads to a kinetically trapped state (Figure S2, Supporting Information Note 1). To better understand the influence and resilience towards defects, we encoded defects into the Target by base deletion (3) and permutation (4). These defects in the Target are located in the black or green parts, respectively. Before adding ATP, Segments 6–8 are separated due to their unstable hybridization with the corresponding complementary sequence (8 bp). After adding ATP, the formed sequence‐defined oligomer emerges and can sense a target for dsDNA formation depending on the target composition. Simultaneously, BsaI restriction triggers dissociation of the Segments from the Target.

The experiments were set at 10 μM of Segments and Complexes and 5 μM Target. The FRET pair on the Target and Segment 6 allows for in‐situ monitoring of the multivalent sensing via a fluorescence spectroscopy. The FRET analysis confirms that transient Target sensing is robust with respect to the variation in the junction length (black part in Targets) as seen by time‐dependent FI measurements of the systems using Targets 1 and 2 (Figure 3e). The ATP‐fueled system using Target 2 displays a stronger quenching (lower FI) than the one using Target 1, and its FI recovery is also more delayed. This indicates a stronger binding affinity towards Target 2 because of its shorter junctions between barcodes (3 nt vs. 8 nt), and accordingly slower dissociation of the intermediate from BsaI restriction. Compared to Target 2, a shortening of the green recognition (base deletion) in Target 3 from 8 to 7 nt leads to less FI decrease, indicating weaker multivalent binding and therefore also slower speed for reaching its DySS for target binding (see Figure S3 for early stages). It is worth noting that Target 3 with 7 nt barcodes requires all three Segments in the sequence‐defined oligomer for efficient target binding, as the melting temperature between Target 3 and two ligated binding Segments is below the experimental temperature (seen by Nupack). Furthermore, two mutations in Target 4 prevent the multivalent recognition and thus the emergence of defined dsDNA output structures (no change in FI). Critically, the difference in sensing of those targets with different variants can also been seen by the kinetics of fluorescence quenching in the early stage of target binding (Figure S3), where the binding of Target 2 has the fastest kinetic due to its stongest binding affinity. It is worth noting that the length of each binding domain in the sequence‐defined oligomer can be variable, and the ATP‐fueled sequence‐defined oligomer with shorter binding domains is expected to be more sensitive to base deletion and mismatch in the targets at a given experimental condition.

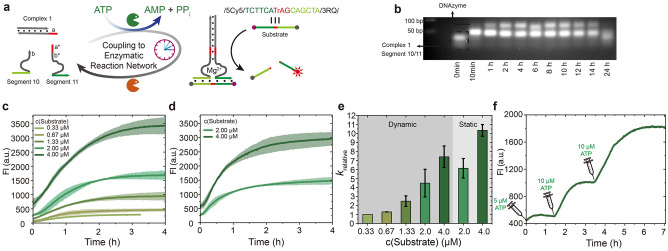

To capitalize on the fuel‐driven transient target sensing, we further envisioned to design an emergent ATP‐fueled transient catalytic function in the DNA assemblies. A DNAzyme capable of catalyzing substrate cleavage has been chosen as a model system to demonstrate this concept due to its facile preparation and characterization. [11] Figure 4a depicts the design for an ATP‐fueled DNAzyme with transient catalytic activity for substrate cleavage. Compared to the other reports, e.g. from Willner's group, which report fuel strand usage to trigger transient organization of split DNAzyme fragments, [11b] the transient DNAzyme here is controlled by an ATP‐driven ERN and the DNAzyme can be maintained in a DySS set by the ratio of the antagonistic enzymes in the ERN, while ATP fuel sets the lifetime of the DNAzyme. Additionally, our system does not generate any DNA waste. Briefly, the DNAzyme subunits are encoded with sticky ends allowing for precise assembly on Complex 1. The Substrate carries a FRET pair at its termini and its length is limited to 15 nt for a well‐quenched fluorescence, which requires shortened barcodes of 6 nt in the DNAzyme. Hence, the following experiments were performed at 25 °C for efficient binding between the ATP‐fueled DNAzyme and the Substrate.

Figure 4.

