Abstract

8‐Nitro‐4H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazinones (BTZs) are potent in vitro antimycobacterial agents. New chemical transformations, viz. dearomatization and decarbonylation, of two BTZs and their influence on the compounds’ antimycobacterial properties are described. Reactions of 8‐nitro‐2‐(piperidin‐1‐yl)‐6‐(trifluoromethyl)‐4H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazin‐4‐one and the clinical drug candidate BTZ043 with the Grignard reagent CH3MgBr afford the corresponding dearomatized stable 4,5‐dimethyl‐5H‐ and 4,7‐dimethyl‐7H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazines. These methine compounds are structurally characterized by X‐ray crystallography for the first time. Reduction of the BTZ carbonyl group, leading to the corresponding markedly non‐planar 4H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazine systems, is achieved using the reducing agent (CH3)2S ⋅ BH3. Double methylation with dearomatization and decarbonylation renders the two BTZs studied inactive against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis, as proven by in vitro growth inhibition assays.

Keywords: benzothiazinones, BTZ043, benzothiazines, DprE1 inhibitors, tuberculosis

The importance of carbonyl: Reactions of the antituberculosis drug candidate BTZ043 and its 2‐piperidinyl derivative with the Grignard reagent CH3MgBr afforded the dearomatized stable 4,5‐dimethyl‐5H‐ and 4,7‐dimethyl‐7H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazines, which were structurally characterized by X‐ray crystallography. Reduction of the BTZ carbonyl group was achieved with the reducing agent (CH3)2S ⋅ BH3. Both chemical transformations resulted in loss of antimycobacterial activity.

Introduction

8‐Nitro‐4H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazinones (BTZs) 1 a and 1 b (BTZ043) are known as potent antitubercular agents (Scheme 1). [1] After entering the catalytic site of decaprenylphosphoryl‐β‐d‐ribose 2′‐epimerase (DprE1), a mycobacterial enzyme crucial for cell wall synthesis, the 8‐nitro group is reduced to a nitroso group, which covalently binds to a cysteine residue. BTZs inhibit DprE1 at μM to nM minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs). High target‐ and species‐specificity renders BTZs promising antitubercular drug candidates. Compound 1 b and macozinone (PBTZ169) [2] have reached clinical trials. [3] However, stability problems, especially metabolic reduction of the nitro group and BTZ core, and the relatively high dosage of 300–600 mg/day in clinical studies [2] in spite of the very high in vitro activity motivate further research on this compound class.

Scheme 1.

Chemical diagrams of the antitubercular BTZs 1 a and 1 b (BTZ043).

BTZs feature various reactive centres for nucleophilic attack. Thiols and other nucleophiles were shown to attack C7 of the 4H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazinone system, resulting in non‐enzymatic reduction of the 8‐nitro group via a von Richter rearrangement. [4] We did, however, not observe nucleophilic attack at C7 when incubating BTZs with DprE1. [5]

Recently, we showed by X‐ray crystallography that treatment of 1 a and 1 b with moist 3‐chloroperbenzoic acid unexpectedly led to the corresponding benzo[d]isothiazol‐3(2H)‐ones and their 1‐oxides, [6] instead of the anticipated corresponding BTZ sulfones and sulfoxides, [7] presumably involving nucleophilic addition of water at C2. In their search for the structure of a human plasma metabolite of 1 b, Kloss et al. found that treatment of the compound with the reducing agent NaBH4 yielded Meisenheimer complexes, which were also encountered in ex vivo studies. [8] Furthermore, they reported that reaction with the Grignard reagent CH3MgBr resulted in the 5‐ and 7‐monomethyl derivatives of 1 b. A very recent study proved the importance of electron‐deficient (nitro‐)aromatic pharmacophores in covalent DprE1 inhibitors, which showed comparable reactivity towards NaBH4. [9]

Identification of possible reaction pathways of BTZs is important for understanding and optimization of absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) characteristics and of particular interest with regard to the ongoing investigation of this compound class in medicinal chemistry, [10] pharmaceutics [11] and clinical development. [3a]

We have now (re)investigated reactions of BTZs 1 a and 1 b with CH3MgBr and the reducing agent (CH3)2S ⋅ BH3. Treatment with CH3MgBr and workup afforded doubly methylated benzothiazinone scaffolds, resulting in stable 5H‐ and 7H‐benzo[e][1,3]‐thiazines. Reactions of 1 a and 1 b with (CH3)2S ⋅ BH3 resulted in 8‐amino‐ and 8‐nitro‐6‐(trifluoromethyl)‐4H‐benzo[e][1,3]‐thiazines, demonstrating the possibility of selectively reducing the carbonyl carbon atom C4 in BTZs.

