Abstract

Catalytic stereoselective additions with maleimides are useful one‐step reactions to yield chiral succinimides, molecules that are widespread among therapeutically active compounds but challenging to prepare when the maleimide is C‐substituted. We present the tripeptide H‐Pro‐Pro‐Asp‐NHC12H25 as a catalyst for conjugate addition reactions between aldehydes and C‐substituted maleimides to form succinimides with three contiguous stereogenic centers in high yields and stereoselectivities. The peptidic catalyst is so chemoselective that no protecting group is needed at the imide nitrogen of the maleimides. Derivatization of the succinimides was straightforward and provided access to chiral pyrrolidines, lactones, and lactams. Kinetic studies, including a Hammett plot, provided detailed insight into the reaction mechanism.

Keywords: conjugate additions, organocatalysis, peptides, stereoselectivity, succinimides

Challenging transformation A peptide catalyst facilitated access to succinimides and downstream heterocycles with three contiguous stereogenic centers via stereo‐, chemo‐ and regioselective conjugate addition reaction between aldehydes and C‐substituted maleimides.

Substituted succinimides are common among natural products, pharmaceuticals, and other small molecules with biological functions (Scheme 1a).[ 1 , 2 ] Straightforward syntheses towards this motif are therefore important, and different routes have been established.[ 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ] Particularly attractive are catalytic, stereoselective methods using purely organic catalysts.[ 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 ] These organocatalytic routes offer access to fused bi‐ or tricyclic succinimides as well as mono‐C‐substituted succinimides (Scheme 1b). The synthesis of di‐C‐substituted chiral succinimides that are not part of a bicyclic system has been significantly more difficult. Only recently, elegant photoinduced radical reactions, NHC‐catalyzed cycloadditions, and metal‐organic reactions enabled their synthesis.[ 6 , 7 ] The stereoselective organocatalytic conjugate addition of aldehydes to C‐substituted maleimides using chiral amine‐based catalysts presents an alternative method but has not been achieved so far. This reaction would yield disubstituted succinimides bearing three contiguous stereogenic centers in one step (Scheme 1c).

Scheme 1.

a) Examples of succinimide‐based therapeutics. b) Previous work towards succinimides using i) cyclizations and ii) C−C bond formation reactions with C‐unsubstituted maleimides. c) This work on stereoselective secondary amine catalyzed conjugate addition reaction between aldehydes and C‐substituted maleimides with challenges to control d) chemoselectivity, e) regioselectivity, and f) stereoselectivity.

Several examples showed that chiral secondary amines can catalyze reactions between aldehydes with maleimide or maleimides bearing a protecting group at the imide nitrogen (Scheme 1b).[ 8 , 9 ] The only example for a reaction between an aldehyde and a C‐substituted maleimide used not an organocatalyst but a Rh‐catalyst and yielded succinimides with a quaternary stereogenic center. [4] Possible reasons for the lack of catalytic methods for the target reaction are the necessity to control a) chemoselectivity, b) regioselectivity, and c) stereoselectivity (Scheme 1d–f). The chemoselectivity challenge arises from the nucleophilicity of the imide‐nitrogen that reacts reversibly with carbonyl compounds (Scheme 1d). Hence protecting groups at N are common for reactions involving maleimides and require an, often cumbersome, deprotection step.[ 8 , 9 , 10 ] Regioisomers can arise from nucleophilic attack at either of the two carbons of C‐substituted maleimides (Scheme 1e). In addition, the absolute and relative configuration of the three stereogenic centers needs to be controlled (Scheme 1f).

Previously, we showed that the peptide H‐dPro‐Pro‐Asn‐NH2 (1 a) is a highly stereoselective catalyst for the conjugate addition reaction of aldehydes to unsubstituted maleimide. [11] Furthermore, we showed that suitable peptide catalysts of the Pro‐Pro‐Xaa type can be developed for reactions between aldehydes and mono‐ as well as disubstituted nitroolefins.[ 12 , 13 ] Building on these data, we envisioned that peptidic catalysts [14] could overcome the challenges associated with C‐substituted maleimides and provide access to disubstituted succinimides through the controlled activation of both the aldehyde and the maleimide followed by stereoselective C−C bond formation. We perceived that the modularity of peptides, which allows for facile variation of their structural and functional properties, would be key for the development of a chemo‐, regio‐ and stereoselective peptidic catalyst.

