Abstract

α-syntrophin (α-syn) and α-dystrobrevin (α-dbn), two components of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex, are essential for the maturation and maintenance of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) and mice deficient in either α-syn or α-dbn exhibit similar synaptic defects. However, the functional link between these two proteins and whether they exert distinct or redundant functions in the postsynaptic organization of the NMJ remain largely unknown. We generated and analyzed the synaptic phenotype of double heterozygote (α-dbn+/−, α-syn+/−), and double homozygote knockout (α-dbn−/−; α-syn−/−) mice and examined the ability of individual molecules to restore their defects in the synaptic phenotype. We showed that in double heterozygote mice, NMJs have normal synaptic phenotypes and no signs of muscular dystrophy. However, in double knockout mice (α-dbn−/−; α-syn−/−), the synaptic phenotype (the density, the turnover and the distribution of AChRs within synaptic branches) is more severely impaired than in single α-dbn−/− or α-syn−/− mutants. Furthermore, double mutant and single α-dbn−/− mutant mice showed more severe exercise-induced fatigue and more significant reductions in grip strength than single α-syn−/− mutant and wild-type. Finally, we showed that the overexpression of the transgene α-syn-GFP in muscles of double mutant restores primarily the abnormal extensions of membrane containing AChRs that extend beyond synaptic gutters and lack synaptic folds, whereas the overexpression of α-dbn essentially restores the abnormal dispersion of patchy AChR aggregates in the crests of synaptic folds. Altogether, these data suggest that α-syn and α-dbn act in parallel pathways and exert distinct functions on the postsynaptic structural organization of NMJs.

Introduction

The dystrophin–glycoprotein complex (DGC), which links the extracellular matrix to the intracellular cytoskeleton (1,2), plays a crucial role in the maintenance of the structural integrity of the muscle fiber (3). Mutations in genes that encode components of the DGC cause numerous muscular dystrophies (4,5). The DGC has also been implicated in the maturation and maintenance of the neuromuscular synapse (3,6–8), but not all components of the DGC are required for the stabilization and anchoring of acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) in the postsynaptic membrane (2,3,9). For instance, mice deficient in utrophin display only subtle defects (10,11), mice deficient in dystrophin (mdx mice) display some defects in synaptic geometry (12) and mice deficient in α- orjb γ-sarcoglycan have an approximately normal appearance of NMJs (13). On the other hand, mice deficient in cytoplasmic DGC protein α-dbn or α-syn have NMJs that display profound postsynaptic alterations (7,14).

In skeletal muscles, two major isoforms of α-dbn are produced by alternative splicing, α-dbn1 and α-dbn2, which are differentially localized in skeletal muscle (15,16). The tyrosine-phosphorylated α-dbn1 isoform is predominantly enriched at the crests of NMJ junctional folds where it binds α-syn and dystrophin/utrophin, while the non-phosphorylated isoform α-dbn2 is the predominant isoform in extra-junctional regions, and is also present at NMJs (17,18). Likewise, α-syn (the predominant isoform of all syntrophins in the muscle fiber) is distributed throughout the sarcolemma and is enriched at both the crests and troughs of junctional folds (19). Muscles deficient in α-dbn or α-syn are histologically different. While muscles deficient in α-syn exhibit no symptoms of muscular dystrophy, ~ 50% of muscles in α-dbn deficient adult mice have a dystrophic phenotype (20,21), and yet their NMJs display similar structural abnormalities (7,8,14). It is also worth noting that in the absence of either α-dbn or α-syn, the distribution and localization of DGC components at NMJs remain largely intact (7,14), suggesting that the abnormal synaptic phenotype is largely a result of impaired α-syn and α-dbn-dependent signaling mechanisms. Indeed, previous reports indicated that α-syn and α-dbn can bind diverse signaling and structural molecules to the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) (22–25). Despite data showing that NMJs of mice deficient in α-dbn or α-syn display alike structural abnormalities, the functional link between α-dbn and α-syn and whether they control the same structural organization of the NMJ remain unknown. Particularly, the effect of signaling dysfunction caused by the loss of both α-syn and α-dbn on the structural organization of NMJs and the pathogenesis of muscular dystrophy.

In this work, we address these issues through generation and analysis of the synaptic phenotype of double heterozygote (α-syn−/+, α-dbn−/+) and double homozygote knockout (α-syn−/−, α-dbn−/−) mice, and the ability of individual molecules to restore the synaptic phenotype in double mutants. We show that double heterozygote mice display no evidence of impaired NMJs and/or muscular dystrophy, while the resulting NMJ phenotypes from double homozygote mutants lacking a combination of α-dbn and α-syn exhibit severe alterations compared to either single null α-dbn or α-syn mutants. However, muscle regeneration (a hallmark of muscular dystrophies) and muscular strength appear not to be significantly different between double (α-syn−/−, α-dbn−/−) and single αdbn−/− mutants. Finally, we show that α-dbn was able to significantly restore AChR clusters at the crests of the fold, while α-syn was able to rescue the abnormal organization of extended synaptic folds (troughs). Altogether, these results provide new insights into distinct functions of α-dbn and α-syn, two components of the DGC, on the structural organization of the postsynaptic membrane of NMJs.

Results

Generation of heterozygote and double homozygote null α-dbn and α-syn mice

Because NMJs of α-syn or α-dbn null mice display similarities in structural defects (7,14), we investigated whether these two components of the DGC control the same downstream signaling pathway that leads to similar postsynaptic abnormalities. We established lines of double heterozygote mice lacking half of α-syn and α-dbn and double homozygote null α-syn and α-dbn mice. α-dbn male knockout mice (F0♂ α-dbn−/−, (7)) were crossed with the α-syn female knockout mice (F0♀ α-syn−/−, (14)) and the first generation of the double heterozygotes was confirmed by PCR (F1: α-dbn+/−; α-syn+/−). The generation of α-dbn and α-syn double knockout mice was performed by crossing mice from the F1 generation and performing PCR on their offspring to screen for the absence of both α-dbn and α-syn (F2: α-dbn−/−; α-syn−/−). Double heterozygotes (α-dbn+/−; α-syn+/−) and double knockout homozygotes (α-dbn−/−; α-syn−/−) for α-syn and α-dbn were confirmed by western blots using α-syn and α-dbn specific antibodies (Figs 1B and2A). As expected, in double heterozygote mice the amount of α-dbn and α-syn was reduced by about half compared to wild-type (Fig. 1A and B), while in homozygous double knockout mice no α-syn and α-dbn proteins were detected (Fig. 2A). The wild-type (α-dbn+/+; α-syn+/+), α-dbn−/− and α-syn−/− single mutant mice were used as littermate controls.

Figure 1.

Characterization and analysis of the NMJs of double heterozygote (α-dbn+/−, α-syn+/−) mice. α-dbn male knockout mice (α-dbn−/−) were crossed with the α-syn female knockout mice (α-syn−/−) to generate double heterozygote (α-dbn+/−, α-syn+/−) mice. (A-B) RT-PCR and Western blots of skeletal muscle homogenates (sternomastoid or gastrocnemius muscles) from young male or female bred animals (2–4 months) confirming the reduction by about half of transcript and protein expression levels of α-dbn and α-syn. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) Sternomastoid muscles (2–4 month-old) of wild-type and heterozygote mice were labeled with α-BTX-AlexaFluor 488 and NMJs were imaged with the confocal microscope (two representative images were shown, wildtype-type (left panel) and heterozygote (right panel)). (D) Example of muscle sections from wild-type and heterozygote mice stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Note that there were no signs of muscular dystrophy (central localization of nuclei) in heterozygote muscles. (E) Examples of NMJs on sternomastoid muscles labeled with a saturating dose of α-BTX-AlexaFluor 488 and imaged in vivo; the pseudo-color images provide a linear representation of the density of AChRs (white-yellow, high density; red-black, low density). (F) Graphs summarizing the quantification of fluorescent data from wild-type and heterozygote mice NMJs as shown in panel E. (G) Sternomastoid muscles of wild-type and age-matched heterozygote mice were bathed with a low dose of fluorescent BTX and superficial NMJs were imaged and re-imaged 3 days later. The intensity of the fluorescence was measured at each time and the total fluorescence intensity of AChR was normalized to 100% at the initial imaging. The graph shows the half-life of AChRs. Note that the half-life of AChRs in wild-type NMJs (t1/2 of ∼10.7 ± 1.95 days, N = 20 NMJs from 3 animals) was not significantly different from the half-life of AChRs in heterozygote mice (t1/2 ∼ 10.3 ± 2 days, N = 15 NMJs from 3 mice). WT: wild-type; D. Hetero: double heterozygotes. Data are means ± SD. Scale bars: C, E: 10 μm; D: 100 μm.