Results and Discussion

Reaction of BTZs 1 a and 1 b with CH3MgBr

BTZs 1 a and 1 b were reacted with two equivalents of CH3MgBr in THF/Et2O (Scheme 2). Upon quenching with water, the color of the reaction mixture immediately turned red. Nucleophilic additions to C5 and C7 of the BTZ scaffold occurred, which presumably led to intermediate thiazin‐4‐ol derivatives 2, 4, 6 and 8 (not isolated) after hydrolysis. Subsequent elimination of water afforded the dimethyl‐5H‐ and 7H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazine isomers 3 and 5, which were extracted from the aqueous mixture with ethyl acetate and separated by flash chromatography. Acidification of the remaining aqueous phase (pH 2–3) with dilute hydrochloric acid led to the 5‐ and 7‐methyl‐BTZs 7 and 9 as mixtures of structural isomers, as described by Kloss et al., [8] which were likewise separated by flash chromatography. An acidic reaction medium appeared to be essential for reoxidation of the BTZ system by air. Compounds 3, 5, 7 and 9 were identified by NMR spectroscopy and HRMS and in part by X‐ray crystallography. In contrast to BTZs, the 5H‐ and 7H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazines 3 and 5 exhibited a red color with an intense absorption band centered at around 500 nm in methanol (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information).

Scheme 2.

Reaction products after treatment of BTZs 1 a and 1 b with the Grignard reagent CH3MgBr, subsequent hydrolysis and dehydration (3 and 5) or air oxidation (7 and 9). Compounds 2, 4, 6 and 8 were not isolated.

The yields for the individual isolated reaction products (3, 5, 7 and 9) after treatment of 1 with CH3MgBr are within 2–11 %. These low yields are partly due to the fact that four different compounds were isolated from one reaction. If the yields of the individual products are added up, approx. 25 % of 1 is converted to the products studied. Furthermore, demanding chromatographic separations of the isomeric compounds lowered the yields, and we assume that 1 in part decomposes when treated with CH3MgBr.

Figure 1 shows the 1H NMR spectra of 3 a, 5 a, 7 a, 9 a and the parent BTZ 1 a. Those of 3 b, 5 b, 7 b, 9 b and the parent 1 b are depicted in the Supporting Information (Figure S2). Monomethylation of the benzene moiety in 7 a and 9 a caused a slight upfield shift of the remaining aromatic signal. In the 5H‐ and 7H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazines 3 a and 5 a, the resonance signals assigned to the methine hydrogen atoms at the sp 2 carbon atoms C7 and C5, occurred at higher field than the corresponding aromatic signals in the BTZs 1 a, 7 a and 9 a. The hydrogen atoms at the sp 3 carbon atoms C5 in 3 a and C7 in 5 a gave rise to quartet signals at 4.34 and 3.81 ppm. Whereas the positions of the signals assigned to the α‐H atoms of the piperidine ring remained nearly unaffected by methylation of the BTZ moiety, these signals are significantly sharper in the 5H‐ and 7H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazines 3 a and 5 a than in the BTZs 1 a, 7 a and 9 a (Figure 1). This indicates restricted rotation of the piperidine ring about the C2−Npiperidine bond in 3 a and 5 a in CDCl3 solution at room temperature.

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectra (400 MHz, CDCl3) of the 5H‐ and 7H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazines 3 a and 5 a, the monomethyl BTZs 7 a and 9 a and the parent BTZ 1 a. S denotes the residual solvent signal.