ATP‐fueled transient DNAzyme. a) Schematic illustration of ATP‐fueled transient DNAzyme for substrate cleavage. b) Time‐dependent AGE (2 wt.%, 105 V, 1.5 h) for transient DNAzyme. c, d) Time‐dependent FI measurements of substrate cleavage by (c) ATP‐fueled transient DNAzyme and (d) static DNAzyme. The shaded areas correspond to the standard deviation of duplicate measurements. e) Relative kinetics for RNA cleavage for both dynamic and static DNAzymes. Error bars correspond to the standard deviation of duplicate measurements. f) Time‐dependent FI measurements corresponding to multiple temporal activations of DNAzyme for controlled substrate cleavage. Conditions: b) 25 °C, 10 μM each DNA species, 0.46 WU T4 DNA ligase, 1 U BsaI, and 0.03 mM ATP. c) The same as above but added varied concentration of Substrate. d) Without BsaI, and fed with varied concentration of Substrate. f) The same as (b) but containing 2.67 μM Substrate, and repeatedly fueled with ATP.

We first demonstrate the ATP‐fueled transient DNAzyme by AGE analyses of time‐dependent aliquots of the system using 10 μM each DNA species, 0.46 WU T4 DNA ligase, 1 U BsaI, and 0.03 mM ATP (Figure 4b). The system shows a DNAzyme yield of ca. 40 % at its DySS (Figure S4). The catalytic function of the formed DNAzyme is verified by feeding with varied concentrations of substrate. Time‐dependent FI measurements verify substrate cleavage by ATP‐fueled DNAzyme (Figure 4c). By varying the substrate concentration from 0.33 to 4 μM, a higher FI corresponding to a higher amount of cleaved Substrate is observed. The time required to reach the FI plateau increases from ca. 1 to 2.5 h. In contrast, a static DNAzyme system without BsaI shows faster kinetics and the time needed to reach the final plateau is shortened by ca. 1 h (Figure 4d). The plotted relative kinetics (calculated from the linear regions of the first 30 min) more clearly show faster reaction speeds by using a higher substrate concentration or by using static DNAzyme (Figure 4e). Critically, the incorporation of BsaI enables ATP‐fueled and timed operation of the catalytic activity for controlling the extent of substrate cleavage with small ATP injections. We demonstrate this concept by a fuel‐driven transient system using 2.67 μM Substrate, wherein low concentrations of ATP were repeatedly added for multiple cycles of transient catalytic activity (Figure 4f). By fueling with 5 μM ATP, there is only a slight increase of FI indicating very small substrate cleavage. It is important to mention that two ligation steps are needed for one complete DNAzyme, and 5 μM ATP significantly limits the yield of DNAzyme at 10 μM of each DNA species. FI stops increasing after the temporally formed DNAzyme is degraded. Then, another 10 μM ATP activates the DNAzyme for a second lifecycle with a significantly higher increase of FI corresponding to a higher amount of substrate cleavage. A third cycle of ATP‐fueled catalysis is further realized by adding 10 μM ATP again. A control without ATP shows no FI increase, and, thus, no substrate cleavage is observed (Figure S5). Hence, we achieve ATP‐fueled transient DNAzymes with temporal catalytic function for controlled substrate cleavage and timed operation. In a general perspective, we expect that fuel‐driven transient catalytic systems can be powerful for detection of fuel molecules (analytes) via downstream signal amplification from the catalytic reaction, and its transient nature allows for reusability of the system, and, thus, real‐time detection of analyte fluctuation (repeatedly fueled).

Taken together, we have introduced ATP‐fueled transient organization of DNA motifs for versatile functions in the ERN of concurrent ATP‐powered ligation and BsaI‐controlled restriction. ATP‐powered ligation joins the functional subunits together to a dsDNA complex while BsaI restriction separates them due to unstable hybridization of the intermediate from restriction. We showed increased functional complexities in these fuel‐driven transient active structures ranging from FRET to multivalent sensing, and, finally, DNAzymes with catalytic function. This strategy towards fuel‐driven active structures with various functions contrasts earlier work on non‐equilibrium systems that often focuses on system design and structural complexity. It adds a new perspective to presently existing non‐equilibrium systems, and paves new avenues for active and functional materials design. The multivalent recognition and emergence of defined oligomers from mixtures of components also provides a relevant toolbox for fundamental systems chemistry and origin of life research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by the European Research Council starting Grant (TimeProSAMat) Agreement 677960. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

J. Deng, W. Liu, M. Sun, A. Walther, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202113477; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202113477.

