Abstract

Paediatricians may face the notion of ‘virginity’ in various situations while caring for children and adolescents, but are often poorly prepared to address this sensitive topic. Virginity is a social construct. Despite medical evidence that there is no scientifically reliable way to determine virginity, misconceptions about the hymen and its supposed association with sexual history persist and lead to unethical practices like virginity testing, certificate of virginity or hymenoplasty, which can be detrimental to the health and well‐being of females of all ages. The paediatrician has a crucial role in providing evidence‐based information and promoting positive sexual education to children, adolescents and parents. Improving knowledge can help counter misconceptions and reduce harms to girls and women.

Keywords: child, hymen, sex education, virginity

‘Virginity’ has no medical or scientific definition. It is a social, cultural and religious construct, which refers to the absence of former engagement in sexual intercourse. 1 However, it is not uncommon for the paediatrician to face virginity‐related concerns in various clinical situations: after an alleged sexual assault, during evaluations of post‐accidental traumas, in adolescents' well‐care visits, and following requests for virginity testing, certificates of virginity or hymenoplasty. This narrative review provides an overview of the notion of virginity through different perspectives such as culture, anatomy, forensic medicine, ethics and sex education. Our aim is to provide paediatricians with evidence‐based knowledge to improve their attitudes and practice when caring for young patients around the notion of virginity. Scientific information can help to reduce misconceptions and offer to children and adolescents the opportunity to grow and develop sexually in a healthy and respectful society.

Social Construction of Virginity

Virginity is a concept shared almost universally. The three monotheistic religions, as well as traditional cultures in different countries, value virginity before marriage. 2 Although not exclusively, the term ‘virginity’ is usually attributed to females. Controlling women's sexuality provides regulation of lineage since virginity before marriage helps prevent unfavourable alliances in patriarchal societies and provides reassurance about the paternity of children. Virginity is often considered as a virtue associated with purity, honour and morality. In some communities, it has an economic value as well, since a virgin bride brings money in dowry. 3

The recognition of women and children's human rights, the evolution of laws and the promotion of sex education have led to a change in attitudes and behaviours in pre‐marital sex in many parts of the world. However, even where pre‐marital virginity has lost some of its previous attributed value, the so‐called ‘loss of virginity’ remains a significant milestone in the adolescent and young adult's life. The issue of the first sexual intercourse is a central concern for teenagers of any gender and is associated with questioning, anxiety and expectations. In some circumstances, adolescents might feel ashamed to be considered still a ‘virgin’ and would like to get rid of this ‘embarrassing status’ as soon as possible. The myth that a male can feel with his penis if his female partner is virgin is widespread, although the feeling of ‘tightness’ is mostly due to anxiety and unvoluntary contraction of pelvic muscles rather than the absence of previous vaginal penetration. 4 Moreover, the misconception linking virginity to alterations of the female genital organs overlooks the fact that sexual encounters are not limited to the vagina, and not restricted to heterosexual practices.

Embryology and Anatomy of the Hymen

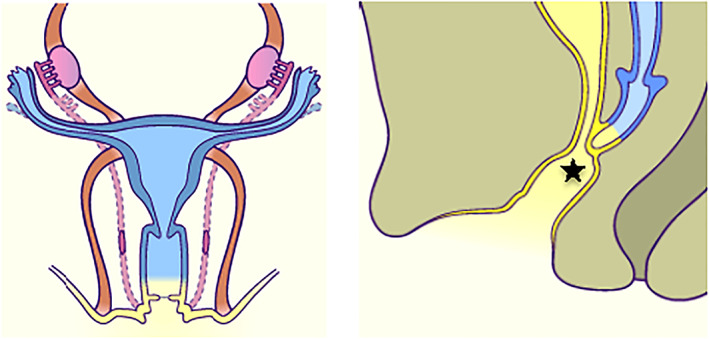

Virginity is commonly thought to be associated with the integrity of the hymen, which would rupture and bleed at first vaginal intercourse. 5 The hymen is a membranous tissue surrounding the vaginal introitus. Embryologically, the hymen is thought to derive from an invagination of the urogenital sinus. 6 , 7 The pelvic part of the urogenital sinus gives rise to the distal third of the vagina, which will join the utero‐vaginal canal arising from the fusion of the lower portion of the paramesonephric ducts around 12 weeks of gestation (Fig. 1). 7

Fig. 1.