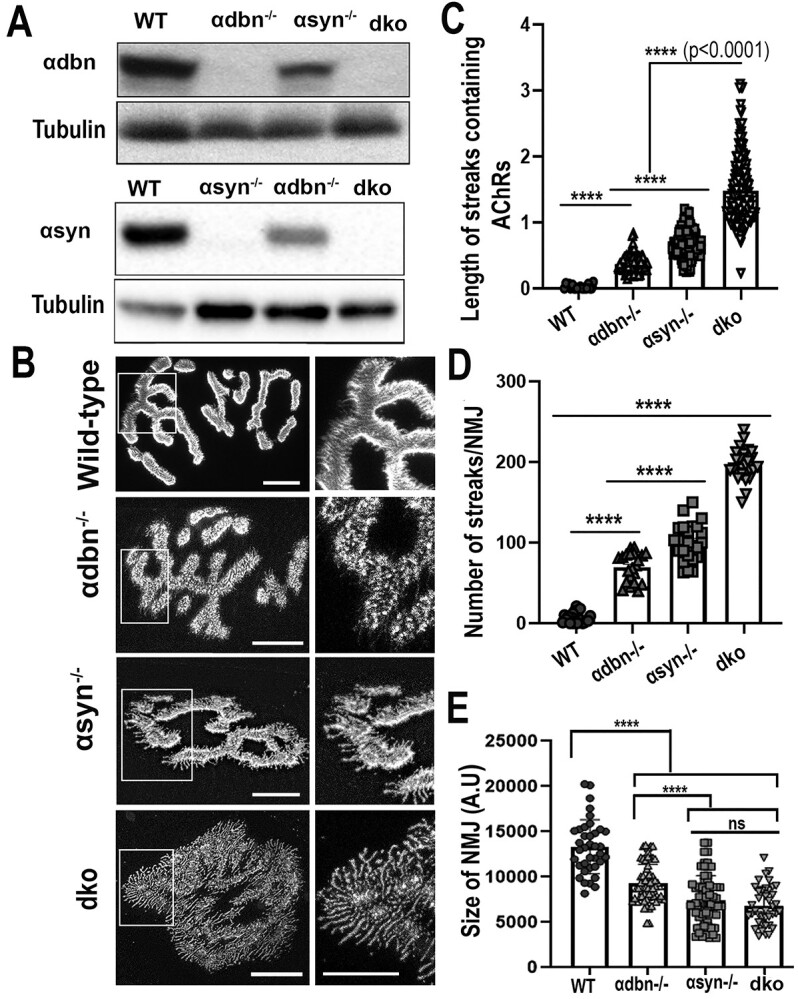

Figure 2.

Characterization and analysis of the NMJs of double homozygote knock-out (α-dbn−/−, α-syn−/−) mice. (A) Western blots of skeletal muscle homogenates from dko confirming the absence of α-dbn and α-syn proteins. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (B) Sternomastoid muscles of young adult mice (2–3 month-old) from wild-type, α-dbn−/−, α-syn−/−, and dko (α-dbn−/−; α-syn−/−) were fixed and stained with α-BTX-AlexaFluor 488. Examples of representative images of NMJs stained with a fluorescent BTX from the above mice are shown. (C) Quantification of the length of membrane containing AChRs. Note that in NMJs from dko, the lines of AChRs extending beyond the undefined gutters were significantly longer than either α-syn or α-dbn mutant synapses. (D) Histogram showing the frequency of the abnormal AChR extensions beyond synaptic gutters. (E) Quantification of areas occupied by AChRs (synaptic size). Note that the synaptic size of single and double mutants was significantly reduced compared to wild-type, while there was no significant difference between α-syn−/− and dko genotypes. Scale bars: 10 μm.

To assess whether the reduction of α-dbn and α-syn in double heterozygote (α-dbn+/−; α-syn+/−) mice has any impact on the structural integrity of NMJs and muscle fibers, we examined the morphology of NMJs, the density/number of AChRs, the metabolic stability of AChRs and signs of muscular dystrophy. We found no obvious structural abnormalities in either the NMJ or skeletal muscle cells. High-resolution confocal images of double heterozygote NMJs showed that AChRs are distributed in a smooth and sharply delineated stripe pattern inside the synaptic gutters, similar to wild-type NMJs (Fig. 1C). Quantification of fluorescent AChRs revealed that the density/number of AChRs at NMJs of heterozygote mice (95 ± 19%; n = 28 NMJs, from 5 mice) was not significantly different from wild-type synapses (100 ± 12%; n = 64 NMJs, 8 mice, P = 0.13) (Fig. 1E and F). Also, there was no significant difference in the turnover rate of AChRs at NMJs between wild-type (t1/2 of ∼10.7 ± 1.95 d; 20 NMJs from 3 mice) and heterozygote mice (t1/2 ∼ 10.3 ± 2 d, 15 NMJs from 3 mice, P = 0.63) after 72 h (Fig. 1G). Finally, hematoxylin–eosin staining of muscle sections showed no signs of muscle dystrophy (presence of small groups of degenerating myofibers or central nuclei) in double heterozygote mice (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that a single copy of α-dbn and α-syn in the double heterozygous genotype produces sufficient amounts of proteins to maintain the wild-type phenotype of the NMJ.

Distribution of AChRs at the neuromuscular junctions of double knockout mutant (α-syn −/−, α-dbn −/−) mice

We tested whether the absence of both α-syn and α-dbn from the muscle exacerbates the NMJ abnormalities compared to either single knockout. The sternomastoid muscles from single α-syn−/−, α-dbn−/−, double (α-dbn−/−; α-syn−/−) knockout (dko), and wild-type mice were bathed with fluorescent α-BTX-AlexaFluor 488/594 and NMJs were imaged with a confocal microscope. Because α-dbn and dko knockout mice (20) (Fig. 5D and E) exhibit moderate muscular dystrophy, we analyzed only synapses that did not show a pattern of muscle degeneration/regeneration (fragmented appearance). Compared to single mutant and wild-type, double mutant NMJs showed profound alterations in the distribution of AChRs (Fig. 2B). Particularly, we found that most dko synapses displayed long extensions of streaks/speckles containing AChRs that radiated out from the entire undefined contour of NMJs, and numerous small and independent AChR ‘hot spot’ aggregates (Fig. 2B). Quantification of streaks’ lengths revealed that the average length of AChR extensions at NMJs of double knockout (1.5 μm ± 0.47, n = 217 speckles/streaks measured from 20 NMJs, 8 mice) was significantly longer than that observed at NMJs of single syn−/− (0.67 μm ± 0.4; n = 250, 20 NMJs, 5 mice; P < 0.0001 value), at NMJs of α-dbn−/− (0.4 μm ± 0.5; n = 140, 15 NMJs, 5 mice; P < 0.0001), or at NMJs of wild-type (0.024 ± 0.8, n = 217, 10 NMJs, 4 mice, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2C). Additionally, the frequency of streaks per synapse in dko mice (196.8 ± 19.59 SD, n = 26 NMJs, 5 mice) was substantially higher than α-syn−/− (100.6 ± 22.9 SD, n = 25 NMJs, 5 mice, P < 0.0001), α-dbn−/− (69.38 ± 18.07 SD, n = 21 NMJs, 4 mice, P < 0.0001), and wild-type mice (6.47 ± 6.48 SD, n = 25 NMJ, 5 mice, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2D). In sharp contrast to wild-type NMJs in which the edges of synaptic gutters were intensely bright (parallel to the axis of the microscope images), most dko NMJs exhibited unrecognizable and undefined synaptic gutters (Fig. 2B). NMJs of either α-syn−/−, or α-dbn−/− exhibit variable abnormalities in synaptic gutters as described previously (6,7). The areas occupied by AChRs at NMJs (synaptic size) of dko (6802 ± 2150 SD, n = 40 NMJs, 5 mice) and α-syn−/− (7481 ± 2675 SD, n = 67 NMJs, 6 mice) were also significantly reduced compared to single mutant α-dbn−/− (9283 ± 2253 SD, n = 60 NMJs, 5 mice), or wild-type synapses (13 337 ± 2979 SD, n = 37 NMJs, 5 mice; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2E). These results indicate that the simultaneous loss of α-dbn and α-syn exacerbates synaptic abnormalities at NMJs. It is also worth noting that the average length of streaks containing AChRs and the frequency of streaks per synapse in α-syn mutant mice were significantly higher than those observed in mice deficient in α-dbn (Fig. 2D and E), suggesting that α-dbn and α-syn might have a different function on the structural organization of the NMJ despite the similarities between their knockout synaptic phenotypes.

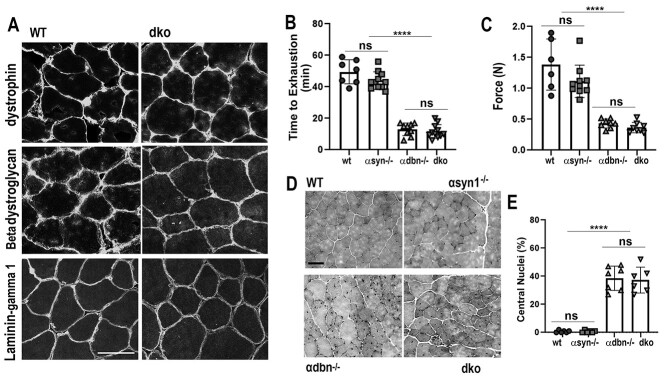

Figure 5.

Synaptic strength and force generation are reduced in dko and single α-dbn−/−, while the distribution of DGC and basal lamina components remain unaffected. (A) Sections of sternomastoid muscles from wild-type and dko were stained with antibodies against DGC complex and laminin gamma 1 (γ1) and imaged with a confocal microscope. No changes in the localization of either β-dystroglycan, dystrophin, or laminin γ1 around the membrane of the muscle cell of dko compared to wild-type. (B) Wild-type, single and dko mice were forced to run on a treadmill and the time to exhaustion of each animal was recorded as shown in Histogram B. Note that the time to exhaustion of dko and α-dbn−/− mice was significantly shorter than α-syn−/− and wild-type mice. (C) Histogram showing the forelimb grip strength. Note that there was no significant difference in the grip strength between dko and α-dbn−/− mutant mice, but it was significantly reduced compared to α-syn−/− and wild-type mice. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin on sections of sternomastoid muscles from adult dko, single α-dbn−/−, α-syn−/− and wild-type mice. (E) Histogram showing the quantification of muscles containing central nuclei (signs of muscle regeneration). Data are means ± SD. Scale bars: 10 μm (A); and 100 μm (D).