Slow diffusion of heptane into solutions of 3 a and 5 a in chloroform afforded small red needles of the compounds. X‐ray crystallography unambiguously revealed the molecular structures (Figure 2). To the best of our knowledge and based on a search of the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD), [12] these are the first structural characterizations of 5H‐ and 7H‐benzo[e]‐1,3‐thiazine heterocyclic systems. A chirality centre resulted from nucleophilic addition of the methyl group at C5 and C7 of the benzothiazine scaffold in 3 and 5. The methylations are not stereoselective. Thus, racemates were formed. This is reflected in the centrosymmetric crystal structures of 3 a and 5 a, which comprise both enantiomers. The fused bicyclic systems are not planar. C5 is located 0.293(3) Å in 3 a and 0.207(6) Å in 5 a above the mean plane through the nearly planar six‐membered 1,3‐thiazine ring (r.m.s. deviation 0.0365 Å in 3 a and 0.0225 Å in 5 a), whereas C7 lies 0.420(3) Å and 0.377(7) Å below this plane in 3 a and 5 a, respectively. Table 1 compares selected bond lengths of the dearomatized benzothiazine system for both structures. The C−S bond lengths are consistent with Csp 2−S single bond character, and the C2−N3 bond lengths are as expected for a Csp 2=N double bond. The C4−C4A, C6−C7 (in 3 a) or C5−C6 (in 5 a) and C8−C8A bond lengths indicate Csp 2=Csp 2 double bond character. [13] The appended piperidine ring adopts a low energy chair conformation in both 3 a and 5 a with some minor deviations from ideal tetrahedral angles, which can be attributed to the planar structure at N1.

Figure 2.

Molecular structures of 3 a (top) and 5 a (bottom) in the crystal, showing the R enantiomer in both cases. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50 % probability level. Hydrogen atoms are represented by small spheres of arbitrary radius. The minor part of the rotationally disordered trifluoromethyl group (ca. 3 %) in 5 a is omitted clarity (see Figure S3 in the Supporting Information). Colour scheme: C grey, H white, N blue, O red, S yellow.

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths (Å) for 3 a, 5 a and 10 a.

|

|

3 a |

5 a |

10 a |

|---|---|---|---|

|

C2−S1 |

1.7581(18) |

1.775(4) |

1.8095(13) |

|

C8A−S1 |

1.7546(18) |

1.752(4) |

1.7635(13) |

|

C2−N3 |

1.329(2) |

1.321(5) |

1.2748(17) |

|

C4−N3 |

1.339(2) |

1.344(5) |

1.4635(16) |

|

C4−C4A |

1.407(2) |

1.395(5) |

1.5007(17) |

|

C4A−C5 |

1.528(2) |

1.454(5) |

1.3890(18) |

|

C5−C6 |

1.508(3) |

1.332(6) |

1.3927(18) |

|

C6−C7 |

1.331(3) |

1.508(5) |

1.3851(18) |

|

C7−C8 |

1.441(3) |

1.515(5) |

1.3883(18) |

|

C8−C8A |

1.414(2) |

1.393(5) |

1.3997(17) |

For enantiopure 1 b, non‐stereoselective double methylation resulted in a mixture of RS and SS diastereomers in 3 b and 5 b. We should note that the diastereomers of 3 b and 5 b could neither be distinguished by room temperature 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, routine HPLC analysis, nor be separated by flash chromatography. This is likely due to the high degree of similarity in the molecular structures. Compound 3 b was structurally characterized by X‐ray crystallography. The asymmetric unit comprises four molecules (Sohncke space group P1; Z, Z′=4). [14] There are two pairs of RS and SS diastereomers, each related by a pseudo centre of symmetry. The Platon/ADDSYM routine calculates 95 % fit for the pseudo symmetry. [15] The absolute structure assignment was inferred from the known S configuration of the methyl‐dioxolan group in the starting material 1 b (Scheme 1) and was verified by a Flack x parameter close to zero. [16] Figure 3 depicts the pseudo centrosymmetric arrangement of unique molecules 1 (RS configuration) and 2 (SS configuration) in the crystal. A displacement ellipsoid plot for molecules 3 and 4 can be found in the Supporting Information (Figure S4). The crystal of 3 b is thus a co‐crystal of diastereomers, indicating that the diastereomers of 3 b are also not easily if at all separable by crystallization. A similar situation was previously encountered in the crystal structure of the corresponding benzisothiazolinone 1‐oxide derived from 1 b, where oxidation led to a second centre of chirality at the sulfur atom. [6] Structural parameters of the 5H‐benzo[e]‐1,3‐thiazine heterocyclic system in 3 b are similar to those in 3 a. The piperidine ring exhibits a chair conformation in all four distinct molecules. In molecule 4, positional disorder of the methyl‐dioxolan group, resulting from an approximate 180° rotation of the side chain about the C2−Npiperidine formal single bond, is encountered (see Figure S4 in the Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