Embryologic development of female genital organs. Left: Frontal view of female sex organs of a 4‐month fetus. The uterus and the upper part of the vagina (blue) come from the fusion of the paramesonephric ducts. The lower part of the vagina (yellow) comes from the urogenital sinus. Right: Sagittal view of female sex organs of a 5‐month fetus. The lumen of the vaginal canal is separated from the vaginal vestibule by the hymen (star), which will open around birth. (Reproduced from http://embryology.ch/anglais/ugenital/genitinterne05.html7, with permission.)

The hymen opens during the perinatal period. 5 If opening fails, a condition known as an imperforate hymen will ensue, which is the most common obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract, occurring in 1 of 1000 newborn girls. 6 Imperforate hymen may manifest at birth by a hydrocolpos. However, it often remains undiagnosed until adolescence and presents with primary amenorrhea and hematocolpos. The complete absence of the hymen is extremely rare and has been reported in cases of vaginal agenesis. 6

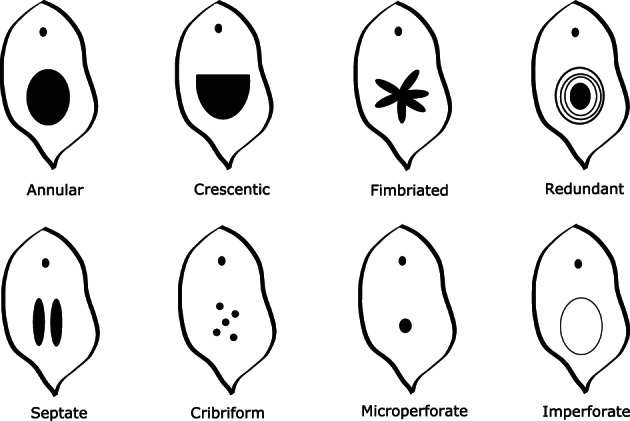

Hymenal anatomy has a wide range of shapes and appearances, such as annular (circumferential), crescentic (posterior rim), fimbriated, redundant (sleeve‐like), septate or cribriform (Fig. 2). 8 The hymen is a dynamic tissue, with morphological changes, also induced by hormonal variations. 8 Placental transfer of maternal hormones during pregnancy thickens and swells the hymen in the newborn. With the suppression of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐gonadal axis in pre‐pubertal girls, the hymen may become thin, dry and smooth‐edged. During puberty, the exposure to oestrogen contributes to the thickening of the hymen and provides more elasticity, enabling it to stretch during penetration without leaving any trace of injury. 5 The post‐pubertal hymen has been compared to a scrunchy or a rubber band because of its elastic properties for educational purposes. 9

Fig. 2.

Physiological variations of hymenal anatomy (upper line) and variations requiring investigations and treatment (lower line). A septate, cribriform or microperforate hymen may lead to difficulty with tampon's insertion or vaginal penetrative sex.

Examination of the Hymen

The hymen receives little consideration in medical schools and most paediatricians do not feel comfortable to examine it. 10 A cross‐sectional study showed that only 64% of 139 paediatric chief residents identified correctly the hymen on photographs of pre‐pubertal female genitalia. 11 Nevertheless, professional societies advocate that genital examination should be a routine part of a comprehensive physical examination in prepubertal girls, where it could provide not only useful clinical information but also the opportunity for health education to patients and family. 12 , 13 Evidence supports that children comfortable with the correct terminology of their genitalia are less vulnerable to sexual abuse and more likely to disclose any potential event. 14

Inspection does not require any special instrument and primary care setting is ideal. The patient is placed supine in a frog‐leg position on the examining table or, depending on her age and apprehension, seated on her caregiver, with legs bent in the same position. Inspection of the hymen, vaginal introitus, urethra and clitoris requires a separation and a slight diagonal traction of the external labia (Fig. 3). The hypoestrogenised hymen of the pre‐pubertal girl is atrophied, thus very thin and highly sensitive, so physicians should be careful not to touch it and cause pain inadvertently. 12 The prone knee‐chest position can confirm potential findings noted in the supine position, since gravity may unroll the hymenal folds, which may not have been visible in the frog‐leg position. Moreover, it improves visualisation of the inner vagina, sometimes up to the cervix.

Fig. 3.

Labelled diagram of the external female genitalia. Courtesy of Michal Yaron.