Next, we assessed whether the loss of junctional folds is worsened at NMJs of dko compared to single α-dbn or α-syn mutants. The sternomastoid muscles of dko, α-dbn−/−, α-syn−/− and wild-type NMJs were doubly labeled with fluorophore-conjugated lectin VVΑ-B4 (a marker for junctional folds that labels the troughs of the folds more strongly than the AChR-rich crests of the NMJ (14,26)) and fluorescently labeled BTX to label AChRs. Figure 3 shows that high-resolution confocal images of in-face views of dko NMJs exhibited either weak or no labeling of fluorescent VVA-B4 in major areas of membrane containing AChRs, in sharp contrast to wild-type synapses in which the entire AChR-rich area was labeled by VVA-B4 (Fig. 3A). The ratio of the area of VVA-B4 staining to that of AChR staining was significantly reduced in synapses of dko compared to single mutants and wild-type synapses (Fig. 3B). It is worth noting that the ratio of VVA-B4 to AChR in synapses of the α-syn−/− mutant was also significantly reduced compared to α-dbn−/− synapses (Fig. 3B).

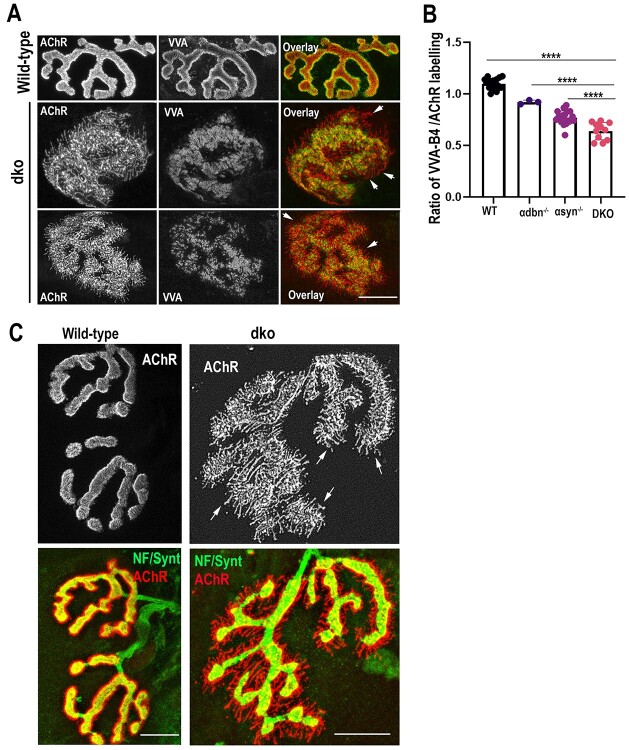

Figure 3.

Innervation, distribution of AChRs and synaptic folds in NMJs of dko (α-dbn−/−; α-syn−/−). (A) Fixed sternomastoid muscles from wild-type and dko were doubly labeled with α-BTX-AlexaFluor 594 (to label AChRs) and VVA-B4-AlexaFluor 488 (marker of junctional folds). Note that in wild-type NMJs, branches display a perfect overlay between the labeling of AChR and VVA-B4 where AChRs are distributed smoothly at the crest and VVA-B4 at troughs of junctional folds. In contrast, in NMJs of dko, virtually all of the areas containing finger-like extensions of AChRs were largely devoid of VVA-B4 staining (see arrows), suggesting the absence of junctional folds. (B) Histograms show the quantification of the ratio of areas occupied by AChRs and VVA-B4. The area of α-BTX fluorescence and VVA-B4 fluorescence at each synapse was determined as described in methods, and then the ratio of the area of each synapse was calculated (****P < 0.0001). Note that in NMJs of dko significant regions of AChRs are devoid of VVA-B4 compared to single mutants and wild-type. (C) Examples of NMJs from dko and age-matched wild-type stained with α-BTX-AlexaFluor 594 to label AChRs and with antibodies against neurofilament and synaptophysin (green) to label axons. Note that in wild-type, nerve terminals (green) are in direct apposition to AChR-rich in the postsynaptic membrane, whereas in dko all the abnormal extensions of membrane containing AChRs are no longer covered by nerve terminal branches, see arrows). Data are means ± SD. Scale bars 10 μm.

We also examined whether the distribution of overlying motor nerve terminals was altered in dko NMJs. Fixed sternomastoid muscles from wild-type and dko were immunostained with antibodies against neurofilament and synaptophysin to label motor nerve terminals and with α-BTX–Alexa Fluor 594 to label AChRs. High-resolution images showed that in wild-type synapses presynaptic terminal branches covered the entire postsynaptic receptor areas, while in dko NMJs the extending streaks of AChR-rich postsynaptic sites were not covered by the nerve terminals (Fig. 3C). However, no obvious abnormalities were visible in the presynaptic nerve terminals at dko synapses. These data suggest that the absence of α-dbn and α-syn have direct consequences on the abnormal alignment of the nerve terminal and areas containing AChRs.

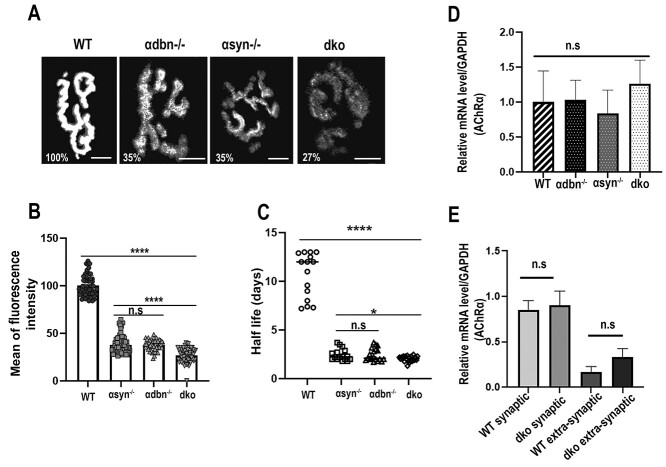

The density and turnover rate of acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are significantly altered in dko

Previous studies showed that the postsynaptic density of AChRs and the turnover rate of AChRs at NMJs deficient in α-syn−/− or α-dbn−/− were significantly altered compared to wild-type synapses (8,27). Here we asked whether the absence of both α-dbn and α-syn from muscle cells exacerbates alterations in postsynaptic density and the turnover rate of AChRs at NMJs. To assess the density of AChRs, the sternomastoid muscles of dko, single mutant (α-syn−/− or α-dbn−/−) and wild-type were labeled with a saturating dose of fluorescent BTX, and the fluorescence intensity of superficial synapses was measured. We found that the density of AChRs was significantly reduced in dko compared to single mutants and wild-type mice. Quantification of the total fluorescence intensity of labeled AChRs at NMJs showed that the density of AChRs in dko (α-dbn−/−; α-syn−/−) was 27.05 ± 6%, (n = 66 NMJs, 4 mice), in age-matched α-dbn−/− mice was 37 ± 5%, (n = 50 NMJs, 4 mice, P < 0.0001), and in α-syn−/− mice was 38.02 ± 9%, (n = 67 NMJs, 5 mice, P < 0.0001), compared to wild-type NMJs (100.2 ± 14%, n = 66 NMJs, 4 mice) (Fig. 4A and B). This result indicates that the density of AChRs was further reduced in dko NMJs when compared to single mutants.

Figure 4.

Density and turnover rate of AChRs were further altered in NMJs of dko compared to single mutants. (A) The sternomastoid muscle of wild-type, α-dbn−/−, α-syn−/− and dko were bathed with α-BTX-AlexaFluor 488/594 until all AChRs were saturated and superficial NMJs were imaged. The density of AChRs was assessed as described in Methods. Shown are examples of NMJs from wild-type and mutants. The pseudo-color images provide a linear representation of the density of AChRs (white-yellow, high density; red-black, low density). (B) Graphs summarizing the quantification of fluorescent data from NMJs as shown in the panel. Note the density of AChRs was significantly reduced in dko compared to single mutants. (C) Sternomastoid muscles of wild-type, single and double mutant α-dbn and α-syn were bathed with a low dose of fluorescent BTX, and superficial NMJs were imaged and re-imaged 3 days later. The graph shows the turnover rate of AChRs. Note that the turnover rate of AChRs was significantly increased in dko compared to single mutant and wild-type. (D) Quantitative real-time PCR products of AChRα subunit from sternomastoid muscles of all genotypes. (E) Quantitative real-time PCR products of AChRα subunit from synaptic and extra-synaptic regions of dko and wild-type sternomastoid muscles. Note that there was no significant difference in AChRα subunit transcript levels between all genotypes (at least 3 mice were used per experiment. Data are means ± SEM. Scale bars: 10 μm.