Part of the asymmetric unit of 3 b. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50 % probability level. Hydrogen atoms are represented by small spheres of arbitrary radius. For the sake of clarity only unique molecules 1 and 2 (as indicated by the number after the underscore) are depicted (for molecules 3 and 4, see Supporting information). Colour scheme: C grey, H white, N blue, O red, S yellow.

The structure of 7 b was likewise confirmed by X‐ray crystallography (Figure 4). Compound 7 b crystallizes with two diastereomeric conformers in the asymmetric unit, which are related by pseudo inversion symmetry (96 % fit, as calculated with Platon/ADDSYM [15] ). An approximate 180° rotation about the C2BTZ−Npiperidine formal single bond interconverts the two diastereometic conformers. The six‐membered ring of the 1,3‐thiazinone moiety exhibits a slight boat shape and, as expected, the piperidine ring adopts a low‐energy chair conformation. The plane of the nitro group and the mean plane of the benzene ring are inclined at 18.10° in molecule 1 and 17.95° in molecule 2. The structure of 7 b is isomorphous with that of the parent compound 1 b, which has been described in detail elsewhere. [17]

Figure 4.

Displacement ellipsoid plot of 7 b (50 % probability level). Hydrogen atoms are represented by small spheres of arbitrary radius. The number after the underscore indicates the crystallographically unique molecules 1 and 2. Colour scheme: C grey, H white, N blue, O red, S yellow.

In order to study the influence of methylation and dearomatization of the benzothiazinone scaffold on antimycobacterial properties, mycobacterial growth inhibition assays were performed as summarized in Table 2. Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, we found higher MIC90 values in vitro for the monomethyl BTZs 7 a and 9 a than for the parent compound 1 a. Against Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2 155, a fast‐growing mycobacterium and model for the pathogen M. tuberculosis, [18] 7 a and 9 a were found to be inactive. The parent 1 a inhibits growth of M. smegmatis mc2 155. Consistent with literature data, [19] the monomethyl BTZs 7 b and 9 b, derived from 1 b (BTZ043), were found to be potent antitubercular agents, albeit likewise less active than the parent 1 b. In contrast to 7 a and 9 a, 7 b and 9 b still display activity against M. smegmatis mc2. This suggests that the side chain appended to C2 of the benzothiazinone scaffold appears to have a crucial bearing on the in vitro antimycobacterial activity also for the monomethyl−BTZs. For both 1 a and 1 b it was observed that in particular the introduction of a methyl group in the 5‐position of the benzothiazinone scaffold decreases in vitro activity against both mycobacterial strains.

Table 2.

In vitro activity (MIC90 in μM) of the compounds studied against M. smegmatis mc2 155 and M. tuberculosis H37Rv.

|

|

M. smegmatis mc2 155 |

M. tuberculosis H37Rv |

|---|---|---|

|

1 a |

12.5 |

0.6 |

|

3 a |

>100 |

>100 |

|

5 a |

>100 |

>100 |

|

7 a |

>100 |

16.8 |

|

9 a |

>100 |

8.4 |

|

1 b (BTZ043) |

0.01 |

0.007 |

|

3 b |

100 |

– [a] |

|

5 b |

25 |

– [a] |

|

7 b |

5 |

1.1 [b] |

|

9 b |

0.3 |

0.02 [b] |

|

10 a |

>100 |

– [a] |

|

11 a |

>100 |

– [a] |

|

10 b |

<0.39 |

– [a] |

|

11 b |

>100 |

– [a] |

[a] Not determined. [b] Data taken from. [19]