Herein, we present the peptide H‐Pro‐Pro‐Asp‐NHC12H25 as a catalyst for the conjugate addition of aldehydes to C‐substituted maleimides. We highlight the value of the succinimide products for organic synthesis by derivatization into pyrrolidines, lactams, and lactones. Furthermore, kinetic studies provided critical insights into the reaction mechanism of this peptide catalyzed conjugate addition reaction.

We started our investigations by reacting n‐butanal (2 a) with 3‐phenylmaleimide (3 a) in the presence of H‐dPro‐Pro‐Asn‐NH2 (1 a), the catalyst that had previously been developed for reactions with unsubstituted maleimide. [11] Conditions optimal for unsubstituted maleimide, resulted in good conversion to succinimide 4 a but with poor diastereo‐ and enantioselectivity (d.r. 40 : 7 : 35 : 18, 23 % ee; Table 1, entry 1). Variations of the amino acids and their absolute configuration showed that H‐Pro‐Pro‐Asp‐NH2 (1 b), an analog with all l‐configured amino acids and an aspartic acid (Asp) at the C‐terminus, is significantly more enantioselective than the parent catalyst (Table 1, entry 2; Table S1). This result is noteworthy since tripeptidic Pro‐Pro‐Xaa‐type catalysts with a dll‐configuration are optimal for related reactions with C‐unsubstituted maleimide as well as nitroolefins.[ 11 , 12 , 13 , 16 , 17 ] This finding highlights how the modularity of peptidic catalysts allows for tailoring of their structural properties to enable reactions with difficult substrates.

Table 1.

Conjugate addition reaction between n‐butanal and 3‐phenylmaleimide catalyzed by peptides 1 a–c.

|

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

entry |

Catalyst |

Solvent |

Conv. [%][a] |

d.r.[a] (A : B : C : D) |

ee[b] [%] |

|

1 |

H‐dProProAsn‐NH2 1 a |

CHCl3/ i PrOH 1 : 1[c] |

93 |

40 : 7 : 35 : 18 |

23 |

|

2 |

H‐ProProAsp‐NH2 1 b |

CHCl3/ i PrOH 1 : 1[c] |

61 |

61 : 8 : 23 : 8 |

84 |

|

3 |

H‐ProProAsp‐NH2 1 b |

1,4‐dioxane[d] |

38 |

89 : 8 : 1 : 3 |

99 |

|

4 |

H‐ProProAsp‐NHC12H25 1 c |

1,4‐dioxane[d] |

54[e] |

86 : 9 : 1 : 4 |

98 |

[a] Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the crude reaction mixture. [b] Determined by chiral stationary phase HPLC analysis. Enantioselectivity of diastereoisomer A. [c] [3 a]=0.5 M. [d] [3 a]=0.25 M. [e] Isolated yield. TFA=trifluoroacetic acid, NMM=N‐methylmorpholine.

The stereoselectivity could be further improved by performing the reaction at a lower concentration (0.25 M instead of 0.5 M of 3 a) and changing the solvent of the reaction (Table S3). The highest stereoselectivity was obtained in 1,4‐dioxane (d.r. 89 : 8 : 1 : 3, 99 % ee) but at the expense of low conversion due to limited solubility of peptide 1 b (Table 1, entry 3). We, therefore, attached an alkyl chain at the C‐terminus (1 c), a modification that improved the solubility and the conversion without affecting the stereoselectivity (Table 1, entry 4). [18]

With optimized reaction conditions in hand, we explored the scope of the peptide catalyzed 1,4‐addition by reacting different combinations of aldehydes 2 a–2 g and substituted maleimides 3 a–3 k in the presence of 1 mol % or 5 mol % of peptide 1 c at room temperature (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Scope of the conjugate addition between aldehydes and substituted maleimides catalyzed by peptidic catalyst 1 c.[a] Yields correspond to the isolated addition products as a mixture of diastereoisomers after a reaction time of 24 h unless otherwise noted. The d.r. and ee values were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy and chiral stationary phase HPLC, respectively. ee reported of diastereoisomer A (see below and the SI for the assignment of the absolute and relative configuration of all stereoisomers).