Genital Examination in Medicolegal Circumstances

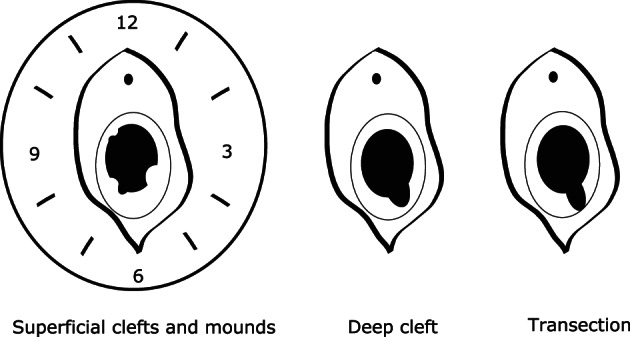

In cases suspected for sexual abuse, referral to a trained professional is necessary. 15 Nevertheless, evidence‐based data show that the large majority of children and adolescents who were victims of confirmed sexual abuse, with and without genital penetration, have normal or non‐specific findings on genital examination. 16 , 17 , 18 In a prospective study of 1500 girls aged from birth to 17 years old with a history of sexual abuse, 93% had an unremarkable genital examination, while 7% had one or more diagnostic findings. 17 Diagnostic findings for abuse were detected 10 times more (21.4 vs. 2.2%, respectively) when examination took place within 72 h from the assault, when the victim was older, or when the assault included genital penetration by a penis, finger or object. 17 Some morphological features of the hymen are non‐specific, such as clefts or notches, bumps or mounds, and irregularities extending to less than half the width of the hymenal rim (Fig. 4). 15 , 19 Findings highly suggestive of an acute sexual abuse include laceration of the hymen, posterior fourchette or vestibule, bruising, petechiae or abrasions of the hymen and vaginal or perianal laceration. 15 The hymen has a remarkable healing capacity, with most hymenal injuries healing completely in a few days without any scarring except in complete transection. 18 , 20 According to child abuse group of experts, transection is the only non‐acute evidence of a past and healed injury (Fig. 4). 15

Fig. 4.

Morphological features of the hymen. Left: Mounds and superficial clefts extending to <50% of the hymenal width are non‐specific. A clock‐face representation is suggested for consistent description of hymen's morphological features. Middle: A deep cleft extends to >50% of the hymenal width. Right: A transection is a complete defect traversing through the entire width of the hymen, to the fossa navicularis.

Hymenal trauma can result from accidental penetrating injury. 18 , 20 Despite common myths, there is no evidence that sport practice such as horse riding or tampons use can cause hymenal injuries. 21 , 22

The documentation of genital examination and hymen anatomy should be precise, using standardised medical terminology and a clock‐face analogy. Improper terms such as ‘intact’ or ‘broken’ hymen should be discarded as they are not descriptive, but interpretative. 5 Moreover, the interpretation of genital examination should be cautious: an examination described as ‘ normal’ or ‘nonspecific’ must not be interpreted as ‘nothing happened’. 23 Sometimes the patient or her caregivers may feel disappointed that the examination did not reveal any lesions. Levelling expectations before examination, by giving appropriate information on possible results, is paramount. The most important evidence of sexual abuse and the pivotal element for conviction in court remains the history provided by the victim.

Virginity Testing, Certificate of Virginity and Hymenoplasty

Despite scientific evidence showing that the hymen is not a reliable marker for previous sexual activity, misconceptions persist and lead to unjustified procedures, such as virginity testing, certificate of virginity and hymenoplasty.

Virginity testing refers to the practice of genital examination for the sole purpose of determining if a woman has had sexual intercourse or not. 1 It consists usually in inspection of the hymen or two‐finger vaginal insertion to assess the size of introitus and the laxity of the vaginal wall. 1 Although more commonly performed before marriage to assess the bride's suitability, virginity testing has also been reported as a routine examination in school setting, a repression against women protesters or as a requirement for work application. 3 , 24 Virginity testing has been described world‐wide, 2 , 25 including in high‐income countries. 1 , 4 , 26 It relies on the misconception that penile penetration leads to predictable changes of the female genital organs and overlooks the fact that sexual encounters are not limited to the vagina. Sexual practices involving the anus or the oral cavity are commonly reported by women willing to ‘spare’ their hymens. 25