The 5H‐ and 7H‐benzo[e][1,3]thiazines 3 and 5 were subjected to in vitro activity testing against M. smegmatis mc2 155. We found a low level of antimycobacterial activity for 5 b (MIC90 25 μM), whereas 3 a (>100 μM), 3 b (100 μM) and 5 a (>100 μM) were found be inactive. It is interesting to note that in the crystal structure of the M. tuberculosis DprE1 in complex with PBTZ169 (PDB code: 4NCR, resolution 1.88 Å) a water molecule links the BTZ carbonyl oxygen atom in the 4‐position to a backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of a leucine moiety through hydrogen bonding. [20] Similarly, in the crystal structures of the M. tuberculosis DprE1 in complex with related BTZs, a hydrogen‐bonded water molecule joins the BTZ carbonyl oxygen atom to the backbone carbonyl atom of a tyrosine moiety. [5] The absence of the carbonyl group at C4 in 3 and 5 as hydrogen bond acceptor thus likely contributes to the considerably lower antimycobacterial in vitro activity compared with the parent BTZs 1 a and 1 b.

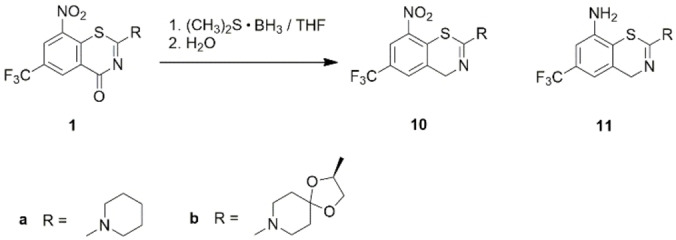

Reaction of BTZs 1 a and 1 b with (CH3)2S ⋅ BH3

Treatment of BTZs 1 a and 1 b with the reducing agent (CH3)2S ⋅ BH3 in THF [21] and subsequent aqueous workup surprisingly resulted in selective reduction of the BTZ carbonyl group in 4‐position to a methylene group with the 8‐nitro benzo[e][1,3]thiazines 10 as major products (Scheme 3). The 8‐nitro group partially underwent reduction under these reaction conditions affording the corresponding benzo[e][1,3]thiazine‐8‐amines 11 as minor products, which were separated by flash chromatography. Compounds 10 and 11 were characterized by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy and HRMS. In addition, the structure of 10 a was proven by X‐ray crystallography (Figure 5). Selected bond lengths are included in Table 1. As observed previously for two rare examples of structurally characterized benzo[e][1,3]thiazines, [22] the heterocyclic benzothiazine system is distinctly non‐planar as a result of a marked boat shape of the 1,3‐thiazine ring with C2 and N3 being displaced from the mean plane through the fused benzene ring by 1.023(2) and 0.956(2) Å, respectively. The nitro group is tilted out of the benzene ring mean plane by 22.1(1)°.

Scheme 3.

Reaction products after treatment of BTZs 1 a and 1 b with the reducing agent (CH3)2S ⋅ BH3 and subsequent hydrolysis.

Figure 5.

Molecular structure of 10 a in the crystal. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50 % probability level. Hydrogen atoms are represented by small spheres of arbitrary radius. Colour scheme: C grey, H white, N blue, O red, S yellow.

The antimycobacterial activity of the decarbonylated BTZs 10 and 11 was evaluated in vitro against M. smegmatis mc2 155 (Table 2). No growth inhibition was observed for 10 a up to a concentration of 100 μM despite the presence of the 8‐nitro group necessary for covalent binding to DprE1. This observation confirmed the assumption that the 4‐carbonyl group as hydrogen bonding acceptor site is also essential for efficient inhibition of DprE1 (vide supra). For 10 b, however, no bacterial growth of M. smegmatis up to a concentration of 0.39 μM was observed under the same conditions. We ascribe this observation to trace reoxidation of 10 b to the parent BTZ 1 b, which was also noticeable in the 1H NMR spectrum (Figure S5 in the Supporting Information). One might expect the same for 10 a, but the activity of the parent BTZ 1 a against M. smegmatis is some orders of magnitude lower than that of 1 b . Thus, trace amounts of 10 a could remain undetected in the in vitro assay used. Compounds 11 a and 11 b showed no activity against M. smegmatis. Apart from the absence of the 4‐carbonyl group as in 10 a and 10 b, 11 a and 11 b also lack the 8‐nitro group crucial for covalent binding to DprE1. Loss of antimycobacterial activity was found previously for BTZ‐8‐amines, as the amino group is not activated to the reactive nitroso group by the enzyme.[ 5 , 20 , 23 ]