Pleasingly, a broad scope of aromatic maleimides with para‐ and meta‐ substituents on the phenyl substituent were well tolerated, and succinimides 4 a–4 i were isolated in good yields (54 %‐quant.) and with high optical purity (84 %–99 % ee, d.r. 72 : 13 : 6 : 9 – 86 : 9 : 1 : 4). A longer reaction time (72 h) was required for the p‐fluorophenyl substituted succinimide 4 b to form, whereas reaction times of 1–3 h and/or a catalyst loading of 1 mol % sufficed to obtain succinimides bearing trifluoromethyl, cyano, nitro, and ester substituents (4 e–g, 4 l, 4 p). Reactions with maleimides bearing aliphatic or aromatic substituents with groups in the ortho‐position were problematic (4 j), but aldehyde variations were feasible (4 k–4 p). Even functional groups, such as ester (4 o, 4 l) – including an activated pentafluorophenylester – and alkene moieties (4 p) at the maleimide or the aldehyde allowed to access the succinimides in very good yields and stereoselectivities.

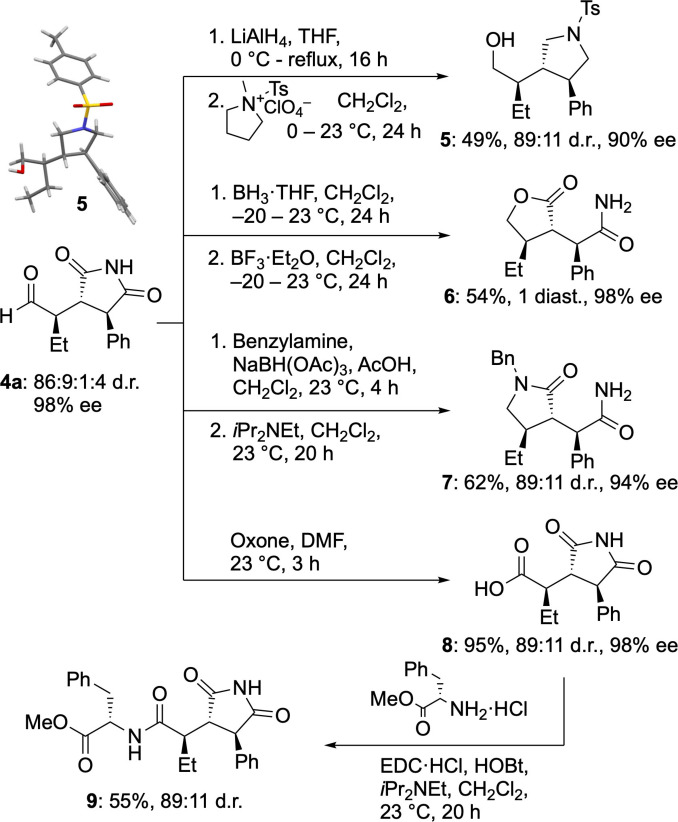

To probe the synthetic utility of the obtained conjugate addition products, we explored the derivatization of succinimide 4 a (Scheme 3). Reduction of the aldehyde and succinimide moieties and subsequent tosylation yielded pyrrolidine 5. This derivative enabled access to crystals suitable for X‐ray analysis, which allowed for the assignment of the relative and absolute configurations of the stereogenic centers (Scheme 3, top left). [19]

Scheme 3.