To examine the turnover rate of AChRs, the sternomastoid muscles of dko, single mutants and wild-type mice were bathed with a low dose of a fluorescent BTX, and individual synapses were imaged. Three days later, the same synapses were imaged again and the fluorescently labeled AChRs were assessed. Quantification of fluorescently labeled AChRs showed that in dko mice, the fluorescence intensity of the labeled AChRs 3 days after initial imaging had decreased to 36 ± 2% SD (n = 21 NMJs, 5 mice; corresponding to a t1/2 = 2 days) while in α-syn−/− (single mutant) the fluorescence intensity had decreased to 44 ± 3% SD (n = 16 NMJs, 5 mice; corresponding to a t1/2 = 2.5 days), and in α-dbn−/−, had decreased to 43 ± 3.5% SD (n = 19 NMJs, 4 mice, corresponding to a t1/2 = 2.46 days; P < 0.0001 versus dko). In wild-type synapses, the fluorescence intensity of the labeled receptors had decreased to 82.6 ± 7% SD (n = 15 NMJs, n = 3 mice, corresponding to a t1/2 ~ 11 days) (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that the absence of both α-syn and α-dbn from the muscle cells caused a slight, but significant, increase in the turnover rate of AChRs when compared to single mutants.

Next, we examined whether reduction of AChR density at mutant synapses resulted in a down-regulation of AChR subunit genes expression in muscle cells. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was used to determine the expression levels of AChR-α subunit in sternomastoid muscles of all genotypes [wild-type, α-syn−/−, α-dbn−/− and double (α-syn−/−; α-dbn−/−) mutants]. Figure 4D showed that there was no significant difference between AChR-α subunit mRNA expression levels between all genotypes. We also found no significant difference in AChR-subunit transcript levels between synaptic and non-synaptic dko sternomastoid muscles and wild-type (Fig. 4E), indicating that the absence of both α-syn and α-dbn from muscle cells has no effect on receptor gene expression and strongly argue that they are involved in regulating AChRs accumulation in the postsynaptic membrane.

Dystrophin–glycoprotein complex localization, exercise-induced fatigue and limb grip strength in α-dbn and α-syn double mutant mice

The localization of most components of the DGC remains unaltered in single α-dbn and α-syn knockout mice (7,14). Because both α-dbn and α-syn are components of the DGC, we asked whether the simultaneous loss of these two proteins could affect the localization and the distribution of the other DGC and basal lamina components. Sections of the sternomastoid muscle of dko and wild-type mice were immunostained with a panel of antibodies against key DGC components such as dystrophin (a key cytoskeletal protein), transmembrane β-dystroglycan and its attached α-dystroglycan protein. Laminin-gamma 1 (γ1), a component of the basal lamina (28), was also examined. In dko muscle fibers, it appeared that the distribution of dystrophin throughout the sarcolemma of the muscle cells (extra-synaptic and synaptic membrane) remained unchanged, similar to wild-type (Fig. 5A). Likewise, there was no change in the localization of the single-pass transmembrane protein β-dystroglycan and its attached peripheral protein α-dystroglycan (not shown) around the membrane of the muscle cell of dko compared to wild-type (Fig. 5A). The laminin γ1 also remained unchanged throughout the basement membrane of the skeletal muscle (extra-synaptic and synaptic membrane) compared to wild-type (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that both α-syn and α-dbn are not essential for either the tethering/maintenance of the β-dystroglycan transmembrane protein or for the normal distribution and localization of other members of the DGC and the basal lamina, laminin γ1.

We also evaluated whether muscle function and muscular strength were further reduced in the double mutant compared to single deficient mice. First, we used a treadmill exhaustion test, which evaluates exercise capacity and endurance. Mice were forced to run to exhaustion on a conveyor belt with gradually increasing speed. We observed no significant differences in the time to exhaustion between wild-type (49 min ± 4% SD, n = 7 mice) and single α-syn−/− mutant mice (44 min ± 3% SD, n = 11 mice, P = 0.09). However, double mutant (α-syn−/−; α-dbn−/−) and single α-dbn−/− mutant mice had significantly shorter time to exhaustion (dko: 11.7 min ± 1.3% SD, n = 11 mice; α-dbn−/−: 13 min ± 1.8% SD, n = 9 mice, P < 0.0001 versus wild-type). This indicates that dko and α-dbn−/− mice became more sensitive to exercise-induced fatigue than other groups (Fig. 5B). However, no significant difference was observed between dko and α-dbn single mutant, indicating that the fatigue-like behavior in dko is likely due to the absence of α-dbn. In a second test, we used a forelimb grip strength assay to measure muscular strength. Each mouse was tested at least 3 times and recorded grip strength values were normalized to the body weight of each mouse. Figure 5C shows a significant deficit in grip strength in dko mice compared to α-syn−/− and wild-type mice (P < 0.0001). However, no significant difference was found between dko and the single α-dbn−/− mutant (values, P = 0.11).

Because single α-dbn−/− muscles display moderate muscular dystrophy, we examined whether loss of α-syn could worsen muscular dystrophy in dko mice. Sections of sternomastoid muscles from adult dko, single α-dbn−/−, α-syn−/− and wild-type mice were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. As expected, wild-type and α-syn−/− transverse muscle sections showed few cells exhibiting central nuclei (a sign of muscle regeneration) (14), no fragmented sarcoplasm and uniform fiber size. However, in dko the percentage of muscle fibers with centralized nuclei increased significantly (37.3 ± 14%, n = 6 mice) compared to either wild-type mice (0.7 ± 0.5%, n = 6 mice, P < 0.0001) or α-syn single mutant (Fig. 5E), but was not significantly different from single α-dbn−/− mice (38.5 ± 9%, n = 7 mice, P = 0.95) (Fig. 5D and E). We further analyzed changes in muscle fiber size distribution (an indicator of muscle regeneration), another hallmark of muscular dystrophy (29). The quantification of the fiber size distribution in cross-sectional areas of tibialis anterior muscles (areas below 10.000 A.U) of young adult mice (~3 months old) revealed that there was a significant shift towards smaller sizes in dko and α-dbn−/− compared to wild-type and α-syn−/−. The percentage of small fibers in dko and age-matched α-dbn−/− mice was 31.45%, and 28.5% respectively; in α-syn−/− mice it was 5%, and in wild-type mice it was 4.2%. Therefore, dko and α-dbn−/− mice had a higher percentage of small fiber sizes than wild-type and α-syn−/− mice (P = 0.0037) (~200 muscle cells/mouse strain, at least 3 mice were used for each measurement).

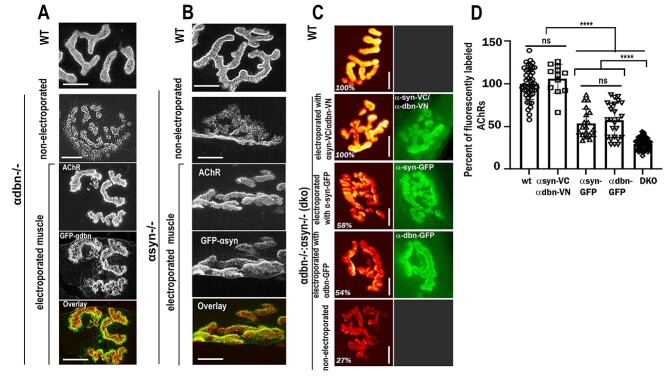

α-Syn and α-dbn exert distinct functions on the distribution of AChR in the postsynaptic membrane

Previous studies reported that α-dbn−/− and α-syn−/− NMJ phenotypes appear to be alike (7,14). Both NMJs of mice deficient in either α-dbn or α-syn display numerous small, independent AChR clusters scattered at both the crests and troughs of junctional folds and many AChR-containing streaks that extend beyond the primary synaptic cleft, in contrast, AChRs in normal muscles are evenly distributed and largely restricted to the crests of folds (Fig. 2 and (7,14)). To better understand the functional role of each of these components on the postsynaptic membrane organization of the NMJ, we electroporated the sternomastoid muscles of dko mice with individual α-dbn-GFP, and α-syn-GFP constructs and assessed the rescue of synaptic phenotype. We first validated that the GFP tag does not interfere with the function of α-dbn and α-syn. The abnormal NMJ phenotype of α-dbn−/− on electroporated muscles deficient in α-dbn was significantly restored to a normal level with α-dbn-GFP (Fig. 6A). Similarly, the introduction of α-syn-GFP in muscles deficient in α-syn restored the synaptic phenotype to a normal level (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that GFP does not interfere with α-dbn or α-syn functions.

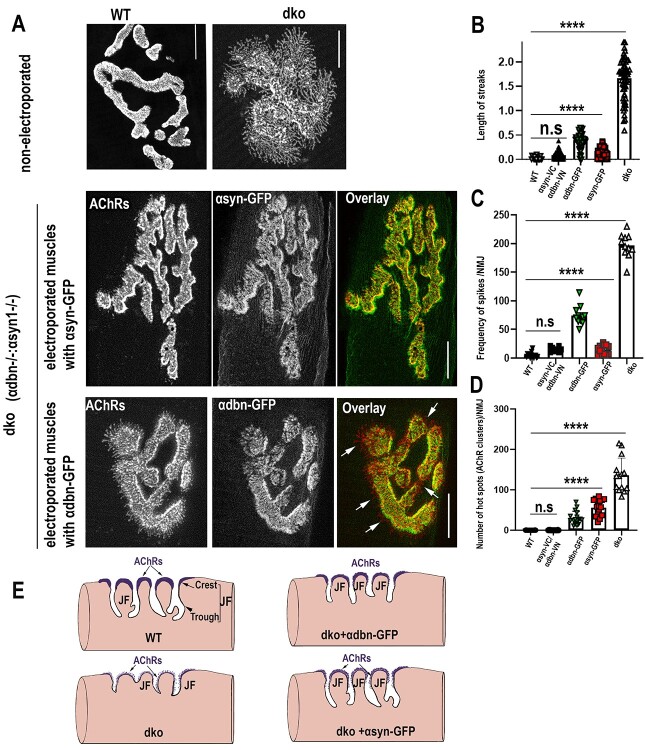

Figure 6.