Conclusions

The present study provides insight into the reactivity of the carbonyl group in 4‐position of the BTZ scaffold of the two antitubercular 8‐nitro BTZs 1 a and 1 b (BTZ043). Reaction with the Grignard reagent CH3MgBr and the reducing agent (CH3)S ⋅ BH3 reveals previously unobserved reactivity of BTZs. It has been shown that nucleophilic attack not only occurs at the electron‐deficient benzene ring but also at the carbonyl carbon atom of the thiazinone ring. Treatment with CH3MgBr afforded methylated and/or dearomatized BTZ derivatives 3, 5, 7 and 9. Decarbonylation to the 4‐methylene derivatives in part with concomitant reduction of the 8‐nitro group was observed when the BTZs were reacted with (CH3)2S ⋅ BH3. The reductive chemical transformations encountered indicate possible points of attack for BTZs during drug metabolism. Consistent with previous findings, methyl−BTZs 7 and 9 remain active against mycobacteria in vitro, whereas dearomatization of BTZs 1 to 3 and 5 and decarbonylation to 10 renders these derivatives inactive against M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis. In line with known structures of DprE1−BTZ complexes, this supports the view that the BTZ 4‐carbonyl group is a hydrogen bond acceptor crucial for effective inhibition of the mycobacterial enzyme DprE1. Concomitantly, the carbonyl group also increases the electrophilicity of C‐8 and the ease of reduction of the nitro group, again supporting the molecular mechanism leading to activity.

Experimental Section

Experimental procedures for the syntheses, NMR spectroscopic and HRMS characterizations, HPLC analyses (Figures S5–S53) and in vitro antimycobacterial testing of the compounds studied can be found in the Supporting Information.

X‐ray crystallography

Details of the X‐ray intensity data collections and crystal structure refinements can be found in the Supporting Information. CCDC 2126176‐2126180 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Crystal data for 3 a (CCDC 2126176): C16H18F3N3O2S, M r=373.39, T=100(2) K, λ=0.71073 Å, orthorhombic, space group Pccn, a=11.5451(6), b=16.7979(9), c=16.972(1) Å, V=3291.4(3) Å3, Z=8, ρ calc=1.507 mg m−3, μ=0.244 mm−1, F(000)=1552, crystal size 0.06×0.02×0.01 mm, θ range=2.14–33.23°, reflections collected/unique=115254/6310, (R int=0.1258), 228 parameters, S=1.011, R1[I>2σ(I)]=0.0542, wR2=0.1420, Δρ max, Δρ min=0.27, −0.46 eÅ−3.

Crystal data for 3 b (CCDC 2126177): C19H22F3N3O4S, M r=445.45, T=100(2) K, λ=1.54178 Å, triclinic, space group P1, a=12.8795(16), b=13.3094(16), c=14.9933(19) Å, α=99.359(6), β=106.571(5), γ=118.865(5)°, V=2014.5(4) Å3, Z=4, ρ calc=1.469 mg m−3, μ=1.970 mm−1, F(000)=928, crystal size 0.12×0.08×0.05 mm, θ range=3.29–79.88°, reflections collected/unique=134524/16318, (R int=0.0617), 1132 parameters, 120 restraints, Flack x parameter=0.091(17), S=1.096, R1[I>2σ(I)]=0.0572, wR2=0.1691, Δρ max, Δρ min=0.72, −0.28 eÅ−3.

Crystal data for 5 a (CCDC 2126178): C16H18F3N3O2S, M r=373.39, T=100(2) K, λ=1.54178 Å, triclinic, space group P‐1, a=5.6943(8), b=10.1985(13), c=14.0461(18) Å, α=97.388(6), β=91.269(6), γ=90.090(6)°, V=808.73(19) Å3, Z=2, ρ calc=1.533 mg m−3, μ=2.236 mm−1, F(000)=388, crystal size 0.60×0.02×0.02 mm, θ range=3.17–77.41°, reflections collected/unique=37652/3347, (R int=0.0418), 238 parameters, 45 restraints, S=1.058, R1[I>2σ(I)]=0.0685, wR2=0.2069, Δρ max, Δρ min=1.01, −0.37 eÅ−3.