Derivatization of conjugate addition product 4a and crystal structure of pyrrolidine 5.

Reduction and reductive amination of aldehyde 4 a provided lactone 6 and lactam 7, respectively, in good yields. Furthermore, oxidation of aldehyde 4 a to the corresponding carboxylic acid 8 and coupling to l‐phenylalanine methyl ester hydrochloride progressed seamlessly to yield compound 9. All transformations proceeded with retention of the diastereo‐ and enantioselectivity and allowed for the isolation of one or a mixture of two major diastereoisomers (Scheme 3).

Next, we aimed at insight into the reaction mechanism and started these studies by performing a linear free‐energy relationship analysis (Hammett study; Figure 1). We used in situ infrared (IR) spectroscopy as a noninvasive method to monitor the reaction progress of the reactions between butanal and maleimides 3 a–3 i bearing substituents with different electronic properties. The rates were determined by following the appearance of the distinctive signal for the C−N bond of the succinimide functionality (ν max=1190 cm−1).

Figure 1.

Hammett linear free‐energy plot of the conjugate addition reaction between butanal and different succinimides catalyzed by peptide 1 c (ρ=2.29, R 2=0.85).

The Hammett plot revealed that electron‐poor maleimides undergo the conjugate addition reaction faster than their more electron‐rich analogs (Figure 1). The positive slope indicates a buildup of a partial negative charge in the transition state of the rate‐limiting step of the reaction. [20]

This finding supports a mechanism involving the reaction of an enamine intermediate (I), formed by reaction between the catalyst and the aldehyde, with the maleimide to an enolate‐type intermediate (II) that is then hydrolyzed to the product and the catalyst (Scheme 4). The Hammett study also indicates that the C−C bond formation that generates the enolate‐type intermediate is rate‐limiting.

Scheme 4.

Plausible catalytic cycle of the conjugate addition reaction between aldehydes and C‐substituted maleimides catalyzed by 1 c.

Next, we carried out “same excess” experiments as reported by Blackmond [21] to elucidate whether catalyst deactivation occurs during the reaction. We used the conjugate addition reaction between butanal and the p‐CF3 substituted phenylmaleimide (3 e) with 5 mol % of catalyst 1 c since this reaction reached complete conversion within 2 h, a practical time frame for kinetic studies (Scheme 2). The results show that H‐Pro‐Pro‐Asp‐NHC12H25 (1 c) is not deactivated during the reaction (Figures S3 and S4), a finding that highlights the chemoselectivity and robustness of the peptide catalyst towards functional groups that could interfere by, for example, H‐bonding with the catalyst. Further, we excluded non‐linear effects by performing the reaction in the presence of 1 c and its enantiomer in different ratios (Figure S13).

For further mechanistic insight, we measured the reaction order of all reaction components with “different excess” experiments (Figure S5).[ 21 , 22 ] The data revealed a rate order of 0.2 for aldehyde 2 a, 1.4 for maleimide 3e, and 1 for catalyst 1 c. We also evaluated the role of water in the reaction and found a rate order of zero. These kinetic data are consistent with the catalytic cycle shown in Scheme 4. This cycle starts with the reaction of the secondary amine of peptidic catalyst 1 c with the aldehyde to form enamine intermediate I. The enamine then undergoes a regio‐ and stereoselective reaction with the maleimide to generate the stereogenic centers at C(2) and C(3). Protonation of enolate‐type intermediate II, likely by intramolecular proton transfer from the carboxylic acid of the Asp residue, generates the stereogenic center at C(4). Finally, hydrolysis of the iminium intermediate III releases the product and regenerates catalyst 1 c. The observed rate order of 1.4 for the maleimide implies that the C−C bond formation is the rate‐determining step and that maleimide participates in another reaction, a finding consistent with off‐cycle hemiaminal formation. [23]