Contributor Information

Dr. Jie Deng, Email: jie_deng@dfci.harvard.edu.

Prof. Dr. Andreas Walther, Email: andreas.walther@uni-mainz.de.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Vale R. D., Cell 2003, 112, 467–480; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Salazar-Roa M., Malumbres M., Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Horio T., Hotani H., Nature 1986, 321, 605–607; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Pollard T. D., Borisy G. G., Cell 2003, 112, 453–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hunter A. W., Wordeman L., J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 4379–4389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hirokawa N., Noda Y., Okada Y., Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1998, 10, 60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Sorrenti A., Leira-Iglesias J., Sato A., Hermans T. M., Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15899; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Maity S., Ottelé J., Santiago G. M., Frederix P. W., Kroon P., Markovitch O., Stuart M. C., Marrink S. J., Otto S., Roos W. H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 13709–13717; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Dhiman S., Jain A., George S. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1329–1333; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 1349–1353; [Google Scholar]

- 5d. Van Ravensteijn B. G., Hendriksen W. E., Eelkema R., Van Esch J. H., Kegel W. K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9763–9766; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5e. Che H., Zhu J., Song S., Mason A. F., Cao S., Pijpers I. A., Abdelmohsen L. K., van Hest J. C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 13113–13118; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 13247–13252; [Google Scholar]

- 5f. Singh N., Lainer B., Formon G. J., De Piccoli S., Hermans T. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 4083–4087; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5g. Deng J., Walther A., Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2002629; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5h. Mishra A., Dhiman S., George S. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 2740–2756; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 2772–2788; [Google Scholar]

- 5i. Fan X., Walther A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 3619–3624; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 3663–3668; [Google Scholar]

- 5j. Heinen L., Walther A., Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 4100–4107; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5k. Heuser T., Merindol R., Loescher S., Klaus A., Walther A., Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1606842; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5l. Heuser T., Weyandt E., Walther A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13258–13262; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 13456–13460; [Google Scholar]

- 5m. Fan X., Walther A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 11398–11405; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 11499–11506. [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Douglas S. M., Dietz H., Liedl T., Högberg B., Graf F., Shih W. M., Nature 2009, 459, 414–418; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Rothemund P. W., Nature 2006, 440, 297–302; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6c. DeLuca M., Shi Z., Castro C. E., Arya G., Nanoscale Horiz. 2020, 5, 182–201; [Google Scholar]

- 6d. Nummelin S., Shen B., Piskunen P., Liu Q., Kostiainen M. A., Linko V., ACS Synth. Biol. 2020, 9, 1923–1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Del Grosso E., Ragazzon G., Prins L. J., Ricci F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5582–5586; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 5638–5642; [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Del Grosso E., Amodio A., Ragazzon G., Prins L. J., Ricci F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10489–10493; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 10649–10653; [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Agarwal S., Franco E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 7831–7841; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7d. Deng J., Walther A., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Maiti S., Fortunati I., Ferrante C., Scrimin P., Prins L. J., Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 725–731; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Chen R., Neri S., Prins L. J., Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 868–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang C., Zhou Z., Ouyang Y., Wang J., Neumann E., Nechushtai R., Willner I., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 12120–12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Heinen L., Walther A., Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw0590; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Deng J., Walther A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 685–689; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Sun M., Deng J., Walther A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 18161–18165; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 18318–18322; [Google Scholar]

- 10d. Deng J., Bezold D., Jessen H. J., Walther A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 12084–12092; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 12182–12190; [Google Scholar]

- 10e. Deng J., Walther A., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3658; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10f. Deng J., Walther A., Chem 2020, 6, 3329–3343; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10g. Deng J., Walther A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 21102–21109; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10h. Deng J., Walther A., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Shimron S., Elbaz J., Henning A., Willner I., Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 3250–3252; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Wang S., Yue L., Wulf V., Lilienthal S., Willner I., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 17480–17488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information