α-dbn or α-syn partially rescues the density of AChRs at NMJs of dko. (A) Example of an NMJ from the sternomastoid muscle of young adult α-dbn-null mice electroporated with α-dbn-GFP. Note that the α-dbn-GFP construct restores the abnormal distribution of AChRs to normal when compared to non-electroporated synapses and wild-type. (B) Example of an NMJ from the sternomastoid muscle of young adult α-syn-null mice electroporated with α-syn-GFP. Note that the expression of α-syn-GFP restores the abnormal pattern of AChR distribution to normal when compared to wild-type synapse and non-electroporated mutant NMJs. (C) Examples of NMJs from the sternomastoid muscle of dko electroporated with either α-syn-GFP, α-dbn-GFP, or a pair of constructs containing the α-dbn N- (VN) and α-syn C- (VC) terminal fragments of Venus protein (α-syn-VC and α-dbn-VN) and labeled with a saturating dose of α-BTX-AlexaFluor 594 as described previously (30). (D) Quantification of fluorescent AChRs data from NMJs as shown in C. Data are means ± SD. Scale bars 10 μm.

Having shown that GFP fusion protein does not interfere with α-syn or α-dbn function, we next asked whether the overexpression of α-syn-GFP alone or α-dbn-GFP alone in dko sternomastoid muscle was sufficient to rescue the drastic reduction of the postsynaptic AChR density. When we electroporated the sternomastoid muscle of dko with either α-dbn-GFP or α-syn-GFP constructs and examined NMJs expressing high fluorescence intensities of GFP 10 days later, we found that NMJs of dko mice expressing either α-dbn-GFP or α-syn-GFP display a significant restoration in the density of AChRs, but considerably less than wild-type synapses. The average fluorescence intensity of labeled AChRs at NMJs expressing α-dbn-GFP was 58 ± 4% SD (n = 25 NMJs) and α-syn-GFP was 54 ± 3% SD, (n = 19 NMJs), compared to the fluorescence intensity of AChRs at non-electroporated neighboring synapses (29 ± 4% SD, n = 74 NMJs) and wild-type NMJs (100 ± 3% SD, n = 44 NMJs) (Fig. 6C and D). However, when both α-dystrobrevin–VN (fused to N-terminal fragment of Venus fluorescent protein, VN) and α-syntrophin–VC (fused to C-terminal fragments of Venus, VC) constructs were co-electroporated into the sternomastoid muscle of dko and NMJs exhibiting bimolecular fluorescence complementation signals (30) were labeled with a fluorescently-tagged α-BTX-AlexaFluor 594, the density of AChRs was completely restored to its normal level (Fig. 6C and D). We next examined whether the introduction of α-dbn-GFP or α-syn-GFP constructs into the sternomastoid muscle of dko differed in their rescue of synaptic phenotype. We found that at NMJs expressing α-dbn-GFP, the abnormal granular appearance (hot spots) of AChRs and irregularities of synaptic gutters were significantly restored compared to synapses expressing α-syn-GFP (Fig. 7A and D). Conversely, the expression of α-syn-GFP at dko NMJs substantially restored the frequency and the average lengths of abnormal extended membrane containing AChRs compared to NMJs expressing α-dbn-GFP. Quantification showed that at electroporated NMJs expressing α-dbn-GFP the frequency of streaks per synapse was 74.45 ± 16.85 SD (n = 11 NMJs, 4 mice), significantly higher than the frequency per NMJ of dko expressing α-syn-GFP (14.6 ± 7.9 SD, n = 13, 4 mice, P < 0.0001, Fig. 7C). However, at non-electroporated NMJs of dko the frequency of streaks per synapse (196.4 ± 21.19 SD, n = 20 NMJ, 4 mice) was considerably higher than wild-type and dko NMJs expressing either α-syn-GFP or α-dbn-GFP. Similarly, the average lengths of extended membrane containing AChRs beyond synaptic gutters at NMJs expressing α-dbn-GFP (0.39 ± 0.14 μm) were significantly longer than the length of streaks at dko NMJs expressing α-syn-GFP (0.1275 ± 0.09 μm, n = 20 NMJs, P < 0.0001). At non-electroporated synapses of dko, however, the average length was 1.669 ± 0.43 μm, n = 60 compared to wild-type synapses (0.024, ± 0.03 μm, n = 19). These results suggest that α-dbn likely controls the maintenance of AChR clusters at the crest of synaptic folds while α-syn likely controls the length and number of synaptic folds.

Figure 7.

α-syn and α-dbn perform distinct functions in the maintenance and distribution of AChR clusters in the postsynaptic membrane. The sternomastoid muscle of young adult male and female dko mice were electroporated with either α-dbn1-GFP or α-syn-GFP and 10 to 15 days later, the sternomastoid was bathed with α-BTX-AlexaFluor594 to label AChRs. Electroporated and non-electroporated neighboring synapses were then imaged with a confocal microscope. (A) Example of wild-type (top left panel) and non-electroporated dko (top right panel) NMJs. Images in the middle panels represent an example of electroporated NMJ expressing α-syn-GFP and labeled with α-BTX-AlexaFluor 594. Images in the bottom panels represent an example of electroporated NMJ expressing α-dbn1-GFP and labeled with α-BTX-AlexaFluor 594 (arrows showed the presence of long extensions beyond synaptic edges). (B) Graph showing the quantification of the average lengths of finger-like extensions (streaks) in electroporated and non-electroporated NMJs with either α-syn-GFP, α-dbn-GFP, or α-syn-VC and α-dbn-VN. (C) Graph showing the quantification of the frequency of abnormal streaks per synapse at electroporated muscles with either α-syn-GFP, α-dbn-GFP, or α-syn-VC and α-dbn-VN and non-electroporated NMJs. (D). Graph showing the quantification of abnormal patchy micro-clusters of AChR finger-like (hot spots) in electroporated and non-electroporated dko muscles with the above constructs). (E) A schematic representation showing the potential roles of α-dbn and α-syn in the structural organization of the postsynaptic apparatus. In the absence of both α-dbn and α-syn in the muscle, many postsynaptic regions including the synaptic folds and AChR density were highly simplified (reduced). However, when α-dbn was added AChR anchoring/localization at the crests of synaptic folds was significantly improved, while the addition of α-syn essentially restores junctional folds. Data are means ± SD. Scale bars 10 μm.

Discussion

The data presented in this work show that NMJs of double heterozygote mice (α-dbn+/−; α-syn+/−) display a normal synaptic phenotype (similar to wild-type), while NMJs of homozygote null mice (α-dbn−/−; α-syn−/−) are more severely impaired than single α-dbn−/− or α-syn−/− mice. Unlike α-syn−/− mutants, which have abnormal NMJs and show no evidence of dystrophic muscles, muscles in double mutant (α-dbn−/−; α-syn−/−) mice are dystrophic with defects in muscular strength, similar to single α-dbn−/− mice. Additionally, the absence of both α-dbn and α-syn causes no alterations in the localization or the distribution of other associated components of the DGC such as dystrophin, α- and β-dystroglycan and basal lamina components, such as laminin-γ1 in muscle fibers. Although it seems that NMJs in mice lacking α-syn display similar postsynaptic defects to those in α-dbn−/−, analyses of double knockout mice show that α-dbn and α-syn have distinct functions on the structures of the NMJ. This conclusion is supported by data showing that the introduction of α-dbn into dko muscles rescues mostly the abnormal distribution of hotspot/patchy AChR clusters (defects that are predominantly observed in single α-dbn−/− mice), while α-syn mostly rescues the long extension of membrane containing AChRs that radiate out from synaptic gutters, defects that are predominantly observed in single α-syn−/− mice (Figs 2D and7B).

The current results from rescue experiments provide two important observations about the cellular function of α-dbn and α-syn at the NMJ. The first is that the introduction of α-dbn into muscles of dko mice restores predominantly the abnormal distribution of small patchy independent clusters of AChRs within the branches of NMJs and, to a lesser extent, the abnormal structures of AChRs extending beyond the synaptic gutters (Fig. 7). These results support the view that the maintenance of high-density AChRs at the crests of synapses likely involves α-dbn. Consistent with this observation, previous studies have shown that (i) in NMJs of α-dbn−/− mice, the majority of AChRs form small, high-density clusters present at both the crests and troughs of junctional folds with short extensions of membrane containing AChRs that radiate out of undefined synaptic borders (compared to elongated extensions observed in α-syn−/−, (14), see Fig. 7) and (ii) in cultured myotubes deficient in α-dbn and upon agrin withdrawal, most AChR clusters are rapidly turned over and dispersed into small micro-aggregates (7). Although the mechanism by which α-dbn may control the tethering and the maintenance of a high density of AChR clusters in the postsynaptic membrane is not known, it was suggested that changes in the phosphorylation state of α-dbn1 may play an important role in the stability of the postsynaptic apparatus. It is also conceivable that phosphorylation of α-dbn1 at the NMJ may serve to recruit adaptor signaling proteins that regulate the stability of AChRs. Consistent with this, previous studies have shown (i) that the tyrosine-phosphorylated α-dbn1 isoform is highly concentrated at the NMJ (31), (ii) blockade of NRG/ErbB signaling pharmacologically or genetically abolished tyrosine phosphorylation of α-dbn, leading to a reduction in the stability of receptors in agrin-induced AChR clusters in cultured myotubes and in vivo (32) and (iii) the presence of several tyrosine kinases at the NMJs in the postsynaptic structure (33–37).