In conclusion, we have developed an effective peptide catalyst for the conjugate addition reaction between aldehydes and C‐substituted maleimides. This reaction provides succinimides with three contiguous stereogenic centers that had not been accessible in a catalytic, one‐step reaction before. The reaction proceeds without the need for a protecting group at the imide nitrogen, and the scope includes substrates with moieties such as ester groups. These findings underscore the chemoselectivity and robustness of the peptidic catalyst towards functional groups that could interfere with the catalysis. The succinimides could be easily transformed into chiral pyrrolidines, lactones, and lactams, which highlights their versatility as building blocks to access structural motives that are widespread in therapeutically active compounds. Mechanistic studies that included a Hammett linear free‐energy analysis revealed the C−C bond formation as the rate‐determining step. Overall, the study highlights the value of the structural and functional modularity of peptides to adapt to the needs of challenging substrates and enable chemo‐ and stereoselective catalytic transformations.

Experimental

Full details on synthetic methods, along with analytical data, NMR spectra, and crystal structures, can be found in the Supporting Information. Deposition Numbers 1511495 (for 5), 2101701 (for 7‐diastereoisomer), and 2101705 (for 10‐diastereoisomer) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 200020_188729). We thank Dr. Nils Trapp and Michael Solar from the Small Molecule Crystallography Center (SMoCC) of ETH Zurich for recording the X‐Ray crystal structures and are grateful to Dr. Mattia Monaco for valuable discussions. Open access funding provided by Eidgenossische Technische Hochschule Zurich.

In honor and memory of Prof. Dr. François Diederich

G. Vastakaite, C. E. Grünenfelder, H. Wennemers, Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202200215.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

- 1.For reviews, see:

- 1a. Zhao Z., Yue J., Ji X., Nian M., Kang K., Qiao H., Zheng X., Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 108, 104557–104574; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Patil M. M., Rajput S. S., Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 8–14; [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Chauhan P., Kaur J., Chimni S. S., Chem. Asian J. 2012, 8, 328–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For examples, see:

- 2a. Miller C. A., Long L. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 6256–6258; [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Trojan J., Zeuzem S., Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 2013, 22, 141–147; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Curtin M. L., Garland R. B., Heyman H. R., Frey R. R., Michaelides M. R., Li J., Pease L. J., Glaser K. B., Marcotte P. A., Davidsen S. K., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12, 2919–2923; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Needham J., Kelly M. T., Ishige M., Andersen R. J., J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 2058–2063. [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Dardennes E., Labano S., Simpkins N. S., Wilson C., Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 6380–6383; [Google Scholar]

- 3b.Z. Han‚ P. Li‚ Z. Zhang‚ C. Chen‚ Q. Wang, X.-Q. Dong, X. Zhang, ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 6214–6218;

- 3c. Schmid J., Junge T., Lang J., Frey W., Peters R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5447–5451; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 5501–5505; [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Mukherjee S., Corey E. J., Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 632–635; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3e. Zheng J., Swords W. B., Jung H., Skubi K. L., Kidd J. B., Meyer G. J., Baik M.-H., Yoon T. P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 13625–13634; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3f. Miskov-Pajic V., Willig F., Wanner D. M., Frey W., Peters R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 19873–19877; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 20045–20049; [Google Scholar]