Crystal data for 7 b (CCDC 2126179): C18H18F3N3O5S, M r=445.41, T=100(2) K, λ=1.54178 Å, triclinic, space group P1, a=6.3523(7), b=9.8015(11), c=15.5546(18) Å, α=83.740(4), β=78.303(3), γ=84.947(3)°, V=940.53(18) Å3, Z=2, ρ calc=1.573 mg m−3, μ=2.155 mm−1, F(000)=460, crystal size 0.14×0.05×0.03 mm, θ range=2.91–80.95°, reflections collected/unique=85037/7780, (R int=0.042), 546 parameters, 3 restraints, Flack x parameter=0.082(17), S=1.058, R1[I>2σ(I)]=0.0293, wR2=0.0793, Δρ max, Δρ min=0.21, −0.33 eÅ−3.

Crystal data for 10 a (CCDC 2126180): C14H14F3N3O2S, M r=345.34, T=100(2) K, λ=0.71073 Å, monoclinic, space group P21/n, a=13.1787(14), b=4.3790(5), c=25.355(3) Å, β=99.312(8), V=1443.9(3) Å3, Z=4, ρ calc=1.589 mg m−3, μ=0.271 mm−1, F(000)=712, crystal size 0.12×0.11×0.07 mm, θ range=2.68–35.06°, reflections collected/unique=32929/6369, (R int=0.0700), 208 parameters, S=1.021, R1[I>2σ(I)]=0.0461, wR2=0.1211, Δρ max, Δρ min=0.59, −0.75 eÅ−3.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Christian W. Lehmann for providing access to the X‐ray diffraction facility at the Max‐Planck‐Institut für Kohlenforschung (Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany), Heike Schucht and Elke Dreher for technical assistance with the X‐ray intensity data collections, and Dr. Christian Ihling and Antje Herbrich‐Peters for recording the HRMS and UV/Vis spectra. Thanks are due to Dr. Jens‐Ulrich Rahfeld and Dr. Nadine Taudte for providing and maintaining the biosafety level 2 laboratory. A. R. would like to thank Professor Yossef Av‐Gay for his support. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Dedicated to Professor Wolfgang Seidel on the occasion of his 90th birthday.

A. Richter, R. W. Seidel, J. Graf, R. Goddard, C. Lehmann, T. Schlegel, N. Khater, P. Imming, ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202200021.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Makarov V., Manina G., Mikusova K., Möllmann U., Ryabova O., Saint-Joanis B., Dhar N., Pasca M. R., Buroni S., Lucarelli A. P., Milano A., De Rossi E., Belanova M., Bobovska A., Dianiskova P., Kordulakova J., Sala C., Fullam E., Schneider P., McKinney J. D., Brodin P., Christophe T., Waddell S., Butcher P., Albrethsen J., Rosenkrands I., Brosch R., Nandi V., Bharath S., Gaonkar S., Shandil R. K., Balasubramanian V., Balganesh T., Tyagi S., Grosset J., Riccardi G., Cole S. T., Science 2009, 324, 801–804; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b.I. Rudolph, P. Imming, A. Richter, DE102014012546, Martin-Luther-Universitaet Halle-Wittenberg, Germany, 2014.