While there is no direct link between AChRs and α-dbn phosphorylation, it is possible that interaction of α-dbn with other intermediates may be essential for the stability and the maintenance of a high density of AChRs at synaptic sites. Recent work showed that the tyrosine-phosphorylated α-dbn1 plays an important role in maintaining high expression of the muscle-specific anchoring protein (αkap, a protein encoded within the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIα gene) in vitro system, which in turn stabilizes AChRs (38–40). Also, knockdown of αkap in cultured muscle cells significantly reduced AChR expression levels by a ubiquitin-dependent mechanism (39,41). Similarly, the knockdown of αkap causes a reduction of AChR density and alteration in the structural integrity of the postsynaptic apparatus of the NMJs, alterations that are reminiscent of those observed in α-dbn−/− mutant (41). However, αkap does not share any similarities with known deubiquitinases, suggesting that αkap, through an association with deubiquitinases, may control the stability of AChRs. Interestingly, it has been reported that α-dbn also forms a complex with the deubiquitinase Usp9x (31), and because the complex of α-dbn and αkap is indispensable for AChR accumulation, it is conceivable that α-dbn1, through its association with Usp9x, may stabilize AChRs in the postsynaptic membrane.

The second observation from this work is that the introduction of α-syn into muscles of dko mostly restores the abnormal extensions of membrane containing AChRs that radiate beyond synaptic gutters and to a lesser extent the abnormal patchy spots of AChR clusters. It is important to mention that in mice deficient in α-syn, NMJs display finger-like extensions containing AChRs that are much longer and have fewer synaptic folds than those observed in α-dbn−/− mutant synapses (Fig. 2). This supports the conclusion that α-syn is essential for the organization and stability of postsynaptic folds. Consistent with this, it was reported that α-syn serves as a scaffold/adaptor for several important signaling proteins, such as neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and utrophin (14,21), which are lost from the postsynaptic membrane of α-syn deficient synapses. On the other hand, NOS molecules have been shown to increase the expression of both talin and vinculin, which are part of the integrin complex that contributes to stabilizing the architecture of the post-synaptic membrane (42,43). Thus, it is possible that through the additive effect of signaling pathways that are dependent on NOS, α-syn may control the organization of synaptic folds at the NMJ.

While NMJs of α-syn have postsynaptic defects that appear to be similar to those in α-dbn−/−, the links between α-dbn and α-syn on the synaptic structure remain to be determined. It is well established that α-dbn and α-syn proteins are present within the same complex (8) and the direct interaction between α-dbn and α-syn is important for their retention in the intracellular membrane within the DGC (14,44). The loss of either or both α-dbn and α-syn resulted in no obvious change in the overall molecular organization of the essential DGC components ( (7) and Fig. 5A). However, in mice deficient in α-syn, the amount of α-dbn expression was reduced, particularly the phosphorylated α-dbn1 isoform (the isoform involved in the maintenance of the NMJ) (18). Likewise, the α-syn expression level was also reduced in mice deficient in α-dbn. Thus, it is important to consider the possibility that a reduction of α-dbn protein in syntrophin mutant, and a reduction of α-syn protein in α-syn mutant mice may contribute to alterations of their respective NMJs. However, in heterozygote mice (α-dbn+/−; α-syn+/−), in which α-syn and α-dbn are reduced by half, there are no apparent defects in the structural integrity of the muscle cells or the NMJ (Fig. 1). Similarly, in either syn−/−; α-dbn+/− or α-dbn−/−; α-syn+/− mice (data not shown), in which α-dbn and α-syn protein levels were much more reduced than in heterozygote or single mutants, muscle cells did not display any further abnormalities than those described in single mutants. This suggests that a threshold amount of α-dbn and α-syn likely provides a critical signal that enables the structural organization of the postsynaptic apparatus to remain unaltered and that the synaptic phenotype observed in α-syn or α-dbn single mutant is likely not due to the contribution of reduced amount (due their direct interactions) of α-dbn in α-syn mice and vice versa.

Skeletal muscles of single α-dbn and double mutant (α-syn−/−; α-dbn−/−) display no significant difference in the number of regenerating muscle fibers (identified by the central localization of nuclei and the shift in the smaller muscle sizes). However, it remains unknown whether the signaling dysfunction caused by the absence of α-syn further contributes to muscle damage induced by the absence of α-dbn in dko. In dystrophic mice, exercise (for example treadmill) appears to worsen weakness and fatigue and exacerbates muscle damage (45,46). However, the exact underlying mechanism involved in muscle damage in the exercised animal muscles remains unknown. Alterations in central nucleation observed in dko and α-dbn−/− muscles are likely caused by intrinsic muscle defects. In support of this idea, previous studies showed that selective expression of either α-dbn1 or α-dbn2 in the muscle of α-dbn−/− mice was able to completely rescue the dystrophic phenotype as no regenerating (centrally nucleated) fibers were detected in any muscles. It is also worth noting that profound postsynaptic alterations in dko had no major effect on the organization of nerve terminal (18), suggesting that alterations in central nucleation are caused by the absence of α-dbn in the muscle (Fig. 5D).

In summary, despite the striking similarities between the synaptic phenotypes of α-syn and α-dbn mutant mice, the analyses of double mutants and their rescued NMJs provide new insights into distinct roles and synergetic functions through parallel pathways of α-dbn and α-syn in the structural organization of the postsynaptic membrane of the NMJ. Moreover, analyses of double heterozygotes with different proportions of α-dbn and α-syn suggest that a threshold amount of α-dbn and α-syn likely provides a critical signal that enables the structural organization of the postsynaptic apparatus to remain unaltered.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mice deficient in α syn (47) and α-dbn (20), were bred in our animal facility. All animal usage followed methods approved by The Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee (IACUC). Heterozygotes and homozygotes were generated by crossing α-syn−/−, and α-dbn−/−. Animals were genotyped by PCR on genomic DNA isolated from the tail, with the following primers:

α-dbn forward: 5′-gggccttacctatgtgactgagtgac-3′; α-dbn reverse: 5′-tgctcgcccctacagcacccctta-3′; α-syn forward: tgccaagttctaattccatcagaagctg-3′:

α-syn reverse: 5′- acaggagcccagtcttcaatccagg-3′.

α1-AChR subunit (Chrna1; NM_007389.4): forward 5′-gaggaccaccgtgagattgt-3′ and reverse 5′-aatcgacccattgctgtttc-3′.

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh; NM_008084.2): 5′-aactttggcattgtggaagg-3′ and 5′-ggatgcagggatgatgttct-3′.

All animals were maintained in a controlled-temperature environment, under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, with ad libitum access to water and rodent chow diet mice.

Antibodies and other reagents

In this study, we used the following primary antibodies: anti-α-dystrobrevin (610 766, 1:4000, BD Biosciences), anti-α-syntrophin (PA1-25013, 1:2000, Invitrogen), anti-α-dystroglycan (clone VI41; 1:500, DSHB, Iowa), anti-β-dystroglycan (clone 7D 11; 1:500, DSHB, Iowa), anti-dystrophin (clone 7A10; 1:500, DSHB, Iowa), anti-laminin gamma-1 (clone D8, 1:250, DSHB, Iowa), anti-synaptophysin 1 (1:1000, catalog #: 101004, synaptic system) and anti-neurofilament (2H3, 1:1000; DSHB, Iowa).

The secondary antibodies were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific: goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) Alexa594 conjugated (1:400, catalog no. A32740), goat anti-mouse IgG1 Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated (1:400, catalog no. A21121). The horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG light chain specific (1:10000; Jackson ImmunoReseach laboratories, catalog no. 112-035-175), anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (1:10 000; ThermoFisher Scientific, catalog no. 31430) and anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (1:10000; ThermoFisher Scientific, catalog no. 31460). Alexa Fluor 488- and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated α-bungarotoxin (α-BTX) (1:500, catalog no. B13422 and B13423) were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific.

Western blot and RT-PCR

Hindlimb muscles were removed from mice, minced and homogenized on ice in a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate and protease inhibitors. Homogenates were centrifuged at 17 000×g for 30 min, giving a supernatant (S) and a pellet (P). The supernatant was collected and proteins were quantified using Pierce BCA protein assay. Identical amounts of proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The membranes were bathed in PBS pH 7.4, 2% skimmed milk, 0.05% Tween 20, blocking solution for 1 h, incubated with either anti-α-syn or anti-α-dbn diluted at 1:5000 in PBS plus 0.05% Tween 20 at 4°C overnight. The membranes were then incubated for 1 h in HRP-conjugated goat anti-rat or donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody at 1:20 000 (Jackson ImmunoResearch). After extensive washing, the membranes were incubated with SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Pierce).

For qRT-PCR experiments, cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription (SuperScript III, 18080-044, Invitrogen) from muscle RNA samples of all genotypes (wild-type, α-syn−/−, α-dbn−/− and double mutant). Synaptic and non-synaptic sternomastoid muscles of wild-type and double mutant were also used. The qPCR reagent was PowerTrack™ SYBR Green Master Mix (Catalog No.A46109) purchased from Applied Biosystems.The qPCR machine was a Step-OnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System by Applied Biosystems, and the software was Step-One Software, version 2.3. The qPCR primers were designed by NCBI primer blast or Primer Bank database. The internal control of gene expression was Gapdh.