- 3g. Chen Z.-J., Liang W., Chen Z., Chen L., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 788–793. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shintani R., Duan W. L., Hayashi T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 5628–5629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Riant O., Kagan H. B., Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 7403–7406; [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Gioia C., Hauville A., Bernardi L., Fini F., Ricci A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9236–9239; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 9376–9379; [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Soh J. Y. T., Tan C.-H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6904–6905; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5d. Dell′Amico L., Vega-Penaloza A., Cuadros S., Melchiorre P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3313–3317; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 3374–3378. [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Weber M., Frey W., Peters R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 13223–13227; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 13465–13469; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Piou T., Rovis T., Nature 2015, 527, 86–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Cuadros S., Horwitz M. A., Schweitzer-Chaput B., Melchiorre P., Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 5484–5488; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Wang L., Blümel M., Shu T., Raabe G., Enders D., Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 8033–8037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Bartoli G., Bosco M., Carlone A., Cavalli A., Locatelli M., Mazzanti A., Ricci P., Sambri L., Melchiorre P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 4966–4970; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 5088–5092; [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Zhao G. L., Xu Y. M., Sundén H., Eriksson L., Sayah M., Córdova A., Chem. Commun. 2007, 734–735; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8c. Xue F., Liu L., Zhang S. L., Dua W. H., Wang W., Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 7979–7982; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8d. Shirakawa S., Terao S. J., He R., Maruoka K., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 10557–10559; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8e. Kokotos C. G., Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 2406–2409; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8f. Torregrosa-Chinillach A., Moragues A., Pérez-Furundarena H., Chinchilla R., Gómez-Bengoa E., Guillena G., Molecules 2018, 23, 3299–3309; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8g. Ray B., Mukherjee S., Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 3292–3298; [Google Scholar]

- 8h. Sadiq A., Nugent T. C., ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 11934–11938. [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Flores-Ferrandiz J., Chinchilla R., Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2014, 25, 1091–1094; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Avila A., Chinchilla R., Gomez-Bengoa E., Najera C., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 5085–5092; [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Ma Z.-W., Liu X.-F., Liu J.-T., Liu Z.-J., Tao J.-C., Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4487–4490; [Google Scholar]

- 9d. Wei L., Chen L., Bideau F. L., Retailleau P., Dumas F., Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lonergan D. G., Deslongchamps G., Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 14041–14052. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grünenfelder C. E., Kisunzu J. K., Wennemers H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 8571–8574; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 8713–8716. [Google Scholar]

- 12.

- 12a. Wiesner M., Revell J. D., Wennemers H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 1871–1874; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 1897–1900; [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Wiesner M., Neuburger M., Wennemers H., Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 10103–10109; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12c. Möhler J. S., Schnitzer T., Wennemers H., Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 15623–15628; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12d. Schnitzer T., Budinska A., Wennemers H., Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Duschmalé J., Wennemers H., Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 1111–1120; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Kastl R., Wennemers H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7228–7232; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 7369–7373. [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Metrano A. J., Chinn A. J., Shugrue C. R., Stone E. A., Kim B., Miller S. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 120, 11479–11615; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Lewandowski B., Wennemers H., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014, 22, 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diastereoisomeric peptides, as well as other analogs of 1a–c, were also evaluated, Table S1.

- 16.

- 16a. Schnitzer T., Wennemers H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15356–15362; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Rigling C., Kisunzu J. K., Duschmalé J., Häussinger D., Wiesner M., Ebert M.-O., Wennemers H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 10829–10838; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16c. Schnitzer T., Wennemers H., J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 7633–7640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schnitzer T., Wennemers H., Synlett 2017, 28, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar]

- 18.For a previous example that used alkylation to increase the solubility of Pro-Pro-Xaa type catalysts in organic solvents, see: Nicholls L. D. M., Wennemers H., Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 17559–17564.34496089 [Google Scholar]

- 19.CCDC 1511495 (5) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

- 20.

- 20a. Hammett L. P., Chem. Rev. 1935, 17, 125–136; [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Hansch C., Leo A., Taft R. W., Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 165–195; [Google Scholar]

- 20c. Hopkinson A. C., J. Chem. Soc. B 1969, 203–205. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blackmond D. G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4302–4320; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 4374–4393. [Google Scholar]

- 22.

- 22a. Burés J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 2028–2031; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 2068–2071; [Google Scholar]

- 22b. Burés J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 16084–16087; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 16318–16321; [Google Scholar]

- 22c. Nielsen C. D.-T., Burés J., Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 348–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Of note, a cyclobutane intermediate that can occur in related reactions with nitroolefins when catalysts without an acid donor are used were not observed under the reaction conditions; Duschmalé J., Wiest J., Wiesner M., Wennemers H., Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 1312–1318. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.