The result of such testing can have devastating consequences on women who ‘fail’ them, such as shaming, social exclusion, reduction of dowry, violence and sometimes murder. 2 , 3 According to the World Health Organization, virginity tests are a form of sexual violence. 27 They are harmful not only to individuals but also to societies as they promote discrimination and gender inequality, and lead to violence against women. 24

Physicians may face a request to provide a certificate of virginity. In such uncomfortable situations and in fear for the safety of their patient, some may feel inclined to deliver a certificate of virginity of convenience, regardless of the findings on examination or even without proceeding to an examination. Although the intention is noble, this practice does not meet bioethical and deontological requirements since the physician solicited to provide such certification is asked to attest something that cannot be certified. 25 In 2020, the French government approved a law against virginity certification by health professionals, who can now incur a prison sentence or a fine. 28 Such approval of law raised a heated debate as some physicians argued that specifically banning certificates of virginity would cause more harm to vulnerable women, who may be at risk for their lives. 29 The national French medical order published an informative document for health professionals, stating that virginity cannot be scientifically and medically certified, reprimanding the delivery of such certification and suggesting to replace them with education, guidance, social support and, when indicated, protection to patients and families. 30

Hymenoplasty is a surgical act modifying the shape of the hymen, aiming to reduce its opening after previous vaginal intercourse. 25 The procedure's main goal is to obtain genital bleeding on the wedding night, in order to convince the groom and family members that the bride had never had a sexual experience prior to marriage. 4 , 25 Hymenoplasty relies on the false belief that all women bleed after the first vaginal intercourse, when in fact only half do so. 31 The efficacy of this intervention is doubtful: in the Netherlands, a small‐scale study showed that 17 of 19 women who underwent hymenoplasty reported no bleeding at first marital intercourse. 31 Because hymenal shape varies greatly between women, hymenoplasty is ‘at best, the surgeon's creative vision of what she or he imagines a woman's hymen has previously presented’. 10 Hymenoplasty is a controversial procedure, which is not taught at medical schools and is not described in most gynaecological textbooks. There is no regulation and standardisation of this procedure because it is not part of standard medical care. 4 In fact, it is classified by several national professional associations as a form of female genital cosmetic surgery. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 In some countries, it is performed secretly and/or illegally, because of the associated shame. 25 Over the last decades, high‐income countries have reported growing numbers of requests for this lucrative procedure, mainly in private settings. 4 , 26

Alternative tricks to mimic blood loss on the wedding night have been described, such as the use of a finger‐prick to produce drops of blood to be spread on the sheet or the insertion of a dissolvable capsule containing a red dye into the vagina. 36 Such products are easily available on the internet and sometimes even suggested by physicians. 31 However, no safety data are available on these practices and the insertion of poor‐quality material into the vagina is not without risk for woman's health. It is worth mentioning that the World Health Organization classifies all procedures to the female genitalia for non‐medical purposes, including the insertion of material into the vagina, as female genital mutilation type IV. 37 Scheduling the wedding date to coincide with the menstruations or manipulating oral contraceptives to obtain vaginal bleeding has also been reported. 4

Importance of Education by the Paediatrician

False ideas about the hymen and virginity persist among societies mainly because of the lack of education. Well‐child visits at the medical office are excellent opportunities to discuss sexual health. 38 Addressing this topic, like any other health matter, can reassure children and adolescents, who learn that any type of question can receive evidence‐based information in a confidential, safe and professional environment. Involving the patient while examining the genitalia by offering to look into a mirror or by using drawings or 3D models can help them understand genital anatomy. 39

Paediatricians should support sexual education within families, by also providing the parents with evidence‐based information and encouraging an open dialogue about sexual matters, appropriate to the age and development of the child. 40 While parents are often embarrassed and reluctant to address this delicate topic for fear of encouraging their adolescents to become sexually active, evidence suggests that sexual education and communication between parents and children are associated with a delay in sexual debut. 41

Sexuality should be addressed from a broad perspective. Sexual activity is much more than vaginal intercourse and considering the hymen as a biological marker of ‘virginity’ is not only wrong from a scientific point‐of‐view but also very limiting. Sexuality is expressed in diverse forms of behaviours, encompassing non‐penetrative gestures and penetrative sexual intercourse that can also be applied to same‐sex couples. Embracing a more nuanced view on sexuality is also useful when advocating for prevention of sexually transmitted infections that are possible with oral and anal sex. 42