- 2. Makarov V., Mikušová K., Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2269. [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Shetye G. S., Franzblau S. G., Cho S., Transl. Res. 2020, 220, 68–97; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Chauhan A., Kumar M., Kumar A., Kanchan K., Life Sci. 2021, 274, 119301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tiwari R., Moraski G. C., Krchňák V., Miller P. A., Colon-Martinez M., Herrero E., Oliver A. G., Miller M. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3539–3549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Richter A., Rudolph I., Möllmann U., Voigt K., Chung C.-W., Singh O. M. P., Rees M., Mendoza-Losana A., Bates R., Ballell L., Batt S., Veerapen N., Fütterer K., Besra G., Imming P., Argyrou A., Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eckhardt T., Goddard R., Lehmann C., Richter A., Sahile H. A., Liu R., Tiwari R., Oliver A. G., Miller M. J., Seidel R. W., Imming P., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2020, 76, 907–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tiwari R., Miller P. A., Cho S., Franzblau S. G., Miller M. J., ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 128–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kloss F., Krchnak V., Krchnakova A., Schieferdecker S., Dreisbach J., Krone V., Möllmann U., Hoelscher M., Miller M. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 2187–2191; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 2220–2225. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu R., Markley L., Miller P. A., Franzblau S., Shetye G., Ma R., Savková K., Mikušová K., Lee B. S., Pethe K., Moraski G. C., Miller M. J., RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 62–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Zhang G., Howe M., Aldrich C. C., ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 348–351; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Zhang G., Sheng L., Hegde P., Li Y., Aldrich C. C., Med. Chem. Res. 2021, 30, 449–458; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Liu L., Kong C., Fumagalli M., Savková K., Xu Y., Huszár S., Sammartino J. C., Fan D., Chiarelli L. R., Mikušová K., Sun Z., Qiao C., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 208, 112773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patel A., Redinger N., Richter A., Woods A., Neumann P. R., Keegan G., Childerhouse N., Imming P., Schaible U. E., Forbes B., Dailey L. A., J. Controlled Release 2020, 328, 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Groom C. R., Bruno I. J., Lightfoot M. P., Ward S. C., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 2016, 72, 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Allen F. H., Watson D. G., Brammer L., Orpen A. G., Taylor R., in International Tables for Crystallography Volume C: Mathematical, physical and chemical tables (Ed.: Prince E.), Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2004, pp. 790–811. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Steed K. M., Steed J. W., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2895–2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spek A. L., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 2009, 65, 148–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Flack H., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1983, 39, 876–881. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Richter A., Patzer M., Goddard R., Lingnau J. B., Imming P., Seidel R. W., J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1248, 131419. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sundarsingh T. J. A., Ranjitha J., Rajan A., Shankar V., J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1255–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.F. Kloss, S. Schieferdecker, A. Brakhage, J. Dreisbach, M. J. Miller, U. Moellmann, K. P. Wojtas, WO 2018/055048 Al, Leibniz-Institut fuer Naturstoff-Forschung und Infektionsbiologie e.V. Hans-Knoell Institut HKI, Germany, 2018.

- 20. Makarov V., Lechartier B., Zhang M., Neres J., van der Sar A. M., Raadsen S. A., Hartkoorn R. C., Ryabova O. B., Vocat A., Decosterd L. A., Widmer N., Buclin T., Bitter W., Andries K., Pojer F., Dyson P. J., Cole S. T., EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 372–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.

- 21a. Whiting A. L., Dubicki K. I., Hof F., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 6802–6810; [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Powers J. P., Li S., Jaen J. C., Liu J., Walker N. P. C., Wang Z., Wesche H., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 2842–2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.

- 22a. Sathunuru R., Zhang H., Rees C. W., Biehl E., Heterocycles 2005, 65, 1615–1628; [Google Scholar]

- 22b. Sandhya N. C., Chandra, Suresha G. P., Lokanath N. K., Mahendra M., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E 2015, 71, o74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.

- 23a. Tiwari R., Miller P. A., Chiarelli L. R., Mori G., Šarkan M., Centárová I., Cho S., Mikušová K., Franzblau S. G., Oliver A. G., Miller M. J., ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 266–270; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23b. Trefzer C., Škovierová H., Buroni S., Bobovská A., Nenci S., Molteni E., Pojer F., Pasca M. R., Makarov V., Cole S. T., Riccardi G., Mikušová K., Johnsson K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 912–915; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23c. Trefzer C., Rengifo-Gonzalez M., Hinner M. J., Schneider P., Makarov V., Cole S. T., Johnsson K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 13663–13665; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23d. Neres J., Pojer F., Molteni E., Chiarelli L. R., Dhar N., Boy-Röttger S., Buroni S., Fullam E., Degiacomi G., Lucarelli A. P., Read R. J., Zanoni G., Edmondson D. E., De Rossi E., Pasca M. R., McKinney J. D., Dyson P. J., Riccardi G., Mattevi A., Cole S. T., Binda C., Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 150ra121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.