Immunofluorescence, confocal microscopy and in vivo imaging

To determine the turnover rate of AChRs, animals [wild-type, heterozygote (α-dbn+/−: α-syn+/−), double homozygote (α-dbn−/−; α-syn−/−), single α-dbn−/− and α-syn−/− mice] were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of 80 mg/kg ketamine and 20 mg/kg xylazine. The sternomastoid muscle was bathed with a low dose of α-BTX-AlexaFluor594 (0.1 μg/ml for ~5 min) to label AChRs and superficial NMJs were imaged multiple times, and the fluorescence of labeled AChRs at different data points was measured over time as described previously (48,49).

To examine the postsynaptic receptor density at NMJs, the sternomastoid muscles of wild-type and knock-out mice were bathed with a saturating dose of α-BTX-AlexaFluor 549 or Alexa 488 to label all AChRs (5 μg/ml, 1 h). Synapses were imaged with the epifluorescence microscope. The fluorescence intensity of labeled receptors was quantified as described previously.

To examine synaptic folds, wild-type and mutants were perfused with 2% PFA and the sternomastoid muscles were exposed and bathed with a saturating dose of α-BTX–AlexaFluor 594 (5 μg/ml for 1 h) to label AChRs and fluorescein-conjugated Vicia villosa (VVA-B4) to label synaptic folds (14,26). The sternomastoid muscles were removed and mounted on glass slides with coverslips using Prolong Gold mounting media. NMJs were scanned with a confocal laser microscope (Leica SP8) using an HCX Plan Apochromat 100×, 1.46 numerical aperture (NA) oil immersion objective (Leica) and a resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels. The z-stacks were then collapsed and the contrast was adjusted with Adobe Photoshop CS2. The freehand toolbar of ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, version 1.49) and its measure function were used to select and measure areas of doubly labeled NMJs with fluorescently tagged α-BTX and VVA-B4.

To examine muscle innervation, the sternomastoid muscle whole mounts were fixed in 4% PFA and bathed with α-BTX-AlexaFluor 488 to label AChRs and synaptophysin1/anti-neurofilament to visualize synaptic terminal and axons. The NMJs were then imaged with a confocal microscope (Leica SP8) as described in our previous work (50).

To investigate the localization and distribution of DGC and basal lamina components, transversal cryosections (10 μm) of sternomastoid muscles were bathed with primary antibodies against DGC components, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies as described previously (23,28). The sections were then imaged by confocal microscopy. The z-stacks were then collapsed and the contrast was adjusted with Adobe Photoshop CS2.

Electroporation of constructs into the sternomastoid muscles

Young-adult single and double mutant mice (male or female 22–27 g) were anesthetized as described above. The sternomastoid muscle was surgically exposed and a solution containing constructs [10 μg of α-syn-GFP, α-dbn-GFP, α-dbn-VN (N-terminal fragment of Venus fluorescent protein, VN) and α-syn-VC (fused to C-terminal fragments of Venus, VC)] was placed over the sternomastoid muscle as described previously (30,41,51), gold electrodes were set parallel to the muscle fibers on either side of the muscle, and then eight monopolar square-wave pulses were applied perpendicularly to the long axis of the muscle. The animals were sutured and allowed to recover. 10–15 days after electroporation of constructs, the sternomastoid muscle was exposed, AChRs were labeled with α-BTX-AlexaFluor 594, and NMJs expressing GFP were imaged with either the epifluorescence or with the confocal microscope as described above. We analyzed only NMJs expressing high fluorescence intensities of GFP. Because only a few superficial muscle fibers of the sternomastoid muscles were electroporated with either α-syn-GFP or α-dbn-GFP (less than 15 muscle fibers), it is practically infeasible to examine the differences between the level of overexpression of α-dbn or α-syn in dko versus the wildtype stoichiometry of proteins in homogenates of muscles taken from electroporated and non-electroporated muscle cells.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Sternomastoid muscles were obtained from the four genotypes, dissected, transferred and properly oriented into cassettes with chilled optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) allowing the tissue to set for several minutes. The cassettes were placed in a Pyrex dish filled with ∼150 ml of isopentane, and the dish was set in a larger Styrofoam container filled with liquid nitrogen, allowing the tissues to completely freeze. Frozen tissues were mounted with OCT and placed in a cryostat chamber for immediate sectioning with a thickness of 10 μm, and then, the tissue slices were air-dried at room temperature. Cryostat cross-sections were stained with filtered 0.1% Mayers Hematoxylin (Sigma; MHS-16) for ~10 min, rinsed and incubated in 0.5% Eosin (1.5 g dissolved in 300 ml of 95% EtOH) for 10 min, then dipped in distilled water, followed by tissue dehydration with increasing concentrations of alcohol before Xylene immersion for 30 s and mounted in permount medium. The slides were examined by light microscopy and the percentage of central nucleation was determined by counting the total number of centrally nucleated fibers and total myofibers in cross-section. The Fiber areas were processed and analyzed by using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, version 1.49).

Exercise-induced fatigue, and grip strength assays

A six-lane motorized rodent treadmill (Eco 3/6 Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA) was utilized to perform the treadmill exhaustion test to assess mouse exercise capacity and endurance. A stimulus was created using the electrical shock grids. Before the exercise, the mice were properly acclimated to familiarize them with the apparatus and velocity, which was gradually increased. The animals underwent treadmill running on a horizontal treadmill, at a final speed of 12 m/min and this speed was maintained until the mice reached exhaustion. At this point, the shock grid was turned off, and the mice were allowed to rest. The criterion for exhaustion was whether the mouse spent more than 4 consecutive seconds on the shock grid rather than return to the treadmill.

To test grip strength, animals were placed on a strength meter (Columbus Instruments) and the grip strength measurements for forelimbs were taken for 5–7 mice per group and averaged. Force measurements (g) were normalized to body weight (g).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism (version 8.4.2). Data were analyzed by parametric tests (ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test, or Student’s t-test), as appropriate; a P-value < 0.05 was considered as the threshold for significant differences. Data were graphically depicted as bars showing the mean ± SD (as well as superimposed dot plots to show the dispersion of the data).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Richard Hume (University of Michigan) for critical comments on this manuscript and Akaaboune laboratory members for technical assistance and comments on this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest statement. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Isabel Martinez-Pena y Valenzuela, Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Po-Ju Chen, Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Joseph Barden, Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Olivia Kosloski, Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Mohammed Akaaboune, Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; Program in Neuroscience, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Funding

National Institutes of Health NINDS (Grants NS-047332 and NS-103845 to M.A.).