It is also important to recognise that some terms such as ‘sexual activity’ or ‘virginity’ are often understood or interpreted differently. 42 , 43 For instance, among 925 adolescents, genital touching was considered to be abstinent behaviour by 83.5%, oral intercourse by 70.6% and anal sex by 16.1%, respectively. 43 It is therefore pertinent to ask for more precision and details when discussing sexual knowledge, attitudes and practices. The words associated with ‘virginity’ deserve to be chosen carefully. Expressions such as ‘losing or giving her virginity’ and ‘taking her virginity’ contribute to the perpetuation of misconceptions about the hymen and the female body, and of stereotypes about gender roles.

Conclusion

The notion of ‘virginity’ is a social construct, which has no physical foundation. The hymen is an elastic and changing tissue, with intra‐ and inter‐individual variations. It is not a marker of purity or sexual experience and there is no scientifically reliable way to determine virginity on examination. Requests for virginity testing, certificate of virginity or hymenoplasty should be declined but dealt with carefully by providing information and support that promote the psychophysical, social and sexual health of patients. Providing sexual education to children, adolescents and parents is part of the role of a paediatrician, who can improve sexual health and counter misconceptions, which are harmful to young women and more broadly to societies.

Acknowledgement

Open Access Funding provided by Universite de Geneve.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1. Olson RM, García‐Moreno C. Virginity testing: A systematic review. Reprod. Health 2017; 14: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frank MW, Bauer HM, Arican N et al. Virginity examinations in Turkey: Role of forensic physicians in controlling female sexuality. JAMA 1999; 282: 485–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Behrens KG. Why physicians ought not to perform virginity tests. J. Med. Ethics 2015; 41: 691–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ayuandini S. How variability in hymenoplasty recommendations leads to contrasting rates of surgery in The Netherlands: An ethnographic qualitative analysis. Cult. Health Sex. 2017; 19: 352–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mishori R, Ferdowsian H, Naimer K et al. The little tissue that couldn't – Dispelling myths about the Hymen's role in determining sexual history and assault. Reprod. Health 2019; 16: 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heller DS. A review of lesions of the posterior fourchette, posterior vestibule (fossa navicularis), and hymen. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2015; 19: 262–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schöni‐Affolter F, Dubuis‐Grieder C, Strauch E. Adé‐Damilano M. Differentiation of the Canal System in the Genital Organ in Females [Updated]. 2005. Available from: http://embryology.ch/anglais/ugenital/genitinterne05.html [accessed 7 February 2021].

- 8. Berenson AB, Grady JJ. A longitudinal study of hymenal development from 3 to 9 years of age. J. Pediatr. 2002; 140: 600–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brochmann N, Dahl ES, Moffatt L, et al. The Wonder Down Under: A User's Guide to the Vagina. UK: Hodder & Stoughton; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jarral F. A hymen epiphany. J. Clin. Ethics 2015; 26: 158–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dubow SR, Giardino AP, Christian CW et al. Do pediatric chief residents recognize details of prepubertal female genital anatomy: A national survey. Child Abuse Negl. 2005; 29: 195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jacobs AM, Alderman EM. Gynecologic examination of the prepubertal girl. Pediatr. Rev. 2014; 35: 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Braverman PK, Breech L; The Committee on Adolescence. Gynecologic examination for adolescents in the pediatric office setting. Pediatrics 2010; 126: 583–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khoori E, Gholamfarkhani S, Tatari M et al. Parents as teachers: Mothers' roles in sexual abuse prevention education in Gorgan, Iran. Child Abuse Negl. 2020; 109: 104695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adams JA, Farst KJ, Kellogg ND. Interpretation of medical findings in suspected child sexual abuse: An update for 2018. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2018; 31: 225–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heger A, Ticson L, Velasquez O et al. Children referred for possible sexual abuse: Medical findings in 2384 children. Child Abuse Negl. 2002; 26: 645–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gallion HR, Milam LJ, Littrell LL. Genital findings in cases of child sexual abuse: Genital vs vaginal penetration. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2016; 29: 604–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCann J, Miyamoto S, Boyle C et al. Healing of hymenal injuries in prepubertal and adolescent girls: A descriptive study. Pediatrics 2007; 119: e1094–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berenson AB, Chacko MR, Wiemann CM et al. Use of hymenal measurements in the diagnosis of previous penetration. Pediatrics 2002; 109: 228–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heppenstall‐Heger A, McConnell G, Ticson L et al. Healing patterns in anogenital injuries: A longitudinal study of injuries associated with sexual abuse, accidental injuries, or genital surgery in the preadolescent child. Pediatrics 2003; 112: 829–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goodyear‐Smith FA, Laidlaw TM. Can tampon use cause hymen changes in girls who have not had sexual intercourse? A review of the literature. Forensic Sci. Int. 1998; 94: 147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lejeune J, Martrille L, Guillet‐May F et al. Prospective forensic study on the characterization of genital examination in women with consented sexual activity. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 2021. (forthcoming). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kellogg ND, Menard SW, Santos A. Genital anatomy in pregnant adolescents: “Normal” does not mean “nothing happened.”. Pediatrics 2004; 113: e67–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Independent Forensic Expert Group . Statement on virginity testing. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2015; 33: 121–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ahmadi A. Recreating virginity in Iran: Hymenoplasty as a form of resistance. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2016; 30: 222–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moaddab A, McCullough LB, Chervenak FA et al. A survey of honor‐related practices among US obstetricians and gynecologists. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017; 139: 164–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organization . Eliminating Virginity Testing: An Interagency Statement. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/eliminating-virginity-testing-interagency-statement/en/ [accessed 6 February 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Compte rendu du conseil des ministres du 9 décembre 2020. Available from: https://www.gouvernement.fr/conseil-des-ministres/2020-12-09 [accessed 22 March 2021].

- 29. Certificats de virginité: Punir les médecins ne résoudra pas le problème du séparatisme. France: Les généralistes CSMF; 2020. Available from: https://lesgeneralistes-csmf.fr/2020/10/27/certificats-de-virginite-punir-les-medecins-ne-resoudra-pas-le-probleme-du-separatisme/ [accessed 25 March 2021].

- 30.Ordre National des Médecins. Certificats de virginité: Documentation d'information à destination du médecin. France: Ordre national des Médecins; 2021. Available from: https://www.conseil-national.medecin.fr/sites/default/files/external-package/rapport/u9xikj/cnom_certificats_de_virginite.pdf [accessed 25 March 2021].

- 31. van Moorst BR, van Lunsen RHW, van Dijken DKE et al. Backgrounds of women applying for hymen reconstruction, the effects of counselling on myths and misunderstandings about virginity, and the results of hymen reconstruction. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2012; 17: 93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . Ethical Opinion Paper: Ethical Considerations in Relation to Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery (FGCS). UK: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2013. Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/news/joint-rcogbritspag-release-issues-surrounding-women-and-girls-undergoing-female-genital-cosmetic-surgery-explored/ [accessed 6 February 2021].

- 33. Elective female genital cosmetic surgery: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 795. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020; 135: e36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shaw D, Lefebvre G, Bouchard C et al. Female genital cosmetic surgery. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2013; 35: 1108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners . Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery. Australia: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2015. Available from: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/female-genital-cosmetic-surgery [accessed 21 December 2021].

- 36. Ayuandini S. Finger pricks and blood vials: How doctors medicalize ‘cultural’ solutions to demedicalize the ‘broken’ hymen in The Netherlands. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017; 177: 61–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. World Health Organization . Female Genital Mutilation. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation [accessed 21 December 2021].

- 38. Breuner CC, Mattson G; Committee on Adolescence; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Sexuality education for children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2016; 138: e20161348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abdulcadir J, Dewaele R, Firmenich N et al. In vivo imaging–based 3‐dimensional pelvic prototype models to improve education regarding sexual anatomy and physiology. J. Sex. Med. 2020; 17: 1590–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yaron M, Soroken C, Narring F et al. Adolescence and sexuality: A risky business how best to inform parents? Rev. Med. Suisse 2018; 14: 843–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Karofsky PS, Zeng L, Kosorok MR. Relationship between adolescent‐parental communication and initiation of first intercourse by adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2001; 28: 41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Byers ES, Henderson J, Hobson KM. University students' definitions of sexual abstinence and having sex. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2009; 38: 665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bersamin MM, Fisher DA, Walker S et al. Defining virginity and abstinence: Adolescents' interpretations of sexual behaviors. J. Adolesc. Health 2007; 41: 182–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]