References

- 1. Ervasti, J.M. (2007) Dystrophin, its interactions with other proteins, and implications for muscular dystrophy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1772, 108–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ervasti, J.M. and Campbell, K.P. (1993) A role for the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex as a transmembrane linker between laminin and actin. J. Cell Biol., 122, 809–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Belhasan, D.C. and Akaaboune, M. (2020) The role of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex on the neuromuscular system. Neurosci. Lett., 722, 134833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sunada, Y. and Campbell, K.P. (1995) Dystrophin-glycoprotein complex: molecular organization and critical roles in skeletal muscle. Curr. Opin. Neurol., 8, 379–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Durbeej, M. and Campbell, K.P. (2002) Muscular dystrophies involving the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex: an overview of current mouse models. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 12, 349–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adams, M.E., Anderson, K.N. and Froehner, S.C. (2010) The alpha-syntrophin PH and PDZ domains scaffold acetylcholine receptors, utrophin, and neuronal nitric oxide synthase at the neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci., 30, 11004–11010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grady, R.M., Zhou, H., Cunningham, J.M., Henry, M.D., Campbell, K.P. and Sanes, J.R. (2000) Maturation and maintenance of the neuromuscular synapse: genetic evidence for roles of the dystrophin--glycoprotein complex. Neuron, 25, 279–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martinez-Pena y Valenzuela, I., Mouslim, C., Pires-Oliveira, M., Adams, M.E., Froehner, S.C. and Akaaboune, M. (2011) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor stability at the NMJ deficient in alpha-syntrophin in vivo. J. Neurosci., 31, 15586–15596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacobson, C., Cote, P.D., Rossi, S.G., Rotundo, R.L. and Carbonetto, S. (2001) The dystroglycan complex is necessary for stabilization of acetylcholine receptor clusters at neuromuscular junctions and formation of the synaptic basement membrane. J. Cell Biol., 152, 435–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deconinck, A.E., Potter, A.C., Tinsley, J.M., Wood, S.J., Vater, R., Young, C., Metzinger, L., Vincent, A., Slater, C.R. and Davies, K.E. (1997) Postsynaptic abnormalities at the neuromuscular junctions of utrophin-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol., 136, 883–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grady, R.M., Merlie, J.P. and Sanes, J.R. (1997) Subtle neuromuscular defects in utrophin-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol., 136, 871–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lyons, P.R. and Slater, C.R. (1991) Structure and function of the neuromuscular-junction in young-adult mdx mice. J. Neurocytol., 20, 969–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hack, A.A., Ly, C.T., Jiang, F., Clendenin, C.J., Sigrist, K.S., Wollmann, R.L. and McNally, E.M. (1998) Gamma-Sarcoglycan deficiency leads to muscle membrane defects and apoptosis independent of dystrophin. J. Cell Biol., 142, 1279–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adams, M.E., Kramarcy, N., Krall, S.P., Rossi, S.G., Rotundo, R.L., Sealock, R. and Froehner, S.C. (2000) Absence of alpha-syntrophin leads to structurally aberrant neuromuscular synapses deficient in utrophin. J. Cell Biol., 150, 1385–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blake, D.J., Nawrotzki, R., Peters, M.F., Froehner, S.C. and Davies, K.E. (1996) Isoform diversity of dystrobrevin, the murine 87-kDa postsynaptic protein. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 7802–7810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sadoulet Puccio, H.M., Khurana, T.S., Cohen, J.B. and Kunkel, L.M. (1996) Cloning and characterization of the human homologue of a dystrophin related phosphoprotein found at the torpedo electric organ post-synaptic membrane. Hum. Mol. Genet., 5, 489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peters, M.F., Sadoulet-Puccio, H.M., Grady, M.R., Kramarcy, N.R., Kunkel, L.M., Sanes, J.R., Sealock, R. and Froehner, S.C. (1998) Differential membrane localization and intermolecular associations of alpha-dystrobrevin isoforms in skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol., 142, 1269–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grady, R.M., Akaaboune, M., Cohen, A.L., Maimone, M.M., Lichtman, J.W. and Sanes, J.R. (2003) Tyrosine-phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated isoforms of alpha-dystrobrevin: roles in skeletal muscle and its neuromuscular and myotendinous junctions. J. Cell Biol., 160, 741–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kramarcy, N.R. and Sealock, R. (2000) Syntrophin isoforms at the neuromuscular junction: developmental time course and differential localization. Mol. Cell. Neurosci., 15, 262–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grady, R.M., Grange, R.W., Lau, K.S., Maimone, M.M., Nichol, M.C., Stull, J.T. and Sanes, J.R. (1999) Role for alpha-dystrobrevin in the pathogenesis of dystrophin-dependent muscular dystrophies. Nat. Cell Biol., 1, 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kameya, S., Miyagoe, Y., Nonaka, I., Ikemoto, T., Endo, M., Hanaoka, K., Nabeshima, Y. and Takeda, S. (1999) Alpha1-syntrophin gene disruption results in the absence of neuronal-type nitric-oxide synthase at the sarcolemma but does not induce muscle degeneration. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 2193–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ahn, A.H. and Kunkel, L.M. (1995) Syntrophin binds to an alternatively spliced exon of dystrophin. J. Cell Biol., 128, 363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brenman, J.E., Chao, D.S., Gee, S.H., McGee, A.W., Craven, S.E., Santillano, D.R., Wu, Z., Huang, F., Xia, H., Peters, M.F., Froehner, S.C. and Bredt, D.S. (1996) Interaction of nitric oxide synthase with the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 and alpha1-syntrophin mediated by PDZ domains. Cell, 84, 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Adams, M.E., Dwyer, T.M., Dowler, L.L., White, R.A. and Froehner, S.C. (1995) Mouse alpha 1- and beta 2-syntrophin gene structure, chromosome localization, and homology with a discs large domain. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 25859–25865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gee, S.H., Madhavan, R., Levinson, S.R., Caldwell, J.H., Sealock, R. and Froehner, S.C. (1998) Interaction of muscle and brain sodium channels with multiple members of the syntrophin family of dystrophin-associated proteins. J. Neurosci., 18, 128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scott, L.J.C., Bacou, F. and Sanes, J.R. (1988) A synapse-specific carbohydrate at the neuromuscular-junction-association with both acetylcholinesterase and a glycolipid. J. Neurosci., 8, 932–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Akaaboune, M., Grady, R.M., Turney, S., Sanes, J.R. and Lichtman, J.W. (2002) Neurotransmitter receptor dynamics studied in vivo by reversible photo-unbinding of fluorescent ligands. Neuron, 34, 865–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Samuel, M.A., Valdez, G., Tapia, J.C., Lichtman, J.W. and Sanes, J.R. (2012) Agrin and synaptic laminin are required to maintain adult neuromuscular junctions. PLoS One, 7, e46663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Briguet, A., Courdier-Fruh, I., Foster, M., Meier, T. and Magyar, J.P. (2004) Histological parameters for the quantitative assessment of muscular dystrophy in the mdx-mouse. Neuromuscul. Disord., 14, 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aittaleb, M., Valenzuela, I.M.P.Y. and Akaaboune, M. (2017) Spatial distribution and molecular dynamics of dystrophin glycoprotein components at the neuromuscular junction in vivo. J. Cell Sci., 130, 1752–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Balasubramanian, S., Fung, E.T. and Huganir, R.L. (1998) Characterization of the tyrosine phosphorylation and distribution of dystrobrevin isoforms. FEBS Lett., 432, 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schmidt, N., Akaaboune, M., Gajendran, N., Martinez-Pena y Valenzuela, I., Wakefield, S., Thurnheer, R. and Brenner, H.R. (2011) Neuregulin/ErbB regulate neuromuscular junction development by phosphorylation of alpha-dystrobrevin. J. Cell Biol., 195, 1171–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. DeChiara, T.M., Bowen, D.C., Valenzuela, D.M., Simmons, M.V., Poueymirou, W.T., Thomas, S., Kinetz, E., Compton, D.L., Rojas, E., Park, J.S.et al. (1996) The receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK is required for neuromuscular junction formation in vivo. Cell, 85, 501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Buonanno, A. and Fischbach, G.D. (2001) Neuregulin and ErbB receptor signaling pathways in the nervous system. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol., 11, 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brenner, H.R. and Rudin, W. (1989) On the effect of muscle activity on the end-plate membrane in denervated mouse muscle. J. Physiol., 410, 501–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wu, H., Xiong, W.C. and Mei, L. (2010) To build a synapse: signaling pathways in neuromuscular junction assembly. Development, 137, 1017–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith, C.L., Mittaud, P., Prescott, E.D., Fuhrer, C. and Burden, S.J. (2001) Src, Fyn, and yes are not required for neuromuscular synapse formation but are necessary for stabilization of agrin-induced clusters of acetylcholine receptors. J. Neurosci., 21, 3151–3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen, P.J., Zelada, D., Belhasan, D.C. and Akaaboune, M. (2020) Phosphorylation of alpha-dystrobrevin is essential for alphakap accumulation and acetylcholine receptor stability. J. Biol. Chem., 295, 10677–10688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mouslim, C., Aittaleb, M., Hume, R.I. and Akaaboune, M. (2012) A role for the calmodulin kinase II-related anchoring protein (alpha kap) in maintaining the stability of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Neurosci., 32, 5177–5185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Valenzuela, I.M.P.Y. and Akaaboune, M. (2021) The metabolic stability of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at the neuromuscular junction. Cells, 10, 358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martinez-Pena, Y.V.I., Aittaleb, M., Chen, P.J. and Akaaboune, M. (2015) The knockdown of alphakap alters the postsynaptic apparatus of neuromuscular junctions in living mice. J. Neurosci., 35, 5118–5127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tidball, J.G., Spencer, M.J., Wehling, M. and Lavergne, E. (1999) Nitric-oxide synthase is a mechanical signal transducer that modulates talin and vinculin expression. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 33155–33160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tidball, J.G. and Wehling-Henricks, M. (2004) Expression of a NOS transgene in dystrophin-deficient muscle reduces muscle membrane damage without increasing the expression of membrane-associated cytoskeletal proteins. Mol. Genet. Metab., 82, 312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hosaka, Y., Yokota, T., Miyagoe-Suzuki, Y., Yuasa, K., Imamura, M., Matsuda, R., Ikemoto, T., Kameya, S. and Takeda, S. (2002) Alpha 1-syntrophin-deficient skeletal muscle exhibits hypertrophy and aberrant formation of neuromuscular junctions during regeneration. J. Cell Biol., 158, 1097–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brussee, V., Tardif, F. and Tremblay, J.P. (1997) Muscle fibers of mdx mice are more vulnerable to exercise than those of normal mice. Neuromuscul. Disord., 7, 487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Capogrosso, R.F., Mantuano, P., Cozzoli, A., Sanarica, F., Massari, A.M., Conte, E., Fonzino, A., Giustino, A., Rolland, J.F., Quaranta, A.et al. (2017) Contractile efficiency of dystrophic mdx mouse muscle: in vivo and ex vivo assessment of adaptation to exercise of functional end points. J. Appl. Physiol., 122, 828–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Adams, M.E., Kramarcy, N., Fukuda, T., Engel, A.G., Sealock, R. and Froehner, S.C. (2004) Structural abnormalities at neuromuscular synapses lacking multiple syntrophin isoforms. J. Neurosci., 24, 10302–10309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Akaaboune, M., Culican, S.M., Turney, S.G. and Lichtman, J.W. (1999) Rapid and reversible effects of activity on acetylcholine receptor density at the neuromuscular junction in vivo. Science, 286, 503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bruneau, E., Sutter, D., Hume, R.I. and Akaaboune, M. (2005) Identification of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor recycling and its role in maintaining receptor density at the neuromuscular junction in vivo. J. Neurosci., 25, 9949–9959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Martinez-Pena, Y.V.I. and Akaaboune, M. (2020) The disassembly of the neuromuscular synapse in high-fat diet-induced obese male mice. Mol. Metab., 36, 100979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bruneau, E.G. and Akaaboune, M. (2010) Dynamics of the rapsyn scaffolding protein at the neuromuscular junction of live mice. J. Neurosci., 30, 